Basalts from Zhangzhongjing Seamount, South China Sea and Their Linkage to a Plume-Modified Mantle Reservoir

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Geological Setting

3. Sampling and Petrography

3.1. Sampling

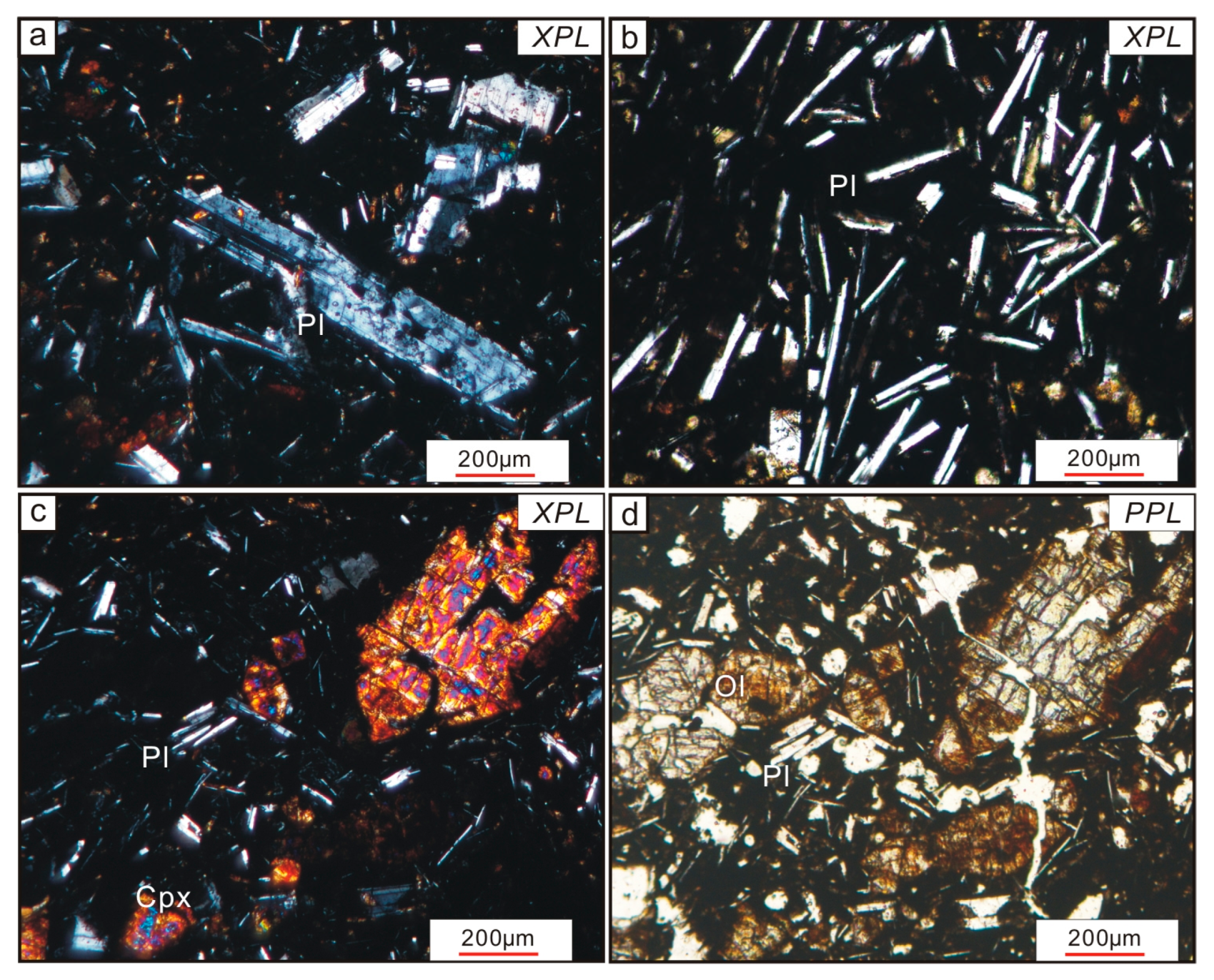

3.2. Petrography

4. Methods and Results

4.1. Analytical Methods

4.2. Results

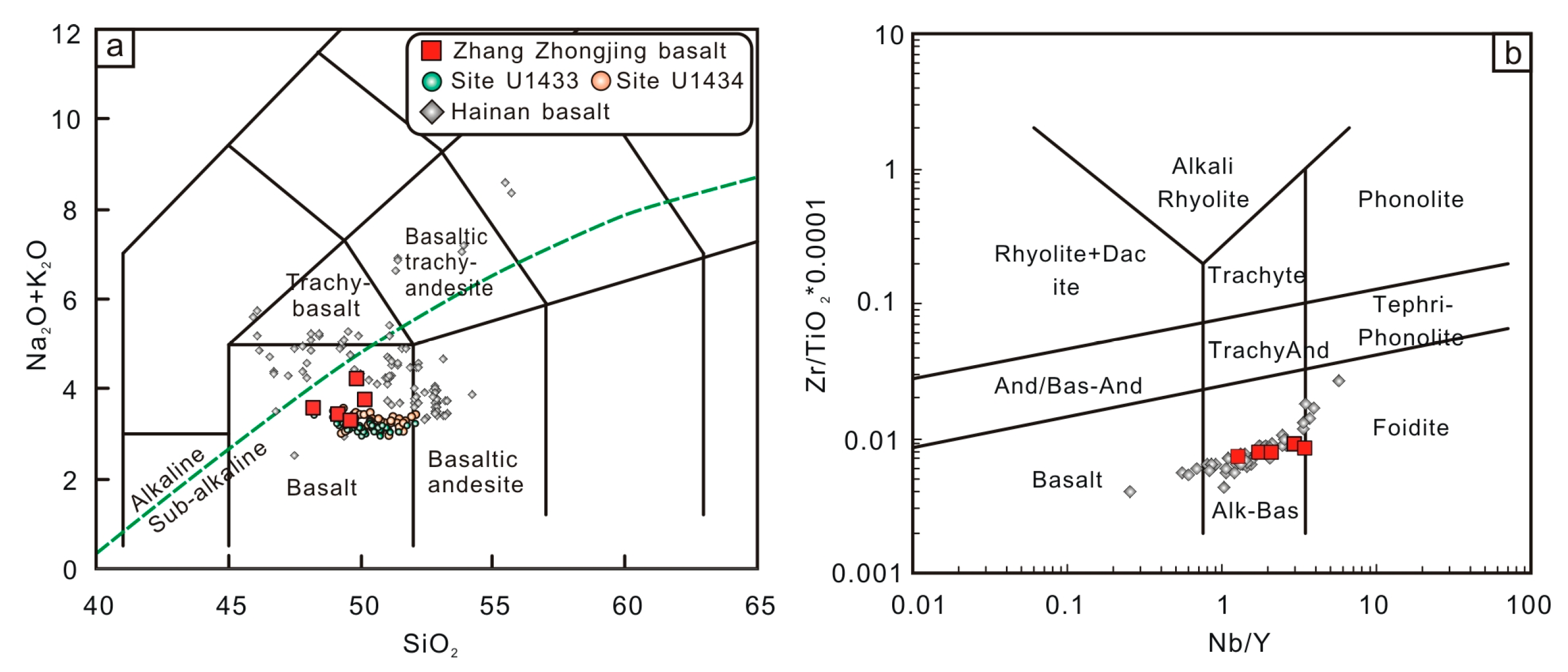

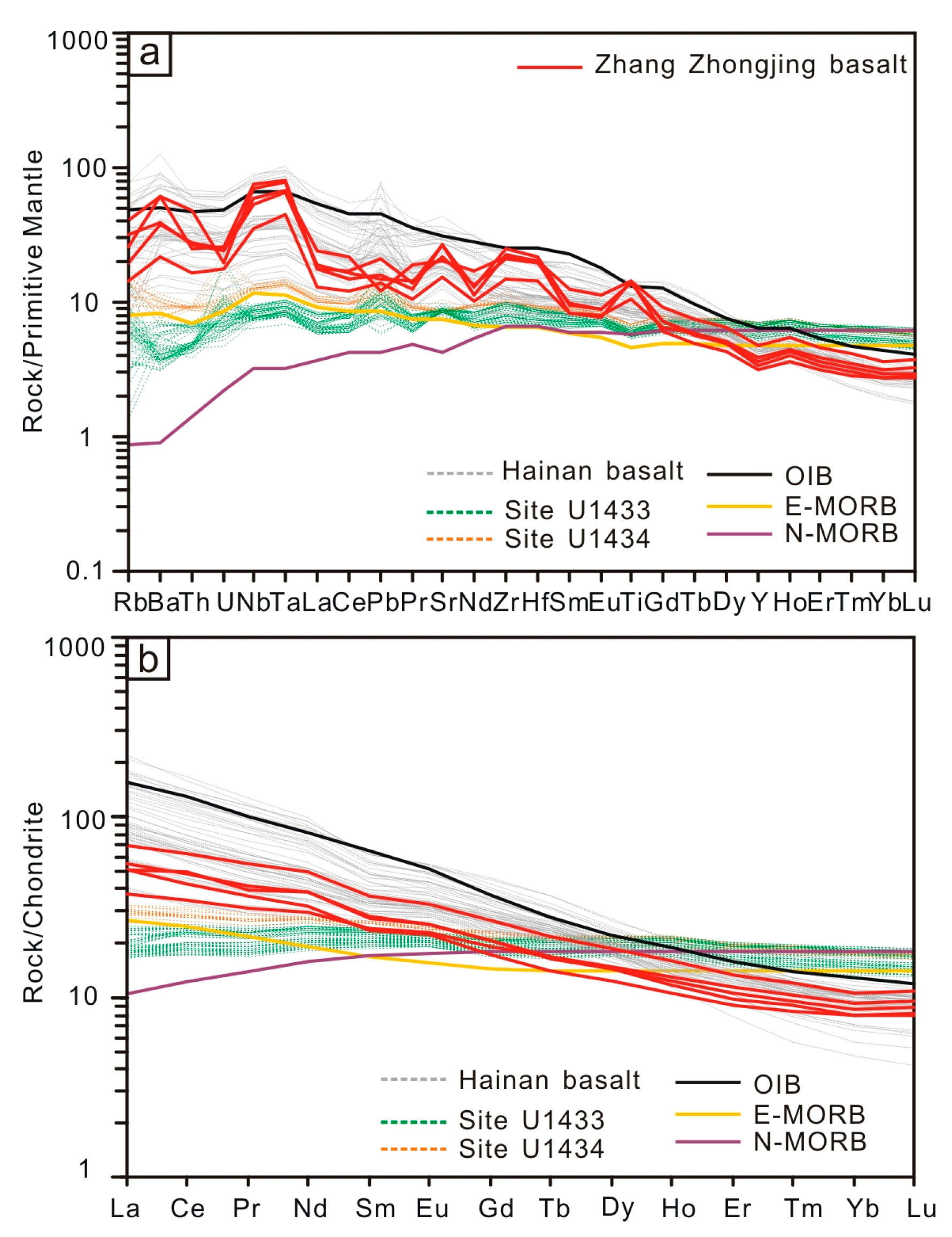

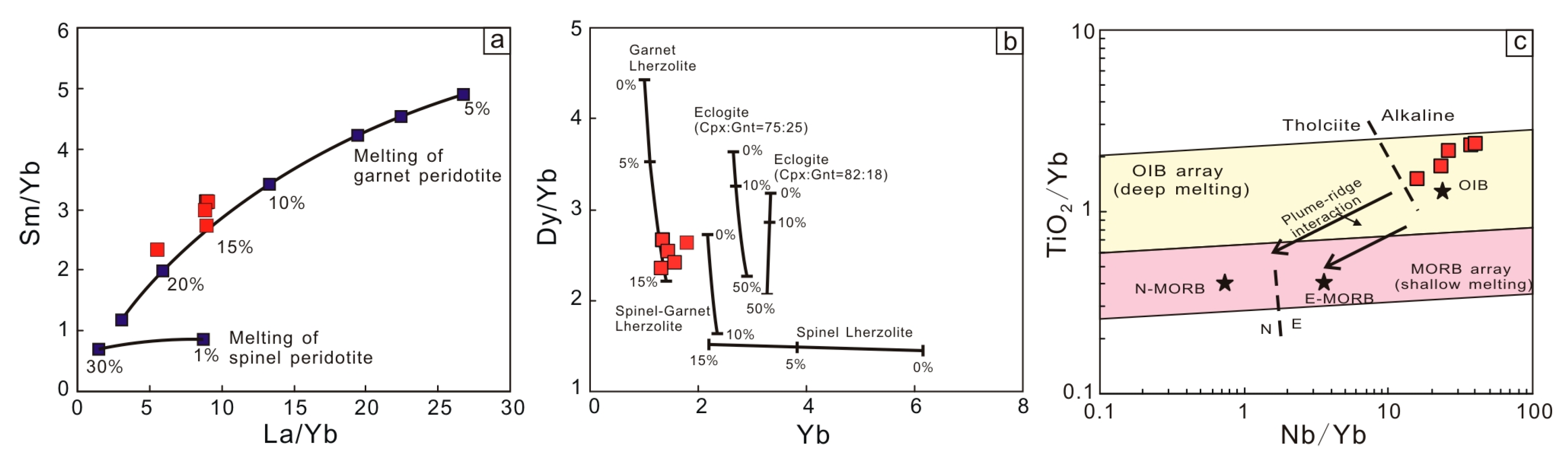

4.2.1. Major and Trace Element Analysis

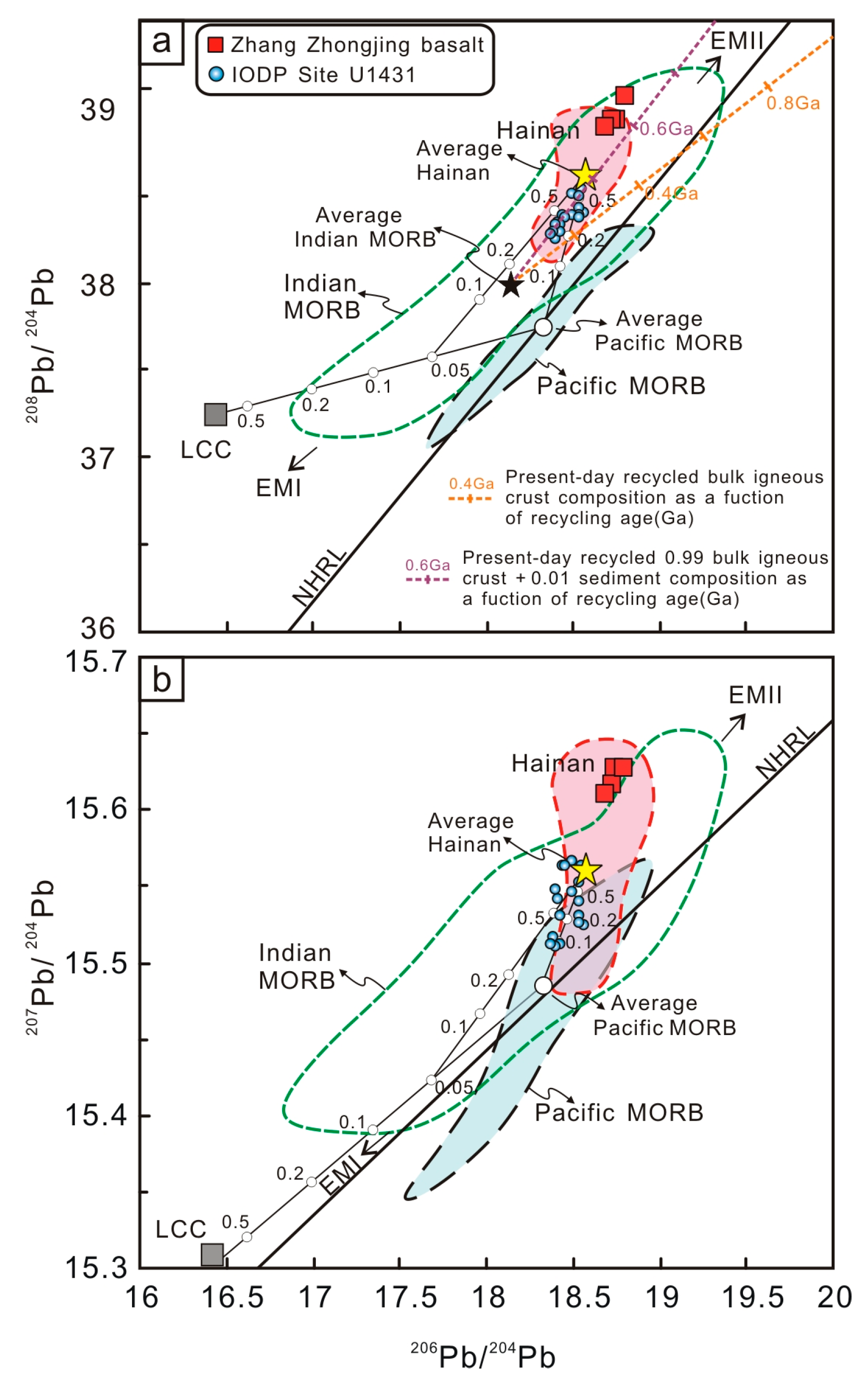

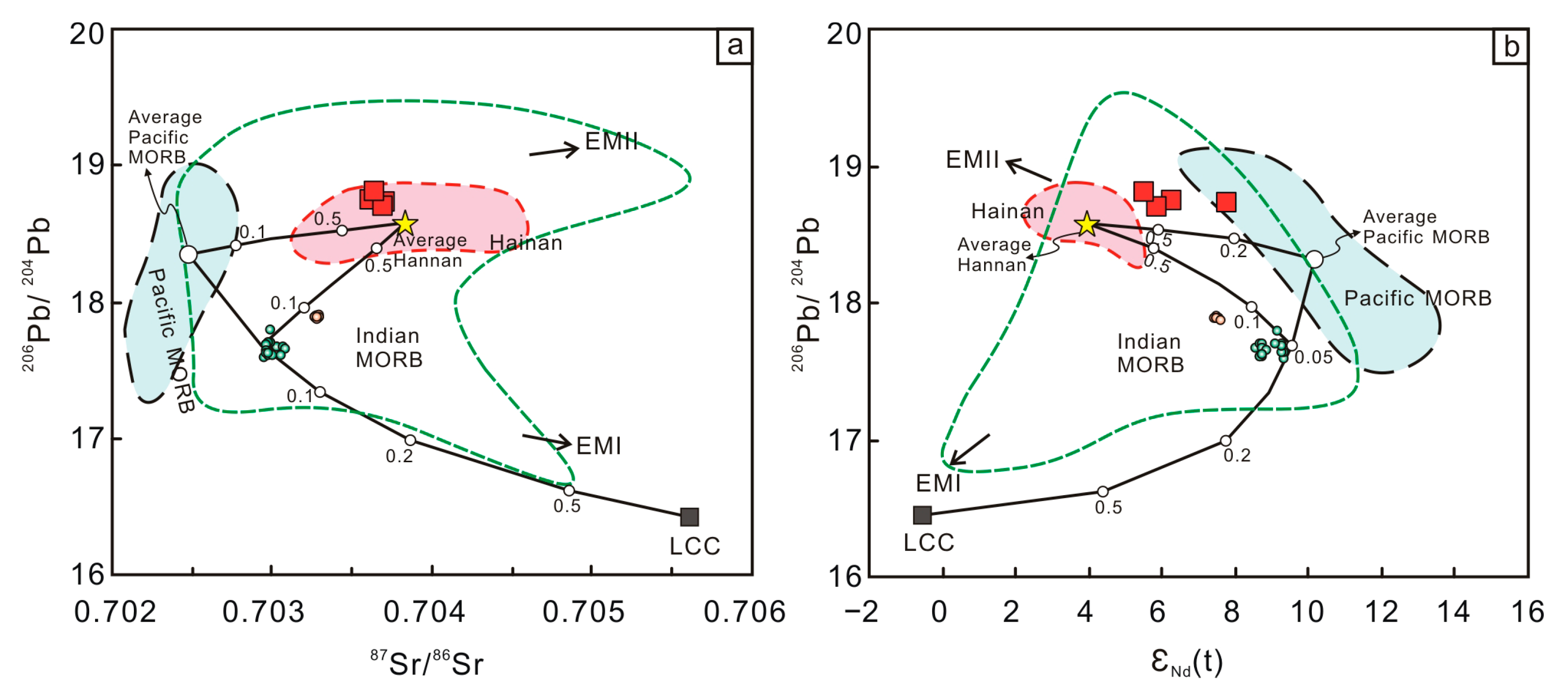

4.2.2. Sr-Nd-Hf-Pb Isotope Systematics

5. Discussion

5.1. Potential Effects of Post-Solidification Alteration, Fractionation and Crustal Assimilation

5.2. Insights into the Origin of the EM-Signature—Implications for Mantle Heterogeneity

5.3. Evidence for a Plume-Modified Mantle Reservoir

5.4. Petrotectonic Implications

6. Conclusions

- Basalts from the Zhangzhongjing seamount of the SCS exhibit geochemical signatures consistent with E-MORB-to-OIB-type rocks.

- The Sr-Nd-Pb-Hf isotopic compositions of basalts suggest that they originated from melting of an Indian Ocean-type mantle source that had been contaminated with components derived from the Hainan plume.

- Our study improves our knowledge about the effect of the Hainan plume on the composition of the upper mantle beneath the East Sub-basin of the SCS.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hofmann, A.W.; Jochum, K.P.; Seufer, M.; White, W.M. Nb and Pb inoceanic basalts: New constraints on mantle evolution. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1986, 79, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamori, H.; Nakamura, H. East-west mantle geochemical hemispheres constrained from Independent Component Analysis of basalt isotopic compositions. Geochem. J. 2012, 46, e39−e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agranier, A.; Blichert-Toft, J.; Graham, D.; Debaille, V.; Schiano, P.; Albarède, F. The spectra of isotopic heterogeneities along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2005, 238, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waight, T.E.; Baker, J.A. Depleted Basaltic Lavas from the Proto-Iceland Plume, Central East Greenland. J. Petrol. 2012, 53, 1569−1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupré, B.; Allègre, C.J. Pb-Sr isotope variation in Indian Ocean basalts and mixing phenomena. Nature 1983, 303, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukasa, S.B.; McCabe, R.; Gill, J.B. Pb-isotopic compositions of volcanic rocks in the West and East Philippine island arcs: Presence of the Dupal isotopic anomaly. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1987, 84, 153−164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flower, M.; Tamaki, K.; Hoang, N. Mantle extrusion: A model for dispersed volcanism and DUPAL-Like Asthenosphere in East Asia and the Western Pacific. Mantle Dyn. Plate Interact. East Asia 1998, 27, 67–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hickey-Vargas, R. Origin of the Indian Ocean-type isotopic signature in basalts from Philippine Sea plate spreading centers: An assessment of local versus large-scale processes. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1998, 103, 20963–20979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.S.; Shi, X.F.; Wang, K.S.; Bu, W.R.; Xiao, L. Major element, trace element, Sr-Nd-Pb isotopic studies of Cenozoic alkali basalts from the South China Sea. Sci. China Ser. D Earth Sci. 2008, 51, 550–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, T.; Kimura, J.I.; Senda, R.; Vaglarov, B.S.; Chang, Q.; Takahashi, T.; Hirahara, Y.; Hauff, F.; Hayasaka, Y.; Sano, S.; et al. Missing western half of the Pacific Plate: Geochemical nature of the Izanagi-Pacific Ridge interaction with a stationary boundary between the Indian and Pacific mantles. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2015, 16, 3309–3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.L.; Luo, Q.; Zhao, J.; Jackson, M.G.; Guo, L.S.; Zhong, L.F. Geochemical nature of sub-ridge mantle and opening dynamics of the South China Sea. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2018, 489, 145−155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, K.; Flower, M.F.; Carlson, R.W.; Xie, G.; Chen, C.Y.; Zhang, M. Magmatism in the South China Sea basin: 1. Isotopic and trace element evidence for an endogenous Dupal mantle component. Chem. Geol. 1992, 97, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chu, F.; Wu, X.; Li, Z.; Chen, L.; Li, X.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, J. Constraining Mantle Heterogeneity beneath the South China Sea: A New Perspective on Magma Water Content. Minerals 2019, 9, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Zhong, L.-F.; Kapsiotis, A.; Cai, G.-Q.; Wan, Z.-F.; Xia, B. Post-spreading Basalts from the Nanyue Seamount: Implications for the Involvement of Crustal- and Plume-Type Components in the Genesis of the South China Sea Mantle. Minerals 2019, 9, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.C.; Li, Z.X.; Li, X.H.; Li, J.; Xu, Y.G.; Li, X.H. Identification of an ancient mantle reservoir and young recycled materials in the source region of a young mantle plume: Implications for potential linkages between plume and plate tec-tonics. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2013, 377, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.C.; Li, Z.X.; Li, X.H.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Long, W.G.; Zhou, J.-B.; Wang, F. Temperature, pressure, and composition of the mantle source region of Late Cenozoic basalts in Hainan Island, SE Asia: A consequence of a young thermal mantle plume close to subduction zones? J. Petrol. 2012, 53, 177–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, A.; Choi, S.; Yu, Y.; Lee, D. Petrogenesis of Late Cenozoic basaltic rocks from southern Vietnam. Lithos 2017, 272–273, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Li, C.F. Mesozoic and early Cenozoic tectonic convergence-to-rifting transition prior to opening of the South China Sea. Int. Geol. Rev. 2012, 54, 1801–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.F.; Xu, X.; Lin, J.; Sun, Z.; Zhu, J.; Yao, Y.J.; Zhao, X.X.; Liu, Q.S.; Kulhanek, D.K.; Wang, J.; et al. Ages and magnetic structures of the South China Sea constrained by deep tow magnetic surveys and IODP Expedition 349. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2014, 15, 4958–4983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibuet, J.C.; Yeh, Y.C.; Lee, C.S. Geodynamics of the South China Sea. Tectonophysics 2016, 692, 98–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Xia, S.; Zhao, F.; Sun, J.; Cao, J.; Xu, H.; Wan, K. New insights into the magmatism in the northern margin of the South China Sea: Spatial features and volume of intraplate seamounts. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2017, 18, 2216–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Qiu, Y.; Zhu, B. (Eds.) Atlas of Geology and Geophysics of the South China Sea; China Navigation Publication House Press: Tianjin, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Le Bas, M.J.; Le Maitre, R.W.; Streckeisen, A.; Zanettin, B. A chemical classification of volcanic rocks based on the total alkali-silica diagram. J. Petrol. 1986, 27, 745–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winchester, J.A.; Floyd, P.A. Geochemical discrimination of different magma series and their differentiation products using immobile elements. Chem. Geol. 1977, 20, 325–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, T.N.; Baragar, W.R.A. A Guide to the Chemical Classification of the Common Volcanic Rocks. Can. J. Earth Sci. 1971, 8, 523−548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.S.; McDonough, W.F. Chemical and isotopic systematics of oceanic basalts: Implications for mantle composition and processes. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 1989, 42, 313–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro, G.; Bourdon, B. Non-chondritic Sm/Nd ratio in the terrestrial planets: Consequences for the geochemical evolution of the mantle-crust system. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2010, 74, 3333–3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, A.; Dalton, C.A.; Langmuir, C.H.; Su, Y.; Schilling, J.G. The mean composition of ocean ridge basalts. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2013, 14, 489–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.W.; Xiong, X.L.; Zhu, Z.Y. Geochemistry of late-Cenozoic basalts from Leiqiong area: The origin of EM2 and the contribution from sub-continental lithosphere mantle. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2009, 25, 3208–3220, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zou, H.; Fan, Q. U-Th isotopes in Hainan basalts: Implications for sub-asthenospheric origin of EM2 mantle endmember and the dynamics of melting beneath Hainan Island. Lithos 2010, 116, 145−152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Yan, Q.; Chen, Z.; Shi, X. Geochemistry and petrogenesis of Quaternary volcanism from the islets in the eastern Beibu Gulf: Evidence for Hainan plume. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2013, 32, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.R. A large-scale isotope anomaly in the Southern Hemisphere mantle. Nature 1984, 309, 753–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnick, R.L.; Fountain, D.M. Nature and composition of the continental crust: A lower crustal perspective. Rev. Geophys. 1995, 33, 267–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zindler, A.; Hart, S. Chemical geodynamics. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 1986, 14, 493–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saccani, E.; Allahyari, K.; Beccaluva, L.; Bianchini, G. Geochemistry and petrology of the Kermanshah ophiolite (Iran): Implication for the interaction between passive rifting, oceanic accretion, and OIB-type components in the Southern Neo-Tethys Ocean. Gondwana Res. 2013, 24, 392–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Shi, X.; Metcalf, I.; Liu, S.; Xu, T.; Kornkanitnan, N.; Sirichaiseth, T.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H. Hainan mantle plume produced late Cenozoic basaltic rocks in Thailand, Southeast Asia. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Castillo, P.; Shi, X.; Wang, L.; Liao, L.; Ren, J. Geochemistry and petrogenesis of volcanic rocks from Daimao Seamount (South China Sea) and their tectonic implications. Lithos 2015, 218, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Straub, S.; Shi, X. Hafnium isotopic constraints on the origin of late Miocene to Pliocene seamount basalts from the South China Sea and its tectonic implications. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2019, 171, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieffer, B.; Arndt, N.; Lapierre, H.; Bastien, F.; Bosch, D.; Pecher, A.; Yirgu, G.; Ayalew, D.; Weis, D.; Jerram, D.A.; et al. Flood and shield basalts from Ethiopia: Magmas from the African Superswell. J. Petrol. 2004, 45, 793−834. [Google Scholar]

- Rudnick, R.L.; Gao, S. Composition of the continental crust. Treatise Geochem. 2003, 3, 1−64. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, J.P.; Bohrson, W.A. Shallow-Level Processes in Ocean-island Magmatism: Editorial. J. Petrol. 1998, 39, 799−801. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, J.A. Geochemical fingerprinting of oceanic basalts with applications to ophiolite classification and the search for Archean oceanic crust. Lithos 2008, 100, 14–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borisova, A.Y.; Faure, F.; Deloule, E.; Grégorie, M.; Béjina, F.; De Parseval, P.; Devidal, J.-L. Lead isotope signatures of Kerguelen plume-derived olivine-hosted melt inclusions: Constraints on the ocean island basalt petrogenesis. Lithos 2014, 198−199, 153−171. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, H.; Reid, M.R.; Liu, Y.; Yao, Y.; Xu, X.; Fan, Q. Constraints on the origin of historic potassic basalts from northeast China by U-Th disequilibrium data. Chem. Geol. 2003, 200, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.K.; Choi, S.H.; Lee, D.-C. Sr-Nd-Hf-Pb isotope geochemistry of basaltic rocks from the Cretaceous Gyeongsang Basin, South Korea: Implications for basin formation. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2013, 73, 504–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.G.; Ma, J.L.; Frey, F.A.; Feigenson, M.D.; Liu, J.F. Role of lithosphere asthenosphere interaction in the genesis of quaternary alkali and tholeiitic basalts from Datong, Western North China Craton. Chem. Geol. 2005, 224, 247–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, D.M. Trace element fractionation during anatexis Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1970, 34, 237−243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, D.; O’Nions, R.K. Partial melt distributions from inversion of rare earth element concentrations. J. Petrol. 1991, 32, 1021–1091. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, K.T.M.; Dick, H.J.B.; Shimizu, N. Melting in the oceanic upper mantle: An ion microprobe study of diopsides in abyssal peridotites. J. Geophys. Res. 1990, 95, 2661–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, M.J. Melting of garnet peridotite and the origin of komatiite and depleted lithosphere. J. Petrol. 1998, 39, 29–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kinzler, R.J. Melting of mantle peridotite at pressures approaching the spinel to garnet transition: Application to mid-ocean ridge basalt petrogenesis. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1997, 102, 853–874. [Google Scholar]

- Workman, R.K.; Hart, S.R. Major and trace element composition of the depleted MORB mantle (DMM). Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2005, 231, 53−72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.G.; Wei, J.X.; Qiu, H.N.; Zhang, H.N.; Huang, X.L. Opening and evolution of the South China Sea constrained by studies on volcanic rocks: Preliminary results and a research design. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2012, 57, 3150–3164. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M.; Yan, Y.; Huang, C.Y.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Z.; Chen, W.H.; Santosh, M. Opening of the South China Sea and upwelling of the Hainan plume. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2018, 45, 2600–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, K.; Flower, M.F.J.; Carlson, R.W.; Zhang, M.; Xie, G. Sr, Nd, and Pb isotopic compositions of Hainan basalts (south China): Implications for a sub-continental lithosphere Dupal source. Geology 1991, 19, 567–569. [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe, I. Tectonic framework and Phanerozoic evolution of Sundaland. Gondwana Res. 2011, 19, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S.; Yeh, Y.; Doo, W.; Tsai, C. New bathymetry and magnetic lineations identifications in the northernmost South China Sea and their tectonic implications. Mar. Geophys. Res. 2004, 25, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; He, E.; Sibuet, J.C.; Sun, L.; Qiu, X.; Tan, P.; Wang, J. Postseafloor spreading volcanism in the central East South China Sea and its formation through an extremely thin oceanic crust. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2018, 19, 621–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Huang, X.-L.; Xu, Y.-G.; He, P.-L. Plume-ridge interaction in the South China Sea: Thermometric evidence from Hole U1431E of IODP Expedition 349. Lithos 2019, 324−325, 466−478. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, H.B.; Zindler, A.; Xu, X.S.; Qi, Q. Major, trace element, and Nd, Sr and Pb studies of Cenozoic basalts in SE China: Mantle sources, regional variations, and tectonic significance. Chem. Geol. 2000, 171, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, W.M.; Albarede, F.; Telouk, P. High-precision analysis of Pb isotope ratios by multi-collector ICP-MS. Chem. Geol. 2000, 167, 257–270. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, R.; Zheng, H.; Yang, L.; Xie, A.; He, X.; Peng, C.; Li, Z.; He, H. Basalts from Zhangzhongjing Seamount, South China Sea and Their Linkage to a Plume-Modified Mantle Reservoir. Minerals 2025, 15, 1292. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121292

Lu R, Zheng H, Yang L, Xie A, He X, Peng C, Li Z, He H. Basalts from Zhangzhongjing Seamount, South China Sea and Their Linkage to a Plume-Modified Mantle Reservoir. Minerals. 2025; 15(12):1292. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121292

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Rong, Hao Zheng, Lei Yang, Anyuan Xie, Xi He, Cong Peng, Zhengyuan Li, and Huizhong He. 2025. "Basalts from Zhangzhongjing Seamount, South China Sea and Their Linkage to a Plume-Modified Mantle Reservoir" Minerals 15, no. 12: 1292. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121292

APA StyleLu, R., Zheng, H., Yang, L., Xie, A., He, X., Peng, C., Li, Z., & He, H. (2025). Basalts from Zhangzhongjing Seamount, South China Sea and Their Linkage to a Plume-Modified Mantle Reservoir. Minerals, 15(12), 1292. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121292