Abstract

Ear detection is an important step in ear recognition approaches. Most existing ear detection techniques are based on manually designing features or shallow learning algorithms. However, researchers found that the pose variation, occlusion, and imaging conditions provide a great challenge to the traditional ear detection methods under uncontrolled conditions. This paper proposes an efficient technique involving Multiple Scale Faster Region-based Convolutional Neural Networks (Faster R-CNN) to detect ears from 2D profile images in natural images automatically. Firstly, three regions of different scales are detected to infer the information about the ear location context within the image. Then an ear region filtering approach is proposed to extract the correct ear region and eliminate the false positives automatically. In an experiment with a test set of 200 web images (with variable photographic conditions), 98% of ears were accurately detected. Experiments were likewise conducted on the Collection J2 of University of Notre Dame Biometrics Database (UND-J2) and University of Beira Interior Ear dataset (UBEAR), which contain large occlusion, scale, and pose variations. Detection rates of 100% and 98.22%, respectively, demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed approach.

1. Introduction

Ear based human recognition technology is a novel research field in biometric identification. Compared with classical biometric identifiers such as fingerprint, face, and iris, the ear has its distinctive advantages. The ear has a stable and rich structure that changes little with age and does not suffer from facial expressions [1]. Moreover, the collection of ear images is deemed to be easy and non-intrusive. A traditional ear recognition system usually involves ear detection, feature extraction, and ear recognition. As the first stage, robust ear detection is a fundamental step for the whole system.

A majority of the widely known ear recognition approach focused on an ear recognition algorithm; the ear images were cropped manually. There exist a few techniques to crop the ear automatically from 2D profile face images. However, most of these techniques [2,3,4] performed poorly when the test images were photographed under uncontrolled conditions. Nevertheless, occlusion, post, and illumination variation are very common in practical application; this puts forward a challenging problem, which must be addressed.

Biometrics have developed rapidly over the years and taken a step forward from the experimental stage to practical application. There are plenty of research papers and application products based on face detection, and identification in the wild has been reported in recent years. However, research into ear detection and recognition in natural images has not been reported.

In the last decade, the deep learning algorithm has significantly advanced the state-of-the-art in computer vision. Numbers of vision tasks such as image classification [5,6], face recognition [7], and object detection [8] have obtained significant improved performance via deep learning models. The detection system based on Faster Region-based Convolutional Neural Networks (Faster R-CNN) model achieved state-of-the-art object detection accuracy [9].

In this paper, we proposed an ear detection system based on a Multiple Scale Faster R-CNN deep learning model to detect human ears in 2D images, which were photographed under uncontrolled conditions. We have trained a Faster R-CNN model to detect ears in natural images. However, it is found that the ear detection system based on traditional Faster R-CNN obtained an extremely low False Reject Rate (FRR) but a high False Acceptance Rate (FAR) in a realistic scenario. The complicated background and the other regions of a person’s body such as hands, eyes, or the nose in the image may be extracted inaccurately. Therefore, we design a modified ear detection system based on a Multiple Scale Faster R-CNN framework to solve this problem. We remove the threshold value part from the last step of the Faster R-CNN approach and connect an ear region filtering module to it. The proposed ear region filtering approach is utilized to distinguish the correct human ear from ear shaped objects based on the information of ear location context. The experimental result shows that the improved ear detection system outperforms state-of-the-art ear detection systems.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows: a review of related work and contributions is given in Section 2, and Section 3 presents the technical approach of the ear recognition system. In Section 4, a series of experiments and comparisons are purposed to evaluate the performance of the system. Finally, Section 5 provides the conclusions.

2. Related Work and Contribution

Current ear detection approaches exploited 2D images (including range images) or 3D point cloud data. This section discusses some well known and recent 2D ear detection methods from 2Dimages or range images and highlights the contributions of this paper.

2.1. Ear Detection

Detection and recognition are the two major components of an automatic biometrics system. In this section, a summary of ear detection approaches is provided. Basically, most of the ear detection approaches rely on the mutual morphological properties of the ear, such as the characteristic edges or frequency patterns. The first well known ear detection approach was proposed by Burge and Burger [10]. They proposed a detection approach utilizing deformable contours requiring user interaction for contour initialization, so it is not a fully automatic ear detection approach. Hurley et al. [11] proposed an approach that has gained some popularity, the force filed transform. However, it is only applicable when a small background is present in the ear image. A2Dear detection technique, combining geodesic active contours and a new ovoid model, has been developed by Alvarez et al. [12]. The ear contour was estimated using a snake model and ovoid model, but this method needs a manual first initial ear contour. Ansari and Gupta [13] used the canny edge detector to extract the outer helix edges for localization of the ear in the profile image. The experiments were done with the Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur database (IITK), which contains cut-out ear images. Hence it can be put into question whether it works under realistic conditions. A tracking method, which combined both skin-color model and intensity contour information, was proposed by Yuan and Mu [14] to detect and track the ear in sequence frames. Another ear detection technique is based on finding the elliptical shape of the ear using a Hough Transform (HT) accruing tolerance to noise and occlusion [15]. In [16], Cummings et al. utilized the image ray transform to detect ears. The transform was capable of highlighting tubular structures such as the helix of the ear and spectacle frames. The approach exploited the elliptical shape of the helix to perform the ear localization, but those methods will fail as the assumption of elliptical ear shape may not apply to all subjects in a real world application. Prakash and Gupta [17] presented a rotation, scale, and shape invariant technique for automatic localization of ear from side face images. The approach made use of the connected components in a graph, which was obtained from the edge map of the profile images. However, this technique may not be robust to background noise or minor hair covering around the ear.

Yan and Bowyer used a two-line landmark to perform detection [18]. One line was taken along the border between ear and profile and the other line from the top of the ear to the bottom. In their further approach, an automatic ear extracting method based on ear pit detection and an Active Contour Algorithm was exploited [19]. The ear pit was found using skin detection, curvature estimation, surface segmentation, and classification at first. Then an active contour algorithm was implemented to outline the ear region. However, because it has to locate the nose tip and ear pit on the profile image, this algorithm may not be robust to pose variations or hair covering either. Deepak Ret al. [20] proposed an ear detection method that was invariant to back ground and pose with the use of Snakes as active contour model. The proposed method encompassed two stages, namely, Snake-based Background Removal (SBR) and Snake-based Ear Localization (SEL). SBR was used to remove the background from a face image, and, thereafter, SEL was used to localize the ear. However, its computational time of 3.86 s per image cannot be ignored for an ear detection system.

Chen and Bbanu presented an approach for ear detection utilizing step edge magnitude [21]. They calculated the maximum distance in depth between the center point and its neighbors in a small window in a range image to get a binary edge image of the ear helix. In [22], Chen and Bbanu detected the ear with a shape model-based technique in side face range images. The step edges were extracted, dilated, thinned, and grouped into different clusters, which were potential regions containing ears. For each cluster, the ear shape model was registered with the edges. The region with the minimum mean registration error was declared to be the detected ear region. In a more recent work [23], Chen and Bbanu improved the extraction procedure of step edges. They used a skin color classifier to isolate the side face before extracting the step edges. The edges from the 2Dcolor image were combined with the step edges from the range image to locate regions-of-interest (ROIs) that might contain an ear. However, these ear extraction methods only work on profile images without any kind of rotation, pose, or scale variation and occultation. Ganesh and Krishna proposed an approach to detect ears in facial images under uncontrolled environments [24]. They proposed at echnique, namely Entropic Binary Particle Swarm Optimization (EBPSO), which generated an entropy map, the highest value of which was used to localize the ear in a face image. Also, Dual Tree Complex Wavelet Transform (DTCWT) based background pruning was used to eliminate most of the background in the face image. However, this method is computationally complex so that it costs 12.18s to detect an ear on average.

Researchers presented some ear detection approaches based on template matching. Anupam [25] utilized ear templates of different sizes to detect ears at different scales, but the ear templates may be unable to handle all the situations in practice. An automatic ear detection technique proposed by Prakash et al. [26] was based on a skin-color classifier and template matching. An ear template was created considering ears of various shapes and resized automatically to a size suitable for the detection. Nonetheless, it only works when the images only include facial parts, or else the other skin area may lead to an incorrect ear localization result. Attarchi et al. [27] proposed an ear detection method based on the edge map and the mean ear template. The canny edge detector was used to obtain the edges of the ear image. Then the longest path in the edge image was considered to be the outer boundary of the ear. Finally, the ear region was extracted using a predefined window, which was calculated using the mean ear template. It works well when there is a small background in the image and the performance will decrease if the approach is implemented in whole profile image. Halawani [28] proposed a shape-based ear localization approach. The idea was based on using a predefined binary ear template that was matched to ear contours in a given edge image. To cope with changes in ear shapes and sizes, the template was allowed to deform. The dynamic programming search algorithm was used to accomplish the matching process. In [29], an oval shape detection based approach was presented by Joshi for ear detection from 2D profile face images. The correctness of the detected ear was verified using a support vector machine tool.

The performance of ear detection approaches based on edges or templates might be declined when the profile face is influenced by partial occlusion, scaling, and rotation (pose variations). Therefore, some ear detection approaches based on learning algorithms such as cascaded AdaBoost were proposed to improve the performance of ear detection systems in the application scenario. Islam et al. [30] used Haar-like rectangular features as the weak classifiers. AdaBoost was utilized to select the best weak classifiers and then combine them into strong classifiers. Finally, a cascade of classifiers was built as the detector. Nevertheless, the training of the classifier takes several days. Abaza et al. [31] modified the Adaboost algorithm and reduced the training time significantly. Shih et al. [32] presented a two-step ear detection system, which utilized arc-masking candidate extraction and AdaBoost polling verification. Firstly, the ear candidates were extracted by an arc-masking edge search algorithm; then the ear was located by rough AdaBoost polling verification. Yuan and Mu [33] used an improved AdaBoost algorithm to detect ears against complex backgrounds. They speeded up the detection procedure and reported a good detection rate on three test data sets.

An overview of the ear detection methods mentioned above is presented in Table 1, along with the scale of test databases and reported accuracy rates. It is worth noting that most of the ear detection work in the table wastested on images that were photographed under controlled conditions. The detection rates may have sharply dropped when those systems were tested in a realistic scenario, which contains occlusion, illumination variation, scaling, and rotation. It is also shown that the learning algorithms perform better than the algorithms based on edge detection or template matching, but shallow learning models such as Adaboost algorithms also lack robustness in practice.

Table 1.

Summary of 2D ear detection approaches. EBPSO: Entropic binary particle swarm optimization; DTCWT: Dual tree complex wavelet transform.

2.2. Deep Learning in Computer Vision

Recently, the convolution neural network (CNN) has significantly pushed forward the development of image classification and object detection [34]. Krizhevsky [35] trained a deep CNN model named AlexNet to classify the 1.2 million images in the ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Competition 2010 (LSVRC-2010) contest into 1000 different classes. The neural network consists of five convolutional layers (some layers are followed by max-polling layers) and three fully-connected layers with a final 1000-way softmax layer. They employed a regularization method named ‘dropout’ to reduce over-fitting and accelerate convergence. They achieved top-1 and top-5 error rates of 37.5% and 17.0% on the test data. Simonyan [36] put forward a VGGNet deep model (Visual Geometry Group, Department of Engineering Science, University of Oxford.) to investigate the effect of the convolutional network depth on its accuracy of image classification. It showed that a significant improvement was achieved by pushing the depth to 16–19 weight layers. The top-1 and top-5 classification error rates of 23.7% and 6.8% were reported on ImageNet LSVRC-2014. In the same year, Szegedy et al. [37] proposed an innovative deep CNN architecture code named Inception. They designed a 22 layer deep network called GoogLeNet, the quality of which was assessed in the contest of ImageNet LSVRC-2014, and the top-5 classification error rate was 6.67%. Researchers found that the network depth was of crucial importance, and the leading results on the challenging of ImageNet dataset all exploited deep models. To solve the problem of degradation in the very deep network, He et al. [38] trained a 152 layer deep CNN called ResNet. Instead of learning unreferenced functions, they reformulated the layers as learning residual functions with reference to the layer inputs. These new networks were easier to optimize and achieved top-5 classification error rates of 3.57%.

Benefiting from the deep learning methods, the performance of object detection, as measured on the canonical Pattern Analysis, Statical Modeling and Computational Learning Visual Object Classes Challenge (PASCAL VOC), has made great progress in the last few years. Girshick et al. [39] proposed a new framework of object detection called Regions with CNN features(R-CNN). Firstly, around 2000 bottom-up region proposals were extracts from an input image. Then the features of each proposal were extracted based on a large convolutional neural network. Finally, the class-specific linear Support Vector Machines (SVMs) were used to classify each region. The R-CNN approach achieved a mean average precision (mAP) of 53.7% on PASCAL VOC 2010. However, because it performs a ConvNet for each object proposal, the time spent on computing region proposals and features (13s/image on a Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) or 53s/image on a CPU) cannot be ignored for an object detection system. Inspired by the Spatial pyramid pooling networks (SPPnets) [40], Girshick [34] proposed Fast R-CNN to speed up R-CNN by sharing computation. The network processed all the images with a CNN to produce a conv feature map. Then a fixed-length feature vector was extracted from the feature map for each object proposal. Each feature vector was fed into fully connected layers and output the bounding-box of each object. Fast R-CNN processed images were 213 times faster than R-CNN and achieved a 65.7% mAP on PASCAL VOC 2012. Although the improved network reduced the running time of the detection networks, the computation of exposing the region proposal was a bottleneck. Then the modified network called Faster R-CNN was proposed by Ren et al. [9]. In this work, they introduced a Region Proposal Network (RPN), which shared the full-image convolutional features with the detection network, enabling nearly cost-free region proposals. The RPN and Fast R-CNN were trained to share convolutional features with an alternating optimization. The detection system has a frame rate of 5fps on a GPU, while achieving 70.4% mAP on PASCAL VOC 2012.

In conclusion, schemes based on Faster R-CNN have obtained impressive performances on object detection in images captured from real world situations, but the extent of biometric application using Faster R-CNN algorithm has not been reported so far.

2.3. Contribution of This Paper

The specific contributions of this paper are as follows:

- A fully automatic novel 2D ear detection system is proposed. The experimental results and comparisons demonstrate the superiority of this system.

- A Multiple Scale Faster R-CNN framework is put forward to improve the performance of the original Faster R-CNN algorithm in the ear detection system. It is found that the ear detection system based on the traditional Faster R-CNN approach generated a lot of false positives in a real world application. Utilizing the information of ear location context, a novel ear region filtering approach is proposed to eliminate the false positives. It is shown that the performance of the proposed ear detection system has improved significantly.

3. Technical Approach

3.1. Database

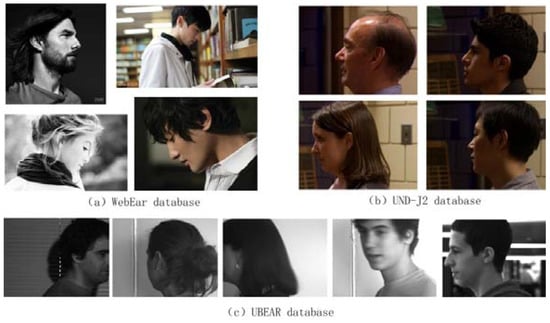

Data is very important for a deep learning system. However, the existing ear databases are limited and lack a uniform standard. Furthermore, the images in each database are almost all taken under similar and controlled conditions, so if the ear detection system is trained on a specific database, it may perform well on this database as the system may over-fit it. Thus these kind of approaches cannot been put to practice. In this work, we create a database named ‘WebEar’, which includes 1000 images collected from the Internet and captured from real world situations. The proposed ear detection system is trained on part of the WebEar database and tested on the WebEar database and other two databases. The overview of the content in each database is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

The content of each databases used in the paper: WebEar database, Collection J2 of University of Notre Dame Biometrics Database (UND-J2) and University of Beira Interior Ear dataset (UBEAR).

The proposed WebEar database consists of images in the wild taken from the Internet. Those images are photographed with different light conditions, different view angles, occlusions, complicated backgrounds, and a variety of image sizes and quality. The WebEar database is only used to train and test ear detection approaches, so we only labeled the bounding-box of the ear location in the image.

The UND-J2 [19] database includes 1800 images from 415 individuals, each with two or more sets of point cloud and the co-registered 2D 640 × 480 color images. There are 237 males and 178 females among them, 70 people who wore earrings at least once, and 40 people who have minor hair covering around the ear. The images were all photographed under different lighting conditions and angles and contain the subjects’ left ears. Although the images in this database were not taken under uncontrolled conditions, the UND database has been widely reported and utilized to test an ear detection approach, so the comparison of the proposed approach with other ear detection approaches will be taken on this database.

The UBEAR database [41] is a larger profile database that consists of two parts. The UBEAR v1.0 dataset is defined as the training set that contains 4497 images from 127 subjects taken from both the left and right side with ground truth masks. The UBEAR v1.1 dataset consists of 4624 images from 115 individuals, which is the testing set. The main distinguishing feature of the images in this database is that they were taken under varying lighting conditions while subjects were moving. In addition, no particular care was required regarding ear occlusions and poses. We would not tend to train and test our model on the same database and over-fit a specific kind of data to obtain a better result. Therefore, we combine the training and testing set, then test our algorithm and make a series of comparisons on all of the 9121 images. The examples of three databases are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The samples from three databases. (a) WebEar database; (b) UND-J2 database and (c) UBEAR database.

It’s worth noting that the proposed ear detection model has only been trained utilizing a part of the WebEar database (800 images of 1000) and then tested on three different databases without any extra fine-tuning or parameter-optimization. Compared with training and testing with the same database or similar images, we hold the view that that our testing scenariois more similar to the application situation.

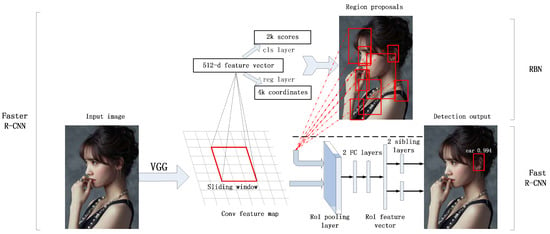

3.2. Faster R-CNN Frameworks

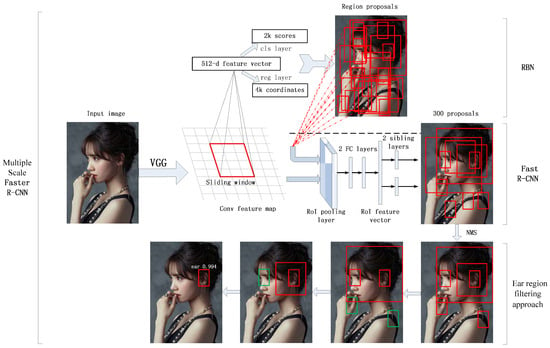

The networks used in this work is derived from the result of [9]. The traditional Faster R-CNN frame works are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The traditional faster regions with CNN features (R-CNN) frameworks.

Firstly, the ear proposals are obtained from the Region Proposal Network (RPN), which takes an image as input and outputs a series of rectangular object proposals, each with a score that measures the membership to a set of object classes. The VGG model [36], which has 13 shareable conv layers, is used in this work to generate the feature map, then the object detection network and the RPN share a common set of conv layers. A small window is slid over the conv feature map and mapped to a 512-d vector. Two sibling fully-connected layers, a box-regression layer (reg), and a box-classification layer (cls) are connected to the vector. 300 region proposals with three scales [] and three aspect radios [1:1, 1:2, 2:1] are predicted. With these definitions, a multi-task loss function is defended as [9]:

in which p is the predicted probability of a proposal being an ear and is the ground-truth label.

and are the predicted and ground-truth bounding-box, respectively. and denote probability prediction and bounding-box regression loss function, respectively. and are the normalization parameters and is a balancing weight. For regression, we adopt the parameterizations of the four coordinates following [35]:

where x, y, w, and denote the two coordinates of the box center, width and height. The variables and are for the predicted box, proposal box, and ground-truth box, respectively.

After the ear proposals are generated, we adapt the same architecture in [9]. Two sibling layers are followed with two fully connected layers, one of which outputs the soft-max probability of ears, and another layer outputs the corresponding bounding-box values. A multi-task loss L is used to jointly train for classification and bounding-box regression [34]:

where the probability prediction and bounding-box regression loss function are denoted as and . is the ground-truth label.

As described above, the convolutional layers between RPN and the detection network are shared to speed the detection work, and the whole training procedure is divided into four steps [9]. In the first step, the RPN is initialized with an ImageNet pre-trained model (VGG-16) [36] and fine-tuned for the region proposal task. In the second step, a separate detection network is trained by Fast R-CNN utilizing the proposals generated by the RPN. This network is also initialized by the VGG-16 model. In the third, the RPN is initialized with the detection network. The layers unique to RPN are fine-tuned, and the shared conv layers are fixed. Finally, keeping the shared conv layers fixed, we fine-tune the fc layers of the Fast R-CNN. Therefore, both networks share the same layers and form a unified network.

We train and test the ear detection network on the WebEar database. The network demonstrates an impressive capability for recognizing ear-shaped objects from an input image, so it may perform relatively well on cutout ear images and be robust to the pose variation, occlusion, and imaging conditions. However, it may make some mistakes when there is background noise in the image. In addition, the other regions of the human body such as hands, eyes, or the nose, which have similar texture or color as the ear in the image, may also be extracted inaccurately. For a real world ear detection task, this network may generate a lot of false positives. Additionally, the traditional Faster R-CNN makes the final detection decision via a threshold value method only utilizing the objectness scores of the ear bounding-box coordinates. Nevertheless, it is hard to choose an appropriate threshold value in practice. Some of the misdetection examples on the WebEar database are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Some misdetection examples on the WebEar database.

3.3. Multiple Scale Faster R-CNN

To address the problem mentioned above, an ear detection system based on Multiple ScaleFaster R-CNN is proposed in this paper. The traditional framework is improved to locate the ear more accurately and eliminate the false positives.

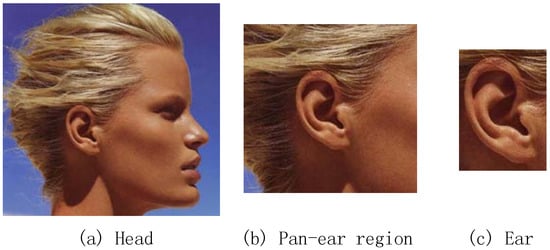

When people recognize objects, apart from recognizing the morphological characteristics of the objects, they also consider the background or the information of object location context to help make a decision. For example, if there is a human ear model on a desk, although it looks like a real human ear, people still don’t think of the ear model as a correct human ear because we know based on prior knowledge that the real human ear is part of human head and is located on the profile face. However, the networks recognize the ear only utilizing morphological characteristics so that the system sometimes fails to distinguish the ear from similar objects in the picture. Unlike natural object detection in which the background of the target object may be varied, the human ear is always located on the profile face. Therefore, we can improve the networks by training them with multiple scale images to locate the ear more accurately utilizing the information of ear location context.

We specifically train the networks to recognize three regions; head, pan-ear region, and ear. The head region means a cutout human profile region with barely any background or any part of the human body. The pan-ear region is defined as a part of profile that includes the ear and part of the face and hair but not the nose, eyes, or mouth. The ear region is a rectangular region as small as is probable, which includes the whole ear. The examples of the three regions are illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The examples of three regions. (a) Head, (b) Pan-ear region and (c) Ear.

The detection system defines the three regions as three different objects and trains respectively. The purpose of training with three partially overlapped regions is to eliminate ear-shaped background noise and indicating the ear context within the profile region. In the test stage, the same as in the traditional Faster R-CNN frameworks, 300 region proposals of each class, which are generated by RBN, are input to the Fast R-CNN. Two sibling layers output the soft-max probability of each class and another layer outputs the corresponding bounding-box values. However, unlike Faster R-CNN, we don’t output the bounding-box values with objectness scores above the threshold as the final result.

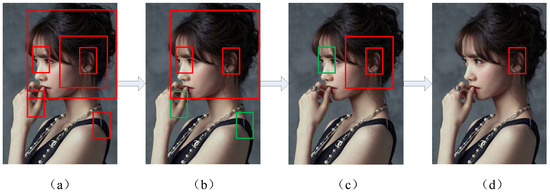

We proposed an ear region filtering approach to locate ear regions utilizing both the morphological characteristics and the location context of the ear. The schematic diagram of the approach is shown in Figure 5. (It is hard to show all the bounding-boxes in an image, so we only drew the representative bounding-boxes.) Firstly, the 300 bounding-boxes of each class are clustered into 10 bounding-boxes utilizing the non-maximum suppression algorithm (NMS). Each ear bounding-box is sorted by the objectness scores from high to low. Secondly, every ear bounding-box coordinate is compared with each head bounding-box coordinates to select those ear candidate regions that fully include at least one head region. In other words, the ear candidate regions that don’t fully fall into any one of ten head regions will be removed. As shown in Figure 5b, the two green box regions, which respectively belong to background and the other skin area, are eliminated from the ear candidate regions. Finally, all the remaining ear bounding-box coordinates are computed with each pan-ear region bounding-box coordinates to select those ear candidate regions that fully include at least one pan-ear region. As shown in Figure 5c,d, the false detection region of the eyes and nose is removed, leaving only the correct ear region. Additionally, if more than one ear candidate region in one pan-ear region is detected, only the region with the highest score is selected. In this way, an ear region has been detected from an image captured from a real world situation correctly. Additionally, the proposed ear region filtering method also can be applied to locate more than one ear from one image.

Figure 5.

The schematic diagram of the ear region filtering approach: (a), The 300 bounding-boxes of each class are clustered into 10 bounding-boxes utilizing the NMS algorithm; (b), The background regions are eliminated; (c) The other skin areas are eliminated; (d), The ear region is correct detected

A summary of the ear region filtering approach is listed as follows:

| Algorithm 1 Ear region filtering approach |

| 0: (Input) Given 30 bounding-box values belong to three classes: head, pan-ear region, and ear. Each class has 10 candidate bounding-boxes values, which are denoted as: , and . |

| 1: (Initialize) Each ear bounding-box value in is sorted by the objectness score from high to low. |

| 2: (Ear region location) delete from |

| for all do |

| for all do |

| if , Keep in |

| break |

| end if |

| Delete from |

| end for |

| for all do |

| if , Keep in |

| break |

| end if |

| Delete from |

| end for |

| end for |

| where . |

| 3: (Output) Output the ear bounding-box values in . |

The Multiple Scale Faster R-CNN framework is illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The Multiple Scale Faster R-CNN framework.

The deep learning model has shown impressive ability to recognize ear-shaped objects. However, it will be prone to make large mistakes from images with complicated backgrounds at the same time. It is hard to find a satisfactory balance between false detection and missing detection only by a threshold value method. Inspired by the cognitive behaviors of humans, we improve the traditional Faster R-CNN framework to extract ear regions by combining both the morphological characteristics and the location context of the ear. Furthermore, the proposed research thought can be generalized to similar kind of detection task such as face detection, license plate detection, medical image analysis, etc.

4. Experiments

In this work, three databases, which are mentioned above, are utilized to evaluate the proposed approach. In order to avoid over-fitting, the detection networks are trained only utilizing 800 images from the WebEar database and then tested on another 200 images from the WebEar database, UND-J2 database, and UBEAR dataset. As we know, the three databases are quite different, so the generalization ability of the proposed approach will be tested and proved. To contrast the results, the AdaBoost approach in [33] and the traditional Faster R-CNN approach are also tested on the same databases.

4.1. Ear Detection Results

Most existing ear detection approaches were evaluated only by an ear correct detection rate. However, the reliability and the precision of a detection model must be both considered in a practical application, so we evaluate the proposed ear detection approach by several indexes, which are listed and defined in Table 3.

Table 3.

The evaluation indexes used in this paper.

In Table 3, TP is True Positive, FP means False Positive, FN is False Negative and TN represents True Negative. The precision describes the exactness of the model; the recall measures the completeness; and the F1 score provides an overall evaluation of the system. Moreover, the traditional accuracy is also provided for comparisons with other approaches.

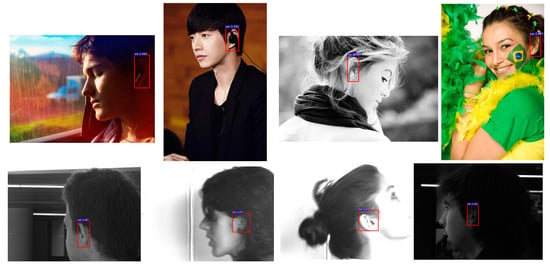

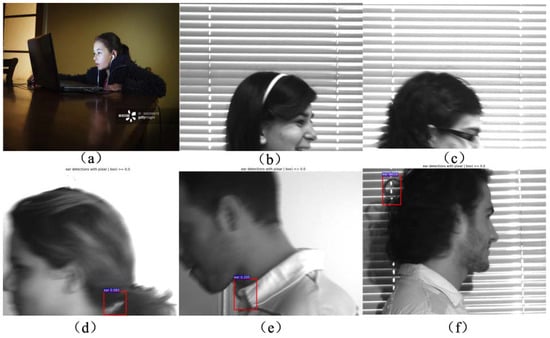

The ear detection algorithm costs about 0.22 s per image on a GPU of GTX Titan X (Gigabyte Technology, Beijing, China). The training time of the deep model is 182 min. The results of the proposed approach on three databases are displayed in Table 4. Figure 7 illustrates some detection results on particularly challenging images, which are selected from the WebEar and UBEAR databases. It is demonstrated that the proposed system has correctly detected all the ears in the UND-J2 database. As to ear detection with uncontrolled conditions and complicated backgrounds, the proposed ear detection method obtains an impressive performance on the WebEar database. Only three false positives and one false negative are generated out of 200 images. Performance on the UBEAR database is also proposed. Different from the WebEar database, the images in the UBEAR database were acquired from on-the-move subjects with various photographic qualities such as over illumination or out of focus. Even though the detection accuracy rate of the proposed system on this database is 97.61%, some of the false negatives (the top row) and false positives (the bottom row) on the WebEar and UBEAR databases are presented in Figure 8.It is shown that the proposed algorithm fails to detect ears from some low-resolution images (Figure 8a) or blurred images (Figure 8c–f). Additionally, some ears with major occlusion (more than 70% occlusion) are not detected successfully either (Figure 8b). Actually, we also find that most of those ear images cannot be utilized for an ear recognition system.

Table 4.

The results of proposed approach on three databases.

Figure 7.

Some detection results on particularly challenging images in the WebEar and UBEAR databases.

Figure 8.

Some of the false negatives (the top row) and false positives (the bottom row) on the WebEar and UBEAR databases: (a), low-resolution image; (b), ear image with major occlusion; (c–f), blurred images.

4.2. Robustness under Uncontrolled Condition

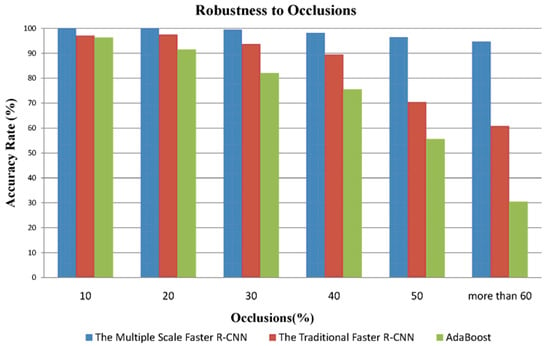

Challenging images in WebEar and UBEAR databases are selected and divided into several subsets according to the different levels of occlusions, pose variations, and other uncontrolled conditions. To evaluate the robustness of our ear detection approach under uncontrolled conditions, we test the proposed system on those subsets. The comparisons of the proposed approach with the AdaBoost [33] and traditional Faster R-CNN algorithm are also presented.

4.2.1. Robustness to Occlusions

We selected images with hair occlusions from WebEar and UBEAR databases and divided them into six groups depending on the different levels of occlusions. The results are shown in Figure 9. It can be found that the performances of the AdaBoost and the traditional Faster R-CNN algorithms have a remarkable decline when there are strong hair occlusions in the images. By contrast, the proposed approach has achieved an accuracy rate of 94.7% on the subset with more than 60% occlusions.

Figure 9.

The comparison of the proposed approach with similar approaches on the occlusions subset.

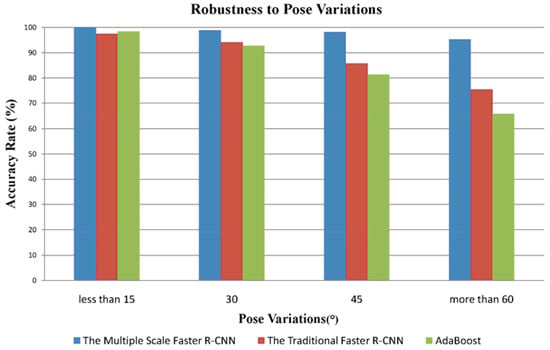

4.2.2. Robustness to Pose Variations

Large pose variations of the ear, especially in cases where there is an out-of-plane rotation, may introduce self-occlusions and a change of the ear shape. The images with pose variations in the two databases are divided into four groups according to the different poses. We test our method on the pose variation subset and illustrate the comparison of results in Figure 10. The proposed approach outperforms the other two approaches under the scenario of pose variation. 95.3% of ears are detected successfully, even in the images with pose variation of more than 60 degrees.

Figure 10.

The comparison of the proposed approach with similar approaches on the pose variations subset.

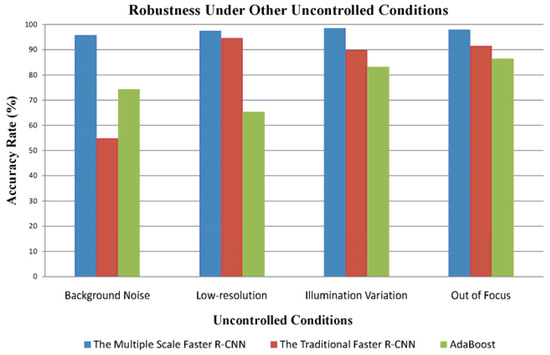

4.2.3. Robustness under Other Uncontrolled Conditions

The profile images photographed under uncontrolled conditions may be influenced by many factors except occlusions and pose variations, including background noise, low-resolution, illumination variation, and being out of focus. These cases are widespread in practical application scenarios. Therefore, we analyse the images in the WebEar and UBEAR databases according to the mentioned four situations. Then we generate four subsets and test the proposed approach on them respectively. As shown in Figure 11, the proposed approach is more robust to the aforementioned influences on the images.

Figure 11.

The comparison of the proposed approach with similar approaches under other uncontrolled conditions.

4.3. Comparison and Discussion

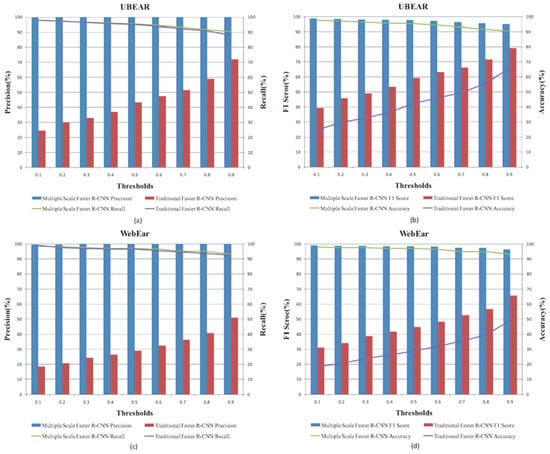

In this section, the thresholds of the objectness score are evaluated, and then the comparisons of different algorithms on the three databases are reported. Finally, the performance of this ear recognition system is analyzed with respect to other ear detection systems on the UND-J2 database.

In a traditional detection system [9,34,39], the threshold is necessary and usually dependent on the type of data being tested. Users have to change the threshold manually while the type of data changes. Thus, the practicability of those systems will be greatly limited. As mentioned above, we don’t output the bounding-box values with objectness scores above threshold as the final result. The ear region filtering approach is therefore proposed to select the ear bounding-box from 10 ear bounding-box coordinates, utilizing the information of ear location context. Therefore, unlike other detection systems [9,34,39], we needn’t use the threshold of the objectness score in the proposed ear detection system.

The threshold of the objectness score (which we set to 0) is a default parameter in a Faster R-CNN based detection system. Figure 12 shows the performance comparisons of the Multiple Scale Faster R-CNN and the traditional Faster R-CNN algorithm with varying threshold values on the UBEAR and WebEar databases. It shows that the variations of the threshold value significantly affect the performance of traditional Faster R-CNN. By contrast, the precision, recall, F1 score and accuracy of Multiple Scale Faster R-CNN on both databases all stay above 90%, no matter how the threshold value changes. Moreover, the performance of the proposed detection system suffers a slight decline while the threshold is raised because those ear regions with low objectness scores are mistakenly eliminated. The experiment results demonstrate that the proposed ear region filtering approach is more robust than the threshold method for the ear detection task in real scenarios.

Figure 12.

The performance comparisons of the Multiple Scale Faster R-CNN and the traditional Faster R-CNN algorithm with varying threshold values on the UBEAR and WebEar databases: (a), the comparisons of the precision and recall on UBEAR database; (b), the comparisons of the F1 score and accuracy on UBEAR database; (c), the comparisons of the precision and recall on WebEar database; (d), the comparisons of the F1 score and accuracy on WebEar database.

The comparisons of the proposed approach with AdaBoost [33] and traditional Faster R-CNN [9] are presented in Table 5. It is experimentally proved that the Multiple Scale Faster R-CNN outperforms the other two algorithms on three databases significantly. Notice that the AdaBoost algorithm obtained relatively low false positives but a high false negatives on every database. By contrast, the false positive rate of traditional Faster R-CNN algorithm is much higher than its false negative rate. The results indicate that, on the one hand, the deep neural network (Faster R-CNN) obtains a much higher ability to recognize objects than the shallow neural network (AdaBoost) does; on the other hand, the traditional Faster R-CNN may fail to distinguish the correct human ear from ear shape objects without the information of ear location context. For example, the images in the UND-J2 database were photographed under controlled conditions with a single background. All of the ears in the database are extracted by the traditional Faster R-CNN approach. However, it is found that mass of eyes or nose regions are identified as ear regions due to their similar textures or shape. Therefore, the AdaBoost approach obtains a higher accuracy rate than the traditional Faster R-CNN approach does on the UND-J2 database, although 173 ears failed to be detected. We have solved those problems by training a Faster R-CNN model and connecting it to an ear region filtering approach. Most of the ears in the three databases are extracted, and almost all of the false positives are eliminated successfully.

Table 5.

The comparisons of the proposed approach with AdaBoost and traditional Faster R-CNN approach on the three databases.

Detecting ears from 2D profile images captured in uncontrolled conditions is of great significance in practical application. However, most existing ear detection approaches have not been tested in non-cooperative environments. A possible reason is the absence of widely used appropriate ear databases. The UBEAR database is an up-to-date database, and no exciting ear detection approach has been tested on it. Therefore, the comparison of the proposed approach with other representative approaches is taken on the UND-J2 database, which has been wildly used to test ear detection approaches. The UND-J2 database includes1800 images from 415 individuals with slight occlusion and illumination variation. Unlike the WebEar and UBEAR databases, the UND-J2 database was created under controlled conditions. Therefore, detecting ears on this database is not really challenging work for the proposed method. The comparison is given in Table 6.

Table 6.

The comparison of the proposed approach with other representative approaches on the UND-J2 database.

Notice that the modified AdaBoost approach proposed by Islam et al. [2] also obtained a 99.9% accuracy rate with part of the UND-J2 database. However, the training data of the classifiers in [2] included a part of the UND-F database, which is very similar to the UND-J2 database. Therefore, the conclusion is that the proposed ear detection method outperforms other methods in the table.

5. Conclusions

An efficient and fully automatic 2D ear detection system utilizing Multiple Scale Faster R-CNN is proposed in this paper to detect ears under uncontrolled conditions. We improve the traditional Faster R-CNN framework by combining both the morphological characteristics and the location context of the ear. A Faster R-CNN model with three different scale regions is trained to infer the information of ear location context within the image. Finally, the threshold value part of the traditional Faster R-CNN approach is abandoned, and a proposed ear region filtering approach is utilized to make a decision. The proposed ear detection approach obtains a much better performance than the AdaBoost and traditional Faster R-CNN algorithms do on the three databases respectively. The experimental result on the UND-J2 database demonstrates that the proposed ear detection system outperforms state-of-the-art 2D ear detection systems. Furthermore, we insist that our works in this paper can provide a novel thought for solving a specific kind of detection problem.

Acknowledgments

This article is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 11250106). The authors would like to thank the computer vision research laboratory at University of Notre Dame and the Soft Computing and Image Analysis Group (SOCIA), Department of Computer Science, University of Beira Interior for providing their biometrics databases.

Author Contributions

Yi Zhang conceived and designed the experiments. Yi Zhang performed the experiments. Zhichun Mu analyzed the data. Yi Zhang wrote the paper. Zhichun Mu and Yi Zhang reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jain, A.K.; Patrick, F.; Arun, A.R. Handbook of Biometrics; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2007; pp. 131–150. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, S.M.S.; Davies, R.; Bennamoun, M.; Mian, A.S. Efficient detection and recognition of 3D ears. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2011, 95, 52–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.; Bowyer, K.W.; Chang, K.J. ICP-based approaches for 3D ear recognition. In Proceedings of the 2005 SPIE-The International Society for Optical Engineering, Orlando, FL, USA, 28 March 2005; pp. 282–291. [Google Scholar]

- Prakash, S.; Gupta, P. A rotation and scale invariant technique for ear detection in 3D. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2012, 33, 1924–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Delving deep into rectifiers: Surpassing human-level performance on imagenet classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Carmen, Saliba, 7–13 December 2015; Volume 1, p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Sladojevic, S.; Arsenovic, M.; Anderla, A.; Culibrk, D.; Stefanovic, D. Deep neural networks based recognition of plant diseases by leaf image classification. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taigman, Y.; Yang, M.; Ranzato, M.; Wolf, L. Deepface: Closing the gap to human-level performance in face verification. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 1701–1708. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, C.; Ennio, M. Mitigation of effects of occlusion on object recognition with deep neural networks through low-level image completion. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Montréal, QC, Canada, 7–12 December 2015; pp. 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Burge, M.; Burger, W. Ear biometrics in computer vision. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Pattern Recognition, Barcelona, Spain, 3–7 September 2000; Volume 2, pp. 822–826. [Google Scholar]

- Hurley, D.J.; Nixon, M.S.; Carter, J.N. Force field energy functionals for image feature extraction. Image Vis. Comput. 2002, 20, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, L.; Gonzalez, E.; Mazorra, L. Fitting ear contour using an ovoid model. In Proceedings of the 2005 International Carnahan Conference on Security Technology, Las Palmas, Spain, 11–14 October 2005; pp. 145–148. [Google Scholar]

- Ansari, S.; Gupta, P. Localization of ear using outer helix curve of the ear. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computing: Theory and Applications, Kolkata, India, 5–7 March 2007; pp. 688–692. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, L.; Mu, Z.C. Ear detection based on skin-color and contour information. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning and Cybernetics, Qingdao, China, 11–14 July 2010; pp. 2213–2217. [Google Scholar]

- Arbab-Zavar, B.; Nixon, M.S. On shape-mediated enrolment in ear biometrics. In Advances in Visual Computing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 549–558. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings, A.H.; Nixon, M.S.; Carter, J.N. A novel ray analogy for enrolment of ear biometrics. In Proceedings of the 2010 Fourth IEEE International Conference on Biometrics: Theory Applications and Systems (BTAS), Washington, DC, USA, 27–29 September 2010; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Prakash, S.; Gupta, P. An efficient ear localization technique. Image Vis. Comput. 2012, 30, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.; Bowyer, K. Empirical evaluation of advanced ear biometrics. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, San Diego, CA, USA, 20–25 June 2005; p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, P.; Bowyer, K.W. Biometric recognition using 3D ear shape. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2010, 29, 1297–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deepak, R.; Nayak, A.V.; Manikantan, K. Ear detection using active contour model. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Emerging Trends in Engineering, Technology and Science, Pudukkottai, India, 24–26 February 2016; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Bhanu, B. Contour matching for 3D ear recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Workshop on Applications of Computer Vision and Motion and Video Computing, Breckenridge, CO, USA, 5–7 January 2005; pp. 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Bhanu, B. Shape model-based 3D ear detection from side face range images. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition-Workshops, San Diego, CA, USA, 21–23 September 2005; p. 122. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Bhanu, B. Human ear recognition in 3D. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2007, 29, 718–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganesh, M.R.; Krishna, R.; Manikantan, K.; Ramachandran, S. Entropy based binary particle swarm optimization and classification for ear detection. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2014, 27, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sana, A.; Gupta, P.; Purkai, R. Ear biometrics: A new approach. In Advances in Pattern Recognition; Pal, P., Ed.; World Scientific Publishing: Singapore, 2007; pp. 46–50. [Google Scholar]

- Prakash, S.; Jayaraman, U.; Gupta, P. A skin-color and template based technique for automatic ear detection. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advances in Pattern Recognition (ICAPR 2009), Kolkata, India, 4–6 February 2009; pp. 213–216. [Google Scholar]

- Attarchi, S.; Faez, K.; Rafiei, A. A new segmentation approach for ear recognition. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2008, 5259, 1030–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Halawani, A.; Li, H. Human ear localization: A template-based approach. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Pattern Recognition (ICOPR 2015), Dubai, UAE, 4–5 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, K.V. Oval shape detection and support vector machine based approach for human ear detection from 2D profile face image. Int. J. Hybrid Inf. Technol. 2014, 7, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.M.S.; Bennamoun, M.; Davies, R. Fast and fully automatic ear detection using cascaded AdaBoost. In Proceedings of the IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Copper Mountain, CO, USA, 7–9 January 2008; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Abaza, A.; Hebert, C.; Harrison, M.A.F. Fast learning ear detection for real-time surveillance. In Proceedings of the Fourth IEEE International Conference on Biometrics: Theory Applications and Systems, Washington, DC, USA, 27–29 September 2010; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Shih, H.C.; Ho, C.C.; Chang, H.T.; Wu, C.S. Ear detection based on arc-masking extraction and AdaBoost polling verification. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Information Hiding and Multimedia Signal Processing (IIH-MSP 2009), Kyoto, Japan, 12–14 September 2009; pp. 669–672. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, L.; Mu, Z. Ear recognition based on Gabor features and KFDA. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Girshick, R. Fast R-CNN. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Lake Tahoe, CA, USA, 3–8 December 2012; pp. 1097–1105. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv, 2014; arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Reed, S.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Vanhoucke, V.; Rabinovich, A. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 8–10 June 2015; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. arXiv, 2015; arXiv:1512.03385. [Google Scholar]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Spatial pyramid pooling in deep convolutional networks for visual recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2014, 37, 1904–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raposo, R.; Hoyle, E.; Peixinho, A.; Proença, H. UBEAR: A dataset of ear images captured on-the-move in uncontrolled conditions. In Proceedings of the Computational Intelligence in Biometrics and Identity Management, Paris, France, 11–15 April 2011; pp. 84–90. [Google Scholar]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).