Abstract

There are distinct techniques to generate fuzzy implication functions. Despite most of them using the combination of associative aggregators and fuzzy negations, other connectives such as (general) overlap/grouping functions may be a better strategy. Since these possibly non-associative operators have been successfully used in many applications, such as decision making, classification and image processing, the idea of this work is to continue previous studies related to fuzzy implication functions derived from general overlap functions. In order to obtain a more general and flexible context, we extend the class of implications derived by fuzzy negations and t-norms, replacing the latter by general overlap functions, obtaining the so-called -implication functions. We also investigate their properties, the aggregation of -implication functions, their characterization and the intersections with other classes of fuzzy implication functions.

Keywords:

implication functions; aggregation functions; general overlap functions; overlap functions; grouping functions MSC:

03E72

1. Introduction

In recent years, a plethora of fuzzy implication functions have been proposed in the literature [1,2,3,4]. These functions have been investigated from a more theoretical point of view [2,5,6] to the one involving practical applications [7,8,9]. They can be used in various fields such as approximate reasoning [10,11,12,13], decision making [14], image processing [15], and fuzzy mathematical morphology [16].

The first impact of fuzzy implications functions was the formalization of the “if… then…” rules in the fuzzy inference process used, for example, in fuzzy rule-based systems. Roughly speaking, it allows one to deduce a possible imprecise conclusion from a collection of imprecise premises. Therefore the implication operator is taken as a fuzzy relation, known as the generalized modus ponens/tollens [17,18,19]. For instance, in classification problems, the following schema may be applied in the fuzzy inference process, taking as being fuzzy concepts:

Premise: A belongs to class P;

Relation 1: A and B are close;

Relation 2: B is slightly smaller than A;

Conclusion: B belongs to class P.

There are many strategies to define fuzzy implication functions that either combine logical connectives (for instance, (S,N), R or QL-implications), or use univariate functions, such as Yager’s f and g-generated implications [13].

The class of implication functions constructed from a t-norm T and a fuzzy negation N was revisited by Pinheiro et al. [20] where the focus was on their properties and also the definition of fuzzy subsethood measures using the fuzzy implication functions called (T,N)-implications.

Most studies on fuzzy implication functions use t-norms and t-conorms [21,22]. However, different operators have been applied to construct implication-like functions, notably, uninorms or semi-uninorms [23,24,25], pseudo-t-norms [26,27], (dual) copulas, quasi- (semi-) copulas [28,29,30,31]. We also highlight the ones given from weaker operators such as overlap and grouping functions which are non-necessarily associative aggregation operators [32,33,34,35] and their interval-valued extensions. Notice that, in contrast with the work by Pinheiro et al. [20] mentioned above, Dimuro et al. [33] developed the more flexible concept of -operations and fuzzy implications functions derived from overlap and grouping functions, with the applications to the construction of fuzzy subsethood and entropy measures.

Note that, in classical logic, one can define the implication connective in distinct ways, meaning that if the truth tables are equal, then the operators are equivalent [36]. However, when one generalizes those equivalences to the unit interval , different classes of fuzzy implication functions are obtained. For example, when we generalize the ∨ operator and replace it by the grouping function G, the ∧ operator by the overlap function O and ¬ by a fuzzy negation N, we can mention -implication functions [34], which generalize the material implication used in Kleene algebra that can be defined according to the tautology: .

In [32], -implication functions were proposed using overlap functions inspired on the generalization of Boolean implications resulted as the residuum of the conjunction of Heyting algebra considered in the intuitionistic logic and defined according to the identity: , where X is a universe set and . Moreover, the implication functions defined in the quantum logic framework, were also generalized [33], using the following tautology: , called QL-implication functions. Finally, we have D-implication functions [35] (also known as Dishkant implication), derived from the following generalization: .

Therefore, following the natural sequence of the investigation on fuzzy implication functions constructed from overlap and grouping functions, the tautology still can be used to defined a new class. Despite being generalized by t-norms, and called -implication functions, it seems that applying a more general and flexible context may be feasible when using general overlap functions instead of the standard overlap functions.

The aim of this paper is to provide a theoretical study on a new family of fuzzy implications entitled -implications, where is the set of general overlap functions and N is a fuzzy negation. The objectives are threefold: (i) the study of the main properties satisfied by this new class, (ii) -implication characterization, and (iii) analysis of the intersections between -implications and other families of implications defined via overlap and grouping functions.

The remaining sections of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 recalls some definitions and important concepts used in our work. The major contributions related to the new class of -implication functions and the intersections between other classes are seen in Section 3 and Section 4. At last, we discuss the final remarks and future works in Section 5.

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Fuzzy Negations

Fuzzy negations have been deeply investigated [5,34,37]. Let us recall some important ideas.

Definition 1.

A fuzzy negation is a function satisfying:

- (N1)

- N is decreasing, i.e., if ;

- (N2)

- and .

A fuzzy negation N is strict if (N3) N is continuous and (N4) whenever .

A fuzzy negation N is strong if (N5) , for each and crisp if (N6) , for all .

A fuzzy negation N is said to be frontier if it satisfies (N7) if and only if or .

The standard (or Zadeh) negation is: .

Remark 1.

By [33], a fuzzy negation is crisp if and only if there exists such that or there exists such that , where

The smallest fuzzy negation and the greatest fuzzy negation are examples of crisp fuzzy negations. They are defined by and , respectively.

In our next developments, the N-duality notion will play an important role.

Definition 2.

Let N be a fuzzy negation and be any function. The N-dual function of f, for all , is given by:

2.2. From Aggregation Functions to General Overlap Functions

Definition 3

([38]). An n-ary aggregation function is a mapping satisfying the following properties:

- (A1)

- and ;

- (A2)

- If , then , for each .

Proposition 1

(Corollary 3.8 [12]). Let be an aggregation function and N be a fuzzy negation. The N-dual function of A, denoted by , is also an aggregation function.

Definition 4

(Definition 1.1 [39]). A bivariate aggregation function is called a t-norm if it satisfies, for all ,

- (T1)

- ; (commutativity)

- (T2)

- ; (associativity)

- (T3)

- whenever ; (monotonicity)

- (T4)

- . (boundary condition)

Definition 5

(Definition 15 [40]). A bivariate function is an overlap function if it holds, for all :

- (O1)

- ;

- (O2)

- if and only if or ;

- (O3)

- if and only if ;

- (O4)

- O is increasing, i.e., if then ;

- (O5)

- O is continuous.

Remark 2.

Note that whenever an overlap function has a neutral element, then, by (O3), it is necessarily 1.

Definition 6

(Definition 3 [41]). A bivariate function is a grouping function if it holds, for all ,

- (G1)

- ;

- (G2)

- if and only if ;

- (G3)

- if and only if or ;

- (G4)

- G is increasing, i.e., if then ;

- (G5)

- G is continuous.

Remark 3.

Note that whenever a grouping function has a neutral element, then, by (G2), this element is necessarily 0.

For further properties and related concepts on overlap/grouping functions, refer to [32,33,34,42,43,44,45].

Theorem 1

(Theorem 2 [41]). Let O be an overlap function, and let N be a strict fuzzy negation. Then,

is a grouping function. Reciprocally, if G is a grouping function, then

is an overlap function.

In the following remark we show that if an overlap function O admits a neutral element, and if N is not a strong negation, then the dual grouping function G does not have a neutral element.

Remark 4.

Let N be a strict and non-strong fuzzy negation and O be an overlap function. If O has a neutral element, then the grouping function G given by Equation (2) has no neutral element.

It is clear that since O has a neutral element, then , for all . However, as N is a non-strong fuzzy negation, there is such that , so: . Therefore, G has no neutral element.

Next, we present the concept of general overlap function. Note that any t-norm is, in particular, a general overlap function in two variables.

Definition 7

(Definition 8 [46]). A function is a general overlap function (GOF, for short) if it satisfies the following properties, for all ,

- ()

- , whereis any permutation of ;

- ()

- If then ;

- ()

- If then ;

- ()

- is increasing;

- ()

- is continuous.

Some examples of overlap functions and GOF are given in Table 1, where is defined by [46]. Notice that any overlap function is a bivariate general overlap function, but the converse does not necessarily hold.

Table 1.

Examples of overlap functions O and general overlap functions .

2.3. Some New Results on General Overlap Functions

Proposition 2.

Let O be an overlap function and take . Therefore, defined, for all , by

is a bivariate GOF which is not an overlap function.

Proof.

By (O3), and, therefore, is well defined. Clearly, is commutative, increasing, satisfies (2) and (3) but does not satisfy (O2). In addition, let be a sequence, such that . So, for each , we have two situations: (i) if , then and (ii) if then, since O is continuous and commutative, Therefore, is continuous. □

Proposition 3.

Consider a strict negation N and a bivariate general overlap function . If satisfies the following conditions, for all ,

- ()

- If then ;

- ()

- If then ,

then

is a grouping function. Reciprocally, if G is a grouping function, then

is a GOF satisfying (2a) and (3a).

Proof.

Since such GOF is also an overlap function, then the result follows straight from Theorem 1. □

An element is a neutral element of if for each , .

Proposition 4.

Let be a bivariate general overlap function. Then 1 is a neutral element of if and only if satisfies (3a) and has a neutral element.

Proof.

If then, by (4) and since 1 is a neutral element of , one has that and , i.e., . Conversely, if a bivariate general overlap function satisfies (3a) and has a neutral element a then . In fact, and therefore, by (3a), . □

Remark 5.

Observe that the result stated by Proposition 4 does not mean that when a bivariate GOF has a neutral element then it is equal to 1. In fact, for each , the function

is a GOF with e as the neutral element.

Since is an aggregation function, the following proposition is immediate.

Proposition 5.

If 1 is the neutral element of a general overlap function and is idempotent, then is the minimum.

Lemma 1.

Let be an aggregation function and be a family of general overlap functions. Then is a GOF whenever A is continuous.

Proof.

We will verify that satisfies the conditions that define a GOF:

(1) Indeed, for all , since is commutative for all , we have for any :

(2) If , then, by (2), for all ,

(3) If , then, by (3), for all ,

(4) The result is immediate, since A and are increasing, .

(5) Since A and are continuous, , the result follows.

Therefore, is a general overlap function. □

2.4. Fuzzy Implications Derived from Overlap and Grouping Functions

The definition of fuzzy implication functions in [5,47,48], is given as follows:

Definition 8.

A function is a fuzzy implication function if, for all , the following properties are satisfied:

- (I1)

- If then ; (left antitonicity)

- (I2)

- If then ; (right isotonicity)

- (I3)

- ; (left boundary condition)

- (I4)

- ; (right boundary condition)

- (I5)

- .

We denote by the set of all fuzzy implications.

Definition 9

(Definition 11 [49]). A fuzzy implication function is said to be crisp if , for each .

Proposition 6

(Proposition 2 [49]). Let be a fuzzy implication function. Then I is crisp if and only if one of the following conditions are satisfied, for all :

- (C1)

- If there exists and such that , where

- (C2)

- If there exists and such that , where

- (C3)

- If there exists such that , where

- (C4)

- If there exists such that , where

Definition 10

(Definition 1.4.15 [5]). Let . The function defined by

is called natural negation of I or negation induced by I.

It is clear is indeed a fuzzy negation. If I is crisp then is a crisp fuzzy negation. Other properties may be demanded for fuzzy implication functions. In the following, we highlight some of them:

Definition 11.

A fuzzy implication function satisfies, for all , the:

- (NP)

- Left neutrality property if and only if ;

- (IP)

- Identity principle if and only if ;

- (EP)

- Exchange principle if and only if ;

- (EP1)

- Exchange principle for 1 if and only if ;

- (IB)

- Iterative Boolean law if and only if ;

- (LOP)

- Left-ordering property, if whenever ;

- (ROP)

- Right-ordering property, if whenever ;

- (CP)

- Law of contraposition (or the contrapositive symmetry) with respect to fuzzy negation N, if and only if ;

- (L-CP)

- Law of left contraposition with respect to fuzzy negation N if and only if ;

- (R-CP)

- Law of right contraposition with respect to fuzzy negation N if and only if .

If I satisfies the (left, right) contrapositive symmetry with respect to N, then we also will denote this by L-CP(N), R-CP(N), and CP(N), respectively.

A well-known result is that from bivariate operations on the unit interval , it is possible to construct families (classes) of fuzzy implication functions [5]. Hence, one can also use overlap and grouping functions to obtain other classes of implication functions, such as and D-implication functions, defined as follows.

Definition 12.

Let be an overlap function, be a grouping function and be a fuzzy negation. Then, the functions are called:

- 1.

- -implication function, given by [34], if

- 2.

- -implication function, given by [33] (where is the crisp fuzzy negation defined according to Remark 1) if

- 3.

- A residual -implication function, given by [32], if

- 4.

- D-implication function derived from G, given by [35], if

3. -Implications

A class of fuzzy implication functions entitled -implications was investigated in [20]. They were derived from the composition of a fuzzy negation and a t-norm, and many relevant properties were discussed. In the current study, a similar class of implication functions is investigated. However, we substitute the t-norm by a bivariate GOF. Thus, we provide a new class of implication function called -implications, defined as follows.

Definition 13.

A function is said to be a -implication if there exists a bivariate general overlap function and a fuzzy negation such that, for all

If N is strict, then I is called strict -implication. Analogously, if N is strong, I is called strong -implication.

Remark 6.

The above definition agrees with the result given by Theorem 4.3 [50], which states that a function is an implication function if and only if A is a conjunctor. This result is dual to Theorem 33 [11].

From now on, whenever I is a -implication function generated from and N, it will be denoted by .

Example 1.

We can construct some examples of .

- (i)

- Consider the GOF: and the standard fuzzy negation , then we have that:

- (ii)

- Take the GOF: , for and , so:

- (iii)

- Consider the general overlap function and the crisp fuzzy negation , then we have that:

- (iv)

- Take the GOF , for and the crisp fuzzy negation , so:

Proposition 7.

If I is a -implication function then .

Proof.

Indeed, let I be a -implication function generated by a general overlap function and a fuzzy negation N, then

(I1) Given such that , by (4), for all , it holds that . So, , that is, .

(I2) Analogous to (I1).

(I3) For all , .

(I4) For all , .

(I5) .

Therefore, is a fuzzy implication function. □

The next result presents the conditions under which the class of (T,N)-implication functions is different from he class of -implication functions.

Proposition 8.

Let N be a strict fuzzy negation and be a GOF. If has no neutral element, then for any t-norm T.

Proof.

By hypothesis, has no neutral element, so there is such that . Since N is strict, given , there is such that . So,

On the other hand, for any t-norm T, we have . Therefore, . □

Corollary 1.

Let N be a strict fuzzy negation and and be general overlap functions. If has no neutral element, then .

Example 2.

Consider the GOF and the strict fuzzy negation respectively defined by and . So, one has that:

Observe that and for any t-norm T, we have that . Therefore, for all , .

Observe that it is possible to recover the bivariate general overlap function from any -implication function which was constructed from such GOF and a strict fuzzy negation, as shown in the following proposition.

Proposition 9.

Let be a bivariate GOF and N be a fuzzy negation. If N is strict, then, for all ,

Proof.

Straightforward. □

Corollary 2.

Let be a bivariate GOF and N be a fuzzy negation. If N is strong, then , for all .

Proposition 10.

Let and N be a GOF and a fuzzy negation, respectively. Then,

- (i)

- If 1 is the neutral element of , then ;

- (ii)

- If N is strict and , then 1 is the neutral element of .

Proof.

Indeed

- (i)

- For all , one has that .

- (ii)

- Since N is strict and , for all , we have: . □

Note that the converse of Proposition 10(i) is not always valid. There are non-strict negations N that satisfy , but has no neutral element. See the following example:

Example 3.

Take the fuzzy negation given by

and consider a bivariate general overlap function that satisfies (3a). Then, for all , one has that:

However, does not necessarily have a neutral element.

Proposition 11.

Let be a bivariate GOF and N be a fuzzy negation such that , for all . Then:

- (i)

- If , then ;

- (ii)

- If N is strict and , then .

Proof.

Indeed,

- (i)

- By hypothesis, take . Then, applying N on both sides, . On the other hand,for all . So, it follows that , and, therefore, .

- (ii)

- Since , for all , so, in particular, , for all . Moreover, . Hence, by hypothesis,for all . So, , since N is strict. Therefore, for all , .□

Proposition 12.

Let be a -implication function. Then:

- (i)

- satisfies L-CP(N);

- (ii)

- If N is a strict negation, then satisfies R-CP(N−1);

- (iii)

- If satisfies R-CP(N) with a strict negation N and 1 is the neutral element of , then N is a strong negation;

- (iv)

- If N is a strong negation, then satisfies CP(N);

- (v)

- If satisfies CP(N) with a strict negation N and 1 is the neutral element of , then N is a strong negation.

Proof.

(i) For all , it holds that: .

(ii) For all , one has that .

(iii) Since satisfies , then . Hence, since N is a strict negation, for all , i.e., for all . So, since 1 is the neutral element of , , for all .

(iv) For all , since N is strong: .

(v) Since satisfies CP(N) and N is a strict negation, then , i.e., . So, since 1 is the neutral element of , , for all . □

Example 4.

Consider a bivariate general overlap function with 1 being its neutral element, and the fuzzy negation given by Equation (9). Then, for and for all , one has that:

So,

Now, for and for all :

So,

However, N does not need to necessarily be a strong fuzzy negation to satisfies the CP(N) property.

Proposition 13.

Let be a -implication. If N is a strong negation, then

- (i)

- satisfies (NP) if and only if 1 is the neutral element of .

- (ii)

- satisfies (EP) if and only if is associative.

Proof.

Indeed,

(i) Consider , for all . Then, since N is strong, for all , .

So, one has that , for all . Conversely, since 1 is neutral element of , then for all , we have that .

(ii) Consider that satisfies (EP). Then, for all , since N is a strong negation,

and so, , for all . Therefore, is associative.

Conversely, , since N is strong and is associative, then

Therefore, satisfies (EP). □

Proposition 14.

Let be a -implication. If N is a strict negation, so if and only if is associative.

Proof.

Indeed, consider that . Then, for all ,

So, , for all , since N is a strict negation. Therefore, is associative. Conversely, , since is associative, then

So, for all , since N is continuous, there is such that . Thus , for all . □

Proposition 15.

Let be a bivariate GOF satisfying (2a), and be a -implication. If N is a frontier fuzzy negation, then satisfies (EP1).

Proof.

Suppose that , for all . This means that . In this case, since N is a frontier negation, then: .

By (2a), either or . Then, one has the following cases:

(1) For , it follows: .

(2) For , since N is a frontier negation, so . So, by (2a), or . If , then . On the other hand, if , then .

Thus, in any case, it holds that . □

Proposition 16.

Let be a -implication with a strict fuzzy negation N.

- (i)

- If satisfies (IB) and has 1 as neutral element, then N is strong and is idempotent.

- (ii)

- If N is strong and is idempotent and associative, then satisfies (IB) and has 1 as neutral element.

Proof.

Indeed,

(i) Since satisfies (IB), we have for , , . So, . Therefore, , for all , since 1 is neutral element of . However, N being a strict negation, then , for all and, then, N is strong. Moreover, since , we have that , since N is strong. So, . In particular, for , , for all , since 1 is the neutral element of . Therefore, the general overlap function is idempotent.

(ii) For all ,

So, satisfies (IB). In case , since N is strong, . So, for all , . Since is continuous and increasing, for all , there is such that . Thus, for all , . Therefore, 1 is a neutral element of □

Corollary 3.

Let be a -implication with a strict fuzzy negation N. If satisfies (IB) and 1 is the neutral element of the bivariate general overlap function , then is the minimum t-norm.

Proof.

Straightforward from Propositions 16 and 5. □

Remark 7.

Observe that, trivially, is crisp if and only if N is crisp. In fact, for each , if 1 is a neutral element of then and .

Proposition 17.

Let be a crisp -implication, and let 1 be a neutral element of , then:

- (i)

- satisfies (EP) but it does not satisfy (NP);

- (ii)

- satisfies (LOP) but it does not satisfy (ROP);

- (iii)

- satisfies (IP);

- (iv)

- satisfies (IB);

- (v)

- satisfies (CP) with respect to N;

- (vi)

- satisfies (R-CP) with respect to N.

Proof.

Indeed,

- (i)

- Straightforward from Proposition 6 [49], considering Remark 7.

- (ii)

- Since N is crisp and 1 is a neutral element of , it follows that:

- (LOP)

- For all such that , two situations are possible:

- (1)

- If there exists such that , so, by Remark 7 and (C4), we have that . Therefore,For , as , it holds that . Hence one concludes that . For , it is immediate that .

- (2)

- If there exists such that , so, by Remark 7 and (C3), we have . Thus,For , as , it holds that . So one concludes that .For , it is immediate that .

Therefore, it holds that satisfies . - (ROP)

- We also consider two situations:

- (1)

- If , for some , then take such that . Consequently, by Equation (10), .

- (2)

- If , for some , then take such that . Thus, by Equation (11), .

In both situations, there exists , but . So does not satisfy .

- (iii)

- Given , since N is crisp, either or . If , then . On the other hand, if , then , since 1 is the neutral element of .

- (iv)

- Given , as N is crisp, either or .

- (1)

- Take , and for all ,and .

- (2)

- Now, , and , since 1 is the neutral element of ,and . So, if , then and . Now, if , then, by , and . Therefore, in any case, .

- (v)

- Given , as N is crisp, either or .

- (1)

- For , then , and therefore , for all .

- (2)

- For , since 1 is the neutral element of , and, we also have thatfor all . Since N is crisp, for all . Therefore, .

- (vi)

- Given , as N is crisp, either or .

- (1)

- For , since 1 is the neutral element of , for all ,and . If , consequently, . Moreover, if then, .

- (2)

- For , since 1 is the neutral element of , . Moreover, , for all . So, if , then . However, if , then, by , we have that . So, in any case, .□

Aggregating -Implications

In [12], the authors performed a study on fuzzy implications obtained by the composition of an aggregation function A and a family of fuzzy implication functions. Here we verify under which conditions an -operator is a -implication, whenever is a family of -implication functions.

Definition 14

(Definition 5.1 [12]). Let be an aggregation function and take as a family of k-ary functions. An -operator on , denoted by , is given by:

In [12], it has been shown that preserves some properties of for . For example, if are fuzzy implication functions then is also a fuzzy implication function.

Proposition 18.

Let be a continuous aggregation function and let be a family of -implication functions. Then, is a -implication whenever for and N is a strong negation.

Proof.

Consider the family of -implication functions represented by . Then, since and N is a strong negation, for all ,

By Proposition 1, is an aggregation function. Furthermore, by the continuity of A and N, we have that is continuous. So, by Lemma 1, is a general overlap function. Therefore, since , then is a -implication function. □

Corollary 4.

Let be a continuous aggregation function and let , for , be a family of -implication functions. If N is a strong negation, then for with for , it holds that:

- (i)

- satisfies L-CP(N);

- (ii)

- If N is also strict, then satisfies R-CP(N−1);

- (iii)

- satisfies CP(N).

Proof.

Straightforward from Propositions 12 and 18. □

4. Intersections between Families of Fuzzy Implications

In this section we present results regarding the intersections that exist among the families of fuzzy implications , , , and D-implications derived from (general) overlap and grouping functions O and G, respectively, and fuzzy negations N. We will represent these families by , and , respectively.

4.1. Intersections between and -Implications

Proposition 19.

Let N and be fuzzy negations, be a bivariate general overlap function and G be a grouping function such that .

- (i)

- If N is strict and is frontier, then is an overlap function.

- (ii)

- If 1 is the neutral element of , then:

- (a)

- If N is a strong negation, then ;

- (b)

- If N is continuous and , then N is strong;

- (c)

- N is strong if and only if 0 is the neutral element of G.

- (iii)

- If 0 is the neutral element of G, then:

- (a)

- is strong if and only if ;

- (b)

- is strong if and only if 1 is the neutral element of .

Proof.

- (i)

- Indeed, if , thenMoreover, if , thenConsequently, satisfies (O2) and (O3) and we conclude that is an overlap function.

- (ii)

- Indeed,

- (a)

- by Prop. 3.4(xxi) [34] we have that satisfies R-CP(N′), sofor all . Therefore, .

- (b)

- Since satisfies R-CP(N′) and , . So, for , , i.e.,Since 1 is the neutral element of and , for all , . Now, since N is continuous, for every , there is such that . So, , for all .

- (c)

- For all , . So the result holds.

- (iii)

- Indeed,

- (a)

- by Prop. 3.4(ii) [34] we have that satisfies (NP), sofor all . Therefore, the result follows.

- (b)

- Consider as a strong negation, then by the previous item, . So, , for all . Therefore, 1 is the neutral element of . Conversely, , and therefore, by sub-item (a) of item (ii), is a strong negation. □

The next propositions show that strict -implication functions generated by general overlap functions satisfying (2a) and (3a) are strict -implication functions and vice-versa.

Proposition 20.

Let N be a strict fuzzy negation, be a GOF satisfying (2a) and (3a), and let G be the grouping function defined according to Equation (4). Then, one has that .

Proof.

For all , since N is strict, it follows:

□

Proposition 21.

Let N be a strict negation, G be a grouping function and be the general overlap function defined in Equation (3). Then, .

Proof.

For all , since N is strict, it follows that:

□

Corollary 5.

Let I be a fuzzy implication function. Then, I is a strict -implication with satisfying conditions (2a) and (3a) if and only if I is a strict -implication.

Proof.

Straightforward from Propositions 20 and 21. □

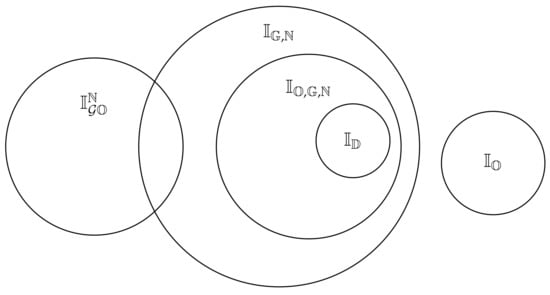

By Corollary 5 we have that the intersection of and -implications is non-empty: . In addition, we also conclude that , where is the family of all strict -implication functions and, analogously, is the family of all strict -implication functions.

Next, we provide an example presenting an implication function belonging to both classes and -implications.

Example 5.

Take the strict fuzzy negation N, defined by and consider the grouping function G given by . Then, for all , . Now, consider the general overlap fuction (Equation (3)). Note that and satisfies (2a) and (3a). So since , we have that:

Therefore, is a -implication and a -implication.

Proposition 22.

Let such that . If I is a -implication function then I is not a -implication function.

Proof.

Suppose that I is a -implication function. Then, there is a grouping G and a fuzzy negation N such that for each . However, since G is continuous and , , then for any there exists such that . Therefore, . □

Corollary 6.

Each crisp -implication function is not a -implication function.

Let . Proposition 22 proves that . Thus, there are -implication functions that are not -implication functions and therefore, the class of -implication functions is not contained in the class of -implication functions.

Note that the converse also holds as shown in the next proposition.

Proposition 23.

There are -implication functions that are not -implication functions.

Proof.

Take the -implication function , where and . Thus,

Suppose there exists a GOF and a fuzzy negation N such that

Thus, for , , for all ,

Furthermore, for , , for all . So, in particular, for , since is commutative,

for all . Now, given , we have either or . If then, by Equation and , it follows , which is a contradiction, since . Furthermore, if , then which is a contradiction, since . In both cases we have a contradiction, so is not a - implication function. □

The last two results ensure that and .

4.2. Intersections between and -Implication Functions

A tuple , with O being an overlap function, G being a grouping function and N being a fuzzy negation, known as a -operator [33] is in fact an implication function if and only if . Then, we conclude that:

Proposition 24.

There are no fuzzy implication functions that are simultaneously implication functions and -implication functions.

Proof.

Indeed, by Proposition 12(i), any -implication function satisfies L-CP(N). Moreover by Theorem 3.1(v) [33], any -implication does not satisfy (L-CP) for any negation N. □

Corollary 7.

There is no fuzzy implication function which is simultaneously a -implication function and a strict -implication function.

Proof.

Straightforward from Corollary 5 and Proposition 24. □

Therefore, one can conclude that the intersection of -implication functions and -implication functions is empty, i.e., . As a consequence, the intersection of -implication functions and -implication functions with N being a strict negation, is also empty: . In Theorem 5.1 [33], it is seen that -implication functions are included in the class of -implications. Example 6 illustrates that.

Example 6.

Consider the overlap function , the grouping function and the fuzzy negation given by Equation (9). Then, for all , one has that:

On the other hand,

Therefore, .

4.3. Intersections between and -implication Functions

Proposition 25.

There are no fuzzy implication functions that are simultaneously -implication functions and -implication functions.

Proof.

Indeed, by Proposition 12(i), any -implication satisfies L-CP(N), however by Theorem 4.2 [32], it is guaranteed that every -implication, , does not satisfy (L-CP) for any negation N. □

Therefore, one can conclude that -implication functions and the family of -implication functions do not intercept, i.e., .

4.4. Intersections between and D-Implication Functions

From the results given in Theorem 4.1 [35] we know that every D-implication function is a -operation considering the greatest fuzzy negation. Still, from Theorem 4.2 [35] we know that every D-implication is a -implication considering the greatest fuzzy negation. Therefore, it is straightforward that there are no intersections between implication functions and D-implication or -implication functions. Moreover, by Theorem 4.3 [35] one can say that there is no intersection between -implication functions and D-implication functions.

In Figure 1, we illustrate the main results presented in this section. Note that the intersections between the families of , , and D-implication functions had already been presented in other works [32,33,34,35].

Figure 1.

Intersections between families of fuzzy implication functions.

5. Final Remarks

In propositional logics, one may consider the negation (¬) and other logical connectives such as the implication (→), the disjunction (∨) or the conjunction (∧) as being primitive. Other connectives can be defined in a standard form using only two primitive connectives [36]. In particular, when the primitive connectives are the negation and the disjunction, the standard definition of the implication is given by (i) and when the primitive connectives are the negation and the conjunction, the standard definition of the implication is given by (ii) . The first one, in fuzzy logics, had motived the introduction of several classes of fuzzy implication functions, such as the , and implications, where the disjunction is given, respectively, by a t-conorm S, a grouping function G or a disjunctive aggregation function A (e.g., see [11,34,51]). The second one, using conjunctive operators, allowed the definition of implication functions based on t-norms [20]. In this work we introduced a class of implication function based on (ii), where the conjunction is given by generalized overlap functions.

The main contributions of this work are the investigation of properties satisfied by such implication functions, their characterization, and a study of the intersections between them and other classes of implication functions derived from (general) overlap/grouping functions. The summary of these intersections is illustrated in Figure 1. Actually, we complete this study by also considering the class of -implication functions, denoted by , which is also based on the standard definition of the implication given by (ii), but using a t-norm instead of a general overlap function. Since each continuous t-norm is a general overlap function but the converse does not hold, then trivially we have that: , and . In addition, Table 2 shows some of the properties satisfied by the -implication functions and -implication functions whenever we take into account: any fuzzy negation N, strong fuzzy negations (represented by ), non-strong fuzzy negations (represented by ) or crisp negations (represented by ). For each property, yes/no means that the property is/is not held for each implication of that class. Additional restrictions may appear as follows: nost means the property is not valid if N is strict, yes(no) means the property is(not) valid when 1 is the neutral element of , and yes means the property holds when is associative. Empty table cells mean that some implication functions of the class satisfy the property whereas others do not. We can notice that indeed -implication functions are more general since more properties are verified.

Table 2.

Some properties of fuzzy implication functions.

Our future works include studying the use of operators on other classes of implication functions and the construction of other classes of fuzzy subsethood measures like it was made in [20,33], which can be used to generate fuzzy entropies, similarity measures and penalty functions, and applied in many ways.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, J.P., H.S. and G.P.D.; writing—review and editing, G.P.D., B.B., R.H.N.S., J.F. and H.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by CNPq (grant numbers: 312053/2018-5, 301618/2019-4, 311429/2020-3), FAPERGS (grant number: 19/2551-0001660-3), CAPES-Print (grant number: 88887.363001/2019-00), Spanish Ministry Science and Tech. (grant numbers: TIN2016-77356-P, PID2019-108392GB I00 (AEI/10.13039/501100011033)), and Fundación “La Caixa” (grant number: LCF/PR/PR13/51080004).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Baczyński, M.; Jayaram, B. (S,N)- and R-implications: A state-of-the-art survey. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2008, 159, 1836–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baczyński, M.; Jayaram, B.; Massanet, S.; Torrens, J. Fuzzy Implications: Past, Present, and Future. In Springer Handbook of Computational Intelligence; Kacprzyk, J., Pedrycz, W., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 183–202. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Peralta, R.; Massanet, S.; Mesiarová-Zemánková, A.; Mir, A. A general framework for the characterization of (S,N)-implications with a non-continuous negation based on completions of t-conorms. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2022, 441, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massanet, S. Tidying up the mess of classes of fuzzy implication functions. In Book of Abstracts of the 10th International Summer School on Aggregation Operators; Springer: Olomouc, Czech Republic, 2019; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Baczyński, M.; Jayaram, B. Fuzzy Implications; Studies in Fuzziness and Soft Computing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 231. [Google Scholar]

- Grammatikopoulos, D.S.; Papadopoulos, B.K. A method of generating fuzzy implications with specific properties. Symmetry 2020, 12, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baczyński, M. On the Applications of Fuzzy Implication Functions; Soft Computing, Applications; Balas, V.E., Fodor, J., Várkonyi-Kóczy, A.R., Dombi, J., Jain, L.C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 9–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ellina, G.; Papaschinopoulos, G.; Papadopoulos, B. Research of fuzzy implications via fuzzy linear regression in data analysis for a fuzzy model. J. Comput. Methods Sci. Eng. 2020, 20, 879–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makariadis, S.; Souliotis, G.; Papadopoulos, B. Parametric Fuzzy Implications Produced via Fuzzy Negations with a Case Study in Environmental Variables. Symmetry 2021, 13, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dombi, J.; Baczyński, M. General Characterization of Implication’s Distributivity Properties: The Preference Implication. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2019, 28, 2982–2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradera, A.; Beliakov, G.; Bustince, H.; De Baets, B. A review of the relationships between implication, negation and aggregation functions from the point of view of material implication. Inf. Sci. 2016, 329, 357–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiser, R.H.S.; Bedregal, B.R.C.; Baczyński, M. Aggregating fuzzy implications. Inf. Sci. 2013, 253, 126–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yager, R.R. On some new classes of implication operators and their role in approximate reasoning. Inf. Sci. 2004, 167, 193–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagouropoulos, P.; Tzimopoulos, C.D.; Papadopoulos, B.K. A method for the detection of the most suitable fuzzy implication for data applications. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Engineering Applications of Neural Networks, Athens, Greece, 25–27 August 2017; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 242–255. [Google Scholar]

- Štěpnička, M.; De Baets, B. Implication-based models of monotone fuzzy rule bases. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2013, 232, 134–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, I. Duality vs. adjunction for fuzzy mathematical morphology and general form of fuzzy erosions and dilations. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2009, 160, 1858–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamdani, E.H. Application of fuzzy logic to approximate reasoning using linguistic synthesis. IEEE Trans. Comput. 1977, 26, 1182–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizumoto, M.; Zimmermann, H.J. Comparison of fuzzy reasoning methods. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1982, 8, 253–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. A Theory of Approximate Reasoning. Mach. Intell. 1979, 9, 149–194. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro, J.; Bedregal, B.; Santiago, R.H.; Santos, H. A study of (T,N)-implications and its use to construct a new class of fuzzy subsethood measure. Int. J. Approx. Reason. 2018, 97, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, D.; Prade, H. A theorem on implication functions defined from triangular norms. Stochastica 1984, 8, 267–279. [Google Scholar]

- Grammatikopoulos, D.S.; Papadopoulos, B.K. An Application of Classical Logic’s Laws in Formulas of Fuzzy Implications. J. Math. 2020, 2020, 8282304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.W. Semi-uninorms and implications on a complete lattice. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2012, 191, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, A.; Liu, H.; Qin, F.; Zeng, Z. Solutions to the functional equation I(x,y)=I(x,I(x,y)) for three types of fuzzy implications derived from uninorms. Inf. Sci. 2012, 186, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Liu, X. Characterizations of (U2,N)-implications generated by 2-uninorms and fuzzy negations from the point of view of material implication. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2020, 378, 79–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.W. Two classes of pseudo-triangular norms and fuzzy implications. Comput. Math. Appl. 2011, 61, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. Generating pseudo-t-norms and implication operators. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2006, 157, 398–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolati, A.; Sánchez, J.F.; Úbeda Flores, M. A copula-based family of fuzzy implication operators. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2013, 211, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbin, P.; Baczyński, M.; Grzegorzewski, P.; Niemyska, W. Some properties of fuzzy implications based on copulas. Inf. Sci. 2019, 502, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesiar, R.; Kolesárová, A. Copulas and fuzzy implications. Int. J. Approx. Reason. 2020, 117, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesiar, R.; Kolesárová, A. Quasi-Copulas, Copulas and Fuzzy Implicators. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2020, 13, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimuro, G.P.; Bedregal, B. On residual implications derived from overlap functions. Inf. Sci. 2015, 312, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimuro, G.P.; Bedregal, B.; Bustince, H.; Jurio, A.; Baczyński, M.; Miś, K. QL-operations and QL-implication functions constructed from tuples (O,G,N) and the generation of fuzzy subsethood and entropy measures. Int. J. Approx. Reason. 2017, 82, 170–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimuro, G.P.; Bedregal, B.; Santiago, R.H.N. On (G,N)-implications derived from grouping functions. Inf. Sci. 2014, 279, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimuro, G.P.; Santos, H.; Bedregal, B.; Borges, E.N.; Palmeira, E.; Fernandez, J.; Bustince, H. On D-implications derived by grouping functions. In Proceedings of the FUZZ-IEEE 2019, IEEE International Conference on Fuzzy Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 23–26 June 2019; IEEE: Los Alamitos, CA, USA, 2019; pp. 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson, E. Introduction to Mathematical Logic, 6th ed.; Discrete Mathematics and Its Applications; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Trillas, E. On negation functions in the theory of fuzzy sets. Stochastica 1979, 3, 47–59. [Google Scholar]

- Beliakov, G.; Pradera, A.; Calvo, T. Aggregation Functions: A Guide for Practitioners; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Klement, E.; Mesiar, R.; Pap, E. Triangular Norms; Trends in Logic–Studia Logica Library; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2000; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Bustince, H.; Fernandez, J.; Mesiar, R.; Montero, J.; Orduna, R. Overlap Functions. Nonlinear Anal. Theory Methods Appl. 2010, 72, 1488–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustince, H.; Pagola, M.; Mesiar, R.; Hullermeier, E.; Herrera, F. Grouping, Overlap, and Generalized Bientropic Functions for Fuzzy Modeling of Pairwise Comparisons. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2012, 20, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Hu, B.Q. On the Distributive Laws of Fuzzy Implication Functions Over Additively Generated Overlap and Grouping Functions. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2018, 26, 2421–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Hu, B.Q. On multiplicative generators of overlap and grouping functions. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2018, 332, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Hu, B.Q. On generalized migrativity property for overlap functions. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2019, 357, 91–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Hu, B.Q. On homogeneous, quasi-homogeneous and pseudo-homogeneous overlap and grouping functions. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2019, 357, 58–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Miguel, L.; Gómez, D.; Rodríguez, J.T.; Montero, J.; Bustince, H.; Dimuro, G.P.; Sanz, J.A. General overlap functions. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2019, 372, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodor, J.; Roubens, M. Fuzzy Preference Modelling and Multicriteria Decision Support; Kluwer: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Mas, M.; Monserrat, M.; Torrens, J.; Trillas, E. A Survey on Fuzzy Implication Functions. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2007, 15, 1107–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, J.; Bedregal, B.R.C.; Santiago, R.H.N.; Santos, H.S. Crisp Fuzzy Implications. In Proceedings of the Fuzzy Information Processing-37th Conf. of the North American Fuzzy Information Processing Society, NAFIPS 2018, Fortaleza, Brazil, 4–6 July 2018; pp. 348–360. [Google Scholar]

- Demirli, K.; De Baets, B. Basic properties of implicators in a residual framework. Tatra Mt. Math. Publ. 1999, 16, 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Baczyński, M.; Jayaram, B. On the characterizations of (S,N)-implications. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2007, 158, 1713–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).