Impact of Operational Parameters on the CO2 Absorption Rate and Uptake in MgO Aqueous Carbonation—A Comparison with Ca(OH)2

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Periclase (MgO) initial concentration.

- CO2 flow rate.

- Temperature.

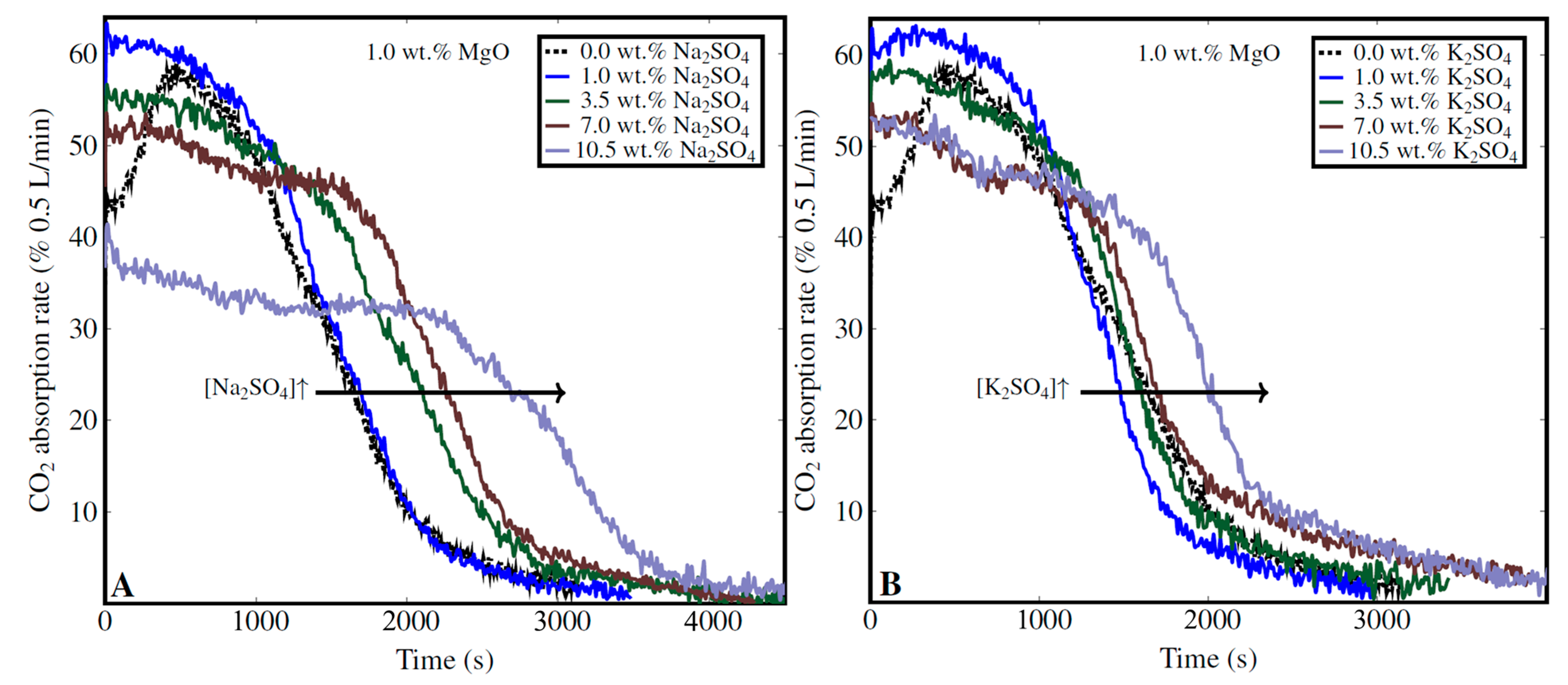

- NaCl, Na2SO4 and K2SO4 concentrations (salinity).

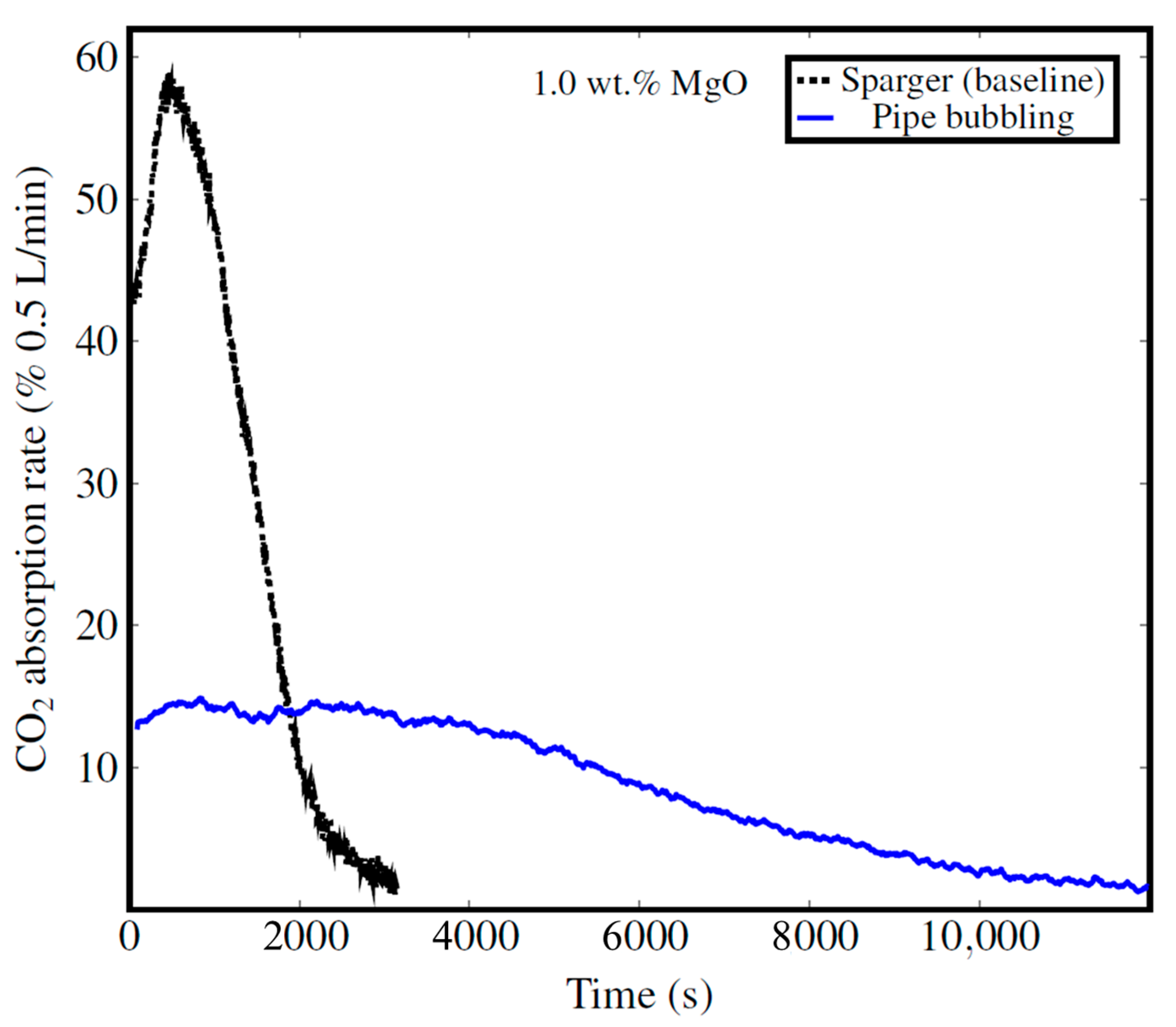

- Static gas−liquid mixing system, with a comparison of the pipe and the sparger.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

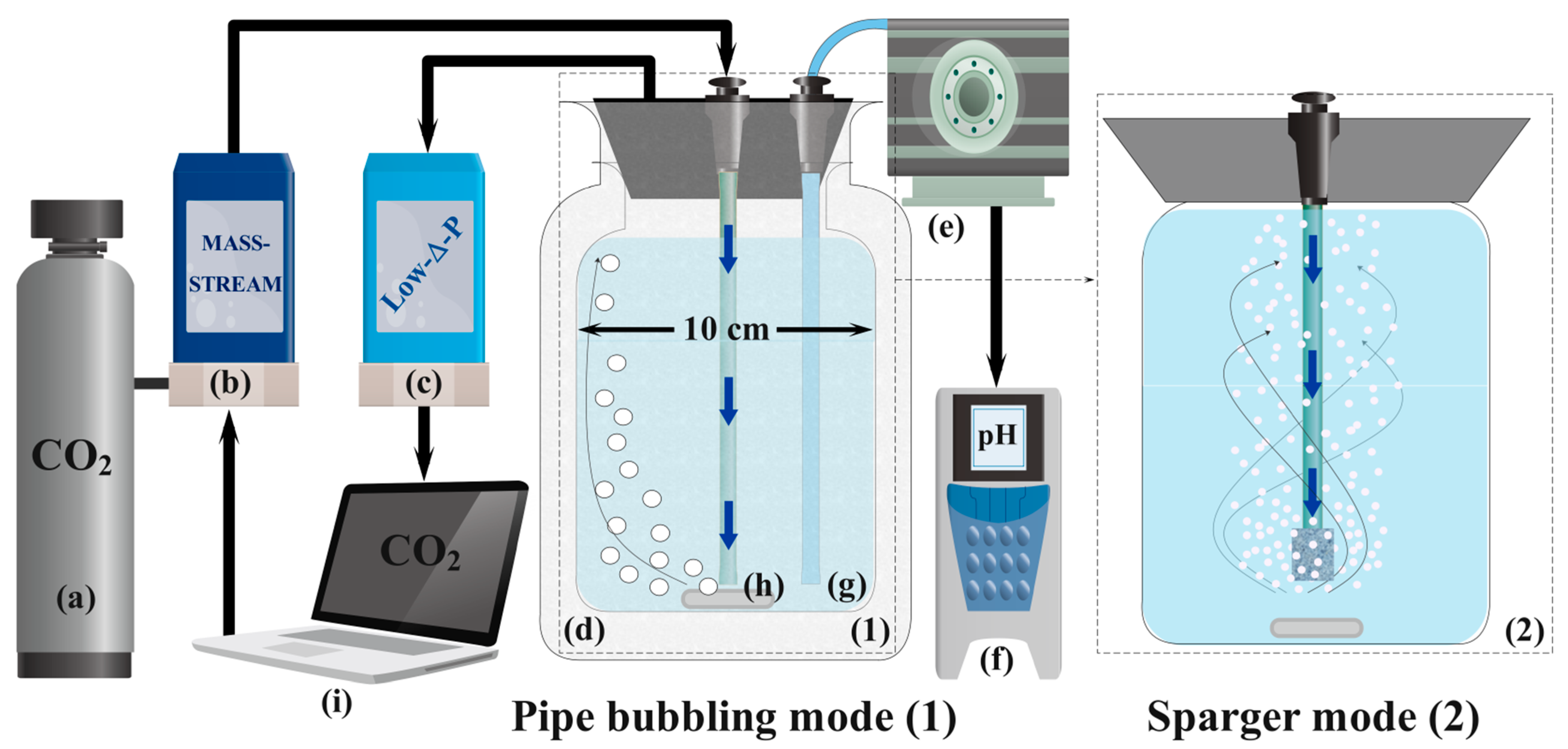

2.2. Laboratory Equipment

2.3. Experimental Procedures for MgO Carbonation

2.4. Phreeqc Geochemical Models

2.5. Data Treatment

3. Results and Discussion

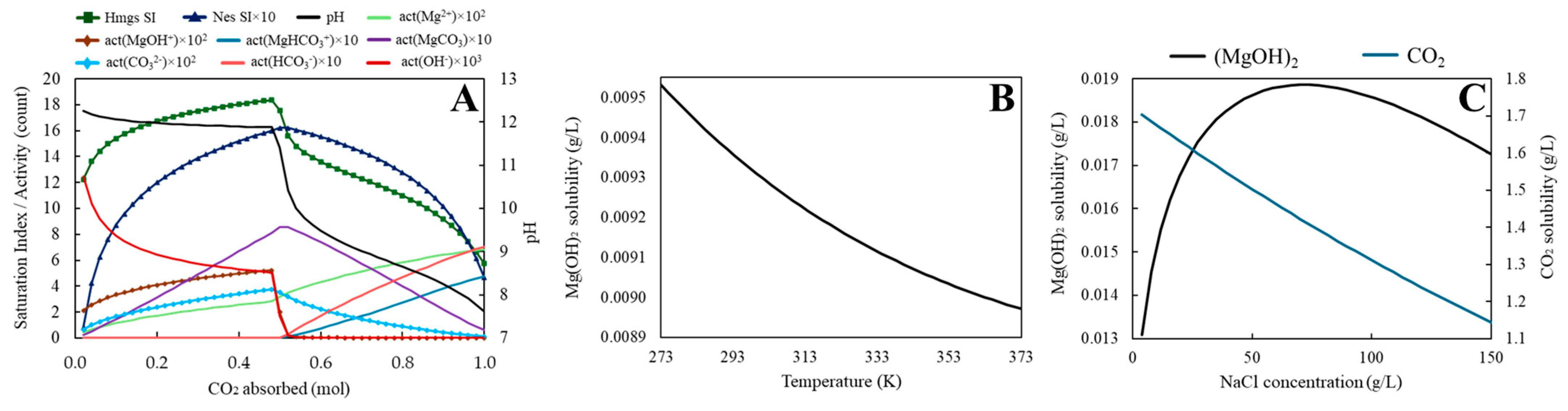

3.1. Geochemical Models

3.1.1. Mg(OH)2 Aqueous Carbonation Equilibrium

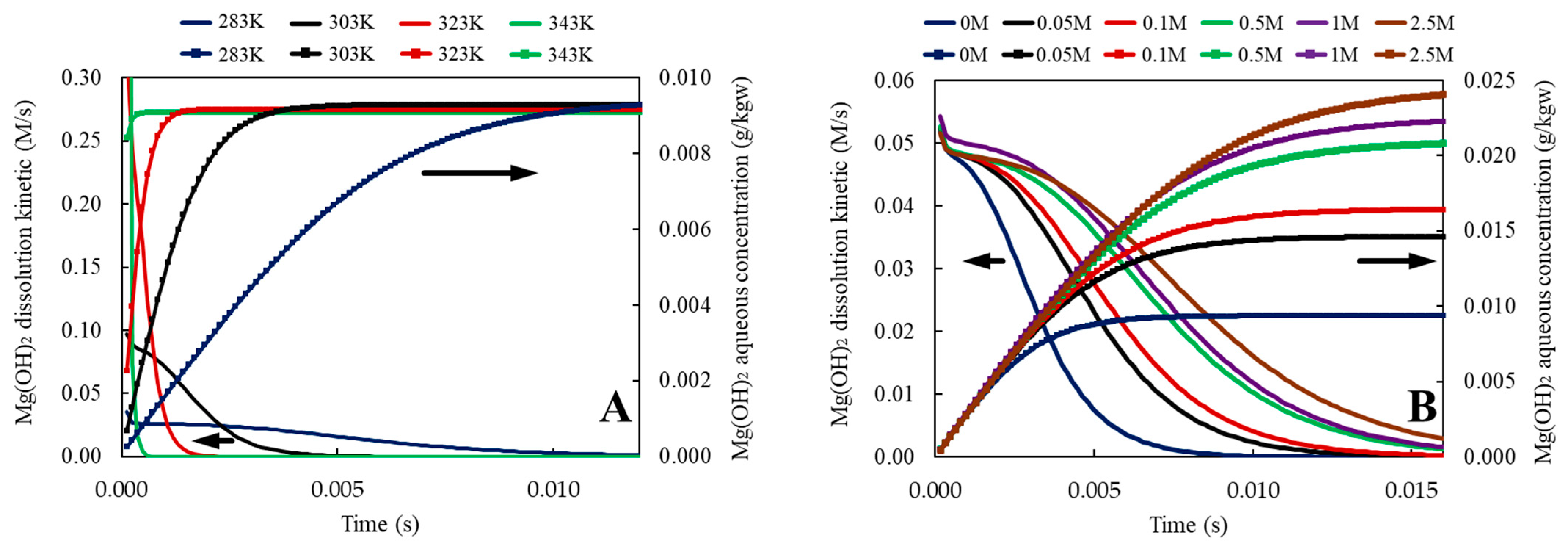

3.1.2. Mg(OH)2 Dissolution Kinetic

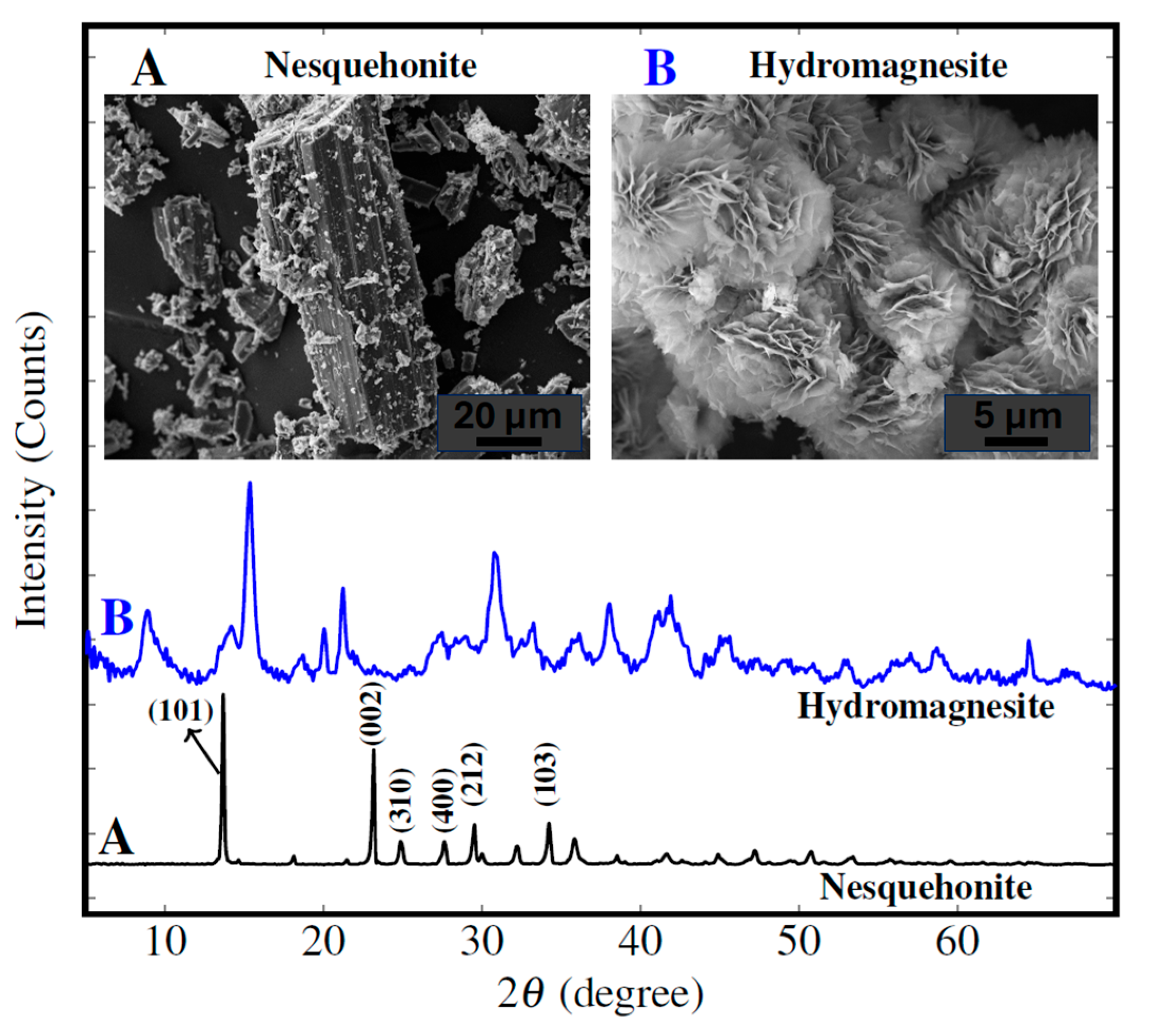

3.2. Aqueous Carbonation Phenomena: Insights from Literature, SEM and XRPD

| Step/Phase Formation | Chemical Reaction | Log K° (298 K)/∆fG° (kJ/mol)/∆fH° | Comments | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MgO hydration | Log K° = −11.16; ∆fG° = −832.2; ∆fH° = −924.66 | Rapid at ambient conditions; forms poorly soluble Mg(OH)2 | [7,53,63] | |

| Mg(OH)2 dissolution | Log K° = 17.01 | Controls Mg2+ availability in solution and pH | [64] | |

| CO2 dissolution | pKa1 = 6.35; pKa2 = 10.33 | CO2 forms carbonic acid; equilibrium shifts based on pH | - | |

| Nes formation | Log K° = −5.27; ∆fG° = −1724.4; ∆fH° = 1981.7 | Forms at T < 35 °C, pH 7–9; metastable | [7,12,65] | |

| Hmgs formation | Log K° = − 37.08; ∆fG° = –5866.6; ∆fH° = −6514.9 | Stable at pH > 9.5, common in long-term carbonation | [7,66,67] | |

| Dyp formation | Log K° = −34.94; ∆fG° = −6081.7; ∆fH° = −6792.8 | More hydrated than Hmgs; intermediate stability | [7,12] | |

| Lfd formation | Log K° = −5.24; ∆fG° = −2197.8; ∆fH° = − 2574.3 | Forms at T < 10 °C; unstable at room temperature | [7] | |

| Mgs formation | Log K° = −8.29; ∆fG° = −1029.3; ∆fH° = −1112.9 | Requires elevated temperature and/or pressure to crystallize | [7,68] |

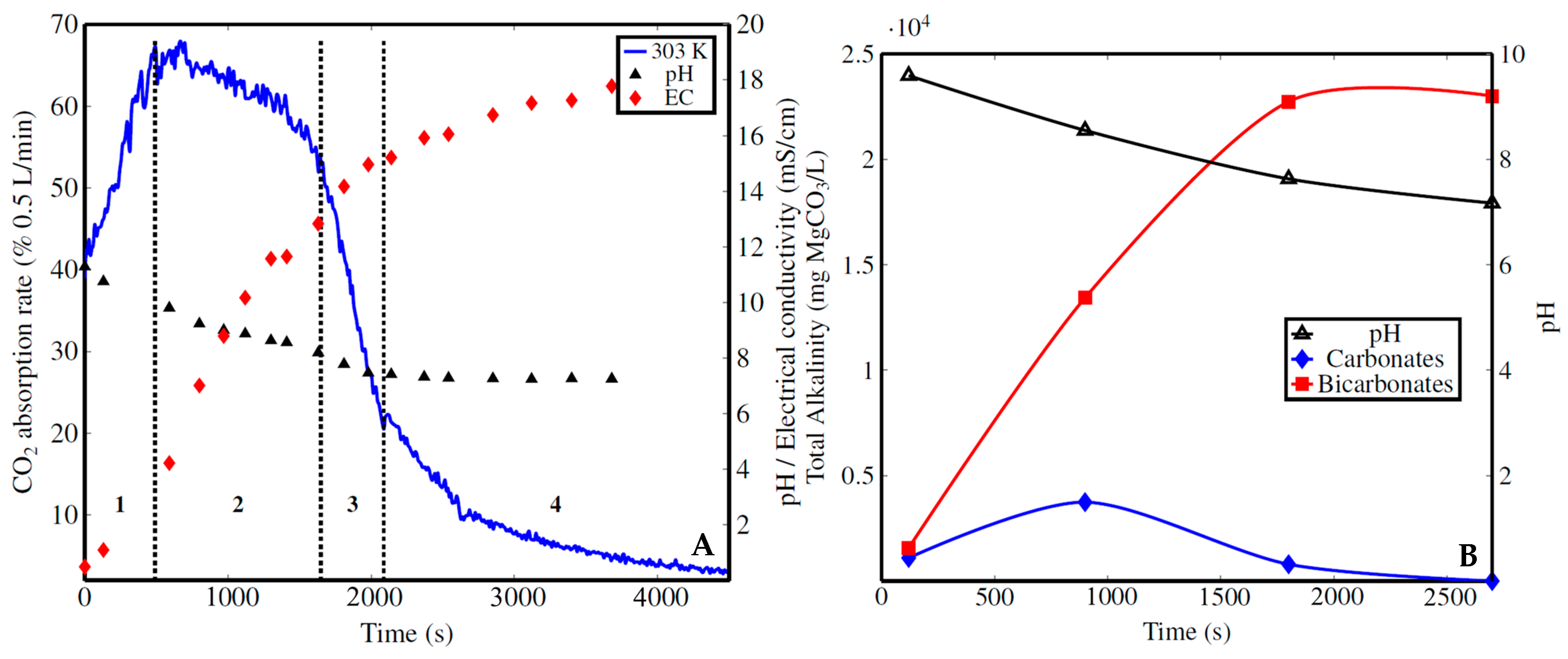

3.3. CO2 Capture Rate vs. Time : General Insights

3.4. Impact of Operational Parameters on CO2 Absorption During MgO Aqueous Carbonation

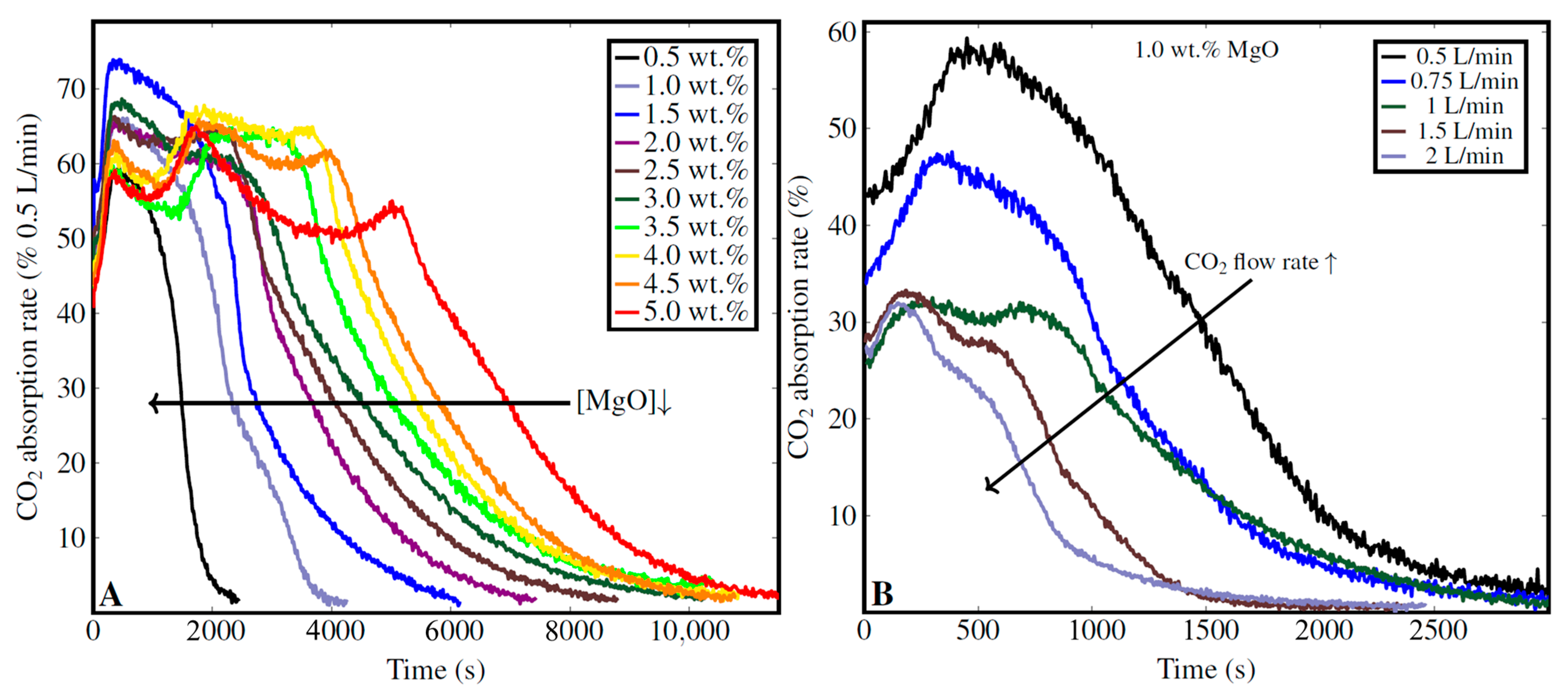

3.4.1. Impact of MgO Concentration and CO2 Flow Rate

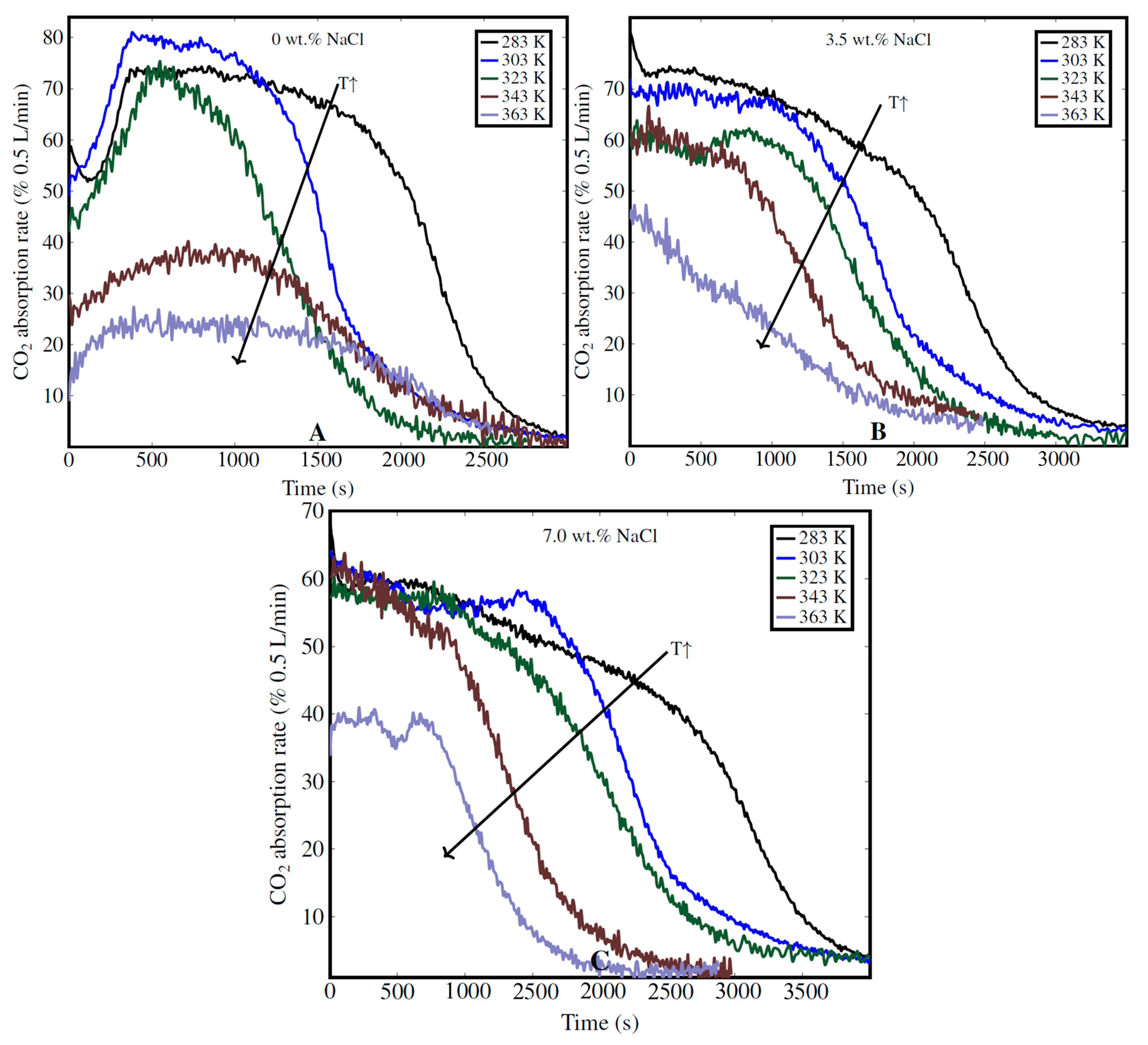

3.4.2. Impact of Temperature and NaCl Concentration

3.4.3. Impact of Na2SO4 and K2SO4 Concentration

3.4.4. Impact of Mixing System

3.5. Comparing Pure CaO- and MgO-Based Mineral Carbonation Systems: Impact of Operational Parameters During Aqueous Carbonation

3.5.1. Impact of Mixing System on

3.5.2. Impact of NaCl, Na2SO4 and K2SO4 on

| Parameter/Effect | CaO System | MgO System | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical pH | >11.7 | <11.3 | [5]; this study |

| Precipitated phases | Cal is the predominant phase, being thermodynamically stable, whereas Vat, the intermediate between amorphous CaCO3 and Cal, can persist at ≈30 °C. | Nes, Hmgs, and Dyp predominate under near-ambient P/T conditions, whereas Mgs dominates at higher P/T. | [78,79] |

| CO2 absorption rate | Faster than MgO under most equivalent thermo-hydro-mechanical-chemical conditions. | Generally slower, but can match or slightly exceed CaO at low temperatures with enhanced gas–solid–liquid mixing. | This study; [47] |

| Effect of CO2 partial pressure | Rapid carbonation at low pCO2 due to high solubility; limited further enhancement beyond saturation | Strongly dependent on pCO2; higher pCO2 accelerates Mg2+ release and favors stable carbonate precipitation such as Mgs | [70,80,81,82] |

| Effect of Temperature | Stabilizes Cal, increases carbonation kinetics up to ≈343 K and CO2 uptake | Precipitation of less hydrated and more stable carbonate phases, steep decrease in carbonation kinetics and CO2 uptake with temperature due to lower CO2 solubility and bicarbonate formation. However, Mg-silicate carbonation is dissolution-controlled and requires high temperatures. | This study; [47,83] |

| Chloride impurities | Strong, near-optimal enhancement at 3.5 wt.% (seawater level) at ambient temperature | Only significant at >323 K | This study; [47,84,85] |

| Sulfate impurities | Among the tested salts (NaCl, KCl, K2SO4, Na2SO4), Na2SO4 was the most efficient, enhancing the CO2 absorption rate by up to 75%. K2SO4 was also highly effective at low concentrations (<2 wt.%) | Slightly enhance the absorption rate at low concentrations (<2 wt.%) but reduce it at higher levels, with no significant impact on the CO2 uptake | [47,86]; this study; [87] |

| Effect of mixing system | A gas–liquid spargers with an impeller generate microbubbles and well-dispersed suspensions, enhancing CO2 absorption. | Optimizing the mixing system is even more critical than for CaO, due to slower dissolution–precipitation kinetics. | [76,88,89,90,91] |

| Metastable bicarbonate formation | Negligible due to the very low concentration and limited persistence of Ca(HCO3)2 in solution. | Mg(HCO3)2 forms at <303 K, increasing CO2 uptake up to 2× that of the CaO system. | [45,92]; This study; [47] |

| Operational/fouling behavior | Heavy deposit formation; frequent clogging of spargers and porous tools. | Fewer reactor deposits; slurries harden at flask bottom, requiring direct powder addition. | This study; [47] |

3.5.3. Impact of Temperature on

3.5.4. Formation of Metastable Bicarbonate

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BET | Brunauer–Emmett–Teller |

| CCS | Carbon Capture and Storage |

| DAC | Direct Air Capture |

| Dyp | Dypingite |

| EC | Electrolytical Conductivity |

| EDS | Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy |

| Hmgs | Hydromagnesite |

| kgw | Kilogram of water |

| L/S | Liquid-to-solid ratio |

| LDH | Layer Double Hydroxides |

| Lfd | Landsfordite |

| Mgs | Magnesite |

| Nes | Nesquehonite |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscope |

| SSA | Specific Surface Area |

| XRPD | X-Ray Powder Diffraction |

Appendix A. Detailed Experimental Parameters Investigated

| Experiment Identifier | [MgO]0 | CO2 Flow Rate | Temperature | [Salt] | Mixing System | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt.% | L/min | K | wt.% | - | ||

| Group 1 | A1 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 278 | 0 | sparger + stirrer |

| A2 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 278 | 3.5 | sparger + stirrer | |

| Group 2 | B1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 278 | 0 | sparger + stirrer |

| B2 | 1 | 0.5 | 278 | 0 | sparger + stirrer | |

| B3 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 278 | 0 | sparger + stirrer | |

| B4 | 2 | 0.5 | 278 | 0 | sparger + stirrer | |

| B5 | 2.5 | 0.5 | 278 | 0 | sparger + stirrer | |

| B6 | 3 | 0.5 | 278 | 0 | sparger + stirrer | |

| B7 | 3.5 | 0.5 | 278 | 0 | sparger + stirrer | |

| B8 | 4 | 0.5 | 278 | 0 | sparger + stirrer | |

| B9 | 4.5 | 0.5 | 278 | 0 | sparger + stirrer | |

| B10 | 5 | 0.5 | 278 | 0 | sparger + stirrer | |

| Group 3 | C1 | 1 | 0.5 | 303 | 0 | sparger + stirrer |

| C2 | 1 | 0.75 | 303 | 0 | sparger + stirrer | |

| C3 | 1 | 1 | 303 | 0 | sparger + stirrer | |

| C4 | 1 | 1.5 | 303 | 0 | sparger + stirrer | |

| C5 | 1 | 2 | 303 | 0 | sparger + stirrer | |

| Group 4 | D1 | 1 | 0.5 | 283 | 0 | sparger + stirrer |

| D2 | 1 | 0.5 | 303 | 0 | sparger + stirrer | |

| D3 | 1 | 0.5 | 323 | 0 | sparger + stirrer | |

| D4 | 1 | 0.5 | 343 | 0 | sparger + stirrer | |

| D5 | 1 | 0.5 | 363 | 0 | sparger + stirrer | |

| D6 | 1 | 0.5 | 283 | 3.5 [NaCl] | sparger + stirrer | |

| D7 | 1 | 0.5 | 303 | 3.5 [NaCl] | sparger + stirrer | |

| D8 | 1 | 0.5 | 323 | 3.5 [NaCl] | sparger + stirrer | |

| D9 | 1 | 0.5 | 343 | 3.5 [NaCl] | sparger + stirrer | |

| D10 | 1 | 0.5 | 363 | 3.5 [NaCl] | sparger + stirrer | |

| D11 | 1 | 0.5 | 283 | 7 [NaCl] | sparger + stirrer | |

| D12 | 1 | 0.5 | 303 | 7 [NaCl] | sparger + stirrer | |

| D13 | 1 | 0.5 | 323 | 7 [NaCl] | sparger + stirrer | |

| D14 | 1 | 0.5 | 343 | 7 [NaCl] | sparger + stirrer | |

| D15 | 1 | 0.5 | 363 | 7 [NaCl] | sparger + stirrer | |

| Group 5 | E1 | 1 | 0.5 | 303 | 1 [Na2SO4] | sparger + stirrer |

| E2 | 1 | 0.5 | 303 | 3.5 [Na2SO4] | sparger + stirrer | |

| E3 | 1 | 0.5 | 303 | 7 [Na2SO4] | sparger + stirrer | |

| E4 | 1 | 0.5 | 303 | 10.5 [Na2SO4] | sparger + stirrer | |

| Group 6 | F1 | 1 | 0.5 | 303 | 1 [K2SO4] | sparger + stirrer |

| F2 | 1 | 0.5 | 303 | 3.5 [K2SO4] | sparger + stirrer | |

| F3 | 1 | 0.5 | 303 | 7 [K2SO4] | sparger + stirrer | |

| F4 | 1 | 0.5 | 303 | 10.5 [K2SO4] | sparger + stirrer | |

| Group 7 | G1 | 1 | 0.5 | 303 | 0 | pipe + stirrer |

Appendix B. Phreeqc Geochemical Models

| Phreeqc script to calculate the brucite solubility as a function of temperature between 273–373 K. #Use the sit.dat or wateq4f.dat databases SOLUTION 1 density 1 -water 1 # kg INCREMENTAL_REACTIONS EQUILIBRIUM_PHASES Brucite 0 1 REACTION_TEMPERATURE 1 0 100 in 50 steps USE solution 1 USER_GRAPH 1 -headings Brucite -chart_title "Brucite Solubility vs Temperature" -axis_scale x_axis 0 100 5 0 -axis_scale y_axis auto -axis_titles "Temperature (°C)" "Solubility (g/L)" -initial_solutions false -start 10 PLOT_XY TC, (1-EQUI("Brucite"))*58.319 y-axis = 1 -end END |

| Phreeqc script to calculate the brucite solubility as a function of [NaCl] concentration. #Use the pitzer.dat database SOLUTION 1 temp 20 density 1 -water 1 # kg INCREMENTAL_REACTIONS 1 REACTION 1 NaCl 1 4 moles in 60 steps EQUILIBRIUM_PHASES 1 Brucite 0 1 USE solution 1 USER_GRAPH 1 -chart_title "Brucite/CO2(g) solubilities vs NaCl concentration" -headings Brucite -axis_scale x_axis 0 250 20 0 -axis_titles "NaCl concentration (g/L)" "Mg(OH)2(s) solubility (g/L)" "CO2(g) solubility (g/L)" -initial_solutions false -start 20 graph_y (1-EQUI("Brucite"))*58.32 # tot("Mg") provide Mg(OH)2 solubility in molality (mol/kgw) 80 graph_x totmole("Na")*58.44 -end END |

| Phreeqc script to calculate the pH, saturation index and ion activities variations for the Mg(OH)2-H2O-CO2 system when CO2 is absorbed by a Mg(OH)2 suspension. #Use with minteq.v4.dat database SOLUTION 1 temp 20 pH 7 pe 4 redox pe units g/kgw density 1 -water 0.5 # kg EQUILIBRIUM_PHASES 1 Brucite 5 0.50612 #Similar to Ca(OH)2 study (Wehrung et al., 2024) [47] #SiO2(am) 5 0.01 GAS_PHASE -fixed_pressure -pressure 1.2 -volume 1e-8 -temperature 20 REACTION 1 CO2(g) 1 1 mole in 50 steps USER_GRAPH 1 -chart_title "Hmgs_Nes SI & Ions activities & pH vs CO2" -headings HmgsSI NesSI*10 pH activity(Mg+2)*100 activity(MgOH+)*100 activity(MgHCO3+)*10 activity(MgCO3)*10 activity(CO3-2)*100 activity(HCO3-) activity(OH-) -axis_scale x_axis 0 1 0.2 0 -axis_scale y_axis 0 20 5 0 -axis_titles "CO2 absorbed (mol)" "Sat. Index/ Activity count" "pH" -start 10 graph_y si("Hydromagnesite") 15 graph_y si("Nesquehonite")*10 20 graph_sy -la("H+") 30 graph_y act("Mg+2")*100 40 graph_y act("MgOH+")*100 50 graph_y act("MgHCO3+")*10 60 graph_y act("MgCO3")*10 70 graph_y act("CO3-2")*100 80 graph_y act("HCO3-") 90 graph_y act("OH-") 100 graph_x totmole("C") -end END |

| Phreeqc script to calculate the dissolution kinetic of brucite in water as a function of temperature between 283 K and 343 K. # Use the sit.dat database # MgO SSA was measured by BET; SSA = 31.886 m2/g ± 0.0907. Once converted SSA = 1.283613344E7 cm2/mol. Here this same value was used for Mg(OH)2 (brucite) SOLUTION 1 temp 10 #temperature in °C, to be adjusted if needed pH 7 redox pe density 1 -water 0.5 # kg INCREMENTAL_REACTIONS true RATES 1 Brucite -start 1 rem unit should be mol, kgw-1 and second-1 2 rem PARM(1)= specific surface area of MgO, cm^2/mol 3 rem PARM(2)= exponent for M/M0 (empirical parm) 11 a1=4.00E+05 12 E1=59000 13 n1=0.5 20 rem neutral solution parameters 21 a2=1.30E-01 22 E2=42000 30 rem base solution parameters 31 a3=4.80E-06 32 E3=25000 33 n3=0.5 40 SR_mineral=SR("Brucite") 42 if (M<=0 and SR_mineral<1) then goto 200 43 if (M0<=0) then SA=PARM(1)*M else SA=PARM(1)*M0*(M/M0)^PARM(2) 60 R=8.31451 75 k1=a1*EXP(-E1/R/TK)*ACT("H+")^n1 #acid rate expression 80 k2=a2*EXP(-E2/R/TK) #neutral rate expression 85 k3=a3*EXP(-E3/R/TK)*ACT("OH-")^n3 #base rate expression 90 AF = 1 - SR_mineral 91 IF (AF < 0) THEN AF = 0 92 Rate = (k1+k2+k3)*AF*SA 100 moles= Rate*Time 200 save moles -end KINETICS 1 Brucite -formula Mg(OH)2 1 -M0 0.4287 # 25g of Mg(OH)2 = 0.4287 mol -parms 1.283613344E7 2/3 # [PARM(1)]=cm^2/mol ; [PARM(2)] = exponent for M/M0 -step 0.012 in 100 steps -tol 1e-6 -cvode true -end END |

| (suite) Phreeqc script to calculate the dissolution kinetic of brucite in water as a function of temperature between 283K and 343K. Copy this block with increased reaction temperature as much as needed USE SOLUTION 1 RATES 2 Brucite # pre-exponent coefficient A is calculated from logk using equation A=k/exp(-Ea/RT) -start 1 rem unit should be mol, kgw-1 and second-1 2 rem PARM(1)= specific surface area of MgO, cm^2/mol 3 rem PARM(2)= exponent for M/M0 (empirical parm) 11 a1=4.00E+05 12 E1=59000 13 n1=0.500 20 rem neutral solution parameters 21 a2=1.30E-01 22 E2=42000 30 rem base solution parameters 31 a3=4.80E-06 32 E3=25000 33 n3=0.5 40 SR_mineral=SR("Brucite") 42 if (M<=0 and SR_mineral<1) then goto 200 43 if (M0<=0) then SA=PARM(1)*M else SA=PARM(1)*M0*(M/M0)^PARM(2) 60 R=8.31451 75 k1=a1*EXP(-E1/R/TK)*ACT("H+")^n1 #acid rate expression 80 k2=a2*EXP(-E2/R/TK) #neutral rate expression 85 k3=a3*EXP(-E3/R/TK)*ACT("OH-")^n3 #base rate expression 90 AF = 1 - SR_mineral 91 IF (AF < 0) THEN AF = 0 92 Rate = (k1+k2+k3)*AF*SA 100 moles= Rate*Time 200 save moles -end KINETICS 2 Brucite -formula Mg(OH)2 1 -m0 0.4287 # 25g of MgO = 0.4287 mol -parms 1.283613344E7 2/3 # [PARM(1)]=cm^2/mol ; [PARM(2)] = exponent for M/M0 -step 0.012 in 100 steps -tol 1e-6 -cvode true REACTION_TEMPERATURE 2 30 #temperature in °C END |

| Phreeqc script to calculate the dissolution kinetic of brucite in water as a function of NaCl concentration between 0 and 2.5M. # Use the sit.dat database SOLUTION 1 temp 20 pH 7 redox pe density 1 -water 0.5 # kg INCREMENTAL_REACTIONS true RATES 1 Brucite # pre-exponent coefficient A is calculated from logk using equation A=k/exp(-Ea/RT) -start 1 rem unit should be mol, kgw-1 and second-1 2 rem PARM(1)= specific surface area of MgO, cm^2/mol 3 rem PARM(2)= exponent for M/M0 (empirical parm) 11 a1=4.00E+05 12 E1=59000 13 n1=0.5 20 rem neutral solution parameters 21 a2=1.30E-01 22 E2=42000 30 rem base solution parameters 31 a3=4.80E-06 32 E3=25000 33 n3=0.5 40 SR_mineral=SR("Brucite") 42 if (M<=0 and SR_mineral<1) then goto 200 43 if (M0<=0) then SA=PARM(1)*M else SA=PARM(1)*M0*(M/M0)^PARM(2) 60 R=8.31451 75 k1=a1*EXP(-E1/R/TK)*ACT("H+")^n1 #acid rate expression 80 k2=a2*EXP(-E2/R/TK) #neutral rate expression 85 k3=a3*EXP(-E3/R/TK)*ACT("OH-")^n3 #base rate expression 90 AF = 1 - SR_mineral 91 IF (AF < 0) THEN AF = 0 92 Rate = (k1+k2+k3)*AF*SA 100 moles= Rate*Time 200 save moles -end KINETICS 1 Brucite -formula Mg(OH)2 1 -M0 0.4287 # 25g of Mg(OH)2 = 0.4287 mol -parms 1.283613344E7 2/3 # [PARM(1)]=cm^2/mol ; [PARM(2)] = exponent for M/M0 -step 0.012 in 100 steps -tol 1e-6 -cvode true END |

| Phreeqc script to calculate the dissolution kinetic of brucite in water as a function of NaCl concentration between 0 and 2.5 M. Copy this block with increased NaCl quantity as much as needed USE SOLUTION 1 REACTION 1 NaCl 1 0.05 mol in 1 step RATES 2 Brucite -start 1 rem unit should be mol, kgw-1 and second-1 2 rem PARM(1)= specific surface area of MgO, cm^2/mol 3 rem PARM(2)= exponent for M/M0 (empirical parm) 11 a1=4.00E+05 12 E1=59000 13 n1=0.5 20 rem neutral solution parameters 21 a2=1.30E-01 22 E2=42000 30 rem base solution parameters 31 a3=4.80E-06 32 E3=25000 33 n3=0.5 40 SR_mineral=SR("Brucite") 42 if (M<=0 and SR_mineral<1) then goto 200 43 if (M0<=0) then SA=PARM(1)*M else SA=PARM(1)*M0*(M/M0)^PARM(2) 60 R=8.31451 75 k1=a1*EXP(-E1/R/TK)*ACT("H+")^n1 #acid rate expression 80 k2=a2*EXP(-E2/R/TK) #neutral rate expression 85 k3=a3*EXP(-E3/R/TK)*ACT("OH-")^n3 #base rate expression 90 AF = 1 - SR_mineral 91 IF (AF < 0) THEN AF = 0 92 Rate = (k1+k2+k3)*AF*SA 100 moles= Rate*Time 200 save moles -end KINETICS 2 Brucite -formula Mg(OH)2 1 -m0 0.4287 # 25g of MgO = 0.4287 mol -parms 1.283613344E7 2/3 # [PARM(1)]=cm^2/mol ; [PARM(2)] = exponent for M/M0 -step 0.012 in 100 steps -tol 1e-6 -cvode true END |

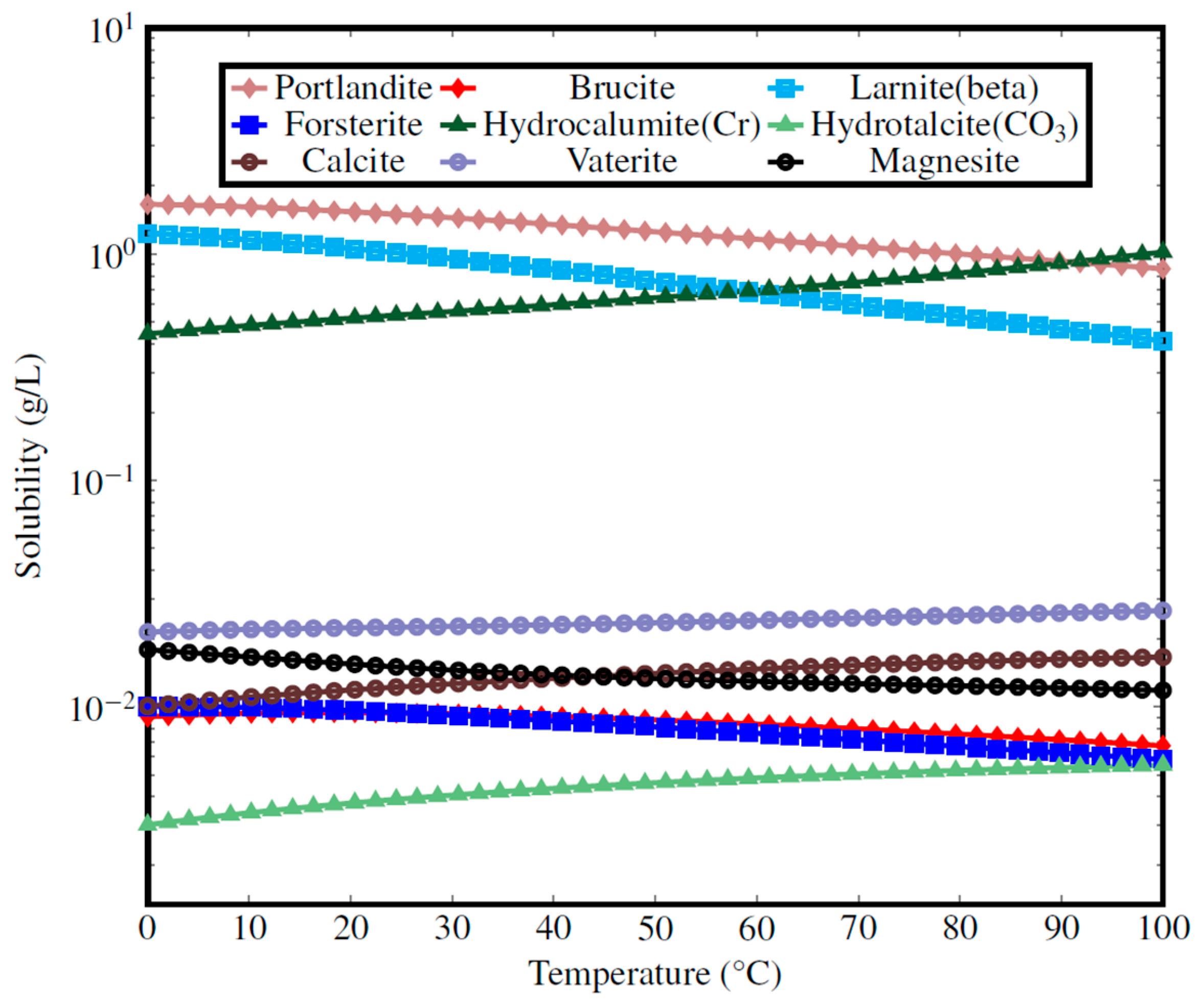

Appendix C. Solubility Modeling of Typical Ca- and Mg-Based Minerals

Appendix D. Comparison of Ca(OH)2 and MgO Aqueous Carbonation Under Optimized Conditions

| Experiment Identifier | SSA | [Reagent] | Temperature | Constants | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m2/g | wt.% | K | - | % | % | L | |

| SPR1 | 16 | 1.5 [Ca(OH)2] | 303 | 1.2 kgw, CO2 0.5 L/min, PCO2 1.2 bar, CO2 100 vol.%, sparger, stirrer 300 rpm, pure system (no NaCl, no salts) | 37.9 | 64.8 | 3.73 |

| B3 | 31.9 | 1.5 [MgO] | 278 | 33.1 | 73.9 | 17 | |

| D2 | 31.9 | 1 [MgO] | 303 | 39.13 | 81.52 | 10.29 |

References

- Sanna, A.; Uibu, M.; Caramanna, G.; Kuusik, R.; Maroto-Valer, M.M. A review of mineral carbonation technologies to sequester CO2. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 8049–8080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snæbjörnsdóttir, S.Ó.; Sigfússon, B.; Marieni, C.; Goldberg, D.; Gislason, S.R.; Oelkers, E.H. Carbon dioxide storage through mineral carbonation. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Chai, Y.E.; Santos, R.M.; Šiller, L. Advances in process development of aqueous CO2 mineralisation towards scalability. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, C.D.; Tripathi, N.; Carey, P.J. Managed pathways for CO2 mineralisation: Analogy with nature and potential contribution to CCUS-led reduction targets. Faraday Discuss. 2021, 230, 152–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Back, M.; Bauer, M.; Stanjek, H.; Peiffer, S. Sequestration of CO2 after reaction with alkaline earth metal oxides CaO and MgO. Appl. Geochem. 2011, 26, 1097–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballirano, P.; De Vito, C.; Mignardi, S.; Ferrini, V. Phase transitions in the MgCO2H2O system and the thermal decomposition of dypingite, Mg5(CO3)4(OH)2·5H2O: Implications for geosequestration of carbon dioxide. Chem. Geol. 2013, 340, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, H.S.; Nguyen, H.; Venâncio, F.; Ramteke, D.; Zevenhoven, R.; Kinnunen, P. Mechanisms of Mg carbonates precipitation and implications for CO2 capture and utilization/storage. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2023, 10, 2507–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botha, A.; Strydom, C.A. Preparation of a magnesium hydroxy carbonate from magnesium hydroxide. Hydrometallurgy 2001, 62, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldi, G.D.; Schott, J.; Pokrovsky, O.S.; Gautier, Q.; Oelkers, E.H. An experimental study of magnesite precipitation rates at neutral to alkaline conditions and 100–200 °C as a function of pH, aqueous solution composition and chemical affinity. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2012, 83, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, E.J.; Fricker, K.J.; Sun, M.; Park, A.H. Directed precipitation of hydrated and anhydrous magnesium carbonates for carbon storage. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 23440–23450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toroz, D.; Song, F.; Di Tommaso, D. New insights into the role of solution additive anions in Mg2+ dehydration: Implications for mineral carbonation. CrystEngComm 2021, 23, 4896–4900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, A.L.; Oelkers, E.H.; Bénézeth, P. Solubility of the hydrated Mg-carbonates nesquehonite and dypingite from 5 to 35 °C: Implications for CO2 storage and the relative stability of Mg-carbonates. Chem. Geol. 2019, 504, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasser, F.P.; Jauffret, G.; Morrison, J.; Galvez-Martos, J.L.; Patterson, N.; Imbabi, M.S. Sequestering CO2 by mineralization into useful nesquehonite-based products. Front. Energy Res. 2016, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.M.; Van Audenaerde, A.; Chiang, Y.W.; Iacobescu, R.I.; Knops, P.; Van Gerven, T. Nickel extraction from olivine: Effect of carbonation pre-treatment. Metals 2015, 5, 1620–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.M.; Knops, P.C.; Rijnsburger, K.L.; Chiang, Y.W. CO2 energy reactor–integrated mineral carbonation: Perspectives on lab-scale investigation and products valorization. Front. Energy Res. 2016, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Dreisinger, D.; Jarvis, M.; Hitchins, T. Kinetics and mechanism of mineral carbonation of olivine for CO2 sequestration. Miner. Eng. 2019, 131, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Dreisinger, D.; Jarvis, M.; Hitchins, T. Kinetic evaluation of mineral carbonation of natural silicate samples. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 404, 126522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Dreisinger, D.; Xiao, Y. Accelerated CO2 mineralization and utilization for selective battery metals recovery from olivine and laterites. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 393, 136345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Dreisinger, D. Enhanced CO2 mineralization and selective critical metal extraction from olivine and laterites. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 321, 124268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Dreisinger, D. An integrated process of CO2 mineralization and selective nickel and cobalt recovery from olivine and laterites. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 451, 139002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Dreisinger, D.B. Acceleration of iron-rich olivine CO2 mineral carbonation and utilization for simultaneous critical nickel and cobalt recovery. Minerals 2024, 14, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelemen, P.B.; Matter, J. In situ carbonation of peridotite for CO2 storage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 17295–17300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelemen, P.B.; Matter, J.; Streit, E.E.; Rudge, J.F.; Curry, W.B.; Blusztajn, J. Rates and mechanisms of mineral carbonation in peridotite: Natural processes and recipes for enhanced, in situ CO2 capture and storage. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2011, 39, 545–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, A.L.; Power, I.M.; Dipple, G.M. Accelerated carbonation of brucite in mine tailings for carbon sequestration. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarandi, A.E.; Larachi, F.; Beaudoin, G.; Plante, B.; Sciortino, M. Multivariate study of the dynamics of CO2 reaction with brucite-rich ultramafic mine tailings. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2016, 52, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemache, N.; Pasquier, L.C.; Cecchi, E.; Mouedhen, I.; Blais, J.F.; Mercier, G. Aqueous mineral carbonation for CO2 sequestration: From laboratory to pilot scale. Fuel Process. Technol. 2017, 166, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, R.K.; Serra-Maia, R.; Shi, Y.; Psarras, P.; Vojvodic, A.; Stach, E.A. Enhanced mineral carbonation on surface functionalized MgO as a proxy for mine tailings. Environ. Sci. Nano 2025, 12, 2630–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.M.; Ling, D.; Sarvaramini, A.; Guo, M.; Elsen, J.; Larachi, F.; Van Gerven, T. Stabilization of basic oxygen furnace slag by hot-stage carbonation treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 203, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.M.; Van Bouwel, J.; Vandevelde, E.; Mertens, G.; Elsen, J.; Van Gerven, T. Accelerated mineral carbonation of stainless steel slags for CO2 storage and waste valorization: Effect of process parameters on geochemical properties. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2013, 17, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Librandi, P.; Costa, G.; de Souza, A.C.; Stendardo, S.; Luna, A.S.; Baciocchi, R. Carbonation of steel slag: Testing of the wet route in a pilot-scale reactor. Energy Procedia 2017, 114, 5381–5392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leventaki, E.; Queiroz, E.C.; Pisharody, S.K.; Kumar, A.K.; Ho, P.H.; Andersson-Sarning, M.; Bernin, D. Aqueous mineral carbonation of three different industrial steel slags: Absorption capacities and product characterization. Environ. Res. 2024, 252, 118903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; So, S.; Lim, Y. Carbonation, CO2 sequestration, and physical properties based on the mineral size of light burned MgO using carbonation accelerator. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 379, 134648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardeh, M.G.; Kistanov, A.A.; Nguyen, H.; Manzano, H.; Cao, W.; Kinnunen, P. Exploring mechanisms of hydration and carbonation of MgO and Mg(OH)2 in reactive magnesium oxide-based cements. J. Phys. Chem. C 2022, 126, 6196–6206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandeperre, L.J.; Al-Tabbaa, A. Accelerated carbonation of reactive MgO cements. Adv. Cem. Res. 2007, 19, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernasconi, D.; Viani, A.; Zárybnická, L.; Bordignon, S.; Godinho, J.R.; Maximenko, A.; Pavese, A. Setting reaction of an olivine-based Mg-phosphate cement. Cem. Concr. Res. 2024, 186, 107694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymoniak, L.; Claveau-Mallet, D.; Haddad, M.; Barbeau, B. Application of magnesium oxide media for remineralization and removal of divalent metals in drinking water treatment: A review. Water 2022, 14, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Yu, W.; Du, X.; Shen, A.; Li, Y.; Ding, H.; Wu, F. Investigating lightweight carbonation curing of waste slurry using activated magnesium oxide: Performance insights. Materials 2025, 18, 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Qin, J.; Yi, Y. Carbonating MgO for treatment of manganese- and cadmium-contaminated soils. Chemosphere 2021, 263, 128311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.Y.; Cai, G.H.; Liu, S.Y.; Zhong, Y.Q.; Liu, T.Y.; Poon, C.S. Influence of organic matter and carbonation time on engineering performance of reactive MgO carbonated soils. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 104, 112257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQueen, N.; Kelemen, P.; Dipple, G.; Renforth, P.; Wilcox, J. Ambient weathering of magnesium oxide for CO2 removal from air. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormos, C.C. Techno-economic assessment of calcium and magnesium-based sorbents for post-combustion CO2 capture applied in fossil-fueled power plants. Fuel 2021, 298, 120794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Dong, H.; Zhou, Z. A cadmium-magnesium looping for stable thermochemical energy storage and CO2 capture at intermediate temperatures. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 425, 131428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rausis, K.; Stubbs, A.R.; Power, I.M.; Paulo, C. Rates of atmospheric CO2 capture using magnesium oxide powder. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2022, 119, 103701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, W.D. The solubility of magnesium carbonate (nesquehonite) in water at 25 and pressures of carbon dioxide up to one atmosphere. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1929, 51, 2093–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.L.; Clair, H.W. Carbonation of aqueous suspensions containing magnesium oxides or hydroxides. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1949, 41, 2814–2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, T.K.; Dlugogorski, B.Z.; Kennedy, E.M. Biologically enhanced degassing and precipitation of magnesium carbonates derived from bicarbonate solutions. Miner. Eng. 2014, 61, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrung, Q.; Pastero, L.; Bernasconi, D.; Cotellucci, A.; Bruno, M.; Cavagna, S.; Pavese, A. Impact of operational parameters on the CO2 absorption rate in Ca(OH)2 aqueous carbonation—Implications for process efficiency. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 16678–16691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkhurst, D.L.; Appelo, C.A.J. Description of input and examples for PHREEQC version 3—A computer program for speciation, batch-reaction, one-dimensional transport, and inverse geochemical calculations. U.S. Geol. Surv. Bull. 2013, 6, 497. [Google Scholar]

- Caserini, S.; Cappello, G.; Righi, D.; Raos, G.; Campo, F.; De Marco, S.; Grosso, M. Buffered accelerated weathering of limestone for storing CO2: Chemical background. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2021, 112, 103517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Zhang, G.; Apps, J.; Zhu, C. Comparison of thermodynamic data files for PHREEQC. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2022, 225, 103888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, O.; Kadkhodaie, A.; Highfield, J. Kinetics analysis of CO2 mineral carbonation using byproduct red gypsum. Energy Fuels 2016, 30, 7460–7464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, B.; Teng, Y.; Tu, K.; Zhu, C. A library of BASIC scripts of reaction rates for geochemical modeling using PHREEQC. Comput. Geosci. 2019, 133, 104316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, L.F.; Oliveira, I.R.; Salomão, R.; Frollini, E.; Pandolfelli, V.C. Temperature and common-ion effect on magnesium oxide (MgO) hydration. Ceram. Int. 2010, 36, 1047–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, H.K.; Lee, J.Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Z.; Keener, T.C. Dissolution kinetics of magnesium hydroxide for CO2 separation from coal-fired power plants. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 250, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hänchen, M.; Prigiobbe, V.; Baciocchi, R.; Mazzotti, M. Precipitation in the Mg-carbonate system—Effects of temperature and CO2 pressure. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2008, 63, 1012–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkinson, L.; Kristova, P.; Rutt, K.; Cressey, G. Phase transitions in the system MgO–CO2–H2O during CO2 degassing of Mg-bearing solutions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2012, 76, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Liu, W.; Chu, G.; Luo, D.; Zhang, G.; Wang, L.; Li, C. Aqueous carbonation of MgSO4 with (NH4)2CO3 for CO2 sequestration. Greenhouse Gases Sci. Technol. 2019, 9, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guermech, S.; Tebbiche, I.; Tran, L.H.; Mocellin, J.; Mercier, G.; Pasquier, L.C. Nesquehonite precipitation kinetics in an MSMPR crystallizer of the MgO–CO2–H2O system issued from activated serpentine carbonation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2025, 64, 11243–11254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Hui, T.; Sun, H.; Peng, T.; Ding, W. Synthesis of magnesium carbonate hydrate from natural talc. Open Chem. 2020, 18, 951–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C.E.; Henson, N.J.; Daemen, L.L.; Hartl, M.; Page, K. Uncovering the true atomic structure of disordered materials: The structure of a hydrated amorphous magnesium carbonate (MgCO3·3D2O). Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 2693–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricker, K.J.; Park, A.H.A. Investigation of the different carbonate phases and their formation kinetics during Mg(OH)2 slurry carbonation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 18170–18179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yan, C.; Zhang, F.; Konishi, H.; Xu, H.; Teng, H.H. Testing the cation-hydration effect on the crystallization of Ca–Mg–CO3 systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 17750–17755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, M.W. NIST–JANAF thermochemical tables. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1998, 28, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Altmaier, M.; Metz, V.; Neck, V.; Müller, R.; Fanghänel, T. Solid–liquid equilibria of Mg(OH)2(cr) and Mg2(OH)3Cl·4H2O(cr) in the system Mg–Na–H–OH–Cl–H2O at 25 °C. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2003, 67, 3595–3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautier, Q.; Bénézeth, P.; Mavromatis, V.; Schott, J. Hydromagnesite solubility product and growth kinetics in aqueous solution from 25 to 75 °C. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2014, 138, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robie, R.A.; Hemingway, B.S. The heat capacities at low temperatures and entropies at 298.15 K of nesquehonite, MgCO3·3H2O, and hydromagnesite. Am. Mineral. 1972, 57, 1768–1781. [Google Scholar]

- Robie, R.A.; Hemingway, B.S. Thermodynamic Properties of Minerals and Related Substances at 298.15 K and 1 bar (105 Pascals) Pressure and at Higher Temperatures; U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin, 1995; Volume 2131. Available online: https://books.google.fr/books?hl=en&lr=&id=FOx0hxWSWUYC&oi=fnd&pg=PA1&dq=Robie+%26+Hemingway+(1995)&ots=k_YdvyJIoj&sig=CR5mGR6j9HsSfs85yPHhzHlGtlY&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Robie%20%26%20Hemingway%20&f=false (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Stefánsson, A.; Bénézeth, P.; Schott, J. Potentiometric and spectrophotometric study of the stability of magnesium carbonate and bicarbonate ion pairs to 150 °C and aqueous inorganic carbon speciation and magnesite solubility. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2014, 138, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, H.; Hakuta, M.; Kudoh, K.; Ichinoseki, T.; Midorikawa, H. Chemical absorption into slurry in a gas-sparged stirred vessel under continuous operation. J. Chem. Eng. Jpn. 1989, 22, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes-Hernández, G.; Renard, F.; Geoffroy, N.; Charlet, L.; Pironon, J. Calcite precipitation from CO2–H2O–Ca(OH)2 slurry under high CO2 pressure. J. Cryst. Growth 2007, 308, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.J.; Yoo, M.; Kim, D.W.; Wee, J.H. Carbon dioxide capture using calcium hydroxide aqueous solution as the absorbent. Energy Fuels 2011, 25, 3825–3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes-Hernandez, G.; Renard, F.; Chiriac, R.; Findling, N. Rapid precipitation of magnesite microcrystals from Mg(OH)2–H2O–CO2 slurry enhanced by NaOH and a heat-aging step (from ∼20 to 90 °C). Cryst. Growth Des. 2012, 12, 5233–5240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrung, Q.; Bernasconi, D.; Cotellucci, A.; Destefanis, E.; Caviglia, C.; Bicchi, E.; Pavese, A.; Pastero, L. Carbonation washing of waste incinerator air pollution control residues under wastewater reuse conditions. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 13, 115272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrung, Q.; Bernasconi, D.; Destefanis, E.; Caviglia, C.; Curetti, N.; Di Felice, S.; Bicchi, E.; Pavese, A.; Pastero, L. Aqueous carbonation of waste incineration residues: Comparing BA, FA, and APCr across production scenarios. Minerals 2024, 14, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smithson, G.L.; Bakhshi, N.N. Kinetics and mechanism of carbonation of magnesium oxide slurries. Ind. Eng. Chem. Process Des. Dev. 1973, 12, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harja, M.; Cretescu, I.; Rusu, L.; Ciocinta, R.C. The influence of experimental factors on calcium carbonate morphology prepared by carbonation. Rev. Chim. 2009, 60, 1258–1263. [Google Scholar]

- Dennard, A.E.; Williams, R.J.P. The catalysis of the reaction between carbon dioxide and water. J. Chem. Soc. A Inorg. Phys. Theor. 1966, 812–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cizer, Ö.; Rodriguez-Navarro, C.; Ruiz-Agudo, E.; Elsen, J.; Van Gemert, D.; Van Balen, K. Phase and morphology evolution of calcium carbonate precipitated by carbonation of hydrated lime. J. Mater. Sci. 2012, 47, 6151–6165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Blanco, J.D.; Shaw, S.; Benning, L.G. The kinetics and mechanisms of amorphous calcium carbonate (ACC) crystallization to calcite via vaterite. Nanoscale 2011, 3, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerlund, J.; Highfield, J.; Zevenhoven, R. Kinetics studies on wet and dry gas–solid carbonation of MgO and Mg(OH)2 for CO2 sequestration. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 10380–10393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prigiobbe, V.; Mazzotti, M. Precipitation of Mg-carbonates at elevated temperature and partial pressure of CO2. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 223, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qafoku, O.; Dixon, D.A.; Rosso, K.M.; Schaef, H.T.; Bowden, M.E.; Arey, B.W.; Felmy, A.R. Dynamics of magnesite formation at low temperature and high pCO2 in aqueous solution. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 10736–10744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerlund, J.; Zevenhoven, R. An experimental study of Mg(OH)2 carbonation. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2011, 5, 1406–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, A.I.; Chimenos, J.M.; Segarra, M.; Fernandez, M.A.; Espiell, F. Kinetic study of carbonation of MgO slurries. Hydrometallurgy 1999, 53, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, M.; Zuo, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yin, X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, W.; Chen, Y. Crystallization of CaCO3 in aqueous solutions with extremely high concentrations of NaCl. Crystals 2019, 9, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.; Jang, Y.N.; Jo, H.Y. Influence of NaCl on mineral carbonation of CO2 using cement material in aqueous solutions. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2012, 80, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajac, M.; Skibsted, J.; Lothenbach, B.; Bullerjahn, F.; Skocek, J.; Haha, M.B. Effect of sulfate on CO2 binding efficiency of recycled alkaline materials. Cem. Concr. Res. 2022, 157, 106804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Hu, W.; Hou, L.; Deng, D. Effect of carbonation on physical sulfate attack on concrete by Na2SO4. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 193, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zheng, K.; Chen, L.; Yuan, Q. Review on accelerated carbonation of calcium-bearing minerals: Carbonation behaviors, reaction kinetics, and carbonation efficiency improvement. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 86, 108826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Kawai, T.; Kamijima, Y.; Shinohara, S.; Tanaka, M. Application of ultrafine bubbles for enhanced carbonation of municipal solid waste incineration ash during direct aqueous carbonation. Next Sustain. 2024, 3, 100020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Gu, Z.; Liu, F.; Shen, P.; Poon, C.S. A novel approach for improving aqueous carbonation kinetics with CO2 micro- and nano-bubbles. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 500, 157363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrung, Q.; Bernasconi, D.; Michel, F.; Destefanis, E.; Caviglia, C.; Curetti, N.; Pastero, L. Accelerated carbonation of waste incineration residues: Reactor design and process layout from laboratory to field scales—A review. Clean Technol. 2025, 7, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrung, Q. Accelerated Carbonation from Pure Ca/Mg Aqueous Systems to Hazardous Waste Incinerator Residues. Ph.D. Thesis, Earth Sciences Department, University of Turin, Turin, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Units | Ranges/Types |

|---|---|---|

| MgO initial concentration | wt.% | 0.5–5 |

| CO2 volumetric flow rate | L/min | 0.5 |

| Temperature | K | 278–363 |

| NaCl concentration | wt.% | 0–7 |

| Na2SO4 | wt.% | 0–10.5 |

| K2SO4 | wt.% | 0–10.5 |

| mixing system | - | pipe, sparger |

| Constants | Values/types | |

| MgO initial SSA | m2/g | 31.9 |

| water mass | kg | 1.2 |

| CO2 partial pressure | bar | 1.2 |

| CO2 concentration | Vol.% | 100 |

| stirrer speed | rpm | 300 |

| cylinder height × diameter | cm | 16.8 × 10 |

| Exp. ID. | [MgO]0 | σ | t | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt.% | % | % | - | s | L | |

| B1 | 0.5 | 34.3 | 59.7 | 22.5 | 2450 | 7.0 |

| B2 | 1.0 | 35.3 | 66.1 | 23.5 | 4253 | 12.5 |

| B3 | 1.5 | 33.1 | 73.9 | 27.1 | 6155 | 17.0 |

| B4 | 2.0 | 32.1 | 65.5 | 24.2 | 7432 | 19.9 |

| B5 | 2.5 | 30.5 | 66.3 | 24.2 | 8798 | 22.4 |

| B6 | 3.0 | 28.9 | 68.6 | 23.9 | 10,285 | 24.8 |

| B7 | 3.5 | 31.3 | 68.6 | 23.2 | 10,405 | 27.2 |

| B8 | 4.0 | 33.0 | 67.8 | 25.3 | 10,826 | 29.8 |

| B9 | 4.5 | 34.2 | 65.9 | 24.4 | 10,766 | 30.7 |

| B10 | 5.0 | 35.0 | 64.9 | 21.5 | 11,502 | 33.5 |

| Exp. ID. | [NaCl] | Temperature | σ | t | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt.% | K | % | % | - | s | L | |

| D1 | 0 | 283 | 47.63 | 74.83 | 27.25 | 3118 | 12.38 |

| D2 | 0 | 303 | 39.13 | 81.52 | 31.61 | 3155 | 10.29 |

| D3 | 0 | 323 | 36.93 | 76.52 | 26.01 | 2500 | 7.69 |

| D4 | 0 | 343 | 22.58 | 41.09 | 13.1 | 3000 | 5.65 |

| D5 | 0 | 363 | 15.7 | 25.63 | 6.65 | 2953 | 3.87 |

| D6 | 3.5 | 283 | 45.40 | 81.39 | 26.35 | 3545 | 13.41 |

| D7 | 3.5 | 303 | 33.76 | 73.98 | 27.95 | 3880 | 10.92 |

| D8 | 3.5 | 323 | 30.78 | 64.04 | 24.64 | 3419 | 8.77 |

| D9 | 3.5 | 343 | 31.88 | 65.46 | 22.09 | 2644 | 7.02 |

| D10 | 3.5 | 363 | 19.87 | 48.36 | 13.00 | 2468 | 4.09 |

| D11 | 7 | 283 | 37.45 | 64.57 | 13.73 | 4400 | 13.73 |

| D12 | 7 | 303 | 34.67 | 65.60 | 22.75 | 4000 | 11.56 |

| D13 | 7 | 323 | 33.66 | 60.87 | 21.01 | 3500 | 9.82 |

| D14 | 7 | 343 | 28.97 | 64.39 | 22.58 | 2850 | 6.88 |

| D15 | 7 | 363 | 21.67 | 41.44 | 15.10 | 2200 | 3.97 |

| Exp. ID. | [Na/-K2SO4] | σ | t | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt.% | % | % | - | s | L | |

| E1 | 1 | 27.4 | 63.6 | 24.0 | 3490 | 8.0 |

| E2 | 3.5 | 26.3 | 57.2 | 21.5 | 4100 | 9.0 |

| E3 | 7 | 26.2 | 53.7 | 20.5 | 4280 | 9.3 |

| E4 | 10.5 | 23.5 | 42.7 | 12.6 | 4320 | 8.5 |

| F1 | 1 | 29.4 | 64.0 | 24.9 | 2970 | 7.3 |

| F2 | 3.5 | 26.6 | 59.8 | 22.6 | 3415 | 7.6 |

| F3 | 7 | 25.5 | 54.3 | 19.1 | 3650 | 7.7 |

| F4 | 10.5 | 25.5 | 53.4 | 19.6 | 4100 | 8.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wehrung, Q.; Bernasconi, D.; Destefanis, E.; Caviglia, C.; Colli, A.; Michel, F.; Pavese, A.; Pastero, L. Impact of Operational Parameters on the CO2 Absorption Rate and Uptake in MgO Aqueous Carbonation—A Comparison with Ca(OH)2. Minerals 2025, 15, 1205. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15111205

Wehrung Q, Bernasconi D, Destefanis E, Caviglia C, Colli A, Michel F, Pavese A, Pastero L. Impact of Operational Parameters on the CO2 Absorption Rate and Uptake in MgO Aqueous Carbonation—A Comparison with Ca(OH)2. Minerals. 2025; 15(11):1205. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15111205

Chicago/Turabian StyleWehrung, Quentin, Davide Bernasconi, Enrico Destefanis, Caterina Caviglia, Alice Colli, Fabien Michel, Alessandro Pavese, and Linda Pastero. 2025. "Impact of Operational Parameters on the CO2 Absorption Rate and Uptake in MgO Aqueous Carbonation—A Comparison with Ca(OH)2" Minerals 15, no. 11: 1205. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15111205

APA StyleWehrung, Q., Bernasconi, D., Destefanis, E., Caviglia, C., Colli, A., Michel, F., Pavese, A., & Pastero, L. (2025). Impact of Operational Parameters on the CO2 Absorption Rate and Uptake in MgO Aqueous Carbonation—A Comparison with Ca(OH)2. Minerals, 15(11), 1205. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15111205