Abstract

The Cimabanshuo deposit, situated in the western Gangdese Belt, is a recently discovered porphyry Cu deposit formed in a post-collisional setting, approximately 10 km from the giant Zhunuo porphyry Cu deposit. Despite its proximity to Zhunuo, Cimabanshuo remains poorly studied, and the current exploration depth of 600 m leaves the potential for deeper resources uncertain. In this study, 840 samples from four drill holes along the NW-SE section (A-A′) were analyzed using portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF). Based on the geochemical characteristics of primary halos, the deep mineralization potential of Cimabanshuo was evaluated. The results show that Co, Pb, and Ag are near-ore indicator elements; Zn, Cs, Hg, Sb, As, and Ba represent the frontal elements; and Te, Sn, and Bi occur as tail elements. Based on these distributions, a 14-element zoning sequence is defined along the A-A′ profile according to Gregorian’s zoning index, showing Mo-Co-Cu-Pb-Bi-Ag-Sn-Te-Sb-Hg-Cs-Zn-Ba-As from shallow to deep. This sequence shows a distinct reverse zonation pattern, in which tail elements occur in the middle and frontal elements appear at depth, suggesting the existence of a concealed ore body in the lower part of the deposit. Horizontally, the geochemical ratios Ag/Mo and Ag/Cu decrease from northwest to southeast along the profile, implying hydrothermal flow from southeast to northwest. Vertically, the ratios As/Bi, (As × Cs)/(Bi × Te), (As × Ba)/(Bi × Sn), and (As × Ba × Cs)/(Bi × Sn × Te) display a downward-decreasing then upward-increasing trend, further indicating hidden mineralization at depth. This inference is supported by the predominance of propylitic alteration and the deep polarization anomaly revealed by audio-magnetotelluric imaging. pXRF analysis provides a fast, efficient, and environmentally friendly approach, showing strong potential for rapid geochemical evaluation in porphyry Cu exploration.

1. Introduction

As surface and shallow mineral resources become increasingly depleted, exploration has shifted toward concealed and deep-seated deposits to meet the growing demand for mineral supplies. This shift has become a key focus of China’s current deep exploration strategy [1,2]. Previous research has shown that primary halos in typical hydrothermal deposits display clear zonation patterns, which usually include frontal, near-ore, and tail zones [3]. The zonation of primary halos is considered one of the most effective methods for predicting blind or deep orebodies [4,5]. In recent years, this approach has been widely applied in the deep exploration of hydrothermal metal deposits, achieving significant results [6,7,8,9,10,11].

The Cimabanshuo deposit, located in the western part of the Gangdese metallogenic belt (Figure 1), is a newly discovered porphyry Cu deposit [12,13]. At present, research on this deposit remains limited. Previous studies summarized the geological, remote sensing, and geochemical features of the Cimabanshuo area and suggested that it has considerable metallogenic potential and exploration prospects [12], and subsequent work provided a more detailed description of its geological characteristics and proposed that Cimabanshuo formed during the Miocene, similar in age to other Miocene porphyry Cu deposits in the Gangdese Belt [13]. However, the current exploration depth is only about 600 m, and most orebodies are of low grade, making it urgent to assess the potential for deep mineralization.

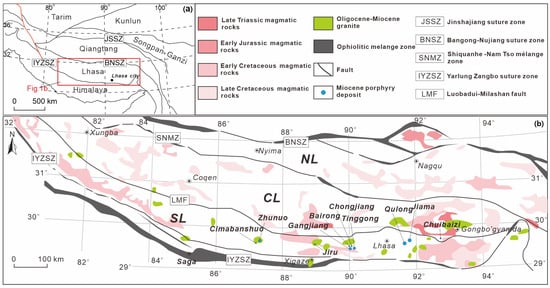

Figure 1.

(a). Tectonic framework map of the Tibetan Plateau (after [14]); (b) Simplified geological map of the Lhasa terrane with the distribution of main Miocene Gangdese porphyry copper deposits (after [15,16,17]).

Conventional mineral exploration methods are often time-consuming and produce delayed analytical results, which severely limit the efficiency of subsequent exploration activities [18]. In recent years, the application of field-based analytical techniques has greatly reduced the time and cost of mineral assessment, providing timely and reliable data for rapid evaluation of metallogenic potential [19,20]. Portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF) offers several advantages, including in situ and non-destructive testing, compact size, simultaneous multi-element analysis, rapid determination of elemental concentrations, and cost-effectiveness [21]. This technique has been widely applied in archaeology, soil analysis, and environmental monitoring [22,23,24,25]. Its use has gradually expanded to mineral exploration, where it plays an increasingly important role in field geology [11,18,26,27].

In this study, pXRF was applied to investigate the geochemical characteristics of primary halos along the NW-SE section (A-A′) of the Cimabanshuo deposit, aiming to establish quantitative indicators for deep exploration and provide a scientific basis for assessing the potential of concealed mineralization in the deposit.

2. Regional Setting

The Tibetan Plateau is the largest continental collisional orogenic belt in the world and has undergone a long and complex tectonic evolution [28,29]. Bounded by the Jinshajiang suture zone (JSSZ), Bangong–Nujiang suture zone (BNSZ), and Indus–Yarlung Zangbo suture zone (IYSSZ), the plateau can be divided from north to south into the Songpan–Ganzi, Qiangtang, Lhasa, and Himalaya terranes [28] (Figure 1a). The BNSZ represents the remnant of the Bangong–Nujiang Tethys Ocean crust, and the IYSSZ records the northward subduction and final closure of the Neo-Tethys Ocean [28,29].

The Lhasa terrane is bounded to the north by the BNSZ and to the south by the IYSSZ, extending ~2500 km east–west, and it can be further subdivided into the northern, central, and southern Lhasa terranes by the Shiquanhe–Nima–Jiali ophiolitic mélange zone (SNMZ) and the Luobadui–Milashan fault (LMF) [14] (Figure 1b). The northern and southern Lhasa terranes consist mainly of juvenile crust and Triassic–Cretaceous sedimentary cover, whereas the central Lhasa terrane is characterized by a Precambrian crystalline basement overlain by extensively metamorphosed Carboniferous–Cretaceous sedimentary sequences [29].

The Gangdese belt, located in the southern part of the Tibetan Plateau, consists of the southern margin of the central Lhasa terrane and the southern Lhasa terrane, extending for about 1500 km. It experienced extensive Late Triassic–Cretaceous magmatism and volcanism induced by the northward subduction of the Neo-Tethyan oceanic slab [14,30]. Since the collision between the Indian and Eurasian continents at ~65–55 Ma [31,32], large-scale magmatic activity has developed in the Gangdese belt, and voluminous Linzizong volcanic rocks and their coeval intrusive rocks were emplaced during the early stage of continent-continent collision [32,33]. During the late collisional stage, adakitic rocks formed in the Oligocene-Miocene (33–12 Ma), and potassic to ultrapotassic volcanic rocks developed in the Miocene (25–8 Ma) [15,34,35,36,37].

A large number of Miocene porphyry Cu-Mo deposits, such as Qulong, Jiama, and Zhunuo, were formed in the Gangdese belt [15,16,38,39], and most of these deposits are distributed in the eastern segment of the belt (east of 88° E) (Figure 1b). The Re-Os ages of molybdenite range from 17 to 13 Ma [16], indicating that the formation of these deposits was closely related to the emplacement of adakitic intrusions.

3. Deposit Geology

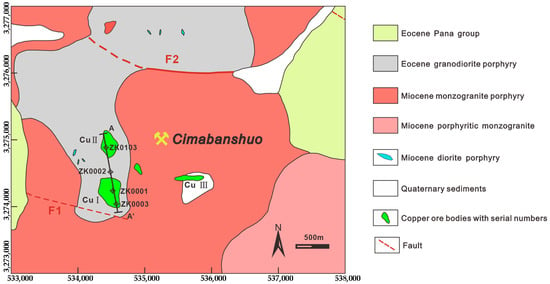

The geological background of the Cimabanshuo deposit has been comprehensively described in previous studies [12,13], and its key features are briefly reviewed here. Preliminary estimates indicate that the deposit hosts more than 0.5 Mt of copper resources and shows favorable geological conditions for mineralization [12]. Exposed strata within the deposit area belong to the Eocene Pana Formation, mainly distributed in the northeastern part of the deposit (Figure 2), and are composed predominantly of tuff and dacitic porphyry. Two major fault systems are developed in the area, including the nearly east–west-trending F1 and the northwest-trending F2 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Geologic map of Cimabanshuo porphyry copper deposit.

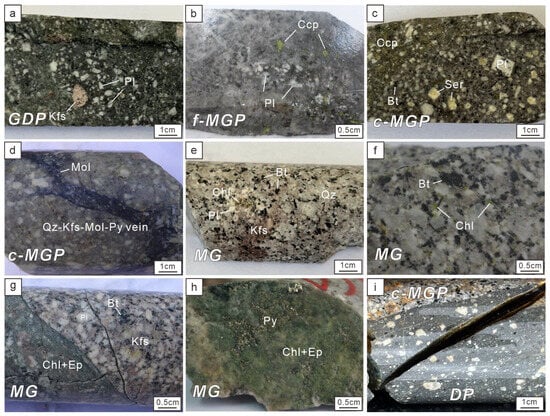

Intrusive rocks are widely developed in Cimabanshuo, including Eocene granodiorite porphyry (50.0 ± 0.8 Ma) (Figure 3a), quartz porphyry, granodiorite, and the Miocene Cimabanshuo intrusive complex. The complex consists of ore-related fine-grained monzogranite porphyry (16.0 ± 0.3 Ma) (Figure 3b), coarse-grained monzogranite porphyry (15.9 ± 0.1 Ma) (Figure 3c,d), hornblende monzogranite porphyry (15.8 ± 0.1 Ma), and late-mineralization diorite porphyry and monzogranite (15.5 ± 0.1 Ma) [13] (Figure 3e–i). The Re-Os age of molybdenite from the deposit is 16.7 ± 0.3 Ma [40], indicating that mineralization occurred during the Miocene.

Figure 3.

Representative photographs of typical lithologies, alterations, and ore minerals in the Cimabanshuo deposit. (a) Eocene granodiorite porphyry; (b) fine-grained monzogranite porphyry with disseminated chalcopyrite; (c) coarse-grained monzogranite porphyry containing dense disseminated chalcopyrite and sericitization within plagioclase phenocrysts; (d) quartz-K-feldspar-molybdenite-pyrite vein crosscutting the coarse-grained monzogranite porphyry; (e) monzogranite showing pervasive K-feldspar alteration, with partial replacement of biotite by chlorite; (f) chloritization in monzogranite; (g) propylitic alteration (epidote-chlorite assemblage) developed in monzogranite; (h) propylitic alteration along fractures in monzogranite; (i) contact between coarse-grained monzogranite porphyry and diorite porphyry. Abbreviations: GDP, granodiorite porphyry; f-MGP, fine-grained monzogranite porphyry; c-MGP, coarse-grained monzogranite porphyry; MG, monzogranite; DP, diorite porphyry; Pl, plagioclase; Kfs, K-feldspar; Bt, biotite; Ser, sericite; Qz, quartz; Chl, chlorite; Ep, epidote; Ccp, chalcopyrite; Py, pyrite.

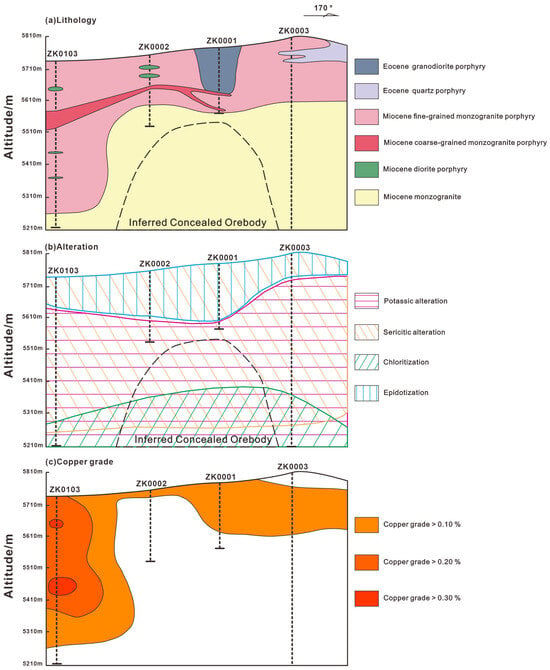

Four types of hydrothermal alteration are recognized in the Cimabanshuo deposit: potassic, propylitic, sericitic, and late-stage alteration dominated by calcitization and anhydritization [13]. Spatially, potassic alteration occurs at the middle to deep levels, and propylitic alteration is superimposed on its outer zone, whereas sericitic alteration overprints both earlier types. Calcitization and anhydritization are weakly developed and lack large-scale distribution. Unlike typical alteration patterns in other porphyry deposits [16], the deep part of Cimabanshuo exhibits extensive propylitic alteration that strongly overprints the early potassic assemblage (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Lithology (a), alteration (b), and copper-grade distribution (c) maps of section A-A′ in the Cimabanshuo deposit.

Potassic alteration is characterized by the presence of K-feldspar, biotite, quartz, and minor magnetite, and mainly occurs within monzogranite, fine-grained monzogranite porphyry, and coarse-grained monzogranite porphyry (Figure 3e–g). Because of the different mineral assemblages of the host rocks, potassic alteration shows varied expressions: in monzogranite, it is marked by hydrothermal K-feldspar and secondary feldspar overgrowths; in fine-grained monzogranite porphyry, disseminated hydrothermal K-feldspar dominates, with minor biotitization; and in coarse-grained monzogranite porphyry, moderate to weak biotitization is common, locally accompanied by feldspar overgrowths. Propylitic alteration occurs in two distinct horizons and can be divided into two types according to the host lithology. The upper type mainly develops in fine-grained and hornblende monzogranite porphyries and is dominated by epidotization with minor chloritization, whereas the deeper type mainly occurs in monzogranite and is characterized by strong chloritization with weak epidotization (Figure 4b). Sericitic alteration is characterized by sericite, chlorite, quartz, and pyrite, and is widely distributed throughout the various intrusive rocks. Calcitization and anhydritization are mainly developed in the middle to deep zones and occur within monzogranite, coarse-grained and fine-grained monzogranite porphyries, quartz porphyry, and dacitic porphyry, mostly forming as vein fillings.

The primary ore mineral in Cimabanshuo is chalcopyrite, with minor molybdenite. Mineralization is mainly hosted in fine-grained monzogranite porphyry, granodiorite porphyry, and coarse-grained monzogranite porphyry (Figure 3b–d), and took place predominantly during the potassic alteration stage. Although the monzogranite shows strong potassic alteration overprinted by sericitic alteration, it is almost barren of mineralization [13] (Figure 4b,c).

4. Sampling and Analytical Methods

Four drill cores (ZK0103, ZK0002, ZK0001, and ZK0003) were systematically collected from the Cimabanshuo deposit along the A-A′ section (Figure 2). The sampling interval was generally 2–5 m, and denser sampling at 1–2 m intervals was conducted in zones with strong mineralization and alteration. A total of 840 primary halo samples were collected from these drill cores, with the original data provided in Supplementary Materials. For sample preparation, half of each drill-core sample was cut for grade analysis, whereas the remaining half was used for pXRF measurements. All samples were cleaned and dried prior to analysis, and pXRF measurements were performed on polished, flattened surfaces.

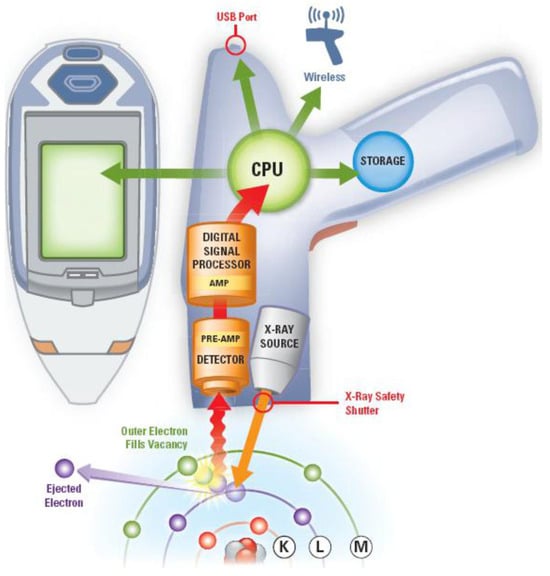

Elemental analyses were performed using a portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (pXRF; Niton XL3t GOLDD+, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Billerica, MA, USA). The instrument operates by irradiating the sample with primary X-rays, which interact with atoms and eject inner-shell electrons. The resulting vacancies are filled by electrons from higher energy levels, releasing excess energy as electromagnetic radiation known as characteristic X-rays (Figure 5). Because each element has a distinct atomic structure, the emitted X-rays have unique energies corresponding to specific elements. The intensity of these characteristic X-rays is proportional to the concentration of the respective element, allowing quantification based on measured intensities [41].

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of the working principle of pXRF.

Each sample was analyzed three times at different positions to minimize the effects of sample heterogeneity, with a measurement duration of 120 s per spot. The average value of the three measurements was taken as the final elemental concentration. Analyses were conducted in the mining and soil mode, and calibration was performed using Canadian Certified Reference Materials (CCRMP) soil standards TILL-1 to TILL-4 and RCRA standard samples. Multiple consecutive measurements of each standard were averaged to establish calibration curves, and correction factors (slope and intercept) were applied in the pXRF settings. The TILL-4 standard and duplicate samples were further measured to assess precision and stability. The analyzed elements include Ag, As, Ba, Bi, Co, Cs, Cu, Hg, Mo, Pb, Sb, Sn, Te, and Zn.

5. Data Processing and Analysis

5.1. Treatment of Data Below the Detection Limit

The pXRF instrument can only detect elements whose concentrations exceed its detection limit, and values below this limit are displayed as <LOD (limit of detection). Such data cannot be treated as zeros, as doing so would result in the loss of potentially useful geological information [42]. In this study, values below the detection limit were replaced with one-half of the respective detection limit for each element (Table 1).

Table 1.

Detection limits of different elements measured by pXRF.

5.2. Correlation Analysis

To minimize the influence of anomalously high values, the raw data were first log-transformed [43]. Correlation analysis of 14 elements was then performed using SPSS Statistics 19.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) to obtain the correlation coefficient matrix (Table 2). Cu and Mo, the major ore-forming elements in the study area, show a positive correlation. Cu exhibits positive correlations with Mo, Co, and Pb, but a negative correlation with Zn; additionally, Mo is positively correlated with Co. These results suggest that Co and Pb are likely the main associated elements and can serve as important geochemical indicators for exploration in peripheral and deeper parts of the deposit.

Table 2.

Correlation coefficient matrix of ore-forming and halo-forming elements.

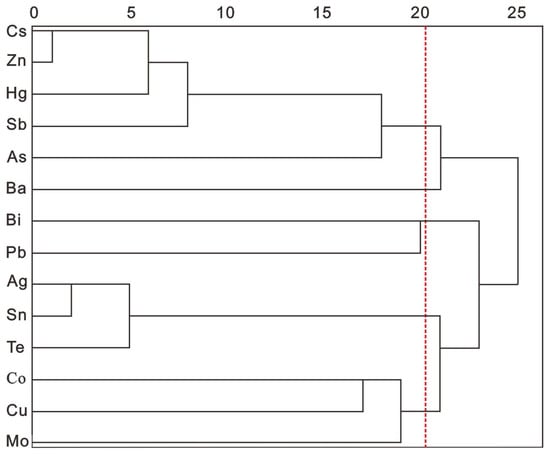

5.3. R-Type Cluster Analysis

R-type cluster analysis groups variables according to the principle of “like attracts like” revealing differences in geochemical behaviors among elements [44]. In this study, the raw data of each variable were standardized and clustered using the between-groups linkage method. The correlation coefficients among variables were calculated to produce a dendrogram (Figure 6). With a linkage distance of 20 as the boundary, the elements can be divided into five groups.

Figure 6.

Cluster analysis diagram of primary halos elements in the Cimabanshuo deposit.

Group 1 consists of Mo, Cu, and Co, indicating that Co can serve as an indirect indicator of mineralization and represents the best geochemical tracer for Cu-Mo mineralization.

Group 2 comprises Te, Sn, and Ag, representing a combination of high- and low-temperature elements, implying the complexity of the mineralization process.

Group 3 includes Pb and Bi, corresponding to a medium-high-temperature element assemblage.

Group 4 contains only Ba.

Group 5 consists of As, Sb, Hg, Zn, and Cs, representing a medium-low-temperature element assemblage.

5.4. Factor Analysis

To further clarify the relationships among ore-forming and halo-forming elements, factor analysis was performed on the 14 elements. Factor analysis, a dimensionality-reduction technique, extracts a few meaningful factors that reveal the internal relationships among variables, each factor typically reflecting a specific geological process [45]. In this study, five principal factors were extracted using principal component analysis (PCA) in SPSS, followed by varimax orthogonal rotation [46], with a cumulative variance contribution of 73.252% (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factor analysis of major elements.

Factor F1 is mainly loaded on Cs, Hg, Sb, and Zn, distributed predominantly in the southeastern part of the primary halo anomaly profile (Figure 7), representing a medium-low-temperature element assemblage.

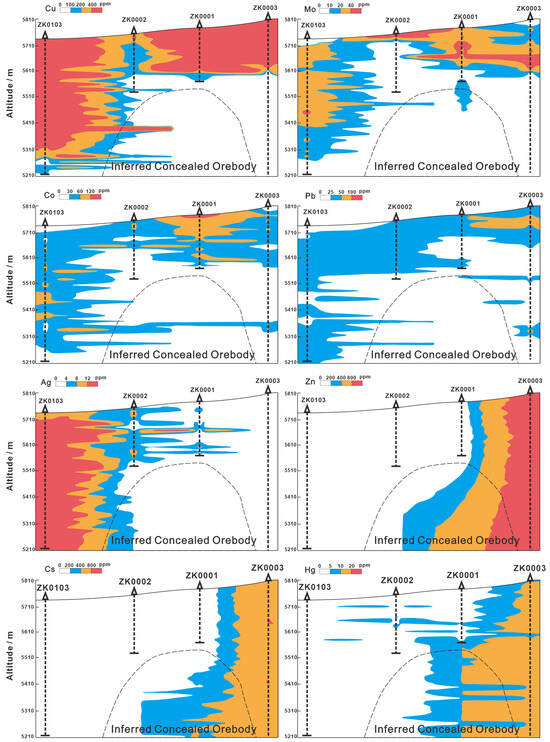

Figure 7.

Elemental primary halo zonation map along the A-A′ section of the Cimabanshuo deposit.

Factor F2 is mainly loaded on Ag, Sn, and Te, concentrated in the northwestern part of the profile and overlapping the Cu orebody, representing a mixed high- and low-temperature assemblage that implies temperature overprinting during mineralization.

Factor F3 is mainly loaded on Cu, Mo, and Bi, indicating that Bi is closely associated with the ore-forming elements.

Factor F4 is mainly loaded on Pb and As, representing a medium-low-temperature assemblage related to Pb-As enrichment during the late hydrothermal stage.

Factor F5 is mainly loaded on Ba and Co.

6. Discussion

6.1. Characteristics of Primary Halos

Primary halo zoning in hydrothermal deposits results from the differing geochemical behaviors of ore-forming and associated elements. Variations in their occurrence forms and migration mechanisms during hydrothermal evolution led to sequential precipitation of elements, forming spatially zoned geochemical patterns [47].

6.1.1. Determination of Anomaly Thresholds

A prerequisite for studying the concentration zoning of primary halos is to establish reasonable anomaly thresholds [8]. In this study, the method proposed by Shao (1997) [4] was adopted. For ore-forming elements, one-tenth of their industrial grade was used as the anomaly threshold. For other elements closely associated with mineralization, the iterative elimination method was applied:

First, the mean (X0) and standard deviation (S0) were calculated for each element;

Then, data beyond X0 ± 3S0 were removed to obtain a new dataset, from which a new mean (X1) and standard deviation (S1) were recalculated;

This process was repeated until all data fell within Xn ± 3Sn, yielding the final mean (X) and standard deviation (S). The value of X + 2S was then taken as the anomaly threshold.

Based on the widely used three-level zoning standard, anomaly thresholds were multiplied by 1, 2, and 4 to define the outer, middle, and inner zones, respectively [4,48]. The elemental concentration profiles were plotted accordingly (Table 4). It should be noted that both the anomaly threshold and the zonal boundaries were flexibly adjusted according to the actual characteristics of each element to best reveal the zoning pattern in the primary halo profiles [8].

Table 4.

Zoning parameters of ore-forming and halo-forming element concentrations.

6.1.2. Profile Characteristics of Primary Halos

Based on data from four drill holes along the A-A′ section and the anomaly zoning values of each element, elemental concentration contour maps were constructed (Figure 7).

Four major conclusions can be drawn from Figure 7:

- (1)

- Ore-forming elements (Cu, Mo):

Cu and Mo exhibit well-developed primary halo structures with distinct enrichment centers. Their anomaly distributions are nearly identical, indicating a genetic relationship between the two elements. The Cu inner-zone anomalies coincide spatially with the Cu orebody (Figure 4c), verifying the reliability of pXRF data, consistent with the conclusion of Sun et al. (2023) [11].

- (2)

- Near-ore elements (Co, Pb, Ag):

Co, Pb, and Ag display extensive anomaly distributions. Ag shows distinct inner, middle, and outer zones, whereas Co and Pb display only middle and outer anomalies. Overall, these elements share similar distribution patterns with Cu-Mo anomalies, suggesting they can serve as near-ore halo indicators.

- (3)

- Frontal halo elements (Zn, Cs, Hg, Sb, As, Ba):

These elements show clear three-tiered zoning, particularly Zn, As, and Ba, which exhibit complete and well-defined inner, middle, and outer zones. Their inner or middle anomalies mainly occur in the southeastern part of the profile, overlapping or extending slightly deeper than the Cu orebody. These features indicate that they represent the frontal halo elements in the hydrothermal system [48].

- (4)

- Distal or tail halo elements (Te, Sn, Bi):

Te, Sn, and Bi show anomalies mainly in the lower parts of the orebody, with only middle and outer zones. Te and Sn share similar patterns, with strong anomalies concentrated in the northwestern side of the profile and extending beyond the current drilling depth. Bi anomalies are weaker and more restricted, occurring mainly beneath the Cu orebody. These elements are interpreted as tail halo indicators of the mineralization system.

6.1.3. Axial Zoning Sequence of the Primary Halo

The axial zoning of a primary halo reflects the migration direction of ore-forming hydrothermal fluids, and the study of its sequence is of great significance for evaluating the degree of erosion of ore bodies, predicting concealed mineralization, and estimating the scale of deep orebodies [5].

Drill core samples along the A-A′ section cover an elevation range of 5214–5811 m. Following the principle that each middle section should contain no fewer than three data points [4], the A-A′ section was divided from surface to depth into four middle sections: above 5650 m (Section I), 5500–5650 m (Section II), 5350–5500 m (Section III), and below 5350 m (Section IV). Based on the modified zoning index method [49,50], zoning indices for all elements were calculated (Table 5). The section with the maximum zoning index of each element was taken as its representative position within the axial sequence. The preliminary elemental zoning sequence is:

Table 5.

Zoning indices of the primary halo.

Section I—Co, Cu, Mo, Pb;

Section II—Ag, Bi, Sn;

Section III—Cs, Hg, Sb, Te, Zn;

Section IV—As, Ba.

When multiple elements shared the same maximum zoning section, the gradient index method was applied [51,52]. The resulting axial zoning sequence of ore-forming and halo elements along the A-A′ profile at the Cimabanshuo deposit, from top to bottom, is:

Mo-Co-Cu-Pb-Bi-Ag-Sn-Te-Sb-Hg-Cs-Zn-Ba-As.

Two major conclusions can be drawn from this sequence:

- (1)

- The ore-forming elements Cu and Mo occur at the uppermost part of the sequence, close to the surface, suggesting that the orebody has experienced a certain degree of erosion. This is consistent with the observation that the Cu orebody was not intercepted in the shallow drill holes (Figure 4c). Sun et al. (2021) [53] reported an exhumation rate of ~150 m/m.y. and an erosion depth of ~1.4 km for the nearby Zhunuo deposit. Given that Cimabanshuo lies ~10 km southwest of Zhunuo, both deposits likely experienced similar preservation conditions, further indicating partial erosion of the Cimabanshuo orebody.

- (2)

- Compared with the standard zoning sequence [4], the A-A′ profile at Cimabanshuo exhibits a distinct reverse zoning pattern, in which tail-halo elements (Bi, Sn, Te) appear in the middle section, whereas frontal-halo elements (Sb, Hg, Cs, Zn, Ba, As) occur in the lower section. This observation agrees with the concept of structural superimposition halos proposed by Li et al. (2006) [5], in which the occurrence of tail-halo elements upward or frontal-halo elements downward indicates a multi-stage superimposed mineralization system. The presence of downward frontal-halo anomalies suggests a potential concealed orebody at depth.

This inference is further supported by the widespread propylitic alteration developed in the lower part of the section (Figure 4b). In porphyry systems, propylitic alteration generally forms at the outer margin of mineralization [54], indicating that deeper zones beneath the current drilling depth may host potassic alteration and an additional mineralization stage.

6.2. Geochemical Characteristics of Primary Halos

6.2.1. Vertical Characteristics

During ore formation, multiple episodes and stages of mineralization often lead to the superposition of ore bodies (and halos), which disrupts the simple monotonic variation in primary halo element contents in the vertical or lateral direction and causes distinct inflection features [55]. The ratio of the cumulative product of front-halo elements to that of tail-halo elements reflects the degree of front-halo development relative to the tail-halo and thus provides a quantitative evaluation of the deep ore potential [56,57].

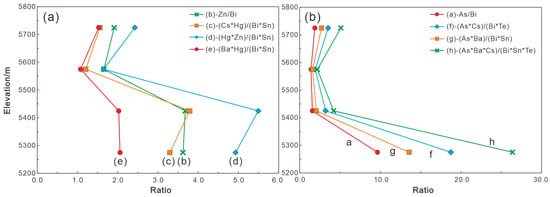

Before calculating this ratio, differences in elemental magnitudes were normalized by introducing the contrast coefficient, which characterizes the degree of enrichment of an element [11,43]. The contrast coefficient is defined as the ratio of the average content of an element in a given sublevel to its background value, which is taken as half of the anomaly lower limit [11] (Table 4). Based on the ratio between front- and tail-halo element assemblages, eight geochemical evaluation indices were constructed [8,11] (Table 6; Figure 8): (a) As/Bi; (b) Zn/Bi; (c) (Cs × Hg)/(Bi × Sn); (d) (Hg × Zn)/(Bi × Sn); (e) (Ba × Hg)/(Bi × Sn); (f) (As × Cs)/(Bi × Te); (g) (As × Ba)/(Bi × Sn); (h) (As × Ba × Cs)/(Bi × Sn × Te). For convenience, these eight indices are subsequently referred to by their letter labels (a–h) in the figures and text, with their full formulae listed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Geochemical evaluation parameter indices.

Figure 8.

Axial variation in geochemical parameter evaluation indices. (a) Variation of indices (b), (c), (d), and (e) with altitude; (b) variation of indices (a), (f), (g), and (h) with altitude.

According to their variation patterns, these indices can be grouped into two categories. Indices (a), (c), (d), and (e) decrease from depth to shallow levels, then increase and finally decrease again, showing an oscillatory trend that indicates superimposed mineralization events [55]. Indices (a), (f), (g), and (h) decrease first and then increase from shallow to deep levels. Chen et al. (2008) [58] suggested that when these indices systematically decrease with depth and suddenly rise at a deeper level, it indicates the reappearance of mineralization—namely, the presence of a concealed ore body at depth. This abrupt increase reflects the overlap of the front halo of a deep ore body with the tail halo of an upper ore body [58,59,60].

Therefore, these features suggest a certain degree of ore potential in the deeper part of the A-A′ section, consistent with the inference derived from the axial zoning sequence of the primary halos.

6.2.2. Horizontal Characteristics

Beus and Grigorian (1977) [49] found in their study of the Saronrechku porphyry copper deposit that Ag anomalies broaden above and in front of the ore body, whereas Mo anomalies broaden below and behind it. They therefore proposed that the spatial patterns of Ag and Mo anomalies, as well as the Ag/Cu ratio, can be used to distinguish the upper and lower parts of an inclined ore body and to infer the direction of hydrothermal fluid flow. Shao (1997) [4] further suggested that both Ag/Mo and Ag/Cu ratios can effectively indicate the direction of hydrothermal movement.

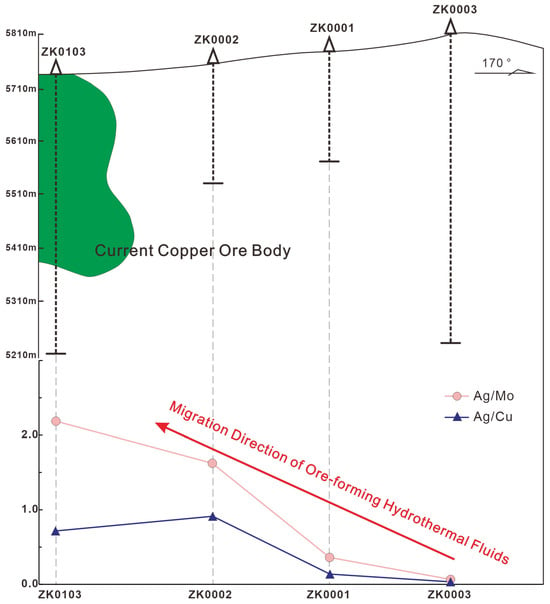

In this study, the Ag/Mo and Ag/Cu indices were established based on contrast coefficients, and their lateral variation trends were plotted (Figure 9). The two indices display broadly consistent variation patterns along the A-A′ section, showing an overall decrease from the southeast toward the northwest, indicating that hydrothermal fluids migrated from the southeast to the northwest (Figure 9). The currently revealed main ore body occurs in the shallow northwestern part of the section (Figure 9), and the fluid flow direction from deep southeast to shallow northwest suggests the possible presence of a concealed ore body in the southeastern deep zone. Audio-magnetotelluric data from Cimabanshuo indicate a broad high-polarizability anomaly at depths of 1–2 km in the southeastern direction, which may be related to Cu mineralization [61], further supporting this inference.

Figure 9.

Distribution of the main orebody, variations in Ag/Cu and Ag/Mo ratios, and inferred hydrothermal migration direction along the A-A′ section of the Cimabanshuo deposit.

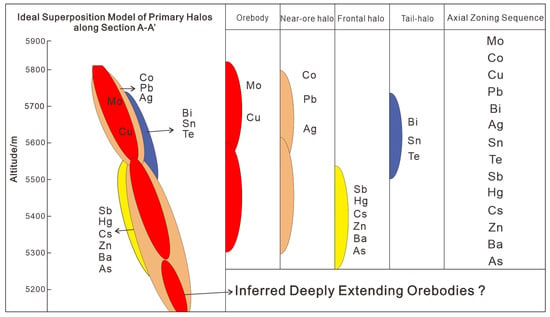

6.2.3. Ideal Superposition Model of Primary Halos

Based on the spatial distribution of primary halo anomalies and the variation patterns of geochemical parameters along the A-A′ section, a conceptual model of idealized primary halo superposition was constructed (Figure 10), as follows: (1) The ore-forming elements Cu and Mo occur in the upper part of the primary halo zoning sequence, and their corresponding anomalies are mainly concentrated near the surface, indicating that the Cimabanshuo deposit has undergone a certain degree of erosion. (2) The axial zoning sequence of the primary halo exhibits a reverse zoning pattern, where near-ore elements appear beneath the tail-halo elements. Combined with the vertical variations in geochemical parameters, this feature suggests that the ore body extends downward. (3) The lateral variation in geochemical parameters indicates that hydrothermal fluids migrated from the southeast toward the northwest.

Figure 10.

Ideal superposition model of the primary halo along the A-A′ section of the Cimabanshuo deposit.

Therefore, it is proposed that the southeastern deep part of the Cimabanshuo deposit possesses significant mineralization potential.

7. Conclusions

- (1)

- Based on cluster analysis, factor analysis, and primary halo element anomalies in the Cimabanshuo deposit, Co, Pb, and Ag were identified as near-ore halo elements; Zn, Cs, Hg, Sb, As, and Ba as frontal halo elements; and Te, Sn, and Bi as tail-halo elements. From shallow to deep, the axial zoning sequence of the primary halo is Mo-Co-Cu-Pb-Bi-Ag-Sn-Te-Sb-Hg-Cs-Zn-Ba-As, exhibiting a reverse zoning pattern that suggests the possible presence of a concealed ore body at depth in the Cimabanshuo deposit.

- (2)

- The geochemical evaluation indices Ag/Mo and Ag/Cu show a decreasing trend from northwest to southeast along the A-A′ section of the Cimabanshuo deposit, indicating hydrothermal fluid flow from southeast to northwest. Major vertical indices—As/Bi, (As × Cs)/(Bi × Te), (As × Ba)/(Bi × Sn), and (As × Ba × Cs)/(Bi × Sn × Te)—first decrease and then increase from shallow to deep levels, implying the presence of a concealed ore body at depth within the deposit. Integrating both horizontal and vertical variations in geochemical indices, the concealed ore body is likely located in the deep southeastern part of the Cimabanshuo deposit.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/min15121286/s1, Original elemental data of drill core samples from the Cimabanshuo porphyry copper deposit measured by pXRF.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.L. and S.W.; methodology, Z.L.; software, Z.L. and P.L.; validation, N.W., M.L. and H.L.; formal analysis, Z.L. and H.L.; investigation, Z.L.; resources, S.W.; data curation, Z.L. and S.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.L. and S.W.; writing—review and editing, Z.L., M.L. and H.L.; visualization, Z.L.; supervision, S.W.; project administration, S.W.; funding acquisition, S.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the National Science and Technology Major Project of Deep Earth (Project No. 2024ZD1003203).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere appreciation to the Editor-in-Chief and Editorial team for their efficient handling of the manuscript, as well as to our team members for their dedication to both field sampling and indoor work.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Zheming Li and Naiying Wei were employed by the Sichuan Jubaopen Engineering Investigation and Design Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Zhao, P. Quantitative mineral prediction and deep mineral exploration. Earth Sci. Front. 2007, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Y.; Qu, H.; Zhao, G.; Chen, Y.; Wang, S.; Cui, Y.; Yan, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Guo, Q.; Yu, H. Study on the primary halo-zonal sequence and prediction of mineral exploration in shallow overburden area. Miner. Explor. 2018, 9, 311–319. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Yu, B.; Li, D.; Ma, J.; Sun, F.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, S. Structural superimposed halo models for predicting deep blind deposits in different types of gold deposits. Miner. Resour. Geol. 2015, 29, 648–653+658. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Y. Rock Survey (Primary Halo Method) of Hydrothermal Deposits Prospecting; Geological Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Zhang, G.Y.; Yu, B. Structural superimposed halo model and prospecting effect for predicting deep blind deposits in gold mining. Geol. China 2006, 21, 632. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Carranza, E.J.M.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, D.; Sun, X.; Duan, C. Characterization of primary geochemical haloes for gold exploration at the Huanxiangwa gold deposit, China. J. Geochem. Explor. 2013, 124, 40–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yu, B.; Li, D.; Zhang, G.; Ma, J.; Sun, F.; Li, Y.; Wei, J.; Zhao, J.; Wang, J.; et al. Innovation and new breakthroughs in exploring blind mines by structural superimposed halos. Gold Sci. Technol. 2014, 22, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.; Cheng, Z.; Pang, Z.; Xue, J.; Tao, W.; Tan, J. Primary halo characteristics and prediction of deep ore body in the Laoliwan Ag-Pb-Zn deposit, Henan Province. Miner. Explor. 2020, 11, 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- An, W.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Wei, J.; Wang, J. The superposition characteristics of primary halo in the Daping gold deposit, Yunnan Province, China and its significance for exploration. J. Geochem. Explor. 2021, 228, 106809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zeng, Q.; Wei, Z.; Fan, H.; Yang, K.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Liang, G.; Xia, F. Prospecting potential of the Yanjingou gold deposit in the east Kunlun orogen, NW China: Evidence from primary halo geochemistry and in situ pyrite thermoelectricity. Minerals 2021, 11, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, W.; Feng, X.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Hou, H.; Ge, L.; Lv, H. Geochemical Characteristics of Primary Halos and Prospecting Significance of the Qulong Porphyry Copper–Molybdenum Deposit in Tibet. Minerals 2023, 13, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, B.; Fu, H.; Lv, J.; Zheng, C. Copper metallogenic condition of Cimabanshuo area around Zhunuo copper mine in Tibet. Acta Geol. Gansu 2017, 26, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Wu, S.; Li, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Yi, J.; Jiang, G.; Liu, X.; Hua, K.; Ci, Q.; Zhao, Y. Alteration-mineralization style and prospecting potential of Cimabanshuo porphyry copper deposit in Tibet. Earth Sci. 2022, 47, 2219–2244. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, D.; Zhao, Z.; Niu, Y.; Mo, X.; Chung, S.; Hou, Z.; Wang, L.; Wu, F. The Lhasa Terrane: Record of a microcontinent and its histories of drift and growth. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2011, 301, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Gao, Y.; Qu, X.; Rui, Z.; Mo, X. Origin of adakitic intrusives generated during mid-Miocene east-west extension in southern Tibet. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2004, 220, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Goldfarb, R.; Chang, Z. Generation of Postcollisional Porphyry Copper Deposits in Southern Tibet Triggered by Subduction of the Indian Continental Plate; Society of Economic Geologists: Littleton, CO, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Sun, X.; Gao, S.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, G.; Wu, S.; You, Z.; Li, J. Multiple mineralization events at the Jiru porphyry copper deposit, southern Tibet: Implications for Eocene and Miocene magma sources and resource potential. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2014, 79, 842–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Xu, R.; Bai, J.; Chen, X.; Yan, T. Application of pXRF in-situ analysis in the exploration of Yuka rutile deposit, North Qaidam. Geol. Bull. China 2023, 42, 966–977. [Google Scholar]

- Bendicho, C.; Lavilla, I.; Pena-Pereira, F.; Romero, V. Green chemistry in analytical atomic spectrometry: A review. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2012, 27, 1831–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Tang, L.; Lao, C.; Zeng, Y. Analysis techniques and applications of field geological experiments. Anal. Instrum. 2018, 1, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield, S.; Bernard, M.; Burgess, C.; Edwards, D.; Hill, S.; Jarvis, K.; Lord, G.; Sargent, M.; Potts, P.; Price, J. Evaluation of analytical instrumentation. Part XXIII. Instrumentation portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometry. Accredit. Qual. Assur. J. Qual. Comp. Reliab. Chem. Meas. 2008, 13, 453–464. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, N.; Speakman, R.J.; Popelka-Filcoff, R.S.; Glascock, M.D.; Robertson, J.D.; Shackley, M.S.; Aldenderfer, M.S. Comparison of XRF and PXRF for analysis of archaeological obsidian from southern Peru. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2007, 34, 2012–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Cheng, Q.; Lu, J.; Xiao, W.; Sang, H.; Yuan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Qiu, J. Application of portable XRF technology to identification of mineralization and alteration along drill in the Nihe iron deposit, Anhui, East China. Earth Sci. 2011, 36, 336–340. [Google Scholar]

- Stockmann, U.; Cattle, S.; Minasny, B.; McBratney, A.B. Utilizing portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometry for in-field investigation of pedogenesis. Catena 2016, 139, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, B.S.; Barker, S.L. Determination of carbonate vein chemistry using portable X-ray fluorescence and its application to mineral exploration. Geochem. Explor. Environ. Anal. 2018, 18, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaram, V. Field-portable analytical instruments in mineral exploration: Past, present and future. J. Appl. Geochem. 2017, 19, 382–399. [Google Scholar]

- Lemiere, B. A review of pXRF (field portable X-ray fluorescence) applications for applied geochemistry. J. Geochem. Explor. 2018, 188, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, A.; Harrison, T.M. Geologic evolution of the Himalayan-Tibetan orogen. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2000, 28, 211–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Zhao, Z.; Niu, Y.; Dilek, Y.; Hou, Z.; Mo, X. The origin and pre-Cenozoic evolution of the Tibetan Plateau. Gondwana Res. 2013, 23, 1429–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Chung, S.; Lo, C.; Ji, J.; Lee, T.; Qian, Q.; Zhang, Q. Eocene Neotethyan slab breakoff in southern Tibet inferred from the Linzizong volcanic record. Tectonophysics 2009, 477, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Kapp, P.; Wan, X. Paleocene–Eocene record of ophiolite obduction and initial India—Asia collision, south central Tibet. Tectonics 2005, 24, TC3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Chung, S.; Cawood, P.A.; Niu, Y.; Liu, S.; Wu, F.; Mo, X. Magmatic record of India-Asia collision. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, X.; Hou, Z.; Niu, Y.; Dong, G.; Qu, X.; Zhao, Z.; Yang, Z. Mantle contributions to crustal thickening during continental collision: Evidence from Cenozoic igneous rocks in southern Tibet. Lithos 2007, 96, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.; Liu, D.; Ji, J.; Chu, M.; Lee, H.; Wen, D.; Lo, C.; Lee, T.; Qian, Q.; Zhang, Q. Adakites from continental collision zones: Melting of thickened lower crust beneath southern Tibet. Geology 2003, 31, 1021–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Mo, X.; Dilek, Y.; Niu, Y.; DePaolo, D.J.; Robinson, P.; Zhu, D.; Sun, C.; Dong, G.; Zhou, S. Geochemical and Sr-Nd-Pb-O isotopic compositions of the post-collisional ultrapotassic magmatism in SW Tibet: Petrogenesis and implications for India intra-continental subduction beneath southern Tibet. Lithos 2009, 113, 190–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Hou, Z.; Li, W.; Liang, W.; Huang, K.; Li, Q.; Sun, Q.; Fu, Q.; Zhang, S. Petrogenesis and geological implications of the Oligocene Chongmuda-Mingze adakite-like intrusions and their mafic enclaves, southern Tibet. J. Geol. 2012, 120, 647–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Lu, Y.; McCuaig, T.C.; Zheng, Y.; Chang, H.; Guo, F.; Xu, L. Miocene ultrapotassic, high-Mg dioritic, and adakite-like rocks from Zhunuo in Southern Tibet: Implications for mantle metasomatism and porphyry copper mineralization in collisional orogens. J. Petrol. 2018, 59, 341–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Xue, Y.; Cheng, L.; Fan, Z.; Gao, S. Finding, characteristics and significances of Qulong superlarge porphyry copper (molybdenum) deposit, Tibet. Earth Sci. 2004, 29, 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, B.; Tang, J.; Tang, P.; Beaudoin, G.; Laflamme, C.; Li, F.; Zheng, W.; Song, Y.; Qi, J.; Sun, M. Multipulsed magmatism and duration of the hydrothermal system of the giant Jiama porphyry Cu system, Tibet, China. Econ. Geol. 2024, 119, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wu, S.; Ci, Q.; Chen, X.; Gao, S.; Liu, X.; Jiang, X.; Zheng, S.; Li, M.; Jiang, X. Cu-Mo-Au metallogenesis and minerogenetic series during superimposed orogenesis process in Gangdese. Earth Sci. 2021, 46, 1909–1940. [Google Scholar]

- Gazley, M.F.; Tutt, C.M.; Fisher, L.A.; Latham, A.R.; Duclaux, G.; Taylor, M.D.; de Beer, S.J. Objective geological logging using portable XRF geochemical multi-element data at Plutonic Gold Mine, Marymia Inlier, Western Australia. J. Geochem. Explor. 2014, 143, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Zheng, Y.; Niu, X.; Qin, Y.; Wang, W.; Qiao, Y.; Di, B.; Hou, M.; Zhao, S.; Cong, P. Practicality of hand-held XRF analyzer in rapid exploration of porphyry copper deposit. Rock Miner. Anal. 2021, 40, 206–216. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, D.; Dai, L.; Wan, G.; Hou, B. Characteristics of structurally superimposed geochemical haloes at the polymetallic Xiasai silver-lead-zinc ore deposit in Sichuan Province, SW China. J. Geochem. Explor. 2016, 169, 100–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Xiao, K.; Gao, Y. Geochemical characteristics of primary halos and evaluation of deep mineral resources in the Caixiashan lead-zinc deposit. J. Jilin Univ. (Earth Sci. Ed.) 2013, 43, 1179–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Hu, W.; Li, Z. Statistical Prediction of Mineral Deposits, 2nd ed.; China Geological Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Yang, G.; Tan, X. Application of SPSS based regression analysis in trace element analysis of Donggualin gold deposit in Yunnan. China Min. Mag. 2016, 25, 148–153. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, G.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Y.; Huang, F.; Zhao, Z. Characteristics of primary halos for quartz vein-type tungsten deposits and its implication in locating ore bodies at depth—A case study of the Taoxikeng deposit, Southern Jiangxi Province. Geotecton. Metallog. 2012, 36, 406–412. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Ma, S.; Hu, S. Exploration indicators for primary halos in metal deposits. Geophys. Geochem. Explor. 2010, 34, 765–771. [Google Scholar]

- Beus, A.A.; Grigorian, S.V. Geochemical Exploration Methods for Mineral Deposits; Applied Publishing Ltd.: Portsmouth, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Sang, X.; Guo, X.; Xie, H.; Zhao, L.; Sun, Y. The improved gregorian’s zoning index calculating method. J. Jilin Univ. (Earth Sci. Ed.) 2007, 37, 884–888. [Google Scholar]

- Xianrong, L.; Meilan, W.; Fei, O.; Jiaguang, T. Exploration Geochemistry; Metallurgical Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Kong, F.; Shen, L.; Huang, X.; Xu, C.; Zhang, Y. A study on the characteristics of primary halos and deep exploration prediction of the Fanjiazhuang gold deposit in Shandong province. Miner. Explor. 2019, 10, 108–117. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Leng, C.; Hollings, P.; Song, Q.; Li, R.; Wan, X. New 40Ar/39Ar and (U-Th)/He dating for the Zhunuo porphyry Cu deposit, Gangdese belt, southern Tibet: Implications for pulsed magmatic-hydrothermal processes and ore exhumation and preservation. Miner. Depos. 2021, 56, 917–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillitoe, R.H. Porphyry copper systems. Econ. Geol. 2010, 105, 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Zhuang, G.; Zhang, D.; Gao, R. The axial zoning characteristics of primary halos and evaluation of deep mineralization prospects in the Hongzhuang Yuanling gold deposit in Luanchuan County, Henan Province. Geol. Explor. 2015, 51, 1126–1137. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Yao, C.; Wang, X.; Hua, S.; Wang, J. Primary halo indicators for deep ore body prediction of the Nanhegou copper deposit in Hujiayu, Shanxi. Geol. Sci. Technol. Inf. 2010, 29, 106–110. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Zhang, J.; Li, M.; Wang, B.; Dong, S.; Niu, H.; Sun, Y. The characteristics of primary halos and prospecting prospects in the Shimole area of Inner Mongolia. Geol. Explor. 2016, 52, 128–138. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, J.; Liang, Z. Geochemical characteristics and zonation of primary halos of Pulang porphyry copper deposit, Northwestern Yunnan Province, Southwestern China. J. China Univ. Geosci. 2008, 19, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Sun, L.; Cao, X.; Wang, C.; Tan, J.; Liu, F.; Yang, K. Exploration geochemical indicators for primary halo axis (vertical) zoning characteristics and deep ore body prediction of the Shangzhuang gold deposit in northwest Jiaozhou. Miner. Depos. 2008, 27, 64–70. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Zhang, W.; Liu, B.; Wang, J.; Guo, R. The study on axial zonality sequence of primary halo and some criteria for the application of this sequence for major types of gold deposit in China. Geol. Prospect. 1999, 35, 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, P.; Yin, Y.; Jin, S.; Wei, W.; Xu, L.; Dong, H.; Huang, J. Three-dimensional audio-magnetotelluric imaging including surface topography of the cimabanshuo porphyry copper deposit, Tibet. Minerals 2021, 11, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).