Abstract

Attribute-Based Access Control (ABAC) has become the most suitable access control method for cloud environments due to its flexibility and fine-grained advantages. However, it suffers from issues such as insufficient dynamic adaptability and a lack of risk perception capabilities. The Zero Trust Architecture (ZTA) provides a new approach to addressing these problems through continuous trust evaluation, but its high dependence on the Policy Decision Point (PDP) component in the control plane introduces new security risks. To this end, this paper proposes a Zero-Trust Access Control Model based on Attributes and dynamic user Trust scores (AT-ZTAC). The model incorporates a trust evaluation module, which quantifies the user’s trustworthiness in real time through positive trust values and negative risk values, and dynamically integrates this quantification into access decisions to achieve fine-grained, dynamic, and secure authorization. In addition, to address the single-point trust risk of the PDP component, the model adopts a BLS-based threshold signature scheme to ensure the normal operation of the control plane even under limited intrusions, while supporting decision traceability. Theoretical analysis shows that this model significantly improves the overall security of the control plane. Experiments demonstrate that AT-ZTAC outperforms comparative models in terms of trust evaluation effectiveness, access decision throughput (reaching 1850 req/s, a 54% increase compared to traditional ABAC), and access control accuracy (reaching 96.8%). Compared with traditional solutions, it has advantages in flexibility, accuracy, and efficiency, demonstrating its potential for applications in cloud environments.

1. Introduction

Cloud computing has become a mainstream IT infrastructure due to its low cost, high performance, and high scalability, and is widely used in government services, finance, and enterprise digital businesses. However, inherent characteristics of cloud environments, such as resource virtualization and ambiguous service boundaries, pose severe challenges to traditional access control models in addressing dynamic access requirements and complex attacks [1]. According to IBM’s 2025 Cost of a Data Breach Report [2], cloud environments have become a major target for data breaches, with security incidents involving cloud data accounting for 85% of the total. Among these, misconfiguration and cloud credential leakage are the primary causes, accounting for 18% and 16% of all attack vectors, respectively. This highlights the urgent need for identity governance and dynamic access control mechanisms in cloud environments.

ABAC [3] is inherently suitable for the complexity and dynamism of cloud environments due to its fine-grained nature and flexibility. ABAC makes authorization decisions based on subject attributes (e.g., user role, department), object attributes (e.g., data sensitivity, resource type), environment attributes (e.g., time, location), and operation attributes. Compared to the Discretionary Access Control (DAC) model [4], Mandatory Access Control (MAC) model [5], or Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) model [6], ABAC better meets the dynamically changing access requirements of cloud environments.

Nevertheless, existing ABAC models applied in cloud environments still face the following key challenges [7,8,9]:

- Insufficient dynamic adaptability: Traditional ABAC models mainly rely on static or preconfigured attributes for one-time authorization decisions. Permissions are usually not adjusted dynamically after authorization, making it difficult to implement the principle of least privilege throughout the session and potentially leading to excessive permission retention.

- Lack of risk perception capabilities: Traditional models lack deep integration of real-time threat intelligence and user abnormal behaviors during deployment, limiting their ability to effectively identify and respond to malicious behaviors (e.g., malicious actions after user credential theft) or internal threats.

The Zero Trust Security Architecture [10], guided by the principle of “never trust, always verify”, emphasizes continuous authentication, trust evaluation, and dynamic authorization for all access requests, providing a new approach to cloud security. Theoretically, ZTA is highly compatible with ABAC, and the integration of ZTA can effectively address the aforementioned challenges. However, ZTA implicitly assumes absolute trust in the control plane; if the control plane is compromised, incorrect authorization decisions may occur, and the entire ZTA will no longer be secure [11,12].

To address these challenges, this study proposes a zero-trust access control model based on attributes and dynamic trust evaluation. The core innovations of this model are as follows:

- Deep integration of dynamic trust evaluation, ZTA, and the ABAC model: Contextual data (including real-time risk information) is collected through the Policy Information Point (PIP) and integrated into trust evaluation. Minimum authorization is implemented based on the trust level and attribute policies, enabling more fine-grained, flexible, and secure dynamic access control.

- Provision of traceable trusted proof for PDP cluster decision-making in ZTA: An m-of-n threshold signature scheme based on BLS signatures [12,13,14] is introduced into the PDP cluster decision-making process. This ensures that each critical authorization decision takes effect only after being jointly signed by multiple PDP nodes, effectively dispersing trust risks and improving the fault tolerance and accountability of decisions. Thus, the control plane is constructed as a verifiable plane that does not require absolute trust, significantly enhancing the security of the ZTA control plane itself.

2. Related Studies

As a core mechanism for ensuring the security of information systems, access control models have evolved from DAC and MAC to RBAC. However, in highly dynamic cloud environments with ambiguous boundaries, these models all exhibit significant limitations. The DAC model [4] delegates permission management to resource owners. Although it offers flexibility, it is difficult to implement unified security policies, leading to issues such as “permission creep” and inconsistent security policies. For example, the scheme proposed by Kumar et al. [15] retains the rigid security requirements of MAC to a certain extent but adopts DAC in the second stage, which still carries the risk of permission chain diffusion. This may lead to unauthorized access, and the diffusion path is difficult to trace, posing a direct threat to sensitive data. The MAC model [5] enforces access based on system-mandated security labels. While it provides high security guarantees, its policy configuration is extremely rigid, making it difficult to adapt to the frequently changing access requirements of cloud environments and complex multi-tenant scenarios. The model proposed by Nakamura et al. [16] suffers from insufficient dynamism and cannot be effectively adapted to cloud environments. The RBAC model [6] associates permissions with roles, simplifying permission management and finding applications in many scenarios [17]. However, in cloud environments, it faces problems such as “role explosion” and slow response to dynamic permission adjustments, making it difficult to meet the requirements of fine-grained, context-aware access control. Specifically, as the number of cloud platform projects, engineer-project combinations, and resources (e.g., buckets, database instances) increases, the number of roles that need to be created and maintained expands sharply. Meanwhile, permission changes usually require manual operations by administrators. In cloud environments with frequent project terminations and high personnel turnover, delays in manual permission revocation may lead to serious security risks.

In contrast, ABAC [3] makes dynamic decisions based on multi-dimensional attributes (subject, object, environment, and operation) and is theoretically well-suited for cloud environments. In recent years, many scholars have conducted extensive research on the optimization and application of ABAC models. For example, Yang [18] made important contributions to the management of Static Separation of Duty (SoD) in ABAC, providing the first general constraint verification and minimal intervention repair scheme. However, this model relies on static policy snapshots to verify SoD, does not consider dynamic changes in attributes, and the repair scheme only involves one-time policy adjustments, lacking an automatic permission revocation mechanism. Tall et al. [19] proposed a big data security framework based on ABAC by combining Apache Ranger (a distributed policy engine) and Atlas (metadata management). However, this framework requires manual triggering of Atlas label updates, and its policies are based on one-time authorization decisions, making it impossible to automatically shrink permissions and difficult to implement the principle of continuous least privilege. De Oliveira et al. [20] designed an Acute Care Attribute-Based Access Control (AC-ABAC) model for cross-institutional emergency scenarios to achieve fine-grained access control of Electronic Medical Records (EMRs). By introducing timestamp attributes to dynamically adjust permissions, the model improves dynamic adaptability. However, it lacks in-depth context awareness and integration of real-time risk analysis, making it unable to effectively respond to internal threats. Zhonghua et al. [21] optimized the application of traditional ABAC in the Internet of Things (IoT) environment by leveraging the immutability of blockchain and the automation of smart contracts, proposing the SC-ABAC model. However, permission adjustments in this model rely on post-event penalties rather than real-time risk perception and only assume static threats without addressing internal threats or abnormal behavior detection. Alohaly et al. [22] proposed an enhanced ABAC framework that detects internal threats by integrating network deception technology. However, the generation of honeypot attributes relies on offline genetic algorithms, making it impossible to adjust deception strategies in real time. Additionally, permissions cannot be dynamically downgraded after being granted, leading to the risk of permission retention. Chiquito et al. [23] proposed an integrated architecture of ABAC and Attribute-Based Encryption (ABE), which uses the graph policy model of Next-Generation Access Control (NGAC) to implement complex constraints. However, environment attributes (e.g., time/location) are only used for initial authorization, and the model lacks integration of real-time risks such as abnormal login detection. Shahraki et al. [24] proposed the D-ABAC model, which realizes cross-domain attribute verification through Attribute-Based Group Signatures (ABGS) and Zero-Knowledge Proofs (ZKPs), avoiding centralization risks. However, permissions are bound to attribute keys, and there is no continuous verification mechanism during sessions, making it difficult to implement the principle of continuous least privilege. The above analysis indicates that ABAC models still have shortcomings in addressing dynamic changes in user behavior and potential internal threats; relying solely on preconfigured attributes is insufficient to fully reflect the user’s real-time trust level and access intentions.

The dynamic trust-based access control model proposed by Wang et al. [25] can promptly reflect the user’s trust level and adjust permissions dynamically. Kesarwani et al. [26] proposed a machine learning trust model based on fuzzy logic, which dynamically calculates user trust values through machine learning methods to achieve more accurate access control. In the study by Chen et al. [27], direct trust values are obtained from the historical behaviors of cloud users, and recommended trust values are calculated based on interactions between users. Access permissions are adjusted based on the comprehensive trust value derived from these two values, realizing trust-based access control. However, in cloud environments, relying solely on a single trust model may make it difficult to clearly define permission boundaries, leading to users with high trust levels accessing unauthorized resources (e.g., a doctor with the same trust score accessing judicially sensitive data). Trust models embody the concepts of trust evaluation and dynamic authorization in ZTA. By combining ZTA with the ABAC model, the problems identified in related studies can be addressed. However, ZTA is highly dependent on the reliability and security of the PDP (a core component of the control plane). If the PDP is compromised, attackers can arbitrarily authorize unauthorized access, resulting in severe consequences [11]. Traditional schemes [12,28] usually assume that the PDP itself is absolutely trustworthy or only rely on single-point hardening, which poses high risks in actual complex cloud environments.

To address these issues, this study proposes a Zero-Trust Access Control Model based on Attributes and Dynamic Trust Evaluation (AT-ZTAC). The model deeply integrates the zero-trust framework with the ABAC model: after the PIP collects the user’s relevant attributes and contextual data, the trust evaluation module calculates the user’s trust level, which is then incorporated as a key attribute into the ABAC decision-making policy to achieve fine-grained, dynamic, and secure access control. Meanwhile, a BLS-based multi-signature scheme is applied to ensure that access decisions take effect only after being jointly endorsed by multiple PDP nodes, improving the system’s fault tolerance and traceability. Table 1 compares AT-ZTAC with existing access control models.

Table 1.

Comparison of AT-ZTAC with Existing Access Control Models.

3. Design of the AT-ZTAC Model

3.1. Access Control Model

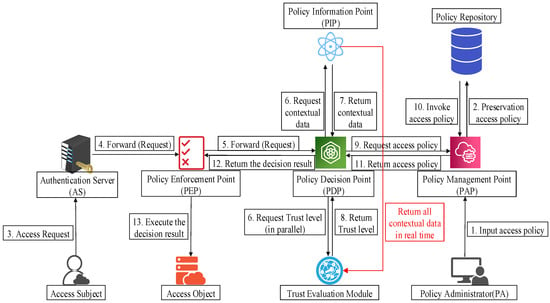

The trust-based access control model (AT-ZTAC) proposed in this paper is shown in Figure 1. This model follows the NIST ZTA standard reference architecture and incorporates key enhancements. Its core idea is to treat the dynamically calculated real-time trust level as a key attribute for ABAC decision-making, thereby transforming static authorization into dynamic authorization linked to trust and permissions.

Figure 1.

AT-ZTAC model diagram.

- The definitions of each element are described as follows:

- (1)

- Access Subject: A user who intends to access cloud services and initiates access control requests. The subject must carry multi-source identity identifiers (e.g., user account, device certificate), environment attributes (e.g., access IP ownership, network environment), and operation attributes (e.g., access time, operation type). This information serves as the basic input for trust evaluation.

- (2)

- Access Object: A collection of cloud resources to be accessed, including system data and executable instructions, and is the target of access requests. The object must be pre-labeled with object attributes such as data sensitivity level (public/internal/confidential), resource type (computing/storage/network), and access permission granularity (read/write/modify/delete). These attributes are linked to the subject’s trust level to determine the final authorization scope.

- (3)

- Trust Evaluation Module: A core component of ZTA that provides continuous trust evaluation for access subjects, object resources, and the system environment through a trust level evaluation algorithm. The resulting trust calculation serves as a key input for access control decisions.

- (4)

- Authentication Server (AS): A service responsible for verifying the authenticity of the access subject’s identity, which serves as the identity benchmark for subsequent trust calculations. It verifies user identity using technologies such as single sign-on (SSO), multi-factor authentication (MFA), biometric identification, and passwords, and verifies user device identity using technologies such as device certificates.

- (5)

- Policy Enforcement Point (PEP): Forwards access requests and enforces access control decisions (e.g., allow, deny, restricted access), while feeding back execution results to the PIP in real time.

- (6)

- Policy Decision Point (PDP): Makes access decisions based on contextual data, trust level, and current access policies. The identity of each PDP node is bound to a hardware root of trust (Trusted Platform Module, TPM).

- (7)

- Policy Administration Point (PAP): A center for creating, storing, distributing, and managing access control policies, which accepts inputs from policy administrators.

- (8)

- Policy Information Point (PIP): Continuously collects and aggregates all attribute information and contextual data related to access decisions from various parts of the system, including user attributes, resource attributes, environment attributes, and real-time behavior data (e.g., traffic, logs). It provides data services for the PDP and the trust evaluation module.

- (9)

- Policy Repository: A database that stores access control policy definitions. The access control policies herein are based not only on attribute information but also integrate trust level indicators. Policies are defined in accordance with the XACML [29] standard, and their core logic can be formally described as a four-tuple model that maps subject attributes, object attributes, environment attributes, and trust level thresholds to access permissions.

- (10)

- Policy Administrator (PA): A personnel with the authority to configure, modify, and manage access control policies in real time.

- The entire access control process is described as follows:

- (1)

- The access subject initiates a cloud resource access request to the AS.

- (2)

- The AS verifies the access subject’s identity using technologies such as SSO. Upon successful authentication, the AS generates a time-stamped identity credential, synchronizes the credential to the PEP and the trust evaluation module, and forwards the access request to the PEP.

- (3)

- The PEP receives the identity credential from the AS, verifies the timeliness and format validity of the credential, and filters out illegal requests with expired or malformed credentials. After initial verification, the PEP encapsulates the access request into a standardized JSON data packet and forwards it to the PDP via the gRPC protocol.

- (4)

- The PDP requests the PIP for attribute information (of the access subject, object, and system environment) and related contextual data, and simultaneously queries the trust evaluation module to obtain the subject’s current trust level.

- (5)

- The PIP collects and returns the contextual data required for access control decisions to the PDP, and continuously transmits the latest contextual data (e.g., access logs, traffic data) to the trust evaluation module.

- (6)

- Based on the data provided by the PIP, the trust evaluation module obtains the user’s trust level through access hot-spot caching or real-time calculation and returns the result to the PDP.

- (7)

- The PDP requests the PAP for a list of access control policies corresponding to the current trust level.

- (8)

- Based on the PDP’s request, the PAP retrieves and invokes relevant access control policies from the policy repository.

- (9)

- The PAP returns the retrieved set of access control policies to the PDP.

- (10)

- The PDP performs policy matching and policy determination based on the contextual data, access policy list, and trust level, returns the access decision result (signed jointly by the PDP cluster) to the PEP, and synchronizes the decision process log to the PIP for storage (for subsequent auditing).

- (11)

- The PEP enforces access control on the access object (e.g., allowing connections, blocking requests, restricting operation permissions) based on the decision result of the PDP cluster, and feeds back the execution result to the PIP.

Traditional trust models typically treat trust evaluation as a mandatory step before access decision-making, creating serial dependency. To address this issue, the trust evaluation module in this model adopts asynchronous computing and hot-spot caching mechanisms. Specifically, trust evaluation is no longer a mandatory pre-step of access decision-making but operates as a parallel background task continuously. This module asynchronously obtains the latest contextual data from the PIP and utilizes hot-spot caching to store recent evaluation results and intermediate calculation factors. In subsequent short-cycle calculations, only rapidly changing factors need updating, thereby providing accurate and efficient trust data support for the next access decision and significantly reducing access request response latency.

3.2. Trust Level Evaluation Algorithm

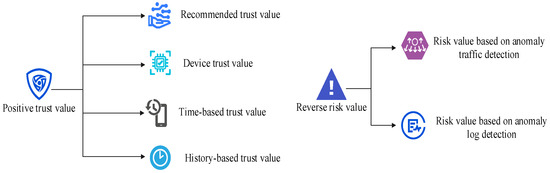

In the access control model proposed in this paper, the access subject’s trust level score is an important basis for access decisions. Contextual data is continuously collected and transmitted by the PIP, and the user’s real-time dynamic trust level is calculated using a trust level evaluation algorithm. As shown in Figure 2, the trust level is determined by both positive trust value and reverse risk value. Positive trust values include recommended trust value, device trust value, time-based trust value, and history-based trust value, which are used to evaluate the trustworthiness of entities. Negative risk values consist of abnormal traffic detection results and abnormal log detection results, which are used to evaluate negative indicators of the system and quantify potential risk factors of the system. Only by comprehensively considering trust and risk factors can trust evaluation be effectively conducted to further guide access control.

Figure 2.

Basis for trust level evaluation.

3.2.1. Calculation of Positive Trust Value

The positive trust value is the weighted sum of the recommended trust value , the device trust value , the time-based trust value , and the history-based trust value , calculated using Formula (1).

where are the corresponding weights, and . represents identity trust values and social relationship data, represents the security of the access terminal, represents compliance with behavioral habits, and represents trust continuity (i.e., evaluation from four different dimensions: identity source, terminal status, behavioral habits, and historical performance), forming a multi-dimensional method for calculating positive trust values.

- Recommended trust value

When a user registers, the system requires the user to provide at least three referees who have registered in the system and have a certain trust level. The recommender gives the initial credit value of the recommended user, and the corresponding weight is related to the recommender’s trust level. The higher the trust level, the greater the corresponding weight. The recommended trust value is calculated using Formula (2).

Here, is the number of recommenders, is the trust level of each recommender, is the initial credit value of the recommended user given by the recommender.

- 2.

- Device trust value

This factor focuses on the credibility of the login device itself and is calculated based on a weighted summation of multiple sub-factors. The calculation method for device trust value is given by Formula (3).

Here, represents the device certificate identifier. It is 1 when the device has an effective and non-expired company certificate; otherwise, it is 0.

represents the IP address reputation. If the login IP belongs to a reputable Internet Service Provider (ISP), it is 1; if it belongs to a known malicious or high-risk pool IP, it is 0; and the intermediate state is 0.5.

represents the trust history. When the device has no risk history, it is 1; when it has a suspicious history, it is 0; and for a newly used device for the first time, it is 0.5.

and

are the weights of the corresponding three sub-factors, and they satisfy

.

- 3.

- Time-based trust value

This factor assesses whether the access time conforms to the user’s normal behavior pattern. It is modeled using the Gaussian function, and the access-time-based trust value is calculated by Formula (4).

Here, represents the current access time, represents the average time of the user’s most frequent access, represents the standard deviation of the time distribution, which determines the tolerance for time deviations. All the units mentioned above are in hours. To prevent this value from being too low in special scenarios, such as emergency duty, it can be manually set in such cases.

- 4.

- History-based trust value

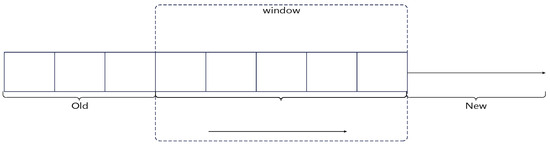

To achieve a continuous assessment of user trust while avoiding undue influence from overly distant historical data on the current state, we introduce a sliding window mechanism. This mechanism only considers user behavior data from the most recent period (i.e., within the window). As time progresses, old data slides out of the window and new data slides in, ensuring the timeliness of the assessment. Furthermore, we add a time decay factor to give higher weight to newer data within the window, further optimizing assessment accuracy. The sliding window model is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Sliding window model.

The history-based trust value is calculated by Formula (5).

Here, represents the number of historical evaluation data represents the number of data in the window, and is the attenuation window function.

Through the attenuation window function , we ensure the system can respond to both long-term trends and recent changes in user behavior, but with a higher weight given to recent behavior and a lower weight to older data. It is calculated using Formula (6).

Here, represents the current time,

represents the system time at the time of the

request determination, and is a time adjustment factor.

3.2.2. Calculation of Reverse Risk Value

Network traffic and system logs record a large amount of network communication activities and system operation information, which contain rich behavioral patterns and anomaly signs. Analysis of network traffic can determine whether a network connection is malicious, while analysis of system logs can determine whether a behavior/operation is compliant. The combination of these two analyses can effectively address major risk scenarios in cloud environments, ensuring that threats—whether from outside the network or inside the system—can be effectively detected. This provides more comprehensive negative risk data for trust evaluation, thereby enabling dynamic adjustment and optimization of access control policies. That is, in this study, the reverse risk value is calculated by weighting the risk value based on anomaly traffic detection and the risk value based on anomaly log detection using Formula (7).

Here,

represent the corresponding weights, and

.

- Risk value based on anomaly traffic detection

This metric measures the degree of anomaly in user access traffic, such as traffic spikes, malicious payloads, etc., calculated by sliding Windows and time decay using Formula (8).

Here, represents the risk value of the flow detection, with a higher risk value corresponding to a closer proximity to 1, represents the traffic risk time decay function, and indicates the sliding window size of the flow risk.

The traffic risk time decay function is calculated using Formula (9).

Here, represents the current time, represents the system time at the time of the request determination, and is the traffic risk time adjustment factor.

- 2.

- Risk value based on anomaly log detection

This metric measures risky behaviors in the user operation log, such as abnormal commands, attempts to get out of bounds, etc., calculated by sliding window and time decay using Formula (10).

Here, represents the risk value of the log detection, with a higher risk value corresponding to a closer proximity to 1, represents the log risk time decay function, and indicates the sliding window size of the log risk.

The log risk time decay function is calculated using Formula (11).

Here, represents the current time, represents the system time at the time of the request determination, and is the log risk time adjustment factor.

This study focuses on constructing a dynamic trust evaluation framework that integrates these risk indicators, rather than designing new detection algorithms. The values of and in the negative risk value can be obtained by integrating existing mature abnormal traffic and abnormal log detection schemes. In a specific implementation, it is only necessary to normalize the output of the selected detection scheme to a risk value in the [0, 1] interval.

3.2.3. Trust Level Calculation

Trust level is an important basis for PDP to make access decisions, derived from the combined positive trust value and reverse risk value mentioned above. To ensure that high-risk events significantly and reasonably reduce the trust level, a multiplicative model is used for calculation. The method is as shown in Formula (12).

Here, as the trust discount factor, when the reverse risk value is 0, the trust level is equal to the positive trust value, and when the reverse risk value is 1, the trust level is 0, regardless of the user’s positive trust value.

3.2.4. Weighting Determination Method-Combined Weighting Method

The above-mentioned scheme involves multiple weight distribution issues. To reasonably determine the weights of each factor, the combined weighting method was adopted in the study. The method first uses the AHP method [30] to determine the subjective weights based on the experience of security experts, then uses the entropy weight method [31] to determine the objective weights based on the actual data distribution, and finally combines the two, considering both domain knowledge and respecting the characteristics of the data itself, to achieve a more scientific and reasonable weight distribution.

- Subjective weights are determined by the AHP method

AHP combines quantitative analysis with qualitative analysis. The main idea is to build a judgment matrix by comparing the importance of each pair of factors, then calculate the maximum eigenvalue of the judgment matrix and the corresponding eigenvector and unite them to obtain the corresponding weight.

First, pairwise comparisons of the importance of the indicators are made, and qualitative language is converted into quantitative values through the 1–9 basic scale method, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

1–9 Basic Scaling Method.

The decision factor judgment matrix A can be obtained with the help of Table 2.

Here, represents the importance scale of factor relative to factor .

Calculate the maximum eigenvalue of the above judgment matrix and obtain the characteristic Equation (14).

The eigenvector is obtained through the solution. The vector is normalized, which results in the weights of each element.

However, in practice, solving for is often very difficult. Therefore, an approximate calculation method is adopted, as shown in Formula (15).

The values of obtained through the solution are the weights of each element.

Since the judgment matrix is given subjectively, there may be logical inconsistencies. Therefore, the degree of consistency must be tested, and the test steps are as follows.

- (1)

- Calculate the consistency index , where .

- (2)

- Find the corresponding average random consistency index . Table 3 lists some of the values corresponding to n.

Table 3. Average Random Consistency Indicator RI (Part).

Table 3. Average Random Consistency Indicator RI (Part). - (3)

- Calculate the consistency ratio , . When , it is considered that the consistency of the judgment matrix is acceptable; otherwise, the judgment matrix needs to be manually adjusted until .

- 2.

- Determine the objective weights using the entropy weight method

Entropy weighting is an objective weighting method that relies solely on the discreteness of the data itself. The stronger the discreteness, the greater the decision contribution of the indicator and the higher the weight.

For samples and evaluation elements, represents the value of the element of the sample.

Normalize the data first, and for the positive element, calculate using Formula (16).

The calculation method for negative elements is Formula (17).

Calculate the entropy value of the element:

Here, .

Calculating information entropy redundancy:

Then the calculation methods for the weights of each element are shown in Formula (20).

The final combined weight w is calculated as shown in Formula (21).

To achieve the highest degree of discrimination, the value that maximizes the variance of the final score is usually selected as the optimal ratio. However, can also be constrained as needed to ensure the subjective weights, such as .

3.3. PDP Cluster Decision Co-Endorsement Scheme

In the zero-trust architecture, the PDP is the core component of access control, and its security directly determines the security of the entire system. The security enhancement of the PDP cluster in our scheme fundamentally relies on the algebraic property of symmetry, as realized through bilinear pairings in cryptography. Traditional single-PDP architectures suffer from an asymmetry in trust: the PDP is unconditionally trusted to make correct decisions, while other components are not. This creates a critical security vulnerability. Our model introduces symmetry by distributing the trust and decision-making power across multiple PDP nodes. The core enabler of this symmetrical design is the BLS signature scheme and its utilization of a bilinear map.

3.3.1. Foundation of BLS Signatures

Based on the discrete logarithm problem, BLS signatures define a bilinear mapping function e in three cyclic groups (G1, G2, G3) of order p:

The bilinear mapping function e must satisfy:

Here, represents any element of group G1, represents any element of group G2, and represents any integer.

The symmetry shown in Equation (23) is crucial. It allows any verifier to check the validity of a signature aggregated from m of n signers using a single, constant-time pairing operation, without needing to know the individual signers or their signatures. This computational symmetry is precisely what makes our threshold scheme both efficient and suitable for high-throughput cloud environments. Therefore, the concept of symmetry transitions from a cryptographic primitive to an architectural principle, ensuring a balance between security, decentralization, and performance.

3.3.2. Scheme Implementation

Standard BLS aggregate signatures do not distinguish between signers. To enable traceability of data signatures—i.e., to accurately identify the signatory proxy nodes for rapid localization and replacement in case of dishonest proxy nodes—the signer ID corresponding to the proxy node is introduced in this paper. The specific signature method is as follows:

In the PDP cluster, there are n policy signatories, denoted as set . Each signatory holds the private key and the public key , and is the generator of the cyclic group. The scheme employs the digital hash function h(x) and the curve hash function H(x), and sets the threshold value m, meaning that at least m signatories are required to sign the decision result for it to be valid.

The aggregated public key PK is:

where is the corresponding coefficient, determined by the following formula:

The unique for each signer is generated using Formula (26):

The message contains the aggregate public key PK and ID information i, i.e., represents a valid signature of all signers on message . In this case, Formula (27) holds:

Suppose that k signatories have successfully signed decision l. For ease of expression, let us denote this set as where each individual signatory corresponds to the signature

This is referred to as a member signature:

By summing the above member signatures, the multi-signature (signature of the set of signers who signed decision l)

and the corresponding set public key

of the signers are obtained. The calculation is shown in Formula (29):

3.3.3. Scheme Verification

The verifier has knowledge of the message l, aggregate signature , set public key of the signers , aggregate public key PK, and the IDs of the signers in the signer set. The verification is performed as follows:

If the equation holds, the subscripts corresponding to set A can be used to prove which k signers signed the decision. This is because:

Therefore, through the above BLS signature scheme with signer IDs, it is possible to determine which proxy nodes signed each piece of data and whether the number of signers meets the signature requirement (k > m). This achieves the goal of ensuring the security of each piece of data by accumulating signatures from a majority of PDP policy signers.

4. Safety Analysis

AT-ZTAC, through multi-dimensional design, fully covers the core security requirements of zero-trust access control in cloud environments:

Control Plane Security: BLS threshold signature for fault tolerance against the risk of a single point of failure in PDP clusters.

Dynamic risk defense: Dynamic trust assessment responds in real-time to internal threats and identity theft.

Dynamic privilege control: The binding of permissions to the trust level, combined with session-level continuous verification, collectively achieves the principle of least privilege.

Resilience: ECDLP Difficulty and TPM binding against forgery and Sybil attacks;

Accountability: Node number binding supports anomaly tracing.

The following is a systematic analysis of its security in combination with model design details and cryptographic security assumptions.

4.1. Control Plane Security

The core security vulnerability of the zero-trust architecture lies in its assumption of absolute trust towards the control plane (especially the PDP). Once the authorization decision made by the PDP is forged, the entire access control system will fail. Therefore, AT-ZTAC adopts a threshold signature scheme based on BLS, converting the decision into a collective decision endorsed by the PDP cluster. Its security relies on the following design:

- Threshold fault-tolerance mechanism

Suppose the PDP cluster consists of n signing nodes and the threshold value is m, meaning that the decision can only take effect when at least m nodes sign it. If an attacker takes control of nodes, since they cannot forge the private key signatures of the remaining honest nodes, the generated false decision will fail to pass the verification, and the system can still operate normally. Moreover, compared with the scheme that requires signatures from all nodes, this scheme can avoid the situation where the attacker controls a small number of nodes to refuse signatures and thereby hinder the normal decision-making process. This design is significantly superior to the traditional single PDP scheme and other schemes in terms of fault tolerance and availability.

- 2.

- BLS Signature’s Cryptographic Security Foundation

The security of the BLS signature is based on the computational difficulty of the Elliptic Curve Discrete Logarithm Problem (ECDLP): in a cyclic group G1 of order , given the base point and the point (where x is the private key), it is impossible to solve for x within polynomial time. In the model, the private key of each PDP node is randomly generated, and the public key is used. The verification of the aggregated signature relies on the bilinear mapping . If an attacker attempts to forge a signature, they need to crack the ECDLP to obtain the node’s private key or construct a false signature that satisfies the bilinear mapping. However, this is not feasible under the computational security assumption (i.e., the attacker’s computing power is limited).

4.2. Dynamic Risk Defense

Traditional ABAC models rely on static attribute authorization and are unable to deal with risks such as stolen credentials or unauthorized access by internal users to sensitive data. The dynamic trust assessment module of AT-ZTAC achieves real-time risk response through multi-dimensional trust and risk quantification, with specific security guarantees as follows:

- Anti-circumvention of multi-source trust factors

Positive trust value builds a user’s trusted profile from four dimensions: identity security, device security, behavioral habits, and historical records, and a single dimension cannot be easily tampered with.

- 2.

- Real-time detection capabilities for reverse risks

Reverse risk value, through sliding Windows and time decay mechanisms, can capture sudden changes in user behavior in real-time through abnormal traffic detection and abnormal log detection, such as high-frequency scanning, oversized payload transmission, permission out-of-bounds attempts, deletion of audit logs, and other malicious behaviors. Setting a corresponding risk value for malicious behavior can dynamically adjust the final trust level and achieve real-time wind direction response.

4.3. Dynamic Permission Control

The zero-trust “continuous minimum privilege” principle is difficult to implement in traditional ABAC because static authorization cannot be dynamically adjusted according to the user’s trusted status. In addition, traditional ABAC can lead to policy conflicts and inconsistencies as systems grow in size and complexity. AT-ZTAC achieves real-time contraction and expansion of permissions by binding access rights to a dynamic trust level, and constraining possible policy conflicts to trust level intervals, and its security is reflected in:

- Strong association between permissions and trust level

The scheme divides trust level into multiple consecutive intervals, each of which maps to a different set of permissions, so the range of permissions granted automatically adjusts with the change in trust level, not only achieving dynamic management of permissions, but also effectively limiting the range of policy conflicts and improving the policy consistency of the system.

- 2.

- Session-level continuous validation

Traditional ABacs typically perform one-time validation of attributes at the initial stage of access and do not re-evaluate them during the session. The AT-ZTAC’s PDP periodically reacquires user context data via PIP during session duration, invokes the trust evaluation module to update the trust level, and synchronously adjusts permissions. For example, when a batch of data downloads is suddenly initiated during a user session, the reverse risk value rises, the trust level drops, and the PDP adjusts permissions based on the latest policy without waiting for the session to end.

4.4. Resistance to Attacks

In response to common attack methods in the cloud environment such as “signature forgery” and “sycophant attack” (where attackers forge the identities of multiple PDP nodes), AT-ZTAC forms a defense through cryptographic mechanisms and architecture design:

- Resistant to signature forgery

To forge a valid aggregated signature , the attacker must at least be able to forge the member signature of a legitimate node; otherwise, it cannot pass the verification of . If the attacker attempts to forge the member signature of a certain legitimate node, then at least they need to solve (given ), which is the ECDLP difficult problem and is not feasible under the computational security assumption.

- 2.

- Resistance to Sybil attacks

The core of a Sybil attack is to forge multiple node identities to meet the threshold m. In AT-ZTAC, the identity of each PDP node is bound through the TPM, and when a node joins the cluster, it has to submit the device certificate generated by the TPM, which is verified by the AS for legitimacy. Attackers cannot forge TPM certificates and thus cannot create fake PDP nodes, ensuring that all n nodes in the cluster are real and authenticated entities, effectively defending against Sybil attacks at the system architecture level.

4.5. Accountability

AT-ZTAC enables full traceability of decisions through the “node number binding” design of BLS signatures:

The node number is bound to the signature by Equations (25) and (26), so the aggregated signature is generated with the corresponding node number and the corresponding aggregated public key. When an abnormal decision is detected, the corresponding node number i can be obtained by combining the corresponding aggregated public key and the personal public keys held by all members (only the correct permutation and combination can generate a matching aggregated public key), thereby achieving the purpose of holding the signer accountable who signed the abnormal decision.

4.6. Formalize Security Verification

To further validate model security, formal security verification of the security of the BLS scheme used in the control plane of AT-ZTAC:

Definition 1.

Multi-signature security: In a game, if an attacker with the maximum attack resources is still unable to complete the minimum attack target task, then the BLS multi-signature scheme is considered secure.

Definition 2.

Breaking BLS multi-signature: In the random oracle model, for a security parameter, there is a set of n signers

. The attacker A can control k of these signers. The internal attacker A can adaptively choose adaptive messages at will. Within polynomial time t, the challenger C can initiate at most Hash inquiries and signature queries. If the attacker A can win the above game with a probability of , then it is said that the attacker A can break the BLS multi-signature scheme with . Otherwise, it is said that the BLS multi-signature scheme has unforgeability under the adaptive message selection attack of the internal attacker A in , and is considered to be EUF-CMA secure.

Theorem 1.

The lightweight aggregated signature BLS scheme is secure under the adaptive message attack aaa by the internal attacker A.

Proof of Theorem 1.

Assume that attacker A has the largest attack resources and can control internal signers. Then, based on the structure of the signature scheme (29), attacker A can create a collective signature of signers and verify it through Equation (30). To achieve the minimum attack goal, the attacker must be able to successfully forge the individual signature of any signer, that is, the member signature , as indicated by Equation (28). It is assumed that the attacker wants to forge the member signatures of the honest signer . Since the attacker has the largest attack resources, it is assumed that and can be obtained through signature queries. The signatures of all other signers can be obtained through signature queries. The generator of the cyclic group is . The security of this BLS scheme can be reduced to the ECDLP. □

Let H be a random oracle, and if is a gap group and is a universal hash function, then the lightweight aggregate signature BLS scheme is EUF-CMA secure.

Specifically, suppose there exists an EUF-CMA adversary A that breaks the lightweight aggregate signature BLS scheme with a advantage. A can make at most queries to H and at most queries to the signature, then there must exist a challenger C that solves the ECDLP at least with a advantage, where e is a natural constant.

- ①

- Initialization

Challenger C runs the initialization algorithm, generating three p-factorial cyclic groups G1, G2, and G3, as well as a bilinear mapping function . Then, the generated system parameters are sent to the attacker A.

- ②

- Signature query-response

Extracting private key query: Challenger C records the private key values of each signer in the list . The attacker A inputs the signer . If , then C randomly selects the private key , calculates the public key , and then records to the list , and returns to A. If , then C sets and records to the list , and returns an empty value to A.

H query: Challenger C uses the list to record the query values. The attacker A inputs the information . Challenger C randomly selects . If , return . If , then C queries the list , if there is a corresponding record , then return to the attacker A; otherwise, C randomly selects , calculates , and then records to the list , and returns to the attacker A.

Querying the aggregated public key and numbered signature : Challenger C uses the list to record the signature results of each signer for the aggregated public key and numbered signature. The attacker A inputs the signer and the aggregated public key PK, queries the signature of signer for the aggregated public key and the numbered. If there is a corresponding record , then return to the attacker A; if there is no corresponding record, then C randomly selects , which satisfies , and then records to the list , and returns to the attacker A.

Member signature query: Challenger C uses the list to record the member signature results of user . The attacker A inputs user , information , and the numbered signature , queries for the signature of information . When , C queries the in the table, the in the table, and the in the table to calculate the member for the message and the member signature , and returns to the attacker A. When , exit the member signature query and return failure.

- ③

- Output signature (forged signature)

For the signature set , the information , attacker A outputs a forged multiple signature result . If the above inquiry process does not terminate, user ’s private key has not been submitted to the private key query list, and has not undergone partial signature inquiry, and the multiple signature result is valid. Then attacker A wins in the game, that is, and satisfy Equation (31):

Then, the challenger C can calculate the partial signature result of by querying the records in the list and the valid multiple signature result of the attacker A, as shown in Formula (32):

It is also known from the partial signature formula that:

By querying the list

the challenger C can calculate

as shown in Formula (34):

That is, C successfully resolves the given ECDLP instance.

For simplicity and without loss of generality, assume:

- (a)

- A will not make the same inquiry twice to ;

- (b)

- If A requests a signature for message l, then it has already inquired about before;

- (c)

- If A outputs , then it has already been inquired about before.

The success of C is determined by the following three events.

E1: C does not interrupt during A’s signature inquiry;

E2: A generates a valid message signature for ;

E3: E2 occurs and has subscript .

, and . Therefore, the advantage of C is .

Therefore, if attacker A can break the BLS multi-signature scheme with a significant advantage within polynomial time, then challenger C can solve the ECDLP with a significant advantage within polynomial time by leveraging A’s capabilities. However, solving the ECDLP is difficult, so in the random oracle model, there cannot exist such an attacker A who can break the BLS multi-signature scheme within polynomial time. In this security model, an attacker can obtain through inquiries. In fact, the security of can also be reduced to the ECDLP, meaning that cannot be forged or broken by the attacker either. This further proves the security of this scheme.

5. Experiments and Performance Evaluation

5.1. Experimental Setup

To verify the effectiveness of the AT-ZTAC model in cloud environments, this study built a simulated cloud experimental platform. The relevant environment configurations are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Experimental Environment Configuration.

Taking the traditional RBAC model [6], traditional ABAC model [3], dynamic trust evaluation model [25], machine learning trust model [26], history-based behavior trust model [27], and context-aware trust model [32] as controls, the core parameter configurations of this model are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

AT-ZTAC Core Parameter Settings.

Most of the above parameters are calculated by the system using the combined weighting method, and a small number are manually set hyperparameters. Among them, the sliding window size and time decay factor have the most significant impact on the experiment. In addition to the above parameter settings, the anomaly detection methods adopt those proposed in [33,34], both of which have real-time performance and certain robustness.

Experiments were conducted from three dimensions: trust evaluation effectiveness, access decision performance, and access control accuracy. All experimental data are the average values of three repeated tests. Additional ablation experiments and hyperparameter sensitivity experiments were conducted to ensure the reliability of the results.

5.2. Analysis of Trust Evaluation Effectiveness

Trust evaluation is the core of AT-ZTAC’s dynamic authorization. This section verifies the effectiveness of the model’s trust evaluation by simulating scenarios such as users’ first access, various typical attacks, continuous normal access, and sudden abnormal operations, combined with trust level distribution and response speed. The results all show advantages.

5.2.1. Trust Level Distribution for Users’ First Access

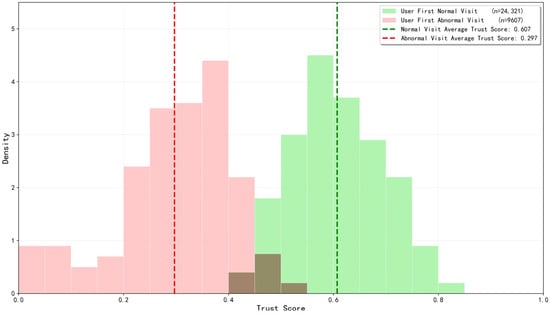

Experimental Scenario: Simulate a new user initiating a cloud resource access request for the first time, including 24,321 normal accesses and 9607 abnormal accesses. The system calculates the trust level based on Formula (12). To better align with the practical logic of “assigning higher initial trust to low-risk behaviors”, the recommended trust value for normal access is set to 0.8, and that for abnormal access is set to 0.3. The device attributes are uniformly set to have valid enterprise certificates, IP addresses belonging to reputable ISPs, and no historical records. The experimental results are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Distribution of first visit trust level of users under the AT-ZTAC model.

As shown in Figure 4, the trust level of users’ first normal access ranges from 0.4 to 0.85, with an average of 0.607. Under the trust level evaluation algorithm, this distribution not only avoids permission overflow risks caused by excessively high initial trust (e.g., directly assigning a trust level above 0.8 may lead to privilege escalation risks) but also prevents insufficient authorization due to excessive conservatism (e.g., fixed trust levels cannot meet the diverse needs of different users), leaving reasonable room for subsequent dynamic adjustments. The trust level of users’ first abnormal access ranges from 0.0 to 0.55, with an average of 0.297. Through the multiplicative inhibition effect of the reverse risk value, the model can significantly reduce the trust level of high-risk access, ensuring security guarantees for the first access. The differentiation and concentration of the above distribution initially indicate that the trust evaluation module in the AT-ZTAC model can well distinguish users’ access intentions and assign relatively reasonable trust levels.

5.2.2. Trust Level and Access Control Results Under Attacks

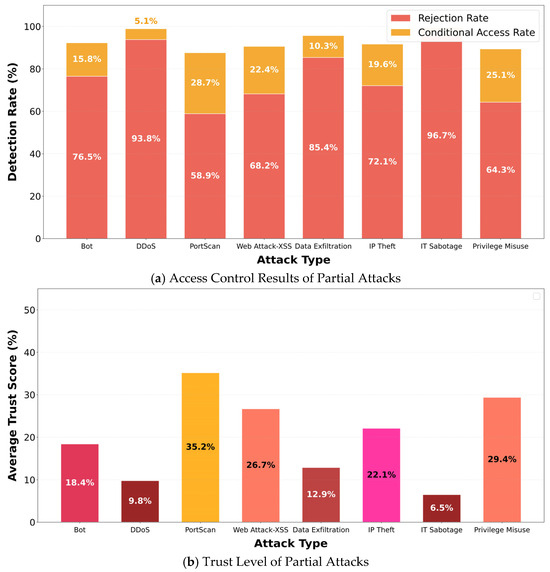

Experimental Scenario: Eight types of typical attacks were simulated in the cloud environment, each lasting 10 min. The access decision results and corresponding average trust levels for each attack were recorded. To ensure the authenticity, reproducibility, and comparability of the experiment, this study used two widely recognized public datasets as the basis: the CIC-IDS-2017 dataset from the Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity and the CERT Insider Threat Dataset v4.2 from the Software Engineering Institute of Carnegie Mellon University. The former includes 14 modern network traffic attack scenarios and records more than 2.8 million traffic records, while the latter has rich log types, highly matching the audit logs in cloud environments, and provides typical cases for internal threats in cloud environments. On this basis, simulated experimental data conforming to cloud environment characteristics were constructed. For example, for DDoS attacks, the hping3 tool was used to simulate TCP SYN flood attacks to reproduce high-concurrency connection characteristics; privilege abuse was simulated by automatically executing sudo privilege commands and accessing restricted system files. All attacks were configured in accordance with the attack intensity, duration, and target selection patterns observed in the CIC-IDS-2017 and CERT Insider Threat Dataset v4.2, ensuring that the generated attacks are highly similar to the original datasets in terms of statistical characteristics. The final experimental results are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The results of the attack on access control and the corresponding trust levels.

As shown in Figure 5, the trust level of AT-ZTAC is negatively correlated with attack severity—the higher the attack severity, the lower the average trust level and the higher the rejection rate. For attacks with lower severity, the average trust level is relatively higher, and the proportion of conditional access rate and allowed access rate (1—rejection rate—conditional access rate) increases, achieving accurate matching of risk level—trust level—access control. This result indicates that AT-ZTAC can quantify attack threats in real time through reverse risk values, dynamically adjust trust levels and access policies, and avoid security redundancy or insufficient protection caused by “one-size-fits-all” defense.

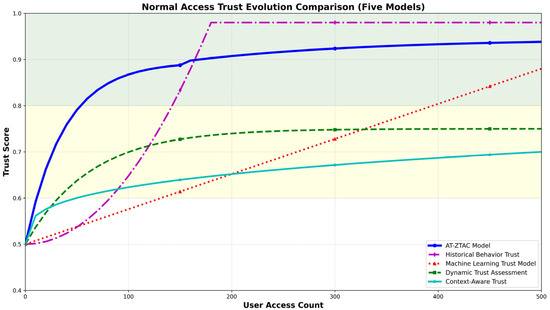

5.2.3. Trust Level Changes During Users’ Continuous Normal Access

Experimental Scenario: Simulate 500 consecutive normal accesses by a user, set the initial trust level to 0.5, and compare the trust level change trends with those of typical trust models. The experimental results are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Changes in trust level when users continue to access normally.

As shown in Figure 6, with users’ continuous normal access, the trust levels of all models increase steadily, but there are also certain differences. Among them, the context-aware model and dynamic trust evaluation model can reach stability relatively quickly, but their trust levels are only around 0.7 after stabilization, which may lead to insufficient authorization. The trust level of the machine learning trust model increases indefinitely with the number of accesses and does not enter a stable stage for a long time, indicating poor responsiveness and insufficient timeliness of the model. The history-based behavior trust model grows slowly in the early stage and accelerates in the later stage, indicating that it fails to effectively filter the interference of distant data. Meanwhile, its trust level exceeds 0.95 after stabilization, posing a risk of over-authorization. The AT-ZTAC model studied in this paper can quickly reach stability within a reasonable range, avoiding the over-authorization risk caused by high trust levels and the insufficient authorization problem caused by low trust levels.

5.2.4. Trust Level Changes When Users Suddenly Perform Abnormal Operations

Experimental Scenario: On the basis of continuous normal access, simulate a user initiating a DDoS attack during the 200th access, and record the trust level changes in each model. The results are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Changes in trust level after abnormal user access.

As shown in Figure 7, AT-ZTAC’s response speed to abnormal behaviors and risk suppression effect are significantly better than those of other models: when an attack occurs, the trust level of the AT-ZTAC model drops by approximately 0.7, which is more than 40% higher than that of the dynamic trust evaluation model (approximately 0.5) and the machine learning trust model (approximately 0.4), and also significantly higher than that of other models, enabling rapid response to malicious attacks. During subsequent normal access, the trust level of AT-ZTAC rebounds slowly and reasonably. Through the design of time windows for device trust value, history-based trust value, and reverse risk value, it avoids secondary risks that may be caused by the rapid trust level rebound of the context-aware trust model, and also prevents insufficient authorization caused by the long-term low trust level of the history-based behavior trust model.

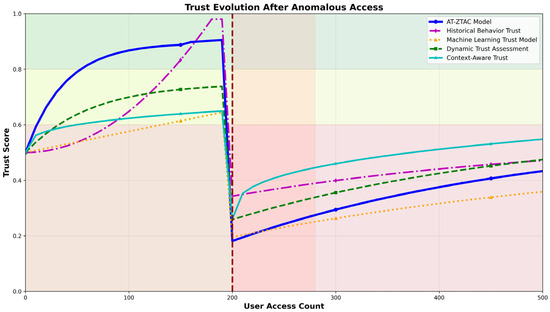

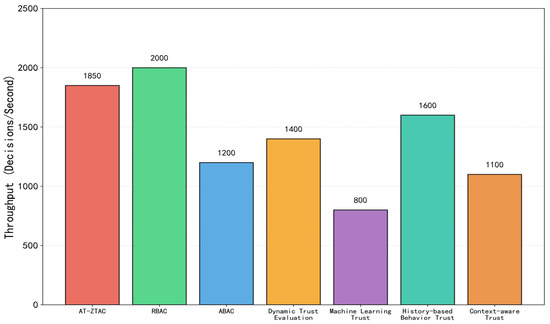

5.3. Access Decision Performance Evaluation

Access decision performance directly affects the user experience and concurrent bearing capacity of cloud environments. This section evaluates the performance of AT-ZTAC after introducing the trust evaluation module and BLS threshold signature mechanism through throughput (the number of access decisions completed per unit time).

Experimental scenario: Simulate concurrent access requests increasing from 500 req/s to 2500 req/s, and measure the throughput of each model. The comparison results are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Comparison Chart of access decision throughput for each model.

As shown in Figure 8, the maximum access decision throughput of AT-ZTAC reaches 1850 req/s, which is a 54% increase compared to traditional ABAC (1200 req/s). The core reason is that the BLS aggregate signature simplifies the verification of multi-node signatures into a single verification. Moreover, since the trust score is incorporated into the ABAC decision policy as a key attribute, the policy retrieval range is limited to a specific trust threshold interval, reducing the decision space. Compared with the dynamic trust evaluation model (1400 req/s) and the context-aware trust model (1100 req/s), the throughput of AT-ZTAC has increased by 32% and 68%, respectively. The core reason is that the trust evaluation module in AT-ZTAC adopts asynchronous computing and hot-spot caching technologies, which effectively reduce performance loss and can meet the high-concurrency access requirements of cloud environments. However, the other two models still use a serial evaluation method: they only perform trust calculation after receiving a request and make access decisions only after the calculation is completed. When trust evaluation takes a long time, it will significantly increase the access response time. In addition, the AT-ZTAC model also has certain advantages over the history-based behavior trust model (1600 req/s), which may be due to the sliding window mechanism it adopts, which weakens the impact of distant data on the current evaluation and reduces computational overhead. The machine learning trust model has the lowest throughput (only 800 req/s), which is related to the large computational time consumption caused by its complex model. The traditional RBAC model has the highest throughput (2000 req/s) due to its simple policy structure, but RBAC has obvious deficiencies in dynamic access control and security, and cannot achieve accurate and adaptive decision-making capabilities.

To verify the statistical significance of the throughput advantage, a one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to test the overall differences among the models. The calculated result was F = 1246.38, p < 0.001, indicating that there were extremely significant overall differences in throughput among the seven models, excluding the possibility of inter-group differences caused by random fluctuations. To clarify the specific differences between AT-ZTAC and each comparative model, a Tukey HSD post hoc multiple comparison test was further used, with the results shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Throughput Tukey HSD Test Results.

As shown in Table 6, the throughput of AT-ZTAC is significantly higher than all comparative models except traditional RBAC, and the differences in throughput compared to all comparative models reached an extremely significant level (p < 0.001). This proves that the performance gain of the asynchronous computing + hot-spot caching mechanism in high-load scenarios is effective and statistically significant, and not a random result.

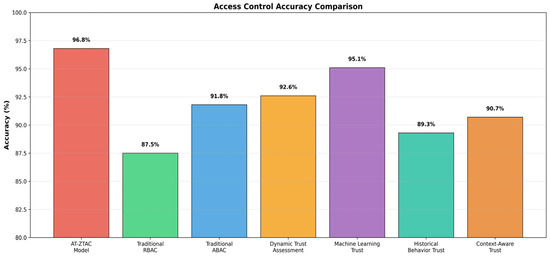

5.4. Access Control Accuracy Evaluation

Access control accuracy is a core metric for ensuring the security and reliability of a cloud environment, directly related to whether the system can effectively block unauthorized access and ensure the normal use of legitimate users.

Experimental scenario: Inject mixed access request streams (a total of 10,000, including 80% normal access and 20% malicious access), calculate the accuracy of each model, and the results are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Comparison of access control accuracy.

As shown in Figure 9, the access control rate of the AT-ZTAC model is 96.8%, significantly higher than that of other models (the control rate of the traditional RBAC model is 87.5%, the control rate of the traditional ABAC model is 91.8%, the control rate of the dynamic trust evaluation model is 92.6%, the control rate of the machine learning trust model is 95.1%, the control rate of the historical behavior-based trust model is 89.3%, and the control rate of the context-aware trust model is 90.7%). The core advantage lies in the deep integration of dynamic trust scores and attribute policies: quantifying real-time user status through trust level, accurately distinguishing low-risk anomalies from high-risk malicious behaviors, avoiding false positives or missed judgments caused by rough static attribute judgments in traditional models, and further improving decision-making accuracy through the BLS multi-signature endorsement mechanism.

To verify the statistical significance of the accuracy rate differences, McNemar’s test (a paired binomial test) was used to compare the classification results of AT-ZTAC and each comparative model on the 10,000 samples. The results are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Significance Test for Access Control Accuracy Differences (McNemar’s Test).

As shown in Table 7, the p-values for all comparison combinations are <0.001, reaching the “extremely significant” standard in statistics. This indicates that the access control accuracy of AT-ZTAC (96.8%) is significantly higher than that of traditional RBAC, ABAC, and various trust-based models. This advantage is not caused by random error but is a systematic result of its integrated design of “dynamic trust evaluation + ABAC attribute policies + BLS multi-signature endorsement”, with strong statistical reliability. Furthermore, the χ2 values for all comparison combinations are far above the critical threshold for significant difference (χ20.001 = 10.83), further verifying that even small accuracy improvements possess rigorous statistical significance.

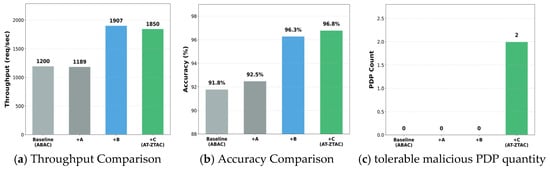

5.5. Ablation Experiment Analysis

To verify the effectiveness of each improved component in the AT-ZTAC model, this study designed a systematic ablation experiment. The improved parts of the model were decomposed into three key components for step-by-step verification:

- Component A: Zero Trust Architecture with the Trust Evaluation Module Removed

- Component B: Trust Evaluation Module

- Component C: BLS Threshold Signature

Figure 10 shows the performance changes when adding each component step by step, starting from the ABAC baseline model.

Figure 10.

AT-ZTAC ablation experiment results.

As shown in Figure 10, in terms of throughput, the throughput of the baseline ABAC is 1200 req/s; after adding Component A, the throughput drops to 1189 req/s. This is because Component A adds continuous identity verification compared to the baseline model. Although it only calculates changed attributes, there is still a small additional overhead, leading to a slight performance loss. After adding Component B, the throughput jumps to 1907 req/s (a 59% increase compared to the baseline). The core reason is that the addition of Component B reduces the policy search range to the trust value interval. At the same time, the adoption of asynchronous computing and hot-spot caching mechanisms decouples the serial dependence between trust evaluation and access decision-making, avoiding the performance bottleneck of real-time trust value calculation. After further adding Component C, the throughput drops to 1850 req/s (still a 54% increase compared to the baseline). The aggregation feature of the BLS signature simplifies multi-signature verification into a single operation, effectively controlling performance loss, but a multi-node signature still incurs slight computational overhead. In terms of accuracy, the accuracy of the baseline ABAC is 91.8%; after adding Component A, the accuracy increases to 92.5%, indicating that the continuous verification of zero trust can initially filter dynamic risks. After adding Component B, the accuracy significantly increases to 96.3% (a 4.5% increase compared to the baseline). The key lies in that Component B quantifies users’ real-time status through positive trust values and reverse risk values, accurately distinguishing legitimate access from malicious behaviors, and solving the misjudgment problem of static attributes in traditional ABAC. After adding Component C, the accuracy further increases to 96.8%, because the BLS threshold signature requires joint endorsement of decisions by multiple PDP nodes, reducing incorrect authorization caused by single-node failures or tampering. This proves that Component B is the core for improving accuracy, and Component C further enhances decision reliability. In terms of tolerable malicious PDP quantity, the baseline ABAC (single-PDP architecture) cannot tolerate malicious nodes (the system fails after being compromised); after adding Component A or B, the tolerable quantity does not change, as neither involves the fault-tolerance design of the control plane. After adding Component C, the number of tolerable malicious nodes increases to 2, indicating that the threshold signature scheme of Component C effectively disperses the trust risk of the control plane and significantly improves the system’s fault-tolerance capability.

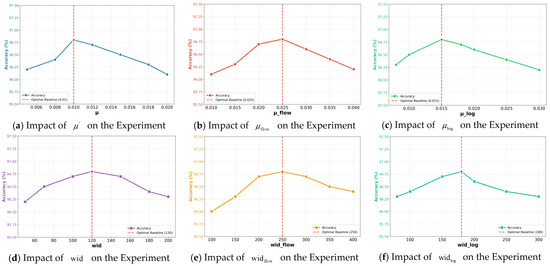

5.6. Hyperparameter Sensitivity Experiment Analysis

The control variable method (with other variables set to optimal values) was used to analyze the impact of key hyperparameters (time adjustment factors , , ; sliding window sizes , , ) in the AT-ZTAC model on experimental accuracy, verifying the model’s robustness. The results are shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Results of hyperparameter sensitivity experiments.

As shown in Figure 11, the optimal values and robustness characteristics of the key hyperparameters of the AT-ZTAC model are clear: the optimal baselines of the time adjustment factor for history-based trust value (), time adjustment factor for traffic risk (), and time adjustment factor for log risk () are 0.01, 0.025, and 0.015, respectively; the optimal baselines of the window size for history-based trust value (), window size for traffic risk (), and window size for log risk () are 120, 250, and 180, respectively. At this time, the model’s accuracy reaches its highest. When each parameter is within the corresponding reasonable range (ranges from 0.005 to 0.02, ranges from 0.01 to 0.04, ranges from 0.008 to 0.03, ranges from 50 to 200, ranges from 100 to 400, ranges from 80 to 300), the accuracy can be maintained above 96%. Even if the parameters deviate from the optimal values, the maximum accuracy drop is no more than 0.8%, fully proving that the model has low sensitivity to hyperparameter changes and strong robustness.

6. Conclusions

To address the shortcomings of traditional access control models in cloud environments, such as insufficient dynamic adaptability, weak risk response capabilities, and poor control plane security, this paper proposes a zero-trust access control model (AT-ZTAC) that integrates dynamic trust evaluation and BLS threshold signature. The model calculates users’ trust levels in real time and incorporates them as key attributes into ABAC policies, realizing fine-grained and dynamic permission management. By introducing a BLS-based threshold signature mechanism, it effectively disperses the trust risk of the control plane and improves the system’s fault tolerance and accountability. Experimental results show that AT-ZTAC significantly outperforms traditional ABAC, dynamic trust evaluation models, and other comparison schemes in terms of trust evaluation effectiveness, access decision throughput, and control accuracy, verifying its application potential in cloud environments. The model can not only quickly respond to abnormal behaviors and dynamically adjust permissions but also maintain good system performance while ensuring high security. However, the current test has not been verified through large-scale deployment in complex real cloud environments. Even though the inherent aggregation feature of the BLS signature (constant communication overhead) provides a foundation for its scalability, there may still be potential challenges in practical implementation, such as latency and secure key distribution for PDP clusters.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.M. and W.F.; methodology, Y.M. and W.F.; software, Y.M. and Y.Z. (Yue Zhao); validation, Y.M., Y.Z. (Yue Zhao), W.F. and Z.S.; formal analysis, Z.Y., Z.S. and Y.Z. (Yang Zhao); investigation, Y.M., Y.Z. (Yue Zhao) and Z.Y.; resources, W.F., Z.Y. and Z.S.; data curation, Y.M., Y.Z. (Yue Zhao) and Z.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.M. and Y.Z. (Yue Zhao); writing—review and editing, Y.M., W.F., Z.Y. and Y.Z. (Yang Zhao); visualization, Y.M. and Z.S.; supervision, W.F.; project administration, W.F. and Z.Y.; funding acquisition, W.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 62276273, “Research on Key Technologies of Data Security in Multi-Cloud Storage Based on Zero-Trust Architecture”.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy concerns.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the colleagues in our teaching and research department. During the experimental and paper-writing stages, they engaged in insightful discussions and provided technical support. Additionally, we are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments, which significantly enhanced the quality of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BLS | Boneh–Lynn–Shacham |

| ABAC | Attribute-Based Access Control |

| ZTA | Zero Trust Architecture |

| DAC | Discretionary Access Control |

| MAC | Mandatory Access Control |

| RBAC | Role-Based Access Control |

| PDP | Policy Decision Point |

| SoD | Static Separation of Duties |

| AS | Authentication Server |

| PEP | Policy Enforcement Point |

| PIP | Policy Information Point |

| PAP | Policy Administration Point |

| PA | Policy Administrator |

| TPM | Trusted Platform Module |

| ECDLP | Elliptic Curve Discrete Logarithm Problem |

References

- Erl, T.; Mahmood, Z.; Puttini, R. Cloud Computing: Concepts, Technology & Architecture; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Security. Cost of a Data Breach Report 2025. Available online: https://www.bakerdonelson.com/webfiles/Publications/20250822_Cost-of-a-Data-Breach-Report-2025.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Hu, V.C.; Ferraiolo, D.; Kuhn, R.; Schnitzer, A.; Sandlin, K.; Mille, R.; Scarfone, K. Guide to attribute based access control (ABAC) definition and considerations (draft). NIST Spec. Publ. 2013, 800, 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N.; Tripunitara, M.V. On safety in discretionary access control. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, Oakland, CA, USA, 8–11 May 2005; pp. 96–109. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Lin, C.; Yin, H.; Tan, Z. Security analysis of mandatory access control model. In Proceedings of the 2004 IEEE International Conference on Systems, The Hague, The Netherlands, 10–13 October 2004; Volume 6, pp. 5013–5018. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraiolo, D.; Cugini, J.; Kuhn, D.R. Role-based access control (RBAC): Features and motivations. In Proceedings of the 11th Annual Computer Security Application Conference, New Orleans, LA, USA, 11–15 December 1995; pp. 241–248. [Google Scholar]

- Madkaikar, G.; Yelisetty, K.S.; Sural, S.; Vaidya, J.; Atluri, V. Performance analysis of dynamic ABAC systems using a queuing theoretic framework. Comput. Secur. 2025, 154, 104432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccouri, S.; Abdellatif, T. BIG-ABAC: Leveraging Big Data for Adaptive, Scalable, and Context-Aware Access Control. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2025, 143, 1071–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abirami, G.; Venkataraman, R. Performance analysis of abac and abac with trust (abac-t) in fine grained access control model. In Proceedings of the 2019 11th International Conference on Advanced Computing, Chennai, India, 18–20 December 2019; pp. 372–375. [Google Scholar]

- Stafford, V. Zero trust architecture. NIST Spec. Publ. 2020, 800, 207–800. [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti, L.; Magnanini, F.; Andreolini, M.; Colajanni, M. Survivable zero trust for cloud computing environments. Comput. Secur. 2021, 110, 102419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, E.B.; Brazhuk, A. A critical analysis of Zero Trust Architecture (ZTA). Comput. Stand. Interfaces 2024, 89, 103832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boneh, D.; Lynn, B.; Shacham, H. Short signatures from the Weil pairing. In International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, H.; Chen, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, Q. PB-Raft: A Byzantine fault tolerance consensus algorithm based on weighted PageRank and BLS threshold signature. Peer Peer Netw. Appl. 2025, 18, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Tripathi, R. Scalable and secure access control policy for healthcare system using blockchain and enhanced Bell–LaPadula model. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2021, 12, 2321–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]