Abstract

The cement industry’s significant carbon footprint has driven research into sustainable alternatives like alkali-activated materials (AAMs). This study investigates the synergistic effect of blending copper–nickel slag (CNS) with fly ash (FA) to produce high-performance AAMs. Mechanically activated mixtures of CNS and FA, with FA content varying from 0 to 100%, were alkali-activated with sodium silicate. A distinct synergy was observed, with the blend of 80% CNS and 20% FA (AACNS–80) achieving the highest compressive strength (99.9 MPa at 28 days), significantly outperforming the single-precursor systems. Analytical techniques including thermogravimetry, FTIR spectroscopy, and SEM–EDS were used to elucidate the mechanisms behind this enhancement. The results indicate that the AACNS–80 formulation promotes a greater extent of reaction and forms a denser, more homogeneous microstructure. The synergy is attributed to an optimal particle packing density and the co-dissolution of precursors, leading to the formation of a complex gel that incorporates magnesium and iron from the slag. This work demonstrates the potential for valorizing copper–nickel slag in the production of high-strength, sustainable binders.

1. Introduction

The cement industry is a significant contributor to global anthropogenic CO2 emissions, with Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC) production alone responsible for approximately 7%–8% of the total worldwide [1]. This significant environmental impact has accelerated the search for sustainable alternative binders [1,2]. Among the most promising candidates are alkali-activated materials (AAMs), a broad class of binders that include geopolymers, which are typically derived from low-calcium aluminosilicate precursors. AAMs are inorganic polymers synthesized through the reaction of solid aluminosilicate sources (e.g., industrial by-products or calcined clays) with alkaline activators [3]. Unlike OPC, which relies on the energy-intensive calcination of limestone (CaCO3)—a primary source of process emissions—the synthesis of AAMs generally avoids this step, operating at lower processing temperatures [4]. Beyond their environmental benefits, AAMs demonstrate a suite of superior engineering properties, including high early and ultimate compressive strength, exceptional resistance to elevated temperatures, and improved durability against acid and sulfate attack, positioning them as a viable high-performance and greener construction material for the future [5].

Non-ferrous metallurgy is a cornerstone of global industrial development, supplying essential metals for infrastructure, technology, and clean energy applications. A significant environmental byproduct of this industry is smelting non-ferrous metallurgy slag (NFMS), a silicate- and oxide-rich residue generated during the pyrometallurgical extraction of metals. The global volume of this waste is substantial. Current estimates indicate that hundreds of millions of tonnes of smelting slags are produced annually worldwide, with a large fraction still being disposed of in landfills or stockpiled without valorization, leading to significant environmental management challenges [6]. AAMs present a transformative pathway for the valorization of these abundant metallurgical wastes [7,8]. The chemical profile of these slags, often rich in silicon, aluminum, iron, and magnesium makes them suitable solid precursors for the synthesis of gels that form the binding phase in AAMs [8,9,10]. The conversion of these wastes into construction materials directly supports the principles of a circular economy by diverting material from landfills, conserving natural resources, and reducing the carbon footprint associated with conventional cement production.

The combination of NFMS with fly ash (FA) has proven effective for enhancing the strength of AAMs. Examples in the literature include AAMs prepared from lead slag [11], high-magnesium nickel slag [12,13], and ground ferronickel slag [14], all of which exhibit improved mechanical properties when blended with FA. This research presents the first investigation into the impact of combining FA with granulated copper–nickel slag (CNS) on the performance of AAM produced. The landfilling of CNS, which contains heavy metals like copper, nickel, and chromium, occupies large territories and poses a serious environmental risk [15,16].

Zhang et al. [17] and Yang et al. [18] investigated alkali activation of CNS in combination with ground-granulated blast furnace slag (GGBFS). CNS used in these studies was composed of crystalline-phase fayalite (72.42%) and an amorphous glass phase (27.58%). Sodium silicate content was 7.0% and the modulus of sodium silicate solution was 1.0. Water to solid ratio was 0.23. Curing was at a temperature of 20 °C and a humidity of more than 90%. When the ratio CNS:GGBFS was 70:30, the 28 d compressive strength of the binder was 84 MPa [17]. In case the ratio CNS:GGBFS was 50:49, the 28-day strength increased to 125 MPa [18].

CNS from the same smelter was used for preparation of AAM without mineral additives [16]. The modulus of sodium silicate solution was 3.0 and the curing temperature was 25 °C. Under the standard curing humidity (95%) the optimum content of sodium silicate was 8%, with the compressive strength of 17 MPa at a curing period of 28 days.

A potential drawback of NFMS and FA is their relatively low reactivity with alkaline agents, which is governed by their specific surface area (particle size) and the amount and composition of their glass phases. Numerous publications report that mechanical activation (MA) is an effective method for enhancing precursor reactivity in AAM synthesis [17,19,20,21,22]. Mechanically treating solids in mills not only reduces particle size (increasing specific surface area) but also increases the amount of the amorphous phase and generates structural defects, which are critical factors in boosting reactivity [23]. In this study, MA was applied to mixtures of CNS and FA to increase their reactivity.

Our results demonstrate that combining copper–nickel slag (CNS) with fly ash (FA) is an effective strategy for enhancing the performance of alkali-activated materials (AAMs). Specifically, a mixture of 80% CNS and 20% FA yielded a compressive strength of 99.9 MPa after 28 days of curing, significantly surpassing the strength of binders formulated with 100% FA or 100% CNS alone.

This study employs a conventional two-part formulation, using liquid glass as the alkaline activator. While one-part (“just add water”) formulations are recognized as more practical for in situ applications [24,25,26,27], a fundamental understanding of precursor interactions—best achieved through the precise control offered by two-part systems—remains a critical prerequisite. Such knowledge is essential for the rational design and optimization of effective, commercially viable one-part mixes.

2. Materials and Methods

Low-calcium FA (Class F) was sampled from the Apatity thermal power plant (Murmansk region, Russia). The main crystalline phases in the FA are quartz and mullite. CNS—granulated (water-quenched) Cu-Ni slag—was obtained from smelter plant of Kola Mining and Metallurgical Company (Murmansk Region, Russia). The slag mainly consists of magnesia–ferriferous glass with minor amount of the crystalline phases of olivine group minerals (2–5 wt.%) and ore minerals (~1 wt.%). The CNS sample was of the same type as that employed in a previous study [15], although it was derived from a different batch. A more detailed description of the slag is provided in [15]. Chemical composition of the FA and CNS is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Chemical compositions of the FA and CNS (wt.%).

MA was carried out in an AGO-2 laboratory planetary mill (Novic, Novosibirsk, Russia) at a centrifugal force of 40 g, in air, using steel vials and steel balls 8 mm in diameter as the milling bodies. The ratio of the mass of the balls to the mass of load was 6 (240 g of balls and 40 g of load in each vial). MA was carried out batchwise for 3 min. The MA time of 3 min was chosen based on prior optimization work with the individual components. Specifically, our grinding curve analyses for 100% CNS [28] and 100% FA [29] in the identical planetary mill identified 3 min as the point that optimally enhances precursor reactivity for AAMs preparation. This duration maximizes the beneficial surface area increase avoiding the detrimental agglomeration that occurs with longer times and leads to achieving high AAM strength. This established optimal parameter was thus directly applied to the blended CNS + FA precursors in this study.

Sodium liquid glass (modulus 1.6) was used as the alkaline agent. Chemical composition of liquid glass (wt.%): SiO2—22.53, Na2O—14.53, and H2O—62.94. The mass ratio of Na2O (present in liquid glass) to the mechanically activated (CNS + FA) mixtures in the paste was equal to 0.05. The water content was adjusted to ensure the same workability of the pastes, so the water content varies. Due to the small batch size, workability was adjusted qualitatively by incremental water addition to achieve a consistent, cohesive, and moldable paste across all mixes. The water to solid ratio (w/s) was determined taking into account the amount of water present in the liquid glass. Table 2 shows the composition of the mixtures used for preparation of the pastes. The (CNS + FA) mixtures are denoted as CNS-X, where X is the CNS content in the mixture, wt.%. For example, CNS-20 denotes the mixture containing 20% CNS and 80% FA. The AAM, synthesized using the CNS-20 mixture, is referred to as AACNS-20.

Table 2.

Composition and specific surface area of mixtures used for preparation of AAMs (Sp—BET specific surface area, w/s—water-to-solid ratio).

The specific surface area (Ssp) of the mechanically activated (CNS + FA) mixtures was measured using the nitrogen BET method with a Micromeritics Flow-Sorb II 2300 instrument (Micromeritics, Norcross, GA, USA), as well as by the Blaine method (Table 2). Thermogravimetric (TG) analysis was carried out on an HQT-4 device (Beijing Henven Experimental Equipment Co., Ltd., 2022, Beijing, China) in argon flow, with a heating rate was 10 °C/min. Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were recorded on a Rigaku Miniflex-600 instrument (Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan) using Cu–Kα radiation at a rate of 2°(2θ) per minute. Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were obtained with a Nicolet 6700 FTIR spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) using potassium bromide tablets. SEM-EDS analysis of the AAMs was performed using a ZEISS EVO 25 scanning electron microscope (equipped with an UltimMax 170 EDS detector) (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) operated at 20 kV. The AAMs specimens for SEM analysis were taken after mechanical testing. The particle size distribution was determined using a SALD-201V (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) laser diffraction particle size analyzer.

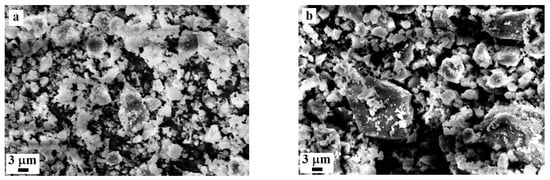

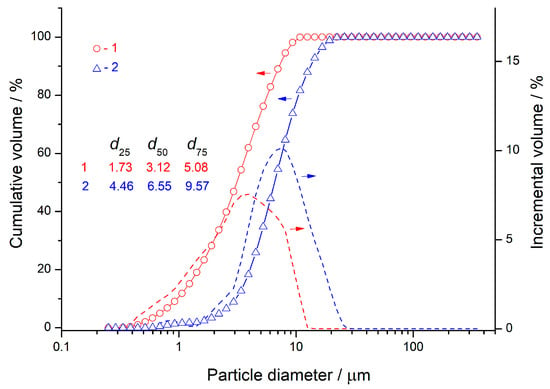

Figure 1 presents SEM images of CNS-0 and CNS-100, and Figure 2 shows their particle size distributions. The distribution in Figure 2 demonstrates that the 100% slag precursor (CNS-100) is coarser than the 100% FA precursor (CNS-0). This conclusion agrees with the SEM images in Figure 1 and the specific surface area measurements in Table 2.

Figure 1.

(a) SEM images of precursors: CNS-0 (100% FA) and (b) CNS-100 (100% CNS).

Figure 2.

Particle size distribution: CNS-0 (100% FA) (1) and CNS-100 (100% CNS) (2).

The pastes were cast into 1.41 × 1.41 × 1.41 cm molds. Specimens were cured in a relative humidity of 95 ± 5% at 22 ± 2 °C for 24 h. After demolding, the specimens were further cured in a climatic chamber to testing time under the same conditions as applied in the first 24 h until testing. Compressive strength data were obtained from an average of three samples after 7 and 28 days.

3. Results

3.1. Mechanical Properties

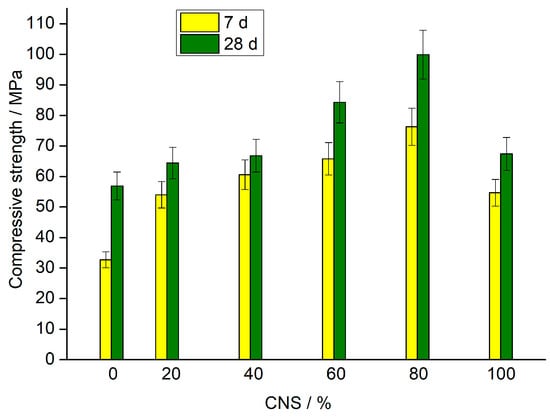

Figure 3 shows the compressive strength of the AAMs at 7 and 28 days as a function of the (CNS + FA) mixture composition. A distinct synergistic effect is observed, with the blend of 80% CNS and 20% FA (AACNS-80) achieving the highest strength. This mixture significantly outperformed the single-precursor systems, AACNS-0 (100% FA) and AACNS-100 (100% CNS). The 7-day compressive strengths for AACNS-0, AACNS-80, and AACNS-100 were 32.7, 76.3, and 54.7 MPa, respectively, increasing to 56.9, 99.9, and 67.4 MPa after 28 days of curing.

Figure 3.

Effect of the (CNS + FA) mixture composition on the 7th- and 28th-day compressive strengths of AAMs.

The following subsections compare the 28-day synergistic “peak” specimen, AACNS-80, with its end-members (AACNS-0 and AACNS-100). The comparison is based on TG, XRD, FTIR spectroscopy, and SEM-EDS analyses.

3.2. TG, XRD, and FTIR Spectroscopy Analyses

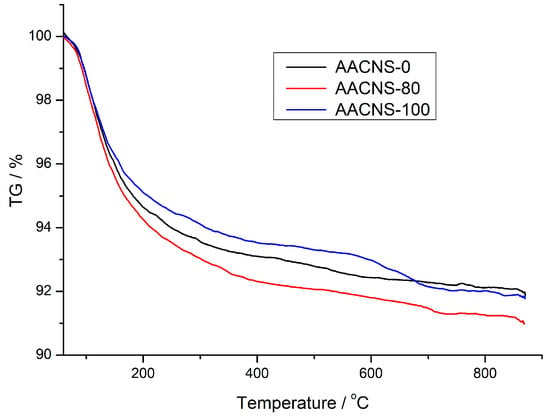

Figure 4 presents the TG data for the AACNS-0, AACNS-80, and AACNS-100 cured for 28 days.

Figure 4.

Thermogravimetric (TG) curves of the AACNS-0, AACNS-80, and AACNS-100 cured for 28 days.

Mass loss below 250–300 °C is attributed to the removal of free and physically bound water from aluminosilicate hygrogel, the reaction product of alkali activation. Above this range, up to approximately 600 °C, mass loss primarily results from dehydroxylation [30,31]. A further temperature increase beyond 600 °C leads to weight loss from carbonate decomposition. These carbonates are present in the AAMS due to the reaction of the alkaline agent with atmospheric carbon dioxide [29,32].

The total mass loss below 600 °C is greatest for AACNS-80 (8.20 wt.%), followed by AACNS-0 (7.57 wt.%) and AACNS-100 (7.02 wt.%). A similar trend is seen in the dehydroxylation region (250–600 °C): AACNS-80 (1.73 wt.%) > AACNS-0 (1.56 wt.%) > AACNS-100 (1.53 wt.%). Although the chemical composition of the gel varies between the samples due to differing precursor materials, the mass loss below 600 °C roughly reflects the extent of gel formation. The TG data (Figure 4) suggest that the greatest amount of gel formed in AACNS-80, which also exhibits the highest compressive strength (Figure 3).

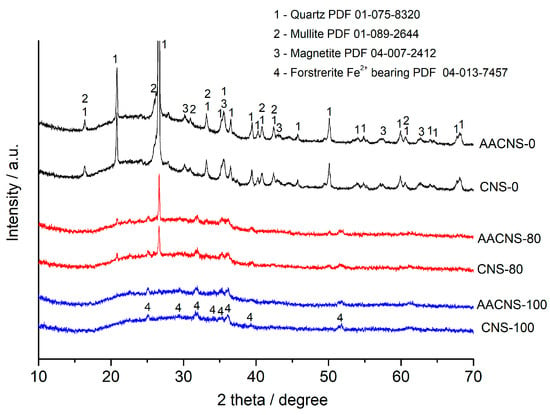

Figure 5 displays the XRD patterns of the AACNS-0, AACNS-80, and AACNS-100 cured for 28 days and the corresponding precursors.

Figure 5.

XRD patterns of the AACNS-0, AACNS-80, and AACNS-100 cured for 28 days and their precursors, CNS-0, CNS-80, and CNS-100.

In the XRD pattern of the AACNS-0 produced from 100% FA, no new peaks appear which indicates the amorphous nature of the geopolymer synthesis product (N-A-S-H gel). Similar results were obtained for the AAMs based on the CNS-80 and CNS-100. The absence of new crystalline peaks in the XRD patterns of AACNS-80 and AACNS-100 (Figure 5) indicates that the products of alkali-activation are amorphous and/or semi-crystalline. This complicates direct phase identification and quantification via standard XRD analysis.

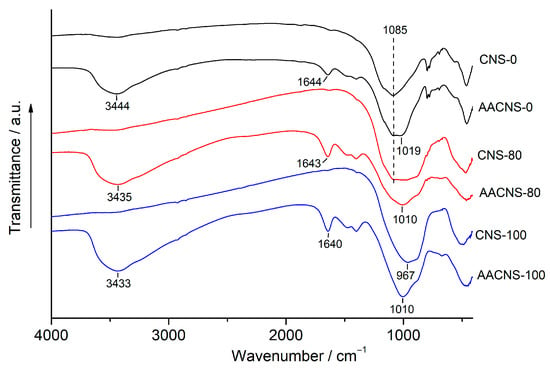

Figure 6 presents the FTIR spectra of the precursors and their corresponding AAMs (AACNS-0, AACNS-80, and AACNS-100) after 28 days of curing. The presence of O–H stretching (3600–3300 cm−1) and H–O–H bending (1650–1630 cm−1) bands in the spectra of all AAMs indicates the formation of an aluminosilicate hydrogel [33]. Furthermore, a broad band in the 1500–1350 cm−1 region suggests atmospheric carbonation of the unreacted alkaline activator, leading to the formation of minor sodium carbonates and hydrocarbonates [33,34]. The IR peaks in the 800–600 cm−1 region in the spectra of CNS-0 and AACNS-0 are attributed to the presence of quartz and mullite in the FA [35,36].

Figure 6.

FTIR spectra of the AACNS-0, AACNS-80, and AACNS-100 cured for 28 days and their precursors, CNS-0, CNS-80, and CNS-100.

The most significant spectral changes, compared to the precursors, occur in the 1200–800 cm−1 region, which corresponds to asymmetric Si–O–T (T = Si or Al) stretching vibrations. For the AACNS-0 sample, the precursor peak at 1085 cm−1 becomes narrower and shifts to a lower wavenumber (1019 cm−1). This shift signifies the formation of an amorphous sodium aluminosilicate hydrate (N-A-S-H) gel, resulting from the substitution of Si by Al in the SiO4 tetrahedra and a depolymerization of the FA’s aluminosilicate framework [33,35,36].

In contrast, the AAM based solely on slag (AACNS-100) exhibits the opposite trend. The main Si–O–T band shifts to a higher wavenumber (1010 cm−1) compared to its precursor CNS-100 (967 cm−1). This shift indicates the oxidation of Fe2+ in the slag to Fe3+ in the binder and a higher degree of polymerization within the silicate network [8,37].

Literature confirms that both magnesium and iron dissolved during the alkali dissolution of NFMS are incorporated into the forming binding gel [8,9,13,14]. Since CNS contains significant amounts of Mg and Fe, the gel formed from CNS-100 is likely a sodium–magnesium–iron–alumino–silicate hydrate (N-M-F-A-S-H) gel or a mixture of N-M-A-S-H and N-F-A-S-H gels.

For the mixed precursor (CNS-80), the changes upon activation are less pronounced. The spectrum of AACNS-80 shows a narrowing of the Si–O–T peak but no significant shift from its position in the CNS-80 precursor. However, the gel formed from this binary precursor (CNS-80) is presumably more complex than those from the corresponding end-members (CNS-0 and CNS-100).

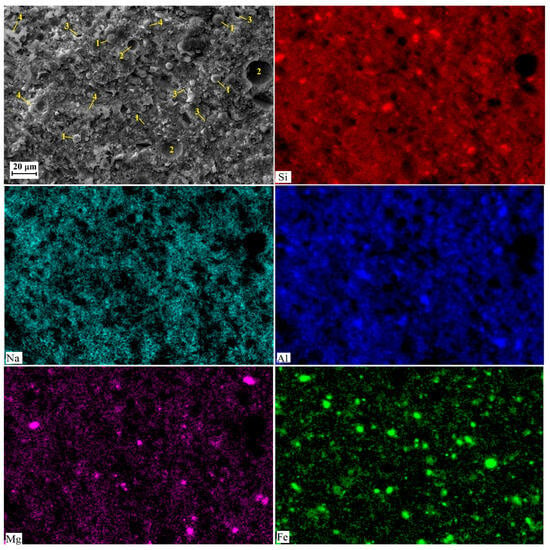

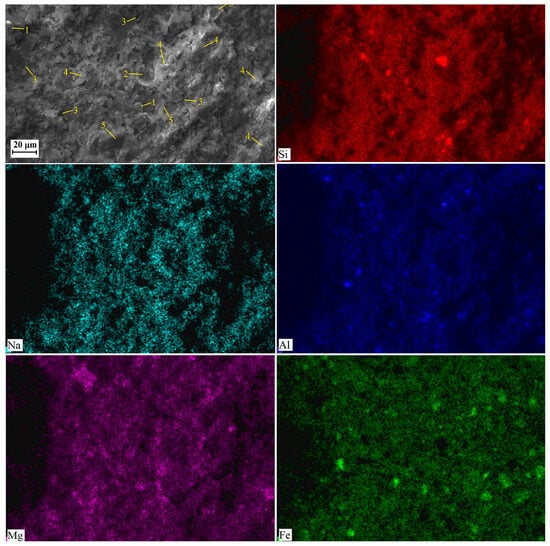

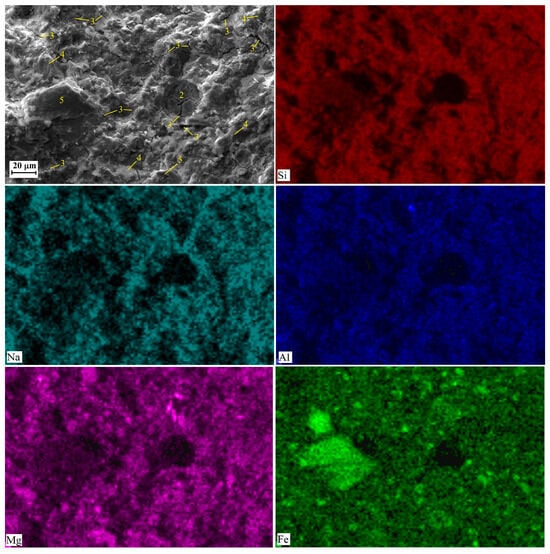

3.3. SEM-EDS Studies

SEM images of the AACNS-0, AACNS-80, and AACNS-100 fracture surfaces after 28 days of curing are displayed in Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9, respectively. The AACNS-80 based on mixed precursor (Figure 8) exhibits a denser, more homogeneous microstructure compared to the AACNS-0 (Figure 7) and AACNS-100 (Figure 9), aligning with the strength data in Figure 3.

Figure 7.

SEM images and element distribution maps obtained for AACNS-0 cured for 28 days. Designations: 1—unreacted or partially reacted FA particles; 2—cavities due to air entrapped into the paste; 3—cracks and voids, 4—gel.

Figure 8.

SEM images and element distribution maps obtained for AACNS-80 cured for 28 days. Designations: 1—unreacted or partially reacted FA particles; 2—cavities due to air entrapped into the paste; 3—cracks and voids, 4—gel; 5—unreacted or partially reacted slag particles.

Figure 9.

SEM images and element distribution maps obtained for AACNS-100 cured for 28 days. Designations: 2—cavities due to air entrapped into the paste; 3—cracks and voids, 4—gel; 5—unreacted or partially reacted slag particles.

The AACNS-80 is characterized by reduced porosity (Figure 8) relative to the AACNS-0 and AACNS-100, attributed to increased reactivity and greater gel formation. This gel fills pores and binds unreacted FA and CNS particles, creating a more compact structure. These findings are supported by TG analysis, which indicates enhanced gel-associated water loss (Figure 4).

The observed difference in the amount and extent of cracks, as visible in the SEM images (Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9), follows a clear order: AACNS-100 > AACNS-0 >> AACNS-80. We note that the specimens for SEM analysis were taken after mechanical testing; therefore, the observed cracking is primarily a result of the specimens’ destruction under load. We propose that this order is rooted in microstructure and gel chemistry. The synergistic AACNS-80 formulation likely promotes the formation of a more chemically complex and cohesive gel phase compared to the end-member mixes (AACNS-0 and AACNS-100). This resultant gel structure is intrinsically more robust, creating a denser matrix that better resists crack initiation and propagation under load, thereby explaining both the superior strength and the reduced cracking.

Elemental mapping reveals a more uniform distribution of Mg and Fe in the AACNS-80 compared to AACNS-0 and AACNS-100. Indirectly, this suggests that Mg and Fe are incorporated into the gel resulting in the formation of N-M-F-A-S-H gel.

4. Discussion

The synergistic effect, where the AAM based on the binary blend of 80% CNS and 20% FA (AACNS-80) yields the highest compressive strength, is a consequence of the optimal interplay of physical and chemical factors at this specific composition.

The physical contribution stems from optimized particle distribution and the role of unreacted particles in the pastes. As the CNS content increases from 0% to 100%, the specific surface area of the solid mixture decreases substantially from 5.47 to 1.06 m2/g (Table 2). This directly reduces the water demand, lowering the water-to-solid ratio (w/s) from 0.30 for AACNS-0 to 0.22 for AACNS-80 and AACNS-100 (Table 2), which inherently promotes a denser matrix. Furthermore, the SEM results (Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9) confirm that a portion of both FA and CNS particles remains unreacted, acting as micro-fillers within the binder gel [38,39]. The combination of fine FA particles and larger CNS particles appears to create an optimal particle size distribution in AACNS-80 that enhances mechanical strength.

The chemical factor is more complex and is central to the observed synergy. The continuous increase in strength up to the AACNS-80 mixture, despite the decreasing specific surface area of the precursors (Table 2), indicates a significant enhancement in chemical reactivity and gel formation. This is clearly supported by the analytical data.

The extent of the reaction between the precursors and alkaline agent is directly evidenced by TG analysis, which revealed the greatest mass loss below 600 °C for the AACNS-80 (Figure 4). This mass loss, attributed to the dehydration and dehydroxylation of the binding gel, implies a greater gel quantity formed in this synergistic mixture than in the AACNS-0 and AACNS-100 samples. Consequently, this abundant gel more effectively fills pores and binds unreacted FA and CNS particles, leading to the notably denser and more homogeneous microstructure observed in AACNS-80 (Figure 8) compared to the single-precursor systems (Figure 7 and Figure 9). This microstructural refinement directly correlates with its superior compressive strength (Figure 3).

The nature of the formed gel is elucidated by FTIR and XRD. The XRD patterns (Figure 3) confirm the amorphous nature of the reaction products in all AAMs. The FTIR spectra (Figure 6) reveal differences in gel structure. The AACNS-0 (100% FA) spectrum indicates the formation of the N-A-S-H gel, evidenced by a peak shift to a lower wavenumber, signifying the substitution of Si by Al in the silicon-oxygen tetrahedra and depolymerization. In contrast, the AACNS-100 (100% CNS) spectrum shows a shift to a higher wavenumber, indicating a more polymerized silicate network and the oxidation of Fe2+ in the slag to Fe3+ in the binder.

The AACNS-80 blend appears to harness the advantages of both precursors. FA provides the crucial soluble silicon and aluminum, the principal network-forming elements. CNS, with its higher glass content and richness in magnesium and iron, contributes to a more complex gel chemistry.

The elemental mapping from SEM-EDS reveals a more uniform distribution of Mg and Fe in AACNS-80, suggesting these elements are incorporated into the gel matrix. The simultaneous dissolution from both precursors at the 80/20 ratio likely provides an optimal stoichiometry, promoting the formation of a gel that is more robust and continuous than the simpler gels formed from the individual precursors. This gel structure likely better resists the initiation and propagation of cracks under load, explaining both its superior strength and reduced crack development.

While this study indicates the incorporation of Mg and Fe into the gel phase, identifying the precise coordination and role of these elements within the gel structure requires further investigation using such techniques as Mössbauer spectroscopy, XANES spectroscopy, and TEM/EDS [40,41,42].

5. Conclusions

This study successfully demonstrates the valorization of copper–nickel slag (CNS) in combination with fly ash (FA) to produce high-strength alkali-activated binders. The key finding is a pronounced synergistic effect, where the binary blend of 80% CNS and 20% FA (AACNS-80) yielded a superior compressive strength of 99.9 MPa (curing for 28 days), significantly exceeding the performance of binders made from 100% FA or 100% CNS.

This enhancement is attributed to a combination of physical and chemical factors. Physically, the blend creates an optimal particle size distribution, reducing water demand and leading to a denser matrix. Chemically, the co-dissolution of the precursors at this specific ratio fosters a more extensive gel formation, as confirmed by thermogravimetric analysis. Microstructural analysis (SEM) revealed a denser, more homogeneous morphology in the AACNS-80 sample, with reduced porosity. A necessary next step is a full quantitative pore size distribution analysis using techniques such as mercury intrusion porosimetry or nitrogen adsorption. This analysis is essential to establish direct, quantitative correlations between the pore structure (e.g., total porosity, pore connectivity, and critical pore diameter) of the AACNS-0, AACNS-80, and AACNS-100 samples and their observed mechanical performance.

Spectroscopic (FTIR) and elemental (SEM-EDS) data indicate that the gel formed in the synergistic blend is more complex than the gel from FA or from CNS. The uniform distribution of Mg and Fe in AACNS-80 suggests their effective incorporation into a gel structure, which likely contributes to a more robust binding phase. While this study indicates the incorporation of these elements, further investigation using advanced techniques such as Mössbauer spectroscopy, XANES spectroscopy, and TEM/EDS, as well as quantitative FTIR analysis, is required to precisely determine their coordination and role within the gel nanostructure.

Overall, this research confirms the technical feasibility of utilizing CNS-FA blends for developing high-performance, sustainable construction materials. Particularly, the optimized blend (AACNS-80) could be beneficial for precast elements and repair mortars, where controlled mixing is feasible.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.K. and E.V.K.; methodology, A.M.K., E.V.K., A.G.I. and E.A.K.; investigation, A.M.K., E.V.K., A.G.I. and E.A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.K.; writing—review and editing, A.M.K., E.V.K., A.G.I. and E.A.K.; visualization, A.G.I. and E.A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

K.A. Yakovlev is acknowledged for his help in the SEM/EDS studies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OPC | Ordinary Portland Cement |

| AAM | Alkali-activated material |

| FA | Fly ash |

| NFMS | Non-ferrous metallurgy slag |

| CNS | Copper–nickel slag |

| AACNS | Alkali-activated copper–nickel slag |

| N-A-S-H gel | Sodium aluminosilicate hydrogel |

References

- Kumar, A.; Kumar, P.; Gogineni, A.; Ahmed, M.; Chen, W. Evolution of Cementitious Binders: Overview of History, Environmental Impacts, and Emerging Low-Carbon Alternatives. Buildings 2025, 15, 3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Shi, J.; He, Z.; Yalçınkaya, Ç.; Revilla-Cuesta, V.; Gencel, O. Review of the Materials Composition and Performance Evolution of Green Alkali-Activated Cementitious Materials. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2023, 25, 1439–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provis, J.L. Alkali-activated materials. Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 114, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidovits, J. Geopolymer Chemistry and Applications, 5th ed.; Institut Géopolymère: Saint-Quentin, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kriven, W.M.; Leonelli, C.; Provis, J.L.; Boccaccini, A.R.; Attwell, C.; Ducman, V.S.; Ferone, C.; Rossignol, S.; Luukkonen, T.; van Deventer, J.S.J.; et al. Why geopolymers and alkali-activated materials are key components of a sustainable world: A perspective contribution. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 107, 5159–5177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Yao, J.; Fu, R. Characteristic, resource approaches and safety utilization assessment of non-ferrous metal smelting slags: A literature review. J. Cent. South Univ. 2024, 31, 1178–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Singh, S.P. Geopolymerization of solid waste of non-ferrous metallurgy—A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 251, 109571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Sande, J.; Peys, A.; Hertel, T.; Rahier, H.; Pontikes, Y. Upcycling of non-ferrous metallurgy slags: Identifying the most reactive slag for inorganic polymer construction materials. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 154, 104627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponomar, V.; Yliniemi, J.; Adesanya, E.; Ohenoja, K.; Illikainen, M. An overview of the utilisation of Fe-rich residues in alkali-activated binders: Mechanical properties and state of iron. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 330, 129900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Casero, M.A.; Bueno-Rodríguez, S.; Castro, E.; Eliche Quesada, D. Alkaline activated cements obtained from ferrous and non-ferrous slags. Electric arc furnace slag, ladle furnace slag, copper slag and silico-manganese slag. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2024, 147, 105427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onisei, S.; Pontikes, Y.; Van Gerven, T.; Angelopoulos, G.N.; Velea, T.; Predica, V.; Moldovan, P. Synthesis of inorganic polymers using fly ash and primary lead slag. J. Hazard Mater. 2012, 205–206, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, T.; Li, L.; Zhu, H.; Wang, H. Conversion of Local Industrial Wastes into Greener Cement Through Geopolymer Technology: A Case Study of High-Magnesium Nickel Slag. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Yao, X.; Zhang, Z. Geopolymer prepared with high-magnesium nickel slag: Characterization of properties and microstructure. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 59, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuri, J.C.; Khan, N.N.; Sarker, P.K. Workability, strength and microstructural properties of ground ferronickel slag blended fly ash geopolymer mortar. J. Sustain. Cem. Based Mater. 2022, 11, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinkin, A.; Kumar, S.; Gurevich, B.; Alex, T.; Kalinkina, E.; Tyukavkina, V.; Kalinnikov, V.; Kumar, R. Geopolymerization behavior of Cu–Ni slag mechanically activated in air and in CO2 atmosphere. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2012, 112, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Jin, H.; Guo, L.; Li, W.; Han, J.; Pan, A.; Zhang, D. Mechanism of Alkali-Activated Copper-Nickel Slag Material. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 2020, 7615848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhi, S.; Li, T.; Zhou, Z.; Li, M.; Han, J.; Li, W.; Zhang, D.; Guo, L.; Wu, Z. Alkali Activation of Copper and Nickel Slag Composite Cementitious Materials. Materials 2020, 13, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, T.; Guo, L.; Zhi, S.; Han, J. Effect of Sodium Silicate on the Hydration of Alkali-Activated Copper-Nickel Slag Materials. Metals 2023, 13, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchadjie, L.N.; Ekolu, S.O. Enhancing the reactivity of aluminosilicate materials toward geopolymer synthesis. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 4709–4733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alex, T.; Kalinkin, A.; Nath, S.; Gurevich, B.; Kalinkina, E.; Tyukavkina, V.; Kumar, S. Utilization of zinc slag through geopolymerization: Influence of milling atmosphere. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2013, 123, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucsi, G. Mechanical activation of power station fly ash by grinding: A review. J. Silic. Based Compos. Mater. 2016, 68, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Kumar, S.; Alex, T.C.; Singla, R. Mapping of calorimetric response for the geopolymerisation of mechanically activated fly ash. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2019, 136, 1117–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldyrev, V.V. Mechanochemistry and mechanical activation of solids. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2006, 75, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamonti, L.; Potenza, M.; Michelini, E.; Ferretti, D.; Borsacchi, S.; Calucci, L.; Lazzarini, L.; Lottici, P.P.; Talento, F.; Graiff, C. One-part geopolymer-like binders with calcium-based solid alkaline activators and metakaolin. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2025, 45, e01528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzeadani, M.; Bompa, D.V.; Elghazouli, A.Y. One part alkali activated materials: A state-of-the-art review. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 57, 104871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.; Vilarinho, I.S.; Capela, M.; Caetano, A.; Novais, R.M.; Labrincha, J.A.; Seabra, M.P. Waste-Based One-Part Alkali Activated Materials. Mater. 2021, 14, 2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Sun, H.; Li, Q.; Li, Z.; Ling, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Xing, F. Experimental comparisons between one-part and normal (two-part) alkali-activated slag binders. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 309, 125177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinkin, A.M.; Gurevich, B.I.; Pakhomovskii, Y.A.; Kalinkina, E.V.; Tyukavkina, V.V. Effect of mechanical activation of magnesia-ferriferous slags in CO2 on their properties. Russ. J. Appl. Chem. 2009, 82, 1346–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinkin, A.M.; Gurevich, B.I.; Myshenkov, M.S.; Chislov, M.V.; Kalinkina, E.V.; Zvereva, I.A.; Cherkezova-Zheleva, Z.; Paneva, D.; Petkova, V. Synthesis of fly ash-based geopolymers: Effect of calcite addition and mechanical activation. Miner. 2020, 10, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxson, P.; Lukey, G.C.; van Deventer, J.S.J. Physical evolution of Na-geopolymer derived from metakaolin up to 1000 °C. J. Mater. Sci. 2007, 42, 3044–3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, E.D.; Bernal, S.A.; Provis, J.L.; Paya, J.; Monzo, J.M.; Borrachero, M.V. Effect of nanosilica-based activators on the performance of an alkali-activated fly ash binder. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2013, 35, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, S.A.; Provis, J.L.; Walkley, B.; San Nicolas, R.; Gehman, J.D.; Brice, D.G.; Kilcullen, A.R.; Duxson, P.; van Deventer, J.S.J. Gel nanostructure in alkali-activated binders based on slag and fly ash, and effects of accelerated carbonation. Cem. Concr. Res. 2013, 53, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozek, P.; Krol, M.; Mozgawa, W. Spectroscopic studies of fly ash-based geopolymers. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2018, 198, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Criado, M.; Palomo, A.; Fernandez-Jimenez, A. Alkali activation of fly ashes. Part 1. Effect of curing conditions on the carbonation of the reaction products. Fuel 2005, 84, 2048–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.K.W.; Deventer, J.S.J.V. Use of infrared spectroscopy to study geopolymerization of heterogeneous amorphous aluminosilicates. Langmuir 2003, 19, 8726–8734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Jimenez, A.; Palomo, A. Mid-infrared spectroscopic studies of alkali activated fly ash structure. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2005, 86, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecomte, I.; Henrist, C.; Liégeois, M.; Maseri, F.; Rulmont, A.; Cloots, R. (Micro)-structural comparison between geopolymers, alkali-activated slag cement and Portland cement. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2006, 26, 3789–3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucsi, G.; Kumar, S.; Csőke, B.; Kumar, R.; Molnár, Z.; Rácz, Á.; Debreczeni, Á. Control of geopolymer properties by grinding of land filled fly ash. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2015, 143, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhimova, N. Calcium and/or magnesium carbonate and carbonate-bearing rocks in the development of alkali-activated cements—A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 325, 126742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Mucsi, G.; Kristály, F.; Pekker, P. Mechanical activation of fly ash and its influence on micro and nano-structural behaviour of resulting geopolymers. Adv. Powder Technol. 2017, 28, 805–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Ding, S.; Ning, C.; Shi, C.; Liu, X.; Ren, Q.; Jiang, Z. Manufacturing a low-carbon geopolymer self-sensing composite for intelligent structure. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2025, 8, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Cui, N.; Xian, Y.; Liu, J.; Xing, C.; Xie, N.; Wang, D. Microstructure Evolution Mechanism of Geopolymers with Exposure to High-Temperature Environment. Crystals 2021, 11, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).