Abstract

Credit card fraud detection remains a major challenge due to extreme class imbalance and evolving attack patterns. This paper proposes a practical hybrid pipeline that combines conditional tabular generative adversarial networks (CTGANs) for targeted minority-class synthesis with Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM) for classification. Inspired by symmetry principles in machine learning, we leverage the adversarial equilibrium of CTGAN to generate realistic fraudulent transactions that maintain distributional symmetry with real fraud patterns, thereby preserving the structural and statistical balance of the original dataset. Synthetic fraud samples are merged with real data to form augmented training sets that restore the symmetry of class representation. We evaluate Simple Recurrent Neural Network (RNN), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) classifiers, and a LightGBM model on a public dataset using stratified 5-fold validation and an independent hold-out test set. Models are compared using sensitivity, precision, F-measure(F1), and area under the precision–recall curve (PR-AUC), which reflects symmetry between detection and false-alarm trade-offs. Results show that CTGAN-based augmentation yields large and consistent gains across architectures. The best-performing configuration, CTGAN + LightGBM, attains sensitivity = 0.986, precision = 0.982, F1 = 0.984, and PR-AUC = 0.918 on the test data, substantially outperforming non-augmented baselines and recent methods. These findings indicate that conditional synthetic augmentation materially improves the detection of rare fraud modes while preserving low false-alarm rates, demonstrating the value of symmetry-aware data synthesis in classification under imbalance. We discuss generation-quality checks, risk of distributional shift, and deployment considerations. Future work will explore alternative generative models with explicit symmetry constraints and time-aware production evaluation.

1. Introduction

Credit cards and electronic payments have greatly facilitated personal and commercial transactions worldwide, but they have also introduced large-scale financial fraud risks. Credit card fraud not only causes direct financial losses to issuers and cardholders but also disrupts risk control and settlement processes, increases operational costs, and undermines user trust in the payment system for financial institutions. These losses can reach millions or even millions of dollars and are rising with the expansion of online transactions. Additionally, regulatory authorities are imposing higher requirements for the transparency and interpretability of anti-fraud systems, pushing the industry to seek a balance between accurate detection and low false positive rates [1,2,3,4].

From a technical perspective, credit card fraud detection faces several major challenges: First, extreme class imbalance (fraud cases constitute only a very small proportion) causes traditional loss functions and accuracy metrics to be dominated by the majority class. Second, the scarcity and diversity of fraud samples make it difficult for learners to generalize rare patterns of malicious behavior. Third, concept drift/distribution shifts require models to support online updates and maintain robustness. Fourth, mixed data types—transaction data often includes numerical, categorical, and short text fields (e.g., merchant category, card attributes)—impose additional demands on preprocessing and feature engineering. These challenges make fraud detection both a hot topic in academic research and a practical difficulty in engineering.

There has been a large body of work on credit card fraud detection; these efforts can be organized into several complementary strands that illuminate both the strengths and the limitations of existing approaches. First, classical machine learning methods, including logistic regression, support vector machines, decision trees, and ensemble tree learners such as Random Forest and gradient-boosted machines, remain widely used due to their interpretability, computational efficiency, and strong out-of-the-box performance on tabular data [5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. In practice, these models are often the baseline of choice in industry because they require moderate amounts of labeled data, are comparatively robust to modest noise, and provide convenient tools for feature importance and rule extraction. Their principal weakness is sensitivity to extreme class imbalance and complex, high-order feature interactions that are not easily captured without careful feature engineering.

Second, data rebalancing and oversampling techniques have been developed to mitigate class imbalance by increasing minority-class representation. Simple strategies include random oversampling and undersampling, while more sophisticated approaches, such as SMOTE and its variants, synthesize new minority instances by interpolation in feature space [12,13,14]. These methods are computationally inexpensive and often improve recall, but they make strong local linearity assumptions and can generate samples that lie between distinct modes or across class boundaries—particularly problematic in mixed-type (numerical + categorical) or highly sparse feature spaces. As a result, resampling can sometimes increase false positives or degrade generalization when the minority manifold is complex.

Third, generative augmentation aims to overcome the limitations of simple interpolation by learning an explicit model of the joint feature distribution. Variational autoencoders and generative adversarial networks have been applied to tabular data; among GAN variants, Conditional Tabular GAN (CTGAN) and related tabular-specific architectures incorporate techniques such as mode-specific normalization and conditional sampling to better handle mixed data types and class-conditional generation. The core advantage of these approaches is the ability to synthesize realistic, mode-aware minority examples that preserve high-order dependencies between features. However, generative methods bring new challenges: they require careful training (to avoid mode collapse), demand rigorous quality assessment of generated samples, and may introduce distributional drift if generation targets are set indiscriminately.

Fourth, deep sequence and representation models (RNN, LSTM, GRU, and, more recently, Transformer-style architectures adapted for tabular data) are effective when rich temporal or sequential transaction histories per account are available [1,3,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Such models can exploit temporal dynamics, bursts of transactions, repeating abnormal patterns, and time-dependent covariates that simple static models cannot capture. Nevertheless, sequence models require sufficiently long and representative per-user histories and are often data-hungry; their performance may degrade on datasets comprised primarily of single, static transactions or when the minority class is extremely scarce.

Finally, hybrid strategies that combine generative augmentation with robust discriminative learners have begun to emerge as a practical compromise. Tree-based learners like Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM) are particularly well-suited to tabular, mixed-type data: they scale to large feature sets, handle categorical variables without excessive preprocessing, and demonstrate stable behavior on modest training sizes. When high-quality synthetic minority samples are available, these discriminative models can exploit the enlarged effective sample support while remaining less sensitive to hyperparameter instability than deep neural classifiers.

Taken together, the literature suggests a complementary pattern: resampling methods are simple but limited by local interpolation, generative models can approximate complex joint distributions but require rigorous validation, and sequence or deep models are powerful when temporal information and sufficient data exist. However, two gaps remain in the current literature. First, there is a shortage of studies that pair tabular-aware generative augmentation with practical, production-ready discriminative learners and accompany this pairing with transparent, quantitative quality checks on generated data. Second, comparative evaluations are often reported under heterogeneous protocols, making it difficult to judge whether observed gains stem from augmentation fidelity, classifier choice, or differences in preprocessing and splitting. Motivated by these observations, this work investigates CTGAN-based conditional augmentation combined with LightGBM classification under a unified experimental protocol and introduces systematic diagnostics to validate the fidelity and utility of generated minority samples. The main contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows:

- We propose and implement an engineered pipeline for extremely imbalanced credit card fraud detection: using CTGAN for targeted synthesis of the fraud class in the training set, followed by statistical validation and post-processing of synthetic samples to control distribution shift; then training a LightGBM classifier on the augmented data with threshold/cost-sensitive tuning to balance recall and false positives.

- We systematically compare the performance of this method against traditional baseline models on a public real-world financial dataset, using business-sensitive metrics such as recall, precision, and PR-AUC, for comprehensive evaluation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Datasets

The Brazilian credit card dataset used in this study originates from a large commercial bank in Brazil and was first introduced in [1]. The dataset was released in anonymized form for research purposes and has been widely used in the fraud-detection literature. This dataset contains 374,823 anonymized transactions, of which approximately 3.74% are labeled as fraudulent. Besides fundamental card_id and transaction timestamp, each record selects 17 important attributes shown in Table 1, which capture transaction amount, timing, and several categorical descriptors of the card and merchant. The features include continuous measures (e.g., transaction amount, time intervals) and categorical identifiers (e.g., merchant category, card brand), which together allow for evaluation of methods that handle mixed-type tabular data.

Table 1.

Selected credit card dataset features.

2.2. Common Deep Learning Methods for Fraud Detection

SMOTE generates synthetic minority samples by linear interpolation between existing minority instances, which can be effective when minority class manifolds are locally linear. RNNs are a class of neural architectures designed to model sequential data by maintaining a hidden state that evolves through time. They have been widely used in problems where temporal dynamics or ordered context matter (language, time-series, user behavior). In fraud detection, RNNs can capture temporal patterns of transactions for a given account or card, such as bursts of activity or repeated abnormal sequences.

2.2.1. SMOTE

SMOTE is a classical oversampling method designed to address class imbalance by generating synthetic minority samples through interpolation. Unlike random duplication, SMOTE constructs new points in the feature space, which helps reduce overfitting and improves minority class representation.

For each minority instance , SMOTE first identifies one of its -nearest neighbors . A synthetic sample is then generated by linear interpolation:

where . This interpolation assumes that the minority class forms a convex manifold in the feature space. While SMOTE is simple and computationally efficient, it may produce unrealistic samples when feature distributions are highly nonlinear or when minority samples are sparsely distributed. These limitations motivate the use of more expressive generative models such as CTGAN.

2.2.2. Simple RNN

A Simple RNN [2,3] updates a hidden state vector at each time step as a function of the current input and the previous hidden state . Its expressivity is limited compared with gated architectures, and it commonly suffers from vanishing or exploding gradients when modeling long-term dependencies. Let be the input at time the hidden state, and the network output (for classification/regression). A common formulation is as follows:

where are bias vectors, and is a nonlinearity, typically or . Training is done by Backpropagation Through Time (BPTT). The gradient of a loss with regard to parameters involves products of Jacobian matrices across time steps. This can cause vanishing (multiplicative shrinkage) or exploding (multiplicative growth) gradients for long sequences. Practically, gradient clipping alleviates exploding gradients; vanishing gradients motivate the use of gated architectures (LSTM/GRU).

2.2.3. LSTM

LSTM [4,5] network augments the RNN cell with an explicit memory cell and gated mechanisms (input, forget, and output gates) that regulate information flow. These gates mitigate the vanishing gradient problem and enable learning of long-range dependencies. A standard LSTM cell with input , previously hidden and previous cell is as follows:

where denotes the sigmoid activation, o elementwise product, and weight matrices and biases are learned parameters. Because the cell state has linear path(s) gated by and , gradients can propagate over many time steps without vanishing as rapidly, enabling the LSTM to learn long-term dependencies. LSTMs are trained with gradient clipping; regularization (dropout between layers or on recurrent connections) can be applied carefully to avoid breaking temporal dynamics. Advantages are as follows: effective at long-term dependencies, widely used and robust; gates provide interpretable control over memory. The disadvantages include requiring more parameters and computation than a simple RNN or GRU; slower training; and care in hyperparameter tuning.

2.2.4. GRU

GRU [6] is a simplified gated cell that merges the forget and input gates into an update gate and combines the cell and hidden state. The GRU often performs comparably to LSTM with fewer parameters and sometimes faster convergence. Let be the update gate, the reset gate, the candidate activation, and the new hidden state:

interpolates between the previous hidden state and the candidate; controls how much past information to forget when computing the candidate. Because of their simpler gating and fewer parameters than LSTM, they may train faster and require less data to generalize in some tasks. However, they may be slightly less expressive than LSTM for certain problems.

3. The Proposed Hybrid Method

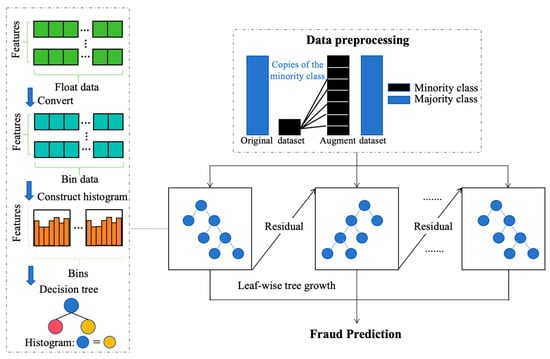

The end-to-end pipeline combining CTGAN conditional synthesis to expand the minority-class coverage with LightGBM for final classification is shown in Figure 1. More details are described in the next sections.

Figure 1.

Overall architecture diagram of the model.

3.1. CTGAN

CTGAN is a generative model specifically designed for mixed-type tabular data containing both continuous and discrete columns. Key design ideas include (1) mode-specific normalization for continuous columns to preserve multimodal distributions; (2) a conditional vector that allows conditional sampling on discrete columns so that the model can generate samples of rare classes on demand; and (3) an adversarial training framework (generator vs. discriminator) together with batch sampling strategies that mitigate the tendency to ignore minority classes. The target of CTGAN is to generate synthetic data whose first-order and certain conditional statistics match the real data, thereby improving downstream utility for supervised tasks.

Let a tabular sample be , with discrete column set and continuous column set . Introduce a conditional vector (one-hot or multi-hot encoding of desired discrete categories), and latent noise (typically standard Gaussian or uniform). The generator outputs a synthetic sample ; the discriminator outputs a real/fake score.

The conditional GAN objective is the standard min–max game:

Using binary cross-entropy loss, the discriminator and generator losses are as follows:

For each continuous column , CTGAN fits a Gaussian mixture model (GMM):

During preprocessing, each continuous value is associated with a mixture component and normalized:

The generator learns to produce (and optionally component indicators). At sampling time, is inverse-transformed to the original scale:

For discrete columns, outputs can be handled with logits and Gumbel–Softmax approximations during training:

where and is a temperature parameter; at inference, one can take arg max to obtain discrete categories. The conditional vector forces generation under a target category (e.g., TARGET = fraud). The CTGAN training procedure is given below Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 CTGAN Training |

| Require: training dataset , discrete columns , continuous columns |

| Require: epochs E, batch size B, latent dim , generator , discriminator |

| 1: /* Preprocessing */ |

| 2: Fit GMMs for each continuous feature ∈ C to obtain {,,} ▷ mode-specific normalization |

| 3: Encode discrete columns (category codes/one-hot) |

| 4: Build empirical conditional distribution over discrete categories |

| 5: Initialize generator parameters and discriminator parameters |

| 6: for epoch ← 1 to E do |

| 7: for each minibatch of size B sampled from do |

| 8: (,) ← sample_real_batch(,) ▷ training-by-sampling |

| 9: z ← sample_noise(B,) |

| 10: c ← sample_conditional() ▷ optionally oversample minority condition |

| 11: ← (z, c) |

| 12: // Update discriminator: minimize |

| 13: ← − · ((,c),(,c)) |

| 14: // Update generator: minimize |

| 15: ← − · (((z, c), c)) |

| 16: end for |

| 17: end for |

| 18: return trained generator |

3.2. LightGBM

LightGBM is an efficient implementation of Gradient Boosting Decision Trees. Its engineering features—histogram-based learning, leaf-wise tree growth, Gradient-based One-Side Sampling, and Exclusive Feature Bundling—make it both computationally efficient and effective on tabular data. LightGBM supports categorical features and allows scale/weighting mechanisms to handle class imbalance, making it well-suited to fraud detection tasks when combined with appropriate data engineering. Its objective, mathematical background, and training procedure are provided below Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2 LightGBM Training |

| Require: training data (X, ), categorical features , boosting rounds , learning rate |

| Require: regularization , leaf penalty , early stopping rounds |

| 1: convert categorical features Fc to categorical dtype (if required) |

| 2: Build LightGBM dataset object |

| 3: Initialize prediction ← 0 |

| 4: for t ← 1 to T do |

| 5: Compute gradients = and |

| 6: for each feature (or bundled group) do |

| 7: Build gradient histograms for (histogram-based binning) |

| 8: For candidate split dividing index set into and compute: |

| 9: where |

| 10: end for |

| 11: Choose best splits and grow tree leaf-wise by maximum |

| 12: Update predictions: |

| 13: Evaluate validation metric; apply early stopping if no improvement for ESR rounds |

| 14: end for |

| 15: return trained LightGBM model |

Given the training set , LightGBM builds additive trees:

And it optimizes the regularized objective at step :

where is (e.g.,) binary log loss, and is a regularizer. Using a second-order Taylor expansion, define gradients:

For a split that partitions samples into and , the optimal leaf weight and split gain are

3.3. The Proposed CTGAN + LightGBM Pipeline

Our end-to-end pipeline combines CTGAN conditional synthesis to expand the minority-class coverage with LightGBM for final classification. The pipeline leverages the conditional generative capacity of CTGAN to expand the coverage of rare fraud modes and the robust learning ability of LightGBM to form an effective detector on mixed-type tabular data. CTGAN supplies targeted diversity, and LightGBM offers efficient, interpretable learning in low-sample and mixed-feature regimes; together, they aim to improve retrieval of rare fraud instances as measured by PR-AUC and recall at fixed precision—metrics that are most relevant in operational fraud detection Algorithm 3.

| Algorithm 3 CTGAN + LightGBM Pipeline |

| Require: raw dataset , discrete columns , continuous columns |

| Require: desired fraud ratio in augmented train set, CTGAN params , LightGBM params |

| 1: // 1. split & preprocess |

| 2: Split into , , (stratified by TARGET) |

| 3: Clean and cast types; ensure discrete columns are categorical |

| 4: // 2. Train CTGAN |

| 5: ← CTGAN_train(,,;) ▷ See Algorithm 1 |

| 6: // 3. Compute required synthetic fraud |

| 7: ← |

| 8: |

| 9: |

| 10: |

| 11: while do |

| 12: ▷ prefer conditional sampling |

| 13: ▷ filter if necessary |

| 14: |

| 15: end while |

| 16: Trim to length need if oversampled |

| 17: |

| 18: // 4. Train LightGBM on augmented data |

| 19: model ← ▷ See Algorithm 2 |

| 20: // 5. Evaluate |

| 21: |

| 22: Compute metrics: PR-AUC, Recall@precision, , confusion matrix |

| 23: return model, evaluation metrics |

To apply sequence models in a reproducible manner, we construct per-card transaction sequences from the raw transactional logs and describe how CTGAN-generated synthetic transactions are integrated into these sequences. The pipeline consists of four steps: (1) Grouping and ordering: Transactions are grouped by cardholder identifier (card_id). Within each group, records are sorted by their timestamp in ascending order to reconstruct the natural temporal order of events. (2) Windowing: Fixed-length sliding windows of length are extracted from each card’s ordered history. Concretely, for a card with transactions , we extract windows , with stride 1. For the main experiments, we set . We also evaluated sensitivity to and found is the most appropriate. (3) Padding and masking: For cards with fewer than transactions, we apply left-side padding. Numeric fields in padding positions are set to zero (or column median where appropriate); categorical fields receive a reserved PAD token. A binary mask vector is associated with each window (1 indicates a real transaction, 0 indicates a padded position). During model training and loss computation, padding positions are ignored by respecting the mask. (4) Integration proceeds as follows: (a) synthetic transactions are produced only for the training partition to avoid leakage into validation/test; (b) for each generated transaction, a target card is chosen by sampling from the training card population; (c) the synthetic record is assigned an insertion timestamp that places it within the card’s historical timeframe but earlier than the validation/test split cutoff; (d) the target card’s transaction list is updated with the synthetic record and window extraction is re-run to generate new training windows containing the synthetic transaction; (e) any derived or relative fields (e.g., previous_transaction_amount) are recomputed for affected windows to preserve internal consistency. We record the exact insertion operations and ensure that all synthetic-influenced windows remain in the training set only.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Metrics

In highly imbalanced problems such as credit card fraud detection, no single scalar captures all aspects of classifier performance that are relevant to both statistical quality and business utility. We therefore evaluate models using a complementary set of metrics that together characterize (1) the ability to detect fraud (sensitivity), (2) the ability to avoid false alarms (precision), (3) a balanced summary of precision and recall (F-measure), and (4) ranking performance across operating points particularly relevant for rare events (PR-AUC). Definitions and practical notes of these metrics are given below. Let TP, FP, TN, and FN denote true positives, false positives, true negatives, and false negatives, respectively. Denote and .

Sensitivity (recall, true positive rate): proportion of actual frauds that the model correctly detects. High sensitivity reduces missed fraud (FN) and is critical when the cost of undetected fraud is high.

Precision (positive predictive value): among transactions flagged as fraud, the fraction that are truly fraudulent. Precision directly reflects the burden of manual review or customer impact caused by false positives; it too depends on the decision threshold and on class prevalence in the evaluation set.

F-measure (; common case ): the harmonic mean of precision and recall; by choosing one weighs recall more heavily (useful when missing positives is costlier), while emphasizes precision.

For (the score):

PR-AUC plots precision versus recall as the classification threshold varies. The PR-AUC is the area under this curve:

PR-AUC summarizes a classifier’s performance across thresholds with emphasis on the positive class; it is more informative than ROC-AUC when positives are rare because it directly reflects the achievable precision at different recall levels.

4.2. Experimental Results

All experiments follow strict training, validation, and test separation to avoid information leakage and to obtain reliable estimates of generalization performance. We partition the labeled dataset into an independent test set (held out and never used for model fitting or augmentation decisions) and a remainder that is used for cross-validated training and validation. For model development, we adopt a stratified -fold procedure ( by default) so that each fold preserves the overall class prevalence; this stratification is particularly important given the extreme imbalance typical of fraud detection. For each cross-validation iteration (i.e., for each fold used as the validation fold), the following sequence is performed:

Fold assignment and preprocessing. The training folds are preprocessed (missing-value handling, type casting of categorical/binary columns, and any feature engineering) independently of the validation fold. Categorical columns are explicitly set as categorical types to ensure consistent handling by both the generative model and the tree-based classifier.

CTGAN training (conditional augmentation). CTGAN is trained using only the training folds. Continuous columns are transformed using mode-aware normalization (GMM fitting), and discrete columns are encoded according to CTGAN’s requirements. During CTGAN training, we employ conditional sampling capability to focus generator capacity on the minority class (fraud). Training proceeds adversarially by alternating discriminator and generator updates; training hyperparameters (learning rates, batch size, number of epochs) are selected by preliminary experiments or modest grid-search on a validation split of the training folds. The trained generator is retained for sampling; the discriminator is used only for monitoring and synthetic-quality checks (it is not used as the final classifier in our workflow).

Synthetic-sample generation and augmentation policy. Using the trained generator, we produce synthetic transactions conditioned on the fraud label until a pre-specified target minority ratio of 30% in the augmented training set is reached. We adopted a target minority ratio of 30% in the augmented training set for two reasons. First, preliminary experiments following a grid of target ratios of 10%, 20%, 30%, and 40% revealed that performance improvements saturate beyond 30%, while higher ratios increase the risk of distributional drift. Second, 30% lies within the range typically used in imbalanced-learning studies where oversampling is combined with tree-based classifiers, providing a practical balance between class separability and distributional fidelity. Generated records are converted back to their original semantic data types (categorical codes, bounded numerical ranges) using the CTGAN output metadata. Numerical attributes are clipped to domain-feasible intervals derived from the training data’s 1st–99th percentile range to suppress rare generator artifacts.

We introduce a three-stage quantitative validation protocol to ensure that synthetic minority samples do not deviate materially from real minority data. First, we compute the two-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) statistic for each feature between real minority samples and CTGAN-generated samples. A feature is flagged if Fewer than 5% flagged features are considered acceptable. Second, we train a small logistic-regression classifier to discriminate real vs. synthetic minority samples. If the classifier achieves an AUC significantly above 0.65, the generator is deemed to exhibit noticeable distributional mismatch, and CTGAN hyperparameters are retrained (e.g., learning rate, batch size, mode-specific normalization). Finally, to verify that CTGAN preserves cross-feature relationships, we compute the pairwise mutual information matrix for real and synthetic minority samples and calculate the Frobenius-norm deviation: Values below 0.10 (normalized scale) indicate satisfactory preservation of dependency structure. Only when all three criteria are satisfied do we accept the generated samples and proceed to augmentation. This validation pipeline ensures that the synthetic data are not only marginally like the real data but also preserve higher-order relationships relevant to fraud classification.

LightGBM training on augmented data. The augmented training set (real training folds add synthetic fraud samples) is used to train a LightGBM classifier. Categorical features are passed to LightGBM using its native categorical handling. We tune LightGBM hyperparameters by monitoring PR-AUC and the chosen threshold-dependent metrics on the validation fold. Early stopping is applied on the validation PR-AUC to reduce overfitting.

Validation and hyperparameter selection. For each cross-validation iteration, we record validation metrics (PR-AUC, sensitivity, specificity, precision, and F-measure) and use these to select LightGBM hyperparameters. The entire procedure is repeated for each of the folds so that each fold serves once as the validation fold.

Apart from the proposed pipeline, this dataset stratification is also used for the following models’ construction and evaluation, including standalone Simple RNN, LSTM, and GRU, as well as CTGAN with Simple RNN, LSTM, and GRU. Besides, the performance comparison between CTGAN and SMOTE is also based on this data stratification. The selected key model hyperparameters of various models are given in Table 2 below. It should be noted that we performed systematic hyperparameter research for all models and selected the most proper hyperparameters shown in this table. The search procedures consist of a grid or random search combined with early stopping on the validation PR-AUC. For example, the hyperparameter search of CTGAN includes the latent dimension, generator and discriminator hidden layer sizes, learning rates for generator and discriminator, batch sizes, and the number of GMM components used by the mode-specific normalization step. The candidate ranges used in our experiments are summarized as follows: latent_dim ∈ {64, 128, 256}, generator_hidden_dims ∈ {[128, 128], [256, 256], [256, 128]}, discriminator_hidden_dims ∈ {[128, 128], [256, 256]}, lr_generator and lr_discriminator ∈ {1 × 10−4, 2 × 10−4, 5 × 10−4}, batch_size ∈ {256, 512, 1024}, gmm_components ∈ {5, 10, 15}, epochs ∈ {300, 500}. Taking the gmm_components selection as an instance, we evaluated 5, 10, and 15 components and compared generator fidelity diagnostics (feature-wise KS/Wasserstein tests, MMD, and a low-capacity real vs. synthetic discriminator) and downstream classifier validation performance (PR-AUC). While increasing the number of components can sometimes model more complex multimodal continuous features, on our datasets, a smaller component count = 5 produced more stable GMM fits, faster convergence, and equal or slightly better empirical fidelity according to the diagnostics above.

Table 2.

Key model hyperparameters.

All experiments were conducted on a workstation equipped with an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 5080 GPU with 16 GB RAM. The software environment comprised Python 3.9 and PyTorch 1.11.0. CUDA 11.3 and cuDNN 8.2 were used for GPU acceleration.

4.2.1. Models’ Performances

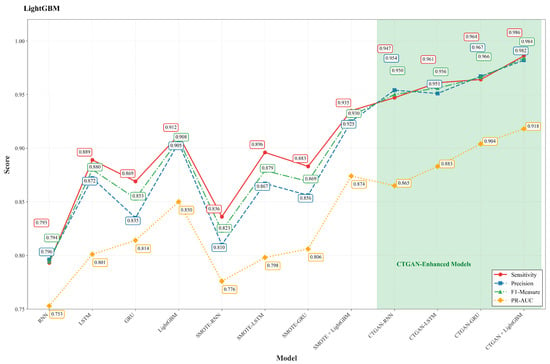

The models’ performances on the evaluated dataset are summarized in Table 3 and Figure 2. Overall, data augmentation enhances detection performance across classifiers, and CTGAN-based augmentation consistently surpasses SMOTE. Among the classifiers tested, LightGBM demonstrates the strongest baseline behavior on tabular inputs and achieves the best final results when combined with CTGAN.

Table 3.

Model performance based on the same proposed dataset.

Figure 2.

Performance metrics trend across different models.

Among the plain recurrent baselines, LSTM achieves the best performance: sensitivity = 0.889, precision = 0.872, F1 = 0.880, and PR-AUC = 0.801. GRU is close behind (sensitivity = 0.869, F1 = 0.853), while the simple RNN shows the weakest baseline performance (sensitivity = 0.793, F1 = 0.794). These results confirm that gated recurrent units (LSTM/GRU) are generally more effective than a vanilla RNN on this task when used as deep learners on tabular inputs.

Introducing SMOTE results in modest, mostly positive improvements compared to the non-augmented baselines. For example, RNN to SMOTE-RNN: sensitivity rises from 0.793 to 0.836 (+0.043 absolute, approximately +5.4% relative), and F1 score increases from 0.794 to 0.823 (+0.029, approximately +3.7% relative). For stronger recurrent models, the gains from SMOTE are smaller and sometimes negligible; for instance, LSTM shows a slight change in sensitivity from 0.889 to 0.896, approximately +0.8%, with precision and PR-AUC remaining nearly the same. LightGBM also benefits from SMOTE: sensitivity improves from 0.912 to 0.935 (+0.023, approximately +2.5% relative), and PR-AUC increases from 0.850 to 0.874 (+0.024, approximately +2.8% relative).

In contrast, augmentation using CTGAN yields substantial and consistent improvements across different architectures. For the RNN model, transitioning to CTGAN-RNN results in sensitivity increasing from 0.793 to 0.947 (+0.154 absolute, approximately +19.4% relative), while precision rises from 0.796 to 0.954 (+0.158, approximately +19.9% relative), and PR-AUC improves from 0.753 to 0.865 (+0.112, approximately +14.9% relative). For the LSTM model, moving to CTGAN-LSTM enhances sensitivity from 0.889 to 0.961 (+0.072, approximately +8.1% relative) and PR-AUC from 0.801 to 0.883 (+0.082, approximately +10.2% relative). Similarly, for the GRU model, transitioning to CTGAN-GRU increases sensitivity from 0.869 to 0.964 (+0.095, approximately +10.9% relative) and PR-AUC from 0.814 to 0.904 (+0.090, approximately +11.1% relative). These findings suggest that CTGAN significantly enhances recall (sensitivity) and the precision-recall trade-off (PR-AUC), which are critical metrics in the context of fraud detection.

The most effective configuration identified in our experiments is the combination of CTGAN and LightGBM, achieving a sensitivity of 0.986, precision of 0.982, F1 score of 0.984, and PR-AUC of 0.918. When compared to the strongest non-augmented recurrent baseline, LSTM, this configuration demonstrates significant improvements, with absolute gains of +0.097 in sensitivity (approximately +10.9% relative), +0.110 in precision (approximately +12.6% relative), +0.104 in F1 score (approximately +11.8% relative), and +0.117 in PR-AUC (approximately +14.6% relative). These advancements are not only meaningful in practical terms but also operationally significant, as the high recall minimizes the occurrence of missed fraud cases while the elevated precision helps to maintain a low false-alarm rate.

In summary, (i) LightGBM is the most effective classifier on tabular data in our study; (ii) augmentation improves performance over non-augmented training, with SMOTE providing modest gains; and (iii) CTGAN yields substantially larger, consistent improvements over SMOTE across both deep and tree-based classifiers. CTGAN combined with LightGBM is therefore the best-performing pipeline observed in these experiments.

4.2.2. Model Performance Comparison

Several recent studies have reported performance figures for fraud detection models evaluated on datasets that are similar in nature but differ in important aspects such as feature composition, class imbalance ratio, data preprocessing, model configuration, etc. To provide contextual background rather than a direct numerical comparison, we summarize the representative literature-reported results in Table 4. Despite these differences, a general trend can be observed across the referenced works: methods that incorporate data augmentation or advanced deep learning architectures tend to outperform traditional machine learning models on highly imbalanced fraud datasets. Within this broader context, our proposed CTGAN + LightGBM pipeline achieves substantially higher sensitivity, precision, and PR-AUC on the benchmark datasets used in this study. These results indicate that even when considering the variability across prior studies, the performance level reached by our approach is competitive with, and in many cases exceeds, that of state-of-the-art methods reported in the literature. This further supports the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed framework for addressing the challenge of imbalanced credit card fraud detection.

Table 4.

Comparison with other recent studies.

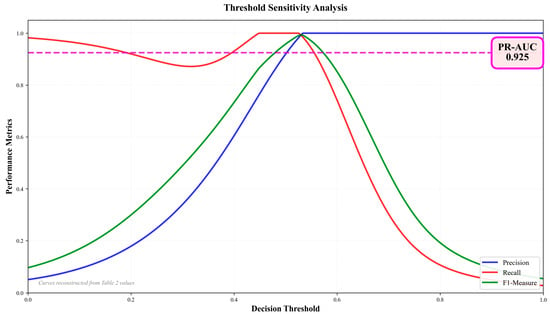

5. Discussion

We attribute the outstanding performance of CTGAN + LightGBM to two complementary factors. First, CTGAN supplies diverse, high-utility minority-class examples. This increases the effective coverage of rare fraud modes and reduces the risk that the classifier has never seen similar fraud patterns. Second, LightGBM exploits tabular structure and categorical features efficiently. It learns stable, high-precision split rules from the enriched training set. Together, the augmentation and the tree learner produce models with much higher recall while keeping false alarms low, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Threshold sensitivity analysis.

We verified that the improvements are not an artifact of overfitting. All augmentation and model selection steps were performed using strictly separated training and validation folds; the final evaluation uses an independent test set. We also estimated uncertainty by bootstrap resampling and observed that the performance increases are statistically meaningful. Nevertheless, synthetic augmentation requires careful diagnostics. We therefore inspected marginal distributions and ran a real-vs-synthetic detectability test to ensure no gross distributional mismatch. In summary, CTGAN + LightGBM delivers a practical and reproducible advance over recent published approaches on our dataset.

6. Conclusions

This study proposed a hybrid deep-learning framework that uses CTGAN-based augmentation with sequence and tree learners for credit card fraud detection. The pipeline first synthesizes minority-class transactions using a conditional GAN and then trains downstream classifiers on the augmented data. Experimental results on the public dataset demonstrate consistent and substantial gains. Models trained on CTGAN-augmented data achieved higher sensitivity, precision, F1 score, and PR-AUC than their non-augmented counterparts and several recent baselines. In particular, the CTGAN + LightGBM configuration provided the best overall trade-off between recall and false-alarm rate.

These findings show that targeted synthetic augmentation effectively mitigates extreme class imbalance and increases the classifier’s exposure to diverse fraud modes. The two-phase procedure, synthetic-data generation followed by discriminative training, proved robust across folds and on held-out test data. We acknowledge several limitations. Synthetic data can introduce distributional shifts if generation is not carefully controlled. Also, computational cost and scalability remain concerns for very large production streams. Future work should evaluate alternative GAN variants and more extensive ablation studies. It should also test the pipeline in operational, time-split deployments and explore optimizations for real-time inference. Augmenting scarce fraud samples with a conditional tabular GAN and training an efficient classifier on the enriched dataset offers a practical and reproducible path to substantially improved fraud detection.

Author Contributions

C.W. conceived and designed the study, performed data collection and statistical analysis, and interpreted the results. C.X. wrote the main manuscript text. J.L. prepared all tables and figures. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| CTGAN | Conditional Tabular Generative Adversarial Network |

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Network |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| GRU | Gated Recurrent Unit |

| LightGBM | Light Gradient Boosting Machine |

| SMOTE | Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique |

| GMM | Gaussian Mixture Model |

| PR-AUC | Area Under the Precision–Recall Curve |

References

- Forough, J.; Momtazi, S. Sequential credit card fraud detection: A joint deep neural network and probabilistic graphical model approach. Expert Syst. 2022, 39, e12795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherstinsky, A. Fundamentals of recurrent neural network (RNN) and long short-term memory (LSTM) network. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2020, 404, 132306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, W.; Cook, C.; Zhu, C.; Gao, Y. Independently recurrent neural network (indrnn): Building a longer and deeper rnn. In Proceedings of the the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Si, X.; Hu, C.; Zhang, J. A review of recurrent neural networks: LSTM cells and network architectures. Neural Comput. 2019, 31, 1235–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greff, K.; Srivastava, R.K.; Koutník, J.; Steunebrink, B.R.; Schmidhuber, J. LSTM: A search space odyssey. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2016, 28, 2222–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, R.; Salem, F.M. Gate-variants of gated recurrent unit (GRU) neural networks. In 2017 IEEE 60th International Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems (MWSCAS), Boston, MA, USA, 6–9 August 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Madhurya, M.; Gururaj, H.L.; Soundarya, B.C.; Vidyashree, K.P.; Rajendra, A.B. Exploratory analysis of credit card fraud detection using machine learning techniques. Glob. Transit. Proc. 2022, 3, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varmedja, D.; Karanovic, M.; Sladojevic, S.; Arsenovic, M.; Anderla, A. Credit card fraud detection-machine learning methods. In 2019 18th International Symposium Infoteh-Jahorina (Infoteh), East Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 20–22 March 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Awoyemi, J.O.; Adetunmbi, A.O.; Oluwadare, S.A. Credit card fraud detection using machine learning techniques: A comparative analysis. In 2017 International Conference on Computing Networking and Informatics (ICCNI), Lagos, Nigeria, 29–31 October 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Alarfaj, F.K.; Malik, I.; Khan, H.U.; Almusallam, N.; Ramzan, M.; Ahmed, M. Credit card fraud detection using state-of-the-art machine learning and deep learning algorithms. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 39700–39715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forough, J.; Momtazi, S. Ensemble of deep sequential models for credit card fraud detection. Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 99, 106883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almarshad, F.A.; Gashgari, G.A.; Alzahrani, A.I. Generative adversarial networks-based novel approach for fraud detection for the european cardholders 2013 dataset. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 107348–107368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, A.R.; Owoh, N.; Uthmani, O.; Ashawa, M.; Osamor, J.; Adejoh, J. Enhancing credit card fraud detection: An ensemble machine learning approach. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2024, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, V.; Kavitha, H.; Kumar, S.M. Credit card fraud detection web application using streamlit and machine learning. In 2022 IEEE International Conference on Data Science and Information System (ICDSIS), Hassan, India, 29–30 July 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.-H.; Jiang, J.-R. Credit card fraud detection with autoencoder and probabilistic random forest. Mathematics 2021, 9, 2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najadat, H.; Altiti, O.; Abu Aqouleh, A.; Younes, M. Credit card fraud detection based on machine and deep learning. In 2020 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Systems (ICICS), Irbid, Jordan, 7–9 April 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Alwan, R.H.; Hamad, M.M.; Dawood, O.A. Credit card fraud detection in financial transactions using data mining techniques. In 2021 7th International Conference on Contemporary Information Technology and Mathematics (ICCITM), Mosul, Iraq, 25–26 August 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Asha, R.; KR, S.K. Credit card fraud detection using artificial neural network. Glob. Transit. Proc. 2021, 2, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Alfaiz, N.S.; Fati, S.M. Enhanced credit card fraud detection model using machine learning. Electronics 2022, 11, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadim, A.H.; Sayem, I.M.; Mutsuddy, A.; Chowdhury, M.S. Analysis of machine learning techniques for credit card fraud detection. In 2019 International Conference on Machine Learning and Data Engineering (iCMLDE), Taipei, Taiwan, 2–4 December 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.