Abstract

Symmetry plays an important role in solving practical problems of applied science, especially in algorithm innovation. In this paper, we propose what we call the self-adaptive inertial-like proximal point algorithms for solving the split common null point problem, which use a new inertial structure to avoid the traditional convergence condition in general inertial methods and avoid computing the norm of the difference between and before choosing the inertial parameter. In addition, the selection of the step-sizes in the inertial-like proximal point algorithms does not need prior knowledge of operator norms. Numerical experiments are presented to illustrate the performance of the algorithms. The proposed algorithms provide enlightenment for the further development of applied science in order to dig deep into symmetry under the background of technological innovation.

1. Introduction

We are concerned with the following split common null point problem (SCNPP):

where and are Hilbert spaces, and are set-valued mappings, and is a nonzero bounded linear operator.

The SCNPP (1) and (2), which covers the convex feasibility problem (CFP) (Censor and Elfving [1]), variational inequalities (VIs) ( Moudafi [2]), and many constrained optimization problems as special cases, has attracted important attention both theoretically and practically (see Byrne [3], Moudafi and Thukur [4]).

The main idea to solve SCNPP comes from symmetry, that is, invariance. Therefore, fixed point theory plays a key role here. We recall the resolvent operator , which plays an essential role in the approximation theory for zero points of maximal monotone operators as well as in solving (1) and (2) and has the following key facts.

- Fact 1:

- The resolvent is not only always single-valued but also firmly monotone:

- Fact 2:

- Using the resolvent operator, the problem (1) and (2) can be written as a fixed point problem:

Fact 2 transforms the problem (1) and (2) into a fixed-point problem, and the research of the latter reflects the invariance in transformation, which is the essence of symmetry. Based on Fact 2, Byrne, et al. [5] proposed the following forward–backward algorithm:

and obtained weak convergence, where is the adjoint of T, the stepsize with .

At the same time, the inertial method originating from the heavy ball with friction system has attracted increasing attention thanks to its convergence properties in the field of continuous optimization. Therefore, many scholars have combined the forward–backward method (4) with the inertial algorithm to study the SCNPP and proposed some iterates. For related works, one can consult Alvarez and Attouch [6], Alvarez [7], Attouch et al. [8,9,10], Akgül [11], Hasan et al. [12], Khdhr et al. [13], Ochs et al. [14,15], Dang et al. [16], Soleymani and Akgül [17], Suantai et al. [18,19], Dong et al. [20], Sitthithakerngkiet et al. [21], Kazmi and Rizvi [22], Promluang and Kumman [23], Eslamian et al. [24], and references therein.

Although these algorithms improved the numerical solution of the split common null point problem, there exist two common drawbacks: one is that the step size depends on the norm of the linear operator T, which means there is a high computation cost, because the norm of the linear operator must be estimated before selecting the step size; another drawback is that the following condition is required:

which means that one not only needs to calculate the norm of the difference between and in advance at each step but also check if satisfies (5).

So it is natural to ask the following questions:

- Question 1.1

- Can we construct the iterate for SCNPP whose step size does not depend on the norm of the linear operator T?

- Question 1.2

- Can condition (5) be removed from the inertial method and still ensure the convergence of the sequence? Namely, can we construct a new inertial algorithm to solve SCNPP (1) and (2) without prior computation of the norm of the difference between and ?

The purpose of this paper is to present a new self-adaptive inertial-like technique to give an affirmative answer to the above questions. Importantly, the innovative algorithms provide an idea of how to use symmetry to solve real-world problems in applied science.

2. Preliminaries

Let and be the inner product and the induced norm in a Hilbert space , respectively. For a sequence in , denote and by the strong and weak convergence to x of , respectively. Moreover, the symbol represents the -weak limit set of , that is,

The identity below is useful:

for all and .

Definition 1.

A multivalued mapping with domain is monotone if

for all , , and . A monotone operator A is referred to be maximal if its graph is not properly contained in the graph of any other monotone operator.

Definition 2.

Let H be a real Hilbert space and let be a mapping.

- (i)

- h is called Lipschitz with constant if for all .

- (ii)

- h is called nonexpansive if for all .

From Fact 1, we can conclude that is a nonexpansive operator if A is a maximal monotone mapping. Moreover, due to the work of Aoyama et al. [25], we have the following property:

where .

Definition 3.

Let C be a nonempty closed convex subset of H. We use to denote the projection from H onto C; namely,

The following significant characterization of the projection should be recalled: given and ,

Lemma 1.

(Xu [26], Maingé [27]) Assume that is a sequence of nonnegative real numbers such that

where is a sequence in and is a sequence in such that

- (1)

- ;

- (2)

- or ;

- (3)

- .

Then .

Lemma 2.

(see, e.g., Opial [28]) Let H be a real Hilbert space and be a bounded sequence in H. Assume there exists a nonempty subset satisfying the properties:

- (i)

- exists for every ,

- (ii)

- .

Then, there exists such that converges weakly to .

Lemma 3.

(Maingé [29]) Let be a sequence of real numbers that does not decrease at the infinity in the sense that there exists a subsequence of such that for all . Also consider the sequence of integers defined by

Then, is a nondecreasing sequence verifying and, for all ,

3. Main Results

3.1. Variant of Discretization

Inspired by the discretization of the second order dynamic system , we consider the following iterative sequence

where , are two arbitrary initial points, and is a real nonnegative number. This recursion can be rewritten as

which proves that the sequence satisfying (10) always exists for any choice of the sequences and , provided that .

To distinguish from Alvarez and Attouch’s Inertial-Prox algorithm ([6]), we call it inertial-like proximal point algorithm. Combining the inertial-like proximal point algorithm and the forward–backward method, we propose the following self adaptive inertial-like proximal algorithms.

3.2. Some Assumptions

Assumption 1.

Throughout the rest of this paper, we assume that and are Hilbert spaces. We study the split common null point problem (SCNPP) as (1) and (2), where and are set-valued maximal monotone mappings, respectively, and is a bounded linear operator, means the adjoint of T.

Assumption 2.

The functions are defined as:

and

Assumption 3.

Denote by Ω the solution set of the SCNPP (1) and (2); namely,

and we always assume .

3.3. Inertial-like Proximal Point Algorithms

Remark 1.

It is not hard to find that if for some , then is a solution of the SCNPP (1) and (2), and the iteration process is terminated in finite iterations. In addition, if and step size depends on the norm of linear operator T, Algorithm 1 recovers Byrne et al. [5].

| Algorithm 1 Self adaptive inertial-like algorithm |

|

Remark 2.

In the subsequent convergence analysis, we will always assume that the two algorithms generate an infinite sequence, namely, the algorithms are not terminated in finite iterations. In addition, in the simulation experiments, we will give a stop criterion to end the iteration for practice.

3.4. Convergence Analysis of Algorithms

Theorem 1.

If the assumptions (A1)–(A3) are satisfied, then the sequence generated by Algorithm 1 converges weakly to a point .

Proof.

To this end, the following three situations will be discussed: (I). , ; (II). ; and (III). .

- (I).

- First, we consider the case of , .

Without loss of generality, we take , and then we have and from Fact 2. It turns out from (11) and (7) that

Since is nonexpansive, it follows from (12) that

It follows from the property (8) of resolvent operator that

and then from the definition of , we have that

Notice the definition of , we obtain

which means that

and, hence, the sequence is bounded, and so in turn is .

It may be assumed that the sequence is not decreasing at the infinity in the sense that there exists a subsequence of positive integers such that there exists a nondecreasing sequence for (for some large enough) such that as and

for each .

Notice that (15) holds for each , so from (15) with n replaced by , we have

which means that

observe the relation for each , the above inequality concludes a contradiction.

Therefore, there exists an integer such that for all . Then, we have the limit of the sequence , denoted by , and so

In addition, we have

It turns out from (15) that

and so

as , furthermore, we can conclude that since F and G are Lipschitz continuous (see Censor et al. [30]), and so . Therefore, we have

Now, it remains to show that

Since the sequence is bounded, let and be a subsequence of weakly converging to . This suffices to verify that and .

Notice and the assumption , we have , which implies that

Therefore, there exists a subsequence of , which converges weakly to . It follows from the lower semicontinuity of and (16) that

which means that .

On the other hand, according to (11) and (12), we have

Using again the property (8), we have

If we take in the above inequality, then we have

which yields

Thus, it follows from (17) and (18) that

Since the sequence (12) can be rewritten as

therefore, we have

In addition, it turns out from that

Note that the graph of the maximal monotone operator A is weakly–strongly closed; by passing to the limit in (19), we obtain , namely, . Consequently, .

Since the choice of is arbitrary, we conclude that . Hence, it follows Lemma 1 that the result holds.

- (II).

- Secondly, we consider the case of . In this case, . Similar to the proof of (15), we have thatand then

It may be assumed that the sequence is not decreasing at the infinity in the sense that there exists a subsequence of positive integers such that there exists a nondecreasing sequence for (for some large enough) such that as and

for each .

Notice that (20) holds for each , so from (20) with n replaced by , we have

which means that

observe the relation for each , the above inequality concludes a contradiction.

So there exists an integer such that for all . Then, we have the limit of the sequence , denoted by , and so

Now, it remains to show that

Since the sequence is bounded, let and be a subsequence of weakly converging to . It suffices to verify that and .

Next, we show that . Indeed, it follows from the relation between the norm and inner product that

where M is a constant such that for all n and is a given constant, which means that

and then

which implies as .

Since , we have and then

It follows from (21) that and then

By using the lower semicontinuity of , we have

which means that .

Notice again that the sequence (12) can be rewritten as

therefore, we have

In addition, it turns out from that

Note that the graph of the maximal monotone operator A is weakly–strongly closed, by passing to the limit in (22), we obtain , namely, . Consequently, .

Since the choice of is arbitrary, we conclude that . Hence, it follows Lemma 1 that the result holds.

- (III).

- Finally, we consider the case of . Indeed, we just need to replace with in the proof of (II) and then the desired result is obtained. □

Next, we prove the strong convergence of Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2 Update of self adaptive inertial-like algorithm |

|

Theorem 2.

If the assumptions (A1)–(A3) are satisfied, then the sequence generated by Algorithm 2 converges in norm to (i.e., the minimum-norm element of the solution set Ω).

Proof.

Similar to the weak convergence, we consider the following three situations: (I). and ; (II). ; and (III).

- (I).

- We first consider the strong convergence under the situation of and .

Let us begin by showing the boundedness of the sequence . To see this, we denote and use the projection to obtain in a similar way to the proof of (13)–(15) of Theorem 1 that

hence, one can see .

It turns out from (23) that

which implies that the sequence is bounded, and so are the sequences , .

Applying the identity (7), we deduce that

Substituting (13) and (24) into (25) and after some manipulations, we obtain

Next we distinguish two cases.

Case 1. The sequence is nonincreasing at the infinity in the sense that there exists such that for each , . This particularly implies that exists and thus,

For all , it follows from (26) that

Now, due to the assumptions on , , and and the boundedness of and , we have

It turns out from (29) that since F and G are Lipschitz continuous and so , and from (27) that , which in turn implies from (11) that

Observing , we obtain

This proves the asymptotic regularity of .

By repeating the relevant part of the proof of Theorem 1, we obtain .

It is now at the position to prove the strong convergence of . Rewriting , where , and making use of the inequality , which holds for all in Hilbert spaces, we obtain

It follows from (7) that

and then

It turns out from (24) that ; hence, we obtain

Submitting (13) into the above inequality, we have

which means that

For simplicity, we denote by

where , and .

Since and , which implies for all , we deduce that

Combining (28) and (32) implies that

In addition, by the assumptions on and , we have

These enable us to apply Lemma 1 to (31) to obtain that . Namely, in norm, and the proof of Case 1 is complete.

Case 2. The sequence is not nonincreasing at the infinity in the sense that there exists a subsequence of positive integers such that (as ) and with the properties:

Notice the boundedness of the sequence , which implies that there exists the limit of the sequence and, hence, we conclude that

Observe that (26) holds for all , so replacing n with in (26) and transposing, we obtain

Now, taking the limit by letting yields

Note that we still have and that the relations (33)–(35) are sufficient to guarantee that .

Next, we prove .

As a matter of fact, observe that (30) holds for each . So replacing n with in (30) and using the relation , we obtain

therefore, we have

Notice again the relation , we obtain

[Here M is a constant such that for all n.]

Now, since , and , we have

Consequently, the relation (36) and assure that , which follows from Lemma 3 that

Namely, in norm, and the proof of Case 2 is complete.

- (II).

- Now, we consider the case of . In this case, we have and . Denote by , similar to the proof of (24)–(26), we obtain that the sequence is bounded andwhich implies that

Next, we distinguish two cases.

Case 1. There exists such that for each , , which implies that exists, and thus

Since and , it follows from (37) that

which means that since F and G are Lipschitz continuous and so . Similar to the proof of in the weak convergence Theorem 1, we still have the asymptotic regularity of and .

Similar to the proof of (30), we have

where , and .

Obviously, and are satisfying the conditions in Lemma 1, so we can conclude that .

Case 2. The sequence is not nonincreasing at the infinity in the sense that there exists a subsequence of positive integers such that (as ) and with the properties:

Since the sequence is bounded, there exists the limit of the sequence and, hence, we conclude that

Notice (37) holds for all , so replacing with in (37) and using the relation , we have

Since and , we obtain

Similarly, we still have the asymptotic regularity of and .

In addition, similar to the inequality above (31), we obtain the following

which means that

notice again the relation for all , we have

[Here M is a constant such that for all n.]

Again, since , and , we have

Consequently, the inequality (38) and assure that , which follows from Lemma 3 that

Namely, in norm, and the proof of the second situation (II) is complete.

- (III.)

- Finally, we consider the case of . Indeed, we just need to replace with in the proof of (II), and then the desired result is obtained. □

4. Numerical Examples and Experiments

Example 1.

We consider the numerical Let . Define the mappings A, B, and T by , , and for all . Then it can be shown that A and B are monotone operators, respectively, and the adjoint of T is . For simplicity, we choose , in Algorithm 2 for all . We consider different choices of initial functions and . In addition, is used as stopping criterion.

- Case I:

- ;

- Case II:

- ;

- Case III:

- .

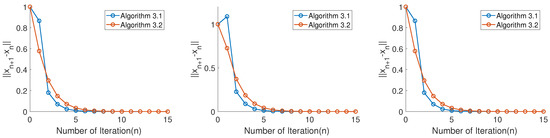

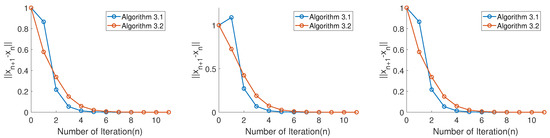

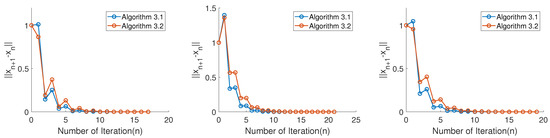

It is clear that our algorithm is fast, efficient, stable, and simple to implement. All the numerical results are presented in Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3 under different initial functions, and the number of iterations and CPU run time remain almost consistent, which are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Three initial cases for .

Figure 2.

Three initial cases for .

Figure 3.

Three initial cases for .

Table 1.

Time and iterations of Algorithms 1 and 2 in Ex.1.

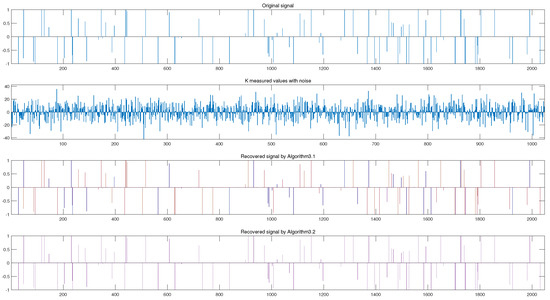

Example 2.

We consider an examplewhich is from the realm of compressed sensing. More specifically, we try to recover the K-sparse original signal from the observed signal b.

Here, matrix , would be involved and created by standard Gaussian distribution. The observed signal , where is noise. For more details on signal recovery, one can consult Nguyen and Shin [31].

Conveniently, solving the above sparse signal recovery problem is usually equivalent to solving the following LASSO problem (see Gibali et al. [32] and Moudafi et al. [33]):

where t is a given positive constant. If we define

then one can see that the LASSO problem coincides with the problem of finding such that

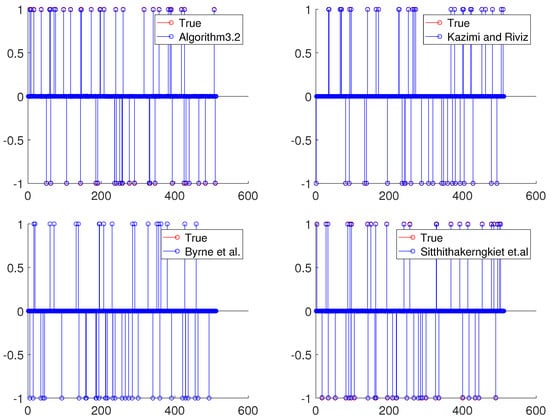

During the operation, is generated randomly with , , is K-spikes with amplitude distributed throughout the region randomly. In addition, the signal to noise ratio (SNR) is chosen as , in two algorithms and in Algorithm 2. The recovery simulation results are illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Numerical results for , and .

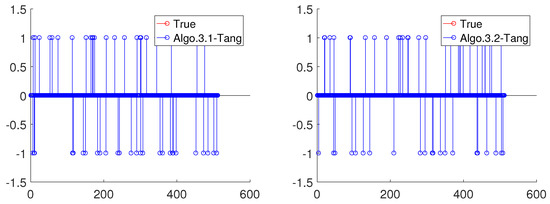

Moreover, we also compare our algorithms with the results of Sitthithakerngkiet et al. [21], Kazimi and Riviz. [22], Byrne et al. [5] which have no inertial item and Tang [34] with a general inertial method.

For simplicity, for Algorithm 3.1 in Sitthithakerngkiet et al. [21], the nonexpansive mappings are defined as , , , and , the parameters and . For Algorithm 3.1 in Sitthithakerngkiet et al. [21], Kazimi and Riviz [22], and Algorithm 3.1 in Byrne et al. [5], the step size , where . For Algorithms 3.1 and 3.2 in Tang [34], the step size is self-adaptive, and . The experiment results are illustrated in Figure 5 and Table 2.

Figure 5.

Numerical results for , and .

Table 2.

Comparisons of Algorithm 3.1, Algorithm 3.2, and Algorithm 3.1 in Sitthithakerngkiet [21], Algorithm 3.1 in Byrne [5], Algorithm 3.1 in Kazimi and Riviz [22], and Algorithms 3.1 and 3.2 in Tang [34].

From Table 2, we can see that our Algorithms 1 and 2 seem to have some competitive advantages.

Compared with the general inertial methods, the main advantage of our Algorithms 1 and 2 in this paper, as mentioned in the previous sections, is that they have no constraint on the norm of the difference between and in advance, and no assumption on the inertial parameter , so it is extremely natural, attractive, and user friendly.

Moreover, when we test Algorithm 3.1 of Sitthithakerngkiet et al. [21], Algorithm 3.1 of Byrne et al. [5], and Kazimi and Riviz [22], we find that the convergence rate depends strongly on the step size , which depends on the norm of linear operator T, so another advantage of our Algorithms 1 and 2 in this paper is the self-adaptive step size.

5. Conclusions

We proposed two new self-adaptive inertial-like proximal point algorithms (Algorithms 1 and 2) for the split common null point problem (SCNPP). Under more general conditions, the weak and strong convergences to a solution of SCNPP are obtained. The new inertial-like proximal point algorithms listed are novel in the following ways:

- (1)

- Different from the average inertia technique, the convergence of the proposed algorithms remain even if without the term below:They do not need to calculate the values of in advance if one chooses the coefficients , which means that the algorithms are easy to use.

- (2)

- The inertial factors can be chosen in , which means that is a possible equivalent to 1 and opens a wider path for parameter selection.

- (3)

- The step sizes of our inertial proximal algorithms are self-adaptive and are independent of the cocoercive coefficients, which means that they do not use any prior knowledge of the operator norms.

In addition, two numerical examples involving comparison results have been expressed to show the efficiency and reliability of the listed algorithms.

Author Contributions

Formal analysis, Y.T. and A.G.; Writing—original draft, Y.T. and Y.Z.; Writing—review & editing, A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This article was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing (CSTC2021JCYJ-msxmX0177), the Science and Technology Research Project of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (KJQN 201900804), and the Research Project of Chongqing Technology and Business University (KFJJ1952007).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No statement since the study did not report any data.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their deep gratitude to the referee for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Censor, Y.; Elfving, T. A multiprojection algorithm using Bregman projections in product space. Numer. Algorithms 1994, 8, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moudafi, A. Split monotone variational inclusions. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 2011, 150, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, C. Iterative oblique projection onto convex sets and the split feasibility problem. Inverse Probl. 2002, 18, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moudafi, A.; Thakur, B.S. Solving proximal split feasibilty problem without prior knowledge of matrix norms. Optim. Lett. 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Byrne, C.; Censor, Y.; Gibali, A.; Reich, S. Weak and strong convergence of algorithms for the split common null point problem. J. Nonlinear Convex Anal. 2012, 13, 759–775. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, F.; Attouch, H. An inertial proximal method for maximal monotone operators via discretization of a nonlinear oscillator with damping. Set-Valued Anal. 2001, 9, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, F. Weak convergence of a relaxed and inertial hybrid projection-proximal point algorithm for maximal monotone operators in Hilbert spaces. SIAM J. Optim. 2004, 14, 773–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attouch, H.; Chbani, Z. Fast inertial dynamics and FISTA algorithms in convex optimization, perturbation aspects. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1507.01367. [Google Scholar]

- Attouch, H.; Chbani, Z.; Peypouquet, J.; Redont, P. Fast convergence of inertial dynamics and algorithms with asymptotic vanishing viscosity. Math. Program. 2018, 168, 123–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attouch, H.; Peypouquet, J.; Redont, P. A dynamical approach to an inertial forward-backward algorithm for convex minimization. SIAM J. Optim. 2014, 24, 232–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgül, A. A novel method for a fractional derivative with non-local and non-singular kernel. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2018, 114, 478–482. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, P.; Sulaiman, N.A.; Soleymani, F.; Akgül, A. The existence and uniqueness of solution for linear system of mixed Volterra-Fredholm integral equations in Banach space. AIMS Math. 2020, 5, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khdhr, F.W.; Soleymani, F.; Saeed, R.K.; Akgül, A. An optimized Steffensen-type iterative method with memory associated with annuity calculation. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2019, 134, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochs, P.; Chen, Y.; Brox, T.; Pock, T. iPiano: Inertial proximal algorithm for non-convex optimization. SIAM J. Imaging Sci. 2014, 7, 1388–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochs, P.; Brox, T.; Pock, T. iPiasco: Inertial proximal algorithm for strongly convex optimization. J. Math. Imaging Vis. 2015, 53, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Y.; Sun, J.; Xu, H.K. Inertial accelerated algorithms for solving a split feasibility problem. J. Ind. Manag. Optim. 2017, 13, 1383–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Soleymani, F.; Akgül, A. European option valuation under the Bates PIDE in finance: A numerical implementation of the Gaussian scheme. Discret. Contin. Dyn. Syst.-S 2018, 13, 889–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Suantai, S.; Srisap, K.; Naprang, N.; Mamat, M.; Yundon, V.; Cholamjiak, P. Convergence theorems for finding the split common null point in Banach spaces. Appl. Gen. Topol. 2017, 18, 3345–3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Suantai, S.; Pholasa, N.; Cholamjiak, P. The modified inertial relaxed CQ algorithm for solving the split feasibility problems. J. Ind. Manag. Optim. 2017, 14, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dong, Q.L.; Cho, Y.J.; Zhong, L.L.; Rassias, T.M. Inertial projection and contraction algorithms for variational inequalities. J. Glob. Optim. 2018, 70, 687–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitthithakerngkiet, K.; Deepho, J.; Martinez-Moreno, J.; Kumam, P. Convergence analysis of a general iterative algorithm for finding a common solution of split variational inclusion and optimization problems. Numer Algorithms 2018, 79, 801–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazmi, K.R.; Rizvi, S.H. An iterative method for split variational inclusion problem and fixed point problem for a nonexpansive mapping. Optim. Lett. 2014, 8, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promluang, K.; Kumam, P. Viscosity approximation method for split common null point problems between Banach spaces and Hilbert spaces. J. Inform. Math. Sci. 2017, 9, 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ealamian, M.; Zamani, G.; Raeisi, M. Split common null point and common fixed point problems between Banach spaces and Hilbert spaces. Mediterr. J. Math. 2017, 14, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoyama, K.; Kohsaka, F.; Takahashi, W. Three generalizations of firmly nonexpansive mappings: Their relations and continuity properties. J. Nonlinear Convex Anal. 2009, 10, 131–147. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.K. Iterative algorithms for nonliear operators. J. Lond. Math. Soc. 2002, 66, 240–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maingé, P.E. Approximation methods for common fixed points of nonexpansive mappings in Hilbert spaces. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2007, 325, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Opial, Z. Weak convergence of the sequence of successive approximations for nonexpansivemappings. Bull. Am. Math. Soc. 1967, 73, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maingé, P.E. Strong convergence of projected subgradient methods for nonsmooth and nonstrictly convex minimization. Set-Valued Anal. 2008, 16, 899–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Censor, Y.; Gibali, A.; Reich, S. Algorithms for the split variational inequality problem. Numer. Algorithms 2012, 59, 301–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.L.N.; Shin, Y. Deterministic sensing matrices in compressive sensing: A survey. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 192795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gibali, A.; Liu, L.W.; Tang, Y.C. Note on the modified relaxation CQ algorithm for the split feasibility problem. Optim. Lett. 2018, 12, 817–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moudafi, A.; Gibali, A. l1 − l2 Regularization of split feasibility problems. Numer. Algorithms 2018, 78, 739–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tang, Y. New inertial algorithm for solving split common null point problem in Banach spaces. J. Inequal. Appl. 2019, 2019, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).