Abstract

Microbial carbonates are globally known petroleum reservoirs. However, the complex interplay between deposition and diagenesis significantly influences the pore network distribution in these microbial carbonate reservoirs. The present study aims to discuss diagenetic alterations in the Jurassic microbial carbonate successions from foreland basins in the NW Himalayas. Geological field observations, petrographic analysis, scanning electron microscopy, and isotopic analysis were applied to highlight the role of diagenesis in reservoir characterization of shallow marine carbonates. The results indicate that dolomitization, dissolution, and fracturing during the early to late phase of diagenesis enhanced the reservoir pore network. However, cementation, micritization, and mechanical compaction considerably reduced the reservoir pore distribution. Furthermore, fractures and stylolites that developed perpendicular to bedding planes indicate the role of convergent tectonics in developing the fracture network that allowed fluid migration and improved the pore spaces in microbial carbonate reservoirs. Isotopic data revealed shallow-burial diagenesis with marine and meteoric influx that provides avenues for the movement of fluids. These fluids are associated with microbial activity in carbonate rocks along the faults and fractures that were developed because of compressional tectonics, evident from the perpendicular fracture network. This study recommends the integration of deposition and diagenesis to refine the pore network distribution and characterization of carbonate reservoirs around the globe.

1. Introduction

Microbial carbonate reservoirs have garnered attention in recent decades, as many major oil and gas discoveries have been reported globally [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. These microbial carbonate reservoirs exhibit diverse depositional fabrics and complex diagenetic phenomena that require a comprehensive sedimentological analysis [9,10,11]. To better understand the origin, development, distribution, and depositional characteristics of microbial carbonate reservoirs, researchers have studied the depositional and diagenetic characteristics of microbialites and associated facies, as well as their sedimentary characteristics [10,12,13,14]. The literature on microbes is vast with respect to their diverse nature and occurrence in various depositional environments, but a limited number of studies have examined microbial carbonate reservoirs, combining diagenetic characteristics with reservoir characterization. Furthermore, the effect of tectonics on their diagenetic alteration is also not very clear [2,4,15,16]. These diagenetic processes significantly influence the pore network and reservoir heterogeneity [10,12]. Microbial activities have a profound impact on the textural fabric and diagenetic events that consequently influence the reservoir characterization and petroleum potential [4,14,17]. The depositional architecture and diagenetic processes associated with microbialites are valuable factors for discussing the reservoir characterization of microbial carbonates in various sedimentary basins worldwide, such as the South Oman Salt Basin [7,10], Sichuan Basin [1,3,4,15,18,19,20,21], Ordos Basin [22,23], and Tarim Basin [2,24,25]. These case studies show that microbial activity in carbonates greatly affects the reservoir potential of these rocks [12,26]. Hence, it is essential to incorporate the study of microbial activities in carbonate reservoirs to evaluate deposition and diagenetic evolution.

Jurassic carbonates in the Upper Indus Basin of Pakistan were previously discussed with respect to facies variations [27], dolomitization [28,29], sequence stratigraphy [30,31], and diagenetic evolution [32]. However, an integrated approach linking the depositional characteristics of microbial activity and consequent diagenetic alterations in shallow, marine platforms is essential to characterizing the heterogeneity in microbial carbonate reservoirs. The key objectives of the study include the analysis of sedimentary characteristics, the impact of diagenesis, and the consequent effect on reservoir heterogeneity in shallow, marine carbonate rocks. Sedimentological field observations, petrographic analysis, scanning electron microscopy, and isotope analysis were employed to understand the heterogeneities in carbonate reservoirs.

The study area includes four outcrop sections of ancient marine carbonates in the Upper Indus Basin that are characterized by extensive exposures of the Jurassic rocks. The area is tectonically active and allows fluids, evaporation, and meteoric water to intrude into the carbonate rocks, allowing for various sites for diagenesis and subsequent microbial activity [33]. Hence, the present carbonate units were extensively influenced by tectonic settings that resulted in diagenesis and microbial activity in the Jurassic marine carbonates.

2. Geological Settings

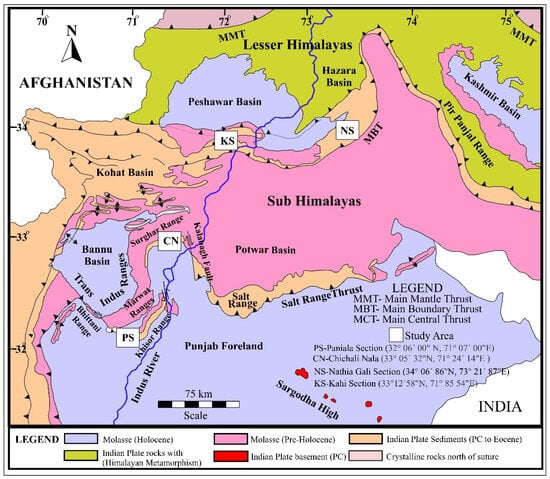

The Upper Indus Basin is known as one of the most prolific sedimentary basins and contains multiple carbonate reservoirs in various sub-basins, including Potwar Basin, Kohat Basin, and Bannu Basin (Figure 1) [34,35,36]. These carbonate reservoirs have a complex geological history in which depositional fabrics were significantly influenced by diagenesis [37,38]. Furthermore, petroleum exploration in various sub-basins of the Lesser and Sub-Himalayas has differential production data even with the same stratigraphic units of the Upper Indus Basin [39]. Therefore, the present study targets the Jurassic carbonate reservoirs to discuss the decisive role of diagenesis, which has a profound impact on reservoir characterization.

Figure 1.

Geological map of the Upper Indus Basin: The Paniala and Chichali field sections lie in the Trans-Indus ranges, representing the western extension of the Salt Range Thrust in the Sub-Himalayas, while the Natia Gali and Kahi field sections are located near the Main Boundary Thrust (MBT), the Lesser Himalayas, having extensive exposures of Jurassic carbonates.

The study includes four well-exposed sections of the Jurassic carbonates from Kahi sssection in Kala Chitta Range, Nathia Gali Section in the Hazara Basin, Chichali Nala in Surghar Range, and Paniala Section in Khisor Range (Figure 1). Both the Kahi and Nathia Gali sections are located near the Main Boundary Thrust (MBT), which represents the southern margin of the Lesser Himalayas [36]. The Chichali Nala and Paniala sections are part of the Trans-Indus ranges, which are a western extension of the Salt Range Thrust (SRT) and mark the southern limit of the Sub-Himalayas [27,34,40].

3. Data and Methods

Sedimentary logs were prepared for each exposed section at a scale of 1:100, and 106 rock samples were collected based on lithological heterogeneity, distinctive sedimentary features, diagenetic imprints, and microbial fabrics present in these carbonates. These rock samples were subsequently analyzed using the lab techniques explained below.

Based on lithological variations, 38 rock samples were shortlisted for petrography to characterize the carbonates with respect to depositional heterogeneity and diagenesis. Polished thin-section slides, 30 microns thick, were prepared using a standard petrography technique at Bacha Khan University, KPK, and these polished thin sections were later observed under a polarizing microscope at the COMSATS University, Abbottabad. These photomicrographs are useful for identifying sedimentary features, diagenetic processes, and microbial fabrics.

The diagenetic details and microbial features were examined using scanning electron microscopy to examine the types of microorganisms associated with carbonates. SEM uses an electron gun containing a tungsten filament that emits a beam of electrons, striking the sample. SEM analysis was used for ten representative samples to obtain high-magnification digital images of rock fabrics. Selected rock samples were precisely cut into 5 × 11 × 11 mm dimensions and were coated with gold alloy using a BIO-RAD SC502 sputter (JSM 5910, Jeol, Tokyo, Japan) at the University of Peshawar. These processed SEM stubs were then analyzed, and the resultant SEM backscattered images with high magnification and detail were acquired with SemAfore Digitizer software (Version 5.1) for interpretation of the microbial carbonates [41,42].

Oxygen and carbon isotopes are valuable in interpreting the diagenetic events and paleoenvironments of ancient marine carbonates. Sixteen samples from the four exposed sections were shortlisted from various limestone dolomite rocks with microbial and diagenetic features. These samples were taken using a microdrill with a diameter of 0.5–1.0 mm to maintain the precise sample size. The sample powder (approximately 50 mg) was treated with phosphoric acid and concentrated at 90 °C in the PINSTECH lab, Islamabad, Pakistan [27]. The ratios of oxygen (18O/16O) and carbon (13C/12C) isotopes were calculated using the Vienna Pee Deeee Belemnite (VPDB) standard based on mass spectrometry [28]. Precision values and error ranges for carbon and oxygen isotopes were calibrated to ±0.1 for values of δ18O and δ13C [28]. These isotopic ratios were applied to correlate diagenesis in microbial carbonates.

4. Results

4.1. Lithology and Field Observations

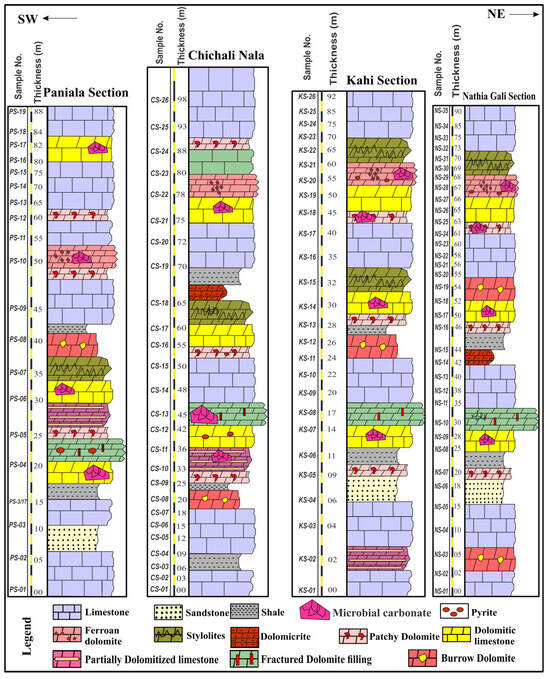

The mesoscopic and macroscopic observations in the geological fieldwork enabled us to highlight numerous field characteristics and lithological details of the carbonates that are visible at the outcrop level. The thickness of the Jurassic carbonates varies from 88 m to 98 m in the studied sections, which exhibit mainly carbonate rock units with occasional intervals of sandstones and shales (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Sedimentary logs of the studied sections of the Jurassic shallow marine rocks of the Upper Indus Basin. Sporadic occurrence of microbial carbonates in these Jurassic rocks.

The Jurassic carbonate intervals primarily consist of gray limestone and dolomitic limestone (5 m) in the lower portion of the Kahi section (Kala Chitta Range) and Nathia Gali section (Hazara Basin) (Figure 2), and dolomite patches in host limestone and sandstone units (Chichali and Paniala sections) in the lower to middle parts of the succession in the Trans Indus Ranges. Greyish shale beds (Chichali Nala) were interbedded within Jurassic limestone, and the limestone units were recorded in the middle part of the Jurassic carbonates of the Chichali Nala. Dolomitic limestone is in the middle part (Paniala section) (Figure 2) of the Jurassic microbial carbonates in the studied area. Light gray massive limestone (1–2.5 m) with sporadic intervals of dolomitic limestone was found in the upper part of the formation (Figure 2).

Microbial carbonates are commonly found in the middle part of the measured sections, while dolomite units are intermittently present in the middle to upper parts, showing the coexistence of dolomitization and microbial activity at discrete intervals (Figure 2). Additionally, the middle part of the studied sections exhibits fracturing and dolomite intervals, whereas dolomite units are occasionally associated with stylolites in the middle to upper part of the sections.

Dolomite units were observed in the field: dolomitic limestone, ferroan dolomite, dolomicrite, dolomite in fractures or burrows, and microbial dolomite were identified during the outcrop observations. However, microbial dolomite is uncommon in the exposed sections of the Jurassic carbonates. This is due to the relatively poor development of microbial activity in depositional environments of the shallow marine settings [30]. This is the prime reason why these Jurassic carbonates in the NW Himalayas are often neglected in the interpretation of microbial signatures [27,30].

4.1.1. Microbial Carbonates in the Paniala Section

Microbial carbonates were found in the dolomitic limestone units present in the lower part of the Paniala section, whereas these microbial fabrics were identified in the ferroan dolomite unit present in the middle part of the section (Figure 2). The upper part of the Paniala field section contains a microbial unit in the dolomitic limestone bed. Hence, the occurrence of microbial carbonates in dolomitic units demonstrates that the diagenetic process of dolomitization is closely associated with microbial carbonate beds. Microbial carbonates were not found in the limestone beds of the Paniala section.

4.1.2. Microbial Carbonates in the Chichali Nala

Microbial carbonates are less abundant in the Chichali Nala, where the fractured dolomite unit contains microbial fabric in the middle part of the section, while the upper part exhibits a dolomitic limestone interval with microbial input (Figure 2). The occurrence of microbial carbonates is less common in the Chichali Nala. Both the Paniala section and Chichali Nala are part of the Sub-Himalayas, with an uncommon distribution of microbial carbonates in the Jurassic stratigraphy. Lamina flats were found in the Chichali section (Figure 3c), which is sandwiched between the massive carbonate unit.

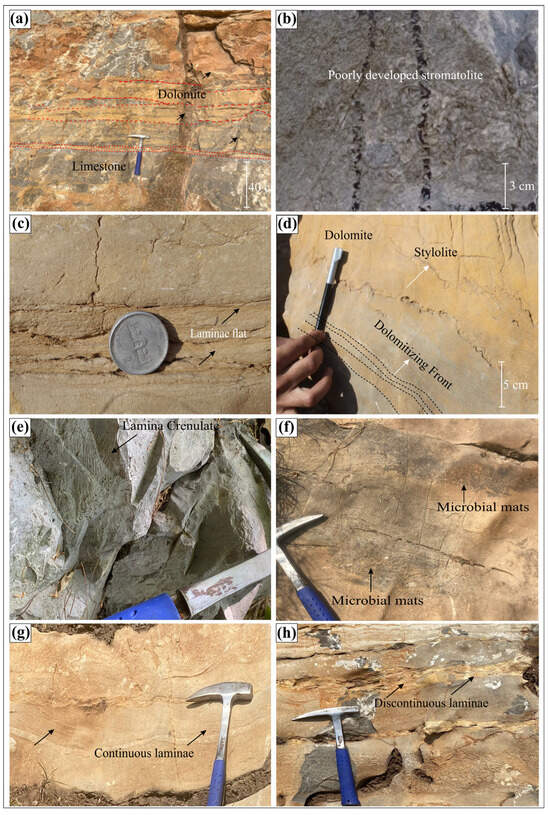

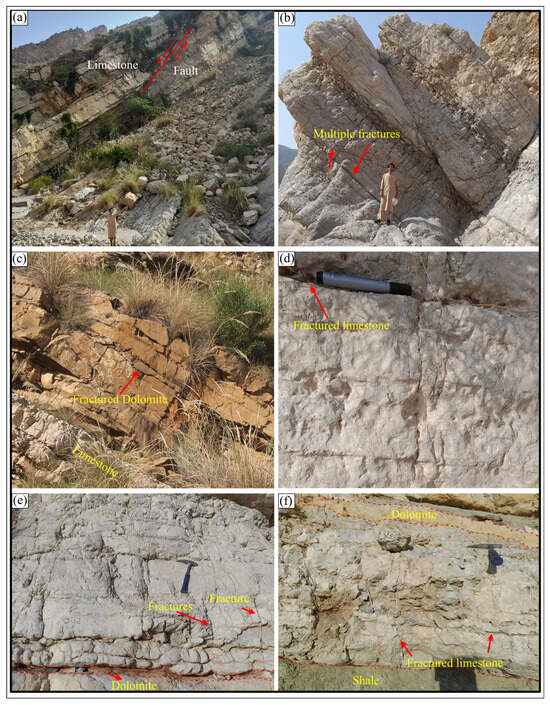

Figure 3.

Various types of diagenetic processes and microbial activity found in the shallow marine carbonates: (a) Limestone unit showing parallel and sub-parallel alternate dolomite laminations; (b) poorly developed stromatolites in the carbonate unit; (c) flat laminae associated with stylolitization, (d) dolomitization and stylolitization coexist in carbonates; (e) crenulate laminae found in the carbonate succession; (f) various cycles of microbial mats in the carbonate rock; (g) continuous laminae observed at the outcrop level; (h) discontinuous bands of laminae in microbial carbonates.

4.1.3. Microbial Carbonates in the Kahi Section

Field observations show that microbial carbonates were identified in the dolomitic limestone present in the middle part of the Kahi section, while the upper part contains microbial fabric in the ferroan dolomite units (Figure 2). These microbial units were more commonly found in the studied sections of the Lesser Himalayas.

4.1.4. Microbial Carbonates in the Nathia Gali Section

The distribution of microbial carbonates in the Nathia Gali section is in the middle part, where they were found in the dolomitic limestone units, whereas the upper part of the section contains microbial carbonates in the ferroan dolomite intervals (Figure 2). The microbial carbonates of the Nathia Gali section have diverse microbial fabrics with alternate repetitive cycles of microbial mats (Figure 3f) and crenulate laminae (Figure 3e).

Moreover, five types of dolomites at distinct stratigraphic intervals throughout the formation signify variation in depositional conditions and intensity of dolomitization (Figure 2). Saddle dolomite is also common in the middle part and is typically associated with fractured units, mainly as void-filling cement or as replacive dolomite. Thus, saddle dolomite can also be associated with karst surfaces and is considered a late diagenetic process. Fabric-destructive dolomite, for example, ferroan dolomite, is common throughout the upper part of the studied sections.

Microbial features were reported at the outcrop level, including burrowed surfaces, microbial mats, and stromatolitic layers. Burrowed surfaces in dolomite are predominantly present in the lower and middle parts of the strata and are directly associated with thick-bedded limestone units either above or below the burrowed units. Microbial mats are found as bedding-parallel swarms of laminae, which sometimes form a low-angle, distinctive feature. In some places, stromatolitic layers that show a partially conical appearance have been observed, but they appear and die laterally owing to short-term favorable conditions being required for development into the proper form (Figure 3).

The dolomitization in these carbonates is often discontinuous and largely associated with preexisting limestone intervals, as revealed by field studies. These limestone and dolomite bands are often found in a single rock unit (Figure 3a). Furthermore, microbial carbonates with discontinuous laminae, stromatolite, flat laminae, and various repeated intervals of microbial mats were found in the carbonate rock (Figure 3b). These microbial signatures are indicative of diversity in microbial activity and the occurrence of various horizons at the centimeter scale in the marine platform. However, field evidence limits the abundance and widespread existence of microbes in strata representing shallow marine deposition.

The stromatolite laminae are poorly developed at the outcrop level, but the flat laminae and discontinuous laminae are more visible in the exposed rock sections (Figure 3c,h). In contrast to microbial carbonates, dolomitization is more common and widespread in the field observation of Jurassic stratigraphy, where these dolomites are often present at discrete intervals with alternate limestone and dolomite bands, a dolomite front, and limestone that had evolved with dolomitic limestone due to a high influx of magnesium in the marine environment. Dolomite is commonly observed near stylolitized zones (Figure 3d), where the dolomite unit displays variable textural characteristics as compared to the limestone unit, and stylolite marks the boundary between the dolomite and limestone units.

4.2. Microfacies and Petrography of Microbial Carbonates

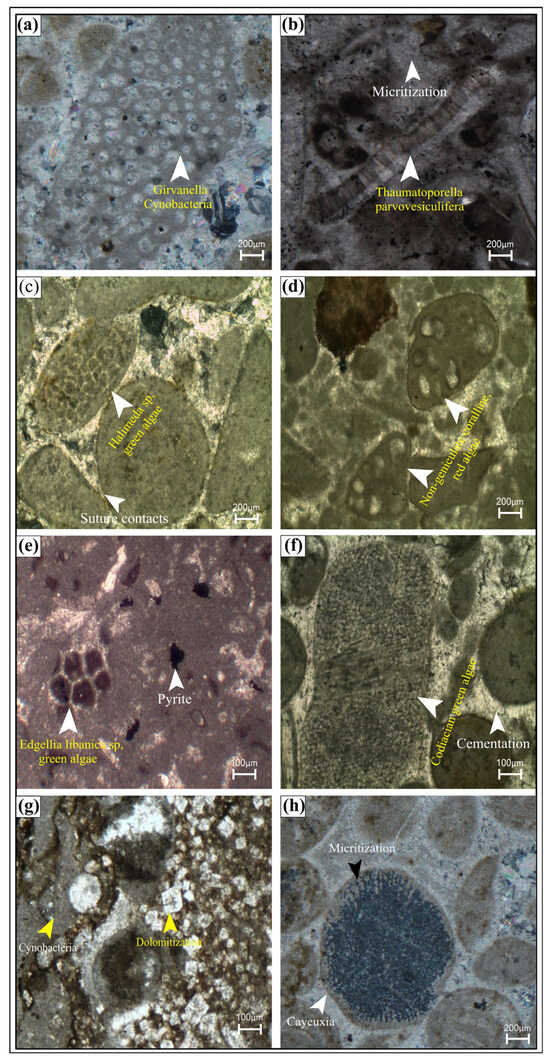

Petrographic studies revealed various depositional and diagenetic features in the Jurassic carbonates. Microbial dolomudstone consists of very fine to fine crystals (10–20 µm) that are dark brown to black in color and are found in association with irregular planar laminations and algal stromatolites. The dolomite rhombs exhibit filamentous cyanobacteria (subtifloria genra), microbial laminae, and spherulites in limestone units; cyanobacteria and microbial laminae were found near the dolomitized interval (Figure 4a–d). However, microbial activity, including algal laminae, spherulite, and Cayeuxia (Figure 4e,f), is correspondingly related to non-skeletal fragments in the carbonate rocks. Microbial carbonates exhibit complex interactions of Girvanella Cyanobacteria (Figure 5a) due to the calcification of the microbial sheath; Thaumatoporella parovesiculifera, associated with micritization as diagenetic alteration (Figure 4b); Halimeda sp. of green algae, found with sutured contact identified as a result of mechanical compaction (Figure 4c); non-geniculate coralline red algae (Figure 4d); Edegllia libanica sp. of green algae (Figure 4e); Codiacian green algae observed with calcite cementation (Figure 5f); cyanobacteria along with dolomite crystals (Figure 4g); and a micritized fragment of Cayeuxia genus of cyanobacteria (Figure 4h)—these photomicrographs show the diverse occurrence of microbial organisms in the Jurassic carbonates of the Upper Indus Basin.

Figure 4.

Petrographic analysis showing microbial carbonates and diagenetic processes. (a) Girvanella cyanobacteria developed in the carbonate unit; (b) diagenetic process of micritization associated with Thumatoporella parovesiculifera microbe; (c) sutured contact developed by mechanical compaction during diagenesis with Halimeda sp. of green algae; (d) non-geniculate coralline red algae identified in the microbial carbonate; (e) scattered patches of pyrite formed during diagenesis associated with Edgellia libanica sp. of green algae; (f) diagenetic phenomenon of cementation and codiacian green algae; (g) partial dolomitization along with cyanobacteria; and (h) Cayeuxia developed due to micritization of non-skeletal allochems.

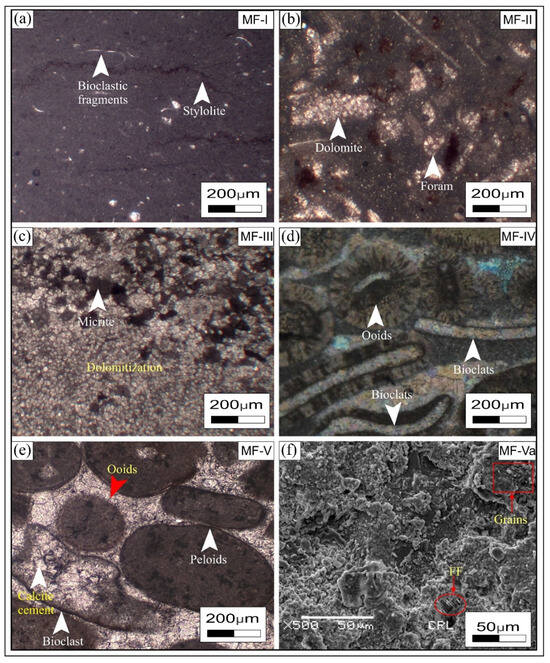

Figure 5.

Microfacies analysis of Jurassic carbonates. (a) Mudstone microfacies (MF-I) including mud-filled stylolites; (b) bioclastic dolopackstone microfacies (MF-II); (c) dolomitic grainstone microfacies (MF-III) with variable dolomite rhombs; (d) bioclastic ooidal grainstone microfacies (MF-IV) with many dissolution pores; (e,f) bioclastic peloidal ooidal grainstone microfacies (MF-V) with fossil fragment (FF) in the SEM image.

Five distinct microfacies types on petrographic and SEM analysis were identified based on variations in rock texture, grain composition, fossils, and sedimentary architecture in the studied thin section. These microfacies were grouped into five distinct facies associations, which represent three depositional settings within shallow marine carbonate environments. Mudstone microfacies (MF-I), characterized by a dark-grey micritic framework and bioclastic fragments, were placed in the supratidal zone. Mudstone microfacies were visually interpreted based on the matrix and fossils, which contain 10% grains (Figure 5a) and were formed at the base of the formation in the Chichali Nala and Paniala sections in the Trans-Indus Ranges, Sub-Himalayas. Bioclastic dolopackstone microfacies (MF-II) are characterized by a framework primarily composed of bioclasts, including foraminifera, gastropods, bivalves, and echinoderms, supported by a dolomitized micritic matrix. These microfacies were recorded in the middle of the Kahi section (Kala Chitta Range) in the Lesser Himalayas. Dolomicrite grainstone microfacies (MF-III) were observed in the middle to upper portion of the Nathia Gali and Paniala sections, consisting predominantly of fine-crystalline dolomite with minor relic micrite, a lack of recognizable allochems, and being formed as grainstone. This type of microfacies consists of a completely dolomitized fabric, where only small patches of original micrite are preserved. Bioclastic–ooidal grainstone (MF-IV) is characterized by the predominance of well-rounded ooids with minor bioclast fragments, including a negligible amount of micritic lime mud matrix. Bioclastic–peloidal–ooidal grainstone (MF-V) was characterized based on sparry calcite cement, in which bioclast fragments, clearly observed in photomicrographs, along with minor non-skeletal peloid grains, were observed in petrographic analysis of the upper portion of the Chichali and Paniala sections. Scanning electron microscopy (Figure 5f) clearly displays the presence of fossil fragments and the matrix, as well as cementation in the microfacies of bioclastic–peloidal–ooidal grainstone.

4.3. Microbial Features

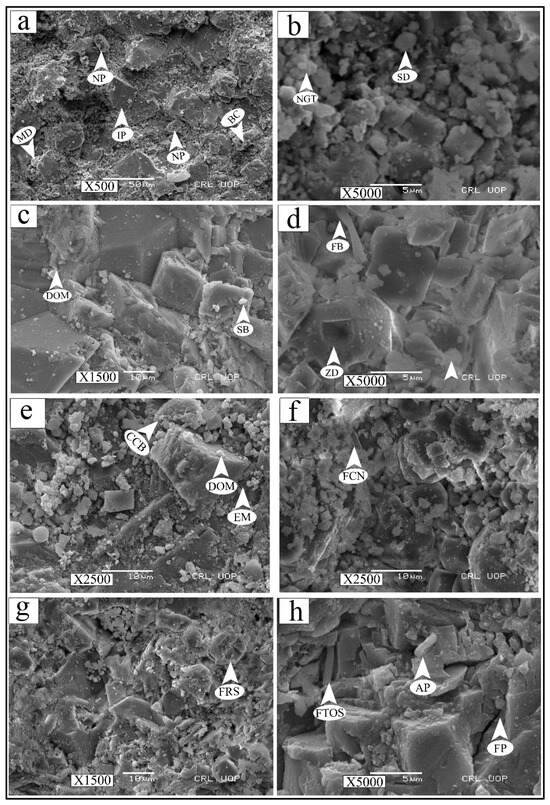

Five distinct microbial features were observed in the images obtained from scanning electron microscopy, which are associated with the formation of dolomite in the shallow marine environment. Dolomite rhombs are occasionally attached with microbial features and are termed microbial dolomite (MD), which also exhibits nanoplankton (NP) and bacteria (BC) with intracrystalline porosity (ICP), as shown in Figure 6a. Saddle dolomite (SD) was found to have microbial expressions in the form of fibrous radial spherulite (FRS) and nanoglobulus texture (NGT), associated with intracrystalline porosity (Figure 6b).

Figure 6.

SEM images showing microbial features and types of reservoir porosity in shallow marine carbonates. (a) Nanoplanktons (NPs) with intracrystalline porosity (ICP); (b) Nanoglobulus texturen (NGT) with intercrystalline porosity; (c) spherical bodies of microbes with intercrystalline porosity; (d) filamentous bacteria (FB) with dissolution porosity (DP); (e) colony of coccus bacteria (CCB), and EM, empty mold; (f) dissolution porosity (DP) and filamentous cyanobacteria (FCN); (g) dissolution porosity (DP) and fibrous radial spherulites (FRS); (h) filamentous tabular organic structure (FTOS), Acidiphilium Sp. (AP) and intracrystalline porosity (ICP).

Spherical bodies (SPs) of microbes were associated with variable-sized crystals of dolomite linked with intracrystalline porosity (Figure 6c). Filamentous bacteria (FB) were identified in the zoned dolomite crystals, which are occasionally associated with dissolution porosity (DP) (Figure 6d). Colonies of coccus bacteria (CCB) and empty mold (EM) (Figure 6e), filamentous cyanobacteria (FCB), fibrous radial spherulite, and filamentous tabular organic structures having both dissolution porosity (DP) and intracrystalline porosity (ICP) were identified in the Jurassic carbonates of the shallow marine settings (Figure 6f–h).

4.4. Diagenetic Processes

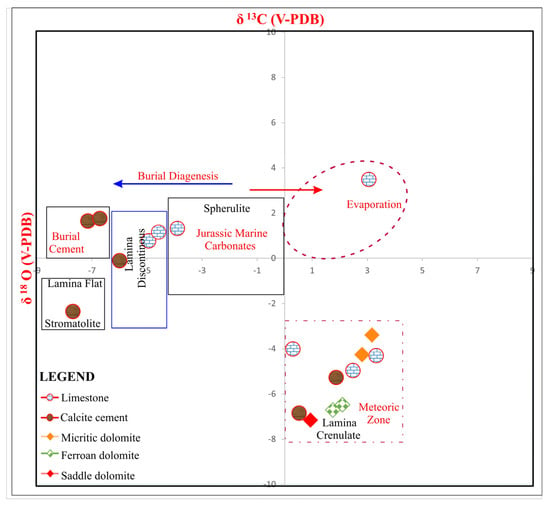

This study investigates microbial activities, shown by the wide distribution of carbon and oxygen isotopes for various microbial and diagenetic processes (Figure 7) [13]. Interestingly, replacive dolomite samples with organic matter validate the isotopic distribution of the spherulite in the shallow-burial phase of diagenesis, represented by negative carbon isotopic values, whereas the ferroan dolomite samples with crenulate laminae are associated with meteoric influx, as evident from depleted isotope values [43,44] (Figure 7). Meteoric diagenesis in shallow marine microbial carbonates shows that the sediments were later linked with post-depositional uplift in compressional tectonic settings [45,46]. Micritic dolomite with fine crystals having microbial laminae is the result of meteoric diagenesis, as represented by negative oxygen isotopic values. In contrast, discontinuous laminae in the limestone samples are interpreted to have developed during burial diagenesis (Figure 7). Similarly, fabric-destructive dolomite and saddle dolomite are included in the meteoric influx as evident from the distribution of oxygen and carbon isotope values.

Figure 7.

Scatter plot of isotope analysis of microbial carbonates found in the Jurassic sediments. Burial and meteoric diagenesis are associated with microbial carbonates. Crenulate laminae found in the microbial carbonates are linked with meteoric diagenesis, while discontinuous laminae and flat lamina fabrics of microbial carbonates are found in the burial phase of diagenesis [13].

4.4.1. Dolomitization

Field observations show that dolomitization is commonly present as bedding-parallel dolomitized zones, indicating that dolomitizing fluids penetrated laterally during the late phase of diagenesis (burial). Furthermore, no fluid escape structures were observed, which means that the rock was under intense pressure (overburden). Therefore, these fluids used lateral weak zones, for example, bedding planes or stylolites, for dolomitization (Figure 3a,d).

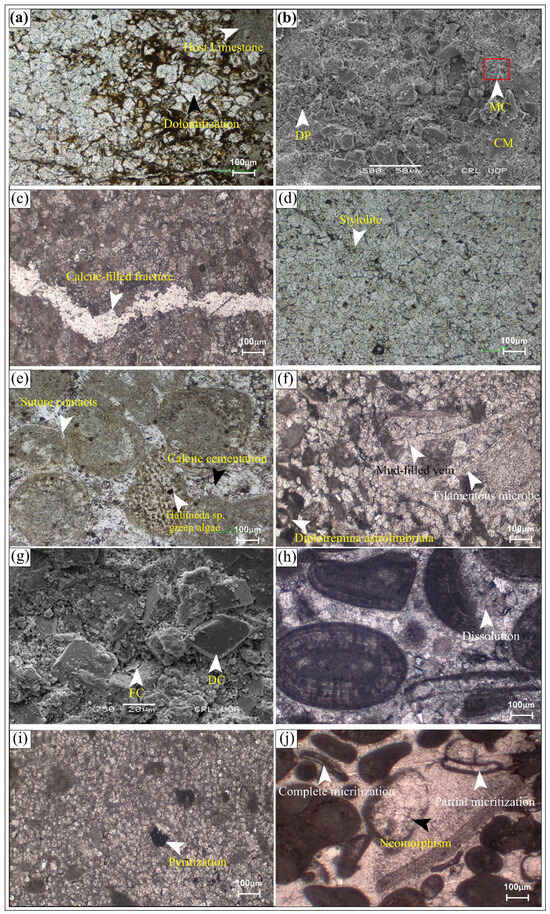

Petrographic observations showed variable sizes of dolomite crystals due to the multiphase dolomitization process that occurred during diagenesis. Dolomite crystals are euhedral to subhedral, with most crystals being well-developed, which means ample space was available for crystallization to proceed. The crystals were tightly packed with only 10%–15% micrite in the later stage. This microfacies showed signs of a pressure solution, as indicated by the presence of a low-amplitude stylolitized vein (Figure 8a). It is pertinent to mention here that dolomite occasionally fills the fractures to reduce the interconnected pore network [33,47], but the dolomite mineral replaces the calcite mineral, which results in enhanced porosity values [48,49,50].

Figure 8.

Diagenetic processes observed in carbonate successions: (a) Host limestone with dolomite rhombs of variable sizes; (b) SEM image showing diagenetic events including micritization (MC) and cementation (CM) in dolomitic limestone unit; (c) fractures that were later filled with calcite cement; (d) stylolites predating dolomitization; (e) combined diagenetic effect of compaction and cementation; (f) mud-filled vein showing few fractures and veins that were later filled by cementation; (g) SEM image indicating fracturing (FC) and dolomitization (DL); (h) ooidal grains are partially dissolved by dissolution that is later filled by cementation; (i) pyritization developed in dolomitic limestone; (j) neomorphism along with the partial to complete micritization identified in the microbial carbonates.

4.4.2. Micritization

Micritization represents an early diagenetic phase in the Jurassic carbonates. The presence of micrite within the host limestone cement and along the dolomite crystals (Figure 8a), and in SEM photomicrographs (Figure 8b) with micrite and cement, was observed, indicating that these phenomena occurred soon after deposition. This process preserved the original depositional texture and is therefore considered a fabric-retentive phenomenon in the early stage of diagenesis. The SEM analysis revealed that the dissolution porosity was developed at the early stage of the diagenesis process, contributing to the initial modification of the pore system. Neomorphism is often associated with micritization (Figure 8j), showing the complex interplay of various diagenetic processes in microbial carbonates.

4.4.3. Cementation

The cementation is mostly in the form of calcite overgrowth, as observed in petrographic data (Figure 4e). Another type of overgrowth was observed, containing a mosaic of calcite crystals (Figure 8e). Furthermore, cementation is rarely associated with sutured contacts, which indicates the initial compaction phenomenon prior to the cementation phase (Figure 4c). The removal of micrite was either due to high-energy conditions or the replacement of micrite by sparite during diagenesis.

4.4.4. Compaction/Stylolitization

Compaction (physical and chemical) occurred in the Jurassic microbial carbonates. The physical compaction is evident through tangential and planar sutured contacts, as seen in relatively high-energy carbonates where the support of lime mud is absent and grains are rounded to sub-rounded in morphology, where the developed fractures were partially filled by calcite or mud filling (Figure 8c,f). The fractures crosscut the dolomite crystals and diagenetic features in the later stage of diagenesis, while, on the other hand, chemical compaction occurred in the form of stylolitization (Figure 8d). This type of compaction in the rock enhances porosity by creating secondary pore networks or reduces it by pressure solution and mineral precipitation.

4.4.5. Dissolution

The dissolution process was observed in the exposed studied sections in the form of dissolution cavities in patchy dolomitic carbonate units (Figure 8h) and thick-bedded to massive limestone (Figure 10c) and intervals. Petrographic images of blue-dyed rock samples show brecciated intervals comprising isolated dissolution pores (Figure 10e), whereas SEM images show micro-level dissolution pores (Figure 8h). The dissolution expressions were observed in the form of megascopic to microscopic cavities, which greatly contributed to the development of pore networks in carbonate reservoirs.

4.4.6. Fracturing

Diagenetic processes are often associated with faults, fractures, and hydrothermal bodies, which reflect the tectonic stresses that have played a role in this study area. The occurrence of faults and fractures is widespread and frequent in the Chichali section of the Surghar Range (Figure 9), while they occur occasionally in the Kahi and Nathia Gali sections. The study area sections exhibit bedding-parallel dolomitization in the Nathia Gali section (Figure 3a and Figure 9). However, both bedding-parallel and bedding-perpendicular fracturing were observed in the Chichali section (Figure 9). These fracture sets facilitate fluid movement and dolomitization in carbonate reservoirs [51,52]. This observation is comparable to the Paleozoic rocks exposed in the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin, where a combined effect of sedimentary, tectonic, and metasomatic processes resulted in the development of dolomites [53]. It is noteworthy that secondary dolomites, owing to recrystallization diagenesis, often result in fabric-destructive dolomitization that acts as a barrier for the further growth of dolomite crystals [16].

Figure 9.

Field observations showing the faults and fractures found in shallow marine carbonates that are associated with dolomitization, resulting in enhanced permeability pathways for carbonate reservoirs: (a) A panoramic image of the Jurassic carbonates showing relative displacement within the succession, which is an indication of a fault line; (b) vertically inclined bedding planes with a small set of bedding-parallel fractures opened due to tectonic activity; (c) an outcrop image of the fractured dolomite in contact with the limestone; (d) both dissolution and fracturing phenomena positively affecting the reservoir character of the formation; (e) reservoir heterogeneity within the limestone succession—note that the fracture intensity is high in the lower part, while it is less prominent in the upper part of the outcrop; (f) dissolution and fracturing affecting the reservoir character of the formation.

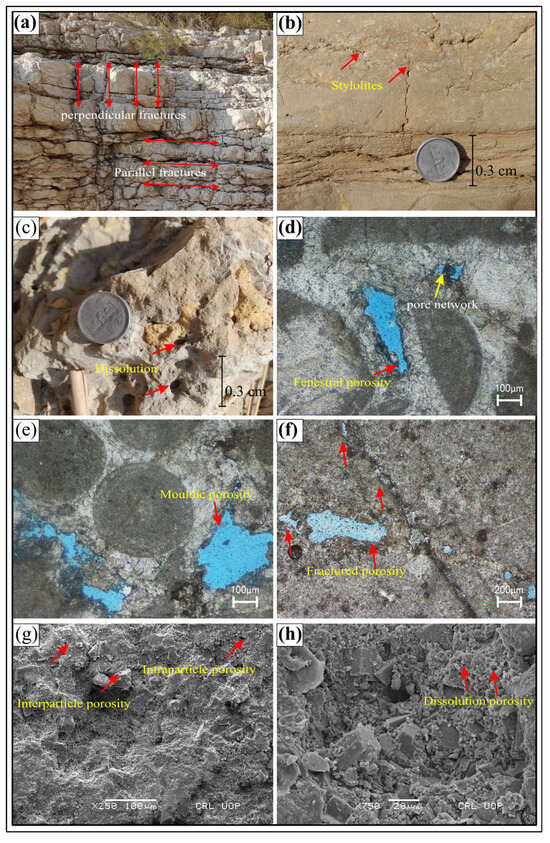

4.5. Reservoir Heterogeneity

The complex interplay of depositional fabric and diagenesis has a profound impact on evaluating the multiscale heterogeneities in these shallow marine carbonate reservoirs. The integrated field observations, thin-section petrography, and SEM data reveal depositional and diagenetic features affecting the pore network distribution (Figure 10) [54,55]. The fractures that developed in multiple directions were induced by diagenetic and tectonic activity, while the relationship between diagenesis and tectonics is further validated by the presence of stylolites that show both parallel and perpendicular trends [51]. The dissolution cavities are partially filled by dolomite patches that show the existence of residual, isolated pores contributing to an increase in the reservoir pores [51]. Petrographic data show various types of porosities developed by diagenesis and tectonic activity (Figure 10d–f). Dissolution porosity developed during diagenesis, whereas fracture porosity indicates the tectonic contribution in enhancing the pore network (Figure 9d–f). Furthermore, intercrystalline and intracrystalline porosities denote the multiple avenues of pore spaces that contribute to reservoir characterization. Intercrystalline porosity was related to sutured contacts, showing the compaction effect during the diagenetic phase (Figure 4c).

Figure 10.

Reservoir heterogeneity in microbial carbonates due to complex interplay of various depositional and diagenetic structures: (a) Bedding-parallel fractures along bedding planes were initially developed during deposition, while bedding perpendicular fractures developed as result of tectonic convergence; (b) stylolites developed in multiple directions, showing complex integration of diagenesis and tectonic activity; (c) dissolution pore partially filled with dolomite patches providing potential avenues for petroleum accumulation in carbonate reservoirs; (d) heterogeneous pore network collectively contributes to enhance bulk porosity in carbonate reservoirs; (e) non-skeletal fragments surrounded by mouldic porosity; (f) partially filled fractures allowing fluid to accumulate in pore network of carbonate reservoirs; (g) both interparticle and intraparticle porosities developed in carbonates during diagenesis; (h) carbonate reservoirs showing dissolution porosity, as identified in SEM images.

5. Discussion

5.1. Microbial Activity

The microbial carbonates show variable depositional settings due to the mixing of the meteoric and reflux dolomitization processes [56,57,58]. The mixing zones within shallow marine platforms could also be attributed to the structures, including faulting and fracturing (Figure 10), along which the fluid movement took place, providing the avenue for magnesium-rich minerals of the microbial carbonates [57,58,59,60]. Microbial features are associated with seepage-reflux dolomitization, shallow-burial diagenesis, and meteoric zones that facilitate the development of microbial dolomites [61,62]. The spherulite microbes in dolomites occur in micron-to-sub-micron-scale euhedral rhombs of dolomite crystals that are directly linked with burial [62,63]. In contrast, shallow burial supports the development of euhedral dolomites that depict the near-surface stabilizing conditions for microbial dolomite formation [16,43]. The well-preserved algal and stromatolite horizons in the Jurassic carbonates correspond to the high organic productivity in the Jurassic shallow marine environment [64].

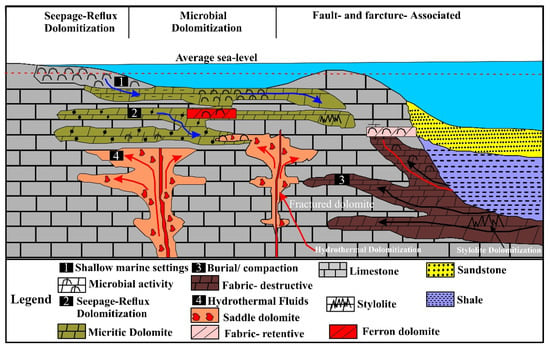

Microbial laminae are a common feature of microbialites. These laminae appear as thin, dark micritic layers [65,66]. However, in some instances, these can also be light in color and composed of sparite or dolomite crystals [67]. Seven types of microbial laminae are observed in the studied sections, which provide an insight into the mechanisms of formation of these microbial dolomites. The types of microbial lamina sets can be the result of various factors, such as the availability, diversity, and activities of the microbial community [68]. Similarly, water depth changes, environmental settings, nutrient availability, and salinity can also be the leading causes of sporadic or abundant microbial activity over time [68,69]. Diagenetic features and tectonic structures, such as fractures or faults, influenced the continuity of these laminae by altering rock properties such as porosity, permeability, and the penetration of dolomitizing fluids [7,70] (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

A conceptual depositional model for integrating diagenesis and tectonics in shallow marine microbial carbonates, modified after [71,72]. These microbial features are associated with seepage-reflux diagenesis, shallow-burial phase, faults, fractures, and bedding-perpendicular stylolites.

Discontinuous laminae of microbial activity were observed in the Jurassic carbonates and were patchy in appearance. Variations in the thickness of microbial laminae can be the result of changes in flow conditions or dissolution and cementation, which can also destroy their continuity during the later stages of diagenesis [73] (Figure 8). Uncommon stromatolites observed in these carbonates were smaller in size or poorly developed. This indicates very short-lived microbial mat growth with poor binding of the materials [74]. Flat laminae indicate persistence of flow conditions, primarily laminar flow. The spacing between individual laminae also appears to be uniform. These types of microbial features also propagate parallel, or at low angles, to the bedding surfaces. Crenulate laminae sets are also found either as a whole or as a part of the continuous, flat laminae sets. These crenulations indicate the persistence of wave/wind activity during the development of these laminae [75,76]. There appears to be no effect of diagenetic processes that could destroy the continuity of these lamina sets.

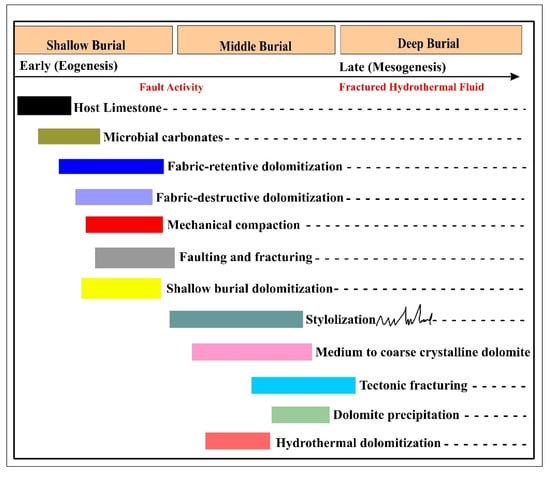

5.2. Paragenetic Sequence of Microbial Carbonates

The diagenesis of microbial carbonates is widespread and often associated with various post-depositional events [33]. The shallow-burial phase of diagenesis is linked to microbial growth in carbonate rocks, especially in dolomitic intervals. Fabric-retentive dolomitization is related to shallow burial, where the original fabric of rock is preserved, while fabric-destructive dolomitization is more prevalent in the middle phase of diagenesis, known as mesogenesis (Figure 12). Subsequently, fracturing, faulting, and stylolitization provide the avenue for the fluid migration and enrichment of magnesium that facilitate dolomite precipitation. Hydrothermal dolomitization in the later phase of diagenesis is least connected with microbial activity, owing to the restricted pressure–temperature conditions for the growth of microbes in the shallow marine environment [77].

Figure 12.

Early to late phases of diagenesis in shallow marine carbonates are occasionally related to microbial activity. Host limestone units were altered by dolomitization and mechanical compaction in the early phase of diagenesis, while fracturing and stylolitization at a later phase of diagenesis greatly impact the microbial carbonates.

The microbial signatures in the dolomites are linked to the shallow-burial phase of diagenesis. This diagenetic phase is responsible for microbial dolomite formation [16]. Shallow burial is also characterized by fabric-retentive dolomitization and ferroan dolomitization, in addition to microbial dolomitization. The middle burial phase, or mesogenesis, in the Jurassic carbonates hosts diverse diagenetic processes. Among these are ferroan dolomitization, stylolitization, tectonic fracturing, hydrothermal dissolution, and saddle dolomitization. The same processes continue further in the deeper burial, excluding ferroan dolomitization.

Fabric-retentive dolomitization takes place in closed-system conditions, which means the fluids involved in dolomitization are derived from within the same system instead of any foreign influence. There is no major volume change involved in this type of exchange of Mg ions, i.e., stoichiometric exchange of ions. Additionally, porosity is also somewhat similar in these types of dolomites, as in the originally deposited limestone. Ferroan dolomitization takes place in Mg-rich fluid, which also has iron content. This iron content is mostly derived from other sources of iron that lie outside the carbonate deposition system. The isotopic analysis is also comparable with the Jurassic carbonates of the Tethyan Ocean, including the Arabian Peninsula [78]. It shows extensive meteoric diagenesis associated with oceanic-water influx into the shallow marine platform. In this environmental setting, each fluid phase reactivated the fractures and faults, providing avenues for dolomitization [78]. Possible sources of iron may be the interaction of seawater with mafic rocks in the deep sea. In the case of Jurassic carbonates of the study area, considering the paleogeographic position, such events, known as Rajmahal traps [29], can be attributed to the enrichment of seawater with abundant magnesium and iron content. In this type of condition, ferroan dolomite is associated with stylolitized zones, and smectite–illite conversion can be the leading cause of the addition of iron. Other possible causes could be the increased temperature of seawater due to the Rajmahal traps [29].

Fabric-destructive dolomite, on the other hand, is associated with common dissolution, as is evident from dissolution seams. Other associated features include recrystallization and replacement by calcite. These features obliterate the depositional fabric of the entire rock. Generally, higher Mg/Ca ratios in the fluids favor the formation of fabric-destructive dolomite, where fracturing also facilitates the propagation of dolomitizing fluids deeper into the limestone units [79]. Other factors responsible for the destruction of fabric are temperature, pressure, and dolomitization. Saddle dolomitization takes place in deep burial, along with other associated diagenetic features including hydrothermal dissolution, stylolitization, and fracturing. This environment is dominated by compaction, where the major fluid source is hydrothermal. The presence of saddle dolomite is also used as an indicator that the rock has undergone a higher temperature range of 600–1500 °C.

Carbonate reservoirs exhibit a complex history of deposition and diagenetic processes. Furthermore, the subsequent impact of tectonics significantly altered the pore network distribution. The present work emphasizes the combined effect of depositional architecture and diagenetic phenomena that contribute to reservoir porosity and permeability. Key findings highlight the differential occurrence of bedding-parallel and bedding-perpendicular fractures that are indicative of depositional fabric and compressional tectonics, respectively. However, stylolites perpendicular to the bedding further strengthen the influence of convergent tectonics, which enhances the pore network in carbonate reservoirs. Intraformational faults interpreted at the outcrop level support the role of convergent tectonics in the studied stratigraphic interval in the Upper Indus Basin. This study emphasizes the implications of diagenesis and depositional fabric for reservoir characterization of shallow marine carbonates in sedimentary basins.

5.3. Coupling of Microbial Activity, Diagenesis, and Tectonics

The present study presents a complex interplay of microbial activity, diagenesis, and tectonics in shallow marine carbonates where diagenesis is often associated with numerous tectonic features, including multiple sets of fracturing, thrust faulting, and subsequent microbial fabrics. However, dissolution, dolomitization, and stylolitization provide the avenues for fluid flow that associate these diagenetic phenomena with microbial activity developed during the fluid movement in carbonate rocks. It is pertinent to mention here that carbonate rocks are often characterized mainly on the basis of diagenetic events, but the present work highlights the significance of both diagenesis and tectonics, which significantly impact microbial carbonates.

In microbial shallow marine carbonates especially associated with convergent tectonics, compressional forces are predominantly in control, and multiscale tectonic deformation is taking place alongside diagenetic modifications at different intervals. In such a scenario, fluid-controlled diagenesis, microbial activity, and tectonic structures play a major role in the evolution of carbonate rocks and their fabrics. It becomes further crucial to study the fabrics when the rock also bears enormous potential to hold hydrocarbons.

Multiple generations of fracture sets along major and minor faults have been observed at the outcrop level in Jurassic carbonates. These include both shattered rock zones where little or no in-filling is seen (indicating fairly younger events) as well as zones dominated by multidirectional veins filled by diagenetic fluids, primarily by calcite and clay minerals. The same effect is seen in the thin sections, as highlighted in the relevant sections. Swarms of stylolites are mostly parallel to bedding, although they are significant non-tectonic features that facilitate lateral migration of the fluids. However, multidirectional fractures are very crucial for localized hydrocarbon reservoir development and minimize further lateral migrations, as in the case of stylolites. In short, fluid flow is primarily controlled by these fracture sets in these Jurassic carbonates.

These structural pathways created due to heterogeneous tectonic forces also become avenues for different phases of diagenesis. Dolomitization, stylolitization, and dissolution are seen mostly following these weak zones, altering the porosity and permeability values. The association between these deformation and diagenetic features controls how diagenetic overprinting is distributed in these carbonates and the intensity of these processes.

Microbial features found in these carbonates also show a strong affinity to these structural pathways created or filled during different tectonic events. This indicates that microbial activity should either stimulate or sustain during this episodic migration of fluids. This is because the nutrient supply and geochemical conditions changed during these episodes, which either hinders or promotes the development of microbes. This means that microbial activity is also an active participant in diagenetic alteration of the rock fabric.

5.4. Study Limitations and Data Constraints

The study applied isotopic, petrographic, and SEM data to discuss diagenesis in microbial carbonates. The dataset highlights the impact of diagenesis on carbonate reservoirs, but it could be complemented with the following data for further research and validation for future petroleum exploration in the Upper Indus Basin:

- Analysis of associated fault systems and fracture networks in Jurassic carbonates would be very helpful in comprehending the fluid pathways created due to tectonic forces. These pathways act as zones of amplified permeability in carbonates, thus facilitating multifold secondary migration and reservoir characteristics of the strata. Microbial activity can then be related to these zones with the help of microbial-induced mineralization and micro-textures. This may prove helpful in correlating the development of microbial carbonates with fluid flow primarily induced by the tectonic activity. Such multidimensional methodology can highlight the effects of tectonics on fluid flow, the effects of these fluids on the diagenesis, and the response of microbial activity under the aforementioned conditions.

- Fluid inclusion microthermometry data should be supplemented with isotopic data to integrate the role of temperature and salinity of diagenetic fluids. This gives the thermal history and evolution of the fluids involved. We know that carbonate rocks that are deformed by fracturing and faulting can change the compositions as well as the temperature of the fluids. Both of these changes can influence the diagenesis alongside microbial activity in carbonate rocks.

- Geochemical proxies would strengthen the discussion pertaining to the composition of diagenetic fluids and carbonate minerals that could influence the pore network in the carbonate reservoirs. These proxies include elemental ratios of major and trace elements along with stable and radioactive isotopes. These data sets and analyses provide critical insights, primarily into rock–water interaction, which causes alterations during diagenetic processes. These alterations govern the processes of dissolution, cementation, and dolomitization. The creation, modification, and distribution of pore networks are also dependent on these mechanisms. Reservoir heterogeneities can be better studied by the integration of structural and petrographic data with these indicators.

- The present study only discussed the integration of various pore types with roles in diagenesis, which could impact reservoir characterization. However, comprehensive studies focusing on the calculation of porosity percentages in carbonates would refine reservoir studies of microbial carbonate rocks.

6. Conclusions

- The key findings of this study are informed by the occasional microbial activity in the Jurassic marine deposition that was previously thought to be least associated in the Upper Indus Basin, East Gondwana Margin. Microbial carbonates were intermittently found in the exposed Jurassic carbonate sections represented by microbial dolomite lithofacies and microbial dolomudstone microfacies.

- These microbial facies exhibit diagenetic features, including micritization and physical compaction, that took place during the shallow-burial phase. Therefore, diagenetic phenomena in ancient microbial carbonates also provide excellent sites for the integration of sedimentological, mineralogical, and geochemical signatures to explain the pore network distribution in carbonate reservoirs.

- Diagenetic processes including dolomitization and dissolution enhance reservoir pores, while calcite cementation and micritization inhibit the pore network. Moreover, fractures and bedding-perpendicular stylolitization also facilitate reservoir pore distribution.

- Reservoir heterogeneity is mainly controlled by dolomitization, dissolution, and fracturing found at the outcrop scale, seen in petrographic data and SEM images, where the combined effect of these diagenetic events enhances the reservoir quality of the microbial carbonates. Hence, this study recommends targeting reservoir intervals that have experienced the combined impact of fracturing, dissolution, and dolomitization, which are potential diagenetic events for enhanced pore network distribution and mainly serve as production targets for petroleum.

- The study also highlights the significant changes in paleoenvironmental conditions and subsequent diagenesis on the development of petroleum reservoirs that could provide an insight into re-evaluating the avenue of microbial carbonates in shallow marine environments, reconsidering the pore network distribution, and refining the reservoir potential of the marine Jurassic carbonates in this region.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.J. and I.U.; methodology, M.J., M.M. and H.U.R.; software, I.U. and M.J.; validation, I.K., H.U.R. and A.A.; formal analysis, M.M.; investigation, W.A. and F.S.; resources, M.J. and I.U.; data curation, H.U.R. and I.K.; writing—original draft preparation, I.U. and M.J.; writing—review and editing, A.A., M.U. (Muhammad Usman) and W.A.; visualization, F.S., and M.U. (Muhammad Umar); supervision, M.J. and W.A.; project administration, I.U.; funding acquisition, I.U. and M.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research work was partially funded by the COMSATS University Research Grant Program (CRGP), grant number 16-19/CRGP/CUI/ATD/24.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the reported results are already presented in this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors greatly acknowledge the technical comments and recommendations from three anonymous reviewers and an academic editor to revise the manuscript. The authors also appreciate the geological fieldwork assistance provided by Usama Arshad and Habib Ahmad.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Yan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Ma, D. Microbial carbonate reservoir characteristics and their depositional effects, the IV Member of Dengying Formation, Gaoshiti-Moxi area, Sichuan Basin, Southwest China. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 18965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Luo, Q.; Shi, K.; Liu, B.; Wang, Y.; Gao, X. Origin of a microbial-dominated carbonate reservoir in the Lower Cambrian Xiaoerbulake Formation, Bachu-Tazhong area, Tarim Basin, NW China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2021, 133, 105254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, D.; Li, Q.; Chen, H.; Wen, L.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, G.; Zhong, Y.; Wenzheng, L. Diagenetic evolution and cementation mechanism in deep Carbonate reservoirs: A case study of Dengying Fm. 2 in Penglai, Sichuan Basin, China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2024, 170, 107084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, K.; Liu, J. A petroliferous Ediacaran microbial-dominated carbonate reservoir play in the central Sichuan Basin, China: Characteristics and diagenetic evolution. Precambrian Res. 2023, 384, 106937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, C.C.; Madrucci, V.; Homewood, P.; Mettraux, M.; Ramnani, C.W.; Spadini, A.R. Stratigraphic and sedimentary constraints on presalt carbonate reservoirs of the South Atlantic Margin, Santos Basin, offshore Brazil. AAPG Bull. 2022, 106, 2513–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharhan, A.S.; Kendall, C.G.S.C.; Al-Suwaidi, A.S. Abstracts of the International Conferences on Evaporite Stratigraphy, Structure and Geochemistry, and their role in Hydrocarbon Exploration and Exploitation. GeoArabia 2008, 13, 141–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grotzinger, J.; Al-Rawahi, Z. Depositional facies and platform architecture of microbialite-dominated carbonate reservoirs, Ediacaran–Cambrian Ara Group, Sultanate of Oman. AAPG Bull. 2014, 98, 1453–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonk, R.; Bohacs, K.; Potma, K. The Spatial and Temporal Evolution of Mixed Carbonate-Clastic Mud-Dominated Basin Fill Successions: The Middle to Late Devonian Shelf Margin, Western Canada. Basin Res. 2025, 37, e70079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Yu, X.; Zhu, D.; Long, K.; Lu, C.; Zou, H. Depositional framework and reservoir characteristics of microbial carbonates in the fourth member of the middle Triassic Leikoupo Formation, western Sichuan Basin, South China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2023, 150, 106113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.; Reuning, L.; Amthor, J.E.; Kukla, P.A. Diagenetic Processes and Reservoir Heterogeneity in Salt-Encased Microbial Carbonate Reservoirs (Late Neoproterozoic, Oman). Geofluids 2019, 2019, 5647857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, S.; Wang, H. Autochthonous Dolomitization and Dissolution in the Microbial Carbonate Rocks of the Fengjiawan Formation in the Ordos Basin. Acta Geol. Sin. Engl. Ed. 2022, 96, 1376–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hattali, R.; Al-Sulaimani, H.; Al-Wahaibi, Y.; Al-Bahry, S.; Elshafie, A.; Al-Bemani, A.; Joshi, S.J. Fractured carbonate reservoirs sweep efficiency improvement using microbial biomass. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2013, 112, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahniuk, A.M.; Anjos, S.; França, A.B.; Matsuda, N.; Eiler, J.; McKenzie, J.A.; Vasconcelos, C. Development of microbial carbonates in the Lower Cretaceous Codó Formation (north-east Brazil): Implications for interpretation of microbialite facies associations and palaeoenvironmental conditions. Sedimentology 2015, 62, 155–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosence, D.; Gibbons, K.; Heron, D.P.L.; Morgan, W.A.; Pritchard, T.; Vining, B.A. Microbial carbonates in space and time: Introduction. In Microbial Carbonates in Space and Time: Implications for Global Exploration and Production; Geological Society London: London, UK, 2015; Volume 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Hu, S.; Zhao, W.; Xu, Z.; Shi, S.; Fu, Q.; Zeng, H.; Liu, W.; Fall, A. Diagenesis and its impact on a microbially derived carbonate reservoir from the Middle Triassic Leikoupo Formation, Sichuan Basin, China. AAPG Bull. 2018, 102, 2599–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrash, D.A.; Bialik, O.M.; Bontognali, T.R.R.; Vasconcelos, C.; Roberts, J.A.; McKenzie, J.A.; Konhauser, K.O. Microbially catalyzed dolomite formation: From near-surface to burial. Earth Sci. Rev. 2017, 171, 558–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilei, C.; Shunshe, L.; Shangfeng, Z.; Jianfeng, Z.; Jingao, Z.; Qiqi, L.; Xinshan, W. Discovery of Microbial Mounds and Its Geological Significance. Chem. Technol. Fuels Oils 2023, 59, 1112–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Bai, B.; Bai, Y.; Lu, X.; Zhang, B.; Qin, S.; Song, J.; Jiang, Q.; Huang, S. Fluid evolution and hydrocarbon accumulation model of ultra-deep gas reservoirs in Permian Qixia Formation of northwest Sichuan Basin, SW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2022, 49, 719–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Shen, A.; Pan, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X. Features, origin and distribution of microbial dolomite reservoirs: A case study of 4th Member of Sinian Dengying Formation in Sichuan Basin, SW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2017, 44, 745–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Liu, S.; Li, Z.; Yang, D.; Sun, W.; Lin, T.; Wang, H.; Yu, Y.; Long, Y.; Luo, P. Porosity in Microbial Carbonate Reservoirs in the Middle Triassic Leikoupo Formation (Anisian Stage), Sichuan Basin, China. Carbonate Pore Syst. New Dev. Case Stud. 2019, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yong, Z.; Song, J.; Lin, T.; Yu, Y. Microbialite Textures and Their Geochemical Characteristics of Middle Triassic Dolomites, Sichuan Basin, China. Processes 2023, 11, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Zhao, J.; Su, Z.; Wei, X.; Ren, J.; Huang, Z.; Wu, C. Distribution and depositional model of microbial carbonates in the Ordovician middle assemblage, Ordos Basin, NW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2021, 48, 1341–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, T.; Lei, B.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Yong, J. Origin and characteristics of grain dolomite of Ordovician Ma55 Member in the northwest of Ordos Basin, NW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2019, 46, 1182–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jiang, H.-X.; Wu, Y.-S.; Pan, W.-Q.; Zhang, B.-S.; Sun, C.-H.; Yang, G. Macro- and microfeatures of Early Cambrian dolomitic microbialites from Tarim Basin, China. J. Palaeogeogr. 2021, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Luo, P.; Yang, S.; Yang, D.; Zhou, C.; Li, P.; Zhai, X. Reservoirs of Lower Cambrian microbial carbonates, Tarim Basin, NW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2014, 41, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, H.; Khaz’ali, A.R.; Mehrabani-Zeinabad, A.; Jazini, M. Investigating the potential of microbial enhanced oil recovery in carbonate reservoirs using Bacillus persicus. Fuel 2023, 334, 126757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, M.; Ullah, I.; Rahim, H.U.; Khan, I.; Abbas, W.; Rehman, M.U.; Rashid, A.; Umar, M.; Ali, A.; Siddiqui, N.A. Tracking Depositional Architecture and Diagenetic Evolution in the Jurassic Carbonates, Trans Indus Ranges, NW Himalayas. Minerals 2024, 14, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, H.U.; Shah, M.M.; Khalil, R.; Jamil, M. Evaluation of fault and fracture controlled hydrothermal dolomitization in the Jurassic carbonate succession of the lesser Himalayas, NW Pakistan. Carbonates Evaporites 2025, 40, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, H.U.; Qamar, S.; Shah, M.M.; Corbella, M.; Martín-Martín, J.D.; Janjuhah, H.T.; Navarro-Ciurana, D.; Lianou, V.; Kontakiotis, G. Processes associated with multiphase dolomitization and other related diagenetic events in the Jurassic Samana Suk Formation, Himalayan Foreland Basin, NW Pakistan. Minerals 2022, 12, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.M.S.S.; Jadoon, Q.A.; Umar, M.; Khan, A.A. Sedimentary evolution of middle Jurassic epeiric carbonate ramp Hazara Basin Lesser Himalaya Pakistan. Carbonates Evaporites 2021, 36, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadood, B.; Khan, S.; Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Ahmad, S.; Jiao, X. Sequence Stratigraphic Framework of the Jurassic Samana Suk Carbonate Formation, North Pakistan: Implications for Reservoir Potential. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2021, 46, 525–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzeb, M.; Shah, M.M.; Rahim, H.U.; Jan, J.A.; Ahmad, I.; Khalil, R.; Shehzad, K. Depositional and diagenetic studies of the middle Jurassic Samana Suk Formation in the Trans Indus Ranges and western extension of Hill Ranges, Pakistan: An integrated sedimentological and geochemical approach. Carbonates Evaporites 2024, 39, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, J. Dolomite: Occurrence, evolution and economically important associations. Earth Sci. Rev. 2000, 52, 1–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattak, S.A.; Khan, N.; Khan, W.; Dhas, S.S.J.; Kontakiotis, G.; Islam, I.; Janjuhah, H.T.; Antonarakou, A. Sedimentology and reservoir characterisation of Lower Jurassic clastic sedimentary rocks, Salt and Trans Indus Ranges, Pakistan: Evidence from petrography, scanning electron microscopy and petrophysics. Depos. Rec. 2025, 11, 698–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsan, M.; Latif, M.A.U.; Ali, A.; Radwan, A.E.; Amer, M.A.; Abdelrahman, K. Geocellular Modeling of the Cambrian to Eocene Multi-Reservoirs, Upper Indus Basin, Pakistan. Nat. Resour. Res. 2023, 32, 2583–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, A.; Yang, R.; Janjuhah, H.T.; Mughal, M.S.; Li, Y.; Kontakiotis, G.; Lenhardt, N. Microfacies analysis of the Palaeocene Lockhart limestone on the eastern margin of the Upper Indus Basin (Pakistan): Implications for the depositional environment and reservoir characteristics. Depos. Rec. 2023, 9, 152–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, F.H.; Tunio, A.H.; Memon, K.R.; Mahesar, A.A.; Abbas, G. Unveiling the Diagenetic and Mineralogical Impact on the Carbonate Formation of the Indus Basin, Pakistan: Implications for Reservoir Characterization and Quality Assessment. Minerals 2023, 13, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahad, M.; Khan, M.A.; Hussain, J.; Ahmed, A.; Yar, M. Microfacies analysis, depositional settings and reservoir investigation of Early Eocene Chorgali Formation exposed at Eastern Salt Range, Upper Indus Basin, Pakistan. Carbonates Evaporites 2021, 36, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, A.; Khan, M.R.; Wahid, A.; Iqbal, M.A.; Rezaee, R.; Ali, S.H.; Erdal, Y.D. Petroleum System Modeling of a Fold and Thrust Belt: A Case Study from the Bannu Basin, Pakistan. Energies 2023, 16, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, K.A.; Rizwan, M.; Janjuhah, H.T.; Islam, I.; Kontakiotis, G.; Bilal, A.; Arif, M. An integrated petrographical and geochemical study of the Tredian Formation in the Salt and Trans-Indus Surghar ranges, North-West Pakistan: Implications for palaeoclimate. Depos. Rec. 2024, 10, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, M.; Latif, K.; Zafar, T.; Xiao, E.; Ghazi, S. Morphology and genesis of the Cambrian oncoids in Wuhai Section, Inner Mongolia, China. Carbonates Evaporites 2021, 37, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, E.; Riaz, M.; Zafar, T.; Latif, K. Cambrian marine radial cerebroid ooids: Participatory products of microbial processes. Geol. J. 2021, 56, 4627–4644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhold, C. Multiple episodes of dolomitization and dolomite recrystallization during shallow burial in Upper Jurassic shelf carbonates: Eastern Swabian Alb, southern Germany. Sediment. Geol. 1998, 121, 71–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauck, T.E.; Corlett, H.J.; Grobe, M.; Walton, E.L.; Sansjofre, P. Meteoric diagenesis and dedolomite fabrics in precursor primary dolomicrite in a mixed carbonate–evaporite system. Sedimentology 2018, 65, 1827–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elhameed, M.; Attia, G.; Salama, Y.; El-Moghazy, A.; Mahmoud, A. Microfacies analysis and diagenetic history of Lower to Middle Eocene carbonates at Umm Russies area in the northeastern desert of Egypt. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 20159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qamar, S.; Shah, M.M.; Janjuhah, H.T.; Kontakiotis, G.; Shahzad, A.; Besiou, E. Sedimentological, Diagenetic, and Sequence Stratigraphic Controls on the Shallow to Marginal Marine Carbonates of the Middle Jurassic Samana Suk Formation, North Pakistan. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purser, B.H.; Brown, A.; Aissaoui, D.M. Nature, Origins and Evolution of Porosity in Dolomites. In Dolomites; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1994; pp. 281–308. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, M.A.; Timms, N.E.; Hough, R.M.; Cleverley, J.S. Reaction mechanism for the replacement of calcite by dolomite and siderite: Implications for geochemistry, microstructure and porosity evolution during hydrothermal mineralisation. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 2013, 166, 995–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, S.E.; Gregg, J.M.; Bish, D.L.; Machel, H.G.; Fouke, B.W. Dolomite, Very High-Magnesium Calcite, and Microbes—Implications for The Microbial Model of Dolomitization. SEPM Spec. Publ. 2017, 109, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.Q. Dolomite Reservoirs: Porosity Evolution and Reservoir Characteristics. AAPG Bull. 1995, 79, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli, V. Macroscopic Heterogeneity. In Carbonate Reservoir Heterogeneity: Overcoming the Challenges; Tavakoli, V., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 69–96. [Google Scholar]

- Tavakoli, V. Microscopic Heterogeneity. In Carbonate Reservoir Heterogeneity: Overcoming the Challenges; Tavakoli, V., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 17–51. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick, C.A.; Corlett, H.; Clog, M.; Boyce, A.J.; Tartèse, R.; Steele-MacInnis, M.; Hollis, C. Basin scale evolution of zebra textures in fault-controlled, hydrothermal dolomite bodies: Insights from the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin. Basin Res. 2023, 35, 2010–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli, V. Reservoir Heterogeneity: An Introduction. In Carbonate Reservoir Heterogeneity: Overcoming the Challenges; Tavakoli, V., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Correia, M.G.; Maschio, C.; Schiozer, D.J. Integration of multiscale carbonate reservoir heterogeneities in reservoir simulation. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2015, 131, 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Gao, D.; Ngia, N.R.; Hu, M.; Zhao, S. Influence of sea-level changes and dolomitization on the formation of high-quality reservoirs in the Cambrian Longwangmiao Formation, central Sichuan basin. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2025, 15, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Shi, Z.; Tian, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, W. Petrological and geochemical constraints on the origin of dolomites: A case study from the early Cambrian Qingxudong Formation, Sichuan Basin, South China. Carbonates Evaporites 2019, 34, 1639–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worden, R.H.; Armitage, P.J.; Butcher, A.R.; Churchill, J.M.; Csoma, A.E.; Hollis, C.; Lander, R.H.; Omma, J.E. Petroleum reservoir quality prediction: Overview and contrasting approaches from sandstone and carbonate communities. Reserv. Qual. Clastic Carbonate Rocks Anal. Model. Predict. 2018, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nader, F.H.; Swennen, R.; Ellam, R. Reflux stratabound dolostone and hydrothermal volcanism-associated dolostone: A two-stage dolomitization model (Jurassic, Lebanon). Sedimentology 2004, 51, 339–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, D.T.; Oren, A. Nonphotosynthetic Bacteria and the Formation of Carbonates and Evaporites Through Time. Geomicrobiol. J. 2005, 22, 27–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Wang, W. Seepage reflux dolomitization and telogenetic karstification in Majiagou Formation in the Ordos Basin, China. Geol. J. 2019, 54, 2145–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Shen, A.; Qiao, Z.; Pan, L.; Hu, A.; Zhang, J. Genetic types and distinguished characteristics of dolomite and the origin of dolomite reservoirs. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2018, 45, 983–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perri, E.; Tucker, M. Bacterial fossils and microbial dolomite in Triassic stromatolites. Geology 2007, 35, 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coimbra, R.; Immenhauser, A.; Olóriz, F. Spatial geochemistry of Upper Jurassic marine carbonates (Iberian subplate). Earth Sci. Rev. 2014, 139, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas, C.; Pomar, L. Microbial deposits in upper Miocene carbonates, Mallorca, Spain. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2010, 297, 465–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.A.; Sumner, D.Y. Variations in Neoarchean microbialite morphologies: Clues to controls on microbialite morphologies through time. Sedimentology 2008, 55, 1189–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vescogni, A.; Colombo, F.; Guido, A. New Insights into Upper Messinian Microbial Carbonates: A Dendrolite-Thrombolite Build-Up from the Salento Peninsula, Central Mediterranean. Geobiology 2025, 23, e70023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riding, R. Microbial carbonates: The geological record of calcified bacterial–algal mats and biofilms. Sedimentology 2000, 47, 179–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutti, M.; Hallock, P. Carbonate systems along nutrient and temperature gradients: Some sedimentological and geochemical constraints. Int. J. Earth Sci. 2003, 92, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrenberg, S.N.; Eberli, G.P.; Keramati, M.; Moallemi, S.A. Porosity-permeability relationships in interlayered limestone-dolostone reservoirs. AAPG Bull. 2006, 90, 91–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nader, F.H.; De Boever, E.; Gasparrini, M.; Liberati, M.; Dumont, C.; Ceriani, A.; Morad, S.; Lerat, O.; Doligez, B. Quantification of diagenesis impact on the reservoir properties of the Jurassic Arab D and C members (Offshore, U.A.E.). Geofluids 2013, 13, 204–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, K.; Liu, B. Sedimentary structures of microbial carbonates in the fourth member of the Middle Triassic Leikoupo Formation, Western Sichuan Basin, China. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flügel, E. Diagenesis, Porosity, and Dolomitization. In Microfacies of Carbonate Rocks: Analysis, Interpretation and Application; Flügel, E., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 267–338. [Google Scholar]

- Immenhauser, A.; HillgÄRtner, H.; Van Bentum, E. Microbial-foraminiferal episodes in the Early Aptian of the southern Tethyan margin: Ecological significance and possible relation to oceanic anoxic event 1a. Sedimentology 2005, 52, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaut, R.W. Morphology, distribution, and preservation potential of microbial mats in the hydromagnesite-magnesite playas of the Cariboo Plateau, British Columbia, Canada. Hydrobiologia 1993, 267, 75–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partha Pratim, C.; Priyabrata, D.; Subhojit, S.; Kaushik, D.; Shruti Ranjan, M.; Pritam, P. Microbial mat related structures (MRS) from Mesoproterozoic Chhattisgarh and Khariar basins, Central India and their bearing on shallow marine sedimentation. Int. Union Geol. Sci. 2012, 35, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, N.; Mansurbeg, H.; Kolo, K.; Préat, A. Hydrothermal Carbonate Mineralization, Calcretization, and Microbial Diagenesis Associated with Multiple Sedimentary Phases in the Upper Cretaceous Bekhme Formation, Kurdistan Region-Iraq. Geosciences 2019, 9, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mojel, A.; Dera, G.; Razin, P.; Le Nindre, Y.-M. Carbon and oxygen isotope stratigraphy of Jurassic platform carbonates from Saudi Arabia: Implications for diagenesis, correlations and global paleoenvironmental changes. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2018, 511, 388–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Shang, J.; Shen, A.; Wen, L.; Wang, X.; Xu, L.; Liang, F.; Liu, X. Episodic hydrothermal alteration on Middle Permian carbonate reservoirs and its geological significance in southwestern Sichuan Basin, SW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2024, 51, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.