Abstract

We study heavy-ion collisions with a focus on pion production using an extended parity doublet model implemented in the “DaeJeon Boltzmann–Uehling–Uhlenbeck” (DJBUU) code. We consider three different systems—108Sn + 112Sn, 112Sn + 124Sn, and 132Sn + 124Sn—at a beam energy of A MeV, with an impact parameter of 3 fm, and compare our results with the SπRIT data. Since one of the key features of the parity doublet model is the existence of a chiral-invariant mass that contributes to the nucleon mass, we investigate how pion production depends on the chiral-invariant mass in these heavy-ion collisions. We adopt the values of the chiral-invariant mass of 600, 700, and 800 MeV and find that the case with MeV best reproduces the experimental data. We also observe that a larger results in a higher maximum baryon density of nuclear matter produced during heavy-ion collisions.

1. Introduction

Chiral symmetry serves as a crucial link between quantum chromodynamics (QCD) and its low-energy effective theories. These effective theories have been successfully applied to describe low-energy phenomena, including pion–nucleon scattering, the masses of light mesons, and their decay processes. In this paper, we focus on how chiral symmetry influences the hadron mass. For an extensive review of chiral symmetry, see Refs. [1,2,3,4].

Understanding the origin of the hadron mass is a key problem in nuclear physics. As is well known, the current quark mass generated by the Higgs mechanism accounts for only about 2% of the nucleon mass. In nuclear physics, it is often proposed that the rest of the nucleon mass in the chiral limit can be explained by the quark–antiquark condensate in the QCD vacuum, which is responsible for spontaneous broken chiral symmetry. The parity doublet model (PDM) we study in this work postulates that the nucleon (hadron) mass includes an additional piece that is chirally invariant. This chiral-invariant mass () is the main focus of this work.

The PDM was introduced in Ref. [5] as an extended linear sigma model with the parity doubling of nucleons, and it was studied in detail in Ref. [6]. By analyzing the partial decay width of in free space, which is the chiral partner of the nucleon within the PDM framework, the chiral-invariant nucleon mass was determined to be MeV [5,6].

The PDM has been employed in numerous studies to explore the properties of dense matter, for example, in Refs. [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. In dense matter, the saturation properties of nuclear matter can be used to constrain the value of . In Ref. [8], it was shown that the value of must be in the range 300–800 MeV to properly describe empirical properties of symmetric nuclear matter. A liquid–gas phase transition at normal nuclear density and a chiral transition at higher density were studied with MeV [10]. In Ref. [13], the dilaton-implemented hidden local symmetry Lagrangian with baryon fields was constructed to investigate the properties of dense matter, and it was argued that the chiral-invariant mass is about 0.7–0.8-times the nucleon mass. An extended parity doublet model with a six-point interaction of the meson was introduced to study asymmetric nuclear matter in Ref. [15]. The model effectively reproduces the properties of normal nuclear matter, with chiral-invariant mass ranging from 500 to 900 MeV. In Ref. [16], an extended SU(3) flavor parity doublet quark–hadron model with higher-order interaction terms of the scalar fields was established to study higher-order baryon number susceptibilities near both the chiral transition and the nuclear liquid–gas transition, where the chiral-invariant quark mass MeV was introduced.

Subsequent efforts were made to further narrow down the value of the chiral-invariant mass. For example, in Ref. [19], the authors calculated the binding energies and charge radii of selected nuclei for fixed ( MeV) and compared their results with experimental data. It turns out that MeV is preferred by the nuclear properties.

Neutron stars can also provide an additional constraint on the chiral-invariant masses. In Ref. [20], based on the tidal deformability determined from the observation of gravitational waves from the neutron star merger GW170817, it was found that the chiral-invariant masses are larger than approximately 600 MeV. Additionally, it was shown in Ref. [21] that the value of affects the nuclear equation of state at low density and has strong correlations with the radii of neutron stars. Using the constraint to the radius obtained by LIGO-Virgo and NICER, they found that is restricted as 600 MeV 900 MeV.

An effort was made to constrain the value of the chiral-invariant mass in Ref. [22], where the proton directed flow in 197Au + 197Au collisions at a beam energy of 400 MeV per nucleon in the laboratory frame, Ebeam = 400 A MeV, was calculated using a transport code called DaeJeon Boltzmann–Uehling–Uhlenbeck (DJBUU) and the results were compared with the FOPI data. They observed that the proton directed flows for = 600, 700, and 800 MeV are all roughly consistent with the experimental data. However, for MeV, the flow deviates from the experimental data at high rapidity.

The pion production in heavy-ion collisions near the threshold energies can be also useful data to constrain the chiral-invariant mass. Pions are produced by the decay of resonances, and the production of those resonances is explained through their behavior in finite nuclear density. The definition of effective masses for baryons in finite density in the parity doublet model is much different from typical Walecka-type models and has a large dependence on the choice of the chiral-invariant mass. A recent comparison of various transport models can be found in Refs. [23,24], while heavy-ion simulations with a focus on pion and resonance production were discussed in Ref. [25].

In this study, we investigate pion production within the extended parity doublet model [15] using the DJBUU transport model [22,23], with the aim of further constraining the value of . For this study, we consider three systems—108Sn + 112Sn, 112Sn + 124Sn, and 132Sn + 124Sn—at a beam energy of A MeV and an impact parameter of fm. Our results are compared with the SπRIT data [26]. Following Ref. [22], we exclude the case with MeV and perform simulations for = 600, 700, and 800 MeV.

2. Extended Parity Doublet Model in DJBUU

The Daejeon Boltzmann–Uehling–Uhlenbeck (DJBUU) code [22,27] solves the relativistic BUU equation with a mean-field potential:

where is the phase-space density of particle i, and is the field strength tensor associated with the vector field V. Here, we briefly describe the distinctive features of DJBUU. As in many BUU type models, DJBUU adopts the test particle method. Typically, the profile function of a test particle is of Gaussian type; however, in DJBUU, it is defined as

where , is the normalization constant, and and are positive integers. For , . We use this profile function rather than the conventional truncated Gaussian because it is exactly integrable and smoothly vanishes at a. That is, and . The default values are , , and for the position profile and for the momentum profile with .

Another distinctive feature of DJBUU is that it includes a model with chiral symmetry, in addition to a Walecka-type mean-field model. In the parity doublet model [5], the nucleon mass arises from both chiral symmetry breaking and a chiral-invariant mass term, the latter being independent of QCD chiral symmetry. To address the origin of the nucleon mass and the (partial) restoration of chiral symmetry in heavy-ion collisions, DJBUU includes an extended parity doublet model constructed in Ref. [15]. In the extended parity doublet model [15], vector mesons are introduced through the Hidden Local Symmetry (HLS) [28,29], and a six-point interaction of the meson is included. The extended model was found to provide a reasonable description of normal nuclear matter when the chiral-invariant nucleon mass was chosen within the range of 500 to 900 MeV [15].

The Lagrangian density of the extended parity doublet model is given by

where the baryon fields and transform as

Here, L and R denote the elements of and chiral symmetry group, respectively. The mesonic part of the Lagrangian is given by

We then take the mean field approximation: , , and . We note that, in this model, the -field is the chiral partner of the pion field. The vacuum expectation value of the field in free space is nonzero and equals the pion decay constant, but it decreases with increasing baryon number density due to (partial) chiral symmetry restoration.

After diagonalizing the baryon mass terms in Equation (3), we obtain the masses of the nucleon field N and its parity partner N*(1535):

where the term with a minus (plus) sign in front of corresponds to the nucleon () field, respectively. We use these masses in the relativistic BUU equation with a mean-field potential. We put an ‘*’ on the mass to indicate its in-medium value. In this work, we use Parameter set 1 in Ref. [19] (K = 240 MeV, MeV), which is also provided in Table 1. In addition, as in Ref. [19], we use the following nuclear matter properties to fix the parameters

Table 1.

Parameters used in this work with the compressibility MeV [19]. and are in units of MeV. Here, .

The model was further extended to include the baryons in Ref. [17] to investigate the transition from nuclear matter to strange matter.

3. Results

Using the DJBUU code and extended PDM model described in the previous section with the parameters given in Table 1, we study pion production in heavy-ion collisions to investigate the role of the chiral-invariant mass. For this study, we consider three different systems, 108Sn + 112Sn, 112Sn + 124Sn, and 132Sn + 124Sn, at a beam energy of A MeV with an impact parameter of 3 fm. We adopt the density- and isospin-dependent cross-section for the production proposed in Refs. [30,31], where the in-medium cross-section is given by

The isospin dependent parameters , , and correspond to the pp, np, and nn channels, respectively. We note that the baryon density-dependent cross-section was previously introduced in Ref. [30]. Also, in-medium inelastic nucleon–nucleon cross-sections with a scaling factor that depends on the effective masses of the scattering baryons were proposed in Refs. [32,33,34,35]. In this study, we employ the parameters from “Case 4” listed in Table 3 of Ref. [31], namely .

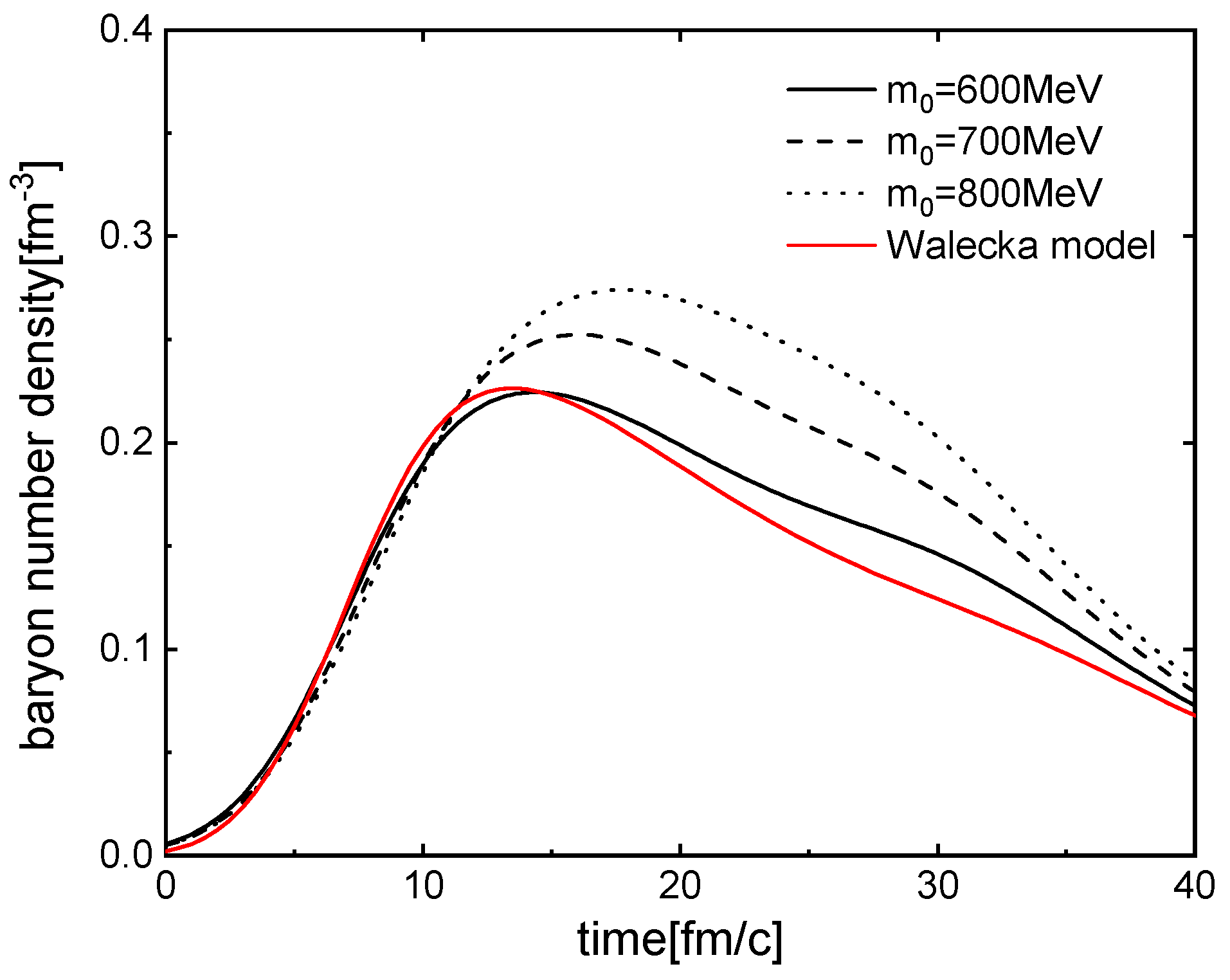

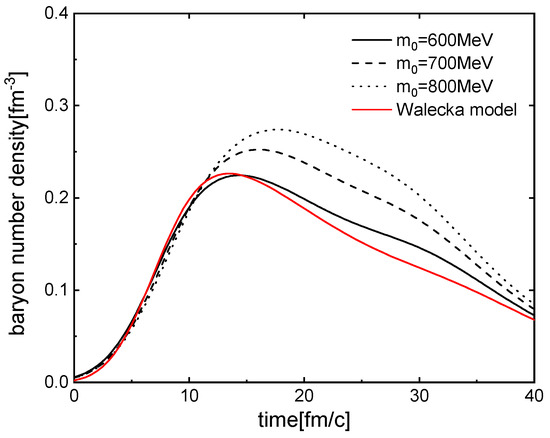

We first present in Figure 1 the baryon densities in 108Sn + 112Sn collisions at A MeV with the impact parameter of 3 fm, for and 800 MeV to examine whether the density changes with the chiral-invariant mass. For comparison, we also show the baryon density calculated using the parameter set I of Table 1 of the extended Walecka model [36]. It can be seen from Figure 1 that a larger leads to a higher maximum baryon density. This behavior can be attributed to the reduction in the coupling constants , associated with the attractive interaction, and , associated with the repulsive interaction, as increases.

Figure 1.

Time evolution of the baryon number densities at the center in 108Sn + 112Sn collisions at A MeV with the impact parameter of 3 fm. The solid, dash-dotted, and dotted lines are for and 800 MeV, respectively.

Our results, such as the nucleon effective masses and pion production yields, show a dependence on . Identifying the exact origin of this dependence is not straightforward. However, part of it can be attributed to the dependence of the scalar and vector meson mean fields, as shown in Figure 10 of Ref. [22].

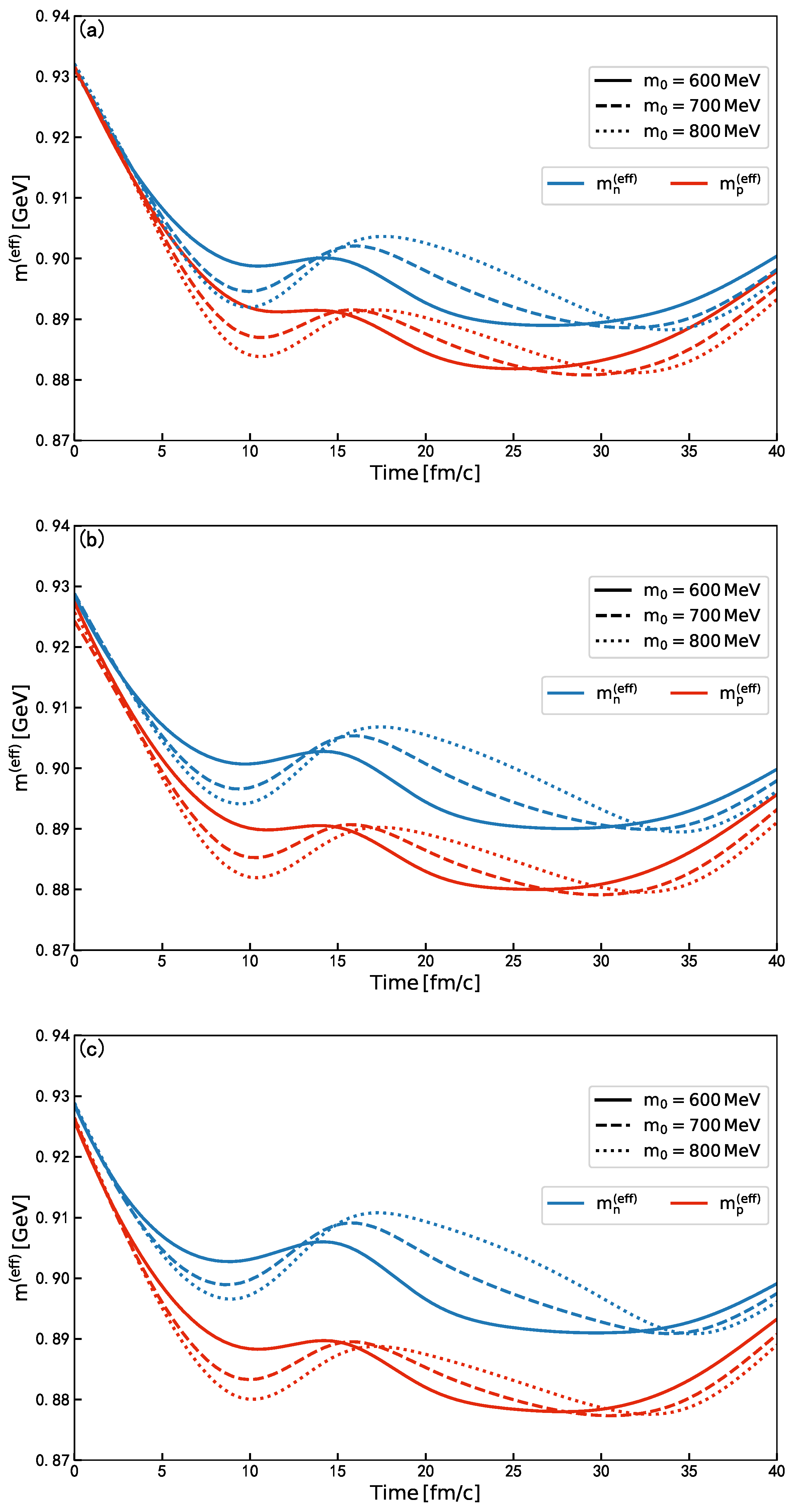

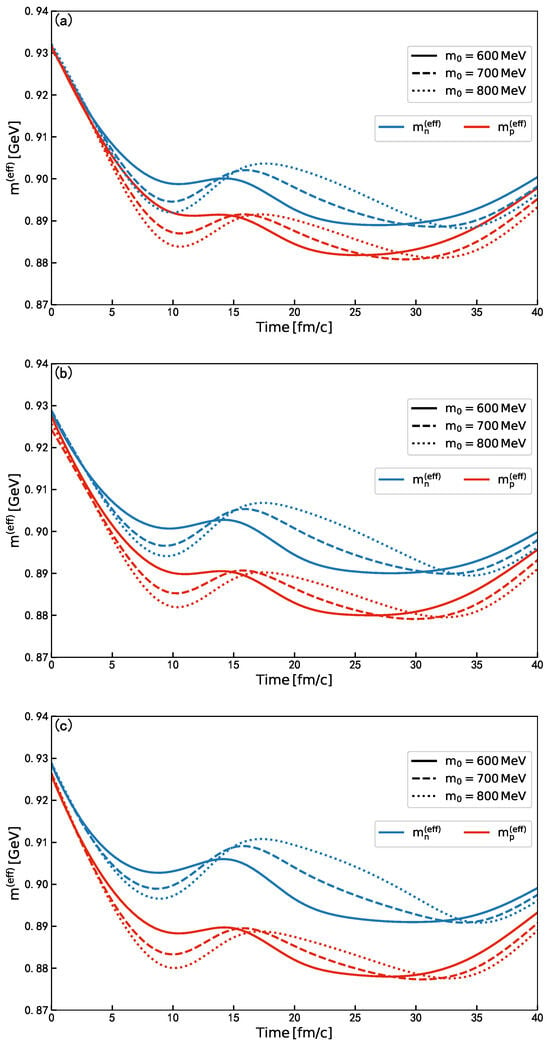

In Figure 2, we present the time evolution of the effective masses of protons and neutrons for and 800 MeV in the 108Sn + 112Sn, 112Sn + 124Sn, and 132Sn + 124Sn systems. Here, the effective mass is defined as the nucleon’s energy at zero momentum:

Figure 2 demonstrates that, within our model, the proton mass decreases more rapidly than the neutron mass across all three cases with varying values of the chiral-invariant mass. This is because the Sn + Sn systems are neutron-rich, which leads to a negative -meson mean-field value. It is also observed that the nucleon masses initially decrease and subsequently exhibit oscillatory behavior over time. This behavior originates from the time evolution of the baryon number densities shown in Figure 1 and reflects the distinctive in-medium nucleon mass properties of the parity doublet model [17]. For example, Figure 2 of Ref. [17] shows that the in-medium nucleon mass decreases up to approximately 1.2 times the saturation density and subsequently increases. This behavior is discussed in detail around Equation (14) of Ref. [17].

Figure 2.

(a) Time evolution of effective mass of proton and neutron for MeV in the 108Sn + 112Sn systems. (b) The same for MeV in the 112Sn + 124Sn systems. (c) The same for MeV in the 132Sn + 124Sn systems.

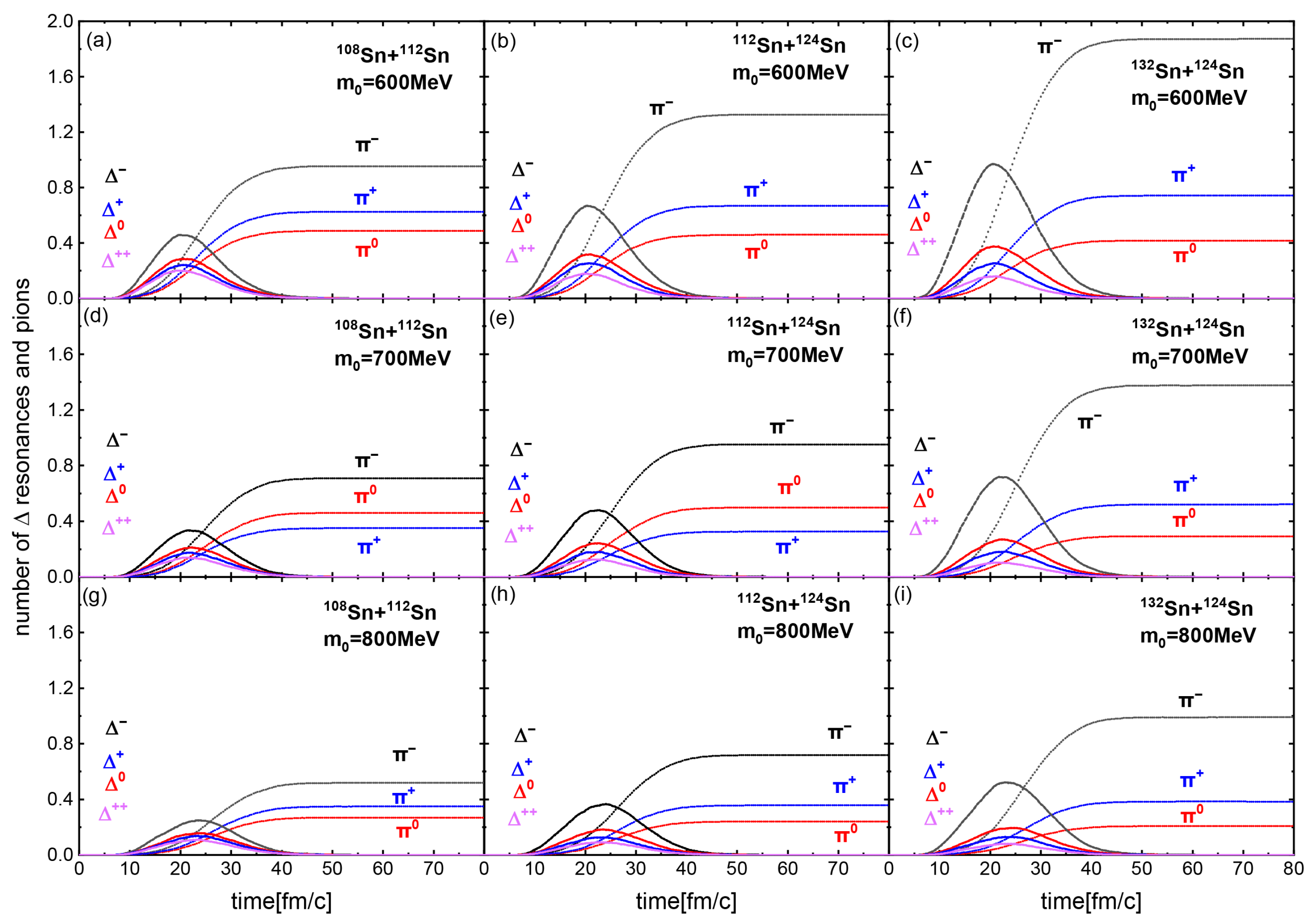

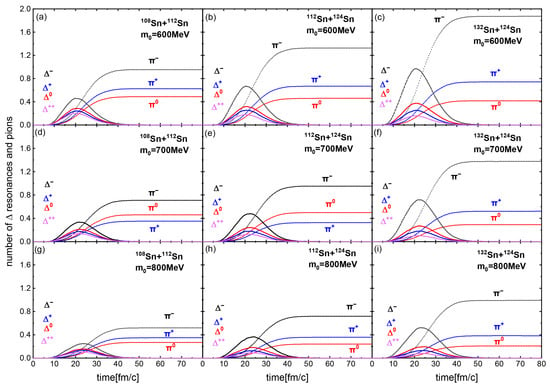

In Figure 3, we show the time evolution of the number of produced resonances and pions for and 800 MeV in the 108Sn + 112Sn, 112Sn + 124Sn, and 132Sn + 124Sn systems. In each system, we observe that the number of produced particles decreases as increases. From Figure 1 and Figure 3, intuitively, one expects more baryons are produced with a higher central density, but this is not the case in our study. As the ratio of the system increases, more mesons are produced. This is because a higher neutron-to-proton ratio enhances the probability of production of baryons through inelastic scatterings such as , which predominantly decay into .

Figure 3.

The number of resonances and pions as a function of time for and 800 MeV in 108Sn + 112Sn,112Sn + 124Sn, and 132Sn + 124Sn systems.

In Table 2, we list the pion yields and the charged pion yield ratios for 132Sn + 124Sn, 112Sn + 124Sn, and 108Sn + 112Sn compared with the SπRIT data [26].

Table 2.

Pion multiplicities and charged pion single-yield ratios SR() of Sn + Sn collisions for MeV. The experimental data are from the SπRIT Experiment [26]. The values in parentheses denote the corresponding statistical uncertainties (error bars).

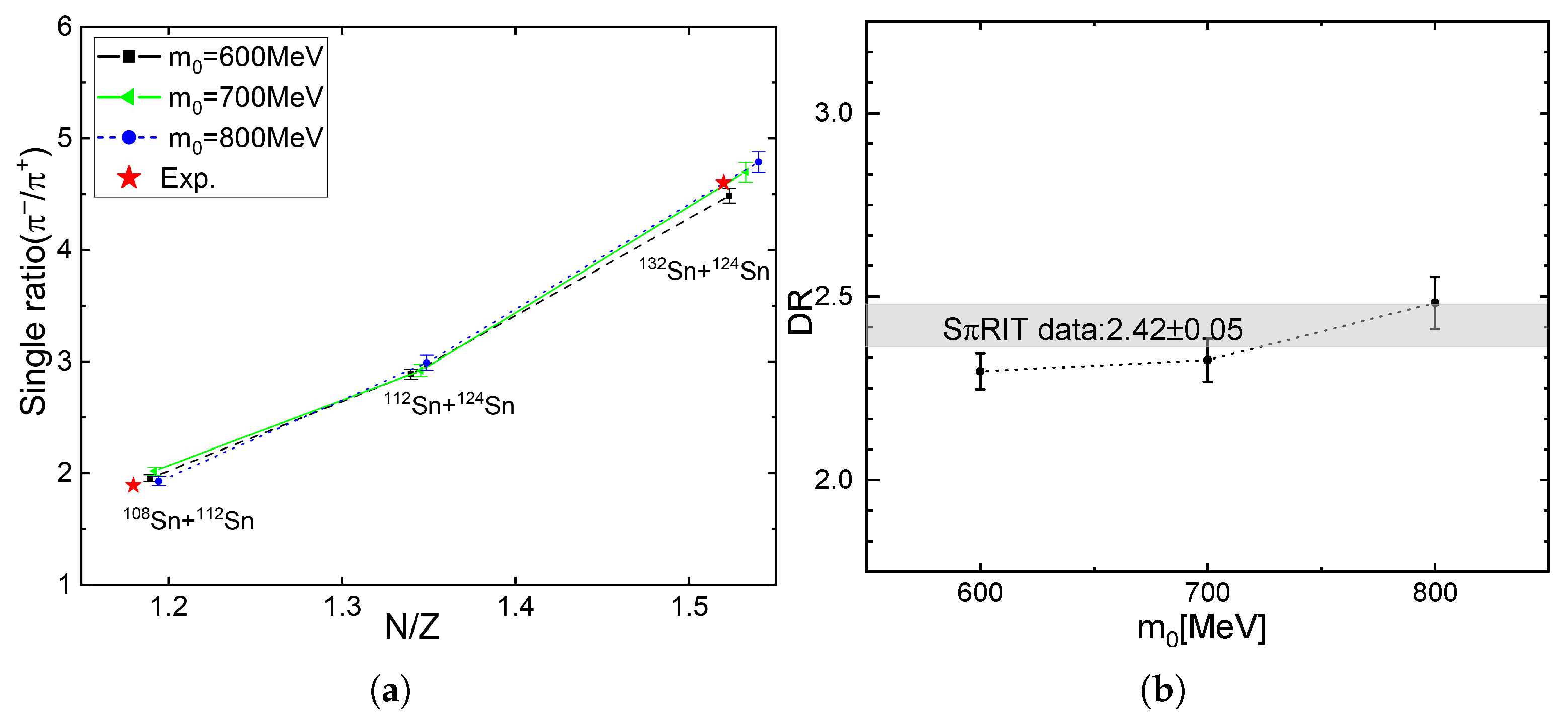

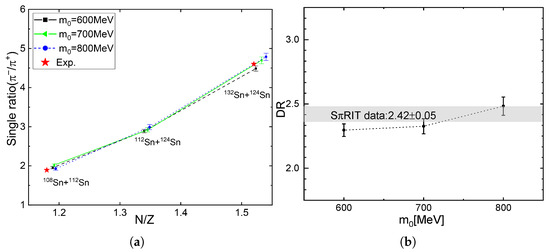

In Figure 4, the charged pion yield ratios as a function of N/Z, as well as the double-pion-yield ratio (DR) defined by []/[] for three values of , are displayed.

Figure 4.

(a) Charged pion single ratios as a function of for 132Sn + 124Sn, 112Sn + 124Sn, and 108Sn + 112Sn for three cases ( MeV). (b) The double-pion-yield ratio (DR) evaluated for three values of . Experimental data are taken from Ref. [26] and marked as a gray box. In the figure, symbols are slightly shifted for better visibility.

From Table 2 and Figure 4, we can see that the charged pion yield ratio for 132Sn + 124Sn lies within the error bars for three values of , while for 108Sn + 112Sn, the result with MeV falls outside the error bars. Similarly, for the DRs, the results with MeV fall slightly outside the error bars.

However, as in Table 2, although the multiplicity of the charged pion with MeV is closest to the experimental value, none of the three cases reproduce the experimental multiplicity. This can be improved by changing the parameters in the in-medium cross-section in Equation (8). Qualitatively, the yield ratio increases with decreasing pion multiplicity as expected, and the only exception of for Sn108 + Sn112 is likely due to statistics. On the other hand, the experimental data with a smaller pion multiplicity but a small yield ratio could be reproduced with but different isovector potentials, i.e., different and .

From Table 3, one can observe that varying the parameter C leads to noticeable changes in the pion multiplicities and the charged pion single-yield ratios for both reaction systems, 132Sn + 124Sn and 108Sn + 112Sn. The results show that when , the predicted values for the 108Sn + 112Sn system are closer to the experimental data, whereas for , the calculations for the neutron-rich 132Sn + 124Sn system exhibit a better agreement with experiment.

Table 3.

Pion multiplicities and charged pion single-yield ratios SR() of two Sn + Sn collisions for MeV and C = 3.0, 3.2.

4. Summary

Using the extended parity doublet model [15] implemented in the DJBUU code, we studied pion production in the 108Sn + 112Sn, 112Sn + 124Sn, and 132Sn + 124Sn systems at a beam energy of A MeV with an impact parameter of 3 fm. We then compared our results with the SπRIT data [26]. The isospin-dependent in-medium cross-section [31] was employed in our calculations.

We used chiral-invariant mass values of 600, 700, and 800 MeV and found that the case with MeV best reproduces the experimental data [26], particularly the single- and double-pion-yield ratios. However, none of the three cases reproduces the experimental multiplicity, which may be improved by adjusting the parameters in the in-medium cross-section given in Equation (8). We also observed that a larger results in a higher maximum baryon density of nuclear matter produced during heavy-ion collisions, which is due to the reduction in the coupling constants and , as increases.

As summarized in the Introduction, previous studies on dense matter, finite nuclei, and neutron stars have constrained the value of to lie within the range . Therefore, the value of the chiral-invariant mass constrained by pion production in heavy-ion collisions is consistent with these earlier findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.K.; formal analysis, J.Z. and K.K.; investigation, J.Z. and K.K.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.K.; writing—review and editing, S.J. and J.X.; supervision, S.J. and J.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

J.Z. and J.X. received support from the National Key Research and Development Program of China under Grants No. 2023YFA1606701, the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 12375125, and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities. J.Z. also received support from the China Scholarship Council (CSC). The work of K.K. and Y.K. was supported in part by the Institute for Basic Science (IBS-I001-01, IBS-R031-D1). S.J. acknowledges the support of the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), [SAPIN-2024-00026].

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dae Ik Kim for all the helpful discussions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bernard, V.; Kaiser, N.; Meissner, U.G. Chiral dynamics in nucleons and nuclei. Int. J. Mod. Phys. E 1995, 4, 193–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, V. Introduction to chiral symmetry. arXiv 1995, arXiv:nucl-th/9512029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, S.; Schindler, M.R. Quantum chromodynamics and chiral symmetry. Lect. Notes Phys. 2012, 830, 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, J.W.; Rho, M.; Weise, W. Chiral symmetry and effective field theories for hadronic, nuclear and stellar matter. Phys. Rept. 2016, 621, 2–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeTar, C.E.; Kunihiro, T. Linear σ Model with Parity Doubling. Phys. Rev. D 1989, 39, 2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jido, D.; Oka, M.; Hosaka, A. Chiral symmetry of baryons. Prog. Theor. Phys. 2001, 106, 873–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatsuda, T.; Prakash, M. Parity Doubling of the Nucleon and First Order Chiral Transition in Dense Matter. Phys. Lett. B 1989, 224, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zschiesche, D.; Tolos, L.; Schaffner-Bielich, J.; Pisarski, R.D. Cold, dense nuclear matter in a SU(2) parity doublet model. Phys. Rev. C 2007, 75, 055202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dexheimer, V.; Schramm, S.; Zschiesche, D. Nuclear matter and neutron stars in a parity doublet model. Phys. Rev. C 2008, 77, 025803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, C.; Mishustin, I. Thermodynamics of dense hadronic matter in a parity doublet model. Phys. Rev. C 2010, 82, 035204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallas, S.; Giacosa, F.; Pagliara, G. Nuclear matter within a dilatation-invariant parity doublet model: The role of the tetraquark at nonzero density. Nucl. Phys. A 2011, 872, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinheimer, J.; Schramm, S.; Stocker, H. The hadronic SU(3) Parity Doublet Model for Dense Matter, its extension to quarks and the strange equation of state. Phys. Rev. C 2011, 84, 045208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paeng, W.G.; Lee, H.K.; Rho, M.; Sasaki, C. Interplay between ω-nucleon interaction and nucleon mass in dense baryonic matter. Phys. Rev. D 2013, 88, 105019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benic, S.; Mishustin, I.; Sasaki, C. Effective model for the QCD phase transitions at finite baryon density. Phys. Rev. D 2015, 91, 125034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motohiro, Y.; Kim, Y.; Harada, M. Asymmetric nuclear matter in a parity doublet model with hidden local symmetry. Phys. Rev. C 2015, 92, 025201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Steinheimer, J.; Schramm, S. Higher-order baryon number susceptibilities: Interplay between the chiral and the nuclear liquid-gas transitions. Phys. Rev. C 2017, 96, 025205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, Y.; Kim, Y.; Harada, M. Catalysis of partial chiral symmetry restoration by Δ matter. Phys. Rev. C 2018, 97, 065202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marczenko, M.; Sasaki, C. Net-baryon number fluctuations in the Hybrid Quark-Meson-Nucleon model at finite density. Phys. Rev. D 2018, 97, 036011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mun, M.H.; Shin, I.J.; Paeng, W.G.; Harada, M.; Kim, Y. Nuclear structure in parity doublet model. Eur. Phys. J. A 2023, 59, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, T.; Harada, M. Constraint to chiral invariant masses of nucleons from GW170817 in an extended parity doublet model. Phys. Rev. C 2019, 100, 025205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minamikawa, T.; Kojo, T.; Harada, M. Quark-hadron crossover equations of state for neutron stars: Constraining the chiral invariant mass in a parity doublet model. Phys. Rev. C 2021, 103, 045205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Jeon, S.; Kim, Y.M.; Kim, Y.; Lee, C.H. Extended parity doublet model with a new transport code. Phys. Rev. C 2020, 101, 064614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolter, H.; Colonna, M.; Cozma, D.; Danielewicz, P.; Ko, C.M.; Kumar, R.; Ono, A.; Tsang, M.B.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Transport model comparison studies of intermediate-energy heavy-ion collisions. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 2022, 125, 103962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wolter, H.; Colonna, M.; Cozma, M.D.; Danielewicz, P.; Ko, C.M.; Ono, A.; Tsang, M.B.; Zhang, Y.-X.; Cheng, H.; et al. Comparing pion production in transport simulations of heavy-ion collisions at 270A MeV under controlled conditions. Phys. Rev. C 2024, 109, 044609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, A.; Xu, J.; Colonna, M.; Danielewicz, P.; Ko, C.M.; Tsang, M.B.; Wang, Y.-J.; Wolter, H.; Zhang, Y.-X.; Chen, L.; et al. Comparison of heavy-ion transport simulations: Collision integral with pions and Δ resonances in a box. Phys. Rev. C 2019, 100, 044617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhang, G.; Estee, J.; Barney, J.; Cerizza, G.; Kaneko, M.; Lee, J.W.; Lynch, W.G.; Isobe, T.; Kurata-Nishimura, M.; Murakami, T.; et al. Symmetry energy investigation with pion production from Sn+Sn systems. Phys. Lett. B 2021, 813, 136016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Lee, C.H.; Kim, Y.; Jeon, S. Introduction to the DaeJeon Boltzmann-Uehling-Uhlenbeck (DJBUU) Project. Sae Mulli 2016, 66, 1563–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bando, M.; Kugo, T.; Yamawaki, K. Nonlinear Realization and Hidden Local Symmetries. Phys. Rept. 1988, 164, 217–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, M.; Yamawaki, K. Hidden local symmetry at loop: A New perspective of composite gauge boson and chiral phase transition. Phys. Rept. 2003, 381, 1–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Ko, C.M. Modifications of the pion-production threshold in the nuclear medium in heavy ion collisions and the nuclear symmetry energy. Phys. Rev. C 2015, 91, 014901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, Y.; Jeon, S.; Lee, C.H. Pion Productions with Isospin-Dependent In-Medium Cross Sections. Universe 2022, 8, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, H.J.; Schnell, A.; Röpke, G.; Lombardo, U. Nucleon-nucleon cross sections in nuclear matter. Phys. Rev. C 1997, 55, 3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persram, D.; Gale, C. Elliptic flow in intermediate energy heavy ion collisions and in-medium effects. Phys. Rev. C 2002, 65, 064611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.A.; Chen, L.W. Nucleon-nucleon cross sections in neutron-rich matter and isospin transport in heavy-ion reactions at intermediate energies. Phys. Rev. C 2005, 72, 064611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozma, M.D.; Tsang, M.B. In-medium Δ(1232) potential, pion production in heavy-ion collisions and the symmetry energy. Eur. Phys. J. A 2021, 57, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Greco, V.; Baran, V.; Colonna, M.; Toro, M.D. Asymmetric nuclear matter: The role of the isovector scalar channel. Phys. Rev. C 2002, 65, 045201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).