Abstract

Understanding when and where to shift land from agriculture to forestry is essential for designing sustainable land use strategies that align with climate, biodiversity, and rural development goals. However, traditional profitability comparisons rely on long-term discounting, which is highly sensitive to assumptions and often misaligned with the shorter-term decision-making horizons that are relevant for policymakers. This study presents a deposit-based framework that interprets annual timber biomass growth as accumulating economic value, enabling direct, per-hectare comparisons with yearly agricultural profits. The framework integrates parcel-level spatial data, land quality indicators, national statistics, and expert inputs to produce high-resolution maps of annual profitability for both agriculture and forestry. Applied to the case of Latvia, the results show strong spatial variation in agricultural returns, particularly in low-quality areas where profits are marginal or negative. By contrast, forestry provides more stable, though modest, economic gains across a wide range of biophysical conditions. These insights help identify where afforestation becomes a financially viable land use alternative. The framework is designed to be transferable to other regions by substituting local data on land quality, prices and growth. It complements policy instruments such as performance-based CAP payments and afforestation support, offering a future-oriented tool for spatially explicit and economically grounded land use planning.

1. Introduction

Land is a limited resource that must serve multiple, often competing demands, including food production, timber supply, biodiversity conservation, and climate change mitigation. In recent decades, global population growth and rising incomes have increased demand for food, particularly animal-based products [1]. This trend has contributed to the large-scale conversion of forests into agricultural land [2,3], while urban expansion has further intensified pressure on natural land resources [4]. Even well-intentioned policies to reduce agricultural intensity can lead to unintended environmental impacts, such as indirect land use change and deforestation elsewhere [5].

In response, afforestation is gaining political momentum as a key element of climate and biodiversity strategies. The European Union (EU) has committed to ambitious afforestation targets in support of its climate neutrality and biodiversity restoration goals [6,7,8]. Countries such as Ireland and Spain have introduced national afforestation plans to expand forest cover, increase carbon sequestration, and improve ecosystem services [9,10]. Similar initiatives are also underway in Brazil and India [11,12].

Despite these efforts, afforestation policies are often met with hesitation from landowners, particularly in the agricultural sector. Concerns include the risk of higher land prices and food insecurity [13], potential restrictions on converting land back to farming [6], the long time periods before financial returns are received, and changes in soil properties that may reduce agricultural productivity [14,15,16].

Nevertheless, some researchers, such as Rämö et al. (2023), argue that transforming agricultural land that is both unused and low-yield into forests is essential for meeting ambitious climate targets [17]. Similarly, West et al. (2020) found that afforesting low-productivity grasslands can also be financially beneficial [18]. These findings support the broader view that land with limited agricultural potential, due to poor soil quality, low fertility, or other biophysical constraints, offers greater opportunity for land use change without significantly affecting food production.

At the same time, several experts suggest that innovations in agriculture, particularly precision farming, may help optimise land use efficiency [19,20,21]. By ensuring that high-yield crops are cultivated on the most suitable land, marginal or less productive areas could be freed up for afforestation [22]. Financial incentives and support for sustainable farming practices, combined with education and awareness programmes, can further encourage farmers to adopt such integrated approaches [23,24].

Financial considerations are central to land use decisions, especially where land is treated as an economic asset. Landowners generally seek to maximise returns, making the relative profitability of agriculture and forestry a key factor in decisions about land use change [25]. However, comparing these systems presents a significant methodological challenge: agriculture typically generates annual profits, whereas forestry provides returns only a few times over a rotation cycle that may span several decades.

To address this temporal mismatch, forest economics has traditionally relied on discounted cash flow methods [26,27,28]. The net present value (NPV) approach discounts future costs and revenues to a single present value, reflecting the time value of money over a forest rotation [29]. Building on this, the Equivalent Annual Value (EAV) converts NPV into an annualized figure, facilitating a direct comparison with the annual returns of competing sectors like agriculture [30]. Furthermore, the land expectation value (LEV), derived from the Faustmann formula, extends this analysis to an infinite series of rotations and remains the standard for estimating the economic value of bare forest land [31]. While these methods are theoretically robust, their practical application is constrained by a heavy reliance on long-term assumptions regarding future prices, costs, and discount rates. Small fluctuations in these parameters can yield disproportionately large variances in outcomes, often limiting the decision relevance of discounted cash flow methods for short–medium-term land management planning.

In this study, we present a parcel-level framework for comparing the annual profitability of agricultural and forestry land uses. This approach is designed to reduce reliance on long-term discounting methods, which can be difficult to interpret and highly sensitive to assumptions. Instead, we treat the annual growth of timber biomass as an accumulating economic value, enabling a more transparent and consistent comparison with agricultural profits. The framework integrates spatial data, land quality assessments, official statistics, and expert knowledge to calculate land profitability at a high resolution. We apply the method to a case study from Latvia, where afforestation is increasingly relevant in light of climate policy targets and structural challenges in agriculture. This framework supports regionally differentiated land use strategies by identifying where afforestation presents a financially viable alternative to agriculture. By enabling transparent, spatially explicit assessments of profitability, it contributes to the design of adaptive and multi-objective land management policies that align with economic viability, climate mitigation, biodiversity conservation, and rural development.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Region

The case region for this study is Latvia, a Northern European country located in the temperate cool moist climate zone (Figure 1). Approximately 50% of Latvia’s territory is forested, while about one-third is designated as agricultural land. Latvia is sparsely populated, with a population density of 30 persons per square kilometre as a country average, and 10 persons per square kilometre for rural areas [32].

Figure 1.

Location of the study area.

Agricultural land in Latvia is almost entirely privately owned and managed by individual farmers or enterprises. As of the end of 2023, Latvia had 62,000 agricultural holdings, with large holdings managing half of the total agricultural land. In contrast, 46% of forest land is owned and managed by the state, while the remaining 54% is under the ownership of private individuals, municipalities, or other entities.

The agricultural sector in Latvia is primarily oriented towards cereal and milk production, positioning the country as a net exporter of these commodities. In total, the agricultural area covers approximately 1.97 million hectares, of which 1.36 million hectares are arable land. The average land area per agricultural holding is 45 hectares, with 31 hectares being agricultural land. Despite strong performance in certain sectors, domestic production of vegetables, fruits, and berries remains insufficient to meet national consumption needs. In 2023, the total agricultural output at current prices amounted to EUR 1.85 billion [32]. As a member of the European Union, Latvia operates under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), benefiting from financial support mechanisms similar to those available in other EU member states.

In Latvia, forests are a significant national resource, both economically and ecologically. Forest stands are predominantly composed of pine (25.6%), birch (27.2%), and spruce (19.6%), together accounting for 72.4% of the total forest area. Other notable species include grey alder (10.1%), aspen (8.2%), black alder (6.3%), ash and oak (1.0%), and a variety of other species (2.1%). In 2022, a total of 13.1 million cubic meters of wood were harvested in Latvia, with 6.4 million cubic meters sourced from state forests and 6.7 million cubic meters from forests owned by private entities. Forest restoration efforts covered an area of 41 thousand hectares [33].

2.2. Methodology Description

The methodology is structured as a comprehensive framework for calculating and comparing the annual profitability of agricultural and forest land uses at the parcel level. All calculations are conducted on a per-hectare basis to ensure consistency and comparability across land use types and regions. The analysis integrates spatial data with economic and biophysical indicators relevant to each sector.

For agriculture, average annual profitability (XA) is calculated for different crop groups and livestock specialisations using farm accountancy data, complemented by expert evaluations and calibrated against official statistics.

For forestry, a deposit-based approach is applied: potential profit (XF) associated with the average annual accumulation of timber biomass in forests eligible for harvesting is treated as a financial deposit. This value is calculated based on the net income potential of standing volume growth, incorporating current prices and species-specific yield assumptions. Total timber accumulation, accumulation of harvestable timber and financial parameters are calibrated against official statistics.

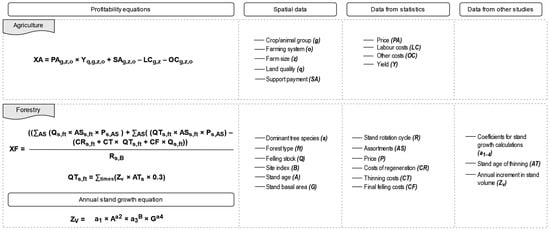

The methodology begins with the development of equations required to calculate annual profitability for both agricultural and forest land uses. These equations incorporate key variables such as yields, prices, production costs, and land characteristics. Once the equations are established, relevant input data are collected and processed, including spatial land parcel data, statistical records, and species-specific growth parameters. Parameter values are derived from national statistics, official registers, published research, and expert assessments. A schematic representation of the full methodology is provided in Figure 2, and each methodological component is explained in detail in the following subsections.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of key steps.

Detailed descriptive statistics on the Latvian agricultural and forestry sectors, as well as extended tables of parameter values, are provided in the Appendix A.1, Appendix A.2, Appendix A.3, Appendix A.4, Appendix A.5, Appendix A.6, Appendix A.7 and Appendix A.8. The main text reports only the information necessary to apply and interpret the framework, while all supporting details remain available for replication and adaptation in other regions.

2.2.1. Profitability in Agriculture

In this study, agricultural land profitability is defined as the net profit before taxes per hectare of land or per grazing animal. Profitability (XA) is calculated separately for each land use or production group (g), where g refers either to a crop group (profit per hectare) or a grazing animal group (profit per livestock unit). The crop groups include cereals, rapeseeds, pulses, potatoes, vegetables and berries (including strawberries and flowers), perennial crops, other crops (e.g., nectar plants, herbs, flaxseed, lavender, chamomile, caraway), fallow land, arable grassland, and permanent meadows and pastures. The grazing animal groups include dairy cows, suckler cows, and sheep. The poultry and pig sectors are excluded from the analysis as these animals are typically not directly linked to nearby land use.

To calculate agricultural profitability (XA), data from the Latvian Farm Accountancy Data Network (FADN) [34] and the Latvian Rural Advisory and Training Centre (LLKC) Gross Margin [35] are used in addition to expert evaluations. Anonymised FADN data at the individual farm level are used. The calculations are based on average parameter values from 2019 to 2024. Farms are classified into four groups based on the size of the managed area (z), as summarised in Appendix A.1, taking into account differences in productivity, costs, and revenues associated with farm size.

The prices (PA) for agricultural products are obtained from national statistics on the purchase prices of agricultural products for the period 2019 to 2024 [36]. Yields (Y) are calculated for each crop and farm size group from national statistics, with annual yields varying by crop type and farm size group [35,37]. In certain cases, yields are also influenced by land quality (q) and the farming system (o) employed (conventional or organic). Calculated profitability parameters per farm size (z) and farming system (o) are detailed in Appendix A.2.

In this study, land quality (q) is indexed from 5 to 85 points, with a weighted average of 36 points. Although the methodology for land quality indexing is developed over 40 years ago, it is based on a detailed and comprehensive evaluation framework that remains relevant for comparative analysis today. The index is originally designed to estimate the potential rye yield in kilograms per hectare, with one land quality point corresponding to 70 kg of rye per hectare [38]. Particular emphasis in the assessment methodology is given to soil related characteristics, including soil type, granulometric composition, and agrochemical properties. These are considered alongside a broader set of biophysical and site-specific variables, such as natural environmental conditions, moisture regime, drainage infrastructure, topography, parcel size and configuration, stoniness, microdepression occurrence, and the degree of land cultivation. Historical parcel-level land quality data, based on this methodology, cover a significant portion of agricultural land in Latvia [39], enabling spatially detailed assessments despite the historical origin of index. For parcels lacking historical data, land quality is estimated using the average of the nearest neighbouring parcels. While the index corresponds with rye yields, its linear structure allows it to remain useful for other crops as well, when combined with appropriate correction coefficients. These coefficients are calculated by dividing the average annual productivity of crop groups (cereals, rapeseeds, and pulses) from statistical data by the average land quality points and are refined or adjusted as necessary [40]. It is important to note that land quality is not a determining factor in all agricultural sectors. In this study, it is considered only in cases where its influence is clearly observable, most notably in crop production.

Almost every market-oriented farmer in Latvia submits spatial information about all fields and crops used for production to the Rural Support Service in order to apply for support payments (SA) within the EU Common Agricultural Policy. These payments are important as they stabilise farm income, support rural economies, protect natural resources, and help manage risks arising from fluctuating prices and unpredictable weather conditions [41]. Using this data (prepared by the Rural Support Service upon request) and overlaying it with the land quality index data layer, it is possible to calculate the indicative profitability of each field using the formula in Figure 2.

Additionally, all animal holdings are registered with the Agricultural Data Center, which provides information on the number of animals. By using this data along with the location coordinates of the holdings (prepared by the Agricultural Data Center upon request), it is possible to calculate the indicative profitability of each grazing animal holding.

Although the FADN dataset offers detailed information for approximately one thousand individual farms, there are notable limitations that complicate the accurate assessment of profitability indicators. A key issue is that many farm operators do not allocate themselves a formal wage. Instead, the value of their labour is covered by the remaining profit after expenses, which is often done to reduce taxable income. This practice can lead to an overstatement of reported profits, particularly on smaller farms with minimal or no hired labour. As a result, land use profitability may appear higher than it actually is, since the cost of the farmer’s own labour is not included. Additionally, the majority of farms in the dataset use mixed production systems, involving several outputs such as different crops or types of livestock. However, cost data are usually reported for the entire farm as a whole, without breaking them down by specific activity. This lack of detail makes it difficult to assess how profitable each type of production really is.

To address the first challenge, labour costs (LC) are adjusted by recalculating them using labour salary data from national statistics [42], rather than relying solely on bookkeeping records. This recalculation involves multiplying the sum of paid and unpaid labour inputs [43] by the agricultural labour salary. Since larger and technologically advanced farms typically employ more qualified labour, salary rates are adjusted based on farm size. In many instances, particularly for smaller farms, this recalculation of labour costs results in increased expenses and consequently reduces the profits indicated in the FADN data.

To address the second challenge, calculations are performed by selecting individual FADN farms with potentially narrow specialisations. However, notable differences in results between farms often persist. Therefore, corrections are made using LLKC Gross margin calculations. These calculations provide standard incomes and costs for different crop groups (cereals, rapeseeds, and pulses, potatoes, vegetables, strawberries, flowers, perennial crops, other crops, fallow land, grasslands in arable land, meadows and pastures), animals (dairy cows, suckler cows, sheep), farming systems (conventional and organic), and farm sizes (large, medium, small, micro).

The category of other costs (OC) encompasses various farm expenses that are essential for agricultural production and farm maintenance, such as fertilisers and plant protection products, animal feed, fuel, machinery and equipment maintenance, and services and equipment rental. One significant component of this category is depreciation, which increases with the capital intensity of a farm. Higher capital investment in machinery, equipment, and infrastructure leads to greater depreciation expenses. This trend reflects the economic burden associated with maintaining and replacing capital assets over time [34].

The results of our calculations are cross-validated against statistical data from the Eurostat [44], ensuring that our aggregated parcel-level estimates are consistent with national statistics. In the case of agriculture, both output prices and cost components were calibrated to match sectoral aggregates, enhancing the accuracy of profitability estimates at the parcel level.

2.2.2. Profitability in Forestry

Unlike agriculture, profit in forestry is typically generated only 2 to 3 times during a stand rotation cycle, which ranges from 30 to 100 years depending on the dominant tree species. This results in a situation where yearly profits in forestry are largely negative or close to zero, but significantly high during felling years. Consequently, direct comparisons of forestry profitability with agricultural production, which generates profit annually, are challenging.

To calculate forestry investment profitability, discounting methods are commonly used [45]. However, this approach relies on long-term assumptions about prices, inflation, and interest rates. Even minor changes, for instance, in interest rate assumptions over a 70-year period can substantially impact discounted values, making projection results highly sensitive to long-term assumptions. This results in a wide range of scenarios with significant differences between minimum and maximum outcomes [46]. Moreover, if forestry profitability results are to be compared with agricultural profitability, agricultural profits must also be calculated and discounted over the same long-term period, facing similar challenges of assumptions over an extended timeframe.

To address these challenges, in this study, forestry is instead conceptualised as an economic deposit, where annual increments in standing timber volume are treated as additions to a latent profit balance that materialises when the land or standing stock is sold. This perspective reframes forestry as generating an implicit yearly income stream, comparable in temporal resolution to agricultural profits, while avoiding long-term discounting of uncertain future flows.

For each forest stand, the annual deposited profit (XF) (EUR per hectare per year) is defined as the product of species- (s) and site-specific (ft) net income per hectare of forest stand (EUR per hectare per year) and the annual increment in standing volume (ZV) (m3 per hectare per year). Net income per hectare of forest stand is obtained as the difference between expected revenues from assortments (EUR per m3) and the full set of logging and regeneration costs at current prices. The cumulative deposit (EUR per hectare) at time is then the sum of annual deposited profits since stand establishment, representing the unrealised yet quantifiable economic value stored in the standing stock.

Due to the structure of the available data, we have initially calculated the cumulative deposit (EUR per hectare) of each dominant tree species and forest type at the end of the rotation cycle. Then, by dividing the cumulative deposit into years, corresponding to the length of the rotation cycle (R) of each dominant tree species (s), we have calculated the annual deposited profit (XF) (EUR per hectare per year). The length of the rotation cycle (R) for different dominant species is determined in Section 9 of the Law on Forests of the Republic of Latvia [47].

The expected revenues from assortments have been calculated based on the assumption that the proportion of assortments (AS) depends on the dominant species (s) and the forest type (ft) [48]. The proportion of assortments (AS) is multiplied by the price (P) for the respective assortment and the felling stock (Q) at the end of rotation cycle, obtaining revenues of final felling (EUR per ha). Revenues of thinning have been calculated by multiplying the proportion of assortments (AS) with the price (P) for respective assortments and the thinning stock (QT). The price of assortments (P) depends on the dominant tree species (s), and the assortment type (AS) [49]. The thinning stock (QT) has been calculated by multiplying the annual increment in standing volume (ZV) with the times and age of thinning (AT) (3 times at age 30, 46 and 60 for conifers and 2 times at age 20 and 40 for deciduous trees, for grey alder and aspen—1 thinning at age 20) and the coefficient 0.3 (assuming that 30% of the total stock is removed with thinning (for spruce the coefficient is 0.2)) [50]. Data for assortment proportion (AS) and prices (P) used in the calculations can be found in Appendix A.3.

The regeneration costs (CR) consist of the forestry measures after the final felling: soil preparation, purchase of planting material, planting, forest protection, agrotechnical maintenance, felling for maintenance of the composition and underbrush tending. The costs associated with soil preparation, planting material, planting, agro-technical practices, and young forest stand maintenance are derived from statistical data on forest regeneration and maintenance expenses for the period 2019–2024 [51]. The costs of young stand protection include labour compensation for this activity, reflecting the average service price for this activity over the period 2019–2024 [52], and EUR 36 for repellents [53]. Supplementation costs consist of seedling and planting expenses, adjusted by coefficients of 0.3 (assuming that, on average, 30% of the stand requires supplementation) and 0.5 (assuming that labour costs are by 50% lower). Underwood clearing costs are estimated based on industry practitioners’ evaluations [54]. The annual maintenance cost of land amelioration systems is estimated at EUR 23 per hectare, based on expert assessment. It is assumed that these systems require maintenance every five years. Accordingly, the total maintenance cost over a given rotation cycle is calculated as EUR 23 multiplied by the ratio of the rotation cycle (in years) to five. This provides a simplified estimate of cumulative maintenance expenditure per hectare over the rotation cycle. The regeneration costs (CRs) used in this study can be found in Appendix A.4.

The logging costs of rotation cycle consist of the expenses arising from the preparation and transportation of the assortments in thinning (CT) and final felling (CF). The logging costs per unit of harvested wood (EUR per m3) are derived from statistical data on average expenses of forest exploitation for the period 2019–2024 [55]. The costs of thinning (CT) (EUR per hectare) have been calculated by multiplying the costs of thinning per unit of harvested wood (EUR per m3) with the thinning stock (QT) per hectare (m3 per hectare) for each dominant tree species (s). The costs of final felling (EUR per hectare) have been calculated by multiplying the costs of final felling per unit of harvested wood (EUR per m3) with the total felling stock (Q) (m3 per hectare) at the end of rotation cycle for each dominant tree species. Logging costs are attached in Appendix A.5.

Calculations for the annual increment in stand volume (ZV) per hectare are based on equations that incorporate data about the main dominant species (s), site index (B), stand basal area (G), and age of the stand (A). Parcel-level data for the dominant species (s), site index (B), stand basal area (G), and age of the stand (A) are from State Register of Forests [56]. The coefficients (a1–4) used in the calculation of the stand growth are specified in Appendix A.6. Furthermore, to avoid extreme values, the calculated stand growth is aligned with the maximum standing volume per hectare from Donis (2019) which depends on the dominant species (s) and the site index (B) [57] (Appendix A.7).

To ensure the accuracy and reliability of our findings, forestry-related calculations are also cross-validated against statistical data from Eurostat [44]. Timber prices and forestry cost components were calibrated to align aggregated parcel-level estimates with national forestry statistics, thereby ensuring consistency with official statistical aggregates.

2.3. Sensitivity Analysis

To evaluate the robustness of the profitability results under different market conditions, a sensitivity analysis is conducted using observed price extremes from the 2019–2024 period. For agriculture, calculations are repeated using 2022 product prices, which were on average 22% higher than the baseline period and represent a favourable market condition. For forestry, 2020 timber prices, 15% lower than the baseline average, are used to reflect an unfavourable market scenario. All other parameters remained constant. This approach tests whether afforestation remains economically viable when agriculture is highly profitable and forestry returns are reduced. Price data for both sectors are obtained from the same sources as in the baseline estimates [35,36,49].

2.4. Mapping at Parcel Level

In this study, profitability calculations are conducted at the individual field level to account for the specific characteristics and management practices of each parcel. However, for spatial visualisation and data privacy purposes, the field-level results are aggregated into a uniform grid with cells of 100 hectares each. By standardising the data into regular 100-hectare grid cells, we enable a more consistent and comparable spatial representation of profitability across the case region, while preserving high spatial resolution. This method aligns with established practices in spatial land use analysis, where various aggregation techniques, such as the use of regular square grids, are used to harmonise heterogeneous data and support cross-regional comparisons [58]. Additionally, grid-based aggregation simplifies complex field geometries, improving the clarity and usability of spatial data for analysis and interpretation.

2.5. Technical Implementation

Profitability modelling and spatial data processing are performed in R version 4.4.1. Initial data preparation and spatial operations are implemented in R through the RStudio 2024.12.0+467 interface, using dplyr 1.1.4 for data processing and sf 1.0-24 for the management and transformation of spatial objects. The tidyverse 2.0.0 and janitor 2.2.1 packages are employed to streamline data manipulation, cleaning, and the standardisation of tabular datasets, ensuring consistent and analysis-ready inputs. Map creation, visualisation, and exploratory spatial analysis are carried out using the tmap 4.2, tmaptools 3.3, and leaflet 2.2.3 packages, which enabled the production of both static and interactive cartographic outputs suitable for detailed spatial interpretation.

During the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGPT-4 by OpenAI in order to enhance the phrasing of certain sentences and to correct potential grammatical errors, as none of the authors are native English speakers. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

3. Results

3.1. Per-Hectare Profitability Patterns for Agricultural and Forest Land

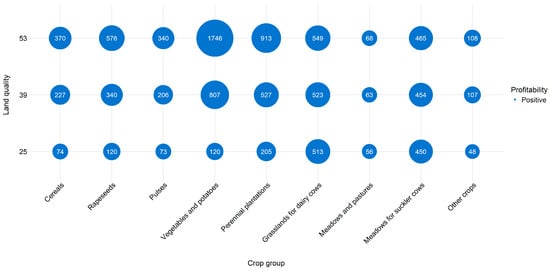

Profitability in agricultural land use varies considerably across different crop groups and land quality points. As shown in Figure 3, land quality is a major determinant of economic performance, with a land quality score above 45 generally classified as high-quality agricultural land. In these areas, local municipalities often restrict land use changes to preserve the productive potential of land.

Figure 3.

Average profitability in agricultural land use, 2019–2024 (EUR/ha).

Cereals and pulses show consistently positive profitability across all land quality classes, reflecting their relatively low input requirements and stable market demand. In contrast, the profitability of vegetables, potatoes, and perennial plantations tends to decline sharply on lower quality land. These crop groups are more input and labour intensive, making them less economically viable on soils of lower quality.

Meadows and pastures generally show lower profitability compared to cultivated crops. This reflects their primary function in supporting the livestock sector through feed provision, sustainable grazing, and ecosystem services, rather than generating direct market revenue. As illustrated in Figure 2, the profitability of meadows and pastures is several times lower than that of cereals, rapeseeds, and pulses. However, when these grasslands are used as feed sources within livestock sector, they contribute significantly to overall farm profitability.

The other crops category (e.g., mustard, flaxseed, nectar plants, and herbs) shows the lowest and most variable profitability. Despite some potential in niche markets, these crops often face economic challenges due to limited economies of scale and lower overall market returns.

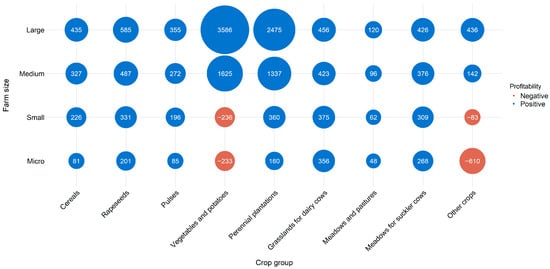

While land quality is a key determinant of agricultural profitability, farm size is also a critical factor influencing economic outcomes. As shown in Figure 4, larger farms tend to achieve higher profitability, benefiting from economies of scale, more efficient use of inputs, and better access to modern technologies and markets. In contrast, smaller farms often face structural disadvantages that limit profitability. This is especially evident in capital- and labour-intensive sectors such as vegetable and potato production. For instance, small and micro farms engaged in vegetable and potato cultivation show average losses exceeding EUR 230/ha, while other crops category (including mustard, flaxseed, nectar plants, and herbs such as lavender, chamomile, and caraway) records losses of more than EUR 600/ha losses. These losses would be even more pronounced without income support, highlighting the structural dependence of small and micro farms on subsidy payments to sustain production.

Figure 4.

Average profitability in agriculture across different crop groups and farm size categories, 2019–2024 (EUR/ha).

Cereals, rapeseeds, and pulses maintain stable positive returns across all farm sizes, likely due to lower input intensity and greater compatibility with mechanised farming. Perennial plantations and grassland systems also show positive returns.

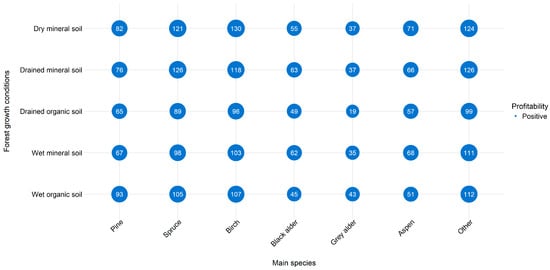

Yearly profitability in forest land use ranges from EUR 7 to 153 per hectare, depending on the dominant tree species and forest growth conditions. While revenue primarily depends on the main tree species, costs vary based on forest growth conditions. Coniferous species, such as pine and spruce, are highly profitable across all forest growth conditions due to their high assortment prices and the larger proportion of high value assortments, particularly saw logs.

Although birch saw logs are not produced in Latvia, a significant share of birch is sold as veneer logs, which represent the most valuable tree assortment. This makes birch one of the most profitable tree species. In contrast, the profitability of deciduous species such as black alder, grey alder, and aspen is lower, as these trees mainly yield packing case timber, pulpwood, and firewood, lower-quality assortments that fetch lower prices.

Other tree species, including oak, ash, and linden, exhibit the highest profitability due to their superior assortment quality, high market prices, and relative rarity in Latvia. When comparing profitability across different forest growth conditions, the highest returns are achieved on dry mineral soils, while the lowest are observed on wet organic soils. This is because, despite higher forestry costs, dry soils tend to produce significantly higher yields per hectare (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Average profitability in forest land use, 2019–2024 (EUR/ha).

3.2. Sensitivity Analysis of Profitability Calculations

The sensitivity analysis, based on extreme yet realistic price conditions observed between 2019 and 2024, confirms the robustness of the profitability comparison between agriculture and forestry. Even under the most favourable agricultural conditions (2022 prices, 22% above average) and the least favourable forestry conditions (2020 prices, 15% below average), there remain specific farm types and production systems for which afforestation represents a more economically viable option (Appendix A.8). Notably, other crops (e.g., mustard, flaxseed, nectar plants, herbs) managed by small and micro farms, as well as permanent grasslands and meadows and pasture not used for livestock feeding, continue to exhibit negative or marginal profitability. In these cases, afforestation, particularly with economically competitive species such as spruce and birch, yields higher returns, even under conservative forestry price assumptions.

3.3. Mapping Agricultural and Forest Land Profitability

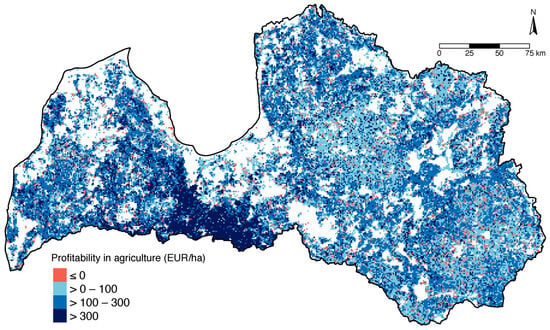

Figure 6 illustrates substantial spatial variation in agricultural profitability across Latvia. The highest profitability levels (in dark blue) are concentrated in limited areas, primarily in the southern part of the country. However, these high-profit zones are relatively sparse. The majority of agricultural land falls within the moderate profitability range (in medium blue), with widespread distribution across central, western, and parts of eastern Latvia. Areas with low profitability (in light blue) or financial losses (in red) are more prevalent in the eastern, southeastern, and some north-central regions.

Figure 6.

Spatial distribution of average agricultural profitability in Latvia, 2019–2024 (EUR/ha).

This spatial distribution reflects the influence of both natural and structural factors. Soils with lower fertility, smaller and fragmented land parcels, and limited market access contribute to the lower profitability observed in certain regions. In contrast, areas with better soil conditions, more consolidated farms, and improved infrastructure tend to perform better economically.

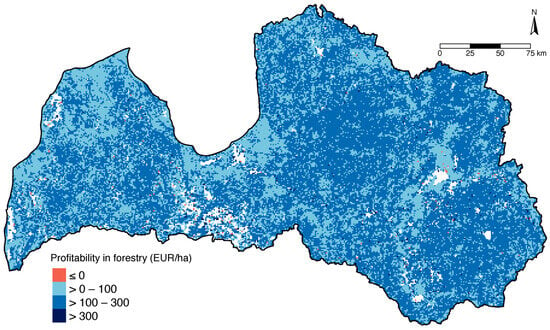

In contrast, forestry profitability (Figure 7) shows a more spatially consistent distribution, with the majority of grid cells falling within the low to moderate profitability range (in light and medium blue). High-profit areas (in dark blue) are relatively limited and scattered, while zones with negative returns (in red) are rare and highly localised. This overall pattern indicates that forestry tends to generate more consistent, albeit modest, economic returns across a wide range of biophysical conditions. As such, forestry may represent a more resilient land use option in areas where agricultural profitability is low or highly variable.

Figure 7.

Spatial distribution of average forestry profitability in Latvia, 2019–2024 (EUR/ha).

4. Discussion

4.1. Profitability Trade-Offs Between Agriculture and Forestry

The profitability analysis across agricultural and forest land use systems reveals that not all agricultural activities are economically viable, particularly on small and micro farms cultivating vegetables and potatoes, perennial crops or managing grasslands. In cases where agricultural land consistently operates at a loss, there is a growing rationale to consider alternative land use production systems. One such option is afforestation, which, in certain conditions, offers not only competitive profitability but also additional ecosystem benefits. Targeted afforestation, particularly with species like spruce or birch, which have shown strong profitability on dry and drained mineral soils, and drained organic soils, may serve as a productive alternative, especially when aligned with public policy goals in climate, biodiversity, and rural development. This perspective does not advocate afforestation across all low-performing farmland, but it does support strategic integration of forestry into land use planning, where economic performance, soil characteristics, and farm structure indicate limited agricultural viability.

This aligns with findings by Lubowski, Plantinga, and Stavins (2006), who showed that land quality is a key determinant of the opportunity cost of afforestation and the potential supply of carbon sequestration from land use change [59]. Their analysis demonstrated that higher quality agricultural land is less likely to be converted to forest, as its productivity in crop production increases the economic trade-offs of afforestation. These findings highlight the importance of incorporating regional land use characteristics and local economic conditions into assessments of afforestation potential and policy design.

Profitability signals alone may not be sufficient to drive land use change, particularly when afforestation requires significant upfront investment and yields delayed returns. Many small and micro farmers, as indicated by Nipers and Pilvere (2020), are often seniors and lack spare financial resources [60]. They rely on current cash flows and lack economic mobility, making it challenging for them to find the financial resources needed to invest in afforestation, even with the available support measures. Additionally, West et al. (2020) indicate that incentives for ecosystem services payments are restricted to the first forest rotation, and enrolment in afforestation programmes on various factors other than profitability [18].

Returning to methodological challenges, Rämö et al. (2023) demonstrate that higher interest rates necessitate increased subsidies to make forestry as profitable as agriculture [17]. West et al. (2020) determined the NPV of forests over a 30-year rotation cycle by considering the anticipated felling volumes, prices, and management costs for various assortments [18]. They then converted the NPV into equivalent annual payments using a discount rate of 8%, following a standard annual equivalent value (AEV) approach. Consequently, discounting leads to significantly lower NPV and AEV values at higher interest rates, making forestry appear less competitive under certain conditions.

In contrast, the forest profitability methodology we propose avoids discounting by focusing on current-year values, specifically, annual biomass accumulation, market prices, and cost data. This allows for relatively precise annual calculations of the support payments needed to ensure income equivalence with agriculture. It is thus best interpreted as a static, annually updated proxy, not a substitute for discounted cash flow analysis.

The deposit-based measure differs conceptually from standard NVP, AEV, or LEV approaches in three ways: (1) it uses current prices and costs without projecting future trajectories; (2) it expresses forestry returns as an annual flow comparable to agricultural profit; and (3) it captures the option value of selling land or standing timber before the end of a full rotation [61]. In practice, this means that the ranking of land use options may diverge from conventional discounted assessments, especially under conditions of high interest rates or volatile price expectations.

However, this annualised structure also introduces a key limitation: the framework assumes price and cost constancy within the assessment year and does not account for future volatility, climatic risks, or natural disturbances unless data are regularly updated. As such, the deposit-based approach should be understood as a dynamic tool that requires regular annual recalibration to remain accurate and policy-relevant. Once the framework structure is established, recalculating profitability with updated data is straightforward, allowing for timely integration of changing market and environmental conditions.

4.2. Institutional Constraints and Policy Implications

Although this study focuses primarily on profitability, land use decisions are influenced by broader institutional and policy environments. Agricultural and forest land uses generate societal value beyond private income, including food and raw material production, water and nutrient cycling, biodiversity conservation, climate change mitigation, and the preservation of rural landscapes. These public goods are reflected in EU policies such as the European Green Deal, which aims to achieve climate neutrality; the Paris Agreement, which seeks to limit global warming to well below 2 °C; the EU Biodiversity Strategy, which focuses on protecting and restoring ecosystems; and the EU Water Framework Directive, which aims to achieve good qualitative and quantitative status of all water bodies. Together, these policies call for multifunctional and sustainable land use. Our framework can be extended to incorporate these additional benefits alongside profitability, allowing a more comprehensive evaluation on land use options in policy analysis.

In many cases, support payments maintain the economic viability of small-scale farming. For cereals, the share of profit attributed to support payments varies significantly by farm size. In large farms, support payments constitute approximately 31% of total profitability, while in medium farms it rises to 41%. The reliance increases further for small farms, where 59% of profits depend on support payments. Notably, in micro farms, profitability would be negative without support payments, with support making up over 166% of their net returns, indicating structural dependence on policy support mechanisms for continued operation. This pattern is largely explained by the higher yields and stronger economic competitiveness of large farms, while support payment rates are broadly similar across farm size categories. To avoid circular reasoning, where support-driven profits are used to justify continuation of current land use, profitability-based tools must be interpreted in light of policy dependence.

For land use policy planning, spatially explicit profitability mapping provides a valuable tool to identify areas where current agricultural production may be economically unsustainable. In such cases, targeted support for afforestation, extensification, or diversification could lead to more efficient land use and better alignment with environmental and climate goals. Rather than preserving all agricultural land at any cost, public funding should be directed toward land uses that deliver both private and public value, with outcomes measured through clear indicators.

While profitability is central to individual decisions, sustainable land use transitions require policy instruments that link economic incentives with environmental objectives. The CAP plays a crucial role in this process by promoting eco-schemes and performance-based payments for sustainable practices [62,63], implemented through Member States’ differentiated strategic plans, which vary in eco-scheme design, intervention intensity, and spatial targeting [64]. Parcel-level profitability mapping can support this performance-oriented approach by identifying where agricultural profitability is marginal and afforestation becomes economically competitive, thereby informing spatially targeted policy design within each Member State’s CAP implementation. Future reforms should ensure that landowners in low-return areas are not locked into unviable production systems but are instead supported in transitioning to alternative land uses that offer greater long-term value.

4.3. Transferability and Generalisation of the Framework

This study applies the land use profitability framework to Latvia, but the underlying logic is designed to be transferable to other regions and policy contexts. It is important to emphasize that the framework is intended for land used in productive agriculture and forestry, where economic returns are derived from crop or timber outputs. It is not designed to assess profitability on non-productive land such as protected areas, peatlands under restoration, or urban/peri-urban zones, where market-based returns are not the primary management objective. Applying the framework to such areas would misrepresent its purpose and limits.

In transferring the approach to other regions, adjustments are needed to reflect regional land use systems, biophysical realities, policy instruments, and climate contexts. However, where land is used primarily for production, the core logic of the framework, comparing annualised economic returns across land use types at the parcel level, remains applicable and informative for spatially targeted land use planning.

The framework has three core components: (1) a consistent methodology for calculation annual agricultural profit and forestry deposit flows at the parcel level; (2) integration of spatial, biophysical and economic data to derive these indicators; (3) spatial mapping of profitability patterns to support informed evaluation of where afforestation could be considered as a viable economic alternative to agriculture. Only the empirical parameterisation of these components is country-specific, while the structure of the approach is generalisable.

Transferring the framework to new contexts mainly requires replacing input data with region-specific information on land quality, farming systems, and economic conditions. For instance, in Mediterranean regions, land use systems are shaped by frequent droughts, fire disturbances, and complex silvo-pastoral mosaics. As shown by recent studies, adapting economic assessments in these areas requires integrating climate-resilient management practices, species selection suited to semi-arid conditions, and the multifunctional role of woody vegetation. These factors can be incorporated through context-specific parameterisation of yield expectations, risk profiles, and input–output relationships [65,66]. Land quality indices, for example, can be replaced with national measures such as soil classification, climatic zones, or productivity indices used in national land evaluation systems [67]. Agricultural profitability can be estimated using data from farm accountancy networks, surveys, or standard gross-margin budgets where harmonised farm-level data (e.g., FADN) are not available [68]. Forestry parameters can likewise be adjusted to reflect region-specific species composition, assortment structures, management costs, and market prices.

Because the framework relies on transparent, annually based indicators, it can be easily recalibrated using updated or region-specific input data. Changes in prices, costs, climatic or environmental risks, or support levels can be readily incorporated, enabling the framework to remain relevant under evolving economic conditions and data availability. This adaptability supports its integration into existing data systems and allows for consistent comparison across different regions or time periods.

It is important to note that while the framework offers a structured and scalable foundation for comparing economic returns of land use options, it does not currently incorporate behavioural responses, long-term uncertainty, or non-economic constraints influencing land use decisions. Nevertheless, it can serve as a screening and decision-support tool in early policy planning stages and as a foundation for further multi-objective assessment.

4.4. Multi-Objective Land Use Planning and Future Research Directions

While this study primarily focuses on economic profitability, the proposed framework holds considerable potential for advancing multi-objective land use planning. By enabling parcel-level comparisons of agricultural returns and forestry deposit values, it establishes a strong foundation for integrated land use policy assessments that align economic, environmental, and social objectives. When combined with spatial indicators such as labour demand, net GHG emissions, or habitat quality, the framework can support the strategic identification of land use transitions that deliver co-benefits for climate mitigation, biodiversity conservation, and rural development.

This direction aligns with growing recognition in land-system science that land use decisions must account for overlapping and sometimes competing objectives [69,70,71]. Parcel-level profitability maps can serve as a critical layer in spatial planning tools, guiding where afforestation, extensification, or landscape restoration could deliver both ecological and economic gains. Such tools are increasingly necessary to operationalise national climate strategies, biodiversity targets, and the EU Green Deal commitments in spatially explicit and cost-effective ways.

Importantly, the framework also provides a basis for addressing social equity and territorial cohesion. In many marginal areas, continued agricultural activity is sustained through undercompensated labour or dependence on support payments [72], raising concerns about the long-term viability and fairness. Identifying where these patterns persist can inform just transition policies that combine environmental objectives with measures to support rural livelihoods, sustain services, and mitigate social risks.

Looking forward, further research should focus on expanding the framework to incorporate additional performance indicators beyond profitability. Existing spatial methodologies for evaluating employment outcomes [43] and biodiversity [73] demonstrate the feasibility of a multi-criteria assessment approach. Developing an integrated decision-support system that includes these dimensions would allow policymakers to better assess trade-offs and synergies across multiple objectives, including climate resilience, food security, ecosystem integrity, and social well-being.

Finally, the framework establishes a basis for more adaptive and evidence-based land use policy in the future. Its structure is well-suited for integration into tools that can incorporate regularly updated data, allowing policymakers to respond to changing economic and environmental conditions as they emerge. This capacity for gradual refinement is particularly important in regions where land use dynamics are influenced by both global pressures and local constraints. In this way, the proposed approach offers a scalable and transferable foundation for guiding sustainable land use policy and transitions.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the importance of incorporating spatially explicit profitability assessments into land use planning and policy development. Applied in Latvia, the results show that profitability varies significantly across land quality, farm size, crop types, and dominant tree species, indicating that uniform land management strategies are insufficient. Integrating profitability data into decision making can help identify areas were afforestation, agricultural support, or diversification efforts would be most effective. Sensitivity analysis further confirms that even under the most favourable conditions for agriculture and least favourable for forestry, afforestation remains a rational choice for certain low-performing land uses and farm types. This study contributes a scalable and transferable approach to land use assessment that goes beyond profitability. However, the framework has limitations. It assumes price and cost stability within the year of analysis and requires regular recalculation to reflect new market or environmental data. It does not yet account for long-term risks, behavioural responses, or non-economic factors influencing land use. As future research expands its multi-objective capabilities, the framework can serve as a central tool in the transition toward sustainable and resilient land use systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.B. and A.N.; methodology, K.B., U.D.V., A.N.; software, U.D.V., K.B.; validation, K.B. and A.N.; formal analysis, U.D.V., K.B.; investigation, A.N.; resources, A.N., I.P.; data curation, K.B., U.D.V., A.N.; writing—original draft preparation, K.B., U.D.V.; writing—review and editing, A.N., I.P.; visualization, U.D.V., K.B.; supervision, A.N.; I.P.; project administration, I.P.; funding acquisition, I.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was promoted with the support of the project Strengthening Institutional Capacity for Excellence in Studies and Research at LBTU (ANM1), project No. 5.2.1.1.i.0/2/24/I/CFLA/002, sub-project No. 3.2.-10/187 (AF14).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in DataverseLV at: https://doi.org/10.71782/DATA/KINURI.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Table A1.

Farm size groups in different agricultural sectors.

Table A1.

Farm size groups in different agricultural sectors.

| Agricultural Sector | Farm Size, ha | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large Farms | Medium Farms | Small Farms | Micro Farms | |

| Cereals, rapeseeds, pulses | >300 | >100, ≤300 | >20, ≤100 | ≤20 |

| Vegetables (with potatoes) | >30 | >10, ≤30 | >2, ≤10 | ≤2 |

| Perennial plantations | >30 | >10, ≤30 | >2, ≤10 | ≤2 |

| Other crops (e.g., mustard, flaxseed, nectar plants, herbs, lavender, chamomile, caraway) | >150 | >50, ≤150 | >10, ≤50 | ≤10 |

| Fallow land | >300 | >100, ≤300 | >20, ≤100 | ≤20 |

| Grasslands | >300 | >100, ≤300 | >20, ≤100 | ≤20 |

| Meadows and pastures | >300 | >100, ≤300 | >20, ≤100 | ≤20 |

| Dairy cows (with calves) | >200 | >30, ≤200 | >4, ≤30 | ≤4 |

| Suckling cows (with calves) | >200 | >30, ≤200 | >4, ≤30 | ≤4 |

Appendix A.2

Table A2.

Estimated data for cereal production equations.

Table A2.

Estimated data for cereal production equations.

| Factor | Large Farms | Medium Farms | Small Farms | Micro Farms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional farms | ||||

| Price (EUR/t) | 120.07 | 118.87 | 118.27 | 117.67 |

| Average yield (t/ha) | land quality points * 0.08365 | |||

| Support (EUR/ha) | 134.04 | 134.04 | 134.04 | 134.04 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | 121.44 | 147.20 | 211.97 | 324.58 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | 149.34 | 126.56 | 96.19 | 71.82 |

| Organic farms | ||||

| Price (EUR/t) | 163.30 | 161.67 | 160.85 | 160.04 |

| Average yield (t/ha) | land quality points * 0.03967 | |||

| Support (EUR/ha) | 248.41 | 248.41 | 248.41 | 248.41 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | 121.44 | 147.20 | 211.97 | 324.58 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | 141.24 | 119.69 | 90.97 | 71.82 |

Table A3.

Estimated data for rapeseeds production equations.

Table A3.

Estimated data for rapeseeds production equations.

| Factor | Large Farms | Medium Farms | Small Farms | Micro Farms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional farms | ||||

| Price (EUR/t) | 294.48 | 291.54 | 290.07 | 288.59 |

| Average yield (t/ha) | land quality points * 0.05458 | |||

| Support (EUR/ha) | 155.26 | 155.26 | 155.26 | 155.26 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | 121.44 | 147.20 | 211.97 | 324.58 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | 267.88 | 248.04 | 230.68 | 193.47 |

| Organic farms | ||||

| Price (EUR/t) | 400.50 | 396.49 | 394.49 | 392.49 |

| Average yield (t/ha) | land quality points * 0.03526 | |||

| Support (EUR/ha) | 134.04 | 134.04 | 134.04 | 134.04 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | 121.44 | 147.20 | 211.97 | 324.58 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | 150.97 | 139.79 | 130.00 | 109.03 |

Table A4.

Estimated data for pulses equations.

Table A4.

Estimated data for pulses equations.

| Factor | Large Farms | Medium Farms | Small Farms | Micro Farms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional farms | ||||

| Price (EUR/t) | 171.21 | 169.50 | 168.64 | 167.78 |

| Average yield (t/ha) | land quality points * 0.05629 | |||

| Support (EUR/ha) | 216.30 | 216.30 | 216.30 | 216.30 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | 121.44 | 147.20 | 211.97 | 324.58 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | 236.60 | 200.50 | 152.38 | 120.30 |

| Organic farms | ||||

| Price (EUR/t) | 232.84 | 230.51 | 229.35 | 228.19 |

| Average yield (t/ha) | land quality points * 0.02710 | |||

| Support (EUR/ha) | 309.36 | 309.36 | 309.36 | 309.36 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | 121.44 | 147.20 | 211.97 | 324.58 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | 208.17 | 176.41 | 134.07 | 105.85 |

Table A5.

Estimated data for vegetable and potato production equations.

Table A5.

Estimated data for vegetable and potato production equations.

| Factor | Large Farms | Medium Farms | Small Farms | Micro Farms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional farms | ||||

| Price (EUR/t) | 264.37 | 261.37 | 260.40 | 259.08 |

| Average yield (t/ha) | 25.22 | 22.62 | 19.04 | 17.12 |

| Support (EUR/ha) | 520.37 | 520.37 | 520.37 | 520.37 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | 1740.64 | 2980.80 | 3436.38 | 3941.28 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | 1525.17 | 1525.17 | 1525.17 | 1525.17 |

| Organic farms | ||||

| Price (EUR/t) | 365.62 | 361.96 | 360.13 | 358.30 |

| Average yield (t/ha) | 19.89 | 17.80 | 15.02 | 13.49 |

| Support (EUR/ha) | 909.71 | 909.71 | 909.71 | 909.71 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | 1740.64 | 2980.80 | 3436.38 | 3941.28 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | 1090.96 | 1090.96 | 1090.96 | 1090.96 |

Table A6.

Estimated data for production of perennial plantations equations.

Table A6.

Estimated data for production of perennial plantations equations.

| Factor | Large Farms | Medium Farms | Small Farms | Micro Farms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Price (EUR/t) | 489.41 | 484.52 | 482.07 | 479.62 |

| Average yield (t/ha) | 9.05 | 7.44 | 6.37 | 5.83 |

| Support (EUR/ha) | 267.77 | 267.77 | 267.77 | 267.77 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | 1894.46 | 2208.00 | 2576.00 | 2649.60 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | 327.32 | 327.32 | 327.32 | 327.32 |

Table A7.

Estimated data for fallow land equations.

Table A7.

Estimated data for fallow land equations.

| Factor | Large Farms | Medium Farms | Small Farms | Micro Farms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional farms | ||||

| Revenue (EUR/ha) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Support (EUR/ha) | 124.01 | 124.01 | 124.01 | 124.01 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | 56.67 | 58.88 | 105.98 | 144.26 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | 49.17 | 49.17 | 49.17 | 49.17 |

| Organic farms | ||||

| Revenue (EUR/ha) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Support (EUR/ha) | 217.07 | 217.07 | 217.07 | 217.07 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | 56.67 | 58.88 | 105.98 | 144.26 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | 81.80 | 81.80 | 81.80 | 81.80 |

Table A8.

Estimated data for grasslands equations.

Table A8.

Estimated data for grasslands equations.

| Factor | Large Farms | Medium Farms | Small Farms | Micro Farms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Price (dry matter) (EUR/t) | 105.26 | 105.26 | 105.26 | 105.26 |

| Average yield (dry matter) (t/ha) | 2.20 | 2.20 | 2.20 | 2.20 |

| Support (EUR/ha) | 140.34 | 140.34 | 140.34 | 140.34 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | 129.54 | 220.80 | 291.46 | 453.38 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | 154.39 | 130.84 | 122.99 | 78.50 |

Table A9.

Estimated data for meadows and pastures equations.

Table A9.

Estimated data for meadows and pastures equations.

| Factor | Large Farms | Medium Farms | Small Farms | Micro Farms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Price (EUR/t) | 39.05 | 39.05 | 39.05 | 39.05 |

| Average yield (t/ha) | 3.65 | 3.00 | 2.35 | 1.86 |

| Support (EUR/ha) | 137.90 | 137.90 | 137.90 | 137.90 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | 24.29 | 44.16 | 59.62 | 92.74 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | 136.11 | 115.34 | 108.42 | 69.21 |

Table A10.

Estimated data for other crops (e.g., mustard, flaxseed, nectar plants, herbs, lavender, chamomile, caraway) equations.

Table A10.

Estimated data for other crops (e.g., mustard, flaxseed, nectar plants, herbs, lavender, chamomile, caraway) equations.

| Factor | Large Farms | Medium Farms | Small Farms | Micro Farms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Price (EUR/t) | 1848.88 | 1848.88 | 1848.88 | 1848.88 |

| Average yield (t/ha) | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.45 |

| Support (EUR/ha) | 169.27 | 169.27 | 169.27 | 169.27 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | 445.28 | 758.08 | 1006.85 | 1550.75 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | 119.95 | 101.65 | 77.25 | 60.99 |

Table A11.

Estimated data for milk production equations.

Table A11.

Estimated data for milk production equations.

| Factor | Large Farms | Medium Farms | Small Farms | Micro Farms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Price (EUR/t) | 210.09 | 207.99 | 206.94 | 205.89 |

| Average yield (t/ha) | 7.48 | 7.48 | 7.48 | 7.48 |

| Support (EUR/ha) | 237.45 | 237.45 | 237.45 | 237.45 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | 704.35 | 721.28 | 761.76 | 772.80 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | 649.21 | 649.21 | 649.21 | 649.21 |

Table A12.

Estimated data for suckler cow sector equations (calve for sales).

Table A12.

Estimated data for suckler cow sector equations (calve for sales).

| Factor | Large Farms | Medium Farms | Small Farms | Micro Farms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Price (EUR/t) | 2508.33 | 2483.46 | 2470.92 | 2458.38 |

| Average yield (t/ha) | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.35 |

| Support (EUR/ha) | 115.64 | 115.64 | 115.64 | 115.64 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | 194.30 | 235.52 | 298.08 | 334.88 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | 373.03 | 373.03 | 373.03 | 373.03 |

Table A13.

Estimated data for sheep farming sector equations.

Table A13.

Estimated data for sheep farming sector equations.

| Factor | Large Farms | Medium Farms | Small Farms | Micro Farms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Price (EUR/t) | - | 2475.00 | 2462.50 | 2450.00 |

| Average yield (t/ha) | - | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Support (EUR/ha) | - | 31.46 | 31.46 | 31.46 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | - | 66.24 | 92.74 | 103.04 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | - | 33.78 | 92.74 | 103.04 |

Appendix A.3

Table A14.

Proportion of wood assortments from wood to be obtained in final felling, depending on the dominant tree species.

Table A14.

Proportion of wood assortments from wood to be obtained in final felling, depending on the dominant tree species.

| Dominant Tree Species | Type of Assortments (Proportion) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Packing Case Timber | Veneer Logs | Saw Logs | Paper Wood | Firewood | |

| Pine | 0.05 | - | 0.60 | 0.30 | 0.05 |

| Spruce | 0.05 | - | 0.60 | 0.30 | 0.05 |

| Birch | 0.15 | 0.35 | 0.05 | 0.40 | 0.05 |

| Aspen | 0.25 | - | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.25 |

| Black alder | 0.05 | - | 0.40 | 0.45 | 0.10 |

| Grey alder | 0.50 | - | - | - | 0.50 |

| Other species | 0.15 | - | 0.45 | 0.30 | 0.10 |

Table A15.

Proportion of wood assortments from wood to be obtained in thinning, depending on the dominant tree species.

Table A15.

Proportion of wood assortments from wood to be obtained in thinning, depending on the dominant tree species.

| Dominant Tree Species | Type of Assortments (Proportion) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Packing Case Timber | Veneer Logs | Saw Logs | Paper Wood | Firewood | |

| Pine | 0.05 | - | 0.55 | 0.35 | 0.05 |

| Spruce | 0.20 | - | 0.35 | 0.30 | 0.15 |

| Birch | 0.10 | 0.25 | - | 0.60 | 0.05 |

| Aspen | 0.35 | - | 0.05 | 0.20 | 0.40 |

| Black alder | 0.05 | - | 0.30 | 0.50 | 0.15 |

| Grey alder | 0.60 | - | - | - | 0.40 |

| Other species | 0.15 | - | 0.45 | 0.30 | 0.10 |

Table A16.

Prices of different wood assortments depending on the dominant tree species.

Table A16.

Prices of different wood assortments depending on the dominant tree species.

| Dominant Tree Species | Price (EUR/m3) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Packing Case Timber | Veneer Logs | Saw Logs | Paper Wood | Firewood | |

| Pine | 51 | - | 73 | 53 | 30 |

| Spruce | 51 | - | 74 | 50 | 30 |

| Birch | 43 | 81 | 77 | 59 | 30 |

| Aspen | 43 | - | 61 | 48 | 30 |

| Black alder | 43 | - | 53 | 43 | 30 |

| Grey alder | 43 | - | - | - | 30 |

| Other species | 43 | - | 115 | 57 | 30 |

Appendix A.4

Table A17.

The costs of silvicultural measures depending on the dominant tree species and forest type in rotation cycle.

Table A17.

The costs of silvicultural measures depending on the dominant tree species and forest type in rotation cycle.

| Dominant Tree Species | Forest Type | Costs (EUR/ha) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maintenance of Amelioration Systems | Soil Preparation | Seedlings | Planting | Forest Protection | Forest Replenishment | Tending | Young Stand Tending | Underbrush Tending | TOTAL | ||

| Pine | Cladinoso–callunosa | - | 163 | 346 | 144 | 109 | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1309 |

| Pine | Vacciniosa | - | 161 | 402 | 148 | 109 | 68 | 148 | 159 | 200 | 1394 |

| Pine | Myrtillosa | - | 161 | 402 | 148 | 109 | 68 | 148 | 159 | 200 | 1394 |

| Pine | Hylocomniosa | - | 175 | 393 | 157 | 109 | 68 | 159 | 168 | 200 | 1429 |

| Pine | Oxalidosa | - | 175 | 393 | 157 | 109 | 68 | 159 | 168 | 200 | 1429 |

| Pine | Aegopodiosa | - | 175 | 393 | 157 | 109 | 68 | 159 | 168 | 200 | 1429 |

| Pine | Callunoso–sphagnosa | - | 154 | 330 | 153 | 109 | 58 | 136 | 139 | 200 | 1279 |

| Pine | Vaccinioso–sphagnosa | - | 163 | 346 | 144 | 109 | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1309 |

| Pine | Myrtilloso–sphagnosa | - | 163 | 346 | 144 | 109 | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1309 |

| Pine | Myrtilloso–polytrichosa | - | 163 | 346 | 144 | 109 | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1309 |

| Pine | Dryopteriosa | - | 163 | 346 | 144 | 109 | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1309 |

| Pine | Sphagnosa | - | 154 | 330 | 153 | 109 | 58 | 137 | 139 | 200 | 1279 |

| Pine | Caricoso–phragmitosa | - | 163 | 346 | 144 | 109 | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1309 |

| Pine | Dryopterioso–caricosa | - | 163 | 346 | 144 | 109 | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1309 |

| Pine | Filipendulosa | - | 163 | 346 | 144 | 109 | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1309 |

| Pine | Callunosa mel. | 506 | 163 | 346 | 144 | 109 | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1815 |

| Pine | Vacciniosa mel. | 506 | 161 | 402 | 148 | 109 | 68 | 148 | 159 | 200 | 1900 |

| Pine | Myrtillosa mel. | 506 | 175 | 393 | 157 | 109 | 68 | 159 | 168 | 200 | 1935 |

| Pine | Mercurialiosa mel. | 506 | 175 | 393 | 157 | 109 | 68 | 159 | 168 | 200 | 1935 |

| Pine | Callunosa turf. mel. | 506 | 163 | 346 | 144 | 109 | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1815 |

| Pine | Vacciniosa turf. mel. | 506 | 161 | 402 | 148 | 109 | 68 | 148 | 159 | 200 | 1900 |

| Pine | Myrtillosa turf. mel. | 506 | 175 | 393 | 157 | 109 | 68 | 159 | 168 | 200 | 1935 |

| Pine | Oxalidosa turf. mel. | 506 | 175 | 393 | 157 | 109 | 68 | 159 | 168 | 200 | 1935 |

| Spruce | Cladinoso-callunosa | - | 163 | 346 | 144 | 109 | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1309 |

| Spruce | Vacciniosa | - | 161 | 402 | 148 | 109 | 68 | 148 | 159 | 200 | 1394 |

| Spruce | Myrtillosa | - | 161 | 402 | 148 | 109 | 68 | 148 | 159 | 200 | 1394 |

| Spruce | Hylocomniosa | - | 175 | 393 | 157 | 109 | 68 | 159 | 168 | 200 | 1429 |

| Spruce | Oxalidosa | - | 175 | 393 | 157 | 109 | 68 | 159 | 168 | 200 | 1429 |

| Spruce | Aegopodiosa | - | 175 | 393 | 157 | 109 | 68 | 159 | 168 | 200 | 1429 |

| Spruce | Callunoso–sphagnosa | - | 154 | 330 | 153 | 109 | 58 | 136 | 139 | 200 | 1279 |

| Spruce | Vaccinioso–sphagnosa | - | 163 | 346 | 144 | 109 | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1309 |

| Spruce | Myrtilloso–sphagnosa | - | 163 | 346 | 144 | 109 | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1309 |

| Spruce | Myrtilloso–polytrichosa | - | 163 | 346 | 144 | 109 | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1309 |

| Spruce | Dryopteriosa | - | 163 | 346 | 144 | 109 | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1309 |

| Spruce | Sphagnosa | - | 154 | 330 | 153 | 109 | 58 | 137 | 139 | 200 | 1279 |

| Spruce | Caricoso–phragmitosa | - | 163 | 346 | 144 | 109 | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1309 |

| Spruce | Dryopterioso–caricosa | - | 163 | 346 | 144 | 109 | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1309 |

| Spruce | Filipendulosa | - | 163 | 346 | 144 | 109 | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1309 |

| Spruce | Callunosa mel. | 368 | 163 | 346 | 144 | 109 | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1677 |

| Spruce | Vacciniosa mel. | 368 | 161 | 402 | 148 | 109 | 68 | 148 | 159 | 200 | 1762 |

| Spruce | Myrtillosa mel. | 368 | 175 | 393 | 157 | 109 | 68 | 159 | 168 | 200 | 1797 |

| Spruce | Mercurialiosa mel. | 368 | 175 | 393 | 157 | 109 | 68 | 159 | 168 | 200 | 1797 |

| Spruce | Callunosa turf. mel. | 368 | 163 | 346 | 144 | 109 | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1677 |

| Spruce | Vacciniosa turf. mel. | 368 | 161 | 402 | 148 | 109 | 68 | 148 | 159 | 200 | 1762 |

| Spruce | Myrtillosa turf. mel. | 368 | 175 | 393 | 157 | 109 | 68 | 159 | 168 | 200 | 1797 |

| Spruce | Oxalidosa turf. mel. | 368 | 175 | 393 | 157 | 109 | 68 | 159 | 168 | 200 | 1797 |

| Birch | Cladinoso-callunosa | - | 163 | 346 | 144 | 109 | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1309 |

| Birch | Vacciniosa | - | 161 | 402 | 148 | 109 | 68 | 148 | 159 | 200 | 1394 |

| Birch | Myrtillosa | - | 161 | 402 | 148 | 109 | 68 | 148 | 159 | 200 | 1394 |

| Birch | Hylocomniosa | - | 175 | 393 | 157 | 109 | 68 | 159 | 168 | 200 | 1429 |

| Birch | Oxalidosa | - | 175 | 393 | 157 | 109 | 68 | 159 | 168 | 200 | 1429 |

| Birch | Aegopodiosa | - | 175 | 393 | 157 | 109 | 68 | 159 | 168 | 200 | 1429 |

| Birch | Callunoso–sphagnosa | - | 154 | 330 | 153 | 109 | 58 | 136 | 139 | 200 | 1279 |

| Birch | Vaccinioso–sphagnosa | - | 163 | 346 | 144 | 109 | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1309 |

| Birch | Myrtilloso–sphagnosa | - | 163 | 346 | 144 | 109 | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1309 |

| Birch | Myrtilloso–polytrichosa | - | 163 | 346 | 144 | 109 | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1309 |

| Birch | Dryopteriosa | - | 163 | 346 | 144 | 109 | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1309 |

| Birch | Sphagnosa | - | 154 | 330 | 153 | 109 | 58 | 137 | 139 | 200 | 1279 |

| Birch | Caricoso–phragmitosa | - | 163 | 346 | 144 | 109 | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1309 |

| Birch | Dryopterioso–caricosa | - | 163 | 346 | 144 | 109 | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1309 |

| Birch | Filipendulosa | - | 163 | 346 | 144 | 109 | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1309 |

| Birch | Callunosa mel. | 276 | 163 | 346 | 144 | 109 | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1585 |

| Birch | Vacciniosa mel. | 276 | 161 | 402 | 148 | 109 | 68 | 148 | 159 | 200 | 1670 |

| Birch | Myrtillosa mel. | 276 | 175 | 393 | 157 | 109 | 68 | 159 | 168 | 200 | 1705 |

| Birch | Mercurialiosa mel. | 276 | 175 | 393 | 157 | 109 | 68 | 159 | 168 | 200 | 1705 |

| Birch | Callunosa turf. mel. | 276 | 163 | 346 | 144 | 109 | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1585 |

| Birch | Vacciniosa turf. mel. | 276 | 161 | 402 | 148 | 109 | 68 | 148 | 159 | 200 | 1670 |

| Birch | Myrtillosa turf. mel. | 276 | 175 | 393 | 157 | 109 | 68 | 159 | 168 | 200 | 1705 |

| Birch | Oxalidosa turf. mel. | 276 | 175 | 393 | 157 | 109 | 68 | 159 | 168 | 200 | 1705 |

| Aspen | Cladinoso-callunosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 137 | 149 | 200 | 486 |

| Aspen | Vacciniosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 148 | 159 | 200 | 507 |

| Aspen | Myrtillosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 148 | 159 | 200 | 507 |

| Aspen | Hylocomniosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 159 | 168 | 200 | 528 |

| Aspen | Oxalidosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 159 | 168 | 200 | 528 |

| Aspen | Aegopodiosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 159 | 168 | 200 | 528 |

| Aspen | Callunoso–sphagnosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 136 | 139 | 200 | 475 |

| Aspen | Vaccinioso–sphagnosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 137 | 149 | 200 | 486 |

| Aspen | Myrtilloso–sphagnosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 137 | 149 | 200 | 486 |

| Aspen | Myrtilloso–polytrichosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 137 | 149 | 200 | 486 |

| Aspen | Dryopteriosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 137 | 149 | 200 | 486 |

| Aspen | Sphagnosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 137 | 139 | 200 | 475 |

| Aspen | Caricoso–phragmitosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 137 | 149 | 200 | 486 |

| Aspen | Dryopterioso–caricosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 137 | 149 | 200 | 486 |

| Aspen | Filipendulosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 137 | 149 | 200 | 486 |

| Aspen | Callunosa mel. | 184 | - | - | - | - | - | 137 | 149 | 200 | 670 |

| Aspen | Vacciniosa mel. | 184 | - | - | - | - | - | 148 | 159 | 200 | 691 |

| Aspen | Myrtillosa mel. | 184 | - | - | - | - | - | 159 | 168 | 200 | 712 |

| Aspen | Mercurialiosa mel. | 184 | - | - | - | - | - | 159 | 168 | 200 | 712 |

| Aspen | Callunosa turf. mel. | 184 | - | - | - | - | - | 137 | 149 | 200 | 670 |

| Aspen | Vacciniosa turf. mel. | 184 | - | - | - | - | - | 148 | 159 | 200 | 691 |

| Aspen | Myrtillosa turf. mel. | 184 | - | - | - | - | - | 159 | 168 | 200 | 712 |

| Aspen | Oxalidosa turf. mel. | 184 | - | - | - | - | - | 159 | 168 | 200 | 712 |

| Black alder | Cladinoso-callunosa | - | 163 | 346 | 144 | - | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1200 |

| Black alder | Vacciniosa | - | 161 | 402 | 148 | - | 68 | 148 | 159 | 200 | 1285 |

| Black alder | Myrtillosa | - | 161 | 402 | 148 | - | 68 | 148 | 159 | 200 | 1285 |

| Black alder | Hylocomniosa | - | 175 | 393 | 157 | - | 68 | 159 | 168 | 200 | 1320 |

| Black alder | Oxalidosa | - | 175 | 393 | 157 | - | 68 | 159 | 168 | 200 | 1320 |

| Black alder | Aegopodiosa | - | 175 | 393 | 157 | - | 68 | 159 | 168 | 200 | 1320 |

| Black alder | Callunoso–sphagnosa | - | 154 | 330 | 153 | - | 58 | 136 | 139 | 200 | 1170 |

| Black alder | Vaccinioso–sphagnosa | - | 163 | 346 | 144 | - | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1200 |

| Black alder | Myrtilloso–sphagnosa | - | 163 | 346 | 144 | - | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1200 |

| Black alder | Myrtilloso–polytrichosa | - | 163 | 346 | 144 | - | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1200 |

| Black alder | Dryopteriosa | - | 163 | 346 | 144 | - | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1200 |

| Black alder | Sphagnosa | - | 154 | 330 | 153 | - | 58 | 137 | 139 | 200 | 1170 |

| Black alder | Caricoso–phragmitosa | - | 163 | 346 | 144 | - | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1200 |

| Black alder | Dryopterioso–caricosa | - | 163 | 346 | 144 | - | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1200 |

| Black alder | Filipendulosa | - | 163 | 346 | 144 | - | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1200 |

| Black alder | Callunosa mel. | 322 | 163 | 346 | 144 | - | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1522 |

| Black alder | Vacciniosa mel. | 322 | 161 | 402 | 148 | - | 68 | 148 | 159 | 200 | 1607 |

| Black alder | Myrtillosa mel. | 322 | 175 | 393 | 157 | - | 68 | 159 | 168 | 200 | 1642 |

| Black alder | Mercurialiosa mel. | 322 | 175 | 393 | 157 | - | 68 | 159 | 168 | 200 | 1642 |

| Black alder | Callunosa turf. mel. | 322 | 163 | 346 | 144 | - | 61 | 137 | 149 | 200 | 1522 |

| Black alder | Vacciniosa turf. mel. | 322 | 161 | 402 | 148 | - | 68 | 148 | 159 | 200 | 1607 |