Abstract

A fuzzified matrix space consists of a collection of matrices with a fuzzy structure, modeling the cases of uncertainty on the part of values of different matrices, including the uncertainty of the very existence of matrices with the given values. The fuzzified matrix space also serves as a test for the admissibility of certain approximate solutions to matrix equations, as well as a test for the approximate validity of certain laws. We introduce quotient structures derived from the original fuzzified matrix space and demonstrate the transferability of certain fuzzy properties from the fuzzified matrix space to its associated quotient structures. These properties encompass various aspects, including the solvability and unique solvability of equations of a specific type, the (unique) solvability of individual equations, as well as the validity of identities such as associativity. While the solvability and unique solvability of a single equation in a matrix space are equivalent to the solvability and unique solvability in a certain quotient structure, we proved that the (unique) solvability of a whole type of equations, as well as the validity of a certain algebraic law, are equivalent to the (unique) solvability and validity in all the quotient structures. Consequently, these quotient structures serve as an effective tool for evaluating whether specific properties hold within a given fuzzified matrix space.

Keywords:

fuzzified matrix space; fuzzy relations; weak solutions to equations; L-valued fuzzy sets; weak equivalence; quotient structures MSC:

08A72; 03E72; 03B52

1. Introduction

Starting from Zadeh’s definition of the fuzzy set as a generalized subset of a given set [1], Rosenfeld applied this concept to sets endowed with algebraic structures, namely to groupoids and groups [2]. He introduced fuzzy subgroupoid and fuzzy subgroup as natural generalizations of the concepts of subgroupoid and subgroup. This was generalized in [3], in the concept of fuzzy subalgebra, introduced by Filep and Maurer in 1989, who also introduced the concept of compatibility of a fuzzy relation with the algebra operations. Another direction for generalizing the notion of compatibility can be found in [4].

In the course of time, the interval in the definition of the fuzzy set was replaced with more general codomain structures, mainly with lattices with or without additional operations. Actually, it was first done already in 1967, when Goguen introduced the notion of so-called L-fuzzy sets. They were defined as L-valued sets, i.e., as mappings from a given set to a given lattice L [5]. Thus, a membership degree was no longer measured in percentages, i.e., by an element in interval, but it was measured by a lattice element. Already in 1975. Negoita and Ralescu published a book dealing with L-valued fuzzy sets [6], and in 1976, Sanchez published a paper providing a methodology for the solution of certain basic fuzzy relational equations, taking a complete Browerian lattice as a codomain lattice for L-valued fuzzy sets [7]. After a pioneering work of Pavelka, who introduced a fuzzy logic with truth values in a residuated lattice [8], many researchers investigated fuzzy sets with residuated lattices as suitable codomain lattices (see e.g. [9]). Different cases of bounded codomain lattices with or without some additional properties or additional structures were also studied, and are currently being studied (see [10,11]). In line with such generalizations, a definition of fuzzy subalgebras and the definition of compatibility of a fuzzy relation with an algebraic structure were generalized as well.

Another direction in the generalization of the concept of a fuzzy subalgebra of a crisp algebra—with lattice-valued equality replacing the classical one—was introduced, e.g., in [12] for groups, [13] for quasigroups, [14] for rings, and, in a special form, in [15] for groupoids.

In our approach, a complete lattice was used as the codomain lattice. Instead of a fuzzy subset that is closed (in the fuzzy sense) under the groupoid operation and a fuzzy relation compatible with the groupoid operation, we consider a more general situation: we use a mapping , where for each of three sets is equipped with a weak fuzzy equivalence relation (i.e., a symmetric and transitive fuzzy relation), and these relations are compatible with the given mapping. In the case , we obtain a fuzzy subgroupoid of A). This structure gives rise to the fuzzy subsets , , and and, for every p in the codomain lattice, to a mapping induced by ∘, which maps the direct product of certain quotient sets of the p-cuts of and to a quotient set of the p-cut of .

Such an approach is used to define the so-called matrix space (in this article called fuzzified matrix space) [15]. It consists of a set of ordered pairs, the first component of which is the set of all matrices of a given order, and the second component is a weak fuzzy equivalence relation defined on it. It is characterized by the compatibility of the weak fuzzy equivalence relations with a partial binary operation defined on matrices, which is a generalized matrix product. This operation is defined when a usual matrix product would be defined, i.e., when the number of columns of the first matrix equals the number of rows of the second one.

We introduce cut and quotient structures naturally arising from a fuzzified matrix space. We study the so-called cutworthiness of some properties in a fuzzified matrix space, i.e., we study the connection between some fuzzy properties in a fuzzified matrix space and the related properties in the defined quotient structures.

We treat the problem of the existence of approximate solutions to matrix equations of an arbitrary equation type in a fuzzified matrix space. In order to do this, we give a definition of the type. A type of matrix equation is characterized by a unique arrangement of constants and variables. The definition of approximate solutions (so-called weak solutions) given in [15] is generalized to fit any matrix equation with the defined binary operation, and so is the definition of unique solvability. Here, we have an arbitrary number of variables in an equation, so the weak solutions are ordered sets of elements from the domain.

As for the unique solvability of a matrix equation in a fuzzified matrix space, it is, for a given equation, equivalent to the unique solvability of the related equation in a quotient structure. By proving this, we generalize a result from [15].

The uncertainty that is present in fuzzy sets gives us different possibilities for approximate problem solving, e.g., finding an approximate solution to an equation or a system of equations. There are different approaches, depending on where uncertainty exists. For example, in the case of our study, initial data (or known objects) are known and without any uncertainty; thus, they are represented by crisp objects. Even the solutions we are looking for are precise, crisp objects, but we allow them not to be completely correct in order to find at least approximate solutions to the given crisp problems. The accuracy depends on the introduced fuzzy structure. A similar approach is contained in [16], where two known objects in a fuzzy relation equation are given precisely, whereas solutions must lie in an interval depending on them. Another approach must be applied if there is uncertainty in some of the initial input data, e.g., some known objects in an equation or a system of equations. In [17], a system of fuzzy equations is presented, where uncertainty exists in the known objects on the right side of the equations, but not in those on the left side, where there are exact, crisp coefficients. In [18], fuzzy equations are presented in which there is only one known object lying on the left side of the equations, and it is a fuzzy object, i.e., an object containing approximate information, so the uncertainty exists on the left side of the equations. Finally, uncertainty may exist in the known objects on both sides of a fuzzy equation, as in the systems of fuzzy equations considered in [19], or in the matrix equations considered in [20]. In all these cases we mentioned, where uncertainty exists in the input objects, the task of solving is defined in a way that no new uncertainties arise in the solving process, other than those following from the uncertainty of the input data. To achieve this, moreover, in [17,20], the problem of solving equations with uncertainties in the known objects is actually reduced to crisp problems. In many other cases, it is allowed for some new uncertainties to arise when solving equations that have already been stated as fuzzy equations. When dealing with systems of fuzzy equations, two main approaches to such approximate reasoning were developed. The first one, starting with [21,22,23], is based on allowing some input data (i.e., equations) to be omitted and defining an approximate solution as a solution to the rest, i.e., to most of the equations. Another approach, presented, e.g., in [24,25], was to introduce a certain degree to which a fuzzy set or fuzzy relation solves (or does not solve) a fuzzy equation or a system of fuzzy equations. These approaches, as well as the one presented in this paper, enable us to look for an approximate solution when there is no exact solution.

Since matrix products are often associative, we define an approximate law in the fuzzified matrix space corresponding to associativity. Moreover, for any law in a set of matrices, we define, using this approach, a corresponding approximate law, which we prove to be cutworthy.

In 1964, Give’on defined the algebra of lattice-valued matrices [26], though not in a fuzzy setting. But since a fuzzy relation between two finite sets can be described by a matrix, a sort of L-valued fuzzy matrices appeared simultaneously with the newly introduced L-valued fuzzy sets, i.e., in 1967, under the name of L-relations [5]. Although most recent investigations on fuzzy matrices predominantly use matrices with values in -interval, still there are some more recent works dealing with more genereal lattice-valued matrices [27,28,29,30]. The investigation of different classes of fuzzy matrix equations (fuzzy relational equations) continues to be of significant relevance in recent years, due to their wide range of applications [31,32,33].

The composition of two L-valued fuzzy relations can be seen as a sort of matrix product. To solve a fuzzy relational equation, we need to solve a matrix equation. To model the cases when there also exist uncertainties regarding the values of fuzzy relations, different cases of interval-valued fuzzy sets and relations were introduced for all kinds of fuzzy sets [34,35,36,37]. A notion of fuzzified matrix space presents another approach, which, applied to the case when matrices represent fuzzy relations, brings the possibility not only to model the uncertainty on the part of values of fuzzy relations, but also to model the uncertainty of their existence.

In Section 2, we recall some basic notions such as L-valued sets, relations and their cuts, as well as the notion of weak equivalence; we recall the notion of compatibility of a fuzzy relation with an algebraic structure and its recent generalization used to introduce a notion of matrix space. We also use this generalization in Section 3 (SubSection 3.1), to introduce quotient structures of a fuzzified matrix space. In SubSection 3.2, we introduce a set of terms and identities over a partial matrix groupoid and over the quotient structures of a matrix space defined over the partial matrix groupoid. We divide those terms and identities into types based on the arrangement of the variables and constants used, with different dimensions. In SubSection 3.3, we introduce a generalized matrix equation and the concept of weak solvability of such an equation. We prove a connection between the (unique) weak solvability of an equation and the (unique) weak solvability of a whole type of equations to the solvability of the corresponding equation(s) in the introduced quotient structures. In SubSection 3.4, we define so-called weak laws, which are fulfilled in a matrix space when the corresponding exact laws are kind of approximately satisfied in the partial matrix groupoid. We prove that a law in a matrix space is weakly satisfied if and only if it is (exactly) satisfied in all its quotient structures. In Section 4, we explain some future perspectives of this investigation.

2. Preliminaries and Notations

Throughout this paper, L is a complete lattice. By ∧ we denote the infimum and by ∨ the supremum in L. By ⩽ we denote the corresponding order relation, and by 0 and 1 the least and the greatest element of L, respectively.

If A is a set, an -valued set on (or an -valued subset of ), is a mapping : .

Given , a cut set at level or a -cut of an -valued fuzzy set : is a subset of A defined by

An L-valued fuzzy set R on , i.e., a mapping R : is called an -valued relation on .

Given and an L-valued relation R on A, by we denote the cut set of R at level p, and we also call it the cut relation at level .

We say that a property of L-valued sets (L-valued relations) is cutworthy if and only if the analog crisp property is satisfied on all the cut sets (relations).

Well-known properties of L-valued relations that we use here are as follows:

- R is symmetric if

- and R is transitive if .

The mentioned properties are cutworthy, in the sense that all the p-cuts of an L-valued relation are symmetric (or transitive) in the usual (crisp) sense, if and only if the L-valued relation is symmetric (or transitive), respectively.

If an L-valued relation is symmetric and transitive, it is called a weak L-valued equivalence relation.

Now, let A be equipped with some operations, i.e., let be an algebra, with the family of operations F. An L-valued subalgebra of is an L-valued set satisfying, for every operation with arity , and for all ,

We say that an L-valued relation R on A is compatible with the operations of if it is an L-valued subalgebra of , i.e., if the following two conditions hold: for every n-ary operation , for all , and for every nullary operation

The notion of compatibility was first introduced by Rosenfeld, for the group operations [2], including the binary operation. For a binary operation, the definition of compatibility was generalized to include the compatibility of a fuzzy binary operation with a fuzzy relation in [4]. Another possible generalization of the notion of compatibility of an L-valued relation with a binary operation of an algebra was introduced in [15], by the following definition.

Let , and be sets, and a function (i.e., an operation from to ). A ∘-compatible weak lattice-valued equivalence triple is an ordered triple of weak lattice-valued equivalences: (, such that the following condition is satisfied: for all , ,

If and , ∘ is just a binary operation on a set , and is a compatible weak lattice-valued equivalence.

This generalized compatibility is also cutworthy, as is proven in [15].

Lemma 1

([15]). Let and be sets, a function and let be an ordered triple, such that each is a weak lattice-valued equivalence on set for .

Then, is a ∘-compatible weak lattice-valued equivalence triple if and only if for every , and cuts , and :

If and then .

Let be a ∘-compatible weak lattice-valued equivalence triple. Then, L-valued sets for are defined by .

For every , because of the cutworthiness of symmetry and transitivity, , and are symmetric and transitive relations on and , respectively. They are equal with their restrictions to , , , which are also reflexive in , , ; thus, , and are equivalence relations of these subsets of and . Therefore, for every , we have the factor sets , , and , i.e., the sets of equivalence classes of these equivalence relations.

Let , and be the classes of in , respectively. We define an operation with

- In [15], the following proposition is proved, establishing that is a well-defined operation.

Proposition 1.

If and , then . Moreover, if and , then we have .

Let and be finite index sets and S be a set. Then a matrix over is a mapping . We call such a matrix a matrix over of order . By we denote the set of all matrices over S of order .

By definition, a matrix over of order is an ordered n-tuple of some ordered m-tuples of elements of S.

The set of all matrices over S is denoted by :

Let ∘ be a partial binary operation on , such that is defined for and if and only if , and then . The pair is called partial matrix groupoid.

We say that the operation ∘ is associative if whenever all operations on both sides of the equation are defined.

It is easy to check that if both operations on one side of the equality are defined, then the operations on the other side are also defined.

The following notion was introduced in [15]. Let be a partial matrix groupoid. An -valued matrix space (fuzzified matrix space) over is a set of ordered couples

, where each is a weak L-valued equivalence on , and such that for each , the tripple is a ∘-compatible weak lattice-valued equivalence triple.

3. Results

3.1. Quotient Structures of a Fuzzified Matrix Space

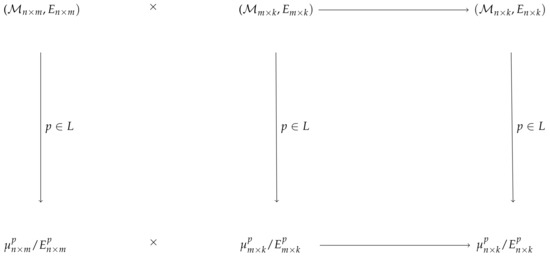

Let be an L-valued matrix space over a partial matrix groupoid . Let . For such an L-valued matrix space and , we define an algebraic structure consisting of the set and the partial binary operation derived from ∘ as in Equation (6). Such a structure is called a quotient structure of the partial matrix groupoid .

We also say that for every the elements of are elements in of the order . Using Proposition 1, we get that for all , and for any , the multiplication of matrices of dimensions and induces a multiplication in the corresponding quotient sets (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A quotient structure.

Example 1.

Let P be the set of prime numbers, let , and let the ordering on L be defined componentwise (taking the usual order in and taking ∞ to be the greatest element in ). That is, for , we define

Let be the set of matrices over , and be the matrix groupoid with the usual matrix multiplication. Let and , , we write , iff , for all .

We define by:

Since congruence is compatible with multiplication and addition, it is also compatible with matrix multiplication, i.e., if and , we have

If and , then and , where ; thus, and .

Thus, is a matrix space.

For all and we have , which implies that equals the greatest element in L (we shall denote it by 1). We interpret as the level of existence of the fuzzy matrix A; thus, all the matrices exist with certainty, and for all .

For any matrix A, we denote by the absolute value of the element in A having the greatest absolute value. For , such that , we have that for all greater than , ; thus, for , if for infinitely many p, then , and for any such ϕ, we have that is the diagonal (equality) relation in .

If for finitely many , i.e., for , we have that if and only if elements of are divisible by , ,…,, which holds if and only if elements of are divisible by .

We define a mapping Ψ, mapping to the set of matrices over of dimension , which maps A to the ordered set of matrices , such that matrix contains, in place of any element in matrix A, its remainder when divided by . It is obvious that Ψ is an epimorphism.

Note that iff , i.e., , and thus is isomorphic to the set of matrices of dimension over .

Since this holds for any pair , we have that is isomorphic to the set of matrices over , or to the set of matrices over .

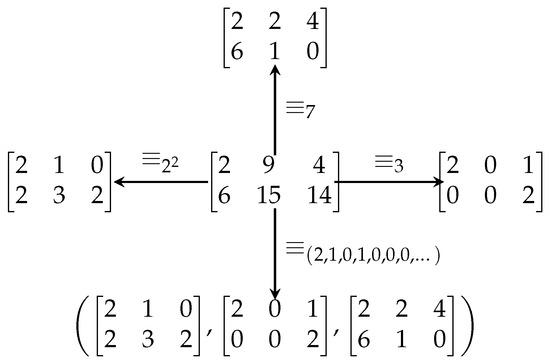

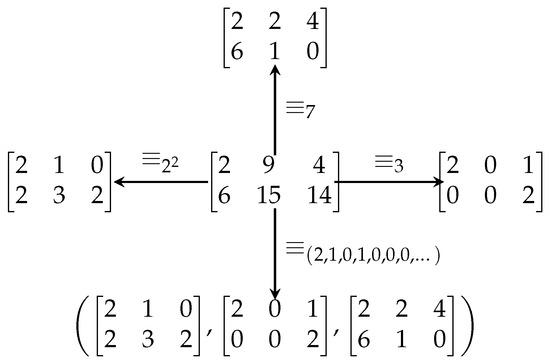

Figure 2 illustrates how a fuzzy matrix is projected in different quotient structures of this fuzzified matrix space. Here, ; ; ; for all others .

Figure 2.

An illustration of how a fuzzy matrix is projected in different quotient structures.

Example 2.

Let , and let be a set of matrices over S. Let , and ≤ the usual relation "less than or equal to".

We define a partial operation ∘ in the set of matrices:

Let A be a matrix of order , and C a matrix of order . We define as the matrix whose element in the i-th row and j-th column is the arithmetic mean of all the elements in the i-th row of A and j-th column of C.

To define fuzzy relations in the sets of matrices of the same order, we introduce some notation. If A is a matrix, is the smallest element of A, is the sum of all the elements of A, and is the arithmetic mean of all the elements of A. In every set of matrices of the same order we introduce the following fuzzy relation:

The fuzzy relation is obviously symmetric and transitive. We prove that it is also compatible with ∘:

Let be matrices of the order . Let ; .

We should prove that .

and thus

From the definition of ∘ and the above inequation we have:

Obviously, . Thus:

From (8) we obtain

which is equivalent to

i.e., equivalent to and .

This contradiction proves that (8) cannot hold, thus

Analogously, .

Thus, .

Thus, is a matrix space.

Here, .

Also, for we have:

Thus, is one-element structure for each pair , and is isomorphic to , where ∘ is a partial operation on , defined for iff , in which case .

The level of existence of any fuzzified matrix A of the dimension equals , while it is similar to the level p to all the matrices in ; thus, it collapses in into the only element of .

3.2. Terms and Identities in the Language with One Binary Operation

Let be a partial matrix groupoid and . We define two sets of terms in a language with one binary operation symbol ∘, which we call the set of terms over and the set of terms over . We start from —for the first set of terms—and from the universe of , for the second set of terms. Their elements are called constants. Let be any pair of natural numbers; every element of of the order is called a constant in of the order , and every element in of the order is called a constant in of the order . We add to both sets of terms, for every pair of natural numbers , the same countable set of variables (when convenient, we shall denote them differently).

We define the set of terms over (or the set of terms over ), in an inductive way:

- For every pair of natural numbers, constants in (or in , for the second set of terms) of the order , as well as variables from (for both sets of terms), are terms over (over ) of the order .

- If for , is a term over (or over ) of the order and is a term over (over ) of the order , then is a term over (over ) of the order .

- Terms are exactly those expressions obtained with finitely many applications of the previous two steps.

Equivalently, we may define these two sets of terms as intersections of all the sets containing all the constants (in and , respectively) and variables, and fulfilling the above condition 2. Usually, we delete outer brackets, i.e., those obtained by the last application of step 2 in the process of forming a term.

If and are terms over (or over ) of the same order , then is an identity over (over ) of the order .

Let be an identity over or an identity over and let be all constant terms and let be all variables appearing in and/or .

By and we denote the terms obtained from and by replacing with a constant of the same order for , as well as the values of these terms when ∘ is interpreted either as the partial operation of , for the terms over , or by interpreting ∘ as the partial operation of , for terms over .

We say that an identity over is true in a fuzzified matrix space in valuation if the following is true:

This means that the level of existence of the solution and the level of similarity of the left and the right sides of the evaluated expressions have to exceed the level of existence of the equation itself, measured by the level of existence of the constants appearing in the equation. For simplicity, here the indices in E and are not written; they are equal to the order of and to the corresponding orders of and .

In the sequel, we consider identities that are similar to one another, having an analogous arrangement of variables, constants, and operations. Therefore, we need to define what it means for two terms and , each of which is a term over or over for some , to be of the same type. We do this in an inductive manner.

The relation that is to be of the same type in the family of all terms over and is defined as the intersection of all the equivalence relations on the union of the sets of terms over and over for all , such that:

- (i)

- If A and B are constants of the same order, they are of the same type (here also, a constant from is of the same type as a constant over of the same order; hence, some terms from are of the same type as terms over ).

- (ii)

- If and , as well as and , are of the same type, and the terms and are defined, then they are of the same type.

The set of all equivalence relations fulfilling (i) and (ii) is nonempty—we can take the full relation, in which any two terms are related.

Thus, the intersection of all the equivalence relations fulfilling (i) and (ii) exists, and since the intersection of any set of equivalence relations is also an equivalence relation, the relation “to be of the same type” is an equivalence, and thus a reflexive and nonempty relation on the union of the sets of terms over and for all . Let us call its classes types of terms. Let us denote the type containing a given term T by .

We say that identities and are of the same type if . It is straightforward that the relation "to be of the same type" is an equivalence relation in the set of all identities. Classes of that relation are called types of identities.

As an equivalence class, a type of identity is determined by any identity belonging to it and may be written as .

Also, we say that an identity is of the type if it belongs to the class .

Some simple types of identities are described in the following example.

Example 3.

Let be fixed natural numbers.

- (1)

- Identities of the form , where A is a constant of the order , and C is a constant of the order and X is a variable from , form a type of identity; i.e., the set of all such identities over and is a type of identity.

- (2)

- Identities of the form , where B is a constant of the order , and C is a constant of the order , and Y is a variable from , form a type of identity; i.e., the set of all such identities over and is a type of identity.

3.3. Generalized Matrix Equation

Let be a partial matrix groupoid. An identity over containing constants and also some variables , is called an equation over . Note that ∘ in and is interpreted as the partial operation ∘ in . We also write . By the type of an equation over , we simply mean its type as an identity.

Let be an L-valued matrix space over , and the corresponding algebraic structure we have defined in Section 3.1.

We denote by the class of in , where is the order of A.

An identity over containing constants from the universe of and also some variables , is called an equation over . Here, ∘ in and is interpreted as the partial operation in . We also write . By the type of an equation over , we simply mean its type as an identity.

In the following definitions and theorems, we write and instead of and , and also and instead of and , whenever m and n are arbitrary or not known.

We say that an equation over containing constants is weakly solvable in if there are such that the identity is true in the valuation ; i.e., if

for some .

We say that is a weak solution of the equation in the fuzzified matrix space .

We relate the weak solvability of equations over the partial matrix groupoid in a fuzzified matrix space to the solvability of the corresponding equations over the related quotient structure .

As for the solvability in , we define it in a usual way. Namely, we say that an equation over is solvable in , if there is an ordered t-tuple of constants in , such that the equality

is true, when ∘ in and is interpreted as . We also say that is a solution to the equation in .

In order to investigate relationships between weak solvability of equations over in an L-valued matrix space and the solvability of some related equations over , we define a sort of projection of a term T over in an L-valued matrix space .

If , where is the set of all constants occurring in a term T over , the p-projection of in an -valued matrix space is an expression derived from T by replacing every with and ∘ with , as defined above. We denote the projection by .

Using the definition of the projection and the definition of , we obtain the following lemma.

Lemma 2.

Let be an L-valued matrix space over a partial matrix groupoid , and a term over containing t variables . If every constant in T belongs to for some and if is an ordered set of matrices, each one belonging to , for some , such that is of the same order as for , then , for some and .

Proof.

We prove this by induction on the complexity of the term.

For a constant or a variable, the assertion of the lemma holds by the definition of the projection.

If the assertion of the lemma holds for and , we prove that it holds also for .

Let be an ordered set of matrices, each being a matrix of the same order as and a matrix of the same order as —for and —then

Thus, we have proved the induction step. □

Theorem 1.

Let be an L-valued matrix space and an equation over . All the equations over of the type are weakly solvable in the L-valued matrix space if and only if for every , all the equations over of that type are solvable in .

Proof.

Suppose that all the equations over of the type are weakly solvable in the L-valued matrix space. Let t be the number of variables occurring in . Let and be an equation over of the type . It also has t variables.

Every constant in and is of the form , where is a matrix. Replacing every constant in and with some matrix belonging to the equivalence class denoted by that constant, we obtain an equation over —let us say —of the same type as —having t variables. This equation is—by assumption—weakly solvable in the L-valued matrix space. Let be the set of constants in that matrix equation and be a weak solution to it.

Now,

Since every is in , we have that for every ; thus . Herefrom, ; thus for ; also and .

Now, using Lemma 2, we have

Here, and contain a constant for every matrix A contained in and ; such a matrix A is previously chosen as a representative of its -class occurring in or ; therefore, and become and when ∘ in them are replaced with . Since = , we have proved that the initial equation is solvable in .

To prove the converse, suppose that for every , all the equations over of the type have at least one solution. Let be an equation over . Let be the set of all constants contained in and , and let . Now, replacing every by , we obtain the equation over of the same type , which by assumption has a solution, let us say ; here, for every . Since and become and when ∘ in them are replaced by , we have that , and thus by Lemma 2 we have

, so . Thus:

and has a weak solution and is weakly solvable. □

Taking the types described in Example 3, we obtain, as special cases and as corollaries of Theorem 1, Theorems 1 and 2 from [15].

Corollary 1.

Let be an L-valued matrix space and .

- (1)

- All of the equations of the form —where and —are weakly solvable over the L-valued matrix space if and only if for every all of the equations of the form —where and —are solvable in .

- (2)

- All of the equations of the form , where and , are weakly solvable over the L-valued matrix space if and only if for every all of the equations of the form , where and , are solvable in .

We give some more applications of Theorem 1 to some other special types of equations.

Example 4.

For a fuzzified matrix space , and we have the following.

- (1)

- All the equations of the form , where and X is a variable of the order , are weakly solvable in the fuzzified matrix space if and only if all the equations of the form , where are solvable in .

- (2)

- All the equations of the form , where and Y is a variable of the order , are weakly solvable in the fuzzified matrix space if and only if all the equations of the form , where are solvable in .

We could also generalize another result from [15], allowing us to test weak solvability of a single equation over in a fuzzified matrix space by the solvability of the corresponding equation over , for a suitably chosen . Namely, the following theorem generalizes Theorem 3 from [15].

Theorem 2.

Let be an L-valued matrix space over a partial matrix groupoid and an equation over . Let be the set of constants contained in and/or , and let . The equation is weakly solvable in the L-valued matrix space if and only if the equation over that we obtain from it by replacing every constant with its class in is solvable in .

Proof.

Let be weakly solvable in the L-valued matrix space

, and let be the equation over , derived from by replacing every constant by , where .

First, suppose that is weakly solvable. Let be a weak solution to , which means that

Since for all , we have ; thus, ; by Lemma 2, , . By the above inequation, and . By Lemma 2:

= .

, become , , respectively, when ∘ in them are replaced with ; thus, we have proven that is a solution to the equation and, consequently, is solvable in .

To prove the other implication, suppose that is solvable in , and let be a solution to . and become and , when ∘ in them are replaced with ; since is a solution to , we have . By Lemma 2:

= , so .

Since for , we have and . Finally,

and has a weak solution and is weakly solvable. □

Applying this theorem to the linear equations and , we obtain the following corollary, equivalent to Theorems 3 and 4 from [15].

Corollary 2.

Let be an L-valued matrix space, and , , and .

- (1)

- The equation —where X is a variable of the order —is weakly solvable in the L-valued matrix space if and only if the equation , where , is solvable in .

- (2)

- The equation —where Y is a variable of the order —is weakly solvable in the L-valued matrix space if and only if the equation , where , is solvable in .

Example 5.

Let , and let be the space of matrices over the ring . Let ∘ be the usual matrix product: if , , .

We say that, for and , two matrices of the order are congruent modulo k if for all we have (mod k). We write (mod k).

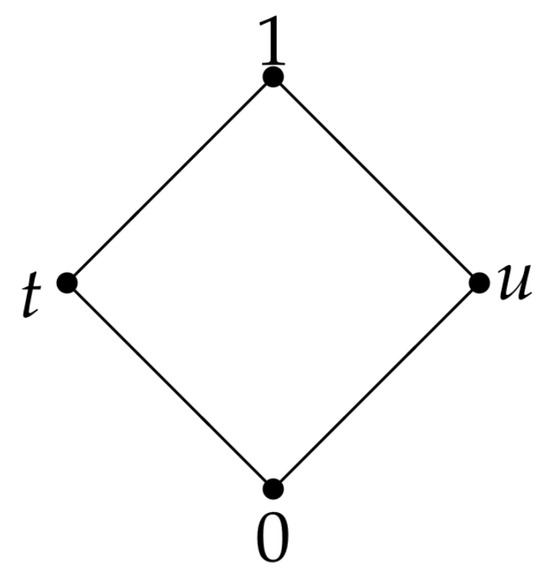

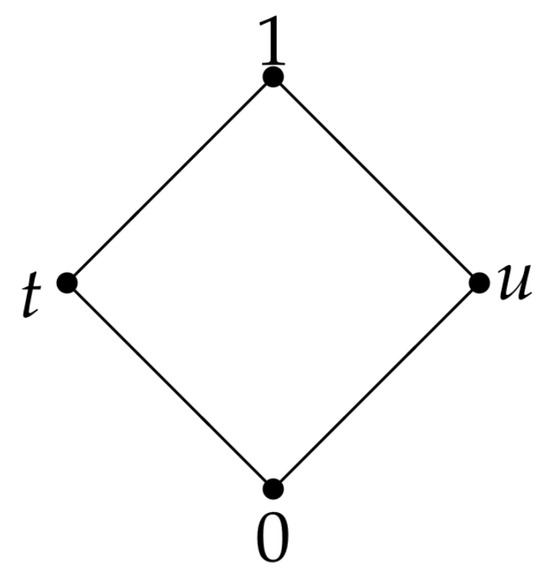

Let be a four-element lattice in Figure 3, and let and for all :

Figure 3.

A lattice L.

For any , is a symmetric and transitive fuzzy relation, i.e., it is a weak L-valued equivalence relation. Moreover, it is compatible with ∘.

Thus, is a matrix space. Let us describe the quotient structure for all :

: and , so is a one-element set for all . Thus, is isomorphic to , where ∘ is a partial operation on , defined for iff , in which case .

: and , for all , so is isomorphic to the set of matrices over the ring , where , and are addition and multiplication modulo k, respectively, (multiplication of matrices is as usual).

or : is a set of matrices whose elements are divisible by k, while is the full relation on that set; thus (as well as ) is isomorphic to , where ∘ is a partial operation on , defined for iff , in which case .

Thus, for any fuzzified matrix A of the dimension , we may with certainty say that it exists; i.e., its level of existence in is 1 (because ), while it is similar to the level t to all the matrices whose elements are to its elements at the same position. It collapses in , , into the only element of , , , while in it is reduced to the matrix over , containing—instead of an element —its remainder when divided by k.

Consider the equation , where and .

We can easily see that this matrix equation is not solvable over the domain in the usual way.

Now, we want to determine whether the equation is weakly solvable.

We need to check the solvability of the equation , where .

For , we have .

For , we have , where .

Also, , where .

- is solvable in , namely, for , we have which is in the same equivalence class as under the equivalence ; therefore,

Thus, is weakly solvable in , if .

The matrix space we introduced fuzzifies a set of matrices with a partial groupoid structure (i.e., with the multiplication of matrices defined in a case when the standard multiplication is defined), in order to apply it to various cases of matrix multiplication, which can model, e.g., the composition of fuzzy relations and various other processes and transformations for which addition may not be defined or relevant. Matrix space preserves multiplication in the initial set of matrices by its very definition. But a set of matrices that we want to fuzzify does not, generally, include addition, and if it does, a necessary and sufficient condition for a matrix space to preserve addition would be that the existing addition is compatible—under the usually defined compatibility—with weak equivalences within all subsets of matrices of a given dimension. That is the case in our Examples 1 and 5.

In the sequel, we define the unique weak solvability of the equations over in an L-valued matrix space.

Let and be terms over . Let be the set of constants contained in and/or . We say that the equation is uniquely weakly solvable in an L-valued matrix space if it is weakly solvable and, for any two of its weak solutions and , we have

which is equivalent to

This means that a uniquely weakly solvable equation over may have several weak solutions, but they should be equal on the “level” . Therefore, we are able to test the unique weak solvability of an equation over in the quotient structure for , as we prove in the following theorem.

Theorem 3.

Let be an L-valued matrix space over a partial matrix groupoid and let be an equation over . Let be the set of constants contained in and/or , and let . The equation is uniquely weakly solvable in the fuzzified matrix space if and only if the equation we obtain from it by replacing every constant with its class in is uniquely solvable in .

Proof.

Let be the equation over we obtain from by replacing every constant with its class in , where .

First, suppose that is uniquely weakly solvable. By the proof of Theorem 2, if is a weak solution to , we have that for all and is a solution to . If is any solution to , by the proof of Theorem 2, we have that is a weak solution to ; thus, by the weak uniqueness we have , and .

Now, suppose that is uniquely solvable, and that is its unique solution. By the proof of Theorem 2, we have that is a weak solution to . Let be another weak solution to , by the proof of Theorem 2 we have for and is a solution to . By uniqueness, we have for , consequently . □

Example 6.

In Example 5, for , the equation is not uniquely weakly solvable, since for , both and , where and are solutions to . By the definition of in Example 5, we can note that , and hence the equation is not uniquely solvable.

But the equation , where is uniquely weakly solvable. Namely, it is weakly solvable, since is solvable, because and, thus . Let be a solution to ; since for all Y for which is defined, we have ; thus, any solution to the equation equals to .

We obtain, as corollaries to Theorem 3, assertions that are slightly reformulated Theorems 5 and 6 from [15].

Corollary 3.

Let be a partial matrix groupoid, , , and for some .

- (1)

- The equation over —where X is a variable of the order —is uniquely weakly solvable in a given fuzzified matrix space , if and only if the equation —where —is uniquely solvable in .

- (2)

- The equation over —where Y is a variable of the order —is uniquely weakly solvable in a given fuzzified matrix space , if and only if the equation —where —is uniquely solvable in .

Another corollary to Theorem 3 generalizes Corollary 1 from [15].

Corollary 4.

Let be an L-valued matrix space over a partial matrix groupoid . Let be an equation over . If for every all the equations over of the type are uniquely solvable in , then all the equations over of the same type are uniquely weakly solvable in .

3.4. Approximate Laws in a Fuzzified Matrix Space

Since a matrix product is usually associative, we define an analog of associativity in a fuzzified matrix space . The definition is similar to that of the definition of fuzzified associativity in E-fuzzy groups defined in [12].

We say that the fuzzified matrix space is weakly associative if for all and for all , the following holds:

Analogously, for any other law given by , where and are terms consisting of t variables , , we may define its weak analog in the fuzzified matrix space . For this purpose, we build the set of terms in the same way as in Section 3.2, except that we take a countable set of variables without a defined order. They represent just any element from a fuzzified matrix space or any of its quotient structures .

We say that the law is weakly satisfied in a fuzzified matrix space if, for all from the fuzzified matrix space for which and are defined, we have

Here, we omitted indices as they may vary and take any values such that and are defined.

Associativity, as well as any other law (e.g., commutativity, idempotency…), is cutworthy in a fuzzified matrix space. We prove it in the following theorem.

Theorem 4.

If is a fuzzified matrix space, and terms consisting of variables , then the following holds: is weakly satisfied in the fuzzified matrix space if and only if, for all , the equality is satisfied for all .

Proof.

Let be weakly satisfied in the fuzzified matrix space. Consider the following equality:

By Lemma 2 it is equivalent to and thus also equivalent to , which is true since ,…,, and thus for and .

To prove the converse, let be always satisfied, and let be matrices for which and are defined. Consider the inequality:

Taking , we have that ; by Lemma 2, we have that , i.e.,

□

Thus, we have proved that any law in a fuzzified matrix space is weakly satisfied if and only if the corresponding law in all the cut structures is satisfied.

Example 7.

In the Matrix space in Example 5, we may conclude that the associativity is weakly satisfied, because it is satisfied in all its quotient structures: in , , , associativity is trivially satisfied, and in it is satisfied, because it is isomorphic to the set of matrices over the ring .

In the Matrix space in Example 2, we conclude that all the laws are weakly satisfied, since all the cut-structures are trivial, i.e., all the matrices of a given dimension collapse into a single element.

4. Conclusions

We have proved that the weak solvability of the equations of any given type, defined in a natural way, is a cutworthy property; i.e., it is satisfied if and only if the equations of the same type are solvable in all the quotient structures. As for the unique weak solvability of the equations of any type, also defined in a natural way, it is satisfied if the equations of the same type are solvable in all the quotient structures .

As for the (unique) weak solvability of a single equation in a fuzzified matrix space, it is equivalent to the (unique) solvability of the corresponding equation over for a suitably chosen , which depends on the equation itself.

Theorems we have proved here concerning the (unique) weak solvability of equations and their types generalize all the Theorems from [15], which we obtain here as corollaries.

Since associativity is often satisfied in a set of matrices in which a multiplication is defined, we defined a sort of associativity in a fuzzy framework, in a fuzzified matrix space. A similar approach led us to the definition of an L-valued analog of any law defined using matrix multiplication. We have proved that any such law is cutworthy; thus, it can be tested in the quotient structures we defined.

It is reasonable to expect that matrix space would show more regularity and have additional properties if we move from this more general frame of lattice-valued matrix space to [0, 1]-valued matrix space. However, investigating those regularities and properties would require a whole new investigation.

In conclusion, our approach opens up possibilities for approximately solving equations or systems of equations of various types. Our method empowers us to seek out approximate solutions in instances where exact solutions do not exist. We can identify solutions that will make the equation true up to some equivalence. As we extend our research, we intend to investigate the practical applications of our approach, exploring its potential in real-world contexts. A limitation in our theoretical study is that the sensitivity analysis has not been performed. Sensitivity analysis would be essential when dealing with fuzzy logic, because it would be important that small variations do not influence the final solution. However, to our knowledge, there are no studies where the sensitivity analysis has been performed in the case of lattice-valued fuzzy logic. Since our manuscript is theoretical, our plan is to perform the sensitivity analysis in a further study with real applications.

Moreover, an important direction for future work is to investigate whether an efficient algorithm is available for solving the matrix equations associated with our approach, using the comprehensive overview provided in [38], or whether it will be necessary to design a new one.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.S. and A.T.; methodology, V.S. and A.T.; investigation, V.S. and A.T.; writing—original draft preparation, V.S. and A.T.; writing—review and editing, V.S. and A.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Science Fund of the Republic of Serbia, # Grant no 6565, Advanced Techniques of Mathematical Aggregation and Approximative Equations Solving in Digital Operational Research-AT-MATADOR. The authors also gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia (Grants No. 451-03-137/2025-03/200116, 451-03-137/2025-03/200125 & 451-03-136/2025-03/200125 & 451-03-136/2025-03/200029).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zadeh, L.A. Similarity relations and fuzzy orderings. Inf. Sci. 1971, 3, 177–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, A. Fuzzy groups. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 1971, 35, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filep, L.; Maurer, G.I. Fuzzy congruences and compatible fuzzy partitions. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1989, 29, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirci, M.; Recasens, J. Fuzzy groups, fuzzy functions and fuzzy equivalence relations. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2004, 144, 441–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goguen, J.A. L-fuzzy sets. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 1967, 18, 145–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negoita, C.V.; Ralescu, D.A. Applications of Fuzzy Sets to Systems Analysis; Interdisciplinary Systems Research Series; Birkhaeuser, Basel, Stuttgart and Halsted Press: New York, NY, USA, 1975; Volume 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, E. Resolution of composite fuzzy relation equations. Inf. Control 1976, 30, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavelka, J. On fuzzy logic II. Enriched residuated lattices and semantics of propositional calculi. Math. Log. Q. 1979, 25, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachunek, J.; Slezak, V. Bounded dually residuated lattice ordered monoids as a generalization of fuzzy structures. Math. Slovaca 2006, 56, 223–233. Available online: http://dml.cz/dmlcz/133054 (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Díaz-Moreno, J.C.; Medina, J.; Turunen, E. Minimal solutions of general fuzzy relation equations on linear carriers. An algebraic characterization. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2017, 311, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järvinen, J.; Kondo, M. Relational correspondences for L-fuzzy rough approximations defined on De Morgan Heyting algebras. Soft Comput. 2024, 28, 903–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budimirović, B.; Budimirović, V.; Šešelja, B.; Tepavčević, A. E-fuzzy groups. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2016, 289, 94–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krapež, A.; Šešelja, B.; Tepavčević, A. Solving linear equations by fuzzy quasigroups techniques. Inf. Sci. 2019, 491, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, J.; Serrano, M.L.; Šešelja, B.; Tepavčević, A. Omega-rings. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2023, 455, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, J.; Stepanovic, V.; Tepavcevic, A. Solutions of matrix equations with weak fuzzy equivalence relations. Inf. Sci. 2023, 629, 634–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, J. Minimal solutions of generalized fuzzy relational equations: Clarifications and corrections towards a more flexible setting. Int. J. Approx. Reason. 2017, 84, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, D.; Chakraverty, S. Solving the nondeterministic static governing equations of structures subjected to various forces under fuzzy and interval uncertainty. Int. J. Approx. Reason. 2020, 116, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanović, V.; Tepavčević, A. Fuzzy sets (in)equations with a complete codomain lattice. Kybernetika 2022, 58, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- di Nola, A.; Sessa, S.; Pedrycz, W. A Study on Approximate Reasoning Mechanisms via Fuzzy Relation Equations. Int. J. Approx. Reason. 1992, 6, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Shang, D. Fuzzy Approximate Solution of Positive Fully Fuzzy Matrix Equations. J. Appl. Math. 2013, 2013, 178209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gottwald, S.; Pedrycz, W. Analysis and synthesis of fuzzy controller. Probl. Control Infom. Theory 1985, 13, 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Gottwald, S.; Pedrycz, W. Solvability of fuzzy relational equations and manipulation of fuzzy data. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1986, 18, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrycz, W. Approximate solutions of fuzzy relational equations. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1988, 28, 183–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrycz, W. Numerical and applicational aspects of fuzzy relational equations. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1983, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanimirović, S.; Micić, I. On the solvability of weakly linear systems of fuzzy relation equations. Inf. Sci. 2022, 607, 670–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Give’on, Y. Lattice matrices. Inf. Control 1964, 7, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Qu, X.; Zhu, L. On pre-solution matrices of fuzzy relation equations over complete Brouwerian lattices. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2020, 384, 34–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćirić, M.; Ignjatović, J. The Existence of Generalized Inverses of Fuzzy Matrices. In Interactions Between Computational Intelligence and Mathematics Part 2; Studies in Computational Intelligence; Kóczy, L., Medina-Moreno, J., Ramírez-Poussa, E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 794. [Google Scholar]

- Stamenković, A.; Ćirić, M.; Bašić, M. Ranks of fuzzy matrices. Applications in state reduction of fuzzy automata. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2018, 333, 124–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, L.; Navarro, G.; Santos, E. Induced operators on bounded lattices. Inf. Sci. 2022, 608, 114–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragić, D.; Mihailović, B.; Nedović, L. The general algebraic solution of dual fuzzy linear systems and fuzzy Stein matrix equations. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2024, 487, 108997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Fu, R.; Shen, J. Inverses of fuzzy relation matrices with addition-min composition. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2024, 490, 109037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Jiang, H.; Liu, X. General strong fuzzy solutions of fuzzy Sylvester matrix equations involving the BT inverse. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2024, 480, 108862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanassov, K.; Gargov, G. Interval valued intuitionistic fuzzy sets. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1989, 31, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeevaraj, S. Ordering of interval-valued Fermatean fuzzy sets and its applications. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 185, 115613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Gupta, A.; Taneja, H.C. Interval valued picture fuzzy matrix: Basic properties and application. Soft Comput. 2023, 27, 14929–14950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padder, R.A.; Alqurashi, T.; Rather, Y.A.; Malge, S. Interval Valued Spherical Fuzzy Matrix in Decision Making. Eur. J. Pure Appl. Math. 2025, 18, 6095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Respondek, J.S. Fast Matrix Multiplication with Applications, 1st ed.; Studies in Big Data; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 166. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).