Abstract

Detecting surface defects in forgings is crucial for ensuring the reliability of automotive components such as steering knuckles. In fluorescent magnetic particle inspection (FDMPI) images, normal forging surfaces generally exhibit locally symmetric texture patterns, whereas cracks and other flaws appear as locally asymmetric regions. Traditional FDMPI inspection relies on manual visual judgement, which is inefficient and error-prone. This paper introduces SDDNet, a symmetry-aware deep learning model for surface defect detection in FDMPI images. A dedicated FDMPI dataset is constructed and further expanded using a denoising diffusion probabilistic model (DDPM) to improve training robustness. To better separate symmetric background textures from asymmetric defect cues, SDDNet integrates a UPerNet-based segmentation layer for background suppression and a Scale-Variant Inception Module (SVIM) within an RTMDet framework for multi-scale feature extraction. Experiments show that SDDNet effectively suppresses background noise and significantly improves detection accuracy, achieving a mean average precision (mAP) of 45.5% on the FDMPI dataset, 19% higher than the baseline, and 71.5% mAP on the NEU-DET dataset, outperforming existing methods by up to 8.1%.

1. Introduction

Forgings are metal components widely used in manufacturing, for example in automotive knuckles. During the forging process, surface defects such as cracks may occur and compromise component reliability [1,2,3]. Because forging surfaces usually exhibit relatively uniform and repetitive texture patterns, they show a form of structural symmetry, while defect regions often manifest as local disruptions of this symmetry. Magnetic particle inspection (MPI) is a commonly used non-destructive testing method for surface defect detection (SDD) in ferromagnetic forgings [4]. In current industrial practice, MPI still relies mainly on manual observation of magnetic traces to identify defects. However, such manual inspection is inefficient, costly, and prone to human error [5].

Automated image processing methods have therefore been widely explored for SDD. Compared with traditional manual inspection, these methods offer higher efficiency, reduced labor cost, and improved accuracy [6,7,8]. Among them, deep learning has attracted particular attention due to its remarkable detection performance and scalability across different industrial applications [9,10,11]. With the availability of large-scale data, deep learning methods exhibit strong learning and generalization capabilities [12]. Because forging surfaces typically exhibit globally consistent and symmetric texture regularity, while surface defects manifest as locally asymmetric distortions, automated SDD can be viewed as distinguishing symmetric background patterns from asymmetric defect cues. However, When both characteristics are modeled within a single feature extraction pathway, dominant background responses often suppress weak defect features.This motivates a dual feature extraction strategy that explicitly decouples background texture modeling from defect-oriented feature learning. Image classification networks were among the first deep models used for industrial defect detection [13]. For example, in combination with smoothing windows, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) were applied in [14] to identify surface defects on rough concrete under challenging conditions. To achieve more efficient defect classification and localization, researchers subsequently employed object detection models [15,16,17]. In [18], for instance, a multi-level spatially refined detection network was proposed for surface defect detection of transmission line fasteners, addressing small targets and complex backgrounds.

Despite these advances in deep learning-based SDD, state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods still have several limitations. First, real industrial defect data are limited and time-consuming to collect, which hinders the development and deployment of practical models. Second, existing advanced anomaly detection datasets generally do not include forging MPI images, making it difficult to directly apply anomaly-based SDD algorithms in forging manufacturing scenarios. Third, most studies focus primarily on the representation of target defects, while paying insufficient attention to background regions with similar appearance. These background regions often introduce asymmetric patterns that disrupt the intrinsic symmetry of forging textures, thereby reducing detection accuracy in complex environments.

Many researchers have attempted to address these issues in the context of forging MPI. Yu et al. [19] found that forging MPI images share characteristics with remote sensing images, where features appear at multiple scales. They proposed EfficientNet-PSO, which improves detection accuracy using particle swarm optimization, but it mainly focuses on defect regions and neglects non-defect areas. Wu et al. [20] introduced a two-stage convolutional network for detecting cracks and localizing them in a 3D scene. Later, they proposed a 3D localization method for surface defects [21], using point cloud registration. However, non-defect regions remain underrepresented. Shi et al. [22] designed a lightweight depthwise separable convolutional network with knowledge distillation, achieving 96.5% accuracy at 35.25 FPS, but did not address background noise. Recent advancements have introduced more robust solutions. Gao et al. [23] proposed a cascade framework integrating YOLOv5 and segmentation to detect low-contrast defects, achieving 84.3% mAP. Zeng et al. [24] optimized DeepLabv3+ with MobileNetV2 and DenseASPP to enhance feature extraction for aviation ferromagnetic parts. Yang et al. [25] integrated MobileNetV3 with BiFPN in YOLOv5 to improve the speed–accuracy trade-off for industrial processes.

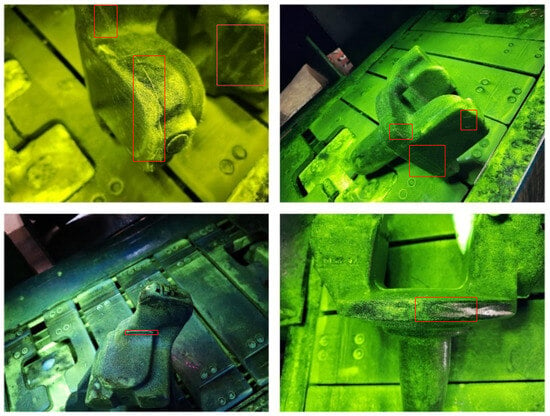

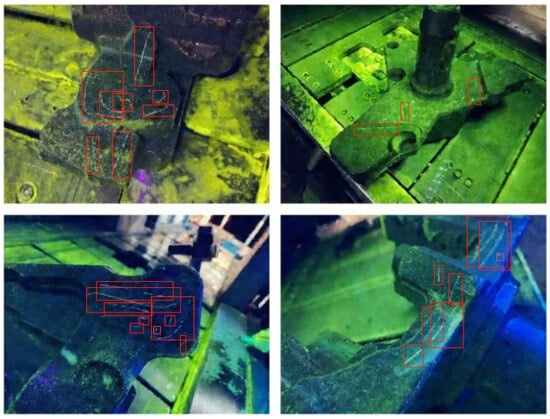

MPI images in Figure 1 show that the surface appearance of workpieces and forgings is highly comparable, with similar visual patterns for surface defects. Unlike conventional SDD tasks, forging MPI images are more influenced by background noise from the production environment [26,27], which existing research often overlooks. Yu et al. [19] noted that forging MPI images share similarities with remote sensing images, where critical features appear at multiple scales. Consequently, multi-scale feature extraction (MFE) has become crucial for effective SDD on forging MPI images, as it captures both high-level and fine-grained details for more accurate detection [28].

Figure 1.

Example images from the FDMPI dataset. In FDMPI images, workpieces typically exhibit similar features to forgings.The defects are marked in the red box.

To address these challenges and achieve efficient surface defect detection on forging MPI images, we propose the Surface Defect Detection Network (SDDNet), also referred to as a Seg-Det Dual-stage Network. This detection network is refined based on the RTMDet algorithm [29]. In SDDNet, a semantic segmentation layer, termed UperSegLayer, is inserted before the detection head to separate the forging surface from the background. Rather than performing standalone semantic segmentation, this layer serves as an explicit background modeling and suppression mechanism to reduce interference from production-line environments. By isolating the structurally symmetric surface region from asymmetric background interference, UperSegLayer improves detection robustness.The semantic segmentation layer is derived from the UPerNet segmentation head [30] and adapted for background modeling in forging surface defect detection. Furthermore, motivated by the observed similarity between forging MPI images and remote sensing images [19], Motivated by the similarity between forging MPI images and remote sensing images, we introduce the Scale-Variant Inception Module (SVIM), inspired by [31], which emphasizes scale-variant feature aggregation for multi-scale defect representation while maintaining a lightweight design. SVIM promotes the learning of scale-consistent symmetric feature structures, enabling the network to better capture informative patterns across different resolutions. SVIM is then combined with robust feature downsampling (RFD) [32] to form SVI-RFD, enabling scale-variant features to be preserved more effectively during downsampling. SVI-RFD preserves structural regularity during downsampling while highlighting asymmetric defect cues. SVIM is employed to improve the RTMDet backbone, resulting in a Scale-Driven Dual Backbone (SDD Backbone), while SVI-RFD is integrated into the RTMDet neck to construct a new Spatial-Depth Dual Neck (SDD Neck).

In summary, to achieve accurate and robust SDD on forging MPI images, this paper proposes SDDNet, which is designed to mitigate background noise interference in complex industrial environments. The main contributions of this work are as follows:

- The UPerNet segmentation algorithm is introduced into SDDNet as UperSegLayer, effectively suppressing background-induced asymmetry and improving detection accuracy by separating the forging surface from the production-line background.

- A new module, SVIM, is proposed. Integrating SVIM into the RTMDet backbone markedly enhances the network’s multi-scale feature extraction capability, supporting the representation of multi-scale symmetric feature structures while facilitating a lightweight design.

- SVIM is combined with RFD to construct SVI-RFD. Incorporating SVI-RFD into the RTMDet neck not only enables more efficient multi-scale feature extraction but also helps preserve symmetric feature patterns during downsampling, thereby enhancing robustness in complex environments.

In the remainder of this paper, Section 2 presents the materials and methods, including the proposed SDDNet architecture, the datasets, implementation details, and evaluation metrics. Section 3 reports the experimental results from our ablation and comparative studies on the FDMPI and NEU-DET datasets. Following this, Section 4 discusses these findings in detail. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper and outlines potential avenues for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Proposed Method

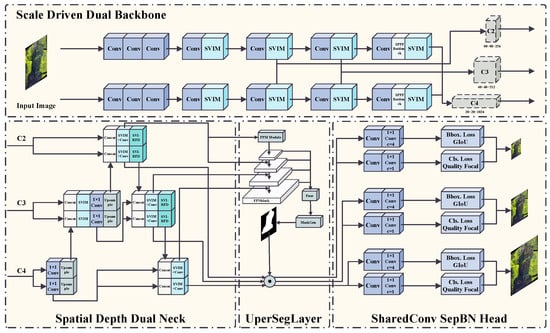

To address the specific characteristics of forging surface defect detection (SDD) images in FDMPI, we propose SDDNet, a symmetry-aware two-stage detector based on a dual feature-extraction network. This design explicitly separates the modeling of approximately symmetric background textures from the learning of locally asymmetric defect patterns, thereby reducing background interference and enhancing defect discriminability. As illus-trated in Figure 2, SDDNet consists of a dual backbone network (dual-SVIM), a dual neck network (dual-PAFPN), a segmentation layer (UperSegLayer), and a detection head.

Figure 2.

Structural diagram of SDDNet. SDDNet primarily comprises dual-SVIM, dual-PAFPN, UperSegLayer, and detection heads.

2.1.1. UperSegLayer

As discussed in Section 1 and Section 2, existing research on forging surface defect detection often overlooks the influence of background regions whose texture patterns closely resemble those of true defect areas. These background patterns introduce locally asymmetric noise into otherwise approximately symmetric forging surfaces, thereby affecting detection accuracy. To address this issue, we incorporate a segmentation layer into the detection pipeline to explicitly separate the forging region from the background.

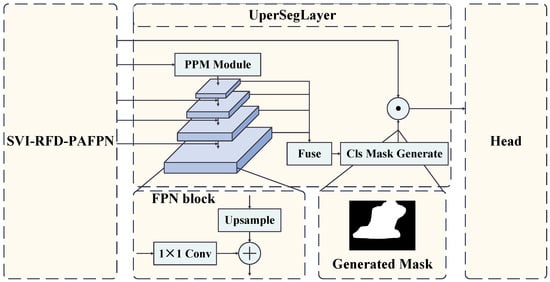

To achieve this, we adapt the classical UPerNet semantic segmentation architecture [4] and construct a lightweight segmentation module, termed the UperSegLayer. This module is integrated into SDDNet to extract forging regions from FDMPI images. Different from conventional semantic segmentation, UperSegLayer is used as an auxiliary module for background modeling to guide feature refinement for defect detection. Its backbone and neck operate independently of the detection head, and the overall structure is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Structural diagram of UperSegLayer. After passing through the Feature Pyramid Network and the feature fusion module, it generates the forging shape mask, which is then element-wise multiplied with the original feature map to produce the final output feature map.

To ensure that the detection model fully learns global feature representations during training, we adopt a decoupled training strategy in which the segmentation module and detection module are trained separately. During the training stage, the detection network bypasses the UperSegLayer and sends the neck output directly to the detection head. However, during validation and testing, the output feature maps from the neck are first fed into the UperSegLayer. The segmentation model, trained as an upstream task, predicts a forging-region mask that suppresses background-induced asymmetric noise. The mask is then element-wise multiplied with the original feature map to obtain the final refined representation.

Formally, given input feature maps , the Pyramid Pooling Module (PPM) operates as follows:

where denotes convolution, denotes pooling with scales , represents the processed pooled feature map, denotes convolution, and denotes channel-wise concatenation. is the final output of the PPM. The detailed pipeline is described in (1).

The outputs are subsequently fused within the Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) as:

where denotes the fused feature map of the i-th level, and is the final output feature map from the FPN module. The complete FPN fusion process is shown in (2).

where denotes the segmentation prediction, denotes pixel classification, and represents the refined feature map obtained by masking the input feature map F. The operation is described in (3).

Through this process, the UperSegLayer effectively suppresses asymmetric background noise and restores the intrinsic structural symmetry of forging surface regions, thereby providing cleaner feature representations for downstream defect detection.

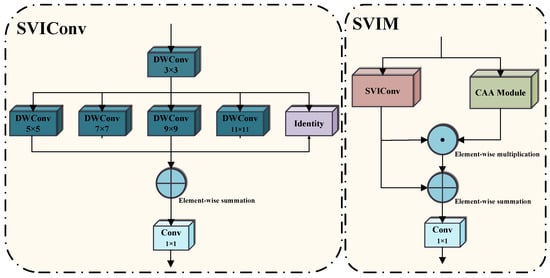

2.1.2. SVIM

In [19], it was observed that surface cracks in forgings exhibit critical features across multiple spatial scales, which makes multi-scale feature extraction (MFE) indispensable for accurate defect detection. Traditionally, MFE is implemented using large-kernel convolutions and dilated convolutions. However, for images with fine local characteristics and approximately symmetric background textures, large-kernel convolutions may fail to capture subtle local asymmetries, while dilated convolutions can produce unsmooth responses, degrading the quality of extracted features. To address these issues, we design a novel Scale-Variant Inception Convolution (SVIConv) and integrate it with the Context-Anchored Attention (CAA) module proposed by Cai et al. [31], forming the Scale-Variant Inception Module (SVIM). The SVIConv employs parallel depth-wise convolution kernels of different sizes to jointly capture local and global contextual information, thus providing scale-aware feature extraction suitable for both symmetric textures and locally asymmetric defect patterns. The CAA module models long-range relationships via global average pooling and 1D strip convolutions, enhancing the feature representation in the central region. In combination, SVIConv and CAA improve the adaptive extraction of multi-scale features for forging defects.

The SVIConv adopts an inception-style structure composed of a small-kernel convolution branch for local feature extraction and a set of parallel depth-wise convolutions (DWConv) for capturing contextual information at multiple scales. A schematic illustration of the SVIConv and the overall SVIM structure is provided in Figure 4. Specifically, for SVIM at stage l, given an input feature map , the SVIConv can be formulated as:

where denotes the local features extracted by convolution, and represents the contextual features extracted by the m-th convolution. Following [31], and . The fused features are integrated through a convolution to represent inter-channel dependencies, as given by:

where denotes the output of SVIConv. This design enables SVIConv to capture broad contextual information while maintaining local texture integrity.

Figure 4.

Architecture of SVIConv and SVIM.

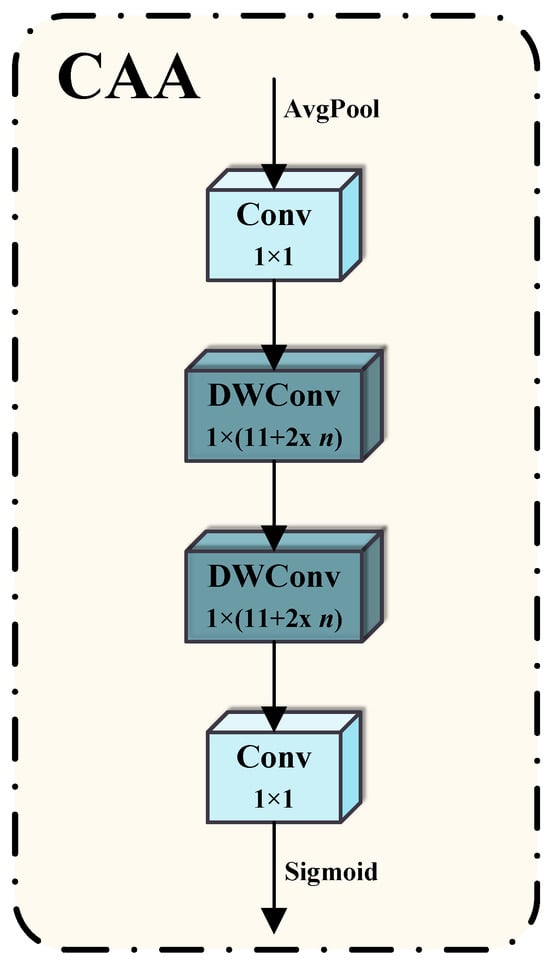

Meanwhile, within the SVIM, the feature maps are further enhanced for multi-scale key feature extraction through the CAA module. The CAA strengthens central features while emphasizing contextual relationships among globally distant pixels, thereby improving the module’s ability to extract scale-dependent key features across different resolutions. A schematic illustration of the CAA structure is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Structure of the CAA module.

Specifically, for the l-th stage of SVIM in the backbone with an input feature map , the processing within the CAA module is defined as:

where denotes average pooling and represents a convolution. Next, the CAA module approximates the effect of a large-kernel depth-wise convolution through two sequential depth-wise strip convolutions, expressed as:

Through the use of two 1D depth-wise convolutions, the CAA module effectively achieves a receptive field equivalent to that of a large-kernel depth-wise convolution while preserving fine structural details. This improves the extraction of elongated and slender features, which is particularly advantageous for identifying surface crack patterns—typical asymmetric structures embedded within otherwise symmetric forging textures. Following the findings of Cai et al. [31], the kernel width in this work is set to for the l-th stage.

Finally, within the CAA module, a convolution followed by a Sigmoid activation function is applied to constrain the output values to the range , yielding the final attention map , i.e.,

The final output of the SVIM stage integrates SVIConv and CAA as:

where ⊙ denotes element-wise multiplication and ⊕ denotes element-wise addition. Through this attention-guided fusion, SVIM adaptively emphasizes multi-scale features that are most relevant to forging surface cracks, while suppressing less informative responses from approximately symmetric background textures. As a result, the enhanced network equipped with SVIM exhibits stronger cross-scale feature extraction capability and achieves more accurate feature representation for slender crack-like defects in forgings, thereby improving the overall precision of defect detection.

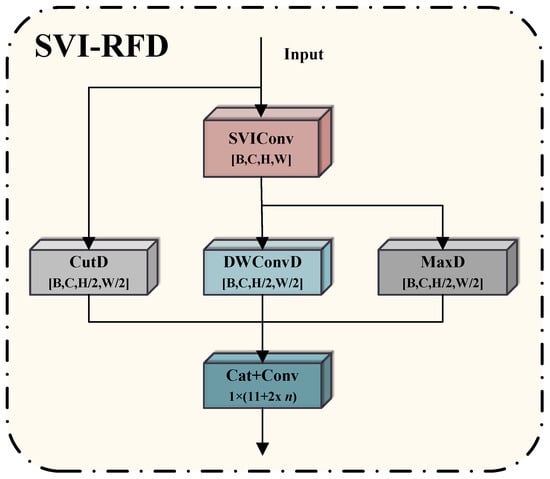

2.1.3. SVI-RFD

Aiming at remote sensing images characterized by low resolution, small targets, and limited feature information, the work in [32] proposed a robust feature downsampling (RFD) module that integrates multiple downsampling strategies to improve feature extraction. The effectiveness of this module was demonstrated experimentally. As highlighted in [22], certain defects in FDMPI images exhibit similar characteristics—low resolution, small spatial extent, and limited distinguishable features—making their multi-scale representation analogous to that of remote sensing imagery. Consequently, RFD is well suited for surface defect detection in FDMPI images.

To further address the multi-scale feature extraction (MFE) challenges present in FDMPI data, we integrate the SVIM concept with RFD and develop the SVI-RFD module, which enhances both MFE capability and feature robustness during downsampling, as shown in Figure 6. Specifically, SVI-RFD follows the core design philosophy of RFD by first preserving the original feature-map information through cut downsampling (CutD) while simultaneously enriching multi-scale representations via the SVIConv. For the feature maps processed by SVIConv, SVI-RFD subsequently applies depth-wise convolution downsampling (DWConvD) to capture and fuse local feature cues. Finally, Max Pooling downsampling (MaxD) is performed to prevent the loss of key structural details, particularly those associated with small or slender defect regions. Through this combination of CutD, SVIConv-based enhancement, DWConvD fusion, and MaxD preservation, the SVI-RFD module effectively strengthens cross-scale feature robustness, improves the representation of asymmetric crack patterns, and maintains the stability of symmetric background textures.

Figure 6.

Architecture of the proposed SVI-RFD module.

2.2. The FDMPI Dataset

The original FDMPI dataset consists of 325 images containing 415 defect samples, all collected from the flaw detection process of an actual forging production line. To enhance the robustness of our models and better simulate real-world conditions, we employed a data augmentation technique for deep saliency prediction, as proposed by Bahar Aydemir et al. [33]. Following this augmentation, the dataset was expanded to 4622 images, encompassing 15,492 defect samples. The augmented dataset was then split into a training set of 3206 images (11,700 samples) and a validation/test set of 1416 images (3792 samples). All samples in the dataset are labeled as defective, as the industrial inspection task focuses on defective-versus-non-defective identification rather than fine-grained defect categorization.

Additionally, the dataset includes 1200 segmented forging images with corresponding annotations, which are used for training upstream models in forging segmentation tasks. Examples from the FDMPI dataset are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Examples of defect images from the FDMPI dataset generated using the DDPM-based augmentation strategy. The application of DDPM increases the number of defective samples and introduces diverse photometric variations that resemble real forging-surface appearances.

Prior studies [19,20,21,22] have made significant strides in detecting cracks in forgings. However, their robustness in real-world applications remains limited, primarily due to insufficient consideration of the complexities inherent in actual production environments. Traditional data augmentation techniques such as rotation and cropping can diversify the dataset, but they may also alter the intrinsic composition of the images, potentially affecting the saliency of defects.

To address these limitations, we devised a specialized image processing and enhancement procedure (see Algorithm 1), inspired by the methodology of Bahar Aydemir et al. [33]. This approach focuses on learning both high-level and low-level features of images, including color, contrast, luminance, and semantic attributes. By incorporating attention-guided mechanisms, the augmentation selectively adjusts photometric characteristics while preserving defect-relevant regions. This ensures that the augmented images closely resemble real production scenarios, enhancing the accuracy and robustness of models in both forging-defect detection and segmentation tasks.

| Algorithm 1 Defect Detection Sample Generation using Latent Diffusion. |

|

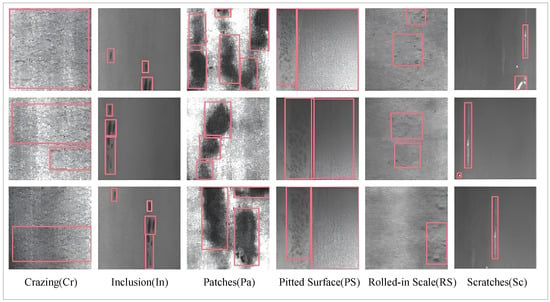

2.3. NEU-DET Dataset

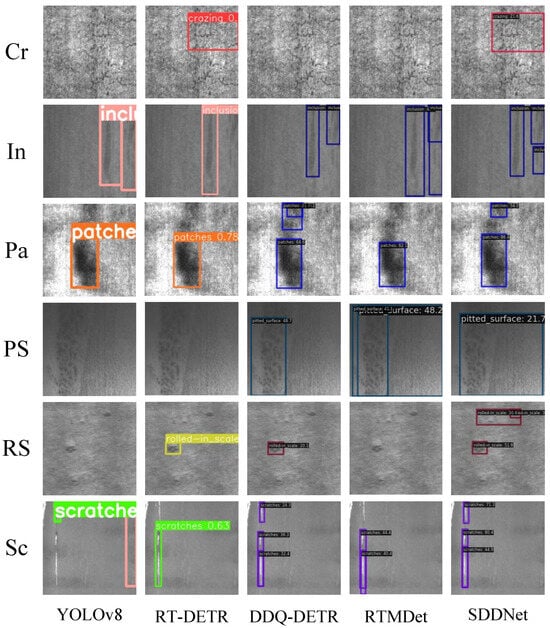

The NEU-DET dataset, established by Song et al. [34], consists of 1800 images containing six types of defects: Cracks (Cr), Inclusions (In), Patches (Pa), Pitted Surface (PS), Rolled-in Scale (RS), and Scratches (Sc). The dataset has been widely used in surface defect detection tasks, and we utilize it to demonstrate the generalizability of our proposed SDDNet method. Some example images from the NEU-DET dataset are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Example images of NEU-DET dataset.

2.4. Hardware and Software

The experiments in this study were conducted on a system equipped with an Intel Core i5-13400F processor (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA), paired with a single NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4070 Ti graphics card (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA). GPU for accelerated computation. The software environment was built using Python 3.10, with CUDA 11.7 enabling GPU-based operations. The proposed SDDNet model was trained and tested within this setup to evaluate its performance on surface defect detection tasks.

Referring to the original RTMDet training configuration from [29], the model was trained on input images of size , with a batch size of 4, over 300 epochs. The initial learning rate was set to 0.0004, and the AdamW optimizer was employed for training. Data augmentation techniques applied during training included Mosaic and MixUp for the first 280 epochs, with caching enabled, while large-scale jittering was employed in the last 20 epochs.

2.5. Evaluation Metrics

For both NEU-DET and FDMPI, the mean accuracy percentage () is used as the evaluation metric here, defined by the following formula:

where (True Positive) is a positive example correctly predicted as positive; (False Negative) is a positive example incorrectly predicted as negative; and (False Positive) is a negative example incorrectly predicted as positive. represents the individual category accuracy. is the mean accuracy across all categories, and c is the number of categories.

3. Results

3.1. Ablation Experiments

To evaluate the effectiveness and generalizability of SDDNet, we conducted a series of experiments on the FDMPI dataset to assess the impact of incorporating various components. The results of these experiments are summarized in Table 1, where “Baseline” refers to the RTMDet network. Four key components were considered in the experiments: Baseline, SVIM, SVI-RFD, and UperSegLayer.

Table 1.

Ablation experimental results on FDMP of SDDNet.

Initially, we introduced the SVIM module as the backbone network. SVIM enhances the backbone’s multi-scale feature extraction capability by enabling more effective representation of defect patterns at different spatial resolutions. As shown in Table 1, this improvement is particularly evident for small- and medium-sized defects, as reflected by the gains in and , indicating that SVIM enhances scale-sensitive feature representation.

Subsequently, we added the SVI-RFD module to the network. SVI-RFD improves feature stability during downsampling by preserving fine-grained spatial details that are critical for defect detection, especially for small targets. As shown in the third row of Table 1, adding SVI-RFD further improved the mAP compared to the baseline, particularly for small targets, without negatively affecting parameter efficiency. This demonstrates the module’s effectiveness in preserving fine-grained features under aggressive downsampling, which is critical in complex multi-scale contexts. Furthermore, the comparison in the fifth row of Table 1 illustrates that combining SVIM and SVI-RFD minimizes the network’s parameter count, underscoring their advantages in creating a more lightweight model.

Next, we incorporated the UperSegLayer to separate the forging region from the background, effectively reducing background noise during detection. The inclusion of UperSegLayer resulted in a significant increase in mAP, especially in the AP75 and large target detection (APl) metrics, as shown in the fourth row of Table 1. Although UperSegLayer introduces additional parameters, the resulting improvement in high-IoU localization accuracy under complex backgrounds justifies this trade-off.

Finally, when SVIM, SVI-RFD, and UperSegLayer were combined, the network achieved its highest mAP value of 45.5%, with AP50 and AP75 improving to 85.2% and 42.9%, respectively, as shown in the last row of Table 1. This comprehensive integration of the three modules enables SDDNet to achieve the best performance in the forging surface defect detection task, particularly when handling images with complex backgrounds. Compared to the baseline network, the experimental results clearly demonstrate the effectiveness and superiority of the proposed SDDNet.

3.2. Comparative Experiments

In this subsection, we evaluate the proposed SDDNet through comparative experiments on the FDMPI and NEU-DET datasets. SDDNet is compared with representative state-of-the-art detectors, including Double-Head R-CNN, Dynamic R-CNN, YOLOX-l, YOLOv8-l, YOLOv11-l, DETR, DINO, DDQ-DETR, RT-DETR, and RTMDet. All methods were implemented based on official open-source repositories or widely adopted public implementations and evaluated under a unified protocol whenever possible, including identical input resolution, dataset splits, and evaluation metrics. For models with architecture-specific training requirements, the default or recommended settings reported in the original papers were followed. The experimental results are summarized in Table 2 and Table 3, while the comparative detection outcomes are visualized in Figure 9 and Figure 10.

Table 2.

Comparative Experimental Results On FDMP.

Table 3.

Comparative Experimental Results On NEU-DET.

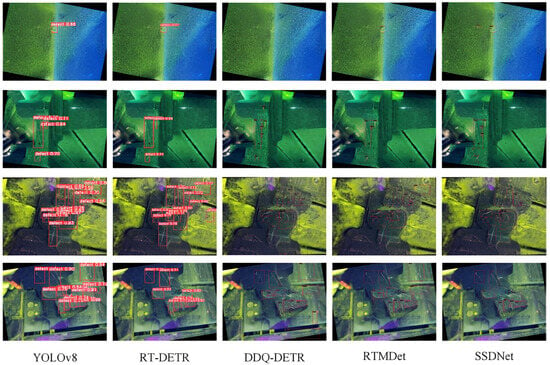

Figure 9.

Comparison of detection effects of some methods on FDMPI.

Figure 10.

Comparison of detection results of selected methods on NEU-DET.

3.2.1. Comparisons on FDMPI

The overall mAP, shown in the last row of Table 2, demonstrates that SDDNet (45.5%) outperforms other methods by approximately 5–10%, highlighting its superior ability in multi-scale feature extraction (MFE) and background noise suppression, particularly in complex surface defect detection (SDD) tasks. Specifically, SDDNet achieves higher AP50 (85.2%) and AP75 (42.9%) scores compared to other methods, suggesting more accurate localization under strict IoU thresholds in complex forging surfaces. This performance gain can be attributed to multiple factors, including the enhanced multi-scale representation provided by the SVIM backbone and the background suppression introduced by the UperSegLayer, which together improve detection robustness under complex surface conditions, allowing the model to excel in both wide-range and high-precision defect detection.

In small-target detection (), SDDNet achieves 36.5%, outperforming YOLOX-l, RTMDet, and YOLOv11-l, which indicates a stronger capability for preserving fine-grained defect features. This improvement is mainly attributed to the SVI-RFD module, which enhances feature retention during downsampling and improves robustness for detecting small-scale defects. Moreover, SDDNet performs well in medium- and large-target detection ( and ), achieving 45.6% and 51.4%, respectively. This indicates strong detection accuracy and stability across different defect sizes, demonstrating the model’s superior generalization ability.

As shown in Figure 9, SDDNet achieves higher accuracy and fewer missed detections for fine defects compared to other methods, as evidenced by the first and second rows of images. In the third and fourth rows, where background workpieces exhibit defects similar to the target defects, SDDNet exhibits a superior ability to exclude background noise and effectively detect forging defects. Although SDDNet has a higher parameter count (73.8 M) than lightweight detectors such as RT-DETR and YOLOv11-l (as shown in the last row of Table 2), the substantial accuracy improvements justify this increase. In terms of efficiency, SDDNet runs at 50.3 FPS on the FDMPI dataset, which is sufficient for practical industrial inspection while providing notably higher detection accuracy than most compared methods.

In conclusion, the performance of SDDNet on the FDMPI dataset confirms its superiority and generalization ability in complex defect detection tasks, particularly in terms of MFE and background noise suppression.

3.2.2. Comparisons on NEU-DET

To further validate the effectiveness and generalization ability of SDDNet in diverse surface-defect detection (SDD) scenarios, we conducted comparative experiments on the NEU-DET dataset using several mainstream detection methods. Since the UperSegLayer is designed for background suppression in FDMPI images, it was excluded from SDDNet in this experiment, allowing evaluation of the core detection backbone under a different data distribution.

As shown in the last row of Table 3, SDDNet achieved an mAP of 71.5% on NEU-DET, significantly outperforming other methods such as YOLOv8-l (63.4%), YOLOv11-l (61.7%) and RTMDet (64.6%), demonstrating strong generalization ability. Notably, although YOLOv11-l exhibits high inference speed, its detection accuracy remains lower than that of SDDNet across most defect categories. Specifically, SDDNet achieved AP values of 35.7% and 60.0% for Cr and Rs defect detection, surpassing methods like RT-DETR (33.6%) and DDQ-DETR (28.8%). This improvement is attributed to the SVIM backbone’s advantages in multi-scale feature extraction (MFE) and complex texture analysis. SDDNet also performed well in detecting In, Pa, and Sc defects, achieving AP values of 75.7%, 89.3%, and 78.7%, respectively, which indicates higher accuracy and stability compared to methods like DETR and Dynamic R-CNN.

Although its performance on Ps defects is comparable to DINO (89.8% vs. 94.9%), SDDNet demonstrates more balanced performance across all defect categories. Notably, without the UperSegLayer, SDDNet contains only 26.4 M parameters, the smallest among all compared methods.In this lightweight configuration, SDDNet achieves an inference speed of 67.7 FPS, indicating a good balance between accuracy and computational efficiency. As shown in Figure 10, SDDNet provides more accurate detection of In, Pa, Ps, and Sc defects than other methods and performs particularly well on Cr and Rs defects, which are more challenging for other models.

4. Discussion

In this study, we proposed the SDDNet model for surface defect detection (SDD) in forging images. The experimental results demonstrates that SDDNet demonstrates superior performance compared to several representative and recent methods, particularly in multi-scale feature extraction (MFE) and background noise suppression. The findings of our experiments on the FDMPI and NEU-DET datasets illustrate the effectiveness and generalization ability of SDDNet in complex SDD tasks.

One of the key contributions of SDDNet is the integration of the Scale-Variant Inception Module (SVIM), which enhances the model’s capability to capture defects at multiple scales. This is consistent with prior studies, such as [19,33], where multi-scale feature extraction played a critical role in improving defect detection. Our results show that SVIM effectively addresses the challenges posed by small- and medium-sized defects, as evidenced by the improved performance in mAP, particularly for small target detection ().

Additionally, the incorporation of the Robust Feature Downsampling (SVI-RFD) module demonstrated significant improvements in feature map robustness and fine-grained feature retention during downsampling. This aligns with the findings in [32], where downsampling strategies were shown to improve detection accuracy in low-resolution or small-target scenarios. The ability of SVI-RFD to enhance the model’s robustness in such challenging contexts further solidifies its value in practical defect detection tasks.

The UperSegLayer, which was introduced to suppress background noise by separating the forging region from the background, also played a critical role in improving performance, particularly in large target detection () and scenarios involving complex background noise. While the inclusion of UperSegLayer increased the number of parameters, its impact on detection accuracy, especially in images with complex backgrounds, justifies its inclusion. This result is in line with previous work on semantic segmentation [33], where background noise suppression was shown to improve detection precision.

Our findings also demonstrate the superior generalization ability of SDDNet when compared to other state-of-the-art methods, such as YOLOv8-l and RTMDet, on both the FDMPI and NEU-DET datasets. This highlights the potential of SDDNet for broader adoption in real-world applications where background noise and multi-scale defects are common challenges.

Despite these successes, there are areas for further improvement. One potential avenue for future research is exploring the combination of SDDNet with advanced anomaly detection techniques, such as generative models or attention-based mechanisms, to enhance its ability to detect previously unseen defect types. Additionally, the performance of SDDNet could be further optimized by exploring other advanced network architectures or loss functions tailored to SDD tasks.

In conclusion, the SDDNet model has proven to be an effective and efficient solution for surface defect detection in forging images, showing promising results across multiple datasets. Future work will focus on further enhancing the model’s accuracy and applicability to a wider range of industrial defect detection tasks.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we proposed SDDNet for surface defect detection (SDD) in forging images, with a particular focus on the unique characteristics of FDMPI images. The key contributions of this study are as follows:

- To address background noise in FDMPI images, we integrated the UPerNet algorithm as the UperSegLayer for background segmentation, effectively reducing noise interference and enhancing detection accuracy.

- We introduced the Scale-Variant Inception Module (SVIM), which, when incorporated into the RTMDet backbone, significantly enhances the network’s multi-scale feature extraction (MFE) capability and facilitates a lightweight design.

- We combined SVIM with Robust Feature Downsampling (RFD) to create the SVI-RFD module. Integrating SVI-RFD into the RTMDet neck not only improves MFE efficiency but also enhances the robustness of the downsampling process.

Our experiments demonstrate that integrating a segmentation network into the detection pipeline increases computational cost but substantially improves detection accuracy. The enhancement of MFE and the robustness of the downsampling module also result in a significant boost in SDD accuracy for forgings. In this research, we integrated a classical segmentation algorithm to verify the effectiveness of background segmentation without focusing on computational optimization.

In future work, we plan to refine the background segmentation module to reduce computational overhead and achieve higher detection efficiency, thereby enhancing the overall performance and practicality of SDDNet for industrial applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.W. and Y.H.; methodology, S.W.; software, S.W.; validation, S.W., D.G. and Z.X.; formal analysis, S.W. and B.-W.M.; investigation, S.W., T.X. and Z.X.; resources, D.G.; data curation, T.X. and Z.X.; writing—original draft preparation, S.W.; writing—review and editing, Y.H. and B.-W.M.; visualization, S.W. and Z.X.; supervision, Y.H.; project administration, Y.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Nantong Municipality under grant number JC2023023.

Data Availability Statement

The FDMPI dataset used in this study is publicly available at: https://github.com/Prime-Rogue/FDMPI-Dataset.git, accessed on 17 April 2025. The NEU-DET dataset is publicly accessible and can be downloaded from its official repository: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1qrdZlaDi272eA79b0uCwwqPrm2Q_WI3k/view, accessed on 6 April 2025. No additional data were generated in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the colleagues who provided general technical advice during the early stages of dataset preparation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FDMPI | Forging Defect Magnetic Particle Inspection |

| SDD | Surface Defect Detection |

| SVIM | Scale-Variant Inception Module |

| MFE | Multi-Scale Feature Extraction |

| AP | Average Precision |

| mAP | Mean Average Precision |

| RTMDet | Real-Time Multi-scale Detection |

| YOLOv8 | You Only Look Once Version 8 |

| DETR | Detection Transformer |

| DINO | A self-supervised approach to transformer networks |

References

- Ameri, R.; Hsu, C.C.; Band, S.S. A systematic review of deep learning approaches for surface defect detection in industrial applications. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 130, 107717. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q.; Dong, K.; Qin, X.; Hu, Z.; Xiong, X. Magnetic particle inspection: Status, advances, and challenges—Demands for automatic non-destructive testing. NDT E Int. 2024, 143, 103030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Wu, T.; Xia, Z.; He, B.; Kong, L.B.; Su, H. Research progress in deep learning for ceramics surface defect detection. Measurement 2025, 242, 115956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakunov, A.; Korolev, A.; Kudryavtsev, D.; Petrov, V. A set for magnetic fluorescent-penetrant inspection. Russ. J. Nondestruct. Test. 2005, 41, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z. Review of non-destructive testing methods for defect detection of ceramics. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 4389–4397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S.; Yang, J.; Zhong, Z. A review on industrial surface defect detection based on deep learning technology. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Machine Learning and Machine Intelligence, Hangzhou, China, 18–20 September 2020; pp. 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Su, J.; Luo, Q.; Yang, C.; Gui, W.; Silvén, O.; Liu, L. PMSA-DyTr: Prior-modulated and semantic-aligned dynamic transformer for strip steel defect detection. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, 20, 6684–6695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Wu, M.; Qin, X.; Hua, L. Machine vision driven magnetic particle inspection technology: Principles, applications and trends. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Du, W.; Xu, G.; Sun, Y.; Shen, H. Automated crack detection of train rivets using fluorescent magnetic particle inspection and instance segmentation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 10666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lugin, S.; Müller, D.; Finckbohner, M.; Netzelmann, U. Automated surface defect detection in forged parts by inductively excited thermography and magnetic particle inspection. Quant. Infrared Thermogr. J. 2025, 22, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Luo, W.; Wang, J.; Liu, D.; Ziaie, B.; Velay, X. Study on fold formation mechanism and process optimization in multi-directional die forged valve bodies. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0337844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, T.; Tobias, M. Machine learning and deep learning based predictive quality in manufacturing: A systematic review. J. Intell. Manuf. 2022, 33, 1879–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberironaghi, A.; Ren, J.; El-Gindy, M. Defect detection methods for industrial products using deep learning techniques: A review. Algorithms 2023, 16, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, Y.J.; Choi, W.; Büyüköztürk, O. Deep learning-based crack damage detection using convolutional neural networks. Comput. Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2017, 32, 361–378. [Google Scholar]

- Momot, A.; Yakotiuk, V. Modern Trends in Automation of Magnetic Particle Inspection. 2025. Available online: https://ela.kpi.ua/server/api/core/bitstreams/f9d2fc2d-3dbb-4483-9704-c6d765fb5fbc/content (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Shen, K.; Zhou, X.; Liu, Z. MINet: Multiscale interactive network for real-time salient object detection of strip steel surface defects. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, 20, 7842–7852. [Google Scholar]

- Li, A.; Yang, Y.; Wu, S.; Wu, T.V.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, W.; Zhang, H. Study on non-destructive detection technology of water content and defects in construction materials based on transmission terahertz system. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 104, 112452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Peng, W.; Yi, J.; Tao, Z.; Zhang, H.; Liu, C. MSRN: Multilevel spatial refinement network for transmission line fastener defect detection. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, 20, 11610–11621. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, T.; Chen, W.; Gao, J.; Hua, P. Intelligent detection method of forgings defects based on improved EfficientNet and memetic algorithm. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 79553–79563. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q.; Qin, X.; Dong, K.; Shi, A.; Hu, Z. A learning-based crack defect detection and 3D localization framework for automated fluorescent magnetic particle inspection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 214, 118966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Hu, Z.; Qin, X.; Huang, B.; Dong, K.; Shi, A. Surface defects 3D localization for fluorescent magnetic particle inspection via regional reconstruction and partial-in-complete point clouds registration. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 122225. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, A.; Wu, Q.; Qin, X.; Mao, Z.; Wu, M. Lightweight detector based on knowledge distillation for magnetic particle inspection of forgings. NDT E Int. 2024, 143, 103052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Wu, Q.; Wu, M.; Qin, X.; Hua, L. Detection and localization system for surface defects of automotive forgings based on machine vision. J. Intell. Manuf. 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Zhang, S.; Wang, P.; Li, Z.; Hu, Y.; Xie, T. Defect detection algorithm for magnetic particle inspection of aviation ferromagnetic parts based on improved DeepLabv3+. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2023, 34, 065401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zuo, J.; Li, L.; Wang, X.; Yin, Z.; Ding, X. Crack identification method for magnetic particle inspection of bearing rings based on improved YOLOv5. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2024, 35, 065405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Q.; Qin, J. A light deformable multi-scale defect detection model for irregular small defects with complex background. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 175, 109565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, X.; Dong, Z. Car brake disc surface defect detection based on improved YOLOv5. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 68601–68610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Yu, X.; Gao, X.; Li, K.; Shen, S. Recent advances in conventional and deep learning-based depth completion: A survey. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 35, 3395–3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, C.; Zhang, W.; Huang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Chen, K. Rtmdet: An empirical study of designing real-time object detectors. arXiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, B.; Jiang, Y.; Sun, J. Unified perceptual parsing for scene understanding. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 418–434. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, X.; Lai, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Sun, Z.; Yao, Y. Poly kernel inception network for remote sensing detection. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 27706–27716. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, W.; Chen, S.B.; Tang, J.; Ding, C.H.; Luo, B. A robust feature downsampling module for remote-sensing visual tasks. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 4404312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papakipos, Z.; Bitton, J. Augly: Data augmentations for adversarial robustness. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–20 June 2022; pp. 156–163. [Google Scholar]

- Song, K.; Yan, Y. A noise robust method based on completed local binary patterns for hot-rolled steel strip surface defects. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2013, 285, 858–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.