Abstract

During the last two centuries, after the question asked by Euler concerning mutually orthogonal Latin squares (MOLS), essential advances have been made. MOLS are considered as a construction tool for orthogonal arrays. Although Latin squares have numerous helpful properties, for some factual applications these structures are excessively prohibitive. The more general concepts of graph squares and mutually orthogonal graph squares (MOGS) offer more flexibility. MOGS generalize MOLS in an interesting way. As such, the topic is attractive. Orthogonal arrays are essential in statistics and are related to finite fields, geometry, combinatorics and error-correcting codes. Furthermore, they are used in cryptography and computer science. In this paper, our current efforts have concentrated on the definition of the graph-orthogonal arrays and on proving that if there are MOGS of order , then there is a graph-orthogonal array, and we denote this array by -In addition, several new results for the orthogonal arrays obtained from the MOGS are given. Furthermore, we introduce a recursive construction method for constructing the graph-orthogonal arrays.

2010 Mathematics Subject Classification:

05C70; 05B30

1. Introduction

A graph is a couple , where is a set of vertices and is a set of edges, and . The two ends of an edge are called two adjacent vertices. The set of pairwise non-adjacent vertices is called an independent set. A graph is called simple if it has no loops and multiple edges. Several research papers of graph theory concerning the study of simple graphs have been produced [1].

Definition 1.

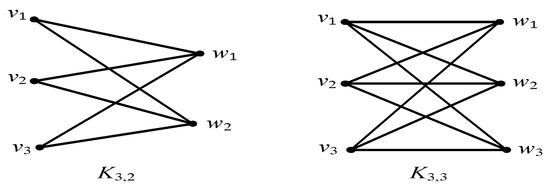

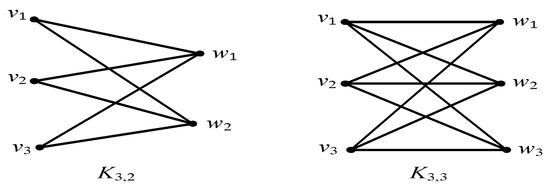

Letandbe positive integers. A complete bipartite graph onvertices, denoted byis a simple graph with distinct verticesandthat satisfies the following properties: For all, and for all

- 1.

- There exists an edge from each vertexto each vertex.

- 2.

- There is no edge from any vertexto any other vertex.

- 3.

- There is no edge from any vertexto any other vertex.

Definition 2.

Figure 1.

The complete bipartite graphs and

Bipartite graphs assume conspicuous functions in graph theory [2]. For instance, bipartite graphs are very helpful for studying problems of matching, such as job matching problem. Furthermore, bipartite graphs have very essential roles in theoretical consideration. For example, bipartite graphs can be used to describe the multipartite graphs [3].

A Latin square with order is an matrix whose entries are taken from a set with , where all elements of appear precisely one time in each row and each column. A pair of Latin squares with order are called orthogonal to each other if when one is overlaid on the other the ordered pairs () of corresponding entries contain all possible pairs, . A family of Latin squares of order (any two of them being orthogonal) is said to be a set of mutually orthogonal Latin squares (MOLS). The applications of MOLS are common, famous, and can be studied in many textbooks (see Laywine et al., [4] as an example). The reader can see [5], for a brief review of MOLS constructions.

Assume that is a subgraph of with size (number of its edges). A square matrix of order is called a -square if each element in appears precisely times, and all graphs where are isomorphic to The index set for the rows and columns of is the group . The two graph squares have the property that, when superimposed, every ordered pair occurs exactly once. Thus the squares are orthogonal. A set of graph squares is pairwise orthogonal, or a collection of MOGS, if and are orthogonal for each . For a survey of MOGS, see [6,7,8,9,10,11].

Hereafter, we will need the Kronecker product of the graph squares. As such, assume that is a graph square of order and that is a graph square of order . Let us indicate the entry at row and column of by In the same way, we indicate the entry of by Hence the Kronecker type product of and is the square presented by

Such that each entry of is the matrix

For clearing this Kronecker type product structure, for assume

Then, the Kronecker product’s construction gives the ensuing 6 × 6 matrix, whose entries are ordered pairs

Orthogonal arrays are essential in statistics where they are basically utilized in experimental design, hence they are immensely important in medicine, manufacturing and agriculture. The applications of orthogonal arrays in the statistical design of experiments are common, well-known, and can be studied from many textbooks (for instance, see Hedayat et al., [12]). Furthermore, they are used in cryptography and computer science. Officially, an orthogonal array can be characterized as follows.

Definition 3.

[12]Anmatrixwhose entries are taken fromis called an orthogonal array withlevels, strengthand indexfor somein the rangeif allsubarrays ofcontaining each-tuple rely onpreciselytimes in a row. The integersandare considered the parameters of the orthogonal array which will be symbolized byThe orthogonal arrays with index unityare concerned here.

Example 1.

The following array is an orthogonal array relying on two levels (= 2, i.e., all the elements in the array take only two values, 0 or 1), with a strength of three, of index unity, with eight runs and with four factors (variables). In an orthogonal array with a strength of three (with two levels), by taking any three column we will find each of the eight possibilities 000, 010, 001, 011, 101, 100, 110 and 111 equally as often.

A few creators like to speak of an orthogonal array as a array rather than an array. This saves the number of lines. The transposed array will be shown in our illustrations to save lines. Certain orthogonal arrays can be utilized to build MOLS, and conversely MOLS give a tool for building orthogonal arrays. Although Latin squares have numerous valuable properties, for some measurable applications these structures are excessively restrictive. The broader ideas of graph squares and MOGS offer greater adaptability. As such, MOGS likewise give an apparatus for building orthogonal arrays. This latter aspect is what concerns us in this paper.

The remaining part of the work is arranged as follows: Graph-orthogonal arrays by mutually orthogonal graph squares are given in Section 2. Recursive constructions of the graph-orthogonal arrays are presented in Section 3. For illustration, the applications of the graph-orthogonal arrays in the design of experiments are shown in Section 4. Finally, the conclusion is given in Section 5.

2. Graph-Orthogonal Arrays by Mutually Orthogonal Graph Squares

Many results of Latin squares can be stated in terms of transversal designs, defined as follows: A transversal design with groups of size and index denoted by , is a triple , where

- is a set of elements;

- is a family of -sets or groups which form a partition of ;

- is a family of -sets or blocks of elements so that each -set in intersects each group in exactly one element, and any pair of elements from different groups occurs together in exactly blocks in

The partition of a set is a collection of disjointed subsets of whose union is . The disjoint means that for any two distinct subsets and we find that

Example 2.

Table 1.

The groups and blocks of a transversal design.

Theorem 1.

([4]). The existence of a transversal design is equivalent to the existence of a set of MOLS of order

Example 3.

The transversal design given in Example 2 can be used to give a better illustration of Theorem 1 by constructing a pair of MOLS, and, of order three. For more illustration, the symbols in cell (1, 1) of the Latin squares will be determined. Consider the elements of the design. They are together in blockwith the elementsAs such, the element in cell (1,1) ofis 1, while that ofis 1.Table 2 illustrates the construction and the Latin squaresand

Table 2.

The construction and the Latin squares and for Example 3.

It is easy to check that an orthogonal array has a transversal design, and vice versa. The preceding is summarized by the following.

Theorem 2.

([4]). The following are equivalent:

- 1.

- MOLS of order;

- 2.

- a transversal design;

- 3.

- an orthogonal array.

Example 4.

The following array (from Theorem 2 and the two MOLS of order three given in Example 3) gives an example of an orthogonal array The transpose of this array is as follows, where the first two rows represent the position after calculating its elements modulo 3.

Note that after obtaining the orthogonal array from the MOLS, we can add additional two rows (the first and the second rows). These two rows represent the position of the cells in the MOLS.

As such, it is easy to check that an orthogonal array is a transversal design, and vice versa.

Definition 4.

If we havemutually orthogonal-squares, then by converting these squares to anarray by juxtaposing therows of the square and transposing, we get the graph-orthogonal array-by combining these arrays to form anarray.

In this section, we prove that if there are mutually orthogonal -squares of order , then there is a - Proposition 1, there are some new results for the orthogonal arrays as directly applied to Proposition 1.

Proposition 1.

The existence ofmutually orthogonal-squares based onsymbols implies the existence of an-orthogonal array-

Proof.

The technique of the construction can be shown as follows. Convert each of the mutually orthogonal -squares to an array by juxtaposing the rows of the -square and transposing. Then, these arrays are combined to construct an array. Since there are mutually orthogonal -squares based on symbols, the number of the levels equals , since the -squares are mutually orthogonal, then the superimposition of any two columns of the array gives , the array has strength two. □

Example 5.

We have the three mutually orthogonal-squaresand; see [12]Thenwe obtain the array-this array can be represented by the, whereis the transpose of

All the following results are based onProposition 1 andthe existence of MOGS for some classes of graphs that can be used as ingredients for obtaining new graph-orthogonal arrays.

Consider the addition is calculated moduloof orderSee[11] for the ingredients fromtoThese ingredients are as follows.

- (I)

- Themutually orthogonal-squares areis a primeand.

- (II)

- Themutually orthogonal-squares areand

- (III)

- If, thenmutually-and.

- (IV)

- I, thenmutually-let,then

- (V)

- Themutually orthogonal-squares arewhereis a prime greater than; see [9].

Theorem 3.

The existence ofmutually orthogonal-squares based onsymbols implies the existence of a-orthogonal array-

Proof.

The technique of the construction can be shown as follows. Convert each of the mutually orthogonal -squares (Ingredient ) to an array by juxtaposing the rows of the -square and transposing. Then, these arrays are combined to construct an array. Since there are mutually orthogonal -squares based on symbols, the number of the levels equals , since the -squares are mutually orthogonal, the superimposition of any two columns of the array gives , the array has strength two. □

Theorem 4.

The existence ofmutually orthogonal-squares based onsymbols implies the existence of an-orthogonal array-

Proof.

The technique of the construction can be shown as follows. Convert each of the mutually orthogonal -squares (Ingredient ) to an array by juxtaposing the rows of the -square and transposing. Then, these arrays are combined to construct an array. Since there are mutually orthogonal -squares based on symbols, the number of the levels equals , since the -squares are mutually orthogonal, the superimposition of any two columns of the array gives , the array has strength two. □

Lemma 1.

The existence ofmutually orthogonal-squares based onsymbols implies the existence of an-orthogonal array-

Proof.

The technique of the construction can be shown as follows. Convert each of the mutually orthogonal -squares (Ingredient ) into an array by juxtaposing the rows of the -square and transposing. Then, these arrays are combined to construct an array. Since the mutually orthogonal -squares are based on symbols, the number of the levels equals , since the (-squares are mutually orthogonal, then the superimposition of any two columns of array gives , the array has strength two. □

Lemma 2.

The existence offour mutually orthogonal-squares based onsymbols implies the existence of an-orthogonal array-

Proof.

The technique of the construction can be shown as follows. Convert each of the mutually orthogonal -squares (Ingredient ) to a array by juxtaposing the seven rows of the -square and transposing. Then, these arrays are combined to construct an array. Since the mutually orthogonal -squares are based on symbols, the number of the levels equals , since the (-squares are mutually orthogonal, the superimposition of any two columns of the array gives the array has strength two. □

Theorem 5.

The existence ofmutually orthogonal-squares based onsymbols implies the existence of a-orthogonal array-

Proof.

The technique of the construction can be shown as follows. Convert each of the mutually orthogonal -squares (Ingredient ) into an array by juxtaposing the rows of the -square and transposing. Then, these arrays are combined to construct an array. Since the mutually orthogonal -squares are based on symbols, the number of the levels equals , since the -squares are mutually orthogonal, then the superimposition of any two columns of the array gives , the array has strength two. □

Lemma 3.

The existence ofthree mutually orthogonal-squares based onsymbols implies the existence of an-orthogonal array-

Proof.

We have mutually orthogonal -squares; see [6]. The three mutually orthogonal -squares of order are defined as follows, where and

Convert each of the mutually orthogonal -squares into an array by juxtaposing the rows of the -square and transposing. Then, these arrays are combined to construct a array,

Since the mutually orthogonal -squares are based on symbols, the number of levels equals , since the three -squares are mutually orthogonal, the superimposition of any two columns of the array gives 16 different ordered pairs i.e., the array has strength two. □

Lemma 4.

The existence ofmutually orthogonal-squares based onsymbols implies the existence of a-orthogonal array-

Proof.

We have mutually orthogonal -squares; see [7]. The three mutually orthogonal -squares of order are defined as follows, where and

Convert each of the three mutually orthogonal 4 × 4 -squares into a 16 × 1 array by juxtaposing the four rows of the -square and transposing. Then, these arrays are combined to construct a 16 × 3 array, ,

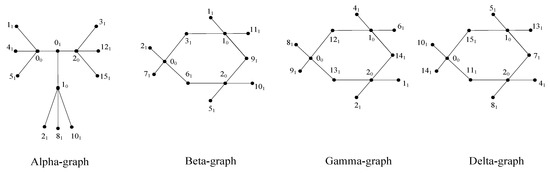

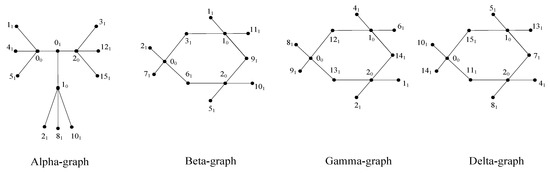

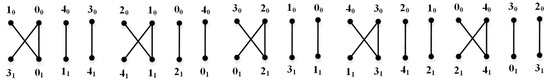

Since the mutually orthogonal -squares are based on symbols, the number of levels equals four, since the three -squares are mutually orthogonal, then the superimposition of any two columns of the array gives 16 different ordered pairs, i.e., the array has strength two. The -, T, can be represented by the edge decomposition (as the graph squares), as shown in Figure 2. □

Figure 2.

Edge decomposition of corresponding to T.

In the following example, we convert the - to mutually orthogonal -squares by reversing the technique in the proof of Proposition 1.

Example 6.

We have the array where

Now, we convert this array into three mutually orthogonal squares, and

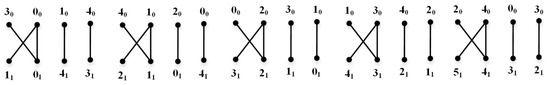

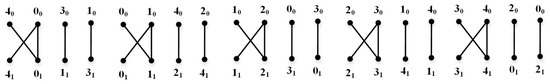

It is clear that the squares are three mutually orthogonal -squares. See Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5.

Figure 3.

First edge decomposition of by corresponding to .

Figure 4.

Second edge decomposition of by corresponding to

Figure 5.

Third edge decomposition of by corresponding to

3. Recursive Constructions of the Graph-Orthogonal Arrays

The production of graph-orthogonal arrays, defined below, is one strategy involving a systematic gluing together of graph-orthogonal arrays of small orders to obtain sets of graph-orthogonal arrays of larger orders.

Hereafter, we will directly represent the graph-orthogonal array as a array rather than an array.

Definition 5.

Assume thatis a graph-orthogonal array of orderand thatis a graph-orthogonal array of order. Let every row of the arraybe divided intosets where every set containselements, and the arrayis divided intosets and every set contains elements.

whereandThen

As an illustration of this product construction, let

Then the product construction yields the following array, whose elements are ordered pairs

In [6], El-Shanawany et al. proved that if , and then Proposition 3.2, where .

Proposition 2.

([6]) If there are -MOGS of order of the graph and -MOGS of order of the graph , then there are -MOGS of order of the graph

Proposition 3.

Assume thatis a-orthogonal array of orderand thatis an-orthogonal array of order, thenis a-orthogonal array of order.

Proof.

Let be the mutually orthogonal graph squares of order for the graph , and be the mutually orthogonal graph squares of order for graph

Then, by Proposition 2, the Kronecker product of and , gives the mutually orthogonal -square of order

Let

As such, by Proposition 1, we can construct the -orthogonal array of order as follows,

which represents the product of the orthogonal arrays,

defined by Definition 5. □

Example 7.

To illustrate Proposition 3, let

Note:The productgives a new graph-orthogonal array different from the graph-orthogonal array constructed by the product Furthermore, we can generalize Proposition 3 by the following Proposition 4, which can be proven by the same technique followed in the proof of Proposition 3.

Proposition 4.

Assume thatis a-orthogonal array of order,ThenXiis a-orthogonal array of order .

Proof.

It follows from Proposition 3. □

4. Applications of the Graph-Orthogonal Arrays in the Design of Experiments

The design of experiments is the main application of orthogonal arrays. The rows of the orthogonal arrays represent the tests (runs) or experiments to be implemented. For example, test plots of crops to be grown, integrated circuits to be etched, and so on. The columns of orthogonal arrays represent the different variables (factors) which are analyzed in order to know their effects. The entries in the orthogonal array determine the levels of the variables. If 11100 is a row in an orthogonal array, this may mean that in this experiment the first, second and third variables are at their “high” levels, and the fourth and fifth variables at their “low” levels. If the experiment is based on an orthogonal array with strength , then we find that all the possible combinations of for the factors will occur together equally as often. Therefore, the purpose is to investigate the effects of the factors and how the factors interact. Finally, the orthogonal arrays are used to determine which level combinations are to be implemented. Now, we introduce an application of the -orthogonal array - in the design of experiments; this array is derived from Lemma 4 by using . This array is represented by the matrix where

Table 3 presents 16 experimental runs. It is clear that these experimental runs represent the rows of the orthogonal array -. Similarly, all the other results in the paper can be used for the design of several experiments.

Table 3.

16 experimental runs.

5. Conclusions

Mutually orthogonal Latin squares (MOLS) are used for constructing several orthogonal arrays, but the Latin squares are excessively restrictive. The more general concepts of mutually orthogonal graph squares (MOGS) offer more flexibility. MOGS are considered a generalization of the MOLS. Orthogonal arrays are essential in statistics and are related to finite fields, combinatorics, geometry, and error-correcting codes. The constructions of graph-orthogonal arrays have been investigated in the presented paper. This paper is the first that provides the mutually orthogonal graph squares as a tool for constructing the graph-orthogonal arrays. Furthermore, we introduced recursive constructions of the graph-orthogonal arrays.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.H., A.E.-M. data curation: M.H., A.E.-M., M.S.M. formal analysis: M.H., A.E.-M., M.S.M. funding acquisition: M.H., A.E.-M., M.S.M. investigation: M.H., A.E.-M., M.S.M. methodology: M.H., A.E.-M., M.S.M. project administration: M.H., A.E.-M., M.S.M. software: M.H., A.E.-M., M.S.M. supervision: M.H., A.E.-M., M.S.M. validation: M.H., A.E.-M., M.S.M. visualization: M.H., A.E.-M. writing—original draft: M.H., A.E.-M., M.S.M. writing—review and editing: M.H., A.E.-M., M.S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received funding from “Taif University Researchers Supporting Project number (TURSP-2020/160), Taif University, Taif, Saudi Arabia”.

Acknowledgments

Taif University Researchers Supporting Project number (TURSP-2020/160), Taif University, Taif, Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

- Bondy, J.A.; Murty, U.S.R. Graph Theory with Applications; Elsevier Science Publishing Co., Inc.: London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Bondy, J.A.; Murty, U.S.R. Graph Theory; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Higaz, M.; El-Mesady, A.; Mahmoud, E.E.; Alkinani, M.H. Circular intensely orthogonal double cover design of balanced complete multipartite graphs. Symmetry 2020, 12, 1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laywine, C.F.; Mullen, G.L. Discrete Mathematics Using Latin Squares; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Colbourn, C.J.; Dinitz, J.H. Mutually orthogonal latin squares: A brief survey of constructions. J. Stat. Plan. Inference 2001, 95, 9–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shanawany, R.; El-Mesady, A. Mutually orthogonal graph squares for disjoint union of stars. ARS COMBINATORIA 2020, 149, 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- El-Shanawany, R. On mutually orthogonal disjoint copies of graph squares. Note di Matematica 2016, 36, 89–98. [Google Scholar]

- El-Shanawany, R.; El-Mesady, A.; Shaaban, S.M. Mutually orthogonal graph squares for disjoint union of paths. Appl. Math. Sci. 2018, 12, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shanawany, R. On mutually orthogonal graph-path squares. Open J. Discret. Math. 2016, 6, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampathkumar, R.; Srinivasan, S. Mutually orthogonal graph squares. J. Comb. Des. 2009, 17, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shanawany, R. Orthogonal Double Covers of Complete Bipartite Graphs. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Rostock, Rostock, Germany, December 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hedayat, A.S.; Sloane, N.J.A.; Stuffken, J. Orthogonal Arrays: Theory and Applications; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).