1. Introduction

Composite materials are composed of two or more constituent materials with distinct chemical and physical properties [

1]. Compared to traditional materials such as aerospace aluminum alloys, composite materials exhibit superior strength-to-weight and stiffness-to-weight ratios, enabling significant weight reduction and performance enhancement [

2]. The application of composite materials in civil aircraft is illustrated in

Figure 1 [

3]. While the adoption of composite structures in aircrafts offers numerous advantages, it also presents a series of challenges, particularly in the inspection and monitoring of structural damage. Damage in composite materials is often concealed within the internal layers and cannot be reliably detected by visual inspection of the outer surface alone; even when surface indications are visible, extensive internal damage may already exist [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Furthermore, the damage mechanisms and propagation behaviors in composite aircraft structures are complex and highly variable, making it extremely challenging to predict damage progression under operational loads [

8]. If defects in the structure are not addressed in a timely manner, they may propagate throughout the entire structure, potentially leading to catastrophic consequences. Therefore, effective monitoring of such structures is essential to ensure safety while reducing maintenance costs [

9].

In the field of SHM for aircraft, achieving long-term, continuous, and online monitoring of structural conditions represents a core requirement. However, conventional non-destructive testing (NDT) techniques, such as ultrasonic testing, acoustic emission testing, and X-ray inspection, generally require offline operation. This involves prolonged inspection cycles, and struggles to provide real-time feedback. Moreover, specialized personnel are heavily relied on for operation and analysis, leading to relatively high overall application costs. These traditional approaches have inherent limitations in achieving long-term, real-time, and distributed monitoring. Especially in the aerospace sector where reliability demands are extremely stringent, they have driven the development of a new generation of monitoring technology—optical fiber sensing. The optical fiber sensing technology measures external physical parameters such as strain, temperature, pressure, and vibration by detecting changes in the characteristics of light signals (e.g., intensity, phase, wavelength, and polarization state) propagating through optical fibers. Integrating knowledge from multiple disciplines including laser optics, fiber optics, optoelectronics, microelectronics, artificial intelligence, composite materials science, and structural engineering, it has evolved into an emerging interdisciplinary branch of engineering technology [

10]. In SHM technology for aerospace composite structures, optical fiber sensors can be deployed by surface attachment or embedding within the composite material. Parameters such as strain and temperature in critical areas can be monitored in real time. This technology significantly enhances the capability to perceive structural health conditions, helps reduce unnecessary maintenance operations, and holds the potential to replace certain routine manual inspections. Ultimately, it demonstrates considerable potential for improving aircraft safety and reliability, as well as extending structural service life [

11,

12].

Since the mid-1990s, optical fiber sensing technology has progressively been applied in the field of aviation SHM. In the United States, NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center initiated relevant research in the 1990s and completed a prototype flight test of a Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) sensing system on an F/A-18 fighter aircraft in 1999. This achievement demonstrates the feasibility of strain monitoring under real-world flight conditions [

13]. Similarly, the Korea Society for Aeronautical & Space Sciences utilized FBG sensors to conduct flight strain monitoring on the tail-beam structure of an ultra-light composite aircraft, with the acquired data effectively validated against flight parameters [

14]. These studies indicate that the optical fiber sensing technology has evolved from the stage of feasibility verification into practical engineering application, providing a reliable technical means for the aircraft SHM.

With the rapid development of artificial intelligence technology, optical fiber sensing systems have achieved significant progress in data processing and condition identification. Therefore, traditional data acquisition tools have evolved into systems with “intelligent perception and cognitive capabilities”. For instance, Candelieri et al. [

15] proposed an online monitoring framework based on Support Vector Machines (SVM) for real-time evaluation of strain fields and structural health in aircraft fuselage panels. On the other hand, Mishra et al. [

16] achieved accurate localization of delamination damage in composite laminates by constructing damage index vectors and employing Probabilistic Neural Networks (PNN). These studies demonstrate the broad application prospects of integrating optical fiber sensing with intelligent algorithms in the aerospace SHM.

In summary, the SHM technology enables real-time acquisition and transmission of operational status information from aircraft structures, significantly extending the service life of aerospace components and optimizing maintenance cost-effectiveness. This paper focuses on the SHM technology for aerospace composite structures, systematically elaborating on optical fiber sensing-based monitoring methods and their research advancements. It provides an in-depth analysis of the key scientific issues and engineering challenges within the current technological framework, and further discusses future development directions of this technology in the field of aerospace engineering. The work aims to offer theoretical support and technical reference for the innovation and application of composite SHM technology.

2. Advances in Optical Fiber Sensing Based SHM Technology

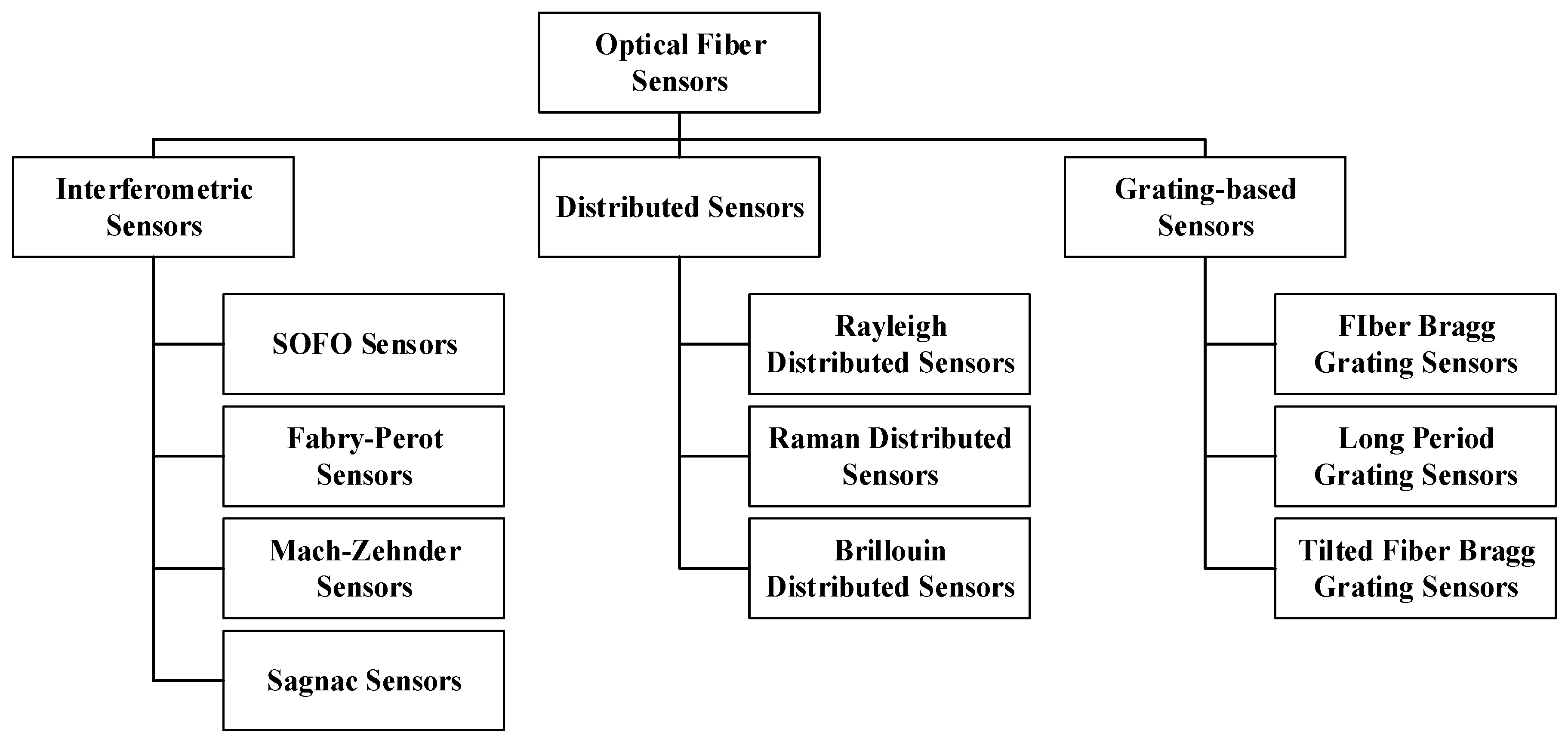

The optical fiber Sensing Based SHM technology has witnessed rapid development in recent years, achieving remarkable progress in enhancing monitoring accuracy, enriching sensing dimensions, and enabling multifunctional integration. Current innovations are primarily driven by advancements in distributed measurement capabilities, multi-parameter fusion, and the development of novel sensors. For instance, Brillouin scattering technology can achieve monitoring ranges extending over hundreds of kilometers with meter-scale spatial resolution. Meanwhile, Optical Frequency Domain Reflectometry (OFDR) has demonstrated the ability to monitor bending deformations in composite materials by analyzing the inherent birefringence changes within the optical fiber itself. The developmental trajectory of optical fiber sensing technology is illustrated in

Figure 2, while a comparative analysis of the characteristics of various optical fiber sensing techniques is summarized in

Table 1.

2.1. FBG-Based Optical Fiber Sensing Technology

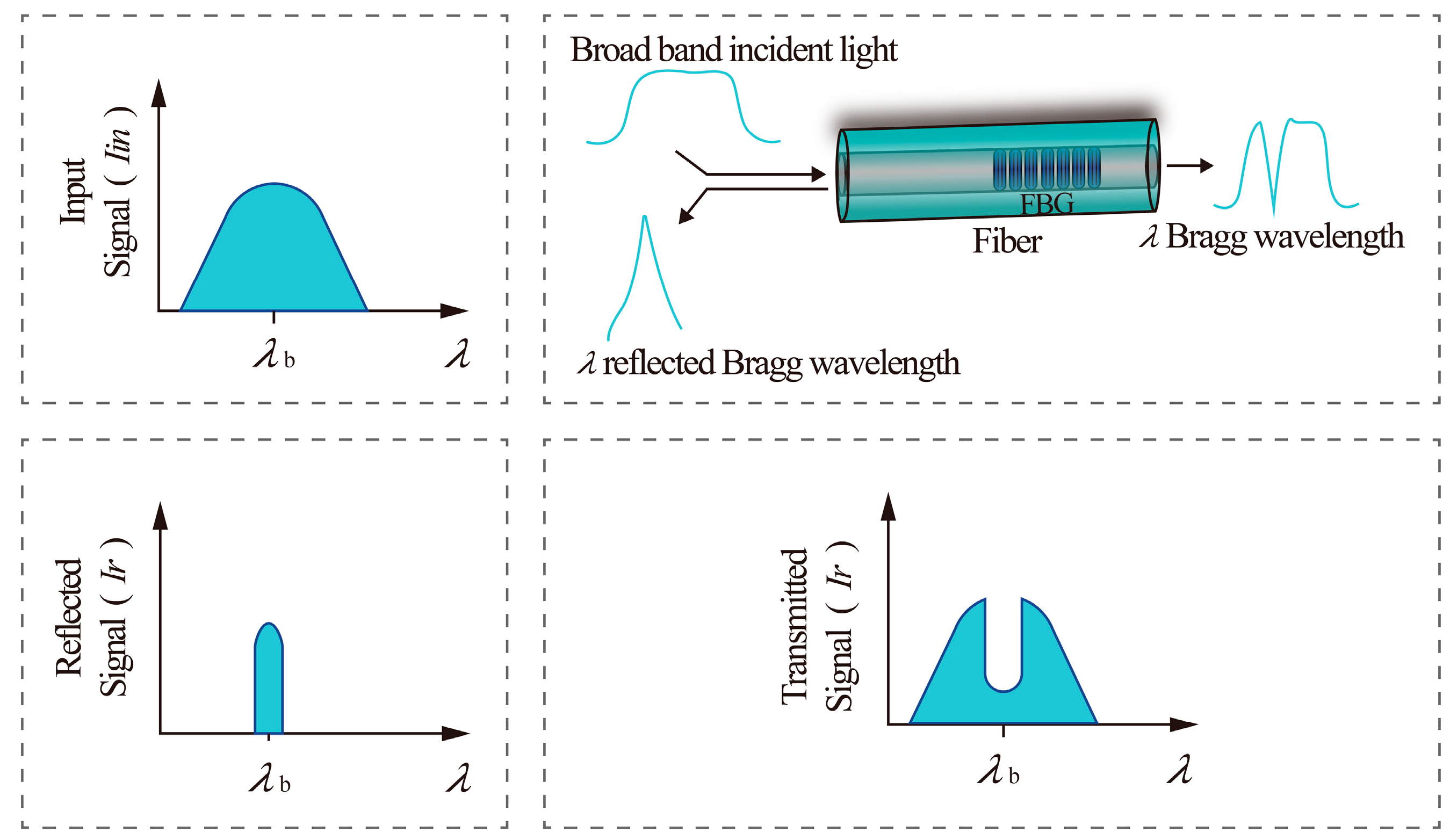

An FBG is a wavelength-selective filter, created by inscribing a Bragg grating into the fiber core to introduce a periodic modulation of the refractive index along the fiber’s axial direction. Its wavelength selectivity originates from multiple Fresnel reflections caused by this refractive index modulation and their subsequent coherent interference. Specifically, an FBG reflects light that satisfies the Bragg condition, as given by Equation (1) [

18]:

λB denotes the central wavelength of the FBG’s reflected light,

Λ represents the spacing of the periodic refractive index modulation within the FBG, and

neff is the effective refractive index of the fiber core. Schematic diagrams of the FBG structure and its working principle are provided in

Figure 3.

2.2. Distributed Optical Fiber Sensing Technologies

Distributed Optical Fiber Sensing (DOFS) is a technology that utilizes the optical fiber itself as a continuous sensing medium. It enables the measurement of physical parameters—such as temperature, strain, and vibration—over long distances and with high spatial resolution, by analyzing the scattering or reflection signals of light propagating within the fiber.

2.2.1. Light Scattering in Optical Fibers

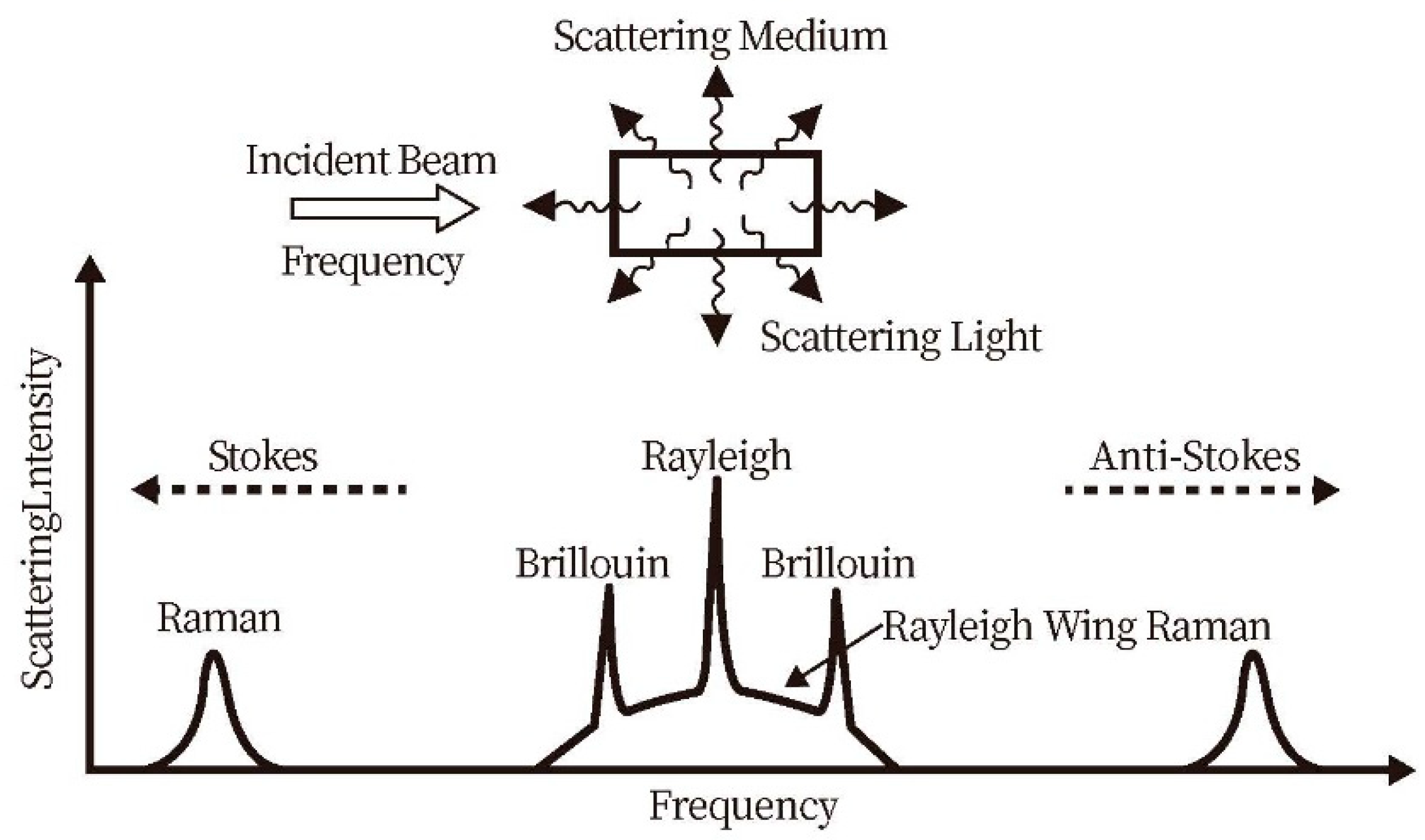

DOFS primarily relies on three light scattering effects: Rayleigh Scattering, Brillouin Scattering, and Raman Scattering. A typical spontaneous light scattering spectrum is illustrated in

Figure 4. This figure summarizes the three main scattering processes and their frequency characteristics when light propagates through a scattering medium. In the center is Rayleigh scattering, which has the same frequency as the incident light and belongs to elastic scattering. On either side, with slightly lower or higher frequencies, is Brillouin scattering. The scattering with the largest frequency shift is Raman scattering, which includes the Stokes line (energy loss) and the anti-Stokes line (energy gain), corresponding to transitions in molecular vibrational energy levels. The entire figure clearly illustrates the spectral distribution from elastic to inelastic scattering, showing a gradual increase in frequency shift.

2.2.2. Optical Time-Domain Reflectometry (OTDR)

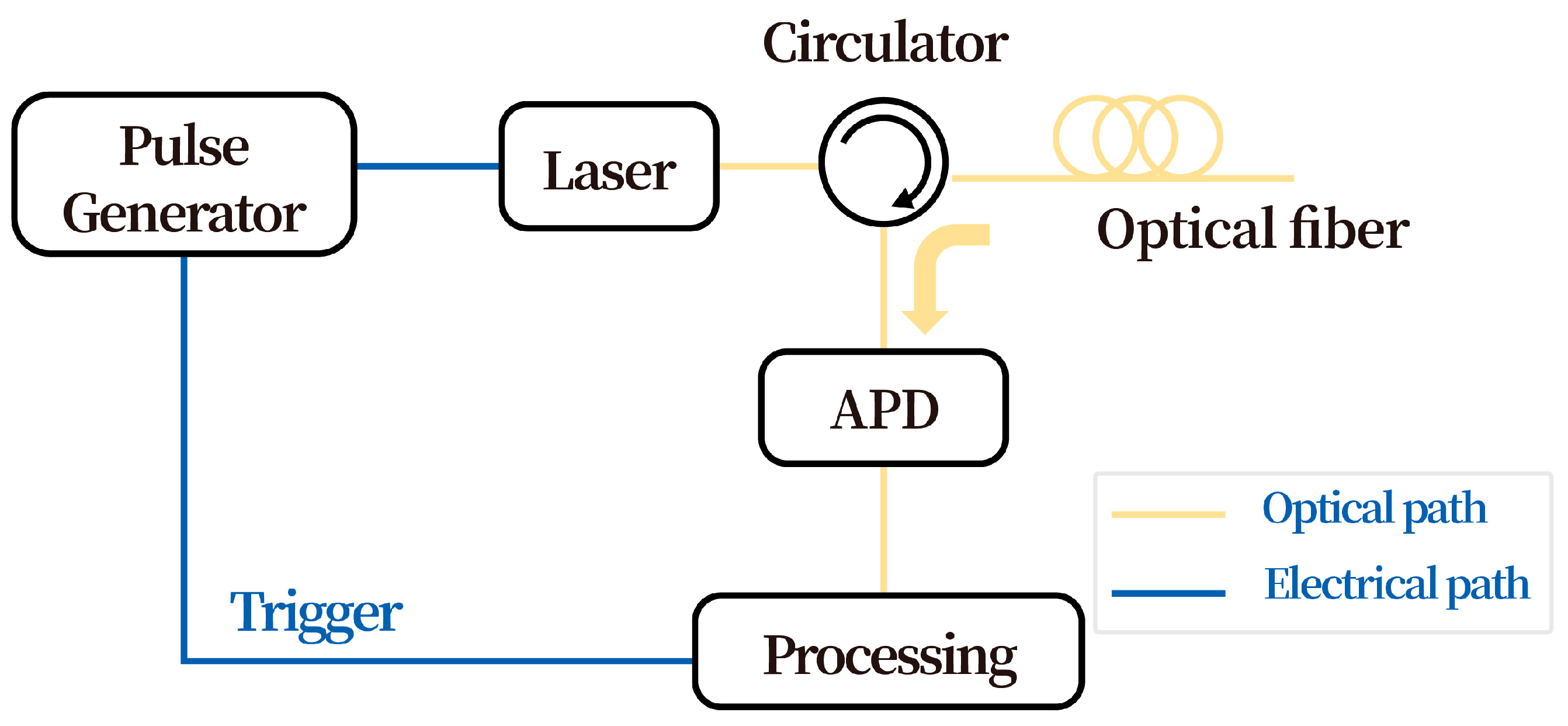

OTDR technology was first proposed by Barnoski and Jensen [

21], applying the concept of laser radar. It was initially developed to monitor the operational status of optical communication links. Specifically, the losses and breaks in the optical fibers can be detected, with faults spatially located. The operating principle of an OTDR system is schematically illustrated in

Figure 5.

When an optical pulse propagates through an optical fiber, scattering and reflection occur due to factors such as intrinsic attenuation, connectors, splices, and bends. The backscattered Rayleigh light and Fresnel reflected light travel back toward the input end, with Rayleigh scattering being the dominant component. By analyzing the relationship between the returned optical power and its round-trip time, the loss distribution along the fiber link can be determined.

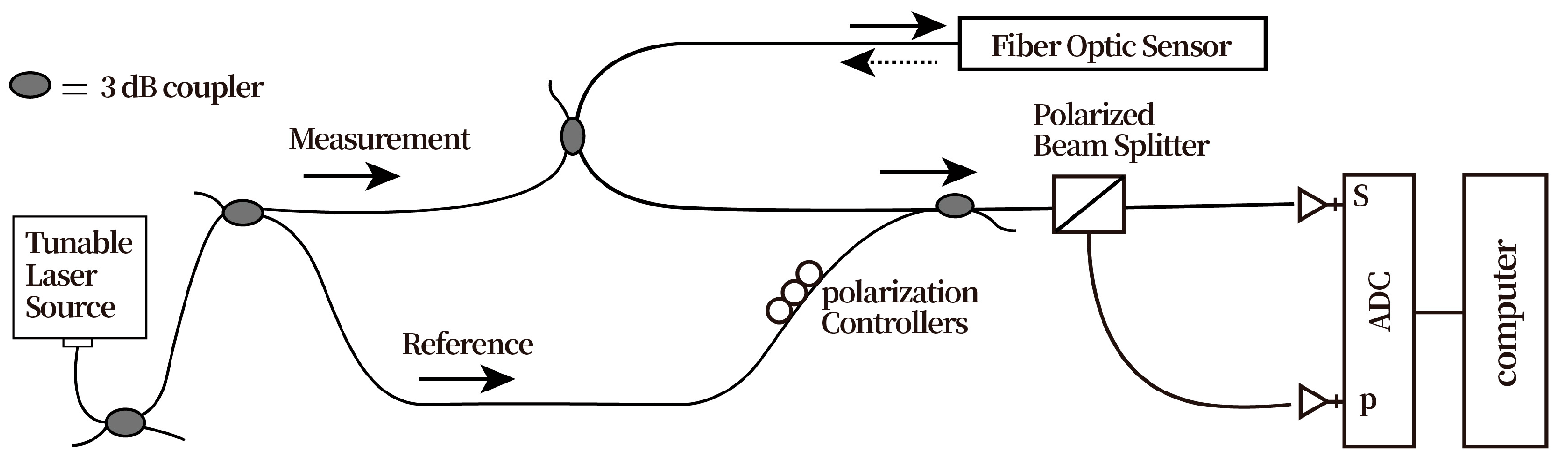

2.3. DOFS-Based Monitoring Technology for Aeronautical Composite Structures

The OFDR technology, with its millimeter-level spatial resolution (0.6–10 mm) and a dynamic range exceeding 20,000 µε, has become the preferred technique for SHM of aeronautical composite materials. The OFDR technology was first proposed by Froggatt et al. [

23] in 1998. It locates scattering points by analyzing the frequency characteristics of the backscattered Rayleigh signal generated by a frequency-modulated probe light. This method offers distinct advantages, including superior spatial resolution and lower requirements for optical probe power. A schematic diagram of its operating principle is shown in

Figure 6.

Under the extreme service regimes encountered by aeronautic equipment, the OFDR technology retains its intrinsic merit of high spatial resolution. However, it is simultaneously constrained by three inter-related limitations: a precipitous loss of temperature sensitivity, an ultra-weak backscattered signal, and a temperature–strain cross-coupling that is difficult to compensate effectively. To overcome these constraints, the industry has converged on a hierarchical “hardware–algorithm–deployment” co-design paradigm. In critical zones where accuracy and operational reliability are non-negotiable, reference-fiber hardware decoupling remains the fundamental safeguard; when the simultaneous attainment of large measurement range, high spatial resolution and high signal-to-noise ratio is pursued, advanced software algorithms—adaptive range scaling and image filtering—become the dominant performance lever; for cryogenic or geometrically confined environments, innovative sensor-network topologies coupled with dedicated low-temperature decoupling models provide a new solution. Collectively, these complementary measures establish a full-chain temperature–strain separation framework that is genuinely qualified for extreme aerospace environments.

The anisotropic nature of composite materials may cause challenges such as weak interfacial bonding and strain transfer distortion. In response, in sensor embedding and packaging, a glass fiber/epoxy substrate encapsulation chemically compatible with the matrix is adopted to achieve covalent bonding and reduce transfer loss. Simultaneously, pre-tensioned FBGs are embedded within the plies to offset curing-induced thermal residual stress, thereby preventing reflection spectrum chirping and enhancing stability and repeatability. Subsequently, at the interfacial theory level, a strain transfer model and an analytical solution for interfacial shear stress are established to quantify the impact of debonding on strain measurements. This informs the adjustment of process parameters, such as the substrate pre-curing degree, to strengthen the bond. Finally, based on anisotropic stress field analysis, the orientation and placement of the gratings are optimized to achieve high-sensitivity capture of specific principal strains, thereby systematically improving the accuracy and reliability of composite material monitoring.

3. Application Research of Optical Fiber Sensing Based SHM Technology

This section reviews the research and application of SHM technology by scholars. The representative cases include typical aircraft composite structures, composite material curing process monitoring, and composite impact damage.

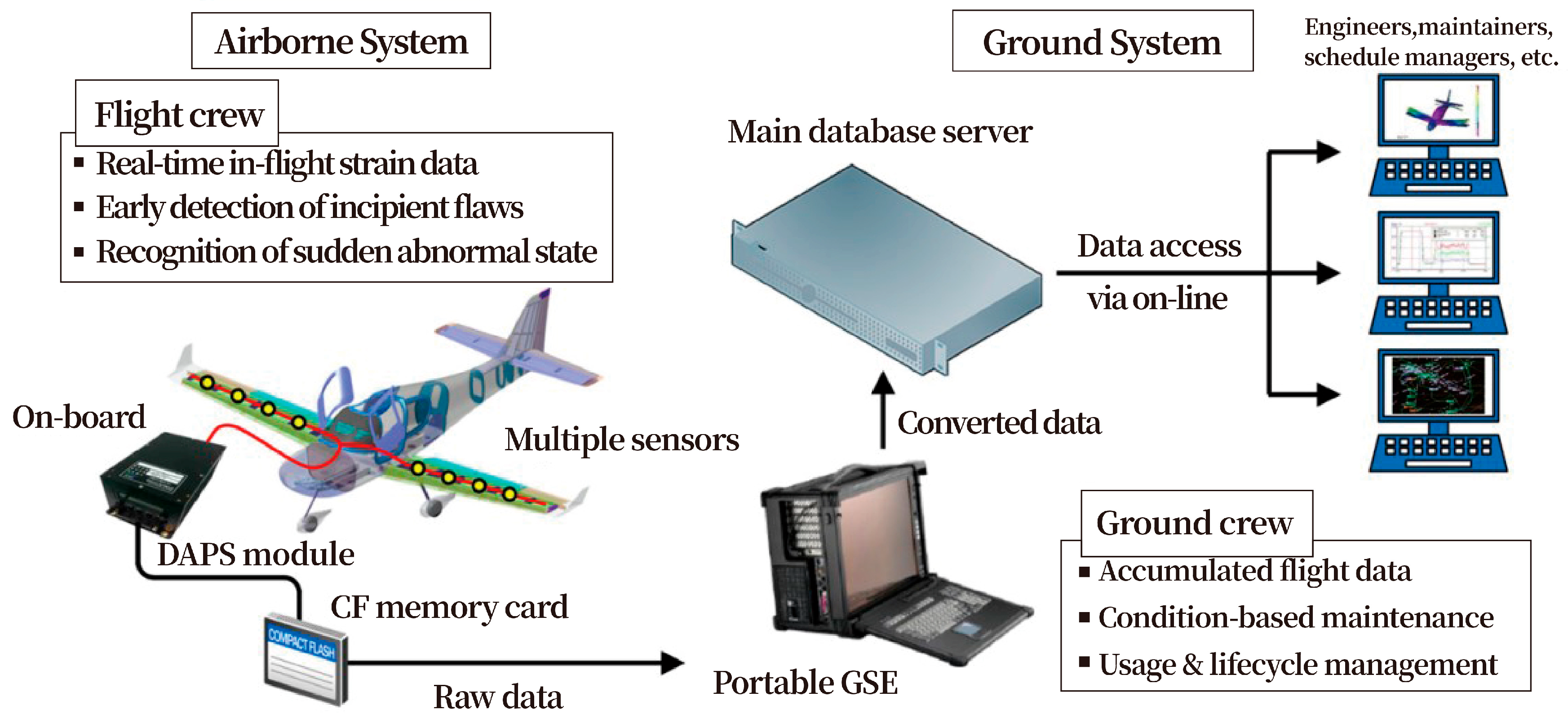

3.1. Aircraft Wing Structures

The Department of Aerospace Engineering at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science & Technology (KAIST) developed a FBG sensor-based aircraft Health and Usage Monitoring System (HUMS) and integrated it into the wing structure of an ultra-light aircraft. This system enabled the efficient collection and analysis of strain state during flight operations. Results from both ground and flight tests demonstrated the system’s robust monitoring capability under various maneuvering conditions. For instance, during turning maneuvers, the left and right wings exhibited opposing strain trends, with the left wing reaching a maximum strain of −180 µε and the right wing reaching −260 µε. These findings validate the system’s feasibility and reliability in real-flight environments [

25].

Figure 7 illustrates the conceptual diagram of the HUMS based on FBG for in-flight strain measurement.

Building upon this foundation, recent years have witnessed a deepening application of optical fiber sensing technology in aerospace SHM. The technology has evolved from single-parameter measurement towards multi-parameter, distributed, and collaborative monitoring. For instance, Datta et al. [

26] utilized a DOFS system to identify and localize debonding damage in a wing structure, employing a Damage Index (DI) to quantify its severity and achieving a localization error within 11 mm. This demonstrates the potential of high-spatial-resolution sensing algorithms for structural damage diagnosis. Concurrently, Gui et al. [

27] integrated distributed acoustic sensing (DAS) with FBG arrays, proposing an integrated method for ice detection and temperature field monitoring during de-icing processes. This method expands the multifunctional application scenarios of optical fiber sensing in flight safety monitoring. In data processing and reconstruction, Liu et al. [

28] developed a 3D position correction algorithm based on FBG arrays. By combining biharmonic interpolation with spline interpolation methods, they controlled the relative error in the wing structure’s fitted reconstruction to within 5%, significantly enhancing the accuracy of structural state reconstruction and the system’s compensation performance.

Despite the promising application prospects of optical fiber sensing technology in aircraft structural monitoring demonstrated by the aforementioned studies, current systems still exhibit certain limitations. These include insufficient decoupling of the cross-sensitivity effects between monitored parameters, inadequate capabilities for the fused analysis and intelligent diagnosis of multi-source sensor data, and the need for further validation of long-term sensor stability and reliability in real-world, complex flight environments. Future research should focus on developing intelligent monitoring systems with self-diagnostic and self-adaptive capabilities. By integrating physics-based models with data-driven approaches, such systems can achieve a transition from mere “condition sensing” to “health prediction”, thereby advancing aircraft health management towards a more digital and intelligent paradigm.

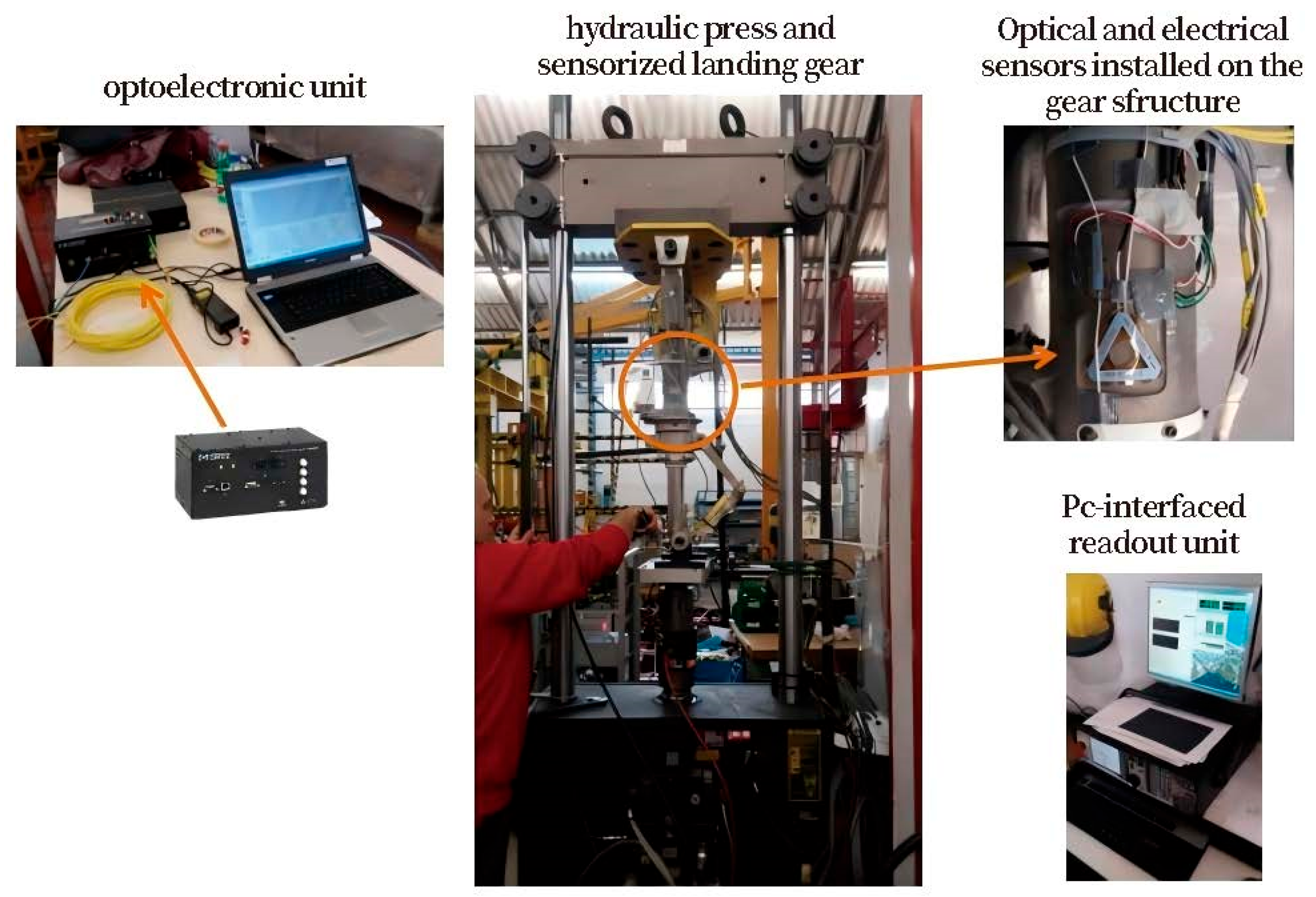

3.2. Aircraft Landing Gear Structure

The Italian Aerospace Research Centre successfully integrated FBG sensors into an aircraft landing gear system, enabling the real-time remote monitoring of loads on both the main and nose landing gears. Experimental results demonstrated a high degree of consistency between the strain data acquired by the FBG sensors and measurements from conventional strain gauges. Moreover, the optical fiber sensing system is also validated feasible and accurate for operation in the complex loading environment of landing gears [

29].

Figure 8 illustrates the experimental setup for aircraft landing gear monitoring based on FBG.

With continuous advancements in sensing technology and data analysis methods, landing gear monitoring systems are evolving towards an integrated “Sensing-Data-Model” paradigm. The core of this development lies in utilizing high-precision sensing and intelligent algorithms to achieve accurate load inversion and prediction. At the sensor level, Wang et al. [

30] and Li et al. [

31] have developed lightweight, highly sensitive FBG strain sensors with strain sensitivities of 1.30 pm/µε and 1.14 pm/µε, respectively, and measurement accuracies both superior to 2.5%. These advancements provide a reliable hardware foundation for load identification. In data processing and modeling, various intelligent algorithms have been introduced to construct the strain-load mapping relationship. The Long Short-Term Memory Kolmogorov-Arnold Network (LSTM-KAN) model proposed by Feng et al. [

32] has surpassed traditional neural networks and regression methods in predictive accuracy, demonstrating superior generalization capability.

Notwithstanding the notable progress in sensor performance and algorithmic accuracy achieved by the aforementioned studies, current monitoring systems for landing gears still face several challenges. On the one hand, most models still rely on data from static ground load tests, and their generalization capability and robustness under real flight conditions (dynamic loads such as landing impacts and taxiing vibrations) have not been fully validated. On the other hand, the lack of a unified benchmarking framework for different algorithms makes it difficult to objectively compare their engineering applicability. Furthermore, existing systems still have room for improvement in areas such as strain-load decoupling, multi-physics coupling modeling, and model interpretability. Future research should place greater emphasis on the model transferability under dynamic loading conditions, facilitating a transition from “laboratory accuracy” to “operational robustness”. This will explore hybrid modeling paths that integrate physical mechanisms, so as to construct highly reliable health monitoring systems for landing gears that are applicable across the entire flight envelope.

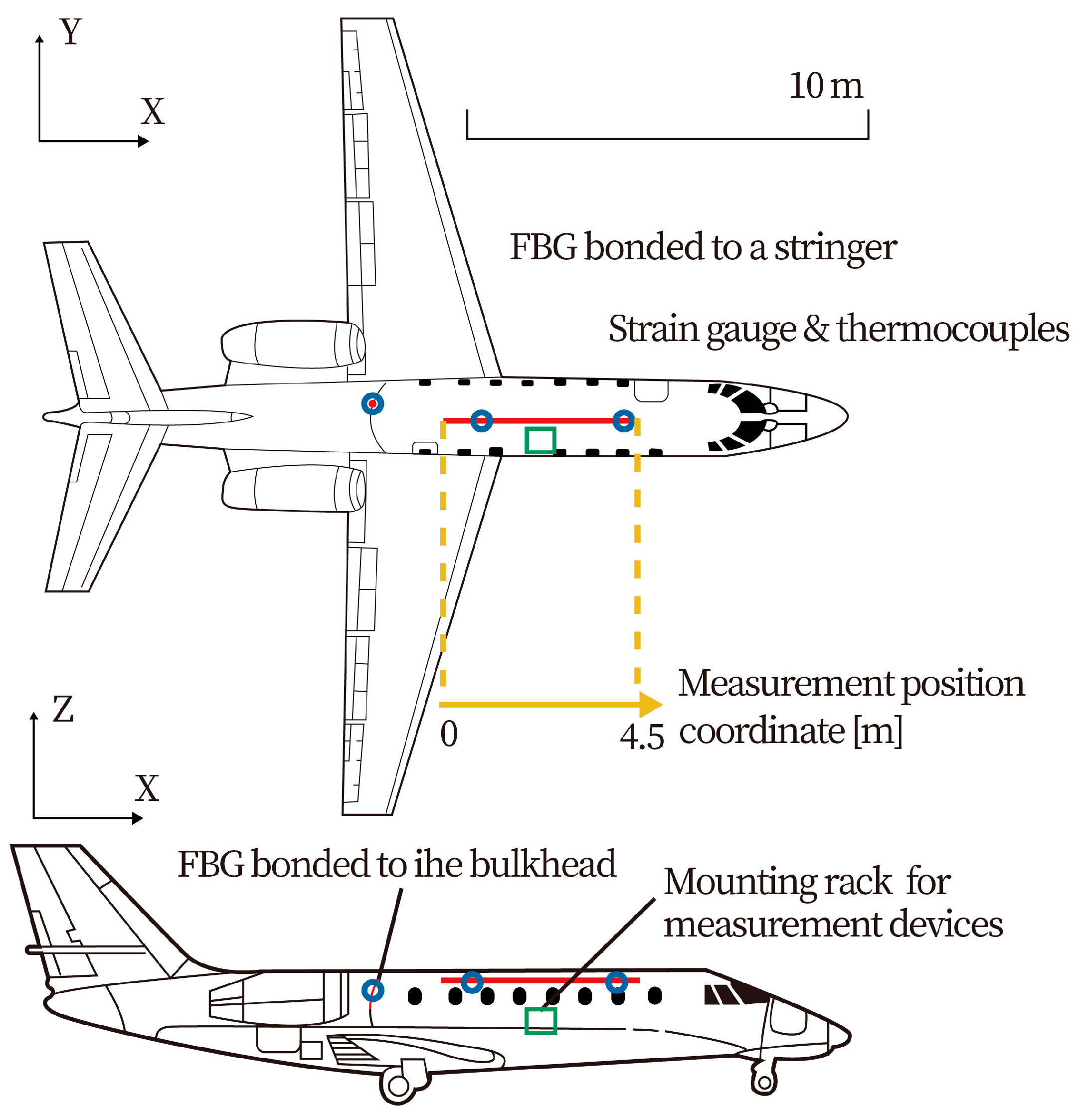

3.3. Aircraft Fuselage Structure

The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) has successfully applied an OFDR DOFS system to the structural monitoring of a medium-sized jet airliner. Based on the long fiber Bragg Grating technology, the system offers tunable spatial resolution ranging from millimeter to sub-millimeter scales, enabling the real-time acquisition of structural strain distribution. Flight test data revealed that during the aircraft landing process, the tensile strain at the stringer location increased significantly from approximately 100 µε before touchdown to about 200 µε, subsequently decaying gradually to zero upon landing. This clearly captured the response process of the aircraft structure under dynamic loads and validated the system’s capability to effectively monitor structural behavior during flight maneuvers [

33].

Figure 9 illustrates the configuration of the flight test bench and sensors.

Simultaneously, the integration of optical fiber sensing technology with advanced signal processing algorithms has further propelled the development of SHM toward greater intelligence. Loutas et al. [

34] developed a monitoring system based on FBG dynamic strain measurements. By employing discrete wavelet transform and support vector machines to analyze and process the collected vibration signals, they constructed an intelligent diagnostic model capable of identifying multiple damage states. Their study simulated 13 different damage scenarios on a composite panel. Also, vibration testing verified a high degree of consistency between the data acquired by the FBG sensors and finite element simulation results. This demonstrates the technical potential of integrating dynamic monitoring with intelligent diagnosis.

Despite the demonstrated advantages of OFDR and FBG technologies in monitoring structural strain and dynamic response, current systems still face several critical challenges in practical aviation applications. While OFDR systems offer high spatial resolution, their measurement real-time performance and data processing efficiency during high-speed dynamic events require further enhancement. For FBG-based dynamic monitoring systems, the generalization capability of their damage identification models and diagnostic accuracy under coupled multi-damage scenarios need additional validation. Furthermore, existing research predominantly focuses on single sensor types or specific flight phases, lacking a comprehensive monitoring framework that covers the entire flight profile and integrates multi-source sensory information. Future research will focus on developing intelligent monitoring systems with high sampling rates, robust anti-interference capability, and adaptive feature extraction. It will also explore the deep integration of optical fiber sensing with physical models and digital twin technology to achieve a transition from “response monitoring” to “condition prediction” and “health management”. Therefore, a key technological support will be supported for real-time status assessment and safety assurance in next-generation aircraft.

3.4. Composite Material Curing Process Monitoring

Optical fiber sensing technology is playing an increasingly vital role in monitoring composite material curing processes. Its core advantages lie in the precise, in situ measurement of key process parameters such as curing, resin flow, and shrinkage. During the manufacturing of thermoplastic composite materials, Tsukada et al. [

35] employed finite element simulation to reveal the internal strain evolution, thereby establishing a theoretical benchmark for experimental monitoring. Building upon this foundation, Oromiehie et al. [

36] developed a numerical model of the thermoplastic composite material forming process and compared the experimental strain data obtained from FBG sensors with the simulation results. The high degree of concordance between the two curves validated the accuracy and reliability of FBG monitoring within complex thermo-mechanically coupled environments, providing crucial data support for process optimization and quality control.

In Resin Transfer Molding (RTM) processes, Allsop et al. [

37] utilized FBG sensors to achieve real-time tracking of the resin flow front. By analyzing the sensor wavelength shifts, they elucidated the spectral response mechanism dominated by viscous forces and established a response model capable of accurately predicting the flow progression. This model provides a critical basis for optimizing injection parameters and ensuring complete fiber impregnation. For curing monitoring, Guo et al. [

38] successfully captured wavelength shifts induced by chemical shrinkage by embedding FBG sensors within a phenolic resin. They identified responses within the strain signals corresponding to different curing stages (such as solvent evaporation, methylolation, and condensation reactions), thereby confirming the capability of FBGs to quantify resin chemical shrinkage and correlate it with the curing progression.

To achieve comprehensive perception of the curing process, Chang et al. [

39] employed a synergistic monitoring approach using both FBG and thermocouple sensors to track the evolution of strain and temperature during laminate curing. Their research identified curing pressure as a critical factor influencing strain development, finding that increased pressure promotes fiber-resin consolidation and significantly suppresses strain fluctuations. This work provided initial insights into the relationship between process parameters (e.g., temperature, pressure) and the internal material state (strain), laying the groundwork for real-time sensor-based process control. Anelli et al. [

40] designed a microstructured flat optical fiber (MF-OF) capable of being embedded within composite materials, enabling high-precision, distributed monitoring of multiaxial strain. Okabe et al. [

41] systematically quantified the coating-crack detection sensitivity relationship, establishing a direct basis for the subsequent selection and interface design of FBG sensors for aerospace composites.

The aforementioned studies demonstrate the broad application of FBGs in composite material curing process monitoring; however, the current technological framework still faces several challenges. Firstly, most monitoring solutions have yet to achieve closed-loop integration with process control systems, making it difficult to dynamically adjust process parameters based on real-time sensor data. Secondly, for complex components or heterogeneous materials, sensor embedding may introduce structural weak points, and the sensor’s own influence on measurement results requires further evaluation. Furthermore, existing research predominantly focuses on monitoring single physical quantities, with the decoupling of signals and mechanistic modeling under multi-field coupled conditions (such as thermos-chemo-mechanical coupling) remaining inadequate. Future research should focus on developing intelligent curing systems that integrate “sensing-modeling-control” functions. Optical fiber sensing data will be deeply integrated with process physics-based models to construct digital twin platforms. Through real-time material state inversion and proactive process parameter adjustment, the platforms ultimately achieve precise control and enhanced quality consistency in composite material manufacturing processes.

3.5. Impact Damage Monitoring of Composite Structures

Optical fiber sensing technology demonstrates significant potential in monitoring impact damage of composite materials. Its core advantages lie in the rapid localization of damage, visual identification of internal states, and effective assessment of damage severity. For impact localization, Shrestha et al. [

42] developed a novel localization algorithm based on outlier analysis and employed a high-speed FBG interrogation system to monitor multiple impact points on a composite structure. Experimental results demonstrated that the average localization error of this algorithm was only 10.7 mm, a precision significantly superior to traditional methods based on root mean square or correlation analysis. This provides an effective solution for the real-time monitoring of complex structures under multi-impact scenarios.

For in-depth perception and validation of internal damage, to further elucidate the internal damage state induced by impact, Batte et al. [

43] embedded distributed optical fiber sensors at varying depths within a composite laminate and conducted comparative validation using ultrasonic C-scan and CT imaging results. The study revealed a high degree of concordance between the peak strain signals from the optical fibers and the delamination areas identified in the ultrasonic images. Notably, even at the 50th ply, the farthest from the impact point, the embedded optical fibers effectively captured delamination information, demonstrating the strong suitability of optical fiber sensing technology for identifying internal damage depth in composite materials. In terms of damage state modeling and real-time identification, Tang et al. [

44] proposed a 3D optical fiber sensing network embedded between the layers of a carbon fiber-reinforced polymer (CFRP). By constructing a correlation model for the strain distribution along the thickness direction during impact, they introduced a Damage Index (DI-IR) for determining the damage state. Experiments confirmed that this method can effectively achieve online damage identification and state assessment in CFRP structures during impact events.

Despite the positive progress in optical fiber sensing technology for impact monitoring, current systems still face several challenges in practical applications. Most research remains at the laboratory validation stage, lacking systematic verification of long-term stability and reliability under complex operational conditions or in real flight environments. Furthermore, existing algorithms predominantly rely on offline model training and parameter calibration; their adaptability and robustness in the presence of uncertainties—such as material variations and environmental disturbances—require further enhancement. At the system level, a key issue for future resolution is the deep integration of impact sensing information with functionalities such as residual life prediction of structures and maintenance decision support.

4. Research on Assessment Methods for SHM of Aeronautical Composite Materials

Machine learning, deep learning, and artificial intelligence technologies provide powerful data-driven capabilities and aptitude for capturing nonlinear relationships. Thus, they are increasingly emerging as cutting-edge research directions in damage identification. These methods enable the autonomous extraction of damage-sensitive features from complex datasets and the establishment of mapping relationships between input data and damage states, thereby facilitating efficient and accurate damage identification, localization, and quantification. Specifically, the damage identification process can be conceptualized as a four-step workflow: First, based on damage mechanics, extract degradation-relevant physical indicators from multi-source signals such as vibration and strain; second, employ techniques like recursive feature elimination combined with cross validation to select an optimal feature subset, verifying its causal consistency with physical laws governing macroscopic stiffness degradation and modal drift; third, during model training, explicitly embed constraints derived from conservation equations, boundary conditions, or degradation monotonicity into the loss function, compelling the model’s predictions to adhere to material-structural mechanics principles; fourth, utilize interpretability tools such as feature importance and partial dependence plots to perform post hoc analysis of the model’s decisions, revealing hidden relationships between latent variables and damage evolution. This workflow deeply integrates the high-dimensional modeling advantages of data-driven methods with the interpretability conferred by physical constraints, significantly enhancing the credibility and engineering practicality of damage identification results. With the deepening application of SHM systems in aviation, the efficient processing and intelligent analysis of massive monitoring data have become a research focus. The future development of health monitoring technology will increasingly rely on intelligent, automated inspection systems possessing high-precision and high-efficiency data processing capabilities. Machine learning, deep learning, and AI offer immense potential for the health monitoring and assessment of composite structures.

4.1. The Synergistic Evolution of Machine Learning and Deep Learning

In the field of SHM for composite materials, machine learning and deep learning have established complementary technological development pathways. Traditional machine learning algorithms demonstrate distinct value in scenarios with moderate feature dimensions and limited sample sizes. A comparative study by Mardanshahi et al. [

45] revealed that for guided wave-based matrix crack detection, the Support Vector Machine (SVM) achieved a 91.7% accuracy rate, significantly outperforming the Learning Vector Quantization Neural Network (LVQ-NN) and the Multilayer Perceptron Neural Network (MLP-NN). This underscores the advantage of traditional algorithms when addressing specific problems.

With the increasing scale and complexity of monitoring data, deep learning has achieved technological breakthroughs by leveraging its capacity for automated feature learning. Models such as Deep Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [

46] and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) [

47] utilize multi-level nonlinear transformations to autonomously extract physically meaningful damage features directly from raw data [

48,

49]. Bao et al. [

50] and Tang et al. [

51] developed anomaly detection methods based on computer vision and dual-stream CNN architectures, respectively, achieving accuracy rates of 87.0% and 93.5%. These results demonstrate the superior capability of deep learning in handling high-dimensional feature learning tasks.

4.2. Deep Integration of Optical Fiber Sensing and Intelligent Algorithms

The integration of optical fiber sensing technology with artificial intelligence is advancing damage monitoring towards greater precision and quantification. Xiong et al. [

52] developed a hybrid 1D CNN-LSTM framework that successfully captured the dynamic response characteristics of composite materials using a quasi-distributed FBG sensor network, achieving superior damage identification performance compared to traditional methods. In the realm of quantitative monitoring, the work by Zhao et al. [

53] represents a state-of-the-art advancement in this field. They utilize ABAQUS-FRANC3D co-simulation to obtain strain perception information, reconstructing the distorted FBG spectra via the transfer matrix method. Moreover, a CNN was also employed to establish a mapping relationship between damage features and crack length, ultimately achieving a monitoring accuracy with a mean absolute error of 0.52 mm. This “physical model + data-driven” methodology provides a novel approach for the quantitative assessment of damage in complex environments.

4.3. Key Technical Challenges and Development Bottlenecks

Despite their remarkable performance in laboratory settings, various intelligent algorithms face three major challenges in the transition to engineering practicality. The primary constraint is the bottleneck in data quality and quantity. For instance, while the Autonomous Cognitive Network (CAN) and Artificial Neural Network (ANN) employed by Yu et al. [

54] achieved a 95% probability of detection, their performance is heavily dependent on high-quality labeled data. Issues such as sample imbalance and the prohibitive cost of annotation in real-world engineering remain largely unresolved. A second prominent challenge is insufficient model generalization capability. As evidenced by Khan et al. [

55], their CNN-based hierarchical classification model attained 90.1% accuracy under specific conditions, but suffered significant performance degradation when material properties or environmental factors varied. This indicates a continued high sensitivity of current models to changes in data distribution. Finally, the tension between algorithmic complexity and real-time requirements is becoming increasingly acute. Tabian et al. [

56] utilized passive sensing combined with a CNN to achieve 95% localization accuracy.

4.4. Future Development Directions and Innovation Pathways

In light of current technological bottlenecks, intelligent damage identification technology for composite materials is evolving along three critical trends. First, the deep integration of physical mechanisms with data-driven approaches represents a key breakthrough direction. Embedding prior knowledge—such as material constitutive relations and damage evolution laws—into neural network architectures can simultaneously enhance model interpretability and improve reliability in extrapolation scenarios. Second, techniques for few-shot learning and transfer learning are garnering increased attention. Reducing dependence on large-scale annotated datasets through methods like meta-learning and domain adaptation is crucial for advancing practical deployment. Finally, collaborative edge intelligence and cloud computing is emerging as a dominant deployment paradigm. Leveraging techniques like model distillation and neural network pruning to achieve algorithmic lightweighting, combined with an edge-cloud collaborative computing architecture, effectively balances the inherent trade-off between computational accuracy and real-time performance. Breakthroughs in these technical directions will collectively propel composite material damage monitoring from “laboratory accuracy” towards “engineering practicality”, thereby providing more robust technological support for the safe O&M of aeronautical structures.

4.5. Typical Case Study of SHM Technology for Composite Wing Structures Based on FBG Sensing

The SHM technology for composite wing structures based on FBG sensing focuses on a carbon fiber-reinforced composite wing undergoing static loading, fatigue, and impact tests. By integrating strain threshold detection, machine learning classification, and fatigue cumulative damage models, the technology achieved damage localization, identification, and remaining life prediction. The system demonstrated a strain measurement accuracy of ±1 µε, a damage identification accuracy exceeding 90%, and a fatigue life prediction error of less than 15%. However, several limitations of this monitoring system remain: The discrete nature of FBG sensors inherently limits spatial resolution, making it difficult to detect subtle damage between sensor points; the strain-temperature cross-sensitivity increases the complexity of signal decoupling; the sensor embedding process may affect the structural integrity of the composite materials; and the aging of encapsulation materials during long-term service can degrade monitoring stability. Furthermore, algorithm training heavily relies on sample data from specific structures, resulting in insufficient generalization capability across different components. Additionally, high system costs and data processing complexity pose significant constraints for its large-scale engineering application.

5. Prospects for SHM of Aeronautical Composite Materials

With the synergistic advancement of advanced sensing technologies and intelligent analytical methods, the application scope of SHM technology in the field of aerospace engineering continues to expand. However, constrained by factors such as the anisotropy of composite materials and complex failure mechanisms, the large-scale engineering application of SHM technology in aviation urgently requires breakthroughs in the following key dimensions.

5.1. Intelligent Advancement of Structural Health Management Systems

Future research should transcend the current monitoring paradigm centered on discrete state perception. Its focus should be on developing a new generation of intelligent health management systems that integrate self-diagnosis, self-adaptation, and self-prediction capabilities. This entails a fundamental shift from a purely “data-driven” approach to a “physics-informed and data fusion-driven” framework. By embedding damage mechanics and wave propagation theory into deep learning architectures in the form of differentiable equations or soft/hard constraints, models can gain enhanced reasoning capability and extrapolation reliability, particularly in data-sparse regions. Concurrently, the development of online learning-based adaptive algorithms will enable systems to dynamically update model parameters using real-time monitoring data, thereby addressing material performance degradation and environmental changes. Ultimately, by establishing a full lifecycle digital twin, a closed-loop process—from remaining useful life prediction to condition-based maintenance decision-making—can be achieved. This will truly advance SHM systems toward intelligent systems endowed with self-awareness and evolutionary capabilities.

5.2. Enhancement of Operational Robustness for Health Monitoring

While current models perform excellently under standardized laboratory conditions, their generalization capability in real-world complex operational environments remains a bottleneck hindering engineering applications. Future research must focus on addressing the performance degradation of models under dynamic loads, varying environmental conditions, and uncertain boundary conditions, thereby achieving a transition from “static accuracy” to “dynamic robustness”. It is essential to develop physics-constrained hybrid modeling methods, incorporating constitutive relations and conservation laws as regularization terms into the loss function. This constrains the search space of data-driven models and ensures their solutions align more closely with physical principles. Furthermore, exploring domain adaptation and meta-learning techniques will enable models to leverage vast amounts of simulation data along with limited on-site annotated data. This approach allows for rapid adaptation to new flight states or structural configurations, reducing dependence on labeled datasets.

5.3. Development of Real-Time State Awareness and Predictive Capabilities for Aircraft

To meet the higher demands of next-generation aircraft for real-time safety and autonomous operational assurance, future research should focus on establishing a technical chain encompassing “high-fidelity sensing—intelligent modeling—and precise prediction”. At the sensing level, it is essential to develop a new generation of distributed optical fiber sensing systems with high sampling rates and strong resilience to interference (e.g., temperature variations and electromagnetic interference). Integrated with adaptive signal processing algorithms, such systems should be capable of automatically extracting robust damage-sensitive features from massive data streams. At the modeling level, a digital thread that deeply integrates sensor arrays with physics-based models must be constructed. This involves assimilating and calibrating real-time strain and vibration data with structural finite element models and damage evolution models, thereby forming a dynamically updated digital twin. This digital twin will provide real-time, forward-looking information support for flight control and maintenance decision-making.

6. Conclusions

This paper provides a systematic review of the research progress in SHM technologies for aeronautical composite materials. Although monitoring technologies, particularly those represented by optical fiber sensing, have achieved remarkable successes in both sensing mechanisms and typical applications, the transition from “monitoring” to “diagnosis” continues to face fundamental challenges. Currently, most assessment methods remain at the laboratory validation stage, exhibiting significant gaps in reliability, durability, and standardization under real-world complex operational conditions. Looking ahead, the maturation and successful deployment of this technology hinge on achieving breakthroughs in the following key areas: Firstly, there is an urgent need to develop interpretable artificial intelligence models that integrate physical principles, addressing the trust crisis in decision-making caused by the “black-box” nature of data-driven approaches. Secondly, it is imperative to overcome the technical bottlenecks associated with multi-physics sensor integration and design for extreme environment adaptability, ensuring the robustness of the monitoring system throughout its entire service life. Finally, concerted efforts should be directed towards building closed-loop autonomous systems that connect sensing data to O&M decisions. Ultimately, the health management of aeronautical composite structures will be propelled towards a new paradigm characterized by proactive early warning and autonomous decision-making.