Abstract

Bearings are critical components in industrial machinery, and their failures can lead to equipment downtime and significant safety hazards. Traditional fault diagnosis methods rely on manually crafted features and classical classifiers, often suffering from poor robustness, weak generalization under noisy or small-sample conditions, and limited suitability for lightweight deployment. This study proposes a Lightweight Multi-Scale Multi-Dimensional Self-Attention Transformer (LiMS-MFormer)—an end-to-end lightweight fault diagnosis framework integrating multi-scale feature extraction and multi-dimensional attention. The model integrates lightweight multi-scale convolutional feature extraction, hierarchical feature fusion, and a multi-dimensional self-attention mechanism to balance feature expressiveness with computational efficiency. Specifically, the front end employs Ghost convolution and enhanced residual structures for efficient multi-scale feature extraction. The middle layers perform cross-scale concatenation and fusion to enrich contextual representations. The back end introduces a lightweight temporal-channel-spatial attention module for global modeling and focuses on key patterns. Experiments on the Paderborn University (PU) dataset and the University of Ottawa bearing vibration dataset (Ottawa dataset) show that LiMS-MFormer achieves an accuracy of 96.68% on the small-sample PU dataset while maintaining minimal parameters (0.07 M) and low computational cost (13.55 M FLOPs). Moreover, under complex noisy conditions, the proposed model demonstrates strong fault diagnosis capability. On the University of Ottawa dataset, LiMS-MFormer consistently outperforms several state-of-the-art lightweight models, exhibiting superior accuracy, robustness, and generalization in challenging diagnostic tasks.

1. Introduction

Bearings are essential in industrial machinery, reducing friction and ensuring smooth operation, with failures leading to significant downtime, costly repairs, and safety risks. Therefore, effective fault detection and maintenance are crucial for maintaining the reliability of rotating machinery and machine tools, which are central to modern industrial operations. Early detection of faults under challenging conditions, such as high noise levels and limited data availability, is crucial to minimizing downtime and maintaining optimal system performance [1].

Traditional fault diagnosis relies heavily on handcrafted features extracted from vibration signals [2]. As equipment complexity increases and early fault signatures become difficult to detect, feature-engineering methods can no longer meet modern requirements for real-time, robust, and accurate diagnosis, highlighting the need for more adaptive and automated approaches [3]. Consequently, researchers have shifted towards data-driven intelligent diagnosis methods, particularly those based on machine learning and deep learning. These approaches can automatically extract discriminative features from raw signals and enable end-to-end fault classification. Compared with traditional methods, data-driven models offer superior adaptability and diagnostic performance in multi-condition, high-noise, and non-stationary environments, making them the mainstream direction in recent fault diagnosis research [4]. Representative data-driven studies have explored time–frequency feature integration, sparse classification, and GAN-enhanced feature learning to improve fault diagnosis performance under challenging conditions [5,6].

With the advancement of deep learning, fault diagnosis models have evolved from shallow to deeper and more expressive architectures. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have been widely adopted due to their ability to extract local features from raw vibration signals [7]. For instance, Jin et al. [8] developed a multiscale CNN with residual preprocessing that improves robustness under strong noise interference. Other studies have similarly enhanced CNN-based diagnosis by incorporating multiscale convolutions and residual connections to improve feature representation and stability under non-stationary conditions [9]. However, the inherently local receptive fields of CNNs restrict their ability to capture long-range dependencies and global contextual information, particularly in nonlinear or non-stationary vibration signals. In addition, CNN-based models often exhibit limited robustness and generalization under harsh or variable operating conditions, which restricts their applicability in real-world deployments [10].

Motivated by these challenges, researchers have increasingly explored alternative deep neural network architectures such as Recurrent Neural Networks [11], Long Short-Term Memory networks [12], Bidirectional LSTM [13], Generative Adversarial Networks [14], and Transformer-based models [15]. These models are capable of capturing temporal dependencies and emphasizing key signal features, thereby improving diagnostic accuracy and robustness. For example, Liu et al. [16] proposed an FSWT–GAN–Capsule Network framework that enhances feature extraction and alleviates data imbalance in bearing fault diagnosis. Jin et al. [17] developed a one-dimensional Transformer model that effectively addresses the long-dependency limitations of CNN- and RNN-based approaches without requiring complex preprocessing. Despite these advances, single-architecture models often face performance bottlenecks in robustness and generalization [18]. To overcome these limitations, researchers have explored hybrid deep learning models that combine multiple structures to leverage their complementary strengths. For example, Yang et al. [19] integrated Conditional Generative Adversarial Networks with a two-dimensional CNN to tackle fault diagnosis under small-sample conditions, demonstrating improvements in both data augmentation and classification performance. Other hybrid architectures, such as CNN–BiLSTM [20] and CNN–Transformer [21] fusion models, have similarly demonstrated enhanced diagnostic performance and robustness in complex or fluctuating environments.

The fusion of multiple deep learning architectures has significantly improved the accuracy and robustness of fault diagnosis tasks [22]. Although some studies achieve lightweight design by reducing feature dimensions, this may cause the loss of fine-grained diagnostic information. Therefore, designing lightweight convolutional and attention modules that preserve discriminative features while reducing computational cost remains essential. To address this need, numerous lightweight networks have been proposed. Howard et al. [23] introduced depthwise separable convolutions to substantially reduce parameters and FLOPs in mobile applications. Other lightweight architectures, such as ShuffleNet [24] and EfficientNet [25] further optimize computational efficiency through channel shuffle operations and compound scaling strategies. These advances highlight the growing potential of lightweight models in fault diagnosis, particularly for real-time monitoring and edge-computing environments. Recent studies have begun incorporating lightweight designs into bearing fault diagnosis. For example, Wang et al. [26] proposed the C-ECAFormer, which integrates inverted residual blocks and efficient attention mechanisms to improve performance under small-sample and noisy conditions. Jiang et al. [27] developed a 1D-Inception-SE model that combines multiscale convolutions and attention mechanisms to reduce parameter count while maintaining high diagnostic accuracy.

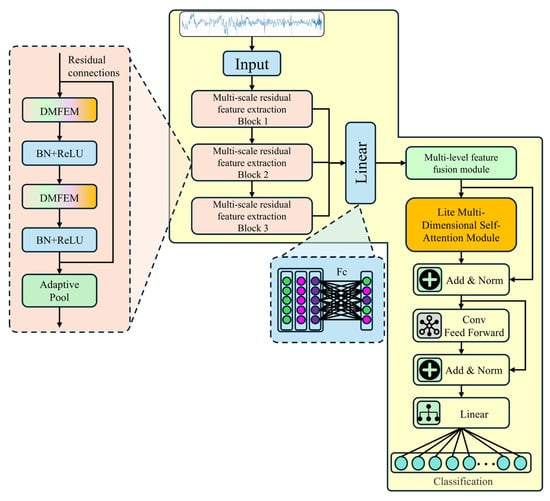

Inspired by the aforementioned studies, this paper proposes a lightweight end-to-end fault diagnosis framework—Lightweight Multi-Scale Multi-Dimensional Self-Attention Transformer (LiMS-MFormer)—to address the challenges of intelligent fault diagnosis under complex conditions such as limited sample availability, strong noise interference. First, the front end of LiMS-MFormer integrates a Deformable Multi-Scale Feature Extraction Module (DMFEM), which combines lightweight convolution, deformable kernels, and multi-scale dilated receptive fields within a unified residual structure. This design enables adaptive feature alignment and efficient extraction of fault-related patterns while maintaining extremely low computational cost. Second, LiMS-MFormer incorporates a hierarchical cross-layer fusion mechanism, which progressively aggregates features from different depths and receptive fields. Unlike traditional single-stage concatenation, this multi-level fusion enriches contextual representation and enhances the robustness of temporal features, particularly under small-sample conditions. Third, the back end introduces a Multi-Dimensional Self-Attention Module (MDSAM) designed specifically for one-dimensional vibration signals. By jointly modeling temporal, channel, and spatial relationships within a lightweight attention formulation, MDSAM significantly improves global dependency modeling while avoiding the computational burden of conventional Transformer attention. Together, these innovations form an efficient and compact architecture that substantially enhances adaptability to non-stationary signals, improves noise resilience, and achieves high diagnostic accuracy with minimal parameters and FLOPs.

The main contributions and novelties of this study can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

- Lightweight Multi-Scale Feature Extraction Module. A novel feature extraction block, termed DMFEM, is proposed by integrating Ghost convolution with an improved multi-scale residual structure. Rather than merely stacking dilated kernels, DMFEM leverages lightweight feature generation and cross-scale residual coupling to preserve fine-grained fault patterns while suppressing redundancy. This targeted design enhances discriminability under small-sample and noisy conditions, achieving lightweight efficiency without sacrificing representational depth.

- (2)

- Multi-Dimensional Self-Attention Mechanism. A lightweight attention module that integrates temporal, channel, and spatial cues within a unified attention formulation is introduced to replace conventional multi-head self-attention. By jointly modeling these dimensions rather than treating them separately, MDSAM enhances global feature interaction with minimal computational cost, improving robustness under small-sample and noisy vibration conditions.

- (3)

- Superior Lightweight Performance and Small-Sample Diagnostic Capability. With its compact architecture and efficient inference design, LiMS-MFormer consistently delivers higher diagnostic accuracy than existing lightweight baselines on both the PU dataset and the University of Ottawa dataset. The model maintains strong robustness and generalization even under limited training samples and severe noise conditions, demonstrating its practical suitability for real-world, resource-constrained industrial scenarios.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the theoretical foundations. Section 3 describes the architecture and module design of LiMS-MFormer. Section 4 presents and analyzes the experimental results. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the study and outlines future research directions.

2. Relevant Theoretical Foundations

2.1. Multi-Scale Convolutional Neural Network

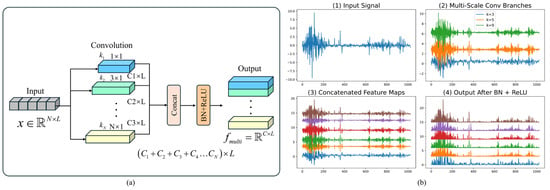

Multiscale Convolutional Neural Networks are widely applied in mechanical fault diagnosis tasks by introducing convolutional kernels of varying sizes [28], enabling the capture of feature representations across different temporal or spatial scales. This approach proves particularly effective for processing vibration signals characterized by multiple frequency components and non-stationary behavior. In typical MSCNN architectures, the input signal is simultaneously processed through multiple convolutional branches, each employing kernels of different sizes to extract features at diverse scales.

Here, denotes the one-dimensional convolution operation with a kernel size of applied on the ith branch, BN represents the batch normalization layer, and ReLU is the nonlinear activation function.

Finally, the multiscale features are concatenated along the channel dimension to form the aggregated representation:

The fused multiscale feature representation integrates information extracted under different receptive fields, thereby enhancing the model’s discriminative capability across various fault types. Multiscale CNNs demonstrate strong generalization performance under small-sample scenarios, high noise levels, and variable operating conditions, making them particularly suitable for analyzing complex signals in real-world industrial environments. The overall architecture is illustrated in Figure 1a, and Figure 1b provides an example of the input vibration signal and the corresponding feature maps generated by the multiscale convolution module.

Figure 1.

(a) Multi-Scale Convolution Module. (b) Numerical example of the input signal and intermediate feature maps.

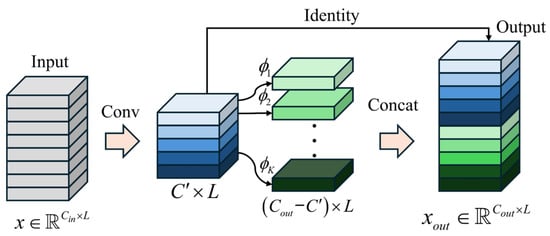

2.2. Ghost Convolution for 1D Signal Modeling

Ghost convolution is first introduced by Han et al. [29] in the GhostNet architecture to reduce the computational cost associated with redundant feature maps. The core idea is to generate equivalent or similar feature representations using fewer standard convolution operations. Ghost convolution adopts a two-stage design: a small portion of intrinsic features, referred to as “primary features,” is obtained through conventional convolutions, while the remaining “ghost” features are generated using inexpensive linear operations, such as depthwise separable convolutions. This approach effectively mimics the output of standard convolutions while significantly improving computational efficiency.

In one-dimensional signal processing tasks, GhostConv1D serves as a natural extension of the original Ghost convolution and is particularly well-suited for modeling time-series data such as vibration signals. The computational process is defined as follows:

Let the input signal be , the total number of output channels be , and the compression ratio be . The overall computation process of GhostConv1D can be summarized as follows:

where denotes the number of intrinsic feature channels generated by standard convolution, DWConv1D denotes the depthwise (channel-wise) one-dimensional convolution, and Concat represents concatenation along the channel dimension. The detailed structure of GhostConv1D is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The Ghost module.

3. 3 Proposed Method

Building on the theoretical analysis presented in the previous chapter and considering the challenges of limited fault samples, strong noise interference, and the need for lightweight deployment in industrial scenarios, this chapter provides a detailed introduction to the proposed lightweight fault diagnosis model, LiMS-MFormer, along with its key component modules. Designed for modeling one-dimensional vibration signals, the model integrates multi-scale convolutional structures with multi-dimensional self-attention mechanisms to enhance feature representation and diagnostic performance in real-world industrial scenarios involving small samples and complex noise. Centered on lightweight design principles, the model first employs dilated convolutions combined with Ghost convolutions to construct a multi-scale feature extraction module (DMFEM), improving sensitivity to fault features across different frequency bands. It then incorporates a compressed multi-dimensional self-attention module (MDSAM) to focus on critical responses across temporal, channel, and spatial dimensions. Finally, a streamlined Transformer encoder structure is used to capture temporal dependencies and perform fault classification. With its compact architecture, low computational cost, and high diagnostic accuracy, the proposed model is well-suited for deployment on resource-constrained devices. The following sections describe the design and implementation details of each module.

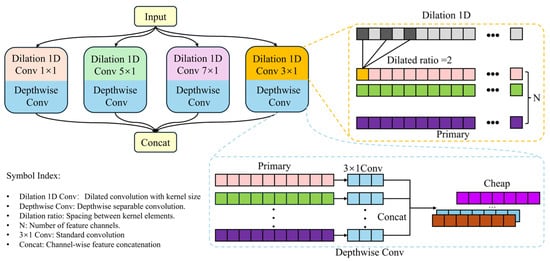

3.1. Lightweight Dilated Multi-Scale Feature Extraction Module (DMFEM)

In practical industrial fault diagnosis tasks, raw signals often contain information at multiple scales simultaneously, including high-frequency components resulting from short-term impacts and low-frequency patterns associated with long-term trends. Traditional CNNs, due to their fixed kernel sizes and static receptive fields, typically extract features at a single scale, thereby limiting their ability to effectively capture multi-scale information. A common strategy for addressing this limitation involves using multi-branch structures with parallel convolutions of varying kernel sizes. While this improves feature representation capability, it also substantially increases the number of parameters and computational cost, limiting its applicability in lightweight industrial deployment scenarios.

To address this issue, this paper proposes a lightweight DMFEM. The module adopts a four-branch structure and replaces conventional kernels of different sizes with convolutions that use varying dilation rates. This design effectively expands the receptive field to capture multi-scale patterns while controlling parameter growth. Although dilated convolutions increase receptive field size, standard convolutions still introduce redundancy in parameters and computational cost. To further reduce complexity, the module incorporates Ghost convolutions, which combine the efficiency of multi-branch architectures with a streamlined feature generation process. As shown in Figure 3, Ghost convolution divides the output feature maps into two parts, with primary features generated through standard convolution and redundant features produced by lightweight depthwise convolutions. These two parts are then concatenated to form the final output feature map. This design maintains expressive power while significantly reducing the number of parameters and computational cost. Based on the above operations, the formulas for calculating the number of parameters and FLOPs for each branch in this lightweight module are as follows:

where denotes the number of input channels, denotes the number of output channels, is the kernel size of the primary convolution, is the kernel size of the cheap operation, is the compression ratio, and is the temporal length of the input sequence.

Figure 3.

Structure diagram of DMFEM.

For example, in a single branch with both the input and output channels set to 128 and a kernel size of 3, the number of parameters in a standard convolution is 128 × 128 × 3 = 49,152, and the corresponding FLOPs is 49,152 × L. In contrast, using Ghost convolution with a compression ratio r = 2, the primary convolution generates 64 intrinsic feature maps, resulting in 128 × 64 × 3 = 24,576 parameters. The subsequent depthwise convolution generates 64 redundant feature maps using 64 × 3 = 192 parameters. Therefore, the total parameter count is only 24,768, which is approximately half of that in the standard convolution. Similarly, the computational cost is reduced to 24,768 × L, effectively achieving a lightweight design.

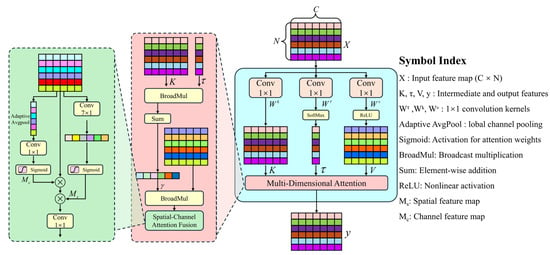

3.2. Lite Multi-Dimensional Self-Attention Module (MDSAM)

Self-attention, originally proposed by Vaswani et al. in the Transformer architecture [30], serves as the foundation of the multi-head self-attention mechanism and has been widely applied in tasks such as image recognition, sequence modeling, and fault diagnosis. Traditional multi-head attention mechanisms capture global dependencies across different subspaces through multiple parallel self-attention heads, thus exhibiting strong feature representation capabilities. However, when applied to long one-dimensional vibration sequences, the spatial-temporal complexity and redundant linear transformations associated with multiple heads lead to significant parameter overhead, making them unsuitable for small-sample scenarios or deployment in resource-constrained environments.

To address this limitation, a lightweight multi-dimensional self-attention module, termed MDSAM, is proposed. While preserving the ability to model global dependencies, this module effectively reduces the parameter count and computational cost through structural compression and the fusion of broadcasted attention across different dimensions, without compromising feature extraction performance. The Lite-MDSAM comprises the following three components, and its final structure is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Structure diagram of MDSAM.

- Compressed Temporal Attention Mechanism

Given the input feature map , where denotes the number of channels. First, 1 × 1 convolutions are applied to generate the Query, Key, and Value representations:

The attention weights along the temporal dimension are then computed and broadcast-multiplied with the key matrix, followed by a weighted summation to form the context vector:

The context vector is element-wise multiplied with the activated value representation to enhance feature representation. The compressed temporal attention weights are broadcast-multiplied with the key vectors , and a weighted summation is performed along the temporal dimension to obtain the context vector:

Subsequently, the context vector is element-wise multiplied with the activated value vector:

- 2.

- Channel Attention Mechanism

To model the importance of each channel, global average pooling and channel-wise convolution are introduced. After applying global average pooling to the original input:

The channel attention weights are obtained through a 1 × 1 convolution followed by a Sigmoid activation function:

- 3.

- Spatial Attention Mechanism

To enhance the model’s sensitivity to critical time points, a one-dimensional convolution is introduced to construct the spatial attention module:

The convolution kernel size is set to 7, which provides a larger temporal receptive field and highlights important regions within the sequence.

The final output is obtained by fusing the results from the three attention mechanisms:

where denotes the output projection convolution, and represents element-wise multiplication with broadcasting.

Based on the above formulations, the parameters and FLOPs of this module can be computed as follows:

Compared with the standard Multi-Head Self-Attention (MHSA) mechanism, the proposed module eliminates multiple attention heads and retains only a single set of compressed attention weights (i.e., temporal attention τ) combined with channel–spatial modulation. Although it adopts a single-head structure, the integration of multi-dimensional attention across temporal, channel, and spatial domains enables equivalent or even more expressive feature modeling. In terms of parameter count and computational complexity, the proposed design is significantly more compact, making it well-suited for deployment on resource-constrained devices.

3.3. Proposed Model

The overall architecture of LiMS-MFormer consists of three multi-scale residual feature extraction modules, a hierarchical feature fusion module, and a lightweight Transformer encoder module, as illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Architecture of LiMS-MFormer.

First, the raw vibration signal is fed into the model and sequentially passes through three multi-scale residual feature extraction modules. Preliminary exploratory experiments confirmed that, under the lightweight constraints of this study, deeper or larger multi-scale configurations did not yield noticeable performance gains, thereby supporting the adoption of the three-stage design. Each module consists of two stacked improved DMFEM structures, which incorporate GhostConv to enable multi-scale temporal feature modeling with low computational complexity. Convolutional kernels with different receptive fields are used to capture both fine-grained local features and long-term dependencies, and the resulting outputs are fused through concatenation. Each residual block includes adaptive average pooling and residual connections while maintaining consistent dimensionality. This design is inspired by the ResNet architecture proposed by He et al. [31], aiming to alleviate the vanishing gradient problem, enhance feature flow, and compress sequence length, thereby contributing to output stability. As a result, three intermediate feature representations at different scales are generated.

Next, the three hierarchical feature representations are compressed into vectors through average pooling, concatenated, and passed into a fusion module composed of two fully connected layers to enable cross-level feature integration. The fused feature is then expanded into a fixed-length sequence representation, which serves as the input to the subsequent Transformer module.

After fusion, the expanded sequence is further enhanced using a lightweight Transformer encoder. Unlike the standard Multi-Head Self-Attention (MHSA) mechanism, the proposed module removes multiple attention heads and retains only a single set of compressed attention weights (i.e., temporal attention τ) integrated with channel–spatial modulation. Although adopting a single-head structure, the incorporation of multi-dimensional attention across temporal, channel, and spatial domains enables equally or even more expressive feature modeling. Regarding parameter count and computational complexity, the proposed design is significantly more compact, making it highly suitable for deployment on resource-constrained devices.

Finally, the output sequence representation is converted into a feature vector through average pooling along the temporal dimension and then fed into a two-layer fully connected classifier to predict fault categories. In summary, the LiMS-MFormer model achieves efficient feature representation and global dependency modeling through lightweight multi-scale feature extraction, hierarchical fusion, and multi-dimensional self-attention mechanisms. It effectively balances diagnostic performance and computational cost, making it well-suited for intelligent fault diagnosis tasks under small-sample conditions. The detailed parameter configurations of the model are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Configuration Details of the LiMS-MFormer Model.

4. Experimental Validation and Discussion

To validate the effectiveness and lightweight performance of the proposed fault diagnosis method, experiments are conducted on bearing fault samples from both the PU dataset and the uOttawa dataset, which are widely used benchmark datasets in the fault-diagnosis community and provide standardized operating conditions that enable fair comparison and reproducibility across studies. All training and testing procedures are performed using the PyTorch 2.2.2 framework within the PyCharm 2023.3.4 development environment (JetBrains, Prague, Czech Republic). The experimental platform is configured with an Intel® Core™ i5-9300H @ 2.40 GHz processor (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA), an NVIDIA RTX 1660 Ti GPU (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and 6 GB of memory. All models involved in the experiments are trained under consistent hyperparameter settings and data preprocessing procedures. Specifically, the initial learning rate is set to 0.0003, the batch size to 32, and the maximum number of training epochs to 100. During training, a performance-based adaptive learning rate decay mechanism is employed. If the accuracy improvement falls below a predefined threshold of 0.003 or the loss reduction becomes negligible for three consecutive epochs, the learning rate is automatically reduced by a factor of 0.8 to avoid convergence to local minimum or training instability. The minimum allowable learning rate is set to 1 × 10−6 to ensure that updates do not become excessively small. The specific parameters are shown in Table 2. This adaptive strategy helps maintain stable convergence and improves overall training efficiency. Finally, the model achieving the best performance on the validation set in terms of loss convergence and accuracy improvement is selected for final evaluation during testing.

Table 2.

Optimization parameters of the model.

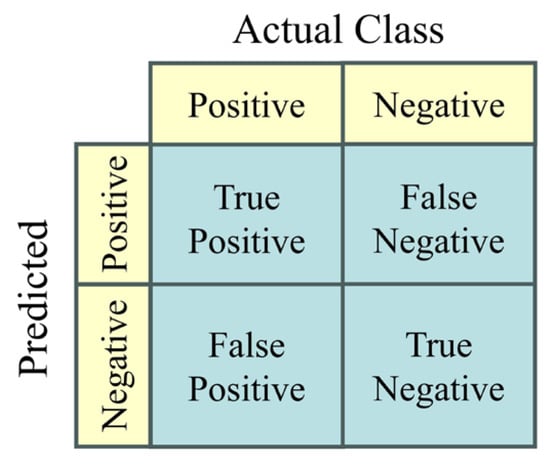

For model evaluation, accuracy derived from the confusion matrix is adopted as the primary performance metric. The accuracy is defined as follows:

Here, True Positive (TP) refers to the number of fault samples correctly identified as faulty, while True Negative (TN) denotes the number of normal samples correctly identified as normal. False Positive (FP) indicates the number of normal samples incorrectly classified as faulty, and False Negative (FN) represents the number of fault samples misclassified as normal. These values are derived from a 2 × 2 confusion matrix, as illustrated in Figure 6, and various evaluation metrics based on this matrix are used to comprehensively assess the model’s performance.

Figure 6.

Confusion Matrix.

4.1. Experiments on the PU Dataset

4.1.1. Description of the PU Dataset

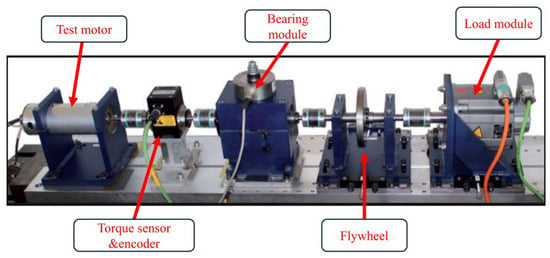

The PU dataset is a publicly available benchmark from Paderborn University, providing rolling-bearing condition monitoring data under various health and fault states, together with detailed descriptions of the corresponding damage mechanisms. The data were collected using a dedicated bearing test platform consisting of a drive motor, torque sensor shaft, bearing housing, and load motor, as shown in Figure 7 [32]. A vibration accelerometer is mounted on the outer radial surface of the bearing housing to capture the radial vibration response during operation. The tested components are SKF 6203-2Z deep-groove ball bearings made of bearing steel, which include both artificially induced faults and naturally developed degradation. Artificial faults are introduced using methods such as electrical discharge machining, manual carving, and drilling, while natural faults are generated through continuous operation on the accelerated life test bench.

Figure 7.

Testbed for PU Data.

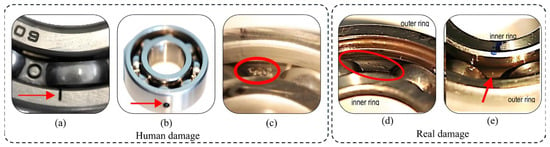

During the natural degradation process, bearings operate for extended periods under high radial load and insufficient lubrication, leading to progressive contact fatigue, pitting, spalling, and abrasive wear caused by lubricant deterioration and thermal–mechanical stress. These mechanisms replicate realistic in-service failure modes occurring in rolling bearings. Representative examples of typical fault conditions are presented in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Different types of bearing damage. (a) Electrical discharge machining. (b) Electric engraving tool. (c) Drilling. (d) Dent on the outer raceway (IR). (e) Pitting on the inner raceway.

Vibration signals are collected using a PCB 336C04 acceleration sensor, low-pass filtered at 30 kHz, and recorded at a sampling rate of 64 kHz. Current signals are acquired using an LEM CKSR 15-NP sensor, also sampled at 64 kHz with a bandwidth of 25 kHz. The dataset comprises bearing samples from four operating conditions, including 12 samples with artificially induced faults, 14 with naturally developed faults, and 6 healthy samples. The specific parameters for each operating condition are summarized in Table 3. Compared with artificially generated fault data, real damage samples collected from the test bench are more suitable for evaluating fault diagnosis performance in this study. The detailed fault types and corresponding parameters are summarized in Table 4, which includes 12 naturally developed fault samples and one healthy bearing sample.

Table 3.

Experimental Conditions and Parameters.

Table 4.

PU dataset with real bearing damages.

4.1.2. Evaluation of Model Performance Under Small-Sample Conditions

In this experiment, the first operating condition from the dataset is selected as the subject of study, with operating parameters set to a rotational speed of 900 rpm, a load of 0.7 N, and a radial force of 1000 N. To guarantee input data uniformity, the sliding window method is utilized to segment one-dimensional time series vibration signals into fixed-length samples of 1024 points. This window size adheres to the conventional practice in vibration-based bearing fault diagnosis, enabling the effective extraction of fault features from the time-domain signal for subsequent diagnostic model training. Based on this preprocessing strategy, three small-sample datasets of different sizes are constructed and denoted as Datasets A, B, and C. Following recent studies that employ comparable sampling scales in small-sample bearing diagnosis, we select 100, 200, and 300 samples per fault category, respectively, to form the three datasets [33]. Consequently, the total number of samples for the 13-class classification task is 1300, 2600, and 3900 for Datasets A, B, and C, respectively.

Each dataset is split into training, validation, and testing sets in a ratio of 60%, 20%, and 20%, respectively, for model training, hyperparameter tuning via cross-validation, and final performance evaluation [34]. To enhance the scientific rigor and robustness of the results, all data partitioning is performed using a randomized splitting strategy, minimizing the impact of sample distribution bias on model evaluation. This section presents the training accuracy and loss convergence curves of the proposed model, along with validation performance metrics. Furthermore, the confusion matrix and t-SNE visualization obtained during the final testing phase are provided to comprehensively assess the model’s classification capability and feature separation effectiveness.

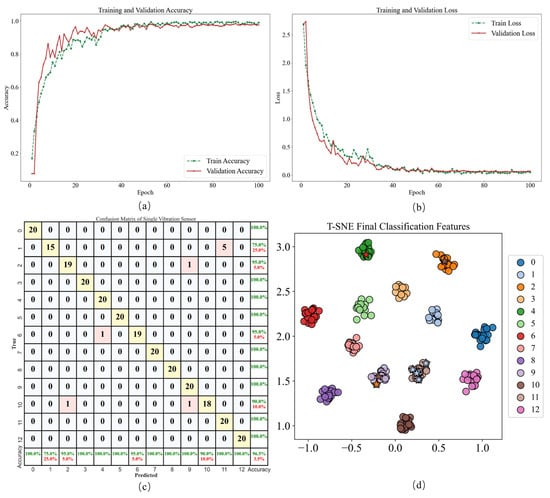

As summarized in Table 5, LiMS-MFormer achieves accuracies of 96.68%, 98.98%, and 99.61% on Datasets A, B, and C, respectively. The steady improvement across growing sample sizes confirms the model’s ability to generalize effectively even when trained with extremely limited data. In addition to accuracy, the corresponding F1-score and recall values also increase consistently with dataset size, further demonstrating the robustness and reliability of the proposed model. For Dataset A, the training curves shown in Figure 9 converge smoothly within approximately 60 epochs, indicating stable optimization and the absence of overfitting—an essential property for small-sample learning. Diagnostic visualization further illustrates the behavior of the model. The t-SNE projections show clear class separability for most categories, while the few observed misclassifications (e.g., among KA15, KA22, KB23, KI14, KI17, and KI18) reflect intrinsic similarities between certain bearing fault types rather than training instability. These misclassifications are highlighted with star markers to indicate their occurrence. These misclassification patterns reveal that certain fault categories are difficult to distinguish due to similarities in their learned feature distributions.

Table 5.

PU Dataset Split for Small-Sample Experiments.

Figure 9.

Model diagnosis visualization: (a) Accuracy, (b) Loss, (c) Confusion Matrix, (d) t-SNE.

4.1.3. Visualization of the Model Diagnosis Process

In this section, the t-SNE algorithm is employed to visualize the features extracted by the model at various stages and to analyze their distribution in a low-dimensional space. The experiment is conducted on Dataset A, as described in the previous section, which contains vibration signal samples from multiple fault categories. The high-dimensional features are reduced to two dimensions using t-SNE, enabling the observation of class separability and distribution patterns. Figure 10 illustrates how effectively the model separates different fault types in the feature space.

Figure 10.

T-SNE visualizations of the model at different stages.

By comparing features from different stages—such as raw input features, outputs of convolutional layers, and fused features—we can intuitively observe the evolution of feature representations. The experimental results show that after convolution and fusion operations, the features become increasingly separable in low-dimensional space, indicating that the model gradually learns more meaningful and discriminative representations during training. Notably, at the feature fusion stage, the t-SNE visualization shows clear inter-class separation, confirming that the model effectively distinguishes between different fault categories.

4.1.4. Evaluation and Comparison of Lightweight Model Performance Under Small-Sample Conditions

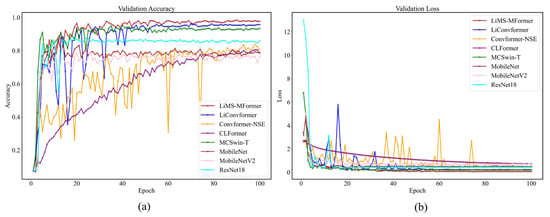

In this section, the proposed model is rigorously evaluated and compared against several state-of-the-art lightweight approaches to demonstrate its effectiveness and computational efficiency in fault diagnosis tasks. The comparison comprehensively considers computational efficiency, inference speed, storage requirements, and diagnostic accuracy, aiming to demonstrate the superior performance of the proposed LiMS-MFormer model under small-sample conditions. The evaluation includes four recently developed end-to-end CNN-Transformer-based diagnostic models: LiConvFormer [35], Convformer-NSE [36], CLFormer [37], and MCSwin-T [38]. In addition, three widely used lightweight CNN models are included for comparison: MobileNet [23], MobileNet-V2 [39], and ResNet18 [31]. Each model is trained for 100 epochs with a batch size of 32. All experiments are independently repeated five times, and the average testing accuracy is reported as the final result. Furthermore, one representative training session from Dataset A is selected to visualize and compare the validation accuracy and loss curves across different models, as shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Comparison of different mold types. (a) accuracy. (b) loss.

As shown in Figure 11a, the proposed LiMS-MFormer model demonstrates a faster convergence rate during the early stages of training and maintains consistently high and stable validation accuracy throughout the entire training process, outperforming the other models. Figure 11b presents the validation loss trends of all compared models. The loss of LiMS-MFormer decreases rapidly and remains at a low level, indicating its strong capability to avoid overfitting and to enhance generalization. In contrast, Convformer-NSE and LiConvFormer exhibit larger fluctuations in validation loss, while ResNet18 shows relatively high loss values during the initial training epochs, resulting in overall weaker performance. Taken together, LiMS-MFormer achieves superior performance in both accuracy and loss, confirming its advantage in small-sample lightweight fault diagnosis tasks.

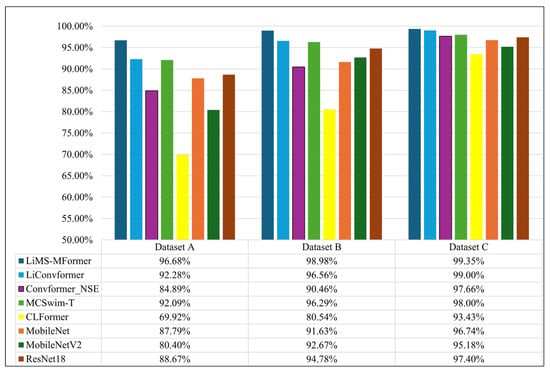

To further assess performance differences, Table 6 presents the accuracy and model complexity of all compared methods on Dataset A. Accuracy evaluates the classification effectiveness, while Params reflects model size. FLOPs represent inference computation, and Training/Test Memory indicates GPU consumption during backpropagation and inference, respectively. LiMS-MFormer achieves an accuracy of 96.68% with only 0.07 M parameters and 13.55 MFLOPs, demonstrating a favorable balance between accuracy and compactness. Although CLFormer has lower computation and parameter count, its accuracy drops to 69.92%. Convformer-NSE attains competitive FLOPs but only 84.89% accuracy. Models such as MCSwin-T and MobileNet obtain higher accuracies of 92.09% and 87.79%, but at the cost of significantly increased parameter counts, FLOPs, and memory usage. These results demonstrate that LiMS-MFormer achieves a superior trade-off between diagnostic accuracy, computational efficiency, and memory footprint, making it highly suitable for deployment in resource-limited real-world applications.

Table 6.

Diagnostic accuracy and model complexity of various methods.

As shown in Figure 12, the diagnostic accuracy of all compared models under different training sample sizes is presented. As the number of training samples increases, the performance of each model gradually improves and eventually stabilizes, confirming the strong dependence of deep learning methods on data volume in fault diagnosis tasks. The proposed LiMS-MFormer consistently achieves the highest accuracy across all sample sizes, reaching 96.68%, 98.98%, and 99.35% on Datasets A, B, and C, respectively, which demonstrates excellent robustness and generalization in small-sample scenarios. Traditional lightweight models such as MobileNet and MobileNetV2 exhibit significantly reduced performance when trained with limited samples, achieving accuracies of only 87.79% and 80.40% on Dataset A. Although their accuracy improves when more data becomes available, they still fall short of the performance achieved by LiMS-MFormer. Deep or hybrid architectures such as ResNet18 and MCSwin-T deliver competitive accuracy when trained with larger datasets, but their performance declines noticeably under small-sample conditions, creating a clear gap compared to the proposed model. Transformer-based models such as CLFormer and Convformer-NSE also struggle in data-constrained settings, with CLFormer reaching only 69.92% accuracy on Dataset A.

Figure 12.

Comparison of Diagnostic Results of Different Models Under Different Sample Sizes.

These results collectively indicate that LiMS-MFormer maintains stable, high-level diagnostic performance across varying data scales and demonstrates clear advantages in highly data-limited environments.

4.2. Performance Comparison on the uOttawa Dataset

4.2.1. Description of the uOttawa Dataset

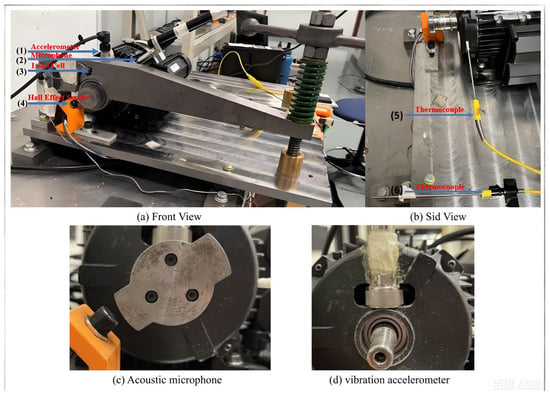

To ensure dataset diversity and enhance model applicability, this study incorporates experimental data from the vibration-acoustic fault diagnosis platform at the University of Ottawa [40]. This platform is specifically designed for rolling bearing fault detection and provides high-quality, synchronously collected vibration and acoustic signals. The physical structure of the test platform is illustrated in Figure 13. The University of Ottawa dataset includes vibration measurements from two bearing models, NSK 6203ZZ and FAFNIR 203KD. In this study, only the FAFNIR 203KD deep-groove ball bearing made of bearing steel is used, as all monitored degradation processes and fault types—healthy, inner-race, outer-race, ball, and cage faults—are generated on this bearing model. During the experiments, the system operates under a constant load of 400 N and a fixed rotational speed of 1750 RPM, with a data acquisition rate of 42 kHz, resulting in a total of 420,000 samples. The acquisition setup includes an accelerometer (model: PCB 623C01) mounted at the drive-end bearing of the motor to capture vibration data, and a microphone (model: PCB 130F20) positioned approximately 2 cm from the bearing to capture acoustic data. Although the dataset contains both vibration and acoustic signals, only the vibration data is used in this study for analysis and modeling, as it is more relevant to mechanical fault characteristics.

Figure 13.

Physical structure of the UORED-VAFCLS test rig. (a) Front View. (b) Sid View. (c) Acoustic microphone. (d) vibration accelerometer.

The dataset covers various operating conditions of bearings, including three health states—normal, developing fault, and severe fault—and four common fault types: inner race damage, outer race damage, rolling element defect, and cage fault, resulting in a total of nine diagnostic categories. In this study, a representative subset of samples is selected from these health states and typical fault stages to serve as the basis for the classification task. According to the dataset documentation, bearing degradation is naturally developed during testing. The drive-end bearing seals were removed and the bearings were fully degraded to accelerate deterioration, as described in the original experimental setup. Detailed descriptions of the fault types and corresponding parameters are provided in Table 7.

Table 7.

University of Ottawa Dataset Fault Classification.

4.2.2. Analysis of Diagnostic Robustness in Noisy Low-Sample Scenarios

Considering that bearing operation in real industrial environments is often accompanied by noise interference, this section aims to evaluate the diagnostic capability of the proposed model under small-sample and noisy conditions. To this end, the same Dataset A from the previous section is used, and Gaussian white noise with varying signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs) is added to the entire dataset before the train–test split, ensuring that both the training and test samples contain noise and simulating more realistic operating environments. The method for computing the signal-to-noise ratio used for noise addition is defined as follows:

Here, and represent the power of the signal and the noise, respectively. denotes the ratio of signal power to noise power in decibels (dB).

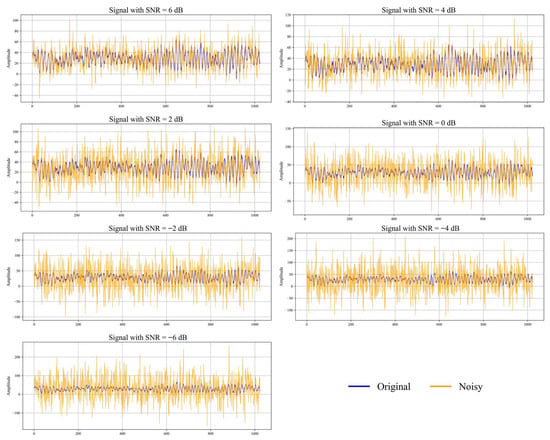

Specifically, seven noise-contaminated datasets are constructed with signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs) ranging from −6 dB to 6 dB. Taking fault type I_1_2 (inner race damage) as an example, signals with different SNR levels are visualized, as shown in Figure 14. In the figure, the blue curve represents the original vibration signal without noise, while the orange curve shows the signal after adding Gaussian white noise.

Figure 14.

Visualization of signals under different SNRs.

It can be observed that as the SNR decreases, the degree of interference from noise on the original signal becomes increasingly significant. The waveform becomes progressively obscured by noise, and at SNR levels of −4 dB and −6 dB, the fault-related patterns are almost indistinguishable from the noise. This trend clearly illustrates the impact of varying noise intensities on the recognizability of fault signatures in the vibration signal.

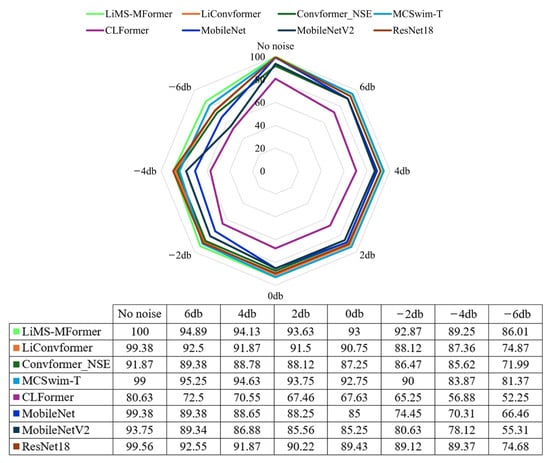

Figure 15 presents a radar chart illustrating the diagnostic performance of different models under various noise levels. Overall, the LiMS-MFormer demonstrates consistently strong performance across all SNR levels, maintaining a high accuracy of 86.01% even under severe noise conditions at −6 dB, indicating excellent noise robustness.

Figure 15.

Radar chart of the accuracy of the model under different noise conditions.

In contrast, models such as CLFormer and MobileNetV2 show a significant drop in accuracy under noise interference, achieving average accuracies of only 52.25% and 55.31%, respectively. These results suggest that their robustness is limited, making them less suitable for deployment in high-noise industrial environments.

4.2.3. Impact Analysis of Individual Modules on Diagnostic Performance

In this section, we conduct a series of comparative experiments using small-sample data from Dataset A under −4 dB noise conditions to investigate the contribution of each model component to overall diagnostic performance. Specifically, key modules such as DMFEM and MDSAM are selectively removed or replaced, while keeping the dataset and training strategies consistent, to evaluate their impact on accuracy, robustness, and generalization. The specific experimental results are presented in Table 8. This analysis aims to validate the effectiveness and necessity of the proposed architectural design.

Table 8.

Ablation Study of Model Components.

In Test 1, a standard Inception structure is adopted as the feature extractor. The experimental results show that the model achieves an average accuracy of 88.12%.

In Test 2, the lightweight DMFEM module is introduced, incorporating GhostConv and an improved multi-scale CNN structure, but without multi-stage residual block stacking, feature fusion, or Transformer/attention mechanisms. This configuration achieves a significantly improved accuracy of 90.62% while maintaining extremely low complexity—only 0.035 M parameters and 12.56 MFLOPs—demonstrating the superior feature extraction capability of the DMFEM module compared to the traditional Inception block.

In Test 3, three ResidualBlockWithFusion modules are cascaded, and intermediate features from each stage are fused to extract richer multi-scale temporal features. Although Transformer and attention modules are still not included, the model achieves 91.87% accuracy, with a slight increase in parameter count (0.039 M) and computational cost (13.23 MFLOPs). This highlights the positive impact of multi-stage residual design and feature fusion on representation learning.

In Test 4, a TransformerEncoder1D module is further added to enhance global modeling capabilities. While the MDSAM module is still excluded, accuracy increases to 92.34%, though at the cost of increased parameters (0.099 M) and FLOPs (14.022 MFLOPs). This indicates that the Transformer effectively captures long-range dependencies but introduces a trade-off in computational efficiency.

Finally, in Test 5, the complete model is constructed by integrating multi-stage DMFEM residual blocks, dynamic feature fusion, the Transformer encoder, and the customized MDSAM module. This configuration achieves the highest average accuracy of 93.13% while maintaining a compact model size (0.074 M parameters) and acceptable computational cost (13.55 MFLOPs). These results demonstrate that the improved attention mechanism further highlights critical feature regions, significantly enhancing model robustness and discriminative capability under noisy conditions.

5. Discussion

This study proposes LiMS-MFormer, a lightweight multi-scale and multi-dimensional Transformer-based model for intelligent fault diagnosis under small-sample and noisy conditions. Through systematic architectural design, the model integrates multi-scale temporal feature extraction via DMFEM, hierarchical residual fusion, global dependency modeling through a lightweight Transformer encoder, and the multi-dimensional self-attention mechanism MDSAM. These modules collectively enhance the model’s ability to extract discriminative features while maintaining high computational efficiency.

Experiments on the PU dataset and the University of Ottawa dataset demonstrate that LiMS-MFormer consistently meets its design objectives. On the PU dataset, the model achieves diagnostic accuracies of 96.68%, 98.98%, and 99.61% under increasingly large, small-sample settings, showing stable convergence and strong generalization even when trained with limited data. On the University of Ottawa dataset, LiMS-MFormer achieves an accuracy of 99.35%, further confirming its adaptability across different bearing types and experimental environments. Under severe noise conditions, including minus 6 decibels, the proposed model still achieves an accuracy exceeding 85%, indicating its robustness in highly noisy environments.

Ablation studies verify the contribution of each architectural component. DMFEM improves multi-scale temporal representation, residual fusion strengthens feature aggregation, and MDSAM enhances high-dimensional feature refinement. Removing any of these modules leads to a noticeable drop in diagnostic accuracy, demonstrating that the final performance is achieved through their combined effect.

LiMS-MFormer maintains a compact structure with 0.074 million parameters and 13.55 million floating-point operations, offering clear advantages over other lightweight CNN and Transformer models. This balance between accuracy, robustness, and computational cost indicates strong potential for deployment in resource-constrained industrial applications. From the perspective of mechanics and machine construction, the proposed LiMS-MFormer provides a practical and implementable solution for fault diagnosis of rotating machinery and mechanical components. Its lightweight architecture enables integration into embedded monitoring units and on-site diagnostic systems, supporting condition-based maintenance, early fault detection, and reliability improvement of mechanical equipment. These features are especially important for contemporary machine construction systems, where real-time monitoring, constrained computational resources, and high operational reliability are essential. Overall, LiMS-MFormer provides an effective and efficient solution for fault diagnosis tasks characterized by limited labeled data, varying operating conditions, and strong noise interference. While the experiments were conducted using laboratory datasets, both the PU and uOttawa datasets include sensor modalities and operating conditions that closely mirror those found in real industrial scenarios. Furthermore, deliberate noise injection experiments were carried out to simulate challenging industrial conditions, ensuring that the evaluation setup is highly representative of practical environments. Although this study evaluates the model under fixed benchmark settings typical of laboratory-based mechanical fault diagnosis experiments, cross-operating-condition generalization remains a critical consideration for real-world deployment. Future work will extend the model to cross-condition learning, including evaluating cases where training is performed under one load or speed condition and testing under another. This will more comprehensively verify and enhance the model’s robustness under real-world condition variations and further strengthen its adaptability to different loads and rotational speeds.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.C. and Y.Z.; methodology, H.C. and C.D.; software, H.C.; validation, H.C., C.D. and L.J.; formal analysis, H.C.; investigation, H.C.; resources, Y.Z.; data curation, C.D. and L.J.; writing—original draft preparation, H.C.; writing—review and editing, C.D. and Y.Z.; visualization, H.C.; supervision, Y.Z.; project administration, Y.Z.; funding acquisition, Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported in part by the Jiangsu Province Agricultural Science and Technology Independent Innovation Fund, grant number CX24-1022.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in [Paderborn University Bearing Data Center] at [https://mb.uni-paderborn.de/en/kat/research/bearing-datacenter/data-sets-and-download (accessed on 23 November 2025)], reference number [32]; and [Bearing Vibration Data under Time-varying Rotational Speed Conditions] at [https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/v43hmbwxpm/1 (accessed on 23 November 2025)], reference number [39].

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the administrative and technical support provided during this research, as well as the assistance from colleagues for valuable discussions and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Pandiyan, M.; Narendiranath, B.T. Systematic Review on Fault Diagnosis on Rolling-Element Bearing. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 2024, 12, 8249–8283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhi, T.B.; Malinda, V.; Seungchul, L.; Sunghoon, L. Recent Advances in the Application of Deep Learning for Fault Diagnosis of Rotating Machinery Using Vibration Signals. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 4667–4709. [Google Scholar]

- Gangsar, P.; Tiwari, R. Signal-Based Condition Monitoring Techniques for Fault Detection and Diagnosis of Induction Motors: A State-of-the-Art Review. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2020, 144, 106908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane, D.; Bouadjenek, M.R.; Dazeley, R.; Aryal, S. Data-Driven Machinery Fault Diagnosis: A Comprehensive Review. Neurocomputing 2025, 627, 129588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, D.; Zhen, D. A Novel Weighted Sparse Classification Framework with Extended Discriminative Dictionary for Data-Driven Bearing Fault Diagnosis. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 222, 111777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, K.; Liao, A.; Hu, D.; Shi, W.; Liu, R.; Sun, C. Simulation Data-Driven Fault Diagnosis Method for Metro Traction Motor Bearings under Small Samples and Missing Fault Samples. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2024, 35, 105117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Shao, H.; Han, S.; Huo, Z.; Wan, J. Novel Joint Transfer Network for Unsupervised Bearing Fault Diagnosis from Simulation Domain to Experimental Domain. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2022, 27, 5254–5263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Qin, C.; Zhang, Z.; Tao, J.; Liu, C. A Multi-Scale Convolutional Neural Network for Bearing Compound Fault Diagnosis under Various Noise Conditions. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2022, 65, 2551–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Wang, F.; Yang, B.; Qin, S.J. Multiscale Kernel-Based Residual Convolutional Neural Network for Motor Fault Diagnosis under Nonstationary Conditions. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 16, 3797–3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Deng, J.; Chen, D.; Jiang, W.; Shao, S.; Tang, M.; Liu, J. You Can Get Smaller: A Lightweight Self-Activation Convolution Unit Modified by Transformer for Fault Diagnosis. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2023, 55, 101890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Jiang, Q.; Shen, Y.; Qian, C.; Xu, F.; Zhu, Q. Application of recurrent neural network to mechanical fault diagnosis: A review. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2022, 36, 527–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Sun, S.; Jin, B. Sequential Fault Diagnosis Based on LSTM Neural Network. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 12929–12939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nacer Saadi, M.; Bouteraa, N.; Redjati, A.; Boughazi, M. A novel method for bearing fault diagnosis based on BiLSTM neural networks. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 125, 1477–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Yang, S.; Fujita, H.; Chen, D.; Wen, C. Deep learning fault diagnosis method based on global optimization GAN for unbalanced data. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2020, 187, 104837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, Z.; Ma, J.; Li, T. Diagnosisformer: An efficient rolling bearing fault diagnosis method based on improved Transformer. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 124, 106507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, X. Imbalanced fault diagnosis of rolling bearing using improved MsR-GAN and feature enhancement-driven CapsNet. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 168, 108664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Hou, L.; Chen, Y. A Time Series Transformer based method for the rotating machinery fault diagnosis. Neurocomputing 2022, 494, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, W.; He, Y. A hybrid approach combining deep learning and signal processing for bearing fault diagnosis under imbalanced samples and multiple operating conditions. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Liu, J.; Xie, J.; Wang, C.; Ding, T. Conditional GAN and 2-D CNN for Bearing Fault Diagnosis with Small Samples. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 3525712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Su, X.; Yang, J.; Du, S.; Wang, D.; Ran, Q. An Improved Dual-Channel Cnn-Bilstm Fusion Attention Model for Fault Diagnosis of Aero-Engine Bearings. Measurement 2025, 253, 117761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas Jibin, B.; Chaudhari, S.G.; Shihabudheen, K.V.; Verma, N.K. CNN-Based Transformer Model for Fault Detection in Power System Networks. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 2504210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalayer, M.; Orsenigo, C.; Vercellis, C. Fault detection and diagnosis for rotating machinery: A model based on convolutional LSTM, Fast Fourier and continuous wavelet transforms. Comput. Ind. 2021, 125, 103378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. MobileNets: Efficient Convolutional Neural Networks for Mobile Vision Applications. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, X.; Lin, M.; Sun, J. ShuffleNet: An Extremely Efficient Convolutional Neural Network for Mobile Devices. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 6848–6856. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q.V. EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.11946. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Shao, H.; Yan, S.; Liu, B. C-ECAFormer: A new lightweight fault diagnosis framework towards heavy noise and small samples. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 126, 107031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Tang, J.; Sun, N.; Wang, S. A hybrid deep learning model for fault diagnosis of rolling bearings using raw vibration signals. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2024, 35, 096201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Yan, R.; Wang, J.; Mao, K. Learning to Monitor Machine Health with Convolutional Bi-Directional LSTM Networks. Sensors 2017, 17, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, K.; Wang, Y.; Tian, Q.; Guo, J.; Xu, C.; Xu, C. GhostNet: More Features From Cheap Operations. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 1577–1586. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.03762. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Lessmeier, C.; Kimotho, J.K.; Zimmer, D.; Sextro, W. Condition Monitoring of Bearing Damage in Electromechanical Drive Systems by Using Motor Current Signals of Electric Motors: A Benchmark Data Set for Data-Driven Classification. PHM Soc. Eur. Conf. 2016, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Z.; Chen, Y.; Chen, J.; Yang, J. A Bearing Fault Diagnosis Method Based on Vibration Signal Extension and Time–Frequency Information Fusion Network under Small Sample Conditions. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 27712–27727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Goodacre, R. On Splitting Training and Validation Set: A Comparative Study of Cross-Validation, Bootstrap and Systematic Sampling for Estimating the Generalization Performance of Supervised Learning. J. Anal. Test. 2018, 2, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Shao, H.; Wang, J.; Zheng, X.; Liu, B. LiConvFormer: A lightweight fault diagnosis framework using separable multiscale convolution and broadcast self-attention. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 237, 121338. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.; Shao, H.; Cheng, J.; Yang, X.; Cai, B. Convformer-NSE: A Novel End-to-End Gearbox Fault Diagnosis Framework Under Heavy Noise Using Joint Global and Local Information. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2023, 28, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Deng, J.; Bai, Y.; Feng, B.; Li, S.; Shao, S.; Chen, D. CLFormer: A Lightweight Transformer Based on Convolutional Embedding and Linear Self-Attention With Strong Robustness for Bearing Fault Diagnosis Under Limited Sample Conditions. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 3504608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, J.; Liu, S.; Feng, Y.; He, S.; Xu, E. Multi-channel Calibrated Transformer with Shifted Windows for few-shot fault diagnosis under sharp speed variation. ISA Trans. 2022, 131, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.-C. MobileNetV2: Inverted Residuals and Linear Bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 4510–4520. [Google Scholar]

- Sehri, M.; Dumond, P.; Bouchard, M. University of Ottawa constant load and speed rolling-element bearing vibration and acoustic fault signature datasets. Data Brief 2023, 49, 109327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.