Edge AI in Nature: Insect-Inspired Neuromorphic Reflex Islands for Safety-Critical Edge Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction: Insects as Canonical Edge-AI Systems

1.1. The Fly (Stabilization Specialist)

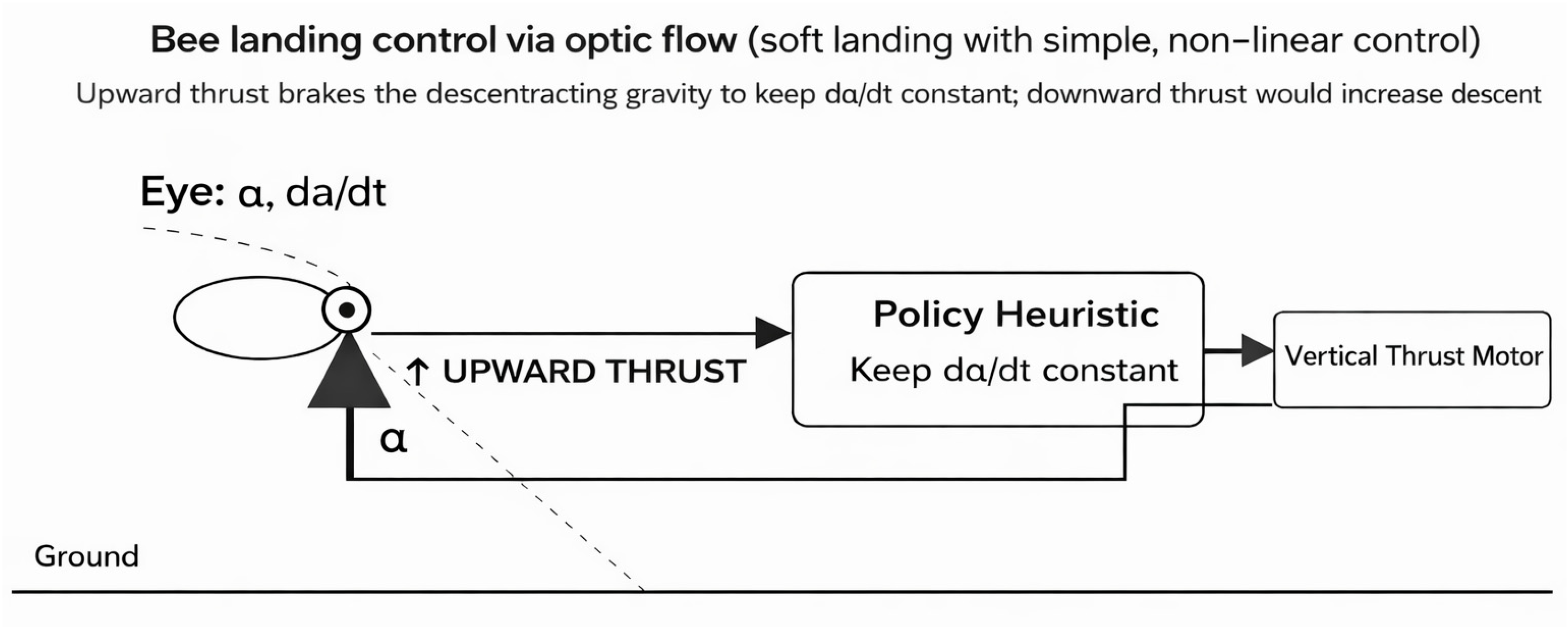

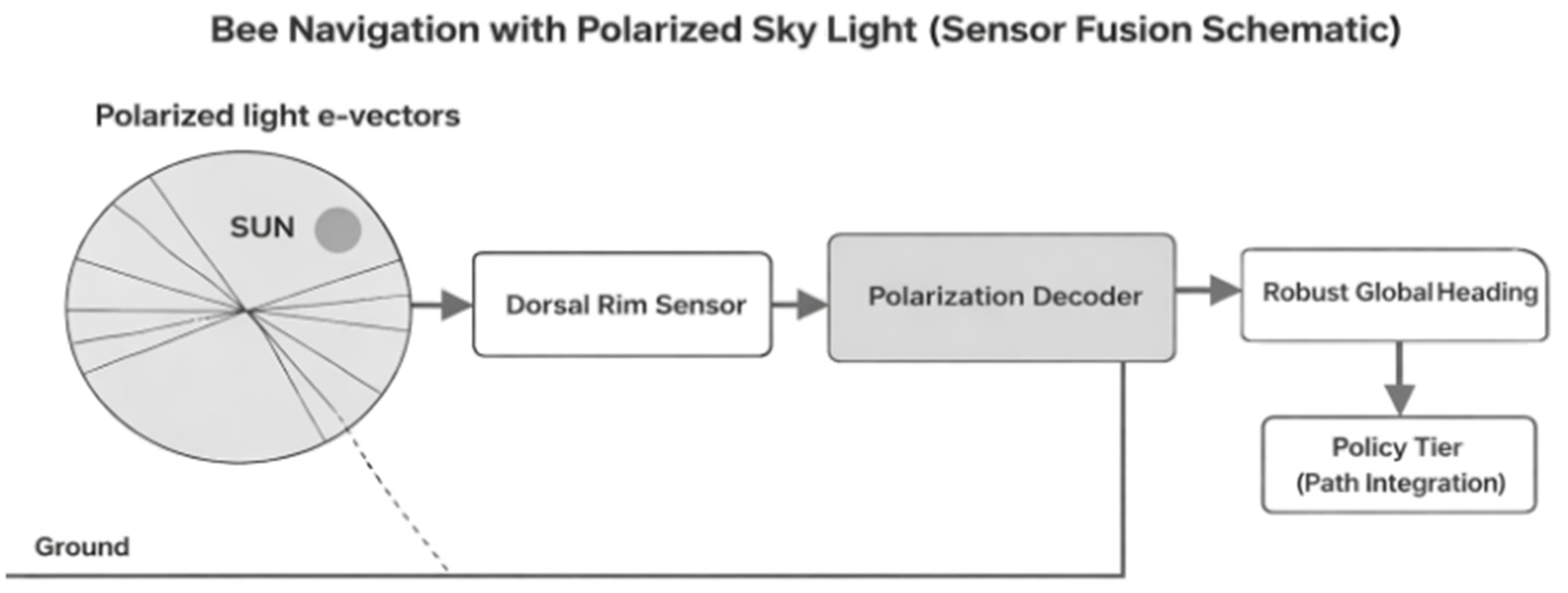

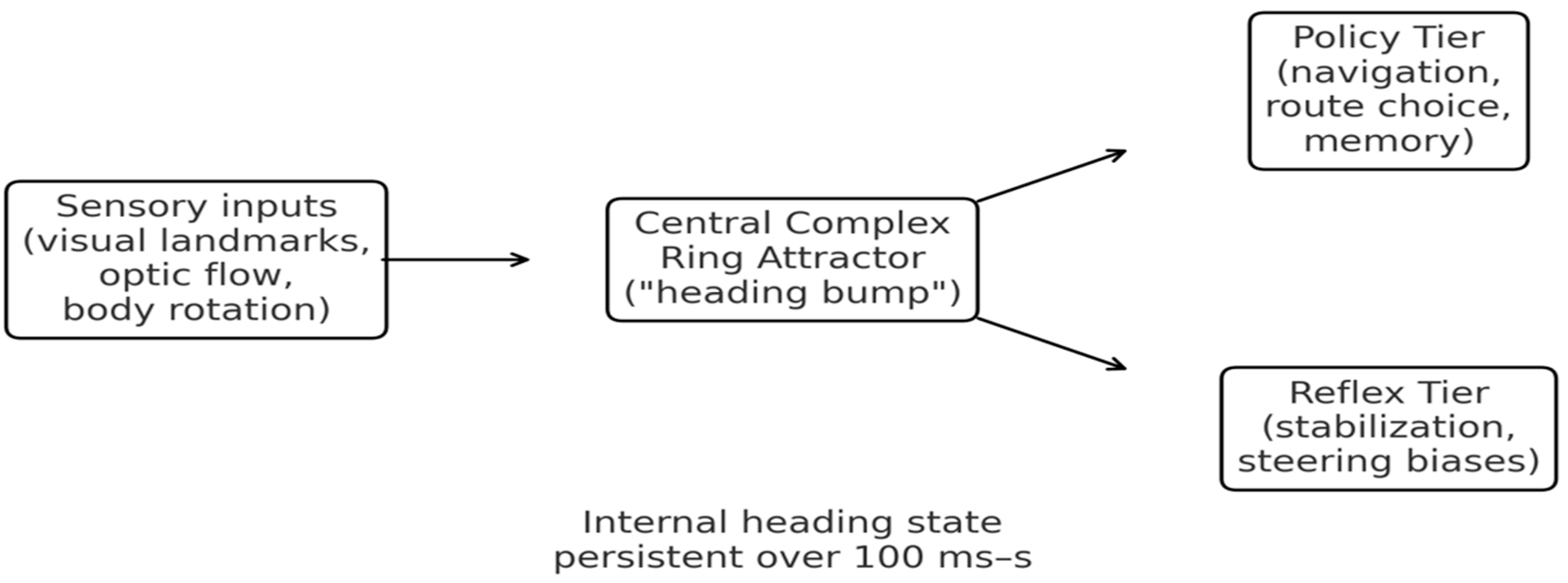

1.2. The Bee (Navigation and Task Specialist)

2. Latency-First Architecture (Biology → Engineering)

2.1. Two-Tier Control

2.2. Symmetry, Invariants, and a Control-Theoretic Interpretation

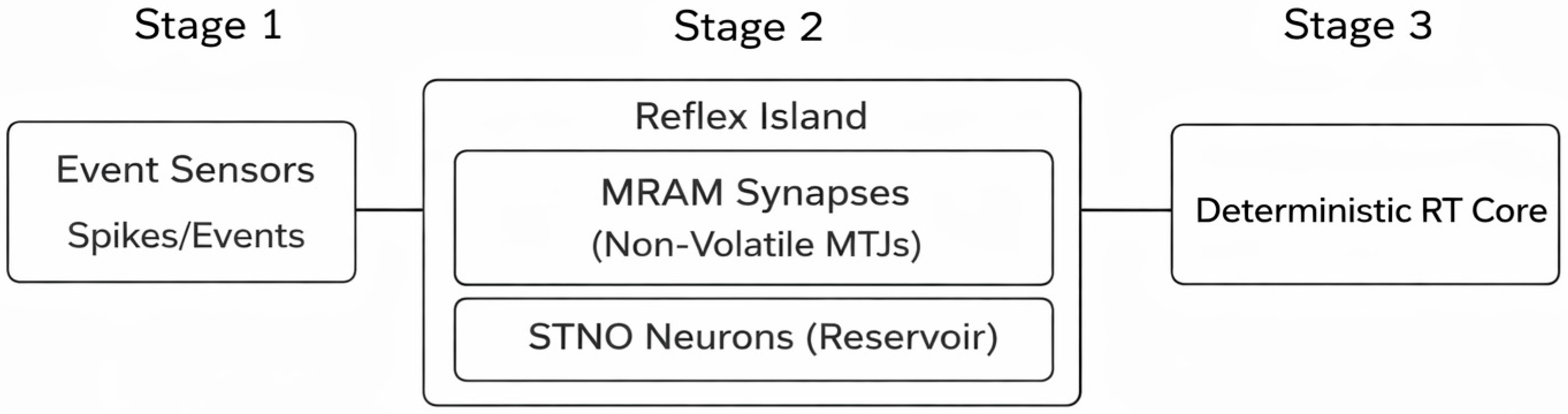

3. Neuromorphic and Spintronic Hardware

3.1. Why Neuromorphic Matches the Insect Edge

3.2. Spintronic Primitives as “Physical Synapses and Neurons”

- MRAM synapses (MTJs). Non-volatile, instant-on “innate” reflex weights, perfect for a cold-start Reflex Island [12,24]. The “synapses,” which store the network’s knowledge, are implemented using Magnetic RAM (MRAM). These are physical analogs for synapses, built from Magnetic Tunnel Junctions (MTJs). Their most critical property is non-volatility: they store the synaptic weights (the “innate reflexes”) permanently, without requiring any power. This provides two transformative advantages for an edge device.

- Sensing: Event streams from sensors (e.g., event cameras, IMU) are converted into spikes (electrical pulses).

- Compute (MRAM Synapses): Magnetic Tunnel Junctions (MTJs) in MRAM act as non-volatile synapses, storing neural network weights directly where they are used. This enables instant-on capability and near-zero standby power, emulating innate memory and reflexes.

- Compute (STNO Neurons): Spin-Torque Nano-Oscillators (STNOs) act as compact, high-frequency (GHz) spiking neurons. They can form reservoirs for processing temporal tasks and sensorimotor transformation, such as optic flow analysis.

- Actuation (RT Core): The output (set-points) of the spintronic SNN feeds a deterministic Real-Time Core (RT Core) that performs final control (PID/LQR) and drives the actuators.

4. Thermoregulation, Frequency Control, and “Natural Engine” Analogies

4.1. Discontinuous Gas Exchange (DGC) and Idle I/O Gating

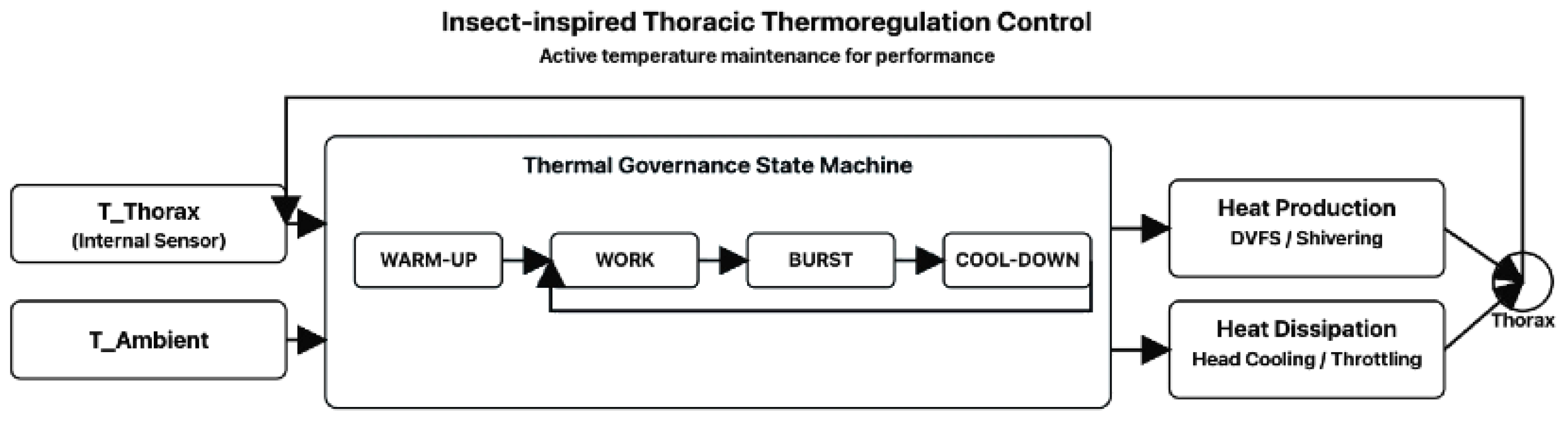

4.2. Thermal Governance as a State Machine

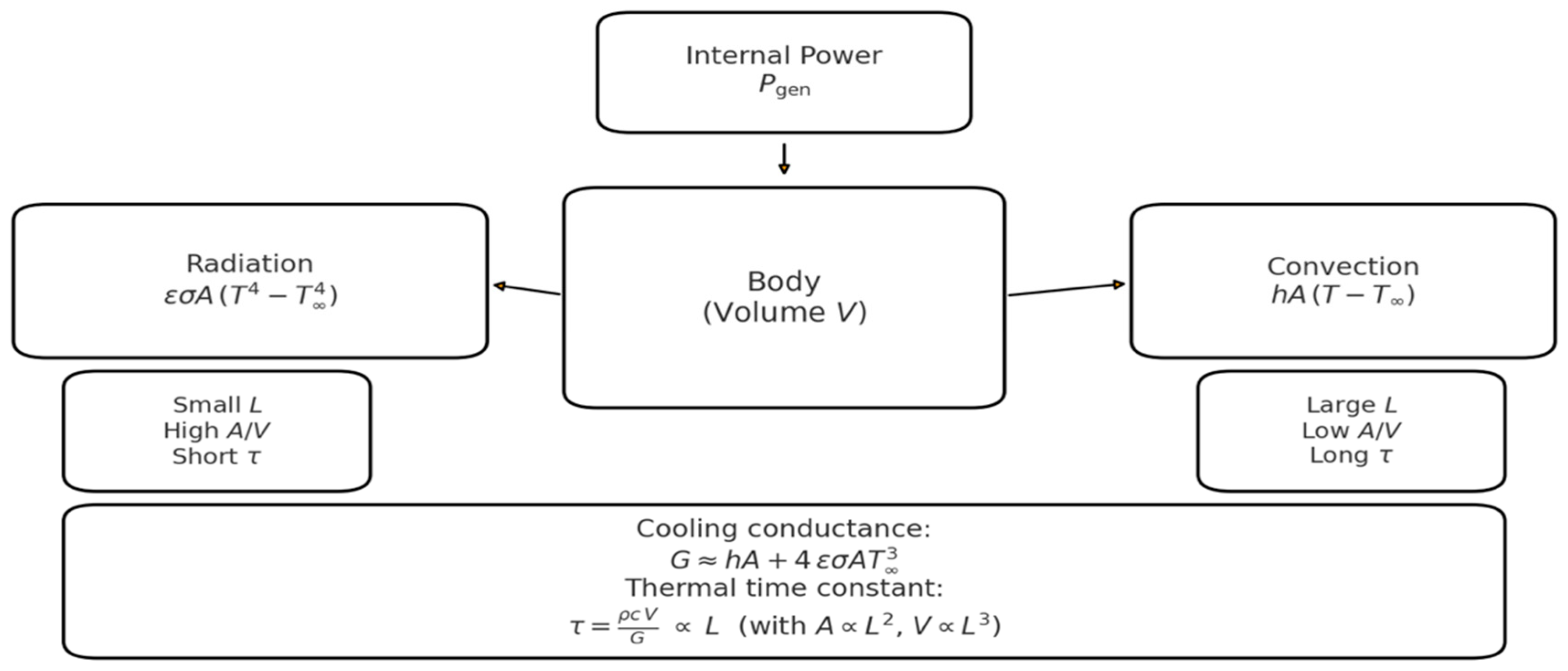

4.3. Why Thermoregulation Tightens at Small Scale (Black-Body + Convection)

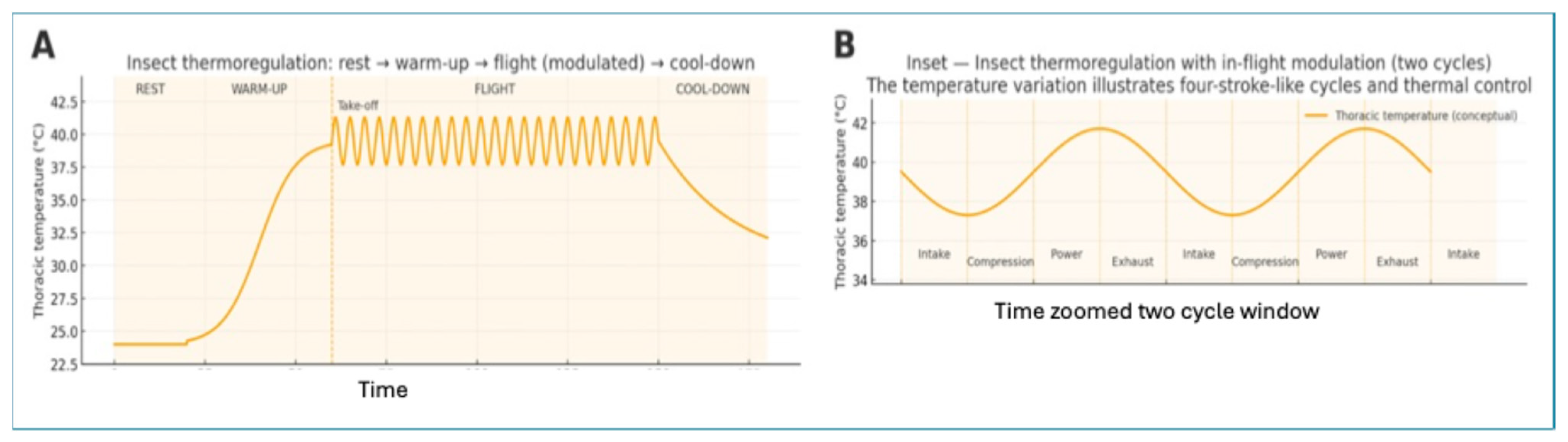

4.4. A Four-Stroke “Natural Engine” for Insect Thermoregulation

- Sensing: Thoracic temperature (for power output) and ambient temperature are monitored.

- Compute (Control): A central control mechanism (analogous to a firmware state machine) actively regulates heat production (e.g., shivering) and heat dissipation (e.g., head cooling/evaporative cooling) to maintain a performance-optimal thoracic temperature set-point.

- Engineering Analogy: This is mirrored by an Edge-AI system’s thermal governance, which uses a state machine to dynamically adjust power/clock frequency (DVFS) and sensor duty cycles based on thermal sensors and predicted load, allowing for short, high-performance bursts while preventing thermal runaway.

4.5. Propulsion Analogy: Injection/Wingbeat Frequency and Efficiency

4.5.1. Injection Event Frequency in ICEs

4.5.2. Wingbeat Frequency in Insects

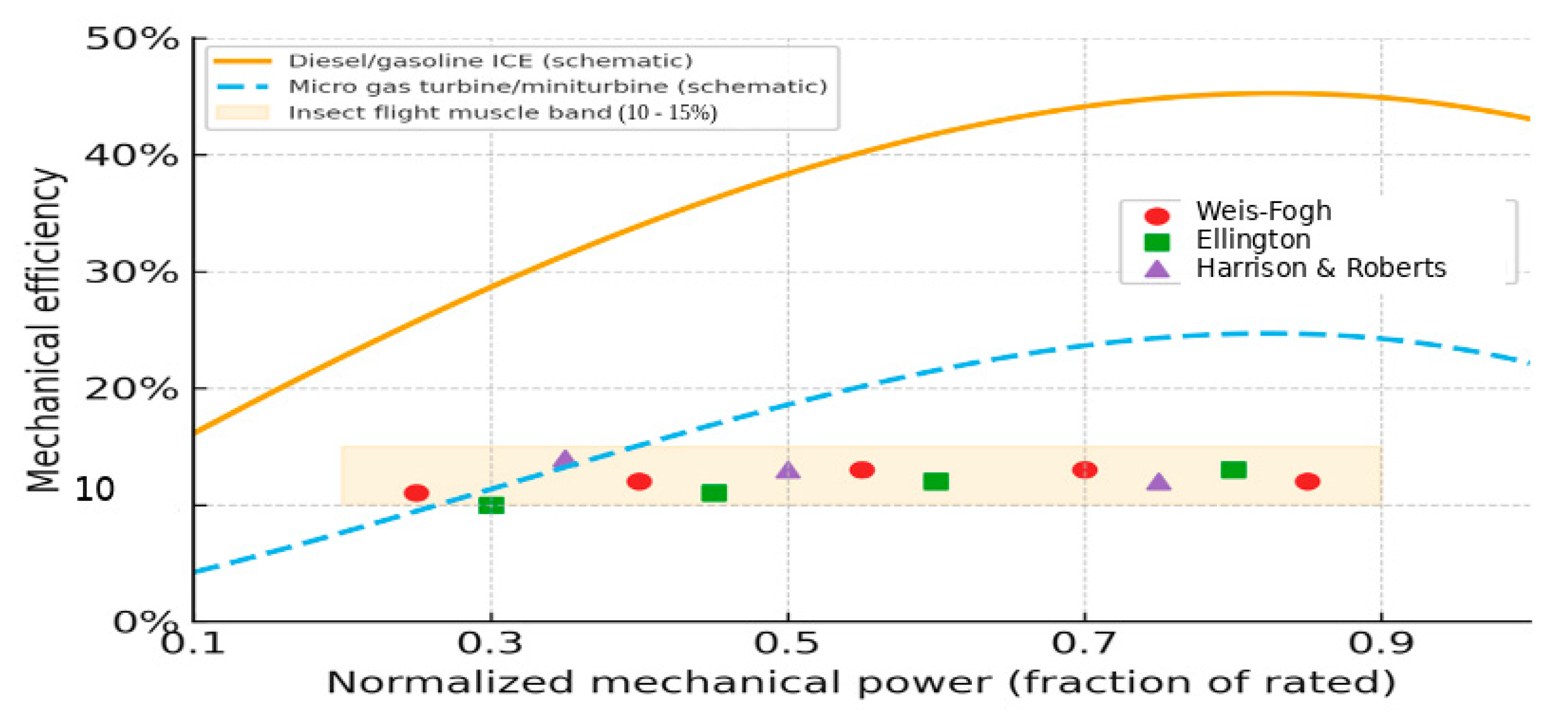

4.5.3. Efficiency Maps: Narrow Islands vs. Near-Flat Bands

4.6. Miniturbines: Scaling Limits, High Rpm, and Cold-Start Latency

4.7. Computational Governance: Engine ECUs vs. Insect Nervous Systems

4.8. Firmware Hooks: Operationalizing Natural Strategies for Timing, Thermal, and Safety Engineering

5. Use Cases and Actionable Guidance for Adoption

5.1. Design of Novel Fuel-Based Propulsion Systems with High Thrust (Make Power by Frequency—Keep Efficiency Flat)

5.1.1. Objective and Rationale

5.1.2. Architecture Blueprint (“Frequency Governor” Hybrid)

- Prime mover (constant-efficiency island): a small ICE or miniturbine run near its best-efficiency point (narrow island; Section 4.5.3 and Section 4.6).

- Electric buffer: battery + supercaps sized to absorb burst gaps between average and instantaneous power (Section 4.3 ODE + burst budgets).

- Propulsor (frequency-controlled): high-response electric motor + prop/fan/pump-jet; thrust tracks motor electrical frequency, keeping mechanical efficiency high across output range (insect analog).

- Power electronics: bi-directional DC/DC + inverter; reflex-class PWM at kHz.

- Reflex Tier: MRAM-resident, instant-on controller executing stabilization and thrust commands at kHz (mirrors thoracic reflex loop).

- Policy Tier: slow planner (routing, mission, optimization), exporting only goal states.

- Thermal governance: the state machine from Section 4.2 enforces WARM-UP → WORK → BURST → COOL-DOWN with thermal-debt accounting from Section 4.3.

5.1.3. Control Strategy (Reflex/Policy Split)

5.1.4. Hardware Patterns by Domain

- Road (range-extender)

- A 20–60 kW ICE or microturbine @ island → 400–800 V DC link; 200–400 kWh battery + cap bank sized for bursts.

- Propulsor: axle motors with field-oriented control (FOC); thrust = torque request = frequency (electrical).

- Outcome: city stop-go handled by the buffer + frequency control (insect-like), engine sits at steady island → flat real-world efficiency.

- Air (distributed electric propulsion/hybrid)

- A 30–150 kW miniturbine-generator at island (cf. Section 4.6); high-rpm and start latency hidden by buffer.

- Multiple small props per wing; per-motor frequency sets local thrust, enabling gust rejection with Reflex kHz loops.

- Outcome: safe, responsive thrust modulation without throttling the turbine off-design.

- Water (pump-jet/prop)

- Diesel-gen at island; pump-jet thrust from impeller frequency; cavitation avoided via Reflex watchdogs (pressure/accel).

- Outcome: smooth low-speed thrust with prime mover steady; excellent station-keeping.

5.1.5. Sizing and Math Hooks (Quick Rules)

5.1.6. Safety and Certification Hooks

- Freedom-from-interference (FFI). The Reflex Tier runs on a pinned core (or dedicated neuromorphic die) with fixed priorities, no dynamic memory, and one-way single-producer/single-consumer (SPSC) queues from Policy. All plant-stabilizing loops (thrust, torque, braking) close entirely inside this island. Policy cannot pre-empt or delay Reflex work; its influence is limited to low-rate goal states (e.g., speed corridors, thrust limits).

- WCET envelopes. For each Reflex loop, we derive a WCET budget as in Table 4, starting from sensor exposure through neuromorphic layers to PWM/FOC update. For propulsion, we target <5 ms end-to-end stabilization, with critical safeties < 1 ms. Implementation-specific WCETs are taken at the hot corner (max temperature, min supply) and must exhibit ≥30% margin versus the requirement (e.g., 3.4 ms vs. 5 ms).

- Thermal and prime-mover monitors. Die/EGT sensors feed Reflex logic that asserts COOL-DOWN when thermal debt exceeds the budget (Section 4.2 and Section 4.3). Prime-mover faults (turbine overspeed, EGT slew) trigger fuel-shed while the Reflex Tier keeps the vehicle stable on the buffer, providing a documented graceful degradation path.

- Fault campaigns. Section 5.3 details the fault taxonomy and injection methodology: transient single-event upsets (SEUs) in MRAM, STNO phase/amplitude jitter, sensor dropouts, and actuator faults are injected while verifying deadline compliance, safe-state entry latency, and bounded output deviation versus a fault-free trace. These campaigns, run on HIL rigs for the propulsion plant, provide the quantitative evidence required for SIL 2–3/ASIL-C–D allocations.

5.1.7. Validation Plan (Step-by-Step)

- HIL loop at kHz with plant models (prop, drivetrain, buffer, engine/turbine).

- Burst tests: record vs. predicted Section 4.3 curve; verify deadlines and miss counters = 0.

- Thermal cycles: alternate BURST/COOL-DOWN to validate thermal-debt controller.

- Off-design trials: hold the prime mover at the island while sweeping the thrust frequency; confirm flat system efficiency compared to stock throttle maps.

- Fault injection: sensor dropout, clock drift, memory CRC fault; verify Reflex containment.

5.1.8. Quick “Principle → Requirement → Action”

5.1.9. Insect-Inspired Fuel-Based IFEVS Thruster

Data Status, Test Conditions, and Methodology

Reference Microturbine and Comparison Basis

- Microturbine thrust and fuel flow;

- IFEVS thrust and fuel flow;

- The resulting fuel-flow ratio IFEVS/microturbine.

- Uncertainties, limitations, and mission-level projections

- The uncertainties quoted above are engineering confidence intervals derived from the following:

- Model sensitivity to assumed pressure losses and mixing efficiency (±3–4 percentage points on thermal efficiency);

- Expected calibration accuracy of mass-flow and temperature sensors (±2–3%);

- Variability in augmenter entrainment ratio and back-pressure (±0.05 on thrust multiplication);

- Variability in ambient conditions around the ISA reference (±5% in density over a 10–15 °C swing).

- Architectural implications

- Even with these conservative uncertainties, the picture that emerges is robust (Table 7):

- An insect-style prime mover whose efficiency degrades gently with load instead of collapsing away from a narrow island;

- Instantaneous response (valve/ignition limited) rather than seconds-scale spool dynamics;

- Cool, slow exhaust (~150 °C at the augmenter exit) enabling safe operation near people and structures; and

- A mechanically simple, non-rotating architecture naturally compatible with the Reflex/Policy split and WCET reasoning of Section 2 and Section 5.1.6.

5.2. Autonomous Vehicles and Micro-Robotics (A One-to-One Mapping of the Insect Edge)

Insect-Inspired Vision for Safer Cargo e-Bikes

- Latency budget for the cargo e-bike Reflex loop

- Energy budget and solar sizing

- Integration with the insect template

- A fast Reflex Tier (camera/IMU → neuromorphic looming SNN → haptic/LED) with a quantified sub-20 ms WCET envelope and clear separation from the slower route-planning Policy Tier;

- A solar-governed duty cycle where the bike operates much like an insect, balancing energy intake and expenditure over the day; and

- A largely self-charging cargo platform analogous to existing IFEVS-type systems, but with an explicit safety-critical perception shell inspired by insect vision.

5.3. Industrial Robotics and Control (Uptime and Determinism Above All)

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Glossary

| Reflex Tier | fastest safety-critical control with hard deadlines (Control). |

| Reflex Island | isolated near-sensor partition executing the Reflex Tier (Platform). |

| Reflex substrate (spintronic/CMOS) | technology implementing the Reflex Tier (Platform). |

| Policy Tier | slower mapping/planning; publishes goals to Reflex (Control) |

| FFI (freedom-from-interference) | faults/jitter in Policy can’t affect Reflex (Safety). |

| ASIL allocation | ISO 26262 safety level assignment per function (Safety). |

| DGC (Discontinuous Gas Exchange) | Closed–Flutter–Open; analogy for idle I/O gating (Biology ↔ Firmware). |

| Thermal debt | required cool-down after a burst (Thermal). |

| Set-point temperature | maintained flight-muscle band during work (Thermal/Biology). |

| Cooling conductance | linearized convection + radiation loss (Physics). |

| Thermal time constant | response time; scales roughly with size (Physics). |

| Prime mover | fuel engine/turbine kept at efficiency island (Propulsion). |

| Cold-to-idle latency | light-off to usable idle time (Propulsion). |

| BSFC map | brake-specific fuel consumption vs. rpm/load (Efficiency). |

| Injection event (micro-injection) | one pulse in a split injection (Engines). |

| Thoracic shivering | pre-flight warm-up of flight muscles (Biology/Thermal). |

| Optic flow | wide-field visual motion cue (Sensing). |

| Halteres | gyroscopic sensory organs in Diptera (Sensing). |

| Dorsal Rim Area (DRA) | polarization-sensitive zone for celestial compass (Sensing). |

| Central Complex (ring attractor) | neural compass with an activity bump (Control/Biology). |

| CPG (central pattern generator) | rhythmic actuation circuit (Control/Biology). |

| STNO reservoir | spin-torque oscillator network for temporal processing (Hardware). |

| MRAM synapse | non-volatile weight (MTJ) for instant-on reflex (Hardware). |

| DVFS | dynamic voltage/frequency scaling under thermal control (Platform). |

| WCET envelope | worst-case execution-time budget from sensor exposure to actuator update, including safety margin, defined per Reflex loop (Timing/Safety). |

Appendix A. Medical Implants and Wearable Devices (Years of Standby; Milliseconds to Act)

| Principle | Medical Requirement | Actionable Guidance |

|---|---|---|

| DGC/I/O gating (Section 4.1) | Extreme energy conservation | Closed/Flutter duty-cycling of sensing; Open on anomaly; RTC-only heartbeat during Closed |

| Spintronics (MRAM) | Instant event capture & integrity | Reflex Tier always resident in MRAM; no DRAM warm-up; log ring-buffers with ECC/CRC |

| Policy learning | Personalized thresholds | On-device adaptation (simple STDP/EMA) in Policy; export only gains/thresholds to Reflex |

| Thermal governance | Skin comfort & safety | Treat surface and battery with Section 4.2 state machine; guarantee Reflex availability while throttling analytics |

| Safety & privacy | Determinism & local data | WCET envelopes for detection; encrypted logs; on-device inference; no cloud dependency for immediate actions |

| Examples: seizure detectors, arrhythmia monitors, closed-loop neurostim; the Reflex executes detection/stim in sub-ms; Policy adapts over days; thermal protects tissue. | ||

References

- Chan, W.-P.; Prete, F.; Dickinson, M.H. Visual input to the efferent control of wing steering in Drosophila. Nature 1998, 396, 460–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, M.H. Haltere–mediated equilibrium reflexes of the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 1999, 354, 903–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egelhaaf, M.; Kern, R.; Juusola, M. Optic-flow based spatial vision in insects. J. Comp. Physiol. A 2023, 209, 487–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, D.G.; Wyman, R.J. Anatomy of the giant fibre pathway in Drosophila. I. Three thoracic components of the pathway. J. Neurocytol. 1980, 9, 753–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moses, K. Evolutionary biology—Fly eyes get the whole picture. Nature 2006, 443, 638–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, E.; Srinivasan, M.V.; Zhang, S.; Cowling, A. Visual control of flight speed in honeybees. J. Exp. Biol. 2005, 208, 3895–3905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marco, R.J.; Menzel, R. Encoding spatial information in the waggle dance. J. Exp. Biol. 2005, 208, 3885–3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Rouault, H.; Druckmann, S.; Jayaraman, V. Ring attractor dynamics in the Drosophila central brain. Science 2017, 356, 1169–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulse, B.K.; Haberkern, H.; Franconville, R.; Turner-Evans, D.; Takemura, S.-Y.; Wolff, T.; Noorman, M.; Dreher, M.; Dan, C.; Parekh, R.; et al. A connectome of the Drosophila central complex reveals network motifs suitable for flexible navigation and context-dependent action selection. eLife 2021, 10, e66039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuser, T.; Lovén, L.; Bhuyan, M.; Patil, S.G.; Dustdar, S.; Aral, A.; Bayhan, S.; Becker, C.; de Lara, E.; Ding, A.Y.; et al. Revisiting Edge AI: Opportunities and Challenges. IEEE Internet Comput. 2024, 28, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Lyu, Z.; Jiao, X.; Liu, P.; Chen, M.; Xu, J.; Cui, S.; Zhang, P. Pushing AI to wireless network edge: An overview on integrated sensing, communication, and computation towards 6G. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2023, 66, 130301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grollier, J.; Querlioz, D.; Stiles, M.D. Neuromorphic Spintronics. Nat. Electron. 2020, 3, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infineon Technologies AG. AURIX™ TC39x 32-Bit Single-Chip Microcontroller Data Sheet (v1.2), Infineon Technologies AG: Munich, Germany, 2021. Available online: https://www.infineon.com/assets/row/public/documents/10/49/infineon-tc39x-datasheet-en.pdf?fileId=5546d462712ef9b7017140bc3416145f (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Ames, A.D.; Xu, X.; Grizzle, J.W.; Tabuada, P. Control Barrier Function Based Quadratic Programs for Safety Critical Systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2017, 62, 3861–3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuman, C.D.; Potok, T.E.; Patton, R.M.; Birdwell, J.D.; Dean, M.E.; Rose, G.S.; Plank, J.S. A survey of neuromorphic computing and applications. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2022, 9, 011307. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1705.06963 (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Davies, M.; Srinivasa, N.; Lin, T.-H.; Chinya, G.; Cao, Y.; Choday, S.H.; Dimou, G.; Joshi, P.; Imam, N.; Jain, S.; et al. Loihi: A Neuromorphic Manycore Processor with On-Chip Learning. IEEE Micro 2018, 38, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indiveri, G.; Liu, S.-C. Memory and information processing in neuromorphic systems. Proc. IEEE 2015, 13, 1379–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavanaei, A.; Ghodrati, M.; Kheradpisheh, S.R.; Masquelier, T.; Maida, A. Deep learning in spiking neural networks. Neural Netw. 2019, 111, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furber, S.; Bogdan, P. (Eds.) SpiNNaker: A Spiking Neural Network Architecture; Now Publishers: Hanover, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Akopyan, F.; Sawada, J.; Cassidy, A.; Alvarez-Icaza, R.; Arthur, J.; Merolla, P.; Imam, N.; Nakamura, Y.; Datta, P.; Nam, G.-J.; et al. TrueNorth: Design and Tool Flow of a 65 mW 1 Million Neuron Programmable Neurosynaptic Chip. IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2015, 34, 1537–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BrainChip Holdings Ltd. BrainChip Akida Neuromorphic Processor 2025. Available online: https://www.brainchip.com/ (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Gallego, G.; Delbruck, T.; Orchard, G.; Bartolozzi, C.; Taba, B.; Censi, A.; Leutenegger, S.; Davison, A.J.; Conradt, J.; Daniilidis, K.; et al. Event-Based Vision: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2022, 44, 154–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milde, M.B.; Afshar, S.; Xu, Y.; Marcireau, A.; Joubert, D.; Ramesh, B.; Bethi, Y.; Ralph, N.O.; El Arja, S.; Dennler, N.; et al. Neuromorphic Engineering Needs Closed-Loop Benchmarks. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 813555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.-J.; Zeng, M.; Khoo, K.H.; Das, D.; Fong, X.; Fukami, S.; Li, S.; Zhao, W.; Parkin, S.S.; Piramanayagam, S.; et al. Spintronic devices for in-memory and neuromorphic computing—A review. Mater. Today 2023, 70, 193–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrows, C.H.; Barker, J.; Moore, T.A.; Moorsom, T. Neuromorphic computing with spintronics. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2024, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, D.V.; Dittmann, R.; Linares-Barranco, B.; Sebastian, A.; Le Gallo, M.; Redaelli, A.; Slesazeck, S.; Mikolajick, T.; Spiga, S.; Menzel, S. 2022 roadmap on neuromorphic computing and engineering. Neuromorph. Comput. Eng. 2022, 2, 022501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerging Research Devices/Beyond CMOS Chapter. In IEEE International Roadmap for Devices and Systems (IRDS); IRDS 2020 Edition; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: https://irds.ieee.org/ (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Semiconductor Research Corporation; Semiconductor Industry Association. Decadal Plan for Semiconductors; Full Report; 2021; Available online: https://www.src.org/ (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Lighton, J.R.B. Discontinuous gas exchange in insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1996, 41, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chown, S.L.; Gibbs, A.G.; Hetz, S.K.; Klok, C.J.; Lighton, J.R.B.; Marais, E. Discontinuous gas exchange: Consensus view. J. Exp. Biol. 2006, 209, 3719–3725. Available online: https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/499992 (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Hetz, S.K.; Bradley, T.J. Insects breathe discontinuously to avoid oxygen toxicity. Nature 2005, 433, 516–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chown, S.L. Discontinuous gas exchange: New perspectives. Funct. Ecol. 2011, 25, 1163–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, B. Keeping a cool head: Honeybee thermoregulation. Science 1979, 205, 1269–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, B. The Hot-Blooded Insects; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Stabentheiner, A.; Kovac, H.; Brodschneider, R. Honeybee colony thermoregulation. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e8967. [Google Scholar]

- May, M.L. Insects thermoregulation. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1979, 24, 313–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incropera, F.P.; DeWitt, D.P.; Bergman, T.L.; Lavine, A.S. Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer, 8th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- NIST CODATA. Stefan–Boltzmann Constant 5.670374419 × 10−8 W·m−2·K−4. Available online: https://physics.nist.gov/cgi-bin/cuu/Value?sigma (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Bosch Mobility. Modular Common-Rail Systems: Up to 8 Injections Per Cycle; Tech Note; Bosch Mobility: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Postrioti, L.; Buitoni, G.; Pesce, F.C.; Ciaravino, C. Zeuch method-based injection rate analysis of a Common-rail system operated with advanced injection strategies. Fuel 2014, 128, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.; Sorge, U.; Merola, S.; Irimescu, A.; La Villetta, M.; Rocco, V. Split injection in homogeneous-stratified gasoline direct injection engine for high combustion efficiency and low pollutans emission. Energy 2026, 117, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.; Mittica, A. Response of injector typologies to dwell-time variation. Appl. Energy 2016, 169, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.; Vassallo, A. Impact of common-rail systems on diesel engines. Energies 2025, 18, 5259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altshuler, D.L.; Dickson, W.B.; Vance, J.T.; Roberts, S.P.; Dickinson, M.H. High-frequency wing strokes in honeybee flight. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 18213–18218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedrick, T.L.; Miller, L.; Combes, S.A. Recent developments in the study of insect flight. Can. J. Zool. 2015, 93, 925–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pringle, J.W.S. Insect Flight; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1945. [Google Scholar]

- Syme, D.A. How to build fast muscles. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2002, 42, 762–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heywood, J.B. Internal Combustion Engine Fundamentals, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, CH, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.accessengineeringlibrary.com/content/book/9781260116106 (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Stone, R. Introduction to Internal Combustion Engines, 4th ed.; Palgrave: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Weis-Fogh, T. Energetics of hovering flight in hummingbirds and in Drosophila. J. Exp. Biol. 1972, 56, 79–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellington, C.P. Power and efficiency of insect flight muscle. J. Exp. Biol. 1985, 115, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.F.; Roberts, S.P. Flight respiration and energetics. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2000, 62, 179–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, B.N.; Jeong, H.; Kim, J.-H.; Park, J.-S.; Yang, C. Effects of Tip Clearance Size on Energy Performance and Pressure Fluctuation of a Tidal Propeller Turbine. Energies 2020, 13, 4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; Schluter, J.; Duan, F. Numerical study of the tip clearance flow in miniature compressors. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2019, 140, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teia, L. New Insight Into Aspect Ratio’s Effect on Secondary Losses of Turbine Blades. J. Turbomach. 2019, 141, 111004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelbagi, K.K. The effect of tip clearance size on pre-stall flow features of a transonic axial compressor by using throttle model. AIP Adv. 2023, 13, 115108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Energy. Capstone C30 (30 kW): Heat rate ≈13.8 MJ/kWh (26% LHV). Available online: https://www.capstoneturbine.com/ (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Barnard Microsystems (UAV Engines). Typical Rotor Ranges: 35k–120k rpm. Available online: https://barnardmicrosystems.com/product.html (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Garrett/Turbo Technical Notes. High-Speed Micro-Turbocharger Dynamics. Available online: https://www.garrettmotion.com/racing-and-performance/performance-catalog/ (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- JetCat. P250-PRO-S Turbojet: 13–20 s Start-To-Idle. 2019. Available online: https://www.jetcat.de/ (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- NXP. MPC5777C Engine-Control MCU: Dual 300 MHz + eTPU2 (96 ch), eMIOS (32 ch). Available online: https://www.nxp.com/products/MPC5777C (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Renesas. VC4 Domain Controller: A55 + RH850, Tens of kDMIPS. Available online: https://www.renesas.com/en/design-resources/boards-kits/vc4?srsltid=AfmBOoqGt8LKr4b92JsqHVVBYdO9-i8XrS01TXQh8Wy-sVLHN6Vp0qVq&part-status=Active (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- ISO 26262; Road Vehicles, Functional Safety. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Guo, L.; Zhang, N.; Simpson, J.H. Descending neurons coordinate anterior grooming behavior in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2022, 32, 823–833.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.; Yang, R.; Dorkenwald, S.; Matsliah, A.; Sterling, A.R.; Schlegel, P.; Yu, S.-C.; McKellar, C.E.; Costa, M.; Eichler, K.; et al. Network statistics of the whole-brain connectome of Drosophila. Nature 2024, 628, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 26262-1:2018; Road Vehicles—Functional Safety—Part 1: Vocabulary. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- IEC 61508-1:2010; Functional Safety of Electrical/Electronic/Programmable Electronic Safety-Related Systems—Part 1: General Requirements. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- ISO 13849-1:2023; Safety of Machinery—Safety-Related Parts of Control Systems—Part 1: General Principles for Design. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- MaBouDi, H.; Roper, M.; Guiraud, M.-G.; Juusola, M.; Chittka, L.; Marshall, J.A.R. A neuromorphic model of active vision shows how spatiotemporal encoding in lobula neurons can aid pattern recognition in bees. eLife 2025, 14, e89929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalgaty, T.; Vianello, E.; De Salvo, B.; Casas, J. Insect-inspired neuromorphic computing. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2018, 30, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanguas-Gil, A.; Madireddy, S. General Policy Mapping: Online Continual Reinforcement Learning Inspired on the Insect Brain. NeurIPS 2022 Workshop on Offline Reinforcement Learning, OpenReview. 2022. Available online: https://openreview.net/forum?id=G7IUNe224F (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Dickerson, A.E.; Reistetter, T.A.; Burhans, S.; Apple, K. Typical Brake Reaction Times Across the Life Span. Occup. Ther. Health Care 2016, 30, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: www.solbian.eu (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Lin, Z.; Hao, Q.; Zhao, B.; Hu, M.; Pei, G. Performance analysis of solar electric bikes. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2024, 132, 104261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.edgeai-trust.eu/ (accessed on 20 December 2025).

| Component | Description and Function | Edge-AI Analogy |

|---|---|---|

| Sensors (Fast & Complementary) | “Compound eyes (wide FOV, very high temporal resolution); Ocelli (simple light sensors for attitude); Halteres (gyroscopes sensing body rotation via Coriolis forces); Antennae/hairs (airflow and vibration).” | IMU/Gyroscopes + Global-shutter/Event Cameras + Airflow Sensors. |

| On-board Computation | “Optic lobe motion detectors (parallel ‘flow’ filters); Reflex pathways (e.g., ‘giant fiber’ escape route) prioritizing latency; Central complex (orientation); Mushroom bodies (learning).” | Fixed-function accelerators (for optic flow); Low-latency neuromorphic circuits (Reflex Tier). |

| Control Loops | Inner Loop (Stabilization): halteres + ocelli + wide-field motion allows wing adjustments in a few–tens of ms. Outer Loop (Goal): visual flow + odor/airflow allows course/target selection over longer windows. | Two-tier control: Reflex Tier (µs-ms) for stabilization; Policy Tier (ms-s) for planning. |

| Component | Description and Function | Edge-AI Analogy |

|---|---|---|

| Sensors | Compound eyes (incl. UV) + polarization sensitivity (sun compass); Ocelli (attitude); Antennae (olfaction + mechanosensation); Body hairs (micro-climate). | Polarization/UV Sensors; Odorimeters; Temperature/Contact Sensors. |

| On-board Computation | Optic flow odometry (distance estimation); Central complex (heading/compass and path integration); Mushroom bodies (associative learning); Task switching with minimal memory. | Visual Odometry (2D V-SLAM); Rule-based Policies (Heuristics); Local Learning (small neural networks). |

| Control Loops | Landing/Altitude: Maintain constant optic-flow expansion allows smooth landings without absolute altitude. Navigation: Polarization compass + optic-flow odometer + odor cues allows waypoint-style guidance. | “Non-linear control based on heuristics (e.g., adaptive Proportional-Integral-Derivative); Low-cost sensor fusion.” |

| Biological Tier | Engineering Tier | Typical Latency | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reflex | Reflex Tier (Neuromorphic Island) | Microseconds–Milliseconds (µs–ms) | “Stabilization, immediate reactions, low-level control (e.g., halteres control the steering of muscles).” |

| Policy | Policy Tier (RT Core/NPU) | Tens–Hundreds of Milliseconds (ms–s) | “Navigation, path planning, associative learning, goal selection (e.g., central complex → reflexes).” |

| Stage | Function (Example Stack) | WCET (µs) | Cumulative (µs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DVS/IMU exposure leads to interrupt assertion | 50 | 50 |

| 2 | DMA + time-stamp + spike encoding into Reflex Island | 150 | 200 |

| 3 | FF-SNN layer 1 (elementary motion detectors) | 800 | 1000 |

| 4 | STNO reservoir / RSNN update + readout | 1200 | 2200 |

| 5 | Reflex decision logic + watchdog comparators | 400 | 2600 |

| 6 | RT core arbitration, FOC current reference update | 400 | 3000 |

| 7 | PWM/timer update + gate-driver propagation | 400 | 3400 |

| Principle | Propulsion Requirement | Actionable Guidance |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency-controlled thrust (insect) | Wide-range thrust with minimal efficiency drift | Decouple: prime mover at island; thrust via motor frequency; buffer covers transients (Section 4.5 and Section 4.6) |

| Thermal governance | Bounded temps during bursts | Apply Section 4.3 ODE to compute burst time; enforce COOL-DOWN; shed Policy first |

| Instant-on Reflex | kHz stabilization independent of prime-mover state | MRAM Reflex Island near drivers/sensors; deadline monitors; DMA windows |

| Cold-start latency (miniturbine) | Usable thrust before light-off | Pre-warm plan; buffer-only takeoff/launch; soft-hand-over to turbine (Section 4.6) |

| Safety case | WCET & FFI | Fixed priorities; single-core pinning; one-way SPSC queues; watchdogs and logs |

| Thrust (N) | IFEVS Fuel (mL/min) | P400 Fuel (mL/min) | Fuel Ratio IFEVS/P400 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 80 | 143 | 391 | 0.37 |

| 120 | 215 | 507 | 0.42 |

| 160 | 287 | 623 | 0.46 |

| 200 | 358 | 739 | 0.48 |

| 240 | 430 | 855 | 0.50 |

| 280 | 502 | 971 | 0.52 |

| 320 | 573 | 1087 | 0.53 |

| 360 | 645 | 1203 | 0.54 |

| 400 | 717 | 1319 | 0.54 |

| 440 | 788 | — | — |

| 480 | 860 | — | — |

| 520 | 932 | — | — |

| 540 | 968 | — | — |

| Metric | IFEVS Thruster | State-of-the-Art Microturbine (Similar Thrust) |

|---|---|---|

| Thermal efficiency (core) | >40% before augmenter (fuel→jet power) | ~20–30% peak; sharp drop-off design |

| Thrust–load behavior | Flat efficiency from ~30 N → 600+ N after augmenter | Narrow island; poor partial-load BSFC |

| Fuel use @ ~400 N | ≈½ the fuel of miniturbine | Baseline |

| Fuel use @ ~50 N | ≈⅓ the fuel vs. turbine at low-load operation | Strong efficiency loss at low throttle |

| Exhaust temperature | ~150 °C at augmenter exit | ~500–1000 °C EGT; hot jet |

| Acoustic signature | ≤100 dB @ 3 m, subsonic ejector exit | Hot, often supersonic microjets; much louder |

| Response time | Near-instant; no spool-up | Spool-up/light-off delays (seconds) |

| Architecture/maintenance | No rotating parts; ~½ weight; low maintenance | High-speed rotor/bearings; higher maintenance load |

| Principle | Vehicle Requirement | Actionable Guidance |

|---|---|---|

| Reflex Tier (Fly) | Deterministic safety: stabilization, obstacle avoidance, traction/braking | Co-locate IMU/event camera + Reflex Island; run stabilization at 1–2 kHz; keep E-stop < 1 ms path; MRAM for instant-on |

| Policy Tier (Bee) | Robust navigation: VO, mapping, intent | Separate RT core/NPU at low priority; publish only goal states (speed corridors, waypoints) to Reflex |

| Thermal governance | Predictive performance: short high-power bursts | Implement Section 4.2 state machine; compute burst budgets via Section 4.3; log thermal debt and deadline misses |

| Spintronics | Low-power, event-driven perception | Use STNO reservoirs for vibration/flow/event-camera streams; MRAM synapses for reflex weights |

| Certification | Freedom-from-interference | Partition clocks/cores/memory; lock-free SPSC; WCET tables; watchdog + safety log |

| Stage | Function | Latency (ms) | Cumulative (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Camera exposure + readout/event aggregation | 5 | 5 |

| 2 | DMA + timestamp + spike/event encoding into Reflex Island | 2 | 7 |

| 3 | Looming-detection SNN inference (1–2 layers, few k neurons) | 4 | 11 |

| 4 | Reflex decision logic + hazard classification + queue write | 3 | 14 |

| 5 | Haptic/LED driver update + actuator rise time | 4 | 18 |

| Principle | Industrial Requirement | Actionable Guidance |

|---|---|---|

| Reflex isolation | Immediate safety (E-stop, limits, interlocks) | Put all safety loops on Reflex Island; pin core, fixed priorities; zero dynamic memory; deadline monitors |

| Two-tier split | Flexible tasks w/o jitter | Reflex: 1–2 kHz PID/LQR, commutators; Policy: vision, optimization, job scheduling; one-way queues |

| STNO reservoirs | High-bandwidth sensing | Inline temporal processing for accelerometers/vibration; predictive maintenance at the edge |

| Thermal governance | Shift-resilience | Use Section 4.3 budgets; enforce COOL-DOWN; rate-limit bursts; log thermals for maintenance |

| Certification | SIL 2–3/ISO 13849 | Prove freedom-from-interference; margin ≥ 30% on Reflex deadlines at hot corner; watchdog and safe states documented |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Perlo, P.; Dalmasso, M.; Biasiotto, M.; Penserini, D. Edge AI in Nature: Insect-Inspired Neuromorphic Reflex Islands for Safety-Critical Edge Systems. Symmetry 2026, 18, 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010175

Perlo P, Dalmasso M, Biasiotto M, Penserini D. Edge AI in Nature: Insect-Inspired Neuromorphic Reflex Islands for Safety-Critical Edge Systems. Symmetry. 2026; 18(1):175. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010175

Chicago/Turabian StylePerlo, Pietro, Marco Dalmasso, Marco Biasiotto, and Davide Penserini. 2026. "Edge AI in Nature: Insect-Inspired Neuromorphic Reflex Islands for Safety-Critical Edge Systems" Symmetry 18, no. 1: 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010175

APA StylePerlo, P., Dalmasso, M., Biasiotto, M., & Penserini, D. (2026). Edge AI in Nature: Insect-Inspired Neuromorphic Reflex Islands for Safety-Critical Edge Systems. Symmetry, 18(1), 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym18010175