Abstract

This article proposes a dynamic causal inference framework that integrates theoretical analysis, numerical simulation, and industrial data mining to address the root-cause tracing problem of time-delay effects in strip thickness and shape quality during hot rolling. First, we analyze the key process parameters, equipment states, and material characteristics influencing geometric quality and clarify their dynamic interaction mechanisms. Second, a delay-correlation matrix calculation method based on Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) and Mutual Information (MI) is developed to handle temporal misalignment in multi-source industrial signals and quantify the strength of delayed correlations. Furthermore, a transformer-based information gain approximation mechanism is designed to replace traditional explicit probability modeling and learn dynamic information-flow relationships among variables in a data-driven manner. Experimental verification on real production data demonstrates that the proposed framework can accurately identify time-delay causal pathways, providing an interpretable and engineering-feasible solution for quality control under complex operating conditions.

1. Introduction

Hot strip rolling is a critical technological process in steel strip production, comprising several interconnected stages such as reheating, rough rolling, high-pressure descaling, finish rolling, run-out table cooling, and coiling. As a major production method for high-quality steel plates in modern steel manufacturing, hot-rolled strip products are widely used in the automotive, construction, household appliance, and energy industries. With increasing demand for superior dimensional accuracy and surface quality in downstream applications, thickness control precision and strip flatness have become key indicators for evaluating the performance of hot rolling technology.

However, fluctuations in strip thickness and flatness defects (such as edge waves, center waves, and warpage) occur frequently in practical production. These issues not only reduce yield but also lead to deterioration of subsequent processing performance and compromise the end-use quality of the products. Therefore, systematically analyzing the key factors influencing thickness and flatness quality in the hot rolling process and establishing an effective root-cause tracing mechanism are of great significance for optimizing process parameters and improving overall product quality [1,2,3,4,5,6].

While contemporary studies on thickness and flatness control in hot strip rolling have achieved notable advancements in process parameter optimization, rolling mill dynamic compensation, and roll condition monitoring, prevailing approaches predominantly concentrate on isolated factor analysis or segmental process control, while systemic revelation of quality evolution mechanisms involving multi-stage synergy and parameter interdependencies is lacking [7,8].

The intricate causal relationships among process parameters (rolling force, tension profile, thermal gradient), machine conditions (roll thermo-mechanical performance, bearing dynamic characteristics), and material behaviors (strain resistance evolution, transformation kinetics) have not been fully elucidated, particularly under extreme operating conditions featuring elevated temperatures, severe deformation, and high-speed rolling. Consequently, the fundamental causes of quality deviations cannot be precisely determined via conventional correlation-based analytical approaches [9,10,11].

Such knowledge gaps prevent current methodologies from effectively reconstructing causality chains of quality defects during trans-process and multi-temporal scale variations in manufacturing systems, much less enabling causality-informed process optimization strategies. The development of causal analysis frameworks capable of deconvoluting nonlinear interactions among multivariate factors now constitutes a pivotal scientific challenge for overcoming quality control limitations in hot strip rolling processes.

The paradigm of causal inference and root-cause diagnostics [12] has gained significant traction in the excavation of associative information in process manufacturing data as well as in the establishing of variable causality to identify thickness/flatness-related information propagation pathways. A root-cause localization framework was developed in [13] to resolve the critical challenge of pinpointing underlying failure origins during fault incidents, encompassing both stationary and non-stationary fault scenarios. In [14], the authors constructed a research framework of “causal analysis–performance prediction–process optimization” that reconstructs causal networks from data to support decision-making and break the dual black-box dilemma in complex industrial processes. Recent advancements in root-cause analysis methodologies, including Granger causality, transfer entropy, and Bayesian networks, have enabled the characterization of causally related physical variables through causal topology structures extracted from process mechanics and domain knowledge. In complex systems requiring concurrent analysis of fault features and their interdependencies, transfer entropy and Granger causality have emerged as predominant causal inference technologies [15].

In [16], the Normalized Transfer Entropy (NTE) and Normalized Direct Transfer Entropy (NDTE) were established as core statistical metrics. This was accompanied by an enhanced statistical verification method to ascertain significance thresholds, facilitating robust causality determination. In [17], the authors established a data-driven correlated fault propagation pathway recognition model integrating KPCA for fault detection with an innovative transfer entropy algorithm for causal graph formulation, culminating in a kernel extreme learning machine-enabled fault path tracing methodology. In [18], a fault knowledge graph was constructed utilizing operational/maintenance logs, complemented by a lightweight graph neural network architecture for concurrent fault detection within graph-structured data. In [19], a gated regression neural network architecture was engineered to refine conditional Granger causality modeling, enabling precise diagnosis of quality-relevant fault origins and propagation route identification. The authors of [20] proposed a unified model that integrates Granger causality-based causal discovery with fault diagnosis within a single framework, enhancing the traceability of diagnostic results. Finally, [21] integrated physics-informed constraints with Graph Neural Networks (GNNs); by employing entropy-enhanced sampling and conformal learning, the authors were able to improve the accuracy of causal discovery and reduce spurious connections.

For robust reconstruction of weighted Granger causality networks in stationary multivariate linear dynamics, [22] devised a systematic methodology integrating sparse optimization with novel scalar correlation functions to achieve parsimonious model selection. An innovative fusion of PCA and Granger causality yielded a PCA-enhanced fault magnification algorithm for root-cause detection and propagation path tracing, with multivariate Granger analysis decoding causal relationships from algorithmic outputs [23].

In addition, some studies have conducted causal analysis on multi-factor fault diagnosis problems. In [24], the authors designed a modular structure called Sparse Causal Residual Neural Network (SCRNN), which uses a prediction target with layered sparse constraints and extracts multiple lagged linear and nonlinear causal relationships between variables to analyze the complete topology of fault propagation. On this basis, an R-value measurement is introduced to quantify the impact of each fault variable and accurately locate the root cause.

The majority of current research concentrates on static association analysis or univariate temporal causality reasoning, lacking comprehensive incorporation of the distinctive multi-lag coupling dynamics prevalent in industrial processes. This limitation becomes particularly pronounced in manufacturing systems such as hot strip rolling that exhibit substantial inter-stand interaction effects, where prevailing causal analysis methodologies demonstrate notable constraints. In multi-stand hot rolling operations, process perturbations originating from upstream stands generally exhibit delayed propagation characteristics, becoming detectable in downstream quality metrics only after several sampling intervals. These deterministic/stochastic time delays may induce conventional causality analysis approaches (e.g., Granger causality tests) to generate erroneous causal directionality determinations or attenuated causality magnitude estimations.

Consequently, this study investigates the hot strip rolling process, centering especially on thickness and flatness quality challenges, by using integrated theoretical analysis, computational modeling, and industrial data analytics to perform time-delayed root-cause diagnostics.

This paper’s primary contributions and innovations are as follows:

- Critical process parameters, mill conditions, and material properties affecting slab thickness and flatness are systematically identified and analyzed. The dynamic interactions and temporal dependencies among these factors are elucidated, providing a theoretical basis for subsequent causal inference.

- A correlation matrix computation method integrating Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) and Mutual Information (MI) is proposed to effectively address temporal misalignment in heterogeneous industrial time series. This method quantitatively characterizes cross-factor association strengths, enabling efficient preselection of candidate causal variable pairs.

- A transformer-based framework is developed that approximates time-varying transfer entropy using attention mechanisms and input masking techniques. Without requiring explicit probabilistic modeling, this framework directly extracts dynamic information transfer patterns among process variables from operational data, enabling interpretable data-driven causal reasoning.

Instead of simply combining existing techniques, this work introduces a novel causal-reasoning paradigm, providing a mathematically novel approach that goes beyond existing techniques such as DTW, MI, and transformers. The difference between information gain approximation from conventional causal inference approaches is that in contrast to conventional causal inference methods (e.g., Granger causality and transfer entropy), the model computes information gain implicitly by learning attention response differences under masked perturbations of each variable, which provides a mathematically interpretable surrogate of causal strength rather than a general statistical association.

The rest of this article is organized as follows: Section 2 systematically examines critical quality determinants, establishing the theoretical framework for later investigations; Section 3 develops DTW-MI-based correlation matrices, achieving reduced data dimensionality while deriving undirected association networks among process variables; Section 4 proposes a transformer-empowered information gain approximation approach to delineate causal information transfer mechanisms; Section 5 conducts comprehensive validation of the proposed framework with real-world industrial production datasets; finally, Section 6 concludes with the key findings and contributions of this research.

2. Problem Formulation

2.1. Quality Factors of Thick Plate Shape in Hot-Rolled Strip Steel

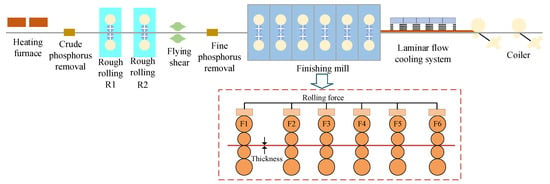

As shown in the Figure 1, hot rolling is the core process of rolling continuously-cast thick plate billets into thin plate coils. The process mainly includes key steps such as heating, roughing, finishing, and coiling. Among these, the control of plate thickness and shape, which is the most critical technology determining product dimensional accuracy, is highly concentrated in the precision rolling stage of the production line. When the intermediate billet enters the precision rolling unit composed of multiple rolling mills in series, the automatic thickness control system is used to quickly adjust the rolling force, while the automatic shape control system is used to dynamically optimize the roll convexity. This cooperative process guarantees the thickness accuracy and transverse shape of the plate and strip in real-time during high-speed rolling, laying the foundation for subsequent cold rolling and high value-added product production.

Figure 1.

Hot strip rolling process.

The thickness denotes the longitudinal uniformity of gauge distribution and has a critical influence on mechanical properties, while the flatness represents the transverse profile consistency, governing downstream manufacturability. The detection accuracy of the measurement system in the mills is typically within ±5 µm; contemporary mills demand thickness tolerance within m and flatness under 5I units, imposing stringent requirements on the multivariable-interdependent rolling dynamics. Because the process is strictly controlled during hot rolled strip production, the rolling mill environment is usually stable. Thus, we hide the influence of environmental variables on the measured process parameters. In our study, correlation analysis–based feature selection ensures that only variables with effective influence on targets are preserved, which prevents performance degradation caused by irrelevant environmental noise. The critical quality determinants investigated in this work are tabulated in Table A1 (thickness-related parameters) and Table A2 (comprehensive flatness influencing factors). Table A1 and Table A2 are provided in Appendix A.

The hot strip rolling process exhibits intricate causal propagation networks among thickness and flatness quality variables. Examination of thermomechanically coupled rolling principles demonstrates that these parameters constitute a tiered causality chain rather than operating independently. This is exemplified by roll thermal crown augmentation (root cause) inducing immediate roll gap geometry modification (mediating variable), which propagates into asymmetric rolling force distribution (second-order effect) and finally materializes as edge wave defects (quality manifestation). Such causality transmission possesses distinct temporality and directionality, with root-cause variables predominantly residing at the causation origin, then perturbing system energy profiles or mechanical equilibria to instigate downstream cascading effects. Capitalizing on these attributes, the present research integrates Bayesian networks with Granger causality analysis to extract pivotal causation pathways from multivariate process parameters; backward tracking of conditional dependencies facilitates discrimination of superficial artifacts, thereby accurately localizing thermal crown deviations as the fundamental fault source.

The multidimensional time series data related to the shape and quality of thick plates during the hot rolling process of strip steel in this article are as follows:

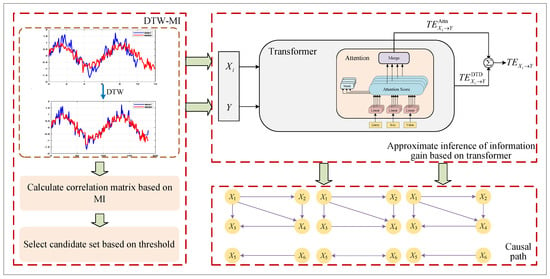

2.2. Solution Framework

As shown in Figure 2, the algorithm proposed in this paper achieves causal tracing of thickness and shape in hot rolling through multi-stage fusion. First, a theoretical causal network is constructed based on the process mechanism to clarify the key influencing factors. Furthermore, a delay correlation matrix calculation method combining DTW and mutual information is proposed to solve the temporal misalignment of industrial data and quantify the correlation strength. The core adopts a transformer architecture to learn the dynamic information flow relationship between variables, approximates the information gain through the attention mechanism, and replaces traditional probability modeling to identify delay causal paths.

Figure 2.

Algorithm framework.

3. Correlation Matrix Calculation Based on DTW-MI

In this study, mutual information is employed for feature screening to quantify the relevance between process variables and quality indicators. Unlike linear correlation metrics, mutual information is grounded in information theory and measures nonlinear and asymmetric dependencies. This enables more comprehensive identification of latent interactions that are difficult for traditional correlation-based analysis to capture.

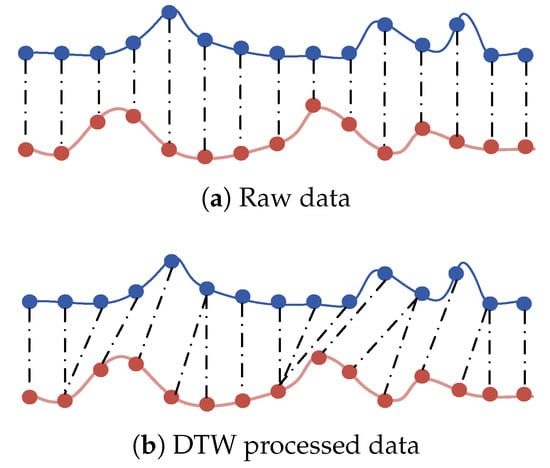

3.1. Data Alignment Based on DTW

During hot strip rolling operations, real-time measurements of thickness and flatness quality indicators, including crown and levelness, constitute multivariate temporal sequences. Owing to process fluctuations such as roll thermal dilation and feedstock hardness variations coupled with heterogeneous sensor sampling rates, identical manufacturing events such as rolling force transients manifest nonlinear temporal lags and localized rate discrepancies in multi-sensor responses. Traditional Euclidean distance metrics would yield erroneous similarity assessments caused by temporal misregistration; therefore, this study employs Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) to establish flexible time-warping trajectories. By permitting nonlinear temporal alignment through sequence stretching/compression, we achieve optimal morphological congruence between temporal sequences.

Figure 3 shows the comparison of raw data and DTW processed data. Two raw time series have possibly different lengths measured by sensors

where denotes the k-th sampling point of sequence with total length and similarly represents the sampling value of with total length . The objective of DTW is to find an alignment path that minimizes the time-series matching distance between two sequences under a certain cost function. Specifically, it seeks a path that pairs points from with those from to achieve nonlinear temporal alignment:

where is a distance metric function, usually using Euclidean distance.

Figure 3.

Comparison of data.

For optimal path computation efficiency, a cumulative distance matrix is constructed, with each element denoting the minimal warping cost along the path from to . The recurrence relation follows

The initial condition is , with other boundary conditions filled according to task requirements (e.g., set to infinity to constrain the path direction). To prevent excessive warping causing unrealistic matching, temporal window constraints (e.g., Sakoe–Chiba band or Itakura parallelogram) are usually introduced to limit the maximum deviation range of alignment paths from the diagonal. For example, the Sakoe–Chiba window is defined as

where r is the preset window radius. The data after the above DTW transformation are

For causal discovery in multivariate temporal sequences, we develop a novel inference framework integrating Mutual Information (MI)-based feature screening with Time-Varying Transfer Entropy (TVTE) detection. This methodology operates in two stages: (1) MI-based nonlinear dependency quantification for candidate pair preselection, effectively constraining the causal search space, and (2) TVTE-enabled dynamic causality orientation detection among preselected pairs, ultimately generating directed causal networks.

3.2. Calculate the Correlation Matrix Based on MI

For efficient causal inference with a constrained search space, we initially establish a cross-variable correlation matrix to preselect candidate variable pairs exhibiting potential causal links. Mutual Information (MI), as a nonparametric measure originating from information theory, is used to approximate the information gain between factors in causal networks, which is the theoretical basis for quantitative evaluation of cross factor correlation strength. MI quantifies the shared information content between paired random variables. The MI between and in (6) is formally defined by

where denotes the joint Probability Density Function (PDF), with and representing the corresponding marginal PDFs. The magnitude of MI directly reflects the degree of statistical dependence, where higher values signify stronger variable interdependencies. For statistically independent and , the MI metric yields . In practical time series analysis, the joint distribution between variables is difficult to model accurately; thus, traditional mutual information calculation methods based on histograms or kernel density estimation often suffer from the curse of dimensionality and insufficient samples in high-dimensional spaces. Therefore, this paper introduces a k-nearest neighbor based mutual information estimation method for nonparametric correlation modeling of multivariate time series.

The Kraskov mutual information estimation method estimates nearest-neighbor distances between point pairs in the joint space, then derives point density distributions in marginal spaces, and finally computes the mutual information quantity. This method is suitable for continuous variables, with strong nonparametric properties and high estimation accuracy, particularly for time series scenarios with limited samples.

Given two consecutive random variables and , the expression for Kraskov mutual information estimation is

where is the Digamma function, N is the number of samples, k is the nearest neighbor parameter, and and respectively represent the number of neighbors contained in the edge space, with the joint distance as the radius.

This article estimates the mutual information between variables pairwise and generates a symmetric mutual information matrix ,

Afterwards, a threshold of ℵ is set to filter the results, retaining only variable pairs with mutual information values greater than the threshold to form a candidate causal pair set

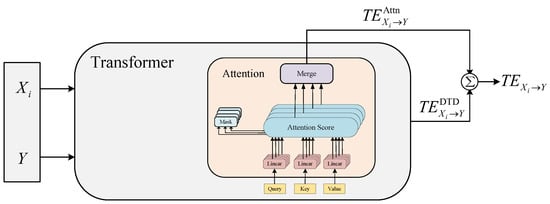

4. Transformer-Based Information Gain Approximation Reasoning

Traditional probabilistic causal modeling approaches such as Bayesian networks or Gaussian processes face inherent limitations when handling high-dimensional time-varying industrial data with complex dynamic interactions. In contrast, the proposed causal inference framework is grounded in information-theoretic causality, which emphasizes directed and lag-dependent information flow rather than symmetric correlation relationships. The transformer-based structure enables direct learning of dynamic dependencies from data without explicitly constructing joint probability density models or performing likelihood calculations. Its attention mechanism not only captures temporal dependencies but also reveals the relative information contribution of each variable and its historical time slices to the prediction target. Therefore, the learned attention weights provide interpretable visual evidence of dynamic causal relationships among process variables.

4.1. Time-Varying Transfer Entropy

Although mutual information can measure correlations between variables, its symmetry limits its application in causal direction identification. Therefore, this paper introduces the Time-Varying Transfer Entropy (TVTE), which estimates information flow between variables across different time intervals using a sliding window technique, thereby characterizing the dynamic evolution of causal relationships.

Transfer entropy is an asymmetric information measure based on conditional probability, defined as

where are historical state vectors of , respectively, with being the history orders. To capture the dynamic evolution of causal relationships, this study employs a sliding window mechanism to partition the time series into sub-intervals, computing the transfer entropy independently for each window, defined as follows:

where W is the window length and w denotes the window index. For each candidate variable pair , bidirectional transfer entropy is computed within each window:

and we define the causal strength difference as

If , then a causal direction is considered to exist in the current window. By counting the occurrence frequency of causal directions across all windows for each variable pair, the directional prevalence ratio is obtained:

where denotes the cardinality of set . Let be the threshold; if , then a stable causal relationship is considered to exist.

Explicit probability distribution estimation using Equation (11) requires computing the high-dimensional joint probability and conditional probability ; however, sliding window methods struggle to adapt to rapidly-changing dynamic systems.

Therefore, this paper introduces a transformer to directly learn dynamic dependencies between variables without explicit probability computation. Traditional methods typically use Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) for conditional probability estimation; however KDE suffers from the curse of dimensionality in high-dimensional state spaces, causing large estimation bias and high computational cost.

Thus, this paper proposes a transformer-based deep model to replace traditional explicit probability modeling, directly learning dynamic information flow relationships between variables from the data.

4.2. End-to-End Joint Training

The time-varying transfer entropy measures the additional contribution of ’s history to ’s future information given ’s own history. The estimation of these conditional probabilities is highly challenging.

Instead of manually computing TVTE, we train a transformer to predict target variable and infer the contribution of variable x to the prediction via information gain, thereby obtaining the approximate TVTE. In short, improved prediction capability ≈ enhanced information flow ≈ increased TVTE.

For any target variable , this framework constructs a transformer-based prediction model

trained using a regular supervised learning objective function

In our proposed transformer-based causal modeling framework, the attention mechanism not only learns temporal dependency features but also reflects the “information contribution degree” of input variables to the target variable. Specifically, when inputs consist of multiple time series variables, the attention weights in the transformer can be interpreted as the model’s reliance on different variables and their temporal slices, providing visual evidence for causal relationships.

The attention layer in the transformer calculates attention weights for all input tokens

where Q(Query), K(Key), and V(Value) are representations obtained from the input sequence through different linear mappings, is the dimension of the key used for scaling to avoid gradient explosion, and softmax is used to normalize attention scores into a probability distribution. The weight matrix (or cross-variable dimension) output by each attention head represents the current token’s level of attention to all input tokens. By aggregating these weights, we can calculate the attention contribution of a target location (such as the predicted ) to each input variable at each time step.

We aggregate the attention weights into variable dimensions (e.g., sum by time):

where a larger indicates that the transformer relies more on for prediction, suggesting a potential causal influence to some extent.

4.3. Information Gain Approximation Reasoning

To evaluate the marginal contribution of each input variable to target variable prediction, this framework introduces an input masking mechanism. This mechanism constructs masked input models by artificially “blocking” or “perturbing” partial input variables to observe changes in model prediction performance. Specifically, we replace a variable in the original input sequence with fixed values (e.g., zeros, mean, noise, or learned tokens) to create input samples lacking that variable’s information. We construct the control model

Thus, the approximate Soft Transfer Entropy Index (Soft TVTE) is defined as

where quantifies the influence by directly comparing prediction differences, representing the Direct Transfer Difference (DTD), represents the weighted sum based on attention responses, and denotes the attention allocated to input variable by the h-th head in the d-th layer, reflecting ’s contribution to predicting Y, with layer weights , .

By computing across all variable pairs, a time-varying causal graph can be constructed:

where represents the causal graph adjacency matrix at time t, with the -th element reflecting the information transfer intensity from to . Note that this is a directed weighted graph, and as such its structure may vary across time t to capture dynamic evolution of system causality. Figure 4 shows the inference of transformer-based information gain.

Figure 4.

Approximate inference of transformer-based information gain.

5. Experiment

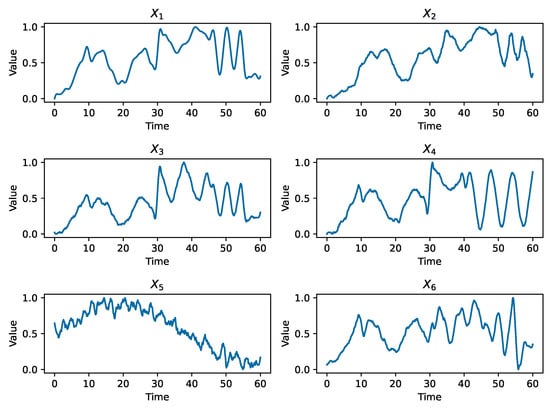

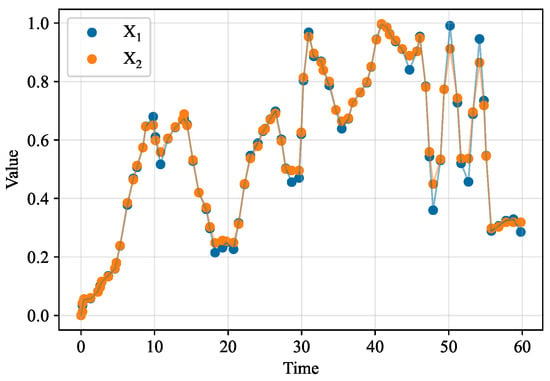

Process data were collected in real-time through a multi-source sensor network deployed at key process nodes in a 2250 mm hot strip mill of a steel plant. The raw data were first normalized as shown in Figure 5, where – represent roll condition, rolling force distribution, rolling force, tension, incoming strip crown, and incoming thickness/hardness variation, respectively.

Figure 5.

Normalized data.

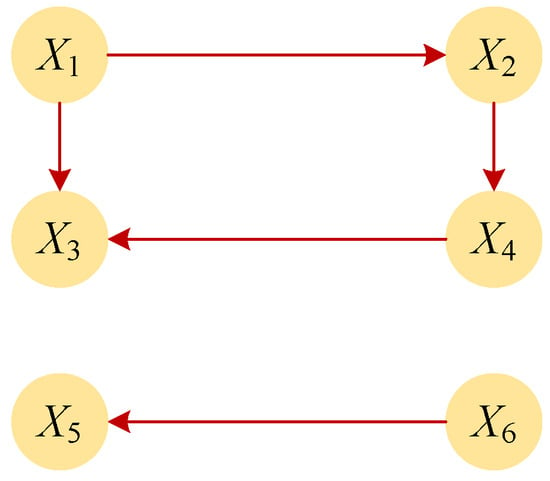

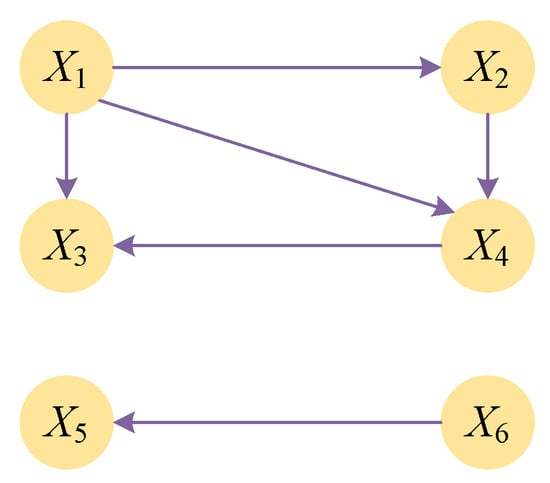

Based on field experience, the causal relationships between are shown in Figure 6, with the actual causal paths being , , and . The production significance is as follows: abnormal roll condition affects rolling force distribution and tension, leading to abnormal rolling force, while incoming thickness/hardness variation causes abnormal strip crown. Ultimately, abnormal rolling force and incoming crown jointly cause thickness and shape defects.

Figure 6.

Actual causal relationship diagram.

5.1. Calculation of Correlation Matrix Calculation Based on DTW-MI

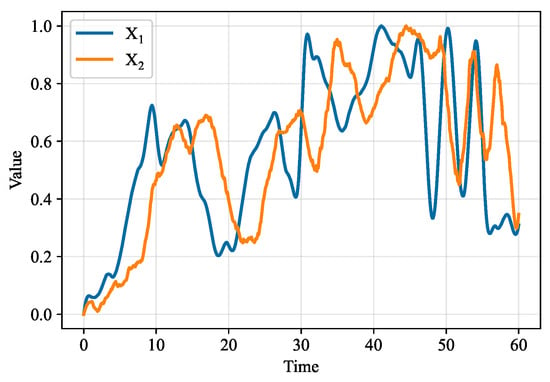

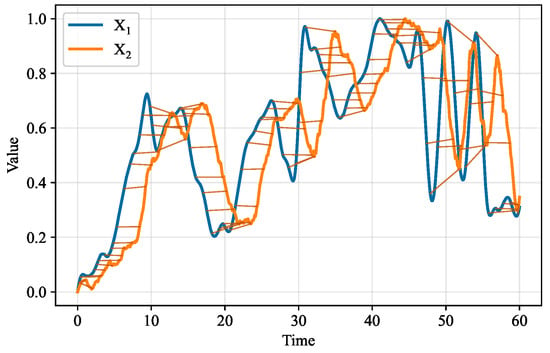

Taking – as an example, we take the DTW time window as 50 time steps and the mutual information threshold as 0.05. The processing of DTW is shown in Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9.

Figure 7.

Raw data.

Figure 8.

DTW data alignment.

Figure 9.

Data processed by DTW.

From the data in Figure 7, it can be seen that and have a causal relationship, where changes after with a certain delay. Comparing Table 1 and Table 2, the correlation coefficient between and in Table 2 is significantly higher than in Table 1, showing that DTW processing can enhance truly causal variable pairs for better causal inference. After DTW processing, variable pairs , , , , , and were selected for information gain approximation.

Table 1.

Mutual information value table of raw data.

Table 2.

Mutual information value table after DTW processing.

5.2. Causal Path Inference

Each sample consists of observation sequences from the past time steps, with the model task being to predict the target variable Y at the next time step. A lightweight transformer model was built with two encoder layers, four attention heads, a hidden dimension of 64, learning rate 0.01, and MSE as the training loss.The total data volume used in this work comprised 200,000+ samples. The dataset was partitioned into 70% training, 15% validation, and 15% testing. The training process was monitored using early stopping criteria, where training was halted if the validation loss did not improve for ten consecutive epochs. After training, information gain was calculated for each input variable according to (21). Additionally, conventional Granger causality analysis and TVTE causality analysis were selected for comparison.

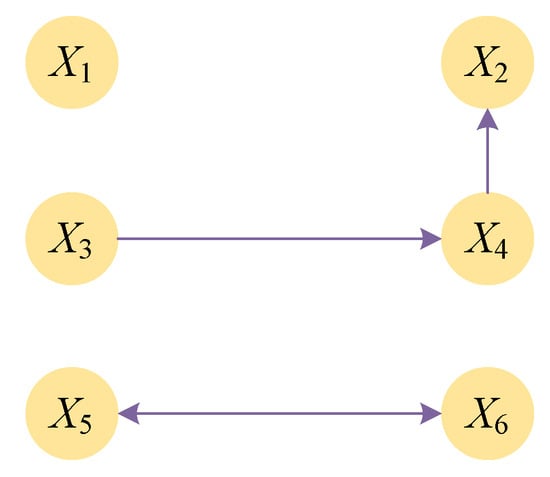

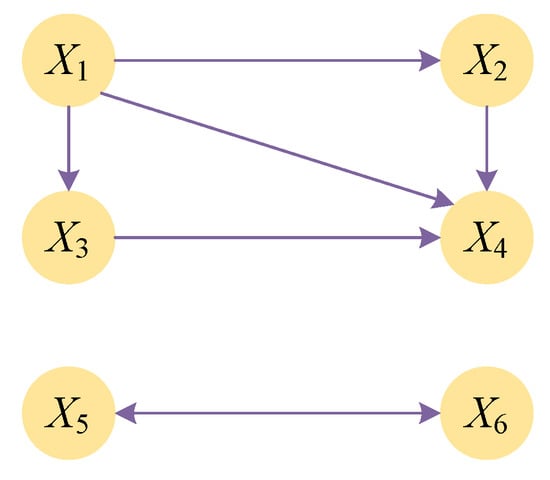

The causal relationships obtained by each method are shown in Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5, with the corresponding causal graphs shown in Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12.

Table 3.

Approximate inference results of transformer-based information gain.

Table 4.

Granger causality analysis method.

Table 5.

TVTE causality analysis method.

Figure 10.

Information gain chain with transformer.

Figure 11.

Causal analysis based on Granger method.

Figure 12.

Causal analysis based on TVTE.

According to Figure 10, the information flow chains can be represented as , , , and . Figure 11 shows the information flow chains as , , and . Figure 12 indicates information flow chains of , , , , and .

The causal paths obtained by Granger causality analysis differ most from the actual paths in Figure 6, indicating nonlinear relationships between flatness/thickness and variables that Granger causality cannot handle due to its linear assumption. TVTE-based causal inference produces paths closer to Figure 6, but still has significant directional errors in information transfer between variables. The transformer-based information gain chain generates the causal paths that are most consistent with Figure 6, more accurately reconstructing the true causal relationships.

Table 6 compares the proposed method with Granger, TVTE, the PC algorithm, and LiNGAM. The results show that our method outperforms the others in accuracy, recall, and F1-score. PC and LiNGAM rely on the linear ICA assumption, limiting them to linear relationships and making them less suitable for the nonlinear coupling common in hot rolling. Granger captures time dependence but typically uses fixed-lag modeling, which struggles under changing operating conditions. In contrast, the proposed transformer-based information gain framework effectively models nonlinear causal correlations and complex dynamic couplings, adaptively adjusts causal influence with process state changes via self-attention, and provides interpretable attention weights that quantify the contribution of variables and their time slices to quality outcomes.

Table 6.

Method comparison.

To further evaluate the robustness and industrial applicability of the proposed causal inference framework, we conducted uncertainty, sensitivity, and generalization analyses. The uncertainty was quantified through multiple Monte Carlo training experiments with different random initializations and sampling conditions; the variance of attention-derived causal strengths remained below 0.07 across repeated runs, indicating stable causal edge confidence. Sensitivity analysis was performed by perturbing key process variables within ±5%–±10% of realistic operating fluctuations and masking selected input features. The resulting causal pathways exhibited consistent directionality and preserved more than 90% of the major inferred causal edges, demonstrating robustness against measurement noise and process disturbances. In addition, the model based on data training of one production line was tested on independent data sets with different rolling schedules and equipment configurations collected by another production line to evaluate the cross-site generalization ability. Based on the overlap rate of causal edges, the discovered causal structure maintains a structural consistency of more than 85%, highlighting its strong adaptability to different industrial conditions and confirming its practical effectiveness in multi-plant deployment.

5.3. Practical Deployment Feasibility in Industrial Hot Rolling

To demonstrate industrial applicability, the proposed causal inference framework is designed to be directly integrated into existing Level-2 automation systems without additional hardware modification. The model processes real-time process data streams (50–200 Hz sampling frequency) and updates causal indicators every 1–5 s, fully matching the decision cycle of thickness and shape control. Benefiting from efficient transformer inference, each forward computation requires less than 40 ms on a standard industrial server, ensuring real-time causal tracing and early warning alerts for potential defects. In production deployment, the inferred causal pathways are utilized to perform targeted corrective interventions, including adaptive tuning of the roll thermal crown, bending force distribution, roll gap, and cooling strategy. This capability significantly shortens the diagnosis-to-action latency compared with conventional correlation-based monitoring or offline expert analysis, thereby reducing defect propagation risks and improving overall operational stability. Furthermore, the proposed framework supports both offline and online operational modes. Offline analysis enables root-cause investigation for historical production deviations and assists in determining long-term process optimization strategies. Online monitoring continuously evaluates dynamic causal influence among critical variables, with actionable results fed back to the control system for timely parameter adjustment. While most responses can be executed immediately, certain control actions may exhibit slight inherent delays due to mechanical and thermal inertia in the rolling equipment. Overall, the proposed system provides high engineering feasibility with a favorable cost–benefit profile, contributing to improved product quality and yield in industrial hot rolling operations.

6. Conclusions

This paper focuses on the hot strip rolling process and employs the proposed dynamic causal inference framework to conduct root-cause tracing with time-delay characteristics, addressing the common delayed effects in industrial process data and revealing the dynamic formation mechanisms of thickness fluctuations and shape distortions. On the methodological level, the proposed approach overcomes the limitations of traditional causal analysis techniques. The research first analyzes and clarifies the dynamic interaction patterns among the various factors that influence strip thickness and shape quality. Building on this foundation, the proposed framework adopts a DTW–MI correlation matrix to effectively resolve temporal misalignment in multi-source industrial data, then introduces a transformer-based information gain approximation mechanism to directly learn dynamic information flow relationships among variables. These methods significantly improve the accuracy and engineering applicability of causal analysis. Future research can be expanded in the following aspects: first, for time-varying delay modeling, online learning mechanisms can be incorporated for dynamic delay parameter estimation; second, for multimodal data fusion, more efficient feature extraction and alignment methods need to be developed; finally, for causal reasoning frameworks, tighter integration of physical priors with deep learning can be explored.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Z. and J.C.; Methodology, S.Z.; Software, J.C.; Validation, S.Z. and J.C.; Formal analysis, S.Z.; Investigation, J.C.; Resources, S.Z.; Data curation, J.C.; Writing—original draft, S.Z. and J.C.; Writing—review & editing, S.Z. and J.C.; Visualization, J.C.; Supervision, S.Z.; Project administration, S.Z.; Funding acquisition, S.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Factors affecting plate thickness control.

Table A1.

Factors affecting plate thickness control.

| First Indicator | Secondary Indicator | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Process parameter factors | Rolling force | The fluctuation of rolling force directly causes changes in the roll gap, affecting the thickness of the outlet |

| Temperature field | Temperature affects the deformation resistance of materials, thereby altering the rolling force | |

| Tension | The variation of tension between racks changes the thickness distribution by affecting the stress state | |

| Equipment and control system factors | Automatic Thickness Control (AGC) system | The fluctuation of rolling force directly causes changes in the roll gap, affecting the thickness of the outlet |

| Rolling mill stiffness | The rolling mill undergoes elastic deformation under stress, which affects the thickness accuracy | |

| Roll status | Roll wear, changes in thermal convexity, or eccentricity can cause changes in the shape of the roll gap | |

| Material and incoming material factors | Uneven thickness and hardness of incoming materials | The thickness deviation or compositional segregation of continuous casting billets can cause fluctuations in rolling force and thickness |

| Organizational performance anisotropy | Grain orientation (texture) leads to uneven deformation, which may cause thickness fluctuations |

Table A2.

Factors affecting shape control.

Table A2.

Factors affecting shape control.

| First Indicator | Secondary Indicator | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Roll system factors | Initial convexity of rolling mill | The initial contour design of the rolling mill affects the shape of the roll gap |

| Roll thermal convexity | During the rolling process, the rolling rolls expand unevenly due to heating, changing the shape of the roll gap | |

| Roll wear | After long-term use, the contour of the rolling mill changes, affecting the accuracy of shape control | |

| Process control factors | Bending roller force control | Adjust the deflection of the working roll by applying bending force through a hydraulic cylinder to improve the shape of the plate |

| Rolling force distribution | Uneven lateral rolling force can lead to residual stress and generate wave shapes | |

| Segmented cooling control | By adjusting the flow rate of cooling water to control the local temperature of the rolling mill and correct the plate shape | |

| Incoming material condition factors | Incoming board convexity | The flatness problem of the upstream rack will be inherited to the downstream process |

| Uneven material properties | Uneven deformation resistance caused by compositional segregation or organizational differences |

References

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, J. Intelligent fault diagnosis of steel production line based on knowledge graph recommendation. Control. Theory Appl. 2024, 41, 1548–1558. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, X. Leveraging Knowledge Graph Reasoning in a Multihop Question Answering System for Hot Rolling Line Fault Diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 3505014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Sun, J.; Peng, Y.; Wu, Z.; Yang, J. Hot-rolled strip thickness diagnosis and abnormal transmission path identification based on sub stand strategy and KPLS-MIC-TE. J. Frankl. Inst.-Eng. Appl. Math. 2024, 361, 106622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Shi, F.; Peng, K. A federated learning based intelligent fault diagnosis framework for manufacturing processes with intraclass and interclass imbalance. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2025, 36, 036203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, J.; Shi, Y.; Wang, X.; Yang, Q.; Sun, Y.; Li, J. A novel framework of process monitoring and fault diagnosis for steel pipe hot rolling. Ironmak. Steelmak. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Yin, H.; Zhou, H.; Cai, L.; Qin, Y. A Zero-Sample Fault Diagnosis Method Based on Transfer Learning. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informaticsieee Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, 20, 11542–11552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Kai, W.; Pu, W. Quality relevant over-complete independent component analysis based monitoring for non-linear and non-Gaussian batch process. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2020, 205, 104140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, C.; Chen, S.; Li, X.; Zhang, L. Research status and prospect of intelligent modeling, fault diagnosis and cooperative robust control for whole rolling process quality. Metall. Ind. Autom. 2022, 46, 38–47. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Peng, K.; Dong, J. A nonlinear full condition process monitoring method for hot rolling process with dynamic characteristic. ISA Trans. 2021, 112, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xu, Y. Study on rolling force fluctuation and thickness thinning of finished strip in PL-TCM. Steel Roll. 2023, 40, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Yang, Q.; Wang, X. Root cause analysis of thickness anomaly for cold rolled strip based on cause inference. China Metall. 2023, 33, 94–101. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.-S.; Yan, Z.; Yao, Y.; Huang, T.-B.; Wong, Y.-S. Systematic procedure for Granger-causality-based root cause diagnosis of chemical process faults. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 9500–9512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Qin, S.J.; Yuan, T. Data-driven root cause diagnosis of faults in process industries. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2016, 159, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.-N.; Pan, Y.-J.; Liu, L.-L.; Gao, Z.-G.; Qin, W. Reconstructing causal networks from data for the analysis, prediction, and optimization of complex industrial processes. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 138, 109494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, B.; Auret, L.; Bauer, M.; Groenewald, J.W.D. Comparative analysis of Granger causality and transfer entropy to present a decision flow for the application of oscillation diagnosis. J. Process Control 2019, 79, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Wang, J.; Chen, T.; Shah, S.L. Cause-effect analysis of industrial alarm variables using transfer entropies. Control Eng. Pract. 2017, 64, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Pi, D.; Qiu, S.; Wang, X.; Guo, C. Data-driven identification model for associated fault propagation path. Measurement 2022, 188, 110628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, B.; Ma, F.; Zheng, Q.; Yao, L.; Zhang, C.; Mohamed, M.A. A concurrent fault diagnosis method of transformer based on graph convolutional network and knowledge graph. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 837553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Dong, J.; Peng, K. A practical root cause diagnosis framework for quality-related faults in manufacturing processes with irregular sampling measurements. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 3511509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, F.; Yang, B.; Yu, S.; Zou, S.; Wang, X.; Zhao, J.; Wen, C. A unified model integrating Granger causality-based causal discovery and fault diagnosis in chemical processes. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2025, 196, 109028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modirrousta, M.; Memarian, A.; Huang, B. Entropy-enhanced batch sampling and conformal learning in VGAE for physics-informed causal discovery and fault diagnosis. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2025, 197, 109053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathari, S.; Tangirala, A.K. Efficient reconstruction of granger-causal networks in linear multivariable dynamical processes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 11275–11294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, U.; Ha, D.; Shin, S.; Shaukat, N.; Zahid, U.; Han, C. Estimation of disturbance propagation path using principal component analysis (PCA) and multivariate granger causality (MVGC) techniques. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 7260–7272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhao, C. Multi-lag and multi-type temporal causality inference and analysis for industrial process fault diagnosis. Control Eng. Pract. 2022, 124, 105174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).