Abstract

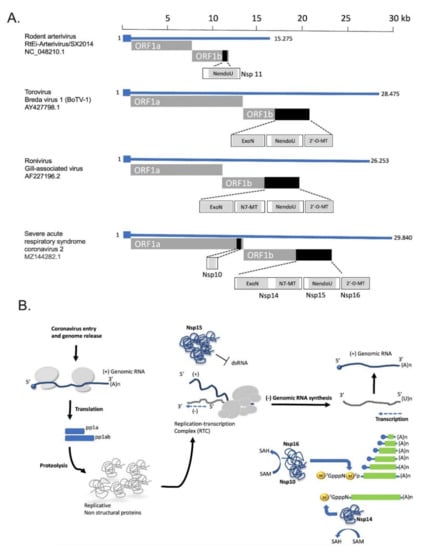

Viral RNA sensing triggers innate antiviral responses in humans by stimulating signaling pathways that include crucial antiviral genes such as interferon. RNA viruses have evolved strategies to inhibit or escape these mechanisms. Coronaviruses use multiple enzymes to synthesize, modify, and process their genomic RNA and sub-genomic RNAs. These include Nsp15 and Nsp16, whose respective roles in RNA capping and dsRNA degradation play a crucial role in coronavirus escape from immune surveillance. Evolutionary studies on coronaviruses demonstrate that genome expansion in Nidoviruses was promoted by the emergence of Nsp14-ExoN activity and led to the acquisition of Nsp15- and Nsp16-RNA-processing activities. In this review, we discuss the main RNA-sensing mechanisms in humans as well as recent structural, functional, and evolutionary insights into coronavirus Nsp15 and Nsp16 with a view to potential antiviral strategies.

1. Introduction

Viral infections are classified among the most devastating infectious phenomena, and in certain cases are responsible for the generation of severe pathogenic phenotypes that characterize well-known human diseases [1,2]. The recent dramatic example of severe acute respiratory virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) spreading among human populations and the subsequent generation and establishment of the COVID-19 pandemic [3,4] exemplifies the capacity of RNA viruses to cause a heavy impact on the global health system. In humans, as the first line of defense against RNA viruses, specific proteins have evolved to sense viral RNA and trigger innate immunity in the early infection phase. On the other hand, the coevolution of RNA viruses with humans has led to a wide variety of viral mechanisms that evade this sensing. Here, we aim to provide a comprehensive update on the role of coronavirus Nsp15- and Nsp16-RNA-processing activities in innate immune escape.

2. Classification of RNA Viruses

In prokaryotes, most viruses harbor double-stranded (ds) DNA as genome, while single-stranded (ss) DNA viruses are significantly fewer and there is only a limited presence of RNA viruses. On the contrary, viruses with RNA genomes dominate the eukaryotic virome. The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) reports 158 RNA virus species compared to 91 DNA virus species that infect humans [5]. Based on the nature of their genome, RNA viruses are classified as positive-sense (+) RNA viruses, double-stranded (ds) RNA viruses, and negative-sense (-) RNA viruses [6]. Positive-sense (+) single-stranded (ss) RNA viruses that are characterized as human pathogens, belong to Enteroviridae (e.g., Poliovirus), Flaviviridae (e.g., Hepatitis C, Zika virus), Picornaviridae (e.g., poliovirus), Caliciviridae (e.g., norovirus), and Coronaviridae (e.g., SARS-CoV-1) virus families. Since very few treatment options exist, infection by (+)ssRNA viruses represents a major health burden that hardly affects modern societies [7].

The members of (+)ssRNA viruses are characterized by small genomes that rarely exceed 30 kb in size and evolve fast due to the relatively high mutation rate during their replication process and the short generation times [8,9,10]. Despite their limited coding potential, these viruses can replicate efficiently in infected host cells utilizing host proteins and membranes. Their genetic variability due to the high mutation rate allows quick adaptation to environmental changes and promotes resistance to antiviral agents and immune escape from antibodies.

Despite the evolutionary divergence within the group of (+)ssRNA viruses, its members share common features in their replication processes within the host cell. Their replication takes place at the cytoplasmic membranes of the infected cells and is characterized by regulated coordination of RNA synthesis that is mediated by the viral replication complex. Besides the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), this protein complex consists of a core of viral enzymes with protease and RNA helicase activities that are common among most (+)ssRNA viruses. The positive-sense single-stranded RNA genome can be directly translated into viral proteins upon release into the cytoplasm of a host cell. After completion of this translation process, viral replication proteins recruit the viral (+)RNA. Intracellular membranes play an essential role in this step as they can form anchor sites for the assembly of viral RNA replication complexes (VRCs). Moreover, host membranes and proteins may protect and concentrate viral RNAs, and also isolate the replication intermediates from templates during the replication steps [11]. In the next step, the synthesized virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) generates complementary negative-sense RNA (−RNA), that can be used as a template for the synthesis of additional +RNAs. At an early time post-infection, the population of newly synthesized +RNAs enters a new cycle of translation and replication, while at a later time, +RNA is directed to form new infectious virus particles by encapsulation [12,13,14]. The translation to replication switch for +RNAs is quite essential for virus reproduction.

3. Sensors for Long Double-Stranded Viral RNA and Innate Immunity

Recognition of virus-derived nucleic acids is among the most important processes of the host cell defense. During the replication of positive single-stranded RNA viruses (+ssRNA), RNA-replication intermediates such as double-stranded RNA molecules (dsRNA) of more than 30-bp length accumulate. Detection of dsRNAs by specific host protein sensors such as RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs), the protein kinase R (PKR), and oligoadenylate synthetases (OASes) represent some of the central mechanisms of interferon (IFN) pathway activation in infected cells [15].

One of the best-studied RLRs with binding activity of non-self dsRNA is the RIG-I (retinoic acid-inducible gene-I), a DExD/H box RNA helicase important for the activation of transcription factors such as IRF3 and NF-κB [16]. RIG-I is a critical regulator for the detection and eradication of the replicating viral genomes. Additionally, MDA5 (melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5), encoded by the IFIH1 gene in humans, belongs to the same family of cytoplasmic RNA sensors.

Upon dsRNA binding, these proteins activate the mitochondrial membrane localized adaptor MAVS which in turn, recruits multiple factors (TRAF3, TRAF6, TANK) that promote the formation of a MAVS signaling complex. The latter induces the phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) and interferon regulatory factor 7 (IRF7) as well as the activation of NF-κB [17]. This MAVS-mediated signaling leads to transcriptional activation of type I interferons (IFNs-I) and other proinflammatory cytokines and antiviral genes [17,18]. It is considered that short double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) molecules are more efficiently recognized by RIG-I while MDA5 is activated by longer dsRNAs. In consistency with this pattern of recognition, several studies have shown that RIG-I preferentially recognizes dsRNA signatures by Sendai virus (SeV), vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), influenza A virus (FLUA), and hepatitis C virus (HCV), while encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV), norovirus, and murine hepatitis virus (MHV) activate MDA5 [19].

PKR is a dsRNA-dependent protein kinase and is transcriptionally upregulated by interferon. This protein exists in an auto-repressed monomeric state and dsRNA binding activates its dimerization and its catalytic activity [20]. Phosphorylation of the eukaryotic translational initiation factor eIF2α by activated PKR suppresses cap-dependent translational initiation. Thus, activation of PKR leads to the protein synthesis shutdown and viral replication inhibition [21]. Besides the direct role of activated PKR in protein translation inhibition, several studies link activated PKR with antiviral interferon and apoptotic signaling pathways since PKR affects diverse transcriptional factors such as IRF1, STATs, p53, ATF-3, and NF-κB [22,23,24].

The oligoadenylate synthetase family consists of interferon-induced enzymes (OASes) that upon binding to virally produced dsRNA synthesize 2′−5′ phosphodiester–linked oligoadenylates (2–5 An) which in turn activate the endoribonuclease RNase L within infected cells [25]. Activated RNase L cleaves a wide range of viral and cellular RNAs, including rRNA, tRNA, and mRNA with no sequence specificity and thus induces cell death [26].

Eukaryotic cells have evolved complex networks of specialized response systems to numerous extracellular stimuli, leading to the formation of transcriptional complexes across the appropriate regions of the genome. Virus-inducible gene expression is regulated by virus-activated transcription factors (e.g., NF-κB, IRFs), cis-regulatory elements of the genome such as enhancers, and local chromatin structure [27,28]. The binding of virus-activated transcription factors to specific DNA-binding sites within an enhancer can lead to the assembly of multicomponent complexes termed enhanceosomes, that are critical for gene expression regulation (e.g., the prototype IFN-β enhanceosome) [28,29]. Furthermore, the immune master regulators NF-κB and IRF3 cooperate extensively during innate antiviral transcription in human cells, as shown by a comprehensive genome-wide analysis [30]. Thus, upon detection of (ds)RNAs by specific host protein sensors and upregulation of type I interferon levels, the secreted IFN-I (IFN-α and IFN-β) binds to the IFN receptors (IFNARs) on the surface of the infected and neighboring cells in a paracrine or autocrine manner [31,32] thus commuting the signal of virus-infection, by activating the Janus kinase 1 (JAK1) and tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2), which in turn phosphorylate the signal transducer and activator of transcription proteins 1 and 2 (STAT1 and STAT2) [33].

Phosphorylated STAT1 and STAT2 form a heterodimer, which binds IRF9 to form the trimeric complex called IFN-stimulated gene factor 3 (ISGF3) [34]. The nuclear function of ISGF3 includes binding to IFN-I-stimulated response elements (ISREs), which in turn trigger the expression of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) that encode proteins with antiviral role [35,36]. The network of ISG-encoded proteins establishes an anti-viral state that leads to the inhibition of viral transcription, translation, and replication as well as to the degradation of the viral genome [37,38].

6. Replication-Associated Mechanisms that Contribute to Innate Immunity Evasion

Besides the function of specific viral proteins as interferon antagonists, coronaviruses have evolved several strategies to evade innate immunity. First, coronaviruses replicate in the interior of double-membrane vesicles which prevents recognition of dsRNA replication intermediates by host proteins that sense viral RNA structures [68,69,70]. The expression of hydrophobic viral proteins such as the Nsp3 and Nsp4 of CoVs seems to favor the formation of these replication vesicles that protect the viral dsRNA replication intermediates from innate immune sensors of the cytosol [71].

Like many RNA viruses, coronaviruses protect the 5′ end of their RNA genome and subgenomic RNAs from degradation and evade recognition from the host RNA sensor proteins of the innate immune system by a cap structure generated during replication. More specifically, the viral cap structure at the 5′ end of the RNA molecule consists of a N-methylated guanosine triphosphate and a C2′-O-methyl-ribosyladenine. This structure resembles the cap of eukaryotic mRNA. Viral proteins Nsp14 and Nsp16 catalyze the methylation of the cap on the guanine of the GTP and the C2′ hydroxyl group of the following nucleotide, respectively. Both Nsp14 and Nsp16 are S-adenosylmethionine (SAM)-dependent methyltransferases (MTases). Since host sensor proteins of viral RNA recognize the 5′ cap in order to distinguish the host mRNA from viral RNA, this structure protects coronavirus RNA from recognition by Mda5 and thus prevents Mda5-driven interferon upregulation in virus-infected cells [72]. The important role of cap formation for coronavirus life cycle and immune escape was highlighted by the low virulence of MERS and SARS-CoV strains harboring mutant Nsp16 [73,74].

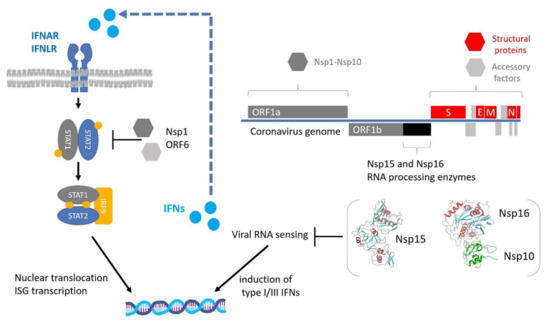

Another conserved molecular mechanism associated with innate immune evasion in coronaviruses includes the degradation of dsRNA intermediates by viral proteins with processing activity. Coronavirus encoded Nsp15 protein, a uridine-specific endoribonuclease conserved across coronaviruses is an integral component of the coronaviral replicase-transcriptase complex (RTC) that processes viral RNA to evade detection by host defense systems. This protein is considered a member of the nidoviral EndoU (NendU) family. It is well accepted that Nsp15 uridylate-specific nucleolytic activity on single-stranded and dsRNA limits the formation of dsRNA intermediates and thus inhibits the ability of specific cytoplasmic viral RNA sensors to activate the IFN-I response of innate immunity to infection [75,76]. In this context, loss of Nsp15 nuclease activity in porcine epidemic diarrhea coronavirus (PEDV) leads to the activation of interferon responses and reduced viral titers in infected piglets [77]. Similarly, in vivo experiments with mice infected with MHV strains harboring deficient Nsp15 nuclease, revealed that these infections were associated with attenuated viral replication [78]. Long polyuridine tracts at the 5′-end of negative-strand viral RNA are known to promote host interferon response. The finding that negative-stranded viral RNA intermediates in infected cells with MHV strains harboring catalytically inactive Nsp15, is enriched in polyuridine tracts, further supports the role of Nsp15 in innate immune evasion [75]. The synergism between Nsp15 and Nsp16 and other expressed coronavirus proteins in innate immunity escape is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Innate immune evasion by coronaviruses. Upon viral RNA sensing, the expression of type I and III interferons (IFNs) is activated. IFNs are secreted in an autocrine and paracrine manner to induce the expression of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) through the STAT1/2 signaling pathway. RNA-processing enzymes Nsp15 and Nsp16 are essential for the escape from viral RNA sensing, while other expressed non-structural or accessory proteins inhibit the STAT1/2 pathway. The regions encoding for the NSP15 and NSP16 proteins are highlighted with black color and their 3D structures are displayed in cartoon representation based on PDB files 6WXC and 6WVN respectively.

9. Cleavage of dsRNA Intermediates: Structural and Evolutionary Aspects of CoV Nsp15 Protein

NendoU endoribonuclease activity has been functionally assigned to Nsp15 protein among different human (HCoV-229E, SARS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2) and animal coronaviruses (MHV) [103,104,105]. Biochemical characterization of the recombinant Nsp15 has indicated that it specifically recognizes uridine moiety and cleaves RNA substrates at the 3′ of target polyuridine tracks through the formation of a 2′-3′ cyclic phosphodiester product [106]. Experiments with bacterially expressed forms of NendoU of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus and HCoV-229E showed that Nsp15 is able to cleave single-stranded RNA but the preferred substrate is double-stranded RNA (dsRNA). Notably, the endonucleolytic activity of Nsp15 is strictly dependent on Mn2+ metal ions [89]. During the coronavirus replication process, Nsp15 cleaves the 5′-polyuridine tracts in (-)-sense viral RNAs that are specifically recognized by the host dsRNA sensor MDA5, impairing innate immune responses [75]. There is a high degree of Nsp15 sequence similarity among coronaviruses. The SARS-CoV-2 Nsp15 shares 88% sequence identity with its known closest homolog from SARS-CoV, 50% sequence identity with the homolog from MERS, and 43% identity with the HCoV-229E homolog. Among Nsp15 endoribonucleases, crystal structures from MHV, SARS, MERS, and HCoV-229E have been reported [107,108,109,110,111]. According to these structural studies, the 39 kDa protein folds into three domains: N-terminal, middle domain, and the C-terminal catalytic NendoU domain. Notably, all these studies support a hexamer model made of dimers of trimers. Specific secondary structure elements of the Nsp15 catalytic domain are conserved in the distant homolog, XendoU, providing further evidence that belong to a common endoribonuclease family [90]. However, Nsp15 structure does not share structural similarities with other characterized ribonucleases, suggesting that this protein adopts a novel folding [108]. Recently, the crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 Nsp15 demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 Nsp15 folding is similar to the SARS-CoV, H-CoV-229E, and MERS-CoV homologs [105,112]. The catalytic function of Nsp15 resides in the C-terminal NendoU domain. Within this domain, the main chain architecture and the key catalytic residues His235, His250, Lys290, Thr341, Tyr343, and Ser294 (based on SARS-CoV-2 PDB 6VWW) of the active site are conserved among SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV homolog structures. The residues His235, His250, and Lys290 have been proposed to form the catalytic triad, based on the superimposition analysis with the catalytic center of bovine RNase A (His12, His119, and Lys41 based on PDB 5OGH_A). Although the catalytic mechanism of NendoU has not been analyzed in detail, the conservation of the catalytic triad suggests that it may be similar to that of RNase A. In this context, both histidine residues (His235 and His250) act as a general base and general acid in order to promote cleavage. This is also supported by the generation of 2′-3′ cyclic phosphodiester products [113]. However, it is worth noting that the important role of Mn2+ ions for SARS-CoV-2 Nsp15 catalysis is conflicting with the proposed RNase A-like reaction mechanism since RNaseA catalysis is metal independent.

10. Drugs Targeting Nsp15 and Nsp16 Proteins

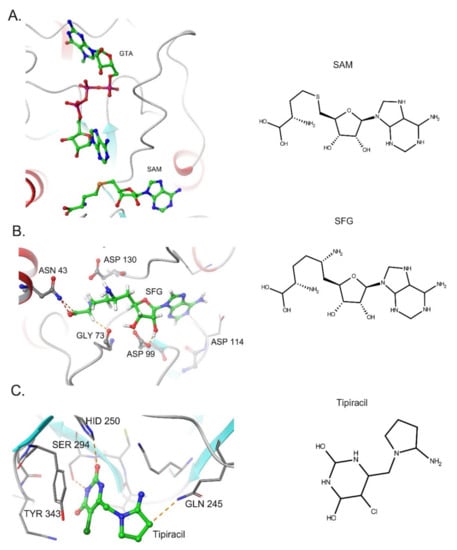

As emphasized above, Nsp15 and Nsp16 activity are important for SARS-CoV-2 innate immune escape during the viral cycle. Thus, the development of molecules capable of inhibiting these proteins might open new treatment avenues to restore viral RNA recognition and stimulate the host antiviral response against SARS-CoV-2. Recent studies have shown that Nsp16 2′ O-MTase activity can be suppressed by conventional SAM antagonists. For instance, sinefungin (SFG)—a SAM analog—efficiently binds the SAM-binding site of SARS-CoV-2 Nsp16, inhibiting its activity [101] (Figure 3A,B). Crystallographic and biochemical studies have indicated that Nsp10 promotes the stabilization of the Nsp16 SAM-binding pocket and favors the extension of Nsp16 RNA-binding groove[100,101]. Therefore, molecules that can disrupt the Nsp10-Nsp16 interaction or inhibit complex formation are considered putative candidate antivirals. In this context, peptides derived from the conserved interaction between Nsp10 and Nsp16 exhibit an inhibitory effect on 2′-O-MTase activity in vitro [114].

Figure 3.

Inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 Nsp15 and Nsp16 proteins. (A). Structure of Nsp16 in Complex with 7-methyl-GpppA (GTA) and S-Adenosylmethionine (PDB: 6WVN). (B) Binding of Sinefungin (SFG) in SARS-Cov-2 NSP16 (PDB: 6WKQ). (C). Structure of NSP15 Endoribonuclease from SARS CoV-2 in the Complex with drug Tipiracil (PDB: 6WXC).

The analysis of Nsp16:Nsp10 crystallographic data for MERS, SARS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2 have indicated that RNA guanosine cap binds to a region adjacent to the SAM-binding pocket, placing its ribose ring in close proximity to the amino group of SAM [100,101,115]. The binding affinity of different nucleoside/cap analogs in these pockets has been also investigated in viral 2′-O-MTases as candidate antiviral drugs [116]. Notably the GTP analog ribavirin triphosphate has been reported to suppress dengue virus 2′-O MTase activity [117,118]. The design of SAM analogues that also interacts with this adjacent cap-binding site is a challenge for the generation of more potent and specific inhibitors compared to sinefungin [115,119]. In this direction, several groups have performed virtual screening and molecular docking in order to identify alternative candidate drugs [120,121,122].

Nsp15 protein is an attractive target in the field of drug design as it is exclusively present in nidoviruses with no close human homologs identified. Since structural studies indicate a high degree of similarity between the catalytic sites of CoV Nsp15 and RNase A, and a common catalytic mechanism, small molecule inhibitors of RNase A were among the first drugs tested for their ability to inhibit Nsp15 activity. In this direction, Benzopurpurin B and Congo red were shown to display the higher inhibition on Nsp15 activity. In addition, these drugs reduced the infectivity of the SARS-CoV in Vero cells [123]. Based on this evidence, a more comprehensive investigation is needed for the exploitation of RNAse A inhibitors as drugs that can target Nsp15 activity.

Using the available crystallographic data for NSP15 from MERS, SARS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2, several groups have employed virtual screening, molecular docking, and molecular dynamic simulation techniques to identify putative antivirals against Nsp15 [123,124]. Nsp15 is a uridine-specific endoribonuclease and amino acid residue Ser294 has been proposed to play a crucial role in uracil recognition in the catalytic pocket [75]. Therefore, synthetic uracil competitors may represent a promising group of small molecules for drug development against Nsp15. Notably, the uracil analog Tipiracil has been shown to bind the uracil site in the catalytic pocket of SARS-CoV-2 Nsp15 as a competitive inhibitor and suppresses its activity in vitro experiments [125] (Figure 3B).

11. Conclusions

RNA viral recognition by cytosolic RNA sensors can stimulate the type I and III IFNs production that in turn, establish the cellular antiviral response and activate the adaptive immunity. The co-evolution of RNA viruses with their host has led to the emergence of viral evasion mechanisms of intracellular RNA sensing. Upon early phases of coronavirus infection, IFN response appears to be reduced and delayed indicating an innate immune escape. At the molecular level, the cap structure formation to the 5′ end of the viral genome and subgenomic transcripts and the degradation of dsRNA intermediates that are produced during replication is considered to hide coronaviruses from host sensor proteins that are able to stimulate the IFN signaling pathway. In the current review, the specific function of coronavirus-encoded enzymes Nsp15 and Nsp16 on dsRNA degradation and viral cap methylation respectively, have been discussed. These RNA-processing proteins and the associated innate immune escape mechanisms have evolved in nidovirales after the acquisition of the proofreading exoribonuclease (ExoN) activity and the expansion of their genomes. This suggests that the specific innate immune escape profile of coronaviruses has been developed in close association with complex evolutionary processes related to gain of Nsp14 proofreading activity, and genome expansion events. Progress in the field of coronavirus genome replication biology will allow us to understand how evolution can lead to the acquisition of new RNA enzymatic activities, which in turn provides the capability to modulate the innate immune response. It is characteristic that Nsp15 is exclusively present only in nidovirales evolutionary clade. Since coronaviruses use host proteins as part of their replication processes, it has also become clear that Nsp15 and Nsp16 protein evolution and function were affected by virus–host interactions. For instance, it has been proposed that NSP15 degrades the excess amount of dsRNA that escapes from replication-transcription complexes in the inner core of cytoplasmic vesicles that are formed by host membranes and proteins. Since the innate immune escape mechanisms are based on complex virus–host interactions, it is possible that Nsp15 and Nsp16 RNA-processing enzymes have evolved to synergize with other viral Nsp proteins that function as IFN antagonists to counteract anti-viral immune responses.

Numerous studies have highlighted the importance of bypassing or modulating innate immune defense for coronavirus replication. A key challenge is to translate this knowledge into useful applications for the development of new antivirals. In this direction, the pharmacological inhibition of Nsp15 and Nsp16 proteins may potently induce antiviral responses for long-lasting immunity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B., G.S. and T.R.; writing—original draft preparation, G.M., M.A.K. and M.A.; writing—review and editing, all authors.; supervision, project administration, T.R. and A.B.; funding acquisition for APC, T.R. and A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors apologize to all those colleagues whose important contributions could not be cited owing to space constraints.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Foxman, E.F.; Iwasaki, A. Genome-virome interactions: Examining the role of common viral infections in complex disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 9, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasaki, A.; Pillai, P.S. Innate immunity to influenza virus infection. Nat. Rev. Immunol 2014, 14, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreakos, E.; Tsiodras, S. COVID-19: Lambda interferon against viral load and hyperinflammation. EMBO Mol. Med. 2020, 12, e12465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J.; Wu, W.; Li, S.; Hu, Y.; Hu, M.; Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Huang, T.; Zheng, K.; Wang, Y.; et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of critically ill patients with novel coronavirus infectious disease (COVID-19) in China: A retrospective multicenter study. Intensive Care Med. 2020, 46, 1863–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolhouse, M.E.J.; Adair, K. The diversity of human RNA viruses. Future Virol. 2013, 8, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltimore, D. Viral genetic systems. Trans. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1971, 33, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonin, E.V.; Dolja, V.V.; Krupovic, M.; Varsani, A.; Wolf, Y.I.; Yutin, N.; Zerbini, F.M.; Kuhn, J.H. Global Organization and Proposed Megataxonomy of the Virus World. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2020, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.; Spindler, K.; Horodyski, F.; Grabau, E.; Nichol, S.; VandePol, S. Rapid evolution of RNA genomes. Science 1982, 215, 1577–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, J.W.; Holland, J.J. Mutation rates among RNA viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 13910–13913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, S.; Shackelton, L.A.; Holmes, E.C. Rates of evolutionary change in viruses: Patterns and determinants. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008, 9, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, P.D.; Pogany, J. The dependence of viral RNA replication on co-opted host factors. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 10, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggen, J.; Thibaut, H.J.; Strating, J.; van Kuppeveld, F.J.M. The life cycle of non-polio enteroviruses and how to target it. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 368–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrows, N.J.; Campos, R.K.; Liao, K.C.; Prasanth, K.R.; Soto-Acosta, R.; Yeh, S.C.; Schott-Lerner, G.; Pompon, J.; Sessions, O.M.; Bradrick, S.S.; et al. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology of Flaviviruses. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 4448–4482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorne, L.G.; Goodfellow, I.G. Norovirus gene expression and replication. J. Gen. Virol. 2014, 95, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiss, G.; Jin, G.; Guo, J.; Bumgarner, R.; Katze, M.G.; Sen, G.C. A comprehensive view of regulation of gene expression by double-stranded RNA-mediated cell signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 30178–30182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoneyama, M.; Kikuchi, M.; Natsukawa, T.; Shinobu, N.; Imaizumi, T.; Miyagishi, M.; Taira, K.; Akira, S.; Fujita, T. The RNA helicase RIG-I has an essential function in double-stranded RNA-induced innate antiviral responses. Nat. Immunol. 2004, 5, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehwinkel, J.; Gack, M.U. RIG-I-like receptors: Their regulation and roles in RNA sensing. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 537–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Hur, S. How RIG-I like receptors activate MAVS. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2015, 12, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez David, R.Y.; Combredet, C.; Sismeiro, O.; Dillies, M.A.; Jagla, B.; Coppee, J.Y.; Mura, M.; Guerbois Galla, M.; Despres, P.; Tangy, F.; et al. Comparative analysis of viral RNA signatures on different RIG-I-like receptors. Elife 2016, 5, e11275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanduri, S.; Rahman, F.; Williams, B.R.; Qin, J. A dynamically tuned double-stranded RNA binding mechanism for the activation of antiviral kinase PKR. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 5567–5574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, J.; Alcami, J.; Esteban, M. Induction of apoptosis by double-stranded-RNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR) involves the alpha subunit of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 and NF-kappaB. Mol. Cell Biol. 1999, 19, 4653–4663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, O.; Pichlmair, A.; Rehwinkel, J.; Rogers, N.C.; Scheuner, D.; Kato, H.; Takeuchi, O.; Akira, S.; Kaufman, R.J.; Reis e Sousa, C. Protein kinase R contributes to immunity against specific viruses by regulating interferon mRNA integrity. Cell Host. Microbe. 2010, 7, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamanian-Daryoush, M.; Mogensen, T.H.; DiDonato, J.A.; Williams, B.R. NF-kappaB activation by double-stranded-RNA-activated protein kinase (PKR) is mediated through NF-kappaB-inducing kinase and IkappaB kinase. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000, 20, 1278–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, A.M.; Santa Maria, F.G.; Lahiri, T.; Friedman, E.; Marie, I.J.; Levy, D.E. PKR Transduces MDA5-Dependent Signals for Type I IFN Induction. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, R.; Justesen, J.; Sarkar, S.N.; Sen, G.C.; Yee, V.C. Crystal structure of the 2′-specific and double-stranded RNA-activated interferon-induced antiviral protein 2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase. Mol. Cell 2003, 12, 1173–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Donovan, J.; Rath, S.; Whitney, G.; Chitrakar, A.; Korennykh, A. Structure of human RNase L reveals the basis for regulated RNA decay in the IFN response. Science 2014, 343, 1244–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agelopoulos, M.; Thanos, D. Epigenetic determination of a cell-specific gene expression program by ATF-2 and the histone variant macroH2A. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 4843–4853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanos, D.; Maniatis, T. Virus induction of human IFN beta gene expression requires the assembly of an enhanceosome. Cell 1995, 83, 1091–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomvardas, S.; Thanos, D. Modifying gene expression programs by altering core promoter chromatin architecture. Cell 2002, 110, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freaney, J.E.; Kim, R.; Mandhana, R.; Horvath, C.M. Extensive cooperation of immune master regulators IRF3 and NFkappaB in RNA Pol II recruitment and pause release in human innate antiviral transcription. Cell Rep. 2013, 4, 959–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitazawa, H.; Villena, J. Modulation of Respiratory TLR3-Anti-Viral Response by Probiotic Microorganisms: Lessons Learned from Lactobacillus rhamnosus CRL1505. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, A.; Iwasaki, A. Type I and Type III Interferons—Induction, Signaling, Evasion, and Application to Combat COVID-19. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 27, 870–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majoros, A.; Platanitis, E.; Kernbauer-Holzl, E.; Rosebrock, F.; Muller, M.; Decker, T. Canonical and Non-Canonical Aspects of JAK-STAT Signaling: Lessons from Interferons for Cytokine Responses. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wienerroither, S.; Shukla, P.; Farlik, M.; Majoros, A.; Stych, B.; Vogl, C.; Cheon, H.; Stark, G.R.; Strobl, B.; Muller, M.; et al. Cooperative Transcriptional Activation of Antimicrobial Genes by STAT and NF-kappaB Pathways by Concerted Recruitment of the Mediator Complex. Cell Rep. 2015, 12, 300–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, W.M.; Chevillotte, M.D.; Rice, C.M. Interferon-stimulated genes: A complex web of host defenses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 32, 513–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoggins, J.W. Interferon-Stimulated Genes: What Do They All Do? Annu. Rev. Virol. 2019, 6, 567–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoggins, J.W.; Wilson, S.J.; Panis, M.; Murphy, M.Y.; Jones, C.T.; Bieniasz, P.; Rice, C.M. A diverse range of gene products are effectors of the type I interferon antiviral response. Nature 2011, 472, 481–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacMicking, J.D. Interferon-inducible effector mechanisms in cell-autonomous immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2012, 12, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefkowitz, E.J.; Dempsey, D.M.; Hendrickson, R.C.; Orton, R.J.; Siddell, S.G.; Smith, D.B. Virus taxonomy: The database of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D708–D717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioti, K.; Kottaridi, C.; Voyiatzaki, C.; Chaniotis, D.; Rampias, T.; Beloukas, A. Animal Coronaviruses Induced Apoptosis. Life 2021, 11, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Li, F.; Shi, Z.L. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrosillo, N.; Viceconte, G.; Ergonul, O.; Ippolito, G.; Petersen, E. COVID-19, SARS and MERS: Are they closely related? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 729–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Bon, A.; Tough, D.F. Links between innate and adaptive immunity via type I interferon. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2002, 14, 432–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Melo, D.; Nilsson-Payant, B.E.; Liu, W.C.; Uhl, S.; Hoagland, D.; Moller, R.; Jordan, T.X.; Oishi, K.; Panis, M.; Sachs, D.; et al. Imbalanced Host Response to SARS-CoV-2 Drives Development of COVID-19. Cell 2020, 181, 1036–1045.e1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totura, A.L.; Baric, R.S. SARS coronavirus pathogenesis: Host innate immune responses and viral antagonism of interferon. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2012, 2, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindler, E.; Thiel, V.; Weber, F. Interaction of SARS and MERS Coronaviruses with the Antiviral Interferon Response. Adv. Virus Res. 2016, 96, 219–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjadj, J.; Yatim, N.; Barnabei, L.; Corneau, A.; Boussier, J.; Smith, N.; Pere, H.; Charbit, B.; Bondet, V.; Chenevier-Gobeaux, C.; et al. Impaired type I interferon activity and inflammatory responses in severe COVID-19 patients. Science 2020, 369, 718–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Meng, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhang, X.; Chen, W.; Sheng, J.; Qiu, Y.; Diao, H.; Li, L. Inflammation and Antiviral Immune Response Associated With Severe Progression of COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 631226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channappanavar, R.; Fehr, A.R.; Vijay, R.; Mack, M.; Zhao, J.; Meyerholz, D.K.; Perlman, S. Dysregulated Type I Interferon and Inflammatory Monocyte-Macrophage Responses Cause Lethal Pneumonia in SARS-CoV-Infected Mice. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 19, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Subbarao, K. The Immunobiology of SARS. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 25, 443–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reghunathan, R.; Jayapal, M.; Hsu, L.Y.; Chng, H.H.; Tai, D.; Leung, B.P.; Melendez, A.J. Expression profile of immune response genes in patients with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. BMC Immunol. 2005, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazear, H.M.; Schoggins, J.W.; Diamond, M.S. Shared and Distinct Functions of Type I and Type III Interferons. Immunity 2019, 50, 907–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokol, C.L.; Luster, A.D. The chemokine system in innate immunity. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2015, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheblawi, M.; Wang, K.; Viveiros, A.; Nguyen, Q.; Zhong, J.C.; Turner, A.J.; Raizada, M.K.; Grant, M.B.; Oudit, G.Y. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2: SARS-CoV-2 Receptor and Regulator of the Renin-Angiotensin System: Celebrating the 20th Anniversary of the Discovery of ACE2. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 1456–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banu, N.; Panikar, S.S.; Leal, L.R.; Leal, A.R. Protective role of ACE2 and its downregulation in SARS-CoV-2 infection leading to Macrophage Activation Syndrome: Therapeutic implications. Life Sci. 2020, 256, 117905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virgin, H.W. The virome in mammalian physiology and disease. Cell 2014, 157, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wathelet, M.G.; Orr, M.; Frieman, M.B.; Baric, R.S. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus evades antiviral signaling: Role of nsp1 and rational design of an attenuated strain. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 11620–11633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zust, R.; Cervantes-Barragan, L.; Kuri, T.; Blakqori, G.; Weber, F.; Ludewig, B.; Thiel, V. Coronavirus non-structural protein 1 is a major pathogenicity factor: Implications for the rational design of coronavirus vaccines. PLoS Pathog. 2007, 3, e109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaraj, S.G.; Wang, N.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Z.; Tseng, M.; Barretto, N.; Lin, R.; Peters, C.J.; Tseng, C.T.; Baker, S.C.; et al. Regulation of IRF-3-dependent innate immunity by the papain-like protease domain of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 32208–32221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopecky-Bromberg, S.A.; Martinez-Sobrido, L.; Frieman, M.; Baric, R.A.; Palese, P. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus open reading frame (ORF) 3b, ORF 6, and nucleocapsid proteins function as interferon antagonists. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Hauns, K.; Langland, J.O.; Jacobs, B.L.; Hogue, B.G. Mouse hepatitis coronavirus A59 nucleocapsid protein is a type I interferon antagonist. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 2554–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Dong, X.; Ma, R.; Wang, W.; Xiao, X.; Tian, Z.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Ren, L.; et al. Activation and evasion of type I interferon responses by SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konno, Y.; Kimura, I.; Uriu, K.; Fukushi, M.; Irie, T.; Koyanagi, Y.; Sauter, D.; Gifford, R.J.; Consortium, U.-C.; Nakagawa, S.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 ORF3b Is a Potent Interferon Antagonist Whose Activity Is Increased by a Naturally Occurring Elongation Variant. Cell Rep. 2020, 32, 108185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamitani, W.; Huang, C.; Narayanan, K.; Lokugamage, K.G.; Makino, S. A two-pronged strategy to suppress host protein synthesis by SARS coronavirus Nsp1 protein. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009, 16, 1134–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Lokugamage, K.G.; Rozovics, J.M.; Narayanan, K.; Semler, B.L.; Makino, S. SARS coronavirus nsp1 protein induces template-dependent endonucleolytic cleavage of mRNAs: Viral mRNAs are resistant to nsp1-induced RNA cleavage. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoms, M.; Buschauer, R.; Ameismeier, M.; Koepke, L.; Denk, T.; Hirschenberger, M.; Kratzat, H.; Hayn, M.; Mackens-Kiani, T.; Cheng, J.; et al. Structural basis for translational shutdown and immune evasion by the Nsp1 protein of SARS-CoV-2. Science 2020, 369, 1249–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strating, J.R.; van Kuppeveld, F.J. Viral rewiring of cellular lipid metabolism to create membranous replication compartments. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2017, 47, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, C.R.; Airo, A.M.; Hobman, T.C. The Virus-Host Interplay: Biogenesis of +RNA Replication Complexes. Viruses 2015, 7, 4385–4413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stertz, S.; Reichelt, M.; Spiegel, M.; Kuri, T.; Martinez-Sobrido, L.; Garcia-Sastre, A.; Weber, F.; Kochs, G. The intracellular sites of early replication and budding of SARS-coronavirus. Virology 2007, 361, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudshoorn, D.; Rijs, K.; Limpens, R.; Groen, K.; Koster, A.J.; Snijder, E.J.; Kikkert, M.; Barcena, M. Expression and Cleavage of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus nsp3-4 Polyprotein Induce the Formation of Double-Membrane Vesicles That Mimic Those Associated with Coronaviral RNA Replication. MBio 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zust, R.; Cervantes-Barragan, L.; Habjan, M.; Maier, R.; Neuman, B.W.; Ziebuhr, J.; Szretter, K.J.; Baker, S.C.; Barchet, W.; Diamond, M.S.; et al. Ribose 2′-O-methylation provides a molecular signature for the distinction of self and non-self mRNA dependent on the RNA sensor Mda5. Nat. Immunol. 2011, 12, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menachery, V.D.; Gralinski, L.E.; Mitchell, H.D.; Dinnon, K.H., III; Leist, S.R.; Yount, B.L., Jr.; Graham, R.L.; McAnarney, E.T.; Stratton, K.G.; Cockrell, A.S.; et al. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Nonstructural Protein 16 Is Necessary for Interferon Resistance and Viral Pathogenesis. MSphere 2017, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menachery, V.D.; Yount, B.L., Jr.; Josset, L.; Gralinski, L.E.; Scobey, T.; Agnihothram, S.; Katze, M.G.; Baric, R.S. Attenuation and restoration of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus mutant lacking 2′-o-methyltransferase activity. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 4251–4264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackbart, M.; Deng, X.; Baker, S.C. Coronavirus endoribonuclease targets viral polyuridine sequences to evade activating host sensors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 8094–8103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindler, E.; Gil-Cruz, C.; Spanier, J.; Li, Y.; Wilhelm, J.; Rabouw, H.H.; Zust, R.; Hwang, M.; V’Kovski, P.; Stalder, H.; et al. Early endonuclease-mediated evasion of RNA sensing ensures efficient coronavirus replication. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; van Geelen, A.; Buckley, A.C.; O’Brien, A.; Pillatzki, A.; Lager, K.M.; Faaberg, K.S.; Baker, S.C. Coronavirus Endoribonuclease Activity in Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Suppresses Type I and Type III Interferon Responses. J. Virol. 2019, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Hackbart, M.; Mettelman, R.C.; O’Brien, A.; Mielech, A.M.; Yi, G.; Kao, C.C.; Baker, S.C. Coronavirus nonstructural protein 15 mediates evasion of dsRNA sensors and limits apoptosis in macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E4251–E4260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minskaia, E.; Hertzig, T.; Gorbalenya, A.E.; Campanacci, V.; Cambillau, C.; Canard, B.; Ziebuhr, J. Discovery of an RNA virus 3’->5’ exoribonuclease that is critically involved in coronavirus RNA synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 5108–5113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorbalenya, A.E.; Enjuanes, L.; Ziebuhr, J.; Snijder, E.J. Nidovirales: Evolving the largest RNA virus genome. Virus Res. 2006, 117, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaton, S.M. Harnessing host-virus evolution in antiviral therapy and immunotherapy. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 2019, 8, e1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Giorgi, E.E.; Marichannegowda, M.H.; Foley, B.; Xiao, C.; Kong, X.P.; Chen, Y.; Gnanakaran, S.; Korber, B.; Gao, F. Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 through recombination and strong purifying selection. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanegan, J.B.; Petterson, R.F.; Ambros, V.; Hewlett, N.J.; Baltimore, D. Covalent linkage of a protein to a defined nucleotide sequence at the 5’-terminus of virion and replicative intermediate RNAs of poliovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1977, 74, 961–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, S.; Guilligay, D.; Pflug, A.; Malet, H.; Berger, I.; Crepin, T.; Hart, D.; Lunardi, T.; Nanao, M.; Ruigrok, R.W.; et al. Structural insight into cap-snatching and RNA synthesis by influenza polymerase. Nature 2014, 516, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilman, M.S.A.; Liu, C.; Fung, A.; Behera, I.; Jordan, P.; Rigaux, P.; Ysebaert, N.; Tcherniuk, S.; Sourimant, J.; Eleouet, J.F.; et al. Structure of the Respiratory Syncytial Virus Polymerase Complex. Cell 2019, 179, 193–204.e114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.; Gao, Y.; Roesler, C.; Rice, S.; D’Cunha, P.; Zhuang, L.; Slack, J.; Domke, M.; Antonova, A.; Romanelli, S.; et al. Cryo-EM structure of the respiratory syncytial virus RNA polymerase. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decroly, E.; Ferron, F.; Lescar, J.; Canard, B. Conventional and unconventional mechanisms for capping viral mRNA. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 10, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, J.L.; Gardner, C.L.; Kimura, T.; White, J.P.; Liu, G.; Trobaugh, D.W.; Huang, C.; Tonelli, M.; Paessler, S.; Takeda, K.; et al. A viral RNA structural element alters host recognition of nonself RNA. Science 2014, 343, 783–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, K.A.; Hertzig, T.; Rozanov, M.; Bayer, S.; Thiel, V.; Gorbalenya, A.E.; Ziebuhr, J. Major genetic marker of nidoviruses encodes a replicative endoribonuclease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 12694–12699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzi, F.; Caffarelli, E.; Laneve, P.; Bozzoni, I.; Brunori, M.; Vallone, B. The structure of the endoribonuclease XendoU: From small nucleolar RNA processing to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 12365–12370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Cai, H.; Pan, J.; Xiang, N.; Tien, P.; Ahola, T.; Guo, D. Functional screen reveals SARS coronavirus nonstructural protein nsp14 as a novel cap N7 methyltransferase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 3484–3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckerle, L.D.; Lu, X.; Sperry, S.M.; Choi, L.; Denison, M.R. High fidelity of murine hepatitis virus replication is decreased in nsp14 exoribonuclease mutants. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 12135–12144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckerle, L.D.; Becker, M.M.; Halpin, R.A.; Li, K.; Venter, E.; Lu, X.; Scherbakova, S.; Graham, R.L.; Baric, R.S.; Stockwell, T.B.; et al. Infidelity of SARS-CoV Nsp14-exonuclease mutant virus replication is revealed by complete genome sequencing. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1000896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauber, C.; Goeman, J.J.; Parquet Mdel, C.; Nga, P.T.; Snijder, E.J.; Morita, K.; Gorbalenya, A.E. The footprint of genome architecture in the largest genome expansion in RNA viruses. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.L.; McMillan, F.M. SAM (dependent) I AM: The S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferase fold. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2002, 12, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snijder, E.J.; Bredenbeek, P.J.; Dobbe, J.C.; Thiel, V.; Ziebuhr, J.; Poon, L.L.; Guan, Y.; Rozanov, M.; Spaan, W.J.; Gorbalenya, A.E. Unique and conserved features of genome and proteome of SARS-coronavirus, an early split-off from the coronavirus group 2 lineage. J. Mol. Biol. 2003, 331, 991–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feder, M.; Pas, J.; Wyrwicz, L.S.; Bujnicki, J.M. Molecular phylogenetics of the RrmJ/fibrillarin superfamily of ribose 2'-O-methyltransferases. Gene 2003, 302, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hager, J.; Staker, B.L.; Bugl, H.; Jakob, U. Active site in RrmJ, a heat shock-induced methyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 41978–41986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouvet, M.; Debarnot, C.; Imbert, I.; Selisko, B.; Snijder, E.J.; Canard, B.; Decroly, E. In vitro reconstitution of SARS-coronavirus mRNA cap methylation. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1000863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Su, C.; Ke, M.; Jin, X.; Xu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, A.; Sun, Y.; Yang, Z.; Tien, P.; et al. Biochemical and structural insights into the mechanisms of SARS coronavirus RNA ribose 2'-O-methylation by nsp16/nsp10 protein complex. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krafcikova, P.; Silhan, J.; Nencka, R.; Boura, E. Structural analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 methyltransferase complex involved in RNA cap creation bound to sinefungin. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decroly, E.; Debarnot, C.; Ferron, F.; Bouvet, M.; Coutard, B.; Imbert, I.; Gluais, L.; Papageorgiou, N.; Sharff, A.; Bricogne, G.; et al. Crystal structure and functional analysis of the SARS-coronavirus RNA cap 2′-O-methyltransferase nsp10/nsp16 complex. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, K.; Guarino, L.; Kao, C.C. The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus Nsp15 protein is an endoribonuclease that prefers manganese as a cofactor. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 12218–12224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, H.; Bhardwaj, K.; Li, Y.; Palaninathan, S.; Sacchettini, J.; Guarino, L.; Leibowitz, J.L.; Kao, C.C. Biochemical and genetic analyses of murine hepatitis virus Nsp15 endoribonuclease. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 13587–13597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillon, M.C.; Frazier, M.N.; Dillard, L.B.; Williams, J.G.; Kocaman, S.; Krahn, J.M.; Perera, L.; Hayne, C.K.; Gordon, J.; Stewart, Z.D.; et al. Cryo-EM structures of the SARS-CoV-2 endoribonuclease Nsp15 reveal insight into nuclease specificity and dynamics. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, K.; Sun, J.; Holzenburg, A.; Guarino, L.A.; Kao, C.C. RNA recognition and cleavage by the SARS coronavirus endoribonuclease. J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 361, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhai, Y.; Sun, F.; Lou, Z.; Su, D.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, R.; Joachimiak, A.; Zhang, X.C.; Bartlam, M.; et al. New antiviral target revealed by the hexameric structure of mouse hepatitis virus nonstructural protein nsp15. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 7909–7917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricagno, S.; Egloff, M.P.; Ulferts, R.; Coutard, B.; Nurizzo, D.; Campanacci, V.; Cambillau, C.; Ziebuhr, J.; Canard, B. Crystal structure and mechanistic determinants of SARS coronavirus nonstructural protein 15 define an endoribonuclease family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 11892–11897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.S.; Saikatendu, K.S.; Subramanian, V.; Neuman, B.W.; Buchmeier, M.J.; Stevens, R.C.; Kuhn, P. Crystal structure of a monomeric form of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus endonuclease nsp15 suggests a role for hexamerization as an allosteric switch. J. Virol 2007, 81, 6700–6708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, T.; Liu, X. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray crystallographic analysis of a nonstructural protein 15 mutant from Human coronavirus 229E. Acta Crystallogr. F Struct. Biol. Commun. 2015, 71, 1156–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, L.; Yan, L.; Ming, Z.; Jia, Z.; Lou, Z.; Rao, Z. Structural and Biochemical Characterization of Endoribonuclease Nsp15 Encoded by Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus. J. Virol. 2018, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Jedrzejczak, R.; Maltseva, N.I.; Wilamowski, M.; Endres, M.; Godzik, A.; Michalska, K.; Joachimiak, A. Crystal structure of Nsp15 endoribonuclease NendoU from SARS-CoV-2. Protein Sci. 2020, 29, 1596–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuchillo, C.M.; Pares, X.; Guasch, A.; Barman, T.; Travers, F.; Nogues, M.V. The role of 2′,3′-cyclic phosphodiesters in the bovine pancreatic ribonuclease A catalysed cleavage of RNA: Intermediates or products? FEBS Lett. 1993, 333, 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, M.; Chen, Y.; Wu, A.; Sun, Y.; Su, C.; Wu, H.; Jin, X.; Tao, J.; Wang, Y.; Ma, X.; et al. Short peptides derived from the interaction domain of SARS coronavirus nonstructural protein nsp10 can suppress the 2'-O-methyltransferase activity of nsp10/nsp16 complex. Virus Res. 2012, 167, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas-Lemus, M.; Minasov, G.; Shuvalova, L.; Inniss, N.L.; Kiryukhina, O.; Brunzelle, J.; Satchell, K.J.F. High-resolution structures of the SARS-CoV-2 2'-O-methyltransferase reveal strategies for structure-based inhibitor design. Sci. Signal. 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assenberg, R.; Ren, J.; Verma, A.; Walter, T.S.; Alderton, D.; Hurrelbrink, R.J.; Fuller, S.D.; Bressanelli, S.; Owens, R.J.; Stuart, D.I.; et al. Crystal structure of the Murray Valley encephalitis virus NS5 methyltransferase domain in complex with cap analogues. J. Gen. Virol. 2007, 88, 2228–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benarroch, D.; Egloff, M.P.; Mulard, L.; Guerreiro, C.; Romette, J.L.; Canard, B. A structural basis for the inhibition of the NS5 dengue virus mRNA 2'-O-methyltransferase domain by ribavirin 5′-triphosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 35638–35643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kentsis, A.; Topisirovic, I.; Culjkovic, B.; Shao, L.; Borden, K.L. Ribavirin suppresses eIF4E-mediated oncogenic transformation by physical mimicry of the 7-methyl guanosine mRNA cap. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 18105–18110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vithani, N.; Ward, M.D.; Zimmerman, M.I.; Novak, B.; Borowsky, J.H.; Singh, S.; Bowman, G.R. SARS-CoV-2 Nsp16 activation mechanism and a cryptic pocket with pan-coronavirus antiviral potential. Biophys. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Liu, L.; Manning, M.; Bonahoom, M.; Lotvola, A.; Yang, Z.; Yang, Z.Q. Structural analysis, virtual screening and molecular simulation to identify potential inhibitors targeting 2'-O-ribose methyltransferase of SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hassab, M.A.; Ibrahim, T.M.; Al-Rashood, S.T.; Alharbi, A.; Eskandrani, R.O.; Eldehna, W.M. In silico identification of novel SARS-COV-2 2'-O-methyltransferase (nsp16) inhibitors: Structure-based virtual screening, molecular dynamics simulation and MM-PBSA approaches. J. Enzyme. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2021, 36, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, S.K.; Maurya, A.K.; Mishra, N.; Siddique, H.R. Virtual screening, ADME/T, and binding free energy analysis of anti-viral, anti-protease, and anti-infectious compounds against NSP10/NSP16 methyltransferase and main protease of SARS CoV-2. J. Recept Signal. Transduct. Res. 2020, 40, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, R.; Zhou, M.; Shek, R.; Wilson, J.W.; Tillery, L.; Craig, J.K.; Salukhe, I.A.; Hickson, S.E.; Kumar, N.; James, R.M.; et al. High-throughput screening of the ReFRAME, Pandemic Box, and COVID Box drug repurposing libraries against SARS-CoV-2 nsp15 endoribonuclease to identify small-molecule inhibitors of viral activity. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, A.; Bibi, N.; Amin, F.; Kamal, M.A. Drug designing against NSP15 of SARS-COV2 via high throughput computational screening and structural dynamics approach. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 892, 173779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Wower, J.; Maltseva, N.; Chang, C.; Jedrzejczak, R.; Wilamowski, M.; Kang, S.; Nicolaescu, V.; Randall, G.; Michalska, K.; et al. Tipiracil binds to uridine site and inhibits Nsp15 endoribonuclease NendoU from SARS-CoV-2. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).