Abstract

Lake sediments on the Tibetan Plateau serve as crucial carbon sinks in the regional carbon cycles. In recent decades, climate change has triggered significant hydrological changes in many lakes across this region, potentially impacting their carbon-sink functions. Previous studies have predominantly focused on the dynamics of organic carbon burial, largely overlooking the contribution of inorganic carbon sinks, and particularly lacking systematic investigation into the carbon burial processes in lakes experiencing water level decline. Therefore, this study examines a sediment core from Lake Yamzhog Yumco, a lake in the southern Tibetan Plateau with a gradually declining water level. The mineralogical and geochemical analyses of both lake and catchment sediments show that the inorganic carbon (carbonates are dominated by aragonite) and organic carbon are primarily authigenic origin. Over the past four decades, the inorganic carbon burial rate (ICBR) in Lake Yamzhog Yumco has been primarily controlled by water level fluctuations and is closely related to hydrochemical processes regulated by regional climate change. In contrast, the increase in the organic carbon burial rate (OCBR) has been co-influenced by both water level changes and regional temperature. During this period, the ICBR reached as high as 186 g m−2 yr−1, approximately five times the OCBR. This demonstrates that in lakes in semi-arid regions, the sink potential of inorganic carbon significantly exceeds that of organic carbon, highlighting the necessity of incorporating inorganic carbon burial into carbon-sink assessments. This study provides novel perspectives for a deeper understanding of the driving mechanisms behind carbon burial in Tibetan Plateau lakes and offers a scientific basis for accurately assessing and predicting regional carbon-sink potential.

1. Introduction

Lakes constitute a significant and active carbon reservoir within terrestrial ecosystems. Despite covering only approximately 3.7% of the global land area, they play a critical role in the transport, burial, and mineralization of carbon [1,2,3]. The amount of carbon sequestered in global lake sediments is nearly half that buried in marine sediments, establishing lakes as a substantial natural carbon sink vital for regulating the global carbon cycle and mitigating climate change [1,4,5,6].

The Tibetan Plateau hosts the world’s highest and most numerous plateau lake systems, with a total lake area exceeding 50% of China’s entire lake area. As the “Asian Water Tower” and a sensitive indicator of global climate change, the lake systems in this region not only maintain regional water cycle balance but also exhibit immense carbon-sink potential [7,8,9,10]. In recent years, a warming and wetting climate and intensified human activities have resulted in significant hydrological changes for the plateau’s lake systems [11]. Water level fluctuations directly regulate the lake area, hydrochemical environment, and ecological structure, while rising temperatures influence aquatic primary productivity [12,13]. These factors, combined with human activities, collectively affect the sources, transport, and burial processes of carbon in lakes. Therefore, systematically elucidating the mechanisms of key climatic factors (e.g., water level and temperature) on the lake carbon cycles, against the increasing influence of human activities, is crucial for accurately assessing historical carbon-sink functions and predicting their future potential [14].

Previous studies have extensively investigated the response of the lake carbon cycle to human activities and climate change on the Tibetan Plateau, yet consensus remains elusive. Some studies emphasize the dominant role of climatic factors, suggesting that temperature seasonally regulates organic matter burial [8] and that an overall warm and humid climate promotes increased organic carbon burial on centennial scales [15] and has done so since the Early–Mid Holocene [16]. Water level fluctuations are thought to affect the organic carbon burial rate by altering aquatic vegetation coverage and terrigenous input fluxes [2]. In contrast, other studies point out that human activities have significantly intervened in the lake carbon cycle over recent decades and even on millennial scales. For instance, nitrogen deposition has driven the increase in sedimentary organic carbon burial over the past century [17], and led to higher organic carbon burial rates during the Late Holocene [16]. Overall, human activities are now recognized as a growing driver within the climate-controlled carbon cycle of lakes.

However, the current research exhibits two notable shortcomings. First, systematic and quantitative exploration of the relationships between key parameters like water level change and carbon burial fluxes remains insufficient. Second, long-term emphasis has been disproportionately placed on organic carbon, severely neglecting the assessment of inorganic carbon burial processes. Recent preliminary studies on lakes such as Lake Qinghai [18], Lake Daihai [19], and Lake Bosten [20] indicate that the burial capacities of inorganic carbon and organic carbon in their sediments are comparable. Recently, estimates further reveal that the global inorganic carbon burial (111 Pg) is approximately twice that of organic carbon (63 Pg) in saline lakes over the past 20,000 years [21]. These findings demonstrate the significant contribution of inorganic carbon to the total carbon sink in saline lakes [22], and overlooking its role would lead to a severe underestimation of the overall carbon-sink potential of lakes [18].

One of the numerous lakes on the Tibetan Plateau, Lake Yamzhog Yumco has experienced a warming of approximately 0.9 °C in recent decades, while the lake level has shown a fluctuating decline, representing a typical water level response pattern in the southern Tibetan Plateau [23]. Furthermore, human activities since 2011 have induced significant changes in this lake’s ecosystem [24]. Consequently, Lake Yamzhog Yumco provides an ideal case for disentangling the response mechanisms of the lake carbon cycle to multiple driving factors, including warming, human activities, and water level changes. Based on this, utilizing a sediment core from Lake Yamzhog Yumco spanning from 1990 onwards, we systematically analyze the compositions of organic and inorganic carbon. Combined with hydrological, meteorological, and hydrochemical data, we focus on investigating the response mechanism of the sediment inorganic carbon sink to warming, human activities, and water level changes. The specific research objectives include (1) identifying the sources of organic and inorganic carbon in the sediments; (2) reconstructing the burial rates of organic and inorganic carbon since 1990 and exploring their control mechanisms; and (3) revealing the contribution of inorganic carbon to the total carbon burial in the lake sediments. This study aims to provide a new case for carbon cycle research in plateau lakes and offer a scientific basis for a more comprehensive assessment of the response of carbon-sink functions to climate change in high-altitude cold regions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

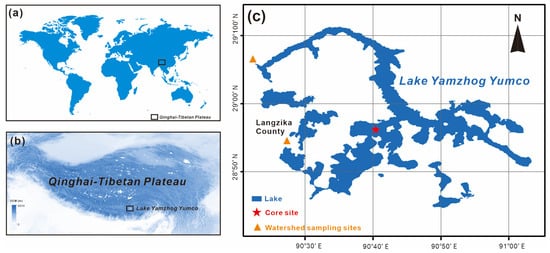

Lake Yamzhog Yumco is situated on the northern flank of the Himalayas, with a lake surface elevation of approximately 4440 m above sea level (asl) (Figure 1a). It is the largest closed-basin, slightly saline inland lake in the southern Tibetan Plateau. The catchment area is about 9064 km2, with a lake area of approximately 600 km2 and a maximum water depth of 59 m [25]. The lake exhibits a dendritic morphology with a highly irregular shoreline stretching about 410 km in total length. Lake water is primarily recharged by rainfall, glacial meltwater, groundwater, and minor snowmelt. Precipitation (approx. 370 mm/a) displays a distinct seasonal concentration, with 88.4% occurring from June to September [26]. The predominant vegetation types within the catchment include alpine steppe and alpine meadow, with sporadic trees and shrubs [27]. The inorganic carbon content in the catchment soils is generally low [28].

Figure 1.

(a) World map, (b) Geographical location of Lake Yamzhog Yumco, (c) Lake morphology and distribution of sampling sites. The red star indicates the sediment core site, and the orange triangles indicate the catchment sampling sites.

2.2. Sample Collection

In August 2020, an undisturbed sediment core (YZYC2, 23 cm in total length) was retrieved from the central part of Lake Yamzhog Yumco (28°56′2.6″ N, 90°40′34.4″ E) at a water depth of approximately 30 m (Figure 1) using a Kajak gravity corer (Ø88, 9 mm, KC Denmark, Galten, Denmark). This location is distal from direct fluvial inputs (Figure 1c) and direct human activities, making it representative for studying lake-wide temporal evolution of carbon burial. The core was sectioned at 1 cm intervals in the field, yielding 23 sub-samples, which were sealed and transported to the laboratory. Samples were freeze-dried and stored at room temperature for subsequent analysis. Additionally, to aid in identifying the sources of inorganic carbon in the lake sediments, river sediment samples were collected by using a grab bucket from two locations within the catchment (Figure 1).

A previous study established the chronological framework for this core using 210Pb and 226Ra radionuclide dating [29]. This age framework is further validated by the close alignment between the water level change reconstructed by carbonate oxygen isotope derived from the YZYC-2 core and the instrumental record of water-level changes, confirming that the core spans the period from 1989 onward [29]. Over the past 40 years, influenced by both climate change and human activities, Lake Yamzhog Yumco has exhibited a general trend of fluctuating water level decline [30]. Consequently, this lake was selected as a typical case study for investigating the impact of water level changes on the carbon-sink system of plateau lakes. Water samples were also collected, filtered, and used for determining major ion concentrations.

2.3. In Situ Measurements

In situ measurements in 2020 using a YSI water quality sonde (YSI EXO2, Yellow Springs, OH, America) recorded a lake water salinity of 1.25 g/L and a pH of 9.02. A surface water sample (approximately 500 mL) was collected at the sediment coring site. For the determination of dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC), a 10 mL aliquot of this water was extracted and analyzed using titration in situ. Field titration using an alkalinity kit (MColortest, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) indicated CO32− and HCO3− concentrations of 2.5 mmol/L and 7.2 mmol/L, respectively. All in situ measurements were conducted at the core site before the collection of core samples.

2.4. Laboratory Analysis and Data Processing

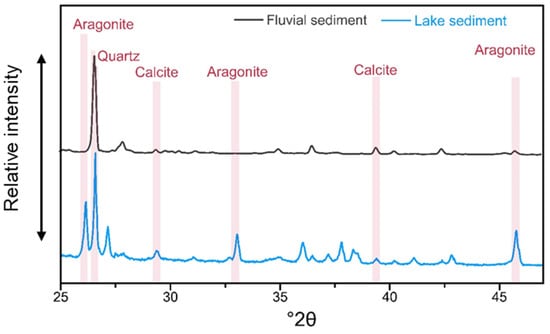

Analysis of filtered water samples via ICP-AES (Leeman Labs, Profile DV, Hudson, NH, USA, with a precision of detection better than 2%) determined the Ca2+ and Mg2+ concentrations to be 6.1 ppm and 27.6 ppm, respectively. Freeze-dried sediment samples were analyzed for total inorganic carbon (TIC) content, carbonate mineral ratios, and elemental composition. The total carbonate content was determined using a GMY-3A automatic carbonate analyzer (Shunyou, Changzhou, China), which measures the pressure of CO2 released from the reaction between the sample and 1 mol/L HCl in a sealed vessel, calculating the content based on a standard curve. Quality control was ensured by including standard samples of known content in each batch analysis. Given that the carbonate minerals in the sediments consisted solely of aragonite and calcite (both chemical formulas are CaCO3), the inorganic carbon content was calculated as 12% of the total carbonate content. Mineral phase identification was performed on lake sediments and catchment river sediments using a Panalytical multi-purpose X-ray powder diffractometer (XRD, XPertPro, Malvern Panalytical Ltd., Amsterdam, The Netherlands, Cu-Kα radiation). Diffraction data were processed using JADE 6.5 software to identify characteristic diffraction peaks for calcite (3.03 Å) and aragonite (1.97 Å). Their characteristic peak intensities are denoted as I~C~ and I~A~, with weighting factors of 1.65 (RC) and 9.3 (RA), respectively [31](Figure 2). The deviation of this method was estimated to be about <5% of the relative abundance of individual carbonates. The specific contents of aragonite and calcite were calculated by combining the total carbonate content from the automatic analyzer with the mineral proportions determined by XRD.

Figure 2.

XRD patterns of a typical catchment sample and lake sediment in Lake Yamzhog Yumco Basin. Vertical bands indicate the characteristic peaks of minerals. All vertical color bands indicate the characteristic peaks of carbonate minerals.

Total organic carbon (TOC) and total nitrogen (TN) contents were measured using an EA 3000 elemental analyzer (EuroVector S.p.A., Novara, Italy). Before analysis, samples were treated with 5% dilute HCl to remove inorganic carbon, followed by centrifugation, freeze-drying, and homogenization by grinding before being encapsulated in tin capsules for measurement. Related work has previously been published [24]. To investigate hydrodynamic conditions from catchment and lake hydrological processes, the concentrations of elements, which can reflect hydrodynamic conditions (Ti, Al, and Fe) and hydrochemical composition (Sr, Ca), were determined via ICP-AES (Leeman Labs, Profile DV, Mason, OH, USA, the precision of detection was better than 2%). Approximately 0.5 g of ground sample was subjected to microwave digestion with HCl-HNO3-HF, evaporated to dryness, treated with HClO4 and H2O2, and finally diluted to 25 mL for analysis. Replicates were included for every 10 samples, and the measurement error for elements was controlled within 5%. Finally, sediment redness was determined by spectrophotometry. One gram of the original sample was ground into a slurry, formed into a thin layer, and dried at a low temperature. Reflectance spectra from 400–700 nm was scanned at 2 nm intervals using a Perkin-Elmer Lambda 900 spectrophotometer (Springfield, IL, USA) to calculate redness. Approximately 1 g of the freeze-dried sediment was finely ground into a homogeneous powder using an agate mortar to ensure a uniform particle size and minimize scattering effects. The powder was then evenly pressed into a flat, smooth-surfaced pellet using a hydraulic press to create a consistent and optically flat surface for reflectance measurement. Redness was defined as the sum of reflectance in the 630–700 nm band relative to the total reflectance in the 400–700 nm band [32].

The carbon burial rate (CBR) in the lake was calculated based on the sediment carbon content (C), sedimentation rate (SR), and dry bulk density (DBD) using the following equations [33,34,35]:

where Md represents the mass of the dry sample, and V represents the volume of the wet sample.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Sources of Carbon in Lake Yamzhog Yumco Sediments

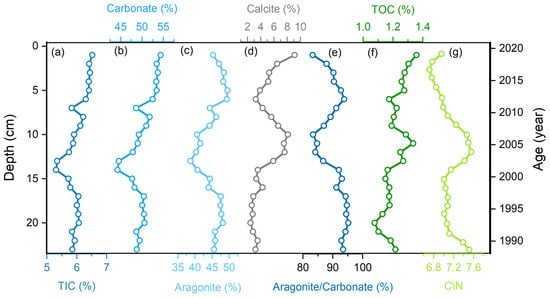

Identifying the sources of inorganic and organic carbon in the sediments of Lake Yamzhog Yumco is a prerequisite for reconstructing carbon burial history and elucidating the underlying mechanisms. We first determined the source of inorganic carbon based on mineralogical analysis. XRD results show that the carbonate minerals in the lake sediments were dominated by aragonite (45.1% ± 3.8%) and calcite (4.8% ± 2.0%) (Figure 3). Whereas only trace amounts of calcite, slightly above the XRD detection limit, were detected in the catchment river sediments (Figure 2). This discrepancy is closely related to the formation conditions of aragonite and calcite: aragonite is a metastable polymorph of calcium carbonate that readily transforms into the thermodynamically more stable calcite during burial diagenesis [36]. As a result, it is scarce in terrigenous detrital material [37] that has undergone prolonged burial and occurs predominantly in modern or shallowly buried authigenic sedimentary environments. This explains the absence of aragonite in catchment topsoils and river sediments. In contrast, the high Mg/Ca ratio (>2) of the lake water—measured here as 5.3—strongly favors aragonite precipitation [38,39], indicating that the aragonite found in Lake Yamzhog Yumco sediments is primarily authigenic in origin.

Figure 3.

Proxies of the sediment core in Lake Yamzhog Yumco: (a) Total inorganic carbon (TIC); (b) Carbonate content; (c) Aragonite content; (d) Calcite content; (e) Aragonite/Calcite ratio; (f) Total organic carbon (TOC) content (Data from [24]); (g) Organic matter C/N ratio (Data from [24]).

Calcite, however, has multiple potential sources, forming either within the lake water body or originating from the catchment. Calcite precipitation is primarily driven by supersaturation of Ca2+ and CO32− in the lake water, often promoted by high pH and elevated carbonate alkalinity—conditions that favor inorganic carbonate precipitation [39]. In Lake Yamzhog Yumco, such hydrochemical conditions periodically occur due to evaporative concentration and photosynthetic uptake of CO2, leading to authigenic calcite formation. In addition, bedrock often contains abundant calcite [40], leading to its common presence in lake, soil, and river sediments. Nevertheless, the very low calcite content found in the river sediments of the Lake Yamzhog Yumco catchment (Figure 2) suggests a minimal contribution from catchment-derived carbonates. This finding is supported by regional soil inorganic carbon surveys [28]. Furthermore, the significantly positive carbonate oxygen isotope values, which show a strong negative correlation with water level [29], provide indirect evidence that the lake carbonates are primarily of authigenic origin. In summary, aragonite in Lake Yamzhog Yumco sediments is purely authigenic, and calcite is also predominantly derived from internal processes.

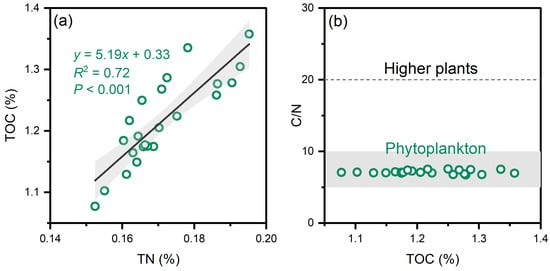

Multiple lines of evidence also indicate that organic carbon is primarily derived from within the lake’s aquatic organisms. The C/N ratio of sedimentary organic matter is a commonly used indicator for discerning its source [41]. Terrestrial vascular plants and submerged aquatic plants typically exhibit high C/N ratios (>20) due to lower nitrogen availability [42,43], whereas phytoplankton, growing in nitrogen-rich environments, generally have lower C/N ratios, often considered to be less than 8 [43,44]. The significant correlation (R2 = 0.72, p < 0.001) between TOC and TN contents in Lake Yamzhog Yumco sediments (Figure 4) indicates that nitrogen is primarily associated with organic matter, validating the use of the C/N ratio as a reliable source indicator of organic carbon. The C/N ratios of these sediments range from 6.7 to 7.6, with a mean of 7.1, suggesting that the organic matter originates mainly from phytoplankton. This interpretation is consistent with sedimentary ancient DNA studies that detected abundant algal sources [24]. Concurrently, the δ13C values of sedimentary organic matter over recent decades range from −25.5‰ to −29.5‰, which are significantly more negative than those typical of terrestrial plants and align more closely with signals from lacustrine algae [45], further supporting a predominantly autochthonous source for the organic carbon. Additionally, surveys indicate sparse vegetation coverage around the Lake Yamzhog Yumco watershed [46], which limits the input and deposition of substantial amounts of terrigenous organic carbon.

Figure 4.

(a) Relationship between TOC and TN in sediment core samples; (b) Plots between C/N ratio and TOC in sediment core samples. TOC and TN (Data from [24]).

In summary, the geochemical and mineralogical evidence demonstrates that both inorganic and organic carbon in Lake Yamzhog Yumco sediments are primarily derived from autochthonous processes within the lake. The TIC, further calculated based on carbonate content, and TOC content, provide a reliable basis for subsequent reconstruction of carbon burial history and investigation of driving mechanisms.

3.2. Carbon Burial History in Lake Yamzhog Yumco over the Recent Decades and Its Driving Mechanisms

Based on the TIC content of the sediments, we reconstructed the carbon burial dynamics in Lake Yamzhog Yumco since 1989. The TIC content in the core ranges from 5.3% to 6.5%, with an average of 6.0 ± 0.3%. This corresponds to an inorganic carbon burial rate (ICBR) ranging from 163.7 to 201.1 g m−2 yr−1 and an average of 184.7 ± 10.4 g m−2 yr−1 (Figure 5). Overall, the ICBR showed a fluctuating upward trend, with the lowest values occurring from AD 1997 to 1998.

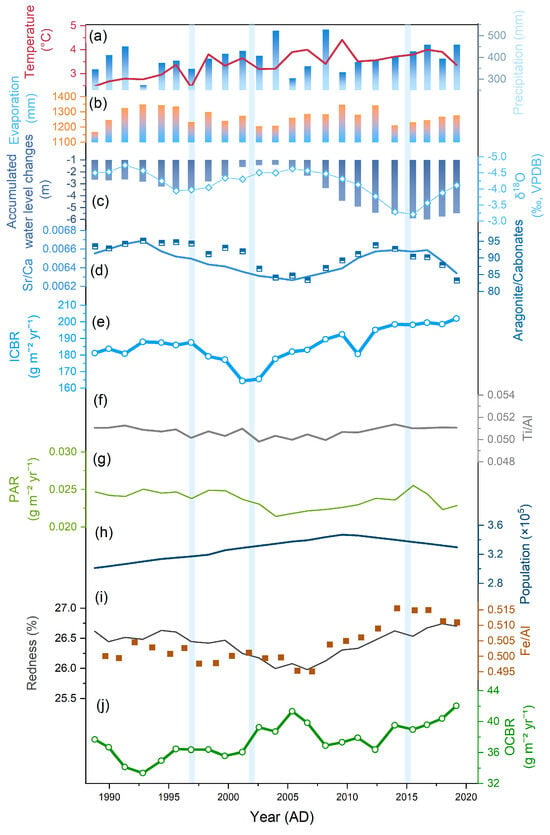

Figure 5.

(a) Temperature and precipitation monitor data at the Lake Yamzhog Yumco basin over the past ~30 years (Data from [24]); (b) Interannual evaporation monitored at the Baidi Station (Data from [24]); (c) Cumulative water level change monitored at the Baidi Station and the δ18O values of the Lake Yamzhog Yumco sediment core (Data from [29]); (d) Sr/Ca ratio and Aragonite/Calcite ratio of the sediment core (this study); (e) ICBR of Lake Yamzhog Yumco over the past ~30 years (this study); (f) Ti/Al ratio of the sediment core (this study); (g) Phosphorus accumulation rate (PAR) of the sediment core (Data from [24]); (h) Permanent resident population of Langkazi County (Data from [24]); (i) Redness and Fe/Al ratio of the sediment core (this study); and (j) OCBR of Lake Yamzhog Yumco over the past ~30 years (this study).

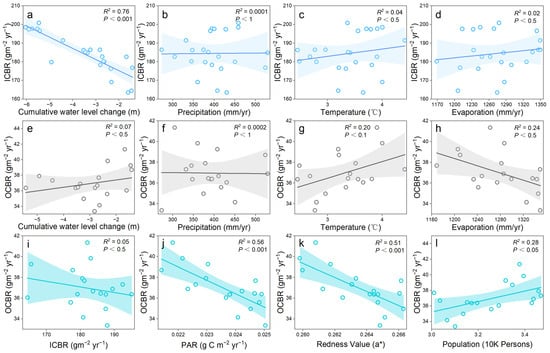

Typically, variations in lake ICBR are controlled by two major processes: (1) the concentrations of Ca2+ and CO32− regulated by evaporation [47,48]; (2) the influx of Ca2+ via runoff [49,50,51]. The measured Ca2+ and CO32− concentrations in Lake Yamzhog Yumco in 2020 were 6.1 ppm and 2.5 mmol/L, respectively, both are relatively low levels. This indicates that carbonate precipitation is co-limited by the availability of both ions, unlike scenarios in some saline lakes where CO32− is abundant [9] but Ca2+ is limiting [52]. Furthermore, the significant negative correlation between ICBR and water level changes (R2 = 0.76, Figure 6) further confirms the critical role of the “evaporative concentration effect” on inorganic carbon burial.

Figure 6.

Relationships between carbon burial rate and other drivers. (a) ICBR and cumulative water level change, (b) ICBR and precipitation, (c) ICBR and temperature, (d) ICBR and evaporation, (e) OCBR and cumulative water level change, (f) OCBR and precipitation, (g) OCBR and temperature, (h) OCBR and evaporation, (i) ICBR and OCBR, (j) PAR and OCBR, (k) Redness and OCBR, and (l) Population and OCBR. Refer to Figure 5 for the corresponding data.

Further analysis revealed that the water level and ICBR in Lake Yamzhog Yumco over the past three decades exhibited synchronous evolution through four distinct phases (Figure 5): (1) From 1989 to 1997, both evaporation and precipitation were high, maintaining a high lake level. High aragonite content contributed to sustained high ICBR values. (2) From 1997 to 2003, influenced by increased regional precipitation and reduced evaporation, the water level rose rapidly. A dilution effect decreased the production of authigenic inorganic carbon, supported by low aragonite content and aragonite/carbonate ratio, leading to a gradual decline in ICBR. (3) From 2003 to 2015, the lake level continued to drop, accompanied by a regional climate shift featuring a mean annual temperature increase of 0.9 °C, a precipitation decrease of 22.6 mm, and an evaporation increase of 15.2 mm. The declining water level created hydrochemical conditions favorable for aragonite formation. Consequently, both the content and proportion of aragonite gradually increased, driving the recovery of ICBR. (4) From 2015 to the present, although the water level showed a slight recovery, it remained relatively low overall, sustaining high aragonite content and resulting in high ICBR values. These water level changes not only regulated lake hydrochemistry but are also recorded in the isotopic, elemental, and mineralogical composition of the sediments. For instance, the Sr/Ca ratio in the sediments, serving as an indicator of lake water salinity [53], exhibited a four-phase fluctuation pattern since 1990, highly consistent with water level changes, reflecting the rapid response of hydrochemical conditions to hydrological variations. Collectively, this evidence indicates that water level change, integrating climatic information, has been the primary controlling factor for inorganic carbon burial dynamics in Lake Yamzhog Yumco over the recent decades.

In addition to ICBR, we reconstructed the history of the organic carbon burial rate (OCBR) and discussed its driving factors. Since 1989, the OCBR in Lake Yamzhog Yumco has ranged from 33.4 to 42.1 g m−2 yr−1, with a mean of 37.7 ± 2.2 g m−2 yr−1 (Figure 5). Its temporal variation can be broadly divided into four phases: a decrease from 1989–1993, followed by a gradual recovery peaking around 2005, a slight decline post-2005, and a increase again after 2015. It is important to note that post-depositional mineralization of organic carbon might lead to an overestimation of OCBR [54]. The relatively large water depth (max. 59 m) in Lake Yamzhog Yumco creates a hypolimnetic anoxic environment that suppresses organic matter mineralization [55,56,57,58]. The low C/N ratios (< 7.6) and their positive correlation with TOC further support limited mineralization, as mineralization tends to increase the C/N ratio and decrease TOC content [59]. Additionally, we used the redness of sediment to assess the impact of redox conditions [60] on OCBR. The principle is that iron oxides, such as goethite and hematite, control redness [61]. Under reducing conditions, these oxides dissolve, leading to low redness, and vice versa [60,62,63]. Although a negative correlation exists between OCBR and redness (R2 = 0.51, p < 0.001) (Figure 6k), this might be because both are influenced by water level changes (e.g., declining water level enhances sediment reducing conditions to lower redness, while altering lake salinity and productivity to affect OCBR). It is also necessary to consider the potential impact of post-depositional organic carbon mineralization: a previous study has suggested that organic carbon can undergo rapid mineralization of approximately 20% within the first 5 years after deposition, followed by only about 3% further decomposition over the subsequent 22 years [64], which may slightly modify the measured OCBR values. Therefore, the high TOC and OCBR observed since 2015 (Figure 5) might reflect a stage where mineralization is not yet complete. Consequently, we will treat data from this period cautiously and exclude it from the subsequent analysis.

Assuming post-depositional mineralization has a limited effect, the variation in OCBR is primarily controlled by the input of organic matter, which is determined by aquatic primary productivity. In this study, we selected regional fertilizer application and population as indicators of anthropogenic influence. Phosphorus accumulation rate (PAR) in sediment generally reflects nutrient input to the lake [24], with higher values indicating greater nutrient input. The Ti/Al ratio was used to indicate changes in the input of detrital material from the catchment [65]. Below, we discuss the controlling factors for OCBR changes in detail by integrating these factors.

Aquatic biological productivity is the fundamental regulator of OCBR [66]. In Lake Yamzhog Yumco, productivity is jointly influenced by nutrient availability, salinity, and temperature [67,68,69]. Although there has been a slight increase in population, cultivated land, and agricultural activity within the catchment [24], PAR did not show a significant increasing trend. The stable Ti/Al ratio also suggests steady runoff input, which is potentially related to the lack of significant precipitation change limiting the input of nutrient-laden runoff, indicating that nutrient inputs remained limited (Figure 5g). The negative correlation between OCBR and PAR (Figure 6j) further rules out nutrient availability as the dominant factor driving OCBR changes. On the other hand, the mean annual temperature has increased by approximately 0.9 °C over the past three decades. Theoretically, this should enhance productivity by extending the ice-free period and promoting phytoplankton metabolism [70,71], and the overall increasing trend in OCBR is consistent with this expectation (Figure 5). However, the correlation between temperature and OCBR is only weakly positive (Figure 6), and their temporal patterns are misaligned: warming initiated around 1998, but OCBR did not begin to rise until 2002; during 2008–2013, temperatures were relatively high, yet OCBR was relatively low. These observations suggest that while temperature plays a role in the long-term trend, interannual to multi-annual variability is more strongly influenced by changes in water level/salinity. Decreasing lake salinity can enhance the growth of aquatic organisms [69]. Periods of low water level (e.g., 1989–2002) were often associated with higher OCBR, whereas during the high lake level period (2002–2008), OCBR reached its peak despite slower warming. Furthermore, the response of OCBR to changes in water level and temperature exhibits a lag of approximately 4–5 years, similar to observations in lakes on the Yungui Plateau [34], indicating a potential delayed response of organic carbon burial in lake sediments to external environmental drivers (Figure 5).

3.3. Implications of Carbon Burial in Lake Yamzhog Yumco

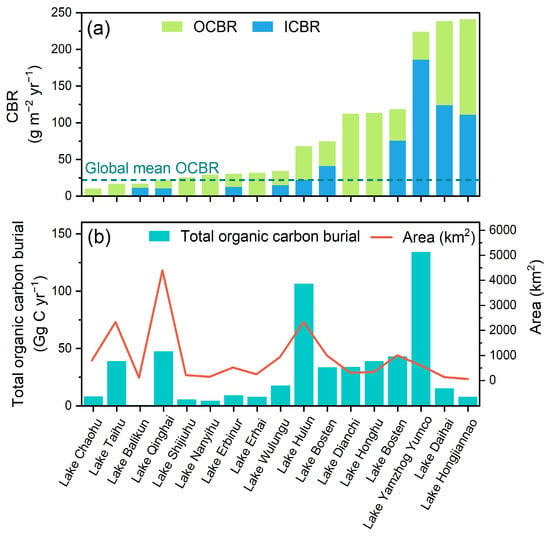

The OCBR in Lake Yamzhog Yumco is 37.7 ± 2.2 g C m−2 yr−1, which is at a medium level globally. Compared to other regions, this value is lower than that of the eutrophic Lake Greifen in Switzerland (50–60 g C m−2 yr−1) [72] and Lake Rostherne Mere (96.10 g C m−2 yr−1) and Lake Tatton Mere (62.51 g C m−2 yr−1) in the UK [73], and also lower than approximately 89% of agriculturally impacted lakes in Minnesota, USA (OCBR > 50 g C m−2 yr−1) [74]. It is slightly lower than the OCBR reported for some lakes with significant human activity in the Eastern Plains Lake Region (e.g., Lake Taihu) [75,76] and the Yungui Plateau Lake Region (e.g., Lake Lugu) [33,34,35]. Overall, it remains significantly lower than most lakes in humid regions, reflecting the constraint on primary productivity imposed by the semi-arid climatic setting.

Notably, the inorganic carbon burial rate (ICBR) in Lake Yamzhog Yumco is as high as 186 g C m−2 yr−1, approximately five times its OCBR. This significantly exceeds the global average lake OCBR (approx. 22 g C m−2 yr−1) and the regional average for the Tibetan Plateau (approx. 14.3 g C m−2 yr−1) [18]. This characteristic is not unique among semi-arid lakes. For example, the ICBR in Lake Bosten is also about twice its OCBR [20], indicating that inorganic carbon constitutes a significant component of the carbon sink in such lakes. The carbon burial rate in Lake Yamzhog Yumco is also higher than that of other semi-arid lakes in China, such as Daihai, Ulungur Lake, Hongjiannao [19,20], and Lake Hulun [77], further highlighting the substantial carbon burial potential, particularly for inorganic carbon, in arid and semi-arid region lakes (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

(a) OCBR and ICBR of different lakes, compared with the global average OCBR; (b) Mean annual total carbon burial and lake area for each lake. The information relating to these lakes has been listed in Table S1 (see Supplementary Materials).

Interestingly, the ICBR and OCBR in Lake Yamzhog Yumco show significant differences and even nearly opposite temporal trends (Figure 5 and Figure 6). Specifically, OCBR decreased from 1989 to 1993, then gradually increased, peaking around 2005, followed by a slight decline. In contrast, ICBR increased slightly after 1989, then decreased rapidly, reaching its lowest value around 2002, before increasing continuously thereafter. This mismatch primarily stems from their differing response mechanisms relative to water level changes. Rising water levels decrease the saturation state of calcium carbonate in the lake water, inhibiting authigenic carbonate precipitation and leading to decreased ICBR. In contrast, lower salinity and a more stable water column environment can promote primary productivity and improve organic matter preservation conditions, thereby driving increased OCBR [69].

It is noteworthy that the OCBR peak around 2005 slightly lagged behind the ICBR trough around 2002. This suggests that the impact of water level change on inorganic carbon burial is more direct and immediate, whereas its regulation of organic carbon burial involves indirect feedback through ecosystem structure and organic matter preservation conditions, resulting in a certain time lag. This phenomenon is similar to the observed lag in organic carbon burial in some lakes on the Yungui Plateau [34], hinting that it might be a common response pattern of the lake carbon cycle to climate-hydrological forcing.

In summary, this study systematically reveals the inorganic carbon-dominated structure of carbon burial in Lake Yamzhog Yumco and clarifies the differential regulatory mechanisms of water level change on the burial processes of the two carbon components. The findings not only deepen the understanding of carbon cycle mechanisms in plateau lakes but also provide key scientific evidence for accurately assessing the carbon-sink function of semi-arid lakes and for constructing comprehensive lake carbon budget models that include inorganic carbon.

4. Conclusions

Based on geochemical and mineralogical indicators from a sediment core, this study identified the sources of carbon in the sediments of Lake Yamzhog Yumco on the Tibetan Plateau over the past three decades and systematically analyzed the driving mechanisms of carbon burial. Integrated mineralogical and geochemical analyses of catchment and lake sediments demonstrate that both inorganic and organic carbon in the lake are predominantly autochthonous. The significant negative correlation between ICBR and lake water level indicates that water level change, driven by the “evaporative concentration process,” has been the primary mechanism controlling lacustrine inorganic carbon burial over approximately the past thirty years. Regional climate change during this period directly influenced the evolution of ICBR by regulating lake hydrochemistry and material inputs. In contrast, increased nutrient inputs within the catchment and rising regional air temperature jointly established the overall increasing trend of OCBR over the past three decades. Water level changes caused fluctuations in the OCBR of Lake Yamzhog Yumco by affecting lake salinity and the preservation conditions of organic matter in the sediments. The ICBR in Lake Yamzhog Yumco over the past thirty years reached 186 g m−2 yr−1, approximately five times the concurrent OCBR, suggesting that the inorganic carbon-sink potential in semi-arid region lakes may exceed that of organic carbon, underscoring the importance of accurate quantification of the inorganic carbon sink. Furthermore, we found that the impact of changing hydrological conditions on OCBR exhibits a lag compared to its effect on ICBR. These findings contribute to a deeper understanding of the driving mechanisms behind carbon burial in Tibetan Plateau lakes and aid in the precise assessment and effective prediction of regional lake carbon burial potential.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/min16010055/s1, Table S1: Lake information.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.M.; methodology, X.M.; software, H.C.; validation, P.P., Y.S. and W.S.; formal analysis, W.H.; investigation, W.H., W.S., R.L., J.C. and S.L.; resources, X.M.; data curation, H.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Z. and X.M.; writing—review and editing, H.C. and X.M.; visualization, H.C. and X.M.; supervision, H.C. and X.M.; project administration, H.C. and X.M.; funding acquisition, X.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 42477486, and the Nanjing Institute of Geography and Limnology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, grant number NIGLAS2022TJ11.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article. or “Data are contained within the article and supplementary materials.”. Data are available through Figshare Data at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30689207.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tranvik, L.J.; Downing, J.A.; Cotner, J.B.; Loiselle, S.A.; Striegl, R.G.; Ballatore, T.J.; Dillon, P.; Finlay, K.; Fortino, K.; Knoll, L.B.; et al. Lakes and reservoirs as regulators of carbon cycling and climate. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2009, 54, 2298–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, J.J.; Prairie, Y.T.; Caraco, N.F.; McDowell, W.H.; Tranvik, L.J.; Striegl, R.G.; Duarte, C.M.; Kortelainen, P.; Downing, J.A.; Middelburg, J.J.; et al. Plumbing the Global Carbon Cycle: Integrating Inland Waters into the Terrestrial Carbon Budget. Ecosystems 2007, 10, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyhenmeyer, G.A.; Kosten, S.; Wallin, M.B.; Tranvik, L.J.; Jeppesen, E.; Roland, F. Significant fraction of CO2 emissions from boreal lakes derived from hydrologic inorganic carbon inputs. Nat. Geosci. 2015, 8, 933–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, R.; Müller, R.A.; Clow, D.; Verpoorter, C.; Raymond, P.; Tranvik, L.J.; Sobek, S. Organic carbon burial in global lakes and reservoirs. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heathcote, A.J.; Anderson, N.J.; Prairie, Y.T.; Engstrom, D.R.; del Giorgio, P.A. Large increases in carbon burial in northern lakes during the Anthropocene. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 10016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, N.J.; Heathcote, A.J.; Engstrom, D.R. Anthropogenic alteration of nutrient supply increases the global freshwater carbon sink. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaaw2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immerzeel, W.W.; Beek, L.P.H.v.; Bierkens, M.F.P. Climate change will affect the Asian water towers. Science 2010, 328, 1382–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Long, H.; Chen, W.; Qiu, C.; Zhang, C.; Xing, H.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, L.; Zhao, C.; Cheng, J.; et al. Temperature seasonality regulates organic carbon burial in lake. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Sun, K.; Lü, S.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Yu, G.; Gao, Y. Determining whether Qinghai–Tibet Plateau waterbodies have acted like carbon sinks or sources over the past 20 years. Sci. Bull. 2022, 67, 2345–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Ju, P.; Zhu, Q.; Xu, X.; Wu, N.; Gao, Y.; Feng, X.; Tian, J.; Niu, S.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Carbon and nitrogen cycling on the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Zhang, G.; Woolway, R.I.; Yang, K.; Wada, Y.; Wang, J.; Crétaux, J.-F. Widespread societal and ecological impacts from projected Tibetan Plateau lake expansion. Nat. Geosci. 2024, 17, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Ju, J.; Qiao, B.; Liu, C.; Wang, J.; Yang, R.; Ma, Q.; Guo, L.; Pang, S. Physical and biogeochemical responses of Tibetan Plateau lakes to climate change. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 284–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Zhang, K.; Lin, Q.; Huang, S.; Han, Y.; Ren, J.; Xing, P.; Liu, J.; Taylor, D.; Shen, J. Rapid ecological change outpaces climate warming in Tibetan glacier lakes. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Shi, K.; Chen, P.; Yan, N.; Ran, L.; Kutser, T.; Tyler, A.N.; Spyrakos, E.; Woolway, R.I.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Substantial increase of organic carbon storage in Chinese lakes. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Chen, X.; Lin, Q.; Liu, Y.; Ni, Z.; Sun, W.; Zhang, E. Spatiotemporal patterns of organic carbon burial over the last century in Lake Qinghai, the largest lake on the Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 860, 160449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, B.; Shi, P.; Duan, K.; Dong, Z. Climate and vegetation codetermine the increased carbon burial rates in Tibetan Plateau lakes during the Holocene. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2023, 310, 108118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Li, X.; Yue, F.-J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, D.; Liu, D.; Li, F.; Wang, X.; Ji, X. Anthropogenic nitrogen inputs favour increased nitrogen and organic carbon levels in Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau lakes: Evidence from sedimentary records. Water Res. 2025, 277, 123330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Meng, X.; Song, Y.; Zhang, B.; Wan, Z.; Zhou, B.; Zhang, E. Spatial Patterns of Organic and Inorganic Carbon in Lake Qinghai Surficial Sediments and Carbon Burial Estimation. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 714936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liu, Q.; Yu, R.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Du, M.; Li, X.; Wang, X. Dominance of inorganic carbon burial in a closed-basin lake under arid climate. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 394, 127324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, J.; Xu, H.; Liu, B.; Sheng, E.; Zhao, J.; Yu, K. A large carbon pool in lake sediments over the arid/semiarid region, NW China. Chin. J. Geochem. 2015, 34, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, M.; Xue, Y. Global lake carbon burial from endorheic zones since the Last Glacial Maximum and the future projection. Innov. Geosci. 2025, 3, 100132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, N.; Han, Q.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Xu, L.; Ye, W. Substantial inorganic carbon sink in closed drainage basins globally. Nat. Geosci. 2017, 10, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Yao, T.; Xie, H.; Yang, K.; Zhu, L.; Shum, C.K.; Bolch, T.; Yi, S.; Allen, S.; Jiang, L.; et al. Response of Tibetan Plateau lakes to climate change: Trends, patterns, and mechanisms. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020, 208, 103269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Zhang, E.; Sun, W.; Lin, Q.; Meng, X.; Ni, Z.; Ning, D.; Shen, J. Anthropogenic activities altering the ecosystem in Lake Yamzhog Yumco, southern Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 904, 166715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Ma, Y.; Meng, H.; Hu, C.; Li, D.; Liu, J.; Luo, C.; Wang, K. Changes in vegetation and environment in Yamzhog Yumco Lake on the southern Tibetan Plateau over past 2000 years. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2018, 501, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Zhang, F.; Zeng, C.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Xiang, Y.; Yu, Z. Simulation of Runoff through Improved Precipitation: The Case of Yamzho Yumco Lake in the Tibetan Plateau. Water 2023, 15, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhe, M.; Zhang, X.; Wang, B.; Sun, R.; Zheng, D. Hydrochemical regime and its mechanism in Yamzhog Yumco Basin, South Tibet. J. Geogr. Sci. 2017, 27, 1111–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.D.; Yang, F.; Wu, H.Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, D.C.; Liu, F.; Zhao, Y.G.; Yang, J.L.; Ju, B.; Cai, C.F.; et al. Significant loss of soil inorganic carbon at the continental scale. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2022, 9, nwab120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Y.; Shen, J.; Sun, W. Environmental significance of stable isotope composition of carbonates from a sediment core at Lake Yamzho Yumco on the southern Tibetan Plateau over the past 30 years (In Chinese with English abstract). Quat. Sci. 2022, 6, 1624–1632. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, H.; Cidan, Y.; Zeng, C.; Zhang, F. Characteristics of the lake water level changes and influencing factors in Yamzhog Yumco in Tibet from 1974 to 2019 (In Chinese with English abstract). J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2021, 35, 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, H.; Johnson, P.; Matti, J.; Zemmels, I. IV. Methods of Sample Preparation, and X-ray Diffraction Data Analysis, X-ray Mineralogy Laboratory, Deep Sea Drilling Project, University of California, Riverside. Initial Rep. Deep Sea Drill. Proj. 1975, 25, 999–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X.; Liu, L.; Miao, X.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, E.; Ji, J. Significant influence of Northern Hemisphere high latitude climate on appeared precession rhythm of East Asian summer monsoon after Mid-Brunhes Transition interglacials recorded in the Chinese loess. Catena 2021, 197, 105002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, E.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, E.; Lin, Q.; Wang, R.; Shen, J. Spatio-temporal patterns of organic carbon burial in the sediment of Lake Erhai in China during the past 100 years. J. Lake Sci. 2019, 31, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Hu, W.; Chen, A.; Li, T.; Zhang, W. Human-caused increases in organic carbon burial in plateau lakes: The response to warming effect. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 937, 173556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Liu, E.; Zhang, E.; Nath, B.; Bindler, R.; Liu, J.; Shen, J. Organic carbon burial in a large, deep alpine lake (southwest China) in response to changes in climate, land use and nutrient supply over the past ~100 years. CATENA 2021, 202, 105240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Zarza, A.M.; Tanner, L.H. Carbonates in continental settings: Geochemistry, diagenesis and applications. In Developments in Sedimentology; Alonso-Zarza, A.M., Tanner, L.H., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 62, pp. 1–320. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-García, R.; Alonso-Zarza, A.M.; Frisia, S.; Rodríguez-Berriguete, Á.; Drysdale, R.; Hellstrom, J. Effect of aragonite to calcite transformation on the geochemistry and dating accuracy of speleothems. An example from Castañar Cave, Spain. Sediment. Geol. 2019, 383, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dor, Y.B.; Flax, T.; Levitan, I.; Enzel, Y.; Brauer, A.; Erel, Y. The paleohydrological implications of aragonite precipitation under contrasting climates in the endorheic Dead Sea and its precursors revealed by experimental investigations. Chem. Geol. 2021, 576, 120261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Zarza, A.M.; Tanner, L.H. Carbonates in Continental Settings: Facies, Environments, and Processes; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 61. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X.; Liu, L.; Zhao, W.; He, T.; Chen, J.; Ji, J. Distant Taklimakan Desert as an important source of aeolian deposits on the Chinese Loess Plateau as evidenced by carbonate minerals. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 4854–4862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, P.A.; Ishiwatari, R. Lacustrine organic geochemistry—An overview of indicators of organic matter sources and diagenesis in lake sediments. Org. Geochem. 1993, 20, 867–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, S.; Binford, M.W. Relationship between C:N ratios of lake sediments, organic matter sources, and historical deforestation in Lake Pleasant, Massachusetts, USA. J. Paleolimnol. 1999, 22, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.; Mathesius, U. The palaeoenvironments of coastal lagoons in the southern Baltic Sea, I. The application of sedimentary Corg/N ratios as source indicators of organic matter. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 1999, 145, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, P.A.; Lallier-vergés, E. Lacustrine Sedimentary Organic Matter Records of Late Quaternary Paleoclimates. J. Paleolimnol. 1999, 21, 345–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, S.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Wu, F. Temperature and precipitation dominates millennium changes of eukaryotic algal communities in Lake Yamzhog Yumco, Southern Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 829, 154636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, L.; Ma, Y.; Xue, Y.; Piao, S. Climate Change Trends and Impacts on Vegetation Greening Over the Tibetan Plateau. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2019, 124, 7540–7552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warrier, A.K.; Shankar, R.; Sandeep, K. Sedimentological and carbonate data evidence for lake level variations during the past 3700 years from a southern Indian lake. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2014, 397, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Zarza, A.M. Palaeoenvironmental significance of palustrine carbonates and calcretes in the geological record. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2003, 60, 261–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; He, S.; Wong, M.L.; Zou, Y.; He, H.; E, C.; Chawchai, S.; Zheng, H.; Li, X. Tropical Pacific Forcing of Hydroclimate in the Source Area of the Yellow River. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2021GL095876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Z.; Colman, S.M.; Zhou, W.; Li, X.; Brown, E.T.; Jull, A.J.; Cai, Y.; Huang, Y.; Lu, X.; Chang, H.; et al. Interplay between the Westerlies and Asian monsoon recorded in Lake Qinghai sediments since 32 ka. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhao, C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Liu, W.; Yu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Ito, E. Holocene climate controls on water isotopic variations on the northeastern Tibetan Plateau. Chem. Geol. 2016, 440, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Dou, H. A Directory of Lakes in China; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1998. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Z.D.; Bickle, M.J.; Chapman, H.J.; Yu, J.M.; An, Z.S.; Wang, S.M.; Greaves, M.J. Ostracod Mg/Sr/Ca and 87Sr/86Sr geochemistry from Tibetan lake sediments: Implications for early to mid-Pleistocene Indian monsoon and catchment weathering. Boreas 2011, 40, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radbourne, A.D.; Ryves, D.B.; Anderson, N.J.; Scott, D.R. The historical dependency of organic carbon burial efficiency. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2017, 62, 1480–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcocer, J.; Ruiz-Fernandez, A.C.; Escobar, E.; Perez-Bernal, L.H.; Oseguera, L.A.; Ardiles-Gloria, V. Deposition, burial and sequestration of carbon in an oligotrophic, tropical lake. J. Limnol. 2014, 73, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortino, K.; Whalen, S.C.; Johnson, C.R. Relationships between lake transparency, thermocline depth, and sediment oxygen demand in Arctic lakes. Inland Waters 2014, 4, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartosiewicz, M.; Przytulska, A.; Lapierre, J.-F.; Laurion, I.; Lehmann, M.F.; Maranger, R. Hot tops, cold bottoms: Synergistic climate warming and shielding effects increase carbon burial in lakes. Limnol. Oceanogr. Lett. 2019, 4, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobek, S.; Durisch-Kaiser, E.; Zurbrügg, R.; Wongfun, N.; Wessels, M.; Pasche, N.; Wehrli, B. Organic carbon burial efficiency in lake sediments controlled by oxygen exposure time and sediment source. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2009, 54, 2243–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, B.H. Nitrogen mineralization in relation to C:N ratio and decomposability of organic materials. Plant Soil 1996, 181, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.; Ji, J.; Barrón, V.; Torrent, J. Climatic thresholds for pedogenic iron oxides under aerobic conditions: Processes and their significance in paleoclimate reconstruction. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2016, 150, 264–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsam, W.; Ji, J.; Renock, D.; Deaton, B.C.; Williams, E. Determining hematite content from NUV/Vis/NIR spectra: Limits of detection. Am. Mineral. 2014, 99, 2280–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Shen, J.; Balsam, W.; Chen, J.; Liu, L.; Liu, X. Asian monsoon oscillations in the northeastern Qinghai–Tibet Plateau since the late glacial as interpreted from visible reflectance of Qinghai Lake sediments. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2005, 233, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, R.Y.; Milliken, R.E.; Russell, J.M.; Sklute, E.C.; Dyar, M.D.; Vogel, H.; Melles, M.; Bijaksana, S.; Hasberg, A.K.M.; Morlock, M.A. Iron Mineralogy and Sediment Color in a 100 m Drill Core From Lake Towuti, Indonesia Reflect Catchment and Diagenetic Conditions. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 2021, 22, e2020GC009582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gälman, V.; Rydberg, J.; de-Luna, S.S.; Bindler, R.; Renberg, I. Carbon and nitrogen loss rates during aging of lake sediment: Changes over 27 years studied in varved lake sediment. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2008, 53, 1076–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Zhang, E.; Liu, E.; Chang, J.; Shen, J. Linkage between Lake Xingkai sediment geochemistry and Asian summer monsoon since the last interglacial period. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2018, 512, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wu, C.; Xie, D.; Ma, J. Sources, Migration, Transformation, and Environmental Effects of Organic Carbon in Eutrophic Lakes: A Critical Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, J.A.; Jones, I.D.; Thackeray, S.J. Testing the Sensitivity of Phytoplankton Communities to Changes in Water Temperature and Nutrient Load, in a Temperate Lake. Hydrobiologia 2006, 559, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, M.; Liboriussen, L.; Lauridsen, T.; SØNdergaard, M.; SØNdergaard, M.; Jeppesen, E. Effects of increased temperature and nutrient enrichment on the stoichiometry of primary producers and consumers in temperate shallow lakes. Freshw. Biol. 2008, 53, 1434–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Zhang, K.; Lin, Q.; Huang, S.; Han, Y.; Shen, J. Glacier Meltwater Input and Salinity Decline Promote Algal Growth in a Tibetan Saline Lake. Freshw. Biol. 2025, 70, e70010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, J.; Jonsson, A.; Jansson, M. Productivity of high-latitude lakes: Climate effect inferred from altitude gradient. Glob. Change Biol. 2005, 11, 710–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Liu, E.; Zhang, E.; Bindler, R.; Nath, B.; Zhang, K.; Shen, J. Spatial variation of organic carbon sequestration in large lakes and implications for carbon stock quantification. CATENA 2022, 208, 105768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander, D.; McKenzie, J.; Ten Haven, L. A 200 year sedimentary record of progressive eutrophication in Lake Greifen (Switzerland): Implications for the origin of organic-carbon-rich sediments. Geology 1992, 20, 825–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.R. Carbon Fixation, Flux and Burial Efficiency in Two Contrasting Eutrophic Lakes in the UK (Rostherne Mere & Tatton Mere). Ph.D. Thesis, Loughborough University, Loughborough, England, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, N.J.; Dietz, R.D.; Engstrom, D.R. Land-use change, not climate, controls organic carbon burial in lakes. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2013, 280, 20131278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Anderson, N.J.; Yang, X.; Chen, X.; Shen, J. Carbon burial by shallow lakes on the Yangtze floodplain and its relevance to regional carbon sequestration. Glob. Change Biol. 2012, 18, 2205–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Yao, S.; Xue, B.; Lu, X.; Gui, Z. Organic carbon burial in Chinese lakes over the past 150 years. Quat. Int. 2017, 438, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Xue, B.; Yao, S.; Gui, Z. Organic carbon burial from multi-core records in Hulun Lake, the largest lake in northern China. Quat. Int. 2018, 475, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.