Abstract

Corneal diseases are a leading cause of blindness worldwide, although their early detection remains challenging due to subtle clinical presentations. Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) have shown promising diagnostic performance for anterior segment disorders. This narrative review summarizes current applications of AI in the detection of corneal conditions—including keratoconus (KC), dry eye disease (DED), infectious keratitis (IK), pterygium, Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy (FECD), and corneal transplantation. Many AI models report high accuracy on test datasets, comparable to, and in some studies exceeding, that of junior ophthalmologists. In addition to detection, AI systems can automate image labeling and support education and patient home monitoring. These findings highlight the potential of AI to improve early management and standardized classification of corneal diseases, supporting clinical practice and patient self-care.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, artificial intelligence (AI) has been increasingly integrated into ophthalmology, enabling advancements in disease detection, progression prediction, and clinical decision support. AI encompasses various computational methods, including machine learning (ML), deep learning (DL), artificial neural networks (ANNs), and deep neural networks (DNNs). These techniques facilitate the processing and analysis of large datasets with high accuracy, establishing AI as an adjunctive tool for diagnostic and prognostic evaluation.

Corneal diseases, including keratoconus (KC), dry eye disease (DED), infectious keratitis (IK), pterygium, and Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy, can lead to significant visual impairment and reduced quality of life. Traditionally, diagnosis has relied on clinical signs, slit-lamp examination, functional tests, and ophthalmologists’ interpretation of corneal topography and tomography scans. These diagnostic approaches are limited by variability in corneal map accuracy, dependence on subjective clinical assessment, and the lack of universally accepted diagnostic criteria. Recent advances in AI provide solutions to longstanding diagnostic challenges in corneal disease. When trained on large datasets of corneal images and corresponding clinical data, AI models can identify subtle pathological features that may be overlooked by clinicians. Evidence from studies supports this; for instance, the CorneAI system has been shown to increase ophthalmologists’ diagnostic accuracy from 79.2% to 88.8% [1]. While AI has not yet reliably outdone top clinicians across the board, it works well as a supportive element, boosting both accuracy and efficiency in the process.

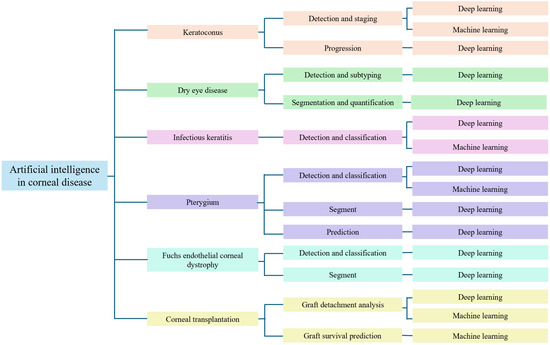

This narrative review synthesizes recent findings regarding the application of AI in the diagnosis of corneal diseases. The diagnostic performance of various AI models is compared with that of ophthalmologists, emphasizing their potential to improve clinical decision-making in corneal and external eye disease management, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Taxonomy for artificial intelligence in corneal disease.

2. Method

A literature review was conducted in PubMed, Google Scholar, Embase, and Scopus from January 1994 to September 2025. The search strategy integrated Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms with free-text terms related to artificial intelligence and corneal diseases. These included terms such as “machine learning,” “deep learning,” and “convolutional neural networks,” as well as representative disease names (e.g., “keratoconus,” “infectious keratitis,” “dry eye disease,” and “pterygium”) and relevant imaging modalities covered in this review. Only English-language articles were included. We included original research and review articles. Two reviewers independently checked titles and abstracts for relevance and then reviewed the full texts. The same reviewers assessed the full texts to decide eligibility. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion, reaching agreement on the final list of included studies. Reference lists of included studies were also manually screened. Case reports, conference abstracts, and studies not involving AI applications or lacking performance metrics were excluded.

3. Background of Artificial Intelligence Tools

In general diagnosis, ophthalmologists often utilize several AI tools, including ML, DL, ANNs, DNNs, and convolutional neural networks (CNNs). These tools are trained on large datasets of images, including corneal topography maps, anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT), slit-lamp images, and more [2]. The steps in developing an AI model are divided into three sections. First, the datasets are separated into three parts, namely training sets, validation sets, and testing sets [3]. Then, we can use training sets to train the AI models and validation sets to check them. Lastly, we can obtain the results from the testing set, which applies to the AI models. AI models can analyze pictures and provide diagnosis results, risk predictions, and support alerts in decision-making.

There are several advantages of AI tools, including high accuracy and precision, reduced measurement error through observation, and increased speed of task completion. However, there are also some disadvantages. For instance, the accuracy of some special cases will become lower because AI models cannot distinguish rare images. Additionally, patient data collected by AI models can easily compromise patient privacy. Therefore, careful data management and consideration of ethical implications are crucial.

4. Keratoconus

Characterized by progressive corneal thinning and ectasia, KC induces significant myopia and irregular astigmatism, leading to substantial visual morbidity [4,5]. While current diagnostic protocols integrate Placido topography, AS-OCT, and corneal tomography [6], the identification of early-stage disease, such as subclinical or forme fruste keratoconus (FFKC), remains elusive. Conventional parameters often lack the sensitivity to detect the earliest morphological signs of disease onset.

Early AI approaches included expert systems and statistical models. An initial expert-system study using eight parameters reported over 80% accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity [7]. Expert classifiers initially proved more effective than traditional keratometry or the Rabinowitz–McDonnell test, achieving up to 99% specificity [8]. This led to the adoption of standard ML algorithms (e.g., support vector machine (SVM), linear discriminant analysis (LDA), and random forests (RFs)) for distinguishing subclinical KC from normal eyes [9]. However, these models required manual feature engineering, a labor-intensive process that limited their ability to fully exploit raw corneal data before the advent of deep learning. The performance of these models depended heavily on the operator’s selection of parameters, potentially oversimplifying the complex, non-linear topographical patterns of early-stage disease.

SVM and decision trees (DTs) were employed for the detection of KC, FFKC, and normal eyes. Although the sensitivity and specificity of both AI models were acceptable, comparative analyses revealed that the results for SVM were slightly lower than those for DT, particularly in sensitivity for FFKC and normal eyes [10,11]. LDA and RF were also developed to predict different stages of KC. The accuracy of both models exceeded 93%, although the sensitivity of RF was slightly higher than that of LDA [12]. Overall, these studies suggest that traditional ML approaches laid an important foundation for advanced AI models in KC detection. Collectively, traditional ML approaches demonstrated that non-linear classifiers (like RF) generally outperform LDA in handling complex corneal metrics, yet they still struggle to generalize across different imaging devices without retraining.

After advancements in AI techniques, neural networks (NNs) were introduced and demonstrated significant improvements. The accuracy of NNs applied to seven categories was 80%, while a two-category model achieved 100% accuracy. However, the differences in sensitivity between the two experiments were substantial [13,14]. These studies indicate that early neural networks faced greater challenges when classifying a wider range of categories (multi-class classification) compared to binary screening tasks. Later studies selected different parameters to classify maps into normal, KC, and non-KC conditions, achieving an accuracy of 96.4%, sensitivity of 94.1%, and specificity of 97.6% in the best scenario [15].

With the rapid advancement of AI, deep learning models, particularly CNNs, have been widely employed for detection. AI tools like KeratoDetect and other CNN models can analyze images such as color-coded maps and AS-OCT. Results from various studies show that CNN models perform well in detecting different stages of KC, with performance often comparable to ophthalmologists’ decisions [4,16,17,18]. However, a critical limitation of many deep learning studies is their reliance on single-center, private datasets with limited ethnic diversity. This raises concerns regarding the models’ generalizability, as corneal thickness and curvature norms vary across populations. Furthermore, the “black-box” nature of end-to-end CNNs hinders clinical trust, as these models often lack explainable features to justify the diagnosis.

More recently, multi-source (multimodal) and hybrid AI models have emerged as a key direction for KC detection to address the limitations of unimodal imaging [19]. Multimodal fusion of Placido/tomographic data with AS-OCT-derived epithelial and stromal metrics improves early and suspect KC detection; for example, a large Translational Vision Science and Technology (TVST) study employing a feedforward ANN reported a precision of ≈98–99% for established KC and markedly better performance for suspect KC than topography alone [20]. Integrating biomechanics has further refined diagnostic precision. DL based on biomechanics uses Scheimpflug dynamic corneal deformation video sequences converted into 3-D pseudo-images; a DenseNet-based model achieved an external test Area Under the Curve (AUC) of ≈0.93 with a specificity of ≈98% [21]. The recent literature also highlights the potential of large language models and advanced screening algorithms to synthesize these complex datasets [22]. Beyond diagnosis, prognostic models are being used to gauge the likelihood of disease progression and preoperative ectasia risks. A TVST study employing a fusion network forecasted progression at the initial visit with accuracy ≈0.83, with age and posterior elevation as key contributors [23]. In a Moorfields AJO cohort, age at presentation, Kmax, and minimal corneal thickness were the principal determinants of progression risk, whereas candidate genetic variants added little incremental value [24]. Regarding ectasia screening, the refined tomographic–biomechanical index (TBIv2)—a random forest algorithm integrating Scheimpflug tomography with Corvis ST biomechanics—has demonstrated exceptional precision. It reportedly achieved an Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC) near 0.999 for clinical ectasia and significantly enhanced the detection of highly asymmetric cases in eyes presenting with normal topography (AUROC ≈ 0.94) [25].

However, the transition from algorithmic success to routine Clinical Decision Support Systems (CDSSs) faces substantial hurdles. A primary limitation is the exclusive reliance of most current models on imaging parameters; they frequently overlook non-imaging risk factors—such as eye rubbing, atopy, and systemic history—that are clinically pivotal for differentiating active progressors from stable cases. Hybrid models integrating CNN extraction with SVM or ANN classifiers offer slight advantages but lack broad validation on diverse cohorts [26]. Consequently, establishing robust clinical utility requires a multifaceted approach: enhancing model explainability (explainable artificial intelligence, XAI) to transparency validate decision drivers, integrating imaging data with demographic and symptomatic profiles from Electronic Health Records (EHRs), and ensuring generalizability through extensive testing across varied hardware and ethnicities (Table 1).

Table 1.

AI models applied to keratoconus.

5. Dry Eye Disease

Classified as aqueous-deficient or evaporative, DED is a pervasive ocular surface condition often driven by Meibomian Gland Dysfunction (MGD). This underlying pathology destabilizes the tear film, altering its lipid structure and hastening evaporation [2]. The disease burden is highest among women and adults over 50 [27], with clinical evaluation centering on metrics like tear meniscus height (TMH), break-up time (TBUT), and corneal fluorescein staining. Diagnosis, however, is often challenging because etiologies and manifestations vary widely and patient-reported symptoms frequently do not correlate with objective signs. To improve detection and risk stratification and to mitigate the subjectivity of manual grading, clinicians increasingly use meibography, AS-OCT, slit-lamp biomicroscopy, and smartphone-based imaging [28].

Meibography serves as a pivotal tool for delineating gland atrophy and quantifying dropout rates. Given the subjectivity of manual grading, deep learning has effectively established itself as the superior methodology for ensuring reproducibility. The performance gap is substantial: CNN architectures have demonstrated segmentation accuracies of 95.6% [29] and have outperformed clinical experts in classifying severe MGD by a wide margin (80.9% vs. 25.9%) [30]. Despite these impressive metrics, clinical scalability is currently hindered by device dependence; models trained largely on proprietary data (e.g., Keratograph) often struggle to generalize across different infrared imaging platforms. Unsupervised learning has also been explored: Li et al. applied SimCLR-based representation learning to classify DED into six subtypes, yielding more consistent grading standards [31].

Slit-lamp and optical coherence tomography (OCT) images contribute complementary information. A CNN-BUT method applied to slit-lamp images achieved 95% specificity and 83% sensitivity for first break-up time estimation [32]. The Smart Eye Camera, a portable slit-lamp, showed a diagnostic accuracy of 0.789 against Asia Dry Eye Society (ADES) criteria, suggesting utility for community and home settings despite slightly lower resolution compared to desktop devices [33]. AS-OCT analysis reached 84.6% accuracy, outperforming the Schirmer test and approximating ocular surface disease index (OSDI) and TBUT performance [34]. Wide epithelial mapping by OCT also demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity for DED diagnosis [35].

AI has further been applied to TMH images and multimodal datasets. Deep learning models analyzing TMH have shown higher diagnostic accuracy than ophthalmologists [36,37]. CNN-based grading of corneal fluorescein staining reduced inter-observer variability and standardized scoring [38]. Smartphone-based TMH analysis shows acceptable accuracy for home monitoring and may facilitate patient self-management [39]. The synergistic application of meibography, slit-lamp imaging, AS-OCT, and smartphone-based platforms serves to standardize assessment protocols, thereby minimizing subjective error and refining diagnostic precision. Evidence from diverse cohorts validates this multimodal approach, where accuracies consistently surpass 80–90%, and sensitivity and specificity estimates reach near-optimal thresholds (95–100%) in controlled environments [40,41].

However, widespread clinical translation is currently stalled by a fundamental limitation: the predominance of proprietary, homogeneous training data. This lack of representativeness casts doubt on the external validity of current models, particularly regarding their ability to generalize across diverse ethnicities and distinct eyelid anatomies. Moreover, contemporary AI frameworks remain heavily predicated on static imaging parameters alone. Realizing robust CDSS capabilities will require a shift toward the multimodal fusion of heterogeneous data streams, alongside transformer-based architectures capable of encoding temporal blink dynamics and tear film stability. A critical frontier involves the assimilation of “non-visual” metadata—spanning patient history, systemic pharmacology, and subjective indices—to accurately demarcate symptomatic DED from subclinical presentations (Table 2).

Table 2.

AI models applied to dry eye disease (DED).

6. Infectious Keratitis

IK, caused by bacteria, fungi, viruses, or parasites, remains a leading cause of corneal blindness when not identified and addressed early [28]. Clinical differentiation is notoriously difficult due to overlapping phenotypic features, necessitating adjunctive diagnostic tools. AI tools, leveraging slit-lamp and in vivo confocal microscopy (IVCM) images, have notably enhanced diagnostic precision in classifying cases [42]. Traditional ML methods effectively stratified keratitis types but were limited by manual feature extraction [43]. Deep learning addressed this by automating the workflow and often outperforms ophthalmologists: CNN-based models achieved 99.3% accuracy for IK detection, 84% for bacteria keratitis (BK) vs. FK discrimination, and 77.5% for filamentous vs. yeast fungi [44,45]. Today, CNNs like DenseNet121 often surpass human experts, reporting accuracies up to 99.3% [46,47]. Unfortunately, because most validation comes from private, homogeneous datasets, the generalizability of these models to other clinics remains uncertain.

IVCM imaging is particularly valuable for FK. DL has effectively outperformed decision tree approaches, with AUCs frequently >0.90. Reported accuracies for fungal vs. other keratitis reached 87–97%, while filamentous vs. yeast differentiation achieved slightly lower but still clinically meaningful performance [48,49,50,51]. Despite these results, the high cost and steep learning curve of IVCM remain barriers to widespread clinical deployment.

Beyond IVCM, AI models can also be applied to accessible sources, such as smartphone images, to diagnose microbial keratitis (MK). The advancement of smartphone images helped overcome the difficulties of remote places through rapid diagnosis and portability. However, the imbalanced data and the continued need for slit-lamp equipment limited the feasibility of using smartphone images as a dataset [52].

Multi-class systems have emerged. The DeepIK framework achieved AUCs > 0.94 for internal validation and 0.88–0.93 in external validation across bacterial, fungal, viral, Acanthamoeba, and non-infectious keratitis [53]. Such external validation underscores the generalizability of modern models. Other CNNs, like AlexNet and Visual Geometry Group Net (VGGNet), when applied to digital single-lens reflex (DSLR) and confocal images, have delivered near-perfect accuracies in select FK datasets—though questions about overfitting linger [54,55,56].

Despite these advancements, clinical adoption faces practical barriers. A major limitation is that most algorithms operate in isolation, analyzing images while blind to the patient’s context—such as contact lens history, ocular trauma, or systemic comorbidities—which is essential for expert diagnosis. Moreover, the robustness of these systems remains unproven when tested against the variability inherent in diverse ethnic populations and heterogeneous imaging platforms. Future research must prioritize (i) integrating multimodal data (images + EHR) to support holistic decision-making and (ii) validating models on publicly available, multicenter datasets to ensure robust clinical utility [57] (Table 3).

Table 3.

AI models applied to infectious keratitis (IK).

7. Pterygium

Pterygium is a frequent growth on the ocular surface, composed of fibrovascular tissue that invades the cornea and can hinder vision if it worsens or extends centrally [58]. AI has drawn increasing attention because slit-lamp or smartphone images can aid in screening and prioritizing cases, particularly in resource-limited settings [58,59]. Methods have progressed from manually designed image features and standard classifiers to DL using CNNs. While a number of studies highlight performance comparable to that of clinicians, clinical deployment is limited by phenotypic diversity and the absence of a standardized grading scale [58,59].

Across slit-lamp and handheld/smartphone images, both classical ML and DL approaches report high diagnostic accuracy. For example, an ensemble model identified pterygia requiring surgery with 94.1% accuracy and an AUC of 0.980 [60]. Segmentation networks (PSPNet or U-Net derivatives) generate lesion masks that support corneal encroachment measurement and preoperative planning [61], and a subsequent framework demonstrated longitudinal tracking of lesion change [62]. A two-stage smartphone-oriented pipeline—Faster R-CNN (ResNet101) for detection and an SE-ResNeXt50-based U-Net for segmentation—achieved high detection accuracy with consistent performance across different smartphone brands, indicating feasibility for mobile deployment [63].

External evaluations are encouraging. Systems trained to detect any pterygium and referable (surgically significant) pterygium reported AUCs of approximately 99.1–99.7% and 98.5–99.7%, respectively, with sensitivities and specificities commonly >90%, including on handheld camera datasets—supporting potential use in community screening and referral pathways [64].

Applications extend beyond color photographs. ML analyses have identified differentially expressed genes and immune microenvironmental features that may serve as biomarkers or therapeutic targets [65]. Clinically, DL-based grading on slit-lamp photographs has been explored for recurrence prediction (with moderate sensitivity in some cohorts) [66]. In addition, classical models using clinical variables can classify postsurgical best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) change with high accuracy (e.g., support vector machine accuracy 94.44%, sensitivity 92.14%, specificity 100%) [67].

The integration of multimodal and large-language models (LLMs) marks a distinct frontier in diagnostic tooling. For instance, a smartphone-based framework using a GPT-4-class model yielded 86.96% accuracy for ocular surface disease detection, yet this performance dipped to 66.67% when tasked with pterygium grading under few-shot scenarios—a disparity that brings into sharp relief both the utility and the current friction points of LLM-driven workflows [68]. In a wider context, a systematic review aggregating data from 45,913 images across 20 studies reported impressive pooled sensitivity and specificity metrics (98.1%/99.1% for diagnosis). Nonetheless, the reliability of these findings is tempered by persistent methodological flaws: specifically, the scarcity of independent external validation, a tendency to rely on image-level rather than patient-level inference, and ambiguous decision thresholds. Resolving these structural weaknesses is non-negotiable before these systems can be safely embedded into routine clinical practice [69].

Current AI applications for pterygium have evolved to encompass smartphone-enabled screening, automated grading, segmentation, longitudinal monitoring, and outcome prediction. While performance metrics remain high across external tests, successful clinical translation hinges on establishing consensus grading definitions, conducting multicenter validation across diverse populations, and ensuring model interpretability through quantitative lesion metrics and saliency maps, alongside rigorous prospective impact assessment [58,59,63,64,69] (Table 4).

Table 4.

AI models applied to pterygium.

8. Fuchs Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy

Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy (FECD) is a common, age-related disorder of the corneal endothelium. In FECD, the endothelial cells degenerate and lead to corneal edema, glare, and visual impairment. Corneal transplantation remains the only treatment in the severe stage, so early detection is crucial [28,70]. However, the subtle changes in the endothelium decrease the accuracy of FECD diagnosis. This creates the opportunity for AI algorithms to assist ophthalmologists in detection and monitoring on images like specular microscopy (SM), widefield specular microscopy (WFSM), and AS-OCT.

SM has been widely utilized in DL-based models for corneal endothelium segmentation, corneal guttae analysis, and endothelial cell density (ECD) estimation. Various models have been developed for the test, including DenseUNets, U-Net, and Mobile-CellNet. DenseUNets with feedback non-local attention (fNLA) reduced errors in estimating ECD, the coefficient of variation (CV), and hexagonality (HEX) [71]. U-Net-based distance maps provided accurate division of ECD and cell area. These demonstrated the promise of AI approaches in detecting the corneal endothelium [72]. Mobile-CellNet achieved a mean absolute error (MAE) of 4.06% and required fewer computational resources in ECD estimation. Due to the accuracy and efficiency, Mobile-CellNet could be an emerging remote clinical assessment [73]. Collectively, these DL-based models provided precise and accurate results of corneal endothelium segmentation, supporting the development of remote FECD diagnosis.

Besides SM, there are also other images applied to DL-based segmentation, including IVCM and WFSM, for example, a fully automated system developed by IVCM for segmentation and morphometric parameter estimation, which achieved a high correlation with Topcon measurements [74]. A U-Net-based model with WFSM achieved a high Dice coefficient, which indicates consistency with manual segmentation. Moreover, it also indicated potential in assessing image quality and disease severity grading of FECD [75]. These studies highlighted the promise of AI algorithms in providing efficient and accurate assessment of FECD by reducing the limitations of ophthalmologists’ interpretation.

AI algorithms can also be employed in FECD automatic diagnosis and severity grading. For instance, DL-based models with AS-OCT images achieved high accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity in classification of early-stage and late-stage FECD and healthy corneas. The performance was combined with the clinical grading, which indicated the potential to assist experts in disease staging [76]. Similarly, a U-Net system provided precise evaluation of FECD through SM images and slit-lamp-based grading. The significant performance also increased the possibility of risk prediction and therapy monitoring [77]. More recently, enhanced compact convolutional transformer (ECCT) models with IVCM images achieved high accuracy and AUC in corneal endothelium disease (CED) detection. This highlighted the possibility of CED diagnosis in remote areas or during pandemics [78]. With the advancement of AI models, the errors of FECD detection, severity grading, and clinical decision-making can be decreased.

External validation has demonstrated the generalizability of AI algorithms for FECD detection. In the research, internal datasets achieved a higher AUC, sensitivity, and specificity than external datasets, indicating the limitation of automated FECD diagnosis. Recent studies of internal and external tests have shown trends in FECD detection. As the technique develops, the clinical application of FECD might increase [79].

Hybrid and advanced models shape the future of FECD assessment. A recent study combined multiple AI-based models and even traditional algorithms for FECD detection and segmentation. U-Net was applied with the Watershed algorithm to observe the changes in average perimeter length (APL), which reflected the severity of FECD. Moreover, many studies have combined a variety of datasets, such as slit-lamp images, SM, IVCM, WFSM, and AS-OCT, to grade the stage of FECD more accurately [77,80].

In the future, these trends may improve the accuracy of FECD early detection. Many experts have started to detect FECD via subclinical corneal edema, trying to apply AI models to clinical decision-making, treatments, and challenging cases [70,81] (Table 5).

Table 5.

AI models applied to Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy (FECD).

9. Corneal Transplantation

AI algorithms have been integrated into corneal transplantation across preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative phases [82]. The application includes predicting graft outcomes and guiding surgical decision-making through OCT and topography. AI-based models can improve the accuracy of different surgeries, such as penetrating keratoplasty (PK), deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty (DALK), Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK), and Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) [83].

During the preoperative phase, AI-based models have been applied to predict outcomes and guide surgical decision-making. For example, AS-OCT images were used in DL-based models to detect the risk of graft detachment and make the plans of surgeries. These models demonstrated high sensitivity in identifying detachment cases, thought the specificity still needed a lot of improvement. However, the AI approaches could analyze subtle differences between multiple images and provided the opportunity to perform precision surgery in corneal transplantation [84].

On the other hand, the application of AI approaches in postoperative phases has been more diverse. They could be employed to detect graft detachment, analyze risk factors, and predict the survival in long periods. ML models such as least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO), classification tree analysis (CTA), and random forest classification (RFC) achieved good performance in the AUROC of graft detachment prediction. A deep learning model was developed to localize and quantify graft detachment after DMEK, achieving high accuracy and producing quantitative detachment maps to assist clinical experts. For the long-term outcome, random survival forests and Cox regression were applied to predict 10-year graft survival for DSAEK and PK. The performance was much higher than traditional regression models. Overall, AI models not only improved the precision of surgeries, but also supported the management of treatment [85,86,87].

In summary, artificial intelligence demonstrates potential across in different phases of corneal transplantation. The systematic reviews also highlight that AI technologies can assist in candidate screening, surgical planning, and surgery monitoring. The diagnostic accuracy in preoperative and postoperative phases outperforms that of clinical experts. However, there are several challenges, including the absence of standard datasets, external validation sets, and studies of the aspects. In the future, experts can focus on multicenter datasets and hybrid AI-based models to improve the accuracy of AI models in corneal transplantation [88,89,90,91] (Table 6).

Table 6.

AI models applied to corneal transplantation.

10. Discussion

Artificial intelligence shows great promise for addressing corneal conditions such as KC, DED, IK, pterygium, FECD, and corneal transplantation. Using various imaging approaches—including corneal tomography, meibography, AS-OCT, slit-lamp photos, IVCM, and even simple smartphone setups—AI systems regularly hit high marks in accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity, often matching or exceeding the efficiency and classification speed of human ophthalmologists [92,93]. In addition, these tools assist with classifying disease types, gauging severity, forecasting outcomes, and monitoring progression automatically, which aids physicians in making decisions and allows patients to take more control over their own treatment. Ultimately, this technology can support the entire patient care journey—from initial screening to long-term management—helping to expand access, especially in underserved regions.

Most reviews focused on the ability to diagnose, segment, grade, and predict by analyzing diagnostic metrics and models’ generalization. However, there are some limitations in previous reviews. For instance, Ji et al. (2022) primarily focused on diagnostic feasibility in KC, DED, IK, and pterygium and challenges in datasets [3]. Pagano et al. (2023) mainly provided an overview, with less emphasis on AI models [2]. Comprehensive studies like Nguyen et al. (2024) synthesized diagnostic performance metrics across various corneal conditions, while Nusair et al. (2025) advanced the field by advocating for reporting standardization (e.g., STARD-AI and QUADAS-AI checklists), and they also included the performance of LLMs [22,28]. In contrast to these works, our research addresses the functional gaps in CDSSs, especially in prescriptive prediction, and techniques like Federated Learning (FL) to solve ethical and privacy challenges. Moreover, we also provide a comparative analysis of different AI models across multiple diseases to guide future clinical integration.

Based on our review, distinct algorithmic architectures are suitable candidates for specific corneal diseases. Hybrid or multimodal fusion models with biomechanical data demonstrate increased performance over single-source CNNs in KC, especially in detecting subclinical cases. SimCLR has proven uniquely capable of identifying distinct clinical subtypes from meibography images in the management of DED. In IK, DenseNet121 exhibits superior performance in multiple studies in distinguishing between BK and FK. For pterygium screening, two-stage fusion models (like U-Net for segmentation) have proven robust even with smartphone-based imaging. In endothelial pathologies, segmentation accuracy for FECD is maximized by DenseUNets with feedback non-local attention, while computationally efficient models like Mobile-CellNet show promise for remote screening. Furthermore, for corneal transplantation prognosis, machine learning approaches such as random survival forests (RSFs) perform significantly better than traditional regression models in predicting long-term graft survival. This synthesis indicates that a single universal model might not be the best choice. The selection of AI models must be tailored to the specific imaging modality and clinical tasks.

Despite the impressive diagnostic metrics achieved in controlled settings, there are several challenges regarding data quality and availability. First, most studies have limited internal and external datasets, which may reduce model generalization across different populations and image conditions. In recent studies, more experts are integrating multiethnic data into training sets to deal with heterogeneity and reduce bias, thereby improving the performance of models in real-world settings [94,95,96,97,98]. Second, the heterogeneity of EHRs and data across institutions will influence the result of AI models. The implementation of standardized reporting guidelines, such as CONSORT-AI, could fix this problem. Additionally, AI models often struggle to train on limited datasets of rare corneal disease. Techniques such as data augmentation, generative modeling, and transfer learning can address these challenges [99,100].

Beyond data issues, the path to clinical translation is also limited by imaging standardization and validation. To address these problems, it is essential to establish standardized imaging protocols, preprocessing pipelines, and quality control. Crucially, the vast majority of current research lacks prospective validation. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are important to validate the AI models’ performance. RCTs can provide important evidence of AI performance in real-world clinical settings, assessing the impact on patient outcomes and decision-making processes. Nonetheless, the usage of RCTs is limited in ophthalmology because there are many challenges, such as high cost, prolonged duration of execution, lack of generalizability, and insufficient sample sizes, which limit the feasibility of RCTs on rare corneal disease. This indicates the need for alternative, rigorous prospective methodologies. Most studies rely on single-center datasets, highlighting the need for more prospective and multicenter trials [101,102,103].

There are also some gaps in CDSSs. The most critical deficiency is prescriptive prediction. While recent models can only analyze data and grade the disease, they mostly fail to propose specific interventions and therapeutic responses. For example, current models may accurately detect IK but fail to predict the response to specific antimicrobial agents or recommend the optimal timing for therapeutic keratoplasty. Additionally, existing models struggle to integrate genetics, lifestyle factors, and environmental factors to predict the long-term prognosis and risk stratification. Finally, dynamic medication alerting is also an unresolved issue. Current systems lack the capability to analyze ocular findings with systemic health profiles or medication history derived from EHRs [104].

While AI can help clinical decision-making, the role of physicians still cannot be replaced. AI serves as a support tool for clinicians to detect disease more accurately. However, specialists are expected to interpret AI results carefully to ensure the appropriate clinical decision and treatment. Currently, AI models are predominantly image-based, differing from the comprehensive diagnostic process of corneal diseases. In corneal management, clinical history, symptom severity, fluorescein staining patterns, anterior chamber reaction, pain level, and disease progression are crucial influences on decision-making. These limit AI’s ability to incorporate treatment urgency, progression, or specific management recommendations. Although the early detection and grading of disease is improved, the final interpretation and decision-making still rely on ophthalmologists’ judgment.

Beyond those functional limitations, the hurdles for clinical adoption also include trust and accountability. The black-box problem and critical ethical concerns increase the difficulties of AI application. The majority of deep learning models lack explanation of their complex decision-making process, which causes the “black-box” problem [105]. The lack of transparency is a challenge for experts to understand the behavior, identify potential biases, and check the errors of AI models. Recently, XAI and model visualization have been developed to address the issue. XAI can provide visual evidence and transparency regarding the explanation in clinical practice, allowing clinicians to analyze the results and verify the model’s clinical plausibility [106,107]. Moreover, data privacy and security are also important ethical issues. While training AI models, large numbers of images or data are the main resources. Those data should comply with strict regulations such as Health Insurance Portability and Accountability (HIPAA) or General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). These regulations regulate the collection, storage, and sharing of the datasets. However, multicenter data is important for the internal and external tests, which enhance models’ generalization. Therefore, the protection of shared private data, such as through FL, differential privacy, hybrid privacy-preserving techniques, and cryptographic techniques, is very important [108,109].

In the future, multicenter and prospective clinical trials will apply AI technologies to detect and manage corneal diseases [98,110,111]. To bridge the current functional gaps in CDSSs, future research must prioritize the development of multimodal fusion architectures. Experts could add other information such as symptoms, history, and laboratory results into the models. Regulatory frameworks are also evolving to facilitate the rules to regulate AI-based tools. For example, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first AI device for diabetic retinopathy in 2018, demonstrating that regulatory pathways for clinical AI exist. Through XAI, robust datasets, and multimodal fusion, AI tools can be changed from a diagnostic aid into a comprehensive clinical helper in corneal healthcare.

11. Conclusions

While AI models show great promise for diagnosis, their common use in clinics depends on fixing data biases and proving their performance through strict real-world testing. To close current gaps, future systems must evolve into multimodal CDSSs that combine patient history with images, along with privacy protections to ensure ethical data use. Ultimately, the goal of AI is to support the ophthalmologist, turning technical precision into a trusted, essential partner for patient care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.-C.L., C.-H.H. and T.-C.L.; methodology, C.-H.H. and T.-C.L.; validation, C.-H.H.; investigation, T.-C.L.; resources, C.-H.H. and T.-C.L.; data curation, C.-H.H. and T.-C.L.; writing—original draft preparation, C.-H.H. and T.-C.L.; writing—review and editing, I.-C.L. and C.-H.H.; visualization, T.-C.L.; supervision, I.-C.L.; project administration, I.-C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used ChatGPT 4.0 and Gemini for the purposes of grammatical checks and language editing. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| DED | Dry eye disease |

| IK | Infectious keratitis |

| MeSH | Medical Subject Headings |

| ML | Machine learning |

| DL | Deep learning |

| ANN | Artificial neural network |

| CNN | Convolutional neural network |

| DNN | Deep neural network |

| AS-OCT | Anterior segment optical coherence tomography |

| KC | Keratoconus |

| FFKC | Forme fruste keratoconus |

| SVM | Support vector machine |

| LDA | Linear discriminant analysis |

| RF | Random forest |

| DT | Decision tree |

| NNs | Neural networks |

| TVST | Translational Vision Science and Technology |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| AUROC | Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve |

| CDSSs | Clinical Decision Support Systems |

| XAI | eXplainable Artificial Intelligence |

| EHRs | Electronic Health Records |

| MGD | Meibomian gland disease |

| TMH | Tear meniscus height |

| TBUT | Tear film break-up time |

| OCT | Optical coherence tomography |

| ADES | Asia Dry Eye Society |

| OSDI | Ocular surface disease index |

| IVCM | In vivo confocal microscopy |

| FK | Fungal keratitis |

| BK | Bacterial keratitis |

| AK | Acanthamoeba keratitis |

| MK | Microbial keratitis |

| VGG | Visual Geometry Group |

| DSLR | Digital single-lens reflex |

| BCVA | Best-corrected visual acuity |

| LLM | Large language model |

| FECD | Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy |

| SM | Specular microscopy |

| WFSM | Widefield specular microscopy |

| ECD | Endothelial cell density |

| fNLA | Feedback non-local attention |

| CV | Coefficient of variation |

| HEX | Hexagonality |

| MAE | Mean absolute error |

| ECCT | Enhanced compact convolutional transformer |

| CEDs | Corneal endothelium diseases |

| APL | Average perimeter length |

| PK | Penetrating keratoplasty |

| DALK | Deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty |

| DSAEK | Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty |

| DMEK | Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty |

| LASSO | Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator |

| CTA | Classification tree analysis |

| RFC | Random forest classification |

| FL | Federated Learning |

| RSFs | Random survival forests |

| RCTs | Randomized controlled trials |

| HIPAA | Health Insurance Portability and Accountability |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| Sens | Sensitivity |

| Spec | Specificity |

| NCS-Ophs | Non-consultant specialist ophthalmologists |

References

- Maehara, H.; Ueno, Y.; Yamaguchi, T.; Kitaguchi, Y.; Miyazaki, D.; Nejima, R.; Inomata, T.; Kato, N.; Chikama, T.i.; Ominato, J.; et al. Artificial Intelligence Support Improves Diagnosis Accuracy in Anterior Segment Eye Diseases. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, L.; Posarelli, M.; Giannaccare, G.; Coco, G.; Scorcia, V.; Romano, V.; Borgia, A. Artificial Intelligence in Cornea and Ocular Surface Diseases. Saudi J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 37, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Liu, S.; Hong, X.; Lu, Y.; Wu, X.; Li, K.; Li, K.; Liu, Y. Advances in Artificial Intelligence Applications for Ocular Surface Diseases Diagnosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 1107689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Zhao, J.; Iselin, K.C.; Borroni, D.; Romano, D.; Gokul, A.; McGhee, C.N.J.; Zhao, Y.; Sedaghat, M.R.; Momeni-Moghaddam, H.; et al. Keratoconus Detection of Changes Using Deep Learning of Colour-Coded Maps. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2021, 6, e000824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabinowitz, Y.S. Keratoconus. Surv. Ophthalmol. 1998, 42, 297–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Munir, S.Z.; Sami Karim, S.A.; Munir, W.M. A Review of Imaging Modalities for Detecting Early Keratoconus. Eye 2021, 35, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, N.; Klyce, S.D.; Smolek, M.K.; Thompson, H.W. Automated keratoconus screening with corneal topography analysis. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1994, 35, 2749–2757. [Google Scholar]

- Maeda, N. Comparison of Methods for Detecting Keratoconus Using Videokeratography. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1995, 113, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbelaez, M.C.; Versaci, F.; Vestri, G.; Barboni, P.; Savini, G. Use of a Support Vector Machine for Keratoconus and Subclinical Keratoconus Detection by Topographic and Tomographic Data. Ophthalmology 2012, 119, 2231–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smadja, D.; Touboul, D.; Cohen, A.; Doveh, E.; Santhiago, M.R.; Mello, G.R.; Krueger, R.R.; Colin, J. Detection of Subclinical Keratoconus Using an Automated Decision Tree Classification. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2013, 156, 237–246.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Hidalgo, I.; Rodriguez, P.; Rozema, J.J.; Ní Dhubhghaill, S.; Zakaria, N.; Tassignon, M.J.; Koppen, C. Evaluation of a Machine-Learning Classifier for Keratoconus Detection Based on Scheimpflug Tomography. Cornea 2016, 35, 827–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herber, R.; Pillunat, L.E.; Raiskup, F. Development of a Classification System Based on Corneal Biomechanical Properties Using Artificial Intelligence Predicting Keratoconus Severity. Eye Vis. 2021, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, N.; Klyce, S.D.; Smolek, M.K. Neural Network Classification of Corneal Topography. Preliminary Demonstration. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1995, 36, 1327–1335. [Google Scholar]

- Smolek, M.K.; Klyce, S.D. Current Keratoconus Detection Methods Compared With a Neural Network Approach. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1997, 38, 2290–2299. [Google Scholar]

- Accardo, P.; Pensiero, S. Neural Network-Based System for Early Keratoconus Detection from Corneal Topography. J. Biomed. Inform. 2002, 35, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavric, A.; Valentin, P. KeratoDetect: Keratoconus Detection Algorithm Using Convolutional Neural Networks. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2019, 2019, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiya, K.; Ayatsuka, Y.; Kato, Y.; Fujimura, F.; Takahashi, M.; Shoji, N.; Mori, Y.; Miyata, K. Keratoconus Detection Using Deep Learning of Colour-Coded Maps with Anterior Segment Optical Coherence Tomography: A Diagnostic Accuracy Study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e031313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsawy, A.; Eleiwa, T.; Chase, C.; Ozcan, E.; Tolba, M.; Feuer, W.; Abdel-Mottaleb, M.; Abou Shousha, M. Multidisease Deep Learning Neural Network for the Diagnosis of Corneal Diseases. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 226, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, N.; Koppen, C.; Hafezi, F.; Ní Dhubhghaill, S.; Aslanides, I.M.; Wang, Q.; Cui, L.; Rozema, J.J. Multidisease Combinations of Scheimpflug tomography, ocular coherence tomography and air-puff tonometry improve the detection of keratoconus. Cont. Lens Anterior Eye 2023, 46, 101840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alió Del Barrio, J.L.; Eldanasoury, A.M.; Arbelaez, J.; Faini, S.; Versaci, F. Artificial Neural Network for Automated Keratoconus Detection Using a Combined Placido Disc and Anterior Segment Optical Coherence Tomography Topographer. Trans. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2024, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmotaal, H.; Hazarbassanov, R.M.; Salouti, R.; Nowroozzadeh, M.H.; Taneri, S.; Al-Timemy, A.H.; Lavric, A.; Yousefi, S. Keratoconus Detection-based on Dynamic Corneal Deformation Videos Using Deep Learning. Ophthalmol. Sci. 2024, 4, 100380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nusair, O.; Asadigandomani, H.; Farrokhpour, H.; Moosaie, F.; Bibak-Bejandi, Z.; Razavi, A.; Daneshvar, K.; Soleimani, M. Clinical Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Corneal Diseases. Vision 2025, 9, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, L.M.; Langhans, D.S.; Eggarter, V.; Freisenich, T.J.; Hillenmayer, A.; König, S.F.; Vounotrypidis, E.; Wolf, A.; Wertheimer, C.M. Keratoconus Progression Determined at the First Visit: A Deep Learning Approach with Fusion of Imaging and Numerical Clinical Data. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2024, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maile, H.P.; Li, J.P.O.; Fortune, M.D.; Royston, P.; Leucci, M.T.; Moghul, I.; Szabo, A.; Balaskas, K.; Allan, B.D.; Hardcastle, A.J.; et al. Personalized Model to Predict Keratoconus Progression From Demographic, Topographic, and Genetic Data. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 240, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrósio, R.; Machado, A.P.; Leão, E.; Lyra, J.M.G.; Salomão, M.Q.; Esporcatte, L.G.P.; Da Fonseca Filho, J.B.; Ferreira-Meneses, E.; Sena, N.B.; Haddad, J.S.; et al. Optimized Artificial Intelligence for Enhanced Ectasia Detection Using Scheimpflug-Based Corneal Tomography and Biomechanical Data. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 251, 126–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghasedi, S.; Abdel-Dayem, R. Hybrid Deep Learning and Genetic Algorithm Approach for Detecting Keratoconus Using Corneal Tomography. Int. J. Mach. Learn. 2025, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, F.E.; Farooq, A.V. Dry Eye Disease: An Upyear in 2022. JAMA 2022, 327, 478–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Ong, J.; Masalkhi, M.; Waisberg, E.; Zaman, N.; Sarker, P.; Aman, S.; Lin, H.; Luo, M.; Ambrosio, R.; et al. Artificial Intelligence in Corneal Diseases: A Narrative Review. Contact Lens Anterior Eye 2024, 47, 102284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yeh, T.N.; Chakraborty, R.; Yu, S.X.; Lin, M.C. A Deep Learning Approach for Meibomian Gland Atrophy Evaluation in Meibography Images. Trans. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2019, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.H.; Yu, S.X.; Lin, M.C. Meibography Phenotyping and Classification From Unsupervised Discriminative Feature Learning. Trans. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2021, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Yu, C.; Li, Q.; Chang, P.; Wang, D.; Li, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Tang, N.; et al. Unsupervised Learning Based on Meibography Enables Subtyping of Dry Eye Disease and Reveals Ocular Surface Features. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2023, 64, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, T.Y.; Liu, Z.Y.; Chen, D.Y. Tear Film Break-Up Time Measurement Using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks for Screening Dry Eye Disease. IEEE Sens. J. 2018, 18, 6857–6862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, E.; Ishikawa, T.; Tanji, M.; Agata, N.; Nakayama, S.; Nakahara, Y.; Yokoiwa, R.; Sato, S.; Hanyuda, A.; Ogawa, Y.; et al. Artificial Intelligence to Estimate the Tear Film Breakup Time and Diagnose Dry Eye Disease. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chase, C.; Elsawy, A.; Eleiwa, T.; Ozcan, E.; Tolba, M.; Abou Shousha, M. Comparison of Autonomous AS-OCT Deep Learning Algorithm and Clinical Dry Eye Tests in Diagnosis of Dry Eye Disease. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2021, 15, 4281–4289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edorh, N.A.; El Maftouhi, A.; Djerada, Z.; Arndt, C.; Denoyer, A. New Model to Better Diagnose Dry Eye Disease Integrating OCT Corneal Epithelial Mapping. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 106, 1488–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Rong, H.; Hei, K.; Liu, G.; He, M.; Du, B.; Wei, R.; Zhang, Y. A Deep Learning-Assisted Automatic Measurement of Tear Meniscus Height on Ocular Surface Images and Its Application in Myopia Control. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1554432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Xu, K.; Chen, X.; He, C.; Zhang, J.; Li, F.; Xiao, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, W.; et al. Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Tear Meniscus Height Measurement: A Multicenter Study. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2025, 15, 4071–4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.H.; Qin, X.R.; Li, C.D.; Peng, R.M.; Xiao, G.G.; Cheng, J.; Gu, S.F.; Wang, H.K.; Hong, J. Fully Automated Grading System for the Evaluation of Punctate Epithelial Erosions Using Deep Neural Networks. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 107, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejat, F.; Eghtedari, S.; Alimoradi, F. Next-Generation Tear Meniscus Height Detecting and Measuring Smartphone-Based Deep Learning Algorithm Leads in Dry Eye Management. Ophthalmol. Sci. 2024, 4, 100546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, P.P.; Keskar, M.; Borghare, P.T.; Methwani, D.A.; Nasre, Y.; Chaudhary, M. Artificial Intelligence in Dry Eye Disease: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e70056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, Z.; Hashemi, H.; Sotude, D.; Ebrahimi-Besheli, K.; Khabazkhoob, M.; Soleimani, M.; Djalilian, A.R.; Yousefi, S. Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Diagnosis of Dry Eye Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cornea 2024, 43, 1310–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essalat, M.; Abolhosseini, M.; Le, T.H.; Moshtaghion, S.M.; Kanavi, M.R. Interpretable Deep Learning for Diagnosis of Fungal and Acanthamoeba Keratitis Using in Vivo Confocal Microscopy Images. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, K.; Gong, L.; Li, G.; Zheng, Q.; Zhang, Q.; He, Y.; et al. Development and Multi-Center Validation of Machine Learning Model for Early Detection of Fungal Keratitis. eBioMedicine 2023, 88, 104438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, M.T.; Hsu, B.W.Y.; Lin, Y.S.; Fang, P.C.; Yu, H.J.; Chen, A.; Yu, M.S.; Tseng, V.S. Comparisons of Deep Learning Algorithms for Diagnosing Bacterial Keratitis via External Eye Photographs. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 24227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, M.; Esmaili, K.; Rahdar, A.; Aminizadeh, M.; Cheraqpour, K.; Tabatabaei, S.A.; Mirshahi, R.; Bibak-Bejandi, Z.; Mohammadi, S.F.; Koganti, R.; et al. From the Diagnosis of Infectious Keratitis to Discriminating Fungal Subtypes; a Deep Learning-Based Study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Jiang, J.; Chen, K.; Chen, Q.; Zheng, Q.; Liu, X.; Weng, H.; Wu, S.; Chen, W. Preventing Corneal Blindness Caused by Keratitis Using Artificial Intelligence. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satitpitakul, V.; Puangsricharern, A.; Yuktiratna, S.; Jaisarn, Y.; Sangsao, K.; Puangsricharern, V.; Kasetsuwan, N.; Reinprayoon, U.; Kittipibul, T. A Convolutional Neural Network Using Anterior Segment Photos for Infectious Keratitis Identification. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2025, 19, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, N.; Huang, G.; Lei, D.; Jiang, L.; Chen, Q.; He, W.; Tang, F.; Hong, Y.; Lv, J.; Qin, Y.; et al. An Artificial Intelligence Approach to Classify Pathogenic Fungal Genera of Fungal Keratitis Using Corneal Confocal Microscopy Images. Int. Ophthalmol. 2023, 43, 2203–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, S.; Zhong, J.; Zeng, H.; Zhong, P.; Li, S.; Liu, H.; Yuan, J. A Structure-Aware Convolutional Neural Network for Automatic Diagnosis of Fungal Keratitis with In Vivo Confocal Microscopy Images. J. Digit. Imaging 2023, 36, 1624–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.P.; Dai, W.; Xiao, Y.P.; Qi, M.; Zhang, L.X.; Gao, L.; Zhang, F.L.; Lai, Y.K.; Liu, C.; Lu, J.; et al. Two-Stage Deep Neural Network for Diagnosing Fungal Keratitis via in Vivo Confocal Microscopy Images. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erukulla, R.; Esmaili, K.; Rahdar, A.; Aminizade, M.; Cheraqpour, K.; Tabatabaei, S.A.; Bibak-Bejandi, Z.; Mohammadi, S.F.; Yousefi, S.; Soleimani, M. Deep Learning-Based Classification of Fungal and Acanthamoeba Keratitis Using Confocal Microscopy. Ocul. Surf. 2025, 38, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, M.; Cheung, A.Y.; Rahdar, A.; Kirakosyan, A.; Tomaras, N.; Lee, I.; De Alba, M.; Aminizade, M.; Esmaili, K.; Quiroz-Casian, N.; et al. Diagnosis of microbial keratitis using smartphone-captured images; a deep-learning model. J. Ophthalmic Inflamm. Infect. 2025, 15, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xie, H.; Wang, Z.; Li, D.; Chen, K.; Zong, X.; Qiang, W.; Wen, F.; Deng, Z.; Chen, L.; et al. Deep Learning for Multi-Type Infectious Keratitis Diagnosis: A Nationwide, Cross-Sectional, Multicenter Study. npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, M.T.; Hsu, B.W.Y.; Yin, Y.K.; Fang, P.C.; Lai, H.Y.; Chen, A.; Yu, M.S.; Tseng, V.S. A Deep Learning Approach in Diagnosing Fungal Keratitis Based on Corneal Photographs. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Cao, Y.; Li, Y.; Xiao, X.; Qiu, Q.; Yang, M.; Zhao, Y.; Cui, L. Automatic Diagnosis of Fungal Keratitis Using Data Augmentation and Image Fusion with Deep Convolutional Neural Network. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2020, 187, 105019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, A.; Prajna, N.V.; Lalitha, P.; NaPier, E.; Parker, M.; Steinkamp, P.; Keenan, J.D.; Campbell, J.P.; Song, X.; Redd, T.K. Assessing the Impact of Image Quality on Deep Learning Classification of Infectious Keratitis. Ophthalmol. Sci. 2023, 3, 100331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarayar, R.; Lestari, Y.D.; Setio, A.A.A.; Sitompul, R. Accuracy of Artificial Intelligence Model for Infectious Keratitis Classification: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1239231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tey, K.Y.; Cheong, E.Z.K.; Ang, M. Potential Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Image Analysis in Cornea Diseases: A Review. Eye Vis. 2024, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Fang, X.W.; Wu, M.N.; Zhu, S.J.; Zheng, B.; Liu, B.Q.; Wu, T.; Hong, X.Q.; Wang, J.T.; Yang, W.H. Artificial intelligence assisted pterygium diagnosis: Current status and perspectives. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 16, 1386–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, F.; Chen, W.Y.; Liu, H.; Zhong, Y.L. Application of Artificial Intelligence Models for Detecting the Pterygium That Requires Surgical Treatment Based on Anterior Segment Images. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 1084118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Fang, X.; Qian, Y.; He, K.; Wu, M.; Zheng, B.; Song, J. Pterygium Screening and Lesion Area Segmentation Based on Deep Learning. J. Healthc. Eng. 2022, 2022, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Shao, Y.; Wang, C.; Jing, J.; Yang, W. A Novel System for Measuring Pterygium’s Progress Using Deep Learning. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 819971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, C.; Wang, S.; Chen, Y.; Lin, X.; Guo, S.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Guo, Y.; et al. Accurate Detection and Grading of Pterygium through Smartphone by a Fusion Training Model. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 108, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Deshmukh, M.; Chee, M.L.; Soh, Z.D.; Teo, Z.L.; Thakur, S.; Goh, J.H.L.; Liu, Y.C.; Husain, R.; Mehta, J.S.; et al. Deep Learning Algorithms for Automatic Detection of Pterygium Using Anterior Segment Photographs from Slit-Lamp and Hand-Held Cameras. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 106, 1642–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.W.; Yang, J.; Jiang, H.W.; Yang, X.Q.; Chen, Y.N.; Ying, W.D.; Deng, Y.L.; Zhang, M.h.; Liu, H.; Zhang, H.L. Identification of Biomarkers and Immune Microenvironment Associated with Pterygium through Bioinformatics and Machine Learning. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2024, 11, 1524517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, K.H.; Lin, C.; Roan, J.; Kuo, C.F.; Hsiao, C.H.; Tan, H.Y.; Chen, H.C.; Ma, D.H.K.; Yeh, L.K.; Lee, O.K.S. Application of a Deep Learning System in Pterygium Grading and Further Prediction of Recurrence with Slit Lamp Photographs. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jais, F.N.; Che Azemin, M.Z.; Hilmi, M.R.; Mohd Tamrin, M.I.; Kamal, K.M. Postsurgery Classification of Best-Corrected Visual Acuity Changes Based on Pterygium Characteristics Using the Machine Learning Technique. Sci. World J. 2021, 2021, 6211006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, Z.; Xiu, L.; Zhang, P.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Chen, G.; Yang, W.; Chen, W. Large Language Model-Based Multimodal System for Detecting and Grading Ocular Surface Diseases from Smartphone Images. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 13, 1600202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiong, E.W.; Soon, C.Y.; Ong, Z.Z.; Liu, S.H.; Qureshi, R.; Rauz, S.; Ting, D.S. Deep Learning for Diagnosing and Grading Pterygium: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Comput. Biol. Med. 2025, 196, 110743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Kandakji, L.; Stupnicki, A.; Sumodhee, D.; Leucci, M.T.; Hau, S.; Balal, S.; Okonkwo, A.; Moghul, I.; Kanda, S.P.; et al. Current Applications of Artificial Intelligence for Fuchs Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy: A Systematic Review. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2025, 14, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vigueras-Guillén, J.P.; Van Rooij, J.; Van Dooren, B.T.H.; Lemij, H.G.; Islamaj, E.; Van Vliet, L.J.; Vermeer, K.A. DenseUNets with Feedback Non-Local Attention for the Segmentation of Specular Microscopy Images of the Corneal Endothelium with Guttae. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, J.S.; Pineda, J.; Rueda, D.; Tello, A.; Prada, A.M.; Galvis, V.; Volpe, G.; Millan, M.S.; Romero, L.A.; Marrugo, A.G. Corneal Endothelium Assessment in Specular Microscopy Images with Fuchs’ Dystrophy via Deep Regression of Signed Distance Maps. Biomed. Opt. Express 2023, 14, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, R.; Nooshabadi, S.V.; Eghrari, A.O. Mobile-CellNet: Automatic Segmentation of Corneal Endothelium Using an Efficient Hybrid Deep Learning Model. Cornea 2023, 42, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.H.; Qin, X.R.; Peng, R.M.; Xiao, G.G.; Cheng, J.; Gu, S.F.; Wang, H.K.; Hong, J. A Fully Automated Segmentation and Morphometric Parameter Estimation System for Assessing Corneal Endothelial Cell Images. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 239, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tey, K.Y.; Hsein Lee, B.J.; Ng, C.; Wong, Q.Y.; Panda, S.K.; Dash, A.; Wong, J.; Ken Cheong, E.Z.; Mehta, J.S.; Schmeterer, L.; et al. Deep Learning Analysis of Widefield Cornea Endothelial Imaging in Fuchs Dystrophy. Ophthalmol. Sci. 2026, 6, 100914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleiwa, T.; Elsawy, A.; Özcan, E.; Abou Shousha, M. Automated Diagnosis and Staging of Fuchs’ Endothelial Cell Corneal Dystrophy Using Deep Learning. Eye Vis. 2020, 7, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prada, A.M.; Quintero, F.; Mendoza, K.; Galvis, V.; Tello, A.; Romero, L.A.; Marrugo, A.G. Assessing Fuchs Corneal Endothelial Dystrophy Using Artificial Intelligence–Derived Morphometric Parameters From Specular Microscopy Images. Cornea 2024, 43, 1080–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.H.; Qin, X.R.; Xie, Z.J.; Qian, J.H.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, X.N.; Sun, Y.Z.; Peng, R.M.; Xiao, G.G.; Lin, J.; et al. Establishment of an Automatic Diagnosis System for Corneal Endothelium Diseases Using Artificial Intelligence. J. Big Data 2024, 11, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, V.H.X.; Lim, G.Y.S.; Liu, Y.C.; Ong, H.S.; Wong, E.; Chan, S.; Wong, J.; Mehta, J.S.; Ting, D.S.W.; Ang, M. Deep Learning for Detection of Fuchs Endothelial Dystrophy from Widefield Specular Microscopy Imaging: A Pilotstudy. Eye Vis. 2024, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shilpashree, P.S.; Suresh, K.V.; Sudhir, R.R.; Srinivas, S.P. Automated Image Segmentation of the Corneal Endothelium in Patients With Fuchs Dystrophy. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2021, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitoussi, L.; Zéboulon, P.; Rizk, M.; Ghazal, W.; Rouger, H.; Saad, A.; Elahi, S.; Gatinel, D. Deep Learning Versus Corneal Tomography Features to Detect Subclinical Corneal Edema in Fuchs Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy. Cornea Open 2024, 3, e0038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjmandmazidi, S.; Heidari, H.R.; Ghasemnejad, T.; Mori, Z.; Molavi, L.; Meraji, A.; Kaghazchi, S.; Mehdizadeh Aghdam, E.; Montazersaheb, S. An In-depth Overview of Artificial Intelligence (AI) Tool Utilization across Diverse Phases of Organ Transplantation. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tay, C.; Reddy, H.; Mehta, J.S. Advances in Corneal Transplantation. Eye 2025, 39, 2497–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patefield, A.; Meng, Y.; Airaldi, M.; Coco, G.; Vaccaro, S.; Parekh, M.; Semeraro, F.; Gadhvi, K.A.; Kaye, S.B.; Zheng, Y.; et al. Deep Learning Using Preoperative AS-OCT Predicts Graft Detachment in DMEK. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2023, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muijzer, M.B.; Hoven, C.M.W.; Frank, L.E.; Vink, G.; Wisse, R.P.L.; The Netherlands Corneal Transplant Network (NCTN); Bartels, M.C.; Cheng, Y.Y.; Dhooge, M.R.P.; Dickman, M.; et al. A Machine Learning Approach to Explore Predictors of Graft Detachment Following Posterior Lamellar Keratoplasty: A Nationwide Registry Study. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heslinga, F.G.; Alberti, M.; Pluim, J.P.W.; Cabrerizo, J.; Veta, M. Quantifying Graft Detachment after Descemet’s Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2020, 9, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, M.; He, F.; Lang, S.; Sabanayagam, C.; Cheng, C.Y.; Arundhati, A.; Mehta, J.S. Machine Learning to Analyze Factors Associated With Ten-Year Graft Survival of Keratoplasty for Cornea Endothelial Disease. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 831352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Fernández, H.; Alhakim-Khalak, F.; Ruiz-Alonso, S.; Díaz, A.; Tamayo, J.; Ramalingam, M.; Larra, E.; Pedraz, J.L. Comprehensive Review of the State-of-the-Art in Corneal 3D Bioprinting, Including Regulatory Aspects. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 662, 124510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuliqiman, M.; Xu, M.; Sun, Y.; Cao, J.; Chen, P.; Gao, Q.; Xu, P.; Ye, J. Artificial Intelligence in Ophthalmic Surgery: Current Applications and Expectations. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2023, 17, 3499–3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feizi, S.; Javadi, M.A.; Bayat, K.; Arzaghi, M.; Rahdar, A.; Ahmadi, M.J. Machine Learning Methods to Identify Risk Factors for Corneal Graft Rejection in Keratoconus. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 29131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiderman, Y.I.; Gerber, M.J.; Hubschman, J.P.; Yi, D. Artificial Intelligence Applications in Ophthalmic Surgery. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2024, 35, 526–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.; Li, R.; Liu, Z.; Chen, J.; Yang, Y.; Chen, H.; Lin, Z.; Lai, W.; Long, E.; Wu, X.; et al. Diagnostic Efficacy and Therapeutic Decision-making Capacity of an Artificial Intelligence Platform for Childhood Cataracts in Eye Clinics: A Multicentre Randomized Controlled Trial. eClinicalMedicine 2019, 9, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, R.M.; Channa, R.; Liu, T.Y.A.; Zehra, A.; Bromberger, L.; Patel, D.; Ananthakrishnan, A.; Brown, E.A.; Prichett, L.; Lehmann, H.P.; et al. Autonomous Artificial Intelligence Increases Screening and Follow-up for Diabetic Retinopathy in Youth: The ACCESS Randomized Control Trial. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noriega, A.; Meizner, D.; Camacho, D.; Enciso, J.; Quiroz-Mercado, H.; Morales-Canton, V.; Almaatouq, A.; Pentland, A. Screening Diabetic Retinopathy Using an Automated Retinal Image Analysis System in Independent and Assistive Use Cases in Mexico: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Form. Res. 2021, 5, e25290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathenge, W.; Whitestone, N.; Nkurikiye, J.; Patnaik, J.L.; Piyasena, P.; Uwaliraye, P.; Lanouette, G.; Kahook, M.Y.; Cherwek, D.H.; Congdon, N.; et al. Impact of Artificial Intelligence Assessment of Diabetic Retinopathy on Referral Service Uptake in a Low-Resource Setting. Ophthalmol. Sci. 2022, 2, 100168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Chen, H.; Yu, W.; Zhang, M.; Lu, F.; Ma, J.; Hao, Y.; Li, X.; Hu, B.; Shen, L.; et al. The Performance of a Deep Learning System in Assisting Junior Ophthalmologists in Diagnosing 13 Major Fundus Diseases: A Prospective Multi-Center Clinical Trial. npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Fang, J.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Xu, Z.; Zhu, S.; Yan, W.; Chu, M.; Xu, J.; Sheng, S.; et al. MCOA: A Comprehensive Multimodal Dataset for Advancing Deep Learning in Corneal Opacity Assessment. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Keenan, T.D.L.; Agron, E.; Allot, A.; Guan, E.; Duong, B.; Elsawy, A.; Hou, B.; Xue, C.; Bhandari, S.; et al. AI Workflow, External Validation, and Development in Eye Disease Diagnosis. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e2517204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumuni, A.; Mumuni, F. Data Augmentation: A Comprehensive Survey of Modern Approaches. Array 2022, 16, 100258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Sklar, B.; Tian, J.; Gabriel, R.; Engelhard, M.; McNabb, R.P.; Kuo, A.N. Improving Artificial Intelligence–Based Microbial Keratitis Screening Tools Constrained by Limited Data Using Synthetic Generation of Slit-Lamp Photos. Ophthalmol. Sci. 2025, 5, 100676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.P.O.; Liu, H.; Ting, D.S.; Jeon, S.; Chan, R.P.; Kim, J.E.; Sim, D.A.; Thomas, P.B.; Lin, H.; Chen, Y.; et al. Digital Technology, Tele-Medicine and Artificial Intelligence in Ophthalmology: A Global Perspective. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2021, 82, 100900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The CONSORT-AI and SPIRIT-AI Steering Group. Reporting Guidelines for Clinical Trials Evaluating Artificial Intelligence Interventions Are Needed. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1467–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Liu, A.; Su, B.; Wu, M.; Zhang, B.; Chen, G.; Lu, F.; Hu, L.; Mao, X. Standardized Corneal Topography-Driven AI for Orthokeratology Fitting: A Hybrid Deep/Machine Learning Approach With Enhanced Generalizability. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2025, 14, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peek, N.; Capurro, D.; Rozova, V.; Van Der Veer, S.N. Bridging the Gap: Challenges and Strategies for the Implementation of Artificial Intelligence-based Clinical Decision Support Systems in Clinical Practice. Yearb. Med. Inform. 2024, 33, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassija, V.; Chamola, V.; Mahapatra, A.; Singal, A.; Goel, D.; Huang, K.; Scardapane, S.; Spinelli, I.; Mahmud, M.; Hussain, A. Interpreting Black-Box Models: A Review on Explainable Artificial Intelligence. Cogn. Comput. 2024, 16, 45–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, B.M.; Zwezerijnen, G.J.C.; Burchell, G.L.; Van Velden, F.H.P.; Menke-van Der Houven Van Oordt, C.W.; Boellaard, R. Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) in radiology and nuclear medicine: A literature review. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1180773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudin, C. Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2019, 1, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, N.; Pandey, S.; Gupta, A.; Dudani, P.; Gupta, S.; Rangarajan, K. Data Privacy in Healthcare: In the Era of Artificial Intelligence. Indian Dermatol. Online J. 2023, 14, 788–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, W.N.; Cohen, I.G. Privacy in the age of medical big data. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linardatos, P.; Papastefanopoulos, V.; Kotsiantis, S. Explainable AI: A Review of Machine Learning Interpretability Methods. Entropy 2020, 23, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.H.; Zheng, B.; Wu, M.N.; Zhu, S.J.; Fei, F.Q.; Weng, M.; Zhang, X.; Lu, P.R. An Evaluation System of Fundus Photograph-Based Intelligent Diagnostic Technology for Diabetic Retinopathy and Applicability for Research. Diabetes Ther. 2019, 10, 1811–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).