Abstract

Fatigue-related ‘rotor crack’ can cause catastrophic failure if neglected. Thus, IoT-enabled AI-based predictive maintenance for fault detection and diagnosis is explored. Training and testing AI models under similar conditions improves their prediction performance. On variable speed machines, loss of performance occurs when the testing speed differs from the training speed. This research addresses significant performance loss issues using convolutional neural network (CNN)-based transfer learning models. The main causes of performance loss are domain shift, overfitting, data class imbalance, low fault data availability, and biassed prediction. All the above difficult issues make CNN-based fault prediction systems function badly under varying operating conditions. The proposed methodology addresses all domain adaptation challenges. The proposed methodology was tested by collecting vibration data from an experimental rotor system under varied operating conditions. The proposed methodology outperforms classical machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) models, overcoming the overfitting issue with optimised hyperparameters, achieving a prediction accuracy of 99.5%. Under varying operating conditions, it outperforms with a prediction accuracy of 93.2%, and in the ‘data class imbalanced’ scenario, the maximal transfer learning capability achieved was 84.4% with the highest F1-Score. Thus, CNN-based transfer learning enables industrial variable speed machines diagnose rotor crack flaws better than ML and DL models.

1. Introduction

In the 1970s, industrial machine failures, such as power turbine rotor fatigue failures in the USA, caused enormous asset, production, financial, and environmental losses [1,2,3,4,5]. Since then, extensive research has been conducted on the predictive maintenance of rotor fatigue crack failure to identify, locate, and notify about the failure of turbo machines. Traditionally, a crack is identified using vibration-based methods, which are sub-classified as signal- and model-based methods. The main issue with these traditional methods is that they are human-centric, i.e., they involve humans for the analysis and interpretation of hand-crafted features [6,7].

An extensive review of cracked rotor dynamics has been provided in [5], where the author identifies that Meyer J [8] established that the reduction of motion to linear equations with periodic coefficients, as established by many researchers, is merely an approximation. It also showed that the first work on using the energy release rate from the fracture mechanism was by Dimarogonas [9,10], which was further continued by Dimarogonas et al. [10]. Grabowski [11] developed a model with a transverse crack and concluded that the crack causes 1× and 2× of rotating-speed-related vibration. This is independent of the size and position of the imbalance; however, the phase in the response vibration is an important indicator of a crack. Additionally, a gaping crack causes exclusively 2× primary vibration. The same results were obtained by [5]. Muszynska [5,12] modelled local stiffness changes for a gaping crack with imbalance and gravity excitation and found 1× primary vibration increasing with the fault. She also discussed the causes of it, including initial asymmetry and damping of the rotor [5]. Papadopoulos [10] conducted an extensive survey to explore the model developed by Dimarogonas [13]. The contributions of Darpe et al. [14], Sekhar and Prabhu [15], Gounaris and Dimarogonas [16], Mayes and Davies [17], Bachschmid and Tanzi [18], and Chasalevris and Papadopoulos [19] are appreciated for their contributions to refining the crack identification model. Model-based methods require higher mathematical skills and expertise in rotor dynamics. In addition, analytical or numerical models can replicate cracked rotors; however, these methods are time-consuming and do not accurately predict or prevent catastrophic failure in a timely manner. This is because fatigue failures progress rapidly and are not detected by the existing machine protection systems used in these machines. Therefore, there is a need for an artificial-intelligence-based online and continuous monitoring system on turbo machinery to overcome the challenges faced by traditional signal- and model-based fault identification and diagnosis methods. As per Harvard Business Review [20], industries have started using AI technologies in predictive maintenance for industries. Market research reports indicate that the predictive maintenance industry is expected to grow at a rate exceeding USD 14.11 billion by 2028 [21].

Non-traditional predictive maintenance systems still need manual intervention to perform hand-crafted feature design, feature extraction/selection, model training [22], and pre-processing techniques. An inherent limitation of non-traditional predictive maintenance systems that employ machine learning and other methodologies is that they require appropriate domain knowledge for extracting crack-related features from the acquired data. Hence, automatic feature extraction capabilities were developed in a DL-based convolutional neural network (CNN). CNN has been explored in recent research works on machinery fault diagnosis, including bearings, gearboxes, motors, and rotor mass imbalance [23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. Zhao et al. [30] have developed a model to distinguish between shaft misalignment and cracks, which share similar dynamic vibration characteristics. The blade crack detection was explored by Shen et al. [31]. However, in industrial machines, rotor crack faults involve complex rotor dynamics, and research studies regarding rotor crack detection and diagnosis using CNN-based deep learning are scarce.

Researchers could establish CNN’s advantages in machinery fault diagnostics by manually tuning hyperparameters [23,24,25]. Due to the complexity of machinery fault diagnostic data, manually adjusting hyperparameters to improve prediction accuracy is difficult and time-consuming. As hyperparameters directly influence CNN performance, hyperparameter tuning has become a critical intrinsic problem that must be addressed for successful CNN performance. The present research addresses the inherent challenges of the CNN, such as overfitting [32] and hyperparameter optimisation [33]. Recently, the genetic algorithm (GA) has been explored in 1D applications, including biomedical, structural health monitoring, audio, and speech detection, among others [34]. The authors [29,35] have extended the research on CNN hyperparameter optimisation into machinery fault diagnosis. Among them, [29] carried out extensive research on the impact of hyperparameters and the position of the dropout layer on CNN’s performance. They have effectively addressed the hyperparameter optimisation issue using the GA and studied the performance of CNN models by positioning the dropout layer in various architectures. This research builds upon the work of [29] and further extends it by exploring domain-invariant feature learning.

The fault prediction algorithms face another challenge: biassed prediction due to data imbalance. This means the amount of healthy data is more than that of faulty data. Machinery diagnosis also suffers from the issue of the nature of the source data, which is multi-class and imbalanced [6]. Various researchers have addressed this issue in different fields [36,37]. Hence, to tackle class-imbalanced machinery fault data, the present research explores the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE), a method introduced by Chawla et al. [38], which has proven to be the best for data-level class balancing. The research study also observed that fault detection and diagnosis systems have been developed to automatically detect, diagnose, and assess the equipment fault severity; hence, the intelligent system/model/approach developed and trained on the test rig cannot be deployed directly on other similar equipment without considering the varying operational conditions. Conventional methods for intelligent crack fault diagnostics assume that the distribution of data in both the labelled source domain and the unlabelled target domain is identical. However, this might not always hold true in practical applications. It leads to a poor generalisation of the deployed machine learning algorithm, commonly known as the domain shift issue.

Recently, domain adaptation (DA) methods have been used to solve the issue of change in feature distribution, which is called domain shift. Zhang et al. [39] proposed a Convolution Neural Network with Training Interference (TICNN) model in which the CNN structure was developed with two training interferences. They developed it to diagnose bearing faults in signals that come from noisy environments. A robust fault diagnosis method has been proposed for the transfer learning technique of improved joint distribution adaptation (IJDA) to systematically synchronise both datasets’ marginal and conditional distributions [40]. Guo et al. [41] introduced a transfer learning method that increases domain identification error and decreases the probability distribution distance. This method was based on a 1D-CNN module. A deep CNN has been framed and implemented for gear fault detection [42]. A transfer learning framework based on a pre-trained CNN has been utilised in another research work to detect gear and bearing faults [43]. The literature review reveals that bearing faults [41,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51], gear faults [41,42,52,53,54,55,56], and common faults such as imbalance, misalignment, bearing, and gearbox faults have been explored using domain adaptation. The research study indicates that rotor crack faults have been a critical issue for industrial applications under varying operating speed conditions. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, the study reported on the use of domain adaptation techniques for crack fault detection and diagnosis using domain-invariant methods is scarce.

It is essential to address the gaps of fault complexity, data scarcity, class imbalance, and algorithmic optimisation to enhance fault detection processes in industrial applications. Therefore, this research explores rotor cracks by addressing the industrial challenges associated with the machinery fault diagnosis system. It investigates the use of CNN-based deep learning in the automated diagnosis of machinery faults, eliminating the need for human intervention in the feature-extraction process. Additionally, it addresses CNN’s inherent issues of hyperparameter optimisation and the model’s overfitting. Furthermore, a single fault diagnosis system adaptable to variable operating conditions is explored using the domain-invariant feature learning of Adversarial Discriminator Domain Adaptation (ADDA), and the limitations of the 1D-CNN are addressed within this framework. The present work proposes a domain-invariant feature learning architecture that addresses data class imbalance and hyperparameter issues for detecting and diagnosing rotor crack faults in variable-speed machines. Furthermore, its efficacy has been examined through various case studies.

The research paper is organised as follows. Section 2 covers the proposed methodology for diagnosing rotor crack faults in variable-speed machines. It provides details of the experimental rotor rig setup and data generation methods employed in the research. Section 3 focuses on the results and discusses the research outcomes. Finally, the paper concludes with the findings, benefits, and industrial contribution to machinery fault diagnosis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. ADDA (Adversarial Discriminator Domain Adaptation)

The challenge for existing machinery fault diagnosis methodologies is to apply past learning when new circumstances arise due to changes in operational conditions, which causes the domain shifting problem. The domain shift problem occurs when classifiers incorrectly assign attributes from the source domain to the target domain. The authors [57] reviewed various methods for feature learning to address this problem. Among them, domain-invariant feature learning has the potential to categorise features more effectively than other methods of domain adaptation [57]. In domain-invariant feature learning, Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) have recently gained the focus of research. They have the ability to quickly adapt the target domain to the specific conditions of a given source data by generating similar domain data. Discriminators and generators are used to train Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) in a competitive manner. Several adversarial GAN models have emerged to tackle domain discrepancy, which causes the domain shift problem.

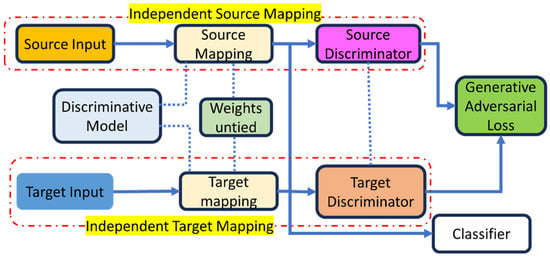

Tzeng et al. [58] made generalisations about adversarial models, and with these generalisations of adversarial techniques, three design choices are available: generative or discriminative base models, weight tying or untying, and adversarial learning objectives. Furthermore, the authors [58] used a discriminative model with untied weights and the typical GAN loss, as illustrated in Figure 1. The next step is to tune the model to fit the target domain. The goal of adversarial adaptive approaches [58] is to minimise the difference between the distributions of source and target mappings, and , by regularising the learning process of these mappings.

Figure 1.

ADDA framework [59].

Research [58] demonstrates that the inverted label GAN loss achieves the following optimisation. and are source data and labels and are derived from a source domain distribution , while is a target distribution with no label observations. The aim is to learn a classifier and target representation that can accurately classify target data into one of K categories at test time, even in the absence of in-domain annotations. The target cannot be directly supervised; thus, domain adaptation trains a source representation mapping, , and a source classifier, , then adapts that model for the target domain. This can be carried out in adversarial adaptive learning by reducing the distribution gap between the source and target mapping of ) & thus, the target classifier can be eliminated, such as = = .

The function is a discriminator’s standard classification loss, The classifier loss, and = = .

″D″ is the domain discriminator; it is optimised through standard supervised loss, , and the labels show their origin domain:

Without weight sharing, the target domain cannot access labels, which means that the target model may quickly reach a degenerate solution due to improper training and initialisation. Therefore, to train adversarially, one must alter the source model and then use it to initialise the target representation space.

2.2. Phase 1—Data Generation and Pre-Processing

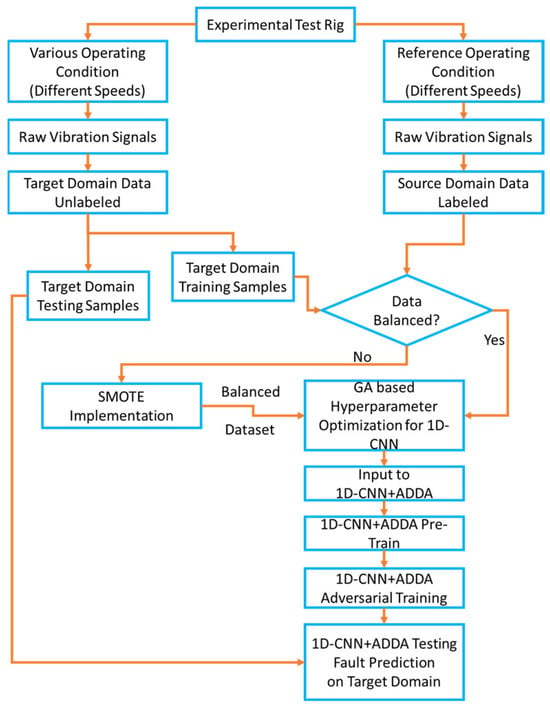

The flow chart of the proposed methodology is shown in Figure 2, and technical details are shown in Figure 3a,b. In the first phase, data generation and pre-processing were carried out. In the second phase, adversarial learning was implemented, and in the third phase, testing of the target domain data was performed.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of the proposed methodology.

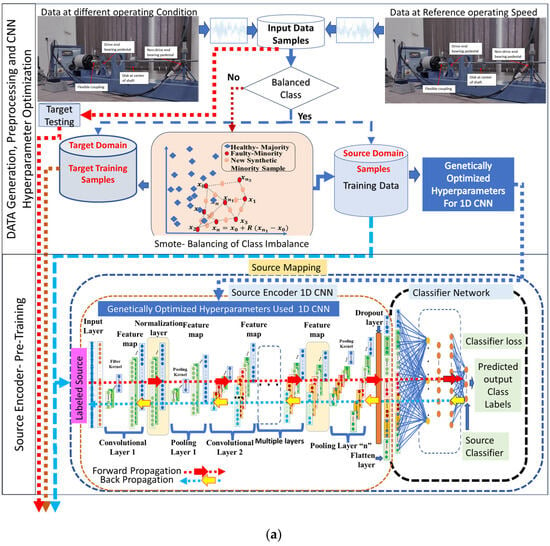

Figure 3.

(a) Data generation & Pretraining of Proposed methodology. (b) Adversarial Adaptation & Testing of Proposed methodology.

2.2.1. Generating Rotor Rig Data and Pre-Processing

Acceleration sensors acquire rotor health data from the experimental test setup, as shown in Figure 3a,b. The generated data are further utilised according to the proposed methodology. A reference source domain has utilised one set of operational speed data samples, while the other set of speed data is considered samples for the target domain. In order to assess class balance, the allocation of samples in the source and target datasets was analysed. Once the class is balanced, the hyperparameters are fine-tuned by the evolutionary algorithm. To correct the issue of data class imbalance, SMOTE is applied to data samples from either the source or target domains. Once the samples have been balanced, the hyperparameters are optimised, as demonstrated in Figure 3a,b.

2.2.2. GA-Based Hyper Parameter Optimisation

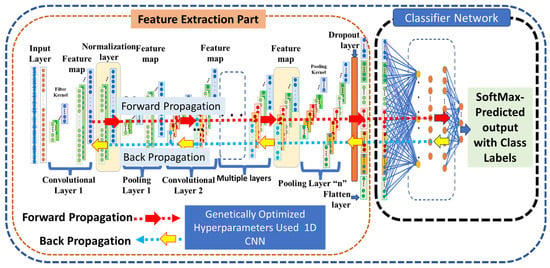

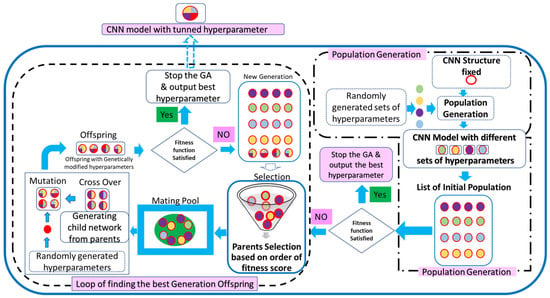

The genetic algorithm tunes 1D-CNN hyperparameters directly, utilising the time waveform as input data. Figure 4 illustrates the 1D-CNN, which incorporates convolutional, batch normalisation, pooling, and dropout layers.

Figure 4.

The 1D-CNN general architecture.

The CNN hyperparameters, including the dropout layer in the final feature-extraction layer [29], have been genetically optimised to maximise the performance of 1D-CNN, as shown in Figure 5. The 1D-CNN design consists of 5 convolutional layers, 2 hidden layers, and a sigmoid classifier.

Figure 5.

GA-based hyperparameter optimisation 1D-CNN [27].

Figure 5 illustrates how GA optimisation creates 1D-CNN populations using randomly generated hyperparameters. After that, accuracy is computed for every output forecast, and the population record is arranged from high to low based on fitness value. To maintain population diversity and enhance the genetic algorithm’s convergence with newly hyperparameterised settings that have been fitness-tested, randomly generated hyperparameters have been introduced to facilitate mutation and the creation of new offspring. The genetic algorithm stops when the forecasted accuracy equals the fitness score of the new offspring and provides the optimised 1D-CNN hyperparameters. The genetic algorithm terminates generation and preserves the hyperparameters if the fitness score is at a maximum; otherwise, evolution continues until convergence. Figure 3a,b show how optimised hyperparameters are used in the second and third phases of the proposed methodology to maximise prediction accuracy.

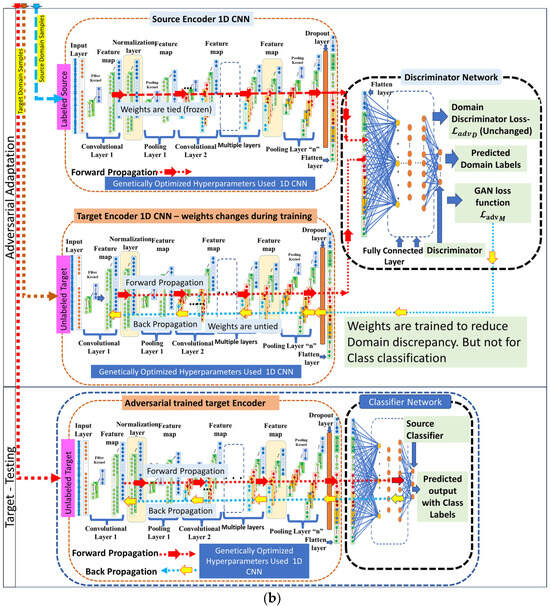

2.3. Phase 2—Adversarial Learning Implementation

Figure 3b illustrates the second phase of the proposed process, which involves pre-training the source encoder and performing adversarial learning. The ADDA receives data from both the source and target domains for the respective encoders. Initially, the source encoder is pre-trained using a source classifier network to classify the data. Furthermore, a discriminator network is employed to mitigate domain discrepancies through adversarial learning. Genetically optimised 1D-CNN hyperparameters extract domain-invariant features, which are a part of the ADDA’s architecture.

2.3.1. Training of Task Network with Source Encoder

The classifier network is trained to classify the labelled source domain data during the task network’s training, utilising the source encoder domain adaptation phase. Adjusting the encoder weights may decrease the classifier loss and boost the classifier’s performance via backpropagation.

2.3.2. Adversarial Learning Process

In adversarial learning, the target encoder competes with a discriminator network to classify the data from both the source and target domains. The source encoder’s weights are fixed, while the target encoder alters weights depending on the discriminator GAN loss. The discriminator identifies domain-related features by adjusting the weights of the target encoder based on the discriminator’s GAN loss. Thus, the fault classification features are preserved, and only the domain shift-related features, which are related to varying operating conditions, are identified and equalised. This enables the model to predict the fault under any operational condition. The target encoder weighs the optimisation training process to decrease domain shift is depicted in Figure 3a,b.

2.4. Phase 3—Testing of Target Domain

The source classifier and a learned target encoder have been used to test target domain samples. Employing ADDA with GO-1D-CNN enables the optimisation of GAN loss for domain discrepancy, which decreases domain shift by capturing domain-invariant features. Further usage of an unaltered classifier ensures classification capabilities are not affected for both source and target domain samples. In the proposed framework, SMOTE is not applied to the raw test data of the target domain. It is only used during the training stage to address the sample scarcity and class imbalance that occur when constructing the feature space. In ADDA, domain alignment is performed at the representation level, where the target encoder learns to map target samples into a feature distribution that is consistent with the source encoder. SMOTE is therefore applied to the target feature embeddings during training, not on unseen target test samples. This enables us to provide a more balanced representation to the discriminator and to prevent biassed decision boundaries while preserving the natural distribution of real target samples in testing. Table 1 and Table 2 present the source and target domain data, as well as the operating speeds at which performance is evaluated.

Table 1.

Data Generated from Experimental Test Rig.

Table 2.

Operating speeds of the rotor rig used for the DA task.

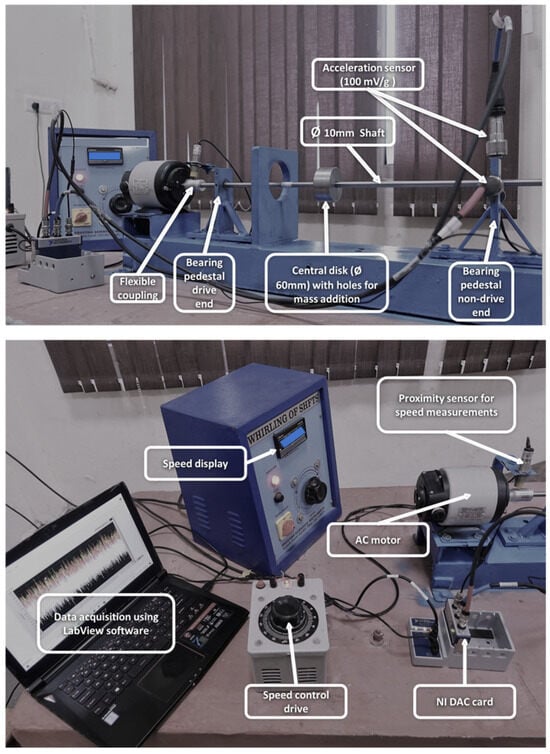

2.5. Experimental Setup

The experimental setup is shown in Figure 6. The rotor rig experimental setup comprises the rotor assembly, which is equipped with a motor speed controller and a drive motor. The rotor assembly has acceleration and vibration sensors designed to monitor vibration. The experimental setup comprises a motor with a power of 1/6 hp and a rotor system consisting of a shaft with a 10 mm diameter, a disc installed in the middle, and ball bearings 500 mm apart supporting the shaft’s ends. Accelerometers that record data are mounted on the bearing housing, and the flexible coupling is used to connect the motor and shaft. The disc has four holes spaced at right angles to each other. An acceleration sensor with a sensitivity of 100 mV/g is used to collect the vibration time waveform, which is then processed with the NI data card 9230. A 50 kHz vibration time waveform is recorded for two seconds, and many vibration time waveform signals are recorded at 1500 RPM, 1750 RPM, and 2000 RPM. The collected data is then divided into 2000 data points per sample.

Figure 6.

The experimental setup.

The cracks were made using wire cutting, with a 0.2 mm width, and their depths were varied from 1 mm to 5 mm. This range was chosen to reflect practical levels of rotor fault severity. In total, six health states were considered: one healthy shaft with no crack and five cracked shafts with depths from 1 mm up to 5 mm. These crack levels are commonly used in vibration-based condition monitoring studies and provide fault signatures that are well-suited for further classification and adaptation. For all six health statuses, 600 samples are collected, 100 samples for each class/condition. For the data class-balanced condition, 600 samples were collected for each domain, which includes both the source and target domains. However, linear class imbalance has been implemented for the class-imbalanced condition, resulting in the collection of 285 samples for each domain, which includes both the source and target domains. Table 1 presents the samples used in the source and target domains for both balanced and imbalanced data class conditions. A similar procedure is repeated to generate target domain data, as illustrated in Table 2.

The frequency spectrum and time waveform details have been extracted for machine learning algorithms’ training and testing data. The acceleration time waveform has been integrated to derive velocity and displacement data. A total of 108 features have been extracted from displacement, velocity, and acceleration spectra and time waveforms, and 36 features have been extracted from each measurement. From the research [6,59], the features considered are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3.

Acceleration, velocity, and displacement features used in machine learning algorithms [6,59].

3. Results and Discussion

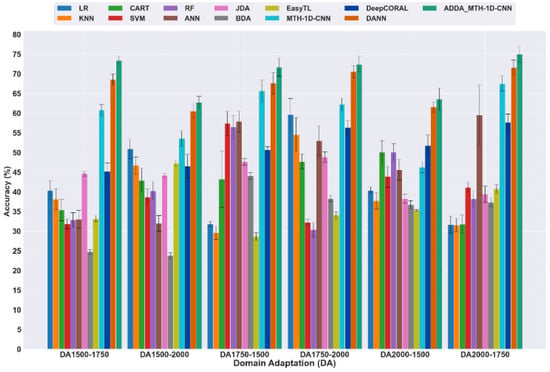

To investigate the necessity of domain adaptation capabilities when dealing with varying operating conditions, as well as other problems inherent to CNN, this section presents three distinct studies analysing the experimental data. The performance evaluation is conducted by comparing machine learning (ML), deep learning (DL), traditional transfer learning algorithms, and domain-invariant feature learning approaches. The ML algorithms used in this study include Logistic Regression (LR), K-Nearest Neighbour (KNN), Classification and Regression Tree (CART), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forests (RF), and Artificial Neural Network (ANN). The DL models considered are a manually tuned one-dimensional convolutional neural network (MTH-1D-CNN) and a genetic-algorithm-optimised 1D-CNN (GO-1D-CNN). The traditional transfer learning methods evaluated comprise Joint Distribution Adaptation (JDA), Balanced Distribution Adaptation (BDA), and Easy Transfer Learning (EasyTL). Finally, the domain-invariant feature learning approaches include Domain-Adversarial Neural Networks (DANN), Deep Correlation Alignment (DeepCORAL), and the proposed methodology. By comparing different algorithms, the effectiveness of the proposed methodology for rotor crack detection and diagnostic systems in industrial machines is evaluated.

3.1. Study 1: Evaluating Performance of ADDA and 1D-CNN with Manually Tuned Hyperparameters

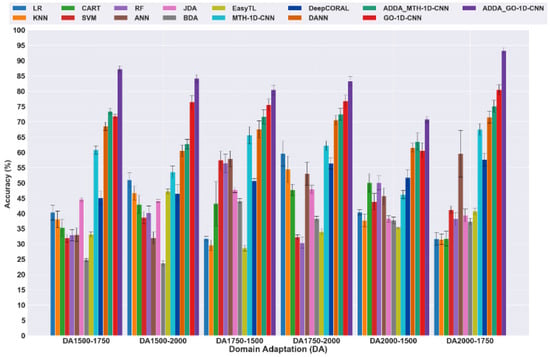

Study 1 evaluates the proposed methodology’s variable-speed rotor crack detection and diagnosis capability. As shown in Figure 3a,b, Adversarial Discriminative Domain Adaptation is utilised on different operating speeds to address the domain shift problem. Six conventional machine learning methods and a 1D-CNN model have been evaluated for domain adaptation by directly utilising the trained model on a reference speed against different operating speeds, as shown in Table 2. Figure 7 shows that the DL (1D-CNN) algorithm outperforms six ML and three traditional transfer learning algorithms in domain adaptation (DA) tasks.

Figure 7.

DA prediction accuracy comparison of ML, DL, and ADDA with manually tuned hyperparameters for rotor crack fault diagnosis.

Test results of MTH-1D-CNN, which is a 1D-CNN with manually tuned hyperparameters, indicate a 67.5% accuracy prediction for domain adaptation tasks of DA 2000-1750 (source training data collected at 2000 RPM, tested on target data collected at 1750 RPM). Test results indicate that MTH-1D-CNN performs better than traditional domain adaptation algorithms (JDA, BDA, EasyTL) in terms of prediction performance; however, it is found that DANN and ADDA outperform the manually tuned 1D CNN (MTH-1D-CNN) in the DA task. Furthermore, ADDA_MTH-1D-CNN, which is ADDA within its architecture with a 1D-CNN and manually tuned hyperparameters, outperforms MTH-1D-CNN and DANN, achieving a maximum prediction accuracy of 75%. The test results show that ADDA increases prediction accuracy by addressing the ‘domain shift’ problem. However, addressing concerns about 1D-CNN performance, such as hyperparameter tuning and overfitting, may improve ADDA’s prediction performance, which is a crucial research need. Additionally, ADDA’s performance compared to JDA, BDA, EasyTL, DeepCORAl, and DANN demonstrates that ADDA’s adversarial GAN-loss-based domain adaptation outperforms statistical distribution, non-parametric domain adaptation, and other domain-invariant feature-based learning methods.

3.2. Study 2: Evaluating the Efficacy of Proposed Methodology for Balanced Data for Multi-Class Balanced Application

Study 1 demonstrates the need for domain adaptation in industrial machinery fault diagnosis systems. The test results of the ADDA in Study 1 indicate a decrease in domain discrepancy. However, the manually tuned hyperparameters of the 1D-CNN exhibit low prediction accuracy; further manual tuning of the CNN hyperparameters requires significant effort, time, and domain expertise. In order to improve the efficiency of the domain adaptation algorithm in Study 2, hyperparameter optimisation based on GA is implemented. The hyperparameters tuned via GA, as shown in Figure 5, are displayed in Table 4. Further, the overfitting issue is addressed by adapting the research outcome of adding a dropout layer at the end of the feature extraction part of the 1D-CNN. The epochs and batch size were optimised with other parameters and obtained as 61 epochs and 12 batch size, respectively. Other parameters are shown in Table 4 below.

Table 4.

GA-optimised hyperparameters for GO-1D-CN.

For the GO-1D-CNN training and testing on the same domain, prediction performance reached 99.5% (2000 RPM—source domain). However, once domain adaptation, that is, training on the reference speed (source domain) and testing on another speed (target domain), is carried out, the test results indicate a performance loss of up to 19%, with a prediction accuracy of 80.5%, as shown in Figure 8. Furthermore, the 1D CNN with GA-optimised hyperparameters (GO-1D-CNN) outperforms machine learning models, manually tuned models, and traditional transfer learning algorithms (JDA, BDA, EasyTL) with 80.5% prediction accuracy, utilising prior knowledge.

Figure 8.

DA prediction accuracy comparison of ML, DL, and ADDA with GA-optimised hyperparameters for rotor crack fault diagnosis.

ADDA with genetically optimised hyperparameters and GO-1D-CN architecture outperforms GO-1D-CNN and ADDA (MTH_1D-CNN) with manually tuned hyperparameters by 93.22% in prediction accuracy. This shows that hyperparameter tuning is critical for GO-1D-CNN’s feature extraction and classification performance. The results of Study 2 demonstrate that ADDA reduces domain discrepancy, and GO-1D-CNN achieves a performance of 93.22% in feature extraction and domain characteristic classification. In Figure 3a,b, which depict the ADDA framework, domain-invariant features are trained to reduce the loss of domain discrepancy without affecting the classification loss of the source domain. This enables the target domain to align with the source domain, preserving classification capabilities. ADDA with the GO-1D-CNN architecture surpasses ML, statistical, and non-parametric transfer learning algorithms, such as JDA, BDA, and EasyTL. Furthermore, ADDA outperforms other domain-invariant feature learning algorithms, such as DeepCORAL and DANN, in terms of more precise prediction of rotor crack faults across varying machine speeds.

Validation for Adversarial Domain Adaptation

Validation details are provided in this section for Phase 1 at 2000 RPM, Phase 2 DA learning from 2000 to 1500 RPM, and the validation for Phase 3.

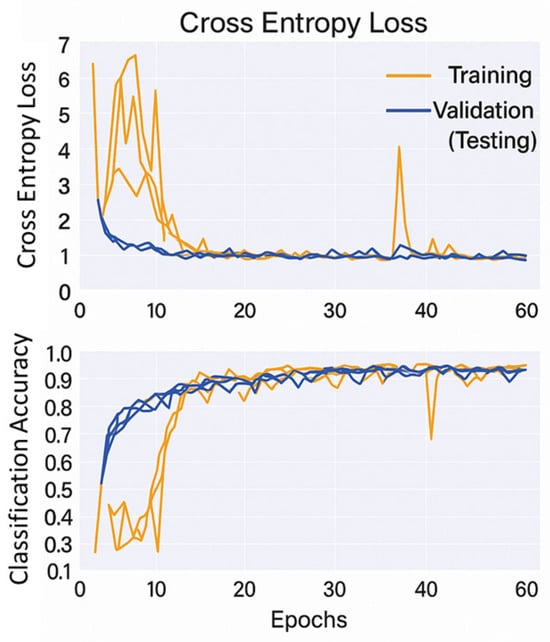

- Phase 1—Source Encoder pre-training

The primary objective is to attain a maximum level of classification accuracy in this phase. Optimising hyperparameters using genetic algorithms is crucial for achieving the most accurate predictions with 1D-CNN. Furthermore, CNN’s overfitting concerns are effectively addressed by positioning dropout as the last layer of the CNN architecture. The research outcome of GA optimisation has been implemented in the CNN architecture, and the source encoder has been pre-trained. The pre-trained model undergoes k-fold validation, and the test results are shown in Figure 9. Five-fold cross-validation with 61 epochs ensures that the cross-entropy loss decreases and classification accuracy increases with each epoch.

Figure 9.

Validation of the ADDA source encoder pre-training performance for rotor crack fault diagnosis at 2000 RPM.

- 2.

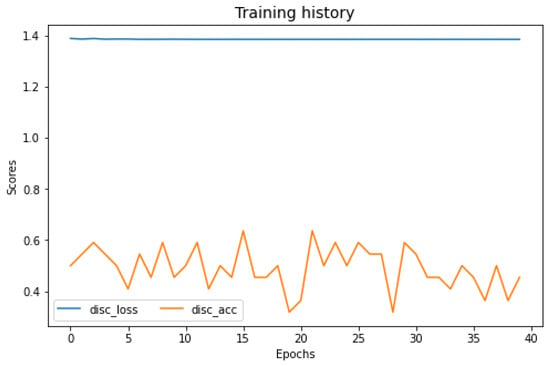

- Phase 2—Adversarial Learning for Target Encoder Training and GAN loss minimisation of the discriminator

An adversarial learning setup involves labelling data as zero (‘0’) for the source domain data and one (‘1’) for the target domain data. The discriminator network then makes an effort to determine the data’s origin domain. A higher loss in the domain is indicative of a properly recognised domain. So, the ADDA algorithm changes the weights of the target encoder to lower the GAN loss, but the source encoder’s weights remain unchanged. Reduced domain discrepancy and optimised target encoder weights are outcomes of a discriminator network that shows a 50% probability of source and target domain confusion, which in turn reduces GAN loss. Figure 10 shows the GAN loss minimisation of the ADDA discriminator after 40 epochs.

Figure 10.

Performance of adversarial learning of the discriminator at DA-2000-1750.

- 3.

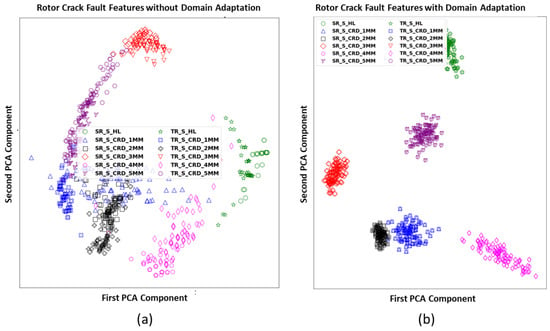

- Phase 2—Visualisation of Features

The learned features have been visualised using PCA. As shown in the architecture of the CNN (Figure 4), features are extracted using CNN layers and classified through the Softmax layer. Visualising extracted CNN features gains importance in assessing the efficacy and performance of the proposed methodology, both with and without domain adaptation. PCA has been used to visualise learned features in 2-D from high-dimensional data. Figure 11a,b show the extracted features without domain adaptation (GO-1D-CNN) and with domain adaptation (ADDA_GO-1D-CNN). Figure 11a indicates that the 1D-CNN clusters have similar characteristics of rotor crack severity conditions without domain adaptation. Additionally, the clustered features are observed to be distinct in both the source domain and the target domain. Primarily, both the target domain and the source domain are segregated without interference for multiple rotor crack fault severity (multi-class); GO-1D-CNN can efficiently predict if it is trained independently for each speed.

Figure 11.

Visualisation of features from final layers of (a) GO-1D-CNN and (b) ADDA_GO-1D-CNN.

Furthermore, it is also observed that certain classes from the source domain overlap with those in the target domain. This situation requires domain adaptation for equipment fault diagnostics. The extracted features from the last layers of the CNN in Figure 11b are used to study the proposed methodology’s domain adaptation capabilities.

No overlap is found between the healthy shaft and varying depths of rotor crack with severity levels 1 and 5 (Table 1). Minor boundary sharing between rotor crack severity levels 1 and 2 of the target domain features, and the source domain clearly explains the reason for the proposed methodology’s highest performance, which reaches only 93.22%. Test findings show that ADDA_GO-1D-CNN predicts better than ML and GO-1D-CNN algorithms, as it minimises data domain differences using past learning.

3.3. Study 3: Performance Analysis of Proposed Methodology for Class Imbalance Data Application

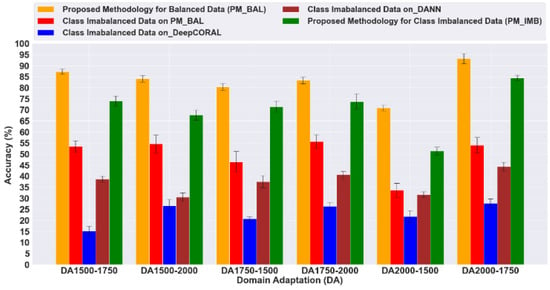

Studies 1 and 2 previously addressed the domain shift problem and the inherent challenges of CNNs, that is, the optimisation of hyperparameters and the overfitting issue. Study 3 furthermore explores the real-world scenario of the fault data availability. The available machinery fault data are multi-class-imbalanced, meaning that healthy data availability is more prevalent, and data availability decreases as fault severity increases. For class-imbalanced data, to overcome the biassed classification nature of machine learning and deep learning models, as shown in Figure 8, the synthetic minority oversampling technique (SMOTE) has been explored within our proposed methodology in Study 3. Study 3 becomes more complex in nature as all performance-related challenges are addressed together, such as CNN’s overfitting and hyperparameter tuning issues, domain shift issues, the complex nature of faults, and data scarcity. As demonstrated in Table 1, the imbalanced data utilised for training the source domain involves decreasing the sample size from a state of good health to various levels of fault severities. Target domain samples, on the other hand, have been reduced from the largest examples with the most severe faults to healthy states. Two different data availability conditions are explored, and the test results are presented in Figure 12 for ‘data class-balanced’ and ‘data class imbalanced’ scenarios.

Figure 12.

Prediction Performance on Imbalanced Class Data—Comparison of Different DA Algorithms against the Proposed Methodology for Class Imbalance Data.

Test results of domain-invariant feature learning-based algorithms, such as DeepCORAL and DANN, have been found to perform poorly in cases of data class imbalance. Specifically, DANN could not predict more than 44%; this is due to data scarcity that causes class imbalance during training for both DANN and DeepCORAL. Furthermore, the proposed methodology, i.e., ADDA_GO-1D-CNN, performs well with ‘data class balanced’ datasets, achieving an accuracy of up to 93.22%. When encountering ‘data class imbalance’, it loses up to 54% of its performance in the domain adaptation task, specifically from 2000 RPM to 1750 RPM. The domain adaptation performance at different operating speed conditions indicates a loss in performance due to ‘data class imbalanced.’ The loss of performance of up to 39.2% indicates that even deep learning models, which are believed to perform very well, can fail due to imbalanced class data. This is a real challenge that the industry faces today, and it must be addressed to implement Industry 4.0 through an automatic fault prediction system. The proposed methodology, which addresses various challenges, including overfitting, difficulties with hyperparameter tuning, domain shift, complex rotor crack with varying severity, and data scarcity, achieves a performance improvement of 84.4%. There is an increase in effectiveness of up to 30.4% with the proposed methodology. Additionally, the proposed methodology outperforms all other domain adaptation algorithms, including DeepCORAl and DANN.

Performance Validation of Proposed Methodology on Class Imbalanced Data for DA Task

The test results are verified using the F1-Score metric, specifically designed for use with class-imbalanced data. Table 5 presents the test results for F1-Score, recall, precision, and accuracy across various domain adaptation tasks. This F1-Score, being a harmonic mean, considers both precision and recall in its calculation. Table 5 shows Study 3 test results, indicating that the proposed methodology for ‘class imbalanced data’ achieves the highest F1-Score for the domain adaptation task of 2000 RPM to 1750 RPM (DA 2000-1750) and gained the highest prediction. Thus, the proposed methodology outperforms even with ‘data class imbalance’ in machinery fault diagnosis for variable- speed machine operation conditions.

Table 5.

Performance Validation for SMOTE Implemented on Multi-class Imbalanced Data for DA Task.

4. Conclusions

This study utilises AI to address predictive maintenance issues related to rotor crack fault identification and diagnosis. Performance loss happens due to CNN’s hyperparameter optimisation and overfitting, domain shift, fault complexity, and data class imbalance. The proposed methodology effectively addresses these issues in prediction performance and successfully detects and diagnoses rotor crack faults in industrial machines under various operating conditions. Case Study 1 indicates that ML and DL lose prediction capabilities as operating conditions change. Case Study 2 addresses the hyperparameter tuning and overfitting issues of 1D-CNN. The proposed technique achieves up to 99.5% accuracy under similar conditions. At various operating speeds, the prediction performance is 93.22%. The study indicates that manually tuning the 1D-CNN architecture’s hyperparameters is less accurate than genetic-algorithm-based optimisation. PCA was used to study the characteristics of the last 1D-CNN layer with and without the domain adaptation task.

Domain adaptation reduces domain discrepancy, improving performance. Study 3 examined how ‘class unbalanced data’ affects performance. On an imbalanced dataset, the proposed methodology improves prediction accuracy from 30.4% to 84.4%. Fault predictions for ‘class unbalanced data’ are also evaluated using the F1-Score, the harmonic mean of recall and precision. Benchmarking against various other domain adaptation algorithms validates the work’s efficacy. The methodology demonstrated stable adaptation to varying operating conditions within the tested crack range of 1–5 mm, as it learns changes in vibration response associated with fault progression rather than relying on a specific defect magnitude. Therefore, the proposed approach is not constrained to this range and can be extended to shallower cracks below 1 mm, provided that representative vibration data are available for model training and validation. The present work considers open cracks generated by wire cutting, but the same framework may be extended to different crack types in future studies by acquiring vibration responses that reflect those geometries. Furthermore, the methodology may be extended to crack localisation by employing distributed sensing or multi-position measurements in future investigations. The outcome of the proposed methodology on experimental data demonstrates potential performance improvement, which effectively helps to create an AI-based predictive maintenance programme for diagnosing rotor crack faults of industrial machines under varying operating conditions.

Author Contributions

S.R. is responsible for methodology, validation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, visualisation. S.S. is responsible for software, supervision, reviewing and editing. A.P. is responsible for supervision and review. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author, the data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Schmerling, J.; Hammon, J. Investigation of the Tennessee Valley Authority Gallatin Unit No. 2 Turbine Rotor Burst. Proc. Am. Power Conf. 1976, 38, 5274445. [Google Scholar]

- Haas, H. Großschäden durch Turbinen-oder Generatorläufer, entstanden im Bereich bis zur Schleuderdrehzahl. Der Maschinenschaden 1977, 50, 195–204. [Google Scholar]

- Jack, A.; Paterson, A. Cracking in 500 MW LP rotor shafts. In The Influence of Environment on Fatigue; I Mech E Conference Publications: London, UK, 1977; pp. 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Greco, J.; Agnew, J.R.; Erhardt, K.; Bertilsson, J.E.; Stys, Z.S. Cumberland Steam Plant: Cracked IP rotor coupling of Unit 2. Proc. Am. Power Conf. 1978, 40, 5857831. [Google Scholar]

- Wauer, J. On the dynamics of cracked rotors: A literature survey. Appl. Mech. Rev. 1990, 43, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopalan, S.; Singh, J.; Purohit, A. VMD-Based Ensembled SMOTEBoost for Imbalanced Multi-class Rotor Mass Imbalance Fault Detection and Diagnosis Under Industrial Noise. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 2023, 12, 1457–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopalan, S.; Purohit, A.; Singh, J. A Systematic Review of Rotor Unbalance Diagnosis in Rotating Machinery Based on Machine Learning Algorithms. In International Conference on Vibration Engineering and Technology of Machinery; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J. Zum Schwingungsverhalten einer Lavalwelle mit angerissenem Wellenquerschnitt. Doctoral Dissertation, Hochschule d. Bundeswehr, Fachbereich Maschinenbau, Neubiberg, Deutschland, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Dimarogonas, A. Dynamic Response of Cracked Rotors; General Electric Co.: Schenectady, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Dimarogonas, A.D.; Paipetis, S.A.; Chondros, T.G. Analytical Methods in Rotor Dynamics; Springer Science & Business Media: Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski, B. The vibrational behavior of a turbine rotor containing a transverse crack. J. Mech. Des. 1980, 102, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muszynska, A. Shaft crack detection. In Proceedings of the 7th Machinery Dynamics Seminar, Virginia Beach, VA, USA, 11–13 October 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Dimarogonas, A.D. Vibration of cracked structures: A state of the art review. Eng. Fract. Mech. 1996, 55, 831–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darpe, A.K.; Gupta, K.; Chawla, A. Coupled bending, longitudinal and torsional vibrations of a cracked rotor. J. Sound Vib. 2004, 269, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhar, A.; Prabhu, B. Transient analysis of a cracked rotor passing through critical speed. J. Sound Vib. 1994, 173, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gounaris, G.; Dimarogonas, A. A finite element of a cracked prismatic beam for structural analysis. Comput. Struct. 1988, 28, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayes, I.; Davies, W. Analysis of the response of a multi-rotor-bearing system containing a transverse crack in a rotor. J. Vib. Acoust. Stress Reliab. Des. 1984, 106, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachschmid, N.; Tanzi, E. Deflections and strains in cracked shafts due to rotating loads: A numerical and experimental analysis. Int. J. Rotating Mach. 2004, 10, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chasalevris, A.C.; Papadopoulos, C.A. Identification of multiple cracks in beams under bending. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2006, 20, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DalleMule, L.; Davenport, T.H. What’s Your Data Strategy? [STRATEGY] 2017 May–June Harvard Business Review. pp. 112–121. Available online: https://hbr.org/2017/05/whats-your-data-strategy (accessed on 20 June 2019).

- Lueth, K.L. Asset Performance & Predictive Maintenance Market Report 2023–2028. Available online: https://iot-analytics.com/product/predictive-maintenance-asset-performance-market-report-2023-2028/#wpcf7-f153326-o1 (accessed on 20 June 2019).

- Zhao, R.; Yan, R.; Chen, Z.; Mao, K.; Wang, P.; Gao, R.X. Deep learning and its applications to machine health monitoring. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2019, 115, 213–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Yang, B.; Jiang, X.; Jia, F.; Li, N.; Nandi, A.K. Applications of machine learning to machine fault diagnosis: A review and roadmap. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2020, 138, 106587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Zhao, M.; Lin, J.; Liang, K. A comprehensive review on convolutional neural network in machine fault diagnosis. Neurocomputing 2020, 417, 36–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Azamfar, M.; Li, F.; Lee, J. A systematic review of machine learning algorithms for prognostics and health management of rolling element bearings: Fundamentals, concepts and applications. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2020, 32, 012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eren, L.; Ince, T.; Kiranyaz, S. A generic intelligent bearing fault diagnosis system using compact adaptive 1D CNN classifier. J. Signal Process. Syst. 2019, 91, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Li, C.; Sanchez, R.-V. Gearbox fault identification and classification with convolutional neural networks. Shock. Vib. 2015, 2015, 390134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Rajagopalan, S.; Purohit, A.; Singh, J. Variable Dropout One-Dimensional CNN for Vibration-Based Shaft Unbalance Detection in Industrial Machinery. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 2022, 11, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopalan, S.; Singh, J.; Purohit, A. Performance analysis of genetically optimized 1D-convolutional neural network architecture for rotor system fault detection and diagnosis. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E J. Process Mech. Eng. 2024, 09544089241235707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Hua, C.; Wang, D.; Dong, D. Fault Diagnosis of Shaft Misalignment and Crack in Rotor System Based on MI-CNN. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Damage Assessment of Structures, Porto, Portugal, 9–10 July 2020; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Song, D.; Ma, T.; Xu, F. Blade crack detection based on domain adaptation and autoencoder of multidimensional vibro-acoustic feature fusion. Struct. Health Monit. 2023, 22, 3498–3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, N.; Hinton, G.; Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Salakhutdinov, R. Dropout: A simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2014, 15, 1929–1958. [Google Scholar]

- Wistuba, M.; Schilling, N.; Schmidt-Thieme, L. Hyperparameter optimization machines. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Data Science and Advanced Analytics (DSAA), Montreal, QC, Canada, 17–19 October 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kiranyaz, S.; Avci, O.; Abdeljaber, O.; Ince, T.; Gabbouj, M.; Inman, D.J. 1D convolutional neural networks and applications: A survey. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2021, 151, 107398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Hua, C.; Dong, D.; Ouyang, H. A Novel Method for Identifying Crack and Shaft Misalignment Faults in Rotor Systems under Noisy Environments Based on CNN. Sensors 2019, 19, 5158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chawla, N.V.; Japkowicz, N.; Kotcz, A. Special issue on learning from imbalanced data sets. ACM SIGKDD Explor. Newsl. 2004, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Minku, L.L.; Yao, X. A learning framework for online class imbalance learning. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Symposium on Computational Intelligence and Ensemble Learning (CIEL), Singapore, 16–19 April 2013; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: Synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2002, 16, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, C.; Peng, G.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z. A deep convolutional neural network with new training methods for bearing fault diagnosis under noisy environment and different working load. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2018, 100, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, W.; Li, S.; Yi, P.; Zhang, K. A novel transfer learning method for robust fault diagnosis of rotating machines under variable working conditions. Measurement 2019, 138, 514–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Lei, Y.; Xing, S.; Yan, T.; Li, N. Deep convolutional transfer learning network: A new method for intelligent fault diagnosis of machines with unlabeled data. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2018, 66, 7316–7325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Azamfar, M.; Ainapure, A.N.; Lee, J. Deep learning based cross domain adaptation for gearbox fault diagnosis under variable speed conditions. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2020, 31, 055601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.; Liu, C.; Yang, W.; Jiang, D. Learning transferable features in deep convolutional neural networks for diagnosing unseen machine conditions. ISA Trans. 2019, 93, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Peng, G.; Li, C.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z. A new deep learning model for fault diagnosis with good anti-noise and domain adaptation ability on raw vibration signals. Sensors 2017, 17, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Chen, C.; Yan, R.; Gao, R.X. Bearing fault diagnosis based on SVD feature extraction and transfer learning classification. In Proceedings of the 2015 Prognostics and System Health Management Conference (PHM), Beijing, China, 21–23 October 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Chen, N.; Shen, C. A new deep transfer learning method for bearing fault diagnosis under different working conditions. IEEE Sens. J. 2019, 20, 8394–8402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Gao, L.; Li, X. A new deep transfer learning based on sparse auto-encoder for fault diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2017, 49, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, W.; Ding, Q.; Sun, J.-Q. Multi-layer domain adaptation method for rolling bearing fault diagnosis. Signal Process. 2019, 157, 180–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Lei, Y.; Jia, F.; Xing, S. An intelligent fault diagnosis approach based on transfer learning from laboratory bearings to locomotive bearings. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2019, 122, 692–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Li, W.; Tong, Z.; Zhang, M. Bearing fault diagnosis under varying working condition based on domain adaptation. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.09890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.; Xie, W.; Pei, Z. Semi-supervised adversarial discriminative learning approach for intelligent fault diagnosis of wind turbine. Inf. Sci. 2023, 648, 119496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Liang, B.; Cheng, Y.; Meng, D.; Yang, J.; Zhang, T. Deep model based domain adaptation for fault diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2016, 64, 2296–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.; Liu, C.; Yang, W.; Jiang, D. Deep transfer network with joint distribution adaptation: A new intelligent fault diagnosis framework for industry application. ISA Trans. 2020, 97, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.; Shao, H.; Wang, P.; Lin, J.J.; Cheng, J.; Yang, Y. Deep transfer multi-wavelet auto-encoder for intelligent fault diagnosis of gearbox with few target training samples. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2020, 191, 105313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Wang, Z.; Tang, Z.; Huang, K.; Zhu, H. A deep transfer learning method based on stacked autoencoder for cross-domain fault diagnosis. Appl. Math. Comput. 2021, 408, 126318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; McAleer, S.; Yan, R.; Baldi, P. Highly Accurate Machine Fault Diagnosis Using Deep Transfer Learning. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2019, 15, 2446–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, P.; Walambe, R.; Ramanna, S.; Kotecha, K. Domain Adaptation: Challenges, Methods, Datasets, and Applications. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 6973–7020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzeng, E.; Hoffman, J.; Saenko, K.; Darrell, T. Adversarial discriminative domain adaptation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopalan, S.; Purohit, A.; Singh, J. Genetically optimised SMOTE-based adversarial discriminative domain adaptation for rotor fault diagnosis at variable operating conditions. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2024, 35, 106109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.