Abstract

We interpret the Narayana numbers combinatorially by having them count the number of tilings of an n-strip using squares and triominoes. Using this interpretation, we develop a collection of identities satisfied by the sequence of Narayana numbers. Additionally, these techniques are used to introduce the generalized Narayana numbers and the k-Narayana numbers and to prove corresponding identities.

Keywords:

Narayana numbers; combinatorial identities; genreralized Narayana numbers; k-Narayana numbers MSC:

05A19; 11B39; 10A35

1. Introduction

For as long as people have studied recursively defined sequences, they have attempted to find additional identities satisfied by the terms of these sequences. This includes famous sequences such as the Fibonacci sequence, the Lucas sequence, and the Catalan sequence, as well as many lesser-known sequences. Many different approaches to prove identities have been developed. For example, Egorychev’s book [1] contains investigations of the problem of finding integral representations for and computing finite sums and generating functions. These finite or infinite sums are obtained in closed form by reducing them to multiple one-dimensional integrals, most often to contour integrals. The theory of linear recurrences of several variables was developed by E.K. Leinartas [2,3].

We follow in their footsteps and develop identities for one such lesser-known sequence, the sequence of the Narayana numbers.

Fourteenth-century Indian mathematician Narayana Pandita introduced what is now called the Narayana sequence when he studied a cow and calf problem similar to the rabbit problem studied by Fibonacci. In the Narayana cow problem, there is originally one cow, and each cow gives birth to one calf each year, starting in their third year—see [4,5] for more details. If r is the year, then the Narayana problem can be modeled by the recurrence

The first few terms of the Narayana sequence are .

In the literature, there is a sequence which is also called the Narayana sequence, named after Canadian mathematician T. V. Narayana (1930–1987) who introduced it in the context of probability theory [6]. This sequence is defined by the numbers (sequence A001263 in [7])

where , also known as the Triangle of Narayana numbers. A q-analogue of these type of Narayana numbers was first studied by MacMahon [8], Article 495. As is standard in the literature, any future reference to the Narayana sequence refers to the Narayana cow sequence (sequence A078012 in [7]), not sequence A001263.

People have studied the Narayana numbers in order to find identities satisfied by these numbers using a variety of methods, such as combinatorial methods, group theory, generating functions, and matrix theory, to name a few [9,10,11,12,13,14]. The original Narayana sequence can be extended to negative indices; the only additional term we will need to consider is .

To have a combinatorial interpretation of the Narayana numbers, we need to show that they count something, i.e., that they represent the size of a set of objects. We may proceed as [15] does for the Fibonacci numbers. Let count the number of sequences of 1s and 3s that sum to r. For example, , since 4 can be created in the following 3 ways: , , and . The pattern is unmistakable; both begins and continues to grow as the Narayana numbers do. That is, for , satisfies . To see this combinatorially, we consider the first number in our sequence. If the first number is 1, the rest of the sequence sums to , so there are ways to complete the sequence. Similarly, if the first number is 3, then there are ways to complete the sequence. Hence, .

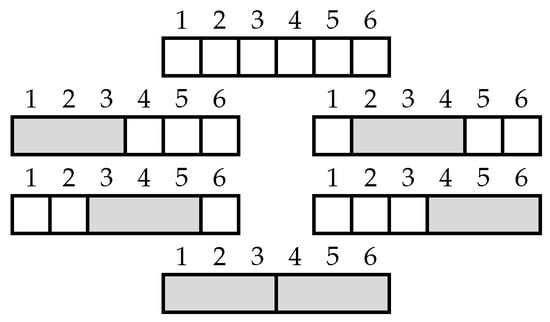

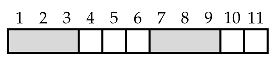

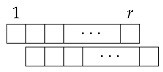

For our purposes, we prefer a more visual representation of . Thinking of a square as representing a 1, and a triomino as representing a 3, counts the number of ways to tile a board of length r with squares (□) and triominoes ( ). For simplicity, we call a board of length r an r-board. For example, here is a 6-board:

). For simplicity, we call a board of length r an r-board. For example, here is a 6-board:  . We let denote the collection of all such tilings of an r-board, and let for . We let count the empty tiling of the 0-board and define . For example, the set of all square–triomino tilings of the 6-board is given in Figure 1, showing .

. We let denote the collection of all such tilings of an r-board, and let for . We let count the empty tiling of the 0-board and define . For example, the set of all square–triomino tilings of the 6-board is given in Figure 1, showing .

). For simplicity, we call a board of length r an r-board. For example, here is a 6-board:

). For simplicity, we call a board of length r an r-board. For example, here is a 6-board:  . We let denote the collection of all such tilings of an r-board, and let for . We let count the empty tiling of the 0-board and define . For example, the set of all square–triomino tilings of the 6-board is given in Figure 1, showing .

. We let denote the collection of all such tilings of an r-board, and let for . We let count the empty tiling of the 0-board and define . For example, the set of all square–triomino tilings of the 6-board is given in Figure 1, showing .

Figure 1.

Set of all square–triomino tilings of the 6-board.

As the following theorem shows, is the sequence of Narayana numbers with its index shifted by one: .

Theorem 1.

For , .

Proof.  So, it is clear that , , , and .

So, it is clear that , , , and .

We need to show that satisfies the same recursive definition and initial conditions as . We first consider , and .

So, it is clear that , , , and .

So, it is clear that , , , and .To show that satisfies the same recursive definition at , we consider for . Now can be written as a disjoint union of , the tilings with a square as the last tile, and , the tilings with a last tile of a triomino. This implies that , since any tiling in consists of a tiling of an -board with an additional square. A similar agument results in .

Thus, for all . □

The purpose of introducing a combinatorial perspective to a sequence is to use the combinatorial approach to prove identities between terms of the sequence. There are two standard techniques used in such combinatorial arguments that we will also use, that of conditioning and the use of bijective mappings. For the identities in the next section, we obtain a proof of each identity by conditioning on the location of a given part of each tiling.

2. Elementary Identities by Conditioning

We first consider the sum of the first r terms of the Narayana sequence. This identity was given as part of Corollary 6.1 in [13].

Identity 1.

For ,

Proof.

To prove this result combinatorially, we need to consider the set of tilings of an -board that use at least one triomino. On one hand, there are tilings of an -board in total, one of which consists only of squares. This gives a total of tilings with at least one triomino.

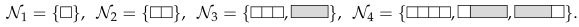

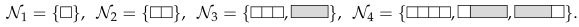

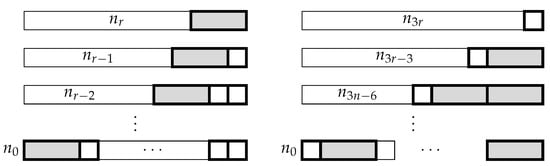

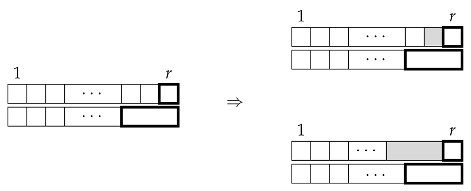

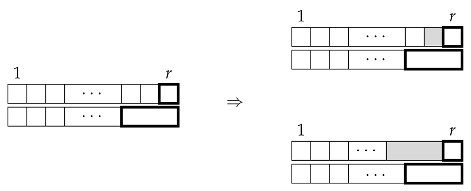

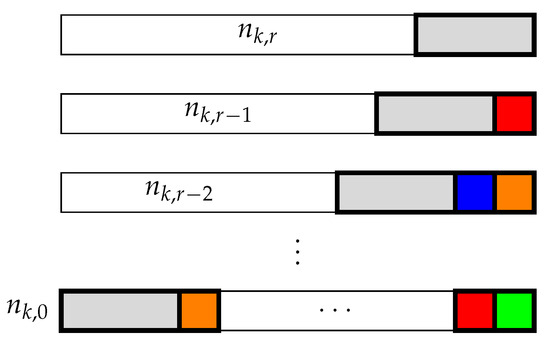

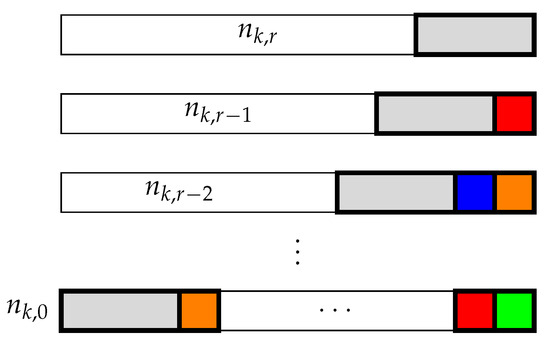

On the other hand, as shown in the left side of Figure 2, we can consider this set of tilings by conditioning on the location of the last triomino. If the last triomino covers cells , , and , the first i tiles can be covered in ways, while the remaining tiles must be covered in squares. Summing the possibilities over i ranging from 0 to r, this implies that . □

Figure 2.

Conditioning on the location of the last tile of a given type.

We next consider the sum of every third term in the sequence. Identities similar to this appear in [16].

Identity 2.

For ,

Proof.

We consider the number of tilings of a -board. By definition, there are such tilings.

Since the board has a length of , every tiling must have at least one square, and the last square in the tiling must occupy a cell of the form for , as shown in the right side of Figure 2. Therefore, there are tilings which have their last square on cell . Summing over the possibilities proves the identity. □

As with Fibonacci identities, many corresponding Narayana identities can be shown by using the notion of breakability at a given cell. We say that a tiling of an n-board is breakable at cell k, if the tiling can be decomposed into two tilings, one covering cells 1 through k and the other covering cells through n. On the other hand, we call a tiling unbreakable at cell k if a triomino occupies cells k, and , or cells , k and . From this definition, we can now show the following.

Identity 3.

For ,

Proof.

Consider the tilings of an -board. Every tiling is either breakable at cell m or is unbreakable at cell m. As shown in Figure 3, there are tilings that are breakable at cell m, tilings that are unbreakable at cell m and have a triomino occupying cells m, , and , and tilings which are unbreakable at cell m and have a triomino occupying cells , m, and , thus implying the identity. □

Figure 3.

Condition on breakability at cell m for Identity 3.

For the next two identities, we show how the Narayana numbers can be written as a sum involving binomial coefficients.

Identity 4.

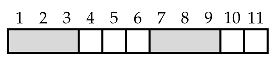

For ,

Proof.

Consider the number of tilings of a r-board. We condition on the number of triominoes. How many r-tilings use exactly i triominoes? For the answer to be nonzero, . Such tilings necessarily use squares and therefore use a total of tiles. For example, an 11-tiling that uses exactly five squares and two triominoes is given below.

In this tiling, the triominoes occur as the first and fifth tiles. The number of ways to select 2 of these 7 tiles to be triominoes is . Hence, summing up the number of triominoes considered, there are r-tilings. □

Identity 5.

For ,

Proof.

We consider the number of tilings of a -board. Note that a -tiling must include at least r tiles, because triominoes tile a -board. We consider the number of squares that appear among the first r tiles. If the first r tiles consist of i squares and triominoes, then these tiles can be arranged in ways and cover cells 1 through . The remaining board has length and can be tiled ways. Summing over the possible values of i proves the identity. □

A second common combinatorial approach to proving identities involves finding a bijection between two finite sets. The existence of such a bijection implies the sets have the same number of elements. Identities that can be proven using this technique are the focus of the next section.

3. Identities Using Bijections

In the proofs that follow, we consider the disjoint union of a number of for differing values of j and will use ⊔ to denote this. For ease of notation, we will use to represent .

We begin with an identity that shows can be written as a sum of three previous terms.

Identity 6.

For ,

Proof.

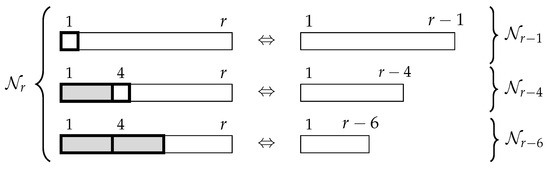

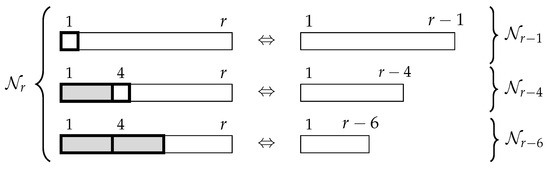

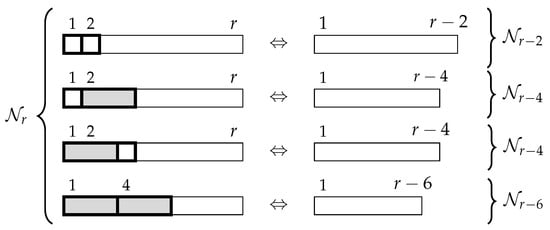

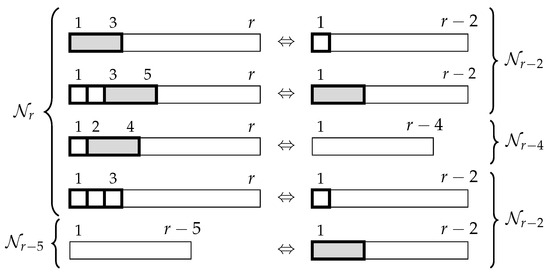

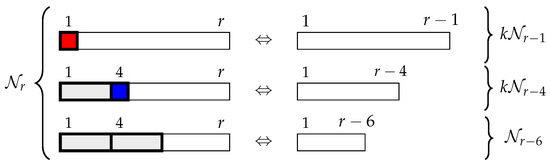

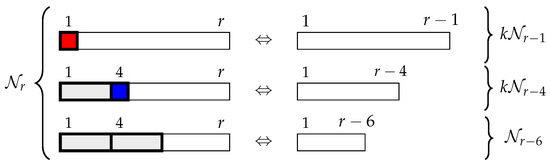

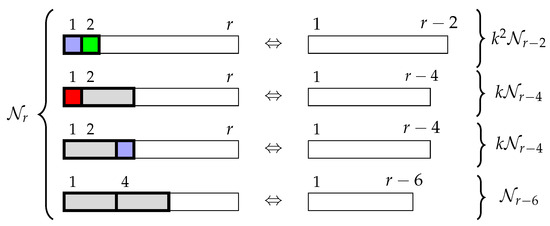

We build a bijection between and . We describe the bijection graphically in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Bijection between and for Identity 6.

In words, any r-tiling that begins with a square is mapped to the -tiling by removing that first square. On the other hand, if an r-tiling begins with a triomino, there are two possibilities: either the next tile is a square or the next tile is a triomino. By removing those first two tiles, the r-tiling is mapped, respectively, to an -tiling or to an -tiling. Notice that from any tiling belonging to , an r-tiling is obtained by adding, respectively, a first square if the tiling is an -tiling or a triomino followed by a square if the tiling is an -tiling, or finally two initial triominoes if the tiling is an -tiling. Since the resulting tilings are all different, the bijection between and is proved. □

Another identity equating to a sum of three previous terms follows.

Identity 7.

For ,

Proof.

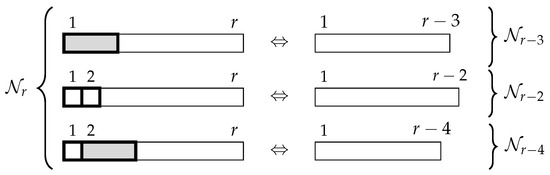

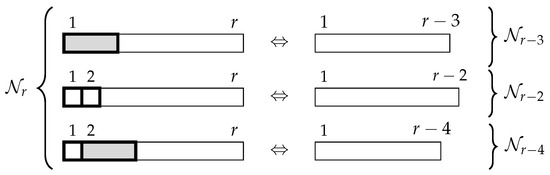

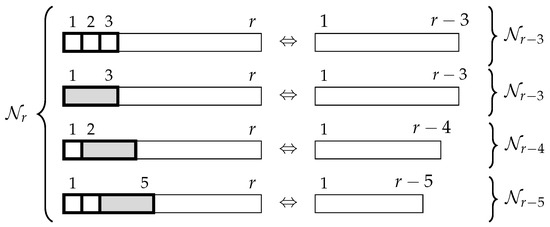

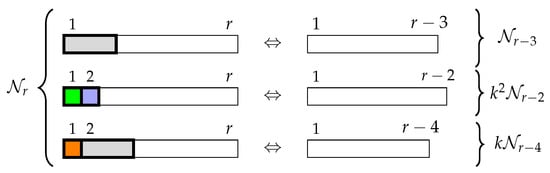

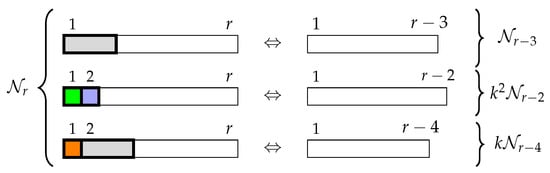

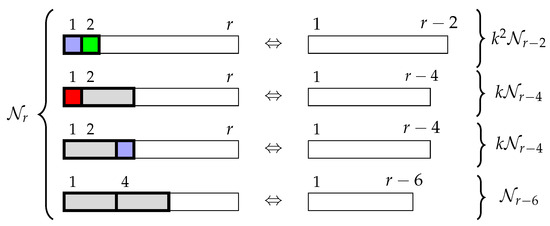

We build a bijection between and . We describe the bijection graphically in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Bijection between and for Identity 7.

In words, any r-tiling that begins with a triomino is mapped to an -tiling by removing that first triomino. On the other hand, if an r-tiling begins with a square, there are two possibilities: either the next tile is also a square or the next tile is a triomino. By removing those first two tiles the r-tiling is mapped, respectively, to an -tiling or to an -tiling. It is easy to see that this is a bijection between and . □

Similarly to the recursive definition of the Narayana numbers, the following two identities consider what happens when the first two or three tiles are removed.

Identity 8.

For ,

Proof.

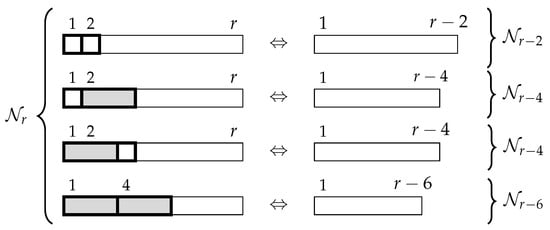

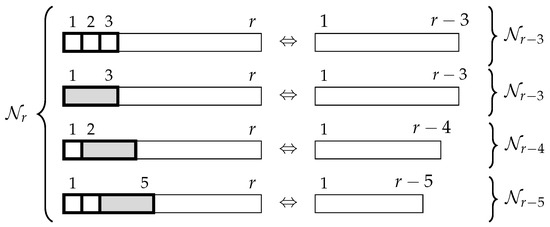

We build a bijection between and .

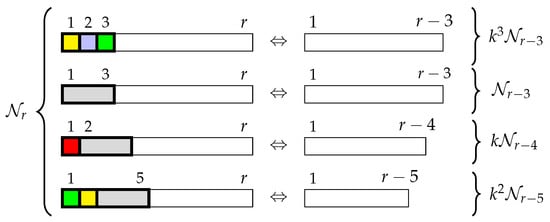

We describe the bijection graphically in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Bijection between and for Identity 8.

To explain this identity in words, we look at the two first tiles of any r-tiling. If they are two squares, when they are removed, an -tiling results. It the two first tilings are a triomino and a square (in either order), by removing them we obtain an -tiling. Finally, if the first two tiles are two triominoes, their removal results in an -tiling. It is easy to see that this is a bijection between and . □

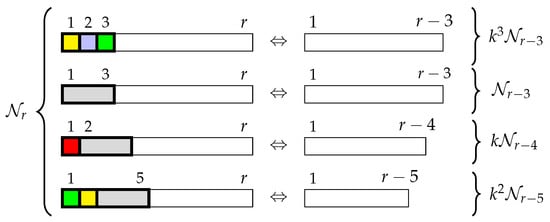

Identity 9.

For ,

Proof.

This identity follows as before by removing the first three tiles of any r-tiling. □

The last two identities are particular cases of the following general identity which may be proved by removing the first i tiles from an initial r-tiling and considering all the possible cases, that is, that j of those i tiles are triominoes.

Identity 10.

For ,

Additional identities for the Narayana numbers may be determined by using a bijection between two sets of tilings.

Identity 11.

For ,

Proof.

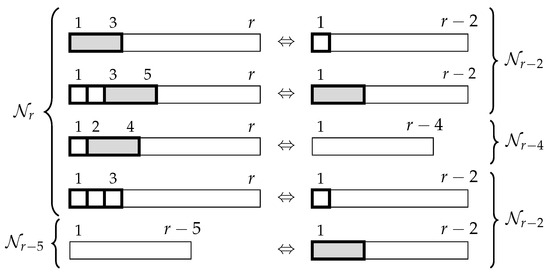

We build a bijection between and . We describe the bijection graphically in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Bijection between and for Identity 11.

To explain this identity in words, we look at up to the first three tiles of any r-tiling. If a tiling has a triomino as either the first, second, or third tile, we remove the beginning tiles up to and including the triomino. This obtains an -tiling, an -tiling, and an -tiling, respectively. Otherwise, the tiling begins with three squares. By removing these squares, we obtain another -tiling. □

Identity 12.

For ,

Proof.

The bijection between and is described graphically in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Bijection between and for Identity 12.

□

4. Products of Narayana Numbers

Before we consider identities for generalizations of the Narayana numbers, we introduce an identity regarding the product of consecutive Narayana numbers. In order to state this identity, we need to introduce the Padovan numbers.

Definition 1.

The Padovan numbers , are a recursively defined sequence given by , , , and . This sequence can be determined combinatorially by tiling r-boards with dominoes and triominoes. See [14] for more details regarding this combinatorial approach and some similar identities.

In order to consider the product of two consecutive Narayana numbers, we will tile two boards, one of length r (the top board) and the other of length (the bottom board) both starting at the same initial square (as shown below):

Given a tiling of these two boards, we say the tiling has a common break if there is a position in both boards that has a break between tiles. In the example below, the given tilings of a 6- and 7-board have common breaks at , , and .

Lemma 1.

There are ways to tile boards of length r and length with no common breaks.

Proof.

If we let be the number of ways to tile boards of length r and length with no common breaks, then it is straightforward to see that , , , and . We now consider the general case where . For any such tiling, the tiling of the bottom board must end in a triomino, otherwise there would be a common break at position r.

If the top board ends in a triomino, then there are ways to tile the remaining boards without any common breaks. On the other hand, if the top board ends in a square, then there are ways to tile the remaining boards without any common break (The role of the top board and bottom board switch in this case.)

Thus satisfies the same initial and recursive definitions of . □

With this lemma, we can now show the following.

Theorem 2.

For any ,

Proof.

There are different ways to tile both an r-board and an -board. We now condition on the location of the last common break in the tilings. From the lemma, there are ways to tile the boards without a common break. Suppose that a tiling has its last common break at position k, for . There are a total of ways to tile the boards up to the last common break. Again, from the lemma, there are ways to tile the remaining squares without adding an additional break. Thus there are a total of ways to tile the boards so the last common break occurs in position k. Adding up the possibilities proves the theorem. □

In a similar manner, by considering two r-boards, we can obtain a new identity for the square of a Narayana number.

Lemma 2.

There are ways to tile two r-boards with no common breaks.

Proof.

Given any tiling of two r-boards, the final tile in one board must be a square while the other is a triomino. By multiplying the result by 2, we can assume, without loss of generality, that the first tiling ends in a square while the second ends in a triomino. We then consider the possibilities of the second to last tile in the first board (as shown below):

The first case corresponds to tilings of an and board with no common breaks, of which there are . The second case corresponds to tilings of an and board with no common breaks, of which there are , thus proving the lemma. □

With this lemma, the following can now be shown.

Theorem 3.

For ,

Proof.

We consider the total number of ways to tile two r-boards. There are ways in total. There are different tilings with no common breaks. There are tilings with a last common break at position k, . Adding over all the possibilities proves the theorem. □

5. Generalized Narayana Numbers and Combinatorial Identities

As is the case with many recursively defined sequences, one way to generalize the Narayana sequence is to use any initial conditions, as defined below:

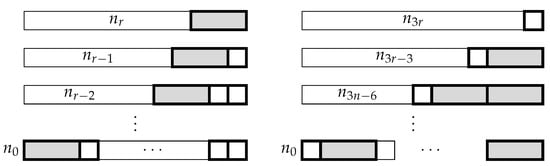

Definition 2.

A generalized Narayana sequence has three initial values , and for , .

The following theorem shows the combinatorial representation for the generalized Narayana sequence.

Theorem 4.

Let . be a generalized Narayana sequence with non-negative integer terms. For , counts the number of r-tilings, where the initial tiles is assigned a phase. There are choices for the phase of a triomino, choices for the phase of an initial square, and in the special case of , the tiles are covered with a domino that has phases.

Proof.

Let denote the number of phased r-tilings with and phases for initial triominos and squares, respectively. Suppose also that if , then there is a domino that covers the square with phases. Clearly , and . If we define , and we condition on the last tile (as in previous proofs) then it is clear that for . □

Many of the previously stated Narayana identities can be extended to generalized Narayana numbers. In fact, the proofs of these identities are identical to the proofs of the original identities, only with the additional consideration of the phase of the first tile. We will exhibit the proof of the first identity as an example. This identity is a generalized version of Identity 1.

Identity 13.

For ,

Proof.

We consider the number of phased tilings of an -board that use at least one triomino.

There are phased tilings of an -board. Excluding the “all square” tiling gives phased tilings with at least one triomino.

If we condition on the location of the last triomino, then there are phased tilings where the last triomino covers cells , and . This holds since cells 1 through i can be tiled in ways, cells , and must be covered by a triomino, and cells through must be covered by squares. Hence, the total number of phased tilings with at least one triomino is . □

The next two identities in this section are generalized versions of the identity mentioned in the parentheses. Their proofs are similar to the proofs of the original identities, with the phase of the initial tile also being considered.

Identity 14 (Identity 2).

For ,

Identity 15 (Identity 3).

For ,

Identity 16.

For ,

Proof.

We condition on the tile covering the first square. If it is a square, there are phases it can be with tilings of the remaining squares, while there are phases for a triomino and tilings of the remaining squares. □

Identity 17.

For ,

Proof.

We consider the number of phased -tilings that contain at least one square. There are such tilings minus the tilings consisting of only triominos. □

6. -Narayana Numbers and Combinatorial Identities

The k-Fibonacci numbers were introduced by Falcón and Plaza [17] in the context of the recursive application of two geometrical transformations used in the well-known four-triangle longest-edge (4TLE) partition in the context of the finite element method, where adaptivity of the mesh and the analysis of the approximation error are important issues to be addressed [18]. In this section, a new generalization of the Narayana numbers is introduced. It should be noted that the recurrence formula of these numbers depends on one integral parameter instead of two parameters. k-Narayana numbers were introduced by Ramirez and Sirvent [19] and also studied by Özkan, Kuloğlu, and Peters [20], where self-similarity inherent in planar Milich–Jennings centered flip graphs derived from the Narayana sequence were introduced.

Definition 3.

For any integer number , the k-th Narayana sequence, say , is defined recursively by

Particular cases of the previous definition are as follows:

- If , the classic Narayana sequence is obtained: .

- For , , which is Sequence A008998 in the Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences [7].

- If , then , which is Sequence A052541 in the Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences [7].

- For , , which is Sequence A052927 in the Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences [7].

6.1. Combinatorial Interpretation

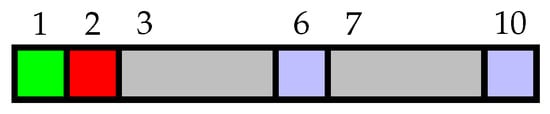

For the classic Narayana numbers, counts the number of ways to tile an r-board with squares and triominoes. In the same way as for k-Fibonacci numbers [21,22], we shall obtain an analogous combinatorial interpretation for the k-Narayana numbers. Define a coloured-square tiling to be a tiling of an r-board by coloured squares and non-coloured (or gray) triominoes. If there are k different colours to choose for the squares, then the number of coloured-square tilings for an r-board is precisely . For example, the 10-tiling in Figure 9 has two coloured squares followed by a triomino, then a coloured square, a triomino and finally a coloured square. In the figure, the number of colours for the squares is . In a standard abuse of notation, we will let also represent the set of all coloured-square tilings of an r-board.

Figure 9.

Example of a 10-tiling with 4 colour squares and 2 triominoes, where where the number of colours for the squares is .

As before, the advantage to considering the k-Narayana numbers combinatorially is that this interpretation can be used to prove identities involving these numbers. We use this interpretation to prove the coloured version of some of the identities proven earlier.

6.2. Elementary Identities by Conditioning

We start with the coloured version of Identity 1.

Identity 18.

For ,

Proof.

There are coloured-square tilings of an -board. There is one tiling which consists of only squares. Thus there are different coloured-square tilings of an -board that contain at least one triomino.

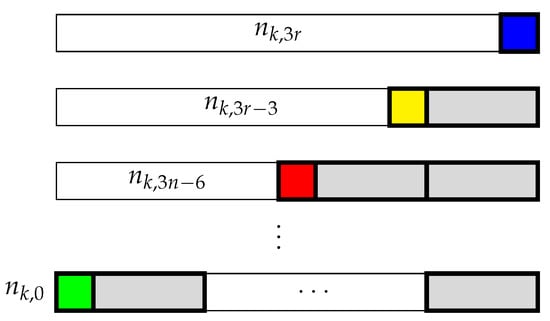

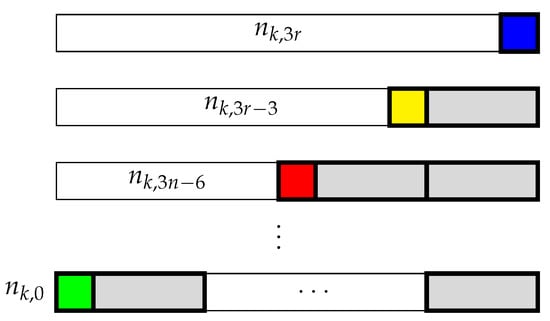

We condition on the location of the last triomino in the tiling (See Figure 10). If the the last triomino covers cells , , and , then the first i cells can be tiled in ways, and the cells through must be covered in squares. Thus, there are tilings where the last triomino covers cells , and . Hence, the total number of tilings with at least one triomino is . □

Figure 10.

Condition on the location of the last triomino for Identity 18.

Next is the coloured version of Identity 2.

Identity 19.

For ,

Proof.

There are coloured-square tilings of a -board. Since the length of the board is , there must be at least one square in any tiling. We consider the number of such tilings by conditioning on the location of the last square. See Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Condition on the location of the last (coloured) square for Identity 19. There are k possible colours for the last square.

There are k possible colours for this square. Since the board has a length of , the last coloured square must occupy a cell of the form for . There are tilings covering the first cells. Summing over the possibilities implies that . □

As with the classical Narayana numbers, the idea of breakability can be used to prove identities for the k-Narayana numbers. The following identity is the coloured version of Identity 3.

Identity 20.

For ,

Proof.

As with Identity 3, we condition on whether a tiling is breakable at cell m or not. Since this condition only involves a possible triomino at cell m or at cell , the proof is the same that for Identity 3. See Figure 3 on page 4. □

The next two identities generalize Identity 4 and Identity 5 respectively.

Identity 21.

For ,

Proof.

The condition to this identity is on the number of triominoes, as for the classic Narayana numbers in Identity 4 on page 4. There are r-tilings. For there to be a nonzero number of r-tilings using exactly i dominoes, it must be that . Such tilings necessarily use squares and therefore use a total of tiles. Note that for each one of those squares there are k possible colours, and hence the identity follows. □

Identity 22.

For ,

Proof.

We condition on the number squares appearing among the first r tiles as for the classic Narayana numbers in Identity 5 on page 4. There are -tilings. Note that a -tiling must include at least r tiles, because triominoes cover tiles, so a -tiling has at least one square. If the first r tiles consist of i squares and triominoes, then these tiles can be arranged ways and cover cells 1 through . Additionally there would be ways to colour the squares. The remaining board has length and can be tiled in ways, thus proving the identity. □

6.3. Identities Using Bijections

We now use the idea of a bijection between two finite sets to prove additional identities. The first is the coloured version of Identity 6.

Identity 23.

For ,

Proof.

We build a bijection between and . We describe the bijection graphically in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Bijection between and for Identity 6. There are k possible colours for each square.

In words, any r-tiling that begins with a (coloured) square is mapped to the -tiling by removing that first square. On the other hand, if an r-tiling begins with a triomino, there are two possibilities: either the next tile is a (coloured) square or the next tile is a triomino. By removing those first two tiles, the r-tiling is mapped respectively to an -tiling or to an -tiling. It is easy to see that this is a bijection between and . □

Identity 24.

For ,

Proof.

We build a bijection between and , as shown in Figure 13. Any r-tiling that begins with a triomino is mapped to the -tiling by removing that first triomino. On the other hand, If an r-tiling begins with a coloured square, there are two possibilities: either the next tile is also a coloured square, or the next tile is a triomino. By removing those first two tiles the r-tiling is mapped respectively to -tilings or to k-tilings (one for each colour choice). It is easy to see that this is a bijection between and . □

Figure 13.

Bijection between and for Identity 24.

Identity 25.

For ,

Proof.

We build a bijection between and . We describe the bijection graphically in Figure 14. This bijection is obtained by considering the two first tiles of any r-tiling. If a tiling begins with a two coloured squares, by removing these two coloured squares, we obtain an -tiling. It the first two tile are a triomino and a coloured square, in either order, their removal results in an -tiling. Finally, if the first two tiles are two triominoes, their removal results in an -tiling. Also it is easy to see that this is a bijection between and . □

Figure 14.

Bijection between and for Identity 25.

Identity 26.

For ,

Proof.

This identity follows Identity 9 by removing the first three tiles of any r-tiling and taking into account the k possible colours for each removed square. □

Identity 27.

For ,

This general identity may be proved in the same way as previous ones by removing the first i tiles from an initial r-tiling and considering all the possible cases, that is, that j of those i tiles are triominoes.

There are many more identities that can be proven using bijection between two sets. The next identity is the colour version of Identity 11.

Identity 28.

For ,

Proof.

We build a bijection between and . We describe the bijection graphically in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

Bijection between and for Identity 28.

To explain this identity in words, we consider up to the the first three tiles of any r-tiling. If a tiling contains a triomino within its first three tiles, we remove the tiles up to and including the triomino. Depending on the position of the triomino, we obtain an -tiling, k-tilings, or tilings. In the other situation, we remove the first three coloured squares. This results in -tilings. □

7. Open Problems

Although the combinatorial techniques used in this article have helped prove a number of identities for the Narayana numbers, there are additional identities for which we have been unable to find combinatorial arguments. We include finding a combinatorial proof of some of these well-known identities as a number of open problems. As an example of the interest of some of these identities, see [23], where the Catalan and the Vajda identities, which generalize the Cassini identity or Simson identity, for Fibonacci numbers are extended to their companion identities to cubic recurrences. Another generalized Simson identity to arbitrary-order recurrences with some conjectures may be found in [24].

We begin with Simson’s identity, as proven by Soykan ([13]):

Open Problem 1 (Simson’s Identity).

For any ,

In the same article, Soykan also determined an identity for the sum of the even terms and the odd terms of the Narayana numbers ([13,25]).

Open Problem 2.

For ,

Open Problem 3.

For ,

Finally, in Section 4, we found identities for the product of consecutive Narayana numbers and for the square of a Narayana number. It is natural to consider the square of a Narayana number written as the sum of products of consecutive Narayana numbers. By considering two r-boards, one offset by one square, one can use an argument similar to those used in Section 4 to find such an identity.

However in this case, we were unable to determine a closed form for a tiling of the two boards which do not have a common break. Finding such an identity is our last open problem.

Open Problem 4.

Suppose . Find a formula for as a sum of terms with as a factor.

These are just some of the open problems remaining for the Narayana numbers.

8. Conclusions

It is clear that the identities, and especially the proofs, within are based on the techniques discussed in [15]. In fact, the Narayana sequence was introduced as the 3-bonacci sequence. That book includes Identity 4 and its proof, as well as a few others regarding the Narayana (3-bonacci) sequence. Identity 4 has been included here for completeness’ sake.

The technique of combinatorial proof has been used throughout the paper to introduce some new identities for the Narayana numbers and their generalizations. This technique can be used to prove further identities with the Narayana numbers as well as other similar sequences. In addition to the open problems proposed before, we end by suggesting future directions on the use of combinatorial proofs for related issues, such as Narayana polynomials, asymptotic properties, or connections with continued fractions and generating functions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Á.P. and S.J.T.; Formal analysis, Á.P. and S.J.T.; Writing—original draft, Á.P. and S.J.T.; Writing—review & editing, Á.P. and S.J.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Egorychev, G.P. Integral Representation and the Computation of Combinatorial Sums; Translations of Mathematical Monographs; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 1984; Volume 59, 286p. [Google Scholar]

- Leinartas, E.K. Factorization of rational functions of several variables into partial fractions. Izv. Vyssh. Uchebn. Zaved. Mat. 1978, 22, 503–530. [Google Scholar]

- Leinartas, E.K.; Lyapin, A.P. On the Rationality of Multidimentional Recusive Series. J. Sib. Fed. Univ. Math. Phys. 2009, 2, 449–455. [Google Scholar]

- Allouche, J.P.; Johnson, J. Narayana’s cows and delayed morphisms. In Proceedings of the 3rd Computer Music Conference JIM96, Basse Normandie, France, 16–18 May 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cerda-Morales, G. Identities involving Narayana numbers. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1805.02255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayana, T.V. Sur les treillis formès par les partitions d’une unties et leurs applications à la thèorie des probabilités. Comp. Rend. Acad. Sci. 1955, 240, 1188–1189. [Google Scholar]

- OEIS Foundation Inc. The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences. 2011. Available online: https://oeis.org (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- MacMahon, P.A. Combinatorial Analysis, Volume 2; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1916; reprinted by Chelsea: London, UK, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, C.; Carrillo, J.; Machacek, J.; Sagan, B. Combinatorial interpretations of Lucas analogues of binomial coefficients and Catalan numbers. Ann. Comb. 2020, 24, 503–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, K.; Killpatrick, K. A combinatorial proof of a formula for the Lucas-Narayana polynomials. Discret. Math. 2022, 345, 113077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goy, T. On identities with multinomial coefficients for Fibonacci-Narayana sequence. Ann. Math. Inform. 2018, 49, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuloğlu, B.; Özkan, E.; Shannon, A.G. The Narayana sequence in finite groups. Fibonacci Q. 2022, 60, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soykan, Y. On generalized Narayana numbers. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Math. Mech. 2020, 7, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedford, S.J. Combinatorial identities for the Padovan numbers. Fibonacci Q. 2019, 57, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, A.; Quinn, J. Proofs That Really Count: The Art of Combinatorial Proof; The Mathematical Association of America: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bilgici, G. The generalized order-k Narayana’s cows numbers. Math. Slovaca 2016, 66, 795–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcon, S.; Plaza, Á. On the Fibonacci k-numbers. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2007, 32, 1615–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, G.F. Computational Grids: Generation, Refinement and Solution Strategies; Taylor and Francis: Abingdon, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez, S.J.; Sirvent, V.F. A note on the k-Narayana sequences. Ann. Math. Inform. 2015, 45, 91–105. [Google Scholar]

- Özkan, E.; Kuloğlu, B.; Peters, J.F. k-Narayana sequence self-Similarity. flip graph views of k-Narayana self-Similarity. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2021, 153, 111473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza, Á.; Falcón, S. Identities for generalized Fibonacci numbers: A combinatorial approach. Int. J. Math. Educ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 39, 563–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza, Á.; Falcón, S. Combinatorial proofs of Honsberger-type identities. Int. J. Math. Educ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 39, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballot, C.; Cooper, C. Some generalized Cassini identities. Fibonacci Q. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, A.G.; Srivastava, H.M.; Sàndor, J. Towards a new generalized Simson’s identity. Notes Number Theory Discret. Math. 2024, 30, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soykan, Y. On generalized co-Narayana numbers. Earthline J. Math. Sci. 2025, 15, 605–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).