Abstract

Mirror symmetry is an important and common feature of the visual world, which has attracted the interest of scientists, artists, and philosophers for centuries. The human visual system is very sensitive to mirror symmetry; symmetry is detected quickly and accurately and influences perception even when not relevant to the task at hand. Neuroimaging studies have identified mirror symmetry-specific haemodynamic and electrophysiological responses in extra-striate regions of the visual cortex, and these findings closely align with behavioural psychophysical findings when only considering the magnitude and sensitivity of the response. However, as we go on to discuss later, the location of these responses is at odds with where psychophysical models based on early visual filters would predict. In attempts to capture and explain mirror symmetry perception, various models have been developed and refined as our understanding of the factors influencing mirror symmetry perception has grown. The current review provides a contemporary overview of the psychophysical and neuroimaging understanding of mirror symmetry perception in human vision. We then consider how new findings align with predominant spatial filtering models of mirror symmetry perception to identify key factors that need to be accounted for in current and future iterations.

1. Introduction

The existence of symmetries has long fascinated scientists, artists and philosophers. We see an appreciation for natural and artificial visual symmetries across species, including bees [1,2,3], pigeons [4] and chickens [5]. We can also observe different forms of symmetry across all physical and philosophical domains, including in animals and plants [6], in chemistry [7], in physics and mathematics [8,9], and in language, literature and music [10,11,12,13,14] (See Figure 1).

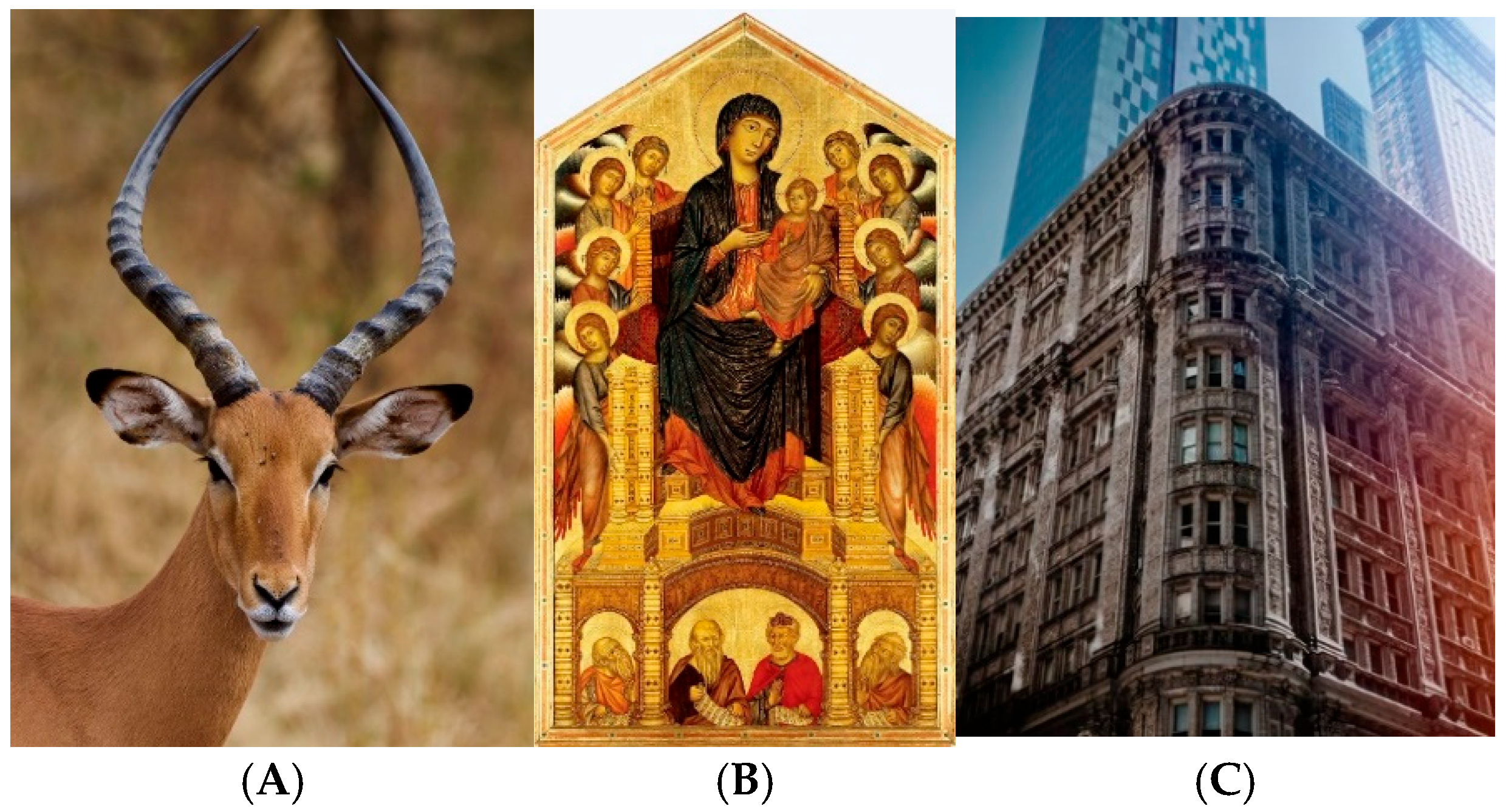

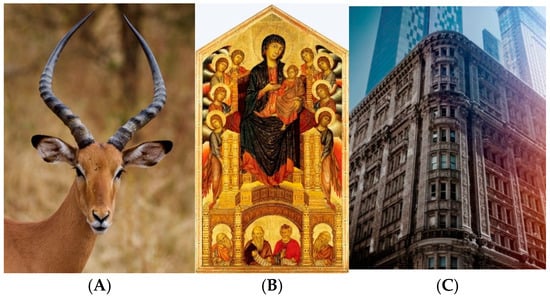

Figure 1.

Examples of natural and artificial mirror symmetries in the visual world include (A) animals, (B) art such as the classic works by Cimabue [13], and (C) architecture. From Cimabue [13] and online database Unsplash [14] https://unsplash.com/, (accessed on 15 August 2022).

In humans, symmetry is recognised visually and preferentially viewed as early as 4 months of age [15] and is omnipresent across cultures [16], including in artworks across time and place [12]. Some researchers have also argued that the preference for symmetry in humans, as it is in animals, occurs because symmetry is a marker of healthy development and, therefore, mate attractiveness [17,18,19,20]. Others have suggested that symmetry may also play an important role in scene perception, particularly when identifying objects in a visual scene [21] and in figure/ground segmentation [22,23]. More recently, the importance of symmetry as an attractive and useful feature from a human factors perspective has been noted in terms of design, marketing, architecture and artificial vision [24,25,26]. These examples serve to highlight how symmetry can provide a means of structure and organisation across a range of seemingly unrelated disciplines and thus is an important organising principle of our world more generally [12].

1.1. Focus and Structure of the Current Review

The aim of this review is to provide an overview of historical and contemporary research findings on the processing of visual mirror symmetry in human observers. This is intended to build on and extend previous reviews, the most recent of which was conducted by Treder [27]. We begin by outlining the rationale behind focusing on visual mirror symmetry, specifically by exploring its special status in visual perception and how this differs from other types of symmetries. We review psychophysical studies of mirror symmetry in terms of both global forms at the pattern level and local features at the element level. As part of this overview, we explore a set of recent studies exploring the temporal features of symmetry processing, including the temporal integration of symmetry information. We then turn our attention to the neuroimaging literature, including haemodynamic and electrophysiology signals specific to and modulated by symmetry. Finally, we examine the current prevailing models of visual symmetry processing—the so-called spatial filter models. We examine in detail three influential models by Dakin and Watt [28], Dakin and Hess [29], and Rainville and Kingdom [30] and consider the strengths of these models, particularly their biological plausibility and alignment with established features of processing in early stages of the visual system (e.g., spatial filters). However, although initially successful, there are many recently established findings in symmetry perception that spatial filter models cannot account for in their current form. This includes the beneficial effect of higher-order structure and the visual system’s ability to identify symmetry in the context of spatial and temporal manipulations (e.g., temporal integration, opposite contrast polarity feature pairs, and local orientation variations). Furthermore, these models predict symmetry perception should arise as early as the primary visual cortex (V1), which is not consistent with neuroimaging studies suggesting that symmetry information activates V4 and other extra-straite regions. With this in mind, this review highlights the need for updated, revised models of symmetry processing mechanisms with the breadth and flexibility to account for contemporary psychophysical and neuroimaging findings. For conciseness, “symmetry” in this review will refer specifically to mirror symmetry.

1.2. Special Status of Mirror Symmetry

While precise definitions of symmetry vary across disciplines, applications and philosophical viewpoints, when an object, living entity, pattern or concept is described as symmetric, its key features are repeated in some way. This review focuses on visual symmetry and, more specifically, mirror symmetry (also referred to as bilateral or reflection symmetry). In vision, an object or pattern is considered to be mirror-symmetric when it can be divided into two identical but reflected (i.e., mirrored) halves along at least one central axis [27]. For example, the butterfly in Figure 2A has two wings on either side of the body, which act as the axis of reflection. Further, the wings’ shape and patterns are identical but opposite; they form mirror images of each other, about a diagonal midline (in this example image). In other words, the image properties at a distance orthogonal to the symmetry axis are identical to properties at − also orthogonal to the axis;

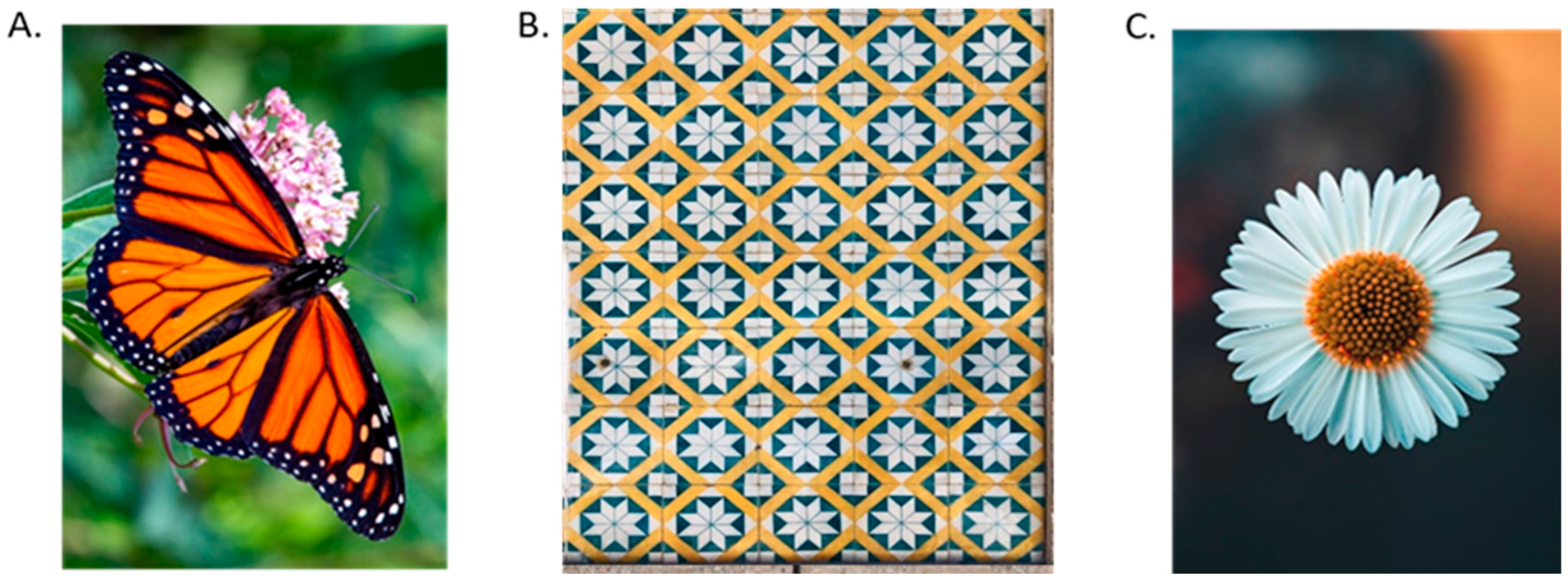

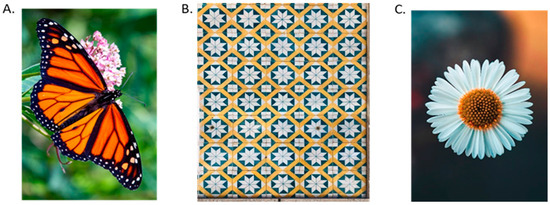

Figure 2.

Real-world examples of the different types of symmetries include (A) reflection or mirror symmetry, (B) translation or repetition symmetry, and (C) rotational symmetry. Available on https://unsplash.com/ [14] accessed on 15 August 2021.

In perfect symmetry, all components of the image would satisfy Equation (1). However, it is important to note that this is not necessary for symmetry to be detected, and most of the studies reviewed in this article focus on minimum detection thresholds (e.g., how much symmetry information is required to be reliability detected or discriminated). When an image partially satisfies Equation (1), symmetry is still detectable, for example. If we were to apply Equation (1) to Figure 1B above, the symmetry response would be imperfect as the symmetry information in the image is imperfect; however, a symmetry signal would still be carried by those image elements that do match. As long as this signal is present, other kinds of information [31] should not affect the minimal detection thresholds.

One of the earliest and most consistent findings in symmetry research is the special status of mirror symmetries over repetition and rotation [25]. The human observer’s sensitivity to vertical mirror symmetry was noted in writings by Mach [32] in the late 19th century. Mach observed reflection was more readily perceived than other symmetry types and also that there appeared to be a difference in sensitivity depending on the orientation of the axis of symmetry, commenting that -

“vertical [mirror] symmetry pleases us, whilst horizontal symmetry is indifferent and is only noticed by the experienced eye”(p. 33).

Mach [32] also goes on to postulate that symmetry perception is innate or inbuilt in the visual system, and given its prevalence across the visual environment,

“the sense of symmetry, although primarily acquired by means of the eyes, cannot be wholly limited to the visual organs. It must also be deeply rooted in the other parts of the organism by ages of practice…”(p. 35).

Mach’s [32] writing has inspired a rich and detailed history of research interest into how, when, where and why mirror symmetry is processed in the visual system.

1.3. Other Types of Symmetry

Other symmetries include repetition symmetry (Figure 2B), where identical sub-components are repeated across space at regular intervals, such as in the tiled friezes in Figure 2B and for these, Equation (1) would need to recognize multiple symmetry axes to apply adequately. A third type of symmetry is rotational symmetry, where an object can be rotated around a central point without change in its appearance, which can be seen in flowers (Figure 2C) and Equation (1) is not an appropriate description. While multiple symmetries can be present in a given object, one will be the most useful and, therefore, predominant in processing (for example, most rotational symmetries can have multiple reflectional symmetry axes, and reflection symmetries with more than one axis have a degree of rotational symmetry). While observers could accurately identify repetition symmetries, the process was found to be substantially more laborious and time-intensive. Corballis and Roldan [33] showed a detection advantage for mirror symmetry over repetition, and Bruce and Morgan [34] similarly found that observers were better able to detect asymmetries in mirror symmetry than with repetition, a fact later confirmed by Jenkins [35]. Figures with reflected contours, and therefore mirror symmetry, are also more readily perceived than those with repeated contours [36,37]. Similar outcomes are found when rotational symmetries are compared to mirror symmetry. Regardless of the degree of rotation (e.g., 90° versus 180°) or the type of pattern (e.g., dots, line segments or solid polygons), a substantial performance benefit was obtained for mirror symmetry [38,39]. In contrast, little difference is found when directly comparing repetition and rotational symmetries [40,41,42]. For the remainder of the review, we will focus on mirror symmetry, which is the symmetry signal the human visual system is most sensitive to.

2. Mirror Symmetry in Psychophysics: Local Detail and Global Form

Mirror symmetry is one of the predominant structural features in biological organisms and is used to guide our interpretation of the visual world [43]. Symmetry was included in the original Gestalt perceptual organisation principles discussed by Wertheimer [44] and later Koffka [23], alongside proximity, similarity, common fate, parallelism, good continuation and closure [45]. It has been argued that symmetry is a useful grouping cue because it simplifies complex visual input [43,46]. Barlow and Reeves [47] and Apthorp and Bell [48] all noted that the detection of a small amount of symmetry in an image can convey more information about the overall pattern than any irregular feature and thus is a very useful and economical cue for reducing the amount of information processing required in a scene [43]. Symmetrical image components are unlikely to occur by chance, and therefore, symmetry adds redundancy that is likely to reinforce the image interpretation. Moreover, if the observer is looking for a known target, then regions of symmetry may be sufficient for recognition. Consistent with this view, small amounts of symmetry information can lead to generally random patterns being erroneously interpreted as more substantially symmetric, and the location of symmetric regions within a larger object can also influence the overall perception. The tendency to overgeneralise a symmetric interpretation can be leveraged for camouflage [49]. Symmetry is, therefore, dependent on the interplay of local (element level) and global (pattern level) information. This section presents an overview of the key spatial features implicated in symmetry processing and how the overall perception of symmetry is changed when these features are manipulated. We discuss these findings, beginning with global pattern features and progressing to more local information at the element and element pair level.

2.1. Axis Orientation

Mirror symmetry is defined by the presence of an explicit or implied axis around which reflected elements are arranged [50]. Eye tracking studies, where axis location and orientation were consistent, have shown that observers tend to initially fixate on the centre of the pattern or object, where the object symmetry axis is located, and use this location as the initial basis for decisions of whether a pattern is symmetrical or not [51,52]. If the axis location is less predictable, symmetry salience is reduced, although this effect is attenuated when the location of the axis is cued prior to viewing the pattern [53,54].

All else being equal, symmetric patterns with a vertical axis are the most readily perceived, both in terms of detection speed and the magnitude of signal required to discriminate symmetry from noise [39,55,56,57]. Studies report an anisotropic relationship between axis orientation and symmetry detection; patterns with vertical axes are most quickly and accurately detected, followed by patterns with horizontal axes and then cardinal obliques [27,33]. Wenderoth [58] argued that symmetry axes were treated in a similar manner to contours, where a vertical advantage and reduced contrast sensitivity to oblique contours are found (oblique effect; Orban, Vandenbussche & Vogels, [59]), consistent with the suggestion that orientation and symmetry perception share some common orientation-tuned mechanisms [60].

While there is not a clearly established reason for mirror symmetry patterns with vertical axes being detected more readily than other orientations, many potential explanations have been suggested. The earliest of these was the idea that vertical symmetry was most salient because it aligned with the hemispheric representation of the visual field in the brain, leading to the mental rotation hypothesis [32,33,56,61]. Corballis and Roldan [33] suggested the advantage of vertical symmetry stemmed from its alignment with the vertical meridian dividing the visual half fields between the two hemispheres of the brain (e.g., two mirror symmetric hemispheres with a corpus callosum running through the central axis), consistent with earlier speculations by Mach [32]. The idea of the involvement of the corpus callosum arose from the observation that callosal projecting neurones processing symmetrically placed locations across the vertical meridian were common along the border of V1/V2 cortical maps [62,63]. The callosal hypothesis proposed the detection cost (measured in terms of response times) when processing non-vertical axis patterns arose because they needed to be mentally rotated to determine if a symmetry axis was present. As all patterns were treated as though they had a vertical axis, the process took longer with larger rotation angles. Julesz [64] suggested that symmetry perception was achieved via a point-by-point matching process, whereby each hemisphere processed one side of the axis. The corpus callosum facilitated this matching by connecting symmetrically positioned locations [65,66]. While the specifics of the callosal hypothesis have not been supported, it is argued in the more contemporary literature that a symmetry-sensitive visual system is evolutionary and adaptive [67]. From this perspective, humans may have developed sensitivity to the prevalence of natural and artificial vertical symmetries. Studies of face processing and sexual attraction find symmetric faces, which have a vertical symmetry axis, correlate strongly with positive judgements of attractiveness [68] and perceptions of beauty [69]. A near-vertical symmetric axis is also common in head-on views of the animal kingdom.

2.2. Number of Symmetry Axes

While symmetry is defined by the presence of an axis, symmetric patterns are not restricted to a single axis; multiple symmetry axes of different orientations may be present in a single object [33]. Many studies of symmetry perception have shown a near-monotonic increase in response accuracy and a decrease in response time as the number of symmetry axes increases. Observers tend to be faster and more accurate at identifying the presence of symmetric patterns with four axes than with a single vertical symmetry axis alone, despite the established vertical advantage for single symmetries [70,71,72]. It has been suggested that additional symmetry axes increase the amount of symmetry information within a single pattern. Patterns with multiple axes are also more resistant to disruption from positional skewing or non-orthogonal viewpoints [50,70,73], potentially due to the additional information in the rotational structure, which has been previously identified as rapidly detectable [74,75,76,77,78]. In summary, patterns with vertical symmetry axes are consistently more readily detectable than other orientations. However, increasing the number of symmetry axes improves symmetry processing in an additive fashion, regardless of the specifics of the task.

2.3. Element Position

Symmetry is defined by element position—an individual dot or pair of dots is generally meaningless in isolation within a random field of dots. However, when a number of such pairs are grouped around a central point, it can create an impression of a global structure. Different arrangements of such pairs produce different structures, including Glass patterns [78] and, of course, mirror symmetry [73,79]. For mirror symmetry, paired dots cluster along the axis such that both are equidistant from and orthogonal to the axis [79], as in Equation (1). If a dot does not have a symmetrically positioned partner across the axis, it will not contribute to the symmetry signal in a pattern and is instead a “noise” element that disrupts the underlying symmetric structure. Having too high a proportion of these noise dots can obscure spatial structure conveyed by the symmetric pairs. Varying the ratio of signal (symmetrically positioned) to noise (non-symmetrically positioned dots) is a common way of investigating symmetry perception, as it allows for the calculation and comparison of symmetry detection thresholds without changing the overall number of dots in the pattern. Patterns to which observers are less sensitive require higher signal-to-noise ratios to be detected, both in terms of identifying symmetric patterns and differentiating symmetric patterns from noise patterns.

2.3.1. Integration Region and Pattern Outline

While symmetry is generally considered a global pattern feature, the region immediately around the axis is the most salient cue to the presence of symmetry [80,81]. The size of this critical region varies depending on the information density along the pattern axis [29,30]. Patterns with greater local information clustered along the axis tend to be more readily detected compared to patterns where random noise is introduced over this region (see the section on element orientation; Rainville and Kingdom [30]). Furthermore, disrupting or obscuring the symmetry axis by embedding strips of random noise in the location of the axis has been shown to reduce the salience of symmetry in remaining regions, even when all other cues are retained [53].

Second, regarding the symmetry axis, Wenderoth [58] found that the pattern outline or boundary is another important cue for mirroring symmetry. He found that symmetric regions needed to have higher proportions of symmetrical signals to be detected when embedded in a random noise surround, even though the symmetry axis was retained and all other cues to symmetry were present. Symmetry thus appears to be processed holistically; when the symmetry axis is readily identified, and the outline of a pattern is symmetric, it is assumed that the pattern is globally symmetric even if other subregions (e.g., between the axis and boundary) are imperfectly symmetric [43]. Thus, we are most sensitive to disruptions along the central axis or outer boundary of the pattern while being relatively less sensitive to the information contained throughout the rest of the pattern [58] when the target pattern is an unknown field of dots.

2.3.2. Skewed Symmetry

In a real-world setting, symmetric objects or patterns are often viewed from non-frontoparallel viewpoints (i.e., “side on”) where there is displacement of the relative positions of elements across the axis, known as “skew”. Symmetry detection mechanisms are very sensitive to disruptions in element position. If element positions within a given pair are jittered, such that the virtual lines joining the paired elements are no longer orthogonal to the axis, symmetry becomes significantly more difficult to detect [40]. While symmetry detection is still possible under such conditions, it presents an important challenge to the visual system since I(axis+D) is no longer equal to I(axis-D) [62]. In skewed symmetry patterns [34], the position of elements differ in distance from the axis but also in relative position parallel to the axis. This also occurs when a perspective slant is introduced to symmetric polygons [82], and it has been noted that skewed symmetry is equivalent to viewing symmetry in-depth or from a non-frontoparallel viewpoint [82,83]. As the degree of skew is increased, symmetry becomes systematically harder to detect until it cannot be discriminated from random [82].

In an attempt to explain the processing of symmetry under conditions of skewing, Wagemans et al. [41] proposed that patterns facilitating virtual four-cornered shapes (“correlational quadrangles”) can preserve the percept of symmetry under imperfect viewing conditions. These correlational quadrangles are formed through the grouping of “pairs of pairs” (i.e., the interaction between two symmetric pairs (orthogonal to the axis) in the direction parallel to the axis). These virtual shapes introduce an intermediate structure between individual local element pairs and the global symmetric pattern and preserve axis cues. When such higher-order cues are present, the global symmetry of the pattern becomes more readily identifiable than for patterns where pairs are processed more independently. Wagemans et al. [41] argue that this is because correlational quadrangles facilitate the propagation of a reference frame that strengthens the relationship between local and global pattern features. In essence, this enhances the appearance of a symmetric pattern as one independent object rather than a collection of individual, independent elements.

2.4. Shared Local Element Features

When elements are symmetrically positioned (as in Equation (1)), it is generally beneficial to symmetry perception if they share key features, such as color [84,85], luminance polarity [86,87,88,89,90] or element orientation [91,92,93,94,95]. Even when the more global pattern features discussed above are optimised, manipulating these local features can significantly impact symmetry salience. The factors that have this effect are likely to indicate critical properties of the detection processes. The following sections provide an account of what has been learnt by manipulating element properties.

2.4.1. Luminance Polarity

The direction of luminance variation drives different pathways in early vision; positive polarity dots (brighter than background) are processed via ON-channels, while negative polarity dots (darker than background) are processed via OFF-channels, and the two channels are independent in early vision [96,97]. Evidence from global motion and global form research where grouped or paired dots can act as signal or noise show that the proportion of signal dots required to distinguish a partially structured pattern from a random pattern is significantly higher when local dot pairs contain both luminance increment and decrement information compared to a single matched polarity [98,99,100]. Dots of opposing luminance polarity within the same symmetric pair fail to satisfy Equation (1) and should not readily convey symmetry information if they are processed by separate channels, even if they are perfectly spatially symmetric.

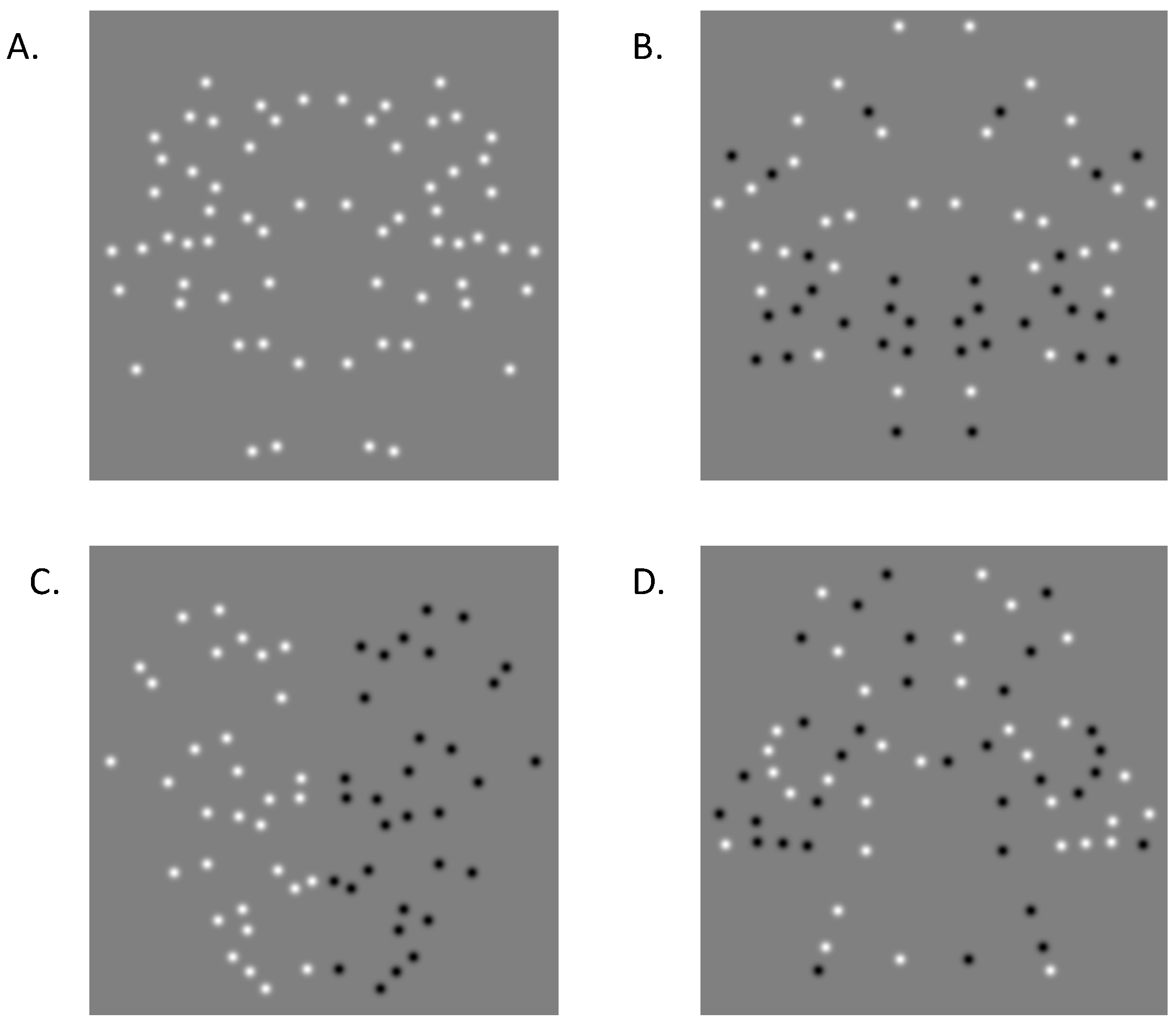

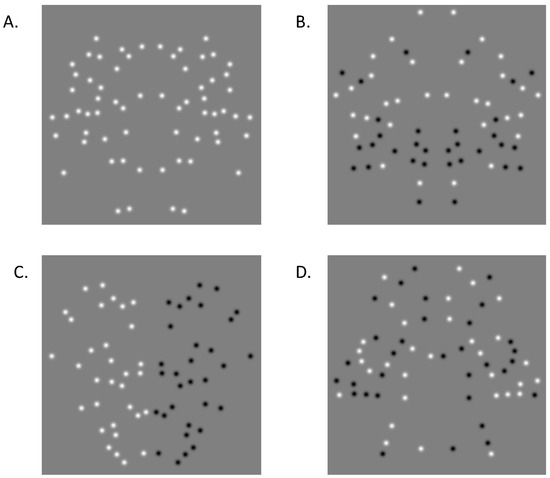

An early investigation by Zhang and Gerbino [90] found that in symmetric patterns, both light and dark pairs contribute equally when discriminating symmetry from equivalent noise patterns. Both patterns had lower detection thresholds compared to patterns with opposing intrapair polarity, regardless of whether negative correspondences were randomly distributed across the axis (Figure 3D) or segregated on either side of the axis (one side all negative, the other all positive; Figure 3C). This was interpreted as supporting a contrast-sensitive point-by-point matching process. Wenderoth [89] conducted a similar experiment which largely supported Zhang and Gerbino’s [90] initial findings: detection performance for the all-polarity matched (Figure 3A) and pair-matched polarity (elements match within a pair but pairs may be brighter or darker; Figure 3B) conditions was significantly better than for halves-unmatched (positive polarity one side of the axis and negative polarity on the other; Figure 3C) and pairs-unmatched (elements of opposing polarities within pairs; Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Examples of the four polarity conditions used are (A) all-matched-polarity, (B) matched-pairs polarity, (C) unmatched halves polarity, and (D) unmatched pairs polarity. All examples have 100% positional symmetry.

The literature is consistent in noting that variation in element appearance interrupts the formation of pairs and, therefore, has a significant and detrimental impact on symmetry perception. There are suggestions that symmetry in these situations is only detectable via polarity-insensitive point-matching mechanisms [88], which differs fundamentally from the mechanism by which symmetry is more typically perceived. Mancini, Sally, and Gurnsey [88] go as far as to say that the symmetry of unmatched luminance polarity patterns can only be detected via attentional mechanisms reliant on sequential searching and matching of individual symmetrically positioned elements. Of course, an alternative is a second-order contrast (but not polarity sensitive) perceptual mechanism [101,102,103], which is consistent with symmetry perception under conditions that preclude point-by-point matching strategies—such as very brief viewing times or temporal integration designs [86].Although sensitivity to pattern symmetry is much reduced in such instances (see panels of Figure 3), detection is still possible, suggesting either a second-order, contrast polarity independent mechanism is deployed [86,101,102] or, alternatively, attention-based point-matching processes to recover symmetry information [88].

2.4.2. Element Orientation

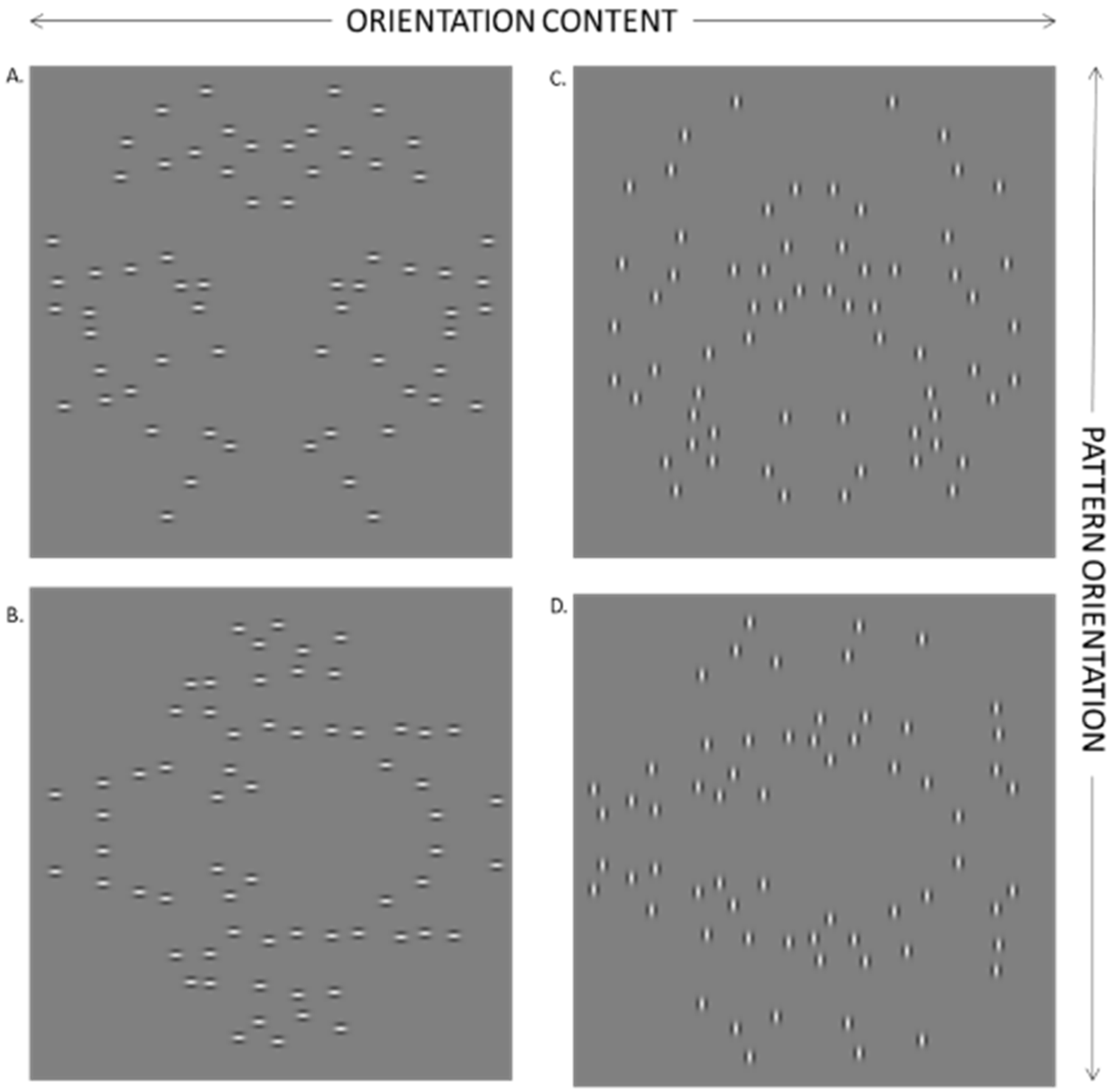

While the role of global pattern orientation (axis orientation) has attracted a lot of research interest, variations in orientation content defining a local element have been comparatively understudied (see Figure 4 for an illustration of local versus global orientation in symmetry). Like luminance polarity, different orientations are also processed by discrete neural populations in early vision [104,105,106]. Koeppl and Morgan [92], using oriented line segments, found that element position was more important for symmetry salience than absolute element orientation. This was interpreted as evidence for a “coarse-scale interpretation” [92] where element orientation does not play a significant role. Similar conclusions have been drawn by follow-up studies, which found that local orientation variation did not substantially change symmetry detection thresholds [93,95]. Sharman and Gheorghiu [95] suggest that local element orientation does not impact symmetry detection, regardless of how congruent it is with positional information.

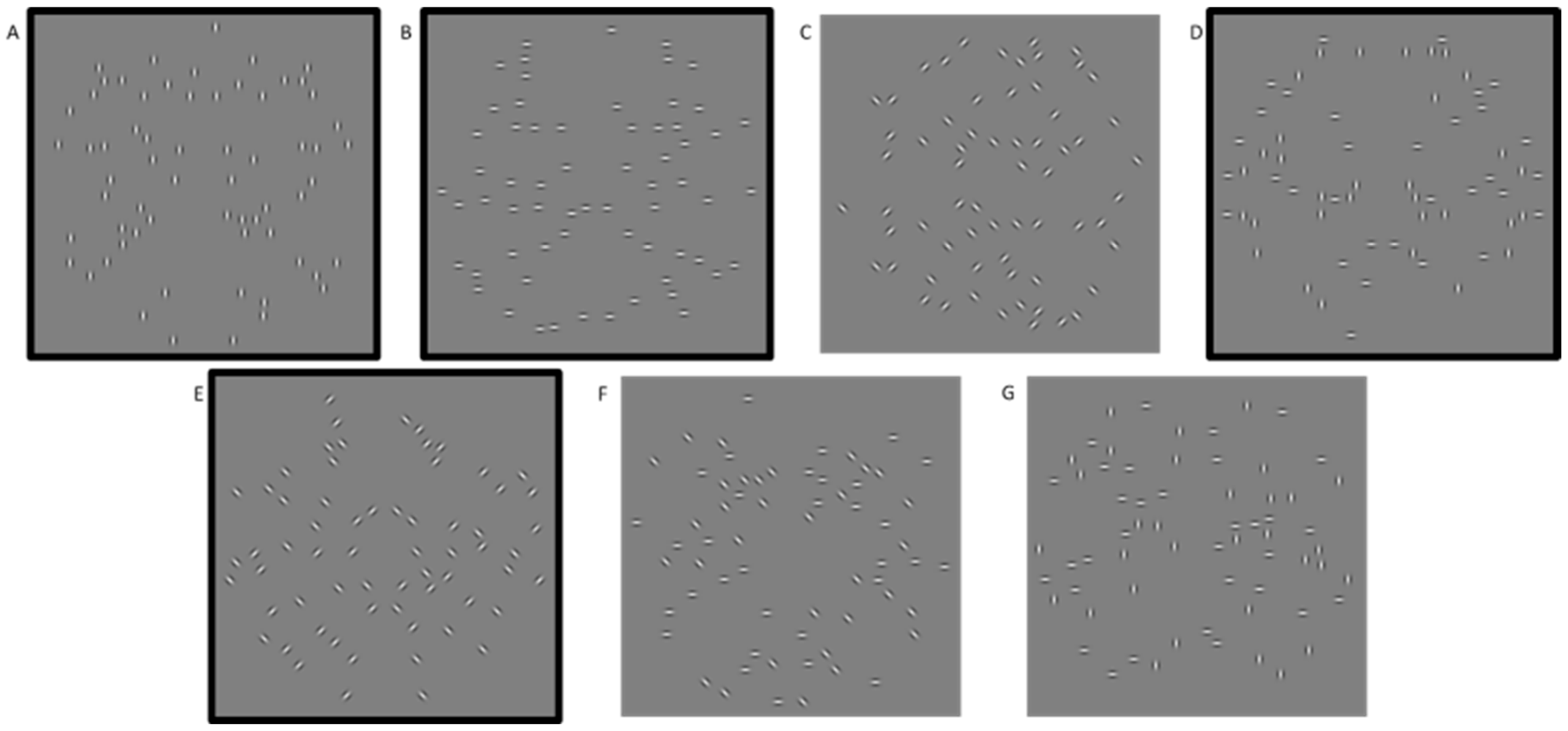

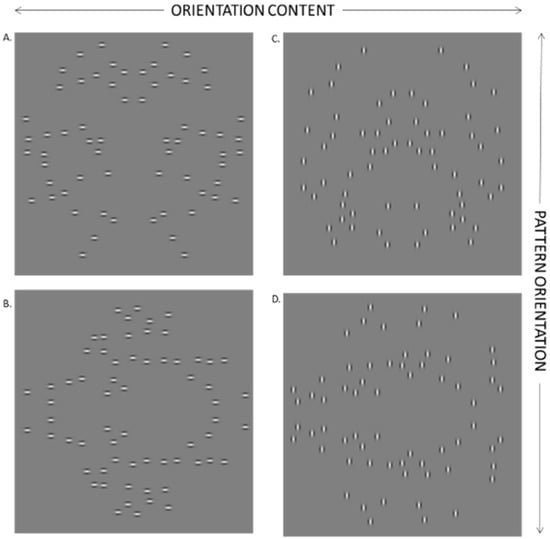

Figure 4.

Four examples of patterns with 100% positional symmetry but different element orientations [91]. Comparing the paired images vertically ((A) & (B), and (C) & (D)) shows the same orientation content with different global pattern orientations. Comparing the paired images horizontally ((A) & (C), and (B) & (D)) shows different orientation content with the same global pattern orientation. Comparison of images diagonally ((A) & (D), and (B) & (C)) shows different global pattern orientations with the same relative orientation content (parallel or orthogonal to the axis). [91].

However, Saarinen and Levi [94] found that when elements in a symmetrically positioned pair have orthogonal orientations to each other (e.g., one horizontal and one vertical element; Figure 5G), there is a significant increase in symmetry detection thresholds. Similarly, Locher and Wagemans [93] report a small but significant superiority for patterns composed of one or two orientations (when orientation within pairs is kept consistent; Figure 5A,B,D, highlighted with a bolded border) compared to patterns where the orientation of the two elements in a pair can vary randomly across the pattern (Figure 5C,F,G; no border). They attribute this to “local randomness” disrupting positional information and reducing the impression of global structure throughout the pattern [93]. Sharman and Gheorgiu [95] and Koeppl and Morgan [92] do not disrupt the mirroring of local orientation within a pair; element orientation is always varied in the same manner for both elements of a pair and thus does not introduce conflicting “local randomness” between position and orientation information that is critical here. Further, one of Sharman and Gheorgiu’s [95] key conditions used positional and orientation symmetric Gabor patterns within a randomly oriented noise field. This would conceivably have a facilitatory “pop out” effect, allowing for the detection of the proportion of common orientation elements, in addition to the proportion of symmetry signal, making it harder to determine the impact on symmetry perception alone. Together, this set of results suggests that symmetry detection mechanisms do not fully discard local orientation. Rather, like luminance polarity, the detection thresholds vary in a manner that implicates multiple orientation-sensitive mechanisms operating in parallel.

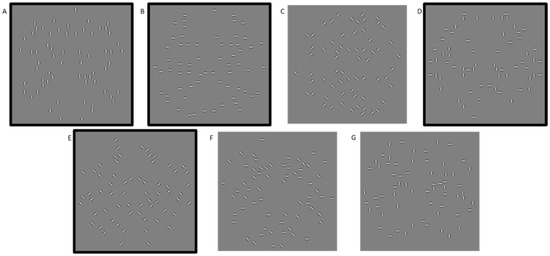

Figure 5.

Examples of stimuli from the different orientation conditions [91]. Mirrored conditions are highlighted by a solid outline (outline not shown in the experimental display) and include (A) vertical, (B) horizontal, (D) mixed-matching and (E) mirrored oblique. Matched conditions are shown in the top row, including (A) vertical, (B) horizontal, (C) matched oblique and (D) mixed-matching. Unmatched conditions are shown in the bottom row: (E) mirrored oblique, (F) 45° unmatched and (G) 90° unmatched. All examples have 75% positional symmetry and vertical symmetry axes.

Bellagarda et al. [91] methodically compared symmetry perception in patterns composed of oriented Gabor elements, where orientation was varied within and/or between element pairs. Consistent with findings in Bellagarda et al. [86] regarding luminance polarity, observers were less sensitive to underlying symmetry when symmetry could not be identified based on matching first-order features (i.e., orientation) over the axis. However, the pattern of results in Bellagarda et al. [91] was more flexible and more complex than would be expected if symmetry detection was simply attributable to differences between first- (orientation) and second-order (contrast envelope) processing alone. If this was the case, patterns where element orientation was consistent over the axis could be detected in a manner consistent with first-order features. When elements are not matched, then second-order mechanisms could extract the symmetrically placed contrast envelope, removing the conflicting orientation information. However, this explanation cannot account for the systematic variability in performance across orientation conditions. Conditions where element orientation and position are mirrored, should show the same detection performance, while conditions where element orientation is not mirrored should result in less efficient detection. In symmetry perception, mirroring information across the axis is more important than matching (i.e., translating), as noted by Rainville and Kingdom [30]. Previous studies have argued that element orientations need to be matched across the axis [94]. These studies have typically considered only horizontal and vertical elements, arguing that when two different element orientations are combined in a pair, symmetric information is disrupted. However, Rainville and Kingdom [30] instead note that paired vertical and horizontal elements are special cases of geometry in that they are both matched and mirrored in orientation (i.e., a horizontal remains horizontal when it is reflected and when it is translated). They suggest that mirroring is key in symmetry perception, and therefore, mirrored obliques, which individually differ in orientation by 90° but are mirror images of each other, should facilitate performance as effectively as horizontal or vertical pairs.

Furthermore, this also suggests that matching oblique elements should be disruptive to symmetry perception, as they do not retain the proposed critical mirroring of orientation information even though they are matched in orientation. The relationship defined in Eq 1 is true for mirrored elements, regardless of orientation. However, for matched but not mirrored elements, Eq 1 is no longer valid, and thus mirror symmetry is disrupted. Bellagarda et al. [91] showed that the mirrored oblique condition, where elements are reflected, is detected much more efficiently than matched oblique elements not mirrored in orientation. The latter needs significantly higher proportions of signal pairs to detect than other conditions in which orientation is matched and mirrored (e.g., horizontal or vertical elements, where Equation (1) is valid). Mirroring of position and orientation is, therefore, most critical to symmetry perception, and this is made clear by using a complete orientation set to allow a direct comparison of matched, mirrored unmatched and unmirrored element combinations. In sum, Bellagarda et al. [91] support a key role of element orientation in symmetry perception and also suggest that simple differences between first- versus second-order processing in the absence of additional stimulus specificities (such as comparisons of mirror reflection in orientation) are insufficient to account for the variation in symmetry processing when element orientation is varied.

2.4.3. Higher-Order Structure

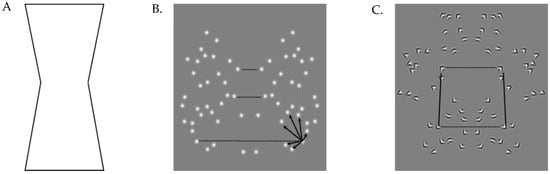

The bootstrapping, or correlational quadrangle model proposed by Wagemans, van Gool, Swinnen and van Horebeek [84], describes an intermediate level of symmetry information between the matching of individual element pairs and the global symmetric pattern. Wagemans et al. [41] defined this higher-order structure as “pairs of pairs”; that is, groups of four symmetrically positioned elements forming virtual four cornered shapes (the correlational quadrangle; Figure 6C). They hypothesised that the presence of correlational quadrangles in an array strengthens the underlying symmetry signal by facilitating axis identification and making the pattern more resistant to perturbation through additional reference frames. While early investigations showed a positive contribution of correlational quadrangles in terms of symmetry detection thresholds, nuanced investigation of the model has been limited by the available stimuli. Dot patterns, like those used by Wagemans et al. [41], do not allow for interactions between constituent elements to be controlled in any way beyond element position. Any element can conceivably interact with any other element in the array, and therefore, there are a very large number of potential projected lines between elements that can be drawn to form a number of potential correlational quadrangles.

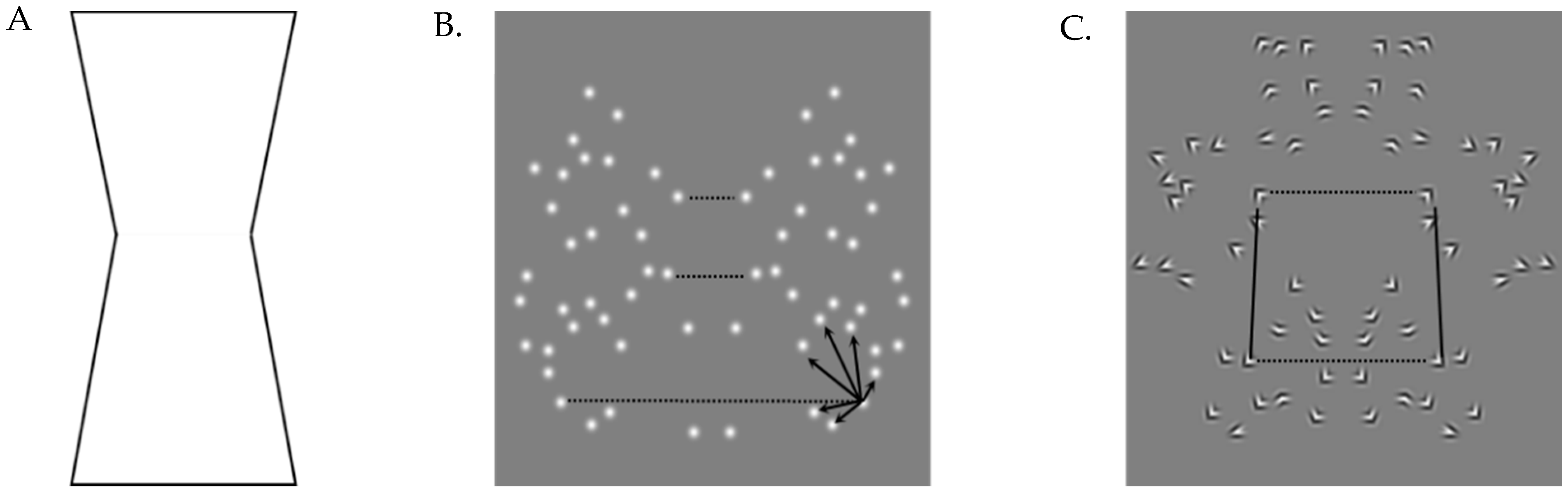

Figure 6.

Examples of symmetric stimuli with differing higher and lower-order structures include (A) a solid polygon with only high-order structure, (B) dot patterns with lower-order structure, and (C) patterns from the current study, where corner elements allow manipulation of both higher- and lower-order structure. Virtual lines dictated by element position are shown with solid lines. Potential projected lines are shown by solid lines. A lower-order structure is defined as pairwise virtual lines spanning the symmetry axis, as shown by broken likes between paired elements. The higher-order structure is highlighted by solid lines on the same side of the axis. In the (A) solid polygon stimuli, the higher-order structure may be necessary for symmetry perception as while there is some lower-order symmetry information conveyed by the corresponding points on the lines and corners; there is a paucity of discrete virtual or projected lines. Therefore, symmetry perception based on lower-order processing alone (e.g., spatial filtering) will be possible but is likely to include more noise. It is also difficult to manipulate higher or lower-order structures in isolation; often, these shapes are 100% symmetric or 100% asymmetric. In (B), symmetry is defined by virtual lines between dot elements at equivalent positions over the axis. While there may be some incidental groupings on the same side of the axis, any one dot is equally likely to co-align with any other dot and could produce infinite spurious projected lines, as shown by the arrows in (B), meaning that this incidental higher-order structure is not a useful cue. In (C), both higher and lower-order structure is explicitly manipulated by varying the coalignment of angled elements. Virtual lines within element pairs (lower-order structure, dotted lines) and projected lines between element pairs (higher-order-structure, solid lines) are defined to form intermediate structures between individual local dot pairings and the global symmetric pattern [107].

Bellagarda et al. [107] employed a third element type to try to minimize this uncertainty, as shown in Figure 7. These are the corner elements, first introduced by Persike and Meinhardt [86,87], and are formed by the intersection of two Gabor elements. Each corner had two dominant orientation components and a variable internal angle. Each element, therefore, produced definable virtual lines, and the coalignment of these lines could be explicitly manipulated to promote or inhibit the formation of correlational quadrangles. As hypothesised, observers were more sensitive to reflected than unreflected corners, and they were also more sensitive to patterns containing higher-order structures.

Figure 7.

Examples of corner elements with different internal angles. Each one is made of two halves of Gabor elements joined along the line bisecting the vertex [107].

Corners do not provide additional orientation information. Instead, perception seems to depend on a mechanism like a good continuation, which limits the elements that could be considered as part of the embedded rectangles to those providing alignment. Correlational quadrangles may be useful for symmetry perception because they provide a useful way of minimising false matches, increasing the configural information of the array while circumventing the introduction of additional noise. The results of Bellagarda et al. [107] show that they also need to form virtual lines between element pairs that are reflected over the axis but are not necessarily horizontal in order to form these quadrangles. This suggests that an adequate account needs to include both matching between elements and between element pairs.

2.5. Summary

- Symmetric patterns with vertical axes are perceived more efficiently and with lower signals than patterns with other axis orientations. The exception to this is when patterns contain more than one axis; additional pattern axes improve symmetry detection, with the best performance consistently identified for patterns with four axes of symmetry.

- The integration region around the symmetry axis is critical for symmetry detection, and it also plays an important role in the pattern outline. This suggests that while symmetry is dependent on the precise local positioning of individual elements, it is processed holistically as a global pattern.

- Distortion of individual element position, referred to as skewed symmetry, disrupts symmetry perception.

- Luminance polarity manipulations implicate second-order processing in symmetry perception since symmetry is still detectable when element polarity is different across the axis. Similarly, element orientation also impacts symmetry detection when orientations are not reflected within symmetrically positioned pairs. Symmetry remains detectable in these cases (unmatched polarity and unmirrored orientation) but with higher detection thresholds.

- A higher-order structure, formed by the relationship between pairs of paired elements, provides additional structural configural information, strengthening the symmetry percept of the overall pattern by minimising false matches and the impact of skew.

3. Mirror Symmetry in Time

Our visual world is complex and constantly changing. This presents a fundamental challenge for the human visual system, requiring it to be fast and flexible enough to accommodate frequent unexpected changes in input but stable and accurate enough for reliable identification of objects. As a symmetric object moves through space, its appearance changes, but other aspects, such as symmetry, remain relatively constant and thus can facilitate recognition. This perceptual constancy is fundamental for extracting consistent shape information in a dynamic 3D world [108] so that object recognition remains consistent across changing viewpoints, orientations and viewing conditions. Here, we build on the spatial research reviewed above to consider dynamic symmetry processing, that is, how local information is integrated across time into a global percept of symmetry.

The role of time and temporal factors in symmetry perception can be considered in a number of ways. For example, we know that symmetry is detected within a few tens of milliseconds when matched elements are presented simultaneously [50,64,109]. One early and important investigation into the role of time in symmetry perception was conducted by Hogben, Julesz and Ross [110], who asked over what time period can the visual system integrate symmetric information within the dot-pairs that form the symmetric pattern? Using a point plotting oscilloscopic system, two streams of very short lifetime dots (reduced to 1% brightness in 10 ms) were presented such that they formed symmetric pairs (e.g., one stream was the left side of the symmetry axis, the other stream was the right side). One stream of dots was temporally offset relative to the other so that while elements were always symmetrically positioned across the axis when they were present, there was a period of time separating the onset of each element in the pair. Hogben, Julesz and Ross [110] found that if this temporal delay between elements in a pair did not exceed 50–90 ms, the symmetry in the array could be accurately detected. If this delay duration was exceeded, the pattern was indistinguishable from random dot patterns with no temporal delay. This result showed that just as the visual system can combine elements across space into a global percept of form, so too can it integrate this information across time. Hogben, Julesz and Ross [110] show that with longer delays, the elements of the pair fail to stimulate the underlying processes within a critical time window. Jenkins also obtained a similar result for translational symmetry by Jenkins [111]. The percept of symmetry was retained up to a certain delay (approximately 60 ms, consistent with reflection symmetry), after which the patterns became indistinguishable from random noise.

3.1. Temporal Integration of Mirror Symmetry

The above studies highlight the role of temporal integration, or the combination of discrete elements or components, separated by time, into coherent pairs that can contribute to symmetry perception [92,93]. Note that this is not the same as examining the temporal integration period over which pairs may be accumulated to produce a symmetry percept. Hogben et al. [110] hypothesised that visible persistence is what permits this within-pair temporal integration to occur. Visible persistence describes a phenomenon where a briefly presented visual stimulus endures as a signal for visual processing beyond the end of its physical offset [94,95]. In the case of Hogben et al. [110], the temporal separation between the two elements in each symmetric pair was varied between 0 and 140 ms in different conditions, and so they were often not physically present in the same 10-microsecond time window, yet symmetry could still be perceived. This implies that positional information about the first dot persists in the visual system after the end of its physical lifetime, long enough to coincide with the physical onset and processing of the second element. If the delay between onsets exceeds the duration of the visible persistence mechanism assumed to be the underlying temporal integration of symmetry, information from the two elements cannot be combined, and hence, symmetry information is lost. Later research (e.g., Bellagarda et al., [86] discussed below) found a comparable 60 ms window over which symmetry can be perceived.

Inspired by Hogben et al.’s [110] visible persistence hypothesis, Niimi, Watanabe, and Yokosawa [112] also investigated the duration over which two static asymmetric dot patterns could be integrated into one globally symmetric pattern, but in their case, all the elements in one half were presented at exactly the same time. Two asymmetric patterns were sequentially presented for 13 ms in two separate intervals. While neither interval contained symmetry information, if the two patterns were successfully integrated, a globally symmetric pattern would emerge. Temporal delay, defined as the stimulus onset asynchrony (SOA) between the presentation of the two pattern intervals, varied from 0 ms SOA (i.e., simultaneous presentation) up to 427 ms. Participants had to indicate whether the combined pattern was symmetric or random (a yes/no task). Niimi, Watanabe and Yokosawa [112] found that for short delays (i.e., 13 ms and 27 ms), performance did not differ from conditions with no delay. As delay duration increased further, accuracy at identifying the symmetric patterns decreased until symmetry could not be differentiated from random. Like Hogben et al. [110], Niimi et al. [112] concluded that symmetry perception mechanisms were tolerant of some temporal jitter facilitated by visible persistence. When this delay tolerance of around 60 ms was exceeded, however, temporal integration no longer occurred, and hence symmetry was no longer perceptible.

A series of more recent studies by Sharman and Gheorghiu [113,114,115] focused specifically on the temporal integration of mirror symmetry and some of the features that may influence this process. Their initial study focused on symmetric motion in dynamic patterns, but their results showed that the number of elements and the duration of their lifetime had a bigger impact than symmetric motion on symmetry salience. Sharman and Gheorghiu [114] interpreted this as further evidence for the temporal integration of mirror symmetry and suggested their findings may be explained by the visible persistence and accrual of novel symmetry information across time, much like Niimi, Watanabe and Yokosawa [112]. In a follow-up study, Sharman et al. [115] used two novel symmetric patterns that were rapidly alternated (where all elements were presented simultaneously) pattern halves (either left or right sides of the axis). This was similar to Niimi et al. [112], where elements were randomly distributed through two temporally separated intervals. Both Sharman et al. [115] and Niimi et al. [112] mapped temporal integration in mirror symmetry using segmented patterns such that symmetry could not be appreciated without integration across the two intervals. Rather than referring to SOA per se, Sharman, Gregersen and Gheorghiu [115] instead varied the alternation frequency of patterns/pattern halves (higher frequency equates to a shorter delay duration). Consistent with the studies discussed above, Sharman et al. [115] replicated the 50–70 ms temporal integration window for visual symmetry; at longer delays, symmetry either was not perceived, or there was no advantage for dynamic (rapidly changing or alternating) over static displays (where all elements are presented simultaneously).

Bellagarda et al. [86] replicated the 60 ms upper limit for temporal integration of mirror symmetry discussed earlier [110,112,113,115] and showed this window is consistent even for patterns varying in luminance-polarity. Importantly, however, Bellagarda and colleagues also showed that the processes occurring within this window vary in a manner consistent with differences between first- and second-order perceptual processes [89,90,101]. This finding was inconsistent with the alternative attention-based hypotheses [88] as the limited lifetime of the elements precludes attention-based point matching; the second element’s lifetime is shorter than the time required to deploy attention to its location. This highlights the importance of considering temporal and spatial features of perception to better delineate underlying mechanisms. Static patterns necessarily fail to provide insight into the temporal requirements permitting temporal integration of elements within a pair, and therefore, it is unclear how performance might be limited by this processing stage. Here, the intersection of spatial and temporal features unveiled important features required for candidate symmetry mechanisms and allowed us to rule out explicit attention-based point-matching explanations.

Bellagarda et al. [91] employed the same temporal integration paradigm as in Bellagarda et al. [86] which permitted consideration of both sensitivity and the time course of the element matching in symmetry processing, for patterns with different local orientation information (e.g., Gabor elements of varying orientation combinations). When the orientation of paired elements is mirrored across the axis such that Eq 1 applies, performance shares the same first-order characteristics seen in the matched-polarity research considered earlier, i.e., higher sensitivity but rapid decay in performance with longer temporal delays. When elements are symmetrically placed but not mirrored over the axis, such that Eq 1 does not apply to the orientation content of the pattern, even though the orientations are identical, there is a significant performance cost reflected in increasingly lower sensitivity and longer persistence duration. Consistent with findings regarding luminance polarity, when symmetry cannot be identified based on matching first-order features over the axis, observers are less sensitive to underlying symmetry, and the impact of lengthening delay is reduced. The results of Bellagarda et al. [107] argue against a straightforward linear covariation of sensitivity and persistence within the visual system. In Bellagarda et al. [107], there is no significant change in persistence estimates, even though threshold values varied significantly between conditions. This finding rejects the interpretation of those results as reflecting a need for increased processing time to compensate for lower sensitivity to the signal. Instead, sensitivity and persistence make an independent contribution to symmetry detection; change in one parameter does not necessitate change in the other. This discussion assumes the two paired elements are first detected independently and that they must both be detected within a time window of approximately 60 ms. Combinations of elements may be grouped to produce higher-order pattern information, which may assist detection if reflected across a symmetry axis.

3.2. Summary

- Symmetric information is readily perceived as long as the delay between elements within a pair does not exceed 60 ms. Beyond 60 ms, symmetry cannot be identified.

- Visible persistence is thought to underlie the temporal integration of symmetry, as it permits element locations to be retained over time. Locations can be integrated when they fall within the same temporal window.

- While the 60 ms upper limit to symmetry perception appears fixed, sensitivity thresholds and persistence estimates vary significantly depending on pattern features such as polarity, element orientation and the presence of higher-order structure, suggesting temporal symmetry mechanisms are sensitive to these features.

4. Processing Mirror Symmetry in the Brain

The neural mechanisms underlying the perception of mirror symmetry have been investigated with neuroimaging methods. Both haemodynamic and electrophysiological studies have identified consistent, automatic and symmetry-specific responses generated in the extra-striate visual cortices [116,117,118]. More recent research by Van Meel, Baeck, Gillebert, Wagemans and Op de Beeck [119] using multi-voxel pattern analyses (MVPA) and functional connectivity analyses has traced the processing of symmetry through the ventral visual stream in the human cortex. They identified increasingly holistic processing of global symmetry as they progressed to later visual object areas in the pathway (such as the Lateral Occipital Cortex (LOC) and other extra-striate regions), accompanied by greater discriminability of random versus symmetric patterns. This was interpreted as evidence for figural processing of symmetry (i.e., as an object).

4.1. Haemodynamic Signatures

Although few in number, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies in humans and primates have consistently identified an increase in blood flow to extra-striate visual areas in response to symmetric signals in patterns [120,121,122,123]. An example of this is shown in Sasaki et al. [122], with fMRI data showing symmetry-specific activation in the extra-striate regions. No symmetry-specific haemodynamic responses have been found in early retinotopic areas (e.g., V1) by any studies [119,123]. Rather, the largest haemodynamic responses are identified around V3A, V4d/v, V7 and the lateral occipital cortex (LOC) [124,125,126]. Regions in the extra-striate cortex, particularly the LOC, are implicated in object and scene processing [127,128] rather than being specialised for lower-level features such as luminance, spatial frequency or orientation variation in an image [129]. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) studies, which disrupt cortical processing in targeted areas, have also supported the role of the LOC in symmetry processing, particularly when applied over the left LOC, while participants attempted to discriminate symmetric and asymmetric patterns [124,125,126]. TMS over the fusiform and occipital face areas (FFA and OFA), which both showed some response to symmetry information, also disrupted performance [130].

4.2. Electrophysiological Signatures

Findings from electroencephalographic (EEG) investigations are similar to fMRI studies in showing a symmetry-specific extra-striate response but have permitted a more detailed investigation of the influence of stimulus features. Jacobsen and Höfel [69] found significant, sustained negativity in the EEG waveform over the occipital regions, including V1 and the LOC, in response to symmetric stimuli, now called the Sustained Posterior Negativity (SPN), and this has been demonstrated in a number of investigations [131]. Localisation studies indicate that the SPN is generated in extra-striate regions [67]. The SPN is a difference wave and reflects a significantly greater negative amplitude for symmetric compared to asymmetric images [67]. The SPN occurs relatively late, after the first negative going component (N1); the SPN is identifiable approximately 250 ms after stimulus onset, peaking at roughly 300 ms [132]; see example in Figure 1.3B from [67]. The SPN is reliably generated in response to symmetry regardless of the task participants are completing [133,134] and is also generated in response to a range of different stimulus types, including dot patterns, abstract polygons, line elements and real objects such as flowers [131,135,136].

SPN magnitude varies in response to stimulus properties in a manner consistent with psychophysical findings [137]. Mirror symmetry consistently produces the largest SPN response compared to translation and rotation symmetries, and the former is also more readily detected in psychophysical studies [131]. There is a larger response for vertical axis patterns than to horizontal axes [138] and a greater SPN amplitude for patterns with multiple symmetry axes [139]. Perspective slant, like that investigated psychophysically by Bertamini, Tyson-Carr and Makin [88], reduces the SPN, as do patterns where symmetry is manipulated to be perceived as background rather than a figure [140]. Makin, Rampone and Bertamini [141] and Wright, Mitchell, Dering and Gheorghiu [142] have shown that symmetric patterns with unmatched luminance polarities (c.f. Wenderoth [89] and Zhang and Gerbino [90]) generate a SPN response regardless of task or symmetry type.

4.3. How Is Temporal Integration of Mirror Symmetry Represented in the Brain?

A collection of recent studies from the Bertamini Lab [143,144,145,146] has considered how temporal integration of mirror symmetry may be represented by the SPN. As alluded to by its name, the SPN is a sustained response that continues after stimulus offset [143]. Consistent with Niimi et al.’s [112,147] dynamic stimulus advantage, investigations into SPN priming have shown that the SPN is enhanced and extended by the rapid sequential presentation of novel symmetric patterns with a common axis of symmetry [148]. This is consistent with temporal integration of consistent symmetry axis information even across changing patterns, as suggested by Niimi et al. [112,147] and Sharman and Gheorghiu [95], and also suggests that temporal integration can be assessed using the SPN.

Rampone et al. [144,145] used dynamically occluded polygons where no explicit symmetries were present on the screen at any point. Only one-half of the shape was present at any one time, meaning the presence of symmetry in the shape was only identifiable following the temporal integration of the two halves. They showed that an SPN was reliably generated approximately 300 ms after the second half of the occluded polygon was presented, but only if the two sides were symmetric. As the SPN is a symmetry-specific response, it can only be generated if temporal integration is successful. If the occluded polygon was asymmetric, no identifiable SPN was produced. Follow-up investigations [144] found that the SPN generated following temporal integration is modulated by stimulus features in the same manner as for static symmetry patterns where all component elements are always presented simultaneously without the necessity of temporal integration [67]. To our knowledge, this study constitutes the first evidence of temporal integration of visual mirror symmetry from an EEG or neuroimaging perspective. More recently, Wang, Cao and Xue [149] have shown that a symmetry-specific SPN is generated in response to the temporal integration of symmetric faces but has a distinct time course when compared to the face-selective N170 response.

4.4. Functional near Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS)

Bellagarda et al. [150] employed functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) to study neural responses to temporal integration of visual mirror symmetry. fNIRS uses the optical properties of reflected near-infrared red light to measure relative changes in cortical oxygenated and deoxygenated haemoglobin in response to visual stimulation [151,152,153,154]. This is similar to the Blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) response focused on in fMRI studies [151].

Bellagarda et al. [150] intended to replicate and extend the EEG data in Rampone et al. [144,145] by providing an insight into how temporal integration of mirror symmetry may be reflected in haemodynamic responses. The fNIRS analysis showed a symmetry-specific haemodynamic response over the extra-striate regions of the visual cortex, and this response was identifiable when no or a brief temporal delay (0 ms or 50 ms) was present within element pairs. The magnitude of this response (i.e., size of the total change in haemoglobin compared to baseline levels) scaled with increasing delay; longer temporal delays produced a smaller and less localised response. When delays exceeded 60 ms (up to 100 ms delays were tested), and the patterns were therefore not distinguishable from random patterns perceptually, no symmetry-dependent changes in oxygenated and deoxygenated haemoglobin were identified. As in fMRI studies, no symmetry-specific response was found in V1 and surrounding areas. However, the symmetry response identified using fNIRS was substantially more medial than that shown in previous EEG and fMRI studies, which predominantly implicate the lateral occipital cortex [125,126,127,155].

Similar to the argument proposed by Rampone et al. [144,145], if temporal integration is indeed more medially localised than the perception of static symmetries, this may be due to recruitment of other regions involved in processing particular stimuli or stimulus features such as faces, objects or motion [156,157]. Further to this, there is a paucity of data regarding how the haemodynamic response to symmetry might change for patterns with different stimulus or element features. Bellagarda et al.’s findings accord with Rampone et al.’s [144,145] suggestion that symmetry processing may not be solely localised to the right LOC but rather varies depending on task demands and the associated involvement of other mechanisms or cortical regions. For example, symmetry in faces may more strongly recruit the OFA, while it may be that the temporal processing component of Bellagarda et al.’s and Rampone et al.’s [144,145] tasks may be recruiting more medially located subregions (for example, involvement of parietal regions that have been implicated in more general, non-symmetry focused temporal integration studies [158] are one possibility).

4.5. Summary

- Symmetry-specific haemodynamic (fMRI and fNIRS) and electrophysiological (EEG) responses are consistently identified across studies. TMS has also been found to disrupt symmetry processing.

- Neuroimaging studies consistently find that symmetrical stimuli drive responses in extra-striate regions of the visual cortex, particularly around the Lateral Occipital Cortex (LOC). The primary Visual Cortex (V1) does not generate a symmetry-specific response. Therefore, symmetry processing primarily occurs in areas implicated in object perception rather than early parts of the visual-cortical pathway.

- Recent imaging studies find that symmetry-specific responses around the LOC are generated in response to dynamic, temporally offset stimuli. Dynamic stimuli, requiring temporal integration and motion processing, appear to recruit different brain regions compared to static patterns.

5. Models of Mirror Symmetry: The Spatial Filtering Perspective

Over the years, a number of models of symmetry perception have been proposed in an attempt to capture the diverse range of psychophysical findings. Some models are limited by virtue of the types of stimuli they are based on [159], others by limitations in the way in which they could be tested [43], or limitations in how they could be feasibly implemented within the constraints of known neural mechanisms [160,161] (see Treder [27], for a discussion of several of these models). Others have persisted in the general zeitgeist for some time before being replaced or updated as the understanding of the brain and visual system advanced. For example, the callosal hypothesis, which predicted vertical axes, was more readily detected because they aligned with the vertical meridian dividing the right and left visual fields, with the corpus callosum representing the axis as it is coincidentally a vertical axis of symmetry for the brain [33,55,61,64].

The early stages of the visual system, such as the dorsal Lateral Geniculate Nucleus (LGNd) and V1, can be considered as a set of spatial filters [162,163,164,165]. Simple cells in V1 are selective for a range of features in an image (e.g., luminance polarity, orientation and spatial frequency). When we have a bank of such cells varying in sensitivity to one particular dimension while being equivalent in all others (e.g., a large response to a specific polarity but similar responses to motion, orientation and spatial frequency), that signal dimension can be de-multiplexed to extract information on the particular stimulus property. Only this information is then passed on to higher levels by the bank of cells, thus “filtering” the image for that specific property. These individual pieces of information are then re-assembled into a meaningful interpretation of the image by regions later in the visual hierarchy [166,167].

5.1. Component Process Model

The component process model introduced by Jenkins [79] was developed as a direct rebuttal to the callosal hypothesis. One of the aims of this model was to provide a more parsimonious explanation, informed by Hubel and Wiesel’s [105] receptive field measurements of V1 cells and our understanding of spatial filtering driven by psychophysical responses to stimulus features [38]. Jenkins [79] defines symmetry as the:

“two dimensional distribution of uniformly oriented point pair elements of non-uniform size and with collinear midpoints”(p. 433)

Jenkins proposes a sequential three-step model based on this definition. The first step involves the detection of symmetrically positioned elements falling along the same virtual line, orthogonal to the symmetry axis (e.g., horizontal virtual lines for a vertical axis). This is the orientational uniformity referred to. Following the detection of orientational uniformity, the system needs to fuse these point pairs into a salient feature and then detect symmetry present in this feature. In essence, this model turns individual locally symmetric components into a singular striated structure with their midpoints representing the central symmetric axis. While it does not propose an alternative mechanistic operationalisation of the three processes, the central tenets of the component process model have endured as the basis for subsequent models.

5.2. Spatial Filter Models

Like Jenkins’ [79] component process model, spatial filter models are loosely based on the concept of detection of orientational uniformity across the axis, measuring coalignment along a central axis and fusion of these into a single recognisable feature. Dakin and Watt [28] proposed a spatial filter model of symmetry perception, which, in essence, combines Jenkins’ [79] component process model with an initial spatial filtering stage.

5.2.1. The Dakin & Watt Model

Early iterations of this model by Dakin and Watt [28] were intended to produce a biologically plausible and more general-purpose mechanism by which to operationalise Jenkins’ [79] component processes. It has been broadly demonstrated that spatial receptive fields with various preferred stimulus orientations exist in the early cortical visual system, and these filters are sensitive to a range of image features, including (but not limited to) spatial frequency, luminance and orientation [162,165]. When these filters are relatively large and have a preference for low spatial frequencies, fine details of the image are removed, and only larger spatial scale variations in luminance are retained. Structured or systematic variations in luminance are unlikely to occur by chance and are instead interpreted as signifying something salient or meaningful in the environment (e.g., an object). Dakin and Watt [28] observed that when an image with a vertical axis of symmetry is filtered with elongated horizontal Difference-of-Gaussian (DoG) filters and the output is half-wave rectified, a number of horizontal regions of activity (blobs) of varying sizes were produced. These filters are thought to represent elongated receptive fields preferring orientations orthogonal to the axis. If symmetry is present in an image, these blobs cluster with their mid-points along the symmetry axis. The image is, therefore, converted into a group of parallel-aligned stripes. The greater the degree of symmetry present in the image, the larger or more numerous the blobs are, and the greater the likelihood that their centres will fall along the symmetry axis. These filtered blobs, therefore, provide a way to quantitatively measure both the amount of symmetry in a given image and also locate the symmetry axis [28].

Dakin and Watt’s [28] model suggests spatial filtering provides a domain-general way of operationalising Jenkin’s [79] component processes of detecting orientational uniformity, co-alignment and symmetry detection. Unlike previous models, spatial filtering does not require a complex, symmetry-specific mechanism and instead uses an established, general-purpose processing mechanism in the visual system [28,29]. Dakin and Watt’s [28] model can account for a range of findings from psychophysical studies, including resistance to positional jitter of the dot elements forming a pair [47], the importance of the integration region around the symmetry axis [47,79,83] and sensitivity to variations in luminance polarity axis [86,88,89,90].

5.2.2. The Dakin & Hess Model

One aspect of stimulus dependence that is not well accounted for by Dakin and Watt’s [28] model is the influence of element orientation. Orientation in symmetry can be considered in three ways: orientation of the symmetry axis [33], orientation of local symmetric elements [92,93,94] and orientation of the spatial filters processing the pattern [29,30,168]. The original spatial filter model by Dakin and Watt [28] emphasises orthogonal spatial filters, specifically horizontally oriented filters processing vertically symmetric patterns. Symmetric pairs are defined as two elements at equivalent spatial positions on either side of the axis, which means that filters necessarily have to run orthogonally across the axis (either as one larger filter or two paired filters with spatial separation, as suggested by Rainville & Kingdom [30] below) to capture both elements.

More recent models have challenged this assumption and have considered the role of filter orientation. In particular, Osorio [168] posited that vertical filters parallel to the symmetry axis were more useful for signalling symmetry in an array than horizontal filters orthogonal to the symmetry axis. Osorio’s [168] model uses dense isotropic noise patterns and Gabor filters in the quadrature phase running parallel to the symmetry axis and emphasises the symmetry information closest to the symmetry axis. Dakin and Hess [29], however, observe that neither Osorio [168] nor Dakin and Watt [28] could account for the converging psychophysical evidence of a key role for a narrowly-tuned population of orientation channels in symmetry perception, as they only include broadband filters of a single orientation. In addition, they only chose filters that contained an implicit reflection in the two half fields.

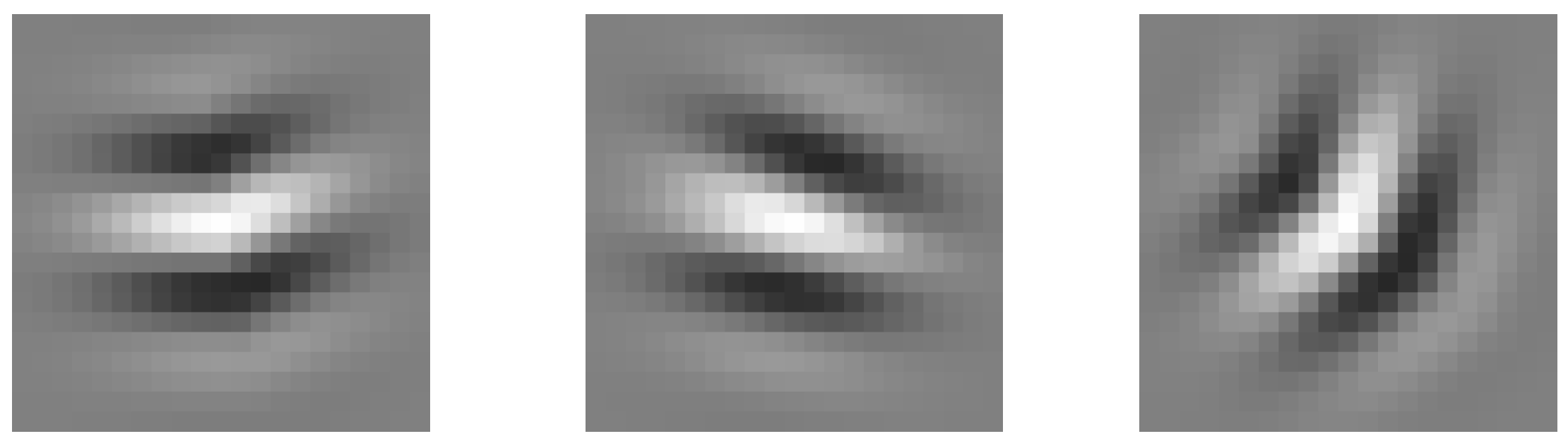

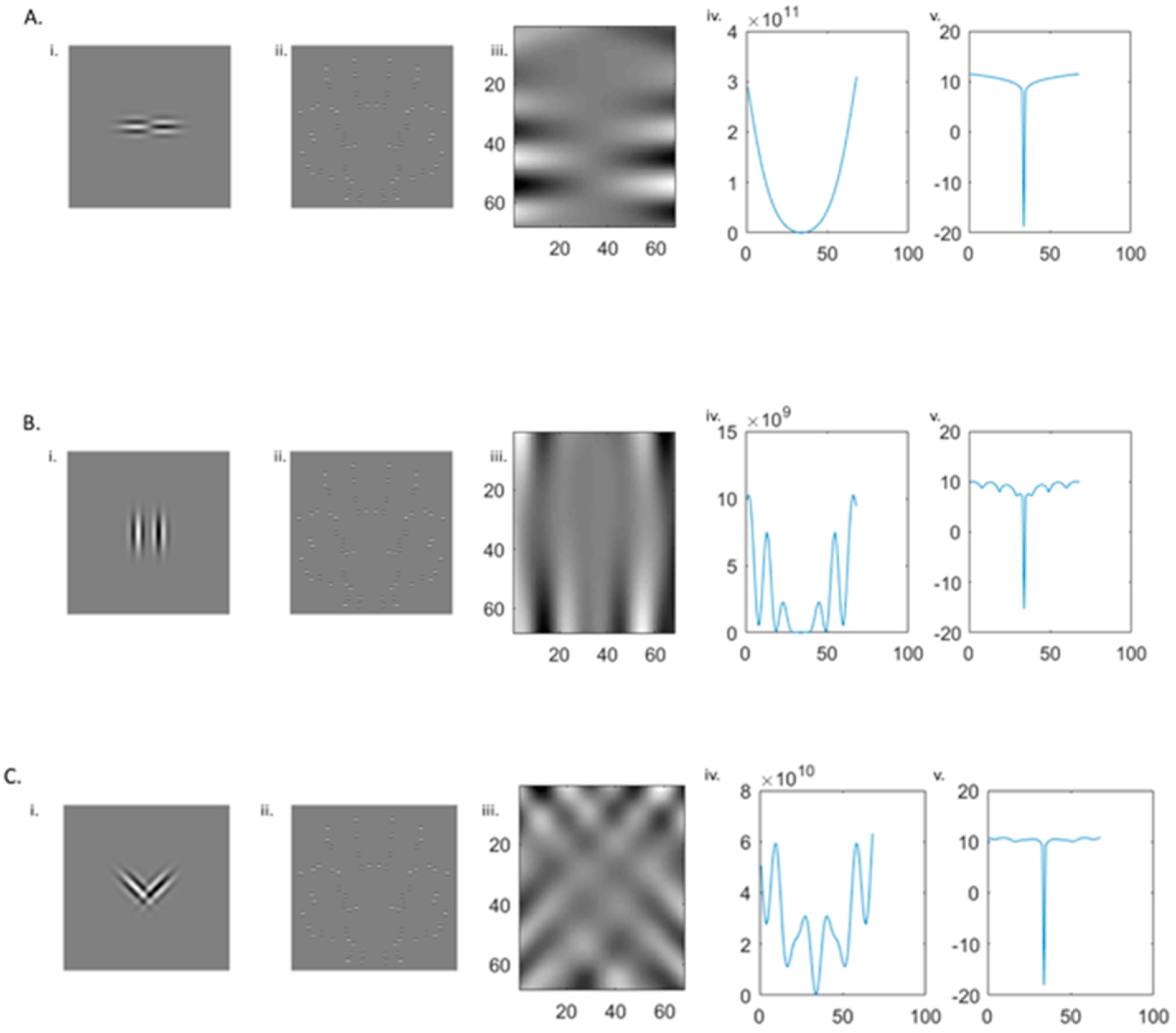

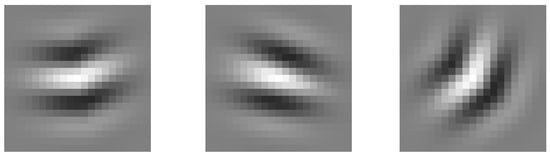

To better understand the role of filter orientation in symmetry perception, more nuanced filtering models incorporating multiple orientations have been proposed. Directly inspired by the conflicting hypotheses proposed by Dakin and Watt [28] and Osorio [168], Dakin and Hess [29] developed a variation of the original spatial filtering model [28] and directly compared vertical and horizontal filters. DoG filtering has different outputs depending on the orientation of the filter, which Dakin and Hess [29] hypothesised would affect the strength of the symmetry signal produced. Comparing vertical and horizontal filters, Dakin and Hess [29] showed a clear advantage for horizontally filtered patterns in stimuli with a vertical symmetry axis but also found this was due to orthogonality against the pattern axis. That is when the pattern had a horizontal axis, vertical filters produced a greater symmetry signal. As part of this study, Dakin and Hess [29] explored two modifications of the original Dakin and Watt [28] filtering model. Dakin and Watt [28] used linear horizontal filtering and thresholding. Dakin and Hess [29] used both a quasi-linear model with a filtering and feature alignment measure only and compared this to a version that employed an additional early half-wave rectification prior to the filtering process (the non-linear model of Dakin and Hess [29]). Where the early rectification version includes a rectification both before and after filtering, the quasi-linear model has no rectification prior to filtering. They found that the early rectification model with filters oriented orthogonal to the axis could adequately account for human performance for noise patterns that were either isotropically filtered or filtered orthogonal to the axis. When filtering occurs parallel to the axis of symmetry, the model fails to reach human performance levels regardless of the optimisation of the image window or the spatial frequencies used. While the early rectification model consistently produced the strongest symmetry signal, neither model produced a strong and consistent fit across the range of existing psychophysical data [29]. An illustration of the Dakin and Hess [29] model for two symmetric stimuli with different orientation content is shown in Figure 8 below.

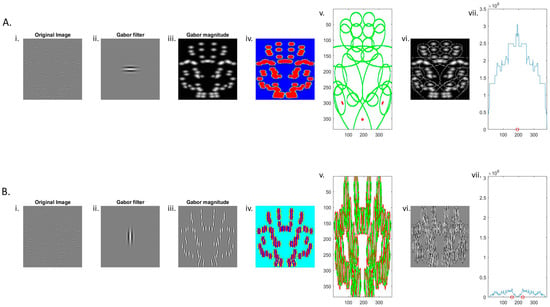

Figure 8.

Example of the Dakin and Hess model [29]. The original image is composed of 64 symmetrically positioned Gabors. (Ai–Avii) When the filter is horizontal (orthogonal to the axis), symmetry is successfully detected and blob magnitude peaks at the location of the central axis. (Bi–Bvii) However, when a vertical filter is used, there is no single identifiable peak, and the model, therefore, fails to detect the symmetry in the image. Red circles on the x-axis of the final panel (vii) show the model’s best estimate of axis location. Refer to Appendix A for a more detailed discussion of each panel and how the mode is implemented.

5.2.3. The Rainville & Kingdom Model

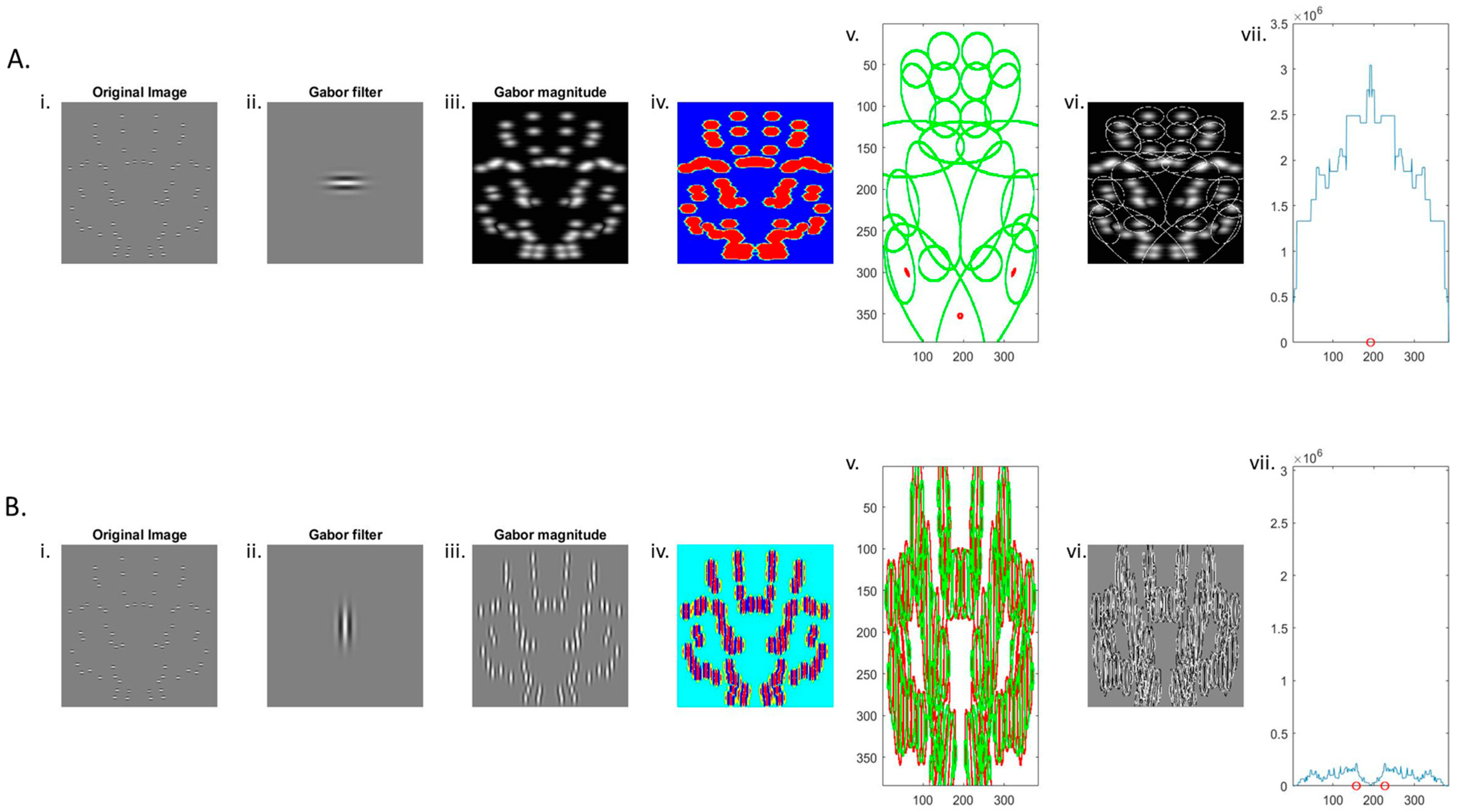

The final filtering model of interest here is the oriented spatial filter model proposed by Rainville and Kingdom [30], shown in Figure 9. Dakin and Hess [29] argue that only filters oriented orthogonal and/or parallel to the symmetry axis can convey symmetry information. In contrast, Rainville and Kingdom [30] assert that there are special cases whereby symmetry may be better represented by combinations of mirror-symmetric oblique filters (i.e., differing by ±45° from vertical such that component elements in a symmetric pair differed by 90°). They argue that symmetry is coded by a combination of mirror-oriented filters occurring prior to mechanisms coding for parallel or orthogonal positioning with respect to the axis. Rather than using a single DoG filter with one dominant orientation (vertical or horizontal) and locating the symmetry axis at the peak of the response, Rainville and Kingdom [30] employed pairs of symmetrically oriented filters in anti-phase. A cross-correlation is then conducted across the entire image, with the axis signified by a “dip” in the size of the response of the filter pair. When positioned over the axis and appropriately separated in space, the two opposing filters are equally but oppositely stimulated such that the response sums to zero.

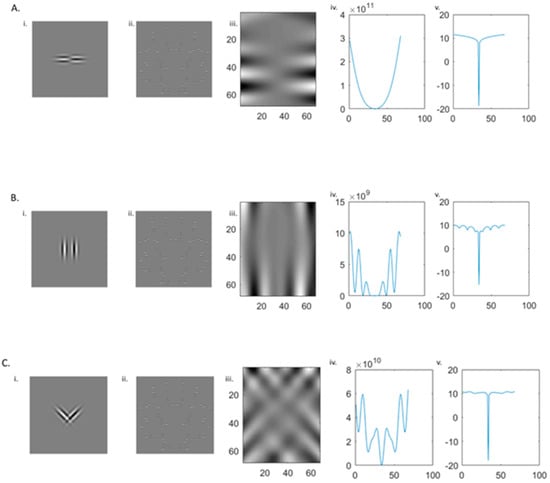

Figure 9.

Example of Rainville and Kingdom [30] model. The same original image with 64 symmetrically positioned horizontal Gabors is filtered by pairs of oriented filters. As filters are in opposite phases, the symmetry axis causes filter responses to cancel out and thus identifiable by the substantial negative change on the model outputs. (Ai–Av) Horizontally oriented filters produce the largest response. Considering (Bi–Bv) vertical and (Ci–Cv) mirrored obliques filters, the output is smaller and is more sensitive to noise.

Importantly, the Rainville and Kingdom [30] model replicates the advantage of horizontal (orthogonal to the axis) filters and a relative deficit of symmetry information when filters are vertical (parallel to the axis). However, they also show that two filters of opposing but mirror symmetric oblique orientations produce a strong response to symmetry signals. While the magnitude of this response is less than with filters of the same orientation oriented orthogonal to the symmetry axis (i.e., horizontal), the pattern of performance across different local orientations (horizontal, vertical and mirrored oblique) aligns well with human performance [30].

5.3. Assumptions of Spatial Filter Models

It is important to note that considering mirror symmetry perception from a spatial filtering perspective necessitates a few key assumptions (many of which are acknowledged by Dakin and Watt [28] and Dakin and Hess [29]). The precise implications of these assumptions for patterns with varying local features are explored below. However, while spatial filter models are biologically plausible and can account for a wide range of key features of symmetry perception in the literature, a number of other characteristics are not well encapsulated by the published models and imply that later stages of processing are also involved