Abstract

The growing demand for critical elements vital to the energy transition highlights the need for sustainable secondary sources. Sedimentary phosphate mining generates waste rock known as spoil piles (SPs). These SPs retain valuable phosphate and other critical elements such as rare earth elements (REEs). This study examines the potential of recovering these elements from SPs. A comprehensive sampling strategy was implemented, and a 3D topographic model was generated using drone imagery data. The model revealed that these SPs cover an area estimated at 48,633,000 m2, with a total volume of approximately 419,612,367 m3. Chemical analyses using X-ray fluorescence and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry techniques indicated valuable phosphate content, with an overall concentration of 12.6% P2O5 and up to 20.7% P2O5 in the fine fraction (<1 mm). The concentrations of critical and strategic elements in the SPs were as follows: magnesium [1%–8%], REEs [67–267 ppm], uranium [48–173.5 ppm], strontium [312–1090 ppm], and vanadium [80–150 ppm]. Enrichment factors showed that these elements are highly concentrated in fine fractions, with values exceeding 60 for Y, 40 for Sr, and 780 for U in the +125/−160 µm fraction. A positive correlation was observed between these elements and phosphorus, except for magnesium. Automated mineralogy confirmed that the fine fraction (<1 mm) contains more than 50% carbonate-fluorapatite (CFA), alongside major gangue minerals such as carbonates and silicates. These findings demonstrate the potential for sustainable recovery of phosphate, magnesium, REEs, strontium, vanadium, and uranium from phosphate mining waste rock.

1. Introduction

Critical raw materials are a group of elements that are of paramount importance to modern societies. Their significance is growing rapidly due to their essential role in the energy transition and the production of cutting-edge green technologies, such as renewable energy systems, electric vehicles, and electronic devices. For instance, indium, gallium, germanium, and silicon are crucial for the production of solar panels. Similarly, niobium, cobalt, dysprosium, neodymium, praseodymium, and terbium are vital components in the manufacturing of wind turbines. Additionally, elements like lithium, cobalt, niobium, titanium, silicon, dysprosium, neodymium, praseodymium, and terbium are key for the development of electric vehicles [1,2,3]. These elements are deemed critical not merely due to their scarcity in the Earth’s crust, but rather for three fundamental reasons. First, their exceptional economic significance stems from their essential role in various high-value industries and technologies. Second, their geographically concentrated distribution presents a decisive challenge. For instance, over 65% of the global phosphate reserves are located in Morocco, creating substantial dependence and vulnerability for countries reliant on these resources. This geographic concentration poses considerable risks to supply chain security. Third, their substitution by alternative materials is severely constrained due to their unique physicochemical properties. Despite advancements in technological innovation, replicating the specific characteristics of these critical elements remains a formidable challenge [4,5,6]. In terms of the number of these elements, each country or economic group has its list of critical raw materials. The development of this list depends on the availability of mineral resources and the technologies they have developed. Generally, this list is regularly updated based on the needs arising from technological advancements and changes in supply chains. The European Union initially had 14 elements considered critical in 2010; this number increased to 20 in 2014, and according to the latest 2023 report, has risen further to 40 critical elements [2,7].

To meet this growing demand and ensure the supply of these elements, it is important to introduce secondary resources such as electronic waste and mining waste [8,9]. Recent studies have shown that mine waste contains high concentrations of certain elements considered critical for many countries and that mine waste can be a potential secondary source of these elements. This is due to the inefficiency of old recovery methods and the fact that, in these mines, the focus was mainly on major elements, neglecting the associated ones [10,11]. In a study conducted by Rosario-beltré et al. (2023), the potential of Spanish mining waste was comprehensively investigated [12]. The study involved the collection of samples from 20 mine waste deposits, followed by detailed analyses. The results revealed that elements such as Sb, Bi, Pb, Cu, Ag, Zn, Cd, Sn, Se, and Th exhibited exceptionally high enrichment factors. Furthermore, it was estimated that specific tailings could generate up to USD 3.2 billion in gross revenue, based on current market metal prices, highlighting their significant economic potential. In this context, in Gomez et al. (2022), the potential of mine waste was examined as a source of certain elements considered critical in three different countries: Mexico, Chile, and Australia [13]. Data from 2976 samples were analyzed, revealing that Mexican mine waste has significant potential for elements such as Bi, Sb, W, In, Zn, and Mo. Chilean mine waste showed potential for Bi, Sb, W, and Mo, while Australian mine waste demonstrated significant potential, primarily for Co. As part of a study led by Ceniceros-Gómez et al. (2018), an in-depth characterization was performed on samples from nine separate mine waste sites in Mexico, encompassing physicochemical, mineralogical, and elemental analyses [14]. The primary objective was to explore the recovery potential of certain strategic elements, such as Ga, In, Ge, and REEs. The results highlighted a particularly high recovery potential for Ga, Y, La, Ce, Nd, Sc, In, and Au, opening up promising prospects for targeted approaches to recover these crucial elements.

Phosphate mine waste rock holds significant potential as a promising secondary source for the sustainable supply of phosphate and other critical elements. With the continuous rise in phosphate production, the volume of waste generated has also been increasing year after year, presenting an opportunity to recover these resources while addressing environmental concerns.

The rise in phosphate production is driven by phosphorus vital role in boosting plant productivity, essential for global food security as the population grows. With an annual growth rate of 1.13%, the global population is expected to increase from 7.4 billion in 2016 to 8.1 billion by 2025, driving higher demand for phosphate [15]. Phosphate rock, the primary source of phosphorus for agriculture, remains crucial, justifying large-scale production. Global phosphate production reached 220 million tons in 2021, rose to 228 million tons in 2022, and slightly declined to 220 million tons in 2023 [6,16].

The production of phosphate through open-pit mining generates a significant amount of waste. This quantity can be estimated using a stripping ratio, which, in the case of phosphate, varies from 1:1 to 12:1; this means that for a 12:1 stripping ratio, 12 tons of waste rock must be removed to extract one ton of phosphate [17,18,19]. These wastes contain P2O5 concentrations ranging from 5% to 20%, as well as all some trace elements such as magnesium, rare earth elements, vanadium, strontium, and other critical elements [19,20,21]. Regarding the recovery of residual phosphate from waste rock, flotation has become an increasingly promising approach, especially with the development of new reagents and recent advances in processing technologies [22,23,24]. To date, relatively few studies have focused on the recovery of critical elements from phosphate waste rock. Among these, Ji et al. (2021) [25] investigated the enhancement of rare earth element (REE) recovery through thermal treatment. Before calcination, the recovery yields for light rare earth elements (LREEs) and heavy rare earth elements (HREEs) were 36% and 65%, respectively. However, after thermal treatment at 600 °C, these yields improved significantly, reaching 73% for LREEs and 81% for HREEs [19,25].

Morocco is a country with a mining vocation; it possesses soil extremely rich in minerals, among which phosphate is found. Its phosphate reserves represent approximately 67% of global reserves [6,18]. In Morocco, the stripping ratio varies from 3 to 6. The overburden, interlayers, and non-exploitable phosphate layers are mixed and disposed of in a dump in the form of small piles called spoil piles (SPs) [26]. The screened waste rocks have already been sampled and characterized to assess their potential for phosphate recovery and the use of other lithologies present in these waste rocks as raw materials for construction [27,28].

This study aims to examine the potential of spoil piles (SPs) by estimating the concentrations of phosphate and other critical elements and assessing their recovery potential. To achieve this, a novel sampling strategy was developed to obtain representative composite samples along with a series of individual samples to provide the data for analyzing the spatial distribution of CFA (wt.%) and the granulometric distribution within the SPs. A drone topographic survey was conducted to develop a 3D topographic model of the studied area and estimate the volume of these SPs. Advanced calculations, including enrichment factors, were conducted to identify elements with high levels of enrichment, while correlation coefficients were used to explore relationships between these elements. By focusing on resource recovery opportunities, this study aims to contribute to sustainable phosphate resource management and the development of circular economy solutions in mining operations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling and Material Preparation

The sampling step is recognized as a key stage in conducting studies in various fields as decisions rely on the information deduced from the collected samples. Generally, the sampling of mining waste rock presents several challenges such as (i) granulometric heterogeneity, given the presence of particles ranging from a few microns to several centimeters in size, (ii) lithological heterogeneity due to the existence of various lithologies, (iii) gravitational segregation inducing anisotropy in particle size distribution within the piles, with coarse and dense particles generally settling at the bottom, while fine and low-density particles remain at the top, and (iv) the difficulty of sampling deep within piles [18,29]. In addition to all the challenges previously discussed, sampling from waste rock piles presents significant safety risks, as these materials are often deposited loosely without compaction, leading to unstable and potentially hazardous conditions for field personnel [30].

Different sampling plans have been developed for various topics by different teams. Indeed, each team tries to develop its sampling method and seeks to justify it, as explained in the Supplementary Data [18]. At the Ben Guerir mine site, the spoil piles (SPs) encapsulate all the discussed challenges [27]. To tackle these issues, a novel strategy has been implemented to address and mitigate them effectively.

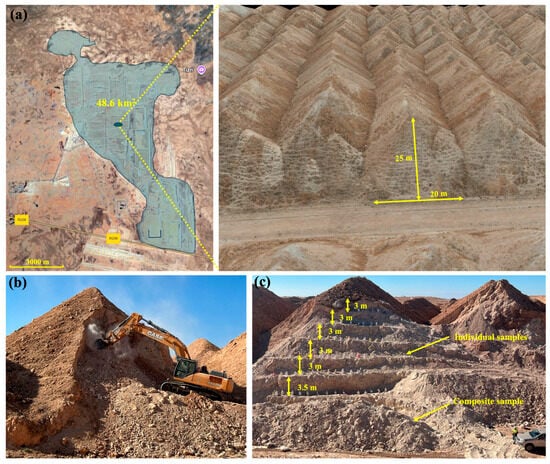

The approach involves using a hydraulic excavator to create trenches in the waste rock piles, forming vertical surfaces and establishing a series of benches to expose a continuous subsurface section. This process includes systematically marking cells, each measuring one meter in length and ranging from 3 to 3.5 m in height (Figure 1). This results in a horizontal spacing of 1 m between samples within each bench (Figure S2). One of the main objectives is to assess the distribution of elements within phosphate mining waste rock piles to identify areas of higher concentration and estimate the total volume of waste for further analysis. Once the sampling area was prepared, a topographic model was developed to study the area and accurately determine sampling points location. The use of 3D topographic modeling significantly enhanced the analysis of surface and volume, as well as the study of morphology and project visibility. For this, a drone covering an area of 0.14 km2 was employed operating at low altitudes. Real-time XYZ point corrections and geolocation adjustments of the aerial imagery were carried out using a permanent Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) network to ensure high positional accuracy. The drone was equipped with a high-resolution Nikon Coolpix A camera (32 MP), enabling the acquisition of detailed images suitable for precise mapping and structural analysis. The drone was flown at an altitude of 90 m with 70% image overlap in four directions, resulting in a high-density point cloud. The photogrammetric dataset was processed in Pix4D Mapper to produce orthomosaics and initial point clouds, which were further refined using Agisoft filtering tools to enhance point-cloud quality. The resulting data were then imported into Datamine RM for model construction. The final outputs consist of high-precision 3D topographic models with a spatial resolution of 1.24 cm/px. These georeferenced point clouds were subsequently used to build detailed 3D representations of the waste piles. Volume calculations were performed using the wireframe-volume (“wvo”) evaluation tool in Datamine RM.

Figure 1.

Sampling survey: (a) location of the study area and aerial view of SP; (b) hydraulic excavator used for the preparation of benches; (c) collection points of the composite and individual samples.

Subsequently, a series of random samples were collected from the created cells, along with a composite sample from the material removed during the creation of the vertical surface and benches. The samples were accurately labeled with their respective locations and depths, and then sealed in plastic bags to prevent contamination and shipped to the laboratory. To ensure a comprehensive study, one of the objectives was to examine the particle size distribution and size-by-size chemistry. To achieve this during the collection process, all fractions were taken into consideration. The collected samples contained particles ranging in size from a few micrometers to more than 400 mm. Following that, all samples were then subjected to a mechanical preparation stage to achieve the desired particle size for analysis. This preparation involved a series of steps including crushing, primary and secondary grinding, and quartering.

The Pierre Gy formula was used to control these steps in the laboratory and to ensure the representativeness of the sample to be analyzed. This formula takes into account several essential parameters for accurately estimating the fundamental error, including the mass of both the sample and the entire batch, particle size, and the density of each mineral phase, as detailed in Equation (1) [31].

where Ml and Ms are the weight of the lot and the weight of the sample, respectively, in grams; d represents the nominal particle size (d95); k is determined as , where l is the liberation factor, c is the mineralogical factor, g is the granulometric factor, and f is the shape factor. The fundamental error was calculated using Gy’s formula with the following parameters: the shape factor (f) was 0.5; the granulometric factor (g) was 0.25. The mineralogical composition factor (c) was determined using the equation: c = [(1 − al)/al] × [(1 − al)ρa + al × ρg], where ρa and ρg represent the density of apatite and the gangue, respectively. This factor was calculated to be 2. The mass of the sample (Ms) and the nominal particle size (D) were varied according to each fraction.

2.2. Physical and Chemical Characterization of Samples

Dry sieving was employed to determine the grain size distribution of both the composite and individual samples. The individual samples were sieved through sieves of 100 mm, 10 mm, 3.15 mm, and 1 mm. The composite sample was sieved through a more extensive range of sieves: 100 mm, 10 mm, 3.15 mm, 1 mm, 0.800 mm, 0.630 mm, 0.400 mm, 0.325 mm, 0.160 mm, 0.125 mm, 0.080 mm, 0.063 mm, and 0.040 mm. After weighing each fraction and determining their respective percentages, all fractions were then crushed and pulverized to achieve a particle size of less than 75 µm.

The determination of the concentration of the major and minor elements (CaO, SiO2, Al2O3, Fe2O3, MgO, K2O, Na2O, TiO2, P2O5, and MnO) was conducted using X-ray fluorescence analysis with a PANalytical Epsilon 4 spectrometer, Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan, which had a detection limit (DL) of 0.01%. The determination of the concentration of trace and ultra-trace elements was carried out by ICP-MS using the lithium borate fusion method, followed by acid dissolution with an acid mixture containing nitric, hydrochloric and hydrofluoric acids. The detection limit varied depending on the element: for Cs, Ha, Lu, Tb, Ti, and Tm the detection limit was 0.01 ppm; it was 0.02 ppm for Eu and Pr. The detection limit for Er, Sm, and Yb was 0.03 ppm, while for Dy, Gd, Hf, Nb, Th, and U, it was 0.05 ppm. The detection limit was 0.1 ppm for Ce, Ga, La, Nd, Sr, Ta, and Y. Rb had a detection limit of 0.2 ppm. Ba, Sc, Sn, and W had a detection limit of 0.5 ppm, while Zr had a detection limit of 1 ppm. For Cr and V, the detection limit was 5 ppm. The determination of the loss on ignition was examined on the pulverized samples using a muffle furnace at a temperature of 1000 °C. Major and minor element analyses were conducted on all fractions of the individual samples (410 samples), as well as on the fractions of the composite. Additionally, chemical analyses for trace and ultra-trace elements were performed on the composite sample and 40 samples from fractions smaller than 1 mm of the individual samples.

2.3. Mineralogical Characterization

Mineralogical analysis was performed on five size fractions of the composite sample: <1 mm, 1–3.15 mm, 3.15–10 mm, 10–100 mm, and >100 mm, as well as on the two lithologies bearing phosphate identified in the coarse fractions, using the automated mineralogical system Tescan Integrated Mineral Analyzer (TIMA), Brno, Czech Republic. The samples with particle size greater than 1 mm were crushed and totally sieved through a 1 mm sieve before analysis. The ultimate goal was to measure phosphate grain size across different fractions and quantify the mineral composition of each. This study was conducted on polished thin sections. Graphite was used in the preparation of the sections to promote particle dispersion. The analysis was conducted under the following parameters: a beam energy of 25 keV, a beam current of 8.93 nA, a spot size of 75.99 nm, and pixel spacing of 2 µm. The mineralogical data acquired from the sample analysis were processed using TIMA software, version 2.9.0.

2.4. Calculation of Enrichment Factors

To assess the potential for recovering critical elements present in the phosphate mining waste rock, the Enrichment Factor (EF) was calculated. This indicator serves as an effective tool for identifying elements that are enriched in mining waste [12,32,33]. According to Chester et al. (1973), the general equation for calculating the EF of chemical elements is represented by Equation (2) [34].

where EI(Sample) is the concentration of the concerned element in the sample. EI(Crust) is the average concentration of this element in the Earth’s crust. X(Sample) is the concentration of the element considered as a reference in the sample. X(Crust) is the average concentration of this reference element in the Earth’s crust. These concentrations are expressed in g/t or mg/kg.

The reference element, before being chosen, must meet certain criteria. It must vary proportionally with the naturally occurring concentrations of the element of interest, be insensitive to inputs from anthropogenic sources, and remain stable, unaffected by environmental processes such as reduction/oxidation, adsorption/desorption, or other diagenetic processes. In this study, the element of interest is phosphorus, along with other critical and economically important elements [35]. In this study, aluminum (Al) was chosen as a reference for the calculation of enrichment factors, and the average concentrations of elements in the Earth’s crust were taken from the Treatise on Geochemistry [36].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Evaluation of Sampling Strategy

The ultimate goal of sampling is to carefully select and collect representative samples, to obtain accurate assays. However, this task remains challenging, especially given the complexities elucidated earlier. Comparing the physical and chemical properties of the composite sample with those of the individual samples is a reliable approach to assess the representativeness of the composite. To this end, a comparative analysis was performed on the particle size distribution and chemical composition of both the composite and individual samples.

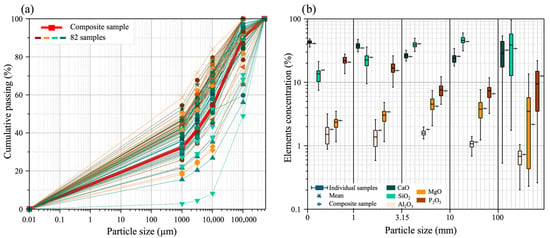

The results of the granulometric analysis are illustrated in Figure 2. The particle size distribution of the composite sample generally aligns with the average of the 82 individual samples. Specifically, the particle size distribution of the composite sample reveals that the d80 value is 50,000 µm, indicating that 80% of the sample mass consists of particles smaller than 50,000 µm. Additionally, the d50 value is approximately 7000 µm. Regarding the percentage of each fraction, the results indicate that the fraction less than 1 mm constitutes 32.48%, the fraction between 1 mm and 3.15 mm accounts for 9.16%, the fraction between 3.15 mm and 10 mm represents 12.25%, the fraction between 10 mm and 100 mm makes up 36.30%, and the fraction larger than 100 mm totals 9.8%. Based on the results, the particle size distribution of the composite sample was generally consistent with the average distribution observed across the 82 individual samples. This suggests that the composite sample is representative of the diversity of particle sizes observed across all collected individual samples.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the physical and chemical properties of individual samples with those of the composite sample: (a) particle size distribution; (b) distribution of the concentration of the of P2O5, CaO, MgO, SiO2 and Al2O3.

The choice and effectiveness of certain separation techniques depend on the particle size of the material to be treated, emphasizing the importance of studying the particle size distribution for the valorization of mining waste [18]. The fraction greater than 10 mm represent 46.1% can be effectively treated using ore sorting technology. This is due to the form in which phosphate occurs in these fractions, which corresponds to indured phosphate and phosphate flint [27]. The two fractions +1/−3.15 mm, and +3.15/−10 mm, are considered suitable feed particle sizes for gravity separation, while the fraction smaller than 1 mm is ideal to be processed by grinding, desliming, and flotation [18]. The concentrations of phosphate, calcium, magnesium, silicate, and aluminum in the five fractions of the 82 individual samples were compared to their concentrations in the composite sample. The results of this comparison are illustrated in Figure 2. The median P2O5 content across all individual samples was 12.8%, the mean was 13.0%, and the standard deviation was 3%. In addition, the results show that the average P2O5 concentrations in the size fractions of the individual sample were 21.8% for particles less than 1 mm, 16.75% for 1–3.15 mm, 7.6% for 3.15–10 mm, 7.34% for 10–100 mm, and 9% for particles greater than 100 mm. In the composite sample, the P2O5 concentrations for the same fractions were 20.7%, 15.3%, 7.3%, 6.65%, and 12.5%, respectively. The MgO concentrations in the individual sample fractions were 1.1%, 1.1%, 2.0%, 1.2%, and 3.4%, while the composite sample had MgO concentrations of 2.4%, 3.4%, 4.2%, 3.8%, and 2.1% for the same fractions, respectively.

These results indicate that the concentrations of these elements in the various fractions of the composite sample align perfectly with the average concentrations of the corresponding fractions in the individual samples, confirming the representativeness of the composite sample; this representativeness enhances the reliability of the data obtained from the composite sample.

The fundamental errors corresponding to the preparation stage of the five fractions of the composite sample were calculated. The results, according to Gy’s formula, represented in the nomograms in Figure S1, show that the error committed during the mechanical preparation of the samples (sampling, crushing, and grinding) is less than 10%, which corresponds to Gy’s safety line. This indicates that the protocol followed for the mechanical preparation of the five fractions was optimal.

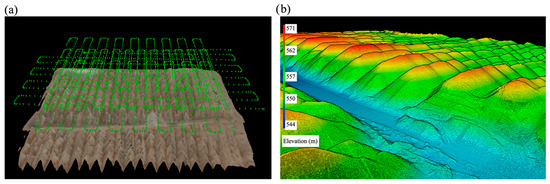

3.2. Three-Dimensional Topographic Model and Spatial Distribution of CFA and Particle Size

In this study, the 3D topographic model of SP was developed using drone imagery data. The data processing workflow began with the generation of a point cloud, followed by the creation of an orthoimage and digital surface model (DSM), culminating in 3D modeling (Figure 3b). The 3D model reveals that SPs are deposited in uniform-shaped piles on a surface at an elevation of 544 m, with an approximate height of 30 m, confirming the effectiveness of the mining method employed in this area. Based on the developed 3D model, the volume of SPs in the studied area is estimated to be 1,245,541 m3. Additionally, the projection across the entire SP dump, which covers a surface area of 48,633,000 m2, indicates that the Benguerir SP dump contains an estimated volume of 419,612,367 m3. The substantial volume of this waste rock underscores the importance of further research into developing processes for recovering phosphate, along with other critical and strategic elements.

Figure 3.

(a) Drone flight paths for image capture; (b) 3D topographic model of the sampled area, with elevation represented by color.

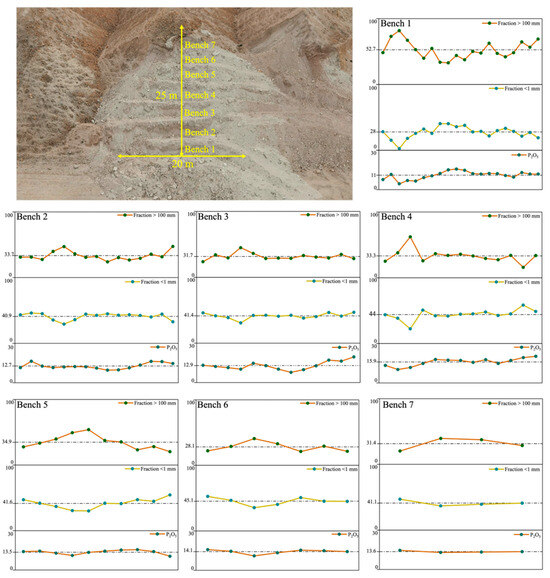

Figure 4 presents the spatial distribution of chemical grades and particle size fractions across different benches, offering key insights into phosphate concentration patterns within the piles and identifying high-concentration zones (e.g., bottom, middle, or top). This study is essential for developing efficient exploitation strategies and establishing processes for the recovery of valuable elements. Figure 4 illustrates a clear trend in particle size distribution within the waste rock pile, showing a significant increase in the proportion of coarser particles from the top to the bottom. The average percentage of particles larger than 100 mm reaches 52.7% at the bottom (bench 1), while this proportion decreases progressively toward the top, dropping to 31.4% and 28.1% in benches 7 and 6, respectively. In contrast, the upper portions of the pile contain a higher proportion of finer particles. The average percentage of particles less than 1 mm is 45.1% in bench 6 and 41.15% in bench 7, compared to 28% in bench 1. This vertical segregation is attributed to gravitational settling and material sorting during the deposition process [18,28,37]. The spatial distribution of P2O5 within the waste rock pile, also shown in Figure 4, indicates that phosphate is mainly concentrated in the upper sections, especially in areas with a high proportion of fine particles (<1 mm). The average P2O5 content increases from an average of 11% in bench 1 to 14.1% and 13.6% in benches 6 and 7, respectively. This observation is further supported by the chemical characterization results in Figure 2b, which demonstrate the strong correlation between P2O5 content and particle size. These findings provide valuable insight into the spatial distribution of phosphate-rich zones and are crucial for developing targeted waste valorization strategies.

Figure 4.

Spatial analysis of phosphate mining waste rock pile (SP): distribution of P2O5, percentage of the <1 mm fraction, and >100 mm fraction across different benches.

3.3. Mineralogical Characterization

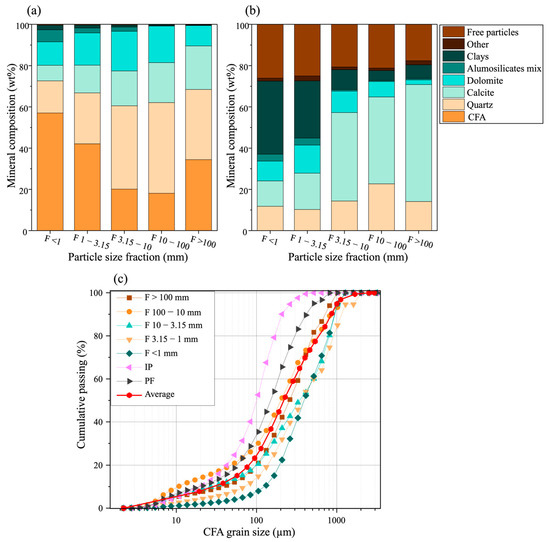

The mineralogical characterization conducted on the polished sections, representing the main fractions of the composite sample using automated mineralogy, is shown in Figure 5. The percentage of CFA in the different fractions was 57.0% (less than 1 mm), 42.1% (between 1 and 3.15 mm), 20.1% (between 3.15 and 10 mm), 18.1% (between 10 and 100 mm), and 34.4% (greater than 100 mm). According to these results, the fraction smaller than 1 mm is the richest in CFA, while the coarser fractions are richer in quartz. Quartz concentration reaches 40.37% in the fraction between 3.15 and 10 mm, 43.9% in the fraction between 10 and 100 mm, and 34% in the fraction greater than 100 mm. Clays and aluminosilicates are more concentrated in the fine fractions. The mineralogical associations of CFA are shown in Figure 5b. The fine fraction (<1 mm) exhibits the highest proportion of liberated CFA particles, reaching 29.4%. Within this fraction, CFA is predominantly associated with clays, aluminosilicates, and dolomite. In contrast, the coarser fractions display stronger associations with calcite and quartz. More specifically, 40% of CFA in the <1 mm fraction is associated with clays, whereas in the >100 mm fraction, 52.63% of CFA is associated with calcite. The strong associations observed between CFA and calcite or quartz in the coarse fractions are mainly attributed to the two principal lithologies in which phosphate occurs: indured phosphate (CFA cemented by carbonates) and phosphate flint (CFA cemented by quartz).

Figure 5.

Mineralogical characterization of the five fractions of the composite sample: (a) Mineral composition of the five fractions of the composite sample; (b) CFA association in the five fractions of the composite sample; (c) CFA grain size along with the average grain size.

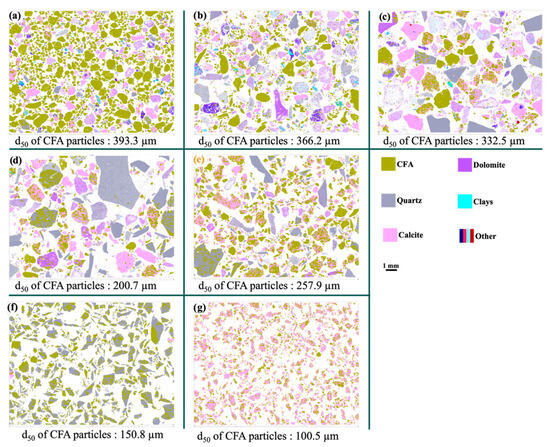

The grain size distribution of CFA in the five fractions of the composite sample is presented in Figure 5c. The results reveal an inverse relationship between the grain size of CFA and the particle size fractions. Specifically, the results show that as the particle size of the fractions increases, the grain size of CFA decreases. For example, the average size of CFA grains in the <1 mm fraction is significantly larger than that observed in the >100 mm fraction. This variation can be attributed to the different forms in which CFA is present. In the fine fraction (<1 mm), CFA is predominantly found in the form of sandy phosphate, characterized by relatively larger and freer grains. In contrast, in the coarser fractions, CFA is often embedded in more complex matrices, such as calcareous phosphate or siliceous phosphate (Figure 6) [27].

Figure 6.

False-color compositional scanning electron microscope (SEM) images and d50 values of CFA particles in five fractions obtained using TIMA®: (a) fraction −1 mm, (b) fraction +1/−3.15 mm; (c) fraction +3.15/−10 mm; (d) fraction +10/−100 mm; (e) fraction +100 mm; (f) Phosphate flint; (g) Indured phosphate.

Determining the mineral phases present in the gangue, as well as the mineral associations and mineral liberation, is essential for developing a suitable beneficiation method. Knowing the mineral composition allows for the optimization of treatment and beneficiation processes, which can improve the recovery efficiency of valuable minerals [38,39]. Mineralogical characterization shows that the fraction smaller than 1 mm contains more than 50% CFA, indicating that reverse flotation can be used for the treatment of this type of ore. In contrast, other fractions contain less than 50% CFA, which requires direct flotation. The fraction smaller than 1 mm contains a substantial amount of clay minerals. In this fraction, approximately 40.06% of CFA is associated with clay, underscoring the importance of using attrition and desliming as preconcentration techniques [18,40,41]. For the coarse fractions containing high concentrations of carbonates (calcite, dolomite) and silicates (quartz), a series of preconcentration steps can be employed. This may involve employing gravity separation to remove silicates, taking advantage of the density difference between CFA and quartz. Additionally, calcination can be utilized to reduce the carbonate content, specifically targeting minerals such as calcite and dolomite [42,43]. The evaluation of the liberation degree of waste rock is essential to estimate the potential efficiency of a separation process, thereby allowing for the best prediction of the maximum efficiency based on the ore liberation degree. This study provides information on the available free surface for a leaching study or the available free surface for the adsorption of collectors or depressants in the case of beneficiation by the flotation process [44,45].

3.4. Chemical Characterization

The chemical characterization of major elements conducted by XRF is detailed in Table 1. The results show that some fractions contain a high concentration of phosphate, exceeding 20% P2O5, with concentrations ranging from 6.6% to 26.28% P2O5. The chemical analysis of various fractions indicates that phosphate is more concentrated in the fine fractions, specifically those with a particle size of less than 1 mm. Among these, the fraction with a particle size between 160 µm and 315 µm presents the highest P2O5 content at 26.2%. The concentration of MgO varies between 1.06% and 7.35%, with the highest concentration found in the fraction less than 40 µm, at 7.35%. On the other hand, SiO2 is more concentrated in the coarse fraction, with a concentration reaching 43.94% in the fraction between 10 and 100 mm. For Al2O3, Fe2O3, K2O, and TiO2, the concentration of these oxides increases as we move towards finer fractions, which is logical since these elements are generally bearing by clays. Comparing the concentrations of these oxides from different fractions of the composite sample presented in the table with those from the UCC, it can be observed that phosphorus oxide and magnesium oxide are the most concentrated. The concentrations of P2O5, CaO, MgO, SiO2, and Al2O3 in the fractions presented in the table were studied using the results of the particle size distribution to deduce the concentrations of these major elements in five main fractions (less than 1 mm, between 1 and 3.15 mm, between 3.15 and 10 mm, between 10 and 100 mm, and greater than 100 mm). The obtained results were then combined with the concentrations of these elements in the five fractions of the 82 individual samples, as presented in Figure 2a. These findings reveal that the average phosphate concentration in the composite sample is 12.68% P2O5. The phosphate concentrations in the five fractions of the composite sample, namely less than 1 mm, between 1 and 3.15 mm, between 3.15 and 10 mm, between 10 and 100 mm, and greater than 100 mm, were 20.78% P2O5, 15.33% P2O5, 7.33% P2O5, 6.60% P2O5, and 12.55% P2O5, respectively.

Table 1.

Major and minor element oxide content (%) in different fractions of the composite sample.

According to [46], based on the P2O5 content, phosphate ore can be classified into three grades. Ore with a concentration higher than 26% P2O5 is considered high-grade, ore with a concentration between 17% and 25% P2O5 is classified as medium-grade, and ore with a concentration between 12% and 16% P2O5 is considered low-grade. Based on this classification, the fraction below 1 mm, containing 20.78% P2O5, falls into the medium-grade category, while the fraction between 1 mm and 3.15 mm, containing 15.33% P2O5, falls into the low-grade category. The overall composite sample contains 12.68% P2O5, classifying this waste rock as low-grade ore. Several studies have shown that reprocessing this type of waste rock, initially containing a concentration of around 10% P2O5, can yield good results and produce a concentrate of marketable quality. Shariati et al., (2015) [43] studied the beneficiation of a sedimentary phosphate ore containing a concentration of 9% to 10% P2O5. During this study, calcination and gravity separation were applied at both laboratory and semi-industrial (pilot) scales. The results showed that the final concentrate obtained contained 30.77% P2O5, with a recovery rate ranging from 60.7% to 63.2%. Boujlel et al. (2019) studied the feasibility of processing low-grade phosphate ore containing 12% P2O5, considered low-grade phosphate ore, using a combination of scrubbing, attrition, grinding, and reverse flotation treatments [47]. The authors achieved a concentrate containing 27.1% P2O5 with a recovery rate of 92%. Further treatment, however, is necessary to achieve a marketable quality.

Magnesium is regarded as a critical material for many countries due to its essential role in various industries, particularly within the context of the global energy transition [48]. It reaches a concentration of 7.35% in the fraction of less than 40 µm, representing a potential secondary source of this element. The valorization of this fine fraction can be achieved through a process that combines leaching and precipitation [49]. This procedure may be carried out using either a single step leaching method, where phosphorus (P) and magnesium (Mg) are simultaneously leached and subsequently recovered through precipitation, or a two-step approach. In the latter, Mg is selectively leached and separated first, followed by a second leaching stage to extract and recover P from the remaining residue. By employing this strategy, the selective recovery of both elements is facilitated, thereby promoting the efficient utilization of secondary resources and supporting the sustainable management of critical materials [50,51]. In a recent study, the effectiveness of the two-step leaching protocol for maximizing Mg and P separation was demonstrated by Yu et al. (2024) [50]. During the first step, conducted at pH 2 and 60 °C using hydrochloric acid, a Mg leaching efficiency of 93.11% was obtained. Subsequently, during the second step, carried out at pH 1.5 and 60 °C, a P leaching efficiency of 97.9% was achieved. Following these steps, P was precipitated as calcium phosphate, resulting in a P recovery rate exceeding 98%.

The characterization of rare earth elements performed by ICP-MS is presented in Table 2. The concentration of total REEs in the various fractions of the composite sample ranged from 67.28 to 267.8 ppm. Similar REE concentrations were reported in the phosphate waste generated at the Abu Tartur mine, where the average REE concentration found was around 300 ppm [52]. Concentrations exceeding 200 ppm were observed in the fractions between 80 and 125 µm, 125 and 160 µm, and 160 and 315 µm. Among the REEs, yttrium was identified as the most concentrated element, with levels ranging from 24.3 to 106.5 ppm. Its highest concentration, 106.5 ppm, was detected in the fraction between 125 and 160 µm. The elevated concentrations observed in the fine fractions are primarily attributed first to the association of REEs with carbonated fluorapatite (CFA) through substitution for Ca2+ within the crystal structure, and additionally to the enrichment of these fractions in phosphate [53,54,55]. The enrichment factor was calculated based on Equation (2) and is presented in Table 2 and Table 3. The enrichment factor is interpreted according to five categories. An enrichment factor less than 2 corresponds to a state of deficiency to minimal enrichment, a factor between 2 and 5 corresponds to moderate enrichment, a factor between 5 and 20 corresponds to significant enrichment, a factor between 20 and 40 corresponds to very high enrichment, while a factor greater than 40 corresponds to extremely high enrichment [56,57]. The enrichment factors for the total REEs range from 3.81 to 17.82. The highest observed enrichment factor, 17.82, occurs in the 125 to 160 µm fraction, corresponding to moderate enrichment. Within this fraction, yttrium displays the highest enrichment factor, reaching 61.80, which indicates extremely high enrichment. In both the 125 to 160 µm and 160 to 315 µm fractions, the following elements—Eu, Gd, Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Tm, Yb, and Lu—exhibit enrichment factors exceeding 20, reflecting very high enrichment levels. Fractions containing over 200 ppm of ∑REE, along with enrichment factors greater than 20 (125 to 160 µm and 160 to 315 µm), are considered very highly enriched. These fractions could be strategically targeted for the recovery of rare earth elements, which play a critical role in enabling the energy transition. Al-Thyabat and Zhang, (2016) studied the recovery of rare earth elements (REE) from phosphate processing waste [58]. The REE concentration in phosphate-processing waste generated in central Florida was around 198.2 ppm. The initial sample underwent several preconcentration steps: flotation and gravity separation. Subsequently, the sample was leached with nitric acid, followed by ion-exchange separation. The final step was precipitation with oxalic acid after increasing the pH with ammonium hydroxide. They achieved concentrations of 2130 and 3140 ppm. Liang et al. (2018) found that rare earth elements (REE) and phosphorus could be concentrated in phosphate tailings using a shaking table [59]. The concentration of REE increased from 161.82 ppm to 866.31 ppm, while the concentration of P2O5 increased from 2.99% to 11.74%. During the leaching phase, the leaching efficiency reached 61% for total REEs and 90% for phosphorus.

Table 2.

Rare earth element content (ppm) and the enrichment factor in the different fractions of the composite sample.

Table 3.

Content of other critical and strategic elements (ppm) and the enrichment factor in the different fractions of the composite sample.

For the other critical and strategic elements (Table 3), it was found that strontium, vanadium, and uranium are the most concentrated in the different fractions of the composite sample. Uranium concentrations range from 47.9 ppm to 173.5 ppm, strontium from 304 ppm to 1090 ppm, and vanadium from 80 ppm to 227 ppm. Notably, high concentrations of uranium and strontium were found in the fraction between 80 and 1000 µm. Regarding the enrichment factor, strontium shows an enrichment factor greater than 20 in the fractions between 400 µm and 1000 µm, indicating very high enrichment. In the fractions between 125 µm and 315 µm, strontium exhibits an enrichment factor greater than 40, corresponding to extremely high enrichment. For uranium, the enrichment factor was greater than 159.14 in all fractions, reaching 882.11 in the fraction between 160 µm and 315 µm, indicating that uranium is extremely enriched in all fractions of the composite sample. For vanadium, the enrichment factor was greater than 20 in the fractions between 160 µm and 400 µm, indicating very high enrichment in these fractions. Nuclear energy has been gaining renewed interest due to its low carbon emissions, energy security concerns, and technological advancement. In Belgium, seven nuclear power plants provided about 40% of domestic electricity generation in 2020. In Ukraine, 15 reactors produced 51% of the country’s electricity in the same year, while in France, 56 operational reactors generated 70% of the country’s electricity [60,61]. The demand for uranium, the key element used in nuclear plants, has risen in recent years, particularly due to supply chain disruptions. In 2020, this demand exceeded global production. The growing need for uranium, combined with its concentration in politically unstable regions, highlights the importance of extracting this element from unconventional sources. One of the most promising unconventional sources of uranium is phosphate rock [62]. The presence of uranium in phosphate rock is explained by two factors: the substitution of calcium in the apatite structure and the adsorption of uranium onto the surfaces of apatite crystals. Uranium (IV) can replace calcium due to the similar ionic properties of U(IV) and Ca2+, while UO22+ adsorbs onto the crystal surfaces of the apatite [55,63,64]. In the United States, 20% of the mined uranium was obtained from the phosphate fertilizer production in Florida and Louisiana from 1980 to 1990 [65]. Among the upcoming projects, there are plans to recover uranium for use in the production of nuclear fuel, as well as for producing diammonium phosphate. These initiatives are expected to take place at the Santana, Quitéria, and Itatia mines in Brazil [65,66]. The study conducted by Ulrich et al. (2014) on estimating uranium reserves in phosphates across various countries indicates that the United States, Morocco, Tunisia, and Russia are particularly well-suited for recovering uranium from phosphate rocks [62]. The estimation calculations were based on uranium concentrations ranging from 28 to 120 ppm, with a concentration of 97 ppm in phosphate rock from Morocco. Notably, uranium concentrations in phosphate mining waste rock piles range from 47.9 to 173 ppm, further demonstrating the potential for uranium recovery from SPs. In a study by [67], uranium leaching from phosphates originating from Morocco, Tunisia, and Syria was examined. The initial uranium concentrations in the phosphates from Morocco, Tunisia, and Syria were 117 ppm, 32 ppm, and 61 ppm, respectively. A 100% uranium leaching rate was achieved using sulfuric acid under the following conditions for all three types of phosphate: one hour, a temperature of 60 °C, and the use of H2O2 as an oxidizing agent. These results underscore significant opportunities for uranium extraction from spoil piles, with the added environmental benefit of removing this element from mine dumps.

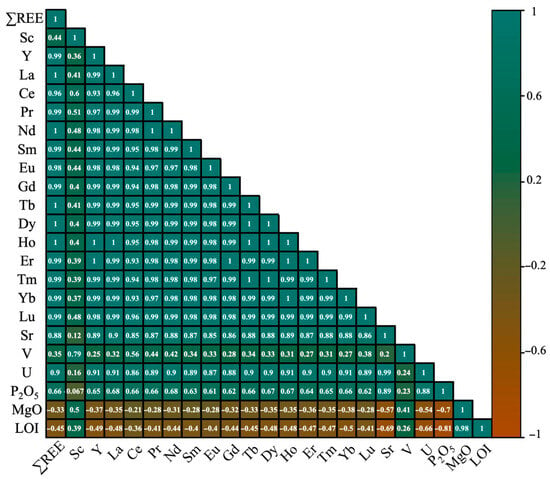

3.5. Correlation

To analyze the correlation between critical and strategic elements with potential, the correlation coefficient was calculated using Pearson correlation. Studying correlation coefficients is essential for identifying elements that can be jointly valorized. This coefficient is a non-parametric measure of the strength and direction of association between two variables ranked by order. In this case, the variables are the concentrations of elements per sample. The correlation coefficient varies from 1 to −1, where 1 indicates a perfect positive correlation, −1 indicates a perfect negative correlation, and 0 indicates no correlation [68,69]. It should be noted that there is no universally accepted standard for interpreting the strength of the correlation based on the tau value. According to [70], a tau less than |0.1| indicates a negligible correlation, between |0.1| and |0.39| suggests a weak correlation, between |0.4| and |0.69| suggests a moderate correlation, between |0.7| and |0.89| suggests a strong correlation, and a tau equal to or greater than |0.9| is considered a very strong correlation. For the calculation of the correlation coefficient, the OriginLab Pro software (version 10.2.0.196) was used, and the results are presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Correlation coefficients of REE and other strategic elements with potential existing in various fractions of the composite sample.

The correlation analysis revealed a moderate positive correlation between total ∑REE and P2O5, with a correlation coefficient of 0.66. Individual rare earth elements, including Y, La, Ce, Pr, Nd, Sm, Eu, Gd, Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Tm, Yb, and Lu, showed moderate positive correlations with P2O5, ranging from 0.61 to 0.68. In contrast, Sc exhibited a negligible negative correlation (r = −0.067). Among other critical elements, Sr and U displayed strong positive correlations with P2O5, with coefficients of 0.89 and 0.88, respectively. Vanadium showed a weak positive correlation (r = 0.23). Magnesium, on the other hand, had a strong negative correlation with P2O5 (r = −0.7), but a very strong positive correlation with LOI (r = 0.98). Several studies have examined the correlation of REE, U, Sr, and V with phosphate, and similar results have been reported. For example, a study conducted by [71] on sixty-three samples of deposits from the Al-Kora province in northwest Jordan found a highly significant positive correlation coefficient between U and P2O5 (r = 0.86), between Sr and P2O5 (r = 0.9), and between Y and P2O5 (r = 0.4). Another study conducted by [72] aimed to evaluate phosphate deposits in Saudi Arabia as a potential source of trace elements and REEm and found that phosphate P2O5 content showed a positive correlation with U, Sr, V, and Y. These results suggest that REE, along with other strategically and economically significant elements, are associated with phosphate. Consequently, it is feasible to start concentrating these valuable elements by first enriching the phosphate minerals, as this process is more straightforward and well-established.

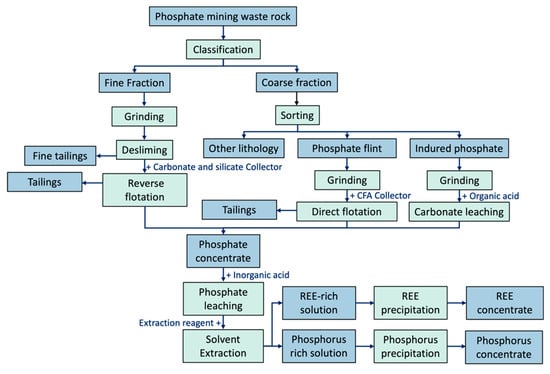

4. Phosphate Mine Waste Rock Valorization

This study confirms that the spoil piles (SPs) at the Ben Guerir mine site contain substantial amounts of phosphate, along with other valuable critical and strategic elements. Chemical analyses revealed an average P2O5 content of 12.6% in an estimated 419 million m3 of waste rock, illustrating the substantial potential for SP valorization. To upgrade and recover the remaining phosphate, a process integrating sensor-based sorting, classification, grinding, desliming, and flotation is proposed (Figure 8). Regarding the valorization process, applying an initial classification at a 10 mm cut size was found to enhance phosphate enrichment, increasing the P2O5 concentration from 12.6% to 16.8% with a projected recovery rate of 71.4%. Simultaneously, approximately 61.1% of the silica (SiO2) would be removed, reducing its content from 31.5% to 22.7% in the undersized fraction. This outcome indicates that classification can serve as an effective preconcentration step, improving phosphate grade and minimizing gangue minerals. Although this approach significantly improves phosphate concentration, the coarser fraction (>10 mm) still contains 7.8% P2O5, equivalent to 28.6% of the total phosphate. Sensor-based ore sorting offers a promising preconcentration strategy for this coarse fraction. In a study by Amar et al. (2023), sensor-based sorting increased the P2O5 content in the >30 mm fraction from 13.5% to 18.5%, with a corresponding 70% recovery of the phosphate in that fraction [27]. These findings confirm the feasibility of combining classification and sensor-based sorting to enhance phosphate recovery from mine waste rock piles. Applying sensor-based sorting to particles larger than 10 mm not only concentrates phosphate but also separates other lithologies, which could be repurposed in construction applications. Additionally, carbonate-rich lithologies can be effectively separated using sorting techniques and used to mitigate the environmental impact of polymetallic waste rocks, which are known to cause acid mine drainage [73]. Subsequent beneficiation techniques (e.g., flotation) may then be employed to attain marketable phosphate grades [18]. Furthermore, correlation analyses revealed that critical and strategic elements within SPs are positively correlated with phosphate. Consequently, recovering phosphate also helps concentrate these elements, paving the way for their eventual extraction and providing additional economic and strategic benefits. Beyond the direct recovery of valuable resources, valorizing phosphate spoil piles offers considerable economic, environmental, and social advantages. Economically, it reduces costs by exploiting surface-deposited material, obviating the need for drilling, blasting, and stripping. Environmentally, it lowers CO2 emissions, particularly given the presence of carbonates (e.g., calcite, dolomite), prevents soil contamination, and restores large tracts of land (48 km2) for green spaces. It also reduces energy usage and greenhouse gas emissions by reducing reliance on heavy machinery required to flatten these stockpiles. Socially, SP valorization supports job creation in reprocessing, waste management, and site rehabilitation.

Figure 8.

Integrated flowsheet for the valorization of phosphate mining waste rock.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study highlight the significant potential for the valorization of waste rock and underscore the importance of adopting sustainable practices in the mining industry. The main conclusions drawn from this study are as follows:

- The developed sampling strategy ensured the collection of representative samples, as validated through comparisons of the physical and chemical properties of the composite and individual samples. However, the observed granulometric heterogeneity within the waste rock emphasizes the necessity of a second sampling phase, covering multiple zones, to achieve more comprehensive and accurate results.

- Chemical characterization identified substantial concentrations of critical and strategic elements, particularly phosphate, magnesium, rare earth elements (REEs), strontium (Sr), vanadium (V), and uranium (U), with significant potential for recovery and valorization. REEs, Sr, V, and U were notably found to be highly enriched in the finer fractions and showed a positive correlation with phosphate, except for magnesium.

- This positive correlation suggests that their preconcentration can be effectively achieved through phosphate beneficiation processes, including desliming, grinding, and flotation. Such processes not only upgrade the waste to achieve marketable phosphate quality but also concentrate these valuable elements.

- The volume estimation of the waste rock, conducted in August 2024, revealed a total volume of approximately 419,612,367 m3, underscoring the enormous resource potential embedded within these materials.

Valorizing these waste materials presents an opportunity to develop secondary resources and diversify the supply of critical and strategic elements, while also offering substantial environmental benefits. By reducing the environmental footprint of mining activities, this approach contributes to sustainable resource management and fosters economic opportunities in regions where such waste deposits exist.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/min15121319/s1, Figure S1. Sampling nomogram of the five fractions of the composite sample. Figure S2. Sampling grid used for sample collection.

Author Contributions

M.H. Conceptualization, investigation, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, software, visualization, writing—original draft preparation. Y.A.-K. Conceptualization, investigation, methodology, supervision, writing—review and editing. A.E. Conceptualization, investigation, methodology, supervision, writing—review and editing. M.E.G. Conceptualization, investigation, methodology, software, writing—review and editing. M.B. Conceptualization, investigation, methodology, supervision, writing—review and editing, resources. Y.T. Conceptualization, investigation, methodology, supervision, writing—review and editing, project administration, funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was financially supported through the research program between OCP and UM6P under the APRA project ZeroPhosWaste.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the OCP Group for its support of the Zero-PhosWaste project through the APRA program.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chernoburova, O.; Chagnes, A. Mining and Processing Residues: Future’s Source of Critical Raw Materials; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, M.; Hofmann, H.; Hagelüken, C.; Hool, A. Critical Raw Materials: A Perspective from the Materials Science Community. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2018, 17, e00074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patricia, A.D.; Silvia, B.; Samuel, C.; Beatrice, P. The Role of Rare Earth Elements in Wind Energy and Electric Mobility: An Analysis of Future Supply/Demand Balances; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020; ISBN 9789276270164. [Google Scholar]

- Buijs, B.; Sievers, H.; Espinoza, L.A.T. Limits to the Critical Raw Materials Approach. Proc. Inst. Civil. Eng. Waste Resour. Manag. 2012, 165, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, P.; Bonollo, F. Materials Selection in a Critical Raw Materials Perspective. Mater. Des. 2019, 177, 107848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Geological Survey. Survey Mineral Commodity Summaries 2024; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2024; ISBN 9781411345447.

- Grohol, M.; Veeh, C. Study on the Critical Raw Materials for the EU 2023; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2023; ISBN 9789279680519. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/57318397-fdd4-11ed-a05c-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Blengini, G.; Mathieux, F.; Mancini, L.; Nyberg, M.; Cavaco Viegas, H. Recovery of Critical and Other Raw Materials from Mining Waste and Landfills State of Play on Existing Practices; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kumari, R.; Samadder, S.R. A Critical Review of the Pre-Processing and Metals Recovery Methods from e-Wastes. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 320, 115887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dold, B. Sourcing of Critical Elements and Industrial Minerals from Mine Waste—The Final Evolutionary Step Back to Sustainability of Humankind? J. Geochem. Explor. 2020, 219, 106638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parbhakar-Fox, A.; Gilmour, S.; Fox, N.; Olin, P. Geometallurgical Characterization of Non-Ferrous Historical Slag in Western Tasmania: Identifying Reprocessing Options. Minerals 2019, 9, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosario-Beltré, A.J.; Sánchez-España, J.; Rodríguez-Gómez, V.; Fernández-Naranjo, F.J.; Bellido-Martín, E.; Adánez-Sanjuán, P.; Arranz-González, J.C. Critical Raw Materials Recovery Potential from Spanish Mine Wastes: A National-Scale Preliminary Assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 407, 137163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, D.V.; Salgado, E.S.; Mejías, O.; Pat-Espadas, A.M.; Torres, L.A.P.; Jackson, L.; Parbhakar-Fox, A. Data Integration of Critical Elements from Mine Waste in Mexico, Chile and Australia. Minerals 2022, 12, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceniceros-Gómez, A.E.; Macías-Macías, K.Y.; de la Cruz-Moreno, J.E.; Gutiérrez-Ruiz, M.E.; Martínez-Jardines, L.G. Characterization of Mining Tailings in México for the Possible Recovery of Strategic Elements. J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 2018, 88, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.D.; Mishra, R.; Maurya, K.K.; Singh, R.B.; Wilson, D.W. Estimates for World Population and Global Food Availability for Global Health; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; ISBN 9780128131480. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Geological Survey. Survey Mineral Commodity Summaries 2023; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2023; ISBN 9781411345041.

- Al-Ajeel, A.W.A.; Toama, H.Z. Mining and beneficiation of phosphate rocks: Prospects of unexploited phosphate deposits in the western desert, IRAQ. In Iraqi Bulletin Of Geology And Mining; Iraq Geological Survey (GEOSURV, Iraq); Ministry of Industry and Minerals: Baghdad, Iraq, 2017; pp. 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Amar, H.; Benzaazoua, M.; Elghali, A.; Hakkou, R.; Taha, Y. Waste Rock Reprocessing to Enhance the Sustainability of Phosphate Reserves: A Critical Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 381, 135151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, Y.; Elghali, A.; Hakkou, R.; Benzaazoua, M. Towards Zero Solid Waste in the Sedimentary Phosphate Industry: Challenges and Opportunities. Minerals 2021, 11, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Graedel, T.E. The Potential for Mining Trace Elements from Phosphate Rock. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 91, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loutou, M.; Hajjaji, M.; Mansori, M.; Favotto, C.; Hakkou, R. Phosphate Sludge: Thermal Transformation and Use as Lightweight Aggregate Material. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 130, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; He, J. New Insights into Selective Depression Mechanism of Tamarindus Indica Kernel Gum in Flotation Separation of Fluorapatite and Calcite. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 354, 128787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Li, J.; He, J.; Zhu, L.; Guo, S.; Zhang, S. Differentiated Regulation of Mineral Interface Properties Using an Eco-Friendly Polysaccharide Depressant for Enhanced Apatite–Dolomite Sustainable Flotation Separation. Green. Chem. 2025, 27, 15211–15224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-bahi, A.; Ait-Khouia, Y.; Benzaazoua, M.; Hakkou, R.; Taha, Y. Biobased Collectors for Sustainable Phosphate Ore Flotation: Enhanced Performance and Selectivity. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 341, 103506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, B.; Li, Q.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, W. Enhanced Leaching Recovery of Rare Earth Elements from a Phosphatic Waste Clay through Calcination Pretreatment. J. Clean Prod. 2021, 319, 128654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chlahbi, S.; Belem, T.; Elghali, A.; Rochdane, S.; Zerouali, E.; Inabi, O.; Benzaazoua, M. Geological and Geomechanical Characterization of Phosphate Mine Waste Rock in View of Their Potential Civil Applications: A Case Study of the Benguerir Mine Site, Morocco. Minerals 2023, 13, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amar, H.; Benzaazoua, M.; Elghali, A.; Taha, Y.; El Ghorfi, M.; Krause, A.; Hakkou, R. Mine Waste Rock Reprocessing Using Sensor-Based Sorting (SBS): Novel Approach toward Circular Economy in Phosphate Mining. Miner. Eng. 2023, 204, 108415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ghorfi, M.; Inabi, O.; Amar, H.; Taha, Y.; Elghali, A.; Hakkou, R.; Benzaazoua, M. Design and Implementation of Sampling Wells in Phosphate Mine Waste Rock Piles: Towards an Enhanced Composition Understanding and Sustainable Reclamation. Minerals 2024, 14, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sädbom, S.; Bäckström, M. Sampling of Mining Waste-Historical Background, Experiences and Suggested Methods Carbonate Hosted Magnetite; Bergskraft Bergslagen AB, Report BKBAB: Kumla, Sweden, 2018; pp. 18–109. [Google Scholar]

- Maknoon, M.; Aubertin, M. On the Use of Bench Construction to Improve the Stability of Unsaturated Waste Rock Piles. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2021, 39, 1425–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gy, P. Sampling of Particulate Materials Theory and Practice, 1st ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Akoto, R.; Anning, A.K. Heavy Metal Enrichment and Potential Ecological Risks from Different Solid Mine Wastes at a Mine Site in Ghana. Environ. Adv. 2021, 3, 100028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, A.; Hanich, L.; Bannari, A.; Zouhri, L.; Pourret, O.; Hakkou, R. Assessment of Soil Contamination around an Abandoned Mine in a Semi-Arid Environment Using Geochemistry and Geostatistics: Pre-Work of Geochemical Process Modeling with Numerical Models. J. Geochem. Explor. 2013, 125, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chester, R.; Stoner, J.H. Pb in Particulates from the Lower Atmosphere of the Eastern. Nature 1973, 245, 27–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiff, K.C.; Weisberg, S.B. Iron as a Reference Element for Determining Trace Metal Enrichment in Southern California Coastal Shelf Sediments. Mar. Environ. Res. 1999, 48, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnick, R.L.; Gao, S. Composition of the Continental Crust. In Treatise on Geochemistry; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; Volume 3–9, pp. 1–64. ISBN 9780080548074. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, P.; Pabst, T. Effect of Construction Method and Bench Height on Particle Size Segregation during Waste Rock Disposal. Int. J. Min. Reclam. Environ. 2024, 38, 677–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brough, C.P.; Warrender, R.; Bowell, R.J.; Barnes, A.; Parbhakar-Fox, A. The Process Mineralogy of Mine Wastes. Miner. Eng. 2013, 52, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, H.E.; Walker, S.R.; Parsons, M.B. Mineralogical Characterization of Mine Waste. Appl. Geochem. 2015, 57, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrova, T.; Elbendari, A.; Nikolaeva, N. Beneficiation of a Low-Grade Phosphate Ore Using a Reverse Flotation Technique. Miner. Process. Extr. Metall. Rev. 2022, 43, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S.S.; Yassin, K.E.; Boulos, T.R. Processing of an East Mediterranean Phosphate Ore Sample by an Integrated Attrition Scrubbing/Classification Scheme (Part One). Sep. Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 967–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouzeid, A.Z.M. Physical and Thermal Treatment of Phosphate Ores—An Overview. Int. J. Miner. Process 2008, 85, 59–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariati, S.; Ramadi, A.; Salsani, A. Beneficiation of Low-Grade Phosphate Deposits by a Combination of Calcination and Shaking Tables: Southwest Iran. Minerals 2015, 5, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leißner, T.; Mütze, T.; Bachmann, K.; Rode, S.; Gutzmer, J.; Peuker, U.A. Evaluation of Mineral Processing by Assessment of Liberation and Upgrading. Miner. Eng. 2013, 53, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, R.; Simons, B.; Bru, K.; de Sousa, A.B.; Rollinson, G.; Andersen, J.; Martin, M.; Machado Leite, M. Use of Mineral Liberation Quantitative Data to Assess Separation Efficiency in Mineral Processing—Some Case Studies. Miner. Eng. 2018, 127, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryszko, U.; Rusek, P.; Kołodyńska, D. Quality of Phosphate Rocks from Various Deposits Used in Wet Phosphoric Acid and P-Fertilizer Production. Materials 2023, 16, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boujlel, H.; Daldoul, G.; Tlil, H.; Souissi, R.; Chebbi, N.; Fattah, N.; Souissi, F. The Beneficiation Processes of Low-Grade Sedimentary Phosphates of Tozeur-Nefta Deposit (Gafsa-Metlaoui Basin: South of Tunisia). Minerals 2019, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, S.K.; Haque, N.; Bhuiyan, M.; Bruckard, W.; Pramanik, B.K. Recovery of Strategically Important Critical Minerals from Mine Tailings. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balagh, Z.; Ait-khouia, Y.; Benzaazoua, M.; Taha, Y. Magnesium and Calcium Extraction from Phosphate Mine Waste Rock Using Phosphoric Acid: Thermodynamics, Parameter Optimization, Kinetics, and Reaction Mechanism. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2025, 146, 812–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.H.; Du, C.M.; Zhang, Y.T.; Yuan, R.Y. Phosphorus Recovery from Phosphate Tailings through a Two-Stage Leaching-Precipitation Process: Toward the Harmless and Reduction Treatment of P-Bearing Wastes. Environ. Res. 2024, 248, 118328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.H.; Du, C.M. Leaching of Phosphorus from Phosphate Tailings and Extraction of Calcium Phosphates: Toward Comprehensive Utilization of Tailing Resources. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 347, 119159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abou El Anwar, E.A.; Rashwan, M.A.; Abd El Samee, M.A.; Belal, Z.L.; Salman, S.A.; Seleem, E.M.; Abdelwahab, W.; Abd El-Shakour, Z.; Kamal, M.; Ahmed, A.S. Mining and Industrial Processing Wastes of Phosphate Rocks in Egypt: Potentiality of Rare Earth Elements. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 22, 10613–10623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumaza, B.; Chekushina, T.V.; Kechiched, R.; Benabdeslam, N.; Brahmi, L.; Kucher, D.E.; Rebouh, N.Y. Environmental Geochemistry of Potentially Toxic Metals in Phosphate Rocks, Products, and Their Wastes in the Algerian Phosphate Mining Area (Tébessa, NE Algeria). Minerals 2023, 13, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pufahl, P.K.; Groat, L.A. Sedimentary and Igneous Phosphate Deposits: Formation and Exploration: An Invited Paper. Econ. Geol. 2017, 112, 483–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClellan, G.H. Mineralogy of Carbonate Fluorapatites. Geol. Soc. 1980, 137, 675–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvine Paternie, E.D.; Hakkou, R.; Ekengele Nga, L.; Bitom Oyono, L.D.; Ekoa Bessa, A.Z.; Oubaha, S.; Khalil, A. Geochemistry and Geostatistics for the Assessment of Trace Elements Contamination in Soil and Stream Sediments in Abandoned Artisanal Small-Scale Gold Mining (Bétaré-Oya, Cameroon). Appl. Geochem. 2023, 150, 105592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Wang, L.; Lei, K.; Huang, J.; Zhai, Y. Contamination Assessment of Copper, Lead, Zinc, Manganese and Nickel in Street Dust of Baoji, NW China. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 161, 1058–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Thyabat, S.; Zhang, P. Extraction of Rare Earth Elements from Upgraded Phosphate Flotation Tailings. Miner. Metall. Process. 2016, 33, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Zhang, P.; Jin, Z.; Depaoli, D.W. Rare Earth and Phosphorus Leaching from a Flotation Tailings of Florida Phosphate Rock. Minerals 2018, 8, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehm, T.E. Advanced Nuclear Energy: The Safest and Most Renewable Clean Energy. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2023, 39, 100878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NEA & AIAE. Uranium 2022: Resources, Production and Demand. Nuclear Energy Agency and International Atomic Energy Agency. 2023. Available online: http://oecd-nea.org/jcms/pl_79960/uranium-2022-resources-production-and-demand?details=true (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Ulrich, A.E.; Schnug, E.; Prasser, H.M.; Frossard, E. Uranium Endowments in Phosphate Rock. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 478, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qamouche, K.; Chetaine, A.; Elyahyaoui, A.; Moussaif, A.; Touzani, R.; Benkdad, A.; Amsil, H.; Laraki, K.; Marah, H. Radiological Characterization of Phosphate Rocks, Phosphogypsum, Phosphoric Acid and Phosphate Fertilizers in Morocco: An Assessment of the Radiological Hazard Impact on the Environment. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 27, 3234–3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, D. Agricultural and Mineral Commodities Year Book, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Haneklaus, N.; Sun, Y.; Bol, R.; Lottermoser, B.; Schnug, E. To Extract, or Not to Extract Uranium from Phosphate Rock, That Is the Question. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 753–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD; NEA. Uranium 2016: Resources, Production and Demand. 2016. No. 7301. Available online: https://www.oecd-nea.org/jcms/pl_15004/uranium-2016-resources-production-and-demand?details=true (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Kiegiel, K.; Gajda, D.; Zakrzewska-Kołtuniewicz, G. Recovery of Uranium and Other Valuable Metals from Substrates and Waste from Copper and Phosphate Industries. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 2099–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergsma, W.; Dassios, A. A Consistent Test of Independence Based on a Sign Covariance Related to Kendall’s Tau. Bernoulli 2014, 20, 1006–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, B. Chatterjee Correlation Coefficient: A Robust Alternative for Classic Correlation Methods in Geochemical Studies—(Including “TripleCpy” Python Package). Ore Geol. Rev. 2022, 146, 104954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schober, P.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation Coefficients: Appropriate Use and Interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abed, A.M.; Jaber, O.; Alkuisi, M.; Sadaqah, R. Rare Earth Elements and Uranium Geochemistry in the Al-Kora Phosphorite Province, Late Cretaceous, Northwestern Jordan. Arab. J. Geosci. 2016, 9, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.H.; Aseri, A.A.; Ali, K.A. Geological and Geochemical Evaluation of Phosphorite Deposits in Northwestern Saudi Arabia as a Possible Source of Trace and Rare-Earth Elements. Ore Geol. Rev. 2022, 144, 104854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakkou, R.; Benzaazoua, M.; Bussière, B. Valorization of Phosphate Waste Rocks and Sludge from the Moroccan Phosphate Mines: Challenges and Perspectives. Procedia Eng. 2016, 138, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).