1. Introduction

The dense road network has played a crucial role in enhancing transportation service levels, improving economic efficiency, and elevating residents’ travel quality. However, the motor vehicle exhaust and traffic noise generated during operation have caused irreversible damage to the ecological environment of road areas. Motor vehicle exhaust emissions represent a major source of pollution with significant impact on road operations, primarily consisting of harmful gases such as hydrocarbons (HCs), carbon monoxide (CO), and nitrogen oxides (NOx). These gases pose a substantial threat to human respiratory and immune systems and contribute to ecological imbalances in the surrounding atmospheric and soil environments. Motor vehicle exhaust contains more than 200 chemical compounds. Among them, NOx can impair respiratory function and contribute to bronchitis, emphysema, and other pulmonary diseases, while also exacerbating cardiovascular conditions. CO readily induces hypoxia, dizziness, and fatigue in humans. Hydrocarbons, classified as carcinogens by most health agencies, can trigger declines in lung function, asthma, and other related ailments.

The emphasis on road area atmospheric pollution originated from environmental assessment systems, and conducting environmental evaluations for engineering projects has become a legal requirement in most countries [

1,

2]. The United States enacted the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) in 1969 [

3], which introduced the mandatory requirement for environmental assessments: “All federal agencies must provide a detailed description of the environmental impact of any proposed federal action that significantly affects the quality of the human environment”. This legislation sparked a surge of attention toward environmental issues.

“Environmental protection” is one of China’s fundamental national policies, and the principle of “prevention first, combined prevention and control” is enshrined in the country’s basic environmental and resource protection laws. To implement this principle, Article 6 of the Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China (Trial Implementation) [

4], promulgated in 1979, stipulates: “All units should pay attention to preventing pollution and destruction of the environment during site selection, design, construction, and production”. However, for a long period, environmental assessments for newly constructed and expanded road projects were largely overlooked. It was not until 1990 and 1996, when the transportation sector introduced the Environmental Protection Management Measures for Transportation Construction Projects [

5] and the Technical Specifications for Environmental Impact Assessment of Highway Construction Projects [

6], that legal and technical foundations for environmental evaluations in road construction projects were established. With the ongoing advancement of the “dual carbon” system, road industry researchers and relevant authorities are increasingly focusing on the environmental issues arising from road construction.

Regarding the atmospheric environment evaluation in road areas, the Environmental Impact Assessment Specification for Highway Construction Projects (JTG B03-2006) [

6] requires the assessment of the current atmospheric conditions along the road, including baseline monitoring, evaluation, and environmental air quality forecasting prior to construction. For the environmental impacts caused by motor vehicle exhaust emissions during the operational phase of highways, it mandates the use of model prediction methods or analogy analysis to estimate the diffusion concentrations. It also provides analogy prediction Formulas (1) and (2), emission source strength calculation methods (3), and model prediction methods.

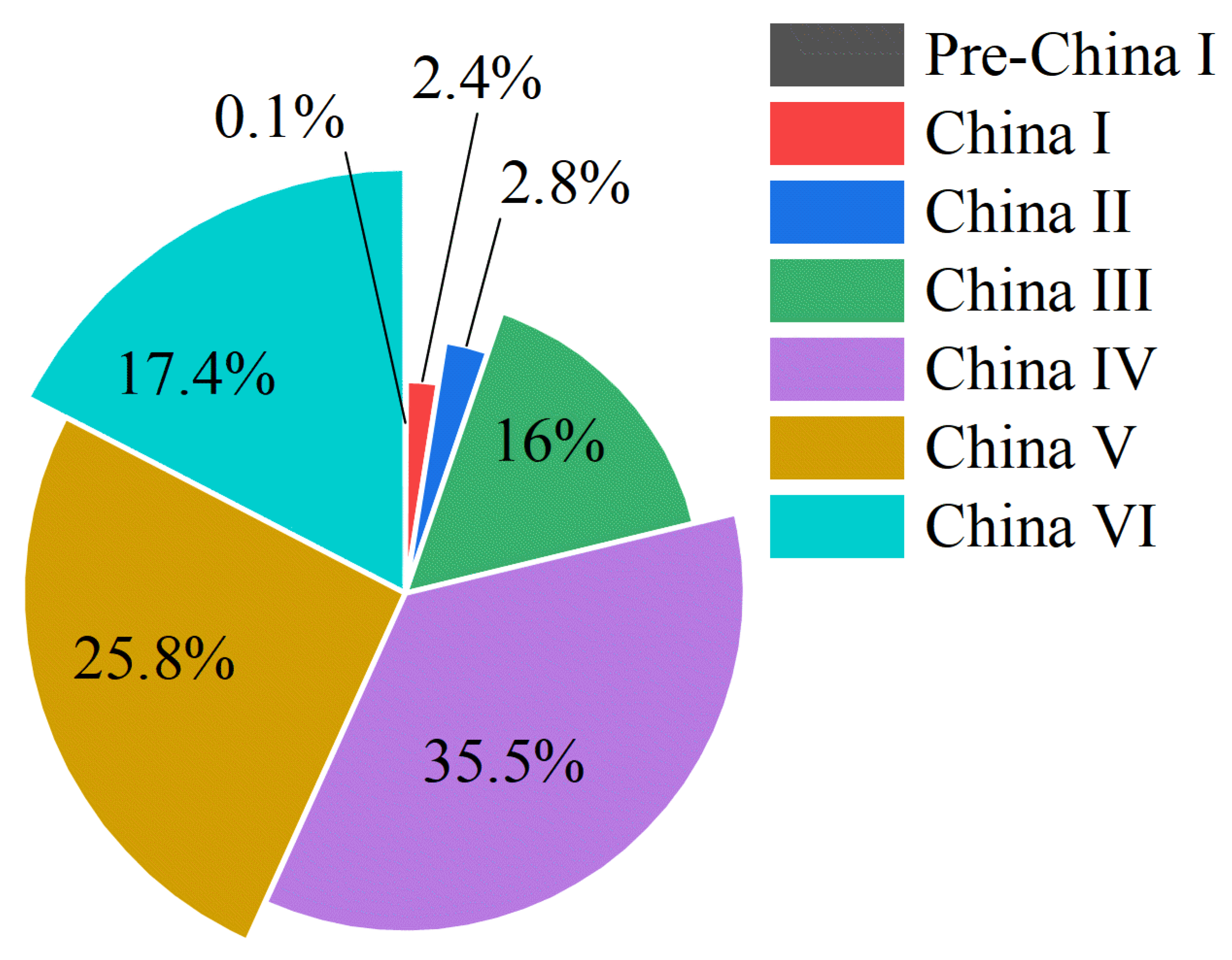

Estimating the motor vehicle exhaust emissions under various types and operating conditions is a crucial component in evaluating the atmospheric environmental impact along roadways. Numerous factors influence motor vehicle exhaust emissions, including traffic volume, vehicle type distribution, operational conditions, and the energy forms used by vehicles. In road atmospheric environmental impact assessment models, motor vehicle emissions are typically represented by emission factors [

7]. Emission factors for most vehicle types are derived from laboratory vehicle emission tests [

8], while traffic emissions are statistically calculated based on the mileage and operating conditions of different vehicle categories.

In addition, numerous studies have been conducted by scholars and institutions worldwide on the evaluation of atmospheric environmental impacts along roadways. In particular, significant progress has been made in the development of dispersion models, which have become increasingly refined and better aligned with real-world conditions. Factors such as vehicle type, fuel type, pollutant species, and emission patterns have been progressively incorporated into these models [

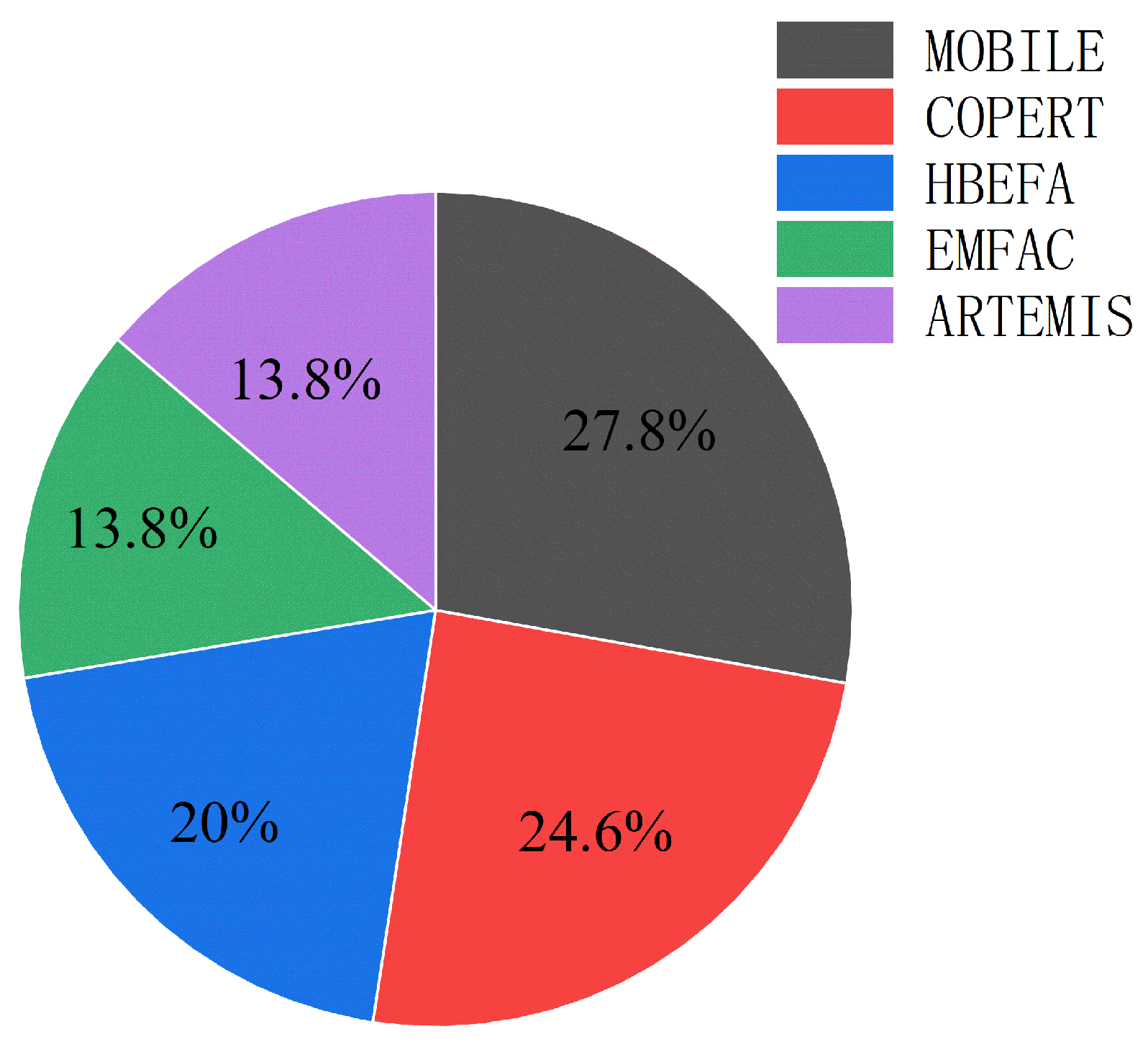

9]. According to literature statistics, five models—MOBILE, COPERT, HBEFA, EMFAC, and ARTEMIS—are most frequently applied in current research, as illustrated in

Figure 1 [

8].

During the 1970s, researchers developed a variety of road exhaust dispersion models based on Gaussian theory [

10], capable of predicting exhaust diffusion patterns using meteorological parameters, road geometry, and fluid diffusion principles. However, these models exhibited significant discrepancies between simulated and observed field data due to the simplification of vehicle-induced wake turbulence [

11,

12]. Subsequently, research institutions conducted controlled field experiments and tracer gas diffusion studies to analyze the influence of vehicle wake turbulence on exhaust dispersion, leading to the refinement and development of more advanced models such as HIWAY 2, CALINE 3 and 4, and GM. These updated models improved prediction accuracy under varying traffic, meteorological, and atmospheric conditions. Moreover, to address the limitations of earlier models—such as the inability to account for wind inclination and infinite roadway lengths—further iterations were introduced in models like GFLSM and CALINE 4.

The analysis methods for studying the diffusion patterns of vehicle pollutants primarily include field measurements, wind tunnel experiments, and numerical simulations [

13]. To date, in China, the calculation of motor vehicle exhaust diffusion in highway environmental impact assessments is typically based on the provisions outlined in the appendix of the Environmental Impact Assessment Specification for Highway Construction Projects [

6].

Among these, studies using fluid dynamics to analyze motor vehicle exhaust pollutant diffusion often focus on relatively enclosed spaces such as shafts and tunnels, or on the influence of specific facilities and their parameters on pollutant diffusion. In underground tunnels and shafts, where ventilation conditions are poor, the diffusion of motor vehicle exhaust pollutants typically requires focused attention. Wang et al. [

14] and Nie et al. [

15], respectively, conducted fluid dynamics modeling and calculations on pollutant diffusion patterns for special vehicle types operating in confined spaces. Researchers in related fields have used fluid dynamics simulation techniques to examine the effects of factors such as rooftop greening systems [

16], building height, facade details [

17], lateral entrainment settings [

18], barrier height [

19], and road landscaping parameters [

20,

21] on motor vehicle exhaust diffusion patterns. At urban road intersections, where vehicle speeds are low and frequent starts and stops occur, pollutant concentrations are generally higher. Hassan et al. [

22] and Sun et al. [

23] also explored these conditions using various models and found that ANSYS Fluent 2023R1 simulation results closely matched field measurements.

In summary, current research on motor vehicle exhaust diffusion patterns and atmospheric environment prediction along roadways primarily focuses on three areas: (1) conducting environmental impact assessments (EIA) for road construction projects in accordance with relevant laws and regulations; (2) improving and refining Gaussian-based exhaust pollutant diffusion calculation models by government departments and researchers; and (3) using fluid dynamics simulations for modeling and analyzing the diffusion patterns of exhaust pollutants in road area environments. However, the improvement of EIA reports and calculation models is largely policy-driven, with exhaust pollutant diffusion predictions being operational but lacking precision. Studies based on fluid dynamics simulations tend to focus on individual vehicles or street-scale models, often failing to integrate the interactive effects between these two dimensions.

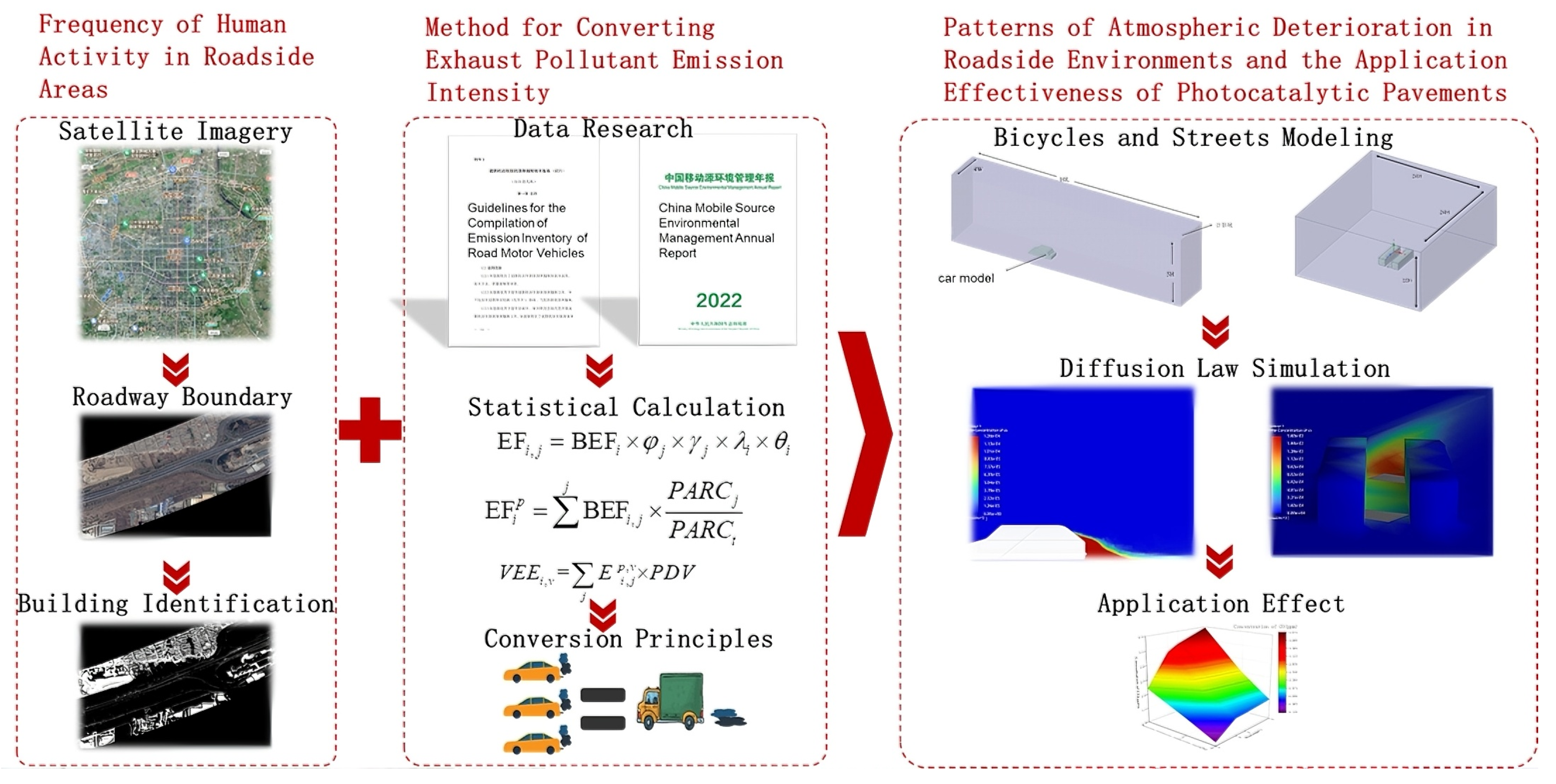

Therefore, this study explores three aspects: the frequency of human activities within road areas, motor vehicle emission intensity, and fluid dynamics simulations of motor vehicle exhaust diffusion in road areas. The study analyzes the impact of motor vehicle exhaust emissions on human activity areas, establishes an equal-pollution motor vehicle exhaust emission intensity model, and develops a fluid dynamics model for atmospheric environment deterioration in road areas. The diffusion patterns of motor vehicle exhaust are analyzed from both the vehicle and street dimensions. The technical approach is illustrated in

Figure 2.

This study seeks to address this gap by examining atmospheric deterioration in road environments through an integrated framework that accounts for the adverse health implications of exhaust constituents, the multiscale dynamics of pollutant dispersion, and the functional efficacy of photocatalytic pavement materials. The primary contributions are threefold: (1) proposing an equivalent-pollution vehicle conversion method based on human toxicity potential; (2) analyzing exhaust diffusion patterns from both individual vehicles and street canyons using CFD; and (3) evaluating the effectiveness of photocatalytic pavement for exhaust mitigation”.

4. Conclusions

This chapter investigates the development of buildings along urban expressways and the current state of motor vehicle exhaust emissions, based on surveys of the building coverage rate and vehicle emission data. An “equivalent pollution vehicle conversion method” is proposed, and fluid mechanics simulations are employed to study the exhaust diffusion patterns of individual vehicles and the atmospheric degradation along roadways. The application effect of photocatalytic pavement for exhaust mitigation is also analyzed. The findings underscore the significance of developing photocatalytic pavement for exhaust mitigation and provide data support for subsequent chapters on the evaluation of exhaust degradation performance. The main conclusions are as follows.

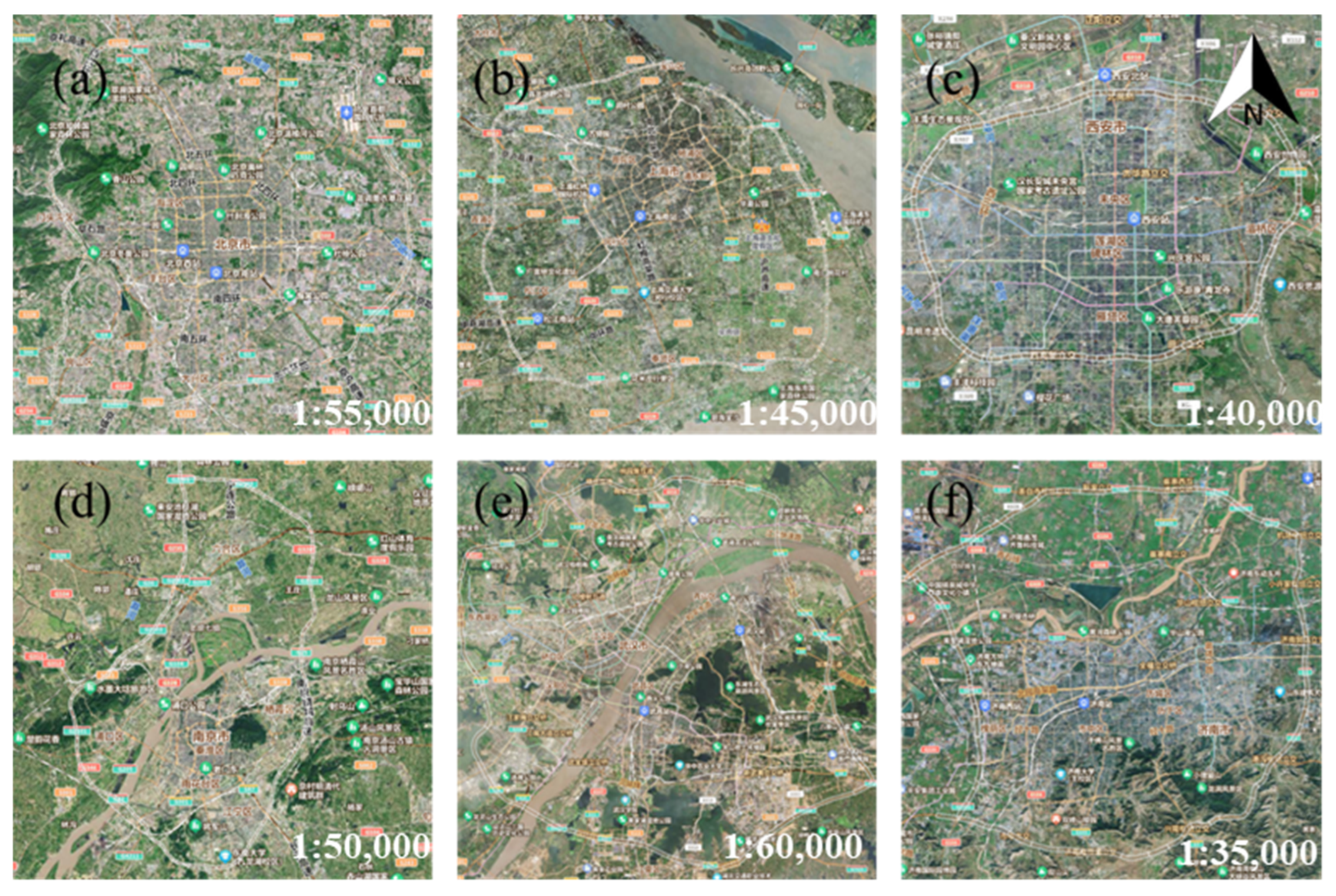

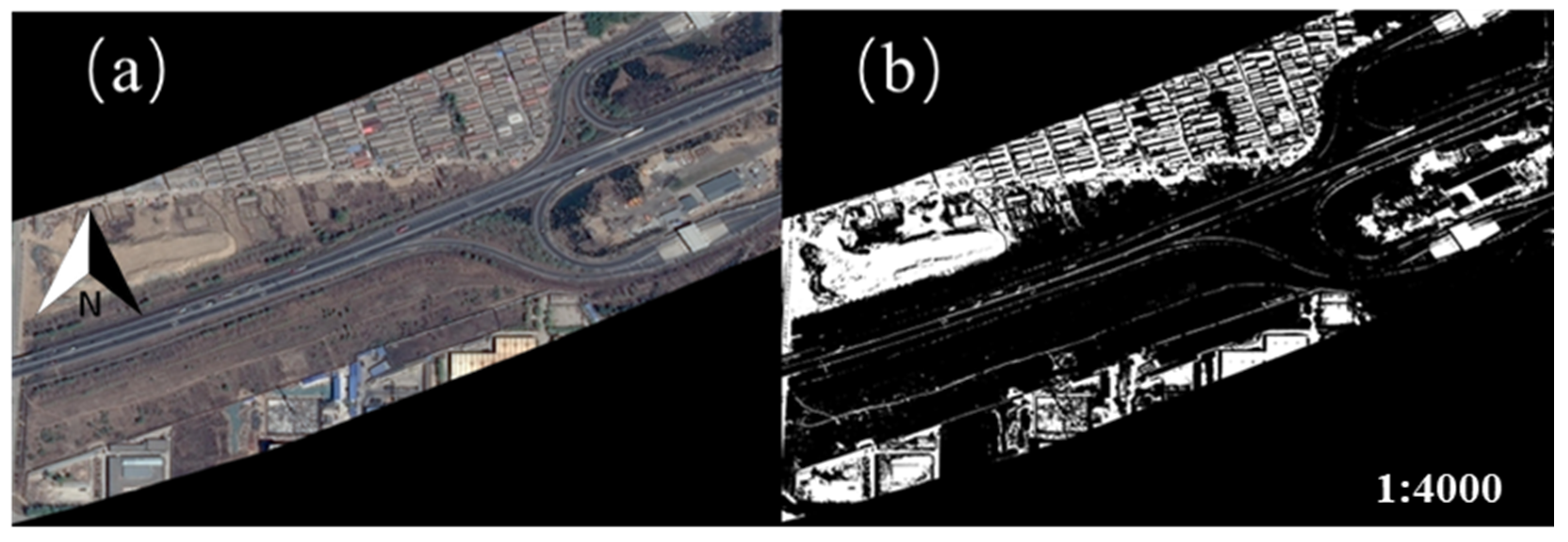

Building Coverage Rate: By utilizing geographic information and image recognition technology, satellite maps of six cities (Beijing, Shanghai, Xi’an, Nanjing, Wuhan, Jinan) over the past decade were analyzed for building coverage along their urban expressways. It was found that, during the early stages of construction, building coverage around the expressways was approximately 1%. As urban development progressed, human activity within the roadway areas increased, resulting in a rise in building coverage, reaching as high as 5.7% depending on the city’s development characteristics and speed.

Vehicle Emission Factors: Statistical analysis of relevant data provided representative composite baseline emission factors for different vehicle types, which were then corrected for speed. By applying human toxic potential factors for pollutants, the equivalent emission values for small passenger vehicles were established for different vehicle types and speeds, resulting in the creation of an equivalent pollution vehicle conversion method.

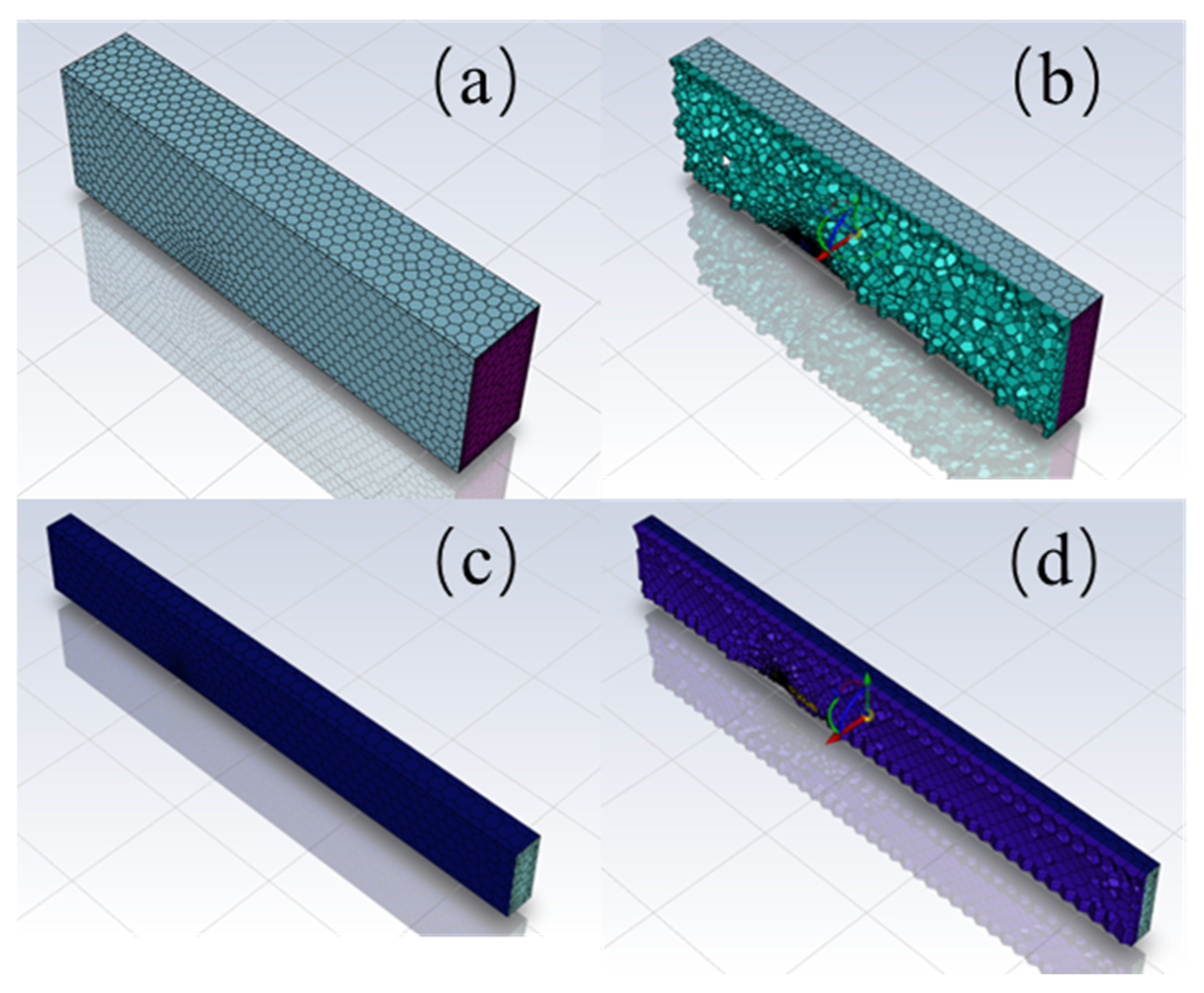

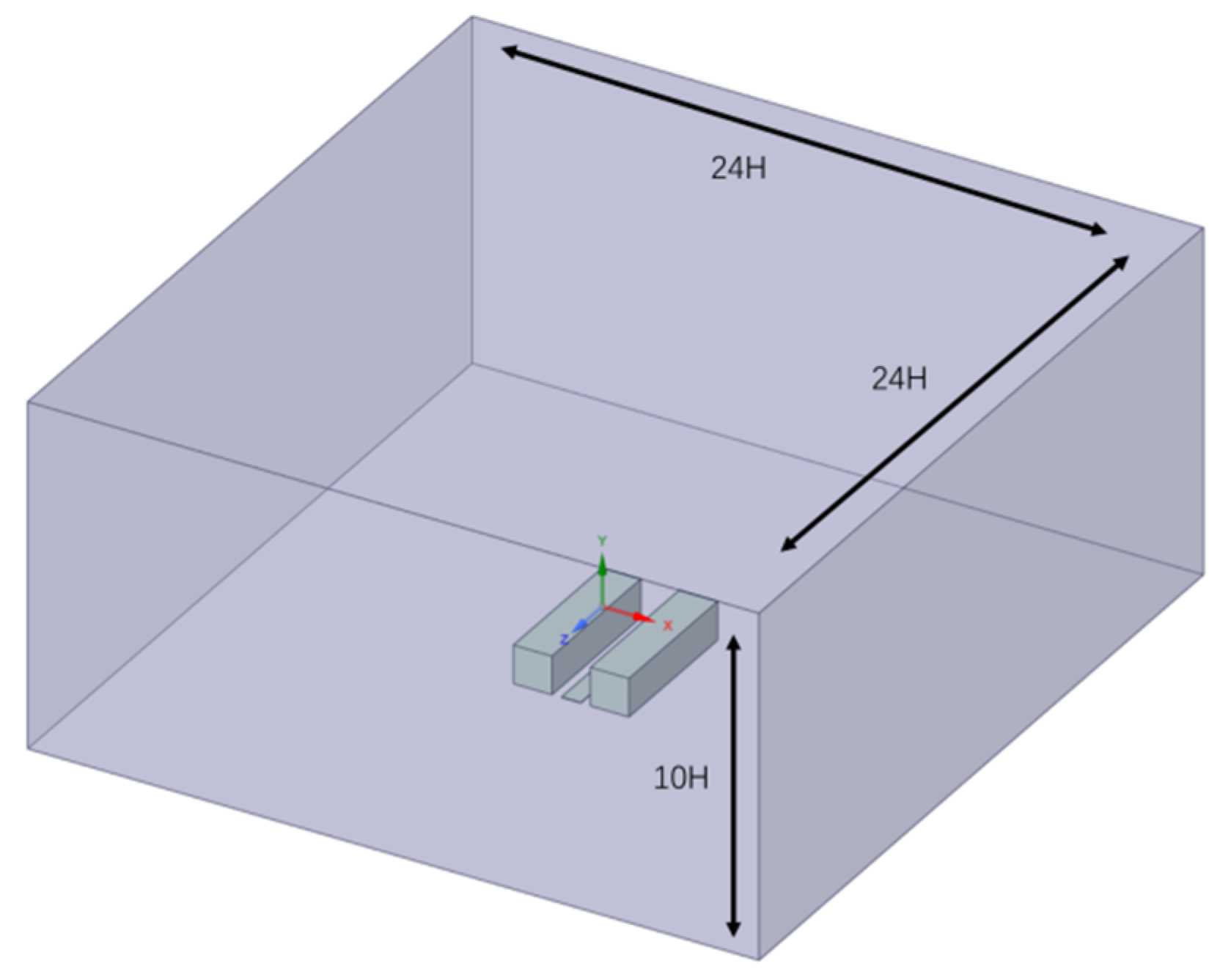

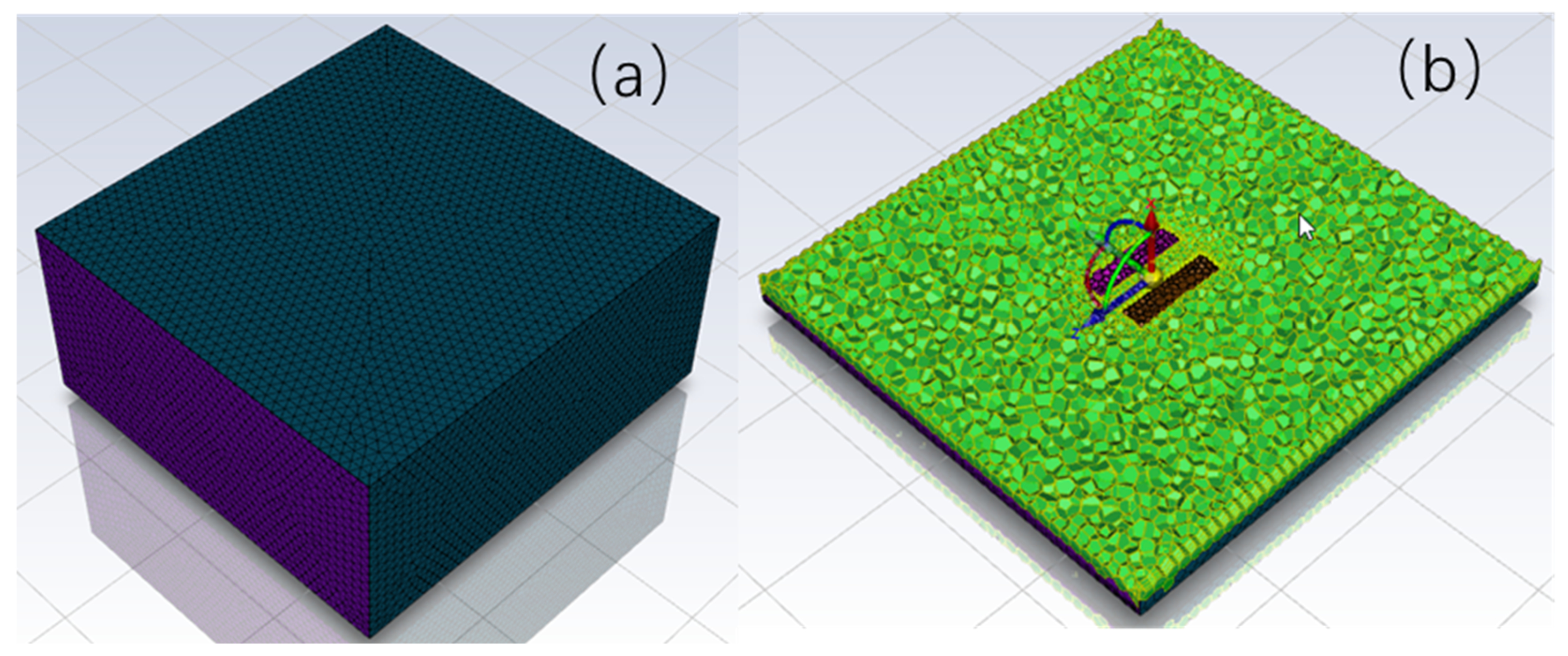

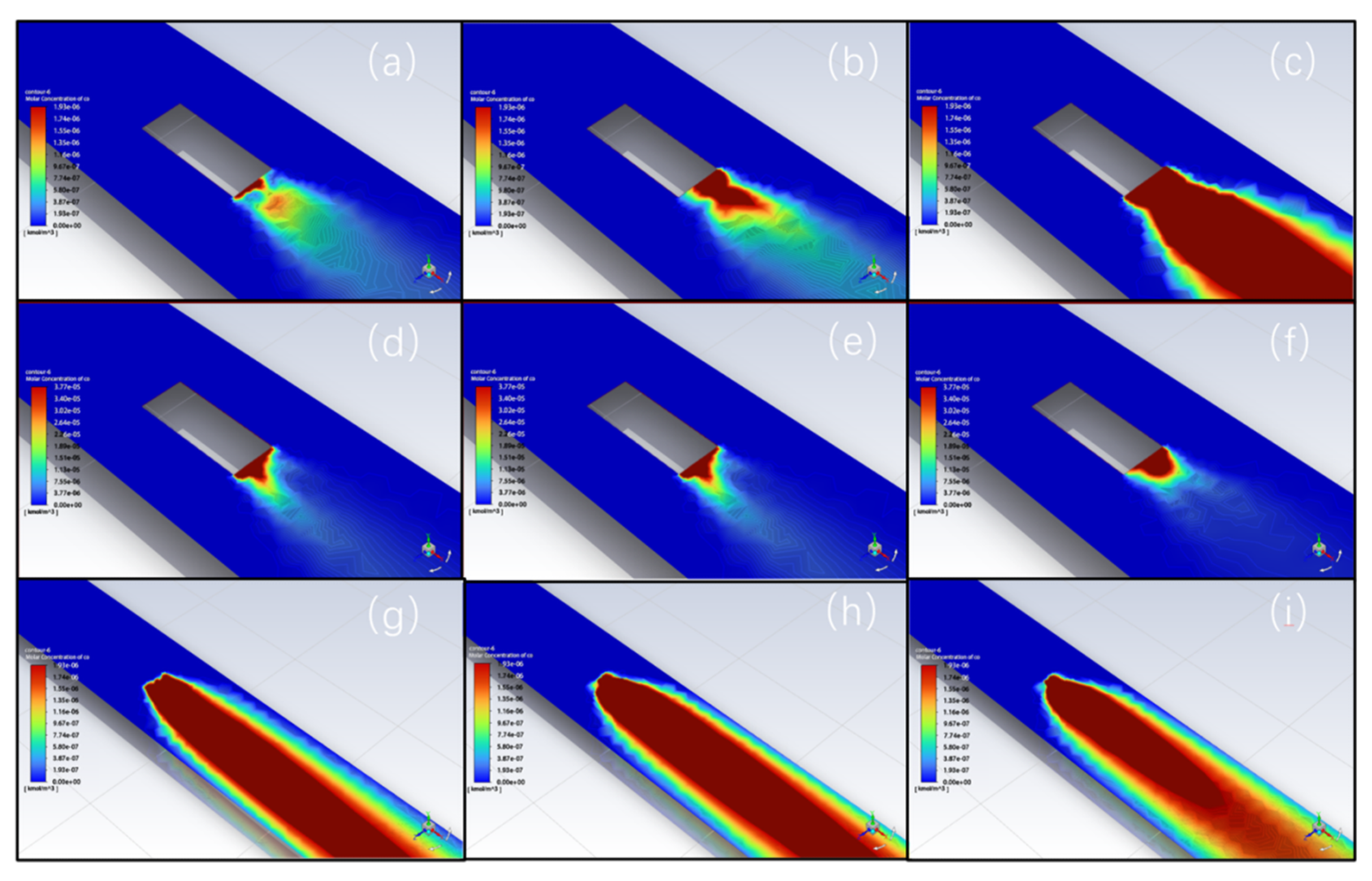

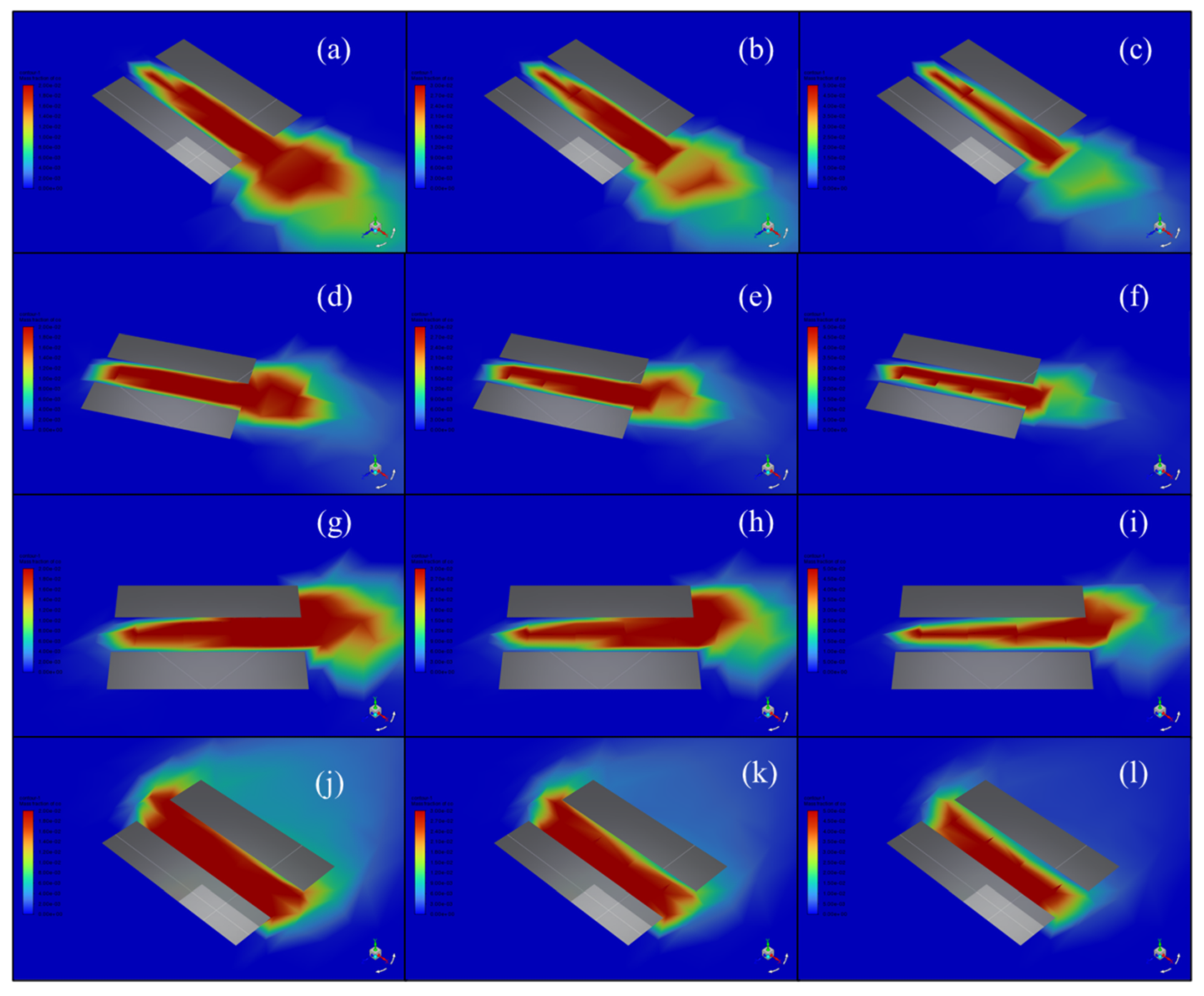

Fluid Mechanics Simulation: Based on statistical data of vehicle dimensions, fluid mechanics simulations were conducted using Fluent software to model small passenger cars and heavy-duty trucks. Relevant boundary conditions and emission parameters were determined. The results showed that under the influence of both driving speed and vehicle type, the distribution range of exhaust pollutants at lower levels was broader, with high-concentration areas concentrated below the vehicle’s height.

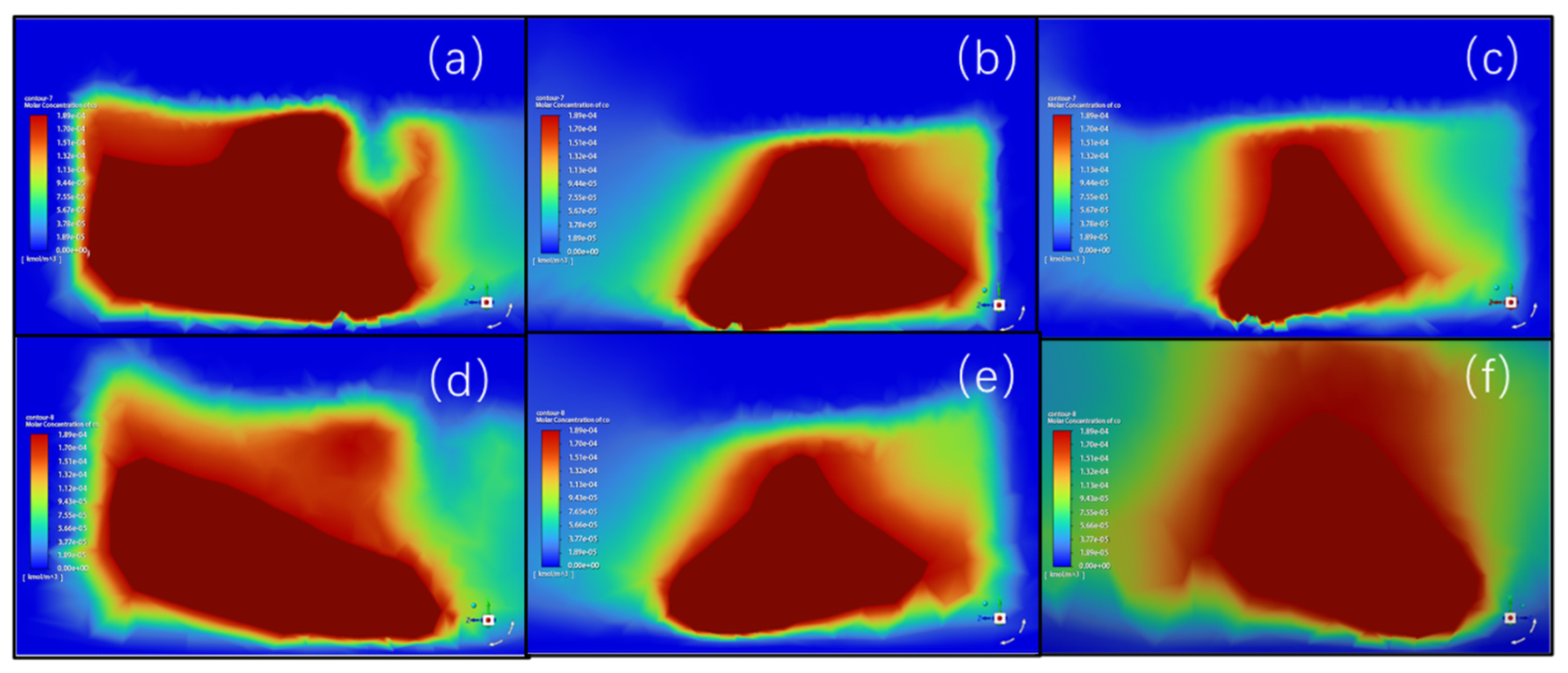

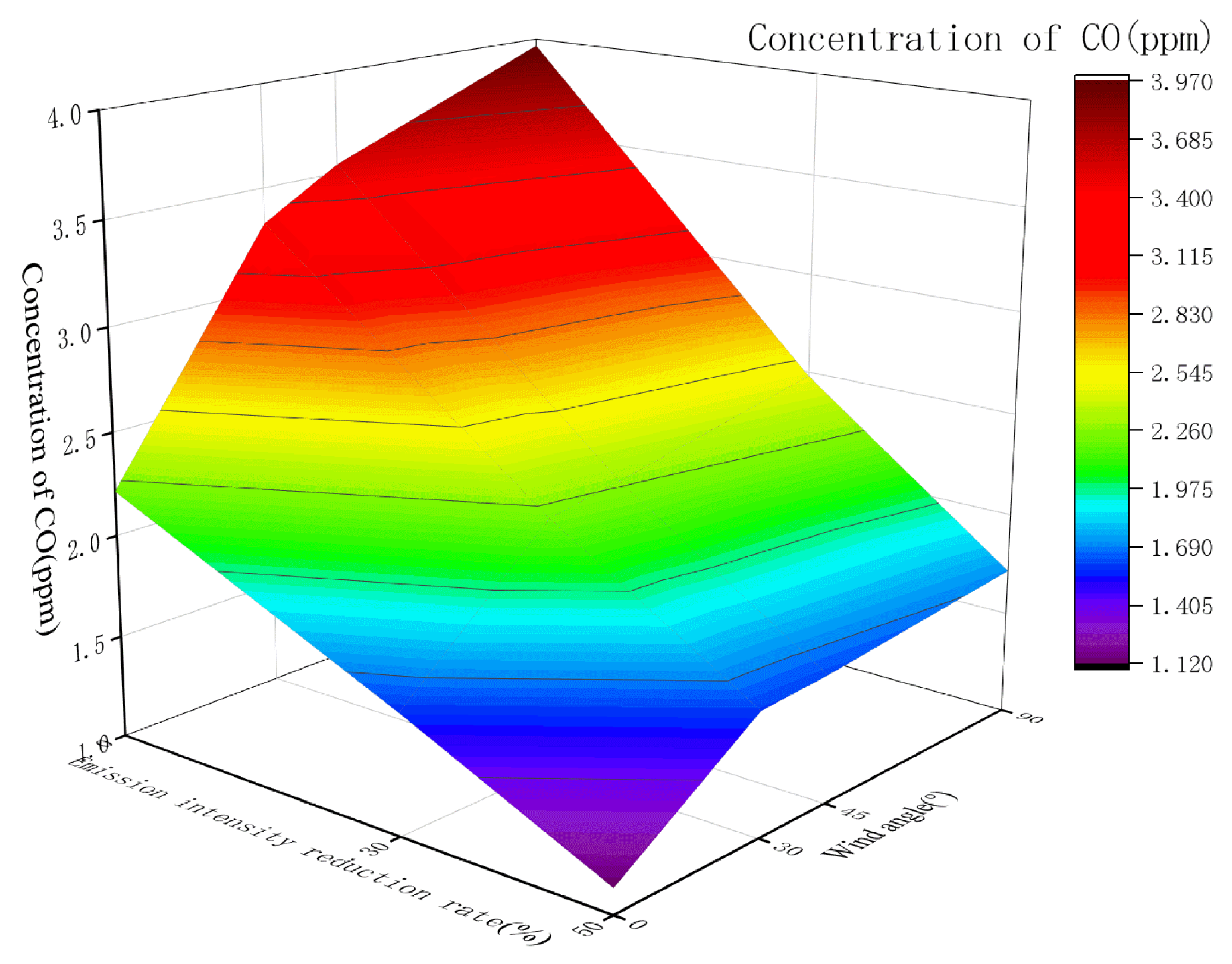

Exhaust Emission Intensity in Different Traffic Conditions: Using the equivalent pollution conversion model and current exhaust emission data, the line-source exhaust emission intensity was calculated for two traffic conditions: free-flowing and congested. The emission intensities were 1.31 kg/(min·km) and 3.08 kg/(min·km), respectively. By altering factors such as wind speed and canyon model parameters, the simulations demonstrated that street canyon morphology significantly affects exhaust pollutant diffusion patterns. Wide and short street canyon models facilitated faster diffusion, while high wind speeds increased the diffusion rate without altering the pollutant diffusion path, thereby reducing exhaust pollutant concentrations. The wind direction angle also influenced the pollutant diffusion path, with wind directions closer to the street canyon axis being more conducive to pollutant dispersion.

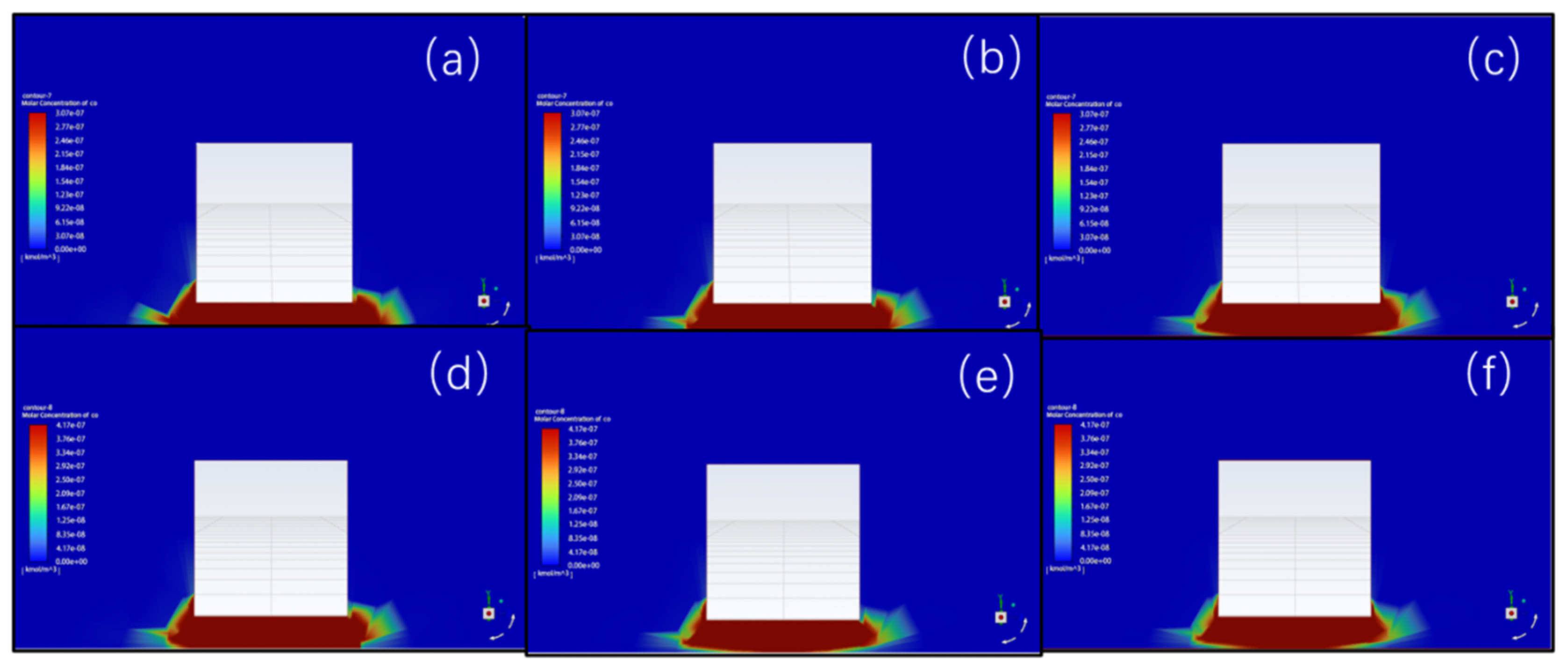

Evaluation of Photocatalytic pavement for exhaust mitigation: Based on reductions in line-source emission strength, the application effects of exhaust-degrading ecological pavement materials were assessed. Simulations were conducted for three scenarios with emission reduction rates of 0%, 30%, and 50%, and the pollutant concentration fields were calculated for the XZ-1.5 m plane. The results showed that reducing the emission intensity did not affect the diffusion pattern of pollutants, but concentrations of pollutants at the street’s end and near buildings significantly decreased. The CO concentration reduction at representative point R ranged from 28.70% to 56.72%. This indicates a reduction in exhaust pollutant concentrations at the human breathing height within activity zones, demonstrating that the application of exhaust-degrading ecological pavement materials can significantly improve air quality in the roadway environment.

In summary, this study established an integrated framework to assess air quality deterioration in road areas, linking macro-scale traffic activity to micro-scale pollutant dispersion.

The practical implications of these findings are twofold. Firstly, the equivalent-pollution method provides a valuable tool for environmental impact assessments, enabling a more health-centric evaluation of traffic policies. Secondly, the CFD results offer direct guidance for urban planning, suggesting that optimizing street canyon geometry and selectively deploying photocatalytic pavements in critical areas can be effective strategies for mitigating exposure risks.

Despite the insights gained, this work opens up several avenues for future research. The immediate priority is the on-site validation of the simulated dispersion patterns. Furthermore, extending the model to account for chemical transformations between pollutants and conducting a thorough life-cycle cost–benefit analysis of mitigation technologies like photocatalytic pavement would significantly enhance the practical applicability and depth of future studies.