Abstract

The Wunuer deposit is an important hydrothermal Zn-Pb-Ag-Mo polymetallic deposit in the central Great Xing’an Range, NE China. The zinc–lead polymetal mineralization is closely hosted by the volcanic rocks of the Manketouebo formation (rhyolite and lithic crystal tuff) and related to the Mesozoic granite porphyry. Field evidence and petrographic observations have identified three mineralization stages within this deposit from deep to shallow: (1) late magmatic stage with vein-type Mo mineralization characteristics and mainly related to the deep granite porphyry; (2) magmatic–hydrothermal transition stage characterized by breccia-type Zn mineralization, which occurred within a steep cryptoexplosive breccia; and (3) hydrothermal stage featured by vein-type Zn-Pb-Ag mineralization hosted by the ore-bearing fractured zone. In this contribution, we present the mineralogy, zircon U-Pb age, sphalerite Rb-Sr dating, whole-rock geochemistry, and Hf-S-Pb isotopes of the Wunuer deposit. LA-ICP-MS zircon U-Pb dating of the ore-related granite porphyry, rhyolite, and lithic crystal tuff suggests that the Mo mineralization from the late magmatic stage occurred between 144.8 Ma and 145.8 Ma. The Rb-Sr isochron dating of sphalerite indicates that the hydrothermal stage Zn mineralization age is 121 ± 2.3 Ma, which is related to the volcanism of Baiyin’gaolao Formation in the Wunuer area. The concentrated and positive δ34SV-CDT values (0.17‰~5.40‰) of sulfides, as well as uniform Pb isotope compositions of granite porphyry intrusion and galena, jointly imply a magmatic source of metallogenic materials for Pb-Zn mineralization. Whole-rock geochemistry and Hf-Pb isotopes reveal that the granite porphyry and rhyolite both originated from a mantle-derived juvenile component and assimilated by minor ancient crustal material in an extensional setting. Our study demonstrates the prospect of further exploration for two mineralization events in the hydrothermal polymetallic deposits of the central Great Xing’an Range.

1. Introduction

The Great Xing’an Range Phanerozoic orogenic belt is situated between the North China Craton and the Siberian Craton, having undergone a multi-stage accretion and collage process involving the successive closures of the Paleo-Asian Ocean, the Mongol-Okhotsk Ocean, and the subsequent influence of the Paleo-Pacific Ocean [1,2,3,4]. The Mesozoic granitoids and volcanic rocks are widely distributed [1,2,5,6], and host a variety of metallogenic systems, i.e., porphyry Cu-Mo, skarn Pb-Zn-Fe-Sn, epithermal Au-Ag, and hydrothermal Zn-Cu-Pb-Sn polymetallic deposits [7,8,9,10,11]. In particular, there are several superimposed or multi-stage Pb-Zn deposits, including the Shuangjianzishan, Bianjiadayuan, Bairendaba–Weilasituo, Baiyinnuoer, and Aobaotu in the Great Xing’an Range [12,13,14,15,16,17]. The Great Xing’an Range can be divided into three sections: Northern, central, and Southern. The central Great Xing’an Range (CGXR) is noted for its substantial volcanic cover, resulting in relatively lower levels of research and exploration compared with the Northern and Southern Great Xing’an Range.

The Wunuer deposit is a recently discovered Zn-Pb-Ag-Mo deposit in the CGXR, with a metal reserve of 0.20 Mt Zn (average grade of 2.35%), 0.10 Mt Pb (average grade of 1.69%), 255 t Ag (average grade of 18.35 g/t), and 9708 t Mo [18]. Limited geochemical studies of major elements, trace elements, sulfur isotope of sphalerite, and fluid inclusions have been conducted to constrain the origin, evolution, and possible sources of the hydrothermal fluid and ore-forming components [19]. However, the systematic study in the Wunuer deposit is lacking, and the timing, source, and tectonic regime of magmatism and mineralization remain poorly constrained. A combination of field investigation and petrographic observation, U-Pb geochronology and trace element of zircon, Rb-Sr dating of sphalerite, whole-rock geochemistry, and Hf-S-Pb isotopes from igneous rocks and sulfides are presented to constrain the formation time of the host rock and ore, and to further explore the source of the metallogenetic material and tectonic background. This comprehensive data further provides insights into regional metallogeny and offers guidance for future research and exploration on multi-metal ore deposits in the central Great Xing’an Range.

2. Regional Geology

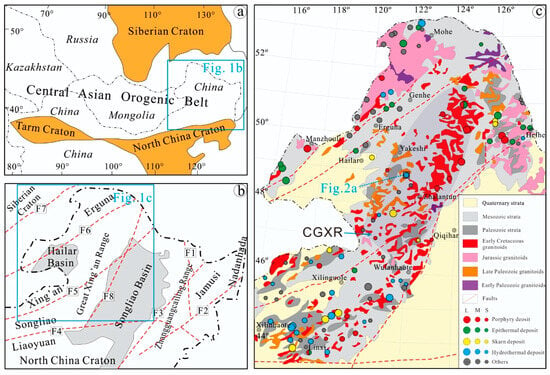

The Great Xing’an Range is located in the easternmost segment of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt (CAOB), Northeast China (Figure 1a), which is mainly composed of the Erguna, Xing’an, and Songliao blocks, and is bounded by the Mongol-Okhotsk Fault (F7) to the northwest, the Xilamulun–Changchun Fault (F4) to the south, and the Nengjiang Fault (F8) to the east (Figure 1b). The region underwent multi-stage accretion and collision after the closure of the Paleo-Asian Ocean during the Paleozoic [20]. After the Paleo-Asian Ocean finally closed along the Xilamulun–Changchun [2,4,21], regional extension occurred [22], and the area then entered into an intra-plate extensional stage, dominated by the westward subduction of the Pacific Plate during the Mesozoic [21,22].

The central Great Xing’an Range (CGXR) is located between the Xing’an and Songliao terranes seperated by the Hegenshan–Heihe Fault (F5) (Figure 1c), its regional stratigraphy could be divided into three units, listed from oldest to youngest [23], as follows: (1) Paleozoic (the Ordovician Luohe Formation, the Devonian Niqiuhe and Daminshan Formations, and the Carboniferous Moergenhe Formation) weakly metamorphosed volcanic and sedimentary rocks including chert, andesite, sandy slate, and limestone; (2) Mesozoic (Jurassic to Cretaceous) strata consisting of continental, intermediate-felsic volcanic and sedimentary sequences; and (3) Cenozoic strata, mainly including Holocene river alluvium, slope wash, marsh silt accumulation, etc.

Figure 1.

(a) Tectonic sketch map of Central Asian Orogenic Belt (after [24]). (b) Tectonic sketch map of NE China (after [21]), F1: Mudanjiang Fault, F2: Dunhua–Mishan Fault, F3: Yitong–Yilian Fault, F4: Xilamulun–Changchun Fault, F5: Hegenshan–Heihe Fault, F6: Tayuan–Xiguitu Fault, F7: Mongol–Okhotsk Fault, F8: Nenjiang Fault. (c) Distribution of igneous rocks and deposits in the Great Xing’an Range zone (modified from [21,25]). CGXR: the central Great Xing’an Range.

Intense magmatic activity occurred in the central Great Xing’an Range, producing widespread granitoids (Figure 1c). Ref. [21] identified three diagenetic events: (1) Early Paleozoic (mainly Ordovician) granitoids, including an intensively deformed granitic gneiss and associated quartz diorite from Zhalantun with ages ranging from 466 to 446 Ma; (2) Late Paleozoic (Carboniferous–Permian) granitoids mainly occurred in the north of the area and composed of granodiorite and monzogranite with ages from 359 Ma to 249 Ma; and (3) Early Cretaceous granitoids, constituting the main stage of granitic magmatism in the area with ages varying from 145 to 120 Ma. This magmatism during this period is also coeval with the immense volume of volcanic rocks exposed in the area [4,26] and hosts various mineralization, including porphyry, epithermal, skarn, hydrothermal, and other types of deposits [15,16,25,27,28].

3. Deposit Geology

3.1. Stratigraphy

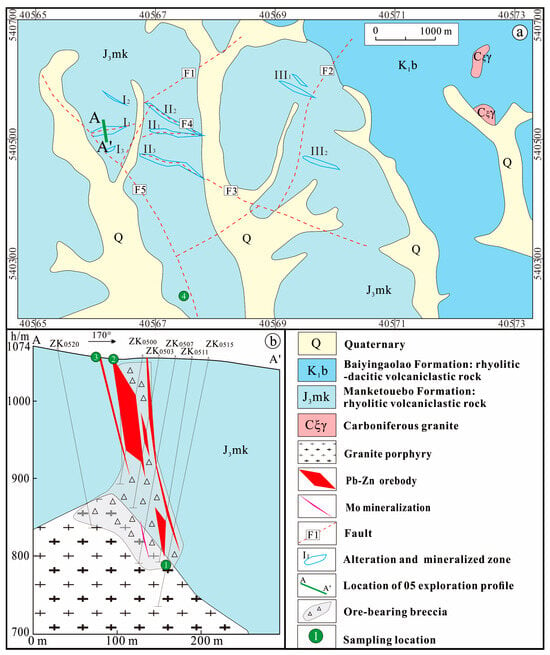

The stratigraphic units consist of the Upper Jurassic Manketouebo Formation (J3mk) and Lower Cretaceous Baiyin’gaolao Formation (K1b) from west to east. Upper Jurassic Manketouebo Formation volcanic–sedimentary rocks are composed of rhyolite, lithic crystal tuff, rhyolitic tuff, and volcanic breccia. Lower Cretaceous Baiyin’gaolao Formation volcanic–sedimentary rocks comprise rhyolite, dacite tuff, and volcanic breccia (Figure 2a), yielding a zircon U-Pb age of rhyolite at 127.6 ± 1.2 Ma [29]. The alteration and mineralization zone is hosted within the Upper Jurassic Manketouebo Formation (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

(a) Geological map of the Wunuer deposit (modified from [19]). (b) Geological section along No. 05 exploration profile, which crosscuts the I1 orebody (modified from [19]).

3.2. Structures

The Wunuer deposit is controlled by the Meiyaogou fault [18], which consists of numerous fault sets with various orientations (Figure 2a): pre-mineralization fault with a set of NE-trending compressive shear faults characteristics (F1–F2); mineralization fault characterized by a set of NWW-trending and nearly WE-trending tensile faults (F3–F4); and post-mineralization fault featured by the NW-trending tensile shear faults (F5). In general, Faults F3 and F4 are the secondary volcanic structural fractures, containing a large amount of tectonic breccia, which provide a major ore-controlling structure channel for the alteration and subsequent mineralization.

3.3. Igneous

The magmatic rocks are not observed in the outcrop at the Wunuer deposit. Drilling has revealed a medium-fine-grained granite porphyritic intrusive body at a depth of about 250 m beneath the I1 ore body (Figure 2b). This granite porphyry is directly associated with the Mo mineralization, characterized by an abundance of molybdenite-bearing quartz veins within the intrusive (Figure 2b). Drilling has also revealed that there is a medium-coarse-grained syenogranite intrusion at a depth of about 650 m beneath the southeast of the I mining section (No. 4 sampling location shown in Figure 2a).

3.4. Orebodies

The Wunuer deposit can be divided into three ore blocks (I, II, III) from west to east (Figure 2a). Ore blocks II and III are mainly associated with zinc–lead–silver mineralization, while Ore block I is primarily characterized by zinc–lead–molybdenum mineralization with the highest level of exploration and showing the most abundant geological phenomena. Based on the available exploration data, the I1 orebody of Ore block I exhibits the best and typical mineralization and the highest grade, making it the most significant rich orebody of the Wunuer deposit. Therefore, this article focuses on the study of the I1 ore body.

The I1 orebody exposures in the Wunuer deposit are approximately 301.7 m long, 4 m wide, with a maximum extension of 281.7 m. They are hosted within the volcanic rocks of the Manketouebo Formation and related to the granite porphyry (Figure 2b). The orebody strikes NE 61–85°, dips 76–86° S, and exhibits a vein shape (Figure 2b). The distribution and shapes of the orebodies in this deposit are controlled by a tensional fault. Drilling has demonstrated that the rich ore is exposed at elevations between 789 and 1064 m above sea level. The maximum thickness of the orebodies is 37.5 m (average 9.4 m).

3.5. Mineralization and Alteration

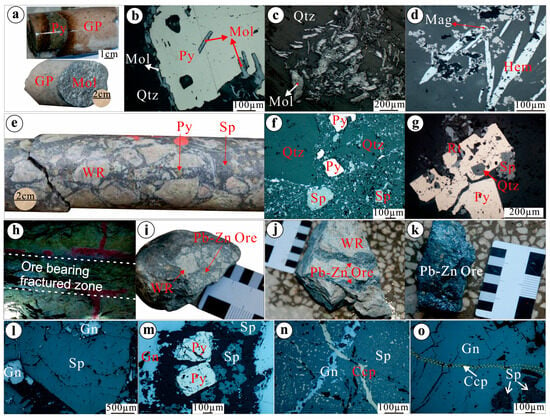

Field investigation, petrographic observations, and replacement relationships indicate a paragenetic sequence during the formation of the Wunuer Pb-Zn-Ag-Mo deposit. The ore mineralogy and associated wall-rock alterations are briefly summarized below, within a framework of three mineralization stages (Figure 3a,e,h and Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Photographs of representative samples from the Wunuer deposit. (a) Hand specimen of granite porphyry with pyrite or molybdenite vein. (b–d) Microphotos of sulfides in the granite porphyry mainly composed of molybdenite, pyrite, hematite, and magnetite. (e) Hand specimen of cryptoexplosive breccia-type Zn-Pb ores hosted by the wall rock (e.g., the Manketouebo Formation volcanic–sedimentary rocks). (f,g) Microphotos of ore-bearing cryptoexplosive breccia composed of pyrite, sphalerite, rutile, and quartz. (h) Field photographs showing the ore-bearing fractured zone. (i–k) Hand specimen of stockwork, vein, and massive Pb-Zn ore from the hydrothermal stage. (l–o) Microphotos of hydrothermal Pb-Zn ore showing the mineral assemblage of sphalerite, galena, pyrite, and chalcopyrite, (b–d,f,g,l–o) reflected light. Abbreviations: GP: granite porphyry, WR: wall rock, Mol: molybdenite, Qtz: quartz, Py: pyrite, Hem: hematite, Mag: magnetite, Sp: sphalerite, Rt: Rutile, Ccp: chalcopyrite, Gn: galena.

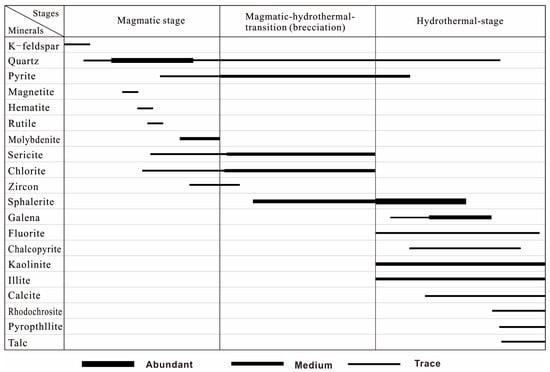

Figure 4.

Paragenetic sequence of ore and alteration minerals in the Wunuer deposit.

Late magmatic stage: mainly occurred at the top of the deep granite porphyry intrusion (Figure 2b), forming vein-type molybdenum ores dominated by pyrite–molybdenite–quartz veins, always with K-feldspathization, silicification, sericitization, chloritization, magnetization, and hematitization (Figure 3a–d). Limited sheet molybdenites were formed in the interior of the pyrite, or anhedral molybdenites replace the pyrite along the edge (Figure 3b).

Magmatic–hydrothermal transition stage: mainly occurred in the cryptoexplosion breccia hosted by granite porphyry intrusion and the volcanic–sedimentary rocks of the Manketouebo Formation (Figure 2b). Breccia-type ore minerals during this stage comprise sphalerite–pyrite–quartz cement and wall rock (the Manketouebo Formation volcanic–sedimentary rocks composed of rhyolite and lithic crystal tuff) breccia (Figure 3e–g). Euhedral pyrite, anhedral sphalerite with minor anhedral rutile crystallized within the breccia body (Figure 3f,g). Major chloritization, sericitization, and silicification are attributed to this stage.

Hydrothermal stage: vein-type Zn-Pb-Ag mineralization located in the ore-bearing fractured zone (Figure 3h) and cross-cutting the crypto-explosive breccia-type mineralization in the shallow position of this deposit (Figure 2b). This stage formed stockwork, veined and massive Zn-Pb-Ag ores principally consisting of sphalerite, galena, chalcopyrite, and pyrite (Figure 3i–k and Figure 4), always with kaolinization, illitization, carbonatation, and fluoritization. Sphalerites include two types: one is an euhedral crystal, coarse-grained with zoned texture, replaced by anhedral galena (Figure 3l); the other is anhedral, fine-grained, often accompanied by chalcopyrite inclusions (Figure 3m), occasionally cut by galena veins (Figure 3n). Galena shows the feature of a black triangular hole, cut by the chalcopyrite veinlet, intergrown with the metasomatic residual sphalerite (Figure 3n,o). Chalcopyrite occurs as veins cross-cutting the earlier galena and sphalerite (Figure 3n,o).

4. Samples and Analytical Methods

4.1. Sample Description

Some representative rocks associated with mineralization, i.e., the granite porphyry, lithic crystal tuff, rhyolite of the Manketouebo Formation, and syenogranite, have been collected at No. 1, 2, 3, and 4 sampling locations shown in Figure 2a,b, within the Wunuer deposit for U-Pb dating and whole-rock geochemistry analysis.

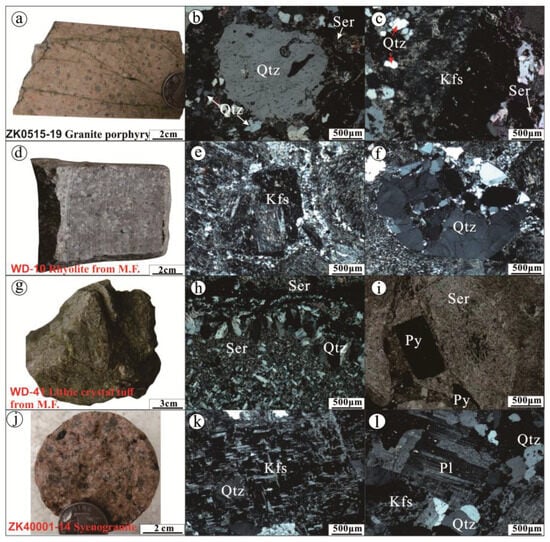

The granite porphyry (sample ZK0515-19) is mostly light flesh-red in color, with medium to fine-grained porphyritic texture (Figure 5a). The phenocrysts mainly consist of 20% quartz (1–3 mm in size), 10% K-feldspar (2–4 mm in size), and 5% plagioclase (0.5–1 mm in size), and the matrix minerals are made up of 35% quartz, 20% K-feldspar, 5% plagioclase, and 5% sericite with occasional accessory minerals (i.e., zircon) (Figure 5b,c). Quartz occurs as subhedral or spherical grains, with a perthitic texture (Figure 5b). K-feldspar mainly occurs as subhedral and short-columnar grains, with well-developed carlsbad twin (Figure 5c). Plagioclase occurs as euhedral to subhedral and commonly altered to sericite (Figure 5b,c).

Figure 5.

(a) Hand specimen of granite porphyry (sample no: ZK0515-19). (b,c) The microphotograph of granite porphyry showing porphyritic texture. (d) Hand specimen of the rhyolite (sample no: WD-10). (e,f) The microphotograph of the rhyolite with the flow structure. (g) Hand specimen of the lithic crystal tuff (sample no: WD-41). (h,i) The microphotograph of the lithic crystal tuff mainly composed of quartz, pyrite, and sericite. (j) Hand specimen of syenogranite (sample no: ZK40001-14). (k)The microphotograph of the syenogranite showing granitic texture. (b,c,e,f,h,i,k,l), crossed polars. Abbreviations: Kfs: K-feldspar, Py: pyrite, Qtz: quartz, Ser: sericite. Pl: plagioclase.

The rhyolite (sample WD-10) of the Manketouebo Formation is gray in color with fine-grained porphyritic texture (Figure 5d). These rocks mainly consist of 10% K-feldspar phenocryst (0.5–3 mm in size), 5% quartz phenocryst (0.5–2 mm in size), and 85% matrix (cryptocrystalline feldspar and quartz) with occasional accessory minerals (i.e., zircon) (Figure 5e,f). The rhyolite shows obvious flow structure, and K-feldspar is euhedral and short-columnar in shape (Figure 5e). The quartz shows subhedral and nearly spheroidal in shape with the obvious cataclastic texture due to late tectonic stress, brittle deformation, and fragmentation (Figure 5f).

The lithic crystal tuff (sample WD-41) of the Manketouebo Formation is gray-green in color with a tuffaceous texture (Figure 5g). This rock mainly includes fine-grained quartz vein (50% in content), sericite (35% in content), and other unknown pyroclastics (10% in content) with occasional accessory minerals (i.e., zircon) (Figure 5h). Occasionally, a small amount of euhedral pyrite (5%) is found in the fine-grained sericite (Figure 5i).

The syenogranite (sample ZK40001-14) occurs as light flesh in color and medium-coarse-grained grain, with a typical granitic texture (Figure 5j). The main components include 55% K-feldspar (2–6 mm in size), 35% quartz (2–4 mm in size), and 10% plagioclase (2–4 mm in size) with occasional accessory minerals (i.e., zircon). K-feldspar primarily consists of orthoclase and microcline, which are euhedral to subhedral and short columnar in shape, with crossed twinning (Figure 5k). Plagioclase shows as euhedral to subhedral and prismatic in shape, with polysynthetic twin (Figure 5l). Quartz shows as anhedral granular particles, filling the interstitial spaces between feldspar grains (Figure 5k,l).

4.2. Zircon U-Pb Dating and Trace Elements

Zircons were separated from the four samples (ZK0515-19, WD-10, WD-41, and ZK40001-14) by combined conventional heavy liquids and magmatic separation techniques; afterwards, euhedral to subhedral zircon grains were handpicked under a binocular microscope. Zircon cathode luminescence (CL) images were obtained at the Wuhan Sample Solution Analytical Technology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China, using an Analytical Scanning Electron Microscope (JSM–IT100) connected to a GATAN MINICL system.

Zircon U-Pb dating and trace element analyses (Tables S1 and S3) were simultaneously conducted by laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) at the Wuhan Sample Solution Analytical Technology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China. Detailed operating conditions for the laser ablation system and the ICP-MS instrument and data reduction are the same as described by [30]. The laser ablating spot size is 32 um for zircon target analysis. Zircon 91500 and glass NIST610 were used as external standards for U-Pb dating and trace element calibration, respectively. Each analysis incorporated a background acquisition of approximately 20–30 s, followed by 50 s of data acquisition from the sample. An Excel-based software, ICPMSDataCal 12.2, was used to perform offline selection and integration of background and analyzed signals, time-drift correction, and quantitative calibration for trace element analysis and U-Pb dating [31]. Concordia diagrams were made using an Excel-based software, Isoplot 4.15 [32].

4.3. Sphalerite Rb-Sr Isochron Age

Seven sphalerite samples from various locations of the No. 997 footrill in the Wunuer deposit were selected for Rb and Sr isotope composition analysis to construct an Rb-Sr isotope isochron age. The sample description is listed in Table S2; typical sphalerite crystals in these samples are shown in Figure 3f,g,l–o.

Rb, Sr abundances and their isotope compositions analyses were conducted at the Center of Modern Analysis, Nanjing University, following the method described by [33]. Sphalerite-bearing samples were ground to 0.3~0.45 mm, and 1 g of pure sphalerite (the purity > 99%) granule was separated via handpicking under a binocular microscope. After being washed by distilled water and dried, a crush-leach procedure using a boron carbide mortar and pestle was performed to water-leach and subsequently remove the fluid inclusion fractions from the crushed sphalerite samples. As the sphalerite may contain many fluid inclusions and we cannot efficiently separate the secondary and primary fluid inclusions, all the sphalerite grains are applicable to dating. Analysis of Rb, Sr abundances, and their isotope compositions was carried out on an automated multi-channel mass spectrometer VG 354, and the isotope dilution method was used for the determination of the abundances. All Sr isotope data are corrected for mass fractionation to 87Sr/86Sr = 0.1194 and reported relative to a value of 87Sr/86Sr = 0.710224 ± 6 (2σ) for NBS987 standard. An Excel-based software, Isoplot 4.15, was used to calculate Rb-Sr isochron age and initial (87Sr/86Sr)i ratio [25].

4.4. Major and Trace Elements Compositions

Based on field investigation and petrographic observations, nineteen fresh and least altered samples were extracted for the major and trace element analysis, including five ore-related granite porphyry, five rhyolite, four lithic crystal tuff, and five syenogranite samples (Table S4).

Whole-rock major and trace element analyses were conducted at the ALS Mineral/ALS Chemex Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China. Major element contents were measured using X-ray fluorescence spectrometry (XRF, Nottm, UK) using fused glass disks with lithium borate. Trace element contents were measured using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). The analytical methods and procedures were as described by [34]. The analytical uncertainty for major elements was better than 1% and for trace elements was better than 10%.

4.5. In Situ Zircon Hf Isotope

Six zircon spots from the granite porphyry (ZK0515-19) and ten zircon spots from the rhyolite (WD-10) of the Manketouebo Formation were chosen for zircon Hf isotope analyses (Table S5). In situ Hf isotopic analyses were conducted on the Zircon U-Pb dating spots, using a Neptune Plus multi-collector (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry in combination with a Geolas HD excimer ArF laser ablation system (MC-LA-ICP-MS) at the State Key Laboratory of Geological Processes and Mineral Resources (GPMR), China University of Geosciences (Wuhan). The analytical spot was 50 μm in diameter. The international zircon standards 91500, GJ-1, and Termora2 were used as the references. Detailed information on these instruments and the analytical procedures can be found in the published literature [35]. Offline selection and integration of analyte signals, and mass bias calibrations were carried out using software, ICPMSDataCal 12.2. For calculations of εHf, we used a decay constant of 1.865 × 10−11 per year for 176Lu [36] and a chondritic model with 176Hf/177Hf = 0.282772 and 176Lu/177Hf = 0.0332 [3].

4.6. In Situ Sulfur Isotope Analysis

Sixteen pyrites and galena spots from the thin-sections have been selected for in situ sulfur isotope analysis (Table S6), using multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry in combination with a Neptune Plus laser ablation system (MC-LA-ICP-MS) at the State Key Laboratory of Geological Process and Mineral Resources, China University of Geosciences (Wuhan), following the methods of [37]. Instruments included a NewWaveTM ArF excimer laser ablation system (up-193fx, 193 nm, Fremont, CA, USA) coupled with a Neptune Plus (Thermo Fisher ScientificTM, Bremen, Germany) multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (MC-ICP-MS). Helium gas was used to transport the ablated materials into the plasma at a gas flow of 0.7 L/min. The argon sample gas (0.85 L/min) was mixed with the carrier gas in a cyclone coaxial mixer before being transported into the ICP torch. The energy fluence of the laser is about 3 J/cm2. For single-spot analysis, the beam diameter is 40 μm with a laser repetition rate of 8 Hz. The precision of 34S/32S analysis is less than 0.00003 (1δ). An in-house pyrite standard named WS-1 was used to calibrate the mass bias for S isotopes.

4.7. Pb Isotope Analysis

Four whole-rock samples from the granite porphyry samples and three galena samples of the hydrothermal stage were selected for lead isotope compositions; the sample types and sampling location are listed in Table S7. Pb isotope compositions were measured by thermal ionization mass spectrometry (TIMS) at the Analytical Laboratory of the Beijing Research Institute of Uranium Geology. Approximately 50 to 60 mg of powder for each sulfide sample was weighed in Teflon crucibles and dissolved in distilled HF + HNO3 at 150 °C for seven days. The lead was separated on Teflon columns using an HBr-HCl wash and an elution procedure. The method blanks were 0.2 ng for Pb. The lead was loaded with a mixture of Si gel and H3PO4 onto a single Re filament and analyzed at 1300 °C. The measured Pb isotope ratios were corrected for instrumental mass fractionation of 0.11% per atomic mass unit by reference to repeated analyses of the NBS-981 Pb standard [38]. Analytical uncertainties were 0.006 for 206Pb/204Pb and 207Pb/204Pb and 0.012 for 208Pb/204Pb.

5. Results

5.1. Geochronology

5.1.1. Zircon U-Pb Dating

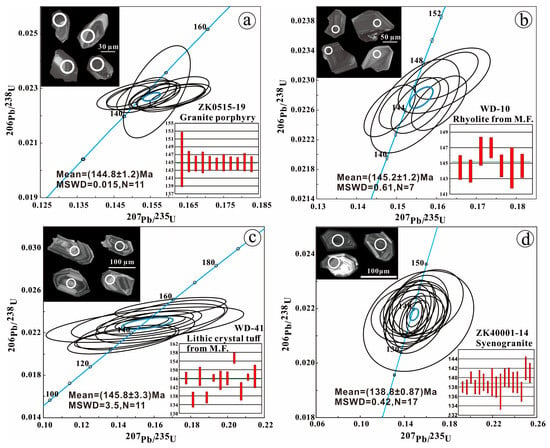

LA-ICP-MS zircon U-Pb analytical data are summarized in Table S1 and shown in Figure 6. All analyzed zircons exhibit no microfractures or inclusions in reflected light and transmitted light micrographs. Zircon grains are mostly colorless to pale, clear, and euhedral–subhedral between 100 and 300 µm in length. These crystals show typical magmatic oscillatory growth zoning under CL images, and high Th/U ratios of 0.48 to 2.62, which is indicative of their magmatic origin [32,39]

Figure 6.

Cathode luminescence (CL) images, zircon U-Pb concordia diagrams, and weighted average diagrams for zircons from the granite porphyry (a), rhyolite (b), lithic crystal tuff (c) of the Manketouebo Formation (M.F.), and syenogranite (d) in the Wunuer deposit.

Eleven spots analyses on zircons from the granite porphyry (ZK0515-19) yielded concordant 206Pb/238U ages ranging from 145 to 146 Ma (Table S1), with a weighted mean age of 144.8 ± 1.2 Ma (MSWD = 0.015; Figure 6a). Seven zircon spots were obtained from the rhyolite sample (WD-10) showing concordant 206Pb/238U ages of 144 to 147 Ma, with a 206Pb/238U-207Pb/235U weighted mean age of 145.2 ± 1.2 Ma (MSWD = 0.61; Figure 6b). Eleven zircon grains from the lithic crystal tuff sample (WD-41) showed concordant 206Pb/238U ages of 136~155 Ma, with a 206Pb/238U-207Pb/235U weighted mean age of 145.8 ± 3.3 Ma (Figure 6c). Seventeen spot analyses on zircons were collected from the syenogranite (ZK40001-14), yielding concordant 206Pb/238U ages ranging from 137 to 142 Ma, with a weighted mean age of 138.8 ± 0.87 Ma (MSWD = 0.42; Figure 6d).

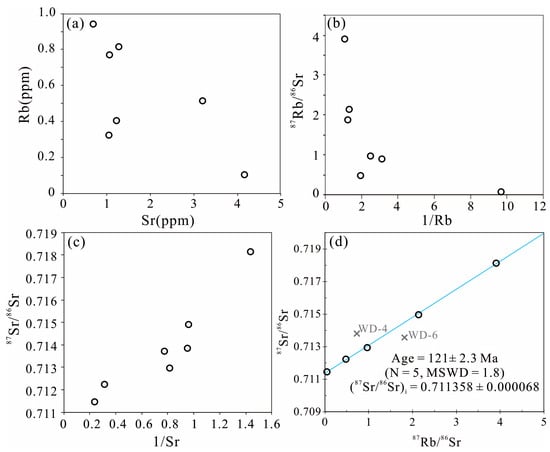

5.1.2. Sphalerite Rb-Sr Isochron Dating

The sphalerite Rb-Sr dating results are listed in Table S2. The Rb and Sr contents of the sphalerite samples are 0.1031~0.9405 ppm and 0.695~4.167 ppm, respectively, and there is no linear correlation between them (Figure 7a). The 87Rb/86Sr and 87Sr/86Sr isotopic ratios of the eight sphalerite samples were distributed in the ranges of 0.0432~3.9080 and 0.71146~0.71813, respectively.

Figure 7.

(a) Rb-Sr isochron age of sphalerite from the Wunuer deposit. (b) Rb vs. Sr diagram. (c) Rb/Sr vs. 87Sr/86Sr diagram. (d) Rb/Sr vs. 87Rb/86Sr diagram.

Furthermore, the 87Rb/86Sr versus 1/Rb and 87Sr/86Sr versus 1/Sr curves are not linear (Figure 7b,c), suggesting the Rb-Sr isochron age was more reliable than non-pseudoisochrons. Figure 7d shows a sphalerite Rb-Sr isochron drawn using the Rb-Sr isotope composition data. The data of the five samples can be observed to fall along a straight line with outliers of two samples (WD-4, WD-6), yielding an isochron age of 121 ± 2.3 Ma (MSWD = 1.8) with (87Sr/86Sr)i = 0.711358 ± 0.000068.

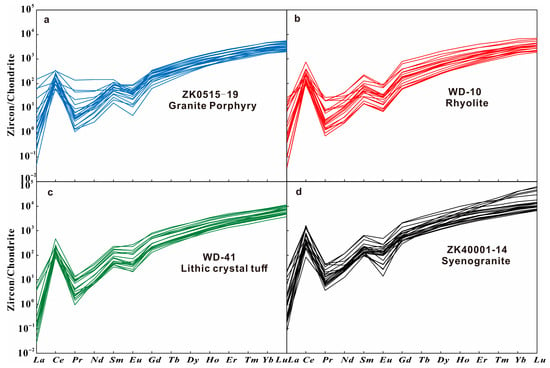

5.2. Zircon Trace Element Compositions

The zircon trace element compositions of the igneous rocks from the Wunuer deposit are summarized in Table S3 and Figure 8. The analytical results reveal that these samples show high total REE contents and are more enriched in high rare earth elements (HREE) relative to light rare earth elements (LREE) (Figure 8). The (La/Yb)N values range from 0.00001 to 0.05 (Table S3). The analyzed zircon grains exhibit strong negative Eu anomalies (δEu = 0.05~0.74) and positive Ce anomalies (δCe = 1.93~458.23).

Figure 8.

Chondrite-normalized REE patterns (a–d) for zircon grains from the igneous rocks in the Wunuer deposit.

5.3. Whole-Rock Geochemistry

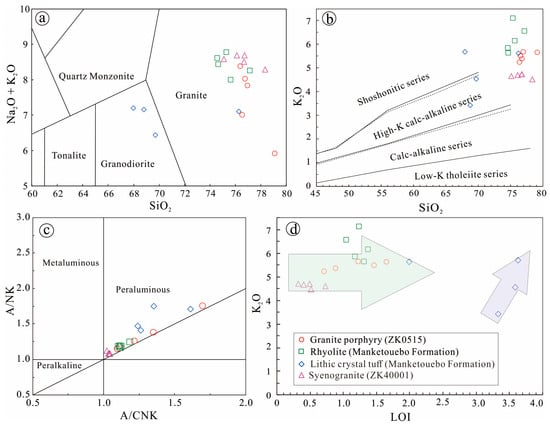

The whole-rock major and trace element compositions of the analyzed data are presented in Table S4. These rocks show high SiO2 (67.98~79.11 wt%) and total alkalis (ALK; Na2O + K2O = 5.92~8.78 wt%), moderate Al2O3 (11.44~14.77 wt%), and relatively low CaO (0.08~1.28 wt%), MgO (0.06~0.80 wt%), TiO2 (0.10~0.40 wt%), and MnO (0.03~1.86 wt%). All these samples are mostly plotted in the granite domains (Figure 9a) on the total alkalis versus silica diagram (TAS), with three lithic crystal tuff samples of Manketouebo Formation belonging to granodiorite, which is likely attributed to hydrothermal alteration (Figure 9d). On the K2O vs. SiO2 diagram, the samples plot within the high-K calc-alkaline and shoshonitic fields (Figure 9b). The analyzed igneous rocks have relatively high aluminum saturation indices (A/CNK, Al2O3/(CaO + Na2O + K2O) molar ratio), mostly in the range of 1.02 to 1.70, indicating peraluminous characteristics in the A/NK vs. A/CNK diagram (Figure 9c). In Zr vs. 10000Ga/Al and (K2O + Na2O)/CaO vs. Zr + Nb + Ce + Y diagrams (Figure 10a,b), most samples fall into the A-type granite field, which is similar to Late Jurassic–Early Cretaceous granites widely distributed in the Great Xing’an Range [22].

Figure 9.

(a) Total alkali–silica (TAS) diagram (after [40]). (b) K2O vs. SiO2 diagram (after [41]). (c) A/CNK vs. A/NK diagram (after [42]). (d) K2O vs. LOI diagram. LOI: loss on ignition. The green and purple arrows represented the trend line of various rocks.

Figure 10.

(a) Zr vs. 10000Ga/Al diagram (after [43]). (b) (K2O + Na2O)/CaO vs. Zr + Nb + Ce + Y diagram (after [43]). (c) Rb vs. Y + Nb diagram (after [44]). (d) Rb vs. Yb + Ta diagram (after [44]). The data of rhyolite of Baiyingaolao Formation are collected from [25]. FG: fractionated granite, OGT: unfractionated M, I, and S-type granites, WPG: within plate granite, VAG: volcanic arc granite, syn-COLG: syn-collision granite, ORG: ocean ridge granite.

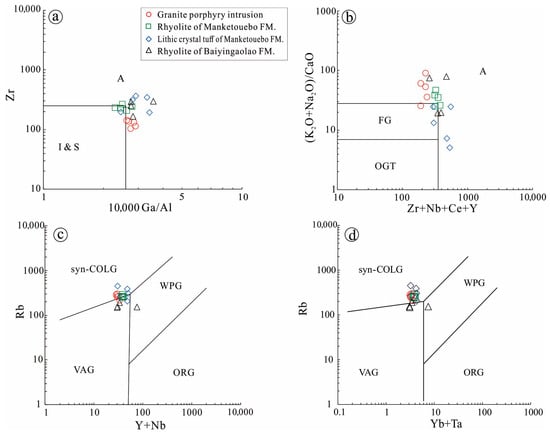

The chondrite-normalized REE diagrams show that the granite porphyry, rhyolite, lithic crystal tuff, and syenogranite have a similarly downward-sloping distribution trend, which is characterized by strong enrichment in LREEs, depletion in HREEs pattern (Figure 11a), with the (La/Yb)N ratios ranging from 7.82 to 15.89 (Table S4), and their chondrite-normalized REE patterns are characterized by significant negative Eu anomalies (δEu = 0.25~0.57; Table S4; Figure 11a). On the primitive mantle-normalized trace element spider diagram (Figure 11b), all samples show enrichment in U, Zr, Hf, and large-ion lithophile elements (LILEs; e.g., Rb), and depletion in Ba, Sr, and high field strength elements (HFSEs; e.g., Nb, P, and Ti).

Figure 11.

(a) Chondrite-normalized rare earth element (REE) patterns for the igneous rocks from the Wunuer deposit (after [45]). (b) Primitive mantle-normalized spider diagrams for the igneous rocks from the Wunuer deposit (after [45]). The gray range represents the data of the metallogenic intrusions in the central Great Xing’an Range (CGXR) (after [27]).

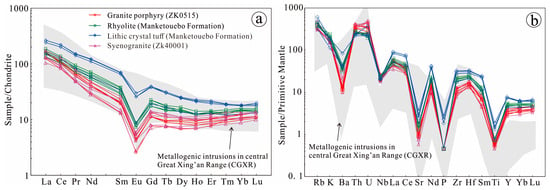

5.4. Hf-S-Pb Isotopic Compositions

In situ Hf isotopic compositions of the granite porphyry and rhyolite from the Manketouebo Formation in the Wunuer deposit are presented in Table S5 and Figure 12. Sixteen zircon spots yield variable Hf isotopic compositions, with initial 176Hf/177Hf ratios of 0.282838 to 0.282974, and positive εHf(t) values of +5.44 to +10.20 (Figure 12a). These correspond to young Hf isotopic crustal model ages (TCDM) ranging from 546 to 852 Ma (Table S5, Figure 12b).

Figure 12.

(a) Zircon Hf isotopes versus U-Pb ages of igneous rocks from the Wunuer deposit (after [22,46]). (b) Histograms of zircon Hf-isotope crust model age (TCDM). The black range represents the data of the volcanic rocks in the central Great Xing’an Range (CGXR) (after [1]). The purple and blue range represents the data of the intrusions in the Great Xing’an Range (GXR) and the easternmost segment of Central Asian Orogenic Belt (East CAOB), respectively (after [27]).

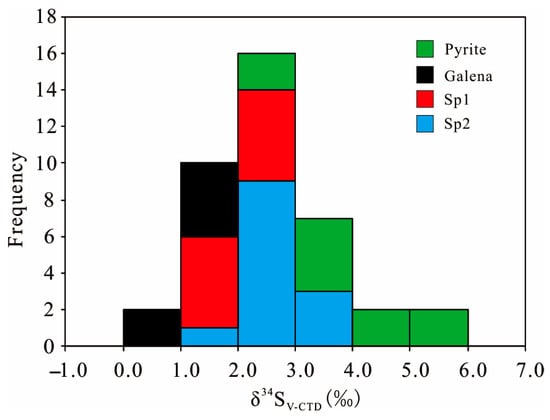

Sulfur isotope compositions of sulfides at the Wunuer deposit, analyzed by the in situ MC-LA-ICP-MS technique, are shown in Table S6 and Figure 13. All the sulfides have concentrated positive sulfur isotope compositions (δ34SV-CDT), with a range of +2.25‰~+5.40‰ for pyrite and a range of +0.17‰~+1.80‰ for galena, respectively (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Histogram of sulfur isotope values of sulfides from the Wunuer deposit. The data of various generations of sphalerite (Sp1 and Sp2) are collected from [19].

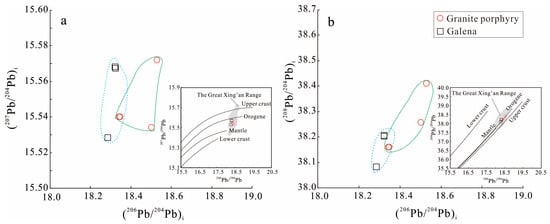

Lead isotope compositions from the Wunuer deposit are shown in Table S7 and Figure 14. Four granite porphyry samples yield 206Pb/204Pb values, 207Pb/204Pb values, and 208Pb/204Pb values of 18.370 to 18.618, 15.538 to 15.576, and 38.192 to 38.557, respectively. Three galena samples have Pb isotope ratios of 206Pb/204Pb from 18.288 to 18.326, 207Pb/204Pb from 15.528 to 15.568, and 208Pb/204Pb from 38.080 to 38.204. Whole-rock Pb isotopes were calibrated to initial ratios based on the GeoKit procedure and intrusion ages of granite porphyry [47]. The calculated (206Pb/204Pb)i, (207Pb/204Pb)i, and (208Pb/204Pb)i ratios for granite porphyry range from 18.343 to 18.529, 15.534 to 15.572, and 38.159 to 38.410, respectively. As shown in Figure 14, the granite porphyry and galena at the Wunuer deposit show relatively consistent lead isotopic compositions, but slightly variable 206Pb/204Pb ratios.

Figure 14.

(a) 206Pb/204Pb vs. 207Pb/204Pb plot. (b) 206Pb/204Pb vs. 208Pb/204Pb plot. The gray range represents the data of the metallogenic intrusions in the Great Xing’an Range (after [27]).

6. Discussion

6.1. Timing of Magmatism and Mineralization

Zircon U-Pb ages of rhyolite (145.2 ± 1.2 Ma) and lithic crystal tuff (145.8 ± 3.3 Ma) of the Manketouebo Formation represent volcanic eruption age, namely, the age of these ore-hosting rocks can be constrained to 145.2~145.8 Ma. Zircon of the granite porphyry intrusion yielded a weighted 206Pb/238U mean age of 144.8 ± 1.2 Ma, interpreted to be its crystallization age, and the earlier magmatic-stage Mo mineralization could be younger than 144.8 Ma. The above geochronological data reveal that the depositional age of the volcanic rocks in the Manketouebo Formation is close to the magmatic age of the granite porphyry, indicating that the metallogenic system belongs to a typical volcanic–subvolcanic system. Zircon U-Pb ages of syenogranite (138.8 ± 0.87 Ma) represent its crystallization age.

Black sphalerite samples collected from breccia-type and vein-type ores have a Rb-Sr isochron age of 121 ± 2.3 Ma, which represents the age of hydrothermal stage mineralization. The zircon U-Pb ages of the Baiyin’gaolao Formation (127.6 ± 1.2 Ma [25]) in the Wunuer area are similar to the Rb-Sr isochron age of sphalerite, suggesting that the Baiyin’gaolao Formation strata are relevant to the hydrothermal stage Zn-Pb-Ag mineralization. The results illustrate that there is a long-time gap from the late magmatic (144.8~145.8 Ma) to the hydrothermal (121 Ma) mineralization stage with an interval of 23 to 24 Ma, which is not caused by the age error. Moreover, mineralization shows spatial zonation from deep to shallow in Figure 2b, e.g., late magmatic stage with vein-type Mo mineralization characteristics and mainly related to the deep granite porphyry, hydrothermal stage with shallow vein-type Zn-Pb-Ag mineralization characteristics and hosted by the ore-bearing fractured zone. Therefore, it is concluded that the Zn-Pb-Ag-Mo metallogenesis is not a simple magmatic–hydrothermal system; it is controlled by two superimposed metallogenic events in this deposit.

In summary, magmatic activity and hydrothermal mineralization are not continuous processes, the Wunuer Zn-Pb-Ag-Mo deposit and adjacent areas underwent three diagenetic and two mineralization event: (1) Late Jurassic to early Cretaceous (144.8~145.8 Ma) diagenetic and mineralization event, including the Manketouebo Formation deposition age and the ore-related granite porphyry intrusion age, and suggesting the Mo mineralization of the late magmatic stage may postdate 144.8 Ma. (2) Early Cretaceous (138.8 Ma) diagenetic event, the syenogranite is not related to the mineralization; therefore, the crystallization age of syenogranite represents another stage of the diagenesis event. (3) Early to middle Cretaceous (121~127.6 Ma) diagenetic and mineralization event, the Zn mineralization (121 ± 2.3 Ma) has a temporal affinity to the Baiyin’gaolao Formation volcanic–sedimentary rocks (127.6 ± 1.2 Ma), which implies that a volcanic–subvolcanic activity most likely provided heat and fluids for hydrothermal Zn-Pb-Ag mineralization.

6.2. The Source of the Metallogenetic Material

Sulfur isotopes are typically derived from deep magmatic sources or water–rock interactions within hydrothermal systems. Consequently, sulfur isotope compositions of sulfide minerals could constrain the sources, transport, and precipitation of metals [48]. The δ34S values of sulfide from the Wunuer deposit display a concentrated range, from 0.17‰ to 5.40‰ (mean = 2.79‰, n = 16), which are in accordance with the granite sulfur reservoirs, suggesting that the magmatic sulfur is dominant [4,25]. The δ34S values of different sulfides showed an increasing trend from galena and sphalerite to pyrite (Figure 13) is attributed to equilibrium sulfur isotope fractionation during mineral crystallization and precipitation [49,50,51]. Based on the geology and fluid feature of the Wunuer deposit, the δ34S value of sulfide minerals could be generally considered as the total sulfur isotope of ore-forming fluid composition [49,52,53], which is similar to that (−9.4‰ to 13.7‰, mean = 1.7‰) of the hydrothermal deposits in the Great Xing’an Range metallogenic belt [25]. Therefore, sulfides precipitated in both magmatic–hydrothermal and hydrothermal stages were derived from a magmatic source.

Lead isotopes generally do not experience significant fractionation during mineralization and hydrothermal processes. Furthermore, common sulfide minerals (e.g., pyrite and galena) contain low U and Th contents, resulting in insignificant production of radiogenic lead. Therefore, the Pb isotopic compositions of these minerals robustly reflect the signature of their source materials [54]. The lead isotope compositions of the galena and ore-related granite porphyry in the Wununer deposit are consistent with those of the metallogenic intrusions in the Great Xing’an Range [27]. Pb isotope compositions of galena from the hydrothermal stage display a concentrated range, which is similar to that of the granite porphyry associated with the mineralization (Figure 14a), suggesting that the granite porphyry intrusion was a potential source of lead and other metals for hydrothermal mineralization. In the 206Pb/204Pb vs. 208Pb/204Pb diagram, all data align along the orogenic evolution line, but the lead isotope ratio of galena is significantly lower than that of granite porphyry intrusion (Figure 14b). This indicates that the ore-forming materials must have been derived primarily from the granite porphyry, but a minor component of lead from the surrounding country rocks.

6.3. Constraint on the Petrogenesis and Tectonic Setting

It is demonstrated that these magmas possess an anorogenic affinity, likely formed in a post-collisional extension setting following the closure of the Mongol-Okhotsk Ocean, combined with back-arc extension associated with the subduction of the Paleo-Pacific plate [22,55]. Moreover, numerous metallic deposits in the Great Xing’an Range are spatially and genetically associated with these A-type granites [12,33,56,57]. The granite porphyry intrusion in the Wunuer deposit also belongs to A-type granite (Figure 10a,b); however, it does not display typical mineralogical features of A-type granitoids due to the lack of dark-colored minerals such as pyroxene, biotite, and hornblende. Geochemically, the analyzed samples are characterized by high SiO2, Rb contents, moderate Al2O3, low CaO contents, and high A/CNK values (>1.0). These features could be the product of high-degree magmatic fractionation, but could also reflect alteration by mineralizing fluids. These rocks also exhibit strong negative Eu, Ba, Sr, P, and Ti anomalies (Figure 11b), indicating fractional crystallization of plagioclase, apatite, and ilmenite or as residual minerals of the magma [58]. Therefore, the igneous rocks in the Wunuer deposit belong to highly fractionated peraluminous A-type granite.

During the Late Jurassic–Early Cretaceous, the Great Xing’an Range underwent intensive tectonic activity, which led to the formation of large-scale volcanic–subvolcanic rocks [43,49]. The tectonic discrimination diagram (Figure 10c,d) implies that the igneous rocks in the Wunuer deposit formed in a post-orogenic extensional setting, which is consistent with previous studies and A-type compositional affinities of the granite porphyry. The igneous rocks from the Wunuer deposit exhibit positive zircon εHf(t) values (Figure 12) and a young TDM2 age (Table S5), suggesting a source of juvenile lower crust that is newly derived from the mantle [59]. In addition, lead isotope data (Figure 14b) imply a minor but discernible contribution from the ancient crustal materials. These geochemistry, Hf, and Pb isotope characteristics are in agreement with most Mesozoic igneous rocks in the Great Xing’an Range zone [32,38]. Thus, we concluded that the igneous rocks in the Wunuer deposit most likely originated from a mantle-derived juvenile component and assimilated by minor ancient crustal material in a post-orogenic extensional setting [22,39].

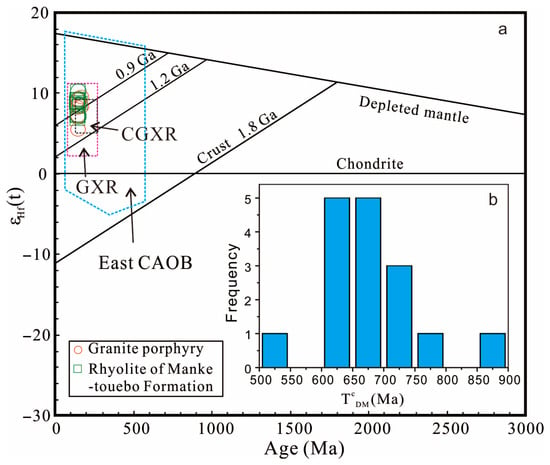

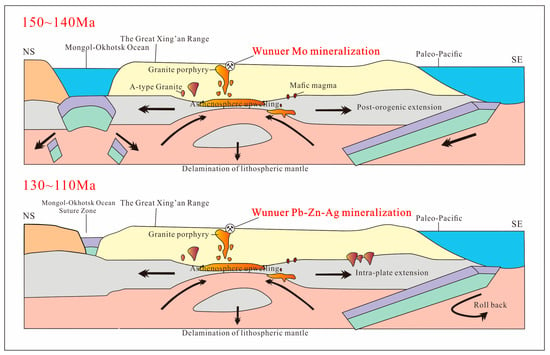

6.4. Implications for REGIONAL Metallogeny

The Yanshanian mineralization, the most prolific metallogenic event in the Great Xing’an Range, is genetically associated with the evolution of the western Mongol-Okhotsk Ocean and the eastern Paleo-Pacific Ocean. Since the Late Jurassic (160~145Ma), the compressive tectonic system caused by the Mongol-Okhotsk Ocean has gradually shifted to the extensional regime, forming a series of large shear faults (e.g., Eerguna shear fault) spreading along the NE direction [31,47]. These faults control the development of numerous metal deposits in the area. The regional tectonic evolution and mineralization are described as follows (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

The tectonic evolution sketch of the Great Xing’an Range.

The Late Jurassic–Early Cretaceous (150~140 Ma) represented a major metallogenic epoch for tin, copper, and lead–zinc deposits in North China. Many studies have shown that the magmatic and related mineralization events in this region were predominantly triggered by the subduction of the Mesozoic Paleo-Pacific Plate [2,4,8,21,48,49,57]. It is generally believed that the large-scale mineralization was associated with lithosphere thinning, resulting from the upwelling of the asthenosphere under a post-orogenic extension tectonic regime in eastern China [4]. A shift in the subduction direction of the Paleo-Pacific Plate from westward to northwestward during the Cretaceous induced a transition from compressional to extensional tectonics and, subsequently, led to large-scale delamination of the thickened lower crust and lithospheric mantle, thus promoting the emplacement of abundant A-type granites [4,50,51]. Therefore, magmatism and metal mineralization in the Great Xing’an Range reached their peak during this period [52,53], forming a series of deposits, including Chalukou Mo deposit (148~144 Ma [54,55]), Huoluotai Cu-Mo deposit (146.75 Ma [56]), Huanggang Fe-Sn deposit (145.3 Ma [33,57]), Bianjiadayuan Ag-Pb-Zn deposit (143~140 Ma [25,33]), Dajing Sn-Cu deposit (144~138 Ma [28,58]), and Wunuer Mo deposit (144.8~145.8 Ma).

During the Late Early Cretaceous (130~110 Ma), the Mesozoic tectonic evolution of NE Asia is characterized by overprinting of the Mongol-Okhotsk and Paleo-Pacific tectonic regimes. It is generally believed that the Mongol-Okhotsk Ocean closed in a “scissor-like” fashion from west to east [60] during the Jurassic [61]. Therefore, the influence of the Paleo-Pacific tectonic domain became dominant. Afterwards, the westward subduction of the Paleo-Pacific plate started to roll back, and large-scale intra-plate extension occurred in the Great Xing’an Range [43,53]. The large-scale magmatic activity and associated metal mineralization were mainly concentrated in the eastern margin of the northern Great Xing’an Range (corresponding to the western margin of the Songliao Basin). Several hydrothermal deposits in this area formed during this tectonic transition period, such as a Sangdaowanzi Au deposit (125.3~116.6 Ma [53]), a Beidagou Au deposit (115.5 Ma [12]), a Shangmacchang Au deposit (113.6 Ma [43]), and a Wunuer Pb-Zn-Ag deposit (121 Ma).

7. Conclusions

The conclusions from this study can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

- In this study, we have identified two mineralization events in the Wunuer Zn-Pb-Ag-Mo deposit: (a) Late Jurassic to early Cretaceous (144.8~145.8 Ma) magmatic and hydrothermal event, including the Manketouebo Formation rhyolite and the lithic crystal tuff, the ore-related granite porphyry, and the Mo mineralization of the late magmatic stage. (b) Early to middle Cretaceous (121~127.6 Ma) diagenetic and mineralization event that is composed of the hydrothermal-stage Zn mineralization and the Baiyin’gaolao Formation volcanic–sedimentary rocks.

- (2)

- The S-Pb isotope compositions of sulfides and granite porphyry intrusion imply a magmatic source of metallogenic materials for the hydrothermal Pb-Zn mineralization. The Hf-Pb isotope characteristics indicated that the granite porphyry intrusion and the Manketouebo Formation volcanic–sedimentary rocks formed simultaneously during Late Jurassic–Early Cretaceous and originated from a mantle-derived juvenile component and assimilated by minor crustal material in an extensional setting.

- (3)

- The Late Jurassic–Early Cretaceous volcanic–subvolcanic rocks were formed in an extensional environment related to the collapse of thickened lithosphere after closure of the Mongol-Okhotsk Ocean. The formation of the late Early Cretaceous volcanic rocks was related to westward subduction of the Paleo-Pacific Plate. This indicated the prospect of further exploration for two mineralization events in the hydrothermal polymetallic deposits of the Great Xing’an Range.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/min15121291/s1, Table S1: U-Pb dating results of zircons from the Wunuer deposit; Table S2: results of Rb-Sr isotope compositions of sphalerite from the Wunuer deposit; Table S3: the trace element compositions of zircons from the Wunuer deposit; Table S4: whole-rock geochemical data of igneous rocks from the Wunuer deposit; Table S5: zircon Hf isotope compositions of zircons from the Wunuer deposit; Table S6: sulfur isotope compositions of sulfides from the Wunuer deposit; Table S7: lead isotope compositions from the Wunuer deposit.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.C.; writing—original draft and writing—review and editing, W.M.; investigation, H.L. and Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially funded by Deep Resources Exploration and Mining, National Science and Technology Major Project of China, grant Number 2025ZD1006003, and Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province, grant Number 2023AFB001.

Data Availability Statement

Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Xiejun Fan and the Sixth Survey and Development Institute of Geology and Mineral in Inner Mongolia for their support of our fieldwork. The two anonymous reviewers are gratefully acknowledged for their constructive and valuable comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, Y.J.; Zhang, C.; Wang, P.; Pirajno, F.; Li, N. The Mo deposits of northeast China: A powerful indicator of tectonic settings and associated evolutionary trends. Ore Geol. Rev. 2017, 81, 602–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Pei, F.; Wang, F.; Meng, E.; Ji, W.; Yang, D.; Wang, W. Spatial–temporal relationships of Mesozoic volcanic rocks in NE China: Constraints on tectonic overprinting and transformations between multiple tectonic regimes. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2013, 74, 167–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blichert-Toft, J.; Albarède, F. The Lu-Hf isotope geochemistry of chondrites and the evolution of the mantle-crust system. Earth Planet Lett. 1997, 148, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.H.; Gao, S.; Ge, W.C.; Wu, F.Y.; Yang, J.H.; Wilde, S.A.; Li, M. Geochronology of the Mesozoic volcanic rocks in the Great Xing’an Range, northeastern China: Implications for subduction-induced delamination. Chem. Geol. 2010, 276, 144–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.H.; Zhao, C.B.; Zhang, F.F.; Liu, J.J.; Wang, J.P.; Peng, R.M.; Liu, B. SIMS zircon U-Pb and molybdenite Re-Os geochronology, Hf isotope, and whole-rock geochemistry of the Wunugetushan porphyry Cu-Mo deposit and granitoids in NE China and their geological significance. Gondwana Res. 2015, 28, 1228–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.Y.; Liu, X.C.; Ji, W.Q.; Wang, J.M.; Yang, L. Highly fractionated granites: Recognition and research. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2017, 60, 1201–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.H.; Zhang, L.L.; Liu, Y.F.; Liu, C.H.; Kang, H.; Wang, F.X. Metallogeny of Xing-Meng Orogenic Belt and some related problems. Miner. Depos. 2018, 37, 671–711. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Mao, J.; Xie, G.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y. Mesozoic large-scale metallogenic pulses in North China and corresponding geodynamic settings. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2005, 21, 169–188. [Google Scholar]

- Song, K.R.; Tang, L.; Zhang, S.T.; Santosh, M.; Spencer, C.J.; Zhao, Y.; Li, H.X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, A.L.; Sun, Y.Q. Genesis of the Bianjiadayuan Pb-Zn polymetallic deposit, Inner Mongolia, China: Constrains from in-situ sulfur isotope and trace element geochemistry of pyrite. Geosci. Front. 2019, 10, 1863–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, D.G.; Williams-Jones, A.E.; Liu, J.J.; Tombros, S.F.; Cook, N.J. Mineralogical, Fluid Inclusion, and Multiple Isotope (H-O-S-Pb) Constraints on the Genesis of the Sandaowanzi Epithermal Au-Ag-Te Deposit, NE China. Econ. Geol. 2018, 113, 1359–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, F.; Wang, S.; Xin, W. Geochronology and geochemistry of Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous granitoids in the northern Great Xing’an Range, NE China: Petrogenesis and implications for late Mesozoic tectonic evolution. Lithos 2018, 312–313, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Zhou, Z.; Breiter, K.; Ouyang, H.; Liu, J. Ore-formation mechanism of the Weilasituo tin-polymetallic deposit, NE China: Constraints from bulk-rock and mica chemistry, He-Ar isotopes, and Re-Os dating. Ore Geol. Rev. 2019, 109, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.H.; Bagas, L.; Hu, P.; Han, N.; Chen, C.L.; Liu, Y.; Kang, H. Zircon U-Pb ages and Sr-Nd-Hf isotopes of the highly fractionated granite with tetrad REE patterns in the Shamai tungsten deposit in eastern Inner Mongolia, China: Implications for the timing of mineralization and ore genesis. Lithos 2016, 261, 322–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, H.; Mao, J.; Zhou, Z.; Su, H. Late Mesozoic metallogeny and intracontinental magmatism, southern Great Xing’an Range, northeastern China. Gondw. Res. 2015, 27, 1153–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, D.; Liu, J.; Zhang, A.; Sun, Y. U-Pb, Re-Os, and 40Ar/39Ar geochronology of porphyry Sn ± Cu ± Mo and polymetallic (Ag-Pb-Zn-Cu) vein mineralization at Bianjiadayuan, Inner Mongolia, northeast China: Implications for discrete mineralization events. Econ. Geol. 2017, 112, 2041–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, D.G.; Williams-Jones, A.E.; Liu, J.J.; Selby, D.; Voudouris, P.C.; Tombros, S.; Li, K.; Li, P.L.; Sun, H.J. The Genesis of the Giant Shuangjianzishan Epithermal AgPb-Zn Deposit, Inner Mongolia, Northeastern China. Econ. Geol. 2020, 115, 101–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.H.; Mao, J.W.; Wu, X.L.; Ouyang, H.G. Geochronology and geochemistry constraints of the Early Cretaceous Taibudai porphyry Cu deposit, northeast China, and its tectonic significance. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2015, 103, 212–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMSG (Inner Mongolia Sixth Geological and Mineral Exploration and Development Co., Ltd.). Detailed Survey Report of Molybdenum, Silver, Lead, and Zinc Deposits on the North Bank of Wunu’er River, Yakeshi City, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region; IMSG: Hohhot, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, X.; Lü, X.; Wang, X. Textural, chemical, isotopic and microthermometric features of sphalerite from the Wunuer deposit, Inner Mongolia: Implications for two stages of mineralization from hydrothermal to epithermal. Geol. J. 2020, 55, 6936–6958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.J.; Windley, B.F.; Hao, J.; Zhai, M.G. Accretion leading to collision and the Permian Solonker suture. Inner Mongolia, China: Termination of the central Asian orogenic belt. Tectonics 2003, 22, 1069–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.Y.; Sun, D.Y.; Ge, W.C.; Zhang, Y.B.; Grant, M.L.; Wilde, S.A.; Jahn, B.M. Geochronology of the Phanerozoic granitoids in northeastern China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2011, 41, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Sun, D.; Li, H.; Jahn, B.; Wilde, S. A-type granites in northeastern China: Age and geochemical constraints on their petrogenesis. Chem. Geol. 2002, 187, 143–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lv, X.; Cheng, C.; Gun, M.; Yang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, L.; Zang, S. Geochronological and geochemical characteristics of the rhyolites in Taerqi of middle Da Hinggan Mountains and their geological significance. Geol. Bull. China 2016, 35, 906–918. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Deng, C.; Sun, D.; Han, J.; Li, G.; Feng, Y.; Xiao, B.; Yang, D. Ages and petrogenesis of the Late Mesozoic igneous rocks associated with the Xiaokele porphyry Cu-Mo deposit, NE China and their geodynamic implications. Ore Geol. Rev. 2019, 107, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Yang, J.; Fan, X.; Wei, W.; Mei, W.; Ruan, B. Geology and Genesis of Lead-Zinc Polymetallic Deposits in the Great Xing’an Range. Earth Sci. 2020, 45, 4399–4427. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Lv, X.B.; Li, J.; Gun, M.C. Petrogenesis and Tectonic Setting of Intermediate-Felsic Volcanics in Ta’erqi Area, Central Great Xing’an Range. Earth Sci. 2020, 45, 4446–4462. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Watanabe, K.; Yonezu, K. Zircon morphology, geochronology and trace element geochemistry of the granites from the Huangshaping polymetallic deposit, South China: Implications for the magmatic evolution and mineralization processes. Ore Geol. Rev. 2014, 60, 14–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M. Metallogenic Epoch of Dajing Copper-Polymetallic Deposit of Inner Mongolia and Discussion of Metallogenic Process. Master’s Thesis, China University of Geosciences, Wuhan, China, 2013. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.Y.; Zhang, C.H.; Han, Y.; Shi, C.L.; Liu, B.; Liu, G.Y. Zircon U-Pb age and geological background of rhyolite from Baiyingaolao Formation in Wunuer area, Great Xing’an Range. Geol. China 2023, 50, 1532–1541. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zong, K.; Klemd, R.; Yuan, Y.; He, Z.; Guo, J.; Shi, X.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, Z. The assembly of Rodinia: The correlation of early Neoproterozoic (ca. 900 Ma) high-grade metamorphism and continental arc formation in the southern Beishan Orogen, southern Central Asian Orogenic Belt (CAOB). Precambrian Res. 2017, 290, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zheng, Y. Mineralogical studies of zircon origin and constraints on the interpretation of U-Pb age. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2004, 49, 1589–1604. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, K.R. Isoplot 3.75: A geochronological toolkit for Microsoft Excel. Berk. Geochronol. Center Spec. Publ. 2012, 5, 1–75. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Xu, D.; Lü, X.; Wei, W.; Mei, W.; Fan, X.; Sun, B. Origin of the Haobugao skarn Fe-Zn polymetallic deposit, Southern Great xing’an range, NE China: Geochronological, geochemical, and Sr-Nd-Pb isotope constraints. Ore Geol. Rev. 2018, 94, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Liu, X.; Yuan, H.; Hattendorf, B.; Günther, D.; Chen, L.; Hu, S. Determination of Forty Two Major and Trace Elements in USGS and NIST SRM Glasses by Laser Ablation-Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry. Geostand. Newslett. 2002, 26, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Gao, S.; Liu, W.; Zhang, W.; Tong, X.; Yang, L. Improved in situ Hf isotope ratio analysis of zircon using newly designed X skimmer cone and jet sample cone in combination with the addition of nitrogen by laser ablation multiple collector ICP-MS. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2012, 27, 1391–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, E.; Munker, C.; Mezger, K. Calibration of the lutetium-hafnium clock. Science 2001, 293, 683–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Jiang, S.; Ciobanu, C.L.; Yang, T.; Cook, N.J. Sulfur isotope fractionation in pyrite during laser ablation: Implications for laser ablation multiple collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry mapping. Chem. Geol. 2017, 450, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todt, W.; Cliff, R.A.; Hanser, A.; Hofmann, A.W. Evaluation of a 202Pb-205Pb double spike for high-precision lead isotope analysis. Am. Geophys. Union. Geophys. Monogr. 1996, 95, 429–437. [Google Scholar]

- Belousova, E.A.; Griffin, W.L.; O’Reilly, S.Y.; Fisher, N.L. Igneous zircon: Trace element composition as an indicator of source rock type. Contrib. Miner. Petrol. 2002, 143, 602–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middlemost, E.A.K. Naming materials in the magma/igneous rock system. Earth Sci. Rev. 1994, 37, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollinson, H.R. Using Geochemical Data: Evaluaiton, Presentation Interdretation; Longman Scientific & Technical: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 1–352. [Google Scholar]

- Maniar, P.D.; Piccoli, P.M. Tectonic discrimination of granitoids. Geol. Society of Am. Bull. 1989, 101, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalen, J.B.; Currie, K.L.; Chappell, B.W. A-type granites: Geochemical characteristics, discrimination and petrogenesis. Contrib. Mineral. Petr. 1987, 95, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.A.; Harris, N.B.W.; Tindle, A.G. Trace Element Discrimination Diagrams for the Tectonic Interpretation of Granitic Rocks. J. Petrol. 1984, 25, 956–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, W.F.; Sun, S.S. The composition of the Earth. Chem. Geol. 1995, 120, 223–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlik, M.; Raith, J.G.; Gerdes, A. U-Pb, Lu-Hf and trace element characteristics of zircon from the Felbertal scheelite deposit (Austria): New constraints on timing and source of W mineralization. Chem. Geol. 2016, 421, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.F. GeoKit—A geochemical toolkit for Microsoft Excel. Geochimica 2004, 33, 459–464. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, G.; Xia, B.; Xiao, Z.; Yu, H.; Wang, H.; Zhong, Z.; Wang, G. The characteristics of epithermal hydrothermal deposit and its prospecting direction. Geol. Resour. 2001, 10, 165–171. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Cheng, J. Stable Isotope Geochemistry; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2000; pp. 1–316. [Google Scholar]

- Ohmoto, H. Sulfur and Carbon Isotopes. In Geochemistry of Hydrothermal Ore Deposits, 3rd ed.; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 517–612. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, T.; Zhang, C.; Wan, D.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, G. Experimental calibration of sulfur isotope geothermometers for sphalerite-galena. Acta Geol. Sin. 2003, 37, 1392. [Google Scholar]

- Ridley, J.; Diamond, L. Fluid chemistry of orogenic lode gold deposits and implications for genetic models. Hagemann S G and Brown P E. Gold in 2000. Boulder Colo. Soc. Econ. Geol. 2000, 13, 141–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmoto, H. Systematics of sulfur and carbon isotopes in hydrothermal ore deposits. Econ. Geol. 1972, 67, 551–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Hu, R.; Bi, X.; Peng, J.; Tang, Q. A review on the sources of ore-forming materials traced by lead isotopes in ores. Geol. Geochim. 2002, 31, 73–81. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S.; Chen, C.; Bagas, L.; Liu, Y.; Han, N.; Kang, H.; Wang, Z. Two mineralization events in the Baiyinnuoer zn-pb deposit in Inner Mongolia, China: Evidence from field observations, S-Pb isotopic compositions and U-Pb zircon ages. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2017, 144, 339–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, B.; Lü, X.; Yang, W.; Liu, S.; Yu, Y.; Wu, C.; Adam, M.M.A. Geology, geochemistry and fluid inclusions of the Bianjiadayuan Pb-Zn-Ag deposit, Inner Mongolia, NE China: Implications for tectonic setting and metallogeny. Ore Geol. Rev. 2015, 71, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q. What drove late Mesozoic extension of the northern China-Mongolia tract? Tectonophysics 2003, 369, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Mao, J.; Lyckberg, P. Geochronology and isotope geochemistry of the A-type granites from the Huanggang Sn-Fe deposit, southern Great Hinggan Range, NE China: Implication for their origin and tectonic setting. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2012, 49, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, Z.; Gao, S.; Günther, D.; Xu, J.; Gao, C.; Chen, H. In situ analysis of major and trace elements of anhydrous minerals by LA-ICP-MS without applying an internal standard. Chemical Geol. 2008, 257, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Tong, Y.; Xiao, W. Rollback, scissor-like closure of the Mongol-Okhotsk Ocean and formation of an orocline: Magmatic migration based on a large archive of age data. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2022, 9, nwab210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhang, X.; Tang, J. Late Mesozoic stratigraphic framework of the Great Xing’an Range, NE China, and overprinting by the Mongol–Okhotsk and Paleo-Pacific tectonic regimes. Gondwana Res. 2024, 134, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).