Abstract

In this study, we present the notion of the quasi-ordinarization transform of a numerical semigroup. The set of all semigroups of a fixed genus can be organized in a forest whose roots are all the quasi-ordinary semigroups of the same genus. This way, we approach the conjecture on the increasingness of the cardinalities of the sets of numerical semigroups of each given genus. We analyze the number of nodes at each depth in the forest and propose new conjectures. Some properties of the quasi-ordinarization transform are presented, as well as some relations between the ordinarization and quasi-ordinarization transforms.

1. Introduction

A numerical semigroup is a cofinite submonoid of under addition, where is the set of nonnegative integers.

While the symmetry of structures has traditionally been studied with the aid of groups, it is also possible to relax the definition of symmetry, so as to describe some forms of symmetry that arise in quasicrystals, fractals, and other natural phenomena, with the aid of semigroups or monoids, rather than groups. For example, Rosenfeld and Nordahl [1] lay the groundwork for such a theory of symmetry based on semigroups and monoids, and they cite some applications in chemistry.

Suppose that is a numerical semigroup. The elements in the complement are called the gaps of the semigroup and the number of gaps is its genus. The Frobenius number is the largest gap and the conductor is the non-gap that equals the Frobenius number plus one. The first non-zero non-gap of a numerical semigroup (usually denoted by m) is called its multiplicity. An ordinary semigroup is a numerical semigroup different from in which all gaps are in a row. The non-zero non-gaps of a numerical semigroup that are not the result of the sum of two smaller non-gaps are called the generators of the numerical semigroup. It is easy to deduce that the set of generators of a numerical semigroup must be co-prime. One general reference for numerical semigroups is [2].

To illustrate all these definitions, consider the well-tempered harmonic semigroup , where we use to indicate that the semigroup consecutively contains all the integers from the number that precedes the ellipsis. The semigroup H arises in the mathematical theory of music [3]. It is obviously cofinite and it contains zero. One can also check that it is closed under addition. Hence, it is a numerical semigroup. Its Frobenius number is 44, its conductor is 45, its genus is 33, and its multiplicity is 12. Its generators are .

The number of numerical semigroups of genus g is denoted . It was conjectured in [4] that the sequence asymptotically behaves as the Fibonacci numbers. In particular, it was conjectured that each term in the sequence is larger than the sum of the two previous terms, that is, for , with each term being increasingly similar to the sum of the two previous terms as g approaches infinity, more precisely and, equivalently, . A number of papers deal with the sequence [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Alex Zhai proved the asymptotic Fibonacci-like behavior of [21]. However, it remains unproven that is increasing. This was already conjectured by Bras-Amorós in [22]. More information on , as well as the list of the first 73 terms can be found in entry A007323 of The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences [23].

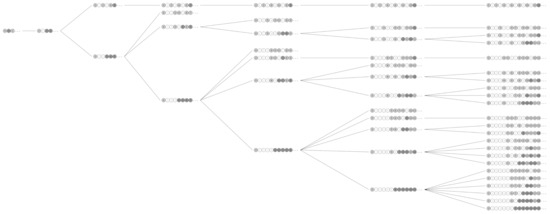

It is well known that all numerical semigroups can be organized in an infinite tree whose root is the semigroup and in which the parent of a numerical semigroup is the numerical semigroup obtained by adjoining to its Frobenius number. For instance, the parent of the semigroup is the semigroup . In turn, the children of a numerical semigroup are the semigroups we obtain by taking away the generators one by one that are larger than or equal to the conductor of the semigroup. The parent of a numerical semigroup of genus g has genus and all numerical semigroups are in , at a depth equal to its genus. In particular, is the number of nodes of at depth g. This construction was already considered in [24]. Figure 1 shows the tree up to depth 7.

Figure 1.

The tree up to depth 7. White dots refer to the gaps, dark gray dots to the generators and the light gray ones to the elements of the semigroups that are not generators.

In [9], a new tree construction is introduced as follows. The ordinarization transform of a non-ordinary semigroup with Frobenius number F and multiplicity m is the set . For instance, the ordinarization transform of the semigroup is the semigroup The ordinarization transform of an ordinary semigroup is then defined to be itself. Note that the genus of the ordinarization transform of a semigroup is the genus of the semigroup.

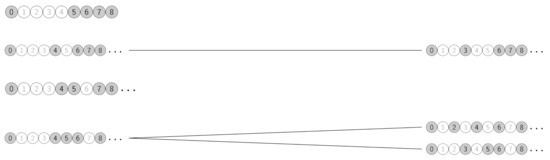

The definition of the ordinarization transform of a numerical semigroup allows the construction of a tree on the set of all numerical semigroups of a given genus rooted at the unique ordinary semigroup of this genus, where the parent of a semigroup is its ordinarization transform and the children of a semigroup are the semigroups obtained by taking away the generators one by one that are larger than the Frobenius number and adding a new non-gap smaller than the multiplicity in a licit place. To illustrate this construction with an example in Figure 2, we depicted .

Figure 2.

The whole tree .

One significant difference between and is that the first one has only a finite number of nodes. In fact, it has nodes, while is an infinite tree. It was conjectured in [9] that the number of numerical semigroups in at a given depth is at most the number of numerical semigroups in at the same depth. This was proved in the same reference for the lowest and largest depths. This conjecture would prove that .

In Section 2, we will construct the quasi-ordinarization transform of a general semigroup, paralleling the ordinarization transform. If the quasi-ordinarization transform is applied repeatedly to a numerical semigroup, it ends up in a quasi-ordinary semigroup. In Section 3, we define the quasi-ordinarization number of a semigroup as the number of successive quasi-ordinarization transforms of the semigroup that give a quasi-ordinary semigroup. Section 4 analyzes the number of numerical semigroups of a given genus and a given quasi-ordinarization number in terms of the given parameters. We present the conjecture that the number of numerical semigroups of a given genus and a fixed quasi-ordinarization number increases with the genus and we prove it for the largest quasi-ordinarization numbers. In Section 5, we present the forest of semigroups of a given genus that is obtained when connecting each semigroup to its quasi-ordinarization transform. The forest corresponding to genus g is denoted . Section 6 analyzes the relationships between , , and .

From the perspective of the forests of numerical semigroups here presented, the conjecture in Section 4 translates to the conjecture that the number of numerical semigroups in at a given depth is at most the number of numerical semigroups in at the same depth. The results in Section 4 provide a proof of the conjecture for the largest depths. Proving this conjecture for all depths, would prove that . Hence, we expect our work to contribute to the proof of the conjectured increasingness of the sequence (A007323).

2. Quasi-Ordinary Semigroups and Quasi-Ordinarization Transform

Quasi-ordinary semigroups are those semigroups for which and so, there is a unique gap larger than m. The sub-Frobenius number of a non-ordinary semigroup with Frobenius number F is the Frobenius number of .

The subconductor of a semigroup with Frobenius number F is the smallest nongap in the interval of nongaps immediatelly previous to F. For instance, the subconductor of the above example, , is 42.

Lemma 1.

Let Λ be a non-ordinary and non quasi-ordinary semigroup, with multiplicity m, genus g, and sub-Frobenius number f. Then, is another numerical semigroup of the same genus g.

Proof.

Since is already a numerical semigroup, it is enough to see that is not in , where F is the Frobenius number of . Notice that for a non-ordinary numerical semigroup, the difference between its Frobenius number and its sub-Frobenius number needs to be less than the multiplicity of the semigroup; hence, . So, the only option for to be in is that . In this case, any integer between 1 and must be a gap, since the integers between and are nongaps. In this case, would be quasi-ordinary, contradicting the hypotheses. □

Definition 1.

The quasi-ordinarization transform of a non-ordinary and non quasi-ordinary numerical semigroup Λ, with multiplicity m, genus g and sub-Frobenius number f, is the numerical semigroup .

The quasi-ordinarization of either an ordinary or quasi-ordinary semigroup is defined to be itself.

As an example, the quasi-ordinarization of the well-tempered harmonic semigroup used in the previous examples is

Remark 1.

In the ordinarization and quasi-ordinarization transform process, we replace the multiplicity by the largest and second largest gap, respectively, and we obtain numerical semigroups. In general, if we replace the multiplicity by the third largest gap, we do not obtain a numerical semigroup.

See for instance . Replacing 2 by 5, we obtain , which is not a numerical semigroup since is not in the set.

3. Quasi-Ordinarization Number

Next, lemma explicits that there is only one quasi-ordinary semigroup with genus g and conductor c where .

Lemma 2.

For each of the positive integers g and c with , the semigroup is the unique quasi-ordinary semigroup of genus g and conductor c.

The quasi-ordinarization transform of a non-ordinary semigroup of genus g and conductor c can be applied subsequently and at some step, we will attain the quasi-ordinary semigroup of that genus and conductor, that is, the numerical semigroup . The number of such steps is defined to be the quasi-ordinarization number of .

We denote by , the number of numerical semigroups of genus g and quasi-ordinarization number q. In Table 1, one can see the values of for genus up to 45. It has been computed by an exhaustive exploration of the semigroup tree using the RGD algorithm [12].

Table 1.

Number of semigroups of each genus and quasi-ordinarization number.

Lemma 3.

The quasi-ordinarization number of a non-ordinary numerical semigroup of genus g coincides with the number of non-zero non-gaps of the semigroup that are smaller than or equal to .

Proof.

A non-ordinary numerical semigroup of genus g is non-quasi-ordinary if and only if its multiplicity is at most . Consequently, we can repeatedly apply the quasi-ordinarization transform to a numerical semigroup while its multiplicity is at most . Furthermore, the number of consecutive transforms that we can apply before obtaining the quasi-ordinary semigroup is hence the number of its non-zero non-gaps that are at most the genus minus one. □

For a numerical semigroup , we will consider its enumeration , that is, the unique increasing bijective map between and . The element is then denoted . As a consequence of the previous lemma, for a numerical semigroup with quasi-ordinarization number equal to q, the non-gaps that are at most are exactly .

Lemma 4.

The maximum quasi-ordinarization number of a non-ordinary semigroup of genus g is .

Proof.

Let be a numerical semigroup with quasi-ordinarization number equal to q. Since the Frobenius number F is at most , the total number of gaps from 1 to is g, and so the number of non-gaps from 1 to is . The number of those non-gaps that are larger than is . On the other hand, are different non-gaps between g and . So, the number of non-gaps between g and is at least q. All these results imply that and so, .

On the other hand, the bound stated in the lemma is attained by the hyperelliptic numerical semigroup

□

We will next see that the maximum ordinarization number stated in the previous lemma is attained uniquely by the numerical semigroup in (1). To prove this result, we will need the next lemma. Let us recall that and that denotes the cardinality of A.

Lemma 5.

Consider a finite subset .

- The set contains at least elements

- If , the set contains exactly elements if and only if there exists a positive integer α such that for all .

- If , the set contains exactly elements if and only if either

- there exists a positive integer α such that for all i with and ,

- there exists a positive integer α such that for all i with .

Proof.

The first item stems from the fact that if , then must contain at least , which are all different.

The second item easily follows from the fact that if has elements, then must be exactly the set . Indeed, in this case, the increasing set must coincide with the increasing set , having as a consequence that and so, , and . Hence,

Similarly, one can show that and, so, . It equally follows that

For the third item, one direction of the proof is obvious, so we just need to prove the other one, that is, if the sum contains elements, then must be as stated.

We will proceed by induction. Suppose that and that the set contains exactly 8 elements. Since the ordered sequence

already contains 7 elements, then necessarily two of the elements coincide with one element in (2) and the third one is not in (2). So, at least one of and must be in (2).

Suppose first that is in (2). Then, necessarily , which means that . Hence, there exists (in fact, ) such that and . Now, the elements

are equally separated by the same separation . That is,

Additionally, the elements

are equally separated by the same separation . That is,

Furthermore, must contain all the elements in (3) and (4) as well as the element , which is not in (3), nor in (4). Since , this means that there must be exatly one element that is both in (3) and (4). The only way for this to happen is that . Consequently, , and so, . This proves the result in the first case.

For the case in which is in (2), it is necessary that , which means that . Hence, there exists (in fact, ) such that and . Now, the elements

are equally separated by the same separation . That is,

Additionally, the elements

are equally separated by the same separation . That is,

Now, must contain all the elements in (5) and (6), as well as the element , which is not in (5), nor in (6). Since , this means that there must be exactly one element that is both in (5) and in (6). The only way for this to happen is that . Consequently, , and so, . Hence, , , . This proves the result in the second case and concludes the proof for .

Now, let us prove the result for a general . We will denote the set .

Notice that while, if , then , hence, . Consequently, if , we can affirm that there exists exactly one integer s such that for all and for all .

If , then we already have, by the second item of the lemma, that for a given positive integer for all .

On one hand,

which has elements. On the other hand,

has elements.

Now, . By the inclusion–exclusion principle, and since is not in ,

On the contrary, if , then, since , we can apply the induction hypothesis and affirm that either one of the following cases, (a) or (b), holds.

- (a)

- There exists a positive integer such that for all i with and ;

- (b)

- There exists a positive integer such that for all i with .

In case (a), we will have

and

In case (b), we will have

and

Now,

This is only possible in case (b) with

and, hence, with , that is, , hence yielding the result with . □

Lemma 6.

Let and . The unique non-quasi-ordinary numerical semigroup of genus g and quasi-ordinarization number is .

Proof.

If , there is only one numerical semigroup non-ordinary and non-quasi-ordinary as we can observe in Figure 1, and it is exactly , which indeed, has a quasi-ordinarization number and it is of the form . The case and are excluded from the statement (and analyzed in Remark 2). So, we can assume that either or .

Suppose that the quasi-ordinarization number of is . Since , we know that the set of all non-gaps between 0 and must contain all the sums

However, the number of non-gaps between 0 and is either or g depending on whether is a gap or not. So, . On the other hand, by Lemma 5, .

If g is odd, we get that and so, . Then, by the second item in Lemma 5, we get that for . Now, and, since , one can deduce that . If this contradicts . So, for and the remaining non-gaps between g and are necessarily for to .

If g is even, then . If , then, since the number of summands in the sum is at least 4 (because we excluded the even genera 4 and 6), we can apply the third item in Lemma 5. Then, we obtain . This, together with implies that . So, , contradicting . Hence, it must be . If , then, by the second item in Lemma 5, we obtain for all . Now, and, since , one can deduce that . However, if . So, con only be 1 or 2. If this contradicts . So, for and the remaining non-gaps between g and are necessarily for to . □

Remark 2.

For , the maximum quasi-ordinarization number is, in fact, attained by three of the 7 semigroups of genus 4. The semigroups whose quasi-ordinarization number is maximum are , , .

For , the maximum quasi-ordinarization number is, in fact, attained by two of the 23 semigroups of genus 6. The semigroups whose quasi-ordinarization number is maximum are , .

Hence, and are exceptional cases.

4. Analysis of

Let us denote , the number of numerical semigroups of genus g and ordinarization number r and , the number of numerical semigroups of genus g and quasi-ordinarization number r.

We can observe a behavior of very similar to the behavior of introduced in [9].

Indeed, for odd g and large r, it holds and for even g and large q, it holds . We will give a partial proof of these equalities at the end of this section.

It is conjcetured in [9] that, for each genus and each ordinarization number ,

We can write the new conjecture below paralleling this.

Conjecture 1.

For each genus and each quasi-ordinarization number ,

Now, we will provide some results on for high quasi-ordinarization numbers. First, we will need Freĭman’s Theorem [25,26] as formulated in [27].

Theorem 2

(Freĭman). Let A be a set of integers such that . If , then A is a subset of an arithmetic progression of length .

The next lemma is a consequence of Freĭman’s Theorem. The lemma shows that the first non-gaps of numerical semigroups of large quasi-ordinarization number must be even.

Lemma 7.

If a semigroup Λ of genus g has quasi-ordinarization number q with then all its non-gaps which are less than or equal to are even.

Proof.

Suppose that is a semigroup of genus g and quasi-ordinarization number .

Since the quasi-ordinarization is q, this means that and , hence . Let . By the previous equality, . We have that the elements in are upper bounded by and so . Then, . Since the Frobenius number of is at most , and, so, . Now, since , we have and we can apply Theorem 2 with . Thus, we have that A is a subset of an arithmetic progression of length at most .

Let be the difference between consecutive terms of this arithmetic progression. The number can not be larger than or equal to three since otherwise , a contradiction with q being the quasi-ordinarization number.

If , then and so . We claim that in this case . Indeed, suppose that . Then, satisfies either or . If the second inequality is satisfied, then it is obvious that . If the first inequality is satisfied, then we will prove that for all by induction on m and this leads to . Indeed, if , then . Now, and since , we have and so . Since is in , this means that and this proves the claim.

Now, together with implies that , a contradiction.

So, we deduce that , leading to the proof of the lemma. □

The next lemma was proved in [9].

Lemma 8.

Suppose that a numerical semigroup Λ has ω gaps between 1 and and , then

- ,

- the Frobenius number of Λ is smaller than n,

- the genus of Λ is ω.

Let be a numerical semigroup. As in [9], let us say that a set is -closed if for any and any in , the sum is either in B or it is larger than . If B is -closed, so is . Indeed, is either in or it is larger than . The new -closed set contains 0. We will denote by , the -closed sets of size i that contain 0.

Let be the set of numerical semigroups of genus . It was proved in [9] that, for r, an integer with , it holds

We will see now that, for q an integer with , it holds

This proves that, for q, an integer with , we have

Theorem 3.

Let , , and let q be an integer with . Define

- If Ω is a numerical semigroup of genus ω and B is an Ω-closed set of size and first element equal to 0 thenis a numerical semigroup of genus g and quasi-ordinarization number equal to q.

- All numerical semigroups of genus g and quasi-ordinarization number q can be uniquely written asfor a unique numerical semigroup Ω of genus ω and a unique Ω-closed set B of size and first element equal to 0.

- The number of numerical semigroups of genus g and quasi-ordinarization number q depends only on ω. It is exactly

Proof.

- Suppose that is a numerical semigroup of genus and B is an -closed set of size and first element equal to 0. Let , , and .First of all, let us see that the complement has g elements. Notice that all elements in X are even while all elements in Y are odd. So, X and Y do not intersect. Additionally, the unique element in is . The number of elements in the complement will beWe know that all gaps of are at most . So, and we conclude that .Before proving that is a numerical semigroup, let us prove that the number of non-zero elements in , which are smaller than or equal to is q. Once we prove that is a numerical semigroup, this will mean, by Lemma 3, that it has quasi-ordinarization number q. On the one hand, all elements in Y are larger than . Indeed, if is the enumeration of (i.e., with ), then . Now, for any , . On the other hand, all gaps of are at most and so all the even integers not belonging to X are less than g. So, the number of non-zero non-gaps of smaller than or equal to is .To see that is a numerical semigroup, we only need to see that it is closed under addition. It is obvious that , , . It is also obvious that since is a numerical semigroup and that since, as we proved before, all elements in Y are larger than g.It remains to see that . Suppose that and . Then, for some and for some . Then, . Since B is -closed, we have that either and so or . In this case, . So, .

- First of all notice that, since the Frobenius number of a semigroup of genus g is smaller than , it holdsFor any numerical semigroup , the set is a numerical semigroup. If has a quazi-ordinarization number then, by Lemma 7,The semigroup has exactly non-gaps between 0 and and gaps between 0 and . We can use Lemma 8 with sincewhich implies . Then, the genus of is and the Frobenius number of is at most . This means that all even integers larger than belong to .Define . That is, D is the set of odd non-gaps of smaller than . We claim that is a -closed set of size . The size follows from the fact that the number of non-gaps of between g and is and that the number of even integers in the same interval is . Suppose that and . Then, for some j in and . If , we are done. Otherwise, we have . Since is a numerical semigroup and both , it holds . Furthermore, is odd since j is also. So, is either larger than or it is in . Then, is a -closed set of size and first element zero.

- The previous two points define a bijection between the set of numerical semigroups in of quasi-ordinarization number q and the set Hence,

□

Corollary 1.

Suppose that . Then,

Define, as in [9], the sequence by The first elements in the sequence, from to are

| ω | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 1 | 2 | 7 | 23 | 68 | 200 | 615 | 1764 | 5060 | 14,626 | 41,785 | 117,573 | 332,475 | 933,891 | 2,609,832 | 7,278,512 |

We remark that this sequence appears in [5], where Bernardini and Torres proved that the number of numerical semigroups of genus whose number of even gaps is is exactly . It corresponds to the entry A210581 of The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences [23].

We can deduce the values using the values in the previous table together with Theorem 3 for any g, whenever .

The next corollary is a consequence of the fact that the sequence is increasing for between 0 and 15.

Corollary 2.

For any and any , it holds .

If we proved that for any , this would imply for any .

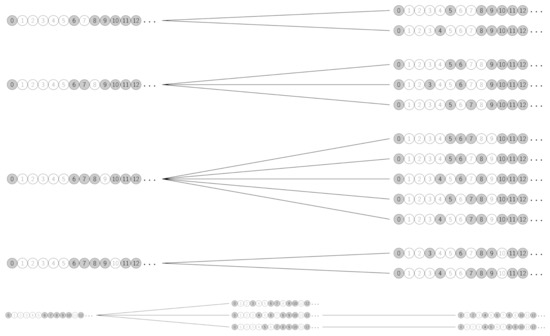

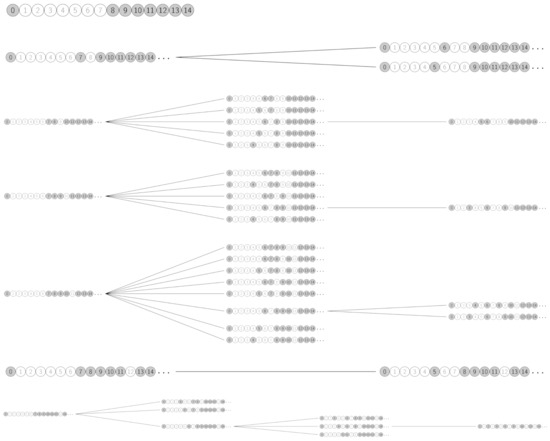

5. The Forest

Fix a genus g. We can define a graph in which the nodes are all semigroups of that genus and whose edges connect each semigroup to its quasi-ordinarization transform, if it is not itself. The graph is a forest rooted at all ordinary and quasi-ordinary semigroups of genus g. In particular, the quasi-ordinarization transform defines, for each fixed genus and conductor, a tree rooted at the unique quasi-ordinary semigroup of that genus and conductor, given in Lemma 2. See in Figure 3, in Figure 4, and in Figure 5.

Figure 3.

.

Figure 4.

.

Figure 5.

.

In the forest , we know that the parent of a numerical semigroup that is not a root is its quasi-ordinarization transform. Let us analyze now, what the children of a numerical semigroup are. The next result is well known and can be found, for instance, in [2]. We use to denote .

Lemma 9.

Suppose that Λ is a numerical semigroup and that . The set is a numerical semigroup if and only if

- ,

- ,

- .

The elements such that , are denoted pseudo-Frobenius numbers of . The elements such that , are denoted fundamental gaps of . The elements satisfying the three conditions will be called candidates.

Suppose that a numerical semigroup with Frobenius number F has children in . Let be the generators of between the subconductor and . For , let be the candidates of . The children of in are the semigroups of the form , for and .

6. Relating , , and

Now, we analyze the relation between the kinship of different nodes in , , and . If two semigroups are children of the same semigroup , then they are called siblings. If and are siblings, and is a child of , then we say that is a niece/nephew of .

Let denote the quasi-ordinarization of . The next lemmas are quite immediate from the definitions.

Lemma 10.

If is a child of in , then is a niece/nephew of in .

As an example, is a child of in , while is a niece of in .

Lemma 11.

If and are siblings in , then they are siblings in but not in .

As an example, and are siblings in and in (see Figure 2), but they are not siblings in (see Figure 5).

Lemma 12.

If and are siblings in , then and are siblings in .

As an example, and are siblings in (see Figure 2), and and are siblings in .

As a consequence of the previous two lemmas, we obtain this final lemma.

Lemma 13.

If and are siblings in , then and are siblings in .

As an example, and are siblings in and and are siblings in .

7. Conclusions

Quasi-ordinary semigroups are those semigroups that have all gaps except one in a row, while ordinary semigroups have all gaps in a row.

We defined a quasi-ordinarization transform that, applied repeatedly to a non-ordinary numerical semigroup stabilizes in a quasi-ordinary semigroup of the same genus.

From this transform, fixing a genus g, we can define a forest whose nodes are all semigroups of genus g, whose roots are all ordinary and quasi-ordinary semigroups of that genus, and whose edges connect each non-ordinary and non-quasi-ordinary numerical semigroup to its quasi-ordinarization transform.

We conjectured that the number of numerical semigroups in at a given depth is at most the number of numerical semigroups in at the same depth. We provided a proof of the conjecture for the largest possible depths. Proving this conjecture for all depths would prove the conjecture that . Hence, we expect our work to be a step toward the proof of the conjectured increasingness of the sequence .

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partly supported by the Catalan Government under grant 2017 SGR 00705 and by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitivity under grant TIN2016-80250-R.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not Applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rosenfeld, V.R.; Nordahl, T.E. Semigroup theory of symmetry. J. Math. Chem. 2016, 54, 1758–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales, J.; García-Sánchez, P. Numerical Semigroups; Volume 20 of Developments in Mathematics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bras-Amorós, M. Tempered monoids of real numbers, the golden fractal monoid, and the well-tempered harmonic semigroup. Semigroup Forum 2019, 99, 496–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bras-Amorós, M. Fibonacci-like behavior of the number of numerical semigroups of a given genus. Semigroup Forum 2008, 76, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardini, M.; Torres, F. Counting numerical semigroups by genus and even gaps. Discret. Math. 2017, 340, 2853–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, V.; Rosales, J. The set of numerical semigroups of a given genus. Semigroup Forum 2012, 85, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, V.; García-Sánchez, P.; Puerto, J. Counting numerical semigroups with short generating functions. Int. J. Algebra Comput. 2011, 21, 1217–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bras-Amorós, M. Bounds on the number of numerical semigroups of a given genus. J. Pure Appl. Algebra 2009, 213, 997–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bras-Amorós, M. The ordinarization transform of a numerical semigroup and semigroups with a large number of intervals. J. Pure Appl. Algebra 2012, 216, 2507–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bras-Amorós, M.; Bulygin, S. Towards a better understanding of the semigroup tree. Semigroup Forum 2009, 79, 561–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bras-Amorós, M.; de Mier, A. Representation of numerical semigroups by Dyck paths. Semigroup Forum 2007, 75, 677–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bras-Amorós, M.; Fernández-González, J. The right-generators descendant of a numerical semigroup. Math. Comp. 2020, 89, 2017–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizalde, S. Improved bounds on the number of numerical semigroups of a given genus. J. Pure Appl. Algebra 2010, 214, 1862–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fromentin, J.; Hivert, F. Exploring the tree of numerical semigroups. Math. Comp. 2016, 85, 2553–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, N. Counting numerical semigroups by genus and some cases of a question of Wilf. J. Pure Appl. Algebra 2012, 216, 1016–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, N. Counting numerical semigroups. Am. Math. Mon. 2017, 124, 862–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komeda, J. On Non-Weierstrass Gap Sequqences; Technical Report; Kanagawa Institute of Technology: Kanagawa, Japan, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Komeda, J. Non-Weierstrass numerical semigroups. Semigroup Forum 1998, 57, 157–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dorney, E. Degree asymptotics of the numerical semigroup tree. Semigroup Forum 2013, 87, 601–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. Constructing numerical semigroups of a given genus. Semigroup Forum 2010, 80, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, A. Fibonacci-like growth of numerical semigroups of a given genus. Semigroup Forum 2013, 86, 634–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bras-Amorós, M. On Numerical Semigroups and Their Applications to Algebraic Geometry Codes, in Thematic Seminar “Algebraic Geometry, Coding and Computing”, Universidad de Valladolid en Segovia. 2007. Available online: http://www.singacom.uva.es/oldsite/seminarios/WorkshopSG/workshop2/Bras_SG_2007.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- OEIS Foundation Inc. The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences. 2021. Available online: http://oeis.org (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Rosales, J.C.; García-Sánchez, P.A.; García-García, J.I.; Jiménez Madrid, J.A. The oversemigroups of a numerical semigroup. Semigroup Forum 2003, 67, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freĭman, G.A. On the addition of finite sets. Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR 1964, 158, 1038–1041. [Google Scholar]

- Freĭman, G.A. Nachala Strukturnoi Teorii Slozheniya Mnozhestv; Kazanskii Gosudarstvennyi Pedagogiceskii Institut: Kazan, Russia, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Nathanson, M.B. Additive Number Theory; Volume 165 of Graduate Texts in Mathematics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).