Abstract

The paper contains a discussion on solutions to symmetric type of fuzzy stochastic differential equations. The symmetric equations under study have drift and diffusion terms symmetrically on both sides of equations. We claim that such symmetric equations have unique solutions in the case that equations’ coefficients satisfy a certain generalized Lipschitz condition. To show this, we prove that an approximation sequence converges to the solution. Then, a study on stability of solution is given. Some inferences for symmetric set-valued stochastic differential equations end the paper.

1. Introduction

Stochastic differential equation are natural mathematical tools to describe behavior of many dynamic systems evolving in time. One of the main premises that prompts the use of these equations in description of a studied phenomenon is an assumption that the state of the system is affected by randomness or, more generally, certain stochastic noises. For numerous facts from the theory of these equations, we refer to e.g., [1,2,3,4].

However, many times in the modeling of physical phenomena there is a kind of uncertainty whose nature is different than in the case of randomness. This kind of uncertainty occurs when, for example measurement is not precise and expressed in linguistic terms such as “low pressure”, “high temperature”, and “about 10%”, when opinions of experts are vague, and knowledge of system’s parameters is imperfect. Such the uncertainty is well modeled by application of fuzzy sets (cf. [5,6,7]).

The coexistence of stochastic and fuzzy uncertainties motivates formulating models containing them both. Some successful results of combining randomness and fuzziness have been achieved in, e.g., petroleum contamination [8], optimal tracking design [9], neural networks [10,11], civil engineering and mechanics [12], Petri nets [13], optimization [14], ballast water management [15], option pricing [16], and fuzzy stochastic differential equations [17,18,19,20,21].

The last topic is the subject of this article’s research. In [17,18,19], we considered such equations in their natural integral form, which is a direct reflection of the form of crisp stochastic differential equations, i.e.,

where f is a fuzzy stochastic mapping, g is a single-valued stochastic mapping, and is a fuzzy random variable. The form of this equation is asymmetric because more components are on the right side of the equation. One could say that this equation is skewed right. In [20,21], the following fuzzy stochastic differential equations

are studied. This equation is asymmetric as well as the previous one, but now one could say that it is skewed left. If one considers these equations with the structure of single-valued mappings, it is easy to see that they are equivalent and therefore there is no particular reason to consider both equations. However, if the mappings are fuzzy, as in our case, these equations are no longer equivalent. The solution of the first asymmetric equation does not have to be the solution of the second asymmetric equation and vice versa; even the solution (if it exists) of the dual equation does not have to exist on the same interval. Moreover, solutions of both equations generally have the opposite tendency to change fuzziness in their values over time. To be more precise, we mention here that the diameter of the solution’s values cannot decrease as time increases for the first equation, while it cannot increase in the case of the solution to the second equation. This, of course, cannot be observed with single-valued equations.

From a practical point of view, it seems that we cannot limit ourself to just one type of solution, i.e. with nondecreasing fuzziness or nonincreasing fuzziness. Because the fuzziness of solutions may change and return to its previous state, it seems reasonable to consider equations that will ensure that such a requirement is met. Symmetric fuzzy stochastic differential equations

are such equations. They are also the first fundamental step towards possibility of future research on periodic solutions of fuzzy stochastic differential equations. Neither of the first two equations can have periodic solutions due to the property of monotonicity of fuzziness in successive values. These new symmetric equations do not contain this inconvenience. A symmetric form of these equations is also something special that distinguishes them from classical single-valued equations for which the symmetric form does not make any significant sense. Initial research in the area of symmetric fuzzy stochastic differential equations is made in [22,23] and it needs to be developed. Reference [22] presented a study of this equation with assumption that and satisfy a global Lipschitz condition, while, in a conference paper, reference [23] signaled that this condition can be relaxed. The current paper presents in great detail the justification of a theorem from [23] about the existence of a unique solution to the symmetric equation mentioned above with a weaker global condition of the Lipschitz type than in [22]. An analysis of solution stability in the case of small changes in equation parameters is given. In addition, some conclusions for multivalued stochastic equations resulting from the analysis are included.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 contains fundamental notations, facts, and properties concerning multivalued random variables, multivalued stochastic processes, fuzzy sets, fuzzy random variables, and fuzzy stochastic Lebesgue–Aumann integral. In Section 3, we present a study on an approximation sequence of fuzzy stochastic processes. With the help of this sequence, existence of the unique solution to symmetric fuzzy stochastic differential equations is proved. In Section 4, we treat about stability of the solution, while Section 5 indicates some inferences from the conducted study to the topic of symmetric multivalued stochastic differential equations. A conclusion in Section 6 summarizes the contribution of the paper.

2. Preliminaries

Almost all listed facts in this section relate to background knowledge and are taken from our work [22]. This is done for the convenience of the reader and to make the paper self-contained.

Let be the set of all nonempty, compact, and convex subsets of . This set can be supplied with the Hausdorff metric , which is defined by

where denotes a norm in . Then, the metric space is complete and separable (see [24]). In addition, the addition and scalar multiplication in are defined as follows: for , ,

Let be a complete probability space and denote the family of -measurable multivalued mappings (multivalued random variable) such that

A multivalued random variable is called -integrally bounded, , if there exists such that for any a and with . It is known (see [25]) that F is -integrally bounded iff is in , where is a space of equivalence classes (with respect to the equality P-a.e.) of -measurable random variables such that . Let us denote

The multivalued random variables are considered to be identical, if holds P-a.e.

Let , and denote . Let the system be a complete, filtered probability space with a filtration satisfying the usual hypotheses, i.e., is an increasing and right continuous family of sub--algebras of , and contains all P-null sets. We call a multivalued stochastic process, if for every a mapping is a multivalued random variable. We say that a multivalued stochastic process X is -continuous, if almost all (with respect to the probability measure P) its paths, i.e., the mappings , are -continuous functions. A multivalued stochastic process X is said to be -adapted, if for every the multivalued random variable is -measurable. It is called measurable, if is a -measurable multivalued random variable, where denotes the Borel -algebra of subsets of I. If is -adapted and measurable, then it is called nonanticipating. Equivalently, X is nonanticipating iff X is measurable with respect to the -algebra , which is defined as follows

where . A multivalued nonanticipating stochastic process is called -integrally bounded, if there exists a measurable stochastic process such that and for a.a. . By , we denote the set of all equivalence classes (with respect to the equality -a.e., denotes the Lebesgue measure) of nonanticipating and -integrally bounded multivalued stochastic processes.

A fuzzy set u in (see [5]) is characterized by its membership function (denoted by u again) and (for each ) is interpreted as the degree of membership of x in the fuzzy set u. As the value expresses “degree of membership of x in” or a “degree of satisfying by x a property”, one can work with imprecise information. Obviously, every ordinary set u in is a fuzzy set, since then if and if .

For a fuzzy set by its -level, , we mean the set and is called the support of u.

Let denote the fuzzy sets such that for every and the mapping is -continuous on . Note that the set can be embedded into by the embedding defined as follows: for we have if , and if .

Addition and scalar multiplication in fuzzy set space can be defined levelwise

where , and .

Let . If there exists such that , then we call w the Hukuhara difference of u and v and we denote it by . Note that . In addition, may not exist, but if it exists it is unique. For and , we have:

- (P1)

- ; and

- (P2)

- the Hukuhara difference exists iff exists. Moreover, .

Define by the expression

The mapping is a metric in . It is known that is a complete metric space, but it is not separable and it is not locally compact. For every , one has (see, e.g., [26])

- (P3)

- ;

- (P4)

- ;

- (P5)

- ;

- (P6)

- ;

- (P7)

- ; and

- (P8)

- .

A mapping is said to be a fuzzy random variable (see [26]), if is an -measurable multivalued random variable for all . It is known from [27] that is the fuzzy random variable iff is -measurable. A fuzzy random variable is said to be -integrally bounded, , if belongs to . By , we denote the set of all -integrally bounded fuzzy random variables, where we consider as identical if holds P-a.e. In the set , one can define a metric by . Then, the metric space is complete (see [28]).

We call a fuzzy stochastic process, if for every the mapping is a fuzzy random variable. We say that a fuzzy stochastic process x is -continuous, if almost all (with respect to the probability measure P) its trajectories, i.e., the mappings are the -continuous functions. A fuzzy stochastic process x is called -adapted, if for every the multifunction is -measurable for all . It is called measurable, if is a -measurable multifunction for all , where denotes the Borel -algebra of subsets of I. If is -adapted and measurable, then it is called nonanticipating. Equivalently, x is nonanticipating iff for every the multivalued random variable is measurable with respect to the -algebra . A fuzzy stochastic process x is called -integrally bounded (), if there exists a measurable stochastic process such that and for a.a. . By , we denote the set of nonanticipating and -integrally bounded fuzzy stochastic processes.

In the whole paper, notation stands for abbreviation of , where are some random elements. In addition, we write instead of , where are some stochastic processes. Similar notations are used for inequalities.

Let , . For such the process x, we can define (see, e.g., [17]) the fuzzy stochastic Lebesgue–Aumann integral which is a fuzzy random variable

Then, (from now on, we do not write the argument ) is understood as . For the fuzzy stochastic Lebesgue–Aumann integral, we have the following properties (see [17]).

Lemma 1.

Let . If , then:

- (i)

- belongs to ;

- (ii)

- the fuzzy process is -continuous;

- (iii)

- and

- (iv)

- for every , it holds

As we mentioned, e.g., in [17,19], it is not possible to define fuzzy stochastic integral of Itô type such that it is not a crisp random variable. Hence, we consider the diffusion part of the fuzzy stochastic differential equation as the crisp stochastic Itô integral whose values are embedded into .

For convenience of the reader, we give also formulation of the Bihari inequality that is useful in the paper.

Lemma 2.

(Bihari’s inequality, see, e.g., Theorem 1.8.2 in [3]). Let and . Let be a continuous nondecreasing function such that for every . Let be a Borel measurable bounded nonnegative function on , and let be a non-negative integrable function on . If then holds for all such that , where , , and is the inverse function of J. Moreover, if and , then for every .

3. Unique Solutions

The purpose of this paper is to study the symmetric fuzzy stochastic differential equations which in their integral form can be written as follows

where , , , is a fuzzy random variable, and are the independent, one-dimensional -Brownian motions.

By applying Properties (P1) and (P2), we obtain an equivalent form of the above equation, i.e.,

where , , , and are the independent one-dimensional -Brownian motions, , , is a fuzzy random variable.

Now, we describe the notion of the solution to Equation (1). Let . Denote .

Definition 1.

A fuzzy stochastic process is called the solution to Equation (1) if:

- (i)

- ;

- (ii)

- x is -continuous; and

- (iii)

- x verifies (1).

If , then x is said to be a local solution, and, if , then x is said to be the global solution.

Definition 2.

Before we begin a deeper theoretical analysis of the task posed in this paper, we present an example illustrating the motivation to study fuzzy stochastic differential equations in their symmetric form. This is done on the basis of considerations and pictures contained in [21].

Example 1.

Let us assume that for modeling bacteria population density a model was chosen in which the instantaneous speed of density changes is proportional to the density at the moment t. It is also known that random density fluctuations should be included in the model. In addition, precise measurements of the initial value are not available, but only their linguistic description, e.g., “around 175" is given. It is also known that the population will be fed by a time unit and not fed by a second unit of time.

It can be expected that the fed population will expand and the number of individuals will increase, which will cause increasing inaccuracy (fuzziness) in assessing the population density obtained from observations under the microscope. The opposite situation should take place when the population is not fed, because the smaller number of individuals will be conducive to less imprecision (fuzziness) in assessing the number of individuals and thus the density. All this forces the model in the form of a symmetric fuzzy stochastic equation that contain integrals on both sides of the equation. According to our knowledge of the phenomenon under study, the following equation may be an appropriate model

where , a and b are some real functions, σ is a real constant, and is a fuzzy set (it could be a fuzzy random variable in general). Of course, this equation can be rewritten as

Assume that it has been established that

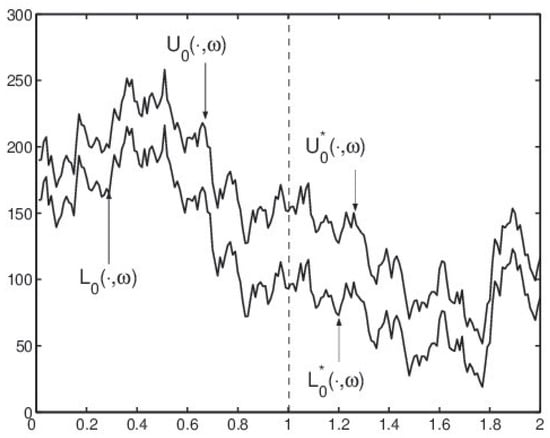

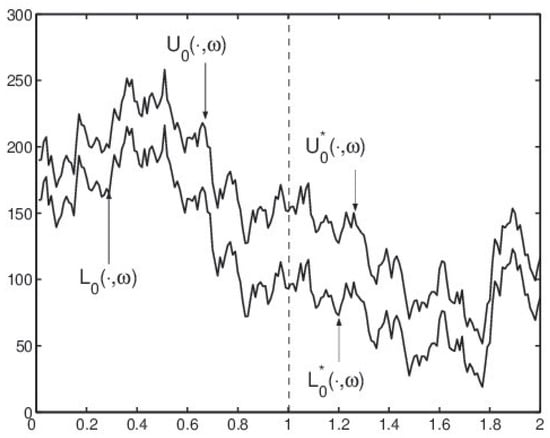

The equation considered above possesses a unique solution x and it is possible to find this solution in explicit form. However, to see the characteristic feature of symmetric Equation (1), we choose a visual presentation of one trajectory of solution support. To this end, let us fix a fuzzy set that will model the initial value “around 175" in such a way that its support satisfies . Let and denote the lower and upper boundary of the solution support, i.e., . In Figure 1, we present a simulation of the solution support trajectory by drawing trajectories of and .

Figure 1.

A trajectory of the support of solution to Equation (2).

The illustration clearly shows that in the first unit of time the length of the interval, which is the support of the solution, increases, while in the next unit of time this length decreases. The length can be an indicator of fuzziness represented in fuzzy set . Such a change in the type of monotonicity would not be possible without considering a symmetric equation.

Although an explicit form of the solution can be determined for equation in the example above, such a task is usually very difficult, if not impossible. Obtaining a solution to stochastic differential equations in an explicit form is very rare, therefore numerical methods can be helpful to obtain approximate solutions. However, unlike the use of numerical methods in issues of deterministic equations, their use for stochastic equations has some limitations. Namely, for stochastic equations, it is usually not possible to simulate all or almost all trajectories of solution. On the other hand, the use of numerical methods is really legitimate only if we are sure that the equation has a solution and that it is the only one.

In this paper, our aim is to show that the symmetric fuzzy stochastic differential Equation (1) possesses unique solution when the drift coefficients and diffusion coefficients satisfy a generalized Lipschitz condition, which is obviously weaker than the Lipschitz condition used in [22]. This is justified from a theoretical and practical point of view. First, it is a step in the development of the theory of such equations, and secondly it allows a larger class of mappings from which drift and diffusion equation coefficients can be selected and a unique solution guaranteed.

Here, we collect all the general requirements that we impose on the equation coefficients of (1). In the paper we require that , , () satisfy:

- (A0)

- ;

- (A1)

- the mappings are -measurable and are -measurable;

- (A2)

- P-a.a. it holdsfor every and for any , andfor every , for any and , where is a continuous, concave, nondecreasing function such that , for , and ;

- (A3)

- there exists a constant such that P-a.a. it holds: for everyand for every andand

- (A4)

- there exists a constant such that for every the mappings , where , described asare well defined (in particular, the Hukuhara differences do exist).

Let us notice that, if , where L is a positive constant, then (A2) reduces to the Lipschitz condition considered in [22]. Therefore, the condition under consideration here is weakened compared to the previous one and extends significantly the set of drift and diffusion mappings that ensure the existence of a unique solution. Some examples of functions different from are known in the literature [29], namely and defined as

where is sufficiently small and () denotes left-sided derivative of at .

To prove that symmetric fuzzy stochastic differential equations possess unique solutions under conditions presented above, we use a sequence of successive approximations . In what follows, we derive a series of properties of the sequence . First, we show that is a proper fuzzy stochastic process for every .

Lemma 3.

Let and for satisfy (A0)–(A4). Then, are -continuous, nonanticipating fuzzy stochastic processes that belong to .

Proof.

Since , we immediately have . Denote and let us fix . We begin with an analysis on the interval . Let us notice that the mappings

- ,

- ,

are the nonanticipating fuzzy stochastic processes and

- for

are the single-valued stochastic processes because of measurability Assumption (A1). Further, let us observe that

and by (A2) and (A3)

Due to Jensen’s inequality,

which means that the process is -integrably bounded. Similar calculations show that is -integrably bounded as well and for are square integrable. Hence, by Lemma 1 (i) and (ii), the fuzzy stochastic processes

are nonanticipating, -integrably bounded, and -continuous, and obviously the single-valued Itô processes

for are nonanticipating, square integrable, and continuous.

Since ⊕ and ⊖ are the inner operations in , and the sum and Hukuhara difference of two fuzzy random variables are still fuzzy random variables and in view of (A4), we conclude that

is well defined for and is nonanticipating, -integrably bounded and -continuous fuzzy stochastic process. Now, having defined on the interval we can move on to defining it on the second interval by following exactly the same steps as above. This procedure is repeated until we reach the right boundary of the interval . □

Below, we state an observation on boundedness of the sequence .

Lemma 4.

Let satisfy (A0)–(A4). Then, there exists a positive constant such that for every

Proof.

Let us observe that for

Now, applying Properties (P4), (P6), and (P5), we get

Further,

By Lemma 1 and the Doob inequality, we obtain

By Assumptions (A2) and (A3), we infer that

Since the function is concave, there exist positive constants a and b such that for . Hence

This leads us to

Now, applying the Gronwall inequality, we obtain

for every . Hence, it follows easily that , where which ends the proof. □

The next property indicates a uniform Hölder continuity of the sequence .

Lemma 5.

Let the assumptions of Lemma 4 be satisfied. Then, there exists a positive constant such that for every and every ,

Proof.

Let be as in the assumptions. Starting with

and using Properties (P4), (P8), and (P5), we obtain

Due to Lemma 1 and the Itô isometry, we have

and further

Invoking Assumptions (A2) and (A3),

By Jensen’s inequality and nondecreasiness of ,

Applying Lemma 4, we obtain

where .

Lemma 6.

Let the assumptions of Lemma 4 be satisfied. Then,

Proof.

Let us fix . Without loss of generality, we may assume that . Observe that, for , we have

Now, using Property (P8) together with Lemma 1 and Doob’s inequality, we obtain

and further

Assumption (A2) and Jensen’s inequality lead us to

By Lemma 5, we get

where . Applying Lemma 2, we have

for every . Owing to Lemma 2 and properties of function J from this lemma, we obtain

This allows us to infer that . □

As mentioned above, Conditions (A0)–(A4) assure the existence of a unique solution to Equation (1). This fact, written below, constitutes a first main result of the paper and the the properties listed above are helpful in proving it. Although the method of proving is already signaled in [23], we present it fully here for the convenience of the reader and for completeness.

Theorem 1.

Let , and () satisfy (A0)–(A4). Then, Equation (1) possesses a unique solution .

Proof.

Let us observe that owing to Lemma 6

where . Since is a complete metric space, we claim that for every there exists a unique fuzzy random variable such that

Let us define a fuzzy stochastic process as . Then, the fuzzy stochastic process x is -adapted. Due to the Markov inequality we obtain that for every

Hence, we can infer that there exists a subsequence of the sequence such that

Thus, the process x is -continuous and consequently it is measurable. Since x is also -adapted, it is nonanticipating. In addition, since for every , we have

This implies that . Moreover, applying Lemma 4, we infer that

We can also infer that

In what follows, we show that x is a solution to Equation (1). To this aim, let us observe that

where

and

By Equation (3), the expression converges to zero as ℓ goes to infinity, and it can be verified that

where . Thus,

Applying Lemma 5, we obtain

By the properties of and in view of Equation (3), the right-hand side of the latter inequality converges to zero. Thus,

which implies that

This shows that x is a solution to Equation (1). Now, we prove that x is a unique solution. To this end, assume that is another solution to Equation (1). Then, for we have

Hence,

Invoking Lemma 2, we get

Therefore,

which implies that

This proves uniqueness of the solution x. The proof is completed. □

4. Stability of Solution

In this section, we examine a certain basic type of stability of solutions to symmetric fuzzy stochastic differential equations in order to show that the theory of such equations with the generalized Lipschitz condition is well-posed. By stability, we mean here an insensitivity of solution to small changes in equation data, i.e., initial value or diffusion or drift coefficients. It is obvious that this kind of stability must be ensured for potential practical applications, because in practice, due to technological limitations and the lack of precision of measurements and imprecision of human knowledge, an inaccurate model of initial value or drift or diffusion is most often available. However, assuming that given equation data have been determined as best as possible, i.e. they are very close to actual data, the stability is to ensure closeness of solution of equation with disturbed data and solution of equation that actually corresponds to studied phenomenon. Therefore, slight data disturbances will not cause big changes in solutions.

Let us consider two symmetric fuzzy stochastic differential equations. The first one is exactly Equation (1), the second one is

and let denote solutions to Equations (1) and (4) (provided they exist), respectively. It is easy to observe that both equations differ only in the initial value, the remaining data are identical. The essence of current research is to justify the stability of the solution relative to small changes in the initial value.

Theorem 2.

Let the fuzzy random variables satisfy Condition (A0). Suppose satisfy (A1)–(A3). Assume that the condition (A4) is satisfied by and with the same constant . Then, the unique solutions to Equations (1) and (4) satisfy

where the function J is as in Lemma 2 and is its inverse.

Proof.

Applying Lemma 1 and the Doob inequality, we get

By Assumption (A2) and Jensen’s inequality,

Finally, by Lemma 2,

which completes the proof. □

From the above theorem, it can be seen that small changes in the initial value cannot cause large changes in solutions. This allows us to infer the property of continuous dependence of solution with respect to the initial value. Indeed, consider Equation (1) and

Corollary 1.

Let the fuzzy random variables satisfy (A0). Let satisfy (A1)–(A3). Suppose that Condition (A4) is satisfied with the same constant for each of systems , , Assume that

Further analysis is related to examining the impact on the solution resulting from changes in drift and diffusion coefficients. Hence, we consider Equation (1) and

to investigate continuous dependence of solution to Equation (1) with respect to coefficients and ’s. Let denote solutions to Equations (1) and (6), respectively.

Theorem 3.

Let the fuzzy random variable satisfy (A0). Let the systems and satisfy (A1)–(A3). Assume that Condition (A4) is satisfied with the same constant for both systems and . Then, for the unique solution to Equation (1) and the unique solution to Equation (6), we have

where

and the function J is as in Lemma 2 and is its inverse.

Proof.

The existence of the unique solutions x to Equation (1) and z to Equation (6) is ensured by Theorem 1. For , we have

where

By Lemma 2, we get

and this ends the derivation. □

From the above proof, we can see that the solution shows stable behavior in the light of small changes in drift and diffusion coefficients. Indeed, the lower is the value of the constant c, the lower is the value of the expression .

5. Application to Symmetric Multivalued Stochastic Differential Equations

In this section, we collect some results concerning symmetric multivalued stochastic differential equations of the form

where , , , is a multivalued random variable, and are the independent, one-dimensional -Brownian motions.

All the results established here follow directly from the findings presented in the previous part of the paper, and this is because ordinary sets are also fuzzy sets. However, due to independent research conducted on the subject of multivalued differential equations [30], it is worth mentioning and highlighting the results obtained by us for such equations. It is also worth recalling that examination only multivalued equations is not enough to state that similar results are obtained for fuzzy equations. For example, in our case, it should be remembered that the existence of Hukuhara differences for ordinary sets does not imply the existence of such a difference for fuzzy sets. There are many more subtle differences between fuzzy and multivalued analysis, which only emphasizes that conducting research on fuzzy equations requires accuracy and caution. Multivalued equations are a special case of fuzzy equations and not the other way around. However, as mentioned above, in many cases, one can apply the restriction to ordinary sets and therefore we present below the list of results obtained for this type of equations.

Firstly, let us notice that Equation (7) can be rewritten in its equivalent form as

where is a set-valued random variable, , and are the independent one-dimensional -Brownian motions. The first and the second integral in Equation (8) are the set-valued stochastic Lebesgue integral, while the next integrals are the -valued stochastic Itô integrals.

Denote , .

Definition 3.

If , then X is said to be a global solution to Equation (8). A (local or global) solution to Equation (8) is unique iff , where is any other solution to Equation (8).

All the results established here for symmetric multivalued stochastic differential Equation (8) involve the following conditions:

- (S0)

- ;

- (S1)

- the mappings are -measurable and are -measurable;

- (S2)

- P-a.a. it holdsfor every and for any , andfor every , for any and , where is a continuous, concave, nondecreasing function such that , for , and ;

- (S3)

- there exists a constant such that P-a.a. it holds: for everyand for every andand

- (S4)

- there exists a constant such that for every the mappings , where , described asare well defined (in particular, the Hukuhara differences do exist).

Proceeding as in the previous section, all properties of the sequence are obtained, allowing to show that there exists its convergent subsequence and its limit is the unique solution of the equation. Therefore, the first main result for Equation (8) is obtained and stated below.

Corollary 2.

Suppose that and meet Conditions (S0)–(S4). Then, Equation (8) possesses a unique (possibly local) solution .

Now, we want to point out that the unique solutions of symmetric multivalued stochastic differential equations with the generalized Lipschitz condition are stable relative to small changes in the initial value. To this aim, we focus on Equation (8) and

Corollary 3.

Finally, we mention the fact on stability of multivalued solution to Equation (8) with respect to small changes of drift and diffusion coefficients. Let us consider Equation (8) and

Corollary 4.

Let the multivalued random variable satisfy (S0). Let the systems of data and satisfy (S1)-(S3). Suppose that Condition (S4) is satisfied with the same constant for both systems and . Then, for the unique solution to Equation (8) and the unique solution to Equation (10) it holds

where

and the function J is as in Lemma 2 and is its inverse.

6. Conclusions

Writing fuzzy stochastic differential equations in a form reminiscent of the classic form of single-valued stochastic differential equations with integrals on the right side of the equation leads to the fact that the values of solutions of such fuzzy equations have a non-decreasing fuzziness as the time variable increases. This sometimes may not be comfortable, especially if the construction of the model assumes that the fuzziness of values should decrease. With such assumptions, models using fuzzy stochastic differential equations with integrals on the left side of the equation ensure that this assumption is met. In this paper, we consider symmetric fuzzy stochastic differential equations with stochastic integrals placed symmetrically on both sides of the equation. This allows capturing the features of both previous equations. This generalization is natural and allows obtaining solutions whose fuzzy values can have fuzziness that changes monotonicity over time.

We show that, in considering the existence of a unique solution of symmetric fuzzy stochastic differential equations, we can assume a weaker condition for the coefficients of the equation than the one imposed in [22]. We already signaled this during a conference [23], and now we provide an exhaustive justification for this fact based on proving a series of properties of a certain sequence that converges to the solution of the equation. The analysis of the distance of solutions to two problems of symmetric fuzzy stochastic differential equations with slightly different initial conditions and equations with slightly different drift and diffusion coefficients allows stating that solutions of symmetric fuzzy stochastic differential equations with the generalized Lipschitz condition behave stably in view of small changes of the initial value and coefficients. This implies continuous dependence of the solution on the initial value and coefficients, which is the desired property from a practical point of view. We also note that all the results obtained can be used to consider symmetric multivalued stochastic differential equations.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the anonymous referees for their constructive comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Arnold, L. Stochastic Differential Equations: Theory and Applications; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Gihman, I.I.; Skorohod, A.V. Stochastic Differential Equations; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, X. Stochastic Differential Equations and Applications; Horwood Publishing Limited: Chichester, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Øksendal, B. Stochastic Differential Equations: An Introduction with Applications; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zadeh, L.A. Fuzzy Sets. Inf. Control 1965, 8, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. From Computing with Numbers to Computing with Words—From Manipulation of Measurements to Manipulation of Perception. Int. J. Appl. Math. Comput. Sci. 2002, 12, 307–324. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, H.-J. Fuzzy Set Theory and Its Applications; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Boston, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.B.; Chakma, A.; Zeng, G.M.; Liu, L. Integrated Fuzzy-stochastic Modeling of Petroleum Contamination in Subsurface. Energy Sources 2003, 25, 547–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Lee, B.; Guo, L. Optimal Tracking Design for Stochastic Fuzzy Systems. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2003, 11, 796–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wu, R.; Pan, D. Mean Square Exponential Stability of Impulsive Stochastic Fuzzy Cellular Neural Networks with Distributed Delays. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 6294–6299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, P.; Huang, L. On pth Moment Exponential Stability of Stochastic Fuzzy Cellular Neural Networks with Time-varying Delays and Impulses. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2013, 2013, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Möller, B.; Graf, W.; Beer, M. Safty Assessment of Structures in View of Fuzzy Randomness. Comp. Struct. 2003, 81, 1567–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Heiner, M.; Yang, M. Fuzzy Stochastic Petri Nets for Modeling Biological Systems with Uncertain Kinetic Parameters. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Watada, J. Fuzzy Stochastic Optimization; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, L.; Chen, B.; Zhang, B.; Peng, H. A Hybrid Fuzzy Stochastic Analytical Hierarchy Process (FSAHP) Approach for Evaluating Ballast Water Treatment Technologies. Environ. Syst. Res. 2013, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmeškal, Z. Generalised Soft Binomial American Real Option Pricing Model (Fuzzy-stochastic Approach). Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2010, 207, 1096–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowski, M.T. Strong Solutions to Stochastic Fuzzy Differential Equations of Itô Type. Math. Comput. Model. 2012, 55, 918–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowski, M.T. Itô Type Stochastic Fuzzy Differential Equations with Delay. Syst. Control Lett. 2012, 61, 692–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowski, M.T. Some Properties of Strong Solutions to Stochastic Fuzzy Differential Equations. Inf. Sci. 2013, 252, 62–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowski, M.T. Fuzzy Stochastic Differential Equations of Decreasing Fuzziness: Approximate Solutions. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2015, 29, 1087–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowski, M.T. Stochastic Fuzzy Differential Equations of a Nonincreasing Type. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simulat. 2016, 33, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowski, M.T. Bipartite Fuzzy Stochastic Differential Equations. Math. Probl. Eng. 2016, 2016, 3830529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowski, M.T. On Bipartite Fuzzy Stochastic Differential Equations. In Proceedings of the 8th Interational Joint Conference on Computational Intelligence (IJCCI 2016)—Volume 2: FCTA; SCITEPRESS- Science and Technology Publications Lda.: Porto, Portugal, 2016; pp. 109–114. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.; Papageorgiou, N.S. Handbook of Multivalued Analysis, Vol. I: Theory; Kluwer Academic: Boston, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hiai, F.; Umegaki, H. Integrals, Conditional Expectations, and Martingales of Multivalued Functions. J. Multivar. Anal. 1977, 7, 149–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, M.L.; Ralescu, D.A. Fuzzy Random Variables. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 1986, 114, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, S.Y.; Kim, Y.K.; Kwon, J.S.; Choi, G.S. Convergence in Distribution for Level-continuous Fuzzy Random Sets. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2006, 157, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.H. Mean-square Integral and Differential of Fuzzy Stochastic Processes. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1999, 102, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T. On Successive Approximation of Solutions of Stochastic Differential Equations. J. Math. Kyoto Univ. 1981, 21, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmikantham, V.; Gnana Bhaskar, T.; Vasundhara Devi, J. Theory of Set Differential Equations in Metric Spaces; Cambridge Scientific Publishers: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).