Microscopic Mechanism of Fracturing Fluid Flowback Regulated by Coal Bridge-Proppant Wettability Contrast

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. In Situ Wettability of Reservoir

2.1.1. Coal Sample Selection

2.1.2. In Situ Wettability Equipment and Methods

2.2. Mixed Wettability Gradient Modeling and Numerical Implementation

2.2.1. Governing Equation

2.2.2. Model Assumes That

- The porous medium consists of uniformly arranged circular particles with different surface wettability, ignoring the heterogeneity of particle size and geometry;

- The flow system is immiscible gas–liquid two-phase, without material exchange and chemical reaction between the two phases, corresponding to the displacement relationship between coalbed methane and fracturing fluid during fracturing fluid backflow;

- Fluid is an incompressible Newtonian fluid, and its flow follows the Navier–Stokes equations [38]. The phase field model satisfies the continuum assumption;

2.2.3. Wettability Modeling and Meshing

2.2.4. Model Boundary Setting

2.3. Model Verification

2.4. Numerical Simulation Experiment Design and Execution

3. Results and Analysis

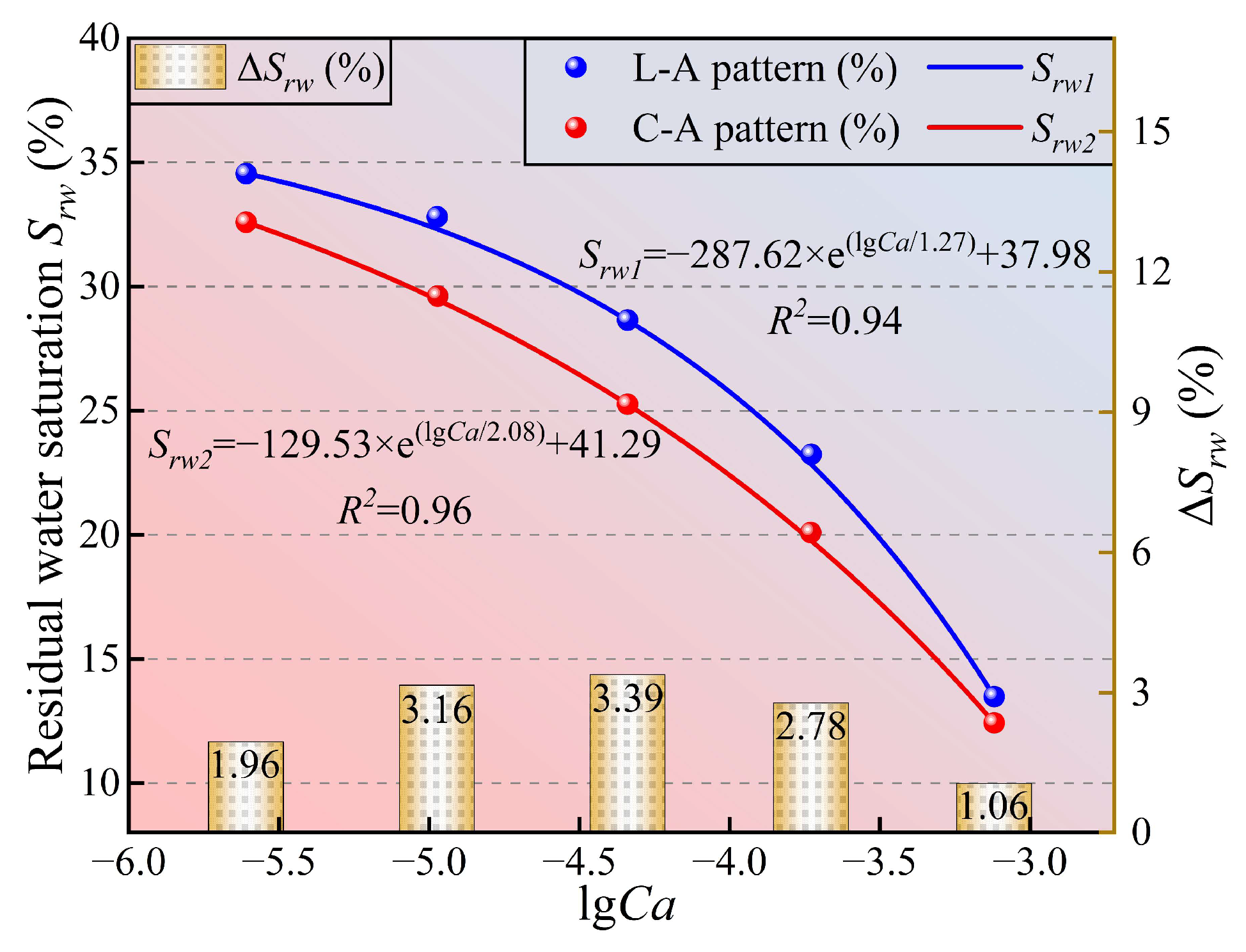

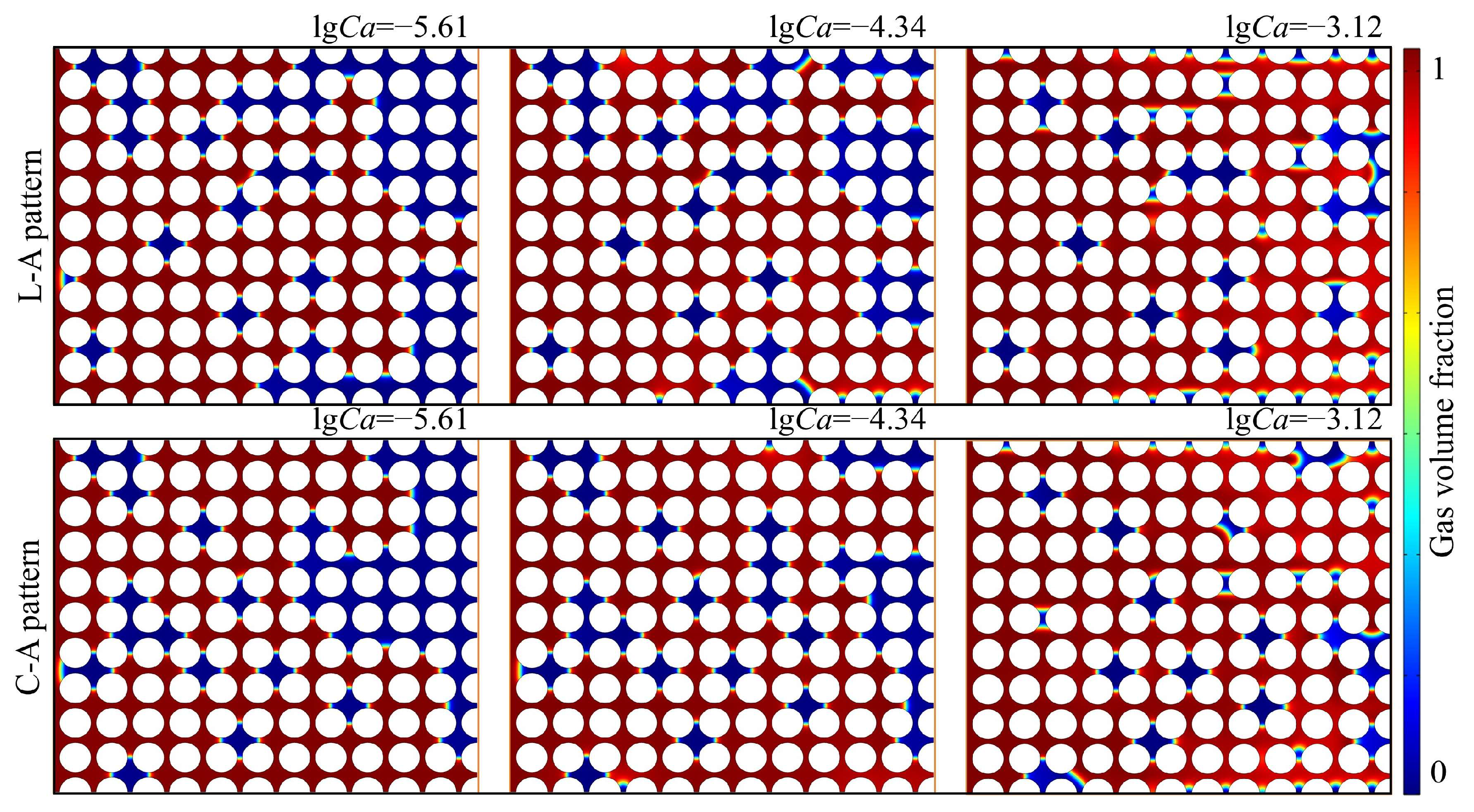

3.1. The Influencing Mechanism of Proppant Spatial Aggregation Patterns on Fracturing Fluid Flowback

3.1.1. The Influence Law of Coal Bridge-Hydrophilic Proppant on Displacement Path

3.1.2. Effect of Coal Bridge-Modified Proppant on Displacement Path

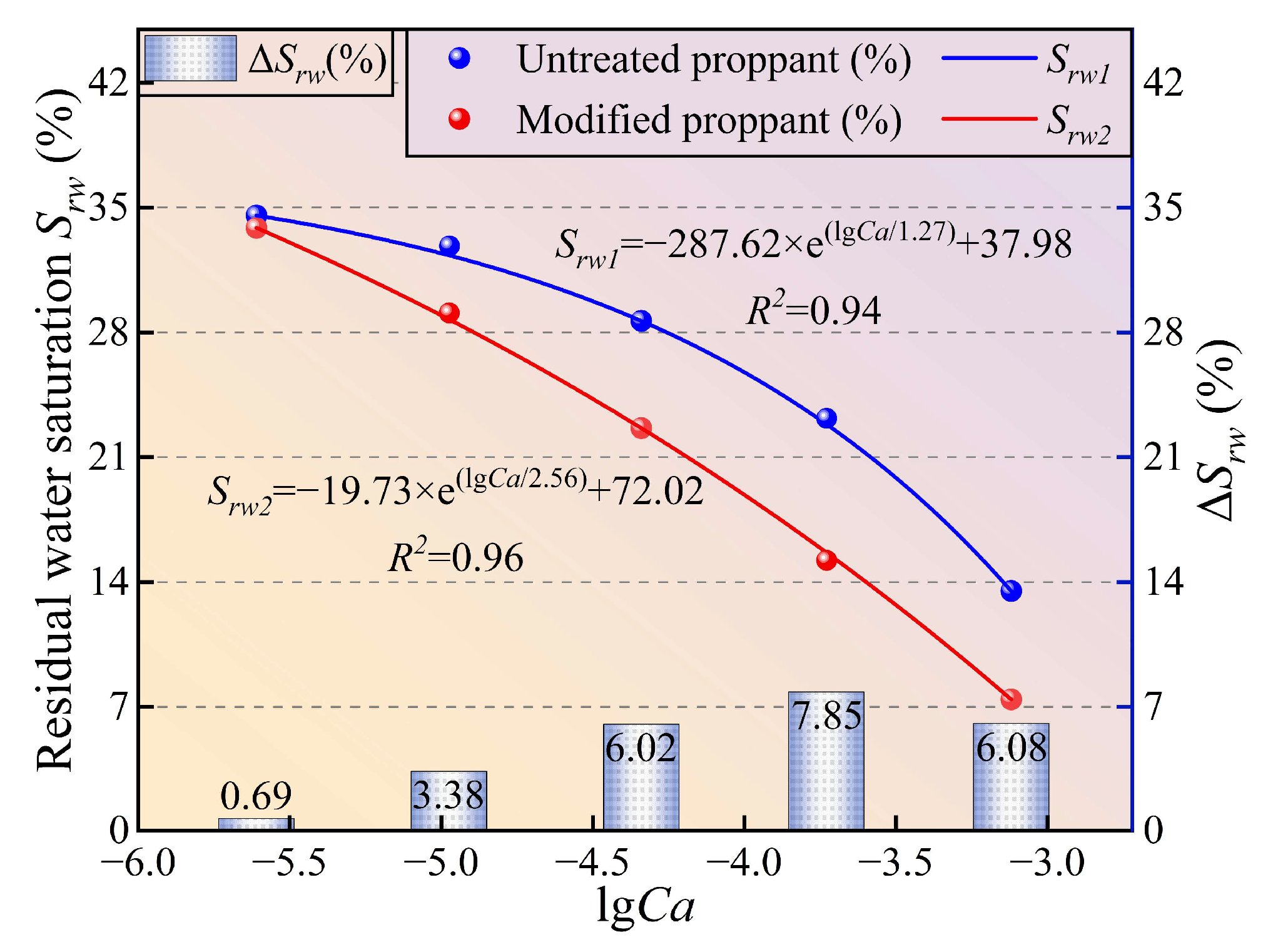

3.2. The Influence Mechanism of Proppant Modification on Fracturing Fluid Flowback

3.2.1. Distribution Characteristics of Residual Phase of Fracturing Fluid in Hydrophilic Proppant

3.2.2. Distribution Characteristics of Residual Phase of Fracturing Fluid in Modified Proppant

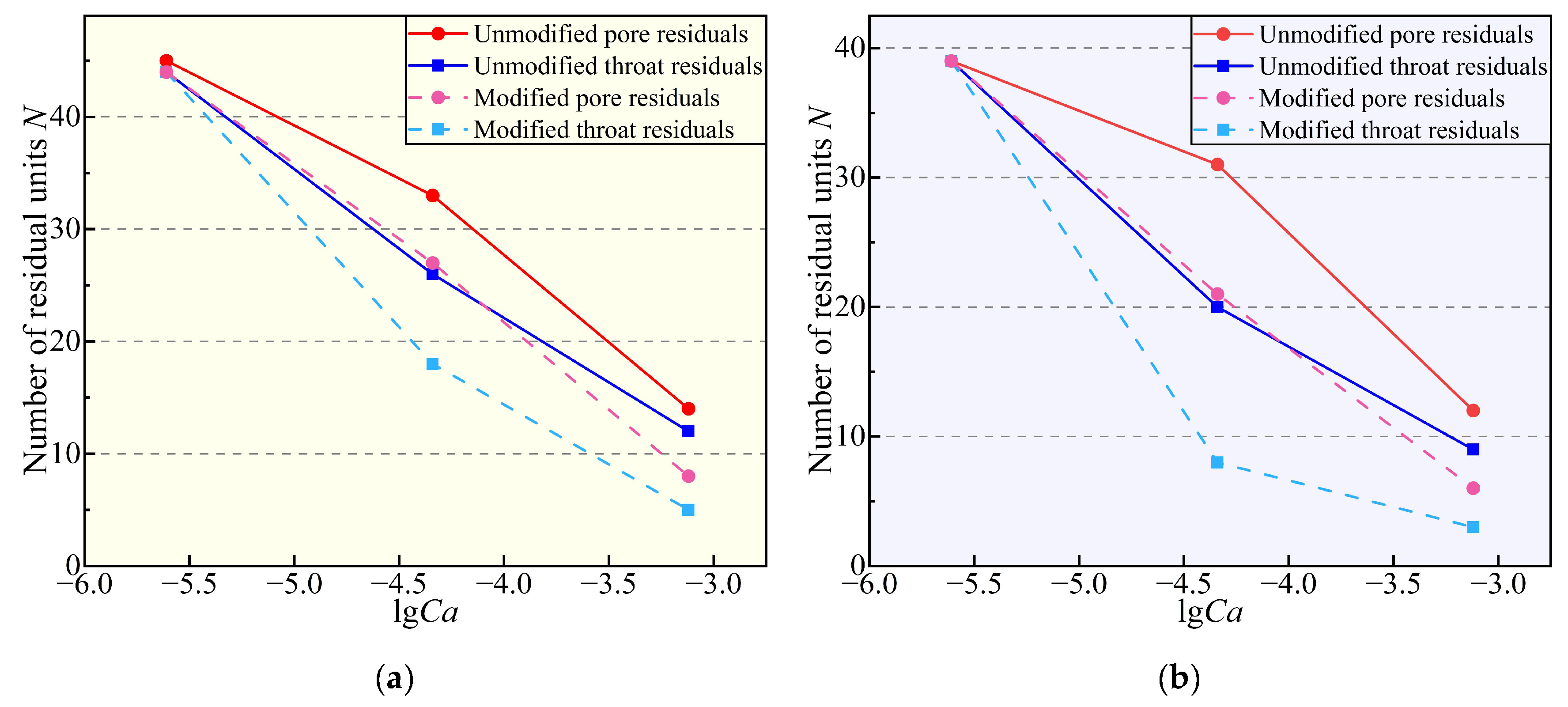

3.3. Cross-Scale Collaboration Mechanism

3.3.1. Local Distribution Characteristics of Pore-Throat Scale Residual Phase

3.3.2. The Influence of Capillary Number on the Local Distribution of Residual Phase

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The spatial distribution of the proppant determines the backflow path and retention strength. Lateral aggregation enhances capillary trapping, with the residual fluid saturation reaching up to 34.55%, while central aggregation optimizes the distribution of driving force in the symmetrical flow channels, reducing the residual fluid saturation by 5.4% and making the driving front more uniform.

- (2)

- The modification of proppant wetting properties reverses the direction of interfacial forces. Neutral modification drives the fracturing fluid to detach through interface repulsion, which can reduce the residual fluid saturation by up to 52.8%, significantly improving the backflow efficiency.

- (3)

- The capillary number controls the exponential decay law of residual fluid saturation. The combination of central aggregation and neutral modification achieves the lowest residual fluid saturation (5.87%) at lgCa = −3.12, and the number of residual clusters decreases by 66.7%.

- (4)

- Microscopic throat constraints and macroscopic symmetrical structures have a cross-scale synergistic effect. Geometric constraints of throat geometry amplify the weakening effect of neutral modification on capillary resistance, while the macroscopic symmetrical structure inhibits local capillary trapping. The coupling of these two factors promotes the reduction of the maximum radius of residual clusters to 164.6 μm.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qin, Y.; Moore, T.A.; Shen, J.; Yang, Z.; Shen, Y.; Wang, G. Resources and geology of coalbed methane in China: A review. Coal Geol. China 2017, 60, 777–812. [Google Scholar]

- Ramandi, H.L.; Mostaghimi, P.; Armstrong, R.T.; Saadatfar, M.; Pinczewski, W.V. Porosity and permeability characterization of coal: A micro-computed tomography study. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2016, 154, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zhang, A.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, A.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zeng, Q.; Niu, Y. Study on oil seepage mechanisms in lamellar shale by using the lattice Boltzmann method. Fuel 2023, 351, 128939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Cheng, Y.; Li, W.; Han, X.; Liu, C.; Su, H. 3D visualization of tectonic coal microstructure and quantitative characterization on topological connectivity of pore-fracture networks by Micro-CT. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 208, 109675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Dong, E.; Zhou, F.; Wang, Y.; Gou, X.; Bai, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, F. A new numerical model for simulation of flow on rough fracture. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 234, 212540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Lu, Y.; Ge, Z.; Cheng, L.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, W. Experimental study on crack propagation control and mechanism analysis of directional hydraulic fracturing. Fuel 2018, 218, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ding, Y.; Xue, F.; Wei, J.; Lin, H.; Dai, H. Confinement pressure effect and influence mechanism of water injection-induced slip of shale fracture. Eng. Geol. 2025, 352, 108061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lv, D.; Zhang, J.J.; Wang, F.; Yin, D.; Yu, H. Dual-scale insights of two-phase flow in inter-cleats based on microfluidics: Interface jumps and energy dissipation. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2025, 35, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lv, D.; Zhang, J.J.; Zhang, X.; Yu, H.; Li, X.; Fan, K. Microfluidic diagnostics: Evolution of gas critical paths based on dynamic alterations of cleats wettability. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 515, 163662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Xia, B.; Lu, Y.; Song, R.; Wang, L. Pore-scale analysis and modeling of heterogeneous wettability in immiscible two-phase flow inside natural porous media. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2025, 247, 213676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geistlinger, H.; Zulfiqar, B. The impact of wettability and surface roughness on fluid displacement and capillary trapping in 2-D and 3-D porous media: 1. Wettability-controlled phase transition of trapping efficiency in glass beads packs. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56, e2019WR026826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Zhu, Q.; Chen, Z.; Li, J.; Feng, D.; Wang, M.; Guo, S.; Guo, Y. Microscopic gas displacement efficiency of enhanced gas recovery in carbonate gas reservoirs with edge and bottom water. Nat. Gas Ind. B 2023, 10, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Mao, R. Impact of temperature and pressure on the characteristics of two-phase flow in coal. Fuel 2019, 253, 1325–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, W.; Liu, J. Effect of wettability heterogeneity on water-gas two-phase displacement behavior in a complex pore structure by phase-field model. Energies 2022, 15, 7658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Ma, Y.; Li, H.; Guo, B. Experimental and numerical investigations of water-oil two-phase flow in fractures with proppants of different wetting properties. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 214, 110361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, K.; He, W.; Wang, M. Effect of surface wettability of ceramic proppant on oil flow performance in hydraulic fractures. Energy Sci. Eng. 2019, 7, 504–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Ma, L.; Li, Z.; Huang, F.; Huang, C.; Yuan, H.; Tang, Z.; Guo, J. A novel hydraulic fracturing method based on the coupled CFD-DEM numerical simulation study. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Lin, C.; Zhao, J.; Lin, R.; Wu, J.; Wu, J.; Hu, Z. Numerical simulation of coated proppant transport and placement in hydraulic fractures based on CFD-DEM. Pet. Sci. Technol. 2024, 42, 3334–3354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Su, X.; Feng, Y.; Wang, H.; Song, J. Experimental study of gas-water two-phase flow patterns in fracture: Implication for enhancing coalbed methane production. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 207, 109168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Yan, H.; Huang, R.; Liu, L.; Li, Q. Phase-field lattice Boltzmann method for the simulation of gas-liquid mass transfer. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2022, 253, 117539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, L.; Brosch, S.; Gaehr, M.; Linkhorst, J.; Wessling, M.; Nieken, U. Convective drying of porous media: Comparison of phase-field simulations with microfluidic experiments. Transp. Porous Media 2024, 151, 559–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, J.; Mohammed, M.Z.; Li, F.; Yan, Z.; Ding, Y.S. Seepage characteristics of mixed-wettability porous media on the phase-field model. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 30104–30112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, N.; Lucarini, S.; Ma, R.; Chen, A.; Cui, C. PF-PINNs: Physics-informed neural networks for solving coupled Allen-Cahn and Cahn-Hilliard phase field equations. J. Comput. Phys. 2025, 529, 113843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Xu, W.; Zhao, Z.; Yi, S.; Yang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, W.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, C.; et al. Geological characteristics and exploration breakthroughs of coal rock gas in Carboniferous Benxi Formation, Ordos Basin, NW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2024, 51, 262–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zhang, H.; Shi, Y.; Fu, X.; Hui, J.; Jing, X. Geological characteristics and exploration potential of the coal measure gas from Shan 2 of the Shanxi formation in the eastern Ordos Basin. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1142141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Shao, Y.; Gao, Z.; Li, J.; Sun, B.; Yang, M.; Zhou, J.; Yao, H.; Sun, F.; Shao, L. Coalbed Methane Enrichment Characteristics and Exploration Target Selection in the Zhuozishan Coalfield of the Western Ordos Basin, China. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 43531–43547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Li, Z.; Xue, Q.; Wang, S. Failure mechanism of rock-like specimens under uniaxial compression: Effects of hole-crack spatial relationship and crack number. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2025, 140, 105185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suramairy, R.; Rasol, A.A.A.; Norddin, M.; Hamoudi, M.R.; Khalid, A.W.; Hasan, D.A. Impact of reservoir organic acid and brine salinity on CO2-rock interfacial tension and wettability in carbonate rocks: Insights for geological CO2 storage. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 105983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lv, D.; Yin, D.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Fan, K. Gas recovery and flowback in trans-coal-limestone fracture: An in-situ wettability microscale visualization insight. Gas Sci. Eng. 2025, 142, 205707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Deng, Z. Hydrodynamics of a droplet passing through a microfluidic T-junction. J. Fluid Mech. 2017, 819, 401–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Yang, X.; Wang, Z. Numerical simulations on the self-motion of droplets in hydrophobic microchannels driven by wettability gradient surfaces. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 119, 104961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggers, J.; Fontelos, M.A.; Josserand, C.; Zaleski, S. Drop dynamics after impact on a solid wall: Theory and simulations. Phys. Fluids 2010, 22, 062101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Xu, C.; Karniadakis, G.E. A fractional phase-field model for two-phase flows with tunable sharpness: Algorithms and simulations. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2016, 305, 376–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahn, J.W.; Hilliard, J.E. Free energy of a nonuniform system. I. Interfacial free energy. J. Chem. Phys. 1958, 28, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellenq, R.J.M.; Coasne, B.; Denoyel, R.O.; Coussy, O. Simple phenomenological model for phase transitions in confined geometry. 2. Capillary condensation/evaporation in cylindrical mesopores. Langmuir 2009, 25, 1393–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yang, H.; Zhu, X. Gas phase surface discharge plasma model for yeast inactivation in water. J. Food Eng. 2020, 286, 110117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.H.; Cao, Y.Y.; Gao, S.G. Surface modification of nano-silica with silane coupling agent. Key Eng. Mater. 2015, 636, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zhao, T.S. Lattice Boltzmann model for incompressible flows through porous media. Phys. Rev. E 2002, 66, 036304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Gao, M.; Zhang, R.; Peng, G.; Wang, W.; Li, A. Study on the mechanical properties and mechanical response of coal mining at 1000 m or deeper. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2019, 52, 1475–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.C.; Chen, S.J.; Ji, S.T.; Feng, F.; Aleksey, A.K.; Zaki, M.M. Imaging dynamic water invasion behavior in microfractures based on microfluidics. J. Cent. S. Univ. 2022, 29, 3986–4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zou, A.; Wang, L.; Cheng, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, C. Multiscale morphological and topological characterization of coal microstructure: Insights into the intrinsic structural difference between original and tectonic coals. Fuel 2022, 321, 124076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, J.; Yin, D.; Li, F.; Lu, J.; Zhu, P. Visualizing experimental investigation on gas–liquid replacements in a microcleat model using the reconstruction method. Deep Undergr. Sci. Eng. 2023, 2, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, J.; Ma, H.; Li, W. Numerical investigation on the influence of mesoscopic deformation on contact area and hydraulic aperture to fracture seepage. Deep Undergr. Sci. Eng. 2025, 2, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S. An efficient algorithm for incompressible N-phase flows. J. Comput. Phys. 2014, 276, 691–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Sun, K.; Zhang, G.; Yang, J. Diffuse-interface modeling and energy-stable numerical framework for the heat transfer-coupled two-phase fluids in contact with solids. J. Comput. Phys. 2025, 524, 113699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, T.; Jiang, L.; Wang, J. Numerical simulation of droplet movement on surface with gradient wetting property. Lubr. Eng. 2011, 36, 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, C.; Wang, Z.; He, H.; Han, Y.; Gu, J. Study on the structure and mechanical properties of dental barium glass particles surface modification with silane coupling reagent. Polym.-Plast. Technol. Eng. 2008, 47, 858–864. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, H.; Zhang, J.; Cao, Y.; Li, X.; Yu, H.; Li, F.; Lu, J. Water invasion and residual gas distribution in partially filled fractures via phase-field method. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 112032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Gu, X.; Chu, H.; Chen, S.; Ma, Y. Comprehensive roof cutting, pressure relief, and energy absorption anchorage control for mining roadways with extremely thick and hard roofs. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2026, 168, 107231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, N.; Wang, F.; Dong, F.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Zhu, T.; Wu, P.; Wang, X.; Cao, Y.; Liu, J.; et al. Microscopic Mechanism of Fracturing Fluid Flowback Regulated by Coal Bridge-Proppant Wettability Contrast. Symmetry 2025, 17, 2156. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122156

Wang N, Wang F, Dong F, Zhang J, Li X, Zhu T, Wu P, Wang X, Cao Y, Liu J, et al. Microscopic Mechanism of Fracturing Fluid Flowback Regulated by Coal Bridge-Proppant Wettability Contrast. Symmetry. 2025; 17(12):2156. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122156

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Naiguo, Feng Wang, Fengbao Dong, Jicheng Zhang, Xianfeng Li, Tiejing Zhu, Peng Wu, Xiucheng Wang, Youxun Cao, Jiaxuan Liu, and et al. 2025. "Microscopic Mechanism of Fracturing Fluid Flowback Regulated by Coal Bridge-Proppant Wettability Contrast" Symmetry 17, no. 12: 2156. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122156

APA StyleWang, N., Wang, F., Dong, F., Zhang, J., Li, X., Zhu, T., Wu, P., Wang, X., Cao, Y., Liu, J., Chu, H., & Xu, D. (2025). Microscopic Mechanism of Fracturing Fluid Flowback Regulated by Coal Bridge-Proppant Wettability Contrast. Symmetry, 17(12), 2156. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122156