Abstract

Land use transformation, the longest-standing human-driven environmental alteration, is a pressing and complex issue that significantly impacts European landscapes and contributes to global environmental change. The urgency to act is reinforced by the European Environment Agency (EEA), which identifies industrial, commercial, and residential development—particularly near major urban centers—as key contributors to land take. As the EU sets a vision for achieving zero net land take by 2050, assessing the readiness and coherence of national legislation becomes critical. This comprehensive study employs a comparative legal analysis across five European countries—Italy, Greece, Poland, France, and Ukraine—examining their laws, strategies, and commitments related to land degradation neutrality. Using a review of national legislation and policy documents, the research identifies systemic patterns, barriers, and opportunities within current legal frameworks. The present study aims to provide valuable insights for policymakers, planners, and academic institutions, fostering a comprehensive understanding of existing gaps, implementation, and inconsistencies in national land use legislation. Among the results, it has become evident that a typical “pathway” between the examined states in terms of the legislative framework on land use–land take is probably a utopia for the time being. The legislations in force, in several cases, are labyrinthine and multifaceted, highlighting the urgent and immediate need for simplification and standardization. The need for this action is further underscored by the fact that, in most cases, land use frameworks are characterized by complementary legislation and ongoing amendments. Ultimately, the research underscores the critical need for harmonized governance and transparent, enforceable policies, particularly in regions where deregulated land use planning persists. The diversity in legislative layers and the decentralized role of the authorities further compounds the complexity, reinforcing the importance of cross-country dialogue and EU-wide coordination in advancing sustainable land use development.

1. Introduction

Land use and land cover are closely related, with land use acting as a catalyst for changes in land cover [1]. Human activities associated with land use significantly impact the characteristics and processes culminating in persistent land cover alterations. Consequently, alterations in land use or unsustainable management practices affect the supply of services, impacting not just individual services but the entire ecosystem [2]. Land use change, defined as the modification of land from one use to another [3], plays a vital role in shaping environmental, socio-economic, and territorial dynamics. These changes—including various transformations such as the intensification of agriculture, reforestation initiatives, and urban expansion—significantly impact ecosystem functions, soil health, biodiversity, and climate regulation, diminishing the benefits provided by the natural ecosystems [4]. Although concepts such as land take, land cover change, and soil sealing are well documented in the literature [4,5,6] there is a critical gap in our knowledge regarding the legal and institutional frameworks that regulate these phenomena across Europe. As the world’s most developed and urbanized continent, Europe has undergone significant land use transformations, primarily driven by urbanization and industrialization, resulting in a steady decline in cropland and a moderate increase in forested areas and pastures [7,8,9]. Mediterranean landscapes are an example, as they have safeguarded a diverse agricultural heritage for many years. However, this has been increasingly compromised by the spread of dispersed and spatially discontinuous urbanization, especially around cities [10].

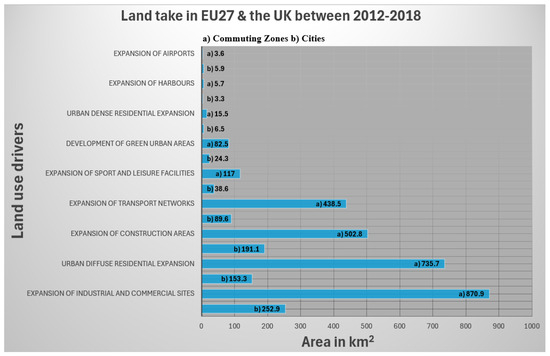

The ongoing trend of urban sprawl, a primary concern for European metropolitan structures and socio-economic activities [11], has significant implications. Urban sprawl and land use transformations have manifested differently across various countries, driven by the localized factors tied to geographical, demographic, and socio-economic conditions, along with the historical, political, and cultural narratives in each area [12]. For instance, the residential sprawl observed in many British and French cities contrasts sharply with the semi-dense, unregulated urbanization patterns in southern Europe and the highly regulated, compact urban models in Eastern European cities [13]. As Europe becomes increasingly susceptible to natural disasters, it is essential to mitigate biodiversity loss, adapt to climate change, and halt land degradation by rehabilitating wetlands, peatlands, coastal ecosystems, forests, grasslands, and agricultural lands. Between 2012 and 2018 (Figure 1), urban areas in the EU-27 and the UK experienced a land take of 3581 km2, accompanied by an estimated increase in soil sealing of 1467 km2, mainly at the expense of croplands and pastures. This soil sealing has resulted in a loss of potential carbon sequestration, quantified at approximately 4.2 million tons of carbon during the observed period. Notably, almost 80% of the land appropriated in urban settings was situated in commuting zones, vital for wildlife habitats, carbon storage, flood mitigation, and food production [14]. Although several studies have examined land take, soil sealing, and spatial planning in Europe, they tend to focus either on individual countries or on environmental outcomes, often neglecting the legal and administrative complexity of national and regional land use systems [15]. Comprehensive cross-country comparisons of land use legislation remain scarce, with most existing analyses limited to subnational levels [16]. This highlights the need for more comprehensive comparative analyses of national land use legislation that can systematically address conceptual distinctions, implementation challenges, and the complexities of fragmented and multi-layered governance structures.

Figure 1.

Land take in the EU-27 and the UK (2012–2018)1.

Such analyses are becoming increasingly relevant in light of evolving EU-level initiatives. EU polices like Soil Strategy 2030 and the revised LULUCF Regulation (EU 2018/841 and EU 2023/839, respectively), aim to enhance climate mitigation by setting GHG removal targets for the land use sector [14]. While the strategies emphasize the need for transparent, sustainable, enforceable, and consistent land governance, the fragmented legal and administrative structures across Member States (MS) hinder the effective implementation and monitoring of carbon-related targets.

From an international perspective, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for 2030, which aim towards climate neutrality, have incorporated Land Degradation Neutrality (LDN) into target 15.3. This target supports other targets, such as SDG target 11.3, which addresses sustainable urban development, and SDG target 15.1, referring to ecosystem conservation and restoration [17]. The notion of LDN was brought into the global discourse to foster a more robust policy response to the challenges of land degradation and, based on UNCCD, 2016, is “a state whereby the amount and quality of land resources necessary to support ecosystem functions and services and enhance food security remain stable or increase within specified temporal and spatial scales and ecosystems” [18]. The pursuit of LDN involves the strategic alignment of actions that include (a) preventing the degradation of healthy land, (b) lessening the degree of land degradation, and (c) restoring or rehabilitating degraded land [19]. Table 1 presents all the relevant EU missions, land degradation strategies, and target commitments.

Table 1.

Missions and targets of the EU for soil health.

Table 1.

Missions and targets of the EU for soil health.

| Source | Targets and Goals |

|---|---|

| EU, 2018/841-Land Use and Forestry Regulation for 2021–20302 | The framework outlines the commitments required of Member States regarding the LULUCF sector, which are integral to meeting the targets set forth by the Paris Agreement and the EU’s GHG emission reduction goals for the 2021–2030 period. It also specifies the guidelines for accounting emissions and removals related to LULUCF practices. |

| Regulation (EU) 2023/839-LULUCF Amendment3 | Amends Regulation 2018/841 and the Governance Regulation 2018/1999, widening scope, simplifying reporting/compliance, and setting updated Member State LULUCF targets for 2030. |

| Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 (EC, 2020c)4 | Chapter 2.2: Commitment to land degradation neutrality through updating soil and built environment strategies and the mission of soil health and food under Horizon Europe. |

| Soil Strategy for 2030 (EC, 2021)5 | Chapter 2: Reach no net land take by 2050. MS should set their own national, regional, and local targets. |

| Mission for Soil Health and Food (EC, 2020d)6 | Objective 3: No net soil sealing and increase the reuse of urban soils for urban development. Target 3.1: Switch from 2.4% to no net soil sealing. Target 3.2: Increase the current rate of soil reuse from 13% to 50%. |

| Roadmap to a Resource-Efficient Europe (EC, 2011)7 | Milestone 4.6: Achieve no net land take by 2050. |

| Eighth Environment Action Programme to 2030 (EC, 2020b)8 | Objectives: Decoupling economic growth from resource use and environmental degradation; targeting a zero-pollution ambition for a toxin-free environment, including air, water, and soil; protection, preservation, and restoration of biodiversity. |

Reiterating that the EU lacks direct authority over spatial planning is essential. Nevertheless, specific MS have defined their intentions to lessen land take by implementing spatial planning regulations. In October 2021, the Austrian Conference on Spatial Planning was tasked with formulating Austria’s inaugural Soil Strategy, which seeks to decrease land consumption from 11.5 hectares daily to 2.5 hectares by 2030. Although the strategy was initially scheduled for presentation at the end of 2022, it has faced multiple delays [20]. In Switzerland, the goal of the Swiss National Soil Strategy9, enacted in 2020, was to safeguard the functions, fertility, and potential of soil for the benefit of society, the economy, and the environment, with a target of achieving zero net soil loss from the year 2050 onwards. Germany emphasized the preservation of agricultural land for food production and established a target of 0.3 km2 per day by 2020, as indicated in its 2016 report [6]. On the contrary, in 2006, the conversion rates of agricultural land to residential purposes in Poland were notably high, varying between 3.6% and 10.5%, positioning the country among the leaders in Europe [21]. Such alterations in land use and the depletion of soil resources may lead to irreversible consequences for fragile landscapes, influencing or entrenching inequalities in access to high-quality soils among different factions [22]. Thus, the soil consumption resulting from urbanization can be interpreted as a spatial justice concern, notably when it modifies the distribution of high-quality soils along the urban continuum [23]. Studies have shown that soil resource depletion is associated with territorial disparities, economic underdevelopment, poverty, and increased human pressure on sensitive rural areas [24].

In light of these developments and the urgent need for coordinated and coherent action on climate resilience, biodiversity conservation, and soil health, a comprehensive assessment of the legal dimensions of land use is both timely and necessary [25]. Achieving EU-wide targets, such as the transition to a climate-neutral land use sector, requires a more integrated and strategically aligned policy framework at the European level [26]. However, such alignment must be carefully balanced with the need to reflect national and local specificities. The effective integration of EU strategies into domestic contexts depends first on unfolding the legal and institutional complexities within MS, many of which feature fragmented, multi-layered governance systems. In certain countries, land use regulation adopts a decentralized governance structure, distributed across regional and local authorities [27]. While this approach accommodates the needed territorial diversity and context-specific priorities [28], it may hinder coherence with the overarching EU policy objectives.

Related to this challenge, this study intends to illuminate the conceptual distinctions among diverse legal frameworks and provisions related to land use in the five countries examined. The scope has been explicitly identified and articulated, focusing on providing a detailed exploration of the national legislative frameworks addressing soil consumption and land use planning. The primary aim is to delineate the key legal provisions, highlight regulatory distinctions, and identify significant gaps or deficiencies that may hinder effective policy integration. Through this analytical approach, the study contributes to the ongoing dialogue on how legal and governance systems can be improved to better respond to the complex and evolving land use challenges local communities face, ultimately supporting more cohesive yet context-sensitive pathways toward sustainability across Europe.

2. Materials and Methods

A comprehensive review of the literature and regulatory sources provided a wide-ranging overview of the existing legal frameworks, concentrating on the contrasting approaches to land use matters. To conduct a meaningful comparative analysis of land use legislation and governance, this study focuses on five countries: France, Greece, Italy, Poland, and Ukraine. These countries were purposefully selected to represent a diverse spectrum of European and neighboring land management contexts, each with distinct socio-political, legal, and environmental characteristics. France and Italy exemplify Western and Southern European approaches, where mature yet often fragmented planning systems face pressures from dense urbanization and land degradation [29,30]. Greece reflects typical Mediterranean challenges, including spatially discontinuous development and deregulated land use patterns [31]. Poland offers a Central and Eastern European perspective, where a traditionally compact and state-directed planning legacy is increasingly influenced by liberal land conversion practices [32]. Ukraine, currently undergoing extensive legal and institutional transformation, provides a unique external reference point beyond the EU framework, offering insights into post-Soviet legal reforms and the alignment efforts with European land governance principles [33]. This geographical and legal diversity allows the study to identify the common gaps and unique opportunities for enhancing sustainable land use policy and practice across different governance settings.

The keywords selected to conduct the analysis were “land use management”, “land use–land take”, “land use change”, “land use, land cover (LULC)”, and “land degradation”. The study incorporated a wide array of resources, including the official websites of relevant government ministries, legislative databases such as those of the European Parliament, legal databases like Eur-Lex and FAO-Lex, Normattiva, the official portal of the Parliament of Ukraine, as well as research through platforms like Google Scholar and European databases, including the official website of the EU and the EEA. The timeframe for the above search was set between 2018 and 2025 to capture and derive the most updated results. Overall, the study presents a comprehensive assessment of land use regulations, highlighting the key challenges and emphasizing the need for robust, transparent, and harmonized guidelines to effectively support sustainable land use planning.

3. Results

Various factors, including agroclimatic conditions, historical land uses, deregulation of land use and cover, socioeconomic factors, and land management schemes, significantly influence the patterns of land systems in the EU. Historical land use significantly influences the current condition of land systems, with effects that can last for decades or even centuries [34]. For instance, the eastern border of Germany experienced its first wave of agricultural intensification in the late nineteenth century, characterized by extensive farming estates [35]. Agroclimatic conditions also significantly influence the patterns of land systems in Europe. Despite the introduction of technological innovations and significant investments to counteract these conditions, such as drainage, fertilization, and irrigation, agroclimatic factors persist as key determinants of land use intensity. Delving deeper, the urbanization trends are notably strong in certain European areas, particularly along coastal regions and in Western Europe, often accompanied by the abandonment and declining intensity of land use in the hinterlands. This situation can be partially linked to rural–urban migration, driven by rising per capita GDP in urban areas and diminishing income opportunities in rural regions [36]. Such trends have been observed in Italy [37], the Mediterranean [38], Switzerland [39], and Eastern Europe [40]. Other factors, such as transferring land-based production to regions outside the EU, significantly influence the stability of Europe’s land systems. The “outsourcing” of agricultural activities to areas with lower production costs now constitutes roughly one-third of the land required to meet Europe’s demands [41]. Finally, the deregulated urban development, especially prominent in Italy and Greece, in conjunction with ineffective land management, has sometimes caused a divergence in the quality of natural resources, which could influence the socio-ecological conditions in the area [42]. Historically, Mediterranean regions have relied on low-quality soils to support forests and pastures, with fertile soils dedicated to agriculture. However, urban expansion increasingly competes with agricultural land for these high-quality soils [43]. This trend has had a detrimental impact on the economic health of the primary sector and the sustainable delivery of vital ecosystem services in peri-urban settings [44].

3.1. Greece

According to the findings of Chatzitheodoridis et al. (2024), Greece is notable for its lack of a unified national urban strategy and a “non-planning” heritage [45]. Various studies have pointed out the deficiencies in spatial planning within Greece, highlighting the ineffectiveness of enforcing building and planning regulations and the notably protracted timeline for land use plan approvals [46,47]. The state does not systematically and intentionally select which regions to govern through spatial planning. Instead, it tends to respond in a fragmented manner, often reflecting on past actions rather than planning proactively [48]. Due to remarkable urban sprawl over thirty years spanning from 1990 to 2018, the country’s rapid and uncontrolled land change has significantly altered more than 1700 km2 from rural and forested lands into urban uses. If this trajectory continues, by 2030 the urban land coverage is expected to be double the extent recorded in 1990 [49]. The national government assumes the most significant responsibilities in Greece’s multifaceted spatial planning system. It manages the essential legislative framework concerning regional and urban planning, environmental safeguarding, and regional development initiatives. Of the 25 distinct types of spatial plans available, 22 have been officially supported by the national government. The role of regions in land use is largely restricted, primarily engaged solely in advisory capacities, assisting in formulating various spatial planning documents [50]. In the same report, the OECD notes that many spatial plans remain in effect despite being replaced by recent ones, resulting in considerable convergence between the various plans.

Table 2 delineates the critical law articles and chapters with the rationale for their establishment, summarizing Greece’s legal framework on spatial planning and highlighting the targets and goals for minimizing land take.

Table 2.

Greece’s legislative framework.

3.2. Italy

Italy is a unitary country; nonetheless, its land use planning system adopts characteristics commonly associated with federal structures. The primary legal guidelines governing the planning process are derived from regional laws and regulations. Municipalities play a crucial role in determining land use at the local level, primarily through implementing the Local Development Plan (LDP) [51]. In 1942, the national legal framework established a three-level planning system, comprising regional plans (Piano Territoriale di Coordinamento Regionale—PTCR) commonly integrated into a web-GIS data system called SITAP15 founded in 1996, which focuses on the management, consultation, and distribution of information concerning restricted areas as per the prevailing landscape protection legislation. The second tier of the hierarchy pertains to the provincial plans, known as the Piano Territoriale di Coordinamento Provinciale (PTCP), while the third tier is associated with municipal planning. The aforementioned plans are implemented in conjunction with the Piano di Assetto Idrogeologico—PAI, which aims to mitigate hydrogeological risk while ensuring compatibility with existing land uses, thereby protecting public safety and reducing potential damage to vulnerable properties. This system provided an overarching regulatory context for the local plan (Piano Regolatore Generale—PRG), incorporating zoning stipulations [52]. The LDP delineates strategies designed to protect and improve the landscape, potentially imposing restrictions on the nature and scale of developments permitted in areas recognized for their natural, cultural, or historical importance. This legal framework for planning in Italy has been in effect since 1942. The system was initially established to control the outward spread of urban agglomerations, with a strong emphasis on expropriation and public development efforts. Although later reforms and court decisions have reduced this emphasis, the LDP has remained fundamentally unchanged as the primary planning instrument [51]. Italy does not possess a national law dedicated to reducing land take or revitalizing urban environments. Since 1970, however, it has delegated all legislative and executive functions in these areas to the regions which enact their laws (Leggi Regionali Urbanistiche), delineating urban planning procedures. A case in point is the Basilicata Regional Planning Law (L.R. 23/199916), which oversees territorial planning to ensure the robust protection of natural and cultural resources, facilitate effective urban regeneration, and support the establishment of a resilient infrastructure. The lack of a unified strategy has resulted in regional laws exhibiting considerable variation in scope and detail. Each region may have numerous plans that cover the full extent of the regional area, specific conservation zones, and a wide array of municipal land use plans [53]. Differing regulations, geographical scopes, and designated authorities characterize these plans. The overarching goal of most existing laws in Italy, which vary by region concerning land use management, does not emphasize planning as a fundamental aspect. Instead, it views urban regeneration primarily as enhancing specific segments of urbanized land, achieved through physical—spatial and urban development planning, sometimes supported by volumetric or economic incentives [54]. Table 3 delineates all the pertinent legislation in force at the regional and national tiers.

Table 3.

Italy’s legislative framework.

3.3. France

In France, the challenges associated with land use planning are multifaceted, mainly stemming from the inherent discord within a governance system that features a dominant national government actively involved in nearly all areas of French society, juxtaposed with a strong tradition of local democracy. This dynamic has given rise to many elected local governments, commonly known as communes [55]. Land use planning is merely one of the many responsibilities that these governmental entities manage. France’s planning system has traditionally been characterized as a “regional economic” approach, which seeks to achieve various social and economic objectives, particularly in addressing regional disparities in wealth, employment, and social conditions [56]. Recently, this system has begun to evolve towards a “comprehensive, integrated” approach, emphasizing spatial coordination through a hierarchy of plans, moving away from a primary focus on economic development [56]. Until the 2000s, the predominant purpose of spatial planning in France was to orchestrate urban development and locate economic activities. Today, however, the focus has shifted towards curbing urban sprawl, conserving natural and agricultural environments, and steering development to prioritize energy efficiency, resulting in lower GHG emissions [57]. France’s approach to spatial planning is increasingly characterized by an integrated framework that spans several thematic areas, including ecosystem protection, climate change adaptation and mitigation, and land use management. Moreover, there is a significant focus on comprehensive strategies that advocate for inter-municipal planning initiatives [55]. France does not have a comprehensive national spatial planning system; the country utilizes only sectoral guidelines articulated through the Schémas de Services Collectifs (SSC) [58]. Established in 2000, the Schéma de Cohérence Territoriale (SCoT) functions as the essential document at the local level. Voluntary groups of municipalities formulated SCoT, including the Projet d’Aménagement et de Développement Durable (PAAD), which tackles the essential concerns regarding spatial quality and environmental protection [59]. Within macro-regional planning, the Directive Territoriale d’Aménagement (DTA) is an obligatory instrument to tackle the pressing environmental challenges encountered in expansive natural territories, including areas such as the Alpes Maritimes [60]. Table 4 illustrates the provisions and goals set forth by the active laws that govern France’s land use and spatial and urban planning.

Table 4.

France’s legislative frameworks.

3.4. Poland

The evolution of spatial planning in Poland over the last twenty-five years has been marked by a significant shift from a centrally planned, communal land tenure system under socialism to a decentralized and privatized approach within a market economy. Currently, the planning landscape encompasses national, regional, and local levels, where higher-order plans guide the more detailed lower-order plans. The national spatial policy articulates the overarching goals and objectives of the nation’s spatial development. It establishes a general planning framework and clarifies the responsibilities of subnational governments. Subsequently, regional authorities are tasked with creating more comprehensive plans and coordinating substantial public investments. Local governments, in turn, produce local spatial development plans that contain the most intricate details regarding specific land uses, policies, and practices. Despite this, the Polish planning system contains various inconsistencies contributing to suboptimal planning outcomes. Notable issues include (a) the frequent invocation of special infrastructural acts by the national government, which effectively suspend local planning laws, (b) the existence of areas devoid of local spatial development plans, which are instead governed by isolated planning decisions, and (c) the establishment of Special Economic Zones (SEZ) that lack alignment with local spatial objectives [61].

In Poland, the structure of the subnational government is organized into three levels: voivodeships (provinces), powiats (counties or districts), and gminas (communes or municipalities). The 16 voivodeships are predominantly based in historical regions. The country is further divided into 379 powiats, which include 65 cities that are granted powiat status, and 2479 gminas. Each level serves distinct political and administrative purposes, with essential differences in their functions. The regional level incorporates both regional self-governances. The coordination of regional-level planning, encompassing aspects such as infrastructure, cultural development, and environmental protection, falls under the purview of regional governments. These authorities create comprehensive regional spatial development plans and strategies that cover the entire territory of the voivodeship. Nonetheless, the non-binding nature of these plans on municipalities restricts their practical impact [61]. Between 2002 and 2016, Poland experienced significant changes in land use, with a decline of over 541,000 hectares in agricultural land and an increase of more than 568,000 hectares in forest land, as reported by cadastral statistics [62]. An issue that needs to be highlighted concerns the overly vague definitions of land use classifications, as identified by Kwartalnik-Pruc, which hinder the practical enforcement of legal provisions [63]. The challenge is not limited to land use classification within Poland; instead, it involves many datasets and indicators informed by geographical and statistical data about land use and land cover. In a similar vein, Marquard et al. [44], along with Bielecka and Jenerowicz [49], suggested that developing a more precise conceptualization of land take and its related concepts could significantly aid in understanding the complexities of the issue, thereby enhancing monitoring efforts and facilitating communication among countries. Table 5 meticulously delineates the current Polish legal framework, addressing issues pertaining to land use, land protection, the administrative structures and their roles in land planning at local and national levels.

Table 5.

Poland’s legislative frameworks.

3.5. Ukraine

Ukraine has undergone excessive transformations in land use and land cover dynamics following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 [64]. Given that around 70% of Ukraine’s territory is allocated to agricultural activities, the alterations within this sector have been remarkably significant. In the past five to ten years, these changes have been exacerbated by (i) the ongoing military conflict in Ukraine [65], (ii) the escalation in temperatures which has facilitated the adoption of double-cropping practices [66], (iii) the persistent activity of incinerating agricultural lands, and (iv) the development of strategies to facilitate the opening of the land market [67]. Investigating the current institutional configuration related to land resources and land use in Ukraine highlights a management system characterized by multiple levels and considerable complexity. This complexity arises from the diverse range of authorities and managerial organizations responsible for regulating and overseeing the management of land resources. The Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources, the State Ecological Inspection, the Ministry for Development of Communities and Territories of Ukraine, and the State Service of Ukraine for Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre, are involved in land use–land change processes. The foremost concern is the absence of a systematic approach to coordinating executive actions, which leads to ineffective monitoring of the appropriate execution of responsibilities by the governing bodies [68]. An analysis and exposition of the prevailing legislation concerning land use planning, the key principles of land protection, and the governmental structures tasked with the oversight of land planning in Ukraine are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Ukraine’s legislative frameworks.

The comparison of the five national legal frameworks reveals substantial variation in structure, coherence, and alignment with EU land use objectives. It is observed that Greece and Italy both exhibit complex, multi-layered legislative systems characterized by overlapping statutes and fragmented responsibilities across national and regional authorities. Specifically in Greece, frequent updates and the continued coexistence of older laws have created a labyrinthine regulatory landscape, hindering effective implementation. Likewise, Italy’s planning system is deeply rooted in historic legislative acts, such as the 1942 Urban Planning Law, which, despite subsequent amendments, still influences spatial governance but lacks the agility to adapt to contemporary environmental goals. In both countries, this legal pluralism often leads to interpretative uncertainty and protracted administrative procedures.

Contrary to the previous cases, France’s framework is more centralized and strategic, particularly through the SRU and Grenelle laws, which aim to integrate urban development with environmental and climate targets. While the legislative vision is coherent, its operational mechanisms remain largely policy-oriented rather than technically enforceable. Poland employs a relatively clear regulatory approach, prioritizing the safeguarding of agricultural and forest land. However, its spatial development concept lacks concrete enforcement instruments at the regional level. Ukraine’s legislative structure reflects a transitional legal culture, combining a formal commitment to land protection with challenges in institutional enforcement capacity. In Table 7, a summary of the patterns, barriers, and opportunities in the aforementioned strategies for each country is presented.

Table 7.

Summary table.

4. Discussion

Land use planning systematically integrates various administrative, economic, legal, and technical strategies to fulfil socio-economic and ecological objectives. This process is designed to maintain a socially responsible framework for land ownership, govern interactions related to land, and oversee the operations associated with land use. The necessity for appropriate land use planning stems from the need to address environmental concerns, socio-economic development, and human survival challenges. An integrated, holistic framework for sustainable land use planning will facilitate the sustainable utilization of natural resources. However, to achieve such a framework, it is crucial to acknowledge that it is not feasible to meet all competing objectives. Favoring the use and protection of one resource over another can lead to detrimental consequences. It is crucial to sustain an equilibrium between the losses and gains associated with various land types. This necessitates foresight to predict cumulative losses. Implementing the LDN strategy, for instance, may require adjustments in users’ land management practices and could lead to shifts towards alternative land uses [19]. Moreover, establishing clear guidelines is crucial in formulating a practical and effective land use framework, as it provides the basis for sound landscape–ecological decision making in land use practices. By applying these guidelines, one can evaluate the current functional utilization of the area and co-develop strategies for the optimal allocation and management of various land use alternatives [69].

Examining the legislative frameworks at the national level across the five countries, our findings reveal marked differences and several commonalities. France, which maintained a centralized governance structure until the 1960s, has undergone a significant decentralization process focused on regional and economic planning. This evolution has led to inter-community cooperative associations that are pivotal in shaping spatial development strategies through the SCoT instrument. On the same axis, Greece has integrated the policy of developing and implementing strategies within a central state administrative framework. In contrast, Italy has delegated all planning authority to regional governments, resulting in a fragmented legislative framework and a lack of effective coordination at the national level. The country is presently amid a territorial administrative reform that aims to replace some provinces with metropolitan cities. Upon reviewing the planning instruments utilized in France, Italy, and Poland, several commonalities can be identified, particularly in the normative nature of local-level plans that offer direction for lower-tier planning efforts. In Greece and Ukraine, the regulatory landscape is notably intricate, featuring overlapping legal provisions and a diverse array of national stakeholders responsible for the issuance, implementation, and oversight of regulations. Environmental factors are integrated into spatial planning laws across all five countries. Additionally, each planning system contains components dedicated to conserving valuable natural landscapes, with the French model of sensitive natural spaces illustrating a taxation strategy that facilitates the management of these critical areas [60].

Building on these observations, it becomes evident that the legal and institutional configurations underpinning land use planning differ substantially across countries, with significant implications for integrating EU-level strategies into domestic frameworks. While the commitment to sustainability objectives such as landscape conservation are broadly shared, the governance structures through which these objectives are pursued vary considerably [15]. Systems differ in the degree of decentralization, legal fragmentation, and coordination between planning authorities. These differences are not merely procedural; they reflect deeper institutional and historical trajectories that shape how planning instruments are deployed and interpreted in practice. Such institutional diversity affects the formulation of land use plans and the implementation of key targets, including those outlined in the Soil Strategy for 2030 and the revised LULUCF regulations. By unfolding the underlying legal architectures, the findings emphasize that coherence in land use governance requires not only the technical harmonization of data-based tools but also legal and institutional alignment across scales. Misalignments, including overlapping mandates, regulatory inconsistencies, and weak enforcement mechanisms, can hinder progress toward sustainability goals, particularly where land degradation, socio-spatial inequality, and biodiversity loss intersect. Advancing more integrated and adaptive planning systems will thus require reforms that support policy coherence and flexibility to reflect territorial diversity.

Although this research achieved its aim, it is important to acknowledge certain inherent limitations. Firstly, this research predominantly centers on examining national legislative documents, omitting the viewpoints of stakeholders and empirical evidence. Another constraint is the limited representation of European countries, which does not adequately reflect the full range of land use planning approaches. Additionally, although a comparative review of five different nations is provided, we do not furnish any evaluation or effectiveness metrics grounded in real-world outcomes. As a result, our analysis is limited to the structural and formal characteristics of the national legal frameworks.

The integration of scientifically validated indicators—aligned with the SDGs, EU Green Deal, revised regulations on LULUCF, and other relevant policy frameworks—into unfolded regional and national land use strategies is critical for advancing evidence-based planning and management that promotes environmental sustainability, socio-economic equity, and the transition toward a climate-neutral land use sector. Therefore, the next stage of future research should create an integrative ecosystem of tools, frameworks, and strategies that bridge the gap between scientific knowledge and policy implementation. Furthermore, future research could examine the potential of including stakeholders’ inputs for detailed and real-world mapping of land use planning. This prospective, all-encompassing approach will support sustainable, inclusive, and EC-aligned land use planning that responds to global sustainability objectives and local development needs.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a comparative assessment of the land use legislation in five European countries is presented. The focus of this study is to examine the alignment of the land use legislation with the sustainable spatial planning and land degradation objectives. According to our analysis, major variations are observed in legal structure, clarity, and institutional capacity, highlighting the importance of harmonizing land use and environmental goals for sustainable development. All countries face significant implementation challenges, especially regarding monitoring, enforcement, and harmonization with the EU targets and directives.

These findings underscore the importance of coherent and enforceable land use policies applicable on a national and international scale. Further research should incorporate stakeholder engagement and empirical evaluation for a comprehensive understanding of the implementation effectiveness and to pinpoint realistic and feasible strategies for achieving zero net land take.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.K. and I.V.; Data curation, I.V.; Formal analysis, D.K., A.A., E.G. and D.S.; Investigation, D.K., M.G., E.G., A.D., R.D., O.S. and C.K.; Methodology, D.K., I.V., M.G., R.B., D.S. and M.M.; Project administration, I.V., D.H., A.P., A.S. and G.K.; Resources, I.V., Y.K., O.M., A.S., M.M., P.C. and C.K.; Supervision, I.V., D.H., R.B., I.G., S.I., M.T. and P.C.; Validation, I.V., R.B., I.G., N.G. and D.C.; Visualization, D.K.; Writing—original draft, D.K.; Writing—review & editing, D.K., I.V., R.B., I.G., N.G., D.C., A.F.M., M.T. and G.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by LANDSHIFT, grant number 101182007.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the ‘LANDSHIFT’: Community-Led Creation of Living Spaces in Shifting Landscapes for Climate-Resilient Land Use Management and Supporting the New European Bauhaus. The “LandShift” project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe Research and Innovation Programme (HORIZON-CL6-2024-CLIMATE-01-4) under Grant Agreement No. 101182007.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

References

- Guides|SEDAC. Available online: https://sedac.ciesin.columbia.edu/guides (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- de Groot, R.S.; Alkemade, R.; Braat, L.; Hein, L.; Willemen, L. Challenges in integrating the concept of ecosystem services and values in landscape planning, management and decision making. Ecol. Complex. 2010, 7, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee-Gammage, S.; Garnett, T. What Is Land Use and Land Use Change? Food Climate Research Network: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquard, E.; Bartke, S.; Gifreu i Font, J.; Humer, A.; Jonkman, A.; Jürgenson, E.; Marot, N.; Poelmans, L.; Repe, B.; Rybski, R.; et al. Land Consumption and Land Take: Enhancing Conceptual Clarity for Evaluating Spatial Governance in the EU Context. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, G. Impact of land-take on the land resource base for crop production in the European Union. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 435–436, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goździewicz-Biechońska, J. Law in the face of the problem of land take. Przegląd Prawa Rolnego 2020, 1, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, K. Geography, policy or market? New evidence on the measurement and causes of sprawl (and infill) in US metropolitan regions. Urban. Stud. 2014, 51, 2629–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, A.; Bernt, M.; Großmann, K.; Mykhnenko, V.; Rink, D. Varieties of shrinkage in European cities. Eur. Urban. Reg. Stud. 2016, 23, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvati, L.; Quatrini, V.; Barbati, A.; Tomao, A.; Mavrakis, A.; Serra, P.; Sabbi, A.; Merlini, P.; Corona, P. Soil occupation efficiency and landscape conservation in four Mediterranean urban regions. Urban. For. Urban. Green. 2016, 20, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlucci, M.; Chelli, F.M.; Salvati, L. Toward a New Cycle: Short-Term Population Dynamics, Gentrification, and Re-Urbanization of Milan (Italy). Sustainability 2018, 10, 3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvati, L.; Morelli, V.G. Unveiling Urban Sprawl in the Mediterranean Region: Towards a Latent Urban Transformation? Int. J. Urban. Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 1935–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oueslati, W.; Alvanides, S.; Garrod, G. Determinants of urban sprawl in European cities. Urban. Stud. 2015, 52, 1594–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, R.; Escobar, F. The territorial dynamics of fast-growing regions: Unsustainable land use change and future policy challenges in Madrid, Spain. Appl. Geogr. 2011, 31, 650–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Land Use. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/topics/in-depth/land-use (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- Peskett, L.; Metzger, M.J.; Blackstock, K. Regional scale integrated land use planning to meet multiple objectives: Good in theory but challenging in practice. Environ. Sci. Policy 2023, 147, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büchler, S.; v. Ehrlich, M. Quantifying land-use regulation and its determinants. J. Econ. Geogr. 2023, 23, 1059–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. Land Cover Accounts—An Approach to Geospatial Environmental Accounting. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/land-cover-accounts (accessed on 12 August 2024).

- UNCCD. ICCD/COP(12)/20/Add.1. Available online: https://www.unccd.int/official-documents/cop-12-ankara-2015/iccdcop1220add1 (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Cowie, A.L.; Orr, B.J.; Castillo Sanchez, V.M.; Chasek, P.; Crossman, N.D.; Erlewein, A.; Louwagie, G.; Maron, M.; Metternicht, G.I.; Minelli, S.; et al. Land in balance: The scientific conceptual framework for Land Degradation Neutrality. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 79, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECOSCOPE. Addressing Austria’s Growing Flood Risks. Available online: https://oecdecoscope.blog/2024/09/19/addressing-austrias-growing-flood-risks/ (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Ustaoglu, E.; Williams, B. Determinants of Urban Expansion and Agricultural Land Conversion in 25 EU Countries. Environ. Manage. 2017, 60, 717–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, A.; Salvati, L.; Sabbi, A.; Colantoni, A. Soil resources, land cover changes and rural areas: Towards a spatial mismatch? Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 478, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briassoulis, H. Governing desertification in Mediterranean Europe: The challenge of environmental policy integration in multi-level governance contexts. Land. Degrad. Dev. 2011, 22, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvati, L.; Ferrara, A. Do land cover changes shape sensitivity to forest fires in peri-urban areas? Urban. For. Urban. Green. 2014, 13, 571–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Towards Sustainable Land Use. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/towards-sustainable-land-use_3809b6a1-en.html (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Kalfas, D.; Kalogiannidis, S.; Papaevangelou, O.; Chatzitheodoridis, F. Assessing the Connection between Land Use Planning, Water Resources, and Global Climate Change. Water 2024, 16, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, T.; Hengstermann, A.; Jehling, M.; Schindelegger, A.; Wenner, F. Introducing Land Policies in Europe. In Land Policies in Europe: Land-Use Planning, Property Rights, and Spatial Development; Hartmann, T., Hengstermann, A., Jehling, M., Schindelegger, A., Wenner, F., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadashpoor, H.; Ghasempour, L. A review of the necessity of a multi-layer land-use planning. Landsc. Ecol. Eng. 2024, 20, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coluzzi, R.; Bianchini, L.; Egidi, G.; Cudlin, P.; Imbrenda, V.; Salvati, L.; Lanfredi, M. Density matters? Settlement expansion and land degradation in Peri-urban and rural districts of Italy. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 92, 106703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifollahi-Aghmiuni, S.; Kalantari, Z.; Egidi, G.; Gaburova, L.; Salvati, L. Urbanisation-driven land degradation and socioeconomic challenges in peri-urban areas: Insights from Southern Europe. Ambio 2022, 51, 1446–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spatial Patterns of Land Take in a Mediterranean City: An Assessment of the SDG Indicator 11.3.1 in the Peri-Urban Area of Thessaloniki. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2073-445X/14/5/965 (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Deslatte, A.; Szmigiel-Rawska, K.; Tavares, A.F.; Ślawska, J.; Karsznia, I.; Łukomska, J. Land use institutions and social-ecological systems: A spatial analysis of local landscape changes in Poland. Land Use Policy 2022, 114, 105937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saik, P.; Koshkalda, I.; Bezuhla, L.; Stoiko, N.; Riasnianska, A. Achieving land degradation neutrality: Land-use planning and ecosystem approach. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1446056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.R.; Carpenter, D.N.; Cogbill, C.V.; Foster, D.R. Four Centuries of Change in Northeastern United States Forests. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e72540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedertscheider, M.; Kuemmerle, T.; Müller, D.; Erb, K.-H. Exploring the effects of drastic institutional and socio-economic changes on land system dynamics in Germany between 1883 and 2007. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 28, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seto, K.C.; Fragkias, M.; Güneralp, B.; Reilly, M.K. A Meta-Analysis of Global Urban Land Expansion. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedertscheider, M.; Erb, K.-H. Land system change in Italy from 1884 to 2007: Analysing the North–South divergence on the basis of an integrated indicator framework. Land Use Policy 2014, 39, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stellmes, M.; Röder, A.; Udelhoven, T.; Hill, J. Mapping syndromes of land change in Spain with remote sensing time series, demographic and climatic data. Land Use Policy 2013, 30, 685–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gellrich, M.; Baur, P.; Koch, B.; Zimmermann, N. Agricultural land abandonment and natural forest re-growth in the Swiss mountains: A spatially explicit economic analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2007, 118, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, D.; Kuemmerle, T.; Rusu, M.; Griffiths, P. Lost in transition: Determinants of post-socialist cropland abandonment in Romania. J. Land Use Sci. 2009, 4, 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastner, T.; Erb, K.-H.; Haberl, H. Rapid growth in agricultural trade: Effects on global area efficiency and the role of management. Environ. Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 034015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvati, L.; Carlucci, M. Zero Net Land Degradation in Italy: The role of socioeconomic and agro-forest factors. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 145, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvati, L.; Karamesouti, M.; Kosmas, K. Soil degradation in environmentally sensitive areas driven by urbanization: An example from Southeast Europe. Soil. Use Manag. 2014, 30, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, V.; Tonts, M. Containing Urban Sprawl: Trends in Land Use and Spatial Planning in the Metropolitan Region of Barcelona. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2005, 48, 7–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzitheodoridis, F.; Melfou, K.; Kontogeorgos, A.; Kalogiannidis, S. Exploring Key Aspects of an Integrated Sustainable Urban Development Strategy in Greece: The Case of Thessaloniki City. Smart Cities 2023, 6, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakourou, G. Transforming spatial planning policy in Mediterranean countries: Europeanization and domestic change. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2005, 13, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economou, D. The Planning System and Rural Land Use Control in Greece: A European Perspective. 1997. Available online: http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-0031411506&partnerID=40&md5=498f9796217602a772a6233459250230 (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Coccossis, H.; Economou, D.; Petrakos, G. The ESDP relevance to a distant partner: Greece. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2005, 13, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stathakis, D.; Baltas, P. The Greek model of urbanization. Land Use Policy 2024, 140, 107113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Greece; OECD: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Italy; OECD: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rega, C. Ecological compensation in spatial planning in Italy. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2013, 31, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaldi, C. Consumo di suolo: Un complesso quadro di politiche, definizioni e soglie. Territorio 2022, 103, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conticelli, E.; Tondelli, S.; Rossetti, S.; Zazzi, M.; Caselli, B. La Nuova Disciplina Regionale Sulla Tutela e l’uso del Territorio in Emilia Romagna (L-R. 24/2017). L’ambiziosa Scommessa Della Terza Legge Urbanistica Regionale tra Conferme e Innovazioni; Italy, 2021. Available online: https://cris.unibo.it/handle/11585/937714?mode=complete (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Spatial and Land Use Planning in France|READ Online. Available online: https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/urban-rural-and-regional-development/the-governance-of-land-use-in-france/spatial-and-land-use-planning-in-france_9789264268791-5-en (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Europäische Kommission (Ed.) The EU compendium of spatial planning systems and policies-France. In Regional Development Studies, no. 28E; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Aix-Marseille, France; OECD: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geppert, A. France, Drifting away from the “Regional Economic” Approach; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2014; pp. 109–126. [Google Scholar]

- Spaans, M. The Changing Role of the Dutch Supralocal and Regional Levels in Spatial Planning: What Can France Teach Us? Int. Plan. Stud. 2007, 12, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocheci, R.-M. Planning in Restrictive Environments-A Comparative Analysis of Planning Systems in EU Countries. J. Urban. Landsc. Plan. 2016, 1, 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Governance of Land Use in Poland: The Case of Lodz; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development: Paris, France, 2016; Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/urban-rural-and-regional-development/governance-of-land-use-in-poland_9789264260597-en (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- Cegielska, K.; Noszczyk, T.; Kukulska, A.; Szylar, M.; Hernik, J.; Dixon-Gough, R.; Jombach, S.; Valánszki, I.; Filepné Kovács, K. Land use and land cover changes in post-socialist countries: Some observations from Hungary and Poland. Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwartnik-Pruc, A. Exclusion of land from agricultural and forestry production: Practical problems of the procedure. Geomat. Environ. Eng. 2011, 5, 69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Radeloff, V.; Gutman, G. Land-Cover and Land-Use Changes in Eastern Europe after the Collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skakun, S.; Justice, C.O.; Kussul, N.; Shelestov, A.; Lavreniuk, M. Satellite Data Reveal Cropland Losses in South-Eastern Ukraine Under Military Conflict. Front. Earth Sci. 2019, 7, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan, F.; Adamenko, T. Global and regional drought dynamics in the climate warming era. Remote Sens. Lett. 2013, 4, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R. Ukraine Oilseeds and Products Annual Soybean Crush Unleashed for MY2018/19. Preprints 2015. Available online: https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/report/downloadreportbyfilename?filename=Oilseeds%20and%20Products%20Annual_Kiev_Ukraine_4-3-2019.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Tretiak, N.; Sakal, O.; Kovalenko, A.; Kalinowski, S.; Tretiak, V.; Shtohryn, H.; Behal, I.; Klodzinski, M. Land Resources and Land Use Management in Ukraine: Problems of Agreement of the Institutional Structure, Functions and Authorities. Eur. Res. Stud. 2021, 24, 776–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izakovičová, Z.; Špulerová, J.; Petrovič, F. Integrated Approach to Sustainable Land Use Management. Environments 2018, 5, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).