Abstract

The complex topography and harsh natural environment of the Loess Plateau in Longzhong have been suffering from an undefined living circle structure, which has hindered rural planning and development. A rural community living circle is a spatial unit centered on meeting the needs of villagers, within which various service facilities are rationally allocated within a specific spatial scope. To refine its spatial patterns, the concept of living circles was introduced to address travel challenges. The extent of these living circles is affected by the accessibility of public service facilities and barriers to travel. Using land use data, DEM, population density, and road networks, this study employed the MCR model, gravity model, and ArcGIS spatial analysis to examine the patterns of rural community living circles. The focus was on analyzing the living circle structure of rural communities on the Loess Plateau in Longzhong, considering both natural and artificial environmental constraints. The results show: (1) Rural community living circles present multi-scale spatial features. The basic living circle covers a 15 min slow-travel area. The central living circle corresponds to village-level needs, accessible within 35 min by both slow and motorized travel. The town living circle covers a 10 km radius, reachable within 60 min by a mix of transport modes. The county living circle, dominated by motorized travel, represents the top tier of public service configuration. (2) Quantitatively, the delineation identified 2753 basic, 444 central, 19 township, and 1 county-level living circles in the Anding District of Dingxi City. The Northern, Eastern, and Southwest Zones suffer from fragmented mountainous landscapes, limiting mobility and accessibility. The Central Zone, however, benefits from a combination of mountainous terrain and river valley plains, offering superior service accessibility. (3) The analysis results based on the MCR model and gravity model aligned more closely with reality, reflecting the scale patterns of rural community living circles. The results of this study can provide theoretical guidance for rural planning, construction, and management in the hilly and gully areas of the Loess Plateau.

1. Introduction

China is currently prioritizing rural development, integrating urban and rural areas, and enhancing the service levels of rural communities to create high-quality, harmonious villages. The promotion of rural development, construction, and governance is a pressing issue that requires exploration in the context of rural revitalization [1]. The insufficient development of rural areas and the imbalance between urban and rural development represent significant societal contradictions in this new era [2]. Addressing these shortcomings and promoting rural revitalization are effective means of implementing national regional development strategies and achieving integrated urban-rural development. Rural communities serve as fundamental units for rural revitalization. Guided by the philosophy of new-era development, the rural community life circle is pivotal for promoting high-quality developments in China’s rural areas and achieving modernized governance objectives for rural communities [3,4].

Studies abroad have a longer history of exploring community life circles and offer a wealth of experience. Compared with domestic studies, foreign research demonstrates greater maturity in methods and model construction, increasingly focusing on micro-level analysis [5]. The scope and depth of the research are continually expanding [6]. Originating in Japan, the concept of the Living Circle is central to the Rural Living Environment Improvement Plan, which delineates the spatial distribution of daily activities within a specific village context. Defined by population benchmarks and distance circles, the living radius is hierarchically divided into the village–oaza–old village–town–local urban circle [7]. Since the introduction of the life circle concept in China, numerous scholars have actively explored various aspects, particularly focusing on measuring and delineating urban life circle boundaries, constructing living space systems, allocating public resources, and evaluating and spatially optimizing the built environment [8,9]. Therefore, the urban regional system and hierarchical structure of living circle planning are analyzed to promote the egalitarian provision of public services from the perspectives of residents’ personal lifestyles and spatiotemporal behavior [10]. Most research on the living circle of rural communities focuses on the equitable distribution of public service facilities and people’s travel patterns. The principal objective is to establish a hierarchical support system for rural community facilities synchronized with the administrative management system, promoting the convergence and integration with various village classification systems [11,12]. The Technical Guidelines for Community Life Circle Planning [13], an industry standard issued by the Ministry of Natural Resources of China in 2021, propose the rural community life circle as a fundamental spatial unit integrating the basic public service supply at the county and village levels. It establishes two levels of community life circles: townships and villages/groups, catering to various needs such as production, living, ecology, and governance. This rural community complex accommodates living, working, tourism, healthcare, and educational activities [14].

In summary, the traditional method of dividing rural life circles relies on factors such as travel distance, service radius, and isochronous circles. Although these approaches contribute to the theory of life circles, they are often limited by unsound division standards and difficulties in measuring spatial scope, particularly in areas with complex natural conditions [15]. As a result, there is often a gap between planning theory and practical applications. To refine the spatial structure of rural residents’ daily lives, it is necessary to delineate living spaces based on villagers’ actual experiences, moving beyond the traditional approach of using administrative boundaries to define life circles. Introducing the concept of life circles helps overcome travel resistance faced by rural residents [16], whose mobility is affected by the accessibility of public service facilities and travel barriers. This approach more accurately reflects the reality of rural living spaces and provides a foundation for improving village and town planning methods [17,18].

The Loess Plateau in Longzhong faces severe soil erosion, countless ravines, fragmented and complex topography, poor natural conditions, a fragile ecological environment, scattered settlements, and relatively inconvenient transportation, all of which severely restrict villagers’ livelihood and production activities. Therefore, optimizing rural living circles and improving supporting service facilities are crucial measures to address these challenges and promote rural revitalization [19,20,21]. Owing to the region’s unique topography, existing research struggles to fully analyze and optimize the spatial patterns of rural living circles in this area. To address this gap, this study used the Anding District of Dingxi City as a case study. Drawing on data from land use (such as distribution of settlements and supporting facilities), DEM, population density, and road networks, this study applied the MCR model [16], gravity model, and ArcGIS spatial analysis to examine rural community living circle patterns, focusing on the life circle structure in mountainous areas under both natural and artificial environmental constraints [22]. A hierarchical system of circles was constructed corresponding to the structure of natural village groups, central villages, townships, and county areas. This system included basic, central, township, and county-level life circles. Due to the multifaceted nature and numerous influencing factors within the complex field of landscape studies, this study prioritizes the physical aspects of the landscape to analyze the multi-scale spatial patterns of rural community living circles. This study focuses on the research question of how natural and artificial constraints shape the hierarchical structure of rural community living circles. It presents a methodological innovation by integrating the MCR and gravity models within complex rural terrain. The findings not only fill gaps in research on rural life circles but also offer valuable insights for optimizing the allocation of service facilities in rural communities [23,24].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

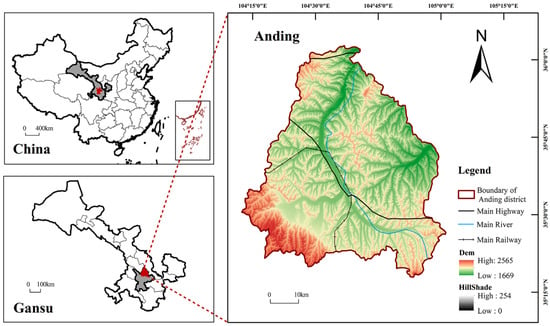

The Anding District, situated in the central part of Gansu Province, China, spans from 35°17′54″ N to 36°02′40″ N and from 104°12′48″ E to 105°01′06″ E. The total area of the district is 3638 km2, encompassing 12 towns, 7 townships, and 3 streets, with a total of 293 administrative villages. The area is divided into four regions: the northern district, which includes Bailu Township, Shixiawan Township, Lujiagou Town, and Gejiacha Town; the eastern district, comprising Xinji Township, Qinglanshan Township, Xigongyi Town, and Shiquan Township; the central region, which includes Chankou Town, Fengxiang Town, Lijiabao Town, Ningyuan Town, Xingyuan Township, and the streets of Futai Road, Zhonghua Road, and Yongding Road; and the southwestern region, which consists of Chenggouyi Town, Fujiachuan Town, Neiguanying Town, Gaofeng Township, Xiangquan Town, and Tuanjie Town. As of 2020, the district had a total population of 468,500, of which 361,800 were agricultural residents. Its gross domestic product amounts to CNY 11.476 billion, with the annual per capita disposable income for rural residents reaching CNY 9205 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overview map of the study area.

Overall, the distribution of public service facilities is uneven and incomplete. Most educational facilities are concentrated in urban areas and townships, comprising a total of 258 institutions, including 168 kindergartens, 49 primary schools (some of which are combined with kindergartens), 35 junior high schools, 6 high schools, and 1 higher education institution. Each township has one health center, and each administrative village has a clinic. Commercial services are largely concentrated in cities and towns, with rural areas, especially remote areas, facing a shortage of commercial facilities. Leisure facilities, such as green squares, are mainly found in urban areas and more economically developed towns, whereas remote towns lack adequate green spaces, basic sports, and leisure facilities. Religious facilities are relatively evenly distributed, mostly consisting of Taoist or Buddhist temples, aside from a few mosques.

The living circle generally aligns with administrative divisions consisting of county, township, and village group levels. Public service facilities are largely insufficient and unevenly distributed across most rural areas, with the exception of urban centers and towns, which have relatively better economic conditions.

2.2. Data Sources

Data on the current state of land use. Based on the 2019 basic surveying and mapping results (https://vgimap.tianditu.gov.cn/, accessed on 10 March 2023) released by the Ministry of Natural Resources, the land use data were visually interpreted by the authors’ team using remote sensing imagery and further supplemented and updated through field research.

DEM data of Anding District. In this study, elevation and slope data were extracted primarily from DEM data obtained from the Geospatial Data Cloud Platform (https://www.gscloud.cn/sources/accessdata/310?pid=302, accessed on 10 March 2023). Data with a resolution of 30 m met the precision requirements of this study.

Social and economic statistical data of Anding District were obtained from the Gansu Provincial Bureau of Statistics (https://tjj.gansu.gov.cn/tjj/c117468/202112/1925708.shtml, https://tjj.gansu.gov.cn/tjj/c117468/202501/174057311/files/fd0143b0dff14ffcb5278b373f8495a8.pdf, accessed on 10 March 2023). The socioeconomic indicators and related data utilized in this study were sourced from the China County-level Statistical Yearbook 2021 (County City Volume), China County-level Statistical Yearbook 2021 (Township Volume), and the 2020 Anding District Statistical Bulletin (https://data.cnki.net/yearBook/single?id=N2022040098&pinyinCode=YXSKU, accessed on 10 March 2023).

Population density data. The population data for 2010 and 2020 used in this study were obtained from the LANDSCAN Global Vital Statistics Dataset (http://landscan.ornl.gov/, accessed on 10 March 2023).

Road data used in this study were obtained from the Open Street Map (OSM, www.openstreetmap.org, accessed on 10 March 2023). This study primarily focused on utilizing data on the current state of land use regarding road information to systematically review densely populated village-level roads, supplement missing routes, and eliminate agricultural pathways unrelated to the living environment. Based on available land-use planning and related data for the Anding District of Dingxi City, the planned roads within the district were further enhanced and refined.

2.3. Methodology

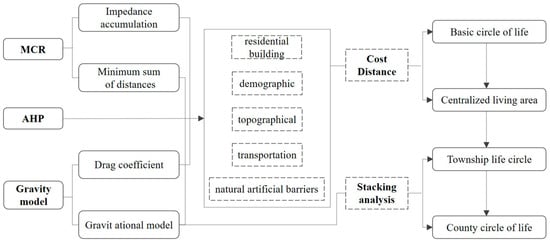

To thoroughly examine the structure of rural community living circles, the minimum cumulative resistance (MCR) model, commonly used in ecological pattern research, was applied to construct a resistance surface model. This model was based on public service centers and the residential areas they serve to simulate the spatial diffusion between points. The suitability of the living space was evaluated by considering multiple factors, including terrain, transportation, and human settlements. A multi-factor weighted overlay analysis of various environmental elements was performed, and the spatial influence range was determined using the gravity model. This analysis reveals the fundamental characteristics of rural community life circles. Impedance accumulation and resistance coefficients were used to assess the basic and central living circles, and the minimum distance sum and gravity model were applied to evaluate town and county living circles, highlighting a multi-scale spatial system of rural living circles.

2.3.1. MCR Model

The MCR model was first introduced by Knaapen in 1992. Since its inception, this model has been widely applied in studies of natural ecology and human processes. Through numerous applications, the MCR model has demonstrated its adaptability and versatility in analyzing various processes concerning horizontal spatial expansion [25]. The formula for this model is as follows:

where refers to the minimum cumulative resistance value, denotes the spatial distance from a resident’s origin point (in this study, the origin point is the service center) to the origin point represents the resistance coefficient of the grid to the resident’s behavior, represents the cumulative sum of distance and resistance traversed through all units between grid and origin , and denotes the positive correlation between the minimum cumulative resistance and the resident’s behavior. This study primarily utilized the MCR model to accumulate the impedance at the elemental level. The analysis was conducted using the ArcGIS 10.8 software platform, thereby delineating the small-scale basic living circle and central living circle.

To construct larger-scale town-based and county-based living zones, the distance sum minimization model from the MCR model was utilized. This model was implemented to select spatial locations for facilities based on a predetermined number, minimizing the sum of travel costs for all users to reach their nearest facility. Its practical significance lies in achieving a minimum total travel cost.

The model primarily utilized the Network Analyst—Location Allocation feature in the ArcGIS 10.8 software platform for analyses. It operated based on the following principle, where given a set of requirements and the spatial distribution of existing facilities, the system selected a specified number of facility locations from user-designated candidate sites. The selection criteria were based on a specific optimization model, aiming to achieve preset objectives such as optimal facility accessibility, maximum facility utilization efficiency, or the broadest service range of the facilities. The calculation involved determining the sum of the shortest travel costs from the central living circle to the town-level service center, with both the facility service center in the central living circle and the town-level facility service center considered as points of service.

2.3.2. Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP)

The MCR model analyzes the suitability of travel within the living spaces. It establishes a resistance system from three criteria layers (topographical, transportation, and residential) and seven element layers. Suitability indicators for travel within living spaces were evaluated primarily using ArcGIS 10.8, a software platform for data extraction and analysis. The data underwent range normalization to standardize the indicator dimensions, and the weight of each index (Wi) was determined using AHP (Table 1).

Table 1.

Travel suitability assessment and weight information of living space.

The AHP is a decision-making method that divides decision-making elements into objectives, criteria, and schemes. This method is well suited for systems with hierarchical and interconnected evaluation criteria, particularly in decision-making scenarios where quantifying target values is challenging [26]. This involves the construction of a judgment matrix and the determination of its maximum eigenvalue. The corresponding eigenvector W, once normalized, represents the relative importance of a particular level index to a related index at the subsequent level.

2.3.3. Gravity Model

- Resistance Coefficient

In the Longzhong Loess Plateau region, where villages are dispersed and transportation is challenging, a resistance coefficient f was introduced. This coefficient quantifies the difficulty of villagers’ travel in mountainous terrain by comparing travel times between plains and hilly areas [27]. The equation used is as follows:

where represent the sample number, represents the time required to travel 5 km in a plain area, denotes the time required to travel 5 km in a loess hilly and gully area, and f denotes the drag coefficient for different travel modes.

Sample selection balanced representativeness and accessibility. Ten effective villages were selected in hilly areas (covering different slopes and traffic types), while six control villages with comparable conditions were chosen in plain areas to isolate the impact of terrain on travel time. Data was collected using a combined method of field monitoring and questionnaires. Taking 5 km as the standard distance, travel times were recorded and cross-referenced with supplementary information from 109 valid questionnaires. The comprehensive mean value was calculated and adopted as the resistance coefficient . Limitations of this study include: the samples do not cover all geomorphic subtypes; the data does not account for seasonal dynamic factors; the influence of individual characteristics and specific traffic details was simplified; and the validation method lacks horizontal and vertical comparisons. Future research should aim to further optimize these aspects.

- 2.

- Gravity Model

The gravity model, a physical model, assesses the interaction between points and network connections among administrative regions [28]. In this study, the Euclidean distance and existing road distance served as the basis, with the drag coefficient enhancing the gravity model to calculate the relationships between administrative regions. The equation used is as follows:

where and represent the total population, represents the actual road length, and denotes the resistance coefficient. This study primarily focused on town and county life circles.

2.4. Technological Course

2.4.1. Source Identification

The original definition of source was proposed by Dutch ecologist Knaappen in the MCR model, serving as the starting point and foundation for the outward diffusion of phenomena and entities. It can either expand or attract and is commonly used to evaluate the suitability of landscape ecological security patterns [29]. In this study, the concept of source was introduced into the analysis of rural community life circle patterns. Traditionally, the MCR model overlooks the gradation of a source. However, owing to variations in location, economic and social development level, allocation scale, and influence scope among identical sources, there were significant differences in the aggregation and diffusion capacities of public service centers at different levels. Consequently, based on the scale disparity between public facilities in urban and rural areas, public service centers within the life circle were categorized into distinct levels.

Based on research findings from the Overall Territorial and Spatial Planning of Anding District (2021–2035) (Natural Resources Bureau, Anding District, Dingxi City, 2023), the Anding District is mandated to establish a comprehensive public service infrastructure system. This system, which emphasizes educational, health, sports, and social welfare facilities, comprises two main components, urban areas and villages, each delineated into five tiers. Urban public service infrastructure is structured across four tiers, focusing on central towns, secondary central towns, key townships, and general townships. Conversely, village-level public service facilities are categorized into three tiers: central, grassroots, and general villages. Aligning with the current state of public service infrastructure development and the hierarchical structure of rural community life circles, the urban and village systems of Anding District, along with their public service centers, are delineated into four tiers. The first tier comprises the central urban area of Anding District, characterized by robust agglomeration and diffusion functions aligned with the county-level life circle. The second tier encompasses the townships within the Anding District, pivotal in supporting both the production and daily activities of villagers, exhibiting a certain level of attraction and influence corresponding to the town-level life circle. The third tier comprises community service centers within administrative villages, integral to providing daily life services to villagers, corresponding to the central life circle. Finally, the fourth tier consists of supporting facilities for natural villages, closely intertwined with villagers’ daily routines, and aligning with the basic life circle.

2.4.2. Suitability of Living Space for Travel

According to the analytic hierarchy process, yaahp (v11.3) software was used to calculate the weight of each factor, and the specific results are shown in Table 1.

Weights in Table 1 were established via AHP and the Delphi method. Expert pairwise comparisons, tailored to rural travel in the Loess Plateau, informed a judgment matrix analyzed using yaahp software. “Yaahp” (Yet Another AHP Program) is a specialized software tool developed to support the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP). It is widely utilized for multi-criteria decision-making and weight calculation in fields such as urban-rural planning and human geography. Notably, yaahp supports group decision-making, making it well-suited for integration with the Delphi method. In this study, a total of 15 experts were invited to participate in the AHP pairwise comparison survey. The survey focused on the relative importance of the seven key factors listed in Table 1, which influence rural travel, while controlling for geographical characteristic variables. Using yaahp, the individual judgment matrices from different experts were aggregated to generate a comprehensive matrix via methods such as weighted averaging. This combined application of AHP and the Delphi method finalized the weight calculation scheme. Following consistency validation (CR < 0.1) and normalization, weights were derived. The results indicate Human Settlement Factors (0.5108) dominate, followed by Traffic Factors (0.2747) and Terrain Factors (0.2144). This aligns with local travel needs: settlement density drives agglomeration, traffic dictates efficiency, and terrain acts as a secondary constraint. Specifically, Residential Density (0.3445) and Slope (0.0998) are the most impactful variables, whereas Aspect (0.0221) has minimal influence due to its indirect relationship with mobility. Note that weights are independent of indicator polarity; the ‘positive/negative’ classification solely clarifies the correlation direction between variables and suitability.

2.4.3. Reclassification

Using the reclassification tool of ArcGIS 10.8, seven factors of raster data were reclassified and assigned (Table 2).

Table 2.

Factorial reclassification assignment table.

Combining the attribute characteristics of the factors with the actual conditions of the hilly and gully regions of the Loess Plateau, this study adopted differentiated methods to complete factor reclassification and assignment: Natural Geographic Factors (Elevation, Slope, Aspect, and Topographic Relief): The Jenks Natural Breaks method was employed for classification. Based on the statistical distribution characteristics of the data itself, this method divides values into classes with minimized within-class differences and maximized between-class differences, thereby accurately reflecting the spatial differentiation laws of terrain factors in the study area. The assignment was set according to the ‘degree of positive contribution to travel suitability’, where higher values indicate that the factor imposes fewer constraints on the travel suitability of living spaces at that level.

Human and Social Factors (Accessibility Analysis, Population Density, and Residential Density): Classification was performed by combining the empirical distribution of the study area with thresholds from relevant literature. Specifically, accessibility classification refers to the time cost thresholds of daily travel for rural residents on the Loess Plateau, while population density and residential density classifications draw on research findings regarding rural settlement space in the same region. The assignment follows the principle that ‘higher indicator values and stronger travel suitability correspond to higher assignments’, ensuring that the classified assignments align with actual travel demands.

2.4.4. Technical Route

The rural community life circle, centered around public service facilities to meet various needs, serves as the fundamental spatial unit for villagers. This also signifies the process of overcoming the transportation barriers. This study employed the MCR to simulate spatial diffusion between points and conducted a multi-factor weighted superimposition analysis on various environmental factors. Additionally, it integrated the gravitational model to measure the scope of the life circle, showcasing the multi-scale spatial characteristics of the rural life circle. The specific methods employed in this study are illustrated (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Sequenced methodology used in this study.

2.5. Basic Characteristics of Rural Life

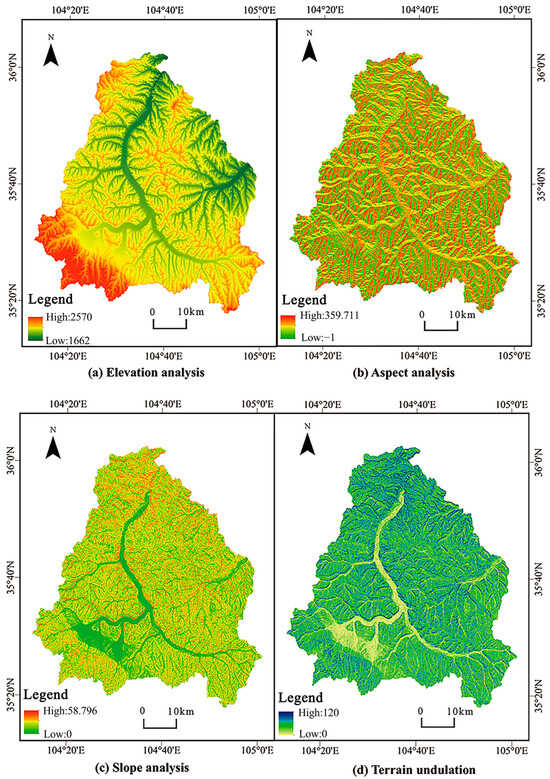

2.5.1. Topographical Factors

The DEM data underwent surface analysis in the ArcGIS 10.8 software platform, yielding elevation (Figure 3a), aspect (Figure 3b), and slope analysis (Figure 3c) of the stable area.

Figure 3.

Topographical factor analysis.

Utilizing the “Spatial Analyst-neighborhood analysis-focus statistics” tool in the ArcGIS 10.8 software platform, we extracted the maximum and minimum values of the DEM data. Subsequently, a Grid Calculator was employed to subtract the minimum from the maximum DEM values, yielding relief (Figure 3d).

2.5.2. Traffic Factors

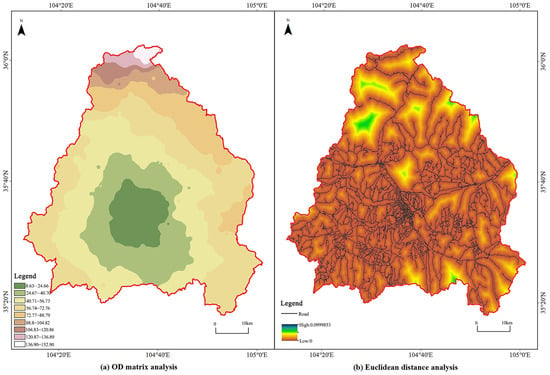

- Construction of Trip Path Network

The mobility patterns of villagers extend beyond roads designed for cars and designated public service locations to include extensive natural areas. Hence, this study considered various modes of transportation available to villagers, such as car travel, non-motorized travel, and walking. Consequently, the construction of a road network incorporated certain pathways suitable for both vehicles and pedestrians. The data primarily relied on road data, which served as the driving routes for villagers’ cars and non-motorized trips. The second approach relied on residential area distribution, linking residences to the nearest vehicular lanes as pedestrian routes for villagers. The spatial interpolation analysis calculates the time required to reach nearby public service nodes from the surrounding areas, thus enhancing the accuracy of the model in depicting villagers’ actual mobility spaces [30]. Using these combined pathways, ArcGIS 10.8, a software platform, was utilized to establish the rural road network in the Anding District, with time serving as the impedance measure.

The spatial structure of rural residents’ daily lives refers to the spatial layout of activity nodes (such as residences, farmland, and service facilities) and the connecting paths between them, reflecting the spatial patterns of residents’ daily production and living activities. In contrast, the pattern of rural community living circles refers to the hierarchical spatial scope formed by residents’ daily travel behaviors and service accessibility. The former determines the latter, while the living circle, in turn, constrains the optimization of the residents’ daily activity space. Beginning with the rural living circle concept, its delineation was grounded in residents’ residences and spans spatial areas shaped by daily activities such as commuting, shopping, leisure, and healthcare. This served as the foundational spatial unit for planning rural living circles. However, as the planning research did not focus on a single residential area for analytical convenience, this study adopted the public service configuration point as the starting point. The villagers’ travel range, centered around the public service configuration point, served as the spatial reference for defining the scope of the rural living circle. In rural areas of our country, the development of public service facilities has historically followed an incremental approach, owing to the lack of unified planning. Typically, these facilities are centrally located within villages, emphasizing the convenience of transportation. Similarly, township-level facilities are concentrated around the location of the government. For analytical purposes, this study categorized public service facilities in towns and villages as public service configuration points, initially situated either at the government’s administrative unit or at the neighborhood committee within each village. These locations served as the basis for the OD matrix analysis, totaling 300 points (Figure 4a).

Figure 4.

Traffic factor analysis.

- 2.

- Travel speed index

In this study, we analyzed the time villagers need to reach public service facilities, considering intra-village trips using “walking & non-motorized transport” and inter-regional trips mainly relying on “motorized transport”. The transportation times for both modes are affected by topographical factors. The speed of motorized and non-motorized transport depends on different road classifications and topographical features [31]. When assessing walking speed, certain factors, such as topographical wear and tear and the conversion between straight-line and actual path distances, should be considered. Straight-line walking speed was calculated as follows:

where represents the walking linear speed (m/min), represents the walking path speed (m/min), and represents the ratio of the walking path distance to the straight-line distance. In this study, the walking speed in the gently sloping valley areas was set at 70 m/min, while in the steep slopes of the middle and low mountain regions, it was adjusted to 42 m/min owing to a 0.6 speed reduction factor. The correlation analysis yielded the K values of 1.66 for the gently sloping plain areas and 1.78 for the steep slopes of the middle-low mountain regions. Consequently, the linear walking speeds were calculated to be 42 and 24 m/min, respectively.

In the analysis of the villagers’ travel range, speed assignments were allocated to the road network model, considering the diverse modes of transportation employed by villagers [32]. For car travel, the speeds were adjusted according to terrain variations, whereas for walking and non-motorized transport, the speeds were similarly adjusted based on terrain conditions (Table 3).

Table 3.

Travel speed.

- 3.

- Euclidean Distance

The analysis of the OSM road data in the Anding District relied predominantly on the road data within the OSM dataset, utilizing the distance analysis tools available in the ArcGIS 10.8 software platform (Figure 4b).

2.5.3. Demographic Factors

- Population Density

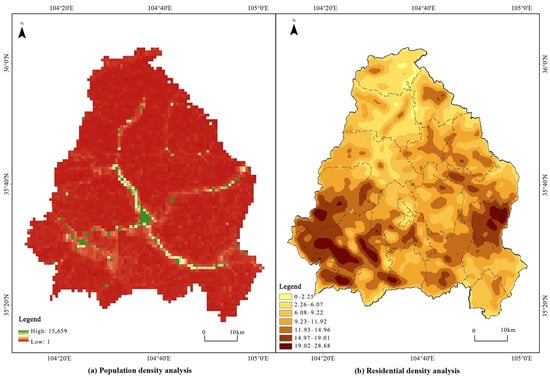

The population data adopted in this study, obtained from the LandScan Global Population Dynamics Dataset available at http://landscan.ornl.gov/ (accessed on 10 March 2023), underwent processing within the ArcGIS 10.8 software platform (Figure 5a).

Figure 5.

Demographic factor analysis.

- 2.

- Residential density

The rural homestead plots in the Anding District were isolated and analyzed using density analysis tools in the ArcGIS 10.8 software platform. This process generated a map illustrating residential density (Figure 5b).

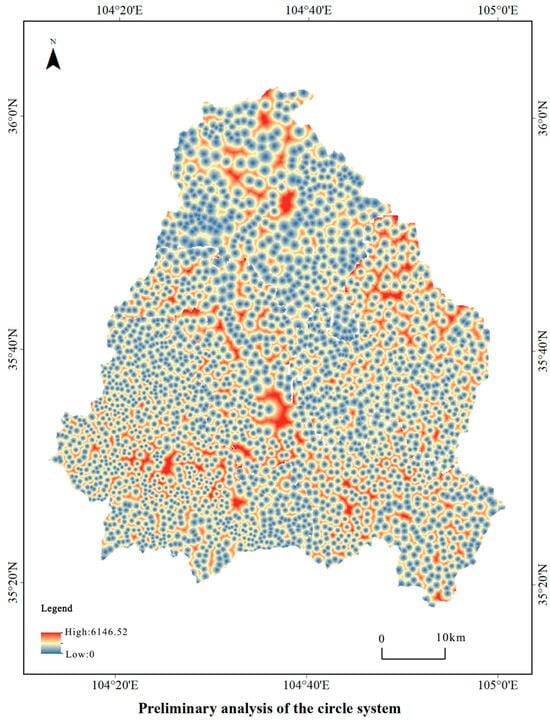

2.5.4. Grid Calculator and Cost Distance

Using the raster calculator in the ArcGIS 10.8 software platform, various factors and their respective weights were calculated to produce an overlay product. This product underwent a cost–distance analysis, yielding the initial results of the circle layer system (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Preliminary outcomes of the circle layer system.

2.5.5. Natural and Artificial Barriers

Anding District, situated in the rugged terrain of the Longzhong Loess Plateau, faces challenging natural conditions that affect the delineation of residential areas. To address this, natural features such as cliffs, dry gullies, and rivers were identified as boundaries for living spaces. Dingxi City serves as a crucial transportation hub in Western China. Anding District exhibited numerous railways and highways, significantly influencing residents’ travel patterns and defining basic and central living areas [33]. Based on relevant theoretical insights, this study analyzed buffer zones around natural barriers, such as rivers, railways, and highways, to enhance and optimize the residential area system. Setbacks of 30 m were designated for the areas adjacent to railways and highways, while 50 m setbacks were applied to riverine areas. No specific stipulations were defined for mountain ridges, given their intricate nature.

3. Results

3.1. Multi-Scale Spatial Characteristics of Rural Life Circle

The extent of the rural living circle depends on the positioning of public service configuration points and road transportation networks [34]. The former establishes the origin of the rural living circle, whereas the latter dictates the coverage size. According to the central place model, service areas of higher-level central places include those of lower-level central places. Similarly, the rural living circle at a higher level encompasses that at a lower level [20]. Moreover, higher-level central places typically offer services that cover those provided by lower-level ones (a central town serves a general town, and a central village serves a grassroots village). Therefore, when creating rural living circles at lower levels in this study, the selected public service configuration points comprised those at the respective level as well as higher levels.

3.1.1. Basic Life Cycle Characteristics

The basic living circle delineates the area in which villagers primarily engage in activities around key public service points, typically at the level of natural village groups [35]. Utilizing the previously discussed MCR model, this study initially established a 15 min travel radius around these pivotal public service points as the boundary of the basic living circle, restricted to walking and non-motorized transport. Based on this boundary, this study evaluated the accessibility between residential zones and nearby public service points. Residential areas lacking adequate services are either equipped with essential infrastructure or relocated to designated zones to ensure a balanced distribution of rural amenities [19].

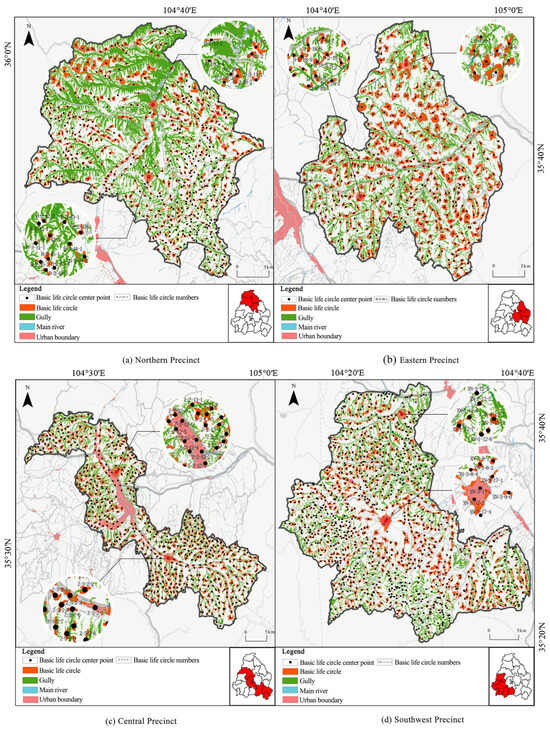

However, the Anding district is situated in the Longzhong Loess Plateau and is characterized by complex topography (Rivers Crisscross). There are railways, expressways, and other major infrastructures across the county. Consequently, when delineating the basic life circle, it should be segmented according to these inherent factors. Therefore, the basic life circle is not uniformly distributed but is dispersed with varying sizes within the stable regions. The entire area is organized according to mountain ridges, resulting in numerous basic life circles across the county. In this study, the basic living circles were delineated according to the four districts (Figure 7a–d).

Figure 7.

Basic life circles.

There were 600 basic living units in the north, 424 in the east, 616 in the central region, and 1113 in the southwest, totaling to 2753 designated basic living units. From the perspective of quantitative characteristics and spatial differentiation mechanisms, significant differences in fragmentation and scale are observed across the various zones: The Northern Zone exhibits high topographic relief but low population density. It features the largest average basic living circle area (20.07 hm2) and the highest fragmentation index. Consequently, the average travel time across living circles reaches 26.3 min. The Eastern Zone has a high river network density, where water systems exert a significant segmentation effect. The average living circle area is 35.76 hm2, with an average travel time of 21.5 min. The Central Zone demonstrates high urban agglomeration, with contiguous built-up areas of sub-districts and towns and well-developed infrastructure. It possesses the smallest average living circle area (39.78 hm2) and the lowest fragmentation index. Residents here enjoy the best service accessibility, with an average travel time of 12.8 min, although the areas adjacent to railways and highways experience intense segmentation. The Southwest Zone contains numerous towns and scattered settlements, resulting in the highest number of living circles. However, due to relatively moderate topographic constraints, the average area is 15.86 hm2, with an average travel time of 18.7 min. The high fragmentation in the Northern, Eastern, and Southwest zones directly leads to low coverage efficiency of public service facilities. In contrast, the low fragmentation pattern in the Central Zone supports the centralized layout of community service facilities. These characteristics indicate that restrictive factors such as terrain and infrastructure not only shape the spatial pattern of living circles but also directly impact the efficiency with which rural residents access services.

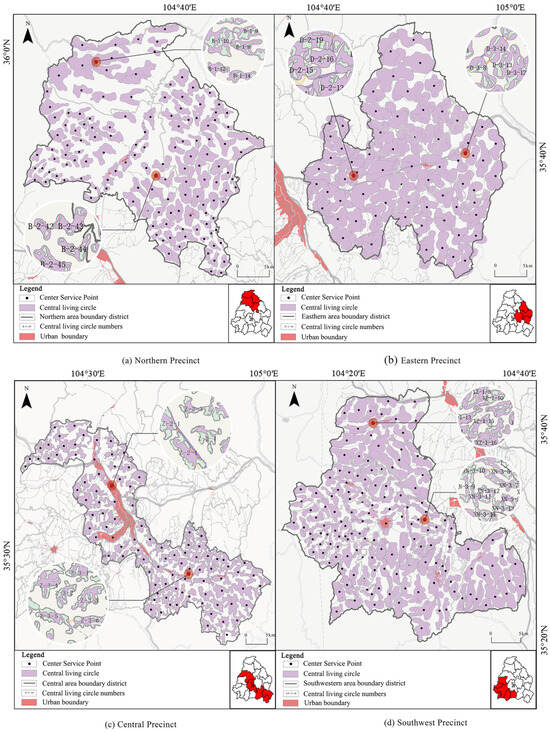

3.1.2. Characteristics of the Central Living Circle

The scope of the central living circle comprises the aggregation of basic living circles centered around the central configuration points and service targets. Administrative village-level public service configuration points were selected as district-wide points and redefined as central public service configuration points in this study. Utilizing nearest facility point analysis, we identified commuting living circle service targets, ensuring that the travel time from basic public service configuration points to central ones was within 20 min, with the mode of travel being motor vehicles. We further optimized the locations of the basic public service configuration points that did not meet these criteria. Finally, the basic living circle centered on both the central public service configuration points and the basic public service configuration points merged to constitute the central living circle. The travel time from the residential point to the basic public service configuration point was within 15 min [7]. Similarly, from the basic public service configuration point to the commuting public service configuration point, it was within 20 min, which ensured that all residents within the central living circle could travel from their residential point to the central public service configuration point within a maximum of 35 min. In the northern section, 136 central living circles were designated. In the eastern section, 66 were identified, 99 in the central section, and 143 in the southwestern section. In total, 444 central living circles were identified across all sections (Figure 8a–d).

Figure 8.

Central living circles.

From the perspective of core quantitative characteristics, the Central Zone exhibits the smallest average central living circle area (5.68 km2), and the highest average population served (1394 persons/circle). Leveraging the advantages of contiguous urban agglomeration and a dense road network, the average travel time for residents to reach central public service points is only 19.7 min. Although the Southwest Zone contains the highest number of living circles, due to moderate topographic constraints and a relatively complete road network, it has an average area of 4.04 km2, an average population of 948 persons/circle, and an average travel time of 24.5 min. Influenced by high topographic relief and low population density (67 persons/km2), the Northern Zone displays an average area of 2.83 km2 and an average population of only 405 persons/circle. Complex terrain results in poor road conditions, leading to the longest average travel time across all zones at 32.6 min. Affected by the segmentation effect of water systems, road connectivity in the Eastern Zone is weakened, resulting in an average area of 8.42 km2, an average population of 1183 persons/circle, and an average travel time of 27.9 min, which is slightly lower than that of the Northern Zone. The degree of fragmentation of central living circles exhibits a significant negative correlation with service accessibility. Natural factors such as terrain and water systems, along with village scale, dispersion, and infrastructure levels, collectively shape the quantity and scale patterns of central living circles across zones and directly determine the coverage efficiency of public service resources and the convenience of service acquisition for residents.

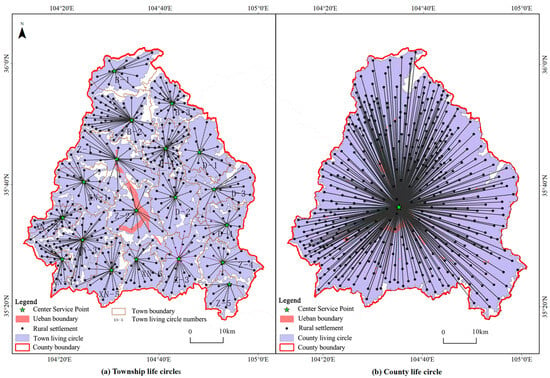

3.1.3. Characteristics of the Town Life Circle

The scope of the town-based living circle encompasses the cumulative central living circles centered around the service facilities and targets within the town-based service area. This study utilized the town areas delineated by the urban development boundaries of 19 townships within the Anding District as township-level public service configuration points. Employing the sum of the minimal distance model and gravity model from the MCR model for overlay, the merging of central living circles around service facilities and targets generated 19 town-based living circles (Figure 9a). With a service radius of approximately 10 km, the transportation within this circle combined motor and non-motorized vehicles, ensuring that residents could access the service core within 60 min. This level of public service facility configuration represented the highest standard at the town-based level, serving as a comprehensive service center for cultural, office, commercial, and other town aspects. It addressed the multifaceted needs of residents regarding education, medical care, elderly care, cultural activities, shopping, and entertainment [36].

Figure 9.

Town-based and county-level living circles.

3.1.4. Characteristics of the County Life Circle

The county-level living circle encompassed the territory of 19 town-level living circles within the Anding District. This study focused on the urban area of Anding District, defined by its urban development boundaries, as the deployment point for county-level public service configurations. Utilizing the minimum distance summation model within the MCR framework and gravitational model, we integrated town-level living circles centered around county-level service facilities and their targets, resulting in the creation of a county-level living circle (as shown in Figure 9b). With the urban area as its core, the surrounding suburban villages collectively constituted a service core that provided services to residents across the entire region. Motor vehicles were the primary mode of transportation within this service radius. This level of public service infrastructure represented the most advanced standard at the county level, functioning as a comprehensive center for culture, offices, commerce, and related services within the county. It addressed the diverse needs of county residents, including education and training, healthcare and elderly care, cultural and leisure activities, shopping, and entertainment.

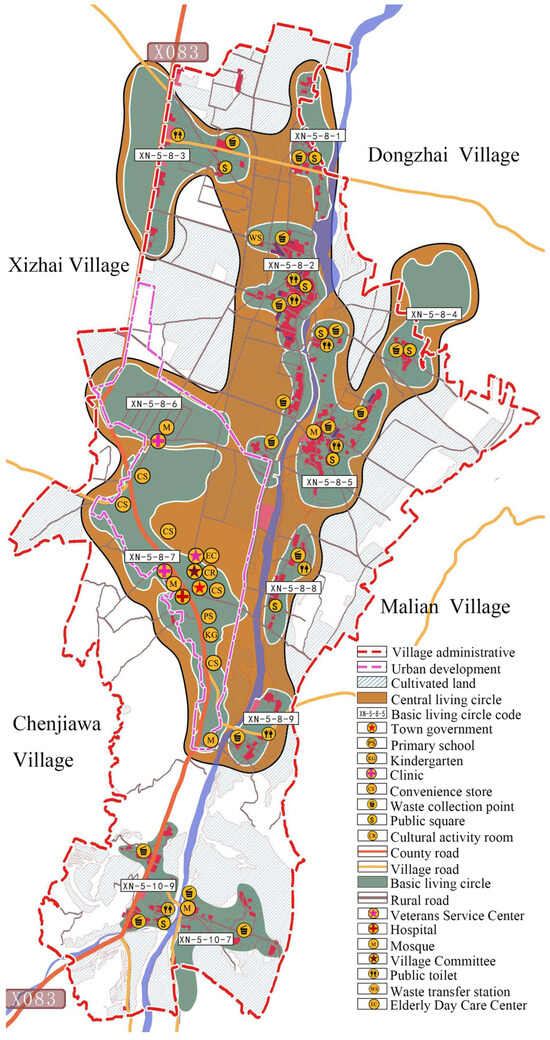

3.2. Case Study

This study selected Xiangquan Village, located in Xiangquan Town, Anding District, as a representative case for empirical analysis. This study focuses on delineating the basic and central living circles within the region encompassing Xiangquan Village and optimizing the allocation of public service facilities at various levels. Xiangquan Village is situated on the ridge-and-gully loess plateau terrain of the Loess Highlands, characterized by a topography that slopes from east to west and south to north, forming a narrow, elongated shape. The village experiences a mid-temperate semi-arid climate. Located in the southwestern part of the Anding District, Dingxi City, Xiangquan Village also serves as the administrative center of Xiangquan Town. County Road 083 passes through the village, which is 24 km from downtown Dingxi. The village comprises 1018 households and a population of 3424, organized into nine villager groups. Shangdazhuang, Toupai, Xiadazhuang, Shijiazhuang, Xijie, Dongjie, and Nanjie are situated in the northern river valley terrain, whereas Shapo and Liangshan are located in the southern mountainous areas.

The village was divided into 11 basic living circles. Nine of these (labeled XN-5-8-1 to XN-5-8-9) collectively formed the XN-5-8 Central Living Circle (Figure 10). The two basic living circles in the southern part of the village belong to the XN-5-10 Central Living Circle. To facilitate high-quality local development and living standards, this study optimizes public service allocation by integrating existing infrastructure with the quantitative analysis of living circle patterns. The strategy prioritizes infrastructure upgrades to enhance overall accessibility. Specifically, for the Southwest Zone—characterized by scattered settlements—the plan focuses on optimizing the reach of central points. This involves reinforcing the XN-5-8 central living circle with elderly care and agricultural hubs to serve 9 neighboring circles, and extending services to 2 southern circles within XN-5-10 via new public activity spaces. This configuration is expected to reduce the average resident travel time from 32 min to below 28 min. Consequently, it improves service coverage, mitigates spatial fragmentation, and elevates the utilization efficiency of public resources (Table 4).

Figure 10.

Division of living circles and public service facilities planning in Xiangquan Village, Xiangquan Town. Note: XN-5-8-1 in the figure represents the basic living circle number, where “XN” indicates the Southwest Area, “XN-5” represents the township-level living circle number, and “XN-5-8” represents the central living circle number.

Table 4.

Allocation of Public Service Facilities in Xiangquan Village, Xiangquan Town.

4. Discussion

The resistance surface generated by the MCR model comprehensively captured the pattern characteristics of basic and central living circles in the rural communities of the hilly and gully regions of the Longzhong Loess Plateau. Constructed through multi-index and multi-dimensional analyses of natural conditions and socio-economic factors, this model ensured the clarity of the spatial pattern structure of community living circles while considering their basic characteristics and layout guidelines. Consequently, the analysis results accurately reflected the requirements for travel suitability within rural living spaces. In examining the multi-scale pattern characteristics of rural living circles, the basic living circle reflects the pattern characteristics of natural villages or villager groups, corresponding to the “multiple points, scattered, and micro-intervention” features of configuration settings [37]. Conversely, the central living circle reflects the pattern characteristics of administrative villages and addresses the demand for convenient service facilities. The pattern characteristics of the town-level living circle depict the distribution characteristics of townships or market towns, fulfilling the essential material and cultural needs of the villagers. Similarly, the county-level living circle can address the material and cultural requirements of villagers. Hence, the multi-scale rural living circle pattern aligned better with actual needs and reflected policy regulation directions [38,39]. However, rural living circles can be affected by diverse factors, including nature, ecology, society, economy, and policy, making the measurement of their scope challenging. To accurately define rural living circle boundaries, the MCR was integrated with the gravity model, considering the process of overcoming travel resistance within living circles. Villages’ living spaces ideally occupy areas with minimal resistance tailored to the configuration points of public service facilities at various levels [39]. Regarding its practical significance, this case offers policy implications for future rural development in the Anding District of Dingxi City. We leveraged comprehensive spatial coordination planning and resource policy allocation to address the primary deficiencies in spatial quality and community governance. This was facilitated by the application of tools such as “urban health checks” and other spatial informatization methods to “check the symptoms” of the community [40]. To equalize urban and rural public services, it comprehensively considers facility configuration, encompassing costs, management, rural resident lifestyles, and actual needs [41,42]. Emphasis was placed on enhancing the construction level and service provisions across educational, cultural, medical, elderly care, sports, leisure, and employment facilities [43].

Furthermore, the results of this study can serve as a key component in relevant specialized planning. This specialized planning is informed by the overall land and space planning for the Anding District in Dingxi City, which provides guidance and constraints. It is essential to systematically coordinate and comprehensively balance the spatial needs of specialized planning. This special plan refines and deepens the overall land and space plan, specifically focusing on living circles, and provides technical support for the implementation of a master land space plan. The Anding District of Dingxi City, capitalizing on rural revitalization opportunities, should embrace the concept of rural living circles and research results in its planning. It aims to optimize the contraction of rural community living circles within the broader county-level units of the Loess Plateau’s hilly and gully region, given the stabilized population dynamics in rural areas. This strategy aims to harmonize the socioeconomic functions of urban and rural areas, promoting the gradual establishment of a networked living space system that fulfills villagers’ needs for a compact, comprehensive, and accessible living environment [44]. The design of rural living circles and their supporting facilities should prioritize hierarchical intensification and differentiation, considering residents’ requirements and service efficiency. The supply model should exhibit flexibility and adaptability, with a focus on appropriately aggregating the supporting facilities. Through the integration of new technologies and innovative concepts alongside a blend of rigid and flexible control supply methods, the objective is not only to enhance supply efficiency but also to elevate service quality [45]. Moreover, the considerable disparities in living conditions, regions, and overall development across rural areas in our country present a diverse array of types and complex situations. This study explored the spatial pattern of rural community living circles within county-level units characterized by a standard level of development in the Loess Plateau’s hilly and gully regions. The patterns of rural community living circles in plains, developed areas, and rural regions surrounding major cities may exhibit variation, warranting further research based on relevant theories [46,47].

In summary, this study primarily examined the compositional elements of the rural physical space environment to delineate the rural community life circle. However, this study insufficiently considered the differences in social structures and relationships within traditional villages. Influenced by clans and acquaintance societies in the Loess Plateau region, residents’ facility choices often transcend spatial distance constraints. Furthermore, the study failed to distinguish between the needs of different groups, resulting in insufficient adaptability of the current delineation to diverse populations. The study also overlooked the impacts of population migration dynamics and spatial restructuring, leading to static conclusions. As rural areas face changes such as hollowing out and ecological migration, population mobility alters service demands, and policy-driven spatial restructuring disrupts original patterns. Since this study did not incorporate such dynamic scenarios, it has limited capacity to support long-term planning. In addition, the research lacks comprehensive attention to village functional transitions and facility operational statuses, resulting in poor adaptability. It did not consider the demand iterations brought about by rural industrial transformation, nor did it evaluate the impacts of facility idleness or functional displacement, limiting the practical guidance of the conclusions to current scenarios. Moreover, because the constraints of agricultural production radii were not included, and farmers’ production activities form a dual-service circle pattern, the existing delineation struggles to cover actual needs. Future research should integrate multi-dimensional factors and introduce dynamic simulations to construct a more adaptable delineation system, thereby enhancing the scientific rigor and practical utility of the study [48].

5. Conclusions

Utilizing the MCR model, gravitational model, AHP, and GIS spatial overlay analysis, we examined the current configuration points of public service facilities at various levels. This process integrated certain factors such as terrain, transportation, population, residential area, distance, natural obstacles, and artificial obstacles [49]. Through a multi-factor weighted overlay analysis and fine-tuning process, the basic characteristics of rural living circles were revealed. Subsequently, a multi-scale analysis of rural living circle features was conducted to construct a spatial system comprising basic, central, town-, and county-level living circles. This study makes three key scientific contributions. First, it transcends the limitations of single-dimensional physical space by developing a quantitative analysis framework of ‘Influencing Factors—Spatial Pattern—Facility Adaptation.’ This framework not only accurately maps the living circle patterns in the Anding District but also delivers a scalable tool for the quantitative delineation and simulation of rural living circles in the Loess Plateau region [50]. Second, the findings clarify the hierarchical matching between living circles and public service facilities, offering robust data support for optimizing facility allocation and meeting diverse needs. It also establishes a standardized paradigm for policy evaluation and planning [51], thereby enriching the theoretical landscape of rural settlement planning. Finally, acknowledging the study’s limitations, future research must integrate social, demographic, and industrial dynamics. By adopting dynamic simulation methods, the goal is to evolve the current static model into a dynamic coordination system. This advancement will provide critical theoretical and technical support for rural revitalization in the Loess Plateau, facilitating the creation of a rural community model that harmonizes spatial logic with the practical needs of livelihoods [52].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, J.J., Z.C. and L.Y.; formal analysis, writing—review and editing, Z.C. and J.J.; validation, L.Y.; funding acquisition, J.J. and T.W.; investigation, J.J., L.Y., Z.C. and S.D.; resources, J.J. and T.W.; data curation, Z.C. and L.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, J.J. and Z.C.; visualization, supervision, project administration, J.J., L.Y., Z.C. and S.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Gansu Province Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 22JR5RA339] and Gansu Province Science Foundation for Youth [grant number 22JR5RA367]. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or manuscript preparation.

Data Availability Statement

The data availability statement of each database are as follows. First of all, Data on the current state of land use was obtained from the 2019 basic surveying and mapping results are available in the (https://vgimap.tianditu.gov.cn/, accessed on 10 March 2023) repository. Then, elevation and slope data were extracted primarily from DEM data are available in the (https://www.gscloud.cn/sources/accessdata/310?pid=302, accessed on 10 March 2023) repository. Third, Social and economic statistical data of Anding District are available in the (https://tjj.gansu.gov.cn/tjj/c117468/202112/1925708.shtml (accessed on 10 March 2023), https://tjj.gansu.gov.cn/tjj/c117468/202501/174057311/files/fd0143b0dff14ffcb5278b373f8495a8.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2023)) repository. Fourth, The socioeconomic indicators and related data utilized in this study were sourced from the China County-level Statistical Yearbook 2021 (County City Volume), China County-level Statistical Yearbook 2021 (Township Volume), and the 2020 Anding District Statistical Bulletin, which are available in the (https://data.cnki.net/yearBook/single?id=N2022040098&pinyinCode=YXSKU, accessed on 10 March 2023) repository. Fifth, population data for 2010 and 2020 are available in the (http://landscan.ornl.gov/, accessed on 10 March 2023) repository. Finally, Road data are available in the Open Street Map (www.openstreetmap.org, accessed on 10 March 2023). The above is a link to download the raw data from this study, if anyone wants to request data from this study, they can register directly from the above website and download it for free.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Georgios, C.; Barraí, H. Social innovation in rural governance: A comparative case study across the marginalised rural EU. J. Rural. Stud. 2023, 99, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Liu, S.; Fang, F.; Che, X.; Chen, M. Evaluation of urban-rural difference and integration based on quality of life. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 54, 101877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Fei, X.; Chen, Q.; Hong, X.; Shen, G. Interplay of Industrial Transformation, Diversified Governance, and Talent Gathering on the Ruralization of China. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2025, 151, 04024055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Zhang, F.; Lun, F.; Gao, Y.; Ao, J.; Zhou, J. Research on a diagnostic system of rural vitalization based on development elements in China. Land Use Policy 2020, 92, 104421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Chi, G.; Wang, G.; Tang, S.; Li, Y.; Ju, C. Untangle the complex stakeholder relationships in rural settlement consolidation in China: A social network approach. Land 2020, 9, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarecor, K.E.; Peters, D.J.; Hamideh, S. Rural smart shrinkage and perceptions of quality of life in the American Midwest. In Handbook of Quality of Life and Sustainability; Martinez, J., Mikkelsen, C.A., Phillips, R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 395–415. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, J. Analysis and optimization of 15-minute community life circle based on supply and demand matching: A case study of Shanghai. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, E0256904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Wang, N.; Li, Y.; Sun, D.J. 15-min pedestrian distance life circle and sustainable community governance in Chinese metropolitan cities: A diagnosis. Hum. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Kong, X.; Liu, Y. Combining weighted daily life circles and land suitability for rural settlement reconstruction. Habitat Int. 2018, 76, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, P.; Wan, G.; Xu, L.; Park, H.; Xie, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yue, W.; Chen, J. Walkability in urban landscapes: A comparative study of four large cities in China. Landsc. Ecol. 2018, 33, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Lu, Y.; Lu, X.; Su, Q. Research on the village layout optimization in China’s developed areas based on daily life circles. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 15958–15972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Li, J.; Huang, J. Spatial–temporal patterns of population aging in Rural China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TD/T 1062-2021; Technical Guidelines for Community Life Circle Planning. Ministry of Natural Resources of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2021.

- Chen, C.; Woods, M.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Gao, J. Globalization, state intervention, local action and rural locality reconstitution-a case study from rural China. Habitat Int. 2019, 93, 102052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Huang, X.; Wu, D.; Yang, H. Construction of ecological security pattern adapting to future land use change in Pearl River Delta, China. Appl. Geogr. 2023, 154, 102946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Liu, Y.; Luo, X. Integrating the MCR and DOI models to construct an ecological security network for the urban agglomeration around Poyang Lake, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 754, 141868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, L.; Guo, Y. Land use change and its driving factors in the rural–urban fringe of Beijing: A Production–Living–Ecological perspective. Land 2022, 11, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaye, C.; McHugh, J.; Doolan-Noble, F.; Wood, L.C. Rurality and latent precarity: Growing older in a small rural New Zealand town. J. Rural. Stud. 2023, 99, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Ma, L.; Tao, T.; Zhang, W. Do the supply of and demand for rural public service facilities match? Assessment based on the perspective of rural residents. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 82, 103905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, K.; Ma, C.; Sun, H.; Wang, Z.; Wu, H.; Li, M.; Zhang, L.; Tang, X.; et al. Healthy community-life circle planning combining objective measurement and subjective evaluation: Theoretical and empirical research. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, A.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, L.; Liu, C.; Sun, P.; Liu, Q. A spatial equilibrium evaluation of primary education services based on living circle models: A case study within the city of Zhangjiakou, Hebei province, China. Land 2022, 11, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Wu, M.; Zhan, L.; Shang, R. Multifunctional evolution and allocation optimization of rural residential land in China. Land 2023, 12, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; He, J.; Liu, D.; Huang, J.; Yue, Q.; Li, Y. Urban green corridor construction considering daily life circles: A case study of Wuhan city, China. Ecol. Eng. 2022, 184, 106786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wen, C.; Lin, B. Research on the design and governance of new rural public environment based on regional culture. J. King Saud. Univ.-Sci. 2023, 35, 102425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaapen, H.; Scheffer, M.; Harms, B. Estimating habitat isolation in landscape planning. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1992, 23, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, M.S.; Effat, H.A. Geospatial modeling for a sustainable urban development zoning map using AHP in Ismailia Governorate, Egypt. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2021, 24, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahmasbi, B.; Mansourianfar, M.H.; Haghshenas, H.; Kim, I. Multimodal accessibility-based equity assessment of urban public facilities distribution. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 49, 101633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drezner, T.; Drezner, Z.; Zerom, D. An extension of the gravity model. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2022, 73, 2732–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Ma, L.; Che, X.; Dou, H. Simulation study of urban expansion under ecological constraint—Taking Yuzhong County, China as an example. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 57, 126933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolny, A.; Ogryzek, M.; Źróbek, R. Towards sustainable development and preventing exclusions—Determining road accessibility at the sub-regional and local level in rural areas of Poland. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truden, C.; Kollingbaum, M.J.; Reiter, C.; Schasché, S.E. A GIS-based analysis of reachability aspects in rural public transportation. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2022, 10, 1827–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Pan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tang, X.; Gao, B.; Gao, Y. Evaluation Method of Field Road Accessibility Based on GF-2 Satellite Imagines. In Proceedings of the 2018 7th International Conference on Agro-Geoinformatics (Agro-Geoinformatics), Hangzhou, China, 6–9 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Velaga, N.R.; Beecroft, M.; Nelson, J.D.; Corsar, D.; Edwards, P. Transport poverty meets the digital divide: Accessibility and connectivity in rural communities. J. Transp. Geogr. 2012, 21, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewell, S.J.; Desai, S.A.; Mutsaa, E.; Lottering, R.T. A comparative study of community perceptions regarding the role of roads as a poverty alleviation strategy in rural areas. J. Rural. Stud. 2019, 71, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Ju, S.; Wang, W.; Su, H.; Wang, L. Intergenerational and gender differences in satisfaction of farmers with rural public space: Insights from traditional village in Northwest China. Appl. Geogr. 2022, 146, 102770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Yuan, D.; Zhao, P.; Lyu, D.; Zhao, Z. The role of small towns in rural villagers’ use of public services in China: Evidence from a national-level survey. J. Rural. Stud. 2023, 100, 103011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Sima, L. Analysis of outdoor activity space-use preferences in rural communities: An example from Puxiu and Yuanyi village in Shanghai. Land 2022, 11, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Chen, J.; Liu, Z. Government responsiveness and public acceptance of big-data technology in urban governance: Evidence from China during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cities 2022, 122, 103536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamsuddin, S. Resilience resistance: The challenges and implications of urban resilience implementation. Cities 2020, 103, 102763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Yan, R.; Song, Y. Analysing the impact of smart city service quality on citizen engagement in a public emergency. Cities 2022, 120, 103439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinchak, N.P.; Browning, C.R.; Calder, C.A.; Boettner, B. Activity locations, residential segregation and the significance of residential neighbourhood boundary perceptions. Urban Stud. 2021, 58, 2758–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Gallent, N. Second homes, amenity-led change and consumption-driven rural restructuring: The case of Xingfu village, China. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 82, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamo, B.; Choi, J.; Choi, S.; Son, C. A review of trends and tasks of Korea’s rural life improvement programs: Lessons for Ethiopia. Lessons Ethiop. 2022, 29, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, K. Jane Jacobs and ‘the need for aged buildings’: Neighbourhood historical development pace and community social relations. Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 2407–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosworth, G.; Whalley, J.; Fuzi, A.; Merrell, I.; Chapman, P.; Russell, E. Rural co-working: New network spaces and new opportunities for a smart countryside. J. Rural. Stud. 2023, 97, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Lin, J.; Li, Y. Beyond government-led or community-based: Exploring the governance structure and operating models for reconstructing China’s hollowed villages. J. Rural. Stud. 2022, 93, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, R.; Rosenberg, M.; Yu, B.; Guo, X.; Wang, M. Accessibility of rural life space on the Jianghan Plain, China: The role of livelihood. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.J.; Alford-Teaster, J.; Schiffelbein, J.E.; Onega, T. Development of the rural perception scale (RPS-18). J. Rural. Health 2024, 40, 348–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.; London, J.K. Mapping in and out of “messes”: An adaptive, participatory, and transdisciplinary approach to assessing cumulative environmental justice impacts. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 154, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Yin, R.; Xia, T.; Zhao, B.; Qiu, B. People-oriented: A framework for evaluating the level of green space provision in the life circle from a supply and demand perspective: A case study of Gulou district, Nanjing, China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Qin, X.; Li, Y. Satisfaction evaluation of rural human settlements in northwest China: Method and application. Land 2021, 10, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, M. Commentary: Geographies of digital lives: Trajectories in the production of knowledge with user-generated content. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 142, 212–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.