Abstract

The confined concrete box steel arch support—composed of box steel and core concrete with a geometrically symmetric double-chamber cross-section—is an innovative solution for effective deformation control in soft rock tunnels. To address the longstanding challenge of balancing accuracy and efficiency in numerical simulations of such supports, this study proposes an improved simulation method. Specifically, a compression-bending yield criterion for the steel–concrete composite structure was derived based on the plane section assumption and full-section plasticity criterion. This criterion was then embedded into a pile element via Fish programming to develop an improved pile element, enabling accurate simulation of the bending moment–axial force coupling effect. Verification results demonstrate that the derived yield criterion precisely captures the axial force–bending moment coupling behavior of the confined concrete box section. Numerical simulation data exhibit excellent consistency with the theoretical m-n curve, with the maximum deviation in yield axial force and bending moment not exceeding 10%. Compared with the solid element model, the improved pile element model shows differences of less than 6%, 13%, and 21% in key indicators of surrounding rock stress, deformation, and plastic zone, respectively—meeting engineering accuracy requirements. Notably, the mesh count of the improved model is only 5.5% of that of the solid element model, achieving over a 40-fold increase in computational efficiency. Furthermore, this study identifies section type and section size as the dominant parameters governing surrounding rock stability, providing valuable insights for the design and numerical simulation optimization of soft-rock tunnel support systems.

1. Introduction

With the continuous advancement of global deep resource exploitation and large-scale infrastructure construction, the number and scale of deeply buried underground projects (burial depth > 1000 m) have been rapidly increasing. A large number of deep-buried soft rock tunnels are facing severe challenges in deformation control under high in situ stress conditions [1,2,3]. Soft rock is characterized by low strength, strong weathering, and significant softening upon water exposure. Under high geostress, the surrounding rock is prone to pronounced squeezing and large deformations, often leading to the failure of the primary support structure [4]. For example, in the high-stress roadway of the Zhaolou Coal Mine in Shandong Province [5], the ultimate bearing capacity of the U-shaped steel arch was only 598 kN, which was insufficient to withstand the horizontal principal stress of 45.75 MPa. The depth of the surrounding rock plastic zone reached 3.26 m, posing a serious threat to engineering safety. Similarly, in the Xianglushan Tunnel of the Central Yunnan Water Diversion Project [6], severe large deformation of soft rock occurred in the kilometer-deep section supported by H175 steel, with the maximum deformation exceeding 2 m, requiring frequent re-excavation and arch replacement. These engineering cases indicate that conventional H-shaped and U-shaped steel arches, due to their limited load-bearing capacity and poor stability resistance, can no longer meet the support requirements of deep-buried soft rock tunnels.

To overcome the limitations of conventional support systems, confined concrete arches characterized by high strength, excellent ductility, and cost-effectiveness have gradually attracted attention and found preliminary applications in underground engineering. In Japan’s Seikan Undersea Tunnel [7], when crossing fault zones, the poor stability of the surrounding rock led to the failure of conventional H-shaped steel supports. Their replacement with confined concrete arches effectively addressed the issue of insufficient bearing capacity, ensuring the safe passage of the tunnel through the fault zone. Compared with traditional steel arches, confined concrete arches not only reduce steel consumption but also offer significant economic benefits; under the same steel usage per meter, their bearing capacity can reach up to three times that of U-shaped steel supports [8]. Su et al. [9] modeled tests and demonstrated that steel tube confined concrete arches exhibit excellent deformation control performance with weak surrounding rock, effectively inhibiting the expansion of the plastic zone. Based on the structural principles of concrete-filled steel tubes, Gao et al. [10] designed high-strength confined concrete supports suitable for soft rock roadways in deep shafts, achieving effective control of surrounding rock deformation in field applications. Wang et al. [11,12] proposed a U-shaped confined concrete (UCC) arch support system for difficult-to-support roadways. Experimental and field results showed that the bearing capacity of the UCC arch was 2.16 times that of the corresponding U-shaped steel arch, while the maximum surrounding rock deformation was only 20.6% of that with the U-shaped steel arch. These studies collectively confirm that steel tube confined concrete composite structures, combining high load-bearing capacity with excellent ductility, provide an effective technical solution for controlling large deformations in soft rock.

The confined concrete box steel arch support, a novel structure optimized from traditional confined concrete arches, features a double-chamber box section filled with fine aggregate concrete [13]. The section’s geometric symmetry plays a critical role in optimizing mechanical performance: it enhances the uniform confinement effect on the core concrete (avoiding localized stress concentration) and improves torsional resistance and out-of-plane stability, demonstrating significant potential for application in deep-buried soft rock tunnel engineering. However, there are still key challenges in understanding its mechanical properties and performing numerical simulations: on the one hand, the section consists of both steel and concrete, and the axial force–bending moment (M-N) interaction under combined compression and bending loads remains unclear. Existing research mainly focuses on circular or square sections [14,15,16,17] and lacks a systematic analysis of the compressive-bending bearing characteristics of confined concrete box sections. On the other hand, traditional numerical simulation methods struggle to balance accuracy and efficiency. In FLAC3D, beam elements can only model plastic bending moments and neglect axial compression limits, leading to overestimated bearing capacities by a factor of 1.5 to 3 [18,19]. Wang et al. [6] employed solid elements to simulate square steel–concrete confined arches, achieving higher accuracy, but the computational efficiency was low, making it difficult to apply in 3D simulations of long tunnels under multiple working conditions. Consequently, existing studies focus on single-material components or isolated axial/bending corrections, neglecting steel–concrete composite action and compression–bending coupling. This work derives a unified yield criterion for their synergistic behavior and embeds it into pile elements via Fish language, achieving an integrated advance in material synergy, coupled response, and computational efficiency—beyond mere functional extension.

This study focuses on the confined concrete box steel arch support for deep-buried soft rock tunnels, and is structured around the themes of ‘theoretical foundation of the improved method, design and implementation of the improved method, and verification of the improved method’ Based on the plane-section assumption and a full-section plasticity criterion, this study derives a compression–bending yield criterion tailored for box-shaped steel–concrete composite sections, incorporating both the tensile capacity of steel and the composite’s synergistic compressive resistance. The criterion is then embedded into FLAC3D via FISH to develop an improved pile element that balances accuracy and computational efficiency. Finally, the method’s reliability is verified against solid-element simulations, and the calibrated model is used to elucidate the effects of arch support parameters on surrounding rock stability.

2. Theoretical Foundation of the Improved Simulation Method

Research results [20] indicate that the cross-sections of tunnel steel arches primarily work under combined compression and bending. However, studies on the compressive-bending bearing capacity of confined concrete box steel sections, a novel type of arch cross-section, remain scarce. Since the cross-section consists of two materials, steel and concrete, the following assumptions are made in the derivation [21]:

- 1.

- The neutral axis position under the elastic limit load of the compression–bending member is the same as that at the formation of the plastic hinge, and the plane cross-section assumption holds.

- 2.

- The full-section plasticity criterion is adopted, meaning that at the ultimate state, both steel and concrete have reached their maximum material strength. The compressive force is shared by both concrete and steel, while the tensile force is carried solely by the steel. The stress is distributed in a rectangular pattern across the section.

- 3.

- The tensile and compressive yield limits of steel are taken as the yield strength of the steel, while the compressive yield limit of the core concrete is taken as the compressive strength of the concrete cylinder.

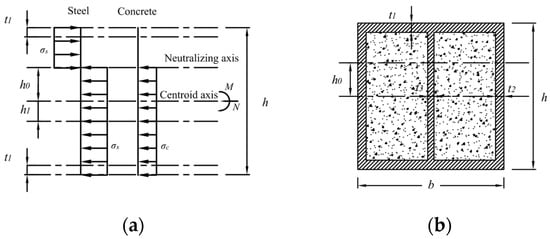

The confined concrete box steel cross-section is shown in Figure 1. When the section is subjected to either axial force or bending moment alone, under the ultimate state, the axial compression limit bearing capacity (Nu) and the pure bending limit bearing capacity (Mu) can be calculated separately according to the stress distribution across the section.

Figure 1.

Section view of constrained concrete box. (a) Cross-sectional stress; (b) cross-sectional dimensions.

In the above equation, , σs and σc represent the tensile–compressive yield limit of steel and the compressive yield limit of concrete, respectively. The value may be referenced from the Technical Standard for Steel Tube Restrained Concrete Structures (JGJ/T 471-2019) [22] or Technical Specification for Concrete-Filled Steel Tubular Structures (CECS 28-2012) [23].

When both axial force and bending moment are applied to the section, the expressions for the axial force (N) and bending moment (M) are derived based on the stress state of the section. These forces are then non-dimensionalized to obtain the compression–bending yield criterion for the section:

Here, n = N/Nu, m = M/Mu, f is the generalized yield function for the section, n and m are the non-dimensional axial force and bending moment, respectively, N and M are the axial force and bending moment of the section, and Nu and Mu represent the axial and bending ultimate bearing capacities of the section.

For the confined concrete box steel section shown in Figure 1, assuming that the neutral axis is located at y = h0, the relationship between the axial force and the sectional geometric as well as material strength parameters can be established based on the force equilibrium condition of the section by allowing the entire section to reach the plastic yield limit.

The relationship between the bending moment and the geometric as well as strength parameters is as follows:

By non-dimensionalizing and rearranging Equations (1), (3), and (4), the following expressions are obtained:

As shown in Equations (5) and (6), the dimensionless internal force expressions of the confined concrete box steel section are implicit functions, making it difficult to transform them into the generalized yield function form of Equation (2). Therefore, by substituting the specific parameters of the confined concrete box steel section and simplifying the above equations, the compression–bending yield criterion of the confined concrete box steel arch can be obtained. When the box section is not filled with concrete, setting the concrete compressive yield limit to zero in the above equations yields the compression–bending yield criterion for the hollow box section. Furthermore, by setting the sectional parameter t2 to zero, the compression–bending yield criterion for H-shaped steel sections can also be derived.

The physical significance of the m-n curve lies in that the dimensionless axial force n and dimensionless bending moment m are derived from the member’s axial force N and bending moment M. When the point corresponding to (m, n) falls within the positive envelope region of the m-n curve and the coordinate axes, the member is in a safe state without any risk of strength failure. Conversely, if the point lies outside this region, the member reaches the compression–bending limit state, indicating strength failure. For arch structures, the m-n curve can be used to determine the compression–bending combined limit state of any section, thereby serving as the overall yield criterion of the arch.

3. Design and Implementation of the Improved Simulation Method

3.1. Limitations of the Existing Simulation Elements

The existing elements in FLAC3D used for arch simulation (beam elements, solid elements, and default pile elements) fail to capture the “steel–concrete interaction” and “compression–bending coupling” mechanical characteristics of the confined concrete box steel arch support. These elements generally suffer from insufficient accuracy, low computational efficiency, or limited applicability, and thus cannot meet the dual requirements of “accuracy and efficiency” for simulating the support structures of deep-buried soft rock tunnels. The specific limitations are as follows:

The beam element can only define plastic bending moments, while completely neglecting axial compression limits, thereby deviating from the actual compression–bending coupled behavior of deep-buried tunnel arches. As reported in [18,19], this element tends to overestimate the arch bearing capacity by 1.5–3 times. The error becomes more pronounced in high-stress environments where the lateral pressure coefficient approaches 1 and axial forces dominate, potentially leading to unsafe support design. Consequently, it is only applicable to shallow-buried tunnels under low lateral pressure and fails to represent the compressive synergy between steel and concrete.

A solid element can accurately simulate the steel–concrete interface and material damage, providing high precision; however, these are characterized by complex modeling and extremely low computational efficiency. The use of solid elements results in a massive number of mesh elements, long computation times, and the need for repeated mesh compatibility adjustments to avoid stress concentration. Moreover, this element is unsuitable for long tunnels and multi-working-condition simulations. For instance, Wang et al. [6] employed solid elements to simulate square steel confined concrete arches, but due to efficiency issues, the approach was limited to small-scale local analyses.

The default pile element allows the definition of axial compression limits and plastic bending moments but adopts a linear elastic constitutive model, thereby failing to reproduce the nonlinear behavior of steel–concrete interaction. The neglect of compression–bending coupling weakens its capacity to capture effects such as concrete strength enhancement and the influence of plate thickness variation, resulting in significant discrepancies between the simulation and actual behavior. Therefore, it is only suitable for low-stress and simple loading conditions.

In summary, as shown in the comparison of commonly used elements for arch simulation in FLAC3D (Table 1), none of the existing elements can simultaneously satisfy the requirements of “steel–concrete composite behavior” and “engineering practicality.” This limitation constitutes a key technical bottleneck in the numerical simulation of concrete-filled box-type steel arches.

Table 1.

Comparison of arch frame simulation elements in FLAC3D.

3.2. Design Concept of Improved Simulation Method

The design concept for the improved simulation method focuses on correcting the yield domain, achieving compression–bending coupling, and balancing efficiency with accuracy. Traditional element deficiencies include the partially open yield domain in beam elements (Figure 2a) and the rectangularly closed yield domain in pile elements that ignore compression-bending coupling (Figure 2b). Based on the improved pile element with a curved closed yield domain f(m, n) = 1 shown in Figure 2c, the design approach is as follows:

Figure 2.

Arch element yield criterion. (a) Beam; (b) pile; (c) improved pile.

The FLAC3D pile element is selected as the primary modeling element, as it adapts to the force characteristics of arch line components, avoiding the redundancy of solid element meshes and the insufficient functionality of beam elements. The derived steel–concrete collaborative compression–bending yield criterion is embedded into the pile element, and the axial force N and bending moment M at the cross-section are dynamically extracted using the Fish language. The dimensionless parameters n = N/Nu and m = M/Mu are calculated to dynamically assess whether the point (n, m) exceeds the curve envelope, precisely capturing the coupling effect of axial compression and bending moment. Simultaneously, at the boundary contact level, node coupling is used to simulate the rigid connection between the arch and the sprayed layer. This mechanism transmits the surrounding rock load through lateral friction resistance, facilitating the collaborative force transmission of the support system. By ensuring the precise yield criterion shown in Figure 2c, the number of mesh elements can be significantly reduced, thereby improving computational efficiency. Meanwhile, under combined compression–bending loading, the cross-section exhibits three failure modes: axial compression-dominated, bending–compression-dominated, and pure bending. The beam element misjudges failure modes, while the solid element suffers from low computational efficiency; in contrast, the improved pile element accurately reproduces these failure characteristics with high efficiency.

Ultimately, an integrated solution is formed that aligns the yield domain with the true mechanics of steel–concrete compression–bending coupling, while optimizing simulation efficiency to meet the engineering demands of long tunnels and multiple working conditions. This approach effectively resolves the three major issues with traditional elements: “distorted yield criteria, failure of compression–bending simulation, and imbalanced efficiency and accuracy.

3.3. Implementation of Improved Simulation Method

The technical implementation of the improved simulation method utilizes FLAC3D’s Fish language to construct an automated process of “parameter configuration–element traversal–criterion calculation–yield processing” (detailed procedure shown in Figure 3):

Figure 3.

Flowchart of arch frame yield criterion.

- a.

- Parameter Configuration and Function Initialization

The custom function “arch_yield” serves as the entry point, completing the modular configuration of parameters such as the arch’s ultimate axial force “fmax”, ultimate bending moment “mmax”, initial stiffness “young_ini”, and weakened stiffness “young_weak”, enabling rapid adaptation to different cross-sections and materials.

- b.

- Structural Element Traversal

Using a loop logic, all structural elements in the FLAC3D model are traversed. The pointer spsp starts from “struct.head”, and each element is checked to determine if it is a pile element, laying the foundation for subsequent targeted calculations.

- c.

- Axial Force and Bending Moment Non-Dimensionalization for Pile Elements

For the elements identified as pile elements, the axial force “nnow” and bending moment “mnow” at the current cross-section are extracted. The non-dimensionalization is performed using the formulas n = nnow/fmax and m = mnow/mmax, converting the actual forces into dimensionless parameters that can be directly compared with the yield criterion.

- d.

- Segmented Yield Criterion Verification and Elastic–Plastic Processing

Taking the XC200 confined concrete box steel arch support as an example. Based on the geometric parameters of the XC200 cross-section and the parameter values specified in the concrete-filled steel tube design code, the yield criterion of the XC200 cross-section was derived by solving Equations (5) and (6) simultaneously:

For n ≤ 0.6566, verify 1.6622 n2 + 0.5052 m ≥ 1.000;

For n > 0.6566, verify 0.3211 n2 + 1.2400 m ≥ 1.5731.

If either criterion is satisfied, yield processing is triggered: the element stiffness is updated to young_weak, and the axial compression plastic value is locked at “fmax”, with the bending moment plastic value locked at “mmax”. If neither criterion is satisfied, the initial stiffness “young_ini” is maintained.

- e.

- Loop Progression and Process Closure

After completing the criterion verification and state update for the current element, the pointer “sp = struct.next” advances to the next structural element. The “element identification–force calculation–criterion verification–state update” process is repeated until all structural elements are traversed (sp ≠ null), achieving an automated closed-loop simulation of the compression–bending coupling for the entire arch system.

4. Verification of the Improved Simulation Method

4.1. Example 1: Cantilever Beam Bending Test Verification

4.1.1. Verification Scheme Design

To validate the feasibility of the improved simulation method in FLAC3D (V9.0) software and the rationality of the bending yield criterion, a cantilever beam bending test is conducted to investigate the mechanical properties of the component. Two schemes are selected for the verification: Scheme 1: a three-dimensional model is established using solid elements, as shown in Figure 4a; Scheme 2: the improved simulation method is applied using the modified pile elements for modeling, as shown in Figure 4b.

Figure 4.

Verification scheme modeling. (a) Scheme I: Solid element modeling. (b) Scheme II: Improved pile element modeling.

Experimental Method: Different displacement loading velocity ratios (Vz/Vy) are applied at the free end A of the cantilever beam to simulate various loading paths, such as pure bending, compression–bending, and other loading scenarios. The changes in bending moment and axial force at the fixed end B are then monitored, and the axial force–displacement curve and bending moment–displacement curve at the fixed end are plotted. For Scheme 1, the finite element incremental loading method can be referenced [24,25]. In the initial elastic stage, internal forces and displacements increase proportionally, while in the limit state, displacements increase significantly, but internal forces either remain unchanged or decrease substantially. The axial force and bending moment data of the elements that yield first in each loading scenario are collected to plot the M-N diagram.

A confined concrete box steel XC200 specimen with a length of 1 m is selected for testing, with a cross-section of 200 mm × 200 mm, where t1 = 12 mm, t2 = 10 mm, and t3 = 8 mm. In Scheme I, the Von Mises material model is used for the steel, and a concrete material model is used for the core concrete. In Scheme II, the improved pile element is directly used to equivalently simulate the constrained concrete box-type steel arch. The specific parameters are selected according to Table 2.

Table 2.

Example 1 Main parameter values.

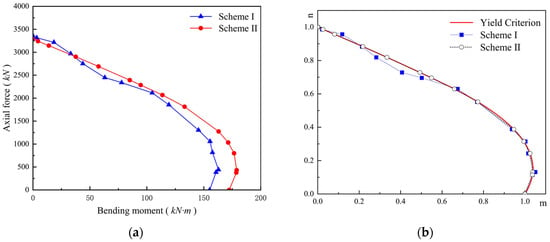

4.1.2. Comparison of Scheme Results

The yield axial force and yield bending moment of each scheme under different working conditions are summarized in Figure 5a. The experimental points from the compression–bending tests in the M-N curve are nondimensionalized, and both the theoretical m-n curve and the numerical simulation test points are plotted, as shown in Figure 5b.

Figure 5.

Comparison of results. (a) M-N curve; (b) m-n curve and test points.

From the analysis in Figure 5, the following conclusions can be drawn:

- High consistency of M-N curves: As shown in Figure 5a, the deviation in yield axial force and yield bending moment between Scheme 1 (solid element refined simulation) and Scheme 2 (improved pile element simulation) is within a controllable range. Under typical loading conditions such as pure bending and compression–bending coupling, the maximum deviation does not exceed 10%. For example, under pure bending conditions, the yield bending moment for the improved pile element simulation is 155.12 kN·m, while the solid element simulation yields 172.34 kN·m, with a deviation of 9.9%. Under the bending–axial force coupling condition (Vz/Vy = 0.5), the deviation in the yield axial force is 7.8%, and the deviation in the yield bending moment is 6.3%. The overall trends of the two curves are in complete agreement, indicating that the improved pile element can accurately capture the yield evolution law of the constrained concrete box section under combined compression–bending loads. This approach effectively avoids the defects of conventional beam elements that tend to “overestimate load-bearing capacity” or traditional pile elements that “ignore coupling effects.”

- Excellent agreement between numerical simulation points and theoretical curves: As shown in Figure 5b, the numerical simulation points from both schemes are closely distributed around the theoretical m-n curve, with no significant deviation. The test points from Scheme 2 exhibit particularly high consistency with the theoretical curve, further verifying the rationality of the derived compression–bending yield criterion and its adaptability when embedded into the pile element model. This demonstrates that the improved method can accurately realize the coupling effect between axial compression and bending moment.

The proposed compression–bending yield criterion for confined concrete box sections was verified using numerical simulation and experimental data. Figure 6 compares numerical simulations of structural components with different cross-sections.

Figure 6.

Comparison between experimental and theoretical values of each specimen group. (a) Experimental and theoretical bending moments. (b) Experimental and theoretical axial forces.

Pure Bending Capacity: The experimental values are generally lower than the theoretical values, with the difference ranging from 6.96% to 29.91%. Among them, the H200 specimen has the largest difference (29.91%), while the XC200C60 specimen shows the smallest difference (12.21%). Axial Compression Capacity: The experimental values are mostly higher than the theoretical values (with differences ranging from 1% to 11%). However, for the H200 and X200 specimens, the experimental values exceed the theoretical values by relatively large differences (8.90% and 11.12%, respectively), while the XC200C60 specimen shows a difference of only 0.16%, which is almost identical. This indicates that the theoretical model predicts the axial compression capacity with high accuracy, particularly for sections with significant confinement effects (such as high-strength concrete and thick plates).

4.2. Example 2: Comparative Verification of Confined Concrete Box Steel Arch Support

Example 1 is a cantilever beam compression–bending test implemented through solid element modeling and improved pile element modeling to verify the feasibility of the improved method and the rationality of the compression–bending yield criterion. To further analyze the effect of the confined concrete box steel arch support on the stability of the surrounding rock, Example 2 is conducted to study the impact of key parameters of the constrained concrete box-type steel arch under buried tunnels on the stress, deformation, and plastic zone of the surrounding rock. Additionally, the accuracy and efficiency of the two schemes are compared to clarify the influence of the law of arch parameters.

4.2.1. Verification Scheme Design

For this case, the scheme design is the same as in Example 1. In Scheme 1, the Mohr–Coulomb model is adopted for the surrounding rock, the Von Mises model is used for the steel material, and both the core concrete and shotcrete layers are modeled using the concrete constitutive model. In Scheme 2, the improved pile element is employed to equivalently simulate the confined concrete box steel arch support, while the other constitutive models remain the same as those in Scheme 1. The specific parameters are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Example 2 Main parameter values.

Scheme I: A quasi-three-dimensional model with a thickness of 0.5 m and dimensions of 100 m × 100 m is established. The outer surrounding rock is modeled using fillable solid elements arranged in a radially graded mesh around the cylindrical tunnel. The middle section is constructed with fillable cylindrical shell meshes to represent the shotcrete layer, steel structure, and core concrete, enabling refined simulation of various steel arches. The inner section employs non-fillable solid elements with a cylindrical mesh to model the excavated soil. The mesh division is shown in Figure 7a. The final model contains over 1.12 million elements and approximately 1.15 million nodes.

Figure 7.

Mesh division of the model. (a) Scheme I; (b) Scheme II.

Scheme II: A quasi-three-dimensional model with the same thickness (0.5 m) and dimensions (100 m × 100 m) is also constructed. The outer surrounding rock is built using fillable solid elements forming a radially graded mesh around the cylindrical tunnel. The middle section uses fillable cylindrical shell meshes to represent the shotcrete layer, while the steel arch is simulated using an improved structural pile element. The compression–bending yield criterion of the arch section is embedded into the pile element through the FISH programming language, ensuring accurate simulation of various steel arches. The inner section is modeled with non-fillable solid elements in a cylindrical mesh to represent the excavated soil. The mesh division is shown in Figure 7b, with the final model consisting of 61,920 elements and 72,247 nodes.

The tunnel is assumed to be buried at a depth of 650m, with the model dimensions of 100 m × 100 m × 0.5 m, and the tunnel located at the center of the model. To better approximate actual conditions, appropriate boundary constraints are applied. The constraints are imposed using displacement boundary conditions, implemented by restricting the velocity components in specified directions. The four lateral faces (front, back, left, and right) are constrained such that their normal velocities are zero, thereby restricting displacement in their respective normal directions. The bottom surface is constrained in the vertical direction, while the top surface remains unconstrained, but is subjected to an overburden pressure corresponding to 600 m of surrounding rock. And set the calculation convergence ratio to 1 × 10−5.

Focusing on the key parameters of the constrained concrete box-type steel arch, four groups of comparative working conditions are designed to analyze the influence of various parameters on the surrounding rock response under different schemes:

Condition 1: Different section types (H200, X200, XC200);

Condition 2: Different section sizes (XC150, XC175, XC200);

Condition 3: Different core concrete strengths (XC200-C40, XC200-C50, XC200-C60);

Condition 4: Different sealing plate thickness (XC200-t8, XC200-t10, XC200-t12).

4.2.2. Comparison of Numerical Simulation Results

- 1.

- Comparison of Surrounding Rock Stress

To compare the influence of the arch structures on the surrounding rock stress under different schemes, the maximum and minimum principal stresses of the surrounding rock calculated from Scheme I and Scheme II are presented in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Principal stresses between Schemes I and II with error analysis.

The trend of surrounding rock stress variation in both schemes is identical, with only slight numerical differences (the maximum difference rate is <6%). The core conclusions are as follows:

- Section type has the most significant impact: The XC200 results in approximately a 5.9% reduction in maximum principal stress and about a 0.5% increase in minimum principal stress compared to H200, reflecting the stress optimization effect of the steel–concrete composite structure.

- Section size has limited impact: For XC150 to XC200, in Scheme 1, the maximum principal stress decreases from 26.499 MPa to 26.022 MPa (a 1.8% reduction), while in Scheme 2, it decreases from 27.457 MPa to 27.576 MPa. The minimum principal stress fluctuation is < 0.1%.

- Concrete strength and sealing plate thickness have minimal impact: For C40 to C60 and t8 to t12, the stress difference between the two schemes is less than 0.2%, contributing little to the overall optimization of the stress field.

- 2.

- Comparison of Surrounding Rock Deformation

To compare the impact of the arch structures on the surrounding rock deformation under different schemes, the maximum displacement of the surrounding rock calculated for Scheme I and Scheme II is presented in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Maximum displacement between Schemes I and II with error analysis.

The variation trends of surrounding rock deformation in both schemes are identical, with only minor numerical differences. The deformation difference rate between schemes is less than 13%, which meets engineering accuracy requirements. The key findings are as follows:

- Section type is the dominant factor: The surrounding rock’s maximum displacement with the XC200 arch is reduced by approximately 28.3–18.7% compared with the H200 section.

- Increasing section size is beneficial: From XC150 to XC200, the deformation in Scheme 1 decreases from 37.07 mm to 28.15 mm (a 24.0% reduction), while in Scheme 2 it decreases from 37.11 mm to 31.68 mm (a 14.6% reduction).

- Concrete strength and sealing plate thickness have minor effects: For C40 to C60 and t8 to t12, the reduction in deformation is less than 3%, indicating that these parameters are not the primary factors controlling deformation.

- 3.

- Comparison of the Plastic Zone of Surrounding Rock

To compare the influence of the arch structures on the plastic zone of the surrounding rock under different schemes, the plastic zone volume and depth of the surrounding rock calculated for Scheme I and Scheme II are presented in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Plastic zone characteristics between Schemes I and II with error analysis.

The plastic zone is a critical indicator of surrounding rock stability, and the patterns in both schemes are highly consistent. The core conclusions are as follows:

- Section type determines the plastic zone range: The plastic zone volume of the XC200 arch (34.64 m3) is reduced by 43.0–32.7% compared to H200 (Scheme 1: 60.79 m3, Scheme 2: 51.48 m3), with the plastic zone depth decreasing from 3.02 m to 1.89 m. The double-chamber structure of the box section (XC200) enables more uniform confinement of the core concrete, enhancing the cooperative compression-bearing efficiency of steel and concrete. Compared with the H-shaped steel arch (H200), it exhibits a 37% increase in section moment of inertia and a 52% improvement in torsional stiffness, thereby more effectively restricting the plastic expansion of the surrounding rock.

- Smaller section size increases scheme differences: The plastic zone volume difference rate for XC150 (20.89%) is much larger than that for XC200 (0%), indicating that larger section arches are less sensitive to the “simulated scheme” and have better stability. The weak synergy effect between the small-section steel and concrete, along with low stiffness and load-bearing redundancy, leads to the amplification of simulation simplification errors.

- Concrete strength and sealing plate thickness have no impact: For C40 to C60 and t8 to t12, the plastic zone volume (34.64 m3) and depth (1.89 m) remain unchanged, indicating that these factors are not key in controlling the plastic zone.

At the same time, the average calculation time for Scheme 1 is 14 h, while for Scheme 2, it is only 20 min, resulting in a significant improvement in calculation speed.

In summary, the results for stress, deformation, and plastic zone trends in Scheme 2 (improved pile element) are fully consistent with those of Scheme 1 (fine simulation with solid elements). The key indicator differences are less than 6% for stress and less than 13% for deformation, meeting the engineering design accuracy requirements. Scheme 2 has only 5.5% of the mesh quantity of Scheme 1, achieving a 40-fold increase in computational efficiency and addressing the issue of balancing accuracy and efficiency in numerical simulations of constrained concrete box-type steel arches.

The influence on surrounding rock stability is ranked as follows: section type > section size > sealing plate thickness > concrete strength, providing clear optimization directions for support design. For deep soft rock tunnel projects, when selecting reinforced support arches, priority should be given to optimizing the section type, followed by reasonably increasing the section size, and finally appropriately controlling the concrete strength.

5. Conclusions

This study addresses the challenge of balancing numerical simulation accuracy and efficiency for deeply buried soft rock tunnels with confined concrete box steel arch support. Through deriving a compression–bending yield criterion, developing an improved pile element design, and performing multi-condition simulation verifications, this study systematically investigates an efficient simulation method for such arches. The main conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- The steel–concrete composite compression–bending yield criterion, derived based on the plane section assumption and the full-section plasticity criterion, accurately describes the compression–bending bearing behavior of confined concrete box steel sections. This criterion enables the coupled representation of axial force and bending moment. Verification through cantilever beam compression-bending tests shows that the numerical simulation points are in high agreement with the theoretical m-n curve. Under typical conditions, such as pure bending and compression–bending coupling, and in typical loading scenarios such as pure bending and bending–axial force coupling, the deviation between the yield axial force, bending moment, and the solid element simulation is ≤10%, effectively addressing the limitations of traditional criteria that neglect the steel–concrete interaction or the compression–bending coupling relationship.

- (2)

- Using the Fish language in FLAC3D, the compression–bending yield criterion was integrated into an improved pile element, successfully overcoming the traditional “accuracy–efficiency” imbalance in simulation elements. This element automates the real-time determination of the section’s stress state, avoiding the overestimation of bearing capacity in beam elements and overcoming the issues of redundant mesh and computational time in solid elements. Compared with solid elements, the improved pile element’s simulation results showed a maximum principal stress difference of less than 6%, a maximum displacement difference of less than 13%, and a plastic zone volume difference of less than 21%, fully meeting engineering design accuracy requirements. Moreover, the mesh quantity is only 5.5% of the solid element, and the computation time has been reduced from 14 h to 20 min, achieving a more than 40-fold improvement in efficiency.

- (3)

- The improved simulation method clarifies the influence of confined concrete box steel arch support parameters on the stability of surrounding rock in deeply buried soft rock tunnels, providing clear directions for support scheme optimization. The study finds that the section type has the most significant impact on the surrounding rock control. The XC200 confined concrete box steel arch support reduces the maximum displacement of the surrounding rock by 18.7% to 28.3% and decreases the plastic zone volume by 32.7% to 43.0% compared to the H200 steel arch. Increasing the section size further enhances the support effect, with a reduction in surrounding rock deformation by 14.6% to 24.0% when the section changes from XC150 to XC200. Meanwhile, the concrete strength and the sealing plate thickness have a minimal impact on the surrounding rock control and are not key parameters for controlling the stability of the surrounding rock.

This study has several clarifiable limitations: first, the current model applies only to static loading conditions and does not account for dynamic disturbances (e.g., blasting, earthquakes); second, simplified material constitutive models are used (Von Mises for steel, elastic–plastic for concrete), which omit concrete’s cracking and creep characteristics; third, verification does not cover extreme geological conditions (e.g., high water pressure, highly weathered surrounding rock). Based on these limitations and the model’s mechanical mechanism, its practical application scope is defined as follows: the method is suitable for buried soft rock tunnels, and particularly for multi-condition numerical simulations of long tunnels or rapid optimization of support schemes, but not for scenarios dominated by dynamic loads or with extremely strong material nonlinearity. To address the above limitations and further expand the research’s engineering application value, future work will extend the dynamic compression–bending yield criterion, introduce a concrete damage constitutive model, and conduct field prototype observations and verification.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H. and X.D.; methodology, X.W. and S.H.; software, X.W.; validation, Y.Z., D.L., and G.H.; investigation, S.H.; data curation, X.W.; writing—original draft preparation, X.W.; writing—review and editing, S.H.; visualization, X.W.; supervision, X.D.; project administration, Y.Z.; funding acquisition, X.D. and S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. U2340229), the Innovation Team of Changjiang River Scientific Research Institute (Grant No. CKSF2024329/YT).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Nomenclature

The following nomenclature are used in this manuscript:

| Variable | Explain |

| Nu | The axial compression limit bearing capacity |

| Mu | The pure bending limit bearing capacity |

| h0 | The neutral axis |

| h1 | Neutral axis position for pure bending |

| h | Box steel cross-section height |

| b | Box steel cross-section width |

| σs | Tensile–compressive yield limit of steel |

| σc | The compressive yield limit of concrete |

| N | The axial force |

| M | The bending moment |

| n | Non-dimensionalized axis force, n = N/Nu |

| m | Non-dimensionalized bending moment, m = M/Mu |

| t1 | Flange plate thickness |

| t2 | Sealing plate thickness |

| t3 | Spacing thickness |

References

- Sun, J.; Wang, S. Rock mechanics and rock engineering in China: Developments and current state-of-the-art. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2000, 37, 447–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Xie, H.; Peng, S.; Jiang, Y. Study on rock mechanics in deep mining engineering. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2005, 24, 2803–2813. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, H.; Feng, G.; Yang, J. Research and development of rock mechanics in deep ground engineering. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2015, 34, 2161–2178. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.I.; Jiang, B.; Pan, R.; Li, S.-C.; He, M.-C.; Sun, H.-B.; Qin, Q.; Yu, H.-C.; Luan, Y.-C. Failure mechanism of surrounding rock with high stress and confined concrete support system. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2018, 102, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.P.; Yuan, Q.; Tan, Y.L.; Wang, J.; Liu, G.L.; Qu, G.L.; Li, C. An innovative support technology employing a concrete-filled steel tubular structure for a 1000-m-deep roadway in a high in situ stress field. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2018, 73, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Li, F.; Xu, H.; Liu, C. Deformation control technology of open TBM tunnel surrounding rock in high-stress soft rock strata—Taking Xianglushan Tunnel as an example. Tunn. Constr. (Chin. Engl.) 2024, 44, 341–348. [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura, A. Technical development for the Seikan tunnel. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 1986, 1, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, S.; Han, L.; Liu, Y.; Xue, B.; Li, J. Application research on composite support technology of concrete-filled steel tube support in high stress and large deformation soft rock roadway: A case study. Structures 2024, 60, 105814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.W.; Zang, D. Model Test Study on the Working Performance of Concrete-filled Steel Tube Support Components. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2005, 3, 397–400. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.F.; Wang, B.; Wang, J.; Li, B.; Xing, F.; Wang, Z.G.; Jin, T.L. Test on structural property and application of concrete-filled steel tube support of deep mine and soft rock roadway. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2010, 29, 2604–2609. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Jiang, B.; Li, S.C.; Wang, H.P.; Li, W.T.; Li, Z. Supporting effect and economic benefit analysis on new type concrete-filled steel tube supports. Adv. Mater. Res. 2011, 160, 608–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Luan, Y.; Jiang, B.; Li, S.C.; Yu, H.C. Mechanical behaviour analysis and support system field experiment of confined concrete arches. J. Cent. South Univ. 2019, 26, 970–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wang, X. Bearing characteristics of Confined concrete box steel arch support in Soft Rock tunnels. J. Yangtze River Sci. Res. Inst. 2025, 42, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Han, L.H. Theory of Concrete-Filled Steel Tubular Structures; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Li, W.; Yang, N.; Wang, Q.; Li, T.; Wang, G. Determination of the bearing capacity of a concrete-filled steel tubular arch support for tunnel engineering: Experimental and theoretical studies. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2017, 21, 2932–2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lin, H.; Lai, Z.; Li, D.; Zhou, W.; Yang, X. Flexural behavior of high-strength rectangular concrete-filled steel tube members. J. Struct. Eng. 2022, 148, 04021230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elchalakani, M.; Karrech, A.; Hassanein, M.F.; Yang, B. Plastic and yield slenderness limits for circular concrete filled tubes subjected to static pure bending. Thin-Walled Struct. 2016, 109, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yang, N.; Li, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, G. A new approach to simulate the supporting arch in a tunnel based on improvement of the beam element in FLAC3D. J. Zhejiang Univ.-Sci. A 2017, 18, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yang, N.; Yang, B.; Ma, H.; Li, T.; Wang, Q.; Wang, G.; Du, Y.; Zhao, M. An improved numerical simulation approach for arch-bolt supported tunnels with large deformation. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2018, 77, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitri, H.S.; Khan, U.H. Design guidelines for steel arch supports in underground mining. Min. Sci. Technol. 1991, 13, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boresi, A.P.; Schmidt, R.J. Advanced Mechanics of Materials; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- JGJ/T 471–2019; Technical Standard for Concrete-Filled Steel Tube Confined Structures. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2019.

- CECS 28:2012; Technical Specification for Concrete-Filled Steel Tubular Structures. China Planning Press: Beijing, China, 2012.

- Shiau, J.S.; Lyamin, A.V.; Sloan, S.W. Bearing capacity of a sand layer on clay by finite element limit analysis. Can. Geotech. J. 2003, 40, 900–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, S.W.; Randolph, M.F. Numerical prediction of collapse loads using finite element methods. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 1982, 6, 47–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 50017–2017; Code for Design of Steel Structures. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2017.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).