Abstract

Pascal’s triangle is a classical mathematical construct, historically studied for centuries, that organises binomial coefficients in a triangular array and serves as a cornerstone in combinatorics, algebra, and number theory. Herein, we propose to model it with Petri nets, a formal specification technique derived from discrete event systems. A minimal Petri net is created that generates Pascal’s triangle under a simple arithmetic rule. Token counts in each place coincide with binomial coefficients, providing a direct combinatorial interpretation. Two other classical structures emerge from this model: by colouring tokens depending on their parity, the Sierpiński triangle appears; by routing tokens randomly at each branching, the binomial distribution arises, converging to a Gaussian limit as depth increases. As a result, a single Petri construction unifies three mathematical objects: Pascal’s Triangle, Sierpiński’s Triangle, and the Gaussian distribution. This connection illustrates the invaluable potential of Petri nets as unifying tools for modelling discrete mathematical structures and beyond.

1. Introduction

Pascal’s triangle, one of the most fundamental structures in mathematics, has fascinated scholars for centuries. The triangle is often one of the first mathematical objects through which young scholars discover the connections between algebra and combinatorics, for instance, in the expansion of and . First studied in ancient China and later formalised by Blaise Pascal [1], the triangle provides a simple, yet powerful organization of binomial coefficients [2]. Beyond its elegance, Pascal’s triangle is deeply connected to numerous mathematical areas, including combinatorics [3], algebra [4], probability theory [5], and number theory [6]. Its visual and recursive nature also makes it a natural candidate for computational modelling [7]. An interesting structure closely tied to Pascal’s triangle is the Sierpiński triangle, one of the most famous fractal shapes that intrigues mathematicians [8,9,10,11]. In contemporary contexts, it has also found applications in other domains, such as computer science, for example, in the design of data centre architectures for cloud computing [12] or in the development of fractal-based authentication techniques [13].

Petri nets [14] are a classical, well-established tool for modelling of discrete-event systems with concurrency (parallel behaviour) [15]. They are widely used in computer science, engineering and other fields, among others, to model business processes [16], manufacturing [17] or cyber–physical systems [18]. Their interest comes from a simple graphical syntax linked to a precise mathematical semantics. Moreover, as Petri nets are a formal specification technique, several formal analysis and verification methods can be used to check their properties [19,20].

In this article, Pascal’s triangle is modelled with Petri nets. It extends our previous paper where Petri nets were applied to model and analyse the Collatz Conjecture [21]. In addition to their mathematical significance, these constructions also illustrate the aesthetic potential of Petri nets, bridging mathematics and art through the generation of rich patterns. It is shown how to use Petri nets for the generation of the three well-known mathematical objects: Pascal’s triangle, the Sierpiński triangle, and the Gaussian distribution.

The main contributions of this paper are the following:

- A Petri net model of Pascal’s triangle is proposed;

- The emergence of the Sierpiński triangle by parity is established within the model;

- The appearance of the Gaussian distribution by random routing is obtained;

- A short discussion of Petri net properties is provided.

The obtained results show that Petri nets, usually used for system modelling, can also give a compact, unified and relatively artistic view of classical structures in combinatorics, probability and fractals.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides some background on mathematical theory and Petri nets, showing the existing state-of-the-art. Section 3 proposes a Petri net model for Pascal’s triangle. Section 4 focuses on the Sierpiński triangle. Section 5 comes to the rectangular representation of the Sierpiński fractal, using parity colouring and Okabe–Ito palette. Section 6 proposes Kandinsky representation of the Petri net-based Pascal’s triangle. Section 7 adds some discussion on Gaussian emergence from random routing. Finally, Section 8 summarises and concludes the paper.

2. Theory Background

2.1. Mathematical Background

Pascal’s triangle is a classical mathematical structure constructed by arranging numbers in a triangular form [1]. It begins with a single 1 at the top, and each subsequent row is generated by placing 1 at both ends, while every inner entry is obtained as the sum of the two numbers directly above it. Blaise Pascal (1623–1662) is famous in France, not only as a mathematician, since he casually founded the theory of probability with Pierre de Fermat, but also as a physicist, since as one of the founders of hydrostatics he left his name on the SI unit of pressure, the Pascal (Pa). He is also quite renowned as a philosopher. His posthumous work Pensées [22] remains one of the most influential texts of French philosophy, illustrating the importance of his intellectual legacy.

« L’homme n’est qu’un roseau, le plus faible de la nature; mais c’est un roseau pensant. »

“Man is but a reed, the weakest in nature; but he is a thinking reed.” Source: Pensées [22].

A closely related structure is the Sierpiński triangle, obtained by recursively subdividing an equilateral triangle into smaller equilateral triangles and removing the central one at each step [8]. Interestingly, when Pascal’s triangle is reduced modulo 2, the resulting pattern of odd and even entries converges to the Sierpiński triangle. This connection highlights a deep interplay between discrete mathematics and fractal geometry, linking a classical combinatorial object with a self-similar geometric structure. The triangle is named after the Polish mathematician Wacław Sierpiński (1882–1969). It subsequently became the logo of the renowned Polish Mathematical Olympiad (homepage: https://om.sem.edu.pl/english_templates/about/, accessed on 23 September 2025). Nevertheless, the geometric pattern was already known as a decorative motif long before the contributions of Sierpiński.

Another important connection arises from number theory, namely Lucas’s theorem, which provides a way to compute binomial coefficients modulo a prime number [23]. This theorem not only generalises the reduction of Pascal’s triangle modulo 2, which leads to the Sierpiński triangle, but also reveals rich modular patterns when Pascal’s triangle is considered with respect to other primes.

Building upon these classical mathematical structures, one can also approach Pascal’s triangle from a more visual and artistic perspective. The well-prepared and accessible visualisations can help to grasp the idea and help understand complex issues, whether it concerns mathematics [24,25] or computer science [26,27]. In particular, the Kandinsky representation [28] offers a way of encoding mathematical relations into abstract visual patterns, where structural properties such as symmetries, repetitions, or modular reductions (as in Lucas’ theorem) are reflected through colours, shapes, and spatial arrangements. Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944), the pioneer in abstract paintings, emphasised the power of colors [29]. The perspective not only complements traditional graph-theoretical or number-theoretical analyses but also provides a bridge between rigorous mathematics and visual intuition, thereby broadening the interpretative and communicative potential of Pascal’s triangle and its related structures. This interdisciplinary perspective underscores how mathematical structures such as Pascal’s triangle can transcend their symbolic form, revealing aesthetic and conceptual patterns that resonate across both science and art.

Recent studies have revisited Pascal’s triangle from both computational and visualisation perspectives. Ziobro [30] formally constructed Pascal’s triangle using the Mizar system, proving Lucas’s theorem and strengthening its algorithmic formalisation. Kosobutskyy et al. [31] have recently examined the relationship between Newton’s binomial, Pascal’s triangle, and the Collatz problem. Mereb [32] examined determinants of matrices derived from Pascal’s triangle, highlighting algebraic structures relevant for computational modelling. Beiu et al. [7] introduced a continuous surface associated with Pascal’s triangle, enabling novel geometric visualisations. Yamagami and Taniguchi [33] generalised Lucas’s result, exploring modular and symmetrical properties of generalised Pascal’s triangles. More recently, Chen [34] analysed both Pascal’s triangle and its 3D extension (Pascal’s pyramid), connecting them to Fibonacci-like sequences and combinatorial applications. Together, these works clearly demonstrate that Pascal’s structure continues to inspire both theoretical advances and computational representations.

Several formal mechanisms have been successfully employed so far to model combinatorial structures and fractals. One prominent example is cellular automata, where elementary rules can generate fractal patterns, such as the Sierpiński triangle [35]. Another approach is grammar-based Lindenmayer systems (L-systems), which were originally developed to model plant growth but have been widely applied to generate fractals through simple rewriting rules [36]. Substitution systems and iterated function systems use formal rewriting or contraction mappings to produce self-similar fractal-like graphs [37]. Finally, algebraic or matrix-based automata and graph-rewriting systems provide another angle—by applying local linear transforms or graph/substitution rules, one can reproduce number-theoretic regularities and recursive triangular arrays, bridging combinatorics and discrete dynamical systems [38,39].

In this paper, we propose adding a Petri-net-based modelling paradigm to this landscape. We fill the gap by encoding the structure of Pascal’s triangle (modular rows, symmetry, parity) into an abstract visual style inspired by Kandinsky’s compositional principles, combined with the Petri nets formalism, thereby integrating combinatorial mathematics, control theory, number theory, and artistic abstraction. We also generate Sierpiński fractals, both in black-and-white and coloured versions.

2.2. Petri Nets

Some basic concepts from the Petri net theory are introduced to enhance clarity; the notions are based on the classical works [14,40].

Formally, a Petri net can be defined as a four-tuple , where P is a finite set of places (represented graphically with circles), T is a finite set of transitions (bars), is a finite set of arcs (arrows), and is an initial marking (a dot inside a place). In a Petri net, places are connected to transitions exclusively through arcs, and vice versa. Nevertheless, by designing the net structure appropriately, it is possible to represent diverse behaviours, such as choice and concurrency.

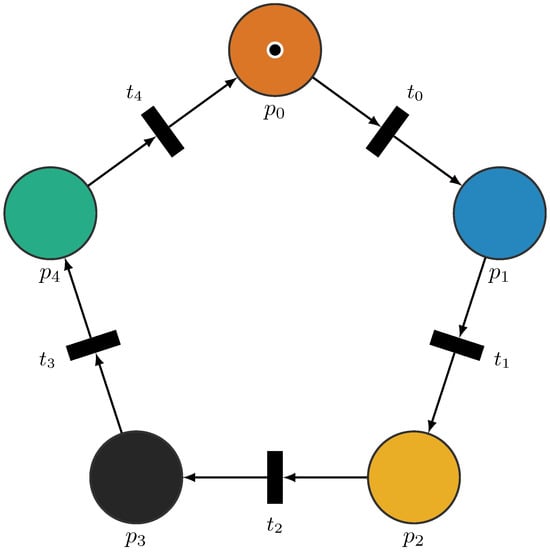

A marking specifies the distribution of tokens across all places. A transition is enabled when each of its input places contains at least one token. Once enabled, the transition may fire, removing a token from each input place and adding one to each output place. A marking is said to be reachable from another if it can be obtained through a sequence of transition firings. A Petri net is live if, from any reachable marking, it is always possible to eventually fire every transition, either directly or after a sequence of other firings. It is safe if, in all reachable markings, no place ever contains more than one token. A simple Petri net example is shown in Figure 1. The net consists of five places (–) arranged in a regular pentagon, each one coloured according to the Okabe–Ito palette (vermillion, blue, orange, black, and green). Five transitions (–) connect the places cyclically, and a single token is initially placed in . This means that the first active colour in the sequence will be vermillion.

Figure 1.

A simple Petri net with five places coloured using the Okabe–Ito palette and one token initially in place at .

At the end of the last century, the three scientists—Karam, Hassanien, and Nakajima (from the Tokyo Institute of Technology in Japan)—made the first contributions to the use of Petri nets to generate fractals. The dynamics of Petri nets and the solution of its reachability problem were used to generate self-similar fractal images [41,42]. Two methods, called PN-escape-time and PN-chaos were proposed, the first one modifying the escape-time algorithm and the second one based on the chaos game. The escape-time modified algorithm was studied in more detail in [43]. The authors claim that the computational efficiency of their proposed methods makes fractal-like image synthesis reliable for interactive machines. In a more recent approach (2015), Kuberal et al. [44] proposed a model to generate triangular arrays using Petri net structure (the Triangular Array Token Petri Nets were introduced). These pioneering and later developments collectively demonstrate how Petri nets can serve as a formal and computational framework for generating self-similar and combinatorial structures, bridging discrete dynamics with fractal geometry. However, although some works have shown the power of Petri nets, there is still a clear gap in this area, which our paper aims to address.

3. A Petri Net for Pascal’s Triangle

3.1. General Rule

A layered Petri net can be defined in order to reproduce Pascal’s triangle. Each of the layers corresponds then to one layer of the resulting triangle. To make the construction of the Pascal Petri net explicit, a formal definition can be provided. The Petri net is denoted by , where P is the set of places, T the set of transitions, F the flow relation (weighted or unweighted), and the initial marking.

with the flow relation

The initial marking is defined as follows:

This formal definition ensures that the model is reproducible.

Let denote a place at level and position . For each such place, one transition is introduced that consumes one token from and produces two tokens, one in and one in . The initial marking contains a single token in the root place in the top layer.

The resulting Petri net is as follows:

- Bounded—since each place can contain a finite number of tokens equal to the corresponding Pascal’s coefficient;

- Acyclic—since each transition at level n Produces tokens at level n+1 (no backward connection);

- Not live—because transitions are permanently disabled once their input places are emptied;

- Not reversible—as it is impossible to come back to the initial state (no backward arc).

Generally, the net, as well as its layers, tends to infinity, generating larger and larger fragments. After ℓ steps, tokens are distributed among the places of row ℓ, with counts corresponding to the binomial coefficients. It is important to note that each of the layers is computed completely before coming to the next one.

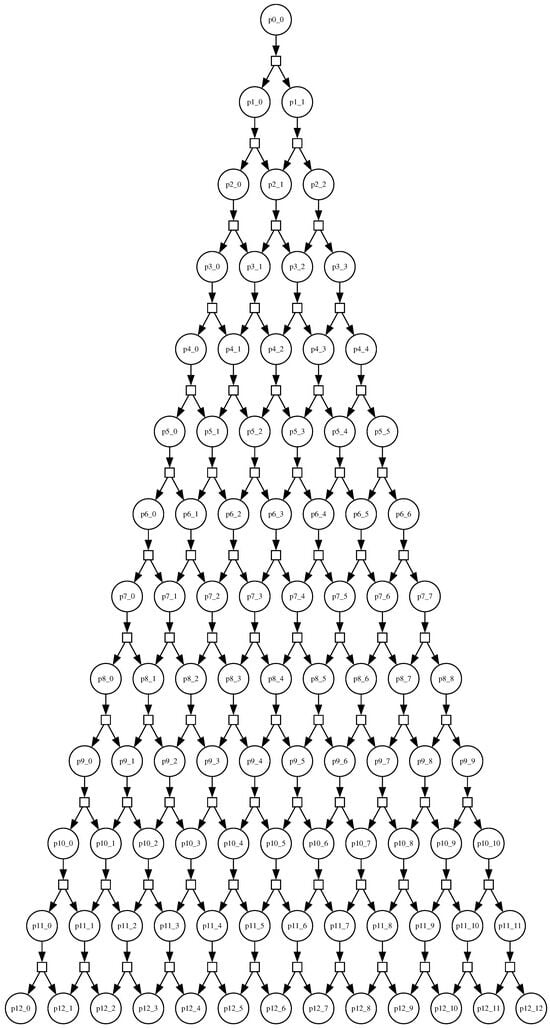

After presenting the structure, the Petri net itself is depicted below in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Petri net construction of Pascal’s triangle up to depth 12.

3.2. Binomial Coefficients as Token Counts

The token dynamics of the Petri net follow directly the recursive definition of the binomial coefficients. At each step, a token in place gives rise to one token in and one in . This corresponds exactly to the recurrence, written as follows:

with the convention that if .

After ℓ steps of firing transitions from the initial marking, the number of tokens in place is equal to the binomial coefficient .

The proof is by induction on the level ℓ. For , the initial marking contains exactly one token in , which coincides with . Assume the property holds for level ℓ. At level , the number of tokens in place is equal to the number of tokens produced from and . By the induction hypothesis, these counts are and respectively, which sum to by Pascal’s rule.

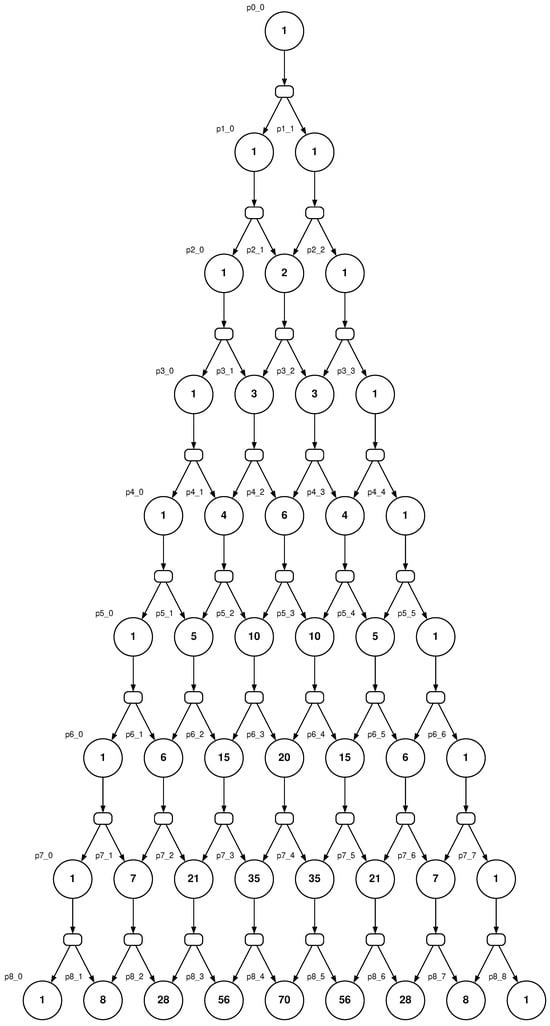

Hence, the Petri net does not merely suggest but exactly computes Pascal’s triangle through its marking evolution. An illustrative example is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Natural encoding of binomial coefficients with a Petri net forming Pascal’s triangle.

3.3. Computational Complexity and Marking-Based Propagation

Some simple calculations show that classical transition firing was rapidly difficult to handle:

- For each line k, there are k + 1 places; therefore, for the depth n, the number of places is (n + 1)(n + 2)/2.

- The number of transitions is n(n + 1)/2 (because the last line has no transitions).

- The number of tokens doubles at each line, and the number of firings rapidly becomes difficult to handle (sum of powers of 2 at depth n):

To solve this issue, we implemented a marking-based simulation (all the tokens of one place are fired at the same time):

- For each line k, the number of places is still (n + 1)(n + 2)/2.

- The number of transitions is still n(n + 1)/2.

- The number of firing becomes 2 for each transition, therefore n(n + 1).

This number for firing is comparable to the classical iterative construction of Pascal’s Triangle, leading to a quadratic rather than exponential computational complexity.

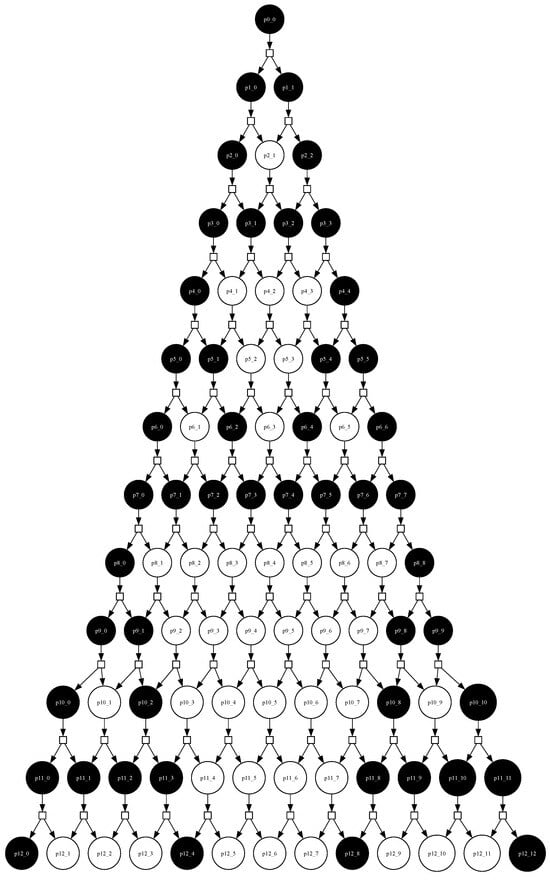

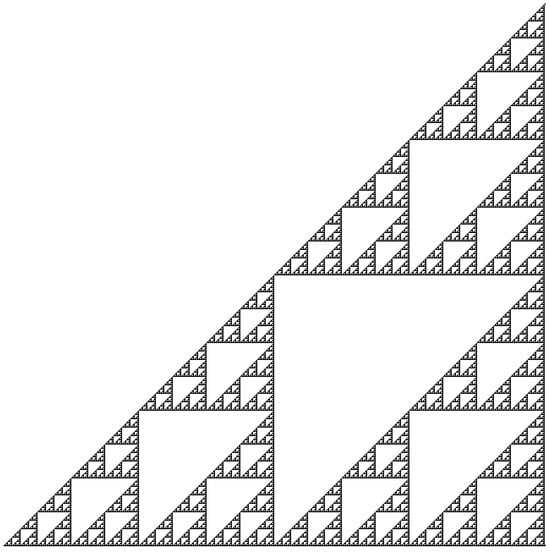

4. Emergence of the Sierpiński Triangle

When the number of tokens in each place is considered modulo two, a striking pattern appears: places corresponding to odd coefficients are coloured black, and those corresponding to even coefficients white. The resulting figure is the classical Sierpiński triangle (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Petri net modelling Pascal’s triangle is coloured according to the parity of binomial coefficients; black places correspond to odd values, and white places to even values, revealing the Sierpiński pattern.

This phenomenon is explained by a number-theoretic result due to Lucas [45] and its modern demonstration [46].

For any non-negative integers , the binomial coefficient is odd if, and only if, the following is met:

where & denotes the bitwise AND operator in base 2.

Implementation Notes (Python)

The figures were generated by a small Python program (version 3.11.4) that constructs the Pascal’s Petri net with parity colouring. Oddness of binomial coefficients is tested using Lucas’ theorem in base two, which avoids computing the binomial coefficients explicitly. The test reduces to a single bitwise AND:

def binom_is_odd(n: int, k: int) -> bool:

return (k & (n - k)) == 0

This implementation avoids large-integer arithmetic and enables fast rasterisation at high depths.

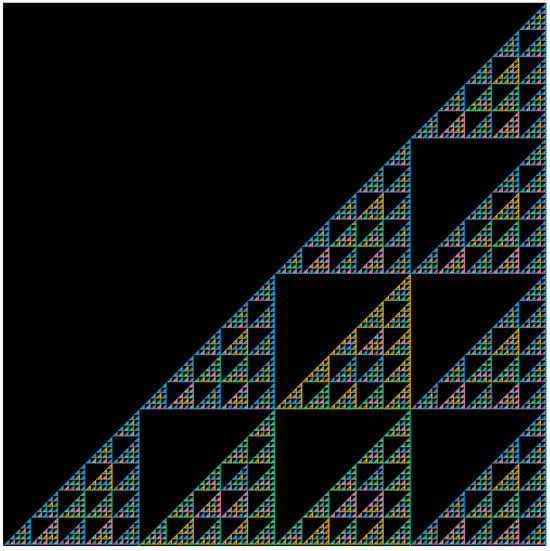

5. Rectangular Representation

5.1. General Rule

The triangular display of Pascal’s coefficients modulo two produces the Sierpiński triangle. An alternative viewpoint is to embed the construction in a full rectangular grid starting from the previously presented Petri net. Each pixel of this grid is computed as follows:

- Transitions are not taken into account.

- Only the number of tokens in each place is considered.

- Each pixel is characterised by a depth n and a position k with .

- For each depth n and each position k, the value is computed and coloured black if odd, white if even.

- Empty positions (when there is no place corresponding to the Petri net) are left blank, resulting in a rectangular array where each row contains valid entries.

This representation highlights diagonal and periodic structures that are less visible in the triangular form. Figure 5 illustrates the rectangular version up to depth , where the same binary compatibility condition of Lucas determines the black and white pattern.

Figure 5.

Large Sierpiński fractal generated from the Petri net of Pascal’s triangle using parity colouring.

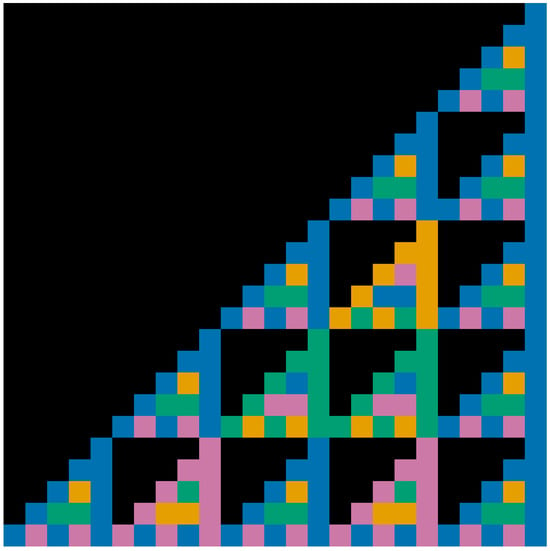

5.2. Rectangular Representation Modulo Five with Okabe–Ito Palette

Following the obtained results presented before, including the binary case (modulo 2), richer structures can also be generated by applying a different modulo to the number of tokens. For example, choosing generates a highly regular fractal decomposition of the rectangular display. The computation follows the same principle as in the binary case, but with the well-known Okabe–Ito coloured palette [47] replacing the black and white scheme presented in the previous section. The rules can be specified as follows:

- Each pixel corresponds to a place with .

- The value is computed.

- The residue is mapped to the Okabe–Ito palette, chosen for its clarity:

- black;

- blue (#0072B2);

- orange (#E69F00);

- vermillion (#D55E00);

- green (#009E73).

- Empty positions with are black.

The resulting image exhibits large triangular voids (corresponding to multiples of five) alternating with self-similar coloured sub-triangles. The diagonals of binomial ones produce continuous blue bands, and each square block of side contains a scaled copy of the entire structure, in accordance with Lucas’s theorem. The fractal nature of the construction is therefore even more apparent than in the binary case, with colour enhancing the modular periodicity. As shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7—with a zoom on the upper region of the triangle—the self-similar structure is revealed.

Figure 6.

Fractal generated from the Petri net of Pascal’s triangle using the Okabe–Ito modular colouring modulo five.

Figure 7.

Zoom on the upper region of the triangle, revealing its self-similar structure.

5.3. Implementation Notes on the Okabe–Ito Palette

The Okabe–Ito Palette was chosen for two main reasons. First, from an artistic point of view, it is perfectly balanced with the Sierpiński triangle fractal. After testing several alternative palettes, this one was visually the most pleasant. The Okabe–Ito palette was also particularly convenient because it allows up to eight colours to explore the results obtained with different modulos (e.g., modulo 3, modulo 7).

5.4. Implementation Notes (Python)

Figure 6 was generated by the same Python program as presented previously extended to implement Lucas’ theorem in base 5. According to Lucas’ theorem, for integers with base–5 expansions , , one has the following:

This enables testing the residue class without computing large binomial coefficients. For modulo 5, no “bitwise” command already exists. Therefore, the implementation proceeds by scanning the base–5 digits of n and k:

def binom_mod5(n: int, k: int) -> int:

res = 1 # initialize result modulo 5

while n or k: # loop while base-5 digits remain

ni, ki = n % 5, k % 5 # extract least significant base-5 digits

if ki > ni: # if any digit of k > digit of n -> zero

return 0

res = (res * comb(ni, ki)) % 5 # multiply by small binomial,

# reduce modulo 5

n //= 5; k //= 5 # drop processed digit (int. div. by 5)

return res # final result modulo 5

This avoids large-integer arithmetic and ensures efficient rasterisation up to depth.

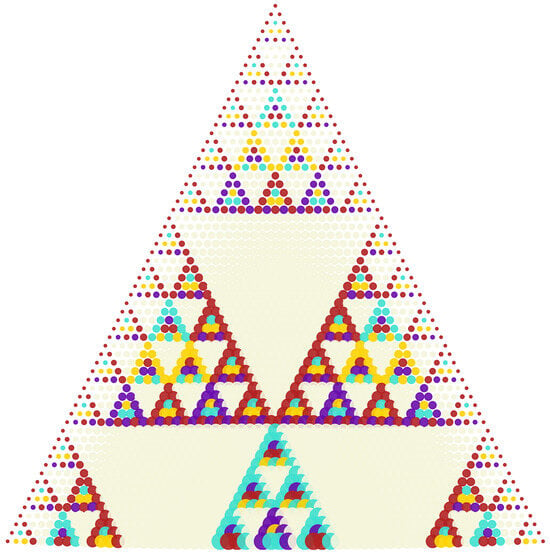

6. Kandinsky Representation of the Pascal’s Petri Net

Another artistic representation of Pascal’s Petri net can be obtained by imitating Kandinsky’s style. The mechanism is similar to previous sections, but this time each place will be represented by a circle, the radius of which will depend on the number of tokens it contains. A Kandinsky-inspired view is presented in Figure 8. This generated image can already be treated as a work of art. Various sizes and colours of the particular elements fit each other visually.

Figure 8.

Kandinsky-inspired visualisation of the Pascal’s Petri net modulo five.

The visualisation follows two simple rules:

- The colour of each circle is determined by the number of tokens . A Kandinsky-inspired palette is used, written as follows:

- beige (#f5f5dc, neutral background);

- carmine red (#b22222);

- turquoise (#40e0d0);

- lemon yellow (#ffd300);

- deep violet (#6a0dad).

- The radius of each circle directly depends on the coefficient. To balance the growth of binomial values, a logarithmic scaling is applied:where is a base radius and a scaling factor. This ensures that small coefficients (near the borders) appear as small dots, while central coefficients are much larger.

Implementation Notes (Python)

For the Kandinsky visualisation, the construction is based on the same Petri net rules as before, but this time Matplotlib (version 3.8) library is used rather than Graphviz. The aim is not to display the Petri net itself, but only the markings, each place being represented as a coloured circle.

In this simplified approach, no modular reduction is enforced: the raw binomial coefficients are computed, and their magnitude is encoded by the radius of the circle. A logarithmic scaling is applied to compress the very large values appearing in the centre of the triangle:

r = r0 + alpha * np.log1p(comb(n, k))where comb(n,k) is the binomial coefficient, r0 is a base radius, and alpha a scaling factor. The colour of the circle is selected from a predefined Kandinsky-inspired palette (red, turquoise, yellow, violet, and beige).

This method is convenient for artistic exploration—with different shapes and palettes, it can provide numerous visual representations.

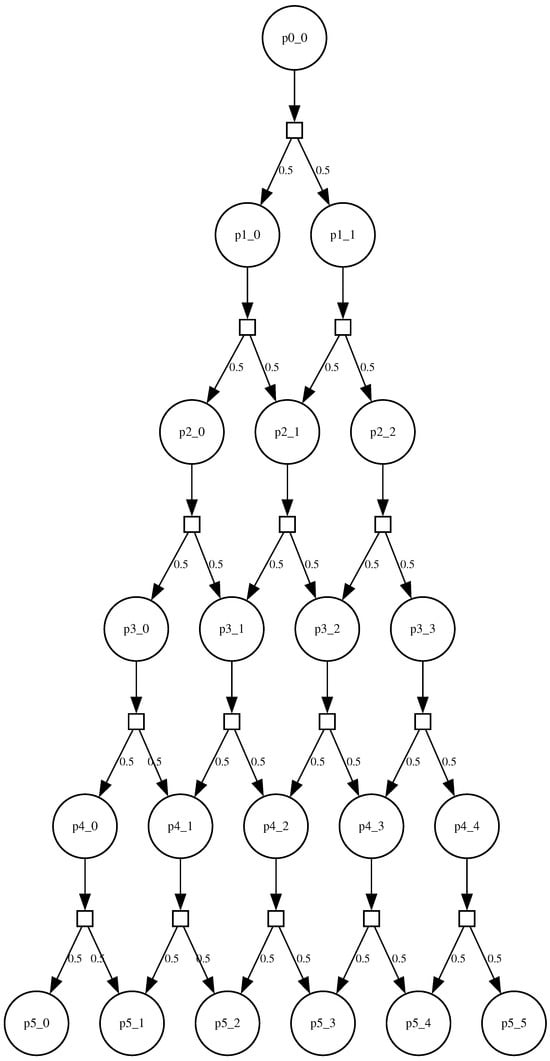

7. Gaussian Emergence from Random Routing

The equiprobable Petri net provides a natural playground for modelling stochastic trajectories in the spirit of Ulam’s [48] original idea of statistical simulation.

If a token in place is routed randomly to one of its two successors, the final distribution of tokens after N steps coincides with a binomial law. Specifically, with probability p of moving right and of moving left, the number of tokens in place is calculated as follows:

From each place at level n, two transitions lead to the next depth : one towards position k and the other towards position . Both transitions are taken with equal probability , so that a single token, initially placed at the root , can generate a stochastic trajectory through the network.The Petri net becomes stochastic because each token is routed randomly to one of its two output transitions instead of being duplicated deterministically, as presented in other sections.

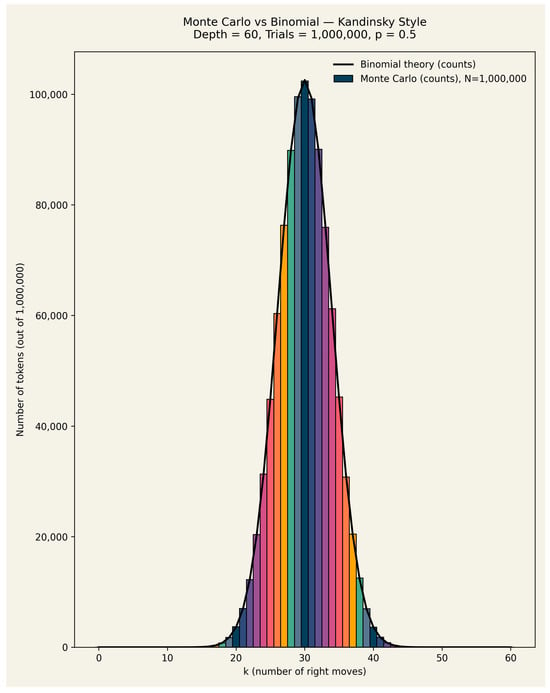

The stochastic Petri net is sketched in Figure 9, and the empirical distribution over trials appears in Figure 10.

Figure 9.

Equiprobable Petri net adapted from Pascal’s triangle.

Figure 10.

Token distribution obtained from 1,000,000 Monte-Carlo trials compared with the binomial distribution, on a Kandinsky palette.

When , the distribution is symmetric and centred at . As N grows, the binomial distribution approaches the Gaussian (normal) distribution by the classical de Moivre–Laplace theorem [49]. In the Petri net framework, the random dynamics of tokens thus lead from a purely combinatorial construction (Pascal’s triangle) to a probabilistic limit law (the Gaussian distribution).

If the tokens are routed stochastically toward the two places below, after n steps, the number of tokens follows a binomial distribution; then as n grows, the tokens’ distribution tends towards the Gaussian distribution according to the de Moivre–Laplace theorem:

where is the cumulative distribution function of the standard normal law [49].

8. Conclusions

In this article, it has been shown that a basic Petri net, perhaps the most elementary one conceivable, leads naturally to beautiful mathematical objects such as Pascal’s triangle. At the combinatorial level, token counts coincide exactly with binomial coefficients. Moreover, thanks to the expressive power of Petri nets, it is possible to establish connections between mathematical objects such as Gaussians and, more generally, to explore domains such as algebra, fractals, probability theory, and even art. The astonishing power of Petri nets cannot be overemphasised, not only as a modelling tool but also as a framework for mathematical exploration.

One may even speculate that Blaise Pascal himself, with his fascination for patterns, probability, and the human condition, would have been delighted by the outstanding power of Petri nets. Our findings highlight the versatility of Petri nets, showing that they are able not only to model dynamic systems but also to provide fresh perspectives on long-studied mathematical structures. They emerge as a bridge between formal specification and mathematical exploration, offering both rigour and aesthetic insight. They also open a path toward algorithmic art, where formal models give rise to visually interesting patterns. The Petri net construction of Pascal’s triangle carries engineering relevance. Indeed, from an educational perspective, encoding the logic of Pascal’s triangle with a Petri net provides an intuitive entry point to Petri net modelling for young engineers. Since most students encounter Pascal’s triangle early in their education, revisiting it in a formal, system-orientated framework offers a familiar and intellectually stimulating learning experience. For more experienced engineers, the approach can be used to describe uncertainty propagation in various systems, e.g., cyber–physical or quality control systems, supporting probabilistic modelling. Moreover, the stochastic routing of tokens closely resembles engineering models of flow propagation in communication and processing systems.

As discussed in the article, some limitations have to be acknowledged. As the model scales, the number of fireable transitions grows combinatorially, leading to actual challenges in computation and visualisation.

Plans for the future include an exploration in the direction of visual or generative art, in the same spirit as Verrill’s work on hinged tilings and classroom-based generative explorations [50,51]. It would also be interesting to explore the wider applicability of the concepts considered here, especially Fibonacci and Tribonacci sequences, as indicated in [34]. Finally, it will be essential to use Petri net modelling tools that are sufficiently flexible to handle scalability and combinatorial issues.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M. and I.G.; methodology, D.M.; software, D.M.; investigation, D.M. and I.G.; writing—original draft preparation, D.M. and I.G.; writing—review and editing, D.M. and I.G.; visualisation, D.M.; supervision, I.G.; project administration, I.G.; funding acquisition, I.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by a programme of the Polish Ministry of Science under the title ‘Regional Excellence Initiative’, project no. RID/SP/0050/2024/1.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed at the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Michel C. at Thales Alenia Space for pointing out, many years ago, that equal 50/50 routing in the Pascal’s Petri net should lead to a Gaussian limit, an observation that motivated part of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pascal, B. Traité du Triangle Arithmétique, 1st ed.; Manuscript, first published posthumously in 1665, 1654; Guillaume Desprez: Paris, France, 1665. [Google Scholar]

- Aliu, A.; Rexhepi, S.; Iseni, E. Efficiency of Understanding Some Mathematical Problems by Means of Pascal’s Triangle. Int. Electron. J. Math. Educ. 2023, 18, em0753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, P.; Pedersen, J. Looking into Pascal’s triangle: Combinatorics, arithmetic, and geometry. Math. Mag. 1987, 60, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, P.; Pedersen, J. Relating Geometry and Algebra in the Pascal Triangle, Hexagon, Tetrahedron, and Cuboctahedron Part I: Binomial Coefficients, Extended Binomial Coefficients and Preparation for Further Work. Coll. Math. J. 1999, 30, 170–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, M.A.; Padi, T.R.; Gandhi, M.A. Combinatorial Probability Distribution for 2nd Diagonal Elements of the Pascal’s Triangle with Sequence of Natural Numbers in Prime Diagonal. Triangle 2023, 1, 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Mathonet, P.; Rigo, M.; Stipulanti, M.; Zénaïdi, N. On digital sequences associated with Pascal’s triangle. Aequ. Math. 2023, 97, 391–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiu, V.; Dăuş, L.; Jianu, M.; Mihai, A.; Mihai, I. On a surface associated with Pascal’s triangle. Symmetry 2022, 14, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Cruz, M.Á.; Patiño-Ortiz, J.; Patiño-Ortiz, M.; Balankin, A.S. Some Insights into the Sierpiński Triangle Paradox. Fractal Fract. 2024, 8, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyörälä, A.; Shmerkin, P.; Suomala, V.; Wu, M. Covering the Sierpiński carpet with tubes. Isr. J. Math. 2025, 265, 769–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, T.D. The Beauty of the Symmetric Sierpiński Relatives. Proceedings of Bridges 2018: Mathematics, Art, Music, Architecture, Education, Culture, Stockholm, Sweden, 25–29 July 2018; pp. 163–170. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, S.; Settle, B. n-Flake Variations. In Proceedings of the Bridges 2024 Conference Proceedings, Richmond, VA, USA, 5 July 2024; pp. 479–482. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, H.; Shiraz, M.; Gani, A.; Whaiduzzaman, M.; Khan, S. Sierpiński triangle based data center architecture in cloud computing. J. Supercomput. 2014, 69, 887–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Rafique, H.; Arshad, T.; Alqarni, M.A.; Chauhdary, S.H.; Bashir, A.K. A fractal-based authentication technique using Sierpiński triangles in smart devices. Sensors 2019, 19, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, T. Petri nets: Properties, analysis and applications. Proc. IEEE 1989, 77, 541–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girault, C.; Valk, R. Petri Nets for Systems Engineering: A Guide to Modeling, Verification, and Applications; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Aalst, W.M. Business process management as the “Killer App” for Petri nets. Softw. Syst. Model. 2015, 14, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobelna, I.; Karatkevich, A. Challenges in Application of Petri Nets in Manufacturing Systems. Electronics 2021, 10, 2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobelna, I.; Wiśniewski, R.; Wojnakowski, M. Specification of Cyber-Physical Systems with the Application of Interpreted Nets. In Proceedings of the IECON 2019—45th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Lisbon, Portugal, 14–17 October 2019; Volume 1, pp. 5887–5891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatkevich, A. Dynamic Analysis of Petri Net-Based Discrete Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Grobelna, I.; Wiśniewski, R.; Grobelny, M.; Wiśniewska, M. Design and Verification of Real-Life Processes With Application of Petri Nets. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2017, 47, 2856–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailland, D.; Grobelna, I. A Novel Approach to the Collatz Conjecture with Petri Nets. Information 2025, 16, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascal, B. Pensées; Port-Royal: Paris, France, 1670. [Google Scholar]

- Meštrović, R. Lucas’ theorem: Its generalizations, extensions and applications (1878–2014). arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.3820. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, A.J. Review of research on visualization in mathematics education. Focus Learn. Probl. Math. 1989, 11, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Mancosu, P. Visualization in logic and mathematics. In Visualization, Explanation and Reasoning Styles in Mathematics; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 13–30. [Google Scholar]

- Abedalrahim, J.; Alsayaydeh, J.; Zainon, M.; Oliinyk, A.; Aziz, A.; Rahman, A.; Baharudin, Z.; Teknologi, F.; Elektrik, K.; Elektronik, D.; et al. The development of system for algorithms visualization using SIMJAVA. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2020, 15, 3024–3034. [Google Scholar]

- Alsyayadeh, J.A.J.; Irianto; Aziz, A.; Chang, K.X.; Hossain, A.Z.; Herawan, S.G. Face recognition system design and implementation using neural networks. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2022, 13, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Yu, J. Generating abstract paintings in Kandinsky style. In SIGGRAPH Asia 2013 Art Gallery; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Murata, J. Seeing the Invisible: Kandinsky and the Multi-dimensionality of Colors. In Phenomenology and the Arts: Logos and Aisthesis; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ziobro, R. Pascal’s Triangle and Lucas’s Theorem. Formaliz. Math. 2024, 32, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosobutskyy, P.; Yedyharova, A.; Slobodzyan, T. From Newton’s Binomial and Pascal’s Triangle to Collatz’s Problem. Comput. Des. Syst. Theory Pract. 2023, 5, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mereb, M. On Determinants of Matrices Related to Pascal’s Triangle. J. Comb. Theory Ser. A 2024, 200, 105803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagami, S.; Taniguchi, T. A Generalization of Lucas’ Theorem and Symmetries of Pascal’s Triangle. Integers 2020, 20, A77. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X. Properties of Pascal’s Triangle and Pascal’s Pyramid with Applications. Theor. Nat. Sci. 2025, 84, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gütschow, J.; Nesme, V.; Werner, R.F. The fractal structure of cellular automata on abelian groups. In Discrete Mathematics & Theoretical Computer Science: Proceedings of the Automata 2010—16th Intl. Workshop on CA and DCS, Nancy, France, 14–16 June 2010; DMTCS: Nancy, France, 2010; pp. 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusinkiewicz, P.; Hanan, J. Lindenmayer Systems, Fractals, and Plants; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 79. [Google Scholar]

- Neroli, Z. Fractal dimensions for iterated graph systems. Proc. R. Soc. A 2024, 480, 20240406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarocchi, M. Conjugacy in rearrangement groups of fractals. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.16613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skums, P.; Bunimovich, L. Graph fractal dimension and the structure of fractal networks. J. Complex Netw. 2020, 8, cnaa037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, R.; Alla, H.; David, R.; Alla, H. Discrete, Continuous, and Hybrid Petri Nets; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Karam, H.; Hassanien, A.E.; Nakajima, M. Petri Net Modeling Methods For Generating Self-Similar Fractal Images. In ITE Technical Report 22.45; The Institute of Image Information and Television Engineers: Minato City, Japan, 1998; pp. 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Karam, H.; Hassanien, A.E.; Nakajima, M. Fractal image generation based on Petri net theory. In Proceedings of the ICAT’98 International Conference on Artificial and Tele-Existence, Gifu, Japan, 18–20 November 1998; pp. 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, H.K.; Hassanien, A.E.; Nakajima, M. Escape-time modified algorithm for generating fractal images based on petri net reachability. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. 1999, 82, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar]

- Kuberal, S.; Kalyani, T.; Thomas, D.; Kamaraj, T. Petri net generating Triangular arrays. Proc. Comput. Sci. 2015, 57, 642–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, E. Théorie des Nombres; Gauthier-Villars: Paris, France, 1891. [Google Scholar]

- Abu Salem, K.M. On the Sierpiński Gasket and Pascal’s Triangle Modulo a Prime. Am. Math. Mon. 2001, 108, 754–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okabe, M.; Ito, K. Color Universal Design (CUD): How to Make Figures and Presentations That Are Friendly to Colorblind People. 2008. Available online: https://jfly.uni-koeln.de/color/ (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Kosobutskyi, P.; Lobur, M.; Matviiv-Lozynska, Y. Method of statistical imitation, its creator S. Ulam and basic principles of application for random processes modeling. Comput. Data Anal. Model. (CDS) 2021, 3, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laplace, P.S. Théorie Analytique des Probabilités; Courcier: Paris, France, 1812. [Google Scholar]

- Verrill, H.A. Generative Art from the Calculus Classroom. In Proceedings of the Generative Art Conference (GA2022), Rome, Italy, 12–14 December 2022; pp. 183–189. [Google Scholar]

- Verrill, H.A. Fractals from Hinged Hexagon and Triangle Tilings. In Proceedings of the Bridges 2024: Mathematics, Art, Music, Architecture, Education, Culture, Richmond, VA, USA, 1–5 August 2024; pp. 327–334. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).