Abstract

Forest landscape restoration (FLR) in tropical Africa seeks to improve the ability of degraded forest to provide ecosystem services (ESs) to local communities. The purpose of this study is to present ESs that are mentioned in studies on FLR and methods that best integrate the different categories of ESs that have been identified in tropical Africa. The study followed the PRISMA 2020 statement for reporting systematic reviews. Qualitative and quantitative data were analyzed using agglomerative clustering and multiple correspondence analysis (MCA). The systematic literature review analyzes modalities of ES integration through various studies on FLR in tropical Africa. In most cases, only three of the four ES categories are mentioned, namely provisioning, regulating and supporting services. Primary production is the ES category most frequently mentioned in tropical Africa. In this region, various methods are used to restore forest landscapes (reforestation, savannah protection, agroforestry). This review shows a strong link between ESs, the ES categories, use values and methods of FLR. Therefore, integration of ESs in FLR can contribute to the understanding of how FLR impacts biodiversity, climate change mitigation. improvement of human well-being, etc.

1. Introduction

Tropical forests occupy 7% of Earth’s land surface and are distributed on three continents, including the forests of Amazonia (South America), tropical forests of Africa, and forests of Southeast Asia [1]. These forests are large reservoirs of biodiversity and provide various ecosystem services (ESs) that are crucial to the survival of local communities, the economic development of nations, and the combatting climate change [2,3]. Deforestation and degradation of tropical forests in Africa, however, are threats that reduce the capacity of these ecosystems to provide various services, thereby putting humanity at risk, especially local communities that primarily depend upon these services [4,5]. In the Congo Basin, for example, it has been reported that forests both directly and indirectly ensure the survival of nearly 100 million rural inhabitants [3,6].

In the face of different threats, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the World Resources Institute (WRI) indicated that about 350 million ha could be potentially restored by 2030 at the global scale [7]. About 100 million ha of these forests are found in African countries, as determined following the African Forest Landscape Restoration Initiative (AFR100) that was officially launched during COP21 in Paris, in December 2015 (https://afr100.org/). IUCN and WRI made this global and regional determination using the map that was established by The Global Partnership on Forest and Landscape Restoration [8] (http://pdf.wri.org/world_of_opportunity_brochure_2011-09.pdf (accessed on 7 December 2015)).

Tropical Africa, a vast hot region primarily between the Tropics of Cancer (approx. 23°27′ N) and Capricorn (approx. 23°27′ S), south of the Sahara, features diverse forests and biodiversity facing strong human pressures due to the great dependence of local communities upon biological resources [9]. FLR in particular can contribute to ecosystem restoration and to the improvement of their capacity for providing benefits to local communities [10]. In various tropical countries, degraded ecosystems, while maintaining a certain resilience degree, can have their balance restored after disturbances that are due to anthropogenic factors, while rapidly developing forest cover [11]. To this end, the evaluation of FLR mechanisms appears relevant to understanding their effectiveness in maintaining and enhancing ES and their level of integration [12].

Indeed, FLR and ES are linked in the sense that the maintenance and provision of ES is an indicator for assessing restoration impacts [13,14]. This approach should corroborate the process that is defined by The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity [15], which aims to consider the main ESs that are provided within a given area. This is particularly important for defining adaptive management strategies and mechanisms in the context of REDD+ process implementation. Very little is known regarding studies that have addressed the issue of integrating ESs into evaluations of different interventions, which are related to forest FLR in tropical regions [16,17,18]. Such information is required to reframe and guide national policies and strategies for the implementation of sustainable forest management and restoration of degraded lands programs [19]. Therefore, there is need to review and elucidate FLR studies that have focused upon the integration of ESs in tropical Africa [20,21].

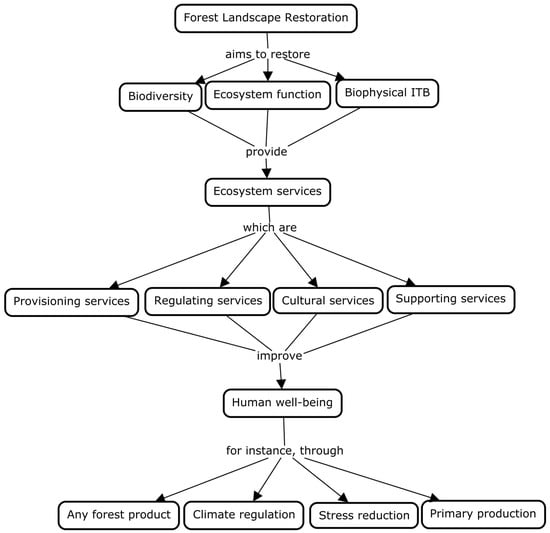

This study attempts to answer the following questions: what are the different ESs that are mentioned in studies on different FLR methods in tropical Africa? Which of the FLR methods best integrates the different categories of ESs identified? We focused on the relationship between ESs and FLR, especially as a landscape is not restored in vain, but rather to create conditions that favor the provision of ESs for the well-being of the population (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual map linking FLR to the concept of ESs: adapted from ref. [13] regarding the pyramid of human well-being that depends on natural capital. Links between concepts are expressed by the words on the arrows. ITB: Interaction through the biosphere.

The interest of this study lies in the systematic evaluation of ecosystem services (ESs) provided by different forest restoration methods in tropical Africa, filling a knowledge gap on the actual effectiveness of restoration approaches in relation to local needs. Its motivation is to show how forest restoration can directly improve human well-being by providing tangible benefits, such as food, clean water, erosion control, and intangible cultural or spiritual values, thus justifying investments in these vital practices.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search and Eligibility Criteria

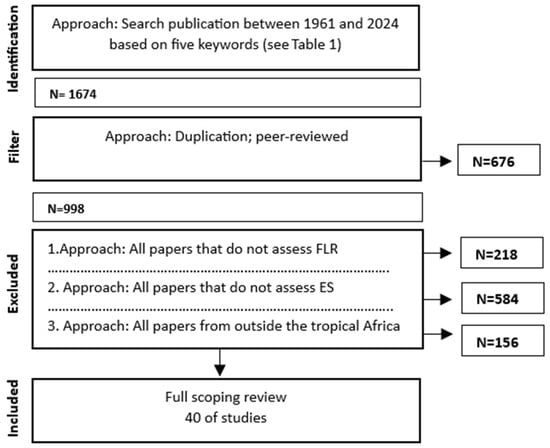

The methodological approach was based on the PRISMA 2020 statement (Supplementary Materials), which is an updated guideline for systematic reviews and meta-analyses [22]. This approach has been recommended by many researchers and editors for literature exclusion and inclusion criteria [23,24,25]. Figure 2 illustrates the design of the search and eligibility criteria.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram for literature exclusion and inclusion criteria [24].

It presents 1674 publications identified between 1961 and 2024, based on the keywords used individually and presented in Table 1. The metadata were mainly obtained from sources, such as Web of Science, CAB Abstracts, Google Scholar, and ResearchGate during the period from March 2023 to February 2024. These were then filtered to include only peer-reviewed publications, removing duplicates, to arrive at the final count of 998 publications”. Subsequently, three exclusion criteria were used, notably (i) all papers that do not assess FLR; (ii) all papers that do not assess ESs; (iii) all papers from outside the tropical Africa. Considering these three criteria, 958 papers were excluded. For this reason, only 40 were included for final analysis (Appendix A). Given the limited number of studies included in the final analysis, we extended our scope to encompass research conducted in subtropical regions near tropical Africa (Coasts of Morocco and Algeria, South Africa). These areas exhibit similar climatic traits to the tropics, justifying their inclusion. In both cases, the majority of low-income populations depend on the ecosystem services of restored landscapes for their survival [26]. Similarly, we considered all relevant studies, not just the most recent ones, to ensure a comprehensive overview.

Table 1.

Keywords used to collect scientific papers and topics considered for the review.

2.2. Analysis Strategy

The analysis focused upon the summary of the ESs that are assessed into FLR in tropical Africa. The variables used to study the sample of 40 articles are: ESs that are cited, forest restoration methods, activities that are related to ES use, ES use values, and study location, with the subcategories of ESs. The relevant database can be found in Appendix B.

Citation frequency (CF) of ESs was determined by dividing the total number of citations for a service by the total number of citations for ecosystem services across all studies.

Subsequently, to produce the related graph, this information was processed using Microsoft Excel 365 (2021). Using R 4.3.2 software [31], the ordination of the MCA (Multiple Correspondence Analysis) was performed using the factoshiny package (http://factominer.free.fr/graphs/factoshiny.html (accessed on 1 July 2023)). This was produced by analyzing similarities between different studies that considered ESs in the evaluation of FLR, as well as the different variables involved in each study (ESs, their categories and use values, FLR methods, and sub-regions of Africa). For cluster analysis, each study (Individuals on the map) was considered as a statistical sample. Then, the silhouette index was calculated using the silhouette package to determine if the data had been correctly partitioned into coherent and well-separated clusters. Generally, a silhouette scores greater than 0.5 indicates good clustering, a score below 0.25 indicates poor clustering, and a score between 0.25 and 0.5 signifies fair clustering [32].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Different ESs Mentioned in FLR Studies

Table 2 illustrates the different ESs that have been considered in tropical Africa in different studies of FLR. Eight ES products were identified, of which five (food, fiber, medicinal plants, firewood, and fresh water) belong to the provisioning service, two to the regulating services: Prevention of erosion and soil fertility maintenance (PESFM) and carbon storage and fixation), and only one to the supporting service (Maintenance of primary productivity). Studies have shown that successful FLR not only restores biodiversity and carbon sequestration but also provides crucial provisioning services. Indeed, considering different ESs in tropical African, FLR allows for more effective, sustainable, and inclusive outcomes by providing a holistic view of benefits and trade-offs, ensuring social equity, long-term financial viability, and the alignment with broader development goals like climate action and poverty reduction [33]. Moreover, no cultural service was cited, notwithstanding its particular interest to local communities in tropical Africa due to their strong attachment to cultures and traditions that have been ingrained for many decades [34,35]. FLR study limited scope may lead to incomplete or ineffective outcomes, failing to address the cultural dimensions that influence human well-being and project success. Indeed, neglecting cultural ecosystem services (non-material benefits like spiritual significance, sense of place, recreation, or esthetic beauty that people derive from forests and landscapes) risks creating restoration projects that do not align with local values, potentially excluding vulnerable groups, causing conflicts, and hindering overall project effectiveness and public engagement, as mentioned by Felipe-Lucia et al. (2024) [36]. Hunt et al. (2023) report the omission of cultural services can result in missed opportunities to generate broad social benefits and secure long-term support for restoration efforts [37].

Table 2.

Analysis of Ecosystem Services (ESs) integrated into Forest Landscape Restoration (FLR) in tropical Africa.

3.1.1. Provisioning Services

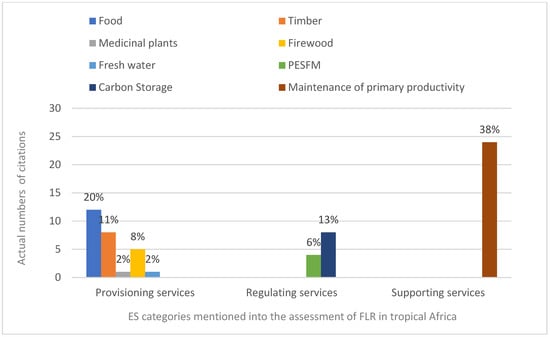

Provisioning services appear to be the most frequently described service among the studies that were reviewed regarding FLR in tropical Africa. These results are due to the heavy dependence of local communities upon these services to meet their daily needs [15]. Indeed, provisioning services with direct use value are tangible, directly measurable, and crucial for the livelihoods of local communities, providing essential goods that are easily linked to tangible economic benefits [13,77,78]. The immediate and visible impacts of changes in these services also make them a priority for research and assessment, even as other services like cultural or regulating services are recognized for their importance [79]. In tropical Africa, provisioning services were identified across the different FLR assessments and accounted for 43% of citations, including 20% for food, 11% for timber, 2% each for medicinal plants and Fresh water and 8% for firewood (Figure 3). The results presented by Pagiola et al. (2007); Ha et al. (2022) [80,81] in tropical Asia and Latin America reveal similar information to those from tropical Africa. These findings involved a direct human dependence on natural ecosystems for essential resources, highlighting the crucial role of FLR in providing tangible goods like food, timber, and medicine, as well as necessities like fuel and clean water. The identification of these provisioning services underscores their importance for livelihoods and well-being but also suggests a need for sustainable management to ensure their continued availability for communities [82]. This highlights the importance of balancing universal human needs with ecological limits to support communities in the long term [83].

Figure 3.

Frequency of citations of ESs in assessments of FLR in tropical Africa. The vertical axis shows the actual numbers, and the columns show the percentages. PESFM: Prevention of erosion and soil fertility maintenance.

The provision of food to local communities by restored landscapes has considerable implications for food security in tropical Africa, as is the case in other tropical areas of the world, thereby increasing the value of FLR [13]. Indeed, agroforestry and reforestation as two of the methods of FLR in Africa demonstrate their critical role in enhancing food security and nutrition by increasing food production of various items like fruits, beans, coffee, and honey, and providing supplementary foods like gum arabic and other edible non-timber forest products (NTFPs). These current findings are consistent with previous research conducted in tropical Asia and Latin America [84]. These outcomes contribute to diversifying food sources, enhancing agricultural yields through integrated systems, and bolstering the overall food system for rural communities around the globe [85]. Ultimately, other types of “food” are not directly mentioned; however, these may have gained value or increased in abundance through FLR, including edible caterpillars [86], domestic animals, bark, nuts in agroforestry systems, reforestation or fencing. These products contribute to the further well-being of local communities. Many evaluations of FLR only assess biodiversity in general, without knowing whether the restoration work that was carried out has provided food for the community in line with their expectations [54,60]

With respect to wood fiber production, the evaluation of FLR activities through reforestation and agroforestry revealed increased tree basal area resulting in enhanced timber production. Protecting savannas, integrating trees into farms through agroforestry, and re-establishing forests via reforestation all support the larger goal of forest landscape restoration, which in turn leads to more sustainable timber production [87]. A study in tropical Asia presented similar results [88]. This comprehensive approach restores ecological functionality and human well-being across landscapes by balancing the conservation of native ecosystems with productive activities, such as growing timber in specific forest areas [23]. However, in most cases in the tropics, timber harvesting in restored forests is subsequently restricted sometimes due to the significant disturbance and potential negative impacts it can have on the forest ecosystem [18], unless the forest is intended for permanent timber production. It is more the integration of non-timber forest products (provisioning services) into the FLR that is perceived as being more important for the population’s right of use, compared to timber [43,62]. The integration of non-timber forest products (NTFPs), which can include food, medicines, and materials for shelter and income, is frequently prioritized in FLR initiatives, as it is seen to be more beneficial and important for the local communities’ rights and livelihoods compared to timber extraction [89].

Regarding medicinal plants, medicinal uses of regenerated species were only noted in some countries (Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger). This suggests a potential gap in research, while other non-timber forest products are not consistently documented for their medicinal applications [89]. These findings are consistent with those found in tropical Asia, where the non-timber forest products assessed did not include medicinal resources [81,84]. This highlights a need for more comprehensive documentation of medicinal plant use across various tropical areas and among different types of forest products to gain a fuller understanding of traditional health practices and their potential for modern research [90]. The lack of these details can have an impact on the total value of the restored forest and call into question the value of the FLR [91].

Regarding the production of firewood, similar results are observed in other tropical regions like Latin America [92,93] and tropical Asia [77]. Given that poor people are dependent on restored forests for fuelwood in tropical Africa [94], integrating fuelwood (firewood) into FLR is crucial because it addresses the dependency of poor communities on restored forests for fuel [95]. This thereby increases the practical value and meaning of restoration efforts for these communities and encouraging their greater involvement and adoption of FLR initiatives in tropical Africa, as is the case in other tropical areas [96,97]. Moreover, without careful management, focusing on fuelwood for FLR can become a short-term solution that compromises the long-term health and resilience of the restored forests, as well as the well-being of the communities dependent on them [23].

For drinking water, a study was carried out on the influence of FLR through reforestation on water resources in South Africa, a subtropical area whose climate is like that of tropical regions. This study concluded that reforestation contributed to the provision of drinking water and domestic work for local communities [49]. In contrast, FLR studies in Africa and other tropical regions like Asia and Latin America do not emphasize the importance of freshwater resources as a key ES. The critical role and valuation of freshwater services are often overlooked, even though their comprehensive valuation is essential for truly understanding the total value of FLR initiatives [98,99]. However, reforestation, being a component of FLR, serves as a natural water filtration system by improving soil health and reducing pollutants, ultimately enhancing both the quantity and quality of available drinking water [100,101]. A lack of clear data on freshwater benefits can lead to underestimating FLR’s worth and allocating insufficient resources for water management, creating a mismatch between social value and actual investment, according to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment [102]. By restoring forest cover, communities can benefit from more stable water resources, supporting their domestic needs [103].

3.1.2. Regulating Services

Few studies have assessed regulating services in the context of FLR in tropical Africa (Table 2). These services concern the PESFM (6% of citations), together with carbon storage and fixation (13% of citations). These two services accounted for 19% of citations (Figure 3). These results are in perfect alignment with those found in other tropical regions [80,90,104,105,106]. The highlighted findings on the PESFM can be explained by the functions of vegetation in intercepting rainwater, slowing runoff, and anchoring the soil with its root system, as emphasized by [107]. The effects of vegetation on rainwater interception, runoff reduction, and soil anchoring have significant consequences for tropical environments [108]. These include enhanced water infiltration, minimized soil erosion, better water quality, and improved slope stability [109]. These outcomes play a vital role in managing stormwater, averting landslides, and preserving the overall health of ecosystems in tropical regions [110]. By recognizing and harnessing the potential of vegetation in these areas, we can better protect and restore ecosystems while addressing essential water management and disaster prevention needs [111].

The findings on carbon storage also align with those found in other tropical regions, including tropical Asia [77,112,113] and Latin America [80,106]. This consistency across different studies highlights the global importance of integrating carbon stocks into forest restoration efforts, such as reforestation, agroforestry and savannah protection, and showcases the significant potential for mitigating climate change through such initiatives in tropical areas [114,115]. Furthermore, ecological forest restoration can increase soil carbon stocks and enhance the resilience of forest ecosystems in the world [116]. Increasing soil carbon can include potential trade-offs in other climate impacts, like reduced albedo in high-latitude regions [117]; the fact that restored carbon stocks often do not reach pristine levels, challenges in achieving high rates of recovery [118]; the possibility of increased greenhouse gas emissions (CO2, CH4, N2O) in certain ecosystem types like wetlands [119]; and a lack of sufficient long-term data to fully understand the implications of different restoration methods and site conditions [120].

Yet, regulation of natural disasters (extended drought, wildfires), which is of great importance especially in regions near the Sahel or East African regions [121] has not been considered in the various studies focusing upon the regulating services that were valued in FLR. This trend also applies to FLR studies conducted in other tropical areas [77,112,122]. This is due to the complexity of modeling these events, limited data and monitoring capabilities, weak institutional capacity for disaster management, and the disconnection between disaster events and forest ecosystems, making it difficult to integrate them into FLR valuations [123]. These challenges are compounded by factors such as increasing population density, resource competition, political instability, and the inadequate recognition of local and traditional knowledge, all of which hinder the effective assessment of disaster impacts and the implementation of mitigation strategies [124]. The omission of natural disaster regulation (drought, wildfires) in FLR studies means that the economic and social impacts of these disasters are underestimated, leading to incomplete valuations of regulating services and potentially hindering the design of effective restoration strategies, as explained by [121]. This gap is critical for regions near the Sahel and East Africa, where these hazards significantly threaten livelihoods, agriculture, and water resources, requiring integrated management and community involvement for resilience [123]. Taking this into account can contribute to updated values of FLR [52,53].

3.1.3. Supporting Services

In tropical Africa, supporting service accounted for 38% of citations and is the most quoted (Table 2 and Figure 3). Implications of FLR on supporting services, specifically those maintaining primary production, were generally positive. Indeed, FLR enhances crucial functions like nutrient cycling and water regulation [125]. By improving soil health, increasing water infiltration, and boosting beneficial microbial activity, FLR creates a more stable foundation for primary production [126]. This is confirmed through several other studies in Latin America [92,105] and in tropical Asia [77,88]. Primary production might be seen as the sole focus in FLR in tropical areas due to the interconnectedness of this process with immediate, tangible benefits such as food security, local livelihoods, and biodiversity conservation [127]. However, the ecological restoration assessments in tropical areas may be incomplete, focusing primarily on primary production while neglecting other crucial supporting ecosystem services like soil formation, biogeochemical cycles, and the maintenance of species habitats [128]. Additionally, the complex and vast nature of tropical ecosystems, coupled with limited resources and the impact of climate change, can make comprehensive monitoring and assessment of all supporting services challenging, leading to a narrow focus on the most visible or immediately impactful aspects [129]. This involved a need for broader assessment methods in tropical ecosystem restoration to ensure a more comprehensive understanding and evaluation of its long-term success and ecological value, beyond just primary productivity [110]. Supporting services would be more involved in the added value of ecological restoration if the role of biodiversity were detailed in the restoration zone [111].

3.1.4. Cultural Services

FLR assessments in tropical Africa generally align with those in Latin America and tropical Asia [76,106]. However, qualitative and quantitative assessments of cultural services are often overlooked or underestimated in tropical Africa compared to studies in Latin America and Asia where these services are assessed in FLR [81,122]. These studies integrate cultural aspects such as traditional knowledge, community engagement, and the cultural significance of landscapes into FLR efforts to enhance human well-being and achieve local goals [81,122]. The non-integration of cultural services in tropical Africa may occur because they are undervalued, seen as less tangible, or difficult to quantify compared to provisioning, regulating or supporting services, which are economic or environmental services, leading to their exclusion in policy and planning [130]. Despite this oversight, cultural services significantly shape the habits, customs, and overall well-being of a population, influencing everything from daily practices to a society’s core values and connection to its environment [113]. Taking these cultural services into account alongside the three other services would contribute to the integration and total economic value of ESs in the FLR assessments [113]. This could add value to the FLR by increasing the potential to attract financial backers, for example [35].

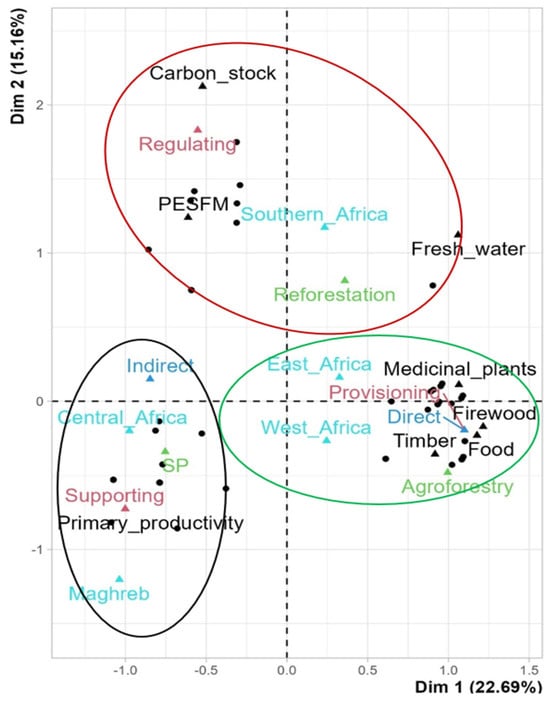

3.2. Typologies of ES Integration in African FLR

Figure 4 showcases a map that categorizes the various citations examined in this literature review on tropical Africa into three distinct clusters. This suggests that there are three types of studies that incorporate ESs in FLR assessments within this region. The average global Silhouette index of 0.51 ± 0.18 signifies a higher value than the threshold for good clustering (0.5), indicating a well-defined and coherent distribution of the studies among these three groups. The first group consists mostly of studies that were conducted in Central Africa, which have integrated only primary production as an ES. The second group consists of studies that were conducted in southern Africa focusing on reforestation by integrating regulating services (carbon stock and PESFM), and provisioning services (Fresh water). The third group consists of studies that were conducted in West and East Africa, which analyzed provisioning ESs by agroforestry. Dimension 1 contrasts studies from Group 1 with those from Group 3 (and part of Group 2), accounting for 22.69% of the variance. Dimension 2 differentiates Group 2 studies from those in Groups 1 and 3 (mostly), capturing 15.16% of the information. Indeed, this detailed categorization provides a clear overview of the existing knowledge, identifies research gaps, and informs future FLR strategies in the region by highlighting different ES integrations and their geographical concentrations. In tropical areas, studies mention that detailed categorization of knowledge about ESs is crucial for effective FLR strategies because it provides a foundational understanding of local resources and the related ESs [16], identifies specific local research needs [99] and pinpoints areas with significant ES concentrations for targeted restoration efforts [85]. This approach allows for customized strategies that align with tropical biodiversity, address specific human needs, and promote sustainable management by highlighting what is known and what needs to be learned [110].

Figure 4.

Relationship between different studies and the modalities of the variables “Ecosystem service categories,” “Forest restoration modality,” “Subregion in Africa,” “Use value” PESFM = Prevention of Erosion and Soil Fertility Maintenance. The modalities are colored according to their variables. Studies (individuals) are represented by black dots. Each circle groups together different individuals (studies) with the variables that characterize the group. The black circle defines group 1, the red color defines group 2, and the green circle corresponds to group 3.

4. Conclusions

This literature review has highlighted integration of ESs in FLR-related assessments in tropical Africa. This study faced challenges with limited data due to strict criteria, even after expanding the scope to include subtropical research. It thus revealed a significant gap where FLR assessments often ignore ESs, focusing narrowly on a few services like primary production instead of a holistic view. Key issues include overly specific research focus, a disconnect between FLR’s potential and practice (often limited to reforestation), sectoral approaches to restoration, and a failure to integrate all ES categories (like provisioning, regulating, etc.), leading to unbalanced strategies and missed opportunities for effective, context-specific restoration, especially in tropical regions. To truly leverage the potential of FLR for population well-being, future research and policy initiatives should prioritize the development of comprehensive assessment frameworks that fully incorporate all ES categories. Doing so will provide the holistic understanding needed to achieve environmental sustainability and enhance community well-being across tropical African landscapes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/land15010050/s1.

Author Contributions

J.-P.M.T. identified the theme and wrote the systematic review. He also analyzed and presented the data. J.S.N., B.S.B., J.-F.B. and D.P.K. reviewed the article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The design and writing of this systematic review received no external funding. Nevertheless, there has been considerable documentary support through the virtual library of Université Laval, Quebec, Canada. Supports from the Leadership and Commitment Scholarship of University Laval (TJPM), RIFM CLIMAT FY2023-24—RAFM-ULAVAL and NSERC Discovery Grants (KDP) are also acknowledged.

Data Availability Statement

The research that is described in this paper used only the review of the literature. No data were collected in situ.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to Willian F.J. Parsons from the University of Sherbrooke, Quebec, Canada, for helping to review this article prior to submission.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no interests whatsoever that could influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Papers Included in the Final Analysis

- Achour, A., Aroula, A., Defaa, C., El Mousadika, A. Msanda, F. 2011. Effet de la mise en défens sur la richesse floristique et la densité dans deux arganeraies de plaine. Actes du Premier Congrès International de l’Arganier, Agadir, Maroc. pp. 60–69. http://webagris.inra.org.ma/doc/ouvrages/arganier2011/arganier060069.pdf

- Aerts, R., November, E., Maes, W., Van der Borght, I., Negussie, A., Aynekulu, E., Hermy, M., Muys, B. 2008. In situ persistence of African wild olive and forest restoration in degraded semiarid savanna. Journal of Arid Environments.Volume 72, Issue 6, Pages 1131–1136, ISSN 0140-1963. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2007.11.009.

- Badji, M., Sanogo, D., Akpo, L. 2014. Dynamique de la vegetation ligneuse des espaces sylvopastoraux villageois mis en defens dans le Sud du Bassin arachidier au Senegal. Bois et Forêts Tropiques 319(1), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.19182/bft2014.319.a20551

- Badji, M., Sanogo, D., Akpo, L.E. 2013. Effet de l’âge de la mise en défens sur la reconstitution de la végétation ligneuse des espaces sylvo pastoraux du sud bassin arachidier (Sénégal). Journal of Applied Biosciences 64, 4876–4887. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272341752.

- Benaradj, A., Boucherit, H., Mederbal, K., Benabdeli, K., Baghdadi, D. 2011. Effect the exclosure on plant diversity of the Hammada scoparia steppe in the Naama steppe courses (Algeria). Journal of Materials & Environmental Science 2, 564–571. https://www.jmaterenvironsci.com/Document/vol2/vol2_S1/27-JMES-S1-19-2011%20benaradj-T6.pdf.

- Boakye, E.A., Gils, H.V., Osei, E.M.J., Asare, V.N.A. 2012. Does forest restoration using taungya foster tree species diversity? The case of Afram Headwaters Forest Reserve in Ghana. African Journal of EcologyVolume 50, Issue 3 p. 319–325. https://doi-org.acces.bibl.ulaval.ca/10.1111/j.1365-2028.2012.01329.x

- Boffa, J.M. 1999. Agroforestry parklands in sub-Saharan Africa. Conservation Guide 34. FAO. http://www.fao.org/docrep/005/x3940e/X3940E10.htm#ch7.4

- Boulvert, Y. 1990. Avancée ou recul de la forêt centrafricaine. Changements climatiques, influence de l’homme et notamment des feux. In Lanfranchi et Schwartz éds.: Paysages quatemaires de 1 ‘Afrique centrale atlantique. Initiations et Didactiques ORSTOM, Paris: 353–366. https://horizon.documentation.ird.fr/exl-doc/pleins_textes/divers11-10/34798.pdf

- Chirwa, P. W. 2014. Pratiques de restauration dans les zones dégradées d’Afrique de l’Est. African Forest Forum, Working Paper Series, Vol. 2(11), 63 pp. https://afforum.org/cgi-sys/suspendedpage.cgi.

- Dauget J.M. et Menaut J.C., 1992. Evolution sur 20 ans d’une parcelle de savane boisée non protégéé du feu dans la réserve de Lamto (Côte-d’Ivoire). CODENCNDLAR, 47 (2) 621–630. https://www.e-periodica.ch/cntmng?pid=can-002%3A1992%3A47%3A%3A812

- De Foresta E., 1990. Origine et évolution des savanes intramayombiennes (R.P. du Congo). II. Apport de la botanique forestière. In: Lanfranchi et Schwartz éds.: Paysages quaternaires de l’Afrique centrale atlantique. Didactiques ORSTOM, Paris: 326–335. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282167401

- Demichelis, Christophe; Oszwald, J., Bostvironois, A., Gasquet-Blanchard, C., Narat, V. et al. 2021. A century of village mobilities and landscape dynamics in a forest-savannah mosaic, Democratic Republic of Congo. BOIS & FORETS DES TROPIQUES. 348. 3–16. 10.19182/bft2021. 348.a31934.

- Diatta, 1994. Mise en défens et techniques agro forestières au Sine Saloum (Sénégal). Effets sur la conservation de l’eau, du sol, et sur la production primaire. Thèse de doctorat de l’Université Scientifique L. pasteur. (Strasbourg 1). Mention: Géographie physique. 202p. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/39857499.pdf

- Dinard A. 1971. Influence du reboisement sur les ressources en eau en Afrique du sud. Chronique internationale, R.F.F. XXIII—3: 401–406. https://hal.science/hal-03395042/document

- Djenontin, I.N.S., Zulu, L.C., Richardson, R.B. Smallholder farmers and forest landscape restoration in sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from Central Malawi. 2022. Land Use Policy, Volume 122, 106345, ISSN 0264-8377, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106345.

- Estes L. D., Searchinger T., Spiegel M., Tian D., Sichinga S., Mwale M., Kehoe L., Kuemmerle T., Berven A., Chaney N., Sheffield J., Wood E. F. and Caylor K. K. 2016. Reconciling agriculture, carbon and biodiversity in a savannah transformation frontierPhil. Trans. R. Soc. B3712015031620150316. http://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0316

- Gautier L., 1983. Contact forêt-savane en Côte-d’Ivoire centrale: évolution de la surface forestière de la réserve de Lamto (sud du V-Baoulé). Bull. Soc. But. Fr., 136 (315): 85–92. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271931840

- Hemp, A. 1999. An ethnobotanical study on Mt. Kilimanjaro. Ecotropica 5: 147–165. https://www.soctropecol.eu/publications/pdf/5-2/Hemp%20A%201999,%20Ecotropica%205_5_147-165.pdf

- Hopkins B., 1992. Ecological processes at the forest-savanna boundary. pp. 21–34. In: Furley, P., Ratter, J., Proctor, J. (eds.) Nature and dynamics of forest-savanna boundaries. Chapman & Hall, London. pp. 21–33. DOI:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2012.01789.x

- Kaonga LM et Bayliss-Smith PT., 2012. Simulation of carbon pool changes in woodlots in eastern Zambia using the CO2FIX model Agroforestry Systems, Springer. 86: 213–223. DOI:10.1007/s10457-011-9429-9

- Koechlin J., 1961. La végétation des savanes dans le sud de la République du Congo. (21): 427–438. Mém. 1.R.S-Congo 10, ORSTOM, Paris, 310 p. https://horizon.documentation.ird.fr/exl-doc/pleins_textes/divers14-07/15020.pdf

- Kooke, G.X, Kolawolé Foumilayo M. A. R., Djossou J.M. et Toko Imorou I. 2019. Estimation du stock de carbone organique dans les plantations d’Acacia auriculiformis A. Cunn. ex Benth. des forêts classées de Pahou et de Ouèdo au Sud du Bénin. International Journal of Biological and Chemical Sciences: 13(1): 277–293. DOI:10.4314/ijbcs.v13i1.23

- Lubalega, T.K., C. Lubini, J.C Ruel, D. P. Khasa, J. Ndembo and J. Lejoly. 2016. Structure and floristic composition of shrub savannas in a fire-protected system, in Ibi, Plateau des Bateke, in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Scientific and technical review Forest and Environment of the Congo Basin 9: 20–30. https://www.ijerd.com/paper/vol13-issue9/Version-4/E130942130.pdf

- Maloti Ma Songo, J.M. 2010. Evaluation du processus de la régénération naturelle dans la savane mise en défens à MANZONZI, MAO, villages riverains de la Réserve de Biosphère de LUKI, WWF/Bas-Congo. 53p. https://www.memoireonline.com/11/19/11261/

- Mietton M., 1988. Dynamique de l’influence lithosphère-atmosphère au Burkina Faso. L’érosion en zone de savane. Thèse de doctorat Géographie., université de Grenoble, 511p. https://www.persee.fr/doc/rga_0035-1121_1988_num_76_3_2716_t1_0311_0000_1

- Mills, A. J. and Cowling, R.M. 2006. Rate of Carbon Sequestration at Two Thicket Restoration Sites in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Restoration Ecology, Volume 14, Issue 1 p. 38–49. https://doi-org.acces.bibl.ulaval.ca/10.1111/j.1526-100X.2006.00103.x

- Nzigidahera, B., Njebarikanuye, A., Kakunze, A. C., & Misigago, A. 2008. Etude préliminaire d’identification des milieux naturels à mettre en defens dans la depression de Kumoso. Institut National pour l’Environnement et la Conservation de la Nature (INECN), Gitega, Burundi. https://bi.chm-cbd.net/fr/implementation/documents-envir-biodiv/etud-prel-ident-mil-nat-defens-kumoso

- Peltier, R., Dubiez, E., Diowo, S., Gigaud, M., Marien, J.-N., Marquant, B., Peroches, A., Proces, P., & Vermeulen, C. 2014. Assisted natural regeneration adapted to slash-and-burn agriculture: results in the democratic republic of congo. Bois & forets des tropiques, 321(321), 67–79. https://doi.org/10.19182/bft2014.321.a31220

- Pfeifer M., Sallu S.M., Marshall A.R., Rushton S., Moore E., Shirima D.D., Smit J., Kioko E., Barnes L., Waite C., Raes L., Braunholtz L., Olivier P.I., Ishengoma E., Bowers S. and Guerreiro-Milheiras S. 2023. A systems approach framework for evaluating tree restoration interventions for social and ecological outcomes in rural tropical landscapesPhil. Trans. R. Soc. B3782021011120210111. http://doi.org.acces.bibl.ulaval.ca/10.1098/rstb.2021.0111

- Pillay, V. & Moodley, B. 2022. Assessment of the impact of reforestation on soil, riparian sediment and river water quality based on polyaromatic hydrocarbon pollutants, Journal of Environmental Management, Volume 324, 116331, ISSN 0301-4797, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.116331.

- Rinaudo T. 1999. Utilising the Underground Forest: Farmer Managed Natural Regeneration of Trees, in Dov Pasternak and Arnold Schlissel (Eds). Combating Desrtification with Plants. DOI:10.1007/978-1-4615-1327-8_31

- Sacande, M., Berrahmouni, N. et Hargreaves, S. 2015. La participation communautaire au cœur du modèle de restauration de la Grande muraille verte africaine. UNASYLVA, 66 (3): 44–51. https://www.fao.org/3/i5212f/i5212f.pdf

- Some, Y. S. C., Akaffou, M. Y. F. et Kaguembega, F. 2011. Évaluation de la restauration de la biodiversité dans les écosystèmes fragiles: cas des mises en défens de newTree Burkina. Institut International d’Ingénierie de l’Eau et de l’Environnement, Burkina. https://newtree.org/fr/projet/burkina-faso/

- Swaine M.D., Hall J.B., Lock J.M. 1976. The forest-savanna boundary in West- Central Ghana. Ghana Journal of Sciences, 16 (1): 35–52. DOI: 10.1098/rstb.2021.0081

- Valette, M.; Vinceti, B.; Traoré, D.; Traoré, A.T.; Yago-Ouattara, E.L.; Kaguembèga-Müller, F. 2019. How Diverse is Tree Planting in the Central Plateau of Burkina Faso? Comparing Small-Scale Restoration with Other Planting Initiatives. Forests, 10, 227. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10030227

- Van Rooyen, M.W., Van Rooyen, Stoffberg, G.H. Carbon sequestration potential of post-mining reforestation activities on the KwaZulu-Natal coast, South Africa. 2013. Forestry: An International Journal of Forest Research, Volume 86, Issue 2, April 2013, Pages 211–223, https://doi-org.acces.bibl.ulaval.ca/10.1093/forestry/cps070

- Vinceti, B., Fremout, T., Termote, C., Conejo, D.F., Thomas, E., Carl Lachat, C., Toe, L.C., Thiombiano, A., Zerbo, I., Lompo, D., Sanou, L., Parkouda, C., Hien, A., Oumarou Ouédraogo O., Ouoba, H. 2022. Food tree species selection for nutrition-sensitive forest landscape restoration in Burkina Faso. https://doi-org.acces.bibl.ulaval.ca/10.1002/ppp3.10304

- Vuattoux R., 1970—Observations sur l’évolution des strates arborée et arbustive dans la savane de Lamto (Côte-d’Ivoire). Ann. Univ. Abidjan, 3: 285–315. https://hal.science/hal-00360823v1/document

- Wessels, K.J & Mathieu, R., Erasmus, BFN; Asner, GP., Smit, I.P.J et al. 2011. Impact of communal land use and conservation on woody vegetation structure in the Lowveld savannas of South Africa—Lidar results. Forest ecology and management. Volume 261 Issue1 Page19–29. DOI10.1016/j.foreco.2010.09.01

- Youta, H.J, 1998 Arbres contre graminées: la lente invasion de la savane par la forêt au Centre-Cameroun. Thèse de doct. Université de Paris-Sorbonne (PARIS IV). Biogéographie. https://www.theses.fr/1998PA040022

Appendix B. Variables Such as ESs Cited, Forest Restoration Modalities, Activities Related to ES Use, ES Use Values, and Study Location, with the Subcategories of ESs Used for MCA

| Ecosystem Services | ES Categories | Modality of FLR | Use Value | Sub-Regio in Africa |

| Food | Provisioning | Reforestation | Direct | Central Africa |

| Food | Provisioning | Reforestation | Direct | East Africa |

| Food | Provisioning | Agroforestry | Direct | East Africa |

| Food | Provisioning | Agroforestry | Direct | West Africa |

| Food | Provisioning | Agroforestry | Direct | Southern Africa |

| Food | Provisioning | Agroforestry | Direct | West Africa |

| Food | Provisioning | Agroforestry | Direct | East Africa |

| Food | Provisioning | Agroforestry | Direct | West Africa |

| Food | Provisioning | Reforestation | Direct | West Africa |

| Food | Provisioning | Agroforestry | Direct | West Africa |

| Food | Provisioning | Reforestation | Direct | East Africa |

| Food | Provisioning | Reforestation | Direct | West Africa |

| Timber | Provisioning | Savannah protection | Direct | West Africa |

| Timber | Provisioning | Savannah protection | Direct | West Africa |

| Timber | Provisioning | Savannah protection | Direct | West Africa |

| Timber | Provisioning | Agroforestry | Direct | West Africa |

| Timber | Provisioning | Savannah protection | Direct | West Africa |

| Timber | Provisioning | Reforestation | Direct | East Africa |

| Timber | Provisioning | Reforestation | Direct | West Africa |

| Timber | Provisioning | Agroforestry | Direct | Southern Africa |

| Medicinal plants | Provisioning | Reforestation | Direct | West Africa |

| Firewood | Provisioning | Agroforestry | Direct | West Africa |

| Firewood | Provisioning | Agroforestry | Direct | West Africa |

| Firewood | Provisioning | Reforestation | Direct | East Africa |

| Firewood | Provisioning | Reforestation | Direct | West Africa |

| Firewood | Provisioning | Agroforestry | Direct | Southern Africa |

| Fresh water | Provisioning | Reforestation | Direct | Southern Africa |

| PESFM | Regulating | Savannah protection | Indirect | West Africa |

| PESFM | Regulating | Savannah protection | Indirect | West Africa |

| PESFM | Regulating | Reforestation | Indirect | East Africa |

| PESFM | Regulating | Savannah protection | Indirect | West Africa |

| Carbon stock | Regulating | Reforestation | Indirect | Southern Africa |

| Carbon stock | Regulating | Reforestation | Indirect | Southern Africa |

| Carbon stock | Regulating | Reforestation | Indirect | Southern Africa |

| Carbon stock | Regulating | Reforestation | Indirect | East Africa |

| Carbon stock | Regulating | Reforestation | Indirect | Central Africa |

| Carbon stock | Regulating | Savannah protection | Indirect | Central Africa |

| Carbon stock | Regulating | Savannah protection | Indirect | Southern Africa |

| Carbon stock | Regulating | Reforestation | Indirect | West Africa |

| Primary productivity | Supporting | Savannah protection | Indirect | Central Africa |

| Primary productivity | Supporting | Savannah protection | Indirect | Central Africa |

| Primary productivity | Supporting | Savannah protection | Indirect | Central Africa |

| Primary productivity | Supporting | Savannah protection | Indirect | Central Africa |

| Primary productivity | Supporting | Savannah protection | Indirect | West Africa |

| Primary productivity | Supporting | Savannah protection | Indirect | West Africa |

| Primary productivity | Supporting | Savannah protection | Indirect | East Africa |

| Primary productivity | Supporting | Savannah protection | Indirect | East Africa |

| Primary productivity | Supporting | Savannah protection | Indirect | Central Africa |

| Primary productivity | Supporting | Savannah protection | Indirect | West Africa |

| Primary productivity | Supporting | Savannah protection | Indirect | West Africa |

| Primary productivity | Supporting | Savannah protection | Indirect | Maghreb |

| Primary productivity | Supporting | Agroforestry | Indirect | Maghreb |

| Primary productivity | Supporting | Savannah protection | Indirect | West Africa |

| Primary productivity | Supporting | Savannah protection | Indirect | West Africa |

| Primary productivity | Supporting | Reforestation | Indirect | Central Africa |

| Primary productivity | Supporting | Savannah protection | Indirect | Central Africa |

| Primary productivity | Supporting | Savannah protection | Indirect | Southern Africa |

| Primary productivity | Supporting | Reforestation | Indirect | West Africa |

| Primary productivity | Supporting | Savannah protection | Indirect | Central Africa |

| Primary productivity | Supporting | Agroforestry | Indirect | West Africa |

| Primary productivity | Supporting | Savannah protection | Indirect | East Africa |

| Primary productivity | Supporting | Savannah protection | Indirect | West Africa |

References

- FAO. Évaluation des Ressources Forestières Mondiales: Rapport Principal. Rome. 2020. 2021. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/ca9825fr (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Nsimba, N.E.; Luete, L.E.; Mbambi, K.; Lumbuenamo, S.R. Cartographie participative: Outil de diagnostic pour une gestion durable des ressources forestières «Cas du village Mbenza-Wadiau, Kongo central en République Démocratique du Congo». Rev. Afr. Environ. Agric. 2020, 3, 37–46. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/362888985 (accessed on 4 September 2022).

- Eba’a Atyi, R.; Hiol Hiol, F.; Lescuyer, G.; Mayaux, P.; Defourny, P.; Bayol, N.; Saracco, F.; Pokem, D.; Sufo Kankeu, R.; Nasi, R. Congo Basin Forests; State of the Forests CIFOR: Bogor, Indonesia, 2021; Available online: https://www.cifor.org/knowledge/publication/8700/ (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Bogaert, J.; Colinet, G.; Mahy, G. Anthropisation des Paysages Katangais; Presses Universitaires de Liège—Agronomie-Gembloux: Gembloux, Belgique, 2018; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333004419_Anthropisation_des_paysages_katangais (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Stoeckl, N.; Jarvis, D.; Larson, S.; Larson, A.; Grainger, D.; Ewamian Aboriginal Corp. Australian Indigenous insights into ecosystem services: Beyond services towards connectedness—People, place and time. Ecosyst. Serv. 2021, 50, 101341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wasseige, C.; Tadoum, M.; Eba’a-Atyi, R.; Doumenge, C. (Eds.) The Forests of the Congo Basin: Forests and Climate Change; Weyrich: Neufchâteau, Belgium, 2015; 128p, Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285593726 (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- IUCN and WRI (World Resources Institute). A Guide to the Restoration Opportunities Assessment Methodology (ROAM): Assessing Forest Landscape Restoration Opportunities at the National or Sub-National Level; Working Paper (Road-Test Edition); International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN): Gland, Switzerland, 2014; 125p, Available online: https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/2014-030.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Laestadius, L.; Maginnis, S.; Minnemeyer, S.; Potapov, P.; Saint-Laurent, C.; Sizer, N. Carte des opportunités de restauration des paysages forestiers. Unasylva 2011, 238, 62. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i2560f/i2560f08.pdf (accessed on 7 December 2015).

- Owusu, R.; Kimengsi, J.N.; Moyo, F. Community-based Forest Landscape Restoration (FLR): Determinants and policy implications in Tanzania. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, A.R.; Waite, C.E.; Pfeifer, M.; Banin, L.F.; Rakotonarivo, S.; Chomba, S.; Herbohn, J.; Gilmour, D.A.; Brown, M.; Chazdon, R.L. Fifteen essential science advances needed for effective restoration of the world’s forest landscapes. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2023, 378, 20210065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besseau, P.; Graham, S.; Christophersen, T. (Eds.) Restaurer les Paysages Forestiers: La Clé d’un Avenir Durable (Restoring Forests and Landscapes: The Key to a Sustainable Future); Partenariat Mondial pour la Restauration des Paysages Forestiers (The Global Partnership on Forest and Landscape Restoration): Vienne, Austria, 2018; Available online: https://rifm.net/wp-content/uploads//2020/02/GPFLR_french_final_.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Rapiya, M.; Truter, W.; Ramoelo, A. The integration of land restoration and biodiversity conservation practices in sustainable food systems of Africa: A systematic review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, S.; Aronson, J.; Whaley, O.; Lamb, D. The relationship between ecological restoration and the ecosystem services concept. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmann, J.; Meyer, S.T.; Bateman, R.; Conradi, T.; Gossner, M.M.; Mendonca, M., Jr.; Fernandes, G.W.; Hermann, J.-M.; Koch, C.; Müller, S.C.; et al. Integrating ecosystem functions into restoration ecology—Recent advances and futures directions: Ecosystem functions in restoration ecology. Restor. Ecol. 2016, 24, 722–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TEEB. The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity. In Ecological and Economic Foundations; Kumar, P., Ed.; Earthscan: London, UK; Washington, DC, USA, 2010; Available online: http://www.biodiversity.ru/programs/international/teeb/materials_teeb/TEEB_SynthReport_English.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- César, R.G.; Belei, L.; Badari, C.G.; Viani, R.A.G.; Gutierrez, V.; Chazdon, R.L.; Brancalion, P.H.S.; Morsello, C. Forest and Landscape Restoration: A Review Emphasizing Principles, Concepts, and Practices. Land 2021, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buthelezi, M.N.M.; Lottering, R.T.; Peerbhay, K.Y.; Mutanga, O. Exploring forest rehabilitation and restoration: A brief systematic review. Trees For. People 2025, 20, 100898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, C.J.; Turner, E.C.; Blonder, B.W.; Bongalov, B.; Both, S.; Cruz, R.S.; Elias, D.M.O.; Hemprich-Bennett, D.; Jotan, P.; Kemp, V.; et al. Tropical forest clearance impacts biodiversity and function, whereas logging changes structure. Science 2025, 387, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansuy, N.; Hwang, H.; Gupta, R.; Mooney, C.; Kishchuk, B.; Higgs, E. Forest Landscape Restoration Legislation and Policy: A Canadian Perspective. Land 2022, 11, 1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangai, P.W.; Burkhard, B.; Müller, F. A review of studies on ecosystem services in Africa. Int. J. Sustain. Built Environ. 2016, 5, 225–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengist, W.; Soromessa, T.; Feyisa, G.L. A global view of regulatory ecosystem services: Existed knowledge, trends, and research gaps. Ecol. Process. 2020, 9, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wei, F.; Tagesson, T.; Fang, Z.; Svenning, J.C. Transforming forest management through rewilding: Enhancing biodiversity, resilience, and biosphere sustainability under global change. One Earth 2025, 8, 101195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Hoff, R.; Nascimento, N.; Fabrício-Neto, A.; Jaramillo-Giraldo, C.; Ambrosio, G.; Arieira, J.; Afonso Nobre, C.; Rajão, R. Policy-oriented ecosystem services research on tropical forests in South America: A systematic literature review. Ecosyst. Serv. 2022, 56, 101437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinauskas, M.; Shuhani, Y.; Valença Pinto, L.; Inácio, M.; Pereira, P. Mapping ecosystem services in protected areas. A Syst. Rev. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djenontin, I.N.S.; Foli, S.; Zulu, L.C. Revisiting the Factors Shaping Outcomes for Forest and Landscape Restoration in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Way Forward for Policy, Practice and Research. Sustainability 2018, 10, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MEA (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment). Ecosystems and Human Well-Being; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; Available online: https://www.millenniumassessment.org/fr/index.html (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Lubalega, T.K.; Lubini, C.; Ruel, J.-C.; Khasa, D.P.; Ndembo, J.; Lejoly, J. Structure and floristic composition of shrub savannas in a fire-protected system, in Ibi, Plateau des Bateke, in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Sci. Tech. Rev. For. Environ. Congo Basin 2016, 9, 20–30. Available online: https://www.ijerd.com/paper/vol13-issue9/Version-4/E130942130.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Samb, T.; Ababacar, C.; Baila, N.A. Les attaques des Termites (Isoptera) dans les parcelles de reboisement de la Grande Muraille Verte au Sénégal. J. Appl. Biosci. 2016, 104, 9947–9954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICRAF (World Agroforestry Centre). Creating an Evergreen Agriculture in Africa for Food Security and Environmental Resilience; World Agroforestry Centre: Nairobi, Kenya, 2009; p. 24. Available online: https://apps.worldagroforestry.org/downloads/publications/pdfs/B09008.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Shutaywi, M.; Kachouie, N.N. Silhouette Analysis for Performance Evaluation in Machine Learning with Applications to Clustering. Entropy 2021, 23, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djenontin, I.N.S.; Zulu, L.C.; Etongo, D. Ultimately, What is Forest Landscape Restoration in Practice? Embodiments in Sub-Saharan Africa and Implications for Future Design. Env. Manag. 2021, 68, 619–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sambou, A.; Camara, B.; Goudiaby, A.O.K.; Coly, A.; Badji, A. Perception des Populations Locales sur les Services Écosystèmiques de la Forêt Classée et Aménagée de Kalounayes (Sénégal). Revue Francophone du Développement Durable, Hors-Série n°6, 69–86. 2018. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/337908007 (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Moloise, S.D.; Matamanda, A.R.; Bhanye, J. Traditional ecological knowledge and practices for ecosystem conservation and management: The case of savanna ecosystem services in Limpopo, South Africa. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2024, 31, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felipe-Lucia, M.R.; de Frutos, A.; Crouzat, E.; Grescho, V.; Heuschele, J.M.; Marselle, M.; Heurich, M.; Pöpperl, F.; Porst, F.; Portela, A.P.; et al. Differences in the experience of cultural ecosystem services in mountain protected areas by clusters of visitors. Ecosyst. Serv. 2024, 70, 101663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, C.A.; Jones, M.E.; Bustamante, E.; Zambrano, C.; Carrión-Klier, C.; Jäger, H. Setting Up Roots: Opportunities for Biocultural Restoration in Recently Inhabited Settings. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirwa, P.W. Pratiques de Restauration dans les Zones Dégradées d’Afrique de l’Est; Working Paper Series; African Forest Forum: Nairobi, Kenya, 2014; Volume 2, 63p, Available online: https://afforum.org/cgi-sys/suspendedpage.cgi (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Youta, H.J. Arbres Contre Graminées: La Lente Invasion de la Savane par la Forêt au Centre-Cameroun. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Paris-Sorbonne, Paris, France, 1998. Available online: https://www.theses.fr/1998PA040022 (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Djenontin, I.N.S.; Zulu, L.C.; Richardson, R.B. Smallholder farmers and forest landscape restoration in sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from Central Malawi. Land Use Policy 2022, 122, 106345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemp, A. An ethnobotanical study on Mt. Kilimanjaro. Ecotropica 1999, 5, 147–165. Available online: https://www.soctropecol.eu/publications/pdf/5-2/Hemp%20A%201999,%20Ecotropica%205_5_147-165.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Rinaudo, T. Utilizing the underground forest: Farmer managed natural regeneration of trees. In Combating Desertification with Plants; Pasternak, D., Schlissel, A., Eds.; Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 325–336. [Google Scholar]

- Vinceti, B.; Fremout, T.; Termote, C.; Conejo, D.F.; Thomas, E.; Lachat, C.; Toe, L.C.; Thiombiano, A.; Zerbo, I.; Lompo, D.; et al. Food tree species selection for nutrition-sensitive forest landscape restoration in Burkina Faso. Plants People Planet 2022, 4, 667–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffa, J.M. Agroforestry Parklands in Sub-Saharan Africa. Conservation Guide 34. FAO. 1999. Available online: http://www.fao.org/docrep/005/x3940e/X3940E10.htm#ch7.4 (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Sacande, M.; Berrahmouni, N.; Hargreaves, S. La participation communautaire au cœur du modèle de restauration de la Grande muraille verte africaine. Unasylva 2015, 66, 44–51. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i5212f/i5212f.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Vuattoux, R. Observations sur l’évolution des strates arborée et arbustive dans la savane de Lamto (Côte-d’Ivoire). Ann. Univ. Abidj. 1970, 3, 285–315. Available online: https://hal.science/hal-00360823v1/document (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Gautier, L. Contact forêt-savane en Côte-d’Ivoire centrale: évolution de la surface forestière de la réserve de Lamto (sud du V-Baoulé). Bull. Soc. Bot. Fr. 1983, 136, 85–92. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271931840 (accessed on 11 January 2022). [CrossRef]

- Dauget, J.M.; Menaut, J.C. Evolution sur 20 ans d’une parcelle de savane boisée non protégéé du feu dans la réserve de Lamto (Côte-d’Ivoire). Candollea 1992, 47, 621–630. Available online: https://www.e-periodica.ch/cntmng?pid=can-002%3A1992%3A47%3A%3A812 (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Dinard, A. Influence du reboisement sur les ressources en eau en Afrique du Sud. Rev. For. Française 1971, 23, 401–406. Available online: https://hal.science/hal-03395042/document (accessed on 11 January 2022). [CrossRef]

- Diatta, M. Mise en Défens et Techniques Agroforestières au Sine Saloum (Sénégal). Effets sur la Conservation de l’eau, du sol, et sur la Production Primaire. Ph.D. Thesis, l’Université Scientifique L. Pasteur (Strasbourg 1), Strasbourg, France, 1994; 202p. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/39857499.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Mietton, M. Dynamique de L’influence Lithosphère-Atmosphère au Burkina Faso. L’érosion en Zone de Savane. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Grenoble, Saint-Martin-d’Hères, France, 1988; 511p. Available online: https://www.persee.fr/doc/rga_0035-1121_1988_num_76_3_2716_t1_0311_0000_1 (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Pillay, V.; Moodley, B. Assessment of the impact of reforestation on soil, riparian sediment and river water quality based on polyaromatic hydrocarbon pollutants. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 324, 116331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooke, G.X.; Kolawolé Foumilayo, M.A.R.; Djossou, J.M.; Toko Imorou, I. Estimation du stock de carbone organique dans les plantations d’Acacia auriculiformis A. Cunn. ex Benth. des forêts classées de Pahou et de Ouèdo au Sud du Bénin. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2019, 13, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estes, L.D.; Searchinger, T.; Spiegel, M.; Tian, D.; Sichinga, S.; Mwale, M.; Kehoe, L.; Kuemmerle, T.; Berven, A.; Chaney, N.; et al. Reconciling agriculture, carbon and biodiversity in a savannah transformation frontier. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2016, 371, 20150316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaonga, L.M.; Bayliss-Smith, P.T. Simulation of carbon pool changes in woodlots in eastern Zambia using the CO2FIX model. Agrofor. Syst. 2012, 86, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, A.J.; Cowling, R.M. Rate of Carbon Sequestration at Two Thicket Restoration Sites in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Restor. Ecol. 2006, 14, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rooyen, M.W.; Stoffberg, G.H. Carbon sequestration potential of post-mining reforestation activities on the Kwa-Zulu-Natal coast, South Africa. Forestry 2013, 86, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltier, R.; Dubiez, E.; Diowo, S.; Gigaud, M.; Marien, J.-N.; Marquant, B.; Peroches, A.; Proces, P.; Vermeulen, C. Assisted natural regeneration adapted to slash-and-burn agriculture: Results in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Bois For. Trop. 2014, 321, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, M.; Sallu, S.M.; Marshall, A.R.; Rushton, S.; Moore, E.; Shirima, D.D.; Smit, J.; Kioko, E.; Barnes, L.; Waite, C.; et al. A systems approach framework for evaluating tree restoration interventions for social and ecological outcomes in rural tropical landscapes. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2023, 378, 20210111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valette, M.; Vinceti, B.; Traoré, D.; Traoré, A.T.; Yago-Ouattara, E.L.; Kaguembèga-Müller, F. How diverse is tree planting in the Central Plateau of Burkina Faso? Comparing small-scale restoration with other planting initiatives. Forests 2019, 10, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badji, M.; Sanogo, D.; Akpo, L.E. Effet de l’âge de la mise en défens sur la reconstitution de la végétation ligneuse des espaces sylvo pastoraux du sud bassin arachidier (Sénégal). J. Appl. Biosci. 2013, 64, 4876–4887. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272341752 (accessed on 11 January 2022). [CrossRef]

- Demichelis, C.; Oszwald, J.; Bostvironois, A.; Gasquet-Blanchard, C.; Narat, V.; Bokika, J.-C.; Giles-Vernick, T. A century of village mobilities and landscape dynamics in a forest-savannah mosaic, Democratic Republic of Congo. Bois Forêts Trop. 2021, 348, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koechlin, J. La Végétation des Savanes dans le Sud de la République du Congo; Institut de Recherches Scientifiques au Congo: Brazzaville, Congo; Orstom: Paris, France, 1961; 310p. Available online: https://horizon.documentation.ird.fr/exl-doc/pleins_textes/divers14-07/15020.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- De Foresta, E. Origine et évolution des savanes intramayombiennes (R.P. du Congo). II. Apport de la botanique fores-tière. In Paysages Quaternaires de l’Afrique Centrale Atlantique; Lanfranchi, R., Schwartz, D., Eds.; Editions de l’ORSTOM: Paris, France, 1990; pp. 326–335. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282167401 (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Swaine, M.D.; Hall, J.B.; Lock, J.M. The forest-savanna boundary in West-Central Ghana. Ghana J. Sci. 1976, 16, 35–52. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/i313528 (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Boulvert, Y. Avancée ou recul de la forêt centrafricaine. Changements climatiques, influence de l’homme et notamment des feux. In Paysages Quatemaires de 1’Afrique Centrale Atlantique; Lanfranchi, R., Schwartz, D., Eds.; Editions de l’ORSTOM: Paris, France, 1990; pp. 353–366. Available online: https://horizon.documentation.ird.fr/exl-doc/pleins_textes/divers11-10/34798.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Hopkins, B. Ecological processes at the forest-savanna boundary: How plant traits, resources and fire govern the distribution of tropical biomes. In Nature and Dynamics of Forest-Savanna Boundaries; Furley, P., Ratter, J., Proctor, J., Eds.; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1992; pp. 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzigidahera, B.; Njebarikanuye, A.; Kakunze, A.C.; Misigago, A. Etude Préliminaire D’identification des Milieux Naturels à Mettre en Defens dans la Depression de Kumoso; Institut National pour l’Environnement et la Conservation de la Nature (INECN): Gitega, Burundi, 2008; Available online: https://bi.chm-cbd.net/fr/implementation/documents-envir-biodiv/etud-prel-ident-mil-nat-defens-kumoso (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Aerts, R.; November, E.; Maes, W.; Van der Borght, I.; Negussie, A.; Aynekulu, E.; Hermy, M.; Muys, B. In situ per-sistence of African wild olive and forest restoration in degraded semiarid savanna. J. Arid Environ. 2008, 72, 1131–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloti Ma Songo, J.M. Evaluation du Processus de la Régénération Naturelle dans la Savane Mise en Défens à Manzoni, MAO, Villages Riverains de la Réserve de Biosphère de Luki; ERPU-GDFI: Kisangani, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2010; 53p. [Google Scholar]

- Some, Y.S.C.; Akaffou, M.Y.F.; Kaguembega, F. Évaluation de la Restauration de la Biodiversité dans les Écosys-Tèmes Fragiles: Cas des Mises en Défens de Newtree Burkina; Institut International d’Ingénierie de l’Eau et de l’Environnement: Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 2011; Available online: https://newtree.org/fr/projet/burkina-faso/ (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Benaradj, A.; Boucherit, H.; Mederbal, K.; Benabdeli, K.; Baghdadi, D. Effect the exclosure on plant diversity of the Hammada scoparia steppe in the Naama steppe courses (Algeria). J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2011, 2, 564–571. Available online: https://www.jmaterenvironsci.com/Document/vol2/vol2_S1/27-JMES-S1-19-2011%20benaradj-T6.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Achour, A.; Aroula, A.; Defaa, C.; El Mousadika, A.; Msanda, F. Effet de la Mise en Défens sur la Richesse Floristique et la Densité dans deux Arganeraies de Plaine; Actes du Premier Congrès International de l’Arganier: Agadir, Maroc, 2011; pp. 60–69. Available online: http://webagris.inra.org.ma/doc/ouvrages/arganier2011/arganier060069.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Badji, M.; Sanogo, D.; Akpo, L. Dynamique de la vegetation ligneuse des espaces sylvopastoraux villageois mis en defens dans le Sud du Bassin arachidier au Senegal. Bois Forêts Trop. 2014, 319, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boakye, E.A.; Gils, H.V.; Osei, E.M.J.; Asare, V.N.A. Does forest restoration using taungya foster tree species diversity? The case of Afram Headwaters Forest Reserve in Ghana. Afr. J. Ecol. 2012, 50, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, J.; Herbohn, J.; Moreno, M.O.M.; Avela, M.S.; Firn, J. Next-generation tropical forests: Reforestation type affects recruitment of species and functional diversity in a human-dominated landscape. J. Appl. Ecol. 2017, 54, 772–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indrajaya, Y.; Yuwati, T.W.; Lestari, S.; Winarno, B.; Narendra, B.H.; Nugroho, H.Y.S.H.; Rachmanadi, D.; Pratiwi; Turjaman, M.; Adi, R.N.; et al. Tropical forest landscape restoration in Indonesia: A review. Land 2022, 11, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyathi, N.A.; Musakwa, W.; Azilagbetor, D.M.; Kuhn, N.J. Perceptions of cultural and provisioning ecosystem services and human wellbeing indicators amongst indigenous communities neighbouring the greater limpopo transfrontier conserva-tion area. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romanazzi, G.R.; Koto, R.; De Boni, A.; Palmisano, G.O.; Cioffi, M.; Roma, R. Cultural ecosystem services: A review of methods and tools for economic evaluation. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2023, 20, 100304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagiola, S.; Ramírez, E.; Gobbi, J.; de Haan, C.; Ibrahim, M.; Murgueitio, E.; Ruíz, J.P. Paying for the environmental services of silvopastoral practices in Nicaragua. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 64, 374–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, N.T.; Benedikter, S.; Kapp, G. A value chain approach to forest landscape restoration: Insights from Vietnam’s production-driven forest restoration. For. Soc. 2022, 6, 311–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, C.M. Ecosystem Provisioning Services in Global South Cities. In Urban Ecology in the Global South. Cities and Nature; Shackleton, C.M., Cilliers, S.S., Davoren, E., du Toit, M.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyumah, D.S.; Brambilla, M. Balancing habitat conservation and community livelihoods: An evaluation of communi-ty-based wetlands management in the Lake Piso multiple-use nature reserve. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 386, 125740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, M.S.; Goodale, U.M.; Bawa, K.S.; Ashton, P.S.; Neidel, J.D. Restoring working forests in human dominated landscapes of tropical South Asia: An introduction. For. Ecol. Manag. 2014, 329, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.K.; Sánchez, A.C.; Beillouin, D.; Juventia, S.D.; Mosnier, A.; Remans, R.; Carmona, N.E. Achieving win-win outcomes for biodiversity and yield through diversified farming. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2023, 67, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipi, E.; Mukenza, M.; Sikuzani, Y.; Ndzomo, J.; Kouagou, R.; Malaisse, F.; Kasali, J.; Khasa, D.; Bogaert, J. Diversity and availability of edible caterpillar host plants in the Luki Biosphere Reserve land-scape in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Trees For. People 2024, 18, 100719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, F.; Liu, M.; Wang, Z. Integrating forest restoration into land-use planning at large spatial scales. Curr. Biol. 2024, 34, R452–R472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachmat, H.H.; Ginoga, K.L.; Lisnawati, Y.; Hidayat, A.; Imanuddin, R.; Fambayun, R.A.; Yulita, K.S.; Susilowati, A. Generating multifunctional landscape through reforestation with native trees in the tropical region: A case study of Gunung Dahu Research Forest, Bogor, Indonesia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daouda, G.O.; Madaki, M.Y.; Ousmane, L.M.; Zounon, C.S.F.; Ullah, A.; Bavorova, M.; Verner, V. Non-Timber Forest Products and Community Well-Being: The Impact of a Landscape Restoration Programme in Maradi Region, Niger. Land 2025, 14, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.H.; Roy, B.; Chowdhury, G.M.; Hasan, A.; Saimun, M.S.R. Medicinal plant sources and traditional healthcare practices of forest-dependent communities in and around Chunati Wildlife Sanctuary in southeastern Bangladesh. Environ. Sustain. 2022, 5, 207–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agbodjento, E.; Lègba, B.; Dougnon, V.T.; Klotoé, J.R.; Déguénon, E.; Assogba, P.; Koudokpon, H.; Hanski, L.; Baba-Moussa, L.; Yayi Ladékan, E. Unleashing the Potential of Medicinal Plants in Benin: Assessing the Status of Research and the Need for Enhanced Practices. Plants 2023, 12, 1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diemont, S.A.W.; Bohn, J.L.; Donald, D.R.; Kelsen, S.J.; Cheng, K. Comparisons of Mayan Forest management, restora-tion, and conservation. For. Ecol. Manag. 2011, 261, 1696–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plath, M.; Mody, K.; Potvin, C.; Dorn, S. Do multipurpose companion trees affect high value timber trees in a silvopastoral plantation system? Agrofor. Syst. 2011, 81, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braber, B.D.; Hall, C.M.; Rhemtulla, J.M.; Fagan, M.E.; Rasmusssen, L.V. Tree plantations and forest regrowth are linked to poverty reduction in Africa. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desta, H.S. Weaving the Green Thread: Forest and Landscape Restoration and Nature-based-solutions for Achieving the SDGs in Oromia and Former SNNP Regions of Ethiopia. Nat. Based Solut. 2025, 8, 100270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambiar, E.K.S. Small forest growers in tropical landscapes should be embraced as partners for Green-growth: Increase wood supply, restore land, reduce poverty, and mitigate climate change. Trees For. People 2021, 6, 100154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A. Forest Landscape Restoration and Its Impact on Social Cohesion, Ecosystems, and Rural Livelihoods: Lessons Learned from Pakistan. Reg. Environ. Change 2024, 24, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterner, R.W.; Keeler, B.; Polasky, S.; Poudel, R.; Rhude, K.; Rogers, M. Ecosystem services of Earth’s largest freshwater lakes. Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 41, 101046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vári, Á.; Podschun, S.A.; Erős, T.; Hein, T.; Pataki, B.; Iojă, I.C.; Adamescu, C.M.; Gerhardt, A.; Gruber, T.; Dedić, A.; et al. Freshwater systems and ecosystem services: Challenges and chances for cross-fertilization of disciplines. Ambio 2022, 51, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, N.W.; Baillie, B.R.; Bishop, K.; Ferraz, S.; Högbom, L.; Nettles, J. The effects of forest management on water quality. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 522, 120397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa, F.; Crétaux, J.-F.; Grippa, M.; Robert, E.; Trigg, M.; Tshimanga, R.M.; Kitambo, B.; Paris, A.; Carr, A.; Fleischmann, A.S.; et al. Water Resources in Africa under Global Change: Monitoring Surface Waters from Space. Surv. Geophys. 2023, 44, 43–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Vardon, M. Accounting for water-related ecosystem services to provide information for water policy and management: An Australian case study. Ecosyst. Serv. 2024, 69, 101658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drever, C.R.; Long, A.M.; Cook-Patton, S.C.; Celanowicz, E.; Fargione, J.; Fisher, K.; Hounsell, S.; Kurz, W.A.; Mitchell, M.; Robinson, N.; et al. Restoring forest cover at diverse sites across Canada can balance synergies and trade-offs. One Earth 2025, 8, 101177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dommain, R.; Couwenberg, J.; Joosten, H. Hydrological self-regulation of domed peatlands in south-east Asia and consequences for conservation and restoration. Mires Peat 2010, 6, 1–17. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265987647 (accessed on 11 January 2022). [CrossRef]

- Viani, R.A.G.; Braga, D.P.P.; Ribeiro, M.C.; Pereira, P.H.; Brancalion, P.H.S. Synergism between payments for wa-ter-related ecosystem services, ecological restoration, and landscape connectivity within the Atlantic Forest hotspot. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 2018, 11, 1940082918790222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langhans, K.E.; Schmitt, R.J.; Chaplin-Kramer, R.; Anderson, C.B.; Bolaños, C.V.; Cabezas, F.V.; Dirzo, R.; Goldstein, J.A.; Horangic, T.; Granados, C.M.; et al. Modeling multiple ecosystem services and beneficiaries of riparian reforestation in Costa Rica. Ecosyst. Serv. 2022, 57, 101470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Zhu, Y.; Yin, M.; Liu, D. The impact of land use and rainfall patterns on the soil loss of the hillslope. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhong, H.; Guo, H.; Ni, J. Climate impacts on deformation and instability of vegetated slopes. Biogeotechnics 2025, 3, 100139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.P.; Bressiani, D.; Ebling, E.D.; Reichert, J.M. Best management practices to reduce soil erosion and change water balance components in watersheds under grain and dairy production. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2024, 12, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D.P.; Cerullo, G.R.; Chomba, S.; Worthington, T.A.; Balmford, A.P.; Chazdon, R.L.; Harrison, R.D. Upscaling tropical restoration to deliver environmental benefits and socially equitable outcomes. Curr. Biol. 2021, 31, R1326–R1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Li, F. Ecosystem restoration and management based on nature-based solutions in China: Research progress and representative practices. Nat. Based Solut. 2024, 6, 100176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.W.; Sarira, T.V.; Carrasco, L.R.; Chong, K.Y.; Friess, D.A.; Lee, J.S.H.; Taillardat, P.; Worthington, T.A.; Zhang, Y.; Koh, L.P. Economic and social constraints on reforestation for climate mitigation in Southeast Asia. Nat. Clim. Change 2020, 10, 842–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, S.; Byrne, N.M.; Hills, A.P. The culture of healthy living—The international perspective. Prog. Progress. Car-Diovasc. Dis. 2025, 90, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]