Abstract

We investigate the behavior of solutions of second-order elliptic Dirichlet problems for a convex domain by using a “gliding hump” technique and prove that there are no contour limits at a specified point of the boundary of the domain. Then we consider two-dimensional domains which have a reentrant (i.e., nonconvex) corner at a point P of the boundary of the domain. Assuming certain comparison functions exist, we prove that for any solution of an appropriate Dirichlet problem on the domain whose graph has finite area, there are infinitely many curves of finite length in the domain ending at P along which the solution has a limit at P. We then prove that such behavior occurs for quasilinear operations with positive genre.

MSC:

35J67; 35J93; 53A10

1. Introduction

The study of the nonexistence of classical solutions of the Dirichlet problem

when Q is a second-order elliptic partial differential operator and has a rich history (e.g., [1] (§ 14.4), [2] (§ 406–416), [3,4,5]). When is discontinuous at a classical solution of (1) cannot exist; one example is the helicoid which satisfies the two-dimensional Laplace and minimal surface equations in () and is a generalized (e.g., Perron) solution of the corresponding Dirichlet problems (e.g., [2]). Classical Phragmen–Lindeloff theorems imply that solutions of linear, uniformly elliptic equations which have jump discontinuities at points of the boundary and are bounded or satisfy growth conditions near these points of discontinuity have radial limits at these points (e.g., [6,7]). Solutions of prescribed mean curvature equations with jump discontinuities at points on when is a domain in have radial limits at these points without imposing any growth or boundedness conditions (e.g., [8,9]).

If we eliminate the restriction that has jump discontinuities at points on what can be said about the “contour limits” at of a generalized solution of (1)? Here, by “contour limits”, we mean limits along curves (or types of curves) which have P as an endpoint, such as radial limits, tangential limits or nontangential limits. When, for example, is a unit ball in and f is a generalized solution of (1) which has an asymptotic value a at we see that a is a contour limit of f at thus, asymptotic values can be considered as a special case of contour limits (e.g., [10,11,12]). There are, for example, numerous examples of the existence or nonexistence of different types of contour limits for harmonic functions (e.g., [13,14,15]). For the minimal surface equation on there are generalized solutions of (1) for which none of the radial limits exist at a specified point ([16]). The construction of such examples can often be characterized as using a “gliding hump technique” (e.g., [17]). Gliding hump techniques work by constructing a sequence (in this case, a sequence of solutions of (1)) with certain properties and by showing that the assumption that the limit of this sequence has a specific property leads to a contradiction. Of course, in these gliding hump examples, the boundary data is highly oscillatory at P (e.g., like ). Some recent articles on the Dirichlet problem allowing highly oscillatory boundary data or highly oscillatory coefficients (in (4)) are ([18,19]); other recent articles on elliptic boundary value problems involve inverse problems ([20]), capillary hypersurfaces in a wedge ([21]) and the Dirichlet problem of translating mean curvature equations ([22]).

In this study, we first investigate a slight modification of the gliding hump technique used in [16] and consider its application to generalized solutions of (1) when Q is a quasilinear elliptic operator on which may not be uniformly elliptic. When is convex, we construct examples of generalized solutions of (1) such that for any curve in ending at the limit of f at P along does not exist (see Theorem 1). In the cases under consideration, the structure of the operator and the geometry of the domain play critical roles; in particular, barriers for (1) at a point may only exist if is locally convex at P (e.g., [1] (Chapter 14)) or mean convex ([23]). Second, we consider domains which have a nonconvex corner at a point and operators Q which have a well-defined genre g (see Definition 3). In 1912, Sergei Bernstein ([24]) expressed the degree of nonlinearity of a quasilinear elliptic partial differential equation through the concept of “genre”, and Jim Serrin extended this concept in their monumental 1969 paper [5]. Using comparison functions from [5,25,26] and assuming that we shall prove that for any generalized solution of (1) whose graph has finite area, there exist infinitely many paths of finite length in ending at P such that the limit of f at P along exists (see Theorem 3). Third, if we assume has a jump discontinuity at P and Q is an operator with then we obtain this same conclusion without assuming has a nonconvex corner at P (see Theorem 4).

The significance of this work is its examination of the question “How might a bounded generalized solution of (1) behave at (or near) a point when is discontinuous at P?” as well as its illustration of the importance of the geometry of (i.e., do local barriers for (1) exist at and near P), the genre of Q and the type of discontinuity of at One question of interest is “Does there exist a connection between the existence of radial limits of f at P and the existence of any contour limit of f at P?” Is there any way of constructing a bounded generalized solution f of (1) which does not have radial limits at P and is fundamentally different than that in Section 2?

2. The Gliding Hump Construction

Let and be a bounded, open, locally Lipschitz domain. Consider the Dirichlet problem

where Q is a quasilinear elliptic operator on given by

for and When there is a neighborhood of each point such that and is convex, local barriers for (2) and (3) exist in (e.g., [1] (Chapter 14)) in for each (as might happen when is smooth on ), and therefore, the generalized (e.g., Perron) solution f of (2) and (3) will satisfy on even if is highly oscillatory at P (so that does not have a one-sided limit from either side of P when

Let us suppose that the following two assumptions hold for

Assumption 1

Assumption 2

Remark 1.

The validity of these assumptions follows when interior a priori gradient estimates exist. The proof of the Compactness Principle follows from a priori gradient estimates and a uniform bound on the magnitude of f when Q is the two-dimensional minimal surface equation ([27] (p. 323)). The Monotone Convergence Theorem ([27] (p. 329)), which is used in the proof of the Localization Lemma for minimal surfaces ([16] (Lemma)), relies on an a priori estimate of the gradient of nonnegative solutions (e.g., footnote 4 of [27] (p. 329)). Such a priori gradient estimates occur in certain classes of elliptic equations (e.g., [28,29,30,31,32], [1] (Theorem 15.3 and Theorem 16.21)). However, the following comment in 1969 by Serrin ([5] (p. 492)) illustrates the difficulty in obtaining such a priori estimates: “That the result stated there” (in [24]) “cannot be correct follows from an example of Finn (1954, page 399). The problem is of course that of obtaining interior estimates for the gradient of a solution in terms of a maximum bound, but independent of the particular boundary data”.

Theorem 1.

Suppose Assumptions 1 and 2 hold for Let be an open convex set with and let There exists satisfying in Ω with on and on for each where and is a decreasing sequence in with and constructed using a (modified) gliding hump technique. There is no path γ in Ω from an interior point of Ω to P along which f has a limit at

Proof.

Let be an open convex set such that Let satisfy (2) in such that and Since there exists such that for Set From Assumption 2, we see that there exists , which satisfies (2) in such that and where Notice that for each

We shall construct our “gliding hump” sequence. Let us suppose have been defined. Set and

Then Assumption 1 implies that there exists , which satisfies (2) in such that and Since and there exists with such that

in particular, for each

For each consider the compact subsets of The sequence is uniformly bounded and so Assumption 1 implies that a subsequence of still denoted converges uniformly on compacta in to a solution f of (2) in such that Notice that for each converges uniformly on to f and so when for Thus, f has an infinite number of “ridges” (i.e., (where ) for each ) and “troughs” (i.e., (where ) for each ) converging to In particular, there is no path in from an interior point of to along which f has a limit at □

Remark 2.

When Ω is the unit ball in and one might characterize the conclusion of Theorem 1 as follows: There exists satisfying in Ω with such that f has no asymptotic value at P but every value in is a limit value of f at P in the sense that for each there is a sequence in Ω converging to P and for each

3. Nonconvex Corners

The existence of the radial limits at of when is a locally Lipschitz open set in and f is a solution of a prescribed mean curvature equation (with mean curvature H) for various choices of H (and Dirichlet or contact angle boundary conditions) was first established by the second author for (e.g., [2] (§ 416)) and extended to general H in [8] (see also [33,34]). These results assume the boundary data satisfies certain conditions; for example, in Dirichlet problems, the prescribed boundary data have, at worst, a jump discontinuity at The proofs of these results follow the pattern in [8] of proving that a conformal parameterization of the graph of f is continuous on the closure of the parameter domain and using [35] to establish the Hölder continuity on of the first derivative of the parameterization (for an appropriate ) and then prove that the radial limits exist.

An initial part of the proofs above consists of the following argument. Suppose that and has finite area For our purposes, we may assume is a simply connected set. Let be an isothermal (i.e., conformal) parameterization of so that where For let and be the length of the image curve The Courant–Lebesgue Lemma asserts that for each there exists a number so that where

The “Fundamental Lemma” ([36] (Lemma 3.1)) used above plays a critical role:

Lemma 1

(Courant–Lebesgue Lemma). In a domain B of the —plane, consider the class of piecewise smooth vectors X for which the Dirichlet integral is uniformly bounded by a constant

About an arbitrary fixed point O, we draw circles of radius Denote by an arc or set of arcs of such a circle contained in by s arclength on Then for every positive there exists a value depending on with such that

tending to zero for Furthermore, the square of the length of the image of in —space has the bound i.e., the oscillation of on is at most

Recall that where is the surface area of the image of and if the surface is represented in conformal (i.e., isothermal or isometric) coordinates ([36] (§ 3.1)).

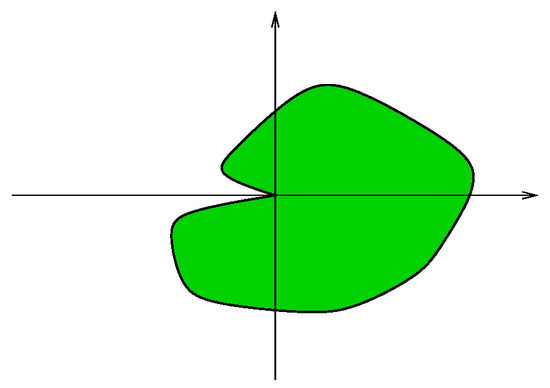

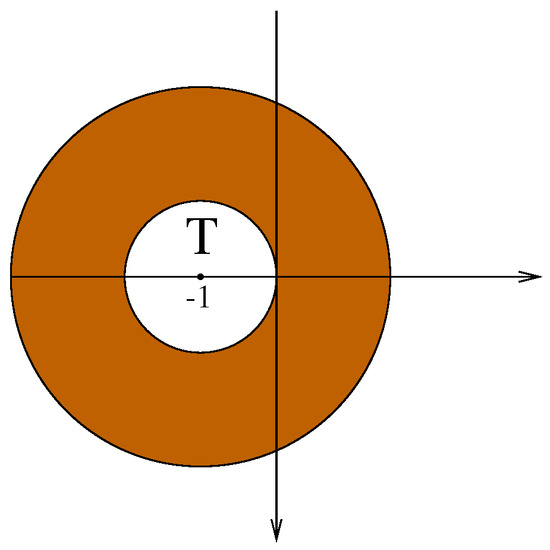

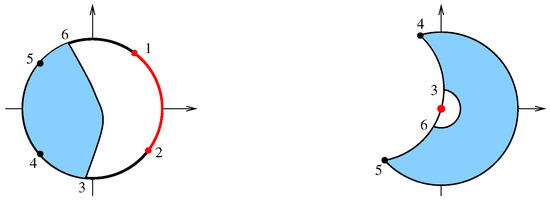

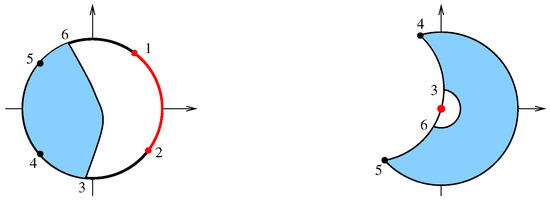

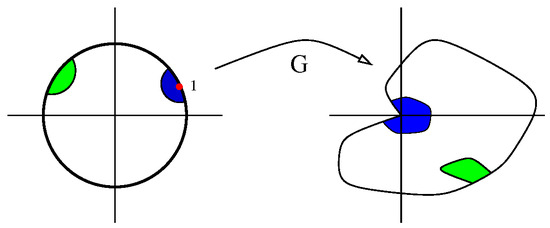

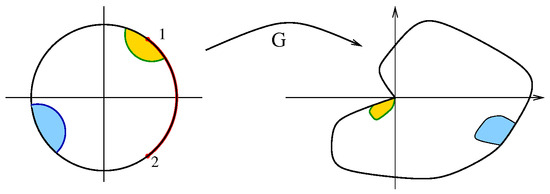

In [9], the proofs above (of, for example, [8]) are modified to prove that if has a “reentrant” (i.e., nonconvex) corner at (e.g., Figure 1), then the nontangential radial limits at P of f exist without regard to the restrictions on the boundary data noted above. To see that the conformal parameterization of the graph of f is continuous on the closure of the parameter domain, one uses the Courant–Lebesgue Lemma as noted and particular comparison functions, specifically catenoids for and unduloids for to control the oscillation of the third component of Y and prove that Y is uniformly continuous on This topic was investigated further, illustrated in [37] (Example 1.4) (see also [38]) (p. 430) when Q is the minimal surface operator on and (see Figure 2). In this case, is not locally convex at any point of the inner boundary of and f need not equal on Standard results (e.g., [38] (Theorem 3)) show that To see that Y is continuous on the closure of the parameter domain, one works in a neighborhood U of P and uses “Bernstein functions” ([37] (Lemma 2.3)) to control the oscillation of the third component of the conformal parameterization of the graph of f restricted to (a catenoid would have worked just as well for this particular example). The continuity of f at P then follows from the symmetry of the problem.

Figure 1.

A domain with a reentrant corner at .

Figure 2.

.

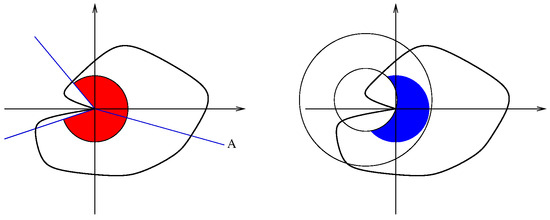

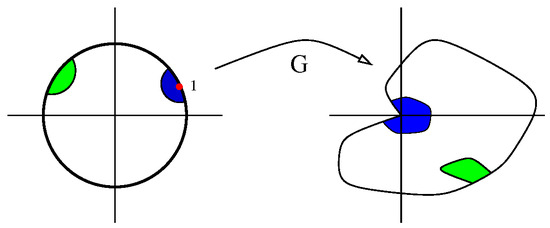

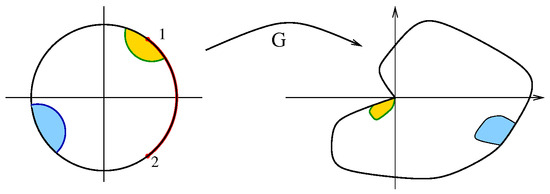

A brief discussion of the use of catenoids and unduloids as comparison functions in [9] may help illustrate the use of comparison functions in Theorems 2 and 3. In [9], nothing (except boundedness) is known about the behavior of f (or ) on , and it is necessary to avoid Thus, we restrict our attention to a subdomain of such as those illustrated in Figure 3 (right) and Figure 4 (right). If is the isothermal parameterization of the graph of f over with and then the oscillation of z on the curves labeled a through g in Figure 4 (left), is controlled by the Courant–Lebesgue Lemma. If m and M are the infimum and supremum of z on then [1] (Theorem 14.10) implies in the region between and where the graphs of are appropriate catenoids in [9]. Since we have uniform control of in we see that z and Y are uniformly continuous on

Figure 3.

in (); .

Figure 4.

Examples of circular arcs and .

Assuming that the use of catenoids or unduloids as comparison functions could be replaced by different comparison functions for (2) (e.g., [37]), this argument depends solely on the assumption that the area of the graph of the solution of (2) is finite. So suppose that there exist numbers and functions such that the graph of makes a contact angle of zero with the cylinder and the graph of makes a contact angle of with the cylinder where and Suppose further that

for and for where and for These functions are “Bernstein (comparison) functions” and they are necessary to prove the existence of contour limits (see Remark 4); they will play a critical role in the remainder of this article (see [1] (p. 357) for a brief discussion of such comparison functions).

In contrast to Theorem 1, we claim the following:

Theorem 2.

Suppose is an open set, and there exist and such that where (see Figure 3 (left)). Suppose there exist comparison functions for (2) as described above. Let satisfy (2) such that the area of the graph of f is finite. Then there exist (infinitely many) paths γ of finite length in Ω ending at P along which f has a limit at

Proof.

We may assume and Set and let be the area of Choose such that and set for some (see Figure 3 (right)). Let then the area of satisfies Now consists of three pieces, which are and the two components of notice that and so

There exists an isothermal (conformal) parameterization of that is, Y is a diffeomorphism of E and on on and where is the Dirichlet integral of Let us write and set for so on E and Then G extends to a function in G is a diffeomorphism of E and the preimage under G of is an open, connected arc of and G is a homeomorphism of and (see the proof of [8] (Lemma 2.1)).

We claim that Y is uniformly continuous on E and so extends to a function This only requires that we prove that the third component of Y is uniformly continuous on We shall let denote the set of continuous, strictly increasing functions from the nonnegative reals to the nonnegative reals which are zero at zero; moduli of continuity will be chosen in this class.

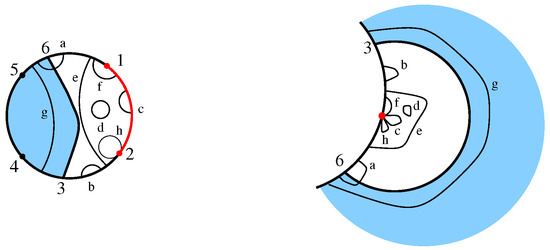

Set (see Figure 5, where is the (shorter) arc joining points labeled 1 and 2). Now hence , and so there exists such that when Since for each there exists such that whenever

Figure 5.

(left), (right).

For let and be the length of the image curve as before. Let and Let and then on and on Further and for

Let Choose such that and Let From the Courant–Lebesgue Lemma, there exists such that There are two possibilities: (i) and (ii) Consider case (i) first. Then and so, for

Now we consider case (ii). Let ( may not be in ) and set Then there exists a point Setting we have and so and Thus,

Then the types of possible curves and their images are illustrated in Figure 4 and are as follows: (1) is a closed curve with (labeled c, h in Figure 4), (2) is a curve joining P to a point on (labeled f in Figure 4), (3) is a curve joining a point on to another point on (labeled a, b, e, g in Figure 4) and (4) is a closed curve and (labeled d in Figure 4).

Notice that

for Using the “Bernstein comparison argument” (e.g., [1] (Theorem 14.10), [5] (Theorem 15.1)), we then see that

for Now

and

Thus, lies in a strip of width less than and so Thus, is uniformly continuous on E and so extends to a function

Now if is a single point on then and so f has a limit at P along every path in ending at Suppose is an arc of of positive length. Then exists for every path which ends at a point Since we see that the paths are finite length paths in with P as an endpoint and along which f has a limit at P of . □

Remark 3.

From case (ii) in the proof of Theorem 2, we let be an open subset of E such that then can be shown to be uniformly continuous on (i.e., [26] (Theorem 4) allows one to prove that (6) holds).

Remark 4.

When Q is a uniformly elliptic operator, Bernstein (comparison) functions do not exist. If they did exist, they could be used to prove, for example, that the harmonic function f defined in the unit disc by

and vanishing at every point of the unit circle except is bounded, even though as ([26] (p. 166)). (When Q is uniformly elliptic on one can argue as in [6] (p. 1180) (after freezing coefficients if Q is not linear) and see that a similar contradiction would occur in this case (see also the references in [6] and [1] (Chapters 6 & 14)).) Further, the conclusion of Theorem 2 might be false for uniformly elliptic equations. Take, for example, a bounded harmonic function g on the unit disc in which has no asymptotic value at (e.g., Theorem 1) and conformally map g to a domain Ω with a reentrant corner at such that maps to the resulting bounded harmonic function will not have any contour limit at Whether or not the graph of this harmonic function has finite surface area over Ω (or a suitable ) is uncertain.

4. Singularly Elliptic Equations

In the further study of the solvability of the Dirichlet problem, Serrin ([5] (§ 17)) introduced the term singularly elliptic operators to demonstrate that the structure of the coefficient matrix can lead to the nonexistence of classical solutions of (2) and (3). This term was later modified as follows.

Definition 1

([25]). The elliptic operator Q given in (4) is called strongly singularly elliptic if

and there is a positive function such that

and for any positive constant if we have

Definition 2

([26]). The elliptic operator Q given in (4) is called weakly singularly elliptic if

and there is a positive function such that

and for any positive constant if we have

Definition 3

([5,24]). The elliptic operator Q given in (4) is said to have genre g if

and there are positive constants and such that for we have

Notice that if Q has genre then Q is strongly singularly elliptic if and is weakly singularly elliptic if . (Serrin ([5] (p. 426)) illustrates by example that “It is easy to construct equations having any given nonnegative genre g”.) Uniformly elliptic operators have genre , while the minimal surface operator and operators of mean curvature type have genre

Genre most easily characterizes the extent to which elliptic operators differ from being uniformly elliptic. We shall prove the following two theorems.

Theorem 3.

The proof of Theorem 3 will follow from Corollary 1 of Theorem 2.

Theorem 4.

Suppose is an open set, and Q has genre Let and satisfy (2). Suppose further that ϕ has a jump discontinuity at on and the area of the graph of f is finite. Then there exist (infinitely many) paths γ of finite length in Ω ending at P along which f has a limit at

The proof of Theorem 4 will follow from Corollary 2.

Corollary 1.

Suppose is an open set, Q is strongly singularly elliptic, there are positive constants μ and H such that

and there exist and (and ) such that Let and satisfy (2) such that the area of the graph of f is finite. Then there exist (infinitely many) paths γ of finite length in Ω ending at P along which f has a limit at

Proof.

First we note that (e.g., [25] (Theorem 1), [26] (Theorem 3)). We need to prove that there exist comparison functions for (2) as described in Section 3. These comparison functions are given in [25], and a description here is useful. Set if and if then

Set

Clearly, is a monotonically decreasing function with range and so has an inverse function Now is a positive, monotonically decreasing function of with range and

For define

Let and () be given in the proof of [25] (Lemma 2) (with ). Set and choose such that Set

(Of course, here.) Define

where Then is the desired (upper) comparison function (and is the desired (lower) comparison function). (In particular, ref. [25] (24) shows that in for any constant Since the graph of makes a contact angle of zero with the cylinder ) The conclusion of the corollary follows from Theorem 2. □

Proof of Theorem 3.

Since Q has genre there exist positive constants and such that for Thus,

If we define and let we have

and

In the first case, we have , and in the second case, we have In either situation, we see that

and so Q is strongly singularly elliptic. Further, if Theorem 3 then follows from Corollary 1. □

Suppose the hypotheses of Corollary 1 are satisfied except that Q is weakly singularly elliptic rather than strongly singularly elliptic. In this case, it is uncertain if the conclusion of Corollary 1 holds. The function defined in the proof of Corollary 1 still satisfies in for any constant c ([26] (31)) and however, from [26] (24), we see that In this case, we significantly strengthen the requirements on and eliminate the nonconvexity requirement in order to obtain the conclusion of Corollary 1.

Corollary 2.

Suppose is an open set, Q is weakly singularly elliptic, there are positive constants μ and H such that

Let and satisfy (2). Suppose further that ϕ has a jump discontinuity at on and the area of the graph of f is finite. Then there exist (infinitely many) paths γ of finite length in Ω ending at P along which f has a limit at

Proof.

We may assume and let be the modulus of continuity of that is, when do not lie on different components of Let the limits of at P from the two sides of be denoted and First we note that (e.g., [26] (Theorem 3)); in fact, the only use of the fact that Q is weakly singularly elliptic is through the general maximum principle (i.e., [26,39]). We use the notation in the proofs of Theorem 2 and Corollary 1.

Set and let be the area of There exists an isothermal (conformal) parameterization of we have

Then G is a diffeomorphism of E and the preimage under G of is an open, connected arc of G is a homeomorphism of and

Suppose for some From the Courant–Lebesgue lemma, we know that there are curves in joining points and on each side on of P such that has length at most and so Letting go to zero, we see that and

Let If is not a single point, then it is a closed arc of of diameter for some we may assume If for some set Select such that

Let with Let be the midpoint of and Since and lie in Set

If then the maximum principle implies

and so

If for some then [26] (Theorem 3) implies

and so

Now suppose is an arc in with positive diameter and so that (If then a case already considered.) Let and be the endpoints of

Consider first the case in which for some and so (see Figure 6). Then and since Thus,

Figure 6.

for some .

Then [26] (Theorem 3) implies

and so

Consider next the case in which where has positive length. Notice that cannot contain a neighborhood in of P since as illustrated in Figure 7. Thus, the jump discontinuity of at P does not affect the reasoning in the case above and that argument continues to show that Hence, is uniformly continuous on E and extends to a function in

Figure 7.

is an interval.

Now if is a single point on then and so f has a limit at P along every path in ending at If is an arc of of positive length, then exists for every path which ends at a point Since we see that the paths are finite-length paths in with P as an endpoint and along which f has a limit at P of . □

Proof of Theorem 4.

This follows from Corollary 2 using similar arguments to those in the proof of Theorem 3. □

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K.; Methodology, K.E.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The first author would like to acknowledge the support of Prince Sultan University for paying the Article Processing Charges (APC) of this publication. The author would like to thank Prince Sultan University for their support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gilbarg, D.; Trudinger, N.S. Elliptic Partial Differential Equations of Second Order, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Nitsche, J.C.C. Lectures on Minimal Surfaces: Volume 1; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Concus, P. Numerical Study of the Discrete Minimal Surface Equation in a Nonconvex Domain; Report LBL-2033; Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Radó, T. Contributions to the theory of minimal surfaces. Acta Litt. Sci. Univ. Szeged 1932, 6, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Serrin, J. The problem of Dirichlet for quasilinear equations with many independent variables. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A 1969, 264, 413–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bear, H.S.; Hile, G.N. Behaviour of solutions of elliptic differential inequalities near a point of discontinuous boundary data. Commun. Partial Differ. Equ. 1983, 8, 1175–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, A. On two theorems of Phragmen-Lindelof for linear elliptic and parabolic differential equations of the second order. Pac. J. Math. 1957, 7, 1563–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elcrat, A.; Lancaster, K.E. Boundary behavior of a nonparametric surface of prescribed mean curvature near a reentrant corner. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 1986, 297, 645–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entekhabi, M.; Lancaster, K.E. Radial Limits of Bounded Nonparametric PMC Surfaces. Pac. J. Math. 2016, 283, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J.L.; Heinonen, J.; Llorente, J.G. Asymptotic values of subharmonic functions. Proc. Lond. Math. Soc. 1996, 73, 404–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLane, G.R. Asymptotic Values of Holomorphic Functions; Rice University: Houston, TX, USA, 1963; p. 49. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, J.E. Asymptotic values of functions holomorphic in the unit disc. Michagin Math. J. 1965, 12, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikawa, H. Hermonic functions having no tangential limits. Proc. AMS 1990, 108, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ash, J.M.; Brown, R. Uniqueness and non uniqueness for harmonic functions with zero nontangential limits. In ICM-90 Satellite Conference Proceedings; Igari, S., Ed.; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, G., Jr. Harmonic functions on the unit disc II. Ill. J. Math. 1968, 12, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, K.E. Existence and Nonexistence of Radial Limits of Minimal Surfaces. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 1989, 106, 757–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swartz, C. A gliding hump property and Banach-Mackey spaces. Proyecciones 2001, 20, 243–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dindos, M.; Pipher, J. Boundary value problems for elliptic operators satisfying Carleson condition. Vietnam J. Math. 2024, 52, 627–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dindos, M.; Sätterqvist, E.; Ulmer, M. Perturbation theory for second order elliptic operators with BMO antisymmetric part. Vietnam J. Math. 2024, 52, 519–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, M. Bayesian Nonparametric Inference in Elliptic PDEs: Convergence Rates and Implementation. Foundations 2025, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Wang, G.; Xia, C.; Zhang, X. Heintze-Karcher inequality and capillary hypersurfaces in a wedge. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.13839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H. The Dirichlet problem of translating mean curvature equations. Rev. Mat. Iberoam. 2024, 40, 1529–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, H.; Serrin, J. The Dirichlet problem for the minimal Surface equation, with infinite data. Bull. Am. Math. Soc. 1966, 72, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, S. Sur les equations du calcul des variations. Ann. Sci. Ecole Norm. Supérieure 1912, 29, 431–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Lancaster, K. A comparison principle for quasilinear elliptic equations and its application. Pac. J. Math. 1998, 184, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Lancaster, K. Theorems of Phragmen-Lindelof type for quasilinear elliptic equations. J. Reine Angew. Math. 1999, 514, 165–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, H.; Serrin, J. Variational problems of minimal surface type II. Boundary value problems for the minimal surface equation. Arch. Ration. Mech. Anal. 1966, 21, 321–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R. On equations of minimal surface type. Ann. Math. 1954, 60, 397–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, H.; Serrin, J. Variational problems of minimal surface type I. Arch. Ration. Mech. Anal. 1963, 12, 321–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrin, J. A priori estimates for solutions of the minimal surface equation. Arch. Rat. Mech. Anal. 1963, 14, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, L. Interior Gradient Bounds for Non-uniformly Elliptic Equations. Indiana Univ. Math. J. 1976, 25, 821–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, L. Equations of mean curvature type in 2 independent variables. Pac. J. Math. 1977, 69, 245–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.T.; Finn, R.; Miersemann, E. Capillary surfaces in wedge domains. Pac. J. Math. 2008, 236, 283–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Finn, R. On a theorem of Lancaster and Siegel. Pac. J. Math. 2004, 213, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, E. Über das Randverhalten quasilinear elliptischer Systeme mit isothermen Parametern. Math. Z. 1970, 113, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courant, R. Dirichlet’s Principle, Conformal Mapping, and Minimal Surfaces; Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Entekhabi, M.; Lancaster, K.E. Boundary Continuity of Nonparametric Prescribed Mean Curvature Surfaces. Taiwan. J. Math. 2020, 24, 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, L. Boundary regularity of solutions of the non-parametric least area problem. Ann. Math. 1976, 103, 429–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spruck, J. Infinite boundary value problems for surfaces of constant mean curvature. Arch. Ration. Mech. Anal. 1972, 49, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).