Abstract

Background/Objectives: Hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) is a common neurological outcome of perinatal asphyxia, with cerebral palsy (CP) being the most severe lasting effect. Perinatal brain injury activates the immune system and induces the release of inflammatory mediators. Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs) play a crucial role in neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration. This study explored the potential link between MMP2 promoter polymorphisms and the development of CP in children with a history of perinatal asphyxia. Methods: We enrolled 212 patients (130 males and 82 females) with documented perinatal asphyxia, who underwent a comprehensive neurological assessment and neuroimaging, including ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). We genotyped the MMP2 promoter polymorphisms rs243866, rs243865, and rs243864 using real-time polymerase chain reaction. Haplotype frequencies were calculated using Haploview software. Results: As expected, patients with HIE are more likely to develop CP (p = 0.000). In a study of 104 patients who developed CP, the frequencies of the A (rs243866), T (rs243865), and G alleles (rs243864) were nearly twice as high compared to those without CP (p = 0.008, p = 0.019, and p = 0.008, respectively). Haplotype analysis supported these findings, showing that the ATG haplotype was significantly more common among patients who developed CP (p = 0.004). Additionally, in patients with MRI-confirmed brain damage, the ATG haplotype was more frequently observed (p = 0.019). Conclusions: The ATG haplotype of the MMP2 promoter may indicate a risk factor for developing cerebral palsy (CP) in patients who experience perinatal asphyxia and could serve as a potential diagnostic predictor of CP.

1. Introduction

Perinatal asphyxia happens when there is insufficient blood flow or gas exchange to or from fetal tissues during the critical periods just before, during, and after birth [1]. In developed countries, it affects about 2 per 1000 births, while in developing countries, the rate can be up to 10 times higher due to limited access to healthcare. About 15–20% of affected infants may not survive the neonatal period, and around 25% of survivors are likely to face severe, lasting neurological deficits. Hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) is a common neurological outcome of perinatal asphyxia, with cerebral palsy (CP) being the most serious consequence [1,2,3].

The pathogenesis of HIE and CP is complex and not fully understood. After a hypoxic–ischemic insult, brain injury occurs in two phases: the acute phase, characterized by necrotic processes due to ischemia that lead to irreversible damage, and the latent (reperfusion) phase, during which apoptotic processes extend into previously unaffected. Susceptibility to ischemia varies with gestational age, leading to distinct injury patterns. Term infants usually experience gray matter damage, leading to laminar cortical necrosis, while preterm infants mostly suffer white matter damage, causing periventricular leukomalacia [4]. These injuries are key factors in CP, the most common cause of lasting motor disability in children [5].

Historically, CP was diagnosed based on clinical observation of delayed motor development and altered muscle tone. However, advances in imaging techniques, such as cranial ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), have led the American Academy of Neurology and the Child Neurology Society to recommend confirming clinical diagnoses with imaging [6]. MRI is now considered the gold standard for assessing hypoxic–ischemic injury, and combining genetic and imaging data may enhance understanding of individual vulnerability and improve early diagnosis [7,8].

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are zinc-dependent enzymes that play a vital role in both normal brain function and hypoxic–ischemic injury [9]. In the central nervous system, MMPs are involved in synaptic signaling, maintaining the blood–brain barrier, neuroinflammation, and neuronal loss. Besides HIE, the expression of these enzymes increases in neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and multiple sclerosis, with elevated levels potentially worsening brain injury [10].

Research has focused on MMP-2 and MMP-9, which are crucial for maintaining blood–brain barrier integrity and for processes such as angiogenesis and remyelination. Elevated MMP-2 levels are associated with white matter damage, while MMP inhibition may help reduce neuronal loss and support recovery [11,12].

The MMP2 gene encodes the proenzyme MMP-2, and its expression may be affected by promoter polymorphisms such as −1575G/A, −1306C/T, and −790T/G. These MMP2 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are associated with ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, cardiovascular diseases, and certain cancers [13,14]. However, there is limited research on the MMP2 gene polymorphisms as risk factors for developing CP. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the potential association between MMP2 promoter SNPs (−1575G/A (rs243866), −1306C/T (rs243865), and −790T/G (rs243864)) and CP onset, comorbidities, and neurodiagnostics in children with a history of perinatal asphyxia.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

This retrospective prospective study was conducted from 2017 to 2024 at the Clinic of Neurology and Psychiatry for Children and Youth in Belgrade, Serbia, as well as the Institute of Human Genetics, Faculty of Medicine, University of Belgrade. During this period, a total of 212 children were diagnosed with perinatal asphyxia according to standard guidelines [1]. All participants underwent comprehensive neurological evaluations and were classified using the Sarnat and Sarnat system [15]. Neuroimaging assessments, including ultrasound and MRI, were used to confirm HIE and IVH/periventricular leukomalacia. For patients included retrospectively, data on neuromotor assessment and additional diagnostics were obtained from existing medical records, while prospectively included patients were monitored from the neonatal period at regular 3–6 month intervals for at least 2 years. The diagnosis of CP was made based on standard criteria [5]. All patients ranged in age from neonates to 16 years old.

Additionally, epidemiological data were collected, including information on gender, gestational age (GA), birth weight, and Apgar scores at five minutes (AS 5′). The main inclusion criterion was the presence of perinatal asphyxia. Exclusion criteria were other established causes of neonatal encephalopathy, such as preeclampsia, intrauterine growth restriction, congenital anomalies, maternal or fetal infection, uncontrolled diabetes or thyroid disease of the mother, severe neonatal jaundice (kernicterus), maternal or fetal toxic exposure, and maternal thrombophilia confirmed by genetic testing. Also, children with established genetic causes of cerebral palsy, such as monogenic disease or chromosomal aberrations, were excluded. Furthermore, children who developed other specific neurodevelopmental disorders, aside from cerebral palsy, were not included in the study. The research received approval from the Ethical Committee of the Clinic of Neurology and Psychiatry for Children and Youth (No. 1-109/2) and the Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Belgrade (No. 1322/IV-5).

2.2. DNA Extraction and Genotyping

The molecular genetics analysis was conducted at the Institute of Human Genetics, Faculty of Medicine, University of Belgrade. DNA was isolated from peripheral blood leukocytes using the salting-out method [15]. We genotyped three SNPs in the MMP2 promoter region: rs243866 (−1575 G/A), rs243865 (−1306 C/T), and rs243864 (−790 T/G) by real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). TaqMan® SNP genotyping assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions, utilizing the ABI 7500 real-time PCR machine from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA, USA).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses are performed using SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The statistical differences in genotype and allele frequencies among the groups were compared using the chi-square test. Continuous clinical data were analyzed using either Student’s t-test or the Kruskal–Wallis test, depending on the distribution of the variables. The association between MMP2 promoter polymorphisms and the analyzed variables (HIE, CP, ultrasound, and MRI) was explored using the odds ratio calculator (VassarStats). The correlation was analyzed using the Spearman rank correlation test. Haplotype analysis was performed using the “Confidence Intervals for LD” method in Haploview software 4.2.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics of the Study Group

Our study included 212 children, 130 males, and 82 females. The average gestational age (GA) at birth was 33.9 weeks (±4.9), with a median of 33 weeks, and a range from 24 to 42 weeks. The average birth weight was 2358.4 g (±1023.3), with a median of 2100 g, ranging from 640 g to 5740 g. The average Apgar score at the fifth minute (AS 5′) was 6.38 (±2.2), with a median score of 7 on a scale of 0 to 10.

Intraventricular hemorrhage was observed in 33 children (15.6%), while HIE was present in 102 children (48.1%). Cerebral palsy was diagnosed in 104 children (49.1%), and 108 children (50.9%) did not have CP.

Table 1 summarizes the clinical characteristics, risk factors for CP, comorbidities, and neuroimaging of CP. There were no significant differences in gender, sepsis, or neonatal convulsions prevalence between children with and without CP. Similarly, GA, birth weight, and AS 5′ showed no significant differences. However, children with CP had higher rates of IVH (p < 0.001, OR = 6.0, 95% CI = 2.36–15.27) and HIE (p < 0.001, OR = 15.6, 95% CI = 7.93–30.73) compared to those without. All children with CP exhibited developmental delays (p < 4.39 × 10−18). The prevalence of epilepsy was also significantly higher in these children (p < 0.001, OR = 14.9, 95% CI = 6.00–37.19). Pathological findings on ultrasound (p < 0.001, OR = 21.4, 95% CI = 10.38–44.04), and MRI (p < 0.001, OR = 18.1, 95% CI = 8.62–38.14) were outstanding predictors of CP development.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the participants.

3.2. Genotype and Allele Frequencies

Table 2 shows the frequencies of MMP2 promoter polymorphisms in our study group. The frequencies of all analyzed polymorphisms were in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium.

Table 2.

Frequencies of genotypes and alleles for MMP2 promoter polymorphisms in our study group.

3.3. Associations of MMP2 Genotypes with Neurological Outcomes

Table 3 shows the distribution of MMP2 promoter genotypes and allele frequencies in relation to HIE and CP diagnoses. In children with HIE, the frequencies of the −1575 G/A (GA+AA), −1306 C/T (CT+TT), and −790 T/G (TG+GG) genotypes were nearly twice as high as in children without HIE (p = 0.010, OR = 2.1, 95% CI = 1.19–3.33; p = 0.033, OR = 1.8, 95% CI = 1.05–3.24; p = 0.018, OR = 2.0, 95% CI = 1.13–3.51, respectively). However, the frequencies of the −1575 A, −1306 T, and −790 G alleles did not differ significantly between children with or without HIE.

Table 3.

Frequencies of genotypes and alleles for MMP2 polymorphisms in relation to neurological outcomes.

Children diagnosed with CP exhibited significantly higher frequencies of the −1575 G/A (GA+AA), −1306 C/T (CT+TT), and −790 T/G (TG+GG) genotypes compared to children without CP (p = 0.001, OR = 2.7, 95% CI = 1.54–4.90; p = 0.002, OR = 2.4, 95% CI = 1.36–4.21; p = 0.001, OR = 2.5, 95% CI = 1.44–4.49, respectively). Additionally, the −1575 A, −1306 T, and −790 G alleles were more common in children with CP than in those without (p = 0.008, OR = 2.0, 95% CI = 1.21–3.20; p = 0.019, OR = 1.8, 95% CI = 1.12–2.98; p = 0.008, OR = 1.9, 95% CI = 1.20–3.10). Our findings suggest that the genotypes and alleles of the MMP2 promoter SNPs are strongly linked to the development of CP.

The distribution of CP subtypes was as follows: 48.5% had spastic quadriparesis, 21.4% spastic hemiparesis, 9.7% spastic diplegia, 12.6% hypotonic, 1.9% had dyskinetic (extrapyramidal), and 5.8% had mixed CP. The frequencies of risk genotypes for the analyzed promoter polymorphisms within each CP subtype were as follows: 44.0% to 46.0% in spastic quadriparesis, 36.4% to 40.9% in spastic hemiparesis, 70.0% in spastic diplegia, 69.2% in hypotonic CP, 50.0% in dyskinetic (extrapyramidal) CP, and 66.7% in mixed CP. There were no significant differences in genotype frequencies based on the CP subtype.

MMP2 promoter polymorphisms demonstrated a similar pattern of association with neuroradiological findings as they did with neurological outcomes (Table 4). A marginal statistical significance was observed for the −790 T/G polymorphism, indicating that TG+GG genotypes were more often found in patients with detectable ultrasound pathology. Children with MRI-verified central nervous system damage had a significantly higher prevalence of the −1575 G/A (GA + AA), −1306 C/T (CT + TT), and −790 T/G (TG + GG) genotypes compared to children with normal MRI results (p = 0.002, OR = 2.6, 95% CI = 1.42–4.89; p = 0.003, OR = 2.5, 95% CI = 1.36–4.61; p = 0.001, OR = 2.7, 95% CI = 1.48–5.02, respectively). Additionally, the −1575 A, −1306 T, and −790 G alleles were more prevalent in children with confirmed CNS damage (p = 0.038, OR = 1.8, 95% CI = 1.06–2.98; p = 0.037, OR = 1.7, 95% CI = 1.03–2.81; p = 0.007, OR = 2.0, 95% CI = 1.19–3.27, respectively). Overall, the genotypes and alleles of the MMP2 promoter exhibited a strong correlation with MRI findings.

Table 4.

Frequencies of genotypes and alleles for MMP2 polymorphisms in relation to neuroradiological findings.

3.4. Haplotype Analysis

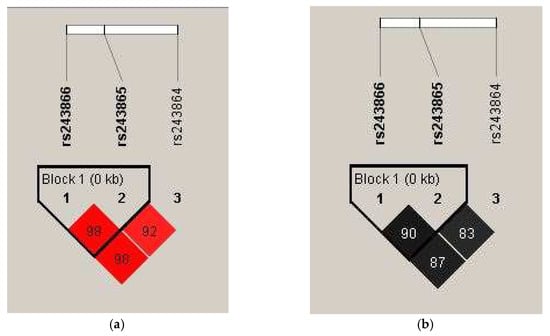

Polymorphisms −1575 G/A, −1306 C/T, and −790 T/G, within the MMP2 gene, exhibit linkage disequilibrium (LD). Therefore, haplotype analysis for these SNPs was also conducted (Table 5). Figure 1 presents the obtained D′ and r2 values demonstrating this relationship. A strong haplotype block was identified between the −1575 G/A and −1306C/T polymorphisms of the MMP2 gene using the “Confidence Intervals for LD” method [16].

Table 5.

Neurological outcomes, neuroradiological findings, and MMP2 haplotype.

Figure 1.

Values of (a) D′ and (b) r2 for the analyzed MMP2 gene polymorphisms. In panel (a), the intensity of the red color and the numbers in the fields represent the D′ values—a bright red indicates D′ = 100% with a logarithm of the odds (LOD) greater than 2. A decrease in color intensity reflects a lower D′ value. In panel (b), different shades of gray and their corresponding numbers illustrate r2 values, with darker shades indicating higher r2 values.

Haplotype analysis was performed on 212 patients. A significant difference was found in the frequencies of the ATG and GCT haplotypes of the MMP2 gene polymorphisms when comparing patients with cerebral palsy to those without. These frequencies also correlated with MRI findings (Table 4). Patients without CP were more likely to have the GCT haplotype, while those with CP were more likely to have the ATG haplotype (p = 0.022 and p = 0.004, respectively). Additionally, the GCT haplotype was more common in patients with normal MRI results, whereas the ATG haplotype was more prevalent in patients with pathological MRI findings (p = 0.013 and p = 0.019, respectively). The ATG haplotype is identified as a genetic risk factor for developing CP and shows a strong correlation with MRI-detected pathology. As expected, a significant link exists between these pathological MRI findings and the development of CP (r = 0.617, p < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.519–0.699), and haplotype analysis suggests that the ATG haplotype could serve as a diagnostic predictor of CP.

4. Discussion

Cerebral palsy is often described as an umbrella diagnosis because it covers a wide range of conditions with different causes. Genetic factors contributing to CP can be viewed from multiple angles and may vary greatly. Current research shows that significant genetic alterations, like monogenic diseases or chromosomal abnormalities, are more common causes than previously thought. Clinical features of cerebral palsy are linked to copy number variants in 4% or more individuals, while single-nucleotide variants or indels are present in at least 14% [17]. However, in most cases, the genetic aspect remains unrecognized or absent, as environmental factors—especially perinatal asphyxia—are considered enough to explain the condition. Interestingly, some children who suffer severe perinatal brain injuries such as HIE or IVH develop lasting effects like CP, while others do not. Similarly, some children with mild perinatal asphyxia still go on to develop CP later. Most likely, these cases are due to a multifactorial mechanism, where certain genetic variants, combined with hypoxic brain injury, influence the risk of lasting neuronal damage and changes in brain structure. Conversely, some genetic variants might act protectively. Recognizing these variants in patients with CP is vital for prevention and for providing optimal clinical care, including targeted treatments.

In this study, we examined clinical characteristics, neuroimaging findings, and MMP2 gene polymorphisms in relation to CP development after perinatal asphyxia.

Prematurity and low birth weight are recognized risk factors for CP. Our results showed no significant differences in gestational age or birth weight between groups with and without CP. Interestingly, children without CP had a slightly lower average gestational age than those with CP. Although prematurity has long been considered a major risk factor for brain injury, recent evidence suggests that the immature brain may be somewhat more resistant to hypoxia–ischemia than the term brain. Gunn et al. demonstrated that the preterm brain exhibits greater neuroplasticity and tolerance to oxygen deprivation [18]. Since all our patients experienced perinatal asphyxia, Apgar scores did not differ significantly between groups, though AS 5′ values were slightly higher among children without CP, indicating less severe hypoxic insult.

As expected, HIE emerged as one of the most significant contributors to CP development. HIE was notably more common in the CP group, reinforcing its well-known role as a primary cause of motor disabilities [19,20]. One study reported that in term neonates, HIE is the main mechanism that damages deep gray nuclei and corticospinal tracts, leading to a dyskinetic form of CP later in life [21]. Volpe noted that in preterm infants, immature autoregulation, systemic hypoxia, and reperfusion-related inflammation contribute to the selective vulnerability of the periventricular white matter, increasing the risk of CP [22]. Our findings support this model: children with HIE were significantly more likely to develop CP, confirming that the severity of early hypoxic–ischemic injury is critical for long-term outcomes.

Intraventricular hemorrhage was also more frequent among children with CP in our study. This finding aligns with previous research indicating that IVH, particularly when followed by periventricular leukomalacia or gliosis, strongly predicts CP development [23]. Although the number of IVH cases in our cohort was limited, the trend confirms that hemorrhagic and ischemic lesions often coexist in the pathogenesis of CP.

Developmental delay and epilepsy were notably more frequent in the CP group. Although neonatal convulsions appeared more frequently in the CP group, the difference was not statistically significant in our cohort. Neonatal convulsions often precede epilepsy diagnosis, suggesting that seizure activity reflects the severity of brain damage rather than being an isolated manifestation. Glass et al. reported that neonatal seizures and later epilepsy correlated with extensive cortical injury on MRI [24].

Cranial ultrasound and MRI revealed abnormalities in a significant proportion of children with CP, demonstrating a strong correlation between neuroimaging findings and CP development. These results agree with those of Horber et al. and Novak et al., who recognized MRI as the gold standard for detecting brain lesions and predicting outcomes [5,25]. Cranial ultrasound remains an essential first-line imaging modality in neonates due to its accessibility and ability to identify common hemorrhagic and ischemic lesions, but further evaluation with MRI is often required to fully characterize parenchymal injury, especially when subtle hypoxic–ischemic changes are suspected [26]. A limitation of our study is that not all participants underwent MRI, including some with abnormal ultrasound results, which limited the ability to confirm lesions fully.

Metalloproteases are vital for maintaining the extracellular matrix, a process that involves carefully regulated, dynamic protein synthesis and degradation. This process occurs slowly under stable conditions but escalates during inflammation, tissue injury, or heightened mechanical stress [9]. The functional effects of MMP2 promoter polymorphisms are not fully understood. Price et al. found that the C to T transition at −1306 disrupts Sp1 transcription factor binding (CCACC box), significantly lowering promoter activity. Additionally, the A allele of the −1575 SNP is expected to reduce the binding affinity of transcription factors like NF-κB and AP-2 compared to the G allele [27]. This is supported by in silico models such as SNP Function Prediction [28], HaploReg [29], and JASPAR [30], suggesting that these SNPs could affect transcription factor binding and chromatin states. While the minor allele frequencies of these SNPs may decrease promoter activity and potentially offer protective effects in cases of MMP2 overexpression, the overall impact of these changes remains complex and is still being studied.

Our results suggest that MMP2 promoter polymorphisms may affect neurological outcomes after perinatal asphyxia. Specifically, the −1575 A, −1306 T, and −790 G minor alleles were all linked to CP development. This finding aligns well with MRI pathological results, as the most reliable neuroimaging diagnostics for confirming the permanent effects of hypoxic brain injury underlying CP. Furthermore, haplotype analysis showed that the ATG haplotype, which includes these three alleles, is significantly more common in children with CP and abnormal MRI findings. In contrast, the GCT haplotype appears to have a protective effect. Our study is the first of its kind to look at the relationship between the development of CP and these genetic variations in infants who experienced hypoxic injury during the prenatal period. O’Callaghan et al. performed a case–control study with multivariable analysis of candidate SNPs selected for their association with inflammation or other previously reported risk factors for cerebral palsy in both the mother and the child. Among other analyzed SNPs, MMP2 rs243865 showed association with CP, although statistical significance was lost after correction for multiple testing. The distribution of genotype frequencies resembles our findings for this SNP, with the CC genotype being more frequent in the control group [31]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the only study exploring the promoter MMP2 SNPs in association with CP:

However, MMP expression, including MMP2, has been investigated in patients with CP at both the protein and mRNA levels. Thus, in several studies, the concentration of different MMPs in serum or amniotic fluid was measured, providing significant indirect evidence. One study demonstrated that higher concentrations of MMP-8 in amniotic fluid were significantly associated with an increased risk of CP by age 3, supporting the hypothesis that increased extracellular matrix remodeling during pregnancy may predispose to perinatal brain injury [32]. Salah et al. reported higher levels of serum MMP-9 in hypoxic–ischemic newborns, which correlated with the severity of neonatal encephalopathy [33]. Furthermore, Maqsood et al. reported significantly elevated serum MMP-9 levels and moderately elevated MMP-2 concentrations in children with CP, suggesting an active inflammatory process and blood–brain barrier dysfunction [34]. Recently, Nemska et al. demonstrated increased expression of several metalloprotease genes, particularly MMP2, in tendon tissue from individuals with different forms of CP. Interestingly, MMP-2, also known as gelatinase A or type IV collagenase, is the most abundantly expressed MMP in tendons [35]. Despite being caused by a non-progressive injury to the developing brain, CP leads to ongoing changes in the musculoskeletal system. These changes may manifest as spasticity, dyskinesia, dystonia, or hypertonia, often leading to fixed contractures—permanent shortening and stiffness of the muscle-tendon unit that reduces joint mobility [36].

Studies in adults have reported similar molecular pathways. The same MMP2 promoter polymorphisms have been associated with increased susceptibility to Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, and Parkinson’s disease, likely due to enhanced transcriptional activity and blood–brain barrier permeability [12,37]. These parallels suggest that MMP-driven neurovascular remodeling may represent a shared mechanism across age groups—from neonatal HIE to late-life neurodegeneration [38].

However, reports regarding the role of MMP-2 in hypoxic–ischemic injury are often contradictory. Some studies in both animal and human subjects suggest that, after injury, MMP-2 levels remain stable, whereas MMP-9 is more consistently elevated [39]. Other studies indicate that both MMP-2 and MMP-9 increase, but their peak levels and the duration of elevated values differ. Administration of an anti-inflammatory agent led to inhibition of MMP-9 during the acute phase of ischemic damage and activation of MMP-2 during the delayed phase of injury, during recovery [40]. Further studies are needed to clarify the exact neuroprotective and neurodegenerative mechanisms of MMP-2 because its proteolytic activity is most likely time-dependent.

Our study faces limitations due to a small sample size. To enhance the generalizability of our findings, they should be validated in an independent cohort. Furthermore, it is essential to consider other environmental and confounding factors. Perinatal asphyxia is a key environmental factor in the development of CP. While the study’s exclusion criteria reduce the impact of other known perinatal injuries, some confounding factors remain, such as varying postnatal conditions and the effects of early treatment and developmental interventions. Additionally, as the SNPs are in the gene’s regulatory region, numerous epigenetic modifiers, which remain to be investigated, may also influence the results.

5. Conclusions

The integration of clinical, imaging, biochemical, and genetic data allows a more complete understanding of CP pathogenesis. Environmental triggers, such as hypoxia, hemorrhage, and infection, act synergistically with MMP2 promoter variants to enhance matrix degradation and vascular permeability. Early identification of such variants, in combination with MRI and biochemical markers, could improve risk prediction and enable timely neuroprotective interventions.

Our data show that specific SNPs in the MMP2 promoter—namely the −1575 A, −1306 T, and −790 G alleles, either individually or as part of the ATG haplotype—are associated with the development of CP and positive MRI findings in children who experienced an acute hypoxic–ischemic event during birth. Therefore, these polymorphisms could potentially serve as diagnostic predictors of serious neurological outcomes of perinatal asphyxia.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: N.C. and T.D.; methodology: N.C., T.D. and N.M.; writing—original draft preparation: A.D.U.; writing—review and editing: N.C., T.D., I.N. and D.P.; data collection and database formatting: A.D.U., N.C., B.J., and M.D.P.; laboratory analysis: A.D.U., M.R., M.P. and N.S.; statistical analysis: T.D., N.M. and M.G.; funding acquisition: I.N. and T.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development, and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia [Grant No. 451-03-66/2024-03/200110].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethical Committee of the Clinic of Neurology and Psychiatry for Children and Youth (Approval Code: 1-109/2; Approval Date: 27 December 2017), as well as the Ethical Commission of the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Belgrade (Approval Code: 1322/IV-5; Approval Date: 18 April 2022). This study is part of the PhD thesis of the first author A.D.U.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from parents of all children involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used Grammarly Pro for the purposes of English language polishing. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gillam-Krakauer, M.; Shah, M.; Gowen, C.W., Jr. Birth Asphyxia. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hakobyan, M.; Dijkman, K.P.; Laroche, S.; Naulaers, G.; Rijken, M.; Steiner, K.; van Straaten, H.L.M.; Swarte, R.M.C.; Ter Horst, H.J.; Zecic, A.; et al. Outcome of Infants with Therapeutic Hypothermia after Perinatal Asphyxia and Early-Onset Sepsis. Neonatology 2019, 115, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viaroli, F.; Cheung, P.Y.; O’Reilly, M.; Polglase, G.R.; Pichler, G.; Schmolzer, G.M. Reducing Brain Injury of Preterm Infants in the Delivery Room. Front. Pediatr. 2018, 6, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Distefano, G.; Pratico, A.D. Actualities on molecular pathogenesis and repairing processes of cerebral damage in perinatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2010, 36, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novak, I.; Morgan, C.; Adde, L.; Blackman, J.; Boyd, R.N.; Brunstrom-Hernandez, J.; Cioni, G.; Damiano, D.; Darrah, J.; Eliasson, A.C.; et al. Early, Accurate Diagnosis and Early Intervention in Cerebral Palsy: Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment. JAMA Pediatr. 2017, 171, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, H.K.; Rosenbaum, P.; Paneth, N.; Dan, B.; Lin, J.P.; Damiano, D.L.; Becher, J.G.; Gaebler-Spira, D.; Colver, A.; Reddihough, D.S.; et al. Cerebral palsy. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 15082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- eurUS.brain group; Agut, T.; Alarcon, A.; Cabañas, F.; Bartocci, M.; Martinez-Biarge, M.; Horsch, S. Preterm white matter injury: Ultrasound diagnosis and classification. Pediatr. Res. 2020, 87, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horber, V.; Grasshoff, U.; Sellier, E.; Arnaud, C.; Krageloh-Mann, I.; Himmelmann, K. The Role of Neuroimaging and Genetic Analysis in the Diagnosis of Children With Cerebral Palsy. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 628075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolosowicz, M.; Prokopiuk, S.; Kaminski, T.W. The Complex Role of Matrix Metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) in Health and Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behl, T.; Kaur, G.; Sehgal, A.; Bhardwaj, S.; Singh, S.; Buhas, C.; Judea-Pusta, C.; Uivarosan, D.; Munteanu, M.A.; Bungau, S. Multifaceted Role of Matrix Metalloproteinases in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Pathophysiological and Therapeutic Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svedin, P.; Hagberg, H.; Savman, K.; Zhu, C.; Mallard, C. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 gene knock-out protects the immature brain after cerebral hypoxia-ischemia. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 1511–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, G.A. Matrix metalloproteinases and their multiple roles in neurodegenerative diseases. Lancet Neurol. 2009, 8, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajewska, B.; Sliwinska-Mosson, M. Association of MMP-2 and MMP-9 Polymorphisms with Diabetes and Pathogenesis of Diabetic Complications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samah, N.; Ugusman, A.; Hamid, A.A.; Sulaiman, N.; Aminuddin, A. Role of Matrix Metalloproteinase-2 in the Development of Atherosclerosis among Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. Mediat. Inflamm. 2023, 2023, 9715114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, S.A.; Dykes, D.D.; Polesky, H.F. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988, 16, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabriel, S.B.; Schaffner, S.F.; Nguyen, H.; Moore, J.M.; Roy, J.; Blumenstiel, B.; Higgins, J.; DeFelice, M.; Lochner, A.; Faggart, M.; et al. The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science 2002, 296, 2225–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, J.M.; van Essen, P.; van Karnebeek, C.D.M. Cerebral palsy and related neuromotor disorders: Overview of genetic and genomic studies. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2022, 137, 399–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, A.J.; Bennet, L. Fetal hypoxia insults and patterns of brain injury: Insights from animal models. Clin. Perinatol. 2009, 36, 579–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakkarapani, E.; de Vries, L.S.; Ferriero, D.M.; Gunn, A.J. Neonatal encephalopathy and hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: The state of the art. Pediatr. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torn, A.E.; Hesselman, S.; Johansen, K.; Agren, J.; Wikstrom, A.K.; Jonsson, M. Outcomes in children after mild neonatal hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy: A population-based cohort study. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol 2023, 130, 1602–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, L.S.; Groenendaal, F. Patterns of neonatal hypoxic-ischaemic brain injury. Neuroradiology 2010, 52, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, J.J. Cerebral white matter injury of the premature infant-more common than you think. Pediatrics 2003, 112, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rees, P.; Callan, C.; Chadda, K.R.; Vaal, M.; Diviney, J.; Sabti, S.; Harnden, F.; Gardiner, J.; Battersby, C.; Gale, C.; et al. Preterm Brain Injury and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2022, 150, e2022057442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, H.C.; Nash, K.B.; Bonifacio, S.L.; Barkovich, A.J.; Ferriero, D.M.; Sullivan, J.E.; Cilio, M.R. Seizures and magnetic resonance imaging-detected brain injury in newborns cooled for hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. J. Pediatr. 2011, 159, 731–735.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horber, V.; Sellier, E.; Horridge, K.; Rackauskaite, G.; Andersen, G.L.; Virella, D.; Ortibus, E.; Dakovic, I.; Hensey, O.; Radsel, A.; et al. The Origin of the Cerebral Palsies: Contribution of Population-Based Neuroimaging Data. Neuropediatrics 2020, 51, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerrie, S.K.; Frayn, C.S.; Navarro, O.M. Differential Diagnosis of Echogenic Lesions at Neonatal Head US. Radiographics 2025, 45, e240065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, S.J.; Greaves, D.R.; Watkins, H. Identification of novel, functional genetic variants in the human matrix metalloproteinase-2 gene: Role of Sp1 in allele-specific transcriptional regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 7549–7558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Taylor, J.A. SNPinfo: Integrating GWAS and candidate gene information into functional SNP selection for genetic association studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, W600–W605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, L.D.; Kellis, M. HaploReg: A resource for exploring chromatin states, conservation, and regulatory motif alterations within sets of genetically linked variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, D930–D934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Fornes, O.; Stigliani, A.; Gheorghe, M.; Castro-Mondragon, J.A.; van der Lee, R.; Bessy, A.; Cheneby, J.; Kulkarni, S.R.; Tan, G.; et al. JASPAR 2018: Update of the open-access database of transcription factor binding profiles and its web framework. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D260–D266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan, M.E.; Maclennan, A.H.; Gibson, C.S.; McMichael, G.L.; Haan, E.A.; Broadbent, J.L.; Baghurst, P.A.; Goldwater, P.N.; Dekker, G.A.; Australian Collaborative Cerebral Palsy Research, G. Genetic and clinical contributions to cerebral palsy: A multi-variable analysis. J. Paediatr. Child. Health 2013, 49, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.B.; Kim, J.C.; Yoon, B.H.; Romero, R.; Kim, G.; Oh, S.Y.; Kim, M.; Shim, S.S. Amniotic fluid matrix metalloproteinase-8 and the development of cerebral palsy. J. Perinat. Med. 2002, 30, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah, M.M.; Abdelmawla, M.A.; Eid, S.R.; Hasanin, R.M.; Mostafa, E.A.; Abdelhameed, M.W. Role of Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 in Neonatal Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 7, 2114–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maqsood, K.; Chuhdary, W.; Naveed, H.; Roohi, N. Matrix metalloproteinases and biochemical dysregulation in pediatric cerebral palsy: A clinical perspective. Egypt. Pediatr. Assoc. Gaz. 2025, 73, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemska, S.; Serio, S.; Larcher, V.; Beltrame, G.; Portinaro, N.M.; Bang, M.L. Whole Genome Expression Profiling of Semitendinosus Tendons from Children with Diplegic and Tetraplegic Cerebral Palsy. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handsfield, G.G.; Williams, S.; Khuu, S.; Lichtwark, G.; Stott, N.S. Muscle architecture, growth, and biological Remodelling in cerebral palsy: A narrative review. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2022, 23, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocenasova, A.; Shawkatova, I.; Javor, J.; Parnicka, Z.; Minarik, G.; Kralova, M.; Kiralyova, I.; Mikolaskova, I.; Durmanova, V. MMP2 rs243866 and rs2285053 Polymorphisms and Alzheimer’s Disease Risk in Slovak Caucasian Population. Life 2023, 13, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, J.H.; Guo, S.; Lok, J.; Navaratna, D.; Whalen, M.J.; Kim, K.W.; Lo, E.H. Neurovascular matrix metalloproteinases and the blood-brain barrier. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2012, 18, 3645–3648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bednarek, N.; Svedin, P.; Garnotel, R.; Favrais, G.; Loron, G.; Schwendiman, L.; Hagberg, H.; Morville, P.; Mallard, C.; Gressens, P. Increased MMP-9 and TIMP-1 in mouse neonatal brain and plasma and in human neonatal plasma after hypoxia-ischemia: A potential marker of neonatal encephalopathy. Pediatr. Res. 2012, 71, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranasinghe, H.S.; Williams, C.E.; Christophidis, L.J.; Mitchell, M.D.; Fraser, M.; Scheepens, A. Proteolytic activity during cortical development is distinct from that involved in hypoxic ischemic injury. Neuroscience 2009, 158, 732–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).