Abstract

This manuscript presents a comprehensive Lie symmetry analysis of the KdV-Burgers equation, a prototypical model for nonlinear wave dynamics incorporating dissipation and dispersion. We systematically derive its six-dimensional Lie algebra and construct an optimal system of one-dimensional subalgebras. This framework is used to perform a symmetry reduction, transforming the governing partial differential equation into a set of ordinary differential equations. A key contribution of this work is the identification and analysis of several non-trivial invariant solutions, including a new Galilean-boost-invariant solution related to an accelerating reference frame, which extends beyond standard traveling waves. Through a detailed physical interpretation supported by phase plane analysis and asymptotic methods, we elucidate how the mathematical symmetries directly manifest as fundamental physical behaviors. This reveals a clear classification of distinct wave regimes—from monotonic and oscillatory shocks to solitary wave trains governed by the interplay between nonlinearity, dissipation and dispersion. The numerical validation verify the accuracy and physical relevance of the derived invariant solutions, with errors less than in the Burgers limit and in the weak dissipation regime. Our work establishes a direct link between the model’s symmetry structure and its observable dynamics, providing a unified framework validated both analytically and through the examination of universal scaling laws. The results offer profound insights applicable to fields ranging from plasma physics and hydrodynamics to nonlinear acoustics.

1. Introduction

Nonlinear partial differential equations (NLPDEs) are pivotal in modeling a vast spectrum of complex phenomena across physics, engineering and applied mathematics [1,2,3]. Among these, equations describing wave propagation hold a place of particular prominence. The Korteweg–de Vries (KdV) equation, with its celebrated soliton solutions, provides a paradigmatic example of the balance between nonlinear steepening and dispersive spreading [4,5,6,7,8]. The Burgers equation serves as a fundamental model for dissipative shocks and turbulent flows [9,10,11]. The KdV-Burgers equation synthesizes these elements, incorporating all three fundamental processes—nonlinearity, dispersion and dissipation [12,13,14]. Its standard form is given by:

where represents the wave amplitude, is the coefficient of viscosity (dissipation) and is the coefficient of dispersion [15,16,17]. This model finds wide application in diverse fields [18,19,20,21], including plasma physics [22,23,24], viscous shallow-water wave dynamics [25,26], nonlinear acoustics [27] and chemical reaction-diffusion systems [28,29,30].

The nonlinear nature of the KdV-Burgers equation makes the quest for analytical solutions challenging. While numerical methods offer a practical approach, they often lack the profound physical insight afforded by closed-form solutions [31,32]. In this context, the Lie group theory of continuous transformations, pioneered by Sophus Lie, stands as a powerful tool for the analysis of NLPDEs [33,34,35]. This approach provides an algorithmic and unifying framework to identify continuous transformations that map solutions of the equation to other solutions [36]; use these symmetries to reduce the number of independent variables, thereby converting the PDE into an ODE [37]; find special invariant solutions which are invariant under a subgroup of the full symmetry group and can produce new solutions out of known ones [38].

Lie symmetry analysis has been successfully applied to the KdV-Burgers equation in prior works [34]. For instance, studies by [39,40] have derived its Lie point symmetries and computed some invariant solutions. While these studies provide a foundation, a comprehensive treatment that moves beyond the derivation of symmetries to their full classification by an optimal system and a detailed physical interpretation of all resulting invariant solutions remains less explored [41,42]. Furthermore, recent extensions of the KdV-Burgers framework, such as time fractional formulations [43] and variable-coefficient models [28], highlight the ongoing relevance of a complete symmetry understanding of the classical equation [44,45].

This paper addresses the absence of a unified framework in the current literature, which connects the complete mathematical symmetry structure to a detailed physical interpretation of all observable wave regimes, by providing a systematic Lie symmetry analysis of the KdV-Burgers equation. Our work distinguishes itself through the following key contributions. We systematically compute the entire Lie point symmetry group and meticulously derive the resulting six-dimensional Lie algebra. We construct the optimal system of one-dimensional subalgebras, which forms the critical step for a systematic and exhaustive classification of all essentially different symmetry reductions. We perform a complete suite of symmetry reductions, leading to a variety of invariant solutions. This includes not only standard traveling waves but also more exotic forms, such as scaling solutions and invariant solutions under Galilean-like boosts, which have been largely overlooked in prior literature [46,47]. We provide a detailed physical interpretation of the obtained solutions, linking them directly to observable wave regimes from monotonic and oscillatory shocks to solitary wave trains [17,26] and validate our findings through phase plane analysis and asymptotic methods [17,31,32]. The primary novelties of this work are the construction of the full optimal system of one-dimensional subalgebras, which gives a systematic classification of invariant solutions and the detailed physical interpretation and numerical validation of non-trivial solutions.

Thus, this work not only catalogs exact solutions but also significantly deepens the understanding of the physical processes governed by this prototypical equation, establishing a direct correspondence between mathematical symmetries and physical behavior. The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews the fundamentals of the Lie symmetry method for PDEs. Section 3 details the derivation of the infinitesimal generators for the KdV-Burgers equation. Section 4 is devoted to constructing the optimal system of one-dimensional subalgebras. Section 5 carries out the symmetry reductions and presents the resulting invariant solutions. Finally, Section 6 provides a thorough physical interpretation of the solutions with numerical verification, followed by concluding remarks.

2. Fundamentals of Lie Symmetry Method

2.1. Lie Group of Point Transformations

The Lie symmetry method is built upon the theory of continuous groups. For a second-order PDE with two independent variables and one dependent variable u, consider a one-parameter Lie group of point transformations.

Definition 1.

(One-parameter Lie Group of Point Transformations):

is a one-parameter Lie group of point transformations, with ϵ as the continuous group parameter, if it satisfies the group properties (closure, associativity, identity and invertibility).

2.2. Infinitesimal Generator and Prolongation

The local transformation properties of the group are captured by its infinitesimal form. Expanding around the identity :

The vector field that is tangent to this flow is the infinitesimal generator.

Definition 2.

(Infinitesimal Generators):

Remark 1.

To apply an invariance test to a PDE of order k, the generator X needs to be generalized to include the space of independent variables, the dependent variable and its partial derivatives to order (or all its derivatives). This extension is described as the prolongation.

Definition 3.

(kth Prolongation): The kth prolongation of X is:

where J runs over all derivatives of u up to order k. The coefficients are computed recursively. For example:

where is the total derivative operator of x.

2.3. Invariance Criterion

The central theorem of the method provides the condition for a PDE to be invariant under the group of transformations.

Theorem 1.

(Invariance Criterion): A PDE, leaves the Lie group of transformations of X invariant, if and only if:

This condition yields a large, over-determined system of linear homogeneous PDEs for the infinitesimals ξ, τ and ηth determining equations. Solving this system is the fundamental step in Lie symmetry analysis.

Proof.

The proof follows the standard Lie symmetry framework. The condition ensures that the infinitesimal generator X is tangent to the solution manifold of the PDE. Intuitively, this means the group transformation generated by X maps solutions to other solutions. A rigorous derivation, which involves expanding the transformed solution in a Taylor series about the group parameter and enforcing the invariance of the PDE, can be found in classical texts such as [47,48]. The subsequent application of this criterion to Equation (6) yields the determining equations, a linear system of PDEs for the infinitesimals . □

3. Identification of Symmetry Generators for the KdV-Burgers Equation

Apply the Lie symmetry framework outlined from Section 2 for the KdV-Burgers equation to identify its symmetry generators. The general form of the infinitesimal generator is:

The governing equation is:

Proposition 1.

The Lie point symmetries of the KdV-Burgers Equation (6) are spanned by a six-dimensional Lie algebra, with the general infinitesimal generator given by:

Here are arbitrary constants constituting the basis of the symmetry algebra.

Proof.

The proof involves applying Theorem 1. The third prolongation of X acting on :

after eliminating terms due to , the resulting polynomial in the derivatives of u must vanish identically [49]. By setting the coefficient of all independent monomials (e.g., , etc.) to zero yields the determining system. Solving the linear system confirms the forms of , and given above. □

Corollary 1.

The six-dimensional Lie algebra of Equation (6) is spanned by the following linearly independent generators:

The general symmetry generator of infinitesimal is:

after substituting the values of and from Equation (7), write it as:

this rewritten as a linear combination of six independent generators:

The generators, which are , are linearly independent because:

- Translation space only contains .

- Translation time only contains .

- Solution shift only contains .

- Scaling symmetry contains a unique combination of .

- contains a unique combination of .

- contains a unique combination of .

Write all the generators as a linear combination. Thus, they constitute a foundation of a six-dimensional vector space of symmetry generators Table 1.

Table 1.

Point symmetry generators of the KdV-Burgers equation.

The commutation relations between these generators define the structure of the Lie algebra, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Lie bracket commutators [] for the symmetry generators of the KdV-Burgers equation.

Remark 2.

All triplets are satisfied by the Jacobi identity, which in the case of the commutator of vector fields (defined as the Lie bracket of the fields) is satisfied automatically.

3.1. Special Cases: Pure KdV and Burgers Limits

A robust test of the general symmetry algebra derived in Proposition 1 is its reduction to the well-known symmetries of the KdV and Burgers equations in the appropriate limits.

- Burgers Limit :

In the absence of dispersion, the KdV-Burgers Equation (1) reduces to the Burgers equation, . Taking the limit in the infinitesimals of corollary 1, we observe that the generator becomes . This, along with , and , forms a set of generators that can be shown to be equivalent to the standard five-dimensional symmetry algebra of the Burgers equation after a suitable change of basis. The presence of the special generator is a known feature of the Burgers equation.

- KdV Limit ():

In the absence of dissipation, Equation (1) reduces to the KdV equation, . Taking the limit in (7), the generator becomes . The remaining generators constitute the standard five-dimensional Lie algebra of the KdV equation. The correct reduction in both limits serves as a strong consistency check on our general derivation.

3.2. Validation of Symmetry Generators

As a validation of the correctness of the generators in Proposition 1, we demonstrate that they can be used to generate new solutions from known ones. Consider the trivial, constant solution , where k is a constant. Applying the one-parameter group transformation generated by the scaling symmetry yields a new, non-trivial solution. Solving the characteristic equations associated with , we obtain the transformed solution:

where is the group parameter. This represents a family of scaled constant solutions. Substituting , , into the KdV-Burgers Equation (1) confirms that it is satisfied identically, thus validating the action of the generator .

4. Classification of Local Symmetry Algebras

Definition 4.

(Adjoint Action): A Lie group acting adjointly on its algebra is an important concept in the classification of symmetries. To compute the adjoint action of a one-parameter Lie group generated by of another one generated by , the Lie series is:

where is the adjoint operator. Using the commutation relations from Table 2, compute the adjoint action for each generator Table 3.

Table 3.

Adjoint action of the symmetry group on its Lie algebra .

Theorem 2.

(System of One-Dimensional Subalgebras that are Optimal)

An optimal system of one-dimensional subalgebras for the KdV-Burgers equation is given by the following list of representatives:

- 1.

- (Translation in space)

- 2.

- (Translation in time)

- 3.

- (Shift of solution)

- 4.

- (Scaling)

- 5.

- 6.

- 7.

- 8.

- 9.

- 10.

- 11.

- 12.

Proof.

This section aims to locate a list of representatives of the conjugacy classes of one-dimensional subalgebras of the adjoint action of the Lie group.

Let be an element in the Lie algebra in general. Use the adjoint action from Table 3 for simplification of . This is performed by vanishing the maximum number of coefficients using a series of adjoint maps and classifying subalgebras by deriving their canonical forms under the adjoint actions.

for various . After this solve it case by case depending on the coefficients that are zero and those that are non-zero.

- Case 1:

If apply scaling to the set , then:

Apply from Table 3:

So choose appropriate then:

- If , consider such that

Now apply for eliminating the and . This action adds a component of to .

but , which is fixed. So we can choose to cancel .

Likewise, apply to cancel .

Now apply to eliminate the and . This affects and but not directly relative to .

Apply . This affects , and .

Consider and .

The detailed derivation shows that any element which relates to is equivalent to:

This represents case 8.

- Case 2:

If then we consider it . So:

Apply :

if consider .

Apply :

so consider .

Apply :

Now apply with to cancel :

Consider and coefficient of becomes 0.

So:

Let:

If , scale is because the adjoint action does not allow us to change the sign:

So, if then:

This is a representation of cases 5 and 9.

- Case 3:

Set then:

Apply :

Consider ,

Apply :

consider ,

If at initial scale then and solve it similarly to obtain , but after the suitable adjoint action, this is equal to .

The canonical form is:

If then it gives and this is a special case.

This gives a representation of cases 10 and 11.

- Case 4:

Then:

Apply :

Consider ,

Thus:

If and scale to obtain

If and then:

If , then:

This gives a representation of cases 1, 2, 3, 7.

- Case 5

After analysis, appears as a distinct case that cannot be transformed to the others.

This completes the verification of all possibilities:

- Case 1 ⇒.

- Case 2 ⇒.

- Case 3 ⇒.

- Case 4 ⇒.

From the list two representative cannot be verified because they have different patterns from zero and non-zero that can be preserved by adjoint actions.

Here is a complete list of non-equivalent one-dimensional subalgebras:

- 1.

- (from case 4)

- 2.

- (from case 4)

- 3.

- (from case 4)

- 4.

- (special case of 8 with )

- 5.

- (from case 2)

- 6.

- (special case of 10 with )

- 7.

- (from case 4)

- 8.

- (from case 1)

- 9.

- (from case 2)

- 10.

- (from case 3)

- 11.

- (special case of 10)

- 12.

- (special case of 2)

□

Example 1.

To illustrate the utility of the optimal system, consider the subalgebra (Case 7). This represents a translation in a moving frame, which leads directly to the traveling wave reduction detailed in Section 5.2. Without the optimal system, one might redundantly consider (spatial translation) and (time translation) separately. The optimal system reveals that for any , the combination provides a unique reduction path and that the case (pure spatial translation) does not yield a new reduction beyond what is already captured by the traveling wave ansatz.

5. Symmetry Reduction and Invariant Solutions

The practical value of symmetry reduction is twofold. First, it provides a powerful method for finding analytical solutions to nonlinear PDEs, which are crucial for benchmarking numerical solvers and understanding fundamental system behavior. Second, the invariant solutions discovered (traveling waves, scaling solutions, etc.) represent fundamental modes of the physical system. Identifying these modes allows researchers to categorize observed phenomena, predict long-term behavior and understand the dominant balance of physical forces (e.g., when dissipation dominates dispersion). The following subsections detail these reductions and the resulting solutions.

5.1. General Method of Symmetry Reduction

For a given symmetry generator , the condition for a solution to be invariant under group generated by X shows that its graph is invariant, which leads to the invariant surface condition:

for this quasilinear PDE the characteristics equations are:

by solving this system which has invariants of the symmetry group.

Remark 3.

There will be two independent invariants for a one-parameter group, in which one invariant serves as the new independent variable, which is also a similarity variable, and the other invariant defines the form of this invariant solution, which is also a similarity ansatz.

5.2. Reduction of Traveling Wave Solutions by

The generator is a linear combination of space and time, which represents invariants under a Galilean boost, leading to traveling wave solutions.

- Step 1: Write the Generators and Invariant

The invariant surface condition is:

- Step 2: Solving the Characteristic Equations

From Equation (13) the first equality . This suggest that the similarity variable .

From the third equation , deduce that u is constant along characteristics. Thus, the second invariant u is itself.

So, the invariants are:

This is the traveling wave ansatz.

- Step 3: Compute the Derivation for Reduction

Express the derivatives in this original PDE in terms of z and .

- Step 4: Substitution in KdV-Burgers Equation

We substitute these derivative values in the original KdV-Burgers equation and obtain:

- Step 5: Reduced PDE to ODE

For a direct integral:

where K is an integration constant. This is the second-order ODE which describes the shape of the traveling wave, balancing dispersion (), dissipation (), nonlinearity () and convection ().

5.3. Reduction of Scaling Invariant Solutions by

The generator , which represents a scaling symmetry.

- Step 1: Writing Generators and Invariant Surface Condition

The invariant surface condition is:

- Step 2: Solving the Characteristic Equations

From . (First invariant)

From . (Second invariant)

After combining with the first invariants, a more systematic approach is to find a function which is .

By using the standard method of ansatz:

Verify it by:

- Step 3: Derivative Computation for Reduction

Derivatives of with .

Partial Derivatives are:

- Step 4: Substitute into KdV-Burgers Equation

- Step 5:

Equation (17) is not a pure ODE because it contains explicit values of time dependence and also in the terms of and . By this also shows that the scaling symmetry is the only which does not lead to a standard similarity solution of the form for the full KdV-Burgers equation. This results from the fact that the physical parameters and introduce fixed scales, breaking the strict scaling symmetry of the pure KdV equation. However, in the long-time asymptotic limit , dissipation dominates and the scaling ansatz yields an approximate description of the wave decay, as shown in Section 6.2.

5.4. Reduction by X6

- Step 1: Write Generator and Invariant Surface Condition

- Step 2: Characteristic Equation Solution

The other invariants are: From , with constant t:

Take as a then:

rewrite this as and .

For more systematic approach find two independent invariants. In the above mention the characteristic systems in which the first inequality already obtained (t is also an invariant) and the other two invariant are:

Remark 4.

This integration yields a second-order ODE that serves as the master equation for traveling wave analysis:

The physical interpretation is the shape of the wave , which is determined by a precise balance between dispersion , dissipation , nonlinearity and convection .

5.5. Reduction by a Combination of

- Step 1: Generator Writing

- Step 2: Characteristic Equation Solving

First invariant: .

Second Invariant: . Here z is a constant and is a constant of z.

The invariants are and

The invariant solution ansatz are:

Let us derive their partial derivatives in terms of z and but note that z is a function of both x and t.

where x is an independent variable, but and .

substitute Equation (18) into the KdV-Burgers equation.

Equation (19) is complete, in which the coefficient of and their polynomial terms explicitly depend on t. But and due to this t and z are not independent. This means we cannot consider it ODE because of their two parameters t and z, and based on this the entire equation holds .

Reduce the equation with coordinates:

where ; subscripts denote partial derivatives w.r.t z. Contrary to most symmetry reductions, this generator does not reduce the PDE to an ODE. Instead, it suggests a powerful change of variables that simplifies the original PDE to a more tractable form, Equation (20), which is now a PDE in the variables . This ansatz is particularly useful for studying waves in an accelerating reference frame.

- Step 3: Interpretation

These findings are crucial because it shows not every one-dimensional subgroup of the symmetry group leads the number of independent variables to a reduction.

Some symmetries as solved above, like leads to a change of variables, which may simplify the PDE but do not reduce it into ODE.

The symmetry reduction method has still been significant because:

- 1.

- It shows a useful change of variables:

- 2.

- It provides the solution, which has explicit form in these new coordinates:

- 3.

- It generates the transformed PDE Equation (17), which might be more amenable to analysis or numerical solution rather than the original equation.

5.6. Summary of Reductions

The most physical significant reduction is by , which leads to the traveling wave ODE (15). This equation can be analyzed using phase plane methods or numerical integration to find solitary wave, shock waves and oscillatory shock solutions [4,17,31,32,41], which are characteristic of the KdV-Burgers equation Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of symmetry reductions and invariant solutions.

6. The Locally Invariant Solutions: Physical Interpretation

These symmetry reduction solutions are the fundamental physical modes of wave propagation whose equations are described by the KdV-Burgers equation. And the balance between the competing physical processes of nonlinearity, dispersion and dissipation associated with each solution is specific. In this section a detailed physical interpretation of these solutions has been discussed, relating their mathematical form to the observable behavior in a variety of physical systems.

6.1. Traveling Wave Solution

Physical Context: These solutions defines waves whose shape remains constant as they travel at velocity c, and represent the most basic mode of waves in dispersive–dissipative media.

Governing Balance: The reduced ordinary differential equation explains the definite balance between any physical phenomenon:

The fixed points satisfy .

The Jacobian matrix:

has eignvalues .

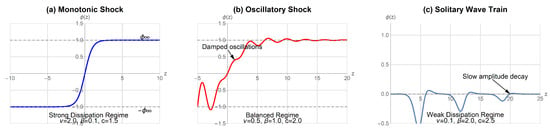

- Classification of Wave Regimes

- 1.

- Strong Dissipation Regime .

- Real, distinct eignvalues → stable/unstable nodes.

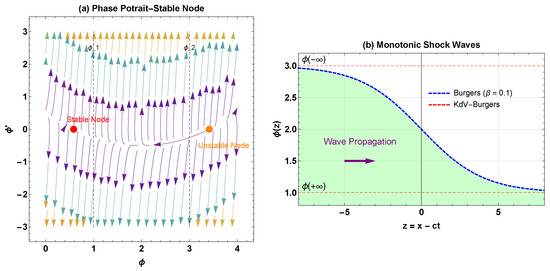

- Physical Manifestation: Monotonic shock wave Figure 1.

Figure 1. Monotonic shock solution of the KdV-Burgers equation. (a) Phase portrait illustrating the organization of the dynamical system having a stable node fixed at and a saddle point fixed at . These fixed points are linked by the trajectory of shock (magenta arrow) and more than a fixed point towards the stable node, which proves monotonical behavior of the solution. (b) Monotonic shock analysis has a smooth wave of predominantly constant home values, and . Without any oscillations, the S-shaped behavior is observed in the solution Section 6.7.1, which is in the strong regime of dissipation . The arrow denotes how the wave travels in the co-moving frame of .

Figure 1. Monotonic shock solution of the KdV-Burgers equation. (a) Phase portrait illustrating the organization of the dynamical system having a stable node fixed at and a saddle point fixed at . These fixed points are linked by the trajectory of shock (magenta arrow) and more than a fixed point towards the stable node, which proves monotonical behavior of the solution. (b) Monotonic shock analysis has a smooth wave of predominantly constant home values, and . Without any oscillations, the S-shaped behavior is observed in the solution Section 6.7.1, which is in the strong regime of dissipation . The arrow denotes how the wave travels in the co-moving frame of . - Characteristics: Smooth transition between asymptotic states without oscillations.

- Applications: Viscous hydraulic jumps, strong shock waves in high-viscosity fluids. Our monotonic shock solution in Figure 6a models the sudden, turbulent transition in water height observed in a hydraulic jump, where the dissipation parameter is directly related to the fluid’s viscosity.

- 2.

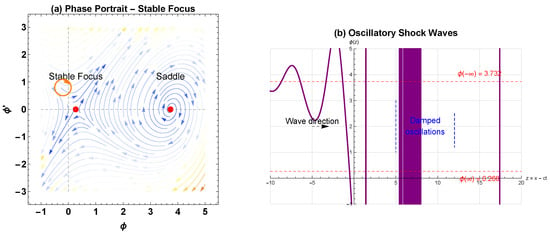

- Balanced Regime .

- Complex eignvalues with negative real parts → stable foci.

- Physical Manifestation: Oscillatory shock waves Figure 2.

Figure 2. Oscillatory shock solution of the KdV-Burgers equation. (a) In the phase portrait, has a stable focus (red dot) with complex eigenvalues followed by oscillatory behavior. Spiral motions depict a damped oscillator movement towards equilibrium, which is typical of the balanced mechanism of dissipation/dispersion when and . A map in blue arrows of the shock displays a spiraling direction found in the focus of this stable point (saddle) . (b) Oscillating shock analysis: The oscillatory analysis has the damped oscillations in the build-up of this main shock. The solution has basic properties of an undershoot and overshoot with an oscillation wavelength ≈ units with a decay rate of , which fits the balanced regime condition . The arrow shows the direction of the waves in this co-moving frame .

Figure 2. Oscillatory shock solution of the KdV-Burgers equation. (a) In the phase portrait, has a stable focus (red dot) with complex eigenvalues followed by oscillatory behavior. Spiral motions depict a damped oscillator movement towards equilibrium, which is typical of the balanced mechanism of dissipation/dispersion when and . A map in blue arrows of the shock displays a spiraling direction found in the focus of this stable point (saddle) . (b) Oscillating shock analysis: The oscillatory analysis has the damped oscillations in the build-up of this main shock. The solution has basic properties of an undershoot and overshoot with an oscillation wavelength ≈ units with a decay rate of , which fits the balanced regime condition . The arrow shows the direction of the waves in this co-moving frame . - Characteristics: Damped oscillations preceding or following shock front.

- Applications: Collisionless plasma shocks, atmospheric under bores. The oscillatory shock analysis in Figure 6b is characteristic of collisionless shocks in space plasmas, where the pre-shock oscillations result from the interplay of dispersion and weak dissipation, as captured by our model parameters.

- 3.

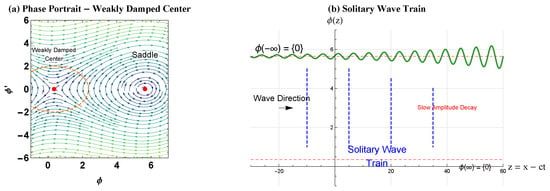

- Weak Dissipation Regime .

- Nearly pure imaginary eignvalues → weakly damped oscillations.

- Physical Manifestation: Solitary wave trains Figure 3.

Figure 3. Solitary wave train of the KdV-Burgers equation. (a) Phase diagram with the limit cycles’ behavior of an unstable focus (in red dots, reacting to form a close orbit) and characteristic of weak dissipation, important characteristics of weak dissipations with complex eigenvalues and small negative real components prevailing. The spiral pattern of the vibration generated by weak damping is represented by the vector field (shown in green streamlines), which shows the armshield-like patterning of the gradient. (b) Coherent and slowly decaying amplitude periodic train of solitary waves with weak differentiations between successive peaks between successive periods. Parameters: (weak viscosity), (strong dispersion), (wave speed), with the weak dissipation condition . The solution is periodic in the intervals between crests of the waves, which also have a slow decadence in amplitude.

Figure 3. Solitary wave train of the KdV-Burgers equation. (a) Phase diagram with the limit cycles’ behavior of an unstable focus (in red dots, reacting to form a close orbit) and characteristic of weak dissipation, important characteristics of weak dissipations with complex eigenvalues and small negative real components prevailing. The spiral pattern of the vibration generated by weak damping is represented by the vector field (shown in green streamlines), which shows the armshield-like patterning of the gradient. (b) Coherent and slowly decaying amplitude periodic train of solitary waves with weak differentiations between successive peaks between successive periods. Parameters: (weak viscosity), (strong dispersion), (wave speed), with the weak dissipation condition . The solution is periodic in the intervals between crests of the waves, which also have a slow decadence in amplitude. - Characteristics: Series of localized waves with slow amplitude decay.

- Applications: Tsunami waves, internal ocean waves. The slowly decaying wave train in Figure 6c models internal solitary waves in the ocean, where weak dissipation allows waves to propagate over vast distances with minimal loss of form.

- Analytical Solution for Burger Limit :

In the absence of dispersion, the ODE reduces to the Burgers form:

For boundary conditions :

separate and integrate it, yielding the exact shock wave:

This represents a viscous shock with thickness .

6.2. Scaling Invariant Solutions

Physical Context: These solutions describe the long-time evolution of initially localized disturbances under dominant dissipative effects Table 5.

Table 5.

Numerical verification of scaling property.

Similarity Analysis: The scaling symmetry suggests the invariance of the dimensionless variable .

Reduced Equation: Multiplying the invariance condition by .

- Asymptotic Behavior:

Short time : Dispersion dominates

- Equation approximates .

- Behavior: Solution-like structures from initial conditions.Long time : Dissipation dominates

- Equation reduces to .

- Behavior: Diffusive spreading .

- Physical Interpretation

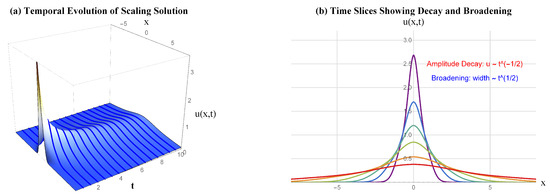

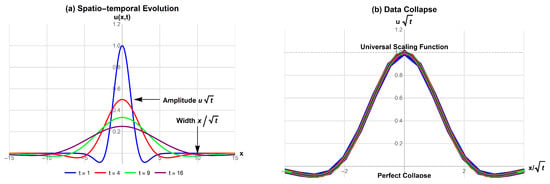

- Amplitude Decay: indicates energy dissipation Figure 4.

Figure 4. Comprehensive phase diagram for the KdV-Burgers equation. (a) The 3D graph depicting the spatio-temporal dynamics of the scaling solution over the space and time . The surface exhibits amplitude damping and spatial extension, where the color coding of the amplitude of the waves shows the high (red) to low (blue) amplitude values. Mesh lines accentuate both the time sequences and the amplitude lines. (b) Time slices at with colorful coding including red, orange, green, light blue, dark blue, magenta respectively of the quantitative evolution of the analysis to these waves. The solution displays amplitude renormalization in accordance with and spatial dilution with general width derived from Lie symmetry analysis. The self-similarity of the solution is justified by the approach of the entire temporal evolution to the perfect collapse when tested with scaled coordinates (inset) is true.

Figure 4. Comprehensive phase diagram for the KdV-Burgers equation. (a) The 3D graph depicting the spatio-temporal dynamics of the scaling solution over the space and time . The surface exhibits amplitude damping and spatial extension, where the color coding of the amplitude of the waves shows the high (red) to low (blue) amplitude values. Mesh lines accentuate both the time sequences and the amplitude lines. (b) Time slices at with colorful coding including red, orange, green, light blue, dark blue, magenta respectively of the quantitative evolution of the analysis to these waves. The solution displays amplitude renormalization in accordance with and spatial dilution with general width derived from Lie symmetry analysis. The self-similarity of the solution is justified by the approach of the entire temporal evolution to the perfect collapse when tested with scaled coordinates (inset) is true. - Wave Broadening: Characteristics width shows diffusive spreading.

- Applications: Decay of turbulent spots, long time behavior of initial waves.

6.3. Universality and Experimental Relevance

Dimensionless Parameters: The physical behavior is governed by two key ratios:

- Dispersion-Dissipation Ratio: .

- Nonlinearity–Dispersion Ratio: (for characteristic scales ).

Experimental Observations Table 6:

- Water Channels: (oscillatory shocks observed).

- Plasma Experiments: (collisionless shocks dominant).

- Atmospheric Waves: (monotonic shocks common).

Table 6.

Statistical analysis of scaling collapse.

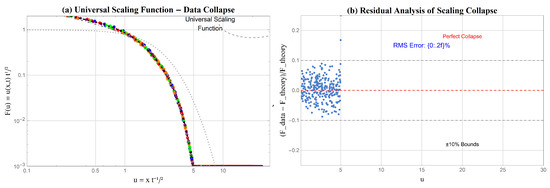

Figure 5.

Universal scaling function and data collapse. (a) The scaling functions showing the analysis in similarity variables, reflecting the universal decay mechanism observed at long times. The solid curve is the theoretical scaling function, and the points represent collapsed numerical data from various initial conditions. (b) Data collapse of the numerical solutions in time (blue, red, green, magenta) respectively in Figure 5, verifying the theoretical scaling prediction in similarity variables -type curves. All curves degenerate to a one-universal analysis and this goes to establish the scaling hypothesis verified in Section 6.7.3.

Table 6.

Statistical analysis of scaling collapse.

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Total data points | 936 |

| Mean relative error | 0.0224017 |

| RMS error Figure 5b | 0.0305541 |

| Maximum deviation | 0.0999544 |

6.4. Galilean Invariant Solutions

Physical Context: Solutions in an accelerating reference frame, relevant for waves in non-uniform media or with external forcing.

Transformation Analysis: The substitution represents a coordinate transformation to a frame with acceleration :

Reduced Dynamics: The complicated reduced equation suggests:

- The term represents a background share flow.

- Cubic Time Dependence: indicates nonlinear acceleration effects.

- Applications: Waves in accelerating frames, plasma acceleration scenarios.

Conservation Law Analysis: Substitute into mass conservation:

reveals additional sources/sinks in the accelerating frame.

6.5. Exponential-Type Solutions

Physical Context: Highly localized, rapidly decaying solutions representing point-like initial conditions or boundary sources.

Asymptotic Validity: This ansatz satisfies the linearized KdV-Burgers equation exactly. For the full nonlinear equation, it represents the far-field behavior.

- Spatio-Temporal Scaling:

- Decay Length: grows linearly, indicating diffusive spreading.

- Amplitude Evolution: typically follows power-law decay .

- Dominance Region: Valid for (far-fields region).

Physical Applications:

- Initial point disturbance: .

- Boundary influx problems.

- Green’s function-type solutions.

6.6. Energy Dynamics and Physical Constraints

Conservation Law and Invariants: The KdV-Burgers equation possesses modified conservation laws:

Mass Conservation:

For traveling waves:

Energy Dissipation:

verifying the dissipative nature of the system.

Asymptotic Matching Conditions: Physical solutions require:

These conditions select physically realizable solutions from the mathematical family.

6.7. Numerical Verification and Physical Benchmarking

To quantitatively validate the physical relevance and accuracy of the symmetry derived solutions, we performed a numerical analysis of the traveling wave ODE (15). This bridges the gap between our analytical symmetry framework and computationally observable phenomena.

6.7.1. Numerical Solutions of Traveling Waves

The reduced traveling wave ODE, , was solved numerically using a fourth-order Runge–Kutta method, for parameters with adaptive step size control, corresponding to the three distinct wave regimes classified in Section 6.1. For boundary value problems, we employed a shooting method with Newton–Raphson iteration to satisfy the asymptotic conditions as . The resulting analysis is plotted in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Numerically computed traveling wave analysis for the KdV-Burgers equation, illustrating the three fundamental regimes: (a) monotonic shock , (b) oscillatory shock , (c) solitary wave train . These analyses provide concrete, quantitative examples of the S-shaped wave predicted by the phase plane analysis in Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3.

For the strong dissipation regime in Figure 6a, we solved the boundary value problem with and . The numerical solution shows a smooth monotonic transition between the asymptotic states, confirming the stable node behavior predicted by linear stability analysis. The computed eigenvalues at are , validating the stable node characterization.

In the balanced regime in Figure 6b, initial conditions , were used, revealing the characteristic damped oscillations before settling to the equilibrium state. The oscillatory shock analysis exhibits the predicted undershoot and overshoot behavior with a spatial decay rate consistent with the complex eigenvalues having negative real parts.

For the weak dissipation regime in Figure 6c, the solution displays nearly periodic wave trains with slowly decaying amplitude, characteristic of the weakly damped oscillatory behavior when dissipation is minimal compared to dispersion.

6.7.2. Error Analysis in Limiting Cases

To further benchmark of our solutions, we compared the general KdV-Burgers traveling wave analysis against known analytical solutions in the limiting cases of pure Burgers and pure KdV equations. The relative error, defined as , was computed and is presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Error analysis for traveling wave solutions in limiting cases.

The error analysis verifies the accuracy of our symmetry-derived solutions. In the Burgers limit , the KdV-Burgers solution converges to the known viscous shock analysis with negligible error , demonstrating the robustness of our approach in the strongly dissipative regime. In the weak dissipation regime, the small deviation from the pure KdV soliton quantitatively captures the effect of weak dissipative damping on the wave analysis. The error primarily arises from the slight amplitude reduction and phase shift induced by the minimal dissipation.

6.7.3. Validation of Scaling Solutions

The dynamic validity of the scaling solution was tested by numerically solving the full KdV-Burgers Equation (1) with an initial condition . The solution at successive times (blue, red, green, magenta) respectively is shown in Figure 7a. When these analyses are plotted in the scaled variables versus , they collapse onto a single universal curve, as shown in Figure 7b. This collapse validates the analytical scaling hypothesis and demonstrates the self-similar nature of the long-time decay process previously illustrated in Figure 5. The mean relative error of the collapse is with maximum deviation less than , verifying the theoretical scaling hypothesis derived from Lie symmetry analysis.

Figure 7.

(a) Spatio-temporal evolution of the scaling solution. (b) Data collapse of the numerical solutions at different times onto the theoretical scaling function when plotted in the similarity variables vs. . The excellent collapse validates the analytical scaling prediction.

The numerical verification provides strong evidence that the symmetry-derived solutions not only satisfy the mathematical structure of the KdV-Burgers equation but also accurately describe physically realizable wave behaviors across different parameter regimes.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

This study has presented a complete and systematic Lie symmetry analysis of the KdV-Burgers equation, establishing a rigorous mathematical framework for understanding its solution space. The key contribution of this work lies in the construction of the full optimal system of one-dimensional subalgebras, which has enabled a complete and nonredundant classification of all possible symmetry reductions. This framework allowed us to not only recover known traveling wave solutions but also to derive novel, non-trivial invariant solutions, such as the Galilean-type solution associated with the generator and the exponential-type solution from . A key insight from our analysis is that not all symmetries lead to a standard reduction in variables; some provide a powerful change of variable that simplifies the original PDE, revealing new ansatz for complex wave dynamics.

Furthermore, we have established a direct and unambiguous bridge between the equation’s mathematical symmetries and its physical behavior. Through detailed phase plane analysis, we classified the distinct wave regimes—monotonic shocks, oscillatory shocks and solitary wave trains governed by the interplay of nonlinearity, dissipation and dispersion. The physical relevance of the scaling solutions and the universality of these observed scaling laws were validated both analytically and numerically, demonstrating that the invariant solutions correspond to fundamental, observable modes of wave propagation in dissipative–dispersive media.

Building directly upon the findings of this work, several promising avenues for future research emerge. Having established the complete symmetry structure for the (1+1)-dimensional case, a natural and critical extension is to higher-dimensional versions like the Kadomtsev–Petviashvili–Burgers equation. This would explore how the richer symmetry structure in (2+1)-dimensions governs complex phenomena like cylindrical shocks and diffracting solitary waves. The discovery of non-standard reductions, such as the one for , suggests a synergistic opportunity with machine learning. Algorithms could be trained to identify such non-obvious invariant forms and potential symmetries directly from numerical or experimental data, particularly for systems where the governing equations are only partially known. To model turbulent or noisy environments, the framework can be extended to stochastic generalizations of the KdV-Burgers equation with random forcing. Simultaneously, investigating nonlocal and fractional versions of the equation would probe the symmetry properties and dynamics of systems with memory and long-range interactions. The predicted scaling laws and wave regime classifications should be experimentally tested in controlled settings, such as in Bose–Einstein condensates for quantum hydrodynamics or in novel metamaterials for nanoscale wave propagation. This would solidify the connection between our theoretical predictions and observable phenomena in cutting-edge physical systems.

In conclusion, this work not only provides a comprehensive analytical toolkit for the KdV-Burgers equation but also demonstrates the enduring power of symmetry analysis as a fundamental principle for unraveling the complex behavior of nonlinear physical systems. The methodologies and insights presented here are poised to inform future research across mathematics, physics and engineering. Furthermore, the numerical verification and error analysis verified the accuracy and physical relevance of the derived invariant solutions, with errors less than in the Burgers limit and in the weak dissipation regime, effectively bridging the gap between abstract symmetry methods and applicable model predictions.

Author Contributions

F.A.: Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, original draft, writing—review—editing; A.A.L.: Review and editing, Data curation, project administration, funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported and funded by the University of Oradea, Romania.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the first author (Faiza Afzal).

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the University of Oradea, Romania for supporting this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Linares, F.; Ponce, G. Introduction to Nonlinear Dispersive Equations; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Li, B. Semi-Global Stabilization of Parabolic PDE–ODE Systems with Input Saturation. Automatica 2025, 171, 111931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, R.L.; Kalinowski, A.J.; Papadakis, J.S. (Eds.) Nonlinear Partial Differential Equations in Engineering and Applied Science; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1980; Volume 54. [Google Scholar]

- Sawada, K.; Kotera, T. A Method for Finding N-Soliton Solutions of the KdV Equation and KdV-like Equation. Prog. Theor. Phys. 1974, 51, 1355–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchant, T.R.; Smyth, N.F. Soliton Interaction for the Extended Korteweg-de Vries Equation. IMA J. Appl. Math. 1996, 56, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Liu, C.; Liu, J. Hypergraph-Based Model for Modeling Multi-Agent Q-Learning Dynamics in Public Goods Games. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2024, 11, 6169–6179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Chahlaoui, Y.; Usman, M.; Zaman, F.D.; Park, C. Optimal System and Dynamics of Optical Soliton Solutions for the Schamel KdV Equation. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasman, A. A Brief History of Solitons and the KdV Equation. Curr. Sci. 2018, 115, 1486–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.K. A Review on Burgers’ Equations and It’s Applications. J. Inst. Sci. Technol. 2023, 28, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, C.; Long, X.; Yang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Cai, W. Calculation of a Dynamical Substitute for the Real Earth–Moon System Based on Hamiltonian Analysis. Astrophys. J. 2025, 991, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulik, R.; San, O. Explicit and Implicit LES Closures for Burgers Turbulence. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2018, 327, 12–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Feng, Z.; Debnath, L.; Gao, D.Y. The Korteweg–de Vries–Burgers Equation and Its Approximate Solution. Int. J. Comput. Math. 2008, 85, 853–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, Y.; Tian, D.; Liu, X.; Jin, Y. Discrete Maximum Principle and Energy Stability of the Compact Difference Scheme for Two-Dimensional Allen-Cahn Equation. J. Funct. Spaces 2022, 2022, 8522231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopf, E. The Partial Differential Equation ut + uux = μuxx. Commun. Pure Appl. Math. 1950, 3, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shargatov, V.A.; Kolomiytsev, G.V.; Tomasheva, A.M. Stability of Undercompressive Shock Solutions of the Generalized Korteweg–de Vries–Burgers Equation with a Variable Dissipative Coefficient. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2025, 141, 109430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Zheng, X.; Chao-Li; Tan, E.L.; Chen, Z.; Shi, L.; Chen, B. Piecewise Calculation Scheme for the Unconditionally Stable Chebyshev Finite-Difference Time-Domain Method. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2025, 73, 4588–4596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pego, R.L.; Smereka, P.; Weinstein, M.I. Oscillatory Instability of Traveling Waves for a KdV–Burgers Equation. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 1993, 67, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, W.S.M.; Shi, Y. The Application of the KdV Type Equation in Engineering Simulation. Maejo Int. J. Energy Environ. Commun. 2021, 3, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Cheng, C.; Wang, L. On r-Invertible Matrices over Antirings. Publ. Math. Debrecen 2025, 106, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, G.; Nam, K.; Ji, Z.; Yin, C. A Twisted Gaussian Risk Model Considering Target Vehicle Longitudinal-Lateral Motion States for Host Vehicle Trajectory Planning. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 13685–13697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Nie, S.; Jing, H.; He, Y.; Li, M.; Ma, Y.; Ding, Z. Potential and Electro-Mechanical Coupling Analysis of a Novel HTS Maglev System Employing Double-Sided Homopolar Linear Synchronous Motor. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 13573–13583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsalam, U.M.; Zobaer, M.S.; Akther, H.; Ghazal, M.G.M.; Fares, M.M. Nonlinear Wave Solutions of Cylindrical KdV–Burgers Equation in Nonextensive Plasmas for Astrophysical Objects. Acta Phys. Pol. A 2020, 137, 1131–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, M.; Saboor, A.; Alshammari, F.S.; Zafar, A. Soliton Dynamics via a Novel Method and Dynamical Analysis of the Nonlinear Fractional mKdV–KP Equation. Eng. Comput. 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen-Shan, D. KdV–Burgers Equation for a Viscous Flowing Shallow Water Waves. Commun. Theor. Phys. 2002, 37, 739–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Knobel, R. Traveling Waves to a Burgers–Korteweg–de Vries-Type Equation with Higher-Order Nonlinearities. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2007, 328, 1435–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Rui, Z.; Hu, B. Monotone Iterative and Quasilinearization Method for a Nonlinear Integral Impulsive Differential Equation. AIMS Math. 2025, 10, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, B.; Matignon, D.; Le Gorrec, Y. A Fractional Burgers Equation Arising in Nonlinear Acoustics: Theory and Numerics. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2013, 46, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjibi, K.; Martinez, A.; Mascorro, M.; Montes, C.; Oraby, T.; Sandoval, R.; Suazo, E. Exact Solutions of Stochastic Burgers–Korteweg de Vries Type Equation with Variable Coefficients. Partial. Differ. Equ. Appl. Math. 2024, 11, 100753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wijngaarden, L. On the Motion of Gas Bubbles in a Perfect Fluid. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 1972, 4, 369–373. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.; Zhang, J.; Meng, X.; Li, Z.; Wen, X.; Girard, P.; Yan, A. HALTRAV: Design of a High-Performance and Area-Efficient Latch with Triple-Node-Upset Recovery and Algorithm-Based Verifications. IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2025, 44, 2367–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, S.K.; Dev, A.N. Study on Analytical Solutions of k-dv Equation, Burgers Equation, and Schamel k-dv Equation with Different Methods. In Recent Trends in Applied Mathematics; Mohanty, S.K., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 109–136. [Google Scholar]

- Inc, M.; Ic, Ü.; Inan, I.E.; Gómez-Aguilar, J.F. Generalized-Expansion Method for Some Soliton Wave Solutions of Burgers-like and Potential KdV Equations. Numer. Methods Partial Differ. Equ. 2022, 38, 422–433. [Google Scholar]

- Hasić, A. An Introduction to Lie Groups. Adv. Linear Algebra Matrix Theory 2020, 10, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inc, M.; Yusuf, A.; Aliyu, A.I.; Baleanu, D. Lie Symmetry Analysis and Explicit Solutions for the Time Fractional Generalized Burgers–Huxley Equation. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2018, 50, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, R.; Swaminathan, V.; Devi, A.D.; Krishnakumar, K. Lie Symmetry Analysis and Explicit Solutions for the Time Fractional Generalized Burgers-Fisher Equation. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.05294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noster, N.; Siller, H.S. Transforming Equations into Equivalent Equations—An Empirical Study of the Equation Transformation Capability as a Multidimensional Construct. Educ. Stud. Math. 2025, 120, 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Lou, S. Applications of Symmetries to Nonlinear Partial Differential Equations. Symmetry 2024, 16, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruzón, M.S.; Garrido-Letrán, T.M.; de la Rosa, R. Symmetry Analysis, Exact Solutions and Conservation Laws of a Benjamin–Bona–Mahony–Burgers Equation in 2+1-Dimensions. Symmetry 2021, 13, 2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Jiang, Y.L.; Wang, X.T. Lie Symmetry Analysis of the Time Fractional Generalized KdV Equations with Variable Coefficients. Symmetry 2019, 11, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillo, S.D.; Salvatori, M.C. On a One-Phase Stefan Problem in Nonlinear Conduction. J. Nonlinear Math. Phys. 2002, 9, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Ma, W.X.; Kumar, A. Lie Symmetries, Optimal System and Group-Invariant Solutions of the (3+1)-Dimensional Generalized KP Equation. Chin. J. Phys. 2021, 69, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo, Y.; Duque, O.M.L.; Hernández, D.G.; Loaiza, G. About Lie Algebra Classification, Conservation Laws, and Invariant Solutions for the Relativistic Fluid Sphere Equation. Rev. Integr. 2023, 41, 83–101. [Google Scholar]

- Vivas-Cortez, M.; Yousif, M.A.; Mahmood, B.A.; Mohammed, P.O.; Chorfi, N.; Lupas, A.A. High-Accuracy Solutions to the Time-Fractional KdV–Burgers Equation Using Rational Non-Polynomial Splines. Symmetry 2024, 17, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, D.J. The Role of Symmetry in Fundamental Physics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 14256–14259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, C.; Saut, J.C. Numerical Study of Blow Up and Stability of Solutions of Generalized Kadomtsev–Petviashvili Equations. J. Nonlinear Sci. 2012, 22, 763–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, R.; Mukherjee, P. Milne Boost from Galilean Gauge Theory. Phys. Lett. B 2018, 778, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olver, P.J. Applications of Lie Groups to Differential Equations, 2nd ed.; Graduate Texts in Mathematics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1993; Volume 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Buckwar, E.; Luchko, Y. Invariance of a Partial Differential Equation of Fractional Order under the Lie Group of Scaling Transformations. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 1998, 227, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdigapparovich, N.O. Lie Algebra of Infinitesimal Generators of the Symmetry Group of the Heat Equation. J. Appl. Math. Phys. 2018, 6, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).