Abstract

The invention of electronic mail (e-mail) has made communication through the Internet easier than before. However, because the fundamental functions of the Internet are built on opensource technologies, it is critical to keep all transmitted e-mail secure and secret. Most current e-mail protocols only allow recipients to check their e-mail after the recipients are authenticated by the e-mail server. Unfortunately, the subsequent e-mail transmission from the server to the recipient remains unprotected in the clear form without encryption. Sometimes, this is not allowed, especially in consideration of issues such as confidentiality and integrity. In this paper, we propose a secure and practical e-mail protocol with perfect forward secrecy, as well as a high security level, in which the session keys used to encrypt the last e-mail will not be disclosed even if the long-term secret key is compromised for any possible reason. Thus, the proposed scheme benefits from the following advantages: (1) providing mutual authentication to remove the threat of not only impersonation attacks, but also spam; (2) guaranteeing confidentiality and integrity while providing the service of perfect forward secrecy; (3) simplifying key management by avoiding the expense of public key infrastructure involvement; and (4) achieving lower computational cost while meeting security criteria compared to the related works. The security analysis and the discussion demonstrate that the proposed scheme works well.

1. Introduction

Electronic mail (e-mail, for short) is regarded as the most widely used mode of communication over the Internet across all architectures and vendor platforms. Users expect to exchange messages directly or indirectly via e-mail protocol. E-mail differs from traditional media in terms of the communication, storage, and retrieval of information [1]. Furthermore, e-mail has been regarded as a rich and dependable medium, from which organizations and telecommunications workers [2,3] may benefit [1]. With the security of e-mail communication in mind, there is a growing demand for not only confidentiality, but also authentication, in order to avoid worm viruses [4] and junk mail [5,6,7].

It is worthwhile to note that the most popular and common e-mail applications—i.e., POP3-based and web-based e-mail clients—are configured to send e-mail in the form of clear text. Although legal users are indeed authenticated by having to input their corresponding accounts and passwords when they log in to the e-mail servers, this does not mean that the sent e-mail will be encrypted for delivery to the recipients. This observation implies the need for a secure e-mail protocol. In fact, considering the security threats [8]—such as viruses, Trojan horses, etc.—posed by received e-mail, a large number of e-mail recipients refuse to open e-mail and/or attachments.

Given the storage-and-forwarding nature of e-mail on the e-mail server side, it is important to consider that the sender and the recipient might not be online at the same time. Therefore, the most cited handshaking method, which assures that both participants share the same key, is not practical. The storage-and-forwarding nature introduces the heavy cost of maintaining a public key infrastructure (PKI) [9] environment.

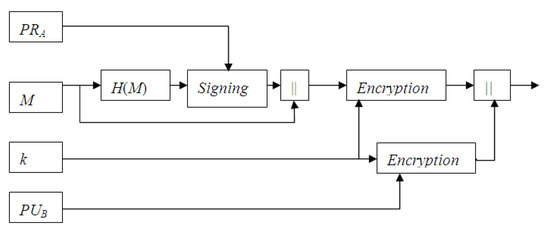

Compared to other Internet applications, the effort of researching secure e-mail protocols is minor in both industry and academia. In industry, there are two algorithms widely known as candidates of secure e-mail protocols [10]: Pretty Good Privacy (PGP) [11], and Security/Multipurpose Internet Mail Extension (S/MIME) [12,13]. PGP is freely available software written by Philip Zimmermann for e-mail security. It includes a hybrid cryptosystem that uses public key cryptography (RSA [14]) for key management and secret key cryptography (IDEA [15]) for data encryption. S/MIME is the other Internet standard to ensure e-mail security, incorporating the same functionality as PGP. Figure 1 briefly shows their processes.

Figure 1.

The common e-mail protocol, with confidentiality and authentication.

In order to achieve authentication, the digital signature service provided by PGP is as follows:

The sender A computes the signature (the used notations are described in the first table below). In order to achieve confidentiality, the above message is encrypted. The sender computes the ciphertext which is appended with . Finally, is sent to the recipient B. The recipient B obtains the message encryption key k by decrypting using his/her private key PRB to decrypt . With the signature , the recipient can verify the integrity and the origin of message M.

If the long-term secret key of the recipient is compromised, all previously used short-term secret keys will be disclosed in such a way that all past corresponding e-mails will be readable. Some research has therefore been conducted to provide a strong e-mail protocol to guarantee perfect forward secrecy (PFS).

In 2005, Sun et al. [16] proposed two strong-security e-mail protocols with PFS. Unfortunately, Dent [17] pointed out that the second protocol in Sun et al.’s schemes failed to provide the PFS service as claimed. Subsequently, Phan’s cryptanalysis in [18] showed that replay attacks and unknown key-share attacks did take place in both Sun’s first and second protocols. Furthermore, Kim et al. [19] proposed a further two robust protocols with PFS, in which the additional short-term key is generated by Diffie–Hellman key exchange. The authors claimed that the exposure of the long-term key would not disclose the secrecy of the previous session keys. Unfortunately, in 2007, Yoon and Yoo [20] pointed out that the second protocol of Kim et al.’s schemes was susceptible to sender impersonation and server impersonation attacks. Recently, Zhang and Hua proposed a new ID-based authenticated e-mail protocol with PFS [21]. Unfortunately, their scheme employed pairing computations in both the sending and receiving phases. As has been demonstrated, it is not a good idea to perform bilinear pairings via mobile device [22]. In 2015, Toorani [23] presented the cryptanalysis of a new, widely used e-mail protocol with PFS proposed by Chen and Wu [24], showing that Chen and Wu’s scheme is vulnerable to some password-related attacks, and fails to provide PFS. Furthermore, Kang and Xu [25] mentioned that the protocol of Chen and Wu [24] suffered from several security weaknesses, and proposed an improved e-mail scheme using PFS.

1.1. Motivation

According to the abovementioned observations, the design guidelines of a secure e-mail protocol are highlighted below:

- Storage-and-forwarding: The practical design of a secure e-mail protocol should take into account its storage-and-forwarding nature.

- Confidentiality: The content of e-mail should be transmitted over public networks in the form of ciphertext using a one-time-use key.

- Integrity: The integrity of e-mail content is guaranteed by generating the authentication message via a message authentication code (MAC) function [9], or by computing the signature with the sender’s private key.

- Authentication: The identities of the sender and the recipient should be mutually confirmed in order to remove the threat of false impersonation attacks. Sometimes, the e-mail server should authenticate the sender in such a way that the spam will be deterred effectively, and the recipient must be authenticated prior to receiving the e-mail.

- Perfect forward secrecy: It is critical to provide a PFS service to the security-sensitive applications of e-mail.

1.2. Contribution

In this paper, the authors propose a secure and practical e-mail protocol with PFS, while taking into account the abovementioned design guidelines. The e-mail server shoulders the responsibilities of both authenticating and helping to negotiate the session key shared between the sender and the recipient.

Compared with the abovementioned protocols, the main advantages of the proposed scheme are highlighted as follows:

- The mutual authentication among sender, recipient, and server removes the threats of not only impersonation attacks, but also spam.

- The confidentiality and integrity of the content of transmitted e-mail are guaranteed, while providing the service of PFS.

- The expense of involving the PKI, like all related schemes, is avoided in order to keep the key management simple.

- The proposed protocol not only achieves lower computational costs, but also satisfies more security criteria compared to existing protocols.

2. Preliminary

A Schnorr signature scheme [26] is a cryptosystem based on discrete logarithms [27]. In the Schnorr signature scheme, there is a large prime p and a primitive element g shared among a group of users. Each user randomly generates an integer x < p, called their private key, and calculates their related public key y as . The public key of the user is y and the private key is x. This technique employs a subgroup of order q in and a hash function h:{0,1} →.

The Schnorr signature scheme is reviewed as follows.

To sign a message M, the signer should do the following:

- Compute , where δ is a randomly chosen integer and .

- Compute e = h(M||r).

- Solve s ≡ xe +δ mod q.

The signature for M is the pair (e, s). To verify the signature (e, s), the verifier should do the following:

- Obtain the signer public key (p, q, g, y).

- Compute r’.

- Compute e’ = h(M||r’).

- Accept the signature if, and only if, e’ = e.

3. The Proposed Scheme

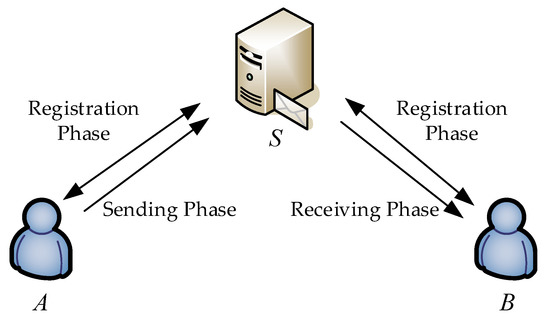

The proposed e-mail protocol with PFS is composed of three phases—the registration phase, the sending phase, and the receiving phase—as shown in Figure 2. For simplicity, two communication parties A and B and the trusted e-mail server S participate in the protocol. First, some notations shown in Table 1 are used to make the proposed protocol easier to understand.

Figure 2.

The three phases in the proposed scheme.

Table 1.

Notations used in the protocol.

Suppose that sender A must be a legal user of the e-mail server. Sending is allowed via the server only after a successful login process. Otherwise, the request will be rejected.

3.1. Registration Phase

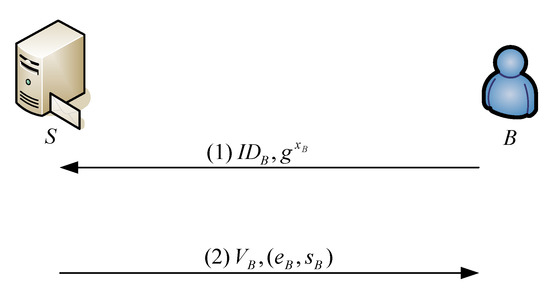

A user (for instance, B) must register to the e-mail server S in order to become a legal user before obtaining the related e-mail services. Figure 3 shows these processes.

Figure 3.

The processes in the registration phase.

- Step 1) B→ S: IDB,

User B selects a random number xB to compute and then sends (IDB, gxB) to S.

- Step 2) S→ B: VB, (eB, sB)

Upon receiving the message, S intends to share a secret VB with B by performing the following operations:

- Select a random number δB, where .

- Compute the master key VB = h(IDB, δB) for authentication of the identity of B later.

- Generate the Schnorr signature (eB, sB), as follows:

Finally, S delivers a smart card with VB, (eB, sB) to B via a secure pathway.

In order to check the validation of (eB, sB), user B obtains S’s public key PUS to retrieve rB’ as:

and then verifies the equality h(IDB, rB’)=eB. If it holds, B inputs xB into the smartcard.

Likewise, user A also possesses a smart card with VA, (eA, sA) and xA in the same way above. Note that S keeps the records (IDB,) and (IDA, ) for B and A, respectively.

3.2. Sending Phase

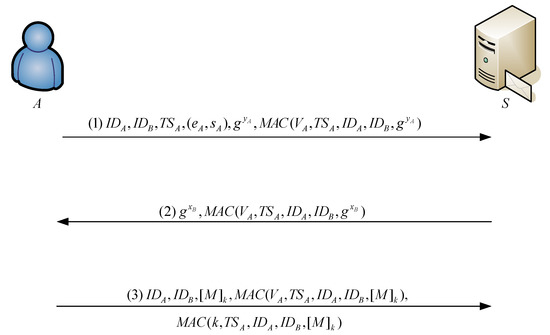

When user A intends to send e-mail M securely to user B, who is assumed to be offline, the detailed description is shown as follows (see also: Figure 4):

Figure 4.

The processes in the e-mail sending phase.

- Step 1) A→ S: IDA, IDB, TSA, (eA, sA),,

User A sends S a request message asking for e-mail service. The smartcard selects a random number yA to compute and , where TSA is the current timestamp. Then A sends S the message (IDA,IDB,TSA,eA,sA,,).

- Step 2) S→ A:,

When receiving the request sent by A, S first checks the freshness of TSA. If it holds, S authenticates A as follows.

- Use PRS to derive δA from the received (eA, sA) by solving as

- .

- Use the corresponding IDA to compute the master key .

- Use VA’ to compute and check whether the computed is equal to the received . If it holds, A is authenticated successfully by S.

S computes and sends to A.

- Step 3) A→ S:

Upon receiving the message, the smart card computes in order to confirm the integrity and origin of the received message. If it holds, the smart card confirms two things:

- The received message is fresh but not replayed because TSA is fresh.

- The identity of S is authenticated.

Then, the smart card computes the message encryption key . Accordingly, it computes three values: , and . Finally, it sends the message to the e-mail server S.

S first verifies the validation of by comparing the computed and the received . If the two are equivalent, S keeps the record (.

3.3. Receiving Phase

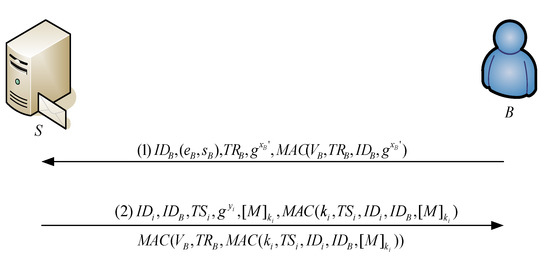

Note that we assume that more than one e-mail exists for B in the server. When user B intends to receive the e-mail—say M1, M2, …, Mn—from S, B must be authenticated by S, and the corresponding session keys k1,k2,…,kn should be constructed first. The detailed description is shown as follows (also see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The processes in the e-mail receiving phase.

Step 1) B→ S: IDB, (eB, sB), TRB,,

B sends S a request message (IDB, eB, sB, TRB,,), where xB’ is a nonce and TRB is the current timestamp.

Step 2) S→ B: ,

,

When receiving the request sent by B, S first checks the freshness of TRB. If it holds, S authenticates B as follows:

- PRS is used to derive from the received (eB, sB) by solving as

- .

- The corresponding IDB is used to compute the master key .

- is used to compute and check whether the computed is equal to the received . If it holds, B is authenticated successfully by S.

Then, S sends B all of the e-mail , and , where i indicates all of the e-mail sent to B. Note that S should replace with for the next round.

Finally, B computes the session key to check the validation of the received messages by comparing the computed and the received . If equivalent, the origin and integrity of the e-mail messages sent to B are confirmed. The session key ki is also confirmed, and B obtains the content of e-mail Mi by decrypting using ki. If the validation of the received is verified successfully, S is authenticated by B. Note that B should replace xB with xB’ for the next round.

4. Security Analysis

The security issues of the proposed protocol encompass four main services: confidentiality, integrity, authentication, and PFS. Confidentiality is the protection of transmitted e-mail from passive attacks, such as eavesdropping. In other words, confidentiality means keeping transmitted e-mail secret from illegal access by any but the authorized recipients. The most commonly used method is to encrypt e-mail using a secret key along with a public encryption algorithm. An integrity service then ensures that the e-mail is received without unauthorized modification. The authentication service is concerned with ensuring that the communication participants are authentic. Confirming the precise origin of the transmitted e-mail allows the recipient to know who sent the message. This confirmation implies that either of the two communication participants and the e-mail server can authenticate one another. PFS provides a high-level security service that is much more important for some security-sensitive applications.

Prior to the demonstration of security, some assumptions of security are made. We highlight the following facts providing proof of security. The discrete logarithm problem (DLP) and the Diffie–Hellman problem (DHP) [28] are two hard problems to solve in polynomial time, and the cryptographic hash function has collision-free and irreversible properties.

Assumption 1

(discrete logarithm assumption).The discrete logarithm problem (DLP) is defined so as to give a prime p, a generator g of the finite cyclic group Zp*, and an element, finding the integer a,, such that. The DLP assumption is that there is no feasible way of solving the DLP for all probabilistic polynomial time algorithms.

Assumption 2

(computational Diffie–Hellman assumption).The computational Diffie–Hellman (CDH) problem is defined so as to computegivenand, whereis a generator of the finite cyclic group,and. The CDH assumption is that there is no feasible way of solving the CDH problem for all probabilistic polynomial time algorithms.

Assumption 3

(one-way hash assumption). A one-way hash function is defined as a hash function that can take inputs of any size, and the resultant hash value should be fixed-sized. For any message m, it is easy to compute m’s hash value h(m). However, it is computationally infeasible to find a message m from its hash value h(m). The assumptions are as follows:

- For any message m1, it is computationally infeasible to find another message m2 such that h(m1) = h(m2).

- It is computationally infeasible to find a pair of different messages m1 and m2 such that h(m1) =h(m2).

It is reasonable to assume that the server is trustworthy for users, because a user only becomes legal after registering with the e-mail server by providing private information.

Proposition 1 (security of the master key).

The master key shared between a legal user and the e-mail server is kept secret.

Proof.

Considering the confidentiality of the user’s master key, the master key is a hashed value of the user’s identity and the random number—i.e., VB = h(IDB, δB)—selected for user B. In order to deduce the master key, the attacker would have to know δB in order to compute the master key VB. In order to succeed, the attacker must try to derive δB from the ordinary Schnorr signature (eB, sB). Nevertheless, solving the well-known DLP is believed to be infeasible in polynomial time (Assumption 1). □

Proposition 2 (confidentiality).

The protocol provides confidentiality of the transmitted e-mail by keeping the encryption key secret.

Proof.

It is crucial for users to keep the encryption key secret from outsiders in order to ensure the confidentiality of the content of e-mail. The encryption key is a hashed value of the timestamp TSA and . □

This implies that an attacker must have in order to deduce k. From the steps in the e-mail sending phase, an attacker could eavesdrop and in order to compute . Nevertheless, solving the well-known CDH problem is believed to be infeasible in polynomial time (Assumption 2). This implies that the confidentiality of e-mail is ensured, and that the session/encryption key is only shared between the sender and the recipient.

Proposition 3 (integrity).

The protocol ensures the integrity of the transmitted e-mail.

Proof.

In the proposed protocol, the integrity of the transmitted e-mail is guaranteed through the MAC function by either the master key or the session key. The following demonstrates that the attacker cannot modify the transmitted e-mail without knowing either the master key or the session key. □

Firstly, the integrity of transmitted between the sender A and the server S is verified by S; that is, S verifies the validation of using the computed master key VA by checking the MAC value, i.e.,. Since VA is shared between A and S, the attacker has no knowledge of VA (Proposition 1), and is therefore unable to forge the related MAC value.

Secondly, the integrity of transmitted between the recipient B and the server S is verified by B, as follows: B verifies the validation of using the computed session/encryption key ki by checking the MAC value, i.e., . Since ki is shared between A and B, the attacker will not know about ki (Proposition 2), and is therefore unable to forge the related MAC value.

These two observations above provide proof of the integrity of e-mail.

Proposition 4

(mutual authentication).The protocol provides mutual authentication between the sender A, the server S, and the recipient B.

Proof.

This proposition is analyzed from three perspectives: authentications among A, B, and S. □

Case 1: A and S

In order to authenticate A, S extracts the random number δA from (eA, sA), using their long-term secret key PRS to compute the master key VA. Accordingly, S verifies the identity of A by checking the MAC value, i.e.,. Based on the same reasoning as Proposition 3, A is authenticated by S. On the other hand, A must check the validity of in order to authenticate S. The MAC value is computed with the common master key. Only A and S know the common master key VA, and the attacker cannot counterfeit the authentication message to deceive A. Thus, mutual authentication between A and S is achieved.

Case 2: B and S

Likewise, the mutual authentication between B and S is shown below. Except for B and S, nobody knows the master key VB. Therefore, mutual authentication between B and S is achieved by verification of the validity of and by S and B, respectively.

Case 3: A and B

The server S shoulders the responsibility of assisting A and B in authenticating one another. A (resp. B) is satisfied with both the origin and the integrity of the received messages from Step 2 in the sending phase (resp. Step 2 in the receiving phase) from S. If the verification of the message from S holds, A (resp. B) is convinced that the origin of the received message (resp.) is B (resp. A), as only A/B knows the secret exponent yA/xB. The common session key can be generated by A/B as . Because the session key is only known by A and B, nobody can forge a valid .

In accordance with the above analyses, mutual authentication between S, A, and B is achieved.

Proposition 5 (perfect forward secrecy).

The proposed e-mail protocol provides the service of PFS.

Proof:

Perfect forward secrecy means that when the long-term keys of either side of the sender or the recipient are compromised, the previous short-term common session keys are still kept secret. The common session key shared between sender and recipient is constructed as . Assume that the attacker has intercepted and collected all messages transferred in past e-mail sessions; only and were obtained, but neither yA nor xB. If the long-term secret keys VA, VB, and PRS have been compromised, based on the difficulty of solving the DLP and the CDH hard problems, obtaining yA/xB or from to compute k is infeasible. In order to obtain the session key, the attacker must have the knowledge of yA or xB. In addition, the session keys generated to encrypt different e-mails are independent, since yA and xB are randomly chosen by A and B, respectively, in each run; that is, the attacker cannot know previous session keys even if they obtain the session key used in this run.

Proposition 6 (resistance to replay attacks).

The protocol ensures the freshness of the transmitted messages by removing the threat of replay attacks.

Proof.

A timestamp is involved in the MAC function in order to guarantee the freshness of the transmitted messages. Each participant can easily measure the time duration of the message traveling. Based on this knowledge, the freshness can be guaranteed by checking whether or not the time difference is acceptable. □

In the sending phase, all of the messages in the three steps are protected by involving TSA issued by the sender.

Furthermore, the freshness of all of the messages in the receiving phase is guaranteed by involving TRB issued by the recipient.

Table 2 summarizes the analyses of security and the comparison between the related works and the proposed scheme. Compared to the related works, the proposed scheme provides more security functionality, and is more secure against attacks.

Table 2.

Comparison of security functionality between the related works and the proposed scheme.

5. Discussion

In spite of demonstrating the security analysis, there are several valuable merits to be discussed, as follows:

5.1. Computional Efficiency

Prior to demonstrating the computational efficiency, some observations are highlighted:

- The e-mail server performs two linear operations to solve secret random numbers δA/δB in order to compute the shared master keys VA=h(IDA, δA)/VB=h(IDB, δB), and four (resp. three) operations for generating hash/MACs in the sending phase (resp. the receiving phase).

- The senders perform two modular exponential operations for preparing and computing a common session key , and five operations for hash/MACs. Furthermore, one secret-key operation is performed in order to compute [M]k.

- The recipients perform two modular exponential operations for preparing and computing a common session key , and four operations for hash/MACs. Furthermore, one secret-key operation is performed in order to decrypt [M]k.

As shown in [29], the speed of secret-key operations is about 100–1000 times faster than that of public-key operations, while the speed of hash-based operations is much faster than that of secret-key operations. Thus, public-key operations and modular exponentiation operations are computationally expensive.

Table 3 clearly indicates that the computational costs on the sender/recipient side and the e-mail server side are comparatively lighter than those of the related works. In client/server networks, the server can easily be inappropriately designed, and thus become a computational bottleneck involving heavy computational cost. The following characteristics are highlighted below:

Table 3.

Comparison of performance in e-mail sending and receiving phases between the related works and the proposed scheme.

- Server side: In the proposed protocol, the computational cost on the server side is significantly lighter than that of the related works. Compared to conventional PKI-based systems, in which the server has to handle huge computational overhead for each session, the e-mail server in our scheme merely treats efficient hashing operations in the phases of sending and receiving (see column 5 in Table 3). Although the generation of a Schnorr signature is required on the server during the registration phase, this is an infrequent task, and some supplementary measures—such as pre-computation or offline computation—can also be considered in order to improve overall performance.

- User side: The total computational cost required from the sender (resp. the recipient) in the proposed scheme is two (resp. two) exponentiation operations. This implies that the computational cost in the proposed scheme is lower than that of the related works.

5.2. Simple Key Management

Obviously, if the e-mail server maintains a security-sensitive database containing all users’ passwords or secret keys, it becomes the target of numerous attacks from networks. In general, schemes based on a secret-key- or password-based cryptosystems likely face this challenge (i.e., the secret key/password management problem) in such a way that it limits the scalability of the system. In the proposed protocol, there is no sensitive information stored centrally in the e-mail server. On the contrary, the master key used to authenticate the senders/recipients is dynamically computed by the e-mail server from the message (e, s), which is a form of Schnorr signature.

Compared with traditional PKI-based key exchange protocols, such as the DH protocol [28], the authenticated key exchange is provided without involving public key authentication based on PKI instead of the trusted third party, i.e., the e-mail server. This system does not demand the establishment of PKI. Hence, the burden of maintaining PKI is avoided. In summary, the key management is simple.

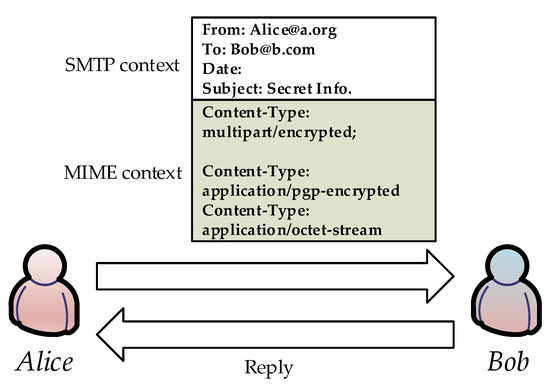

5.3. Implementation

Taking e-mail contexts into account, every e-mail generally has two contexts—the SMTP context, and the MIME context [10]—as shown in Figure 6. The former determines the communication pattern—i.e., sender and recipients—and the SMTP-related actions—e.g., reply and reply-all. The latter determines the rendering of the e-mail content, including the parsers for HTML, CSS, etc. Herein, the whole MIME is potentially protected, while the whole SMTP is kept public.

Figure 6.

E-mail context: (a) SMTP context; and (b) MIME context.

5.4. Further Disussions

The proposed protocol achieves the following advantages:

- Mutual authentication: Based on Proposition 4, the mutual authentication between sender, recipient, and server removes the threat of impersonation attacks and spam. This implies that the proposed protocol is an authenticated key exchange scheme.

- Confidentiality and Integrity: Based on Propositions 2 and 3, the confidentiality and integrity of the content of transmitted e-mail is guaranteed, while providing the service of PFS based on Proposition 5.

- Simple Key Management: Based on the analysis in Section 5.2, the expense of involving PKI, such as S/MIME-based and PGP-based PKI [10], is avoided in order to keep key management simple.

It is worthwhile to note that the proposed e-mail protocol benefits from providing PFS and avoiding expensive PKI maintenance costs compared with traditional e-mail protocols such as S/MIME and PGP.

5.5. Limitation

Since e-mail is one of the most popular communication tools, there are a variety of threats in the e-mail scenario, such as phishing attacks, spam mail, denial-of-service (DoS) attacks, and viruses. The proposed scheme, however, does not cover most of these practical concerns as long as the senders have been authenticated. For instance, spammers may obtain authentication following the scheme, and apply some technologies for the avoidance of spam detection systems; hence, spamming can still succeed. Fortunately, research and newer methods in terms of spam prevention are continuously under development, e.g., in [8], a spam-filtering system with an artificial backpropagation neural network (BPNN) is proposed in order to minimize the influence of spam. Moreover, the spread of viruses via the sending of malicious messages or attached files constitutes a similar problem, and the corresponding approach in [30] is proposed in order to optimally control virus propagation on the e-mail network.

6. Conclusions

While the security of e-mail is receiving considerable attention not only from academia, but also from industry, the proposed protocol guarantees the crucial security criteria. This includes confidentiality, integrity, mutual authentication, and PFS, without the introduction of expensive computational costs. It is worthwhile to note that since PKI is not required, key management thus becomes simple. Therefore, the proposed protocol is more secure and more practical than those currently in use. The major advantages include: (1) computational efficiency; (2) simple key management; and (3) satisfying more security criteria compared to similar existing schemes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.-H.C. and C.-D.L.; methodology, T.-H.C.; validation, T.-H.C. and C.-D.L.; formal analysis, T.-H.C.; investigation, T.-H.C. and C.-D.L.; writing—original draft preparation, T.-H.C. and C.-D.L.; writing—review and editing, C.-D.L.; project administration, C.-D.L.; funding acquisition, C.-D.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan under grant MOST 107-2221-E-415-001-MY3.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Higa, K.; Sheng, O.; Shin, B.; Figueredo, A. Understanding relationships among teleworkers’ e-mail usage, e-mail richness perceptions, and e-mail productivity perceptions under a software engineering environment. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2000, 47, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fritz, M.; Higa, K.; Narasimhan, S. Toward a telework taxonomy and test for suitability: A survey of the literature. J. Group Decis. Negot. 1995, 4, 311–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, A.I. The management, control, and evaluation of a telecommuting project: A case study. Inf. Manag. 1987, 13, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.C.; Towsley, D.; Gong, W. Modeling and simulation study of the propagation and defense of internet e-mail worms. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2007, 4, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghel, H. E-mail—The good, the bad, and the ugly. Commun. ACM 1998, 40, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Cranor, L.; Lamacchia, B.A. Spam! Commun. ACM 1998, 41, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R.J. How to avoid unwanted email. Commun. ACM 1998, 41, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maki, M.A.A.M.; Subramanian, S. Using an artificial neural network to improve email security. In Advances in Computational Intelligence and Robotics; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 131–145B. [Google Scholar]

- Schneier, B. Applied Cryptography, 2nd ed.; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Schwenk, J.; Brinkmann, M.; Poddebniak, D.; Müller, J.; Somorovsky, J.; Schinzel, S. Mitigation of attacks on email end-to-end encryption. In Proceedings of the 2020 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Virtual Event. 9–13 November 2020; pp. 1647–1664. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, P.R. The Official PGP User’s Guide; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J. S/MIME Message Specification–PKCS Security Services for MIME; RSA Data Security Inc.: Bedford, MA, USA, 1995; Available online: http://www.rsa.com/ (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Schaad, J.; Ramsdell, B.; Turner, S. Secure/Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions (S/MIME) Version 4.0 Message Specification, IETF, RFC 8551. Available online: https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc8551 (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Rivest, R.L.; Shamir, A.; Adleman, L. A Method for Obtaining Digital Signatures and Public-Key Cryptosystems. Commun. ACM 1978, 21, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, W. On the Security of the IDEA Block Cipher. Comput. Vis. 2001, 93, 371–385. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.M.; Hsieh, B.T.; Hwang, H.J. Secure e-mail protocols providing perfect forward secrecy. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2005, 9, 58–61. [Google Scholar]

- Dent, A. Flaws in an e-mail protocol of Sun, Hsieh, and Hwang. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2005, 9, 718–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, R.C.-W. Cryptanalysis of e-mail protocols providing perfect forward secrecy. Comput. Stand. Interfaces 2008, 30, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.H.; Koo, J.H.; Lee, D.H. Robust e-mail protocols with perfect forward secrecy. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2006, 10, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, E.; Yoo, K. Cryptanalysis of robust e-mail protocols with perfect forward secrecy. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2007, 11, 372–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Hua, H. An efficient identity-based authenticated email protocol with perfect forward secrecy. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Forum on Information Technology and Applications (IFITA), Kunming, China, 16–18 July 2010; pp. 68–71. [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith, S.; Paterson, K.G.; Smart, N.P. Pairings for cryptographers. Discret. Appl. Math. 2008, 156, 3113–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toorani, M. Cryptanalysis of a new protocol of wide use for email with perfect forward secrecy. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2014, 8, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.-H.; Wu, Y.-T. A new protocol of wide use for e-mail with perfect forward secrecy. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. C 2009, 11, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.; Xu, D. Perfect-Mail: A secure e-mail protocol with perfect forward secrecy. Br. J. Math. Comput. Sci. 2016, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnorr, C.P. Efficient signature generation by smart cards. J. Cryptol. 1991, 4, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mccurley, K.S. The discrete logarithm problem. Proc. Symp. Appl. Math. 1990, 42, 49–74. [Google Scholar]

- Diffie, W.; Hellman, M. New directions in cryptography. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1976, 22, 644–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RSA Laboratories. Frequently Asked Questions about Today’s Cryptography, V4.0. Available online: http://www.nordugrid.org/documents/rsalabs_faq41.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Xie, B.; Liu, M. Dynamics stability and optimal control of virus propagation based on the e-mail network. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 32449–32456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).