Abstract

We present the first step toward the quantum computing (QC) formulation of the electron nuclear dynamics (END) method within the variational quantum simulator (VQS) scheme: END/QC/VQS. END is a time-dependent, variational, on-the-flight, and non-adiabatic method to simulate chemical reactions. END represents nuclei with frozen Gaussian wave packets and electrons with a single-determinantal state in the Thouless non-unitary representation. Within the hybrid quantum/classical VQS, END/QC/VQS currently evaluates the metric matrix M and gradient vector V of the symplectic END/QC equations on the QC software development kit QISKIT, and calculates basis function integrals and time evolution on a classical computer. To adapt END to QC, we substitute the Thouless non-unitary representation with Fukutome unitary representation. We derive the first END/QC/VQS version for pure electronic dynamics in multielectron chemical models consisting of two-electron units with fixed nuclei. Therein, Fukutome unitary matrices factorize into triads of one-qubit rotational matrices, which leads to a QC encoding of one electron per qubit. We design QC circuits to evaluate M and V in one-electron diatomic molecules. In log2-log2 plots, errors and deviations of those evaluations decrease linearly with the number of shots and with slopes = −1/2. We illustrate an END/QC/VQS simulation with the pure electronic dynamics of H2+ We discuss the present results and future END/QC/QVS extensions.

1. Introduction

Quantum chemical dynamics seeks to describe chemical reactions in terms of quantum mechanics. Such an endeavor requires the solution of the time-dependent Schrödinger equation [1]: a partial linear differential equation, second-order in the particles’ positions and first-order in time , whose unknown is the time-dependent wavefunction , where represents the spin variables. Once is found, all the chemical properties of a reactive system can be calculated from it. Unfortunately, the solution of the time-dependent Schrödinger equation becomes computationally expensive even for relatively small molecular systems. Therefore, some approximations should be introduced for feasibility’s sake. One fruitful approach is to adopt the time-dependent variational principle (TDVP) [2]. Therein, a trial wavefunction = depending on a set of time-dependent parameters is optimized for dynamical evolution by subjecting it to the stationary condition of the quantum action: , [2]. This procedure generates a system of classical-like equations of motion for the parameters that takes the place of and is easier to integrate than the time-dependent Schrödinger equation. Furthermore, guided by chemical insight, one can propose relatively simple trial wavefunctions that deliver accurate predictions at low computational cost. A successful employment of the TDVP for quantum chemical dynamics has been provided by the electron nuclear dynamics (END) method [3,4]. END adopts a total trial wavefunction that contains frozen Gaussian wave packets to describe nuclei and a single-determinantal wavefunction in the Thouless representation [5] to describe electrons. END has proven to be both accurate and feasible for the simulation of a vast array of time-dependent chemical processes, e.g., Diels–Alder, SN2, and ion cancer therapy reactions, inter alia [3,4,6,7,8,9].

While END/TDVP simulations run relatively fast, they become inevitably slower when applied to extremely large chemical systems, e.g., to the sizable biomolecules involved in ion cancer therapy reactions [4,6,7,8,9]. Therefore, we have devoted considerable efforts to accelerate the END/TDVP method for those simulations [4,6,7,8,9]. Broadly speaking, an END/TDVP simulation involves three essential computational tasks [3,4]: (I) the calculation of atomic and molecular basis functions integrals corresponding to the trial wavefunction, (II) the calculation of all the components of the END/TDVP equations of motion, and (III) the time integration of those equations. While tasks equivalent to I and III are present in other quantum chemistry methods, task II is specific to the END/TDVP approach and will be the main focus of this investigation. To accelerate the aforesaid tasks in our END/TDVP code PACE [4], we have employed various state-of-the-art techniques for classical (i.e., standard) computers, e.g., a mixed programming language (Python for logic flow and Fortran and C++ for numerical calculations), intra- and internode parallelization, and the fast OED/ERD atomic integrals package [10] from the ACES [11] program, inter alia. Equipped with these capabilities, we were able to perform the first END/TDVP simulations of ion cancer therapy reactions involving large molecules, e.g., ion-induced water radiolysis in water clusters, and ion-induced DNA damage in nucleobases and the cytosine nucleotide [4,6,7,8,9]. Nevertheless, additional acceleration of END/TDVP simulations will be necessary to treat even larger systems.

In recent years, the burgeoning field of quantum computing (QC) [12,13,14] has shown immense potential to revolutionize quantum chemistry through the provision of efficient quantum computers and quantum algorithms to simulate chemical systems. Thus, various research groups have reformulated established quantum chemistry methods [1] into the QC framework (cf. Refs. [15,16] and citations therein). In this context, Li and Benjamin have recently developed a variational quantum simulator (VQS) to calculate TDVP dynamics [17]. VQS is a hybrid quantum/classical approach wherein each computational task is entrusted to the type of computer, either classical or quantum, that provides the fastest algorithms with current technology. Specifically, the calculation of the trial wavefunction and its related components for the TDVP equations of motion are assigned to a quantum computer at each time step; those tasks are executed with quantum circuits that are modifications of one devised by Ekert et al. [18]. On the other hand, the time integration of the TDVP equations is assigned to a classical computer operating standard software. Li and Benjamin successfully applied their VQS to simulate the TDVP dynamics of an Ising-like model system, thus demonstrating the viability and potential of their innovative approach [17].

The VQS provides a paradigm for a hybrid quantum/classical implementation of TDVP dynamics, but it will remain scarcely relevant for quantum chemical dynamics if it is only applied to Ising-like models. While those models can simulate spin dynamics, they fail to reproduce most of the basic features of molecules and are, therefore, unsuitable for realistic simulations of chemical reactions. Therefore, the extension of the VQS approach for the accurate description of chemical reactions is a crucial endeavor in both quantum chemistry and QC fields. In this manuscript, we will embark on such an enterprise by reformulating the END method for QC (END/QC) within the VQS scheme (END/QC/VQS; henceforth, we will name END/QC the general QC formulation of END and END/QC/VQS as its VQS realization).

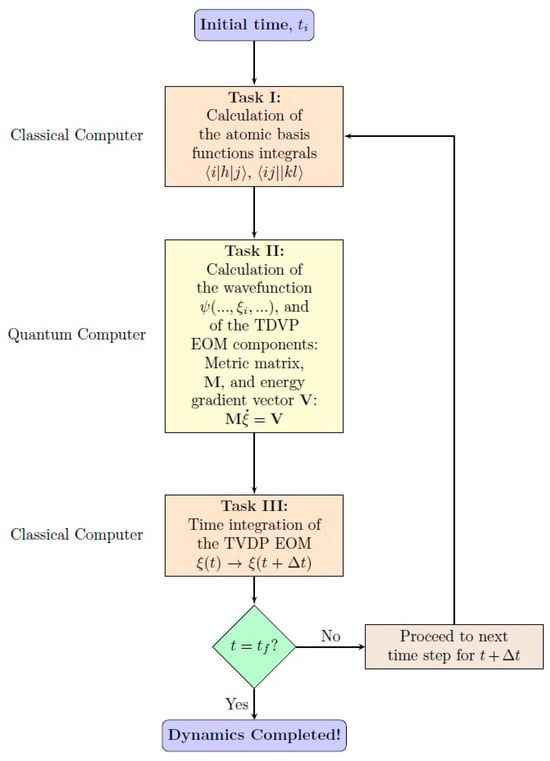

In terms of the previously discussed tasks I-III, END/QC/VQS involves the following sequence of processes (cf. Figure 1 for a flowchart). At a given time step, task I, the calculation of atomic and molecular basis functions integrals, is executed for the current nuclear and electronic configurations on a classical computer with the OED/ERD atomic integrals package [10]. With those integrals at hand, task II, the calculation of the components of the END/QC equations of motion, is executed on a quantum computer with quantum circuits that are END/QC versions of the general VQS circuit [17]. Specifically, our quantum circuits evaluate the END/QC trial wavefunction , and the metric matrix and energy gradient vector of the END/QC equations of motion (cf. Section 2, Section 5 and Section 6). Then, task III, the time integration of the latter equations, is executed from the current to the next time step on a classical computer with standard differential equation solvers. The last task provides the new nuclear and electronic configurations for the next time step so that a new cycle of tasks I through III ensues; this loop runs from the initial to the final time of a dynamical simulation.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the main computational tasks in an END/QC/VQS dynamics executed on classical and quantum computers.

While transparent in outline, END/QC/VQS poses various theoretical and computational challenges during its development. As previously mentioned, the electronic part of the END trial wavefunction is a single-determinantal wavefunction in the Thouless representation [5]. In this approach, a non-unitary operator in terms of time-dependent parameters generates the evolving electronic trial wavefunction by acting on a single-determinantal reference state : [3,4,5]. It is well known that QC is strictly formulated in terms of unitary operators and gates [14]; therefore, the original END formulation in terms of a non-unitary operator does not directly fit into the unitary QC framework. To circumvent this difficulty (and also for pure theoretical reasons), we decided to reformulate END in terms of the Fukutome unitary representation [19] of a single-determinantal state. In this case, a unitary operator in terms of time-dependent parameters substitutes the previous non-unitary operator and generates the evolving electronic trial wavefunction as . In this way, all its related terms fit directly into the unitary operators and gates of the quantum circuits. The aforesaid substitution of operators may seem simple in outline, but, in fact, it substantially changes the whole structure of the END formalism, as will be shown in Section 3 and Section 5. While we will adhere to a unitary representation in this manuscript, we should note that a non-unitary END/QC formalism with the Thouless representation [5] is indeed possible if the involved non-unitary operators are expressed as linear combinations of unitaries (LCUs) [20]. We will present that alternative formulation in a sequel.

The formulation of END/QC/VQS for all type of chemical systems is a challenging enterprise to be accomplished in stages. Therefore, in this first attempt, we will adopt some approximations and tackle particular systems. First, we will formulate END/QC for pure electronic dynamics, i.e., for the time evolution of electrons in the presence of fixed nuclei. In this scheme, the END/QC equations of motion will explicitly involve electronic TVDP variables—nuclear variables will act implicitly in those equations as time-independent parameters. Second, for pure electronic dynamics, we will formulate END/QC for multielectron model systems described with effective Hamiltonians and minimal basis sets; similar types of systems are usually employed to develop and test QC methodologies for quantum chemistry [15,16]. During these formulations, we will emphasize the continuous symmetry aspects of the END/QC formalism within the Fukutome unitary representation [19]; i.e., the END/QC connection with the unitary Lie group and its associated Lie algebra. Third, we will apply these END/QC developments to evaluate M and V in one-electron diatomic molecules and to simulate the pure electronic dynamics of a H2+ molecule. In the latter case, we will also consider the effect of the point group spatial symmetry in the END/QC equations of motions and dynamics. In these endeavors, we will execute our new QC circuits (algorithms) for task II on the QC software development kit QISKIT version 1.0 [21], which acts as a simulator of a real quantum computer. In this way, we can corroborate the step-by-step functioning of our QC circuits and gauge their numerical accuracy. We will utilize a real quantum computer for task II in a sequel.

As delineated in the previous paragraph, this manuscript presents the proof of concept of END/QC/VQS: a firm stepping stone from which we can continue developing this method to its full maturity. Thus, in upcoming publications, we will generalize the current END/QC/VQS for full electronic and nuclear dynamics, for general molecules described with ab initio Hamiltonians and large basis sets, and for executions on state-of-the-art quantum computers. Our group has presented a first glimpse into END/QC/VQS in Ref. [22]; however, herein, we present a more elaborated version of END/QC/VQS, both in terms of its formalism development and computer applications.

This manuscript is organized as follows. In Section 2, we will review the TDVP in terms of real variational parameters [2] because this form of the TDVP provides the most appropriate parameterization for the current version of END/QC/VQS. In Section 3, we will discuss the Fukutome unitary representation [19] of single-determinantal wavefunctions in the context of the Hartree–Fock (HF) and the END methods. In Section 4, we will define a family of model chemical systems for END/QC/VQS treatments in the spirit of the semi-empirical methods [23] in quantum chemistry. In Section 5, we will formulate the END/QC formalism to simulate pure electronic dynamics in those systems. In Section 6, we will apply END/QC/VQS to evaluate M and V in one-electron diatomic molecules and to simulate the pure electronic dynamics of a H2+ molecule. We will perform all the corresponding QC calculations on the QC software development kit QISKIT [21]. Finally, in Section 7, we will analyze the main results of this investigation and discuss future work.

2. Background: Time-Dependent Variational Principle (TDVP)

There are different versions of the time-dependent variational principle such as the Dirac-Frenkel variational principle [24,25], the McLachlan variational principle [26], and the simply named TDVP (for their definitions and equivalence conditions, cf. Refs. [27,28,29]). Since END is based on the TDVP [3,4], we will employ this variational principle to formulate END/QC. The TDVP starts with a trial wavefunction that depends on time-dependent variational parameters , , arranged in a column vector ; these parameters can be real or complex [2,3,4], but, in this investigation, we will take them as real without any loss of generality: (for the relationship between real and complex TDVP parameterizations, cf. Ref. [2]). The selection of a trial wavefunction for a chemical problem is a matter of chemical insight; thus, following quantum chemistry experience, single-determinantal [3,4,30], multi-configuration [31], and coupled-cluster wavefunctions [32,33,34] have been employed/proposed to simulate chemical reactions in the TDVP framework. For a chosen , the TDVP involves the quantum Lagrangian and quantum action functionals:

where is the system Hamiltonian, and are the initial and final times of the dynamics, and and are time derivative operators acting to the right and to the left, respectively; these operators produce a real Lagrangian with a symmetric distribution of the derivatives over the bra and ket states [2]. The denominator of in Equation (1) enforces normalization if the trial wavefunction is unnormalized [2]. However, we will parameterize with a unitary operator acting on a reference state :, so that = = 1 at all times. Therefore, we will omit the aforesaid denominator in and in all the subsequent TDVP equations (for the TDVP equations with an unnormalized trial wavefunction, cf. Refs. [2,3,4]). Under this condition, the Lagrangian is [2]

where is the expectation value of the total energy, and is the canonical variable conjugate to . To obtain the TDVP equations of motion, one should impose the stationary condition into the quantum action functional, , with respect to all the variational parameters and subjected to the end-point conditions . That procedure leads to a set of Euler-Lagrange equations for the parameters :

that in terms of the expressions in Equation (2) are [2]:

Above, the metric matrix is real and antisymmetric, and the energy gradient vector is real; and contain the kinematic and dynamic features of the system, respectively. It is clear from Equations (1)–(4) that the TDVP and its equations of motion are the quantum analogs of the classical Hamilton principle and of the classical Hamilton equations in symplectic form [35], respectively. In that scheme, the parameters and span a generalized quantum phase space [2,3,4,36]. Solving Equation (4) for the time-dependent parameters provides the evolution of the trial wavefunction in time [2,3,4,36].

3. Fukutome Unitary Representation of Single-Determinantal Wavefunctions

As discussed in Section 1, we will develop the END/QC formalism employing Fukutome unitary representation [19] of single-determinantal states. Therefore, to understand our formalism, we should review such a unitary approach in the context of the HF theory [37] (for its extension to the Kohn-Sham density functional theory, cf. Ref. [30]). As anticipated in Section 1, we will consider a system containing evolving electrons and fixed nuclei. The electronic description of that system involves a set of orthonormal HF spin-orbitals = , = 1, 2, … : = = , where and are spatial orbitals and spin eigenfunctions with position and spin variables and , respectively, and . Associated with the , we have a set of second-quantization creation and annihilation operators that satisfy the anti-commutation relationships [37]:

Having the vacuum state , , we can define a reference Slater determinant state with occupied spin-orbitals , … as:

In this investigation, we will follow Fukutome’s notation [19] and denote the occupied (hole) spin-orbitals in with the indices , the unoccupied (particle) spin-orbitals with the indices , and the whole spin-orbitals irrespective of their with occupancy with the indices … From , we can generate all the remaining single-, double-, etc., -excitation Slater determinants as , = , etc. All these single-determinantal states are orthonormal among themselves. While is arbitrary, we will take it as the HF ground state as is usually the case in END simulations [3,4]. The electronic Hamiltonian of the system in second-quantization form is

where and are the one- and two-electron integrals from the spin-orbitals [37].

To formulate the HF theory in unitary form, Fukutome considered the set of pair operators that span (generate) the Lie algebra (group) with commutation relationships [38,39,40]:

from them, one can construct operator and matrix realizations of the unitary Lie group [38,39,40] as:

where is an anti-Hermitian matrix containing the parameters . The unitary matrix acts on the orthonormal spin-orbitals as:

where is a new set of transformed spin-orbitals; since is unitary, the are orthonormal as well. Then, all the possible single-determinantal states that are non-orthogonal to , , can be generated from by the unitary transformation [19]:

where contains occupied (hole) transformed spin-orbitals .

Equation (11) provides a unitary representation of the single-determinantal states but its application is inconvenient due to redundancies in the parameters as shown shortly. Fortunately, Fukutome [19] solved this problem via an exact factorization of both and into two unitary components containing the non-redundant and redundant parameters and , respectively:

where the new operators and complex parameters are

Notice that only contains hole-hole and particle-particle pair operators, and only contains particle-hole and hole-particle ones. The matrix is where and . The matrix is

where

The functions and are matrix generalizations of the standard sine and cosine functions, respectively. From a QC standpoint, in Equation (14) can be interpreted as a multi-qubit generalization of the one-qubit matrices in terms of the rotational matrices , = 1, 2, 3, [14]; suggestively, resembles , cf. Section 5. The unitary matrices and act on the spin-orbitals as and , i.e., combines occupied spin-orbitals among themselves, and combines unoccupied spin-orbitals among themselves. The matrix acts on the spin-orbitals as:

i.e., combines occupied and unoccupied spin-orbitals among themselves. From a QC standpoint, the transformed orthonormal spin-orbitals in Equation (16) can be interpreted as multiple-qubit generalization of the one-qubit Bloch sphere states [14], cf. Section 5. The action of the operator on is

i.e., combines the occupied spin-orbitals in among themselves and transforms into the equivalent states . The action of the operator on is

i.e., combines occupied and unoccupied spin-orbitals into and transforms the latter into the non-equivalent states . Thus, Equations (17) and (18) demonstrate that and are the non-redundant and redundant parameters in the unitary representation of all the single-determinantal states from . Then, we can omit in = = , Equation (11), and take = , Equation (18), as the non-redundant Fukutome unitary representation of the all the non-equivalent single-determinantal states from and non-orthogonal to it [19].

Fukutome unitary representation, Equation (18), establishes a bijective mapping between the single-determinantal states and the parameters [3,4,19]. In a time-independent context, this representation provides a suitable parameterization of stationary states for HF energy optimizations, instabilities analyses, and symmetry breaking classifications [19]. In a time-dependent context, Fukutome unitary representation provides a suitable parameterization of time-evolving states for END/QC optimizations and for time-dependent symmetry breakings, as the Thouless non-unitary representation [5] does in the standard END [3,4,41,42]. We will employ Fukutome unitary representation to formulate END/QC in Section 5 and Section 6. In this and the following section, we keep Fukutome’s original parameters but we will turn to real parameters in Section 5.

4. Model Systems for END/QC

The general formulation and code implementation of END/QC for any type of chemical system are challenging. We will present such a general treatment in a subsequent publication. Herein, as a proof of concept, we will implement END/QC for a family of model chemical systems, which in some cases admit analytical solutions. This family of models is constructed by a set of five approximations that resemble those employed in semi-empirical methods for quantum chemistry [23]. The END/QC trial wavefunction for any of these systems will be a single-determinantal wavefunction in Fukutome unitary representation, Equation (18). The approximations defining these systems are:

Approximation 1.

We adopt a system consisting of chemical units; each unit has two electrons with opposite spins up and down , respectively. The units can be atoms, molecules, or monomers, identical or not. The units can be real subsystems with two actual electrons (e.g., H−, Li+, H2, HeH+, etc.) or model subsystems with two active electrons in the presence of a frozen electronic core [23]. The units together can constitute a single molecule (H2), a super-molecule (H2)n, or a polymer/lattice (-- H2 -- H2 -- H2 --).

Approximation 2.

Within a unit, each electron has available two spin-orbitals, one occupied and another unoccupied with respect to the reference state. Specifically, the spin-orbitals and are available for the unit electrons with spins up and down, respectively. This approximation implies a minimal basis set [37] with two atomic orbitals per unit to construct the spin-orbitals.

Approximation 3.

Particle-hole excitations are only allowed within spin-orbitals with the same type of spin. To enforce this, we set in the END/QC trial wavefunction ,

Equation (18), and resulting expressions:

where is the z-component of the one-electron spin operator. With Equation (19), becomes an unrestricted HF (UHF) state [37] [an axial-spin-density-wave (ASDW) wavefunction in Fukutome’s classification of HF states [19]], where the transformed spin-orbitals remain as one-electron spin eigenfunctions, and the spin symmetries of with respect to and (squared total spin) are preserved and lost, respectively. UHF wavefunctions are regularly used in quantum chemistry, especially to describe radicals and bond making/breaking processes [19,37]. Without this approximation, will be a less useful generalized HF (GHF) wavefunction [1,19], where the transformed spin-orbitals contain both spin-up and spin-down components, and all the spin symmetries of are lost.

Approximation 4.

Particle-hole excitations are only allowed within units. That is, an electron in the occupied spin-up spin-orbital can only be excited to the unoccupied spin-up spin-orbital in the same unit:

This approximation becomes exact with well-separated units carrying localized spin-orbitals.

Approximation 5.

If Approximation 1 involves active electrons in the presence of a frozen electronic core, the ab initio Hamiltonian , Equation (7), should be transformed into an effective Hamiltonian by applying appropriate semi-empirical approximations [23] to the one- and two-electron integrals of . Unlike the previous approximations, this one eludes a general formulation because it depends on the chemical features of the model system at hand. Therefore, we will present examples of this approximation as we investigate concrete systems in Section 6 of this manuscript and in subsequent publications.

5. Formulation of END/QC for the Model Systems. Natural QC Encoding

Application of approximations 1–4 in conjunction with the commutation relationships, Equation (8), to the operator and matrix , Equations (12) and (14), leads to their factorization into particle-hole-pair components:

where and denote ordinary and tensor products, respectively, and is a compound index, = . and SU(2) depend on a single parameter as:

and

In Equations (21)–(23), the multi-qubit matrix , Equation (14), simplifies into a tensor product of one-qubit unitary matrices [14], the matrix , Equation (14), into a set of numbers , and the matrix functions , , and , Equation (15), into the numerical functions and in terms of sine, cosine, and exponential functions. Furthermore, through , we can switch from a complex to a real parameterization, i.e., in Equation (23); the latter scheme fits into the TDVP with real variational parameters discussed in Section 2.

The factorizations in Equation (21) into particle-hole-pair components suggests a natural QC encoding for the current model systems. In this scheme, each electron of a particle-hole-excitation pair can be assigned to a single qubit with compound index . We will employ this QC encoding during the rest of this manuscript and present alternative formulations in terms of standard QC encodings (e.g., Jordan-Wigner, Kitaev, etc., [16]) in a sequel. In the natural QC encoding, the occupied and unoccupied spin-orbitals and correspond to the computational basis states (vectors) and of the qubit with index :

where the equivalences between operator-wavefunction and matrix-vector representations are indicated with the symbol . In addition, we can define pseudo spin angular momentum operators , , and , and an electron number operator as

where their equivalences with the identity and Pauli matrices , , , and of the qubit are shown. By inverting the relationships in Equation (25), one can encode the operators and , and the electronic Hamiltonian , Equation (7), in terms of the matrices , , and of all the qubits (cf. Section 6). The first three operators in Equation (25) span (generates) the SU(2) Lie algebra (group), and and are the Casimir operators of U(2) SU(2). The mutually commuting , and act on the spin-orbital and as

with equivalent expressions in terms of the states (vectors) and and matrices , , , and .

From this point to the end of this section, we will concentrate on the END/QC expressions for QC programming. Therefore, we will prioritize the matrix-vector representation of END/QC [in terms of the matrices , , , and acting on the computational basis states (vectors) and ] over its equivalent operator-wavefunction representation (in terms of the operators , , and acting on the spin-orbitals and ]. Nevertheless, the equivalences between both representations can be obtained straightforwardly [cf. Equation (25)].

U(2) can be factorized in terms of a global phase angle and three extrinsic Euler angles , and in the z-y-z axis convention: = [14], where is the 2 × 2 rotation matrix around the axis by an angle . Then, from Equation (23), one obtains , , , and so that

This additional factorization per qubit is useful in subsequent QC implementations. Alternatively, can be expressed as a general (1-norm quaternion) rotation by an angle about an axis with unit vector = , = 1, [14]:

from which , , and ; then, is a rotation by an angle about an axis on the x-y plane and tilted by an angle from the y-axis. For constant angles , the matrices form a one-real-parameter continuous subgroup SU(2). Since the SU(2) matrices are identical to the matrices of the SU(2) irreducible representation , the tensor product in Equation (21) goes along with the products of the SU(2) irreducible representations , which, in general, produce reducible representations, e.g., [43].

To obtain the components of the END/QC equations of motion for the model systems in QC form, we should first express the corresponding wavefunction and Hamiltonian in that form. The reference Slater determinant state for electrons is now [cf. Equation (6)]

Then, through Equations (21)–(27), the END/QC trial wavefunction , Equation (18), corresponds to the QC state with real parameters and .

where the original multiple-qubit states in Equation (16) simplifies into standard single-qubit Bloch sphere states in Equation (30). In addition, by mapping the operators and into the identity and Pauli matrices via Equation (25) [e.g., , etc.], we can encode the electronic Hamiltonian , Equation (7), as

where the coefficients are combinations of the original one-electron and two-electron integrals in Equation (7), and the unitary matrices are combinations of the identity and Pauli matrices. The explicit expressions of the and depend on the chemical features of the model system under consideration. We will present examples of these expressions for one-electron diatomic molecules in the following section and for additional molecules in a sequel. From Equation (30), we can obtain the derivatives of the END/QC trial wavefunction with respect to its variational parameters and as

and

where = 1, 2 …, , , , and are defined, and their associated factors are

Our Equations (32) and (33) are equivalent but not identical to their VQS counterparts in Ref. [17]; the main differences between those and our expressions lie in the occurrence of two derivative terms per each angle , and in the content of some terms. Differences aside, our equations admit a QC implementation similar to that in Ref. [17], cf. next section. From Equations (31)–(34), we can obtain the metric matrix and the energy gradient vector with respect to the variational parameters and = [cf. Equation (4)]:

and

where and = , and and = , cf. Equations (32)–(34). Each summand between parentheses in Equations (35) and (36) contains one, two, or four terms of the form (cf. Ref. [17]):

where the QC parameters and , and the unitary matrix are

where now and , and and , cf. Equations (32)–(34). The terms in Equation (37) can be evaluated with our END/QC versions of the VQS circuit in Ref. [17]. We will illustrate such QC evaluations in the following section.

6. Application of END/QC/VQS to One-Electron Diatomic Molecules

As a proof of concept and for illustration’s sake, we will now apply END/QC/VQS to simulate the pure electronic dynamics of one-electron diatomic molecules. We will consider the general case of hetero-nuclear diatomic molecules that contains the homo-nuclear ones as a simple subcase. In the framework of the model systems defined in Section 4, each of these molecules forms a single one-electron unit furnished with a minimal basis set of two Slater-type atomic orbitals [37] , where and are the labels of the nuclei. With this basis set, we can construct one occupied and one unoccupied spin-orbital:

where and are the highest occupied and lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals (HOMO and LUMO), respectively, is a one-electron spin eigenfunction, and , , and are the molecular orbital coefficients from a self-consistent-field HF calculation [37]. The transformed occupied and unoccupied spin-orbitals and the END/QC total trial wavefunction from the reference state are [cf. Equations (29) and (30)]

The electronic Hamiltonian of the considered molecules is [cf. Equation (7)]

where the one-electron integrals so that . Notice that within the present atomic basis set, the Hamiltonian is exact. and are the orbital energies of the HOMO and LUMO , respectively, and is the HOMO–LUMO energy gap. From Equations (40) and (41), we can obtain the energy of the considered systems as:

To derive and implement the END/QC equations motion, we switch to the matrix-vector representation of END/QC delineated in Equations (29)–(38). Then, in the present case, the transformed occupied and unoccupied computational basis states, and the END/QC total trial wavefunction from the reference state are

In some of the above expressions, we have adopted a simpler notation, more amenable for QC coding, where = , = , = , = , = , and = , and , cf. Equation (27). From Equation (43), the derivatives of with respect to the variational parameters , , and are

where , and are equivalent to , and in Equation (34), respectively,

Through Equation (25), we can encode the electronic Hamiltonian of Equation (41) into the QC form of Equation (31) as

From Equations (44)–(46), we obtain the components of the END/QC equations of motion as

and

For non-null values in Equations (47) and (48), we write first the QC expressions of the elements of and obtained from Equations (44)–(46), and second their equivalent analytical expressions obtained from Equations (40)–(42). In terms of the latter, the END/QC equations of motion are

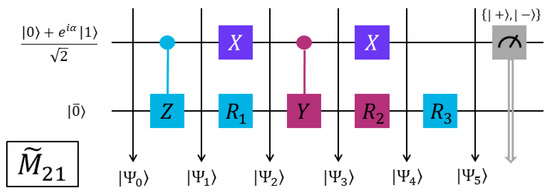

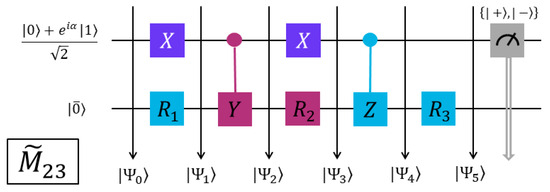

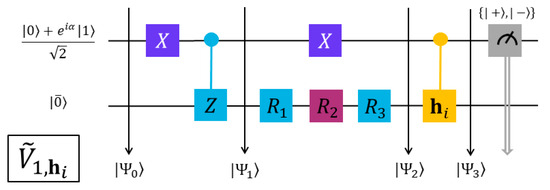

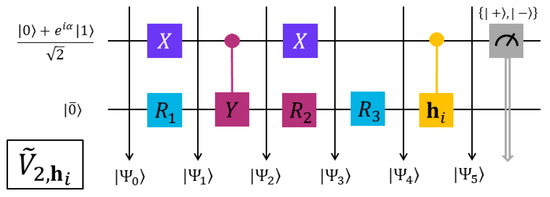

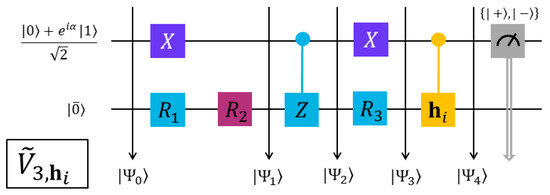

To obtain and for the END/QC/VQS simulations, we need to evaluate their basic elements and in Equations (47) and (48) in a QC fashion. After recasting these elements in the form of Equation (37), we can evaluate them with the five quantum circuits shown in Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6; these circuits are the END/QC versions of the VQS circuit in Figure 2 of Ref. [17]. Each of the present circuits has one ancillary qubit prepared in the state , where the values of the circuit parameter and , Equation (37), are obtained with Equation (38). The values of and employed in the present QC evaluations are listed in Table 1. All the ancillary qubits have the same operators: two gates and two control gates, but in different orders and with varying targets. Each of the present circuits has also one register qubit initially prepared in the END/QC reference state . The operators in the register qubits correspond to those involved in each evaluated element and , cf. Equations (47) and (48). All these circuits end with a measurement of the ancillary qubit in the basis [14], where = are the eigenvectors of the Pauli matrix with eigenvalues +1 and −1, respectively [14]. The average measurement provides the expectation value = , cf. Equations (37) and (38), as explained in the following paragraph.

Figure 2.

QC circuit to evaluate the element , Equation (47).

Figure 3.

QC circuit to evaluate the element , Equation (47).

Figure 4.

QC circuit to evaluate the element ,, Equation (48).

Figure 5.

QC circuit to evaluate the element ,, Equation (48).

Figure 6.

QC circuit to evaluate the element ,, Equation (48).

Table 1.

Values of the circuit parameters and , and of the END/QC variational parameters and for the QC evaluation of the elements and , and of the matrix and vector 2–6.

All the present quantum circuits operate similarly and we will elucidate their execution by analyzing the sequential operations in the circuit for shown in Figure 3. At each of the steps drawn in Figure 3, the circuit total state successively is

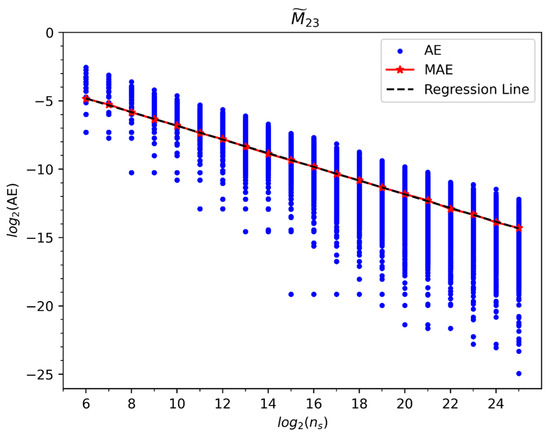

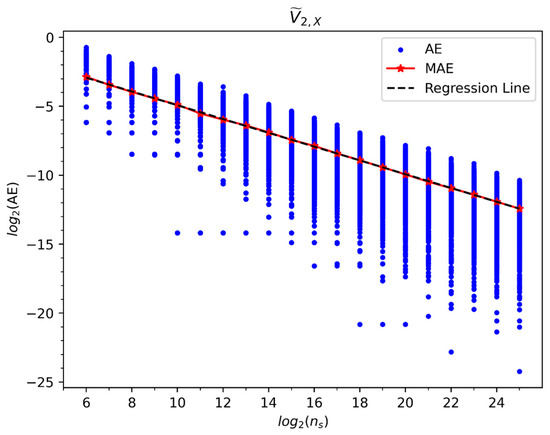

To appraise the accuracy and precision of these circuits, we will examine their results for the elements , , , and corresponding to the values of the END/QC variational parameters and listed in Table 1. These are the only elements having circuit-evaluated components not identical to zero and . We performed all these circuit calculations on the QC software development kit QISKIT [21]. To appraise the accuracy of these QC calculations, we will consider the absolute error (AE), , and mean AE (MAE), :

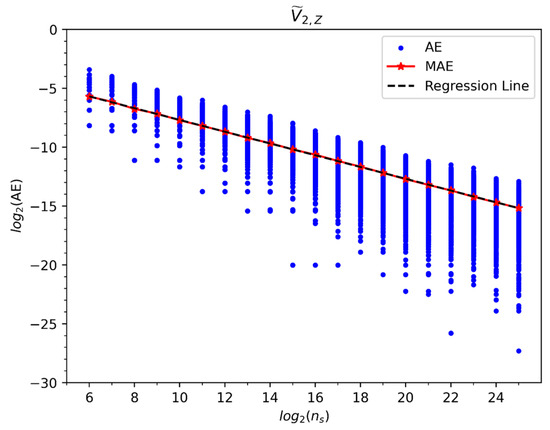

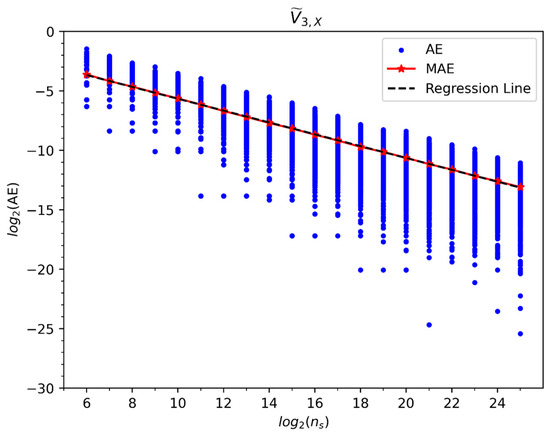

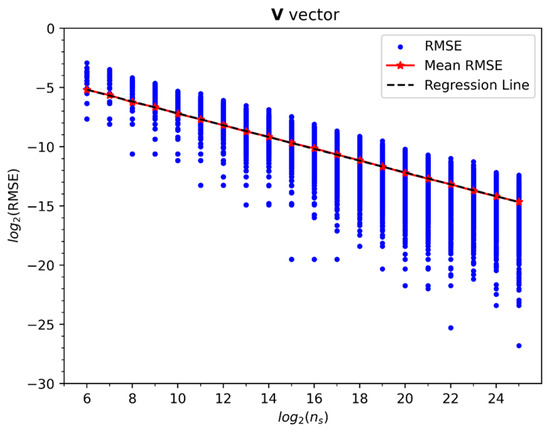

where is the value of , , , or from the repetition of a QC calculation with shots, and is the value of the same element from its analytical expression, Equations (47) and (48). The is the average of the over the total number of repetitions . In Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10, we plot the for = 1 to = 1000 repetitions, and the vs. . In each figure, for a given number of shots , the individual values of appear as vertically scattered blue points, and the values of appear as red start points/lines. In addition, in each figure, we plot the regression line corresponding to vs. in black and report its slope , intercept , and coefficient of determination in each figure caption. Remarkably, all the regression lines exhibit the same slope with a perfect correlation with :

i.e., the asymptotic behavior of these errors with respect to is of the order . To appraise the precision of these QC evaluations, we will now consider the standard deviation (SD), , of the individual with respect to its :

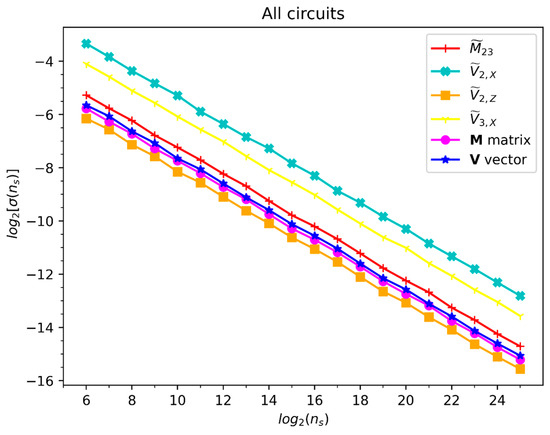

where all the terms have been defined in/after Equation (55). In Figure 11, we plot the vs. of the QC calculations of , , , and and their corresponding regression lines. Like in the MAEs’ case, all the regression lines of the SDs show the same slope , with a perfect correlation with . This demonstrates that the asymptotic behavior of the error spread with respect to is of the order . The QC evaluations of the remaining elements and having circuit-evaluated components identical to zero and exhibit same behaviors and trends in their accuracy and precision.

Figure 7.

log2-log2 plot of the absolute error (AE) in QC calculations of the element vs. the number of shots . Values corresponding to END/QC variational parameters and , and circuit parameters and . AEs from 1000 repetitions per each appear as scattered blue dots, and their mean absolute error (MAE) per each appear as red stars. For the latter, a regression line with slope , intercept , and coefficient of determination appears as a black dashed line.

Figure 8.

log2-log2 plot of the absolute error (AE) in QC calculations of the element vs. the number of shots . Values corresponding to END/QC variational parameters and , and circuit parameters and a.u. AEs from 1000 repetitions per each appear as scattered blue dots, and their mean absolute error (MAE) per each appear as red stars. For the latter, a regression line with slope , intercept , and coefficient of determination appears as a black dashed line.

Figure 9.

log2-log2 plot of the absolute error (AE) in QC calculations of the element vs. the number of shots . Values corresponding to END/QC variational parameters and , and circuit parameters and a.u. AEs from 1000 repetitions per each appear as scattered blue dots, and their mean absolute error (MAE) per each appear as red stars. For the latter, a regression line with slope , intercept , and coefficient of determination appears as a black dashed line.

Figure 10.

log2-log2 plot of the absolute error (AE) in QC calculations of the element vs. the number of shots . Values corresponding to END/QC variational parameters and , and circuit parameters and a.u. AEs from 1000 repetitions per each appear as scattered blue dots, and their mean absolute error (MAE) per each appear as red stars. For the latter, a regression line with slope , intercept and coefficient of determination appears as a black dashed line.

Figure 11.

as a function of for the results of the individual QC circuits and of the matrix and vector. Legend on the upper right specifies the color and marker for each of the curves.

Finally, to elucidate a full END/QC/VQS simulation, we will examine its operations for the pure electronic dynamics of a H2+ molecule, an homonuclear diatomic system. Before examining computational aspects, we will briefly discuss the spatial symmetry of H2+ and its effect on the END/QC dynamics. H2+ has a spatial symmetry, and its HOMO and LUMO, and , belong to the one-dimensional irreducible representations of gerade () and ungerade () functions, respectively [37,44]. This discrepancy between representations dictates that exactly [37,44], cf. Equation (46). Due to this condition, the END/QC equations of motion for H2+, Equation (49), can be solved analytically as

where and are two initial conditions. Notice that the time-dependent exponential term of involves the angular frequency = , i.e., the HOMO–LUMO gap. remains stationary as an spin-orbital or if = or = , = , respectively. For values of different from the previous ones, superimposes both spin-orbitals and , undergoes a real dynamics, and leads to molecular properties evolving with angular frequency = = (cf. the last paragraph of this section).

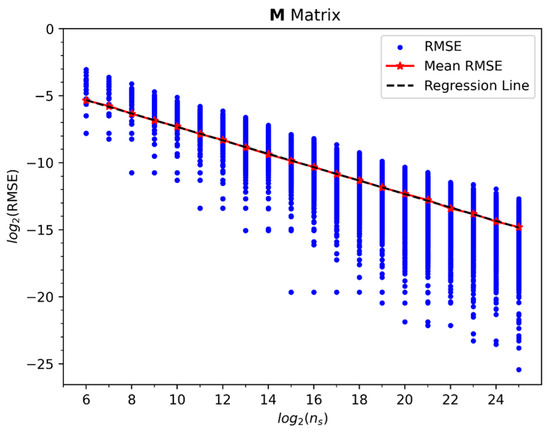

To perform an END/QC/VQS simulation according to the flowchart in Figure 1, we will consider a H2+ molecule described with a minimal STO-3G basis set [37] (cf. Approximation 1, Section 4), and with a bond distance = 1.4 a.u. The END/QC/VQS simulation of this system starts with task I that calculates the spin-orbital integrals = −1.2528 a.u. and = −0.4756 a.u., cf. Equation (46), for the initial nuclear positions of H2+. This task is performed on a classical computer with the OED/ERD atomic integrals package [10] incorporated in our END code PACE [4]. In the present example, task I need not be repeated at each successive time step because the nuclear positions of H2+ do not change during pure electronic dynamics. Next, task II calculates the matrix and vector for the values of the END/QC variational parameters = and at each time step. Task II is performed on the QC software development kit QISKIT [21] with the QC circuits in Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6, which calculate the basic elements and as discussed previously; these elements are subsequently combined to construct and via Equations (47) and (48). To appraise the accuracy and precision of the and calculations, we consider the root mean squared error (RMSE), and the mean RMSE, , for = or as

where is the value of an element/component of from the repetition of a QC calculation with shots, is the value of the same element/component from an analytical expression, Equations (47) and (48), is the number of elements/components of , and is the total number of repetitions = 1000; the RMSE is proportional to the Frobenius norm . Like in Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10, we plot in Figure 12 and Figure 13 the , , and the regression line of the latter vs. of = and , respectively, for the values of the END/QC variational parameters and listed in Table 1. In addition, we plot in Figure 11 the log2 of the SD of the ’s with respect to its and its regression line vs. . Like in all previous QC calculations, the log2-log2 plots of the MRSMEs and SDs vs. show the same slopes with perfect linear correlations; furthermore, both metrics again scale asymptotically with an order .

Figure 12.

log2-log2 plot of the root mean square error (RMSE) in QC calculations of the matrix vs. the number of shots . Values corresponding to END/QC variational parameters and , and circuit parameters and . RMSEs from 1000 repetitions per each appear as scattered blue dots, and their mean RMSEs per each appear as red stars. For the latter, a line of regression with slope , intercept , and coefficient of determination appears as a black dashed line.

Figure 13.

log2-log2 plot of the root mean square error (RMSE) in QC calculations of the vector vs. the number of shots . Values corresponding to END/QC variational parameters and , and circuit parameters and a.u. RMSEs from 1000 repetitions per each appear as scattered blue dots, and their mean RMSEs per each appear as red stars. For the latter, a regression line with slope , intercept , and coefficient of determination appears as a black dashed line.

Finally, task III integrates the END/QC equations of motion with the current and over one time step to obtain the new END/QC variational parameters and for the subsequent time step. This task is performed with the differential equations solvers of PACE [4] on a classical computer. Alternatively, in the present example, the dynamics can be computed analytically with the expressions in Equation (58).

To illustrate the dynamics of H2+ and gain chemical insight, we will present the time evolution of some molecular properties of H2+ from the time-dependent END/QC wavefunction . A first property to consider is the one-electron density [37]:

where is the one-electron density matrix in the atomic orbitals’ basis . provides the probability density to find the electron of H2+ in position at time . The other properties are the electron Mulliken populations [37] on the nuclei and , and , respectively:

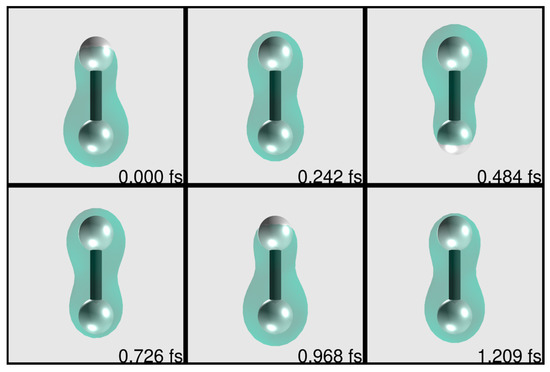

where is the overlap matrix of the atomic orbitals . and provide estimates of the total number of electrons around nuclei and , respectively. In Figure 14, we show six sequential snapshots of an END/QC/VQS/STO-3G computer animation of the pure electronic dynamics of H2+ at bond distance = 1.4 a.u. and from the initial conditions = 5° and = 0°. The distortion on the electronic density introduced by the initial variational parameters reproduces a perturbation on that density caused by an incoming ion or by an external electric field. The selected values of these parameters lead to a dynamics appropriate for validation and visualization. In each frame of Figure 14, white spheres represent the fixed H nuclei, and the green cloud depicts an electron density iso-value = 0.1 a.u. In the first frame at evolution time = 0 fs, we notice that the initial condition = 5° distorts the ground-state density conforming to the molecular symmetry into an upright pear shape density not conforming to symmetry but to the lower one. This reveals a spatial symmetry breaking [19,41,42] in and , which results from the combination of the spin-orbitals and from different irreducible representation in when = 5°, cf. Equation (58). In a sense, this superposition (“mixing”) of the spin-orbitals and its resulting symmetry breaking propel the subsequent dynamics. In the following frames, evolves to a -conforming shape at = 0.242 fs, to a -conforming downright pear shape at = 0.484 fs, again to a -conforming shape at = 0.726 fs, and finally to the initial upright pear shape at = 0.968 fs. This transformation of shapes repeats periodically in time. In chemical terms, these snapshots reveal that H2+ undergoes periodical intramolecular electron transfers between the two nuclei.

Figure 14.

Six sequential snapshots of an END/QC/VQS/STO-3G computer animation of the pure electronic dynamics of at bond distance a.u. and from the initial conditions and . Simulation times in femtoseconds. The white spheres represent the fixed H nuclei and the green cloud depicts an electron density iso-value a.u.

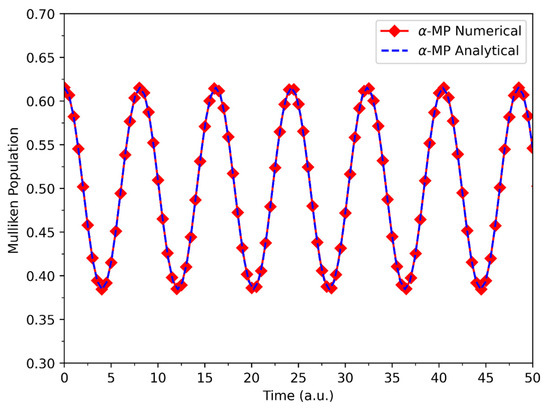

Finally, in Figure 15, we plot the electron Mulliken population on one of the nuclei of H2+ vs. time obtained by numerical integration of the END/QC equations, Equation (49), with the Shampine-Gordon predict-evaluate-correct-evaluate method [45] in PACE [4], and obtained from the analytical solution in Equation (58). Numerical and analytical results are identical as expected. Both types of Mulliken populations oscillate sinusoidally with the theoretical period = = = 8.0844 a.u., cf. Equation (58), where = −1.2528 a.u. and = −0.4756 a.u. in H2+ with = 1.4 a.u.. Figure 15 also reveals the aforesaid intramolecular electron transfers.

Figure 15.

Electron Mulliken population (MP) on a H nucleus vs. time from an END/QC/VQS/STO-3G simulation of the pure electronic dynamics of at bond distance a.u. and from initial conditions and .

7. Conclusions and Future Work

In this manuscript, we present the first step toward the QC formulation of the END method [3,4] within the VQS scheme [17], i.e., END/QC/VQS. END [3,4] is a time-dependent, variational, direct, and non-adiabatic method to simulate various types of chemical reactions and scattering processes. As implemented in our code PACE [4] on classical computers, END adopts a total trial wavefunction that represents nuclei with frozen Gaussian wave packets and electrons with a single-determinantal state in the Thouless non-unitary representation [5]. The END equations of motions are obtained through the application of the TDVP [2] to the END trial wavefunction; this procedure renders a set of symplectic equations for the nuclear and electronic variational parameters , , where is the phase-space metric matrix and the energy gradient vector [2,3,4]. To implement END on quantum computers, we adopt the VQS scheme [17]: a hybrid quantum/classical approach to simulate symplectic equations of motion from the TDVP [2] and analogous variational principles [24,25,26]. In our case, an END/QC simulation in the VQS scheme involves three main tasks: (I) the calculation of atomic and molecular basis functions integrals on a classical computer, (II) the calculation of all the components of the END/QC equations of motion, and , on a quantum computer, and (III) the time integration of those equations, , on a classical computer. The philosophy of the VQS scheme [17] is to perform each numerical task on the type of computer, either classical or quantum, that delivers the most efficient result with current technology.

To derive the general END/QC formalism, we substitute Thouless non-unitary representation of the END single-determinantal electronic state [3,4] with Fukutome unitary representation [19] of the same state. Through this innovation, the new END/QC formalism fits directly into the unitary framework of QC [14]. Fukutome representation is based on the Lie unitary group [19]; therefore, to understand the END/QC structure, we present a review of Fukutome representation that underlines its relationship with the group and associated algebra via second quantization. In this context, we are the first to identify Fukutome unitary transformation matrices and transformed spin-orbitals as multi-qubit generalizations of one-qubit unitary matrices and of one-qubit Bloch sphere states [14], respectively. In this investigation, we adopt a Fukutome unitary representation in terms of real parameters because it fits directly into the chemical systems under consideration. Accordingly, we also present a review of the particular form of the TDVP in terms of real variational parameters [2]. Nevertheless, it is possible to derive alternative formulations of END/QC in terms of the Fukutome unitary representation with complex parameters, or in terms of the Thouless non-unitary representation with complex parameters via LCU [20]; we will present these alternative approaches in a following study soon.

The formulation and code implementation of END/QC for any type of dynamics and chemical systems are challenging endeavors. Therefore, in this investigation, we develop END/QC for pure electronic dynamics, i.e., for the time evolution of the electrons in the presence of fixed nuclei. Furthermore, within this dynamics, we derive END/QC for a family of model chemical systems defined by a set of four approximations; the latter are akin to semi-empirical approximations [23] employed in quantum chemistry [23]. In essence, these model systems consist of various chemical units (atoms, molecules, monomers, etc.), each of them containing two effective electrons with opposite spins and represented with a minimal basis set. For these systems, Fukutome unitary transformation matrices factorize into one-qubit matrices; in turn, each of these matrices factorizes into three one-qubit rotational matrices , , and in terms of two real angle parameters and . Concomitantly, Fukutome transformed spin-orbitals become one-qubit Bloch sphere states in terms of and . This decomposition leads to a natural QC encoding of END/QC for the chosen systems wherein each individual electron can be assigned to a single qubit. We adopt this natural encoding in this investigation and will present alternative formulations in terms of standard QC encodings [16] in a following study soon.

Within the described framework, we derive all the END/QC expressions for one-electron heteronuclear diatomic molecules. We present various formulas to evaluate the END/QC spin-orbitals, wavefunction, total energy, matrix and vector in both analytical and QC programming forms. In addition, we present the encoded Hamiltonian and full END/QC equations of motion. To evaluate and , we design and code five QC circuits (cf. Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6) on the QC software development kit QISKIT [21], which acts as a simulator of a real quantum computer; these circuits are the END/QC versions of the VQS circuit [17]. For illustration’s sake, we analyze the step-by-step functioning of the END/QC circuit depicted in Figure 3. With these circuits, we evaluate the elements/components of and , and the whole and constructs, and calculate various metrics to gauge the accuracy (as MAE or mean RMSE) and precision (as SDs) of the QC results with respect to their analytical counterparts. Remarkably, in log2-log2 plots, we find that the error and deviation of all the QC results exhibit a perfect decreasing linear correlation with the number of shots and with a same slope equal to −1/2 (cf. Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13). In other words, we find that the error and deviation of these QC calculations scale asymptotically with order .

We illustrate a full END/QC/VQS simulation with the pure electronic dynamics of a H2+ molecule, a homonuclear diatomic subcase. In this endeavor, we execute all the QC circuits for task II on the QC software development kit QISKIT [21]. We first demonstrate that this H2+ two-parameter END/QC dynamics has the analytic solution = constant and , where the angular frequency is the HOMO–LUMO energy gap. We exemplify the three main tasks of the END/QC/VQS algorithm with this H2+ case. Finally, we plot the time evolutions of the one-electron density and of the electron Mulliken populations corresponding to the END/QC/VQS dynamics of H2+. Both properties evolutions reveal a periodic intramolecular electron transfer between the two nuclei. The analytical solution of the END/QC equations indicates that the “trigger” of this dynamics is the breaking of the spatial symmetry in the initial END/QC wavefunction; such breaking is generated by the superposition of the HOMO and LUMO that correspond to the gerade and ungerade 1D irreducible representation of , respectively [19,41,42]. The plot of the electron Mulliken population vs. time from the numerically integrated END/QC/VQS equations agrees with its counterpart from analytical formulas. Those electron Mulliken populations oscillate in time with an angular frequency equal to the HOMO–LUMO energy gap .

This manuscript presents a successful proof of concept of END/QC/VQS, a solid foundation from which we can continue developing this method to its full maturity. However, we would like to emphasize that we are not claiming that this investigation has completely solved the arduous problem of simulating chemical reactions on quantum computers, nor that this investigation will revolutionize the fields of QC and quantum chemical dynamics. On the contrary, this investigation is just the first step toward a fully developed END/QC/VQS, a method currently in its infancy. The objective merits of this investigation lie on the introduction of the Fukutome unitary representation [19] as a key tool to develop END/QC/VQS, the first derivation of the END/QC/VQS formalism for model systems with any number of electrons, the first END/QC/VQS calculations of the metric matrix and the gradient vector in one-electron diatomic molecules, and the first END/QC/VQS simulation of the pure electronic dynamics with fixed nuclei of the H2+ molecule (all those one-electron prototypes provide analytical solutions for comparison). We emphasize that in those efforts, we executed all the reported QC algorithms on the QC software development kit QISKIT [21] and not on real quantum computers. Thus, this investigation is the first and necessary step in the long road leading to the chemical reactions’ simulations on quantum machines. Toward this goal, in a series of forthcoming publications, we will first apply the current END/QC/VQS to larger model systems in order to further appraise this novel approach. Then, and more importantly, we will generalize the current END/QC/VQS for full electronic and nuclear dynamics, and for any type of molecules described with ab initio Hamiltonians and large basis sets. In this regard, we are currently implementing full nuclear and electronic END/QC/VQS dynamics of various multielectron molecules, such as H2, LiH, BeH2, H2O, etc. Finally, we will extend our QC formulation to the currently classical tasks, tasks I and III, of END/QC/VQS and execute the QC algorithms on real quantum computers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.d.F. and J.A.M.; methodology, I.d.F. and J.A.M.; software, J.C.D.; validation, J.C.D. and J.A.M.; formal analysis, J.C.D. and J.A.M.; investigation, J.C.D. and J.A.M.; data curation, J.C.D.; writing—original draft preparation, J.A.M.; supervision, I.d.F. and J.A.M.; project administration, J.A.M.; funding acquisition, J.A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program (DGE 2140745, to J.C.D.), by a Texas Tech University (TTU) Graduate School Fellowship (to J.C.D.), and by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant 1R15GM128149-01 (to J.A.M.).

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.

Dedication

We warmly dedicate this article to the memory of our collaborator and friend Professor Ismael de Farias, who encouraged us to enter the enthralling field of QC and taught us many useful things in that area.

Acknowledgments

All present calculations have been performed at the TTU High Performance Computer Center.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- McWeeny, R. Methods of Molecular Quantum Mechanics, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, P.; Saraceno, M. Geometry of The Time-Dependent Variational Principle in Quantum Mechanics. In Lecture Notes in Physics; Ehlers, J., Hepp, K., Kippenhahn, R., Weidenmüller, H.A., Zittartz, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Deumens, E.; Diz, A.; Longo, R.; Öhrn, Y. Time-dependent theoretical treatments of the dynamics of electrons and nuclei in molecular systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1994, 66, 917–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stopera, C.; Grimes, T.V.; McLaurin, P.M.; Privett, A.; Morales, J.A. Some Recent Developments in the Simplest-Level Electron Nuclear Dynamics Method: Theory, Code Implementation, and Applications to Chemical Dynamics. Adv. Quantum Chem. 2013, 66, 113–194. [Google Scholar]

- Thouless, D.J. Stability conditions and nuclear rotations in the Hartree-Fock theory. Nucl. Phys. 1960, 21, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Privett, A.; Morales, J.A. Electron Nuclear Dynamics of Proton Collisions with DNA/RNA Bases at ELab = 80 keV: A Contribution to Proton Cancer Therapy Research. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2014, 603, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaurin, P.M.; Privett, A.; Stopera, C.; Grimes, T.V.; Perera, A.; Morales, J.A. In Honor of N. Yngve Öhrn: Surveying Proton Cancer Therapy Reactions with Öhrn’s Electron Nuclear Dynamics Method. Aqueous Clusters Radiolysis and DNA-Bases Damage by Proton Collisions. Mol. Phys. 2015, 113, 297–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Privett, A.; Teixeira, E.S.; Stopera, C.; Morales, J.A. Exploring water radiolysis in proton cancer therapy: Time-dependent, non-adiabatic simulations of H+ + (H2O)1 − 6. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, E.; Uppulury, K.; Privett, A.; Stopera, C.; McLaurin, P.M.; Morales, J.A. Electron Nuclear Dynamics Simulations of Proton Cancer Therapy Reactions: Water Radiolysis and Proton- and Electron-Induced DNA Damage in Computational Prototypes. Cancers 2018, 10, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flocke, N.; Lotrich, V. Efficient electronic integrals and their generalized derivatives for object oriented implementations of electronic structure calculations. J. Comput. Chem. 2008, 29, 2722–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotrich, V.; Flocke, N.; Ponton, M.; Yau, A.D.; Perera, A.; Deumens, E.; Bartlett, R.J. Parallel implementation of electronic structure energy, gradient, and Hessian calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 2008, 128, 194104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feynman, R.P. Simulating Physics with Computers. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 1982, 21, 467–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, D. Quantum Theory, the Church-Turing Principle and the Universal Quantum Computer. Proc. R. Soc. London. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1989, 425, 73. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, M.A.; Chuang, I.L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Romero, J.; Olson, J.P.; Degroote, M.; Johnson, P.D.; Kieferová, M.; Kivlichan, I.D.; Menke, T.; Peropadre, B.; Sawaya, N.P.D.; et al. Quantum Chemistry in the Age of Quantum Computing. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 10856–10915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McArdle, S.; Endo, S.; Aspuru-Guzik, A.; Benjamin, S.; Yuan, X. Quantum Computational Chemistry. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2020, 92, 015003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Benjamin, S.C. Efficient Variational Quantum Simulator Incorporating Active Error Minimization. Phys. Rev. X 2017, 7, 021050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekert, A.K.; Alves, C.M.; Oi, D.K.L.; Horodecki, M.; Kwek, L.C. Direct Estimations of Linear and Non-Linear Functionals of a Quantum State. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 88, 217901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukutome, H. Unrestricted Hartree-Fock Theory and Its Applications to Molecules and Chemical Reactions. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 1981, 20, 955–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, A.M.; Wiebe, N. Hamiltonian Simulation Using Linear Combinations of Unitary Operations. Quantum Inf. Comput. 2012, 12, 901–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadi-Abhari, A.; Treinish, M.; Krsulich, K.; Wood, C.J.; Lishman, J.; Gacon, J.; Martiel, S.; Nation, P.; Bishop, L.S.; Cross, A.W.; et al. Quantum computing with Qiskit. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.08810. [Google Scholar]

- Cortez, L. New Quantum Computing Techniques Applied to Chemistry Dynamics. Ph.D. Thesis, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX, USA, 25 October 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zerner, M.C. Semiempirical Molecular Orbital Methods. In Reviews in Computational Chemistry; Lipkowitz, K.B., Boyd, D.B., Eds.; VCH Publishers, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1991; Volume II, pp. 313–365. [Google Scholar]

- Dirac, P.A.M. Note on Exchange Phenomena in the Thomas Atom. Math. Proc. Camb. Philos. Soc. 1930, 26, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, J. Wave Mechanics, Advanced General Theory; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan, A.D.; Ball, M.A. Time-Dependent Hartree–Fock Theory for Molecules. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1964, 36, 844–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broeckhove, J.; Lathouwers, L.; Kesteloot, E.; Van Leuven, P. On the equivalence of time-dependent variational principles. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1988, 149, 547–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Endo, S.; Zhao, Q.; Li, Y.; Benjamin, S.C. Theory of Variational Quantum Simulation. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1812.08767v4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucar, J.; Meyer, D. Exact wave packet propagation using time-dependent basis sets. J. Chem. Phys. 1989, 90, 5566–5577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, S.A.; McLaurin, P.M.; Grimes, T.V.; Morales, J.A. Time-dependent density-functional theory method in the electron nuclear dynamics framework. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2010, 496, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deumens, E.; Öhrn, Y.; Weiner, B. Coherent state formulation of multiconfiguration states. J. Math. Phys. 1991, 32, 1166–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, T.B.; Koch, H. On the time-dependent Lagrangian approach in quantum chemistry. J. Chem. Phys. 1998, 108, 5194–5204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvaal, S. Variational formulations of the coupled-cluster method in quantum chemistry. Mol. Phys. 2013, 111, 1100–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvaal, S. Ab initio quantum dynamics using coupled-cluster. J. Chem. Phys. 2012, 136, 194109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, H. Classical Mechanics, 2nd ed.; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Deumens, E.; Ohrn, Y. Wavefunction phase space: An approach to the dynamics of molecular systems. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1997, 93, 919–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, A.; Ostlund, N.S. Modern Quantum Chemistry: Introduction to Advanced Electronic Structure Theory, 1st ed.; Dover Publications Inc.: Mineola, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Wybourne, B.G. Classical Groups for Physicists; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Barout, A.O.; Raczka, R. Theory of Group Representations and Applications; Polish Scientific Publishers: Warszaw, Poland, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Iachello, F. Lie Algebras and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- McLaurin, P.M.; Merritt, R.; Dominguez, J.C.; Teixeira, E.S.; Morales, J.A. Symmetry-breaking effects on time-dependent dynamics: Correct differential cross sections and other properties in H+ + C2H4 at ELab = 30 eV. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 5006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, J.C.; Kim, H.; Silva, E.D.; Pimbi, D.; Morales, J.A. Electron nuclear dynamics of time-dependent symmetry breaking in H+ + H2O at ELab = 28.5–200.0 eV: A prototype for ion cancer therapy reactions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25, 2019–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Beveren, E. Some Notes on Group Theory; University of Coimbra: Coimbra, Portugal, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cotton, F.B. Chemical Applications of Group Theory, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Interscience: London, UK, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Shampine, I.F.; Gordon, M.K. Computer Solution of Ordinary Differential Equations: The Initial Value Problem; W. H. Freeman: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).