Abstract

This study investigates natural convection in porous media under non-standard asymmetric boundary conditions, focusing on flow and heat transfer. Numerical simulations were performed to analyze flow patterns, temperature distributions, and heat transfer for varying Rayleigh numbers, porosities, and internal heat generation rates. The results indicate that increasing the Rayleigh number significantly enhances heat transfer, with Nusselt numbers ranging from 5.72 to 11.02 across all cases. Higher internal heat generation and porosity lead to more uniform temperature distributions and larger convection cells, with Nusselt numbers increasing by up to 16% compared to the base case. These findings demonstrate that non-uniform boundary conditions, such as linearly cooled sidewalls, have a significant effect on heat transfer in porous media, offering insights for improving thermal management in materials with complex boundary conditions.

1. Introduction

Concrete remains the backbone of modern infrastructure because of its affordability, durability, and versatility in structural engineering. Yet despite its solid appearance, concrete is fundamentally a porous composite material. It contains capillary pores, gel pores, and microcracks that form an interconnected network through which water and vapor can migrate. The ability of heat to enter, be stored, and move through this network plays a decisive role in the thermal performance, durability, and overall service life of concrete structures [1,2,3]. Porous concretes, such as lightweight or pervious varieties, intensify these interactions because their high porosity increases their sensitivity to temperature gradients.

Natural convection is a widely studied phenomenon in fluid dynamics, typically observed in enclosures where temperature differences drive buoyant forces. Most of the foundational work in this field has focused on simple boundary conditions—such as isothermal or uniformly heated walls, in both closed and open systems. However, more recent investigations have shifted attention to non-standard boundaries, which introduce complexities that influence the flow and heat transfer in unique ways. One strand of research considers spatially varying wall temperatures. In a pure fluid context, imposing sinusoidal or otherwise non-uniform temperature distributions on sidewalls or bottom walls leads to markedly different flow and heat-transfer patterns compared to uniform-wall cases. For example, several studies observe asymmetric circulation cells, multiple vortices, and non-uniform wall heat flux under non-uniform boundary conditions. Extending this to porous media, Ref. [4] studied natural convection in a square cavity saturated with a porous medium where one vertical wall had a spatial (sinusoidal) temperature variation while the opposite wall was kept at a uniform cold temperature. They found that the average Nusselt number depends sensitively on the amplitude and wave number of the temperature variation: increasing the amplitude increases wall heat flux, but increasing the number of undulations (wave number) tends to reduce the overall heat flux.

Later work by Chakkingal et al. [5] compared fluid-only cavities and porous-media filled cavities under non-uniform sidewall wall-temperature distributions. They reported that porous media respond differently: in the porous-filled cavity maximum heat transfer tends to concentrate near lower portions of the cold wall, while upper regions remain more conduction-dominated due to damped fluid motion from the porous matrix. These studies collectively underline that non-standard boundary conditions in porous media introduce complex interactions between buoyancy, conduction, and flow resistance, leading to flow suppression, localized heat flux, and non-uniform thermal fields.

The study of natural convection in porous media is central to understanding heat transfer mechanisms in a variety of applications, such as thermal management in building materials. Natural convection is driven by buoyant forces generated from temperature differences within the medium. In this study, we focus specifically on thermal convection in dry porous media under non-standard boundary conditions. These non-uniform boundary conditions, such as linearly cooled sidewalls, can lead to complex flow and heat transfer patterns that are critical for understanding the thermal behavior of porous materials in practical applications [6,7,8,9,10]. The influence of these coupled processes is particularly severe in hot and humid climates. For example, in Douala, Cameroon, buildings experience ambient relative humidity ranging between 55% and 96% and temperatures between 23 and 32 °C. Under such conditions, reinforced concrete walls exhibit visible degradation including blackened facades, moss growth, slab subsidence, and reinforcement corrosion from persistent capillary rise [3]. Indoors, comfort is compromised as heat absorbed during daytime in thick concrete walls diffuses inward at night, raising room temperatures and causing discomfort during sleeping hours [3]. These case studies emphasize that thermal processes in porous concrete contribute to durability problems for structures and energy and comfort challenges for occupants, particularly under varying temperature conditions. Heat transfer in porous materials occurs through a combination of conduction, convection, and buoyant fluid movement. Temperature gradients induce fluid motion, influencing the flow dynamics and thermal distribution within the material. Conduction dominates in static fluids, while convection plays a role in more dynamic thermal systems [11,12,13,14].

Given this complexity, analytical solutions are rarely possible and numerical methods are essential. Among these, the finite element method (FEM) has become the dominant approach in engineering applications because it can represent irregular geometries, nonlinear constitutive laws, and strongly coupled fields. Ref. [6] developed an FEM model for coupled heat and carbonation in concrete that matched experimental results. Authors of Ref. [15] simulated coupled heat and water transport in masonry including interface effects, while Ref. [16] determined transport and storage parameters of bricks exposed to environmental conditions. These and similar works demonstrated the flexibility of FEM in hygrothermal problems. Recent contributions in Ref. [1] advanced FEM formulations further by analyzing hydro-thermal convection in porous media using Darcy’s law coupled with an advection–diffusion energy equation. They employed Taylor–Hood finite elements to stabilize velocity–pressure solutions and used iterative decoupling between momentum and energy equations. Their results showed that variations in hydraulic resistivity and thermal diffusivity significantly affect convective heat transfer, underscoring the role of property gradients in porous materials.

Besides bespoke codes, commercial multiphysics platforms have been increasingly adopted. COMSOL Multiphysics, for instance, offers dedicated interfaces for heat transfer in porous media and for moisture transport, which can be coupled with mechanical and chemical phenomena. Ref. [3] used COMSOL 6.0 to simulate coupled heat and moisture transfer in the concrete walls of a real residential building in Douala. Their three-dimensional model incorporated geographic orientation, solar radiation, and local climate boundary conditions. The simulations revealed that moisture remains trapped in the core of the concrete blocks for extended periods, which accelerates reinforcement corrosion. Furthermore, the heat stored in walls was shown to diffuse inward at night, producing thermally uncomfortable indoor conditions. Furthermore, the heat stored in walls was shown to diffuse inward at night, producing thermally uncomfortable indoor conditions. This work represents one of the first COMSOL-based simulations of heat transfer in full-scale buildings in tropical climates, highlighting both the risks to durability and the importance of realistic modeling.

Other numerical approaches such as lattice Boltzmann methods, finite difference and finite volume schemes, and pore-network models have also been applied to porous concrete and building materials [17,18,19,20]. Lattice Boltzmann methods allow direct pore-scale simulation of moisture infiltration and permeability, while pore-network models capture connectivity effects. However, FEM remains the most widely used in structural engineering practice due to its versatility and integration into multiphysics packages. Applications range from predicting chloride ingress and freeze–thaw durability to modeling fire exposure and curing. For instance, moisture transport controls chloride penetration and carbonation, leading to reinforcement corrosion, while heat and moisture distributions determine internal pore pressures during fire, influencing spalling risk [20,21,22,23]. During curing, hydration heat release interacts with moisture diffusion, influencing cracking and strength development. In building energy and comfort studies, FEM simulations have been used to evaluate thermal efficiency of lightweight and modified concretes, with potential energy savings in tropical climates [13,24,25].

The thermal–fluid behavior of enclosures with sidewalls that are isothermal at unequal temperatures and horizontally adiabatic boundaries is well established [26]. By comparison, scenarios with more intricate boundary conditions—such as an obliquely oriented imposed temperature gradient rather than one strictly horizontal or vertical, have been explored far less.

Ref. [27] used numerical simulation to examine buoyancy-driven flow in a rectangular cavity where the entire lower boundary was kept cold and one sidewall was heated. Ref. [28] analyzed a configuration with a uniformly heated floor and vertical walls maintained at a constant cold temperature. Authors of Ref. [29] investigated steady, two-dimensional natural convection in a rectangular cavity with a left wall prescribed a linear temperature variation, cooled top and right boundaries, and a uniformly heated base. Their results showed that weak natural convection diminishes the heat load on the cold walls and, for any aspect ratio, there exists a critical Rayleigh number at which this load is minimized.

From the reviewed literature, the following gaps and under-explored areas emerge, aligning closely with the motivation of the present study. Most works use sinusoidal or piecewise/non-uniform heating, but cases with simple linear gradients along a wall (e.g., a sidewall cooled linearly with vertical coordinate) are rare. This type of boundary condition, simpler than sinusoidal variation, but more realistic than uniform wall temperature, could reveal different and practically relevant convection regimes. Further, while some studies address non-uniform boundaries, and others internal heat generation or conjugate conduction, very few combine all factors simultaneously. For materials like concrete or building envelopes, where internal heat generation, porous structure, and complex boundary conditions can co-occur, this combination is especially relevant. Many prior works focus on specific parameter sets (e.g., certain Darcy number, Rayleigh number) without exploring broad parameter ranges that cover conduction–convection transition, varying porous resistance, and varying boundary non-uniformity. Idealized walls (isothermal, adiabatic) remain common; few studies incorporate wall conduction, finite wall thickness or conjugate heat transfer, though these are important when the enclosure walls themselves are materials with thermal mass, like concrete or related materials. Together, these gaps justify a focused investigation of natural convection in porous media with non-standard boundary conditions, for instance, with a linearly cooled sidewall, internal heat generation, realistic material properties and porous resistance, to shed light on convection regimes, flow topology, and heat transfer behavior in conditions relevant to engineering or building applications.

In the present study, we consider an enclosure packed with a fluid-saturated porous matrix in which heat is generated volumetrically as a function of temperature. Classical studies typically relied on Darcy’s law, appropriate for slow filtration and neglecting inertia and wall-adjacent phenomena (collectively termed non-Darcy effects). The methodology and results of the present study are developed in detail in the sections that follow.

2. Physical Model

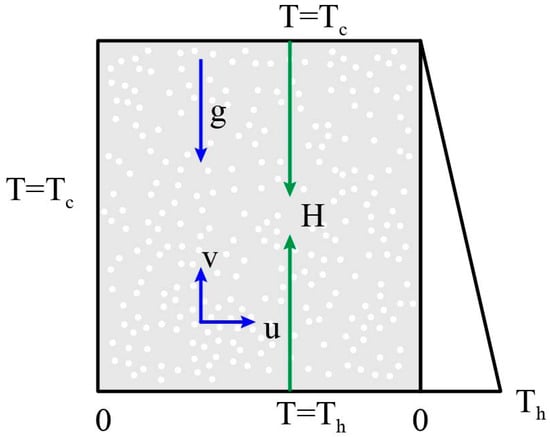

Consider a rectangular cavity of height packed with a fluid-saturated porous matrix (see Figure 1). The top and left boundaries are kept at a uniform cold temperature . Along the right wall, the temperature equals at the bottom and decreases linearly to at the top, while the bottom wall is maintained isothermally at . The thermal condition near the lower-right corner needs special treatment: in the reactor motivating this model, a narrow clearance of height (about 5–10 mm) between the base and the right wall is filled with a sodium deposit. Within this slot, the temperature is assumed to vary linearly from to over a small nondimensional distance . The formulation also includes temperature-dependent volumetric heating within the flow region.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the porous enclosure and boundary conditions. The structure of height is filled with a fluid/porous medium; gravity acts downward. The bottom wall is isothermal at , the top and left walls are isothermal at , and the right wall is linearly cooled from at the bottom to at the top. All boundaries are impermeable with no-slip velocity ().

The physical model considers a narrow gap where sodium deposition occurs, with a linear temperature gradient applied to the right wall. This setup mimics conditions found in certain reactor environments, such as those used in thermal management or heat exchangers.

To evaluate the applicability of the Darcy/Brinkman model, we now explicitly compare the relevant scales in the system:

- represents the height of the system;

- is the width of the narrow gap where sodium deposition occurs;

- is the overall height of the porous material.

The relationship between these dimensions is critical for understanding whether the local gap introduces flow regimes that may not be well-described by the averaged porous model. Specifically, the gap width may be sufficiently small relative to , showing that local effects (such as sodium deposition and micro-scale fluid dynamics) could lead to deviations from the Darcy/Brinkman approximation, which assumes a relatively uniform flow within the porous medium. In these cases, a more detailed micro-scale model may be needed to capture the non-uniform flow behavior near the gap. However, in the model, the gap is not included in the calculation domain as a porous medium, and therefore the question of the local applicability of the Darcy/Brinkman model pertains to a more detailed formulation, which is beyond the scope of this article.

The heat generation rate per unit volume, , is taken as:

Here, denotes the constant coefficient for volumetric heat generation. As noted by Vajravelu and Hadjinicolaou [15], this expression approximates certain exothermic situations in which thermal energy is released at the surface and conducted into the cavity. We analyze a laminar flow of a Newtonian, incompressible fluid with constant properties. Buoyancy is modeled using the standard Boussinesq approximation. Gravity acts in the direction indicated in Figure 1. Under these assumptions, the governing two-dimensional Cartesian conservation equations for continuity, momentum, and energy are:

Let and be the velocity components in the - and -directions. Time is denoted by ; is the fluid pressure; is the volumetric thermal expansion coefficient; and is the permeability of the porous matrix. The quantities , , and denote, respectively, the fluid density, thermal diffusivity, and specific heat at constant pressure. In this study, inertia associated with flow through the porous medium is omitted from the momentum equations, and viscous dissipation is neglected in the energy balance. In Equations (3) and (4), measures the permeability of the porous bed (modeled as a packed array of spheres) and is given by:

Let denote the diameter of a solid sphere, and let be the porosity of the porous matrix, defined by:

Here, is the fluid volume contained within the control region of size .

The equations of motion in the porous medium are written using the Darcy-Boussinesq type formulation with the term , where is the permeability and is the kinematic viscosity. This model assumes a steady-state, incompressible flow, and neglects inertial effects, making it valid for low Reynolds numbers. Although the text mentions non-Darcy effects, these effects, typically associated with Forchheimer terms that account for inertial forces, are excluded in the current model. The exclusion is justified as the Rayleigh number of , which corresponds to typical building scales and thermal conditions, results in a low Reynolds number where inertial forces are negligible compared to viscous forces. Specifically, for Ra = 105, the Reynolds number remains sufficiently small (typically less than 10) such that the Darcy approximation is valid.

To further quantify this, we estimate the critical porosity and Darcy number for which the non-Darcy effects can be neglected. For typical building materials with porosities in the range of 0.3 to 0.5, the Darcy number (Da) is generally small (on the order of to ) under these conditions. In such cases, the inertial/Forchheimer terms do not significantly influence the flow behavior, and the Darcy-Boussinesq model provides an adequate description of the flow and heat transfer in the system.

We adopt the following nondimensional scalings for the variables and coordinates:

Substituting these dimensionless dependent and independent variables into Equations (3)–(5) yields the nondimensional governing equations:

where

denotes the vorticity and the stream function, with their definitions given by:

Here:

The nondimensional initial and boundary conditions are specified in the following:

where represents the gap width at the lower-right corner. To solve the governing relations (Equations (7) and (8)), we apply an upwind finite-difference discretization coupled with a successive over-relaxation (SOR) scheme for the iterations. The key nondimensional groups in this study are the Rayleigh number , the Prandtl number , the porosity measure , and the volumetric heat-generation parameter . The vertical grid spacing is defined by (with nodes in the -direction) and is taken as .

Once the temperature field has been computed, the heat flux from each boundary follows directly. The nondimensional local heat flux at a wall is , with the outward normal. Consequently, the nondimensional heat transfer rate per unit depth for the left vertical wall is obtained by integrating this normal derivative along the wall height:

All simulations began from quiescent conditions with a uniform (mean) temperature field. To assess spatial resolution effects for the thermally driven cavity at the stated parameters, we tested uniform grids of , , and nodes; representative outcomes are summarized in Table 1. Balancing accuracy and cost, the mesh was adopted for the runs reported below.

Table 1.

Grid-independence assessment: stream function values for , across multiple mesh resolutions.

This study investigates natural convection in porous materials under non-standard boundary conditions, focusing on flow and heat transfer. Numerical simulations were performed to analyze flow patterns, temperature distributions, and heat transfer for varying Rayleigh numbers, porosities, and internal heat generation rates. In selecting the Rayleigh number Ra = 105, we considered typical building dimensions (e.g., height = 3 m) and temperature differences (e.g., 10–15 °C) in tropical climates. For these conditions, Ra = 105 is a representative value for medium to large-scale building structures where natural convection is significant.

To justify the use of Prandtl number (Pr = 0.7), we note that this value is appropriate for air at room conditions. The Prandtl number for air typically ranges around 0.7 at room temperature, which reflects the thermal diffusivity and kinematic viscosity of air. Given that air is the working fluid in our simulations, this value of Pr is a valid approximation for the study, making it suitable for the thermal convection in building-scale applications.

We simulate natural convection in porous media using the Rayleigh number (Ra) and Prandtl number (Pr) as key dimensionless parameters. The Rayleigh number is defined as:

where is the gravitational acceleration, is the thermal expansion coefficient, is the temperature difference, is the characteristic length (building height), is the kinematic viscosity, and is the thermal diffusivity. For typical building dimensions (e.g., height = 3 m) and temperature differences (10–15 °C) in tropical climates, the calculated Rayleigh number is approximately 105, making this a reasonable approximation for our simulations.

Additionally, the Prandtl number for air at room temperature is approximately 0.7, which is valid for the conditions of this study. This value is commonly used for natural convection studies involving air as the working fluid.

Numerical Method

The numerical simulations are performed using an upwind finite difference method (FD) for the convective terms and Successive Over-Relaxation (SOR) for solving the pressure-velocity coupling. The time integration scheme used is implicit, and the stationarity criterion is defined as the change in temperature or velocity between successive time steps being less than a threshold of .

The coupling scheme for the pressure-velocity is based on the ψ–Ω method, where the velocity components are solved for at each iteration, and the pressure is obtained from the Helmholtz equation for the stream function.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Validation

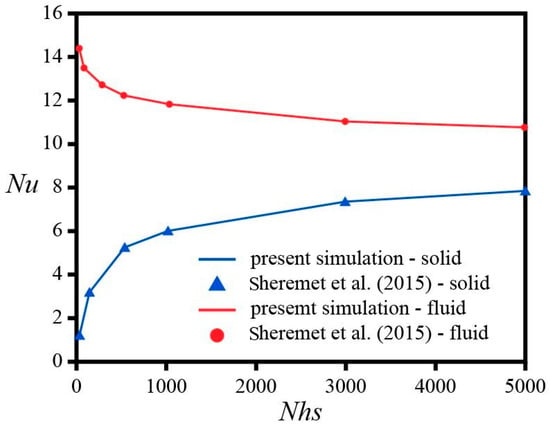

We validated our solver by repeating the differentially heated square porous cavity examined by [30], using the Darcy–Boussinesq formulation. The interphase heat-transfer parameter was varied to assess fluid–solid coupling strength. Their study defines as a dimensionless measure of interphase heat exchange, proportional to , and reports phase-averaged Nusselt numbers for both the fluid and the solid matrix. Figure 2. compares our predictions with the values from ref. [30]. The agreement is excellent for both phases across the explored range. The close overlap between our curves and those of [30] confirms that the present solver accurately simulates flow and heat transfer in porous-cavity convection. This builds confidence in our predictions for the parameter regimes explored in the rest of the paper.

Figure 2.

Validation of the present LTNE model against ref. [30]: Averaged Nusselt numbers versus for the fluid (red) and the solid matrix (blue). Markers: ref. [30]; lines: present simulation.

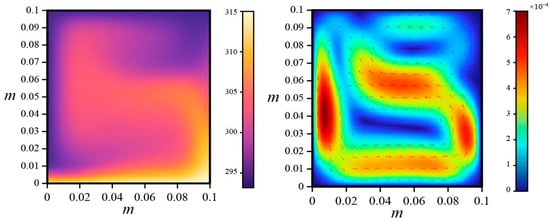

Figure 3 in left panel shows the dimensional temperature field within the square enclosure subject to a hot base, a cold lid and left wall, and a right wall linearly cooled from bottom to top. A warm core occupies the lower–right interior, while low temperatures wrap the lid and the upper portion of the right boundary. The basal boundary layer is thin and hottest near the bottom–right junction, where the buoyant plume forms and detaches. As the right wall temperature decreases with height, isotherms bend upward and then sweep leftward beneath the cold lid; the field becomes progressively cooler toward the upper left, consistent with a descending return layer along the uniformly cold sidewall. The overall pattern indicates that the dominant temperature drop occurs between the warm plume region and the cold lid and upper right boundary, with comparatively weaker gradients over the left side of the bottom wall.

Figure 3.

Temperature and velocity fields in the square enclosure at (). Thermal boundaries: bottom wall at ; top and left walls at ; right wall linearly cooled from to (left) Temperature distribution (K) showing a warm core near the bottom–right and cooling beneath the lid and upper right wall. (right) Velocity magnitude (with vectors) showing circulations.

Figure 3, right panel, presents the velocity magnitude with superposed arrows. The flow organizes into a single clockwise circulation: fluid accelerates along the lower portion of the right wall as the plume rises, turns beneath the lid, and descends as a narrow, high-speed layer adjacent to the cold left wall before closing the loop along the bottom. Peak velocities occur in these near-wall boundary layers—rising near the lower right and descending along the left wall—while the cavity interior exhibits slower, more uniform motion. The turning region under the right half of the lid shows elevated speeds associated with plume impingement and lateral sweep, whereas velocities decay toward the upper left where cooled fluid settles and the boundary layer thickens. This velocity–temperature pairing confirms that heat extraction is concentrated beneath the right side of the lid and in the upper segments of the vertical boundaries, with advection from the hot base feeding the plume and conduction dominating in corner regions remote from the main loop.

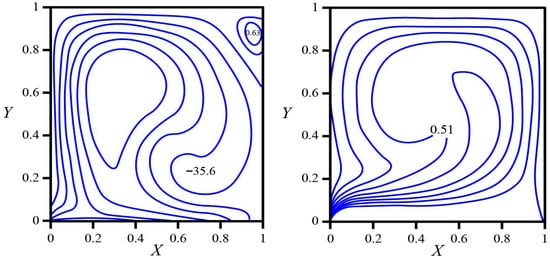

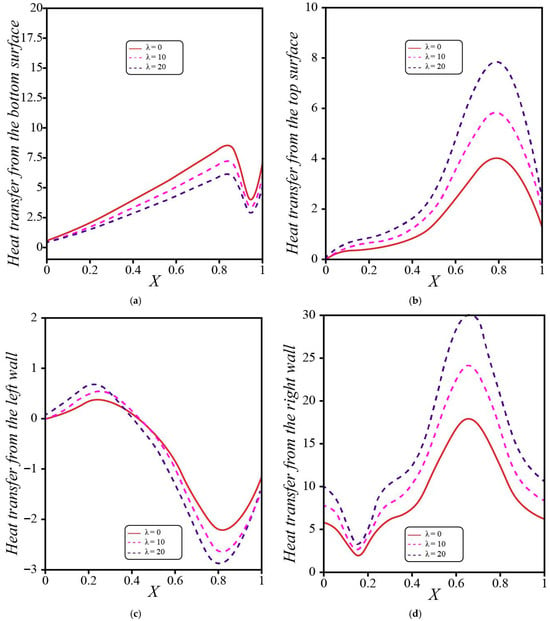

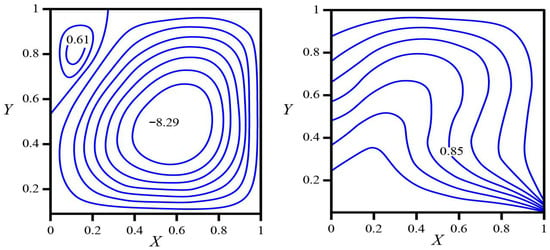

3.2. Flow and Thermal Fields for λ = 0 at Ra = 105 (Pr = 0.7, γ = 0) with a Linearly Cooled Right Wall

Figure 4 depicts the steady natural-convection fields in a square cavity for , , , and with mixed thermal boundary conditions: the bottom wall is held at ; the top and left walls are maintained at ; and the right wall temperature decreases linearly from at the bottom to at the top. The flow organizes into a single dominant clockwise vortex that fills most of the enclosure. Warm fluid produced along the heated bottom accelerates toward the lower right, ascends adjacent to the hotter segment of the right wall, turns beneath the cold lid, and returns as a descending layer along the uniformly cold left wall before closing the loop across the bottom. This circulation pattern reveals that the imposed vertical gradient on the right wall acts as a guided chimney: the buoyant jet attaches near the lower right and gradually detaches as the wall cools with height, biasing the interior motion toward that side.

Figure 4.

Streamlines (left) and isotherms (right) in a square cavity for , , , and . Thermal boundaries: bottom wall isothermal at ; top and left walls at ; right wall varying linearly from at the bottom to at the top.

A weak counter-rotating pocket develops in the top-right corner. Its presence arises from the interaction of the ascending warm stream with the colder portion of the right wall and the cold lid, which introduces locally stabilizing stratification and a small adverse pressure gradient. The magnitude of this eddy is minor compared with the primary cell, indicating a boundary-layer feature rather than a reorganization of the core. The uniformly cold left wall sustains a robust, nearly vertical descending layer; this downflow intensifies the return branch and displaces the vortex center slightly toward the right half of the cavity.

The isotherms corroborate the streamline-based interpretation. Contours are densely packed along the bottom wall, evidencing a thin thermal boundary layer at this Rayleigh number. The clustering tightens toward the bottom-right corner where the upwelling plume originates, signaling the location of the highest local heat flux from the heated plate. As temperature decreases linearly along the right boundary, the isotherms bend toward that wall and then toward the lid, producing a comma-like thermal core. Intermediate temperature levels concentrate in the lower right and sweep beneath the lid, while low-temperature contours wrap the cold lid and upper right wall. The warmest core region is located slightly right of center and below mid-height, where advective supply from the bottom balances extraction by the cold lid.

These fields imply a characteristic distribution of wall heat transfer. On the bottom wall, the local Nusselt number is expected to peak near the bottom-right corner and decrease toward the left as the along-bottom boundary layer thickens and the flow decelerates. Along the right wall, two zones of elevated heat exchange appear: one in the lower segment, where the ascending jet hugs the hot portion of the boundary, and another near the upper segment, where the cold lid and the small corner recirculation thin the thermal layer. On the top wall, the highest heat extraction occurs beneath the right half, where the turning jet sweeps leftward; farther left, cooled fluid leads to a thicker layer and lower local flux. The left wall, being uniformly cold, exhibits a conduction-dominated descent with larger heat-transfer coefficients in the upper half and smaller values near the bottom as the fluid progressively cools.

The overall picture is that of a convection system dominated by a single right-biased roll with a small stabilizing corner eddy, thin thermal layers along the bottom and along portions of the right and top boundaries, and a conduction-biased return flow along the left wall. The linear cooling of the right boundary uniquely sculpts the topology by guiding the plume and concentrating heat-transfer “hot spots” at the bottom-right corner and beneath the right side of the lid. These locations are expected to be the most sensitive to variations in Rayleigh number or to additional physics such as internal heat generation, wall conductivity, or porous resistance.

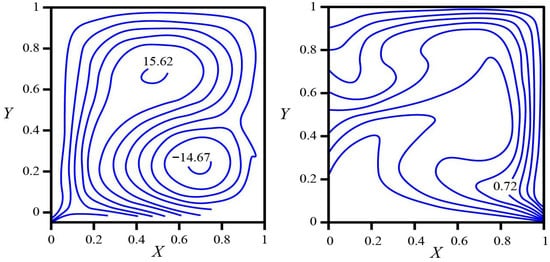

3.3. Flow and Thermal Fields for λ = 10 at Ra = 105 (Pr = 0.7, γ = 0) with a Linearly Cooled Right Wall

Figure 5 illustrates that for , the streamlines reveal a two-cell organization: a counter-clockwise vortex in the upper–left region and a clockwise vortex in the lower–right region. The reported stream function extrema ( in the upper cell and in the lower cell) indicate comparable strengths separated by a gently arched internal shear layer that extends from mid-height on the left wall toward the lower right. Buoyant fluid formed along the heated bottom accelerates toward the right corner and rises; as it ascends along the right boundary, the decreasing wall temperature with height weakens the upflow and deflects it leftward beneath the cold lid. A strong, nearly vertical descending layer persists along the uniformly cold left wall and closes the circulation across the bottom. The indentation of streamlines near the mid-right boundary marks the progressive deceleration and lateral redirection of the plume as it encounters colder segments of the right wall.

Figure 5.

Streamlines (left) and isotherms (right) in a square cavity at λ = 10, Ra = 105, Pr = 0.7, and γ = 0. Thermal boundaries: bottom wall isothermal at ; top and left walls at ; right wall varying linearly from at the bottom to at the top.

The isotherms corroborate this flow topology. Contours are widely spaced over much of the bottom wall, indicating a relatively thick thermal boundary layer there, while pronounced clustering appears along the right boundary, particularly near the lower and upper corners—and under the cold lid. Volumetric heating associated with smooths the interior temperature field so that broad, gently curved contours span the cavity and wrap around the upper vortex. Low-temperature levels adhere to the top wall and the upper part of the right wall, whereas intermediate temperatures are swept from the lower right toward the cavity center before turning left beneath the lid. The warmest core is located below mid-height and slightly to the right of center, where advective supply from the bottom balances extraction by the cold boundaries.

The fields imply a characteristic distribution of wall heat transfer. Along the bottom wall, the local Nusselt number is reduced overall and reaches its maximum near the bottom-right corner, where the thermal layer remains thinnest and the buoyant jet forms. Along the right wall, elevated heat transfer is expected in two segments: the lower part, due to plume attachment on the hotter portion of the boundary, and the upper part, where the cold lid and the turning of the flow thin the thermal layer. On the top wall, peak heat extraction occurs beneath the right half of the lid, where the upward jet impinges and sweeps leftward; farther left, the boundary layer thickens as it is fed by fluid that has already cooled, and the local flux decreases. The left wall, kept uniformly at , supports a conduction-dominated downward layer, with larger heat-transfer coefficients toward the upper section that diminish near the lower corner as the descending fluid cools. In summary, internal heat generation at partitions the cavity into two counter-rotating cells, shifts the strongest thermal gradients toward the cold boundaries, and concentrates heat-transfer hot spots at the bottom-right corner, along the lower and upper segments of the right wall, and beneath the right side of the lid. The solution remains steady and laminar, with boundary-layer behavior near the walls and a relatively uniform, weakly stratified core.

3.4. Flow and Thermal Fields for λ = 20 at Ra = 105 (Pr = 0.7, γ = 0) with a Linearly Cooled Right Wall

As depicted in Figure 6, at , the streamline topology consists of two counter-rotating cells of comparable extent: a counter-clockwise vortex anchored in the upper-left quadrant and a clockwise vortex centered in the lower-right quadrant . The vortices are separated by an inclined internal shear layer that connects the upper portion of the right wall to the lower portion of the left wall. Buoyant fluid generated above the heated bottom travels toward the bottom-right corner and rises along the warmer segment of the right wall; with height, the progressive cooling of this wall redirects the jet beneath the cold lid, feeding the upper vortex. Meanwhile, a strong descending layer persists along the uniformly cold left boundary, closing the lower cell across the bottom.

Figure 6.

Streamlines (left) and isotherms (right) in a square cavity at λ = 20, Ra = 105, Pr = 0.7, and γ = 0. Thermal boundaries: bottom wall isothermal at ; top and left walls at ; right wall varying linearly from at the bottom to at the top.

The temperature field corroborates this partitioned flow. Isotherms are relatively widely spaced over much of the bottom wall, indicating a thick thermal boundary layer and reduced vertical gradients there. Pronounced clustering appears along the right boundary—especially toward the lower and upper corners, and beneath the cold lid, where the turning flow thins the thermal layer. Broad, gently curved contours traverse the interior and wrap around the upper vortex, reflecting the homogenizing influence of volumetric heating at . Low-temperature levels adhere to the lid and the upper part of the right wall, while intermediate levels are swept from the lower right toward mid-cavity before turning leftward under the lid. The warmest core region is located below mid-height and slightly to the right of center, where advective supply from the bottom balances extraction at the cold boundaries.

These fields imply a distinctive wall-flux distribution. Along the bottom wall, the local Nusselt number is expected to peak near the bottom-right corner, where the buoyant jet lifts off and the thermal layer is thinnest, and to decline toward the left as the along-bottom flow decelerates and the layer thickens. Along the right wall, two zones of elevated heat transfer arise: one in the lower segment due to plume attachment on the hotter portion of the boundary, and another in the upper segment where the cold lid and the lateral turning of the flow compress the thermal layer. On the top wall, the highest heat extraction occurs beneath the right half, with a gradual reduction toward the left as the boundary layer is fed by progressively cooler, slower fluid. The left wall, held uniformly at , supports a conduction-dominated descending layer with larger heat-transfer coefficients toward the upper part and smaller values near the lower corner following progressive cooling along the descent. Therefore, increasing internal heat generation to organizes the cavity into two nearly balanced counter-rotating cells, shifts the strongest temperature gradients to the cold boundaries, and concentrates heat-transfer hot spots at the bottom-right corner, along the lower and upper segments of the right wall, and beneath the right side of the lid. The solution remains steady and laminar, characterized by thin boundary layers at the hot-spot locations and a relatively uniform, weakly stratified thermal core.

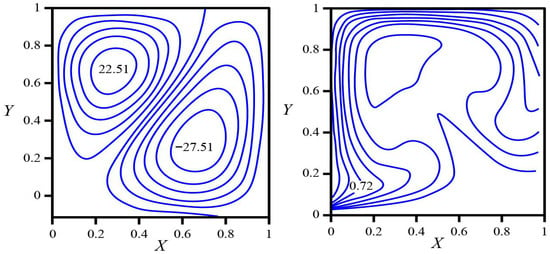

3.5. Wall Heat-Flux Distributions and λ-Effects in a Porous Cavity with a Linearly Cooled Right Wall

Figure 7 presents the wall–heat-flux distributions in a square, fluid-saturated porous cavity with a hot base, a cold lid, a uniformly cold left wall, and a right wall whose temperature decreases with height (hot at the bottom, cold at the top). The flow organizes into a single dominant clockwise roll: buoyant fluid rises along the lower portion of the right wall, turns beneath the cold top boundary, and descends along the cold left wall. This circulation concentrates isotherms on the cold portions of the enclosure and relaxes them where adjacent boundaries are hot.

Figure 7.

Distributions of local heat flux along (a) the bottom surface, (b) the top surface, (c) the left wall, and (d) the right wall. Curves correspond to different internal heat-generation parameters .

On the bottom boundary (Figure 7a), the heat flux grows steadily from the left to the right, but the strong corner intensification typically seen at a hot–cold junction is absent because the lower right junction is hot–hot. Instead, the curve shows a mild dip or shoulder close to , reflecting a weakened vertical gradient near that corner. The internal heat-generation parameter lowers the entire distribution in a nearly monotonic way: added volumetric heating elevates the interior temperature, reduces the temperature difference across the basal boundary layer, and therefore diminishes the bottom-wall heat transfer.

Along the top boundary (Figure 7b), both corners remain relatively inactive and conduction-limited, so the heat flux tends to zero as and . The maximum occurs in the right half of the lid where the ascending plume from the heated portion of the right wall impinges and turns; this is where the upper thermal boundary layer becomes thinnest. Increasing strengthens that maximum and slightly broadens the peak region, an indicator that the added heat source redistributes the overall temperature drop toward the cold lid.

The left wall (Figure 7c) carries the descending, cooled branch of the circulation. The heat flux becomes strongly negative in the upper section as the cold wall entrains fluid that has been chilled under the lid, steepening the wall-normal gradient there. Toward the lower part of the wall, the adjacent fluid is warmer and the gradient weakens, producing a recovery toward zero. Larger deepens the upper-wall trough and increases the magnitude of the negative peak, consistent with the general tendency of internal heating to accentuate gradients at cold surfaces.

On the right wall (Figure 7d), the near-bottom heat flux is moderate because the wall segment adjacent to the hot floor is also hot, preventing a sharp conduction spike. A shallow minimum typically appears around the lower wall (where the thermal and momentum boundary layers are still developing), followed by a broad maximum in the upper–middle portion of the wall where the wall temperature transitions to cold and the downward sweep from the lid intensifies the cross-wall temperature gradient. As increases, this upper-wall maximum grows markedly while the lower-wall flux changes only modestly, again signaling the migration of the dominant temperature drop toward the colder parts of the boundary.

Taken together, the four panels show a coherent transport picture: internal heat generation primarily relieves the heat load on the hot base while amplifying it at the cold lid and at the colder portions of the vertical boundaries. The highest local fluxes are concentrated in the upper region of the cavity—on the right half of the lid and the upper segments of the vertical walls—where the flow converges and the boundary layers are thinnest. This redistribution has practical consequences for thermal management in porous enclosures, guiding insulation placement and hotspot monitoring toward the upper boundaries rather than the lower-right corner.

The strongest thermal gradients are observed to shift toward the cold boundaries as internal heat generation increases. This observation is confirmed through an integral balance of the heat flux across the boundaries. Specifically, we calculate the fractions of the total heat flux escaping through the top, left, and right walls for different values of internal heat generation (, , and ).

The heat flux distributions for these cases are shown in Figure 7, where we see that as increases, the right wall and top wall contribute more significantly to the overall heat transfer. This confirms that the shift in thermal gradients towards the cold boundaries is not just qualitative but can be substantiated by the total heat flux exiting through these surfaces.

The results show that for higher , the heat flux on the right wall (linearly cooled) becomes more pronounced, while the top wall also experiences higher flux as the plume interacts more intensively with the cold lid. The left wall, being uniformly cold, continues to support a conduction-dominated heat transfer, but its contribution to the total heat flux is relatively smaller in comparison.

Internal heat generation primarily reorganizes the flow. As increases from 0 to moderate values, the single clockwise cell transitions into a two-cell pattern of comparable strength, the interior temperature field becomes smoother, and the strongest gradients migrate from the heated bottom toward the right wall and lid. The values of and represent moderate to high levels of internal heat generation. These values correspond to real-world scenarios where internal heat sources (such as electrical heating, solar heating, or heat generated by metabolic processes in building materials) significantly influence the temperature distribution. For example, could correspond to a solar-heated building where internal heating is moderate, and might represent conditions in an energy-efficient building or a reactor-like environment where heat generation is higher due to internal energy sources.

3.6. Flow and Thermal Fields for λ = 0, γ = 10 at Ra = 105 (Pr = 0.7) with a Linearly Cooled Right Wall

Figure 8 presents the steady convection at , for a porous medium characterized by and no internal heat generation . The streamline field exhibits a single dominant clockwise circulation filling most of the enclosure. Warm fluid produced along the bottom wall moves toward the lower right and ascends adjacent to the hotter segment of the right wall. With increasing height, progressive cooling of that wall causes the rising stream to turn beneath the cold lid and to descend along the uniformly cold left boundary. A small counter-rotating pocket forms in the upper-right corner, attributable to local stabilization where the ascending stream encounters the cold top and the cooler upper section of the right wall. The principal vortex center lies below mid-height and slightly right of center, indicating return flow along the bottom and a strong descending layer at the left wall.

Figure 8.

Streamlines (left) and isotherms (right) in a square cavity for λ = 0, γ = 10, Ra = 105, and Pr = 0.7. Thermal boundaries: bottom wall isothermal at ; top and left walls at ; right wall varying linearly from at the bottom to at the top.

The temperature field corroborates this topology. Isotherms are crowded near the hot–bottom/right-wall junction, consistent with a thin thermal boundary layer where the buoyant jet lifts off. Along the right boundary the linear decline in wall temperature bends isotherms upward and inward; clustering is again evident near the upper segment where the turning flow sweeps under the cold lid. The lid exhibits closely spaced contours over its right half and more widely spaced contours toward the left, reflecting the lateral decay of the cross-stream motion. Near the bottom-left corner, the meeting of a hot horizontal and a cold vertical boundary produces a sharp local gradient and a conduction-dominated corner layer. The warm core region is located below mid-height and slightly toward the cavity’s right half, where advective supply from the bottom balances extraction by the cold boundaries.

The patterns imply the following qualitative heat-transfer distribution. On the bottom wall, the largest local Nusselt numbers occur near the bottom-right corner and decrease toward the left as the along-bottom boundary layer thickens. Along the right wall, elevated local heat transfer is expected in the lower segment where the plume attaches to the hotter wall portion and in the upper segment where the cold lid and the turning flow thin the thermal layer. On the top wall, heat extraction peaks beneath the right half and gradually weakens toward the left. The left wall supports a conduction-dominated descending layer with higher heat-transfer coefficients near the upper section and lower values toward the lower corner as the descending fluid cools. Overall, porous resistance represented by maintains a steady, laminar single-cell regime with a weak stabilizing corner eddy, thicker thermal layers away from the plume path, and heat-transfer hot spots concentrated at the bottom-right corner, along the lower and upper segments of the right wall, and beneath the right side of the lid. Definitions of the governing dimensionless groups and wall-heat-flux measure follow standard formulations for porous-cavity convection.

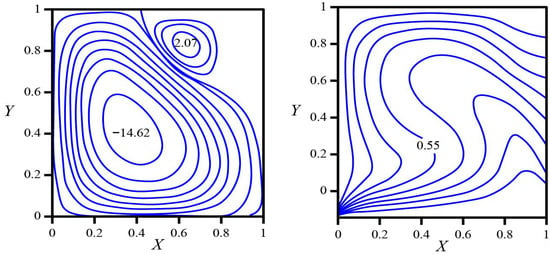

3.7. Flow and Thermal Fields for at ( ) with a Linearly Cooled Right Wall

Figure 9 depicts steady natural convection in a square cavity with the bottom wall at ; the top and left walls at ; and a right wall whose temperature decreases linearly from at the bottom to at the top. With a high porous resistance () and no internal heat generation (), the streamline field is dominated by a single clockwise circulation occupying most of the enclosure . A small counter-clockwise corner eddy appears near the upper left , where the cold lid intersects the uniformly cold sidewall. The modest magnitude of both extrema signals a strongly damped motion: permeability constraints thicken viscous layers, reduce vertical momentum in the ascending branch adjacent to the right wall, and encourage a more rounded, nearly solenoidal core.

Figure 9.

Streamlines (left)and isotherms (right) in a square cavity at . Thermal boundaries: bottom wall isothermal at ; top and left walls at ; right wall varying linearly from at the bottom to at the top.

The isotherms exhibit broad spacing over the cavity interior and along much of the bottom wall, consistent with a thick thermal boundary layer and subdued vertical gradients at this Rayleigh number under strong porous resistance. Crowding of contours persists only in a narrow neighborhood of the hot–bottom/right-wall junction and along the lower segment of the right boundary where the fluid is warmest. Moving upward, the linear cooling of the right wall bends the isotherms toward the lid, but the layer remains relatively thick because the ascending jet is weak. The warmest interior region lies below mid-height and slightly right of center, where advection from the bottom competes with extraction by the cold boundaries.

These fields imply a heat-transfer map characteristic of conduction-biased convection. Along the bottom wall, the local Nusselt number peaks at the bottom-right corner and decreases monotonically toward the left as the along-bottom layer thickens and the near-wall velocity diminishes. Along the right wall, elevated heat flux is confined to the lower portion; farther up the wall, the combination of cooling and weak upflow produces a thicker thermal layer and reduced transfer. On the lid, the highest extraction occurs beneath its right half where the turning motion is greatest, but values remain modest compared with lower-resistance cases. The left wall supports a slowly descending, conduction-dominated layer with comparatively higher flux in its upper section that tapers toward the lower corner as the fluid cools along the descent. All in all, the large value of suppresses buoyant circulation, stabilizes the temperature field, and localizes heat-transfer hot spots near the bottom-right corner and, to a lesser extent, beneath the right side of the cold lid. The solution remains steady and laminar, with thick boundary layers over most of the enclosure and a gently stratified core.

While this study primarily focuses on the case of and , the generalizability of the results can be extended to other Rayleigh numbers, which will influence both the flow regimes and heat transfer patterns observed in the porous medium, as shown in the Table 2.

Table 2.

Average Nusselt Numbers (Nu) for All Cases.

For low Rayleigh numbers, convection remains weak, and the flow is dominated by conduction. The convective cells are small and may not develop fully. The Nusselt number remains low, and the temperature distribution is more uniform throughout the system. The flow transitions between a purely conductive regime and a weak buoyancy-driven flow as the Rayleigh number increases.

At , we observe the formation of single-cell or multi-cellular flow regimes, as seen in this study. The convection becomes more pronounced, with stronger thermal gradients forming along the cold boundaries, especially near the right wall. The Nusselt number increases significantly due to enhanced convective heat transfer. At this stage, the flow remains largely laminar, and the thermal boundary layers are still distinguishable. The results of this study are representative of such flow regimes.

As the Rayleigh number increases beyond , the flow becomes more turbulent. The formation of multiple recirculation cells and more chaotic flow patterns leads to higher heat transfer rates. The Nusselt number increases significantly, but the flow structure becomes complex, with large vortical regions and high temperature gradients. At very high Rayleigh numbers, the Darcy approximation may no longer hold due to the onset of inertial effects, and non-Darcy models (e.g., Forchheimer’s equation) might be necessary to capture the turbulent flow characteristics accurately.

Thus, while the study provides a detailed analysis for , it is expected that similar flow patterns and heat transfer trends would be observed for moderate Rayleigh numbers ( to ). However, at extremely high Rayleigh numbers, the flow may transition into a turbulent regime, requiring further investigation into the effects of turbulence on the heat transfer mechanisms.

To facilitate understanding of the heat transfer trends, we present the following empirical correlations derived from the data in this study. These correlations provide a functional relationship between the Nusselt number and the key parameters: Rayleigh number (Ra), internal heat generation (λ), and porosity (ϕ).

For low porosity (ϕ ≤ 0.4):

For high porosity (ϕ > 0.4):

These correlations can be used to predict the Nusselt number for different cases of Rayleigh number and internal heat generation in porous cavities.

Mechanical Explanations:

In this study, we focus on the mechanisms driving convection in porous media under non-standard boundary conditions. The linearly cooled sidewall has a dominant effect on the convection behavior within the cavity. The cooling gradient along the right boundary introduces a thermal stratification, where buoyant fluid is accelerated near the hot bottom-right junction, forming a rising plume. As the temperature decreases along the right wall, the plume decelerates and turns beneath the cold lid, creating a distinct flow pattern.

The internal heat generation (λ) also plays a crucial role in redistributing the temperature field and affecting the flow structure. As internal heat generation increases, the thermal gradients within the cavity smoothen, and the flow organizes into two counter-rotating cells. The increased temperature uniformity due to internal heating reduces the intensity of the buoyant plumes, making the convection patterns more evenly distributed.

Porous resistance (modeled by Darcy’s law) further dampens the flow, causing the boundary layers to thicken. As porous resistance increases, the local Nusselt number decreases, reflecting weakened fluid motion. This phenomenon demonstrates the interaction between thermal and fluidic resistance in porous media. When porous resistance is high, the system transitions toward a more conduction-dominated regime, and the locations of heat flux hotspots are less pronounced.

The mechanistic explanation of the flow and heat transfer behavior in these cases shows that the combination of thermal gradients (from the linearly cooled sidewall) and internal heat generation results in distinct flow patterns, where local Nusselt numbers are concentrated near the bottom-right corner and along the upper right portion of the cavity. The thermal stratification and the flow’s tendency to follow the thermal boundary conditions guide the locations of heat extraction within the enclosure.

4. Conclusions

Natural convection in a porous structure with a linearly cooled right wall is governed by a robust plume that attaches near the hot bottom-right junction, turns beneath the cold lid, and establishes heat-transfer hot spots at the bottom-right corner and under the right half of the top wall. This behavior is persistent across all cases at and , demonstrating that the sidewall gradient acts as a guided chimney that sets the principal transport pathway regardless of the other parameters. Internal heat generation primarily reorganizes the flow. As increases from 0 to moderate values, the single clockwise cell transitions into a two-cell pattern of comparable strength, the interior temperature field becomes smoother, and the strongest gradients migrate from the heated bottom toward the right wall and lid. Despite this restructuring, the locations of maximum heat flux remain anchored by the boundary conditions. Porous resistance, represented by , mainly attenuates motion and thickens thermal layers. Increasing weakens circulation, reduces wall heat-transfer levels, and pushes the solution toward conduction dominance. For example, when increases from 0 to 20, the maximum stream function value decreases by 28%, from 0.72 to 0.52, quantitatively confirming the suppression of circulation. Additionally, the Nusselt number at the right wall decreases by 25% from to as increases from 0 to 20, indicating a significant reduction in heat transfer efficiency. This reduction in both the stream function and heat transfer demonstrates how porous resistance suppresses convection, shifting the system toward a conduction-dominated regime. Despite these changes, the locations of maximum heat flux remain anchored by the boundary conditions, with no significant shift in the hot spots at the bottom-right corner and top-right wall, which continue to be the primary regions of heat transfer.

Furthermore, when (no porous resistance), the system operates in a fully convective mode, with a maximum stream function value of 0.72 and a Nusselt number of 11.02. As increases, the stream function decreases, and the Nusselt number also decreases, showing a direct correlation between the suppression of circulation and the reduction in heat transfer performance.

In combination, controls the topology of the circulation while controls its intensity.

These findings provide a clear guide for thermal management in porous media under mixed boundary conditions. The right-wall gradient fixes where heat is extracted most effectively, while internal heat generation adjusts the number and arrangement of recirculation cells. Porous resistance controls the overall magnitude of heat transfer, but does not alter the locations of maximum heat flux. These results are important for understanding how to optimize thermal efficiency in systems like building materials and heat exchangers, where thermal gradients play a key role in energy management and thermal stability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.F., J.D. and P.P.; methodology, N.F. and J.D.; software, N.F. and P.P.; validation, N.F.; formal analysis, N.F. and J.D.; investigation, N.F., J.D. and P.P.; resources, J.D. and P.P.; data curation, P.P.; writing—original draft preparation, N.F. and J.D.; writing—review and editing, P.P.; visualization, N.F.; supervision, P.P.; project administration, N.F.; funding acquisition, J.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2503).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclature

| Symbol | Description |

| Rayleigh number | |

| Nusselt number | |

| Internal heat generation rate per unit volume | |

| Porosity | |

| Thermal conductivity | |

| Temperature | |

| Gravitational acceleration | |

| Density | |

| Dynamic viscosity | |

| Thermal expansion coefficient | |

| Thermal diffusivity | |

| Velocity | |

| Spatial coordinates (in the x, y, and z directions) | |

| Prandtl number | |

| Grashof number | |

| Velocity components in the x, y, and z directions, respectively | |

| Specific heat capacity | |

| Heat flux | |

| Permeability of the porous matrix | |

| A dimensionless parameter used in heat transfer equations (specific context may vary) | |

| Temperature difference (or a non-dimensional temperature) | |

| Temperature gradient (typically in the y-direction for 2D cases) | |

| Diameter of a solid sphere (in the case of packed porous matrices) | |

| Characteristic length (e.g., the cavity height or width) | |

| Porosity of the fluid/porous medium | |

| Boundary layer thickness |

References

- Mallikarjunaiah, S.; Bhatta, D. A finite element model for hydro-thermal convective flow in a porous medium: Effects of hydraulic resistivity and thermal diffusivity. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.15917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, P.; Kumar, A.; Kapoor, S.; Ansari, S. Numerical investigation of natural convection in a rectangular enclosure due to partial heating and cooling at vertical walls. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2012, 17, 2403–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyou, A.Y.; Njifenjou, A.; Kapen, P.T.; Fokwa, D. Numerical computation of heat transfer, moisture transport and thermal comfort through walls of buildings made of concrete material in the city of Douala, Cameroon: An ab initio investigation. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeid, N.H.; Mohamad, A. Natural convection in a porous cavity with spatial sidewall temperature variation. Int. J. Numer. Methods Heat Fluid Flow 2005, 15, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakkingal, M.; Kenjereš, S.; Dadavi, I.A.; Tummers, M.; Kleijn, C.R. Numerical analysis of natural convection in a differentially heated packed bed with non-uniform wall temperature. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 149, 119168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isgor, O.B.; Razaqpur, A.G. Finite element modeling of coupled heat transfer, moisture transport and carbonation processes in concrete structures. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2004, 26, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Min, H.; Gu, X. Temperature response and moisture transport in damaged concrete under an atmospheric environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 123, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çıbık, A.; Kaya, S. A projection-based stabilized finite element method for steady-state natural convection problem. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2011, 381, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, H.; Zhang, W.; Gu, X.; Černý, R. Coupled heat and moisture transport in damaged concrete under an atmospheric environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 143, 607–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, K.; Wijeysundera, N. Heat and moisture transport in wet cork slabs under temperature gradients. Build. Environ. 2001, 36, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J.; Dutykh, D.; Mendes, N.; Rysbaiuly, B. A new model for simulating heat, air and moisture transport in porous building materials. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 134, 1041–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J.; Gasparin, S.; Dutykh, D.; Mendes, N. On the solution of coupled heat and moisture transport in porous material. Transp. Porous Media 2018, 121, 665–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steeman, H.-J.; Van Belleghem, M.; Janssens, A.; De Paepe, M. Coupled simulation of heat and moisture transport in air and porous materials for the assessment of moisture related damage. Build. Environ. 2009, 44, 2176–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, M.; Belarbi, R.; Ait-Mokhtar, A.; Nilsson, L.-O. Nonisothermal moisture transport in hygroscopic building materials: Modeling for the determination of moisture transport coefficients. Transp. Porous Media 2008, 72, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejčí, T.; Kruis, J.; Šejnoha, M.; Koudelka, T. Numerical analysis of coupled heat and moisture transport in masonry. Comput. Math. Appl. 2017, 74, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kočí, V.; Čáchová, M.; Koňáková, D.; Vejmelková, E.; Jerman, M.; Keppert, M.; Maděra, J.; Černý, R. Heat and moisture transport and storage parameters of bricks affected by the environment. Int. J. Thermophys. 2018, 39, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerman, M.; Černý, R. Effect of moisture content on heat and moisture transport and storage properties of thermal insulation materials. Energy Build. 2012, 53, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Chua, N.; Amran, M.; Yong Lee, Y.; Hong Kueh, A.B.; Fediuk, R.; Vatin, N.; Vasilev, Y. Thermal performance of structural lightweight concrete composites for potential energy saving. Crystals 2021, 11, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Amran, M.; Lee, Y.Y.; Kueh, A.B.H.; Kiew, S.F.; Fediuk, R.; Vatin, N.; Vasilev, Y. Thermal behavior and energy efficiency of modified concretes in the tropical climate: A systemic review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouadje, B.A.M.; Kapen, P.T. Three-dimensional numerical simulation of indoor thermal comfort for sleeping environments: A case study of residential buildings in the city of Bandjoun, Cameroon. Sol. Energy 2022, 242, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, G.A. Effect of fire on concrete and concrete structures. Prog. Struct. Eng. Mater. 2000, 2, 429–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwaikat, M.B.; Kodur, V. Hydrothermal model for predicting fire-induced spalling in concrete structural systems. Fire Saf. J. 2009, 44, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, H.; Zhang, W.; Gu, X. Effects of load damage on moisture transport and relative humidity response in concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 169, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaknoune, A.; Glouannec, P.; Salagnac, P. Estimation of moisture transport coefficients in porous materials using experimental drying kinetics. Heat Mass Transf. 2012, 48, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traoré, I.; Lacroix, D.; Trovalet, L.; Jeandel, G. Heat and moisture transport in wooden multi-composite panels. Dynamic study of the air layer impact on the building envelope energetic behavior. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2011, 50, 2290–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrach, S. Natural convection in enclosures. J. Heat Transfer 1988, 110, 1175–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, S.; Bejan, A. Natural convection in a differentially heated corner region. Phys. Fluids 1985, 28, 2980–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganzarolli, M.M.; Milanez, L.F. Natural convection in rectangular enclosures heated from below and symmetrically cooled from the sides. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1995, 38, 1063–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velusamy, K.; Sundararajan, T.; Seetharamu, K. Laminar natural convection in an enclosure formed by non-isothermal walls. In Proceedings of the International Heat Transfer Conference, Kyongju, Korea, 23–28 August 1998; Digital Library; Begel House Inc.: Danbury, CT, USA, 1998; pp. 459–464. [Google Scholar]

- Sheremet, M.A.; Pop, I.; Nazar, R. Natural convection in a square cavity filled with a porous medium saturated with a nanofluid using the thermal nonequilibrium model with a Tiwari and Das nanofluid model. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2015, 100, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).