Abstract

Knots and links are ubiquitous in chemical systems. Their structure can be responsible for a variety of physical and chemical properties, making them very important in materials development. In this article, we analyze the topological structures of interlocking molecules composed of metal-peptide rings using the concept of polyhedral links. To that end, we discuss the topological classification of alternating polyhedral links.

Keywords:

polyhedral link; alternating link; interlocking molecule; metal-peptide ring; Tait flyping conjecture MSC:

57K10

1. Introduction

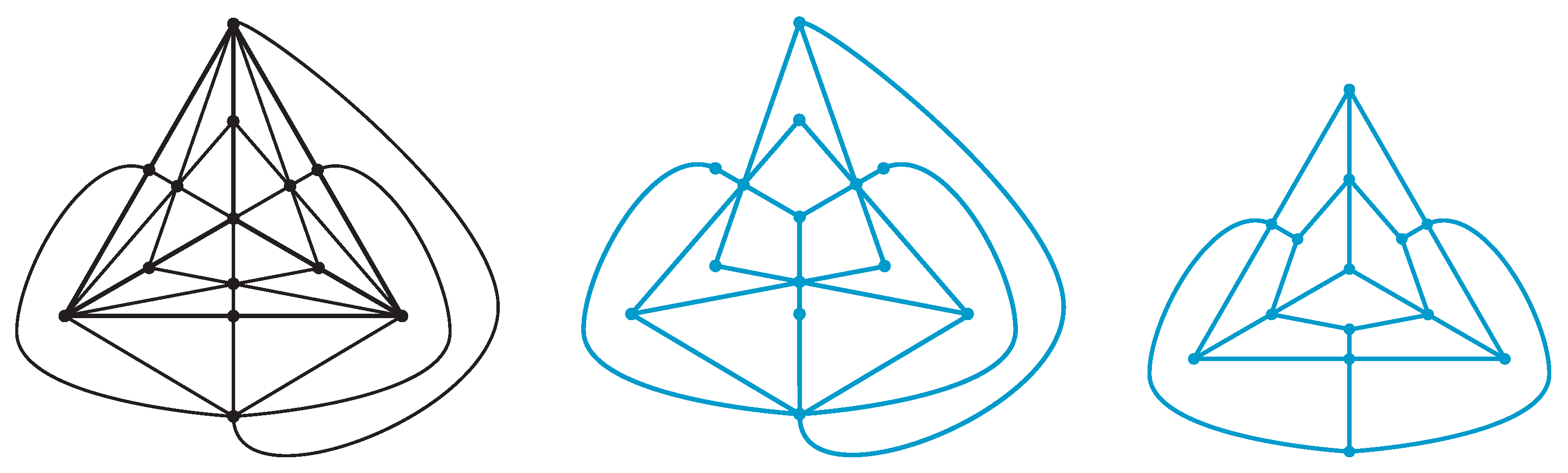

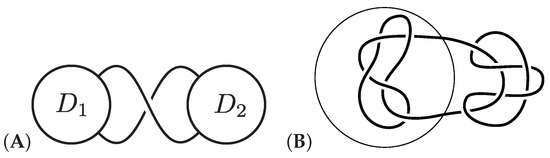

A knot is a simple closed curve in a three-dimensional space. A disjoint union of knots is called a link or a catenane. See Figure 1 for examples. Knots and links can be found in many biological, chemical, and physical systems, including closed circular DNA [1,2,3,4,5], proteins [6,7,8], and topological vortices [9]. For references on knot theory and its applications, see [10,11,12,13,14,15], for example.

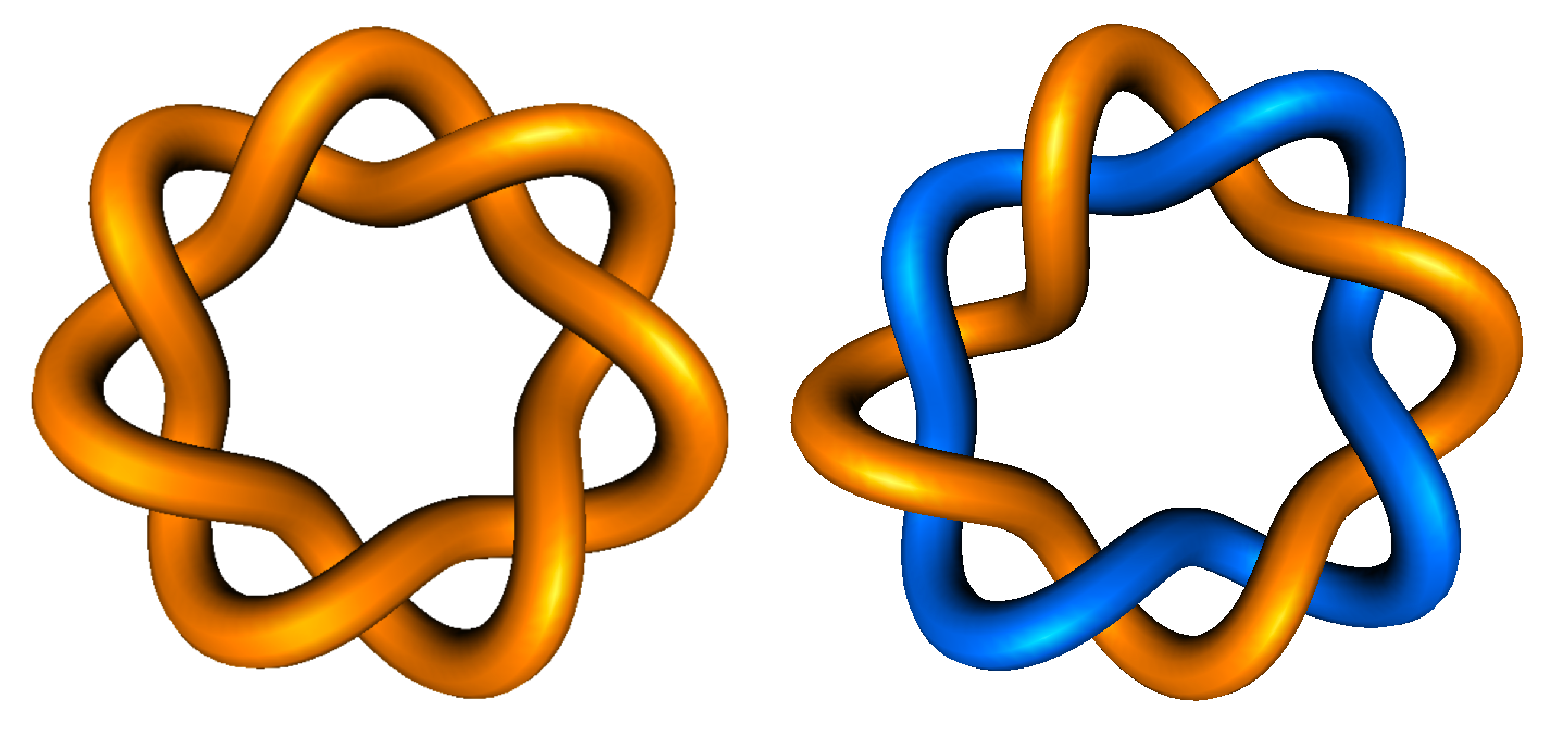

Figure 1.

Example of a knot and a link. (Left) -torus knot ( knot). (Right) -torus link ( link). The crossing numbers of the -torus and the -torus link are 7 and 8, respectively. These are examples of alternating knots and links. These images are created by KnotPlot [16,17].

In [18,19], two topologically different metal-peptide interlocking molecules with entangled structures of 4 rings and 12 crossings were synthesized, and in [20], another interlocking molecule with 6 rings and 24 crossings was synthesized. See Section 3 for details. Recently metal-peptide -torus knots and links with are created in [21,22]. Figures of the -torus knot ( knot) and the -torus link ( link) can be found in Figure 1. See [23,24] for recent surveys on this subject.

The topological structures of molecules in [18,19,20] can be considered as polyhedral links [19,20]. The topological aspects of polyhedral links have been studied, for example, in [25,26,27]. This article discusses the property and the classification of alternating polyhedral links. By applying the results, we characterize the topology of interlocking structures.

The main results of this article are the classification of polyhedral links (Theorems 1–3). We show that the alternating link diagrams of polyhedral links of these types do not admit nontrivial flypes (see Definition 4). Hence, by the affirmative answer of the Tait flyping conjecture [28], the classification of the topology of these interlocking structures can be achieved by simply analyzing their alternating diagrams. Our results provide a solid tool for classifying the topological structures of interlocking molecules since the classification can be done directly by observing the diagram of the links without having to calculate the link invariants.

As applications of our results, we can give the design of two similar but different topological structures and propose a complex, intertwined, stable capsule structure with a huge cavity (see Section 6).

This article is organized as follows. In Section 2, we review the definitions of polyhedral links and consider their topological properties. In Section 3, we discuss examples of interlocking molecules of metal-peptides rings. In Section 4, we give the classifications of polyhedral links. In Section 5, we give the proofs of the main results. In Section 6, we provide discussion and conclusions.

2. Polyhedral Links

First, we review the definitions of polyhedral links in [25,26,27] that appear as the topology of the interlocking structures and discuss the property of alternating diagrams of polyhedral links.

2.1. Definitions of Polyhedral Links

In this article, a polyhedron is a two-dimensional complex embedded in the three-dimensional space with flat polygonal faces and straight edges. See [29] for a reference on polyhedra. We assume that a polyhedron is homeomorphic to the 2-sphere .

A link diagram is alternating if its crossings alternate over and under around each link component. See Figure 1 and Figure 2 for examples of alternating diagrams. A link is called alternating if it has an alternating diagram.

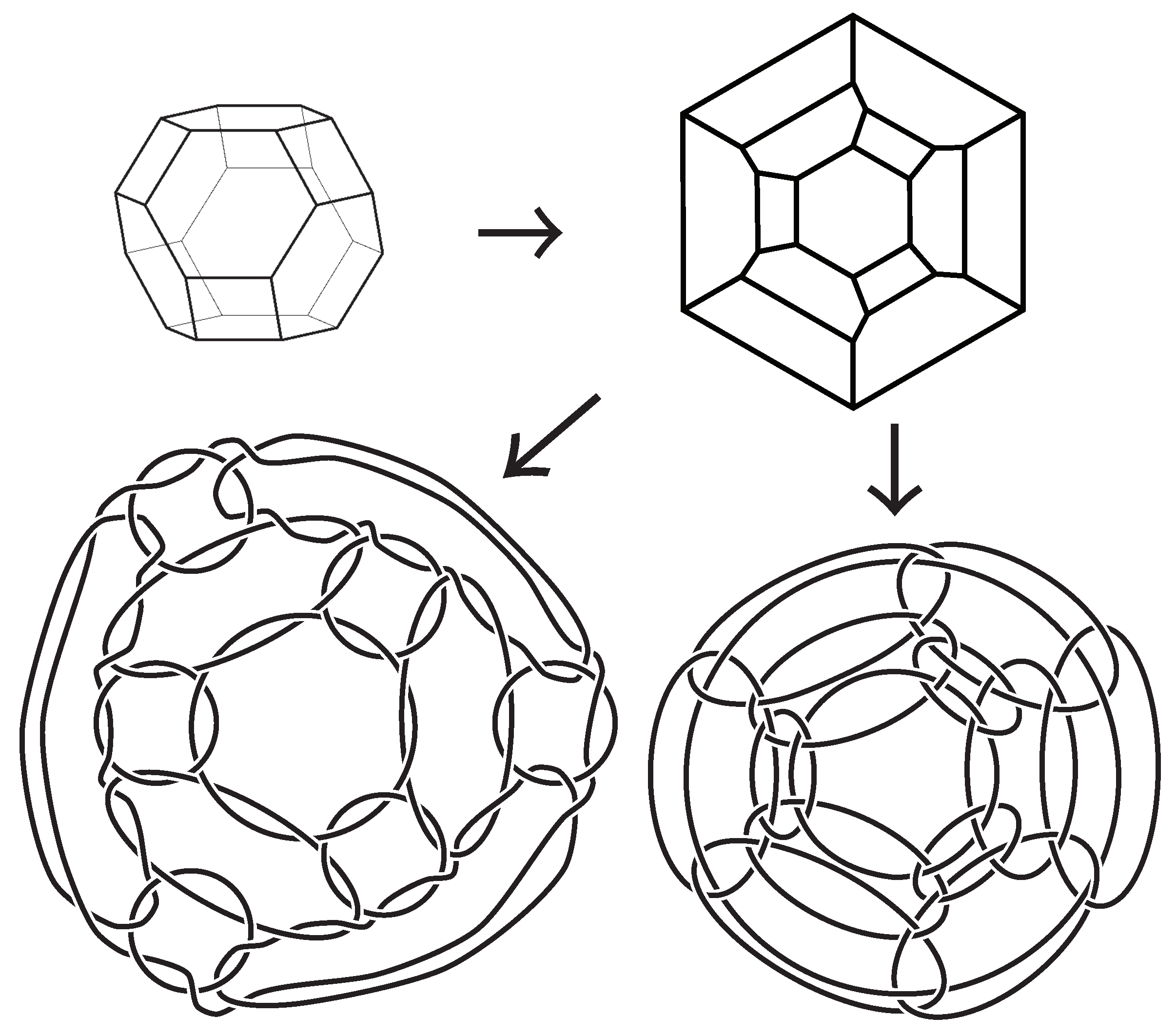

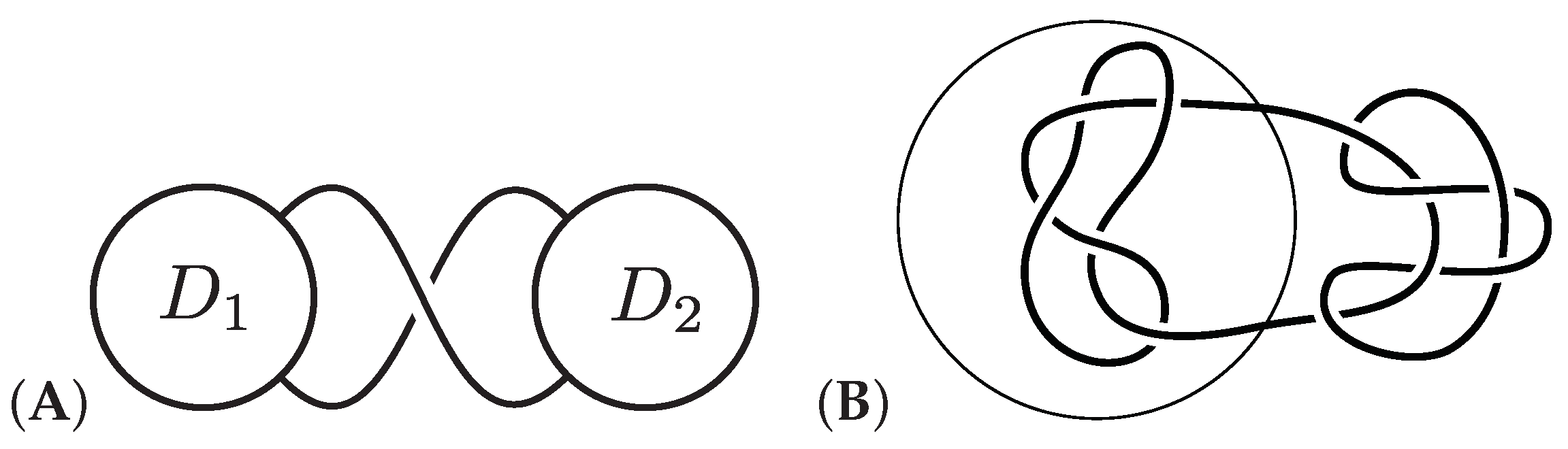

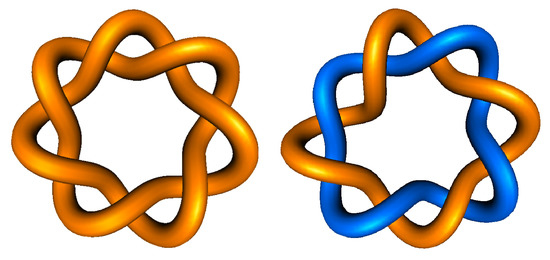

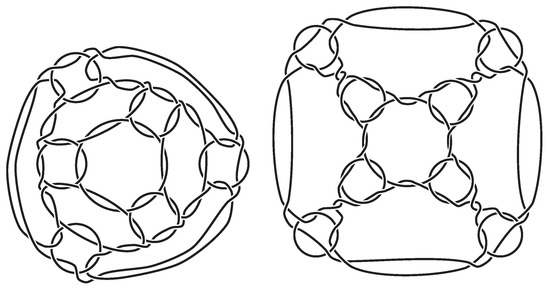

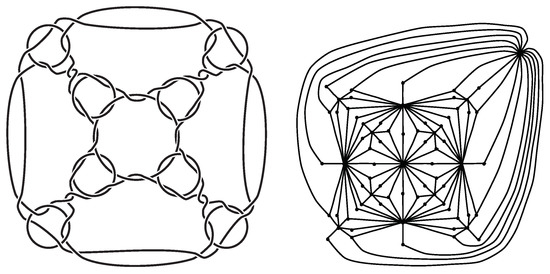

Figure 2.

Alternating diagrams of type-A (left) and type-B (right) truncated octahedral links. The degree of each vertex of the truncated octahedron is 3. The truncated octahedron has 24 vertices, 36 edges, and 14 faces. Each of these polyhedral links has 14 components and 72 crossings. See Proposition 1 and Table 2.

Polyhedral links are defined in [25,26,27]. We will review the definitions below. In this article, we only consider alternating polyhedral links.

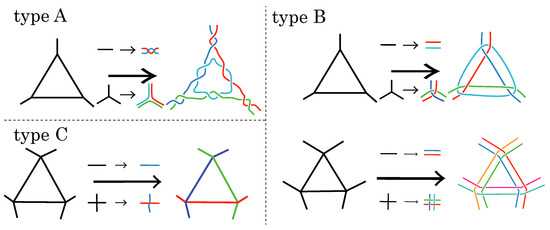

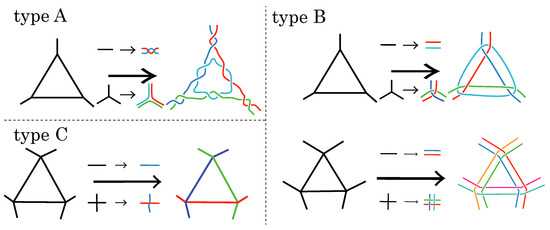

Definition 1

(Type-A polyhedral link (Branched curves and n-twisted double line polyhedral link [26])). Let P be a polyhedron. An alternating link L is called a branched curve and n-twisted double line polyhedral link of P or a type-A polyhedral link of P if its alternating diagram is obtained by applying operations as in Figure 3A.

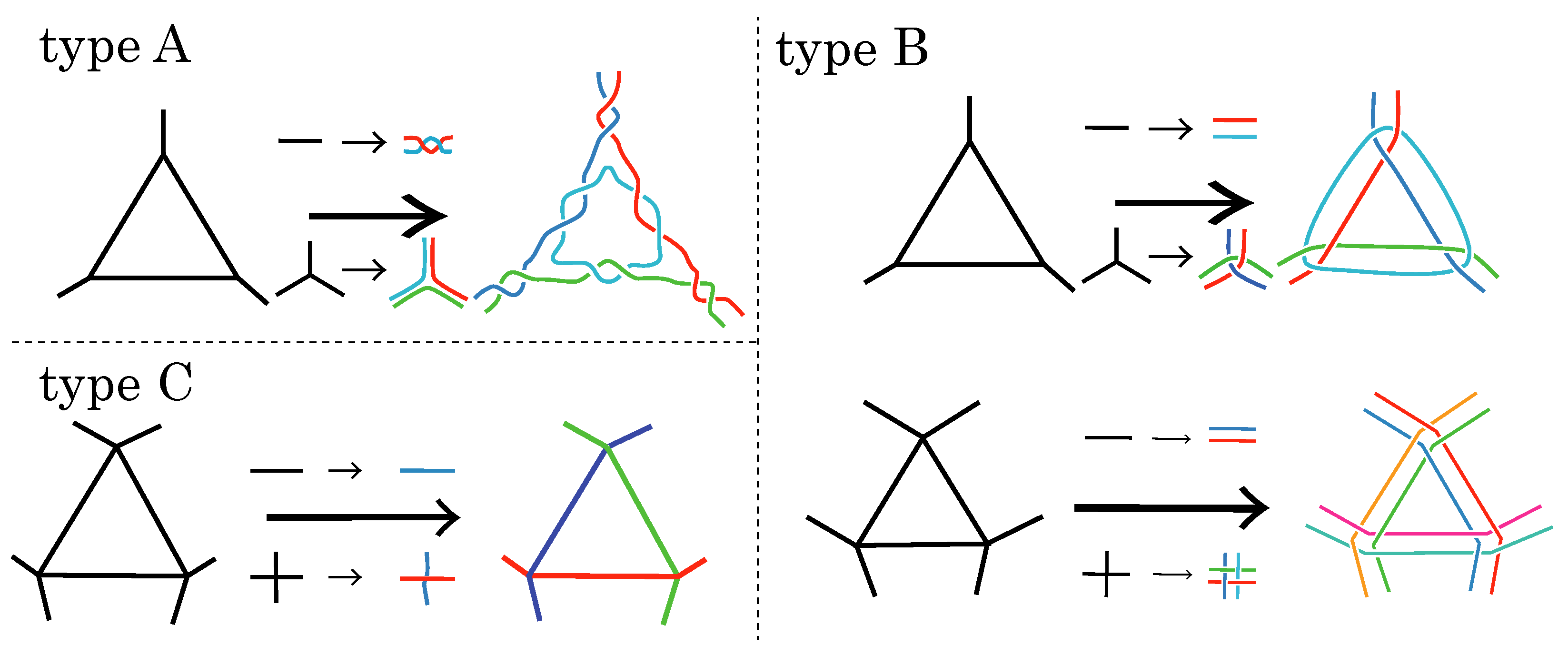

Figure 3.

Construction of polyhedral links from polyhedra.In each part of the figure, the left-hand side (black) is a part of a polyhedron and the right-hand side (color) is a part of the obtained polyhedral link. (A, Top left) type-A polyhedral link (branched curves and n-twisted double line polyhedral link). In this example, the degree of the vertex is 3. For a type-A polyhedral link, we prepare d strings at each vertex of degree d and two strings at each edge as in the figure. In the case where , there are two crossings on each edge of P. (B, Top right and bottom right) type-B polyhedral link (cross curve and double line polyhedral link). If the degree of a vertex is d, then d crossings appear at the vertex. Each edge is changed into two parallel strings. (C, Bottom left) type-C polyhedral link (single line polyhedral link). A type-C polyhedral link is defined for a polygon with degree 4 at each vertex. In this article, we assume that all polyhedral links are alternating.

Here, we only consider the case where . See Figure 2 for an example of a type-A polyhedral link.

Definition 2

(Type-B polyhedral link (Cross curve and double line polyhedral link [25])). Let P be a polyhedron. An alternating link L is called a cross curve and double line polyhedral link of P or a type-B polyhedral link of P if its alternating diagram is obtained by applying operations as in Figure 3B.

See Figure 2 for an example of a type-B polyhedral link.

Definition 3

(Type-C polyhedral link (Single line polyhedral link [27])). Let P be a polyhedron with degree 4 at each vertex. An alternating link L is called a single line polyhedral link of P or a type-C polyhedral link of P if its alternating diagram is obtained by applying operations as in Figure 3C.

Since P is homeomorphic to , polyhedral links of P have link diagrams on . By Definitions 1–3, we obtain specific alternating diagrams of alternating polyhedral links. Such a diagram is called the standard alternating diagram of an alternating polyhedral link. A standard alternating diagram of an alternating polyhedral link attains the minimal crossing number. See Section 5.

2.2. Properties of Polyhedral Links

In this subsection, we discuss the topological properties of polyhedral links. The following is discussed in [26].

Proposition 1

([26]). Let v, e, and f be the number of vertices, edges, and faces of a polyhedron P, respectively. Then, we have the following.

- 1.

- Let L be a type-A polyhedral link of P. Then, the number of components of L is f, and the number of crossings is .

- 2.

- Let L be a type-B polyhedral link of P. Then, the crossing number of L is the sum of the degrees of vertices of P. If each vertex of P has degree d, then the number of crossings of L is . Moreover, if each vertex of P has degree 3, then the number of components of L is f.

- 3.

- Suppose each vertex of P has degree 4. Let L be a type-C polyhedral link of P. Then, the number of crossings of L is v.

For example, the crossing number of a type-A tetrahedral link is 12.

Here, we include the table of the numbers of components and crossing numbers of polyhedral links of regular polyhedra (Platonic solids) in Table 1 and semi-regular polyhedra (Archimedean solids) in Table 2. For the definition of these polyhedra, see [29].

Table 1.

The number of components and crossings of polyhedral links of regular polyhedra (Platonic solids). The degree of a vertex is denoted by d. The number of vertices, edges, and faces are denoted by v, e, and f, respectively. For example, the pair of a type-A tetrahedral link means that the number of components and crossings are 4 and 12, respectively.

Table 2.

The number of components and crossings of polyhedral links of semi-regular polyhedra (Archimedean solids).

Two links are ambient isotopic if one link can be transformed into another by a smooth deformation without cutting and intersecting. See, for example, ref. [10] for the precise definition. A link is called chiral if it is not ambient isotopic to its mirror image. The symmetry of a polyhedral link is discussed in [26].

Proposition 2

([26]).

- 1.

- A type-A tetrahedral link possesses T symmetry.

- 2.

- A type-A cubic link and a type-A octahedral link possess O symmetry.

- 3.

- A type-A dodecahedral link and a type-A icosahedral link possess I symmetry.

In particular, these links are chiral.

3. Interlocking Molecule of Metal-Peptide Rings and Polyhedral Links

In [18,19,20], the interlocking molecules of metal-peptide rings with complex topology have been synthesized. For details, see those papers.

In [18,19], the folding assemblies of 4-component 12-crossing peptide catenanes from tripeptide ligands and Ag have been reported. Topologically, we consider tripeptides as arcs and Ag’s as vertices. These would form rings. By changing the sequence of peptides, two different topologies have been produced. For example, the PGP sequence (P: L-proline, G: glycine) gives a type-A tetrahedral link, while the TPP sequence (T: L-threonine) gives a type-B tetrahedral link. Note that a type-B tetrahedral link can also be considered a type-C cuboctahedral link (See Proposition 3). In [20], it is reported that the ditopic PPxAP sequence (A: L-alanine, x: imino-(1,3-phenylene)carbonyl spacer) peptide and Ag self-assemble to form a type-A cubic link with six components and 24 crossings. The structure of this catenane is a capsular shell with an 1.6-nm-sized cavity.

One motivation for this study of polyhedral links is the characterization and classification of the topologies of these interlocking molecules of metal-peptide rings.

4. Classification of Polyhedral Links

In this section, we consider the classification of polyhedral links. The main results of this article are Theorems 1–3. Two links in are equivalent or same if there is a homeomorphism sending one to the other. Here, we consider that the mirror image is equivalent to the original link. In [27], it is shown that some polyhedral links share the same topology even if different methods obtain them.

Proposition 3

([27]). Each pair or triple of polyhedral links are equivalent:

- 1.

- A type-B tetrahedral link and a type-C cuboctahedral link;

- 2.

- A type-B cubic link, a type-B octahedral link, and a type-C rhombicuboctahedral link;

- 3.

- A type-B dodecahedral link, type-B icosahedral link, and a type-C rhombicosidodecahedral link.

However, most polyhedral links are different, even if they share the same number of components and crossings. Here, we will show the following theorem.

Theorem 1.

Let P be a polyhedron.

Then, alternating polyhedral links of P of type A and type B are inequivalent links with the same number of crossings.

If the degree of each vertex of P is 3, then, from Theorem 1 and Proposition 1, we have the following:

Theorem 2.

Let P be a polyhedron with degree 3 at each vertex. Then, alternating polyhedral links of P of type A and type B are inequivalent links with the same number of components and crossings.

In [19], tetrahedral links of type A and type B are shown to be inequivalent by calculating link invariants. Theorem 2 gives another proof of this fact. Applying Theorem 2, we can show that type-A and type-B polyhedral links of a cube, a dodecahedron, an icosahedron, a truncated tetrahedron, a truncated octahedron (Figure 2), a truncated cube, a truncated icosahedron, a truncated dodecahedron, a truncated cuboctahedron, and a truncated icosidodecahedron are pairwise inequivalent. See Table 1 and Table 2.

Next, we consider type-A and type-B polyhedral links of different polyhedra.

Theorem 3.

The following pairs of polyhedral links are inequivalent but have the same number of components and crossings:

- 1.

- A type-A cubic link and a type-B octahedral link;

- 2.

- A type-A dodecahedral link and a type-B icosahedral link;

- 3.

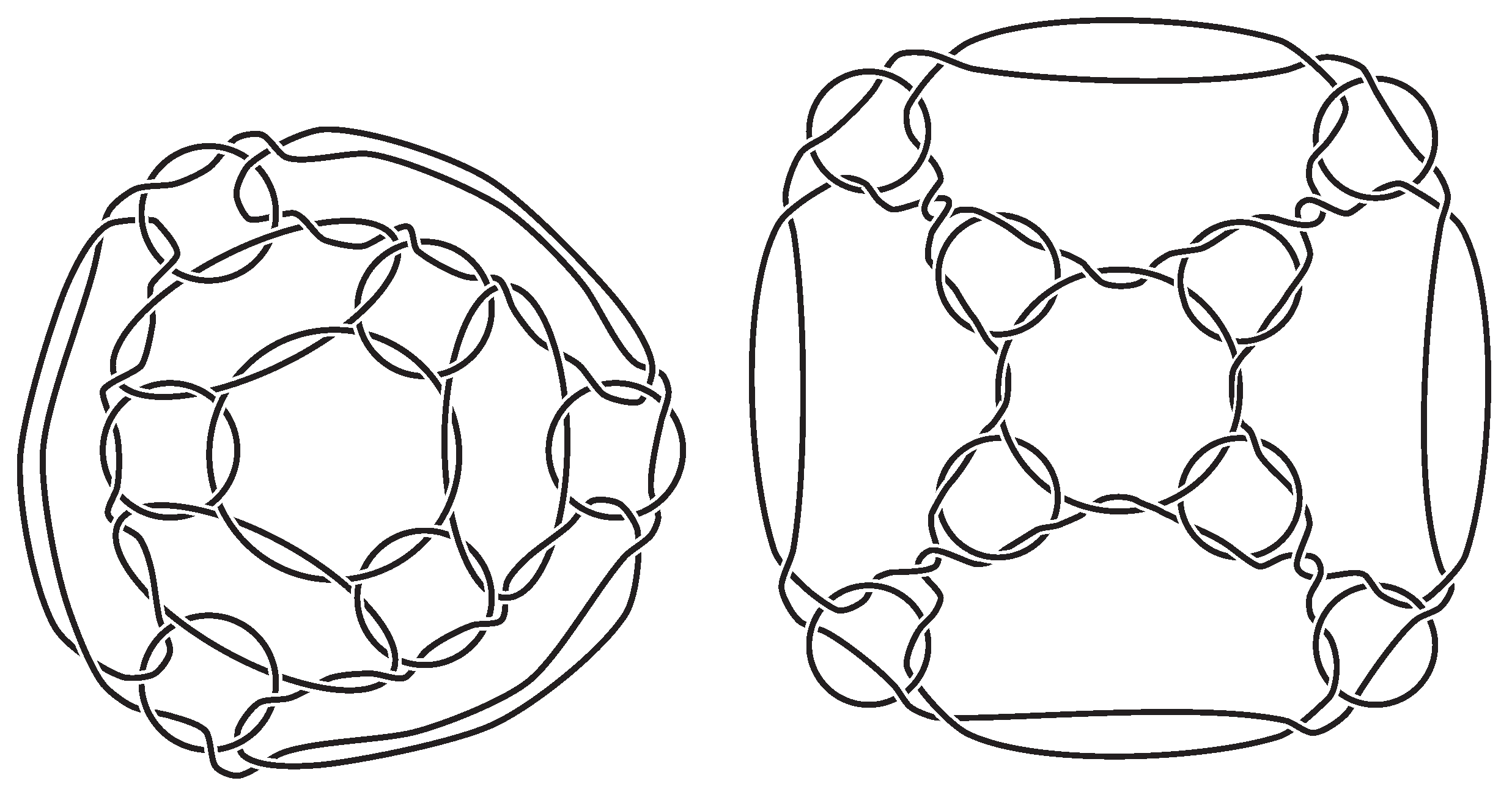

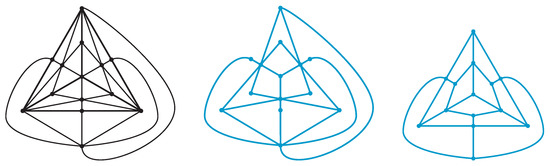

- A type-A truncated octahedral link and a type-A truncated cubic link. (See Figure 4);

Figure 4. (Left) type-A truncated octahedral link. (Right) type-A truncated cubic link (truncated hexahedral link). They are inequivalent links with the same numbers of components (14) and crossings (72).

Figure 4. (Left) type-A truncated octahedral link. (Right) type-A truncated cubic link (truncated hexahedral link). They are inequivalent links with the same numbers of components (14) and crossings (72). - 4.

- A type-A truncated octahedral link and a type-B truncated cubic link;

- 5.

- A type-A truncated cubic link and a type-B truncated octahedral link;

- 6.

- A type-A truncated icosahedral link and type-B truncated dodecahedral link;

- 7.

- A type-A truncated dodecahedral link and type-B truncated icosahedral link.

Theorems 1 and 3 are proved in Section 5.

5. Proof of Theorems 1 and 3

In this section, we show that alternating link diagrams of polyhedral links do not admit nontrivial flypes. First, we start by explaining the classification of alternating links.

5.1. Alternating Diagrams and Flypes

In this section, we review the classification of alternating links by Menasco and Thistlethwaite [28]. First, we will introduce the flype operation.

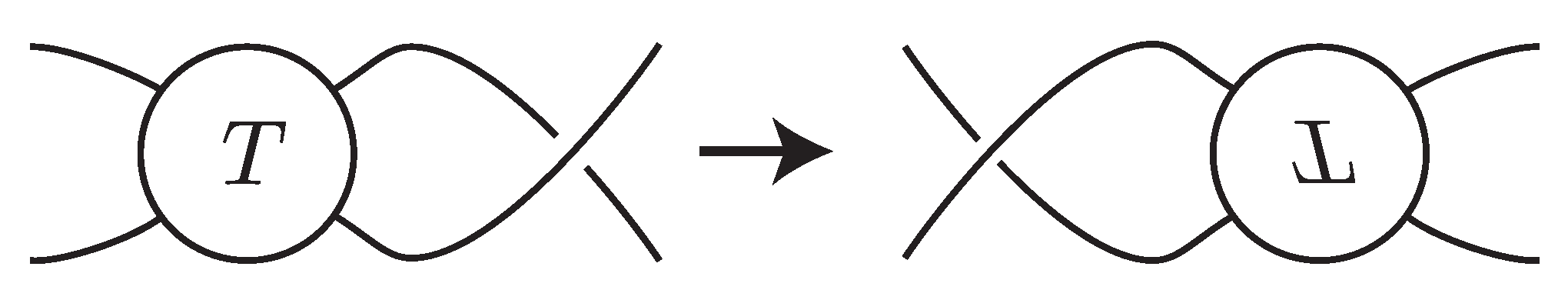

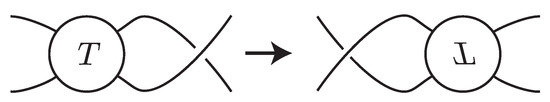

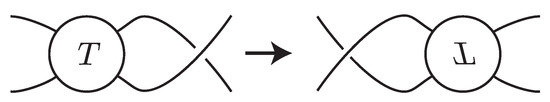

Definition 4.

A flype is an operation of link diagrams as in Figure 5. The tangle diagram T that is a part of the link diagram is turned over by a rotation of 180 degrees around a horizontal axis. A flype is nontrivial if the obtained diagram is different from the original one.

Figure 5.

A flype operation on a link diagram. A flype keeps the crossing number of the diagram.

If a flype is applied to an alternating diagram, the obtained diagram is also alternating.

A link diagram is reduced if it does not contain a nugatory crossing as in Figure 6A. A link diagram D is prime if each circle on meeting D in two points bounds a pair of a disk and a trivial arc. Otherwise, it is called a composite diagram. See Figure 6B.

Figure 6.

(A) A nugatory crossing; (B) a composite diagram.

Since a standard alternating diagram is reduced by its construction, it attains the minimal crossing number of the polyhedral link [30,31,32].

On the classification of alternating links, Menasco and Thistlethwaite gave the affirmative answer of the Tait flyping conjecture in [28].

Theorem 4

([28]). Let and be reduced, prime, oriented, alternating diagrams of a link. Then, can be transformed to by a finite sequence of flypes and an isotopy of .

Note that the alternating diagrams obtained by the definitions of polyhedral links in this article are reduced and prime.

5.2. Rigidity of Alternating Link Diagrams of Polyhedral Links

We define rigid alternating diagrams.

Definition 5.

An alternating link diagram is called rigid if it does not admit nontrivial flypes.

The classification of links with reduced, prime, rigid alternating diagrams can be achieved by classifying diagrams. By Theorem 4, we have the following.

Proposition 4.

Let and be reduced, prime, rigid alternating link diagrams on . Then, and represent equivalent links if and only if can be transformed into by an isotopy of and taking the mirror image, if necessary.

We will show the following two propositions in the next subsection. These propositions show the stability of polyhedral link structures.

Proposition 5.

The standard alternating diagram of a type-A alternating polyhedral link is rigid.

Proposition 6.

The standard alternating diagram of a type-B alternating polyhedral link is rigid.

5.3. Dual Graphs of Polyhedral Link Diagrams

In [33], the search of nontrivial flypes was performed using dual graphs of link diagrams. We apply this method to standard alternating diagrams of polyhedral links. First, we start with the definition of dual graphs of link diagrams.

Definition 6

(See for example [33]). We consider a link projection as a 4-valent graph on , i.e., a graph with degree 4 at each vertex. The dual graph of that 4-valent graph is called the dual graph of a link diagram. The vertices of the dual graph correspond to the complementary regions of the link diagram. Two vertices of the dual graph are connected by an edge if the corresponding regions share a segment of the link diagram.

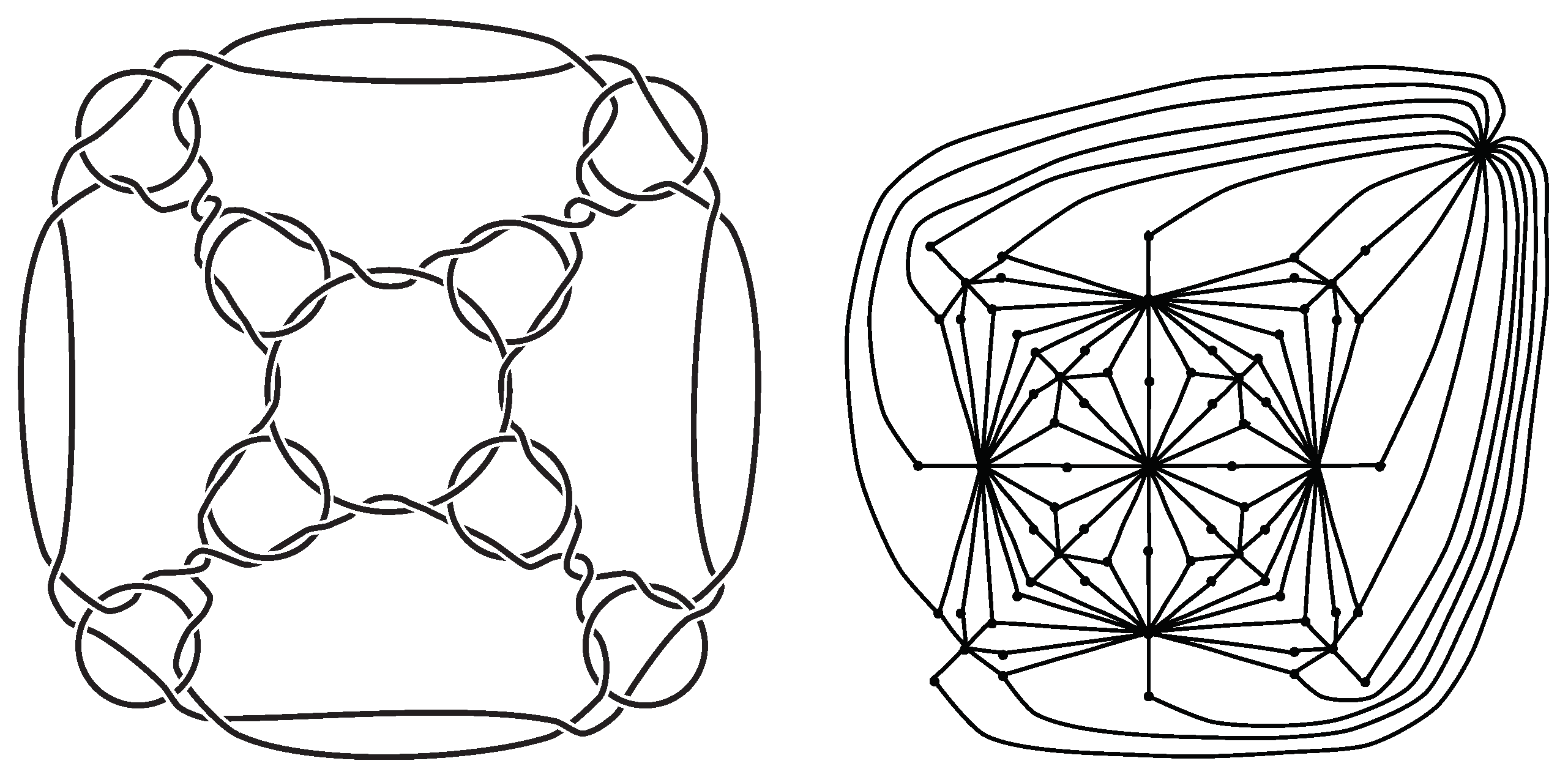

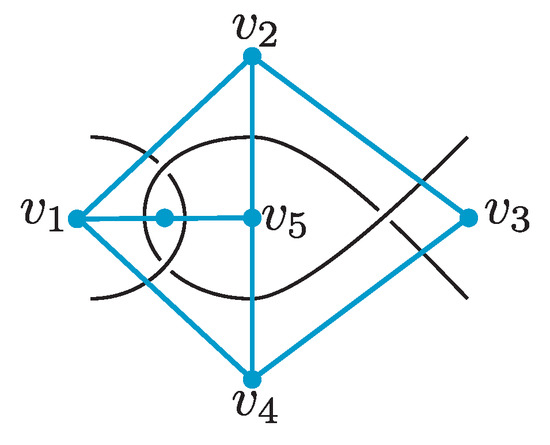

See Figure 7 for an example of a link diagram and its dual graph.

Figure 7.

A type-A truncated cubic link diagram and its dual graph.

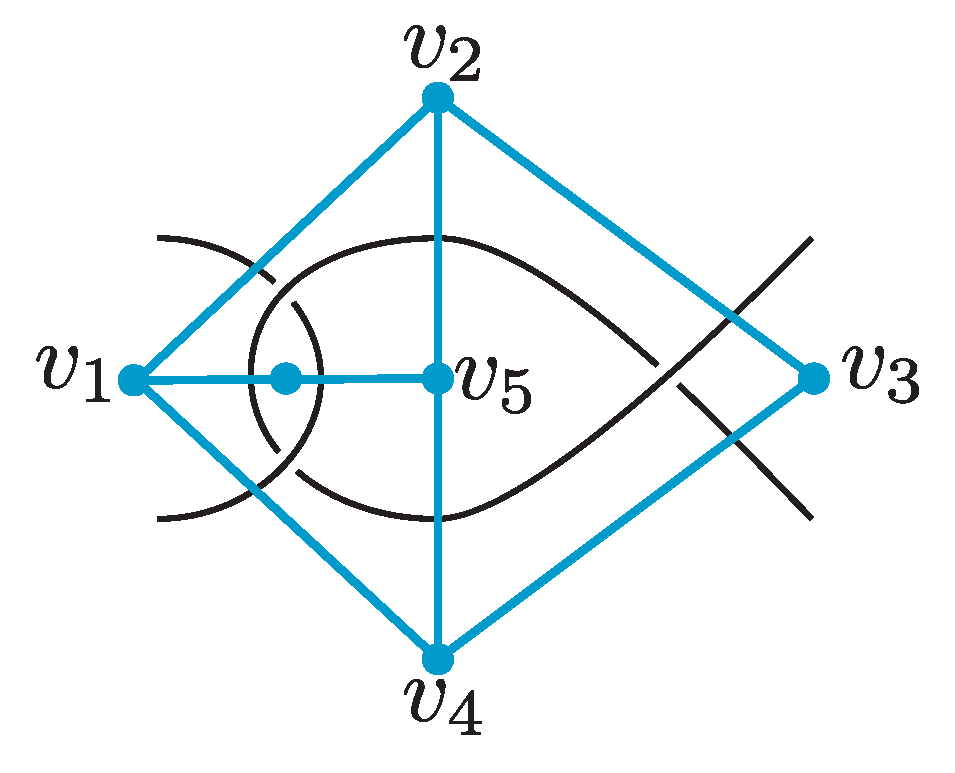

Next, we define nested 4-cycles of dual graphs.

Definition 7

([33]). Let , and be distinct vertices in the dual graph of an alternating link diagram. Let , , and be three 4-cycles in the dual graph. They are called nested 4-cycles if they satisfy the following conditions:

- 1.

- The disk bounded by an inner 4-cycle contains exactly one crossing of the link diagram.

- 2.

- The disk bounded by another inner 4-cycle contains other vertices of the dual graph.

- 3.

- The outer 4-cycle bounds the disk .

See Figure 8 for an example of nested 4-cycles. The following argument is contained in Section 5 in [33].

Figure 8.

Nested 4-cycles consist of the outer 4-cycle and two inner 4-cycles and . The inner 4-cycle bounds a disk containing one crossing of the link diagram, and the other inner 4-cycle bounds a disk containing at least one vertex of the dual graph.

Proposition 7

([33]). An alternating link diagram admits a nontrivial flype if and only if the dual graph contains nested 4-cycles.

Hence, if the dual graph does not contain nested 4-cycles, the alternating link diagram is rigid.

Proposition 8.

The dual graph of the diagram of a type-A polyhedral link of a polyhedron P is obtained from the barycentric subdivision of P by deleting edges on the 1-skeleton of P.

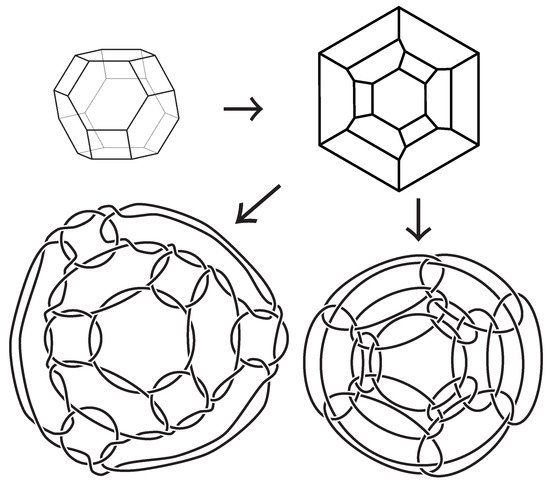

See Figure 9 for the barycentric subdivision of a polyhedron.

Figure 9.

Left: The barycentric subdivision of the tetrahedron P. The barycentric subdivision is obtained by P by adding the vertices corresponding to the centers of faces and the midpoints of edges of P and edges as in the figure. See, for example, ref. [34] for the detail. Center: The dual graph of the alternating diagram of a type-A tetrahedral link. It is obtained from the barycentric subdivision of P by deleting edges on the 1-skeleton of P. Right: The dual graph of the alternating diagram of a type-B tetrahedral link. It is obtained from the barycentric subdivision of P by deleting edges connecting vertices of P and the center of faces.

Proof.

By the construction of a type-A polyhedral link, each of the vertices, the midpoints of edges, and the centers of faces of P corresponds to a vertex of the dual graph. An edge of the dual graph connects a vertex corresponding to the center of a face and a vertex corresponding to the midpoint of an edge. See Figure 9 (center). □

Proof of Proposition 5.

Let P be the polyhedron. By Proposition 8, the dual graph is obtained from the barycentric subdivision of P by deleting edges on the 1-skeleton of P. Then, each 4-cycle of the dual graph satisfies one of the following:

- It contains vertices corresponding to two centers of faces, one midpoint of an edge, and a vertex of P.

- It contains vertices corresponding to two centers of faces and two vertices of P.

It is easy to see that there are no nested 4-cycles in the dual graph. □

Proposition 9.

The dual graph of the diagram of a type-B polyhedral link of a polyhedron P is obtained from the barycentric subdivision of P by deleting edges connecting a vertex of P and a vertex corresponding to the center of a face of P.

Proof.

By the construction of a type-B polyhedral link, each of the vertices, the midpoints of edges, and the center of faces of P corresponds to a vertex of the dual graph. An edge of the dual graph connects a vertex corresponding to the center of a face and a vertex corresponding to the midpoint of an edge, or a vertex corresponding to a vertex of P and a vertex corresponding to the midpoint of an edge. See Figure 9 (right). □

Proof of Proposition 6.

Let P be the polyhedron. By Proposition 9, the dual graph is obtained from the barycentric subdivision of P by deleting edges connecting a vertex of P and a vertex corresponding to the center of a face of P. Then, each 4-cycle of the dual graph contains vertices corresponding to the center of a face, two midpoints of edges, and a vertex of P. It is easy to see that there are no nested 4-cycles in the dual graph. □

Now, we will give the proofs of Theorems 1 and 3.

Proof of Theorem 1.

Let e denote the number of edges of P. Then, is equal to the sum of the degrees of vertices of P. By Proposition 1, a type-A polyhedral link of P and a type-B polyhedral link of P have the same crossing numbers.

By Propositions 5 and 6, the standard alternating diagram of each polyhedral link is rigid. The regions of a type-A polyhedral link diagram contain 2-gons on edges of P. On the other hand, no region of the standard diagram of a type-B polyhedral link is a 2-gon. Hence, these standard alternating diagrams are different. Therefore, by Proposition 4, those links are not equivalent. □

Proof of Theorem 3.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Nowadays, the topological property of chemical systems is discussed in many works. See, for example, refs. [35,36]. The topological structure of knots, links, and spatial graphs cause chirality and topological isomers [11,12] and changes the radius of gyration of cyclic polymers [37]. A spatial graph, a generalization of the concept of a knot or a link, is a realization of a graph in three-dimensional space. Multicyclic polymers have spatial graph structures [35].

In this paper, we studied the classification of polyhedral links using the affirmative answer of the Tait flyping conjecture. Our results (Theorems 1–3) provide a geometric topological proof for showing that the interlocking molecules of metal-peptide rings have different topologies. They also give a method for producing different links with the same number of crossings and components. In Propositions 5 and 6, we showed that these structures cannot be modified by flypes. The chemical interpretation of these results is that they demonstrate the stability of the capsule structure made by alternating polyhedral links. These structures are very intricately woven and therefore highly stable.

A polyhedral link is also considered to be a good structure for achieving capsule structures with a huge cavity. Structures of large cavities play essential roles in biological functions. The shell structure of the HK97 virus capsid [38] is an example of such structure. In [20], it is shown that the metal-peptide type-A cubic link provides an isolated cavity of 3200 Å. Our results suggest that the same construction using a larger polyhedron will produce a larger structure with similar properties, such as stabilities. For example, larger polyhedral links in Table 1 and Table 2 would give larger cavities.

We hope the method of creating polyhedral links gives a hint for the future creation of topologically different interlocking structures that share some good properties.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.S.; methodology, K.S.; validation, N.W. and K.S.; formal analysis, N.W. and K.S.; investigation, N.W. and K.S.; resources, K.S.; writing—original draft preparation, N.W. and K.S.; writing—review and editing, K.S.; visualization, N.W. and K.S.; supervision, K.S.; project administration, K.S.; funding acquisition, K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Nos. JP16H03928 and JP21H00978.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The second author would like to express his gratitude to his students, Kaoru Yoshino, Naoshi Ino, Naoka Wakamatsu, Akihiro Tashiro, and Yuki Endo, for helpful discussions on this project. The picture of the truncated octahedron in Figure 2 was produced by Jun Mitani at Tsukuba University. We would like to express our thanks to the referees for their helpful comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bates, A.D.; Maxwell, A. DNA Topology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Arsuaga, J.; Vazquez, M.; Trigueros, S.; Roca, J. Knotting probability of DNA molecules confined in restricted volumes: DNA knotting in phage capsids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 5373–5377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arsuaga, J.; Vazquez, M.; McGuirk, P.; Trigueros, S.; Roca, J. DNA knots reveal a chiral organization of DNA in phage capsids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 9165–9169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimokawa, K.; Ishihara, K.; Grainge, I.; Sherratt, D.J.; Vazquez, M. FtsK-dependent XerCD-dif recombination unlinks replication catenanes in a stepwise manner. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 20906–20911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stolz, R.; Yoshida, M.; Brasher, R.; Flanner, M.; Ishihara, K.; Sherratt, D.J.; Shimokawa, K.; Vazquez, M. Pathways of DNA unlinking: A story of stepwise simplification. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulkowska, J.I.; Rawdon, E.J.; Millett, K.C.; Onuchic, J.N.; Stasiak, A. Conservation of complex knotting and slipknotting patterns in proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, E1715–E1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamroz, M.; Niemyska, W.; Rawdon, E.J.; Stasiak, A.; Millett, K.C.; Sulkowski, P.; Sulkowska, J.I. KnotProt: A database of proteins with knots and slipknots. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 43, D306–D314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabrowski-Tumanski, P.; Rubach, P.; Goundaroulis, D.; Dorier, J.; Sulkowski, P.; Millett, K.C.; Rawdon, E.J.; Stasiak, A.; Sulkowska, J.I. KnotProt 2.0: A database of proteins with knots and other entangled structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 47, D367–D375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleckner, D.; Irvine, W.T.M. Creation and dynamics of knotted vortices. Nat. Phys. 2013, 9, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murasugi, K. Knot Theory and Its Applications; Birkhäuser: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Flapan, E. When Topology Meets Chemistry; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Flapan, E. Knots, Molecules, and the Universe; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, C.C. The Knot Book; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cromwell. Knots and Links; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kawauchi, A. (Ed.) A Survey of Knot Theory; Birkhäuser Verlag: Basel, Switzerland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- KnotPlot. Available online: https://www.knotplot.com (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Scharein, R.G. Interactive Topological Drawing. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Sawada, T.; Yamagami, M.; Ohara, K.; Yamaguchi, K.; Fujita, M. Peptide [4]catenane by folding and assembly. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 4519–4522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, T.; Saito, A.; Tamiya, K.; Shimokawa, K.; Hisada, Y.; Fujita, M. Metal-peptide rings form highly entangled topologically inequivalent frameworks with the same ring- and crossing-numbers. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, T.; Inomata, Y.; Shimokawa, K.; Fujita, M. A metal-peptide capsule by multiple ring threading. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inomata, Y.; Sawada, T.; Fujita, M. Metal-peptide torus knots from flexible short peptides. Chem 2020, 6, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inomata, Y.; Sawada, T.; Fujita, M. Metal-peptide nonafoil knots and decafoil supercoils. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 16734–16739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawada, T.; Fujita, M. Folding and assembly of metal-linked peptidic nanostructures. Chem 2020, 6, 1861–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, T.; Fujita, M. Orderly entangled nanostructures of metal-peptide strands. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2021, 94, 2342–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.-Y.; Zhai, X.-D.; Qiu, Y.-Y. Architecture of Platonic and Archimedean polyhedral links. Sci. Chin. Ser. B Chem. 2008, 51, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Zhai, X.-D.; Lu, D.; Qiu, W.-Y. The architecture of Platonic polyhedral links. J. Math. Chem. 2009, 46, 592–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Hu, G.; Qiu, Y.-Y.; Qiu, W.-Y. Topological transformation of dual polyhedral links. Match Commun. Math. Comput. Chem. 2010, 63, 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Menasco, W.; Thithlethwaite, M. The classification of alternating links. Ann. Math. 1993, 138, 113–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cromwell, P.R. Polyhedra; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman, L.H. State models and the Jones polynomial. Topology 1987, 26, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murasugi, K. Jones polynomials and classical conjectures in knot theory. Topology 1987, 26, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thistlethwaite, M.B. A spanning tree expansion of the Jones polynomial. Topology 1987, 26, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howards, H.; Li, J.; Liu, X. An infinite family of knots whose hexagonal mosaic number is only realized in non-reduced projections. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.03697v1. [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher, A. Algebraic Topology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Shimokawa, K.; Ishihara, K.; Tezuka, Y. Topology of Polymers; Springer Briefs in the Mathematics of Materials; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Orek, C.; Gündüz, B.; Kaygili, O.; Bulut, N. Electronic, optical, and spectroscopic analysis of TBADN organic semiconductor: Experiment and theory. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2017, 678, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uehara, E.; Deguchi, T. Knotting probability of self-avoiding polygons under a topological constraint. J. Chem. Phys. 2017, 147, 094901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikoff, W.R.; Liljas, L.; Duda, R.L.; Tsuruta, H.; Hendrix, R.W.; Johnson, J.E. Topologically linked protein rings in the bacteriophage HK97 capsid. Science 2000, 289, 2129–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).