Abstract

This study aimed to design a new composite with promising antimicrobial and antioxidant properties by a simple modification process of natural bentonite (B) with polysaccharide chitosan isolated from edible mushrooms Agaricus bisporus—ChM (sample B–ChM) and subsequently with a cationic surfactant—hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide—HB (sample B–ChM–HB) for effective removal of mycotoxin zearalenone (ZEN). Characterization confirmed the presence of ChM in B–ChM and both ChM and HB in B–ChM–HB. Compared to non- or slightly inhibitory activity of B and B–ChM, B–ChM–HB showed fungicidal activity against yeast Candida albicans and mycotoxigenic mold Aspergillus flavus, with a reduction of 6.00 log10 (CFU/mL) and 5.32 log10 (CFU/mL), respectively. B–ChM–HB showed a very high neutralization ability on •DPPH (89.03%–95.99%) in the concentration range of 0.625–5.0 mg/mL, the highest ferrous ion chelating ability (80.25%) at a concentration of 0.625 mg/mL, and did not induce lipid peroxidation in the linoleic acid model system. While B and B–ChM exhibited low adsorption of ZEN, its adsorption by B–ChM–HB was significantly higher. The equilibrium results of B–ChM–HB for ZEN were in accordance with the linear isotherm model at pH 3 and 7, pointing out that hydrophobic interactions (partitioning process) were relevant for toxin adsorption by the composite. Similar maximum ZEN adsorbed amounts under the applied experimental conditions (14.4 mg/g) at both pH values suggested that its adsorption was independent of the pH. This study reported for the first time that a novel composite of B with ChM and HB showed promising antimicrobial and antioxidant properties and was an efficient adsorbent for mycotoxin ZEN.

1. Introduction

Mycotoxins are a large group of secondary metabolic products of fungi, which pose a huge health threat to animals and humans [1]. As a result, mycotoxin contamination remains a long-lasting and significant problem in agricultural systems and food quality control [2]. One of the most concerning among them is zearalenone (ZEN), a mycotoxin with strong estrogenic activity, produced primarily by Fusarium species that frequently colonize cereal crops, including maize, wheat, sorghum, rye, rice, and barley. Its structural similarity to natural estrogens allows it to bind to estrogen receptors, leading to hormonal imbalances and reproductive disorders, particularly in monogastric animals [3]. Furthermore, ZEN is chemically stable and resistant to degradation, making its removal from food and feed particularly challenging. Over the past decades, various decontamination strategies have been explored, including heat treatment, irradiation, adsorption, treatment with acids, alkalis, or oxidizing agents, as well as biological methods involving microorganisms and enzymes. Among these methods, adsorption has appeared as one of the most effective techniques due to its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and high efficiency [4]. Natural clay minerals, such as bentonite, have been widely studied as adsorbents for mycotoxins, due to their high surface area, layered structure, and cation exchange capacity (CEC) [5,6,7,8]. Bentonite is a natural raw material consisting mainly of the clay mineral montmorillonite-dioctahedral 2:1 layer aluminosilicate of the smectite group. The predominantly negative hydrophilic surface of montmorillonite exhibits a low affinity for low-polar molecules. To enhance its adsorption efficiency, various modifiers, including surfactants and, more recently, biopolymers (e.g., chitosan), have been investigated [9,10,11].

Surfactants, especially the cationic type, are often applied for the modification of montmorillonite surface properties from hydrophilic to hydrophobic, increasing its affinity toward low-polar molecules. Cationic surfactants possess a hydrophilic head and a long hydrophobic tail, and the adsorption behavior of organominerals obtained by modification with different types of surfactants influences the adsorption of different low-polar organic molecules and affects the organomineral’s adsorption capacity [12]. Organomontmorillonites obtained by modification of montmorillonite with two cationic surfactants—monoalkyl octadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (OTAB) and dialkyl dioctadecyldimethylammonium chloride (DODAC)—in amounts of 50, 100, 150, and 200% of clay CEC were tested as adsorbents of the mycotoxins aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) and ZEN [13]. Both types of organomontmorillonites showed enhanced AFB1 and ZEN adsorption capacities in single and binary contaminant systems compared with the raw montmorillonite. Montmorillonites modified with DODAC showed a higher adsorption capacity towards AFB1 and ZEN than montmorillonites containing OTAB.

Recently, chitosan (CTS), a natural polysaccharide, due to its availability, biodegradability, non-toxicity, antibacterial, and antioxidant activities, has been intensively investigated as a valuable biopolymer for various applications [10,11]. Chitosan is commonly obtained by the deacetylation of chitin, a structural biopolymer that occurs in the exoskeletons of crustaceans and insects, as well as in the cell walls of fungi, including safe-to-eat mushrooms [14]. Chitosan derived from both marine and fungal sources shares the same fundamental chemical structure, composed of β(1→4)-linked D-glucosamine and N-acetyl-D-glucosamine units [15]. CTS may also act as an adsorbent because it contains hydroxyl (-OH) and amino (-NH2) groups that represent binding sites for different molecules [16]. Its cationic nature facilitates strong interactions with negatively charged montmorillonite surfaces, thereby enhancing the adsorption capacity of the resulting composites. These composites combine hybrid properties of both constituents and are often considered “biocomposites” or “green composites” [17]. In the study of Wang et al. [10], surface functionalization of montmorillonite with CTS was performed via the hydrothermal method at 180 and 250 °C, and the prepared composites were tested as adsorbents of AFB1 and ZEN. Protonated amine and amide functional groups at the surface of montmorillonite provided sites for the adsorption of AFB1, while the increased organic carbon content was responsible for interactions with ZEN.

During the last decade, studies have reported the synthesis of novel composites of montmorillonite with both polymers and cationic surfactants (especially surfactants with a 16-carbon alkyl chain, such as hexadecyltrimethylammonium—HB, widely used in the pharmaceutical industry) for the removal of various types of contaminants. El-Dib et al. [16] investigated composites obtained by immobilization of CTS on bentonite (CIB) and additionally with HB in an amount equivalent to 300% of clay CEC (mCIB) for color removal and chemical oxygen demand (COD) reduction in distilleries wastewater. They reported that mCIB was the most effective adsorbent with 83% COD reduction and 78% color removal. In another study, montmorillonite was modified with both HB and CTS, and the adsorbents were tested for the removal of phenol, heavy metal (Cd2+), and dyes (Congo red (CR) and crystal violet (CV)) from a water solution. In the composites, the added amount of HB was equal to 60% of montmorillonite’s CEC, while the amounts of CTS were 2%, 4%, or 6% of montmorillonite’s weight [11]. The authors reported that modification with HB increased phenol adsorption, while after modification with CTS, phenol adsorption further increased. However, so far, there are no systematic studies in the literature concerning the investigations of composites of montmorillonite with surfactants and polymers as adsorbents of mycotoxins.

Aside from their adsorptive properties, the antibacterial and antioxidant activities of minerals and their composites are very important for potential practical applications. It was documented that surfactant- and/or CTS-modified minerals have antimicrobial properties. For example, Schulze-Makuch et al. [18] reported that zeolite–clinoptilolite modified with HB was bactericidal and removed viruses (about 99%) and Escherichia coli (100%) from contaminated water. In addition, the antibacterial and antifungal properties of Na-montmorillonite modified with HB (0.1 g) and subsequently with different amounts of CTS (1, 5, and 25%) were recently tested by Cabuk et al. [19]. The authors showed enhanced antibacterial and antifungal effects for composites containing montmorillonite with surfactant and CTS against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria compared with pure CTS and Na-bentonite.

The aim of this study was (a) to synthesize a novel composite of bentonite with CTS extracted from edible mushroom Agaricus bisporus and subsequently with surfactant–HB (used in amount equal to 50% CEC of montmorillonite); (b) to determine the antimicrobial and antioxidative properties of the starting bentonite, bentonite modified with CTS, as well as bentonite modified with CTS and HB; and (c) to evaluate the efficiency of bentonite and composites to adsorb ZEN under in vitro conditions. Physicochemical characterization of the raw bentonite and the composites was achieved by X-ray powder diffraction (XRPD), thermal analysis (thermogravimetry (TG) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and low-temperature N2 physisorption. Zearalenone adsorption was followed under different conditions—initial ZEN concentrations, amounts of adsorbent(s) in suspension, and solution pH values in order to evaluate the best operating parameters for mycotoxin adsorption. This research reported, for the first time, a novel multifunctional composite containing bentonite, CTS isolated from edible mushrooms Agaricus bisporus, and a cationic surfactant HB with antimicrobial, antioxidant, and mycotoxin adsorptive properties that may be suitable as an animal feed additive.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Composites

Raw bentonite from the Beretnica locality in the Republic of Serbia was used as a starting material.

The starting bentonite was wet sieved to yield particles <37 μm and then used without any further purification (sample B). The CEC of B was 120.4 meq/100 g (determined with the 1 M NH4Cl method). The chemical composition of B was as follows: 64.67% SiO2, 15.59% Al2O3, 3.16% Fe2O3, 0.50% TiO2, 5.17% CaO, 1.99% MgO, 0.28% Na2O, and 0.68% K2O, with 7.84% ignition loss [20].

The bentonite was modified with polysaccharide chitosan isolated from the edible mushrooms Agaricus bisporus (ChM) (Delta Danube LLC, Kovin, Serbia) and a cationic surfactant—HB. The chitosan (ChM) was isolated in laboratory conditions from Agaricus bisporus mushroom (degree of deacetylation 92.7%; β-glucans content 229.7 mg/g). The procedure for the isolation of ChM was given elsewhere [21]. In the first step, ChM solution (0.5 g/L) prepared in 1% (v/v) acetic acid (Centrohem, Stara Pazova, Serbia) was slowly added to the bentonite suspension (10% w/v). After stirring at 6000 rpm for 30 min at 50 °C, the obtained composite (sample B–ChM) was separated by a filtration process and dried at 60 °C for 24 h. In the second step, the B–ChM was further modified with HB (Sigma-Aldrich Co., Munich, Germany). The amount of HB used for the modification of B–ChM was equal to 50% of the CEC of B. The modification process was as follows: a certain amount of B–ChM (5 g) was suspended in distilled water (100 mL), mixed for 10 min, and treated with 1.1 g of HB dissolved in 50 mL of distilled water. The suspension was stirred at 6000 rpm for 15 min at 50 °C, then filtered, washed to remove possible excess of HB or bromide, and dried at 60 °C. The composite was denoted as B–ChM–HB.

2.2. Physicochemical Characterization of B and Composites B–ChM and B–ChM–HB

The physicochemical characterization of various materials (B, B–ChM and B–ChM–HB) was performed by X-ray diffraction (XRD), thermal analysis (thermogravimetry (TG) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and N2 physisorption at 77 K.

Qualitative XRD analysis was conducted using an X-ray diffractometer PW 1710 Instrument, Philips (Eindhoven, The Netherlands), using CuKα radiation (λ = 1.54178 Å). XRD data were measured at room temperature with a step size of 0.01° and a time/step of 1 s in the range from 4° to 65° 2θ. Thermal analysis (DSC/TG) was carried out on an STA 449 F5 Jupiter Simultaneous Thermal Analyzer with Proteus® software version 8.0.3 produced by Netzsch, Selb, Germany. The samples were heated from 25 to 1000 °C at a rate of 10 °C min−1 using a Pt-Pt10%Rh thermocouple and Pt80Rh20 crucibles with lids. An empty crucible with a lid was used as a DSC reference. During the analysis, protective gas (20 mL/min synthetic air) and purge gas (50 mL/min synthetic air) were continuously used. Prior to analysis, the samples were dried at 50 °C for 2 h and then kept in a desiccator over a saturated solution of NH4Cl (relative humidity of 75%) for 24 h.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to determine the morphological and chemical characteristics. Investigations were performed on the JSM-7001F instrument, JEOL (Tokyo, Japan) equipped with an energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS). The analyses were performed under high vacuum at an accelerating voltage of 30 kV, a probe current of approx. 1 nA, and a working distance of 6 mm. Prior to the analysis, the samples were coated with gold, producing a 15 nm thick electrically conductive coating.

The textural properties of the B and composites were determined based on nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms obtained at 77 K using a Sorptomatic 1990 apparatus (Thermo Finnigan, Milan, Italy). Before measurement, the composites were transferred to a sample cell and placed at the preparation site for degassing. The samples were degassed under vacuum for 4 h at room temperature, followed by another 48 h at 283 K under a vacuum higher than 0.3 Pa. This procedure ensures the removal of any adsorbed H2O and CO2 and prevents possible sample degradation. The obtained N2 isotherms were analyzed using ADP 5.13 Thermo Electron Software. The specific surface areas (SBET) and C constant (CBET) of the samples were calculated using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method [22]. The part of the adsorption isotherms for the SBET and CBET calculations was selected according to the Rouquerol criteria [23]. The Dubinin–Radushkevich method [24] was used to determine the micropore volume (Vmic), while the mesopore volume (Vmes) was estimated from the adsorption part of the isotherm for a relative pressure range (p/p0) corresponding to the mesopores region (2–50 nm). The total pore volume (Vtot) was estimated by applying the Gurvitch rule [22] at a p/p0 = 0.98.

2.3. Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Experiments

2.3.1. Antioxidant Activity Test

Suspensions of B, ChM, B–ChM, and B–ChM–HB at the concentration range of 0.625–5.0 mg/mL in MiliQ water were analyzed for all antioxidant assays. Three methods based on electron transfer (ET), hydrogen atom transfer (HAT), and proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) and the ability to chelate transition metal ions were used to evaluate the radical-blocking capacities: 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl free radical (•DPPH) neutralization ability (NA•DPPH), inhibition of lipid peroxidation (LPx) in a linoleic acid model system, and ferrous-ion (Fe2+) chelating ability, as described in detail in a previous publication by Kozarski et al. [25]. In all methods, the suspensions were continuously stirred on a magnetic stirrer at 200 rpm during the analysis period. Before measuring the absorbance, the resulting solutes were finally centrifuged in a Boeco M-240R centrifuge (6000 rpm, 4 °C, 30 min) to separate the insoluble and soluble fractions. The supernatant (soluble part) was collected for further absorbance measurement on a UV–VIS 1800 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan).

All determinations were carried out in triplicate, in all assays, and the results were expressed as: % of NA•DPPH, % of inhibition of linoleic acid peroxidation, and % of Fe2+ chelation. Ascorbic acid, α tocopherol, citric acid, and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) were used as positive controls. They are common additives in food formulations and are typically used at mg levels.

2.3.2. Antifungal Activity Test

Bentonite, ChM, B–ChM, and B–ChM–HB were hot-air dried (60 °C, 4 h) and additionally treated with UV-light for 30 min. The yeast strain Candida albicans ATCC 10231 was used in the test, as well as the isolate of the mycotoxigenic mold Aspergillus flavus (isolate 4846, Maize Institute “Zemun Polje”, Zemun, Serbia). The suspensions of the samples were prepared following the method of Johnson et al. [26], with slight modification in the concentration of 100 mg/mL PBS (Phosphate Buffered Saline (Sigma Aldrich), pH 7.2, containing Na3PO4 and NaCl: malt broth in ratio 1:1). ChM was prepared in 0.125% acetic acid at concentration of 20 mg/mL and additionally diluted up to 10 mg/mL in PBS pH 7.2. This concentration of acetic acid was used, since it did not have an inhibitory effect on microorganisms.

The test culture of C. albicans was inoculated for 48 h at 30 °C in malt broth (HiMedia, Mumbai, India). The density of the yeast suspension was adjusted to 106 CFU/mL. A quantity of 0.1 mL was added to all the tested samples. The test tubes were incubated in an orbital shaker (120 rpm, 30 °C, 48 h) to avoid precipitation of samples. Suspensions without the addition of yeast were used as a negative control. After incubation, the samples were serially diluted in physiological solution (water solution containing 0.85% NaCl) and inoculated onto malt agar (HiMedia Laboratories, Mumbai, India). Colonies were counted after plate incubation (48 h at 30 °C), and the results were expressed as log10 (CFU/mL).

A 5-day-old culture of A. flavus grown on malt agar was used. Spores were washed with physiological solution and then prepared by transferring 1 mL of spores to 9 mL of physiological solution. Previously prepared A. flavus spores [27], 0.1 mL, were added to the samples. After 48 h of incubation in an orbital shaker (120 rpm, 25 °C), the samples were serially diluted in physiological solution and inoculated on SD agar (HiMedia Laboratories, Mumbai, India). Colonies were counted after plate incubation (48 h at 25 °C), and the results were expressed as log10(CFU/mL).

The antifungal activity of the materials (R) was determined as a reduction of log10(CFU/mL) of the tested strains during the incubation, according to Equation (1) [28]:

where Nc and Nt represent the average number of viable fungal cells after 48 h of incubation with the control and the tested materials, respectively.

R = log10(Nc/Nt),

Additionally, the antifungal activity of the reference fungicide amphotericin B (50 µg/mL) was tested against the investigated microorganisms as a positive control.

2.3.3. Statistical Analysis

For the determinations described in Section 2.3.1 and Section 2.3.2, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed for the comparison of mean values, which were further separated using Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) at p ≤ 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed with the Statistica 12.0 software package (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA).

2.4. Zearalenone Adsorption

Zearalenone was supplied from Romer Labs (Biopure), Tulln, Austria. The primary ZEN stock solution (1000 mg/L) was prepared in acetonitrile and then used to prepare test solutions of the ZEN for adsorption studies in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 3 and 7). The preliminary adsorption of ZEN by B, B–ChM, and B–ChM–HB was investigated with the initial ZEN concentration of 4.0 mg/L, with 1 g/L of each adsorbent, at pH 3 and 7. The adsorption of ZEN by B–ChM–HB was further studied with the same initial ZEN concentration and with different amounts of each adsorbent in suspension (2, 1, 0.5, and 0.2 g/L) at pH 3 and 7. The zearalenone adsorbed amount (%), Cads, was calculated by the following Equation (2):

where C0 and Ce (mg/L) are the initial and equilibrium solution concentrations of ZEN, respectively.

To determine the adsorption isotherms, ZEN adsorption onto B–ChM–HB was followed with different initial concentrations (1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5, 3.0, 3.5, 4.0, and 4.5 mg/L) with 2 mg of adsorbent, at pH 3 and 7. In all experiments, suspensions were shaken for 30 min at room temperature using a laboratory shaker (Heidolph Unimax 1010, Schwabach, Germany) with the speed adjusted to 300 rpm and then centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 3 min. The initial concentrations of ZEN and those in the supernatants after equilibrium were determined by high performance liquid chromatography—HPLC (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The limit of detection (LOD) for HPLC was 0.02 mg/L, as automatically calculated by the LabSolutions software version 5.54. The HPLC system included a pump LC-20AD, autosampler SIL-20A HT, and fluorescence detector RF-20A (λex = 274 nm, λem = 430 nm). Chromatographic separations were carried out on an Inertsil® ODS-4 (150 × 4.6 mm, C18, 5 µm particle size) column, and the mobile phase was acetonitrile:water:acetic acid (60:40:1), pumped at a flow rate of 1 mL/min, using isocratic elution. All ZEN adsorption experiments were carried out in duplicate, and the average values were reported to minimize random measuring error.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physicochemical Characterization of B–ChM and B–ChM–HB Composites

For the preparation of B–ChM, ChM was dissolved with acetic acid, and the NH2 groups on ChM were protonated, i.e., positively charged; thus, they can interact with negatively charged montmorillonite surface, replace inorganic cations in the interlayer space via ion exchange, or ChM can interact with silicate hydroxylated edge groups [11,29].

Modification of B–ChM with HB ions was performed by using the HB in an amount below the CEC of B (50% CEC of B). Usually, when the amount of surfactant is below or equal to the CEC of specific bentonite, modifications include ion exchange, and during this process, inorganic cations from the interlayer space of montmorillonite are replaced with surfactant ions [30]. In B, the dominant cation in the exchangeable position was calcium (Ca2+ = 99.8 meq/100 g), while magnesium, sodium, and potassium were present in much lower amounts (Mg2+ = 17.9 meq/100 g; Na+ = 1.7 meq/100 g and K+ = 1.0 meq/100 g) [20]. In order to follow the modification of B with ChM and subsequently with HB, the amounts of inorganic cations released from B during the preparation of B–ChM and B–ChM–HB were determined in the supernatants by atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS), and the results are presented in Table 1. For B–ChM–HB, the amounts of released inorganic cations were compared with the amount of HB used for modification.

Table 1.

Amounts of inorganic cations released during the preparation of B–ChM and B–ChM–HB.

For B–ChM, comparison of the CEC of B (120.4 meq/100 g) with the amount of inorganic cations released from B during preparation of the composite (14.6 meq/100 g) indicates that ChM polysaccharide interacts with the surface of montmorillonite or with the silicate hydroxylated edge groups rather than by replacement of inorganic cations. Concerning B–ChM–HB, the amount of inorganic cations released from montmorillonite during the modification process (48.6 meq/100 g) was almost equal to the amount of HB used for modification (~55 meq/100 g), indicating almost quantitative cation exchange. Since the surface of B–ChM–HB and/or the silicate hydroxylated edge groups were already occupied with ChM polysaccharide, the HB cations were probably adsorbed by the replacement of available inorganic cations in the interlayer space of B–ChM, as well as at its external surface.

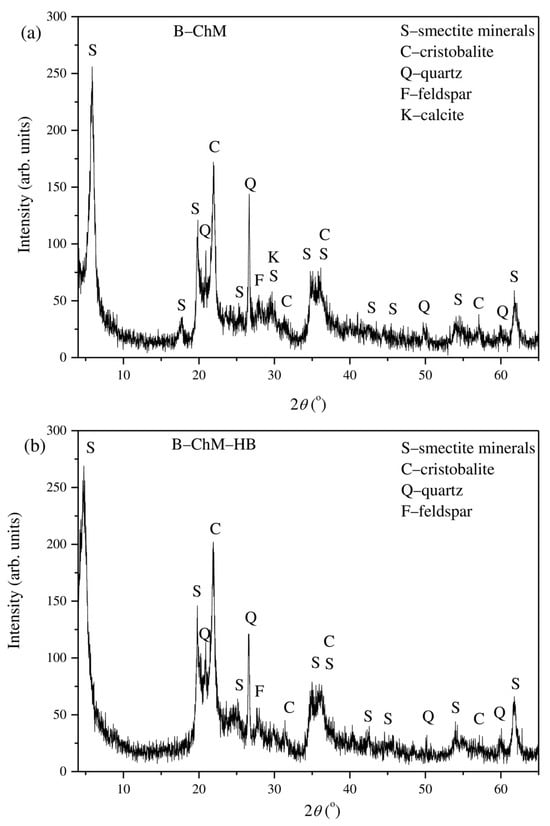

3.1.1. XRD Analysis

X-ray diffraction is the common method to investigate the layered structure and the basal spacing of organobentonites. The intercalation and molecular conformation of the intercalated alkyl chains of surfactants into the montmorillonite interlayer space can be indirectly obtained from the basal spacing. Depending on the charge density of the clay and surfactant loading levels, the intercalated surfactants can adopt monolayer, bilayer, pseudotrimolecular, or paraffin-type arrangements [31].

The XRD results of B–ChM and B–ChM–HB are presented in Figure 1. Previous analysis of the B showed that the sample mainly consisted of dioctahedral smectite montmorillonite based on the positions of diagnostic diffraction peaks, while accessory minerals were quartz, feldspar, cristobalite, and calcite [20]. For B, the montmorillonite 001 reflection (d001) was 15.2 Å, corresponding to a two-water-layer hydration state of alkaline–earth–smectite consistent with calcium as the dominant interlayer cation [32]. The XRD pattern of B–ChM showed a basal reflection (001) d001 = 15.1 Å. The d-spacing of B–ChM increased after modification with HB (18.5 Å), which was a confirmation that long-chain organic cations were mainly intercalated into the interlayer space of montmorillonite and was an indication of developing bilayer arrangement for HB in the interlayer space of Ca–montmorillonite (B) [31]. The obtained results were similar to the results of El-Dib et al. [16] for CTS immobilized onto bentonite and additionally modified with cetyltrimethylammonium ions—CTAB (HB). They reported only a slight increase in the basal spacing of bentonite after immobilization of CTS (from 13.6 Å to 14.5 Å), while the interlayer spacing gradually increased for the sample additionally modified with HB (19.4 Å), suggesting that the alkylammonium ions formed double layers with alkyl chains lying parallel to the surface of montmorillonite.

Figure 1.

XRD pattern of (a) B–ChM and (b) B–ChM–HB.

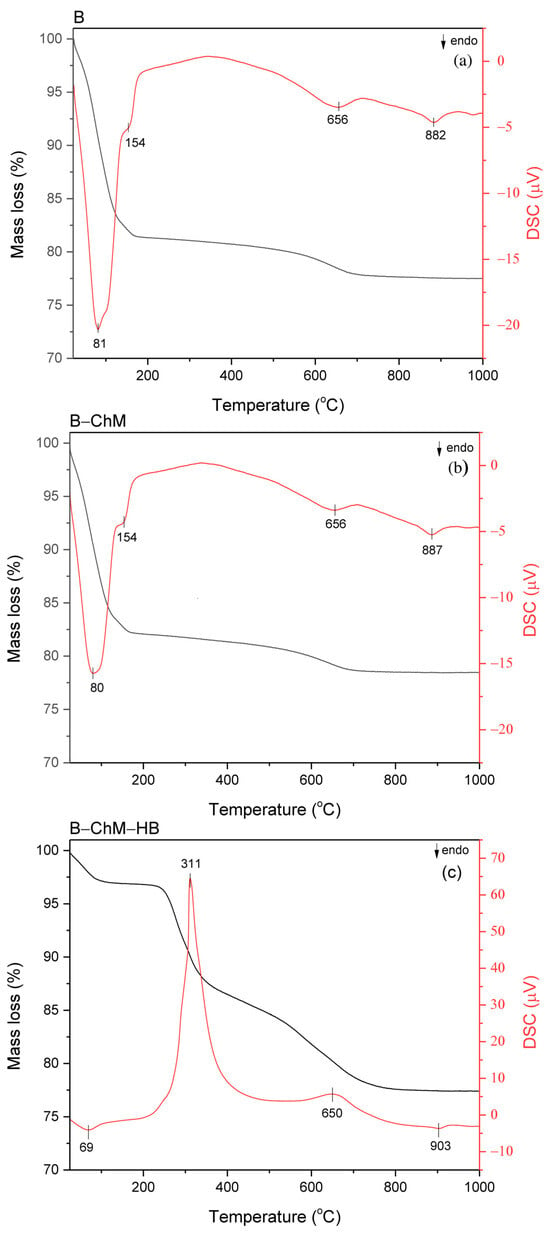

3.1.2. Thermal Analysis

Clay minerals are usually thermally characterized by three reactions: dehydration (25–300 °C), dehydroxylation (300–700 °C), and decomposition/recrystallization (>800 °C) [33,34]. Thermal (DTA or DSC) curves of many organo-clay complexes are usually characterized with the following reactions: the dehydration of the clay (<200 or 250 °C), the thermal reactions of the organic substances intercalated into the interlayer space of clay (200–500 °C), and the dehydroxylation of the clay and recrystallization of the meta-clay (>500 or 600 °C). For organo-smectite complexes, the exothermic oxidation occurs during the gradual heating of the sample in two steps, in the temperature range 200–500 °C and 400–750 °C. The exothermic peak temperature depends on the type of clay mineral and on the organic phase used for modification [35].

The DSC and TG curves of B, B–ChM, and B–ChM–HB are presented in Figure 2a–c, and the mass losses for each sample in different temperature regions are given in Table 2. The DSC curves of B and B–ChM (Figure 2a,b) showed one sharp endothermic dehydration peak at 80 °C with a weak shoulder at 154 °C, which is characteristic of Ca–bentonites. The endothermic dehydration peak corresponds to the evolution of adsorbed H2O and H2O around the interlayer inorganic cations in the exchangeable sites of montmorillonite. In this region, mass losses from the TG curve were 18.5% for B and 17.8% for B–ChM. A slight decrease in the intensity of the first endothermic peak, as well as the decrease in the mass loss, may indicate a slight increase in the hydrophobicity of B–ChM related to the presence of ChM at the surface of the composite. For B–ChM–HB, in the first temperature region, on the DSC curve, a significant decrease in the intensity of the first endothermic peak was observed, as well as the shift of this peak toward lower temperatures (from 80 °C to 69 °C). Compared to the mass loss of B–ChM (17.8%), the significantly lower mass loss B–ChM–HB from the TG curve was noticed (3.1%). The decrease was mainly caused by the replacement of hydrated cations in montmorillonite by the HB ions confirming the increased hydrophobicity of B–ChM–HB. In the second temperature region, at the DSC curves of B and B–ChM, an endothermic peak at 656 °C related to the dehydroxylation was visible. For B–ChM–HB, a sharp high intensity exothermic peak at 311 °C, as well as a low intensity exothermic peak at 650 °C, were noticed on the DSC curve. These peaks originated from the decomposition of intercalated HB ions from B–ChM–HB. The endothermic dehydroxylation peak (~650 °C) was not visible in the DSC curve, probably due to the overlap with the exothermic peak from HB. In this region, the mass loss increased from 3.7% for B–ChM to 18.9% for B–ChM–HB. The endothermic peak at temperatures above 880 °C visible in the DSC curves of all samples was related to the decomposition/recrystallization of montmorillonite and was not accompanied by mass loss at the TG curves.

Figure 2.

DSC (red line) and TG (black line) curves of (a) B, (b) B–ChM, and (c) B–ChM–HB.

Table 2.

Mass losses in different temperature regions for B, B–ChM, and B–ChM–HB.

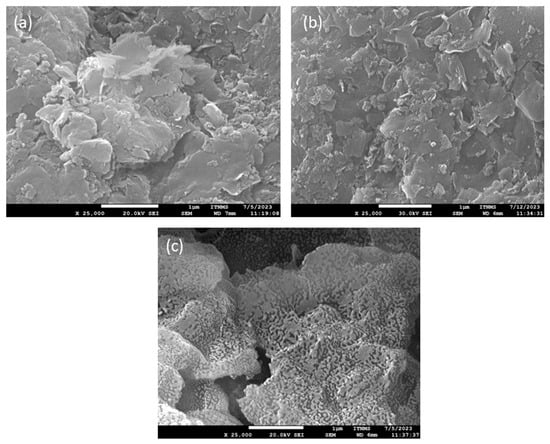

3.1.3. SEM Analysis

SEM images of B, B–ChM, and B–ChM–HB are presented in Figure 3a–c. The surface morphology of B was rough and curling, typical of a lamellar structure of montmorillonite. The individual particles, most of them having clearly recognizable contours, are irregular platelets and tend to form thick and large agglomerates (Figure 3a). Compared to the B, B–ChM showed a slightly smooth surface with accumulation of irregular shapes, resulting from the accumulation of ChM, probably mostly at the external clay surfaces (Figure 3b) [16]. Cabuk et al. [29], reported SEM images of bentonite modified with HB and CTS at three different CTS:bentonite ratios: K1 = CTS (1%)/bentonite (99%), K5 = CTS (5%)/bentonite (95%), and K25 = CTS (25%)/bentonite (75%). They stated that the SEM images of the K1, K5, and K25 composites showed that sponge-like structures of bentonite particles were surrounded by closely packed CTS molecules, which supported the formation of the CTS/bentonite composite. According to their images, CTS was not only intercalated inside the interlayer spaces of bentonite but also settled on the surface of bentonite layers (flocculated). The SEM image of B–ChM–HB showed a significant change in the surface morphology compared with the morphology of B–ChM (Figure 3c). This suggest that further modification of B–ChM with HB showed a tendency to produce expanded flattened aggregates of HB ions with flat branched deposits of irregular forms at the surface of B–ChM–HB [30]. Similarly, in the study of Dos Santos et al. [36], SEM images of montmorillonite modified with HB showed the increased size of the fragments due to the expansion of the lamellar spacing as a result of the intercalation of surfactant ions.

Figure 3.

SEM micrographs of (a) B, (b) B–ChM, and (c) B–ChM–HB at a magnification of 25,000×.

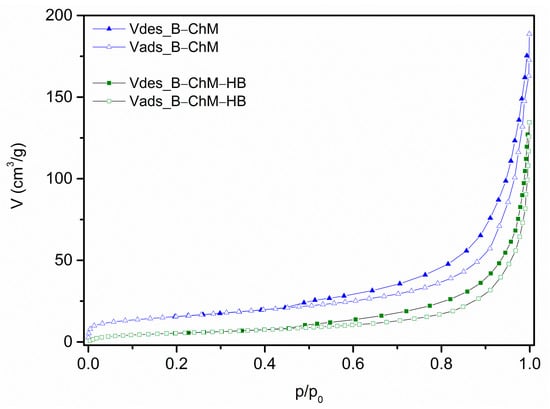

3.1.4. Textural Properties

The nitrogen physisorption isotherms for the B–ChM and B–ChM–HB, presented in Figure 4, have a similar shape to the previously reported isotherm for the B [20]. The textural properties for B, B–ChM, and B–ChM–HB are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 4.

N2 isotherms at 77 K of B–ChM and B–ChM–HB.

Table 3.

Textural properties of B, B–ChM, and B–ChM–HB.

The initial part of all isotherms (including previously reported isotherm for B) exhibited an increase in the adsorbed nitrogen volume, followed by a moderate nearly linear increase up to a relative pressure of 0.7–0.8. This was succeeded by a sharp rise in the high p/p0 region. According to the IUPAC nomenclature, these are type II isotherms [37], which are characteristic of non-porous and macroporous materials. However, a noticeable hysteresis loop was present in all three isotherms. The desorption branches for each sample follow a path similar to their corresponding adsorption branch but are slightly shifted towards higher values of adsorbed nitrogen volume for the same p/p0 value. The shape of this loop belongs to type H3 according to the IUPAC nomenclature. This type of loop is associated with the existence of non-rigid aggregates of plate-like particles in the sample, which form slit-like pores. This form of isotherm, referred to as type IIb by F. Rouquerol et al. [22], can be found in numerous materials and is also typical for clays [22]. The disappearance of the hysteresis loop at a p/p0 value of approximately 0.42 is a consequence of the cavitation of liquid N2, also known as the tensile strength effect [38]. This phenomenon is present in pores with a width smaller than this p/p0 value during measurements at 77 K.

Comparing the isotherms of B [20] and B–ChM, it appears that the modification of B with ChM only slightly changes the textural properties of the resulting composite. Indeed, the results shown in Table 3 reveal that, after modification with ChM, the SBET changes by only 11% (from 63 m2/g for B to 56 m2/g for B–ChM), while the Vmic value showed a similar change (a decrease of about 12%). The change in the mesopore volume (Vmes) was significantly smaller (1.2%) and is practically within the limits of the measurement error, while the total pore volume (Vtot) did not change. The difference in the percentage reduction values for Vmic, Vmes, and Vtot indicates the dominant spatial level of ChM’s action as a modifier. It is worth mentioning that the reduction values for Vmic and SBET after modification with ChM are almost perfectly consistent with the reduction in the amount of exchangeable cations (Table 1), specifically the 12.1% of inorganic cations released from B during B–ChM preparation (14.6 meq from the initial 120.4 meq).

The synthesis of the B–ChM–HB resulted in a much more pronounced change in the textural properties, characterized by a significant reduction in all the measured values. In this case, the reduction in Vmic was the most significant (over 59% of the value of the B–ChM). Furthermore, the reductions in Vmes and Vtot were also significant (approximately 42% and 45%, respectively). Considering the results from Table 1, which showed that approximately 46% of the remaining exchangeable inorganic cations from B–ChM were released during the preparation of B–ChM–HB, it is reasonable to assume that the position of HB binding to B–ChM differs from that of ChM binding to the initial B. The binding of the polar HB head via a cation exchange mechanism from the interlamellar space led to a reduction in the micropore volume by simply blocking the interlamellar entrances. Concurrently, the large nonpolar tails, in combination with a small amount of non-binding HB molecules, cover the interspace, reducing the volume of larger pores. All these factors resulted in a significant decrease in the SBET, down to 27 m2/g.

The change in texture caused by the introduction of HB was also evident in the change in the CBET constant. This constant indicates the strength of the interaction between the adsorbed gas and the solid surface and is directly related to the heat of adsorption; a stronger adsorbent–adsorbate interaction results in a larger CBET value. In the case of the B–ChM–HB, the CBET value was slightly above 40, which represents the practical lower limit for the routine application of nitrogen physisorption at 77 K for textural characterization. This value highlights the significant change in the texture of the B–ChM–HB compared to its precursors (B and B–ChM).

Finally, these textural changes are accompanied by a morphological change, resulting in a sea sponge-like surface (Figure 3c). The overall characterization of B, B–ChM, and B–ChM–HB confirmed that both HB and ChM were present in composites. Chitosan ChM was positioned at the surface of montmorillonite, while HB ions were mainly located in the interlayer space of montmorillonite, as well as at its surface. As a result, it is reasonable to anticipate that B–ChM–HB will exhibit distinct adsorption behavior in contrast to B and B–ChM.

3.2. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties

3.2.1. Antioxidant Activity

The in vitro determination of the antioxidant properties of B–ChM and B–ChM–HB was investigated, as a special challenge, in assessing positive effects in the prevention of oxidative stress in the organism. In human and animal nutrition, antioxidants are crucial for maintaining health and reducing disease incidence [39]. In the pharmaceutical and nutraceutical industry, antioxidants are the current hype. They are intended as prophylactic and therapeutic agents, commercialized as anti-aging wonder compounds [39,40]. Furthermore, antioxidants improve productivity in animals by combating oxidative stress and ultimately contributing to the reduction in antibiotic use in livestock [41].

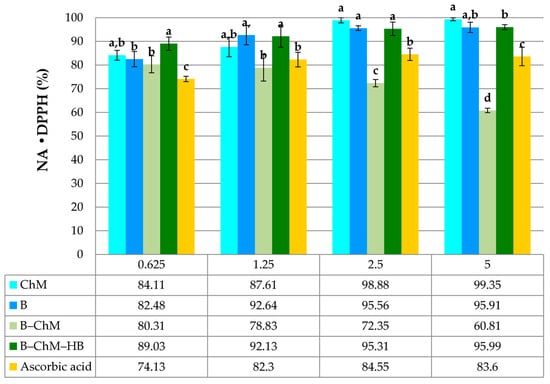

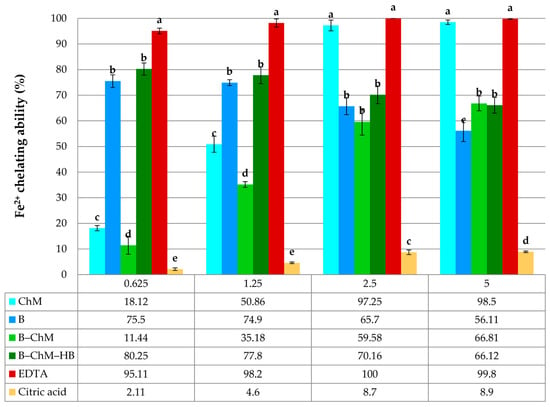

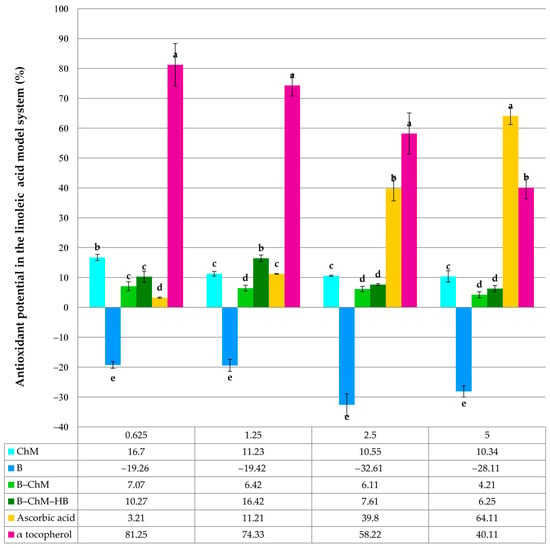

Three complementary experiments were performed to gain a comprehensive understanding of the antioxidant activities of the B, ChM, B–ChM, and B–ChM–HB, and the findings are shown in Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7.

Figure 5.

Neutralization ability on •DPPH radicals (NA•DPPH) of B, ChM, B–ChM, and B–ChM–HB. Data represent means ± standard deviation (n = 3). All samples were analyzed in the concentration range of 0.625–5.0 mg/mL. Within the same concentration, means followed by different letters are significantly different at p ≤ 0.05.

Figure 6.

Fe2+ chelating ability of B, ChM, B–ChM, and B–ChM–HB. Each value is expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). All samples were analyzed in the concentration range of 0.625–5.0 mg/mL. Within the same concentration, means followed by different letters are significantly different at p ≤ 0.05.

Figure 7.

Inhibition of lipid peroxidation of B, ChM, B–ChM, and B–ChM–HB in the model system of linoleic acid. Each value is expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). All samples were analyzed in the concentration range of 0.625–5.0 mg/mL. Within the same concentration, means followed by different letters are significantly different at p ≤ 0.05.

Neutralization Ability of •DPPH

The •DPPH assay can be used to determine the neutralizing/scavenging capacity of complex samples in which HAT, ET, and PCET mechanisms may play different roles in different proportions, depending on the corresponding reaction conditions (such as pH and solvent) [40]. Each sample’s percentage of •DPPH inhibition was found to be high (Figure 5). ChM and B showed activity over 80% in the tested concentration range. At the highest concentrations (2.5–5.0 mg/mL), the •DPPH neutralization abilities of ChM and B were 98.88–99.35% and 95.56–95.91%. For B–ChM and B–ChM–HB, a higher activity was observed for B–ChM–HB, with values over 90% in the tested concentration range (Figure 5). Moreover, B–ChM–HB showed a significantly higher •DPPH scavenging ability (p ≤ 0.05) than ascorbic acid. The neutralization ability of B–ChM was between 60% and 80% at 0.625–5.0 mg/mL. Contrary to our findings, Sun et al. [42] reported that the CTS/bentonite composite film showed less than 10% •DPPH neutralizing potential. The difference in the comparison of neutralization abilities can be explained by the different reactivity of the examined composite samples with selected radical species [43]. The •DPPH test specifically recognizes functional groups such as –OH and –NH3+ [43]. We assumed that the presence of glucans and their –OH groups in B–ChM could further lead to a higher potential for •DPPH neutralization. The ability of the polysaccharide molecules to neutralize/scavenge free radicals may be conditioned by the presence of hydrogen from certain monosaccharide units and the type of their binding in side branches of the main chain [44]. In addition, Kishk et al. [45] reported that the hydroxyl radical (•OH) scavenging mechanism of polysaccharides was perhaps similar to that of phenol compounds by hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) reactions. However, the HAT reaction is more likely to occur in the neutral polysaccharides, while the electron transfer (ET) mechanism usually occurs in the acidic polysaccharides. Additionally, the procedure for •DPPH neutralization ability in the research of Sun et al. [42] was different from the procedure used in our investigation. They used methanol, a polar protic solvent, for •DPPH dissolution. In the current investigation, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), a polar aprotic solvent, was applied. We speculate that these solvents may differently affect the availability of functional groups of CTS–bentonite composites, which affects the free radical neutralizing potential.

Likewise, it can be speculated that while the chemical neutralization/scavenging is the main focus of the DPPH assay, the adsorption of the •DPPH and its reaction products with the surface of a composite material is also a possibility. This is not the primary mechanism, and it is dependent on the bentonite/CTS composite properties and the experimental conditions [30,46,47]. This has already been observed in similar bentonite/CTS composite systems with other organic compounds, pollutants, and dyes [48,49]. In this study, it can be hypothesized that the adsorption of •DPPH to B–ChM–HB may occur through various physical and chemical interactions, including electrostatic attraction, van der Waals forces, and potentially chemisorption [50,51,52]. The specific mechanisms depend on the composite’s properties and the solution’s pH; thus, for B–ChM–HB, the presence of active functional groups of ChM, enhanced by the presence of HB, provided the binding sites for organic molecules like •DPPH, leading to its adsorption onto this composite [51]. Stronger chemical bonds, such as inner-sphere complexation, could also contribute to the adsorption, especially if the bentonite surface is chemically modified [53]. Additionally, the microstructure and surface chemistry of the bentonite–CTS composite, including the degree of intercalation and inter-layer spaces, influence the availability of adsorption sites [54,55]. Bentonite may act as a filler, enhancing the dispersion of the CTS and creating a more efficient matrix for trapping radicals [56].

Capability to Chelate Fe2+

The chelating ability measures the potential of B, ChM, B–ChM, and B–ChM–HB to bind Fe2+ and form complex structures. Iron is an essential micronutrient that is problematic for biological systems, since it becomes toxic at higher concentrations, as it generates free radicals by interconverting between ferrous (Fe2+) and ferric (Fe3+) forms [57]. Iron chelators mobilize tissue iron by forming soluble stable complexes that are then excreted from the body [58]. When testing the chelating ability, all samples showed different patterns at 0.625–5.0 mg/mL (Figure 6). The highest Fe2+ chelating ability was observed for ChM at a concentration of 2.5–5 mg/mL, which was 97.25–98.50%, and there was no significant difference (p ≤ 0.05) compared to the chelating ability of EDTA, which is an excellent chelating agent. Opposite to this finding, B exhibited the highest activity at the lower concentrations (75.5–74.9% at the 0.625–1.25 mg/mL). There was significant difference between B–ChM and B–ChM–HB at the 0.625–1.25 mg/mL (p ≤ 0.05). At a concentration of 0.625 mg/mL, B–ChM–HB reached 80.25% of activity compared to the B–ChM, which exerted only 11.44% of chelating ability on Fe2+. At the higher concentration (5.0 mg/mL), no difference was observed between B–ChM and B–ChM–HB. They showed a chelating ability between 66.81and 66.12%.

Ability to Inhibit Lipid Peroxidation

Considering that linoleic acid is among the most prevalent polyunsaturated fatty acids in cell membranes [59], the total antioxidant activity in the protection of LPx in the linoleic acid model system was studied. LPx is a key contributor to cellular damage and cell death [60]. The tested B, ChM, B–ChM, and B–ChM–HB did not show significant activity in the inhibition of LPx (Figure 7). It is important to mention that B in the concentration range 0.625–5.0 mg/mL showed a certain negative activity, i.e., to promote/induce LPx. At a concentration of 0.625–1.25 mg/mL, the recorded activity of B was ~20%, while at concentrations of 2.5–5.0 mg/mL, the activity was between 32.61 and 28.11%. It is important to note that both B–ChM and B–ChM–HB did not exhibit the potential to induce LPx at the tested concentrations (Figure 7). Ascorbic acid and α tocopherol showed significant potential in preventing LPx. Opposite to ascorbic acid, the antioxidant capacity of α tocopherol decreased intensively with the increasing concentration. Although sample B showed significant potential in •DPPH scavenging (Figure 5) and Fe2+ chelation (Figure 6), in the linoleic acid model system, it showed significant potential in inducing •ROO formation (~30%) and linoleic acid degradation (Figure 7). Bentonite, especially when exposed to light/oxidants, may generate radicals like •OH through water radiolysis and by activating structural iron (Fe2+) in montmorillonite, creating reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS can drive the transformation of organic molecules such as linoleic acid and catalytic reactions, acting as a surface-activated catalyst for the generation of radicals [61]. Contrary to this finding, it was found that B–ChM and B–ChM–HB did not show induction of LPx in the linoleic acid model system, indicating their safe oral administration. We hypothesize that the sequential modification of bentonite with ChM and HB enhances the antioxidant activity by creating a multilayered amphiphilic material. ChM adds reactive amine/hydroxyl groups for radical scavenging and biocompatibility, while HB increases the surface area and hydrophobicity and creates new catalytic sites, ultimately improving radical scavenging and redox potential beyond simple bentonite. It is important to note that the long alkyl chain of HB (C16) makes the surface hydrophobic, while its positive charge attracts anionic species. In addition, the quaternary ammonium groups of HB can catalyze reactions, potentially boosting antioxidant pathways, and the structured environment helps stabilize radical-scavenging moieties. The amphiphilic structure (hydrophilic chitosan/inorganic bentonite core + hydrophobic HB shell) allows it to interact with both aqueous and organic phases, improving the overall antioxidant performance in diverse environments [62,63,64]. Moreover, the intercalation of HB and ChM increases the basal spacing (d-spacing) of bentonite. This expansion facilitates better accessibility of internal active sites for radicals. The modification transforms the smooth surface of the clay into a more porous or rougher structure, increasing the effective surface area for interaction [65,66].

3.2.2. Antifungal Activity

During the past years, researchers have reported the antimicrobial activity of CTS and its derivatives on yeasts, molds, viruses, algae, and bacteria. Stronger antifungal activity compared to antibacterial has been proven. The activity of CTS depends on several factors that include the physicochemical properties of CTS, the microorganism, and environmental factors. The chitosan ChM from A. bisporus used in this research might have strong antifungal activity due to a high degree of deacetylation and content of bioactive β-glucans, which are not present/or are present in low amounts in commercial CTSs obtained from crustaceans. Additionally, it is known that pure CTS shows different activity compared to its derivatives, oligomers, and complexes, and the antimicrobial activity is expressed only in an acidic environment [67].

The antifungal activity of the B, ChM, B–ChM, and B–ChM–HB was evaluated regarding the potential to reduce viable fungal (C. albicans and A. flavus) counts, and the obtained results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Antifungal activity of B, ChM, B–ChM, and B–ChM–HB against C. albicans and A. flavus.

It was determined that ChM and B–ChM–HB in concentrations of 10 mg/mL and 100 mg/mL, respectively, eradicated the tested mold and yeast strains to below the limit of detection within 2 days of treatment in vitro. A CFU reduction of ≥3 log10 is defined as fungicidal activity [68]. In contrast, B and B–ChM did not inhibit yeast growth compared to the inoculum; moreover, stimulation of yeast growth was observed. In the presence of 100 mg/mL of B, A. flavus showed a 1.32-log10 reduction in CFU compared to the control, while approximately twice higher inhibition was observed using the same concentration of B–ChM. Opposite to the B and B–ChM, B–ChM–HB exhibited promising antimicrobial activity against mold C. albicans and yeast A. Flavus, eradicating both strains below the limit of detection.

Parolo et al. [69] found that pure montmorillonite does not possess antibacterial activity. Montmorillonite treated with Ag+ in their research showed a smaller inhibition zone against tested bacteria compared with AgNO3, probably because Ag+ was strongly bound to the clay surface, or it diffused less from the modified mineral surface. After the formation of complexes using Ag+, HB, tetracycline, and minocycline, pronounced antibacterial activity was achieved. In the review papers of Rabea et al. [70] and Qin et al. [67], the fungicidal activity of CTS against various filamentous molds and yeasts such as Fusarium oxysporum, Rhizopus stolonifer, Penicillium digitatum, and C. albicans was described. Reported minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were in the range from 10 to 2500 µg/mL. In another study [71], in a laboratory experiment, 0.1–5 mg/mL of CTS in agar inhibited A. niger, while A. parasiticus and aflatoxin synthesis were not inhibited with a CTS concentration below 2 mg/mL. CTS derivatives, N-carboxymethyl-CTS, reduced aflatoxin production by more than 90% in A. flavus and A. parasiticus strains, while the mold growth was reduced by about 50% [70]. It was assumed that the electrostatic interaction of protonated amino groups of the CTS on the cell surface of the microorganism was crucial for the antimicrobial activity, leading to the destruction of the cell surface.

The antimicrobial activity of bentonite has been studied for many years [19,72]. In the research conducted by Khan et al. [73], the significant antifungal activity of bentonite concentration up to 10 mg/mL in DMSO was determined on A. niger and R. oryzae through the deformation and degradation of the cell membrane. Bentonite from the Sabon Kaura region, which was composed of montmorillonite, kaolin, quartz, chlorite, clinochlore, and illite, showed significant antifungal activity on A. niger and C. albicans, which was comparable with the positive control ketoconazole (50 µg/mL), in concentrations of 125–500 µg/mL [74]. In the research conducted by Cabuk et al. [19] and Parolo et al. [69], natural clays did not show antimicrobial activity due to the established negative charge of the clay. These results are in accordance with the results obtained in this research. It is assumed that the composition of the clay influences the antimicrobial activity. By forming a CTS–organobentonite composite (10% wt./V concentration), samples with low CTS content due to negative potential still did not show activity, while when increasing the CTS content, the antifungal activity increased, as a consequence of increased positive ζ-potential values. Studies indicated that derivatives and complexes based on CTS, such as carboxymethyl CTS, benzenesulfonic CTS, CTS quaternary ammonium salt, hydroxypropyl CTS, etc., can overcome the disadvantages of using pure components [75]. Similar results were obtained by applying 10 mg/mL of bentonite–CTS nanoclay to the spore suspension of F. eumartii, where the complex affected cell permeabilization of the microorganism, compared to 10 mg/mL of bentonite and 1 mg/mL of CTS [76]. The reduced activity of the B–ChM in our work may be the result of a low concentration of active ChM in the composite, sedimentation of the composite, or the near-neutral pH of the environment in which the test was performed to avoid the influence of the low pH on microbial growth. Stronger antimicrobial activity of sulfonated CTS [77] and quaternized N-substituted carboxymethyl CTS [78] was found, compared to water-soluble CTS, where the inhibitory concentrations of complexes were twice as low.

The results of the antioxidant and antifungal activities showed that regarding the neutralization ability on •DPPH, B–ChM–HB showed a very high potential (89.03%–95.99%) in the concentration range of 0.625–5.0 mg/mL, the highest ferrous ion chelating ability (80.25%) at concentration of 0.625 mg/mL, and did not induce lipid peroxidation (LPx) in the linoleic acid model system. These results highlighted the potential of B–ChM–HB in supporting digestive tract homeostasis and maintaining intestinal barrier integrity. As is well known, antioxidants are key to gastrointestinal health. They reduce oxidative stress, which can damage intestinal cells and lead to inflammation and disease [79,80,81]. Antioxidants also support a healthy gut microbiome by promoting beneficial bacteria, preserving the integrity of the intestinal mucosa, and protecting against intestinal damage [82]. This protection may help prevent chronic conditions associated with gut dysfunction, such as inflammatory bowel disease and certain cancers [79]. Furthermore, as mentioned above, safety testing of B–ChM–HB in the linoleic acid model system confirmed that the composite did not affect LPx. LPx is a chain reaction initiated by free radicals that attacks and breaks down the lipid membranes of cells and organelles. This process can impair cell function, trigger cell death pathways like ferroptosis, and contribute to diseases such as cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and cardiovascular diseases [60]. In addition, B–ChM–HB exhibited promising antimicrobial activity, eradicating mold C. albicans and yeast A. flavus strains below the limit of detection.

3.3. Adsorption of Zearalenone onto B–ChM and B–ChM–HB Composites

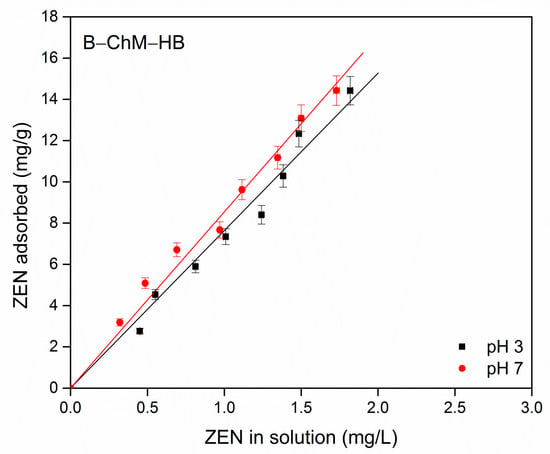

It is well known that natural bentonite (montmorillonite) has little or no affinity for the adsorption of ZEN [10,83]. Preliminary results on ZEN adsorption by composites (C0 ZEN = 4.0 mg/L; Csusp =1 g/L) showed that its adsorption on the B–ChM was low—7.3% at pH 3 and 9.9% at pH 7. However, after modification of B–ChM with HB ions, the adsorption of ZEN significantly increased to 91.8% at pH 3 and 93.7% at pH 7. The zearalenone adsorption versus adsorbent mass for B–ChM–HB at the same initial mycotoxin concentration is presented in Table 5. The adsorption of ZEN by B–ChM–HB increased with the increasing amount of adsorbent in suspension at both pH values. At the lowest amount of adsorbent, the adsorption of ZEN was slightly higher at pH 7 (68.7%) than at pH 3 (59.0%).

Table 5.

Adsorption of ZEN by B–ChM and B–ChM–HB at pH 3 and pH 7.

Zearalenone adsorption by B–ChM–HB was further studied by the determination of adsorption isotherms in buffer solution at pH 3 and 7. The results are presented in Figure 8. Usually, the isotherms are obtained by plotting the amounts of solute adsorbed per weight unit of adsorbent (mg/g) after equilibrium against the concentrations of the solute in the solution (mg/L). As can be seen from Figure 8, B–ChM–HB showed increased adsorption of ZEN with an increase in its initial concentration, and a linear adsorption isotherm was obtained at both pH values, due to the hydrophobic phase created by the adsorption of HB ions in the interlayer space and at the surface of montmorillonite. The experimental adsorption data were fitted to a Linear isotherm model (Equation (2)):

where Cads is the adsorbed ZEN amount per unit mass of the B–ChM–HB (mg/g), Ceq is the ZEN equilibrium concentration (mg/L), and Kd is the linear adsorption (partition) coefficient (L/g). A good fit of the ZEN adsorption data was obtained with a linear isotherm model, with the coefficient of determination R2 = 0.980 at pH 3 and R2 = 0.986 at pH 7. The calculated partition coefficient (Kd) from the slope of the linear curve was 7.6 L/g at pH 3 and 8.5 L/g at pH 7. Zearalenone is a hydrophobic molecule that contains two phenolic hydroxyl groups. Based on the estimated dissociation constant (pKa1 = 7.62), it was suggested that, at pH 3, ZEN in solution mainly exists in neutral form, while at pH 7, it is partly in anionic form (as phenolate anion) [83]. The obtained results indicated that although B–ChM–HB contained both ChM and HB, long-chain organic cations are dominant sites for ZEN adsorption. The linear adsorption isotherm suggested that the partitioning (van der Waals interactions) between hydrophobic long chains of HB ions and hydrophobic part of ZEN is a dominant process relevant for ZEN adsorption by B–ChM–HB. The maximum ZEN adsorbed amount under applied experimental conditions was 14.4 mg/g at both pH values, indicating that ZEN adsorption was practically independent of its form in buffer solution. This means that although there is some phenolate anion in the buffer solution at pH 7 (~20%) that can interact with positive “heads” of HB or with ChM, these interactions contributed less than the hydrophobic interactions to the overall ZEN adsorption process by B–ChM–HB. The results from this study were similar to the results of Lemke et al. [83] and Wang et al. [84]. Namely, Lemke et al. [83] reported, for the first time, that modified montmorillonite with HB and cetylpyridinium (CP) improved ZEN adsorption, due to the increased hydrophobicity at the surface and expanded the interlayer space of montmorillonite. They stated that adsorption of ZEN increased with increasing amounts of both organic phases in montmorillonites (from 25 to 150% CEC of montmorillonite). ZEN binding to CP and HB exchanged montmorillonites at neutral pH and various exchange levels (CEC) followed a linear increase in adsorption with an increase in the solution concentration, with all organomontmorillonites with the amount of each surfactant at 100% CEC or less. This suggested that ZEN was partitioned onto the organomontmorillonites, most likely in the interlayer space due to hydrophobic association with the adsorbed surfactant. For montmorillonite exchanged with CP at an amount of 150% CEC, the adsorption of ZEN occurred via additional electrostatic interactions in combination with partitioning. Wang et al. [84] studied the adsorption of AFB1 and ZEN onto montmorillonite modified with different amounts (50, 75, 100, and 150% CEC of montmorillonite) of dodecyl dimethyl betaine (BS-12) and lauramidopropyl betaine (LAB-35) BS-12/montmorillonites and LAB-35/montmorillonites. They reported that organomontmorillonites showed significant improvements in the efficiency to adsorb both AFB1 and ZEN. Linear adsorption isotherms were obtained for the adsorption of ZEN by both types of organomontmorillonites. The hydrophobic properties of organomontmorillonites played the most significant role in the adsorption of ZEN. The authors stated that the LAB-35/montmorillonites showed much higher ZEN adsorption capacities than BS-12/montmorillonites, due to the larger interlayer space, increased hydrophobicity, and higher organic carbon content. Hydrophobic interactions were also responsible for the adsorption of AFB1 onto BS-12/montmorillonites in combination with the ion–dipole interactions between the positively charged cations of BS-12/Mts, such as calcium and quaternary ammonium cations, and carbonyl groups of AFB1. Concerning the adsorption of AFB1 by LAB-35/montmorillonites, the extra amide group (−CONH) and propyl group (−CH2CH2CH2-) provided more sites for the adsorption of AFB1 through ion-dipole interaction and coordination as well. Wang et al. [10] reported that composites of montmorillonite with CTS prepared via the hydrothermal carbonization method at 180° and 250 °C enhanced the adsorption capacity for AFB1 and ZEN. Approximately twice higher values were achieved for AFB1 compared to montmorillonite, while a superior adsorption efficiency was reported for ZEN (10 mg/g).

Cads = KdCeq,

Figure 8.

Zearalenone adsorption by B–ChM–HB, at pH 3 and 7.

As previously mentioned, the literature data on composites of montmorillonite with CTS and surfactants described them as effective adsorbents for the removal of low-polar organic pollutants (phenol) or dyes and heavy metals [11,16]. El-Dib et al. [16] modified bentonite with chitosan (CIB) and additionally with HB (mCIB) and tested them for color removal and COD reduction in distilleries wastewater. The authors stated that, in CIB, hydroxyl groups at the edges of montmorillonite interacted with CTS through a hydrogen bond between the amino groups of CTS and the hydroxyl groups of montmorillonite. The composite mCIB contained both –NH2 and –OH groups that served as binding sites. Moreover, the existence of hydrophobic alkyl chains between the montmorillonite layers can create several active sites, which supported their results that mCIB was the most efficient adsorbent for organic pollutants. Zhu et al. [11] modified montmorillonite with both HB and CTS and investigated the adsorption of phenol, cadmium, and dyes CR and CV from water solution onto the obtained adsorbents. The authors reported that organic phases created by the adsorption of HB and CTS were relevant for the removal of phenol through hydrophobic interactions. The linear adsorption isotherms for phenol adsorption by composites confirmed partitioning as the dominant mechanism for the uptake of this pollutant. The adsorption of dyes, CR and CV, and heavy metals was well described with nonlinear adsorption isotherms. They stated that, although the adsorption of cadmium was the highest at montmorillonite due to the cation exchange, the functional groups on montmorillonite modified with CTS (e.g., –OH, –NH2) also contributed to the high adsorption of Cd2+ onto this composite. The electrostatic interactions between positively charged surfaces of montmorillonite with CTS, along with the hydrophobic interactions between composite and CR, contributed to the effective adsorption of this anionic dye. For cationic dye CV, the highest adsorption was observed for montmorillonite and montmorillonite modified with HB. The literature data and the data obtained in this study suggest that linear isotherms commonly describe the partitioning process that includes hydrophobic interactions between low-polar hydrophobic parts of molecules, like ZEN or phenol(s), and hydrophobic surfaces of composites of montmorillonite with surfactant ions and/or CTS.

In general, the results from this study showed that with the simple modification of the natural bentonite with CTS isolated from mushroom (ChM) and subsequently with HB, it is possible to prepare composite material—B–ChM–HB—with promising antimicrobial and antioxidative properties. It was suggested that isolated ChM showed strong activity, possibly due to a high degree of deacetylation and content of bioactive β-glucans, which are not present or are present in low amounts in commercial CTSs obtained from crustaceans. The physicochemical characterization of B–ChM–HB confirmed the presence of both ChM and HB in the composite. Chitosan was mainly located at the external surface of B–ChM–HB, while HB was primarily adsorbed in its interlayer space but also at the surface. The results for ZEN adsorption by B–ChM–HB suggested that although ChM was present, the primarily active sites created with the presence of HB were relevant for toxin adsorption.

4. Conclusions

This study describes a new simple procedure for the preparation of a multifunctional material with antibacterial and antifungal properties for the effective adsorption of mycotoxin zearalenone. The procedure includes two steps. In the first step, the natural bentonite (montmorillonite) was modified with chitosan isolated from edible mushrooms Agaricus bisporus—ChM (sample B–ChM), while in the second step, B–ChM composite was additionally modified with HB (B–ChM–HB composite).

Composite B–ChM–HB showed promising antioxidant potential. B–ChM–HB did not induce lipid peroxidation in the linoleic acid model system, indicating its safe oral administration. It was also shown to have remarkably high neutralizing potential on •DPPH and good chelating ability on Fe2+. The antimicrobial test showed that B–ChM–HB demonstrated the strongest activity against C. albicans and A. flavus, compared to B and B–ChM. B–ChM–HB activity was comparable with fungicide amphotericin B, since both eradicated tested strains were below the limit of detection. Zearalenone adsorption studies showed that its adsorption by B–ChM was low, while significantly higher adsorption was achieved with B–ChM–HB. The ZEN adsorption equilibrium data were well fitted by a linear isotherm model, indicating that a partitioning process was dominant for ZEN adsorption by B–ChM–HB. The composite B–ChM–HB that was the subject of this study contains non-toxic ChM and HB, has promising antioxidative and antifungal properties, and possesses high efficiency in the adsorption of mycotoxin ZEN, making it suitable as a material for feed and food protection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D., D.K., M.P., M.K. and J.K.; methodology, A.D., M.P., M.K. and J.K.; formal analysis, M.M., M.O. (Milica Ožegović), M.O. (Milena Obradović), M.P., M.K. and J.K.; investigation, M.M., M.O. (Milica Ožegović), M.O. (Milena Obradović), M.P., M.K. and J.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D., D.K., M.P., M.K. and J.K.; writing—review and editing, A.D., D.K., M.P., M.K. and J.K.; visualization, M.M., M.O. (Milica Ožegović), M.O. (Milena Obradović), M.P., M.K. and J.K.; supervision, A.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Science Fund of the Republic of Serbia (Grant No. 7748088, Project: Composite clays as advanced materials in animal nutrition and biomedicine—AniNutBiomedCLAYs) and by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia (Contract No. 451-03-136/2025-03/200026).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge ZeoWorld LLC and Contractor LLC (Serbia) for kindly providing the bentonite sample used in this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, G.; Lian, C.; Xi, Y.; Sun, Z.; Zheng, S. Evaluation of Nonionic Surfactant Modified Montmorillonite as Mycotoxins Adsorbent for Aflatoxin B1 and Zearalenone. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 518, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Han, X.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Meng, J.; Zhang, H.; Liang, J. Removal of Aflatoxin B1 and Zearalenone by Clay Mineral Materials: In the Animal Industry and Environment. Appl. Clay Sci. 2022, 228, 106614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ropejko, K.; Twarużek, M. Zearalenone and Its Metabolites-General Overview, Occurrence, and Toxicity. Toxins 2021, 13, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.L.; Yang, C.E.; Du, J.; He, J.B.; Zhang, W.N. Adsorption Behaviors of Zearalenone in Corn Oil by Montmorillonite Modified with Quaternary Ammonium Salts. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 644, 158744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, T.A.; Ledoux, D.R.; Rottinghaus, G.E.; Shaw, D.P.; Daković, A.; Marković, M. The Efficacy of Raw and Concentrated Bentonite Clay in Reducing the Toxic Effects of Aflatoxin in Broiler Chicks. Poult. Sci. 2017, 96, 1651–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marković, M.; Daković, A.; Rottinghaus, G.; Stojanović, M.; Dondur, V.; Kragović, M.; Gulišija, Z. Adsorpcija Aflatoksina B1 Na Prirodnim Alumosilikatima—Koncentratu Montmorilonita i Zeolitu. Hem. Ind. 2016, 70, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Hearon, S.E.; Phillips, T.D. A High Capacity Bentonite Clay for the Sorption of Aflatoxins. Food Addit. Contam.-Part A Chem. Anal. Control. Expo. Risk Assess. 2020, 37, 332–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.H.; Cai, W.K.; Khatoon, N.; Yu, W.H.; Zhou, C.H. On How Montmorillonite as an Ingredient in Animal Feed Functions. Appl. Clay Sci. 2021, 202, 105963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yang, M.; Shi, Y.; Sun, L.; Zheng, H.; Wu, M.; Gao, G.; Ma, T.; Li, G. Multifunctional Bacterial Cellulose-Bentonite@polyethylenimine Composite Membranes for Enhanced Water Treatment: Sustainable Dyes and Metal Ions Adsorption and Antibacterial Properties. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 477, 135267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Xu, J.; Sun, Z.; Zheng, S. Surface Functionalization of Montmorillonite with Chitosan and the Role of Surface Properties on Its Adsorptive Performance: A Comparative Study on Mycotoxins Adsorption. Langmuir 2020, 36, 2601–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wang, L.; Xu, Y. Chitosan and Surfactant Co-Modified Montmorillonite: A Multifunctional Adsorbent for Contaminant Removal. Appl. Clay Sci. 2017, 146, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hu, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Ning, P.; Tian, S. Adsorption Behavior of Phenol by Reversible Surfactant-Modified Montmorillonite: Mechanism, Thermodynamics, and Regeneration. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 334, 1214–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Miao, Y.; Sun, Z.; Zheng, S. Simultaneous Adsorption of Aflatoxin B1 and Zearalenone by Mono- and Di-Alkyl Cationic Surfactants Modified Montmorillonites. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 511, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T. Chitosan and Its Use in Design of Insulin Delivery System. Recent Pat. Drug Deliv. Formul. 2009, 3, 8–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EL Kaim Billah, R.; Zaghloul, A.; Bahsis, L.; Oladoja, N.A.; Azoubi, Z.; Taoufyk, A.; Majdoubi, H.; Algethami, J.S.; Soufiane, A.; López-Maldonado, E.A.; et al. Multifunctional Biocomposites Based on Cross-Linked Shrimp Waste-Derived Chitosan Modified Zn2+@Calcium Apatite for the Removal of Methyl Orange and Antibacterial Activity. Mater. Today Sustain. 2024, 25, 100660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Dib, F.I.; Tawfik, F.M.; Eshaq, G.; Hefni, H.H.H.; ElMetwally, A.E. Remediation of Distilleries Wastewater Using Chitosan Immobilized Bentonite and Bentonite Based Organoclays. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 86, 750–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krajišnik, D.; Uskoković-Marković, S.; Daković, A. Chitosan–Clay Mineral Nanocomposites with Antibacterial Activity for Biomedical Application: Advantages and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulze-Makuch, D.; Pillai, S.D.; Guan, H.; Bowman, R.S.; Couroux, E.; Hielscher, F.; Totten, J.; Espinosa, I.Y.; Kretzschmar, T. Surfactant-modified Zeolite Can Protect Drinking Water Wells from Viruses and Bacteria. Eos, Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 2002, 83, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabuk, M.; Alan, Y.; Unal, H.I. Enhanced Electrokinetic Properties and Antimicrobial Activities of Biodegradable Chitosan/Organo-Bentonite Composites. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 161, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daković, A.; Marković, M.; Ožegović, M.; Rottinghaus, G.E.; Obradović, M.; Krajišnik, D.; Smiljanić, D.; Bish, D.L.; Krstić, J. The effects of bentonite characteristics and buffersolution composition on the adsorption of aflatoxin B1. Clay Clay Miner. 2026; accepted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Pantić, M.; Kozarski, M.; Lazić, V.; Todorov, J.; Todorović, N.; Nikšić, M.; Daković, A. Chitosan from Lentinus Edodes Fruiting Bodies: Extraction, Antioxidative and Antibacterial Activity. In Proceedings of the the 12th International Medicinal Mushroom Conference, Bari, Italy, 24–27 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rouquerol, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K. Adsorption by Powders and Porous Solids: Principles, Methodology and Applications; Academic Press: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rouquerol, J.; Llewellyn, P.; Rouquerol, F. Is the BET Equation Applicable to Microporous Adsorbents? In Studies in Surface Science and Catalysis; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 160, pp. 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubinin, M.M. Physical Adsorption of Gases and Vapors in Micropores. In Progress in Surface and Membrane Science; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1975; pp. 1–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozarski, M.; Klaus, A.; Niksic, M.; Jakovljevic, D.; Helsper, J.P.F.G.; Van Griensven, L.J.L.D. Antioxidative and Immunomodulating Activities of Polysaccharide Extracts of the Medicinal Mushrooms Agaricus Bisporus, Agaricus Brasiliensis, Ganoderma Lucidum and Phellinus Linteus. Food Chem. 2011, 129, 1667–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.; Johnson, S.; Lyons, A.; Boothby, C.; Jones, J.P.E. Kaolinic Clays with Antimicrobial Activity. US Patent No. WO/2018/144739, 1 February 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Petrikkou, E.; Rodríguez-Tudela, J.L.; Cuenca-Estrella, M.; Gómez, A.; Molleja, A.; Mellado, E. Inoculum Standardization for Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Filamentous Fungi Pathogenic for Humans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 1345–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salević, A.; Stojanović, D.; Lević, S.; Pantić, M.; Ðordević, V.; Pešić, R.; Bugarski, B.; Pavlović, V.; Uskoković, P.; Nedović, V. The Structuring of Sage (Salvia officinalis L.) Extract-Incorporating Edible Zein-Based Materials with Antioxidant and Antibacterial Functionality by Solvent Casting versus Electrospinning. Foods 2022, 11, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabuk, M.; Yavuz, M.; Unal, H.I.; Erol, O. Synthesis, Characterization and Electrorheological Properties of Biodegradable Chitosan/Bentonite Composites. Clay Miner. 2013, 48, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obradović, M.; Daković, A.; Smiljanić, D.; Marković, M.; Ožegović, M.; Krstić, J.; Vuković, N.; Milojević-Rakić, M. Bentonite Modified with Surfactants—Efficient Adsorbents for the Removal of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. Processes 2024, 12, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonczek, J.L.; Harris, W.G.; Nkedi-Kizza, P. Monolayer to Bilayer Transitional Arrangements of Hexadecyltrimethylammonium Cations on Na-Montmorillonite. Clays Clay Miner. 2002, 50, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goo, J.Y.; Kim, B.J.; Kwon, J.S.; Jo, H.Y. Bentonite Alteration and Retention of Cesium and Iodide Ions by Ca-Bentonite in Alkaline and Saline Solutions. Appl. Clay Sci. 2023, 245, 107141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolters, F.; Emmerich, K. Thermal Reactions of Smectites-Relation of Dehydroxylation Temperature to Octahedral Structure. Thermochim. Acta 2007, 462, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, M.U.; Manan, A.; Uzair, M.; Khan, A.S.; Ullah, A.; Ahmad, A.S.; Wazir, A.H.; Qazi, I.; Khan, M.A. Physicochemical Characterization of Pakistani Clay for Adsorption of Methylene Blue: Kinetic, Isotherm and Thermodynamic Study. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2021, 269, 124722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yariv, S.; Borisover, M.; Lapides, I. Few Introducing Comments on the Thermal Analysis of Organoclays. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2011, 105, 897–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, A.; Viante, M.F.; Pochapski, D.J.; Downs, A.J.; Almeida, C.A.P. Enhanced Removal of P-Nitrophenol from Aqueous Media by Montmorillonite Clay Modified with a Cationic Surfactant. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 355, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A.V.; Olivier, J.P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K.S.W. Physisorption of Gases, with Special Reference to the Evaluation of Surface Area and Pore Size Distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groen, J.C.; Peffer, L.A.A.; Pérez-Ramírez, J. Pore Size Determination in Modified Micro- and Mesoporous Materials. Pitfalls and Limitations in Gas Adsorption Data Analysis. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2003, 60, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogerakou, T.; Antoniadou, M. The Role of Dietary Antioxidants, Food Supplements and Functional Foods for Energy Enhancement in Healthcare Professionals. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddeeg, A.; AlKehayez, N.M.; Abu-Hiamed, H.A.; Al-Sanea, E.A.; AL-Farga, A.M. Mode of Action and Determination of Antioxidant Activity in the Dietary Sources: An Overview. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 1633–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, L.; Dell’Anno, M. Novel Antioxidants for Animal Nutrition. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Liu, N.; Ni, S.; Bian, H.; Fu, Y.; Chen, X. Poplar Hot Water Extract Enhances Barrier and Antioxidant Properties of Chitosan/Bentonite Composite Film for Packaging Applications. Polymers 2019, 11, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platzer, M.; Kiese, S.; Herfellner, T.; Schweiggert-Weisz, U.; Miesbauer, O.; Eisner, P. Common Trends and Differences in Antioxidant Activity Analysis of Phenolic Substances Using Single Electron Transfer Based Assays. Molecules 2021, 26, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiapali, E.; Whaley, S.; Kalbfleisch, J.; Ensley, H.E.; Browder, I.W.; Williams, D.L. Glucans Exhibit Weak Antioxidant Activity, but Stimulate Macrophage Free Radical Activity. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2001, 30, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishk, Y.F.M.; Al-Sayed, H.M.A. Free-Radical Scavenging and Antioxidative Activities of Some Polysaccharides in Emulsions. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 40, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maged, A.; Kharbish, S.; Ismael, I.S.; Bhatnagar, A. Characterization of Activated Bentonite Clay Mineral and the Mechanisms Underlying Its Sorption for Ciprofloxacin from Aqueous Solution. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 32980–32997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ewis, D.; Ba-Abbad, M.M.; Benamor, A.; El-Naas, M.H. Adsorption of Organic Water Pollutants by Clays and Clay Minerals Composites: A Comprehensive Review. Appl. Clay Sci. 2022, 229, 106686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotto, G.L.; Rodrigues, F.K.; Tanabe, E.H.; Fröhlich, R.; Bertuol, D.A.; Martins, T.R.; Foletto, E.L. Development of Chitosan/Bentonite Hybrid Composite to Remove Hazardous Anionic and Cationic Dyes from Colored Effluents. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 3230–3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dambuza, A.; Mokolokolo, P.P.; Makhatha, M.E.; Sibeko, M.A. Chitosan-Based Materials as Effective Materials to Remove Pollutants. Polymers 2025, 17, 2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Alves, D.C.; Healy, B.; Pinto, L.A.d.A.; Cadaval, T.R.S.; Breslin, C.B. Recent Developments in Chitosan-Based Adsorbents for the Removal of Pollutants from Aqueous Environments. Molecules 2021, 26, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, C.; Quraishi, M.A.; Rhee, K.Y. Hydrophilicity and Hydrophobicity Consideration of Organic Surfactant Compounds: Effect of Alkyl Chain Length on Corrosion Protection. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 306, 102723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]