Abstract

In this paper, we study a generalization of Padovan numbers. We define a generating function and matrix generators for the generalized Padovan sequence. Moreover, using graph methods and a special family of generalized Padovan sequences, we derive a multinomial formula for generalized Padovan numbers. We also prove some identities that generalize known formulae for the classical Padovan numbers.

MSC:

11B39; 11B37; 11C20

1. Introduction

The Fibonacci sequence , given by the formula for with initial conditions , is one of the most celebrated sequences defined recursively. Its terms, known as Fibonacci numbers, occur in nature, art, architecture, and many branches of modern science. The ratio of consecutive Fibonacci numbers tends to the golden number , which is sometimes considered the source of all beauty, harmony, and symmetry in the world. In the shadow of the Fibonacci sequence lies the Padovan sequence, a relatively young sequence exhibiting similarly surprising and interesting properties to its golden cousin.

The Padovan sequence , named after the contemporary architect Richard Padovan, is defined by the third-order linear recurrence relation

Formula (1) generates the sequence 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 9, 14, 16, …whose terms are called Padovan numbers, and the ratio of consecutive Padovan numbers tends to a constant , known as the plastic number. The plastic number was discovered in 1924 by a French student of architecture, G. Cordonnier, and independently in 1928 by a Dutch architect, D. H. van der Laan, as an analog of the golden number in three-dimensional space. In 1994 R. Padovan, in his essay devoted to van der Laan and his architectonic ideas (see []), presented the virtues of the plastic number as a design tool that constraints the growth rate of the recursion (1) and its applications, not only in architecture but also in other fields. Many similarities between the Fibonacci and the Padovan sequences were discussed by I. Steward in [], while B.M.M. Weger in [] pointed out some crucial differences between them. Some properties and identities for the classical Padovan numbers were described in [,,]; for others we refer readers to The Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences A000931 []. Modern applications of the Padovan sequence include graph theory [,], computer science [], and cryptography [].

Analogously to the Fibonacci sequence, the Padovan sequence has been generalized in various directions. Some of these generalizations arise from combinatorial interpretations. In [] a generalization of the Padovan sequence was introduced as a consequence of counting special subsets of the set of n integers, while in [] the Padovan sequence was generalized via tiling and in [] via decompositions of a number n. A natural way to generalize the recursion (1) is to replace the sum of two terms used to obtain Padovan numbers with a sum involving a larger number of terms. V. Iliopoulos in [] investigated the recurrence relation of the form for and , with initial conditions . The same recursion, but with different initial conditions, was considered by J. J. Bravo and J. L. Herrera in []. The main focus of the authors in [,] was the characteristic polynomial associated with the generalized Padovan sequence and the roots of that polynomial, and interesting results were obtained by combining combinatorics with analytic methods. In this paper, we propose a generalization of Padovan numbers based on a similar idea, but we combine combinatorial properties with matrix theory and graph theory.

Let be an integer. We define generalized Padovan numbers by the following recurrence relation:

with initial conditions

Table 1.

Generalized Padovan numbers .

We can observe that for we get the shifted Padovan sequence, i.e., . For we obtain the sequence denoted in [] by A017818, connected with a combinatorial model of a settlement along a coastline known as the Riviera model.

Numbers can be extended for negative integers. If is an integer and

then

In Table 2 we present numbers for some negative n.

Table 2.

Generalized Padovan numbers .

In this paper, we establish several properties of the generalized Padovan sequence defined by the recursion (2). We define its matrix generators as a product of a generalized Q-matrix and a symmetric matrix of initial conditions. We also show how digraphs can be used to obtain direct formulae for generalized Padovan numbers.

2. Generating Function and Some Identities

A linear recurrence equation with constant coefficients is typically used in conjunction with a generating function, which is an elegant tool for studying it and establishing a connection between number sequences and algebraic expressions.

For the sequence the generating function can be determined using the definition of a generating function and the generalized Padovan recurrence relation.

Theorem 1.

If , are integers, then the generating function of has the following form:

Proof.

Some identities related to the generalized Padovan sequence are shown below.

Theorem 2.

For integers and ,

Proof.

Let , . Using the definition of the generalized Padovan sequence, we have

Thus, the proof is complete. □

Theorem 3.

If , are integers, then

Proof.

(By induction on n). If , then the theorem immediately follows, because by the recursion (2) we have

Since , we get

which ends the proof. □

From the above theorem we obtain the following identities for special cases .

In particular, if then we obtain the well-known identity for Padovan numbers.

Proving analogously to Theorem 3, we can also obtain the following identity.

Theorem 4.

Let , be integers.

If , then we obtain the identities of the form

3. Matrix Generators, Graph Interpretation, and Multinomial Formula

There is a long tradition of applying matrices, determinants, and permanents to study sequences of the Fibonacci type; see, for example, [,,,]. The concept of the Q-matrix as a matrix generator of the Fibonacci sequence was introduced by Ch. King in his master’s thesis, and since then the Q-matrix method has become an important tool in the analysis of Fibonacci properties; for historical details, see []. The Q-matrices for the classical Padovan sequence have also been examined in the literature; see, for instance, [,,]. In this section, we define matrix generators for generalized Padovan sequences .

Based on the recursion (2), let us define a square matrix , where and as follows. For , and , an element of the matrix is equal to the coefficient of on the right-hand side of Equation (2). For and , we put

For the above definition gives matrices of the form

, , ,

, .

Using a cofactor expansion across the last row of the matrix , we immediately obtain the following result.

Theorem 5.

Let be an integer. Then .

For the classical Fibonacci sequence, as well as for the classical Padovan sequence, the powers of the Q-matrix generate the terms of the sequence directly. In the case of generalized Fibonacci-type sequences, to be able to generate the terms of such a sequence, we usually need an additional matrix called the matrix of initial conditions. For the sequence , we define a square matrix of size as the matrix of initial conditions as follows.

For by the above definition we obtain the following symmetric matrices.

, , .

Theorem 6.

Let , be integers. Then

Proof.

By matrix multiplication and Equation (2), it follows that

which ends the proof. □

(By induction on n). If , then by (2) and simple calculations the result immediately follows. Assume that the formula (4) holds for n; we will prove it for . Since , by our assumption and by the recurrence (2) we obtain

We use the matrix to determine the explicit formula for . In [] M. C. Er introduced a family of k sequences of generalized Fibonacci numbers in the following way.

Let and be integers. Then for each , a sequence consists of generalized Fibonacci numbers defined as

with initial conditions for .

If and , then , where is nth Fibonacci number.

Based on an approach taken by D. Kalman [], M. C. Er used a square matrix A of size k of the form

and next showed that elements of sequences can be generated by , namely

In [] a special case of generalized Fibonacci numbers related to elements of sequences was considered. For an integer and non-negative integers such that at least two of are positive, the following recursion was defined:

with non-negative integers and for some as initial values.

Let us observe that for special values of , , and , , we obtain definitions of well-known sequences of the Fibonacci type.

Table 3.

Special cases of sequences .

In [] the relation between numbers and elements of sequences was proved.

Theorem 7

([]). If and are integers, then .

Let us now consider a family , of sequences defined by the recurrence relation (2),

with initial conditions for .

For clarity, if , then , so the family includes five sequences. From the recurrence (8) we obtain that .

Table 4 presents some initial words of sequences for and a few initial terms of the sequence .

Table 4.

Sequences for .

We can observe that for . Moreover, the sequence is a sum of sequences for indices . The same relations hold for the sequence with an arbitrary and corresponding sequences , where .

By definitions of numbers and , the following immediately follows.

Theorem 8.

If and are integers, then

- (i)

- ;

- (ii)

- for .

We prove that is a sum of elements of sequences for .

Theorem 9.

Let and be integers. Then

Proof.

(By induction on n). If , then

If , then

Assume that and We shall show that

So the proof is complete. □

Terms of sequences for can be used to derive a multinomial formula for .

Let A be a square matrix of size associated with recurrence (8) as follows:

It can be easily verified that the nth power, , of the matrix A has the form

Note that , and therefore

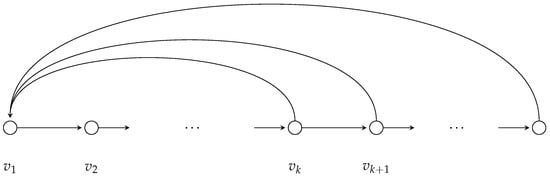

The matrix can be considered as the adjacency matrix of a special directed graph with the set of vertices . Moreover, there is an arc if . The directed graph is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Digraph .

From a well-known fact in graph theory, it follows that the entry of the matrix is equal to the number of all distinct paths of length n between the vertices and . Therefore, by (8) and the equality (11), we obtain that is the total number of distinct paths of length n from to .

To give a multinomial formula for numbers, it is sufficient to consider a single sequence from the family . Before obtaining such a formula, recall that if n is a non-negative integer, and are integers satisfying , then multinomial coefficients are defined as follows:

Theorem 10.

If , , are integers, then

Proof.

Let be a digraph shown in Figure 1. From the graph interpretation of the number , it follows that, in order to prove the multinomial Formula (12), we must count all paths of length n between vertices and . Each such path consists of elementary cycles arranged in an arbitrary order. The cycles have the form and have lengths i, . Suppose that the path contains the cycle exactly -times. Clearly, , . Each such path then corresponds to an ordering, with repetitions allowed, of cycles from the set in an arbitrary order. Then the length of this path is . The cycle , , can be placed in the path in

ways. Hence, there are

such paths in the digraph . Summing over all collections satisfying the equation , we obtain the total number of such paths, which is equal to

and this completes the proof. □

Based on Theorem 8 and using Equation (12), we immediately obtain a most convenient expression.

Corollary 1.

For integers and ,

An equivalent form is

To illustrate Corollary 1, let us compute . Using (13), we obtain

The triples satisfying the equation are . Therefore,

4. Conclusions

In this paper, we introduced generalized Padovan numbers and established several of their properties. Futhermore, we showed that the Q-matrix associated with the generalized Padovan recursion can be viewed not only as a matrix generator but also as the adjacency matrix of a particular digraph, yielding interesting results that arise from combining matrix theory, combinatorics, and graph theory. As a direction for further research, it would be worthwhile to consider the characteristic polynomial associated with the generalization of the Padovan sequence defined here, as well as the roots of the polynomial, following approaches similar to those in [,]. It also seems interesting to find a connection between generalized Padovan numbers and Pascal’s triangle and to extend the notion of generalized Padovan numbers to polynomials. Applications of matrix generators of Fibonacci-type sequences in coding theory, initiated by work of A.P. Stakhov [] and subsequently developed by other authors, have opened a new area of investigations. We hope that the matrix generators we have defined in this paper for generalized Padovan numbers will likewise find applications in cryptography, where such matrices are used in encoding and decoding algorithms.

Author Contributions

The authors contributed equally to this work. Conceptualization, M.W.-M. and A.W.; methodology, M.W.-M. and A.W.; validation, M.W.-M. and A.W.; formal analysis, M.W.-M. and A.W.; writing—original draft preparation, M.W.-M. and A.W.; writing—review and editing, M.W.-M. and A.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Padovan, R. Dom Hans van der Laan: Modern Primitive; Architectura and Natura Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1994; pp. 1–260. [Google Scholar]

- Steward, I. Tales of neglected number. Sci. Am. 1996, 274, 102–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weger, B.M.M. Padua and Pisa are exponentially far apart. Publ. Math. 1997, 41, 631–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedifor, S.J. Combinatorial identities for the Padovan numbers. Fibonacci Q. 2019, 57, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, A.G.; Anderson, P.G.; Horadam, A.F. Properties of Cordonnier, Perrin and van der Laan numbers. Int. J. Math. Edu. Sci. Technol. 2006, 37, 825–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, F.; Bozkurt, D. Some properties of Padovan sequence by matrix method. Ars Comb. 2012, 104, 149–160. [Google Scholar]

- Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences. Available online: https://oeis.org/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Włoch, I.; Włoch, A. On some multinomial sums related to the Fibonacci type numbers. Tatra Mt. Math. Publ. 2020, 7677, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirga, M.; Włoch, A.; Włoch, I. Some new graph interpretations of Padovan numbers. Symmetry 2024, 16, 1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Kim, J. On the Padovan codes and Padovan cubes. Symmetry 2023, 15, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherin, D.A.A.; Maheswari, V.; Balaji, V. Privacy Preserving Message using Padovan Sequence. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1964, 022026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Włoch, I.; Włoch, A. Generalized Padovan numbers, Perrin numbers and maximal k-independent sets in graphs. Ars Comb. 2011, 99, 359–364. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, R.P.M.; Alves, F.R.V.; Catarino, P.M.M.C. Combinatorial interpretation of numbers in the generalized Padovan sequence. Axioms 2022, 11, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Włoch, A.; Wołowiec-Musiał, M.; Bednarz, U. New type of distance Padovan sequences via decomposition technique. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliopoulos, V. The plastic number and its generalized polynomial. Cogent. Math. 2015, 2, 1023123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, J.J.; Herrera, J.L. Generalized Padovan sequences. Commun. Korean Math. Soc. 2022, 37, 977–988. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, E.P., Jr. Generalized Fibonacci numbers and associated matrices. Amer. Math. Mon. 1960, 67, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvester, J.R. Fibonacci properties by matrix methods. Math. Gaz. 1979, 63, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalman, D. Generalized Fibonacci numbers by matrix methods. Fibonacci Q. 1982, 20, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Er, M.C. Sums of Fibonacci numbers by matrix methods. Fibonacci Q. 1984, 22, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, H.W. A history of the Fibonacci Q-matrix and higher-dimensional problem. Fibonacci Q. 1981, 19, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokhuma, K. Padovan Q-matrix and generalized relations. Appl. Math. Sci. 2013, 7, 2777–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokhuma, K. Matrices formula for Padovan and Perrin sequences. Appl. Math. Sci. 2013, 7, 7093–7096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stakhov, A.P. Fibonacci matrices, a generalization of the “Cassini formula”, and a new coding theory. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2006, 30, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).