Abstract

The exponentiated exponential distribution has received great attention from many statisticians due to its popularity, many applications, and the fact that it is an efficient alternative to many famous distributions such as Weibull and gamma distributions. Many statisticians have studied the mathematical properties of this distribution and estimated its parameters under different censoring schemes. However, it seems that the distribution of the random sum, the distribution of the linear combination, and the value of the reliability index, , in the case of unequal scale parameters, were not known for this distribution. Therefore, in this article, we present the saddlepoint approximation to the distribution of the random sum, the distribution of linear combination, and the value of the reliability index for exponentiated exponential variates. These saddlepoint approximations are computationally appealing, and numerical studies confirm their accuracy. In addition to the accuracy provided by the saddlepoint approximation method, it saves time compared to the simulation method, which requires a lot of time. Therefore, the saddlepoint approximation method provides an outstanding balance between precision and computational efficiency.

1. Introduction

The exponentiated exponential (EE) distribution was introduced by Gupta and Kundu [1]. It has become a prominent generalization of the classical exponential distribution. Its flexibility and asymmetrical structure enable more precise modeling of various real-world phenomena characterized by non-monotonic hazard functions, making it a valuable tool in many areas, such as reliability analysis, survival analysis, and actuarial science. The primary advantage of the EE distribution is its ability to model more complex lifetime behaviors compared to the standard exponential distribution, which assumes a constant hazard rate. In contrast, the EE distribution offers more shape flexibility, accommodating increasing and decreasing hazard rates. This makes it particularly useful for systems where the risk of failure or event occurrence varies over time, such as in biomedical research, engineering reliability, and ecological studies. Another significant benefit is that the EE distribution provides closed-form expressions for important characteristics like the cumulative distribution function (CDF), moments, moment-generating function (MGF), and reliability measures. This mathematical simplicity enhances its computational efficiency, making it suitable for both theoretical analysis and practical applications. Many authors have studied the EE distribution, among them: Gupta and Kundu [2,3], Zheng [4], Sarhan [5], Abdel-Hamid and Al-Hussaini [6], Chen and Lio [7], Ismail [8], Han and Kundu [9], Ateya and Mohammed [10], Pandey et al. [11], and Kabdwal et al. [12].

A random variable X is defined to follow the EE distribution if its probability density function (PDF) and CDF are expressed as:

and

This paper addresses unexplored aspects of the exponentiated exponential distribution, specifically, the distributions of the random sum, the linear combination of independent exponentiated exponential random variables, and the reliability index , particularly in cases with unequal scale parameters. It introduces and applies the saddlepoint approximation method to calculate these distributions and the reliability index. This is novel, as previous works have not focused on these aspects of the exponentiated exponential distribution. The saddlepoint approximation is highlighted as a computationally efficient alternative to exact simulation methods, offering the advantage of maintaining high accuracy while significantly reducing computation time. The key contributions of this study include bridging theoretical gaps in the exponentiated exponential (EE) distribution by deriving saddlepoint approximations for previously unexplored properties. The work demonstrates an effective balance between computational efficiency and precision, making it particularly valuable for applications that require rapid and accurate reliability assessments. Additionally, it provides a foundation for extending saddlepoint methods to more complex scenarios, such as bivariate distributions, paving the way for future research.

A random sum, or stopped sum, refers to the total obtained by summing a random number of random variables. This concept is widely applicable in many fields such as actuarial science, queuing theory, reliability engineering, and finance, where sums of random variables often come with a stopping rule defined by an independent random variable. Mathematically, let N be a discrete random variable indicating the stopping point, and let be independent and identically distributed random variables; then, the random sum is given by . It can effectively model a variety of real-world phenomena [13]. In actuarial science, random sums are used to model the total claim amount for insurance portfolios, where the number of claims is distributed (often as Poisson or Negative Binomial), and each claim amount represents a random variable. In queuing systems, random sums help evaluate total waiting times and service durations, offering insights for resource allocation and customer service optimization. In reliability engineering, random sums model the lifetime of a system that fails once a certain number of component failures occur, facilitating maintenance planning and replacement scheduling. In finance, random sums can represent cumulative returns on assets in a portfolio with investments made at random intervals, supporting risk management and strategic investment planning. For more applications of the random sum, see Rao et al. [14] and Malinovskii [15].

The distribution of a linear combination of n random variables is fundamental in statistics and probability theory. The linear combination is expressed as , where represents random variables, and are constants. This concept finds extensive applications across various fields, including finance, where portfolio returns are modeled as a linear combination of returns from individual assets [16]. In hydrology, the net flow from a reservoir basin is determined by subtracting the amount of water used for purposes such as domestic consumption and agriculture from the total rainfall in the area [17]. For more applications of the distribution of the linear combination of random variables, see Arellano and Gento [18], Nadarajah [17], Marques et al. [19], and Krishnamoorthy [20].

In the context of reliability, the stress–strength model illustrates the lifespan of a component characterized by a random strength and subjected to random stress . The component fails when the applied stress exceeds its strength while it continues to operate effectively whenever . Consequently, the reliability index indicates the likelihood of the component operating without failure. This model finds extensive applications in various engineering domains, including structural integrity assessments, the deterioration of rocket motors, static fatigue in ceramic materials, fatigue failures in aircraft structures, and the aging of concrete pressure vessels. For more details, see Weerahandi and Johnson [21], Kohansal [22], Kayal et al. [23], and Pakdaman et al. [24].

The saddlepoint approximation was first introduced to statistics by Daniels [25]. This approximation method provides an approach to approximate a density or mass function using its moment-generating or cumulant-generating function. Lugannani and Rice [26] later proposed a saddlepoint approximation to the CDF of continuous distributions. Daniels [27] introduced two continuity modifications for discrete distributions. Barndorff-Nielsen and Cox [28] developed a saddlepoint density approximation for conditional distributions, and Skovgaard [29] extended this with a double saddlepoint approximation for the CDF. The saddlepoint approximation is widely recognized for its exceptional accuracy in statistical computations, especially in approximating distributions that are challenging to derive precisely. This method achieves a high level of precision in approximating probabilities and reliability indices, often producing results that closely align with those obtained through exact methods. The saddlepoint approximation method stands out among asymptotic approximation methods due to its superior accuracy and robustness. While many asymptotic methods rely on large-sample assumptions that can lead to significant errors in small or moderate samples, the saddlepoint approximation delivers precise results even in these scenarios. It effectively captures the behavior of the distribution’s tail and central regions, where other asymptotic methods may struggle. For a comprehensive review and applications of saddlepoint approximations, refer to Butler [30]. For recent studies and advancements in saddlepoint approximation, see Alhejaili and Abd-Elfattah [31], Gatto [32], Abd El-Raheem and Abd-Elfattah [33,34], Meng et al. [35], Goodman [36], Abd El-Raheem et al. [37,38], Arevalillo [39], and Abd El-Raheem et al. [40,41].

This article discusses the saddlepoint approximations for the EE distribution in various contexts. Section 2 introduces the saddlepoint approximation to the Poisson-EE random sum distribution, accompanied by a simulation study (Section 2.1) and a numerical example (Section 2.2) to validate the results. Section 3 extends the analysis to a linear combination of EE random variables, presenting both a simulation study (Section 3.1) and a corresponding illustrative example (Section 3.2). Section 4 focuses on the saddlepoint approximation to the reliability index, , with a simulation study in Section 4.1 to evaluate its accuracy. Finally, Section 5 concludes the article by summarizing the findings and emphasizing the computational efficiency and accuracy of the proposed approximations.

2. Saddlepoint Approximation to the Poisson-EE Random Sum Distribution

In this section, the saddlepoint approximation to the Poisson-EE random sum distribution is derived. The Poisson-EE random sum is the sum of a random sample from the EE distribution with sample size, N, independent Poisson random variables.

The saddlepoint approximation of the PDF, , is given by [25]:

where is the cumulant generating function (CGF) of X, is the unique solution to the saddlepoint equation

The saddlepoint approximation of the CDF, , is given by [26]:

where and represent the CDF and PDF of the standard normal distribution, respectively, and is the mean of the distribution. Here, and .

Let and be the MGFs of N and X, respectively. It is easy to show that the MGF of is given by:

and its CGF is given by:

where and are the CGFs of N and X, respectively.

By replacing with in (3), the saddlepoint approximation to the PDF of is given by:

The saddlepoint approximation to the CDF of is given by:

where

and

with being the solution to the equation , and representing the sign of .

For the Poisson-EE random sum distribution, the CGF of is given by:

Thus, the saddlepoint equation is

where is the digamma function. The saddlepoint can be obtained by solving Equation (8) numerically using the Newton–Raphson method.

The saddlepoint approximations to PDF and CDF of the Poisson-EE random sum distribution are given by (5) and (6), respectively.

2.1. Simulation Study

In this section, a simulation study is performed to evaluate the accuracy of the saddlepoint method for approximating the distribution of the Poisson-EE random sum. To verify the accuracy of the saddlepoint method, its results must be compared with the exact value, but the exact value cannot be calculated analytically, so we approximate the exact value using the simulation method in which we generate values of , where each simulation involves generating a value N from a Poisson distribution and then generating N values from the EE distribution. Thus, the simulated (exact) value of can be obtained from the following formula:

where is the indicator function.

During the article, we use the term “exact value” to refer to the value approximated using the simulation method.

The simulation study is carried out according to the following three scenarios of the parameters of the EE distribution:

- Scenario I: and .

- Scenario II: and .

- Scenario III: and .

The proposed scenarios allow for studying different shapes of the hazard rate function of the distribution under study. This diversity ensures that the accuracy of the saddlepoint approximation is tested across a diverse set of conditions.

The procedures for approximating the CDF of the Poisson-EE random sum distribution using the simulation and saddlepoint methods are carried out according to Algorithm 1.

Table 1 presents both the exact values and the saddlepoint approximations of with the MSE of the saddlepoint approximation method for the different simulation scenarios. Moreover, the computing time in minutes for the simulation method (Time (exact)) and saddlepoint approximation method (Time (sadd)) are recorded and displayed in Table 1.

| Algorithm 1: Approximating the CDF of the Poisson-EE random sum distribution. |

|

Table 1.

Exact and saddlepoint approximation of the CDF of the Poisson-EE random sum distribution.

From the results in Table 1, we note the following key points:

- The saddlepoint approximation () closely matches the exact CDF () with minimal MSEs across all scenarios and parameter settings.

- The differences between the two methods are negligible, typically on the order of to , indicating high precision of the saddlepoint method.

- The simulation (exact) method requires significantly more computational time, ranging from approximately 99 to 182 min depending on the scenario and parameters. In contrast, the saddlepoint approximation is highly efficient, completing calculations in a fraction of a minute (approximately 0.013 to 0.018 min). This demonstrates the computational superiority of the saddlepoint method.

- In general, the saddlepoint approximation method provides an excellent balance between accuracy and computational efficiency, making it a convenient alternative to the simulation method for approximating the CDF of the Poisson-EE random sum distribution.

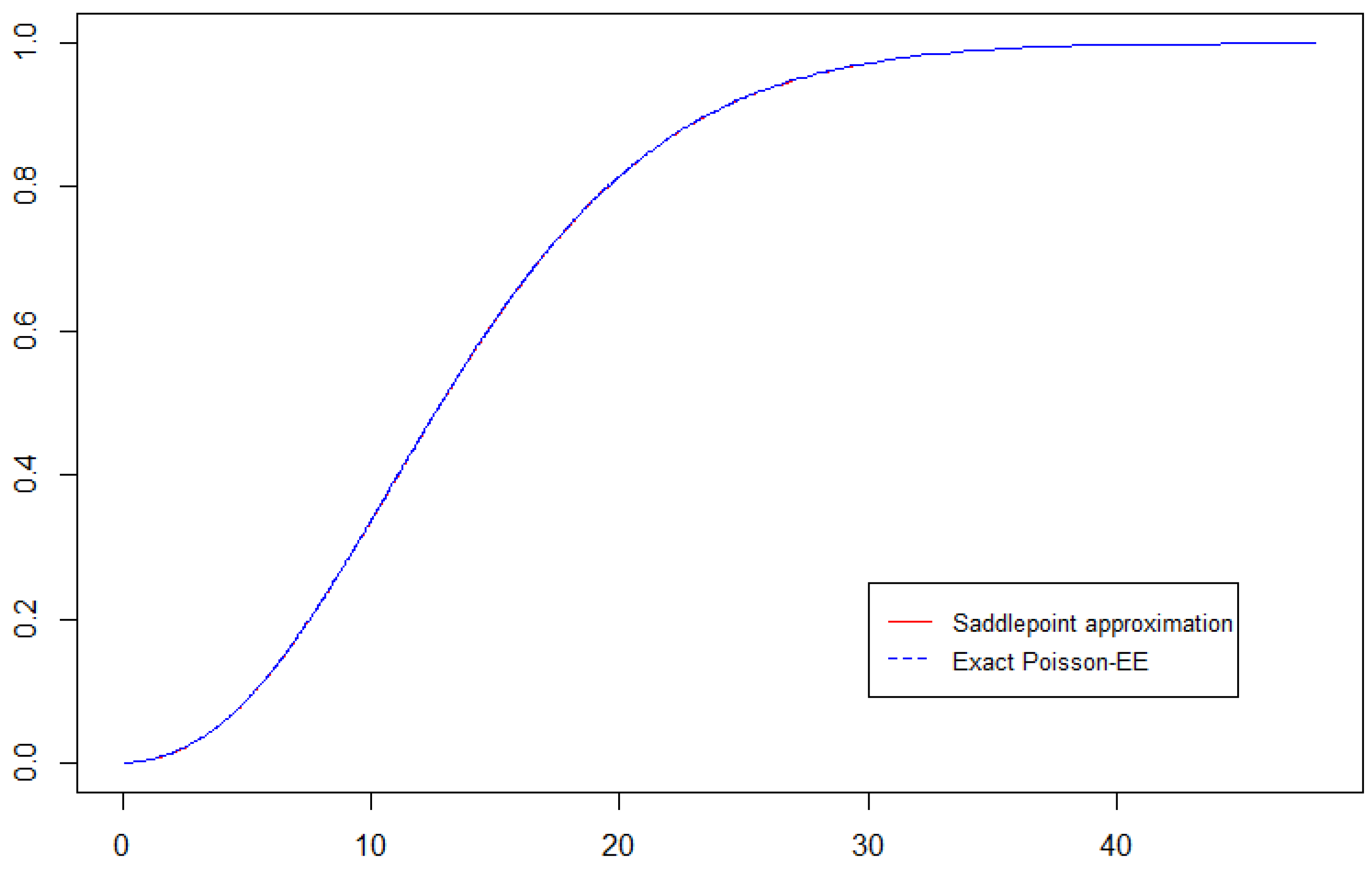

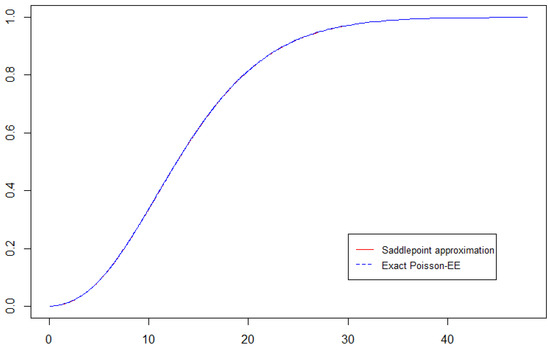

To demonstrate the accuracy of the saddlepoint approximation across a broad range of s values, a comparative plot of the exact CDF for the Poisson(8)-EE(0.8, 0.5) distribution alongside the saddlepoint approximation is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The exact CDF for Poisson-EE random sum (blue dashed line) with its saddlepoint approximation (red solid line).

Figure 1 demonstrates the accuracy of the saddlepoint approximation in approximating the CDF of the Poisson-EE random sum over a broad range of values. The tight overlap between the two curves indicates that the saddlepoint method provides an excellent approximation.

2.2. Numerical Example

To demonstrate the proposed procedures in this section, we use a synthetic dataset representing the total healthcare costs for patients in a hospital. The total cost of care for a patient’s stay in a hospital may depend on a random number of procedures or treatments, each with a randomly distributed cost. The total cost is thus a random sum. Assume that the number of procedures or treatments, N, that the patient undergoes is a random variable following a Poisson distribution and the cost of each treatment or medical procedure that the patient needs is a random variable, , following the EE distribution. Thus, we need to approximate the distribution of . The following data, 44.81, 67.03, 45.91, 8.01, 24.52, 47.67, 38.42, represent the cost of a random number of medical services that a patient receives in a hospital, where the number of medical services is generated from the Poisson distribution and the cost of each service is generated from the EE distribution.

The saddlepoint approximation is used to approximate at different values of s. The results of the saddlepoint approximation are presented in Table 2. The comparison between the second column (, the exact values) and the third column (, the saddlepoint approximations) of Table 2 reveals that the two methods produce results that are extremely close to each other across all values of s. The discrepancies between the exact values and the approximations are generally negligible, often differing only in the third or fourth decimal place.

Table 2.

Exact and saddlepoint approximation of for different values of s.

3. Saddlepoint Approximation to the Linear Combination of EE Random Variables

The linear combination of the EE random variables is given by:

where are independent EE random variables, with shape parameter and scale parameter , and the ’s are real constants.

The MGFs of and are respectively defined as:

and

Thus, the CGF of is given by:

Let be the PDF of , then the saddlepoint approximation is defined as:

where is the saddlepoint that satisfies th equation:

The saddlepoint can be obtained by solving Equation (15) numerically using the Newton–Raphson method.

Let be the CDF of , then the saddlepoint approximation is defined as

where and .

The saddlepoint approximations to the PDF and CDF of the sum of n independent EE random variables, , can be obtained as a special case of the saddlepoint approximations to the PDF and CDF of the linear combination, , when .

3.1. Simulation Study

In this section, we conduct a simulation study to assess the accuracy of the saddlepoint method for approximating the distribution of the linear combination of n independent EE random variables, .

The simulation study is conducted according to the following scenarios of the parameters of the EE distribution and the constants , .

- Scenario A: , , and , .

- Scenario B: , , and , .

- Scenario C: , , and , .

- Scenario D: , , and , .

- Scenario E: , , and , .

- Scenario F: , , and , .

Scenarios A, B, C, and D deal with the case of the linear combination, , while Scenarios E and F deal with the case of the sum, . The parameter values and are chosen to represent a diverse set of conditions, including both identically and non-identically random variable cases. Furthermore, the different values of and allow for considering the various shapes of the hazard rate function (increasing and decreasing) of the considered distribution. Moreover, the positive and negative values of the constant are assumed to study a diverse set of conditions. This diversity ensures that the accuracy of the saddlepoint approximation is tested across a range of realistic settings.

The processes for approximating the CDF of the linear combination of n independent EE random variables, , using the simulation and saddlepoint methods are performed following Algorithm 2 outlined below:

| Algorithm 2. Approximating the CDF of the linear combination of n independent EE random variables. |

|

Table 3 displays both the exact values and the saddlepoint approximation of . The exact CDF values for are determined by simulating values of and using the formula in (17). The MSE for the saddlepoint approximation method, along with the computation times in minutes for both the simulation and saddlepoint approximation methods, are also included in Table 3.

Table 3.

Exact and saddlepoint approximation of the CDF of the linear combination of independent EE random variables.

From the results in Table 3, we note the following main points:

- The saddlepoint approximation method closely approximates the exact CDF values () with very low MSEs, typically ranging between and . In most cases, the differences between the values of and are negligible. This indicates that the saddlepoint approximation method is a reliable substitute for the simulation method.

- The exact method is significantly more time-consuming, requiring approximately 68 to 189 min depending on the scenario and the value of n. The saddlepoint approximation is vastly more efficient, completing calculations in less than a minute, typically within 0.02 to 0.06 min.

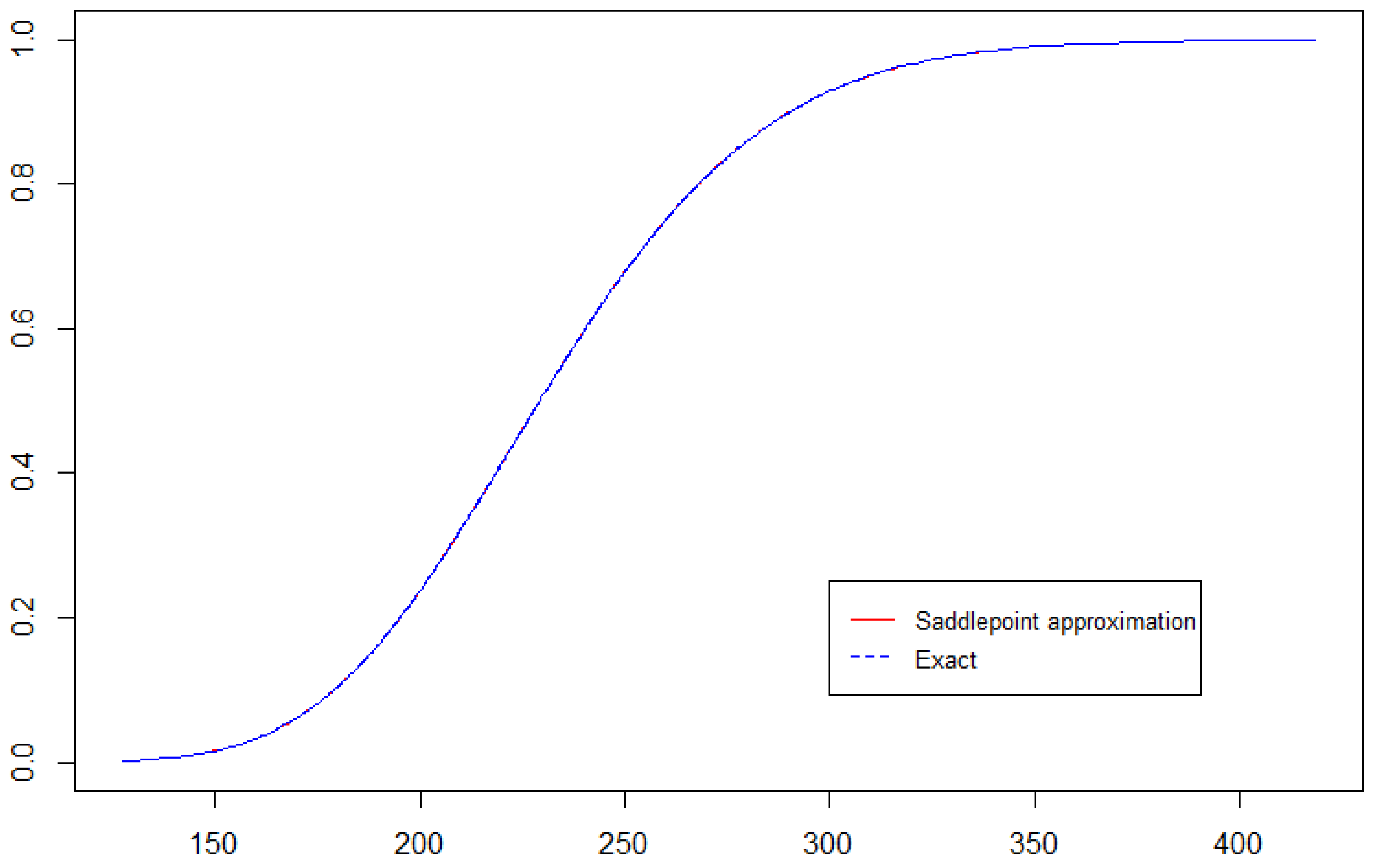

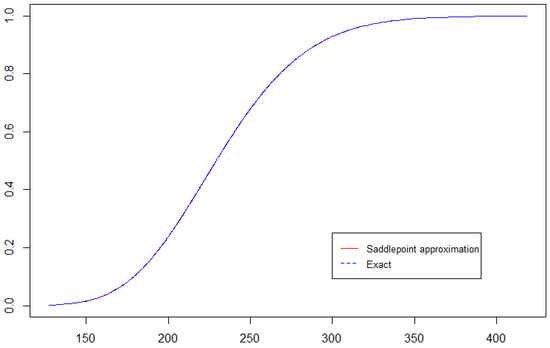

Figure 2 compares the exact CDF for the linear combination of independent EE random variables with its saddlepoint approximation. The graph shows that the saddlepoint approximation closely follows the exact CDF curve, which indicates that the saddlepoint approximation method provides a high degree of accuracy in approximating the distribution of the linear combination.

Figure 2.

The exact CDF for the linear combination (blue dashed line) with the corresponding saddlepoint approximation (red solid line) under Scenario C.

3.2. Illustrative Example

To illustrate the suggested procedures in this section, we assume an artificial dataset of daily rainfall accumulation where each day’s rainfall follows the EE distribution. When we accumulate these daily values over several days, we obtain a distribution of total rainfalls over this period. The following data, 3.08, 9.29, 9.10, 9.31, 14.77, 9.58, 1.05, 4.51, 10.01, 7.77, represent the daily rainfall depth in millimeters (mm) over the ten days generated from the EE distribution.

It may be necessary for meteorologists to calculate the probability that the total rainfall depth during a given period will not exceed a certain value, i.e., calculate , where is the daily rainfall that follows the EE distribution. The saddlepoint approximation in (16) is used to approximate at different values of s. The exact value of , along with the corresponding saddlepoint approximation for different values of s, are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Exact and saddlepoint approximation of for different values of s.

The comparison between the second column (, the exact values) and the third column (, the saddlepoint approximations) in Table 4 demonstrates that the values of and are highly similar for all tested values of s. The differences between the exact and approximate values are minimal, typically observed in the third or fourth decimal place. The saddlepoint approximation maintains accuracy across a wide range of s values, from 50 to 140. This consistency suggests the robustness of the saddlepoint method.

4. Saddlepoint Approximation to the Reliability Index

This section focuses on approximating , the probability that is fundamental to the stress–strength reliability model. In this context, denotes the strength of a component, while represents the stress applied to it, with both variables independently following EE distributions. The probability R reflects the likelihood that the component’s strength will exceed the applied stress, making it a crucial metric for assessing system reliability. This model is essential in reliability engineering for evaluating the capacity of components to withstand stress without failure.

Let ∼ and ∼ be independent random variables. We can express as:

The integral in (18) cannot generally be simplified to a closed-form expression for arbitrary values of and . Gupta and Kundu [42] derived an expression for for a certain special case when . In this section, we approximate using saddlepoint approximation for any values of , , and .

The probability R in (18) can be written as , where . Thus, the CGF of D is

Thus, the saddlepoint approximation to the probability is

where and .

4.1. Simulation Study

To illustrate the accuracy of the saddlepoint method for approximating the reliability index , we conduct a simulation study in which the variables and are generated from and , respectively. After that, the saddlepoint approximation in (20) is used to approximate the reliability index .

Table 5 contains the exact and saddlepoint approximation of the reliability index for different values of the parameters and , . The exact value of the reliability is obtained by simulating values of . In each simulation, a random variable is generated from the EE distribution. Consequently, the exact value of the reliability index is

Table 5.

Exact and saddlepoint approximation of .

Across all entries in Table 5, the values of R and are very close, indicating that the saddlepoint approximation provides an excellent approximation of . The deviations between R and are minimal, often within a difference of . This highlights the reliability of the saddlepoint method for approximating R. The saddlepoint approximation is highly effective in approximating the probability , with negligible errors relative to the exact values.

5. Conclusions

This article addresses important gaps in the study of the exponentiated exponential distribution by presenting saddlepoint approximations for the distribution of the random sum and the linear combination of independent exponentiated exponential random variables. Furthermore, this article uses the saddlepoint method to approximate the reliability index , particularly in cases with unequal scale parameters. The saddlepoint approximations are shown to be computationally efficient and accurate, as confirmed by numerical and simulation studies. In addition to the fact that the saddlepoint approximations are very accurate, they are calculated quickly compared to the simulation method (exact). Thus, the saddlepoint approximation method offers an excellent trade-off between accuracy and computational efficiency. It is a computationally efficient alternative for scenarios where exact calculations may be challenging or time-consuming.

All numerical results in this article were obtained using the R programming language. The library “nleqslv” in R was used to solve the saddlepoint equation. This library is a powerful tool for solving non-linear equations, but like any numerical solver, it has limitations related to convergence and reliance on good initial guesses. The R computation codes are available from the authors upon request. Future research could focus on the distribution of the bivariate random sum and bivariate linear combinations of independent exponentiated exponential random variables. The bivariate saddlepoint approximation [43] is a useful tool to extend the results of the current work to the bivariate case.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.E.-R.M.A.E.-R.; methodology, A.E.-R.M.A.E.-R.; software, A.E.-R.M.A.E.-R.; validation, A.E.-R.M.A.E.-R.; formal analysis, A.E.-R.M.A.E.-R.; investigation, A.E.-R.M.A.E.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, M.H.; writing—review and editing, M.H.; supervision, M.H.; project administration, M.H.; funding acquisition, M.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The second author thanks the Deanship of Scientific Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University for funding this work through a Large Research Project under grant number RGP2/398/45.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gupta, R.D.; Kundu, D. Theory & Methods: Generalized exponential distributions. Aust. N. Z. J. Stat. 1999, 41, 173–188. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, R.D.; Kundu, D. Exponentiated exponential family: An alternative to gamma and Weibull distributions. Biom. J. J. Math. Methods Biosci. 2001, 43, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.D.; Kundu, D. On the comparison of Fisher information of the Weibull and GE distributions. J. Stat. Plan. Inference 2006, 136, 3130–3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G. On the Fisher information matrix in type II censored data from the exponentiated exponential family. Biom. J. J. Math. Methods Biosci. 2002, 44, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarhan, A.M. Analysis of incomplete, censored data in competing risks models with generalized exponential distributions. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2007, 56, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Hamid, A.H.; AL-Hussaini, E.K. Estimation in step-stress accelerated life tests for the exponentiated exponential distribution with type-I censoring. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2009, 53, 1328–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.G.; Lio, Y. Parameter estimations for generalized exponential distribution under progressive type-I interval censoring. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2010, 54, 1581–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.A. Estimating the generalized exponential distribution parameters and the acceleration factor under constant-stress partially accelerated life testing with type-II censoring. Strength Mater. 2013, 45, 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Kundu, D. Inference for a step-stress model with competing risks for failure from the generalized exponential distribution under type-I censoring. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2015, 64, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateya, S.F.; Mohammed, H.S. Statistical inferences based on an adaptive progressive type-II censoring from exponentiated exponential distribution. J. Egypt. Math. Soc. 2017, 25, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Kaushik, A.; Singh, S.K.; Singh, U. On the estimation problems for exponentiated exponential distribution under generalized progressive hybrid censoring. Austrian J. Stat. 2021, 50, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabdwal, N.C.; Azhad, Q.J.; Hora, R. Statistical inference of the exponentiated exponential distribution based on progressive type-II censoring with optimal scheme. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2024, 15, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N.L.; Kemp, A.W.; Kotz, S. Univariate Discrete Distributions; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; Volume 444. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, C.R.; Srivastava, R.; Talwalker, S.; Edgar, G.A. Characterization of probability distributions based on a generalized Rao-Rubin condition. Sankhyā Indian J. Stat. Ser. A 1980, 42, 161–169. [Google Scholar]

- Malinovskii, V.K. Limit theorems for stopped random sequences. I: Rates of convergence and asymptotic expansions. Theory Probab. Its Appl. 1994, 38, 673–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popović, B.V.; Mijanović, A.; Genç, A.İ. On linear combination of generalized logistic random variables with an application to financial returns. Appl. Math. Comput. 2020, 381, 125314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadarajah, S. Exact distribution of the linear combination of p Gumbel random variables. Int. J. Comput. Math. 2008, 85, 1355–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano-Valle, R.B.; Genton, M.G. On the exact distribution of linear combinations of order statistics from dependent random variables. J. Multivar. Anal. 2007, 98, 1876–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, F.J.; Coelho, C.A.; De Carvalho, M. On the distribution of linear combinations of independent Gumbel random variables. Stat. Comput. 2015, 25, 683–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy, K. Modified normal-based approximation to the percentiles of linear combination of independent random variables with applications. Commun. Stat.-Simul. Comput. 2016, 45, 2428–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerahandi, S.; Johnson, R.A. Testing reliability in a stress-strength model when X and Y are normally distributed. Technometrics 1992, 34, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohansal, A. On estimation of reliability in a multicomponent stress-strength model for a Kumaraswamy distribution based on progressively censored sample. Stat. Pap. 2019, 60, 2185–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayal, T.; Tripathi, Y.M.; Dey, S.; Wu, S.J. On estimating the reliability in a multicomponent stress-strength model based on Chen distribution. Commun. Stat.-Theory Methods 2020, 49, 2429–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakdaman, Z.; Shekari, M.; Zamani, H. Stress–strength reliability of a failure profile with cmponents operating under the internal environmental factors. Int. J. Reliab. Qual. Saf. Eng. 2023, 30, 2350019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, H.E. Saddlepoint approximations in statistics. Ann. Math. Stat. 1954, 25, 631–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugannani, R.; Rice, S. Saddlepoint approximation for the distribution of the sum of independent random variables. Adv. Appl. Probab. 1980, 12, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, H.E. Tail probability approximations. Int. Stat. Rev. 1987, 55, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barndorff-Nielsen, O.; Cox, D.R. Edgeworth and saddle-point approximations with statistical applications. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 1979, 41, 279–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skovgaard, I.M. Saddlepoint expansions for conditional distributions. J. Appl. Probab. 1987, 24, 875–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. Saddlepoint Approximations with Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Alhejaili, A.D.; Abd-Elfattah, E.F. Saddlepoint approximations for stopped-sum distributions. Commun. Stat.-Theory Methods 2013, 42, 3735–3743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatto, R. Saddlepoint approximation for data in simplices: A review with new applications. Stats 2019, 2, 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Raheem, A.M.; Abd-Elfattah, E.F. Weighted log-rank tests for clustered censored data: Saddlepoint p-values and confidence intervals. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2020, 29, 2629–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd El-Raheem, A.M.; Abd-Elfattah, E.F. Log-rank tests for censored clustered data under generalized randomized block design: Saddlepoint approximation. J. Biopharm. Stat. 2021, 31, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, D.; Yang, S.; Lin, T.; Wang, J.; Yang, H.; Lv, Z. RBMDO using gaussian mixture model-based second-order mean-value saddlepoint approximation. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2022, 132, 553–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, J. Asymptotic accuracy of the saddlepoint approximation for maximum likelihood estimation. Ann. Stat. 2022, 50, 2021–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Raheem, A.M.; Hosny, M.; Abd-Elfattah, E.F. Statistical inference of the class of non-parametric tests for the panel count and current status data from the perspective of the saddlepoint approximation. J. Math. 2023, 2023, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Raheem, A.M.; Kamal, K.S.; Abd-Elfattah, E.F. p-values and confidence intervals of linear rank tests for left-truncated data under truncated binomial design. J. Biopharm. Stat. 2023, 34, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arevalillo, J.M. On the empirical approximation to quantiles from Lugannani–Rice saddlepoint formula. Stat. Probab. Lett. 2024, 209, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Raheem, A.M.; Shanan, I.A.; Abd-Elfattah, E.F. Saddlepoint approximations for the p-values and probability mass functions of some bivariate sign tests. Commun. Stat.-Theory Methods 2024, 53, 8942–8953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Raheem, A.M.; Shanan, I.A.; Hosny, M. Saddlepoint approximation of the p-values for the multivariate one-sample sign and signed-rank tests. AIMS Math. 2024, 9, 25482–25493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.D.; Kundu, D. Generalized exponential distribution: Existing results and some recent developments. J. Stat. Plan. Inference 2007, 137, 3537–3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. Saddlepoint approximations for bivariate distributions. J. Appl. Probab. 1990, 27, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).