Abstract

Impetigo is a highly contagious skin infection that primarily affects children and communities in low-income regions and has become a significant public health issue impacting both individuals and healthcare systems. A nonlinear deterministic model based on the transmission dynamics of skin sores (impetigo) is developed with a specific emphasis on the time delay effects in the infection and recovery processes. To address this complexity, we introduce a delay differential equation (DDE) to describe the dynamic process. We analyzed the existence of Hopf bifurcations associated with the two equilibrium points and examined the mechanisms underlying the occurrence of these bifurcations as delays exceeded certain critical values. To obtain more comprehensive insights into this phenomenon, we applied the center manifold theory and the normal form method to determine the direction and stability of Hopf bifurcations near bifurcation curves. This research not only offers a novel theoretical perspective on the transmission of impetigo but also lays a significant mathematical foundation for developing clinical intervention strategies. Specifically, it suggests that an increased time delay between infection and isolation could lead to more severe outbreaks, further supporting the development of more effective intervention approaches.

MSC:

34D20

1. Introduction

Skin sores, particularly impetigo, are highly contagious superficial skin infections that primarily affect children, with a marked increase in incidence in the late summer months [1]. Recent statistics indicate that impetigo affects approximately 111 million children in low-income countries and 140 million people globally at any given time [2]. Given the widespread nature of this infection, a deeper understanding of its transmission dynamics and effective control measures is crucial. Various scholars have developed mathematical models to study skin ulcer infections, reflecting the evolving landscape of research in this area [3,4,5,6,7,8].

Recently, researchers have made significant progress in mathematical modeling and stochastic models. For instance, Lu [9] proposed a simplified model of viral dynamics and immune response within the host. Alyobi [10] performed both qualitative and quantitative analyses of infectious disease dynamics with control measures. Additionally, Ref. [11] applies stochastic differential equations with the Wiener process to investigate the soliton solutions of the Chaffee–Infante (CI) equation. Furthermore, Ref. [12] analyzes the dynamics of pine wilt disease and its impact on forest ecosystems through mathematical modeling, numerical simulations, and analytical techniques. Although significant strides have been made in the mathematical modeling of dermatological disorders, as noted by Tanaka and Ono [13], the integration of experimental data, mathematical modeling, and data analysis presents both opportunities and challenges in enhancing skin research in the post-genomic era. Recent advancements have studied the duration and intensity of skin ulcer infections, such as the research by Lydeamore et al. [14], which provided valuable insights through stochastic representations of the SIS model. However, a common oversight in these traditional models is the failure to account for the time delays between the infection and recovery states.

The importance of time delays in modifying model dynamics and stability has been extensively documented. For instance, Galach [15] compared various tumor immunity models and identified significant changes in equilibrium stability with the introduction of time delays. Banerjee and Sarkar [16] qualitatively analyzed the solutions of a class of delayed differential equations and demonstrated the existence of a limit of system near the internal equilibrium point. Further studies, including those by Bi and Ruan [17], have demonstrated how multiple time delays can lead to Hopf bifurcations and chaotic phenomena in immune interaction models. Subsequently, Niu et al. [18] investigated Hopf bifurcation due to a time delay in a reaction–diffusion model and found that the positive steady-state solution of the system was destabilized, and Hopf bifurcation occurred as the time delay increased. Ruan [19] analyzed the nonlinear dynamics of a time delay interaction model by the tumor immune system with a time delay, a double time delay, and a triple time delay, respectively, and showed that the model may undergo Hopf, Fold–Hopf, and Hopf–Hopf branches, and even chaotic phenomena. Lydeamore et al [20] employed the Kaplan–Meier estimator to assess the age distribution of initial infections of skin ulcers, supplemented by the application of parameter exponential mixture models and Cox proportional hazards models for detailed analysis. Four years later, Fantaye et al. [21] investigated the endemic and epidemic equilibrium states of the skin ulcer transmission dynamics model by concurrently calculating the basic reproduction number . By 2024, Shoaib [22] proposed a dynamic transmission model for skin ulcers encompassing susceptible , infected , and recovered categories. Utilizing neural network models based on activation functions, they optimized training weights through mean-squared error modeling to describe and predict the dynamic behavior of the skin ulcer system more accurately; however, the specific impact of time delays in skin ulcer transmission models has not been systematically explored.

In the existing literature, only a standard SIR model for skin ulcers has been proposed, without studying the delays in the infection-to-recovery process. However, such delays often alter the dynamical properties of the model, changing equilibrium points or leading to phenomena such as bifurcations or chaos. This study aims to fill this gap by introducing a time delay parameter, denoted as , which captures the period from infection to recovery. By systematically analyzing the effects of a delay on skin ulcer transmission dynamics, this research not only extends traditional models but also enhances the accuracy of disease predictions and the effectiveness of intervention strategies. To emphasize the significance of time intervals in recovery more, our work contributes to a more nuanced understanding of skin ulcer dynamics, ultimately facilitating the improved control and management of this infectious disease and similar conditions.

The main purpose of this paper is to construct a delay differential equation (ODE) model for skin ulcers, investigating the stability of the model, the existence of Hopf bifurcation, and the stability of the bifurcating periodic solutions. The structure of the paper is organized as follows: In Section 2, we develop the DDE model based on the characteristics of skin ulcer propagation. In Section 3, we analyze the existence and stability of the equilibria of the skin ulcer model associated with time delays, as well as the existence of Hopf bifurcation. We calculate the critical time delay from infection to isolation and explore the dynamic properties of the model. In Section 4, we derive the normal form of Hopf bifurcation for the aforementioned model and analyze the stability of the bifurcating periodic solutions. In Section 5, we present simulation results to verify our analytical conclusions. Finally, Section 6 provides a summary of the entire paper.

2. Mathematical Modeling

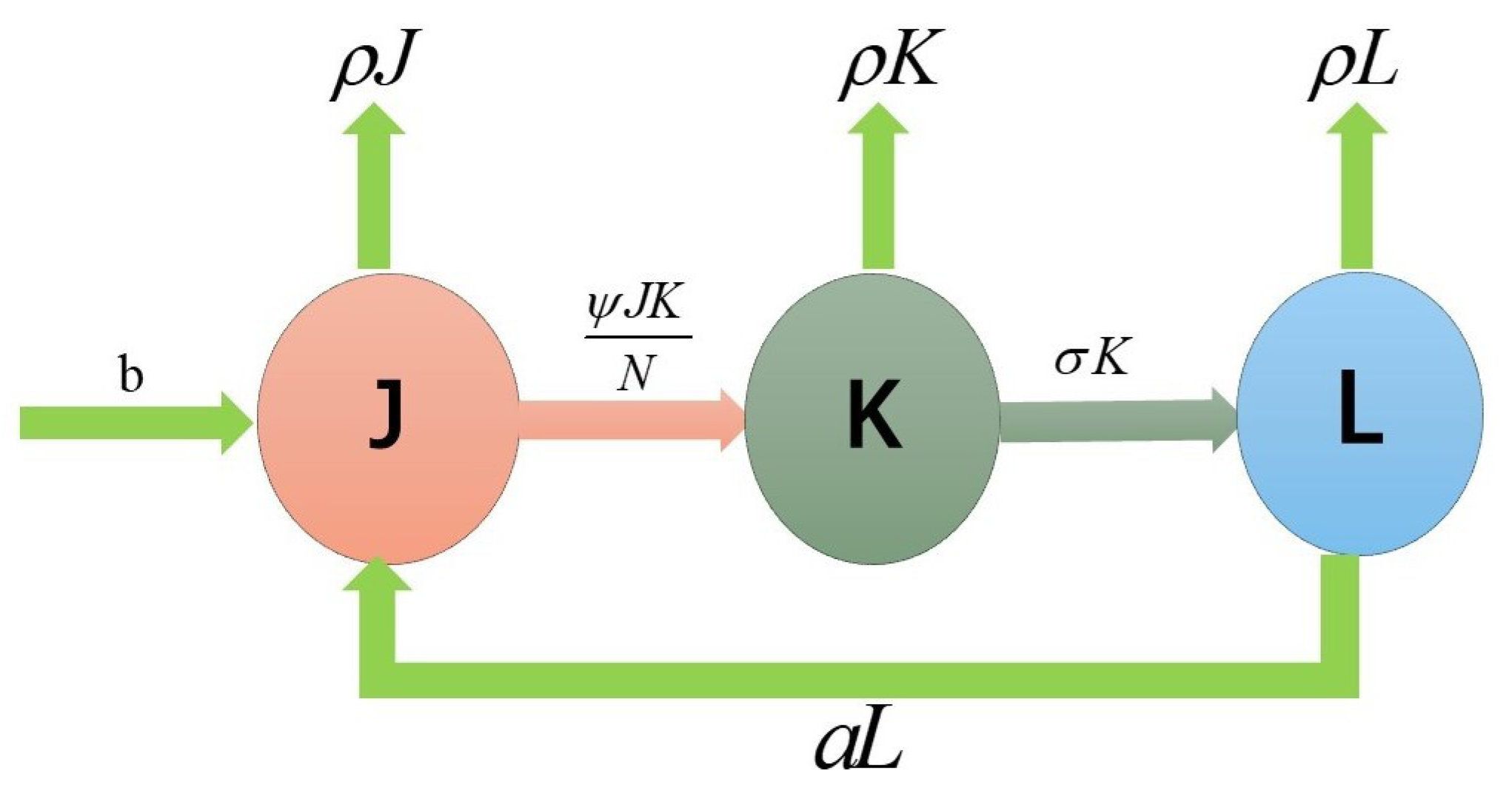

A mathematical model to describe the dynamics of skin ulcer propagation was constructed in [21]. Let be the total population composed by three parts: the susceptible population (), i.e., those who are at risk of being infected by the disease; the infected population () who have the pathogen in their organisms and are able to transmit the pathogen; and the recovered population () who have recovered from the disease. We assume b to be the positive recruitment rate in the susceptible population () and the positive natural mortality rate. The rate of infection of susceptible individuals in exposure to infected individuals depends on time, where is the effective contact rate, is the recovery rate and a is the susceptibility rate of recovering individuals (Figure 1 and Table 1).

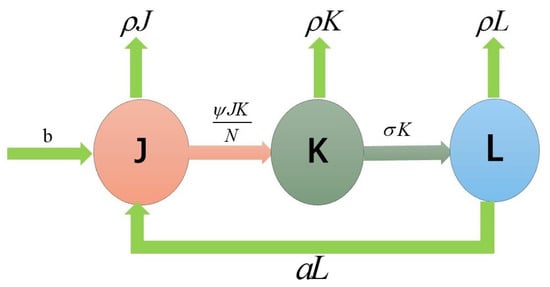

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the model.

Table 1.

Parameters of the model.

These large deviations between model predictions and actual recorded numbers stem from uncertainty in the latent model parameters. Thus, time delays are biologically important in epidemic modeling. We construct a DDE model for horizontal transmission by characterizing time delay from the infection period to the recovery.

The initial condition of system (1) is , where for and is the Banach space of continuous function mapping interval into . For system (1), .

According to the initial condition of system (1), we present a theorem addressing the nonnegativity and the boundedness of the solution to the system (1).

Theorem 1.

If , the solution to system (1) with is nonnegative and bounded when .

Proof.

First, we prove when under the initial condition of system (1).

We assume that is not always nonnegative for and make the first time that According to the second equation of system (1), we can obtain The two conclusions we obtain are contradictory.

Therefore, when . In the same way, when . The solution to system (1) is positive when .

Remark 1.

We prove that if , the solution to system (1) with is positive. It is not easy for us to prove that the solution to system (1) is positive when . However, according to our numerical simulation, we can find that when system (1) is stable, the solution to system (1) is always positive, which is not contradictory to the positivity of the solution to system (1).

3. Stability and Local Hopf Bifurcations

3.1. Existence and Stability of Equilibria

We take the basic reproduction number as usual for system (1). It is clear that system (1) has two equilibria:

As we know, for any equilibrium point ( or ) of system (1), the linearization of (1) at can be written as

And the characteristic equation of (3) at equilibrium is as follows:

To develop the following study, we assume

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

.

The stability of the equilibrium point for can be obtained by analyzing (4).

Theorem 2.

For , system (1) has a locally asymptotically stable equilibrium solution (or ) when (or ).

Proof.

From (H1), it can be shown that if , which implies that all the eigenvalues are negative. Consequently, equilibrium point is locally asymptotically stable.

Similarly, the characteristic equation of linearly transformed system (3) at equilibrium point is as follows:

where

The Routh–Hurwitz criterion indicates that system (3) is locally asymptotically stable if , and are all positive. Consequently, is locally asymptotically stable if . □

3.2. Existence of Hopf Bifurcation

The characteristic equation of linear system (3) for equilibrium when is as follows:

Let be a root of the following equation:

Putting into (9), it is possible to separate the real and imaginary parts of the resulting equation

Therefore, we obtain

From (10), there is

Thus, when . Since and , we can obtain and

where and are given in (11),

Let be the root of (12) satisfying We have the transversaality conditions

Thus, system (1) undergoes a Hopf bifurcation at equilibrium when

For the other equilibrium , when , denote by the root of the following equation:

where

If we insert it into the equation and separate the real part from the imaginary part, we obtain

Similarly to (11), there is

Set and add the squares of the two equations of (16)

where

We give another two assumptions.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

If (H2) is true, (18) has two positive roots and . If (H3) is true, (18) has a single positive root . For the sake of simplicity, substituting into (17) yields

where are given in (18) and

Note that since is always non-negative, can be obtained directly. However, the sign of depends on the parameters of (17), and must be calculated according to the value of .

Let be the root of (19) satisfying

If (H2) or (H3) is true and

where

To sum up, we have the following results.

Theorem 3.

- (1)

- Assuming that (H1) holds, equilibrium point is locally asymptotically stable when and unstable when ; system (1) undergoes Hopf bifurcation at when .

- (2)

- Assuming that (H1) does not hold and (H2) does, there exists an such that the equilibrium point is stable at and unstable at .

- (3)

- Assuming that (H1) does not hold and (H3) does, equilibrium point is locally asymptotically stable if and unstable if ; system (1) undergoes Hopf bifurcation at if .

4. Direction and Stability of Hopf Bifurcation

We have established the necessary conditions to ensure that system (1) undergoes Hopf bifurcation. In this section, we begin to analyze bifurcation properties. The method utilised is based on the normal form and the center manifold theory as presented in Hassard et al. [17]. For the sake of simplicity, we refer to the critical value , where . This is the value of at which the characteristic (8) and (15) have an eigenvalue . At this point, the system undergoes Hopf bifurcation at equilibrium , where .

By the dimensionless variation in t to , in addition to introducing the branching parameters and expanding the nonlinear terms by Taylor’s formula, model (1) can be written as

where

Consequently, system (20) can be transformed into a generalized differential equation on :

where .

We define

In accordance with the Riesz representation theorem, there exists a function , whose elements are bounded variation functions such that

for .

Indeed, we can choose

where is the Dirac delta function.

For , define

and a bilinear product

where and are adjoint operators. It is easy to know that are eigenvalues of and also eigenvalues of . Suppose that is the eigenvector of corresponding to . Similarly, let be the eigenvector of corresponding to , where

Thus, .

A similar computation procedure, as described in [22], based on the calculations presented in [23], leads to the determination of parameters that define the nature of Hopf branches.

where

Consequently, the following values can be computed:

Calculate the branch parameters according to (30). If , the Hopf bifurcation is supercritical (subcritical) and the bifurcating periodic solutions exist for ; the bifurcating periodic solutions are stable (unstable) if ; and the period increases (decreases) if .

5. Numerical Simulations

In this section, we select the following parameters: , N = 12,500, and . According to (2), (12,500, 0, 0), , it is evident that assumption (H1) is true and that equilibrium is locally asymptotically stable when . Nevertheless, equilibrium is not stable. Using MATLAB 2016a, we can obtain and .

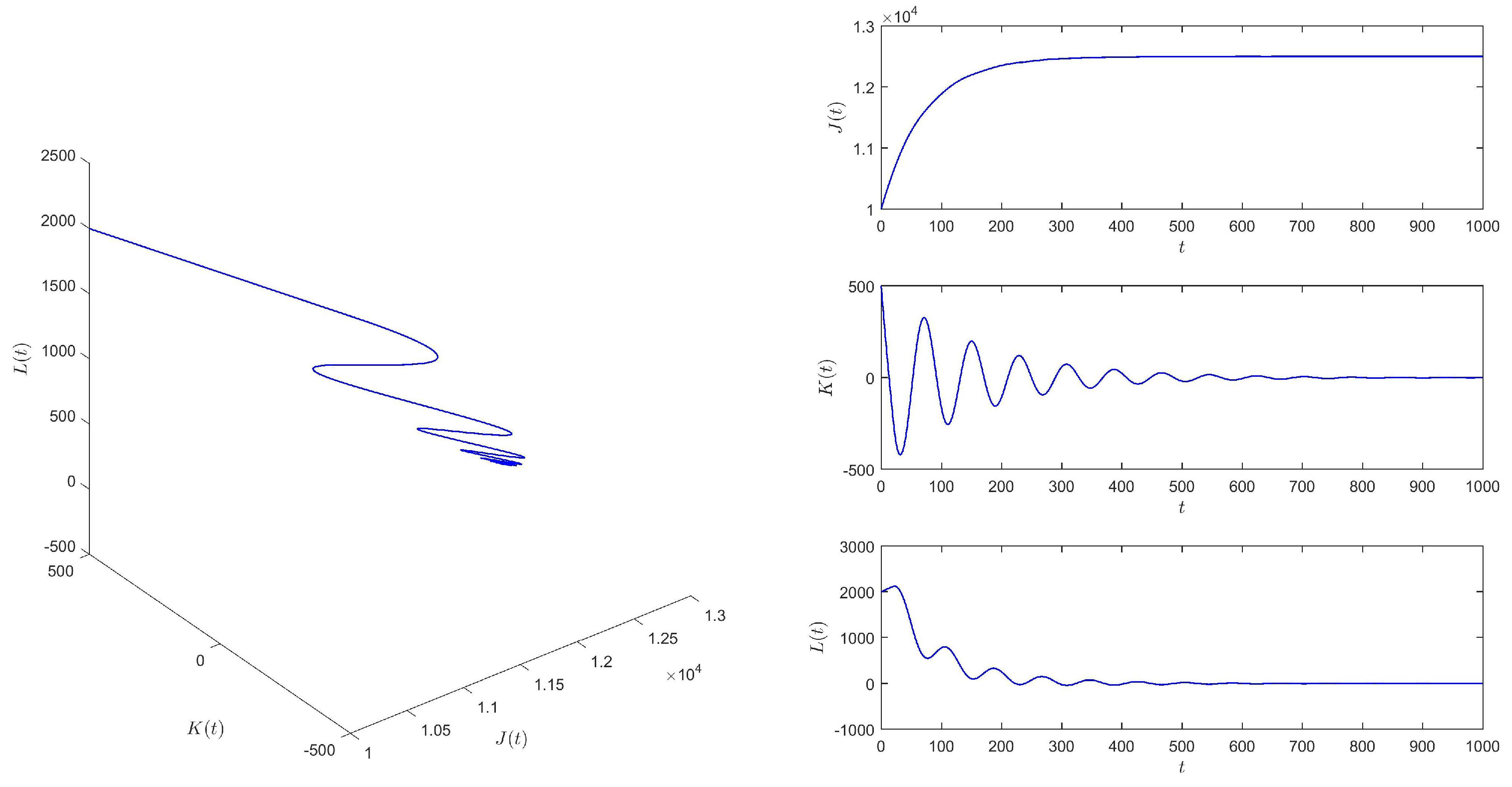

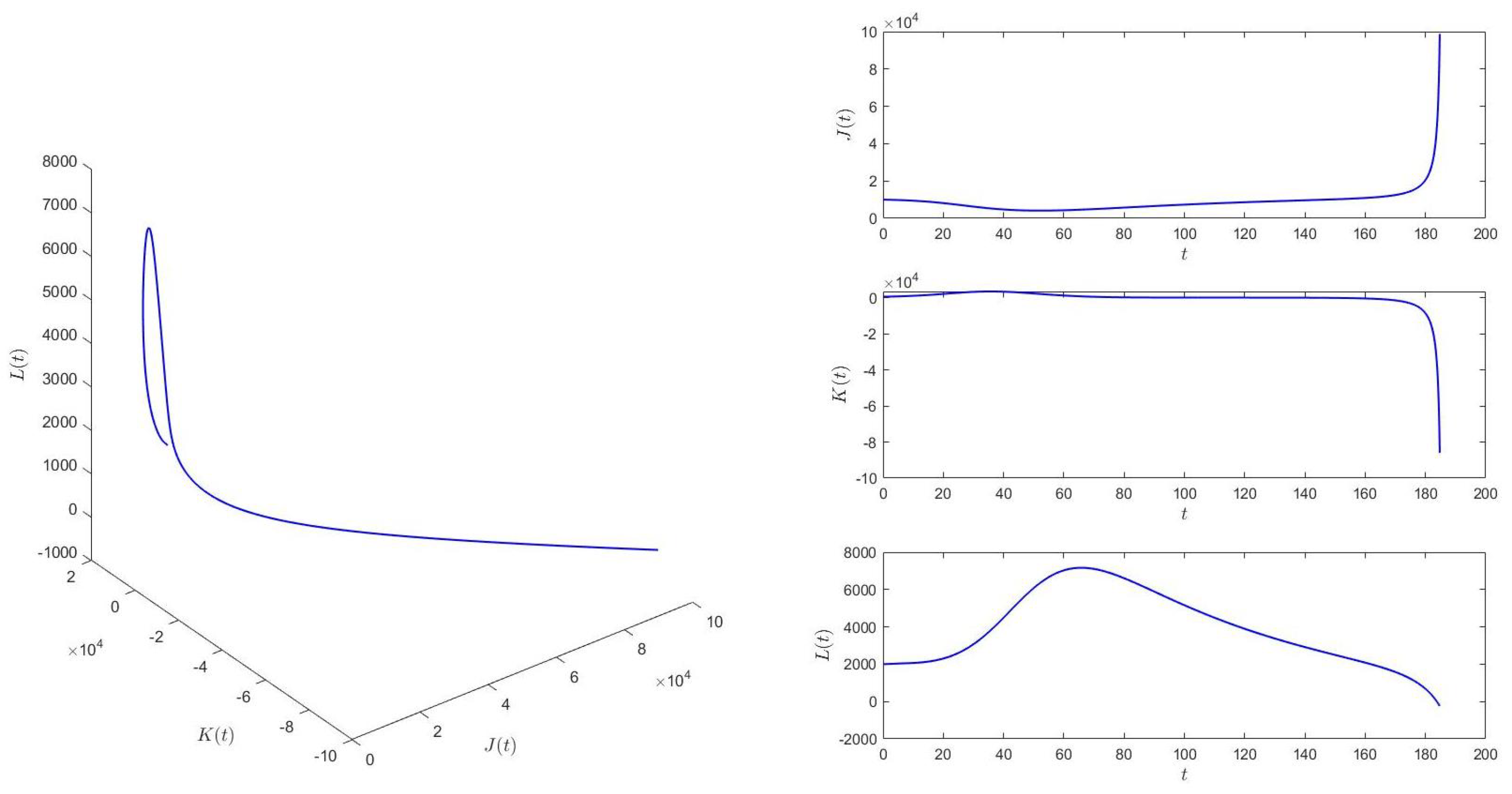

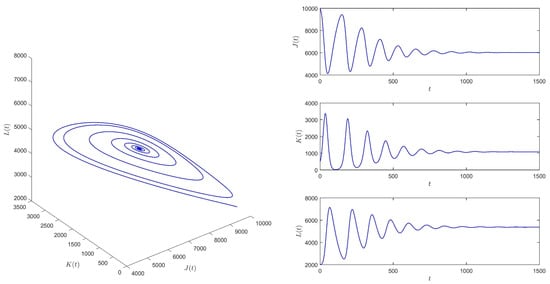

When , we choose the initial values (10,000, 500, 2000), and equilibrium of system (1) is locally asymptotically stable. See Figure 2. This means that if is larger than the critical value , the epidemic situation cannot be controlled into a stable state.

Figure 2.

When , equilibrium of system (1) is locally asymptotically stable.

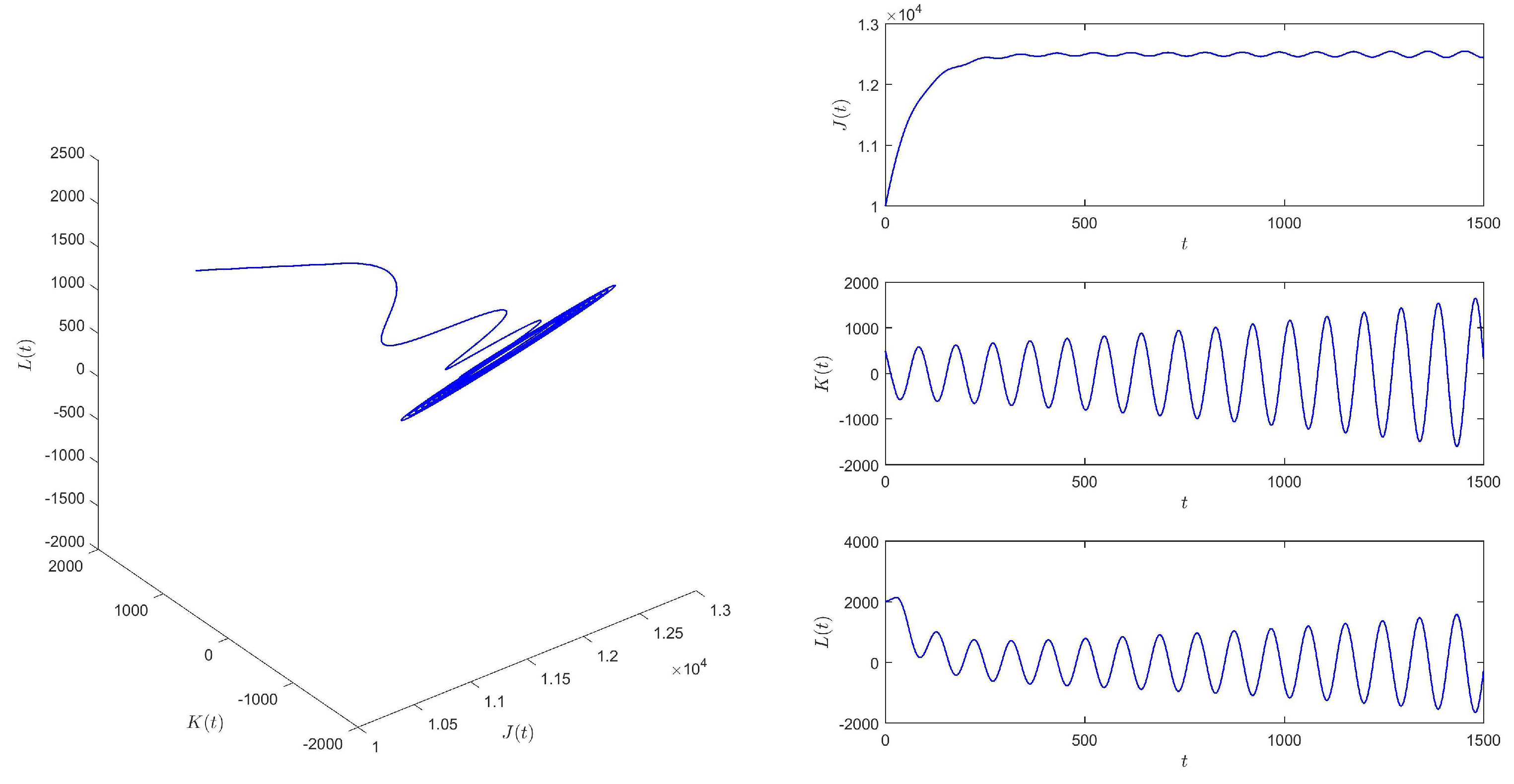

According to Figure 2 and Figure 3, we find that the time delay from infection to recovery has a great influence on the epidemic situation in , and with the increasing time delay, the epidemic situation will become increasingly severe.

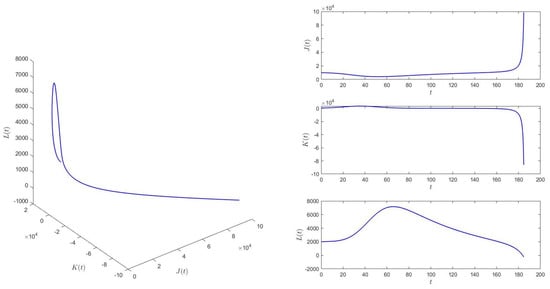

Figure 3.

When , equilibrium of system (1) is unstable.

When , we choose the initial values (10,000, 500, 2000), and equilibrium of system (1) is unstable. See Figure 3.

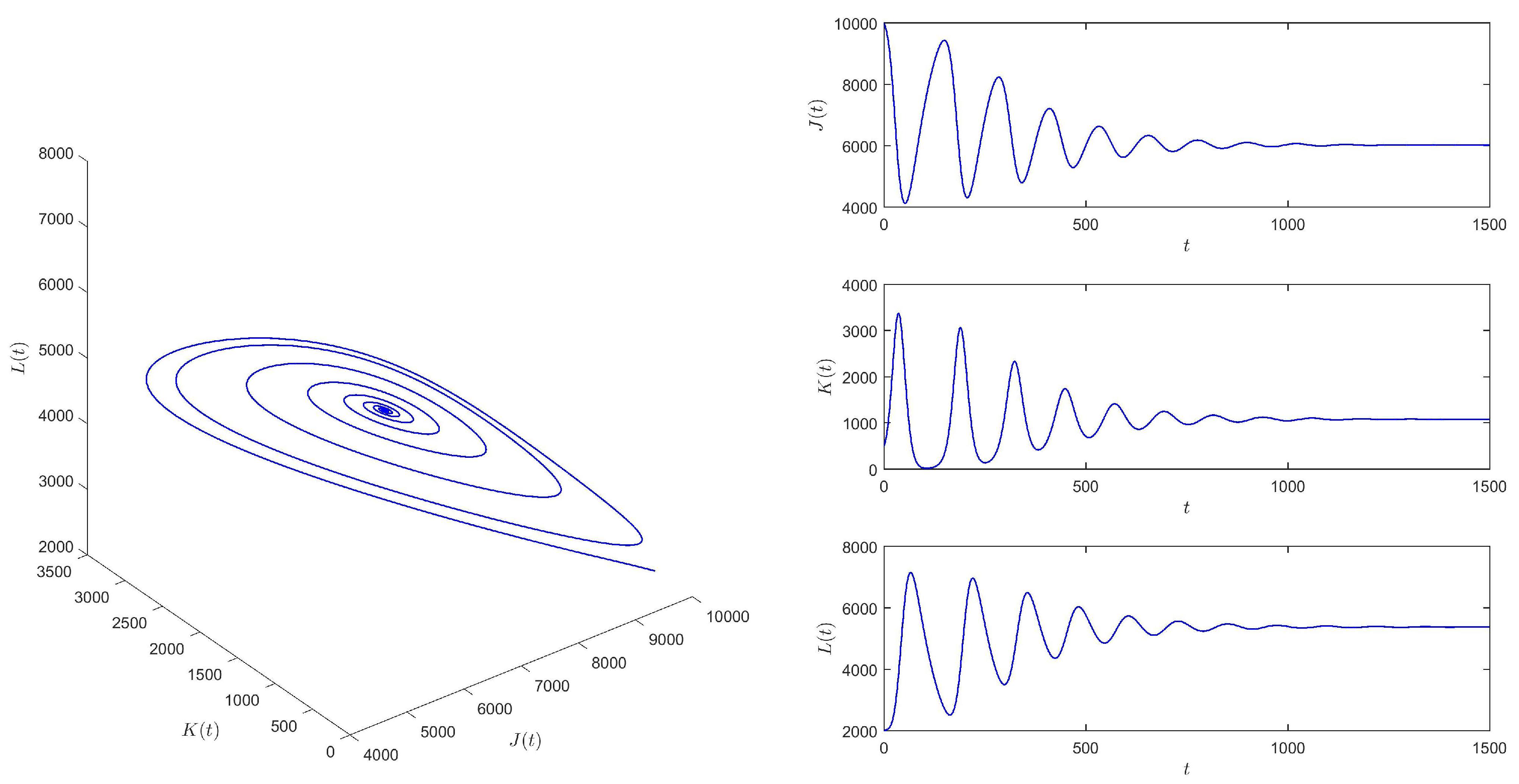

We choose another group of parameters, , N = 12,500, and .

According to (2), we obtain (10,000, 500, 2000), ,

. For this case, assumption (H1) does not hold and equilibrium is unstable. However, equilibrium is locally asymptotically stable when . By using MATLAB, we can obtain and

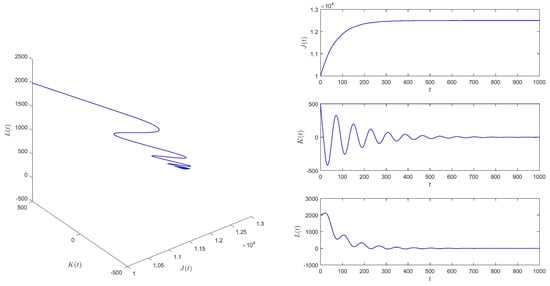

When , take the initial values , and then equilibrium of system (1) is locally asymptotically stable. See Figure 4.

Figure 4.

When , equilibrium of system (1) is locally asymptotically stable.

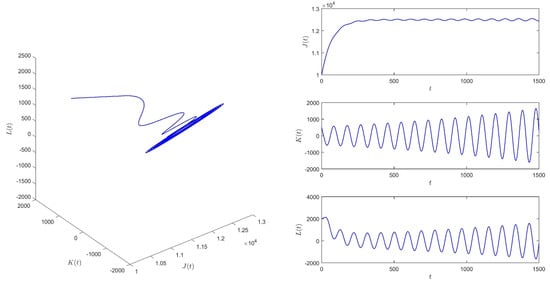

When and for initial values (10,000, 500, 2000), equilibrium of system (1) is then unstable. See Figure 5.

Figure 5.

When , equilibrium of system (1) is unstable.

Based on the numerical simulation results, it is observed that the smaller the delay , the better the control effect on the propagation of skin ulcers. The numerical results are consistent with this observation.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we developed a delay differential equation (DDE) model to explore the dynamics of skin ulcers. Our primary focus was on determining the existence and stability of equilibrium points, with particular attention given to the influence of time delays on these dynamics. We found that the severity of the outbreak tends to increase as the time delay between infection and isolation lengthens, highlighting the critical importance of timely interventions to control the spread of the disease. Furthermore, we examined the dynamical properties of the Hopf bifurcation associated with the two equilibrium states, which revealed the potential for periodic solutions that may emerge due to time delays. Numerical simulations supported our analytical results, providing strong evidence for the model’s validity and offering deeper insights into the complex interactions between time delays and disease dynamics. This study contributes valuable knowledge to the management of skin ulcer outbreaks, particularly by enhancing our understanding of how delays in isolation and treatment can impact disease transmission. By employing a delay differential equation (DDE) model, we underscore the pivotal role of time delays in predicting epidemic dynamics and shaping effective response strategies. Our findings emphasize the need for timely interventions, as delays in isolation and treatment can significantly worsen the severity of outbreaks. Public health authorities should, therefore, prioritize prompt isolation and treatment measures to mitigate the spread of the disease.

This study primarily investigates the delay from infection to recovery in the transmission process of skin ulcers. However, future research could extend to multiple delays, including those from susceptibility to infection and from infection to recovery. Additionally, the numerical simulation parameters used in this study were generated based on theoretical results rather than actual clinical data. Therefore, validating the research findings with clinical data would significantly enhance the value of this study.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, Y.W.; Writing—review & editing, T.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Millard, T. Impetigo: Recognition and Management. Pract. Nurs. 2008, 19, 432–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, A.C.; Mahe, A.; Hay, R.J.; Andrews, R.M.; Steer, A.C.; Tong, S.Y.C.; Carapetis, J.R. The Global Epidemiology of Impetigo: A Systematic Review of the Population Prevalence of Impetigo and Pyoderma. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawed, M.Y.; Tchepmo Djomegni, P.M.; Krogstad, H.E. Complex Dynamics in a Tritrophic Food Chain Model with General Functional Response. Nat. Resour. Model. 2020, 33, e12260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djomegni, P.M.T.; Tekle, A.; Dawed, M.Y. Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis HIV/AIDS Mathematical Model with Non-Classical Isolation. Jpn. J. Ind. Appl. Math. 2020, 37, 781–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agossou, O.; Atchadé, M.N.; Djibril, A.M. Modeling the effects of preventive measures and vaccination on the COVID-19 spread in Benin Republic with optimal control. Results Phys. 2021, 31, 104969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunday, U.E.; Chioma, I.S. Application of Optimal Control to the Epidemiology of Fowl Pox Transmission Dynamics in Poultry. J. Math. Stat. 2012, 8, 248–252. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, C.; Tao, N.; Zhu, Y. A Mathematical Model of Zika Virus and Its Optimal Control. In Proceedings of the 2016 35th Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Chengdu, China, 27–29 July 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 2642–2645. [Google Scholar]

- Sharomi, O.; Malik, T. Optimal Control in Epidemiology. Ann. Oper. Res. 2017, 251, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Giannino, F.; Tartakovsky, D.M. Parsimonious models of in-host viral dynamics and immune response. Appl. Math. Lett. 2023, 145, 108781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyobi, S.; Jan, R. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of fractional dynamics of infectious diseases with control measures. Fractal Fract. 2023, 7, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Becheikh, N.; Kolsi, L.; Muhammad, T.; Ahmad, Z.; Nasrat, M.K. Uncovering the stochastic dynamics of solitons of the Chaffee–Infante equation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.; Liu, W.; Aeshah, A.R.; Khan, N.; Khan, S.U.; Ozair, M.; Ahmad, Z. Unraveling pine wilt disease: Comparative study of stochastic and deterministic model using spectral method. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 240, 122407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, R.J.; Ono, M. Skin Disease Modeling from a Mathematical Perspective. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2013, 133, 1472–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lydeamore, M.J.; Campbell, P.T.; Price, D.J.; Wu, Y.; Marcato, A.J.; Cuningham, W.; Carapetis, J.R.; Andrews, R.M.; McDonald, M.I.; McVernon, J. Estimation of the Force of Infection and Infectious Period of Skin Sores in Remote Australian Communities Using Interval-Censored Data. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2020, 16, e1007838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galach, M. Dynamics of the Tumor-Immune System Competition: The Effect of Time Delay. Int. J. Appl. Math. Comput. Sci. 2003, 13, 395–406. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, S.; Sarkar, R.R. Delay-Induced Model for Tumor–Immune Interaction and Control of Malignant Tumor Growth. Biosystems 2008, 91, 268–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, P.; Ruan, S.; Zhang, X. Periodic and Chaotic Oscillations in a Tumor and Immune System Interaction Model with Three Delays. Chaos: Interdiscip. J. Nonlinear Sci. 2014, 24, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Guo, Y.; Du, Y. Hopf Bifurcation Induced by Delay Effect in a Diffusive Tumor-Immune System. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2018, 28, 1850136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, S. Nonlinear Dynamics in Tumor-Immune System Interaction Models with Delays. Discret. Contin. Dyn. Syst. B 2020, 26, 541–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lydeamore, M.J.; Campbell, P.T.; Cuningham, W.; Andrews, R.M.; Kearns, T.; Clucas, D.; Dhurrkay, R.G.; Carapetis, J.; Tong, S.Y.C.; McCaw, J.M. Calculation of the Age of the First Infection for Skin Sores and Scabies in Five Remote Communities in Northern Australia. Epidemiol. Infect. 2018, 146, 1194–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantaye, A.K.; Goshu, M.D.; Zeleke, B.B.; Gessesse, A.A.; Endalew, M.F.; Birhanu, Z.K. Mathematical Model and Stability Analysis on the Transmission Dynamics of Skin Sores. Epidemiol. Infect. 2022, 150, e207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoaib, M.; Tabassum, R.; Nisar, K.S.; Raja, M.A. Framework for the Analysis of Skin Sores Disease Using Evolutionary Intelligent Computing Approach. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassard, B.D.; Kazarinoff, N.D.; Wan, Y. Theory and Applications of Hopf Bifurcation; CUP Archive: Cambridge, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).