Abstract

As a critical ecological barrier in the arid and semi-arid regions of northwestern China, the spatio-temporal evolution of vegetation carbon sequestration in the Hexi Corridor is of great significance to the ecological security of this region. Based on multi-source remote sensing and meteorological data, this study integrated second-order partial correlation analysis, ridge regression, and other methods to reveal the spatio-temporal evolution patterns of Gross Primary Productivity (GPP) in the Hexi Corridor from 2003 to 2022, as well as the response characteristics of GPP to air temperature, precipitation, and Vapor Pressure Deficit (VPD). From 2003 to 2022, GPP in the Hexi Corridor showed an overall increasing trend, the spatial distribution of GPP showed a pattern of being higher in the east and lower in the west. In the central oasis region, intensive irrigation agriculture supported consistently high GPP values with sustained growth. Elevated air temperatures extended the growing season, further promoting GPP growth. Due to irrigation and sufficient soil moisture, the contributions of precipitation and VPD were relatively low. In contrast, desert and high-altitude permafrost areas, constrained by water and heat limitations, exhibited consistently low GPP values, which further declined due to climate fluctuations. In desert regions, high air temperatures intensified evaporation, suppressing GPP, while precipitation and VPD played more significant roles. This study provides a detailed analysis of the spatio-temporal change patterns of GPP in the Hexi Corridor and its response to climatic factors. In the future, the Hexi Corridor needs to adopt dual approaches of natural restoration and precise regulation, coordinate ecological security, food security, and economic development, and provide a scientific paradigm for carbon neutrality and ecological barrier construction in arid areas of Northwest China.

1. Introduction

Since the Industrial Revolution, global climate issues have become increasingly severe, with atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations having soared by over 50% compared to pre-industrial levels. This change is primarily attributed to human activities, including unsustainable land use [1,2,3], as well as fossil fuel combustion, deforestation, urbanization, and others. These activities collectively accelerate CO2 emissions, triggering climate anomalies such as glacier melting and persistent high air temperatures. The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report indicates that atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations and annual anthropogenic emissions have continued to rise to historic highs [4]. Gross Primary Production (GPP) represents the largest carbon flux between terrestrial ecosystems and the atmosphere, determining the intensity of carbon input and serving as a critical parameter for carbon exchange between the biosphere and the atmosphere [5,6,7].

Early ground-based observations and biomass inventories primarily relied on single-point monitoring and biomass statistics. Swinbank proposed the eddy covariance technique, which was applied to measure sensible and latent heat fluxes in grasslands [8]. However, limited by instrument accuracy, continuous CO2 flux monitoring was not achieved until improvements were made in ultrasonic anemometers and infrared gas analyzers [9,10]. For instance, Wofsy et al. conducted the first year-round flux observations in Harvard Forest, laying the foundation for research on ecosystem carbon cycling [11]. In the early stages, the Miami model, proposed by H. Lieth, enabled regional-scale estimation of Gross Primary Production (GPP) for the first time based on statistical relationships between mean annual air temperature, precipitation, and GPP [12]. However, such models overlooked plant physiological processes. The development of satellite remote sensing advanced GPP research [13]. The launch of the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectro-radiometer (MODIS) sensor led to the widespread application of various models and factors in GPP studies [14,15,16], promoting a shift in GPP estimation from “empirical statistics” to “physiological process simulation”.

In recent years, numerous scholars both domestically and internationally have conducted extensive research on the change patterns and influencing factors of Gross Primary Production (GPP) across different regions. These studies have revealed significant spatio-temporal heterogeneity in vegetation productivity. For instance, in Qinghai Province, air temperature change caused by altitudinal gradients leads to considerable differences in GPP increases across different watersheds [17]. However, Zhang et al. found through their research on the impact of global surface temperature on changes in GPP that a moderate increase in temperature can promote the increase in GPP, but excessively high temperatures may cause plant heat stress and reduce GPP [18]. In the Northwest China Comprehensive Economic Zone, precipitation is identified as the primary factor driving spatial heterogeneity in GPP [19]. Research by Wang Xiaohong et al. on the Qinling-Bashan Mountains indicates that drought conditions have exacerbated negative impacts on GPP in cultivated land systems [20]. Similarly, extreme high-air temperature-induced drought events have also led to significant declines in GPP [21]. In contrast, a study by Yan Min et al. in the upper reaches of the Heihe River demonstrated that rising air temperatures and increased vapor pressure deficit (VPD) had a positive driving effect on GPP [22]. According to Zhang’s research on global regional terrestrial gross primary production, it was found that in some tropical and northern regions, GPP is significantly affected by precipitation, while in arid regions, it is related to evapotranspiration [23]. Additionally, inter-annual fluctuations in GPP show a significant positive correlation with regional hydrothermal conditions [24].

The Hexi Corridor is located in the core area of the arid and semi-arid regions in Northwest China, where the spatio-temporal distribution of water and heat resources is extremely uneven. During the growing season, it relies on short-term precipitation and meltwater to achieve a “highly efficient yet fragile” prosperity in production and ecology. During the non-growing season, it enters a dormant and stress-resistant period due to dry and cold conditions as well as wind and sand. This characteristic has shaped the alternating landscape of oases and deserts and also determined the local agricultural features of “dependence on irrigation and high disaster resistance costs” and the ecological features of “easy to be damaged and difficult to recover”, giving rise to the unique symbiotic ecosystem of “Qilian Mountains–Oasis-Desert”. It is a global climate change-sensitive area and an ecologically fragile zone [25]. In recent years, intensified climate change and enhanced human activities have led to significant alterations in the Gross Primary Productivity (GPP) of the Hexi Corridor. There are currently many models that assume a continuous supply of water [26], but these models struggle to simulate the carbon cycle processes under dry, cold, and sandy conditions. Furthermore, the global agricultural carbon accounting framework does not incorporate the unique coupling mechanisms of irrigated agriculture in arid regions, which leaves critical gaps in research on ecosystem responses and management in climate change-sensitive areas of arid regions. To clarify the Hexi Corridor spatio-temporal change patterns, uncover regional driving mechanisms, and address the research gaps in the carbon cycle of arid regions, this study analyzed the spatio-temporal characteristics of GPP in the Hexi Corridor, investigated its driving mechanisms, and explored future trends of GPP. These efforts are of great significance for regional ecological security and sustainable development. Furthermore, this study could offer practical theoretical and technical support for ecological management in “mountain–oasis–desert” symbiotic systems, such as those found around the Tarim Basin, the fringes of South America’s Atacama Desert, and the river basins of Amu Darya and Syr Darya in Central Asia.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

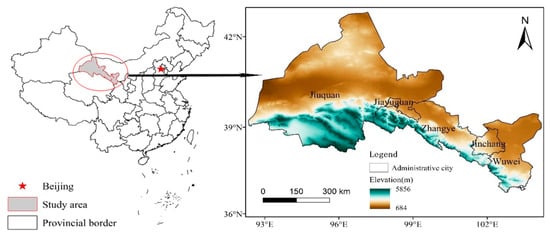

The Hexi Corridor (93°20′~104°00′ E, 37°10′~42°50′ N) is located in the northwestern part of Gansu Province, China (Figure 1), covering 5 cities including Jiuquan, with a total area of 2.71 × 105 km2. Its terrain is complex, with the landform sloping from east to west and from south to north, and an average altitude of 1000~1500 m. It has a temperate arid climate, characterized by dry and windy springs and cold, long winters. The Qilian Mountains in the south, subject to the cold climate of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau, exhibit significant vertical changes in water and heat conditions; they are the source of three major inland rivers and have low aridity. The northern part comprises the Beishan Mountains and the Alxa Plateau, with high aridity. The central desert–oasis plain has relatively high aridity. The annual average air temperature across the entire region is 4~10 °C, with precipitation of approximately 200 mm and evaporation exceeding 1500 mm [27,28].

Figure 1.

Geographical location of the study area.

2.2. Data Sources

2.2.1. Data for Vegetation Carbon Sink Analysis

The primary productivity data used for vegetation carbon aggregation are the MODIS MOD17A2H V6.1 dataset, which is a remote sensing data product released by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) (NASA Earthdata Search, https://search.earthdata.nasa.gov (accessed on 15 January 2025)). This product estimates the GPP of global terrestrial ecosystems based on MODIS sensor data, combined with meteorological observations and light use efficiency models, and can support ecological, climatological, and agricultural research. The V6.1 version has algorithmically optimized the calculation of air temperature and moisture stress factors to reduce the overestimation of GPP in high-latitude winters. After data calibration, the consistency with ground flux tower observations has been improved (the verification error has been reduced by approximately 15%). It also reduces cloud contamination and improves data continuity by enhancing cloud masking and temporal interpolation. Its original data have a spatial resolution of 500 m × 500 m and a temporal resolution of 8-day composites, covering global land surfaces (excluding permanent ice sheets and water bodies). In this study, according to the scope of the Hexi Corridor, the downloaded data were processed through unit conversion, outlier removal, and projection synthesis into monthly and annual GPP data from 2003 to 2022. Then, after extraction using a mask in ArcGIS 10.8.1, they were resampled to a spatial resolution of 100 m × 100 m.

2.2.2. Meteorological Data

The national monthly average air temperature and monthly average precipitation data from 2003 to 2022, with a spatial resolution of 1 km × 1 km, were provided by the National Earth System Science Data Center—Loess Science Data Center (http://loess.geodata.cn/ (accessed on 26 December 2024)). In this study, the monthly scale data were synthesized into annual data for the 20-year period using the sum method.

The vapor pressure deficit (VPD) data were obtained from the TerraClimate global 0.05° VPD dataset (https://climatedataguide.ucar.edu (accessed on 10 December 2024)). TerraClimate is a gridded dataset of monthly climate and climatic water balance for global land surfaces from 1958 to 2022. This dataset integrates refined spatial characteristics with temporal sequence information from 1958 to the present. Moreover, TerraClimate provides surface hydroclimatic variables that are more directly applicable to ecology and hydrology. In this study, the VPD data from 2003 to 2022 in this dataset were used; after being cropped and masked, they were resampled to a spatial resolution of 100 m × 100 m.

2.3. Research Methods

2.3.1. Trend Analysis

This study adopted Sen’s slope estimation method to detect the change trends of spatial differentiation characteristics. This method is particularly suitable for the analysis of long time-series datasets. It allows for the presence of breakpoints in the data and can eliminate the interference of extreme values or outliers in the data on trend judgment, thus demonstrating stronger advantages in time series analysis [29]. Its calculation formula is as follows:

In the formula, the trend degree β indicates the change trend of the sequence; xj and xi respectively represent the sequence values at time points j and i. When β > 0, it indicates an upward trend; when β < 0, it indicates a downward trend; when β = 0, the trend is not obvious.

The Mann–Kendall test method is used to detect the significance of trend changes in the Hexi Corridor [30,31]. Its advantage is that it does not require the data to follow a normal distribution and will not be affected by a small number of data outliers or extreme values.

In the formula, xi and xj are respectively the i-th and j-th data values in the time series; n is the length of the series; sgn is the sign function; S is the original value of the test statistic, and its sign attribute directly indicates the evolution direction of the time series.

Regression analysis simulates the trend changes of each grid and fits the slope of the data pixel-by-pixel, thereby comprehensively reflecting the spatio-temporal evolution characteristics of the data. Its specific calculation formula is as follows:

2.3.2. Hurst Exponent Analysis

The Hurst exponent analysis is a method based on the R/S (Rescaled Range) analysis, which is used to evaluate the change trends of long-term time-series data and the continuity characteristics of future changes relative to historical changes [32,33].

In the formula, the R/S ratio is the quotient of the rescaled range R (m) and the standard deviation S (m). When this ratio presents a power–law relationship with the time scale m, it indicates that the time series {Ri} exhibits the Hurst phenomenon. The exponent H is calculated via least squares regression in a logarithmic coordinate system, and the value range of the Hurst exponent is [0, 1]. When 0 < H < 0.5, it indicates that the future change trend of the time series is opposite to that of the past, showing anti-persistency. When H = 0.5, the change of the time series exhibits randomness. When 0.5 < H < 1, it indicates that the future trend of the time series is consistent with the past, showing persistency.

2.3.3. Partial Correlation Analysis

This study employed the second-order partial correlation analysis method to explore the independent impacts of precipitation (y), air temperature (z), and vapor pressure deficit VPD (w) on the total vegetation gross primary productivity GPP (x) [34]. Taking the partial correlation between GPP and precipitation (with air temperature and VPD controlled) as an example, a multiple linear regression of x on z and w is performed to obtain the residual ex:

Perform a multiple linear regression of y on z and w to obtain the residual ey:

The partial correlation coefficient is defined as the Pearson correlation coefficient between the residuals ex and ey:

In the above partial correlation analysis results, the positive or negative sign of the partial correlation coefficient indicates the direction of the influence of the independent variable, and the magnitude of the absolute value indicates the strength of the influence of the independent variable.

2.3.4. Ridge Regression Analysis

Ridge regression can eliminate multicollinearity among multiple independent variables and avoid the unbiasedness drawback of the least squares method. This study used ridge regression analysis to explore the sensitivity of GPP to three meteorological factors: air temperature, precipitation, and VPD [35], and its form is:

In the formula, is the sensitivity coefficient of meteorological factors to GPP; X is the observation matrix of meteorological factors; k is the ridge parameter; I is the identity matrix; X’ is the transpose of the observation matrix; Y is the n-dimensional measured vector of GPP.

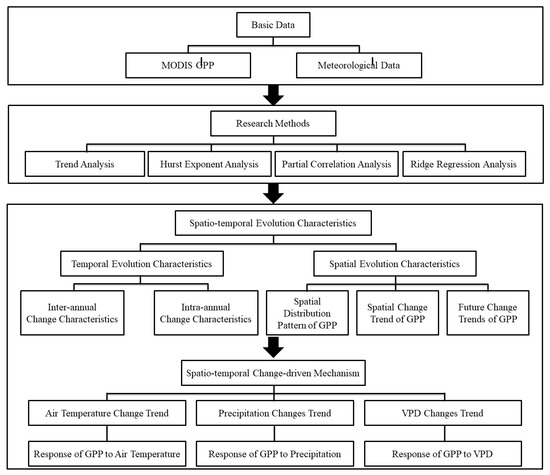

Flowchart of the spatio-temporal evolution characteristics of vegetation carbon sink in the Hexi Corridor is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the spatio-temporal evolution characteristics of vegetation carbon sink in the Hexi Corridor.

3. Results

3.1. Change Characteristics of GPP and Meteorological Factors from 2003 to 2022

3.1.1. Inter-Annual and Intra-Annual Change Characteristics of GPP

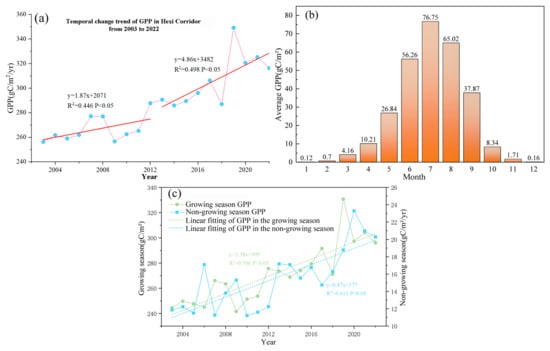

From 2003 to 2022, the GPP in the Hexi Corridor showed an overall significant increasing trend, rising from 256.3 gC/m2 to 316.3 gC/m2 (Figure 3a). The growth rate was slower in the first decade, while in the latter decade, the growth rate increased significantly with a high goodness of fit, indicating more stable growth. During the same period, the increase in air temperature or precipitation in the arid regions of Northwest China alleviated water limitation, promoted vegetation photosynthesis, and drove the accelerated growth of GPP in the later period. The high goodness of fit also reflects that in the latter decade, GPP was driven more consistently by factors such as policies and climate, and the system’s anti-interference ability had been enhanced.

Figure 3.

Temporal change trend of GPP in the Hexi Corridor from 2003 to 2022 (a), monthly average GPP (b), change trends of GPP in growing season and non-growing season (c).

From 2003 to 2022, the monthly average GPP in the Hexi Corridor exhibited significant seasonal change characteristics (Figure 3b). From December to February of each year, due to low winter air temperatures leading to vegetation dormancy and stagnation of photosynthesis, GPP remained in a low-value period. From March to June, with the rise in spring air temperatures and the germination of natural vegetation, it entered a period of rapid increase. From July to September, affected by high summer air temperatures and the peak growing season of oasis crops, GPP reached its maximum in July, forming a peak period. From October to November, along with the suspension of farmland cultivation after autumn harvests and the withering of natural vegetation, GPP began to decline slowly from October, entering a declining period.

Based on the vegetation characteristics of the Hexi Corridor, the period from April to September was defined as the growing season, and the rest as the non-growing season [36]. Analysis incorporating vegetation type data (Figure 3c) showed that from 2003 to 2022, the growing season GPP dominated the total amount, with the annual average value increasing significantly at a rate of 3.38 gC/m2/yr and reached a peak in 2019. The non-growing season GPP also showed an upward trend, with a growth rate of 0.47 gC/m2/yr, indicating that the contribution of the non-growing season to regional GPP has gradually increased.

3.1.2. Spatio-Temporal Characteristics of Meteorological Factors

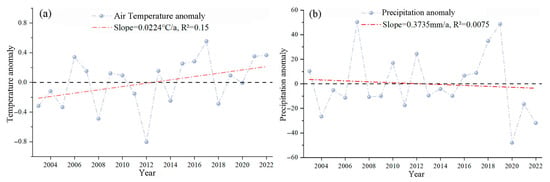

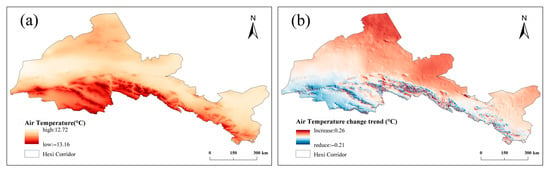

In the past 20 years, the Hexi Corridor has shown a slight warming trend (Figure 4a), which is slightly lower than the national average. However, there are significant inter-annual fluctuations, which may be related to precipitation variability and dust activities in Northwest China.

Figure 4.

Air Temperature anomaly of the Hexi Corridor (a) and precipitation anomaly (b).

From the perspective of spatial distribution (Figure 5a), the annual average air temperature of the Alxa Plateau in the northern part of the corridor was approximately 6~8 °C, while that of the northern foot of the Qilian Mountains in the south dropped to a minimum of −13 °C, and the oasis zone reached 10~12 °C. Due to the gradual increase in altitude from north to south within the corridor, the air temperature presented an anti-latitudinal distribution with higher values in the north and lower in the south. The vertical lapse rate of air temperature reached 0.65 °C/100 m, which significantly offset the influence of latitude [37]. The spatial change trend of annual average air temperature showed warming in the north and cooling in the south (Figure 5b), which may be related to the local circulation caused by topographic uplift at the northern margin of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau.

Figure 5.

Spatial Distribution (a) and Change Trend of Air Temperature in the Hexi Corridor (b).

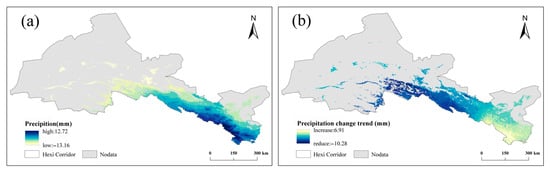

In terms of the temporal change characteristics of precipitation (Figure 4b), the slope of precipitation anomaly from 2003 to 2022 was 0.3735 mm/year, slightly higher than the national average. However, precipitation showed significant inter-annual fluctuations, with high uncertainty in its long-term trend. Compared with the air temperature change in the same period (0.224 °C/decade), the Hexi Corridor exhibited a warm-wet trend, but the degree of wetting was limited, and the risk of aridification remained dominant. Specifically, precipitation anomalies alternated frequently between positive and negative from 2003 to 2010, were generally positive from 2012 to 2020, and turned negative from 2020 to 2022, reflecting the intensification of aridification in the recent period.

In terms of the spatial distribution of precipitation (Figure 6a), the spatial pattern of precipitation is regulated by topography, forming a distinct gradient change. The northern foot of the Qilian Mountains, due to topographic uplift, had the highest annual precipitation of up to 697.33 mm. The oasis zone in the central part of the corridor has an annual precipitation of approximately 400 mm; the water supply in this region mainly relies on mountain runoff, and natural precipitation makes a relatively limited contribution to agricultural production. The high-altitude permafrost regions in the west and desert areas such as the Jiuquan and Minqin Deserts have an annual precipitation of less than 50 mm, with only 5.01 mm in extremely arid areas, where natural precipitation is insufficient to support plant growth.

Figure 6.

Spatial Distribution (a) and Change Trend of Precipitation in the Hexi Corridor (b).

The spatial change trend of precipitation from 2003 to 2022 showed an pattern of “increasing in the east and decreasing in the west” (Figure 6b). In the eastern regions of Wuwei and Zhangye, the annual precipitation increased by approximately 2 mm; this increase may be related to the enhanced water vapor flux in the westerlies. Desert areas such as Jiuquan and Minqin showed a decreasing trend, with a significant reduction in high-altitude permafrost regions in the western part of the southern Qilian Mountains, where the maximum reduction reached 10.28 mm. The significant decrease in precipitation indicates that global warming has exerted a notable impact on precipitation in alpine and plateau regions. Precipitation trends in areas such as oasis irrigation zones remained stable, with an annual fluctuation range of approximately 2 mm, reflecting the buffering effect of human activities on natural precipitation.

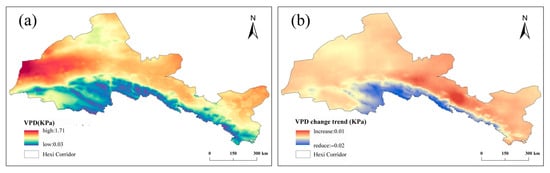

In terms of spatial distribution (Figure 7a), VPD showed a trend of being higher in the north and lower in the south. The northern foot of the Qilian Mountains, supported by mountain precipitation and snowmelt, had a VPD of 0.03 to 0.5 KPa, making it the lowest value area in the corridor. The central oasis zone, due to artificial irrigation and vegetation cover, maintained a VPD of 0.5 to 1.0 KPa; however, in some local areas, the VPD showed an increasing trend due to air temperature rise. The desert zones in the west and north were extremely arid, with a VPD as high as 1.71 KPa, and strong evaporation inhibits vegetation growth.

Figure 7.

Spatial distribution (a) and change trend of VPD in the Hexi Corridor (b).

The spatial change trends of VPD showed significant differentiation (Figure 7b). In the Qilian Mountain area and pre-mountain grassland belt, supported by increased precipitation and glacial meltwater recharge, VPD decreased by approximately 0.02 KPa annually. Although the central oasis zone has artificial irrigation, due to yearly rising air temperatures and uneven water resource utilization, VPD increased significantly, posing a risk of land desertification. In the northern desert zone, due to stable surface cover, VPD remained at a high level year-round, and its changes were not significant given the arid climate.

3.2. Response of GPP to Meteorological Factors

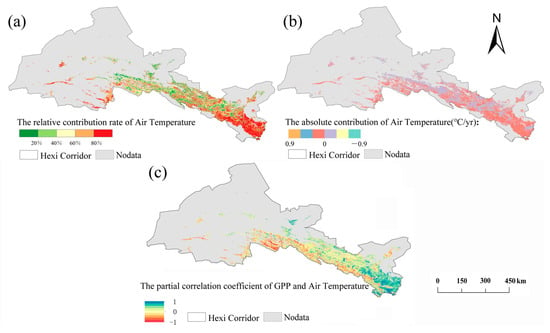

3.2.1. Response of GPP to Air Temperature

The spatial differences in the relative contribution rate of air temperature to GPP in the Hexi Corridor were significant (Figure 8a). In Wuwei City in the east, due to stable water–heat coupling under the guarantee of oasis irrigation, the air temperature contribution rate can reach 70~80%. In the desert marginal zone, the contribution rate dropped to 20~30% because vegetation growth is restricted by water limitation and inhibited by wind–sand activities. The contribution rate in the pre-Qilian Mountain grassland area was about 50%, reflecting the synergistic enhancement effect of mountain precipitation on air temperature effects.

Figure 8.

Relative contribution rate of air temperature to GPP changes (a), absolute contribution of air temperature to GPP changes (b), and partial correlation coefficient between GPP and air temperature (c).

In terms of the absolute contribution of air temperature to GPP (Figure 8b), it averaged 0.02~0.05 °C per year on the inter-annual scale, with both positive and negative contributions. Positive driving areas were mainly concentrated in the central oasis zone. Due to the prolonged vegetation growing season and improved light use efficiency, for every 1 °C increase in air temperature, the annual increment of GPP rises by 1.2~1.8 gC/m2. In contrast, negative inhibiting areas were mainly located in high-altitude permafrost regions of the Qilian Mountains and desert areas such as the Minqin Desert. Here, high air temperatures exacerbate soil moisture dissipation and weaken vegetation carbon sequestration capacity [28]; a 1 °C increase in air temperature leads to a reduction in GPP by 0.3~0.5 gC/m2.

From 2003 to 2022, the correlation between air temperature and GPP in the Hexi Corridor showed significant spatial heterogeneity (Figure 8c). Positively correlated areas were concentrated in Wuwei City in the eastern part of the corridor (excluding the Minqin Desert area in the north), especially in the Wushaoling region where the partial correlation coefficient was r > 0.6. This indicates that vegetation productivity in this region is sensitive to air temperature changes, Increased air temperatures lead to an earlier phenological period, thereby extending the growing season or enhancing photosynthesis to promote GPP accumulation [38]. Transitional areas cover Zhangye City, Jinchang City in the central corridor, and the grassland–desert ecotone at the northern foot of the Qilian Mountains, with partial correlation coefficients close to neutral. This is because irrigated agriculture and planted forests have improved local hydrothermal conditions in oasis areas, enhancing the positive driving effect of air temperature. However, the growth of drought-tolerant shrubs in desert areas depends on episodic precipitation, and increased air temperature exacerbates evapotranspiration, resulting in no significant correlation between GPP and air temperature. Negatively correlated areas were located in the southern Qilian Mountain region and the Minqin County desert area of Wuwei City. In the Qilian Mountain region, due to abundant precipitation, increased air temperature leads to earlier snowmelt or intensified evapotranspiration, reducing water supply in the middle and late stages of the growing season; moreover, high-altitude meadows/shrubs have low sensitivity to air temperature. In the Minqin desert area, high air temperature inhibits vegetation productivity [28].

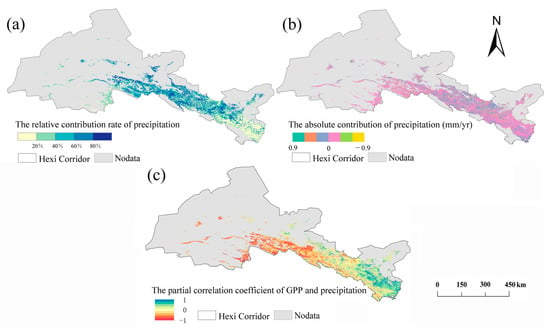

3.2.2. Response of GPP to Precipitation

The overall relative contribution rate of precipitation to GPP in the Hexi Corridor ranged from 20% to 90%, with significant spatial differences (Figure 9a). In desert areas such as Jiuquan, western Zhangye, and the Minqin Desert in Wuwei, the contribution rate reached 60~90%, reflecting the high dependence of arid ecosystems on precipitation [39]. In oasis irrigation zones, the contribution rate has decreased significantly due to human activities interfering with the water cycle, dropping to around 20% to 30%. The mountain grassland belts, affected by the dual effects of precipitation and glacial meltwater, have a contribution rate of approximately 40~50%.

Figure 9.

Relative contribution rate of precipitation to GPP changes (a), absolute contribution of precipitation to GPP changes (b), partial correlation coefficient between GPP and precipitation (c).

The inter-annual scale of the absolute contribution of precipitation to GPP is 0.05~0.12 mm/year; the contribution is not high, but shows significant spatial differentiation (Figure 9b). In positive contribution areas such as eastern Wuwei and the Wushaoling mountainous areas, due to improved vegetation coverage and enhanced photosynthetic activity, for every 10 mm increase in precipitation, the annual GPP increases by 2.5~4.0 gC/m2. The water sources in oasis areas mainly rely on artificial irrigation systems, so changes in precipitation have a weak impact on GPP, showing a neutral response.

From 2003 to 2022, the correlation between precipitation and GPP in the Hexi Corridor showed significant spatial differentiation characteristics (Figure 9c). Significantly positive correlation areas were concentrated in regions such as Wuwei City in the eastern corridor and Wushaoling, where the natural vegetation is dominated by grasslands and rain-fed farmlands. Precipitation serves as the core limiting factor for GPP; increased precipitation directly alleviates soil moisture stress, promoting plant photosynthesis and biomass accumulation. In the Minqin Desert zone of Wuwei, artificial vegetation has been introduced through windbreak and sand fixation projects. Its growth relies on groundwater rather than natural precipitation, resulting in a weak association between precipitation and GPP. Transitional areas cover the plain oasis zones in the central corridor, where precipitation has a weak driving effect on GPP. The vegetation in these areas is mainly crops, which mostly rely on artificial irrigation rather than precipitation for growth. Negative correlation areas were mainly distributed in the high-altitude permafrost regions in the southern part of the middle corridor. This region shows that increased precipitation instead inhibits vegetation productivity, indicating that coniferous forests or alpine shrubs have low sensitivity to precipitation. Their growth depends more on soil water storage than precipitation. Additionally, the well-developed irrigation systems in the oasis zones at the northern foot of the Qilian Mountains have partially replaced the contribution of natural precipitation to GPP, leading to a weakened correlation between precipitation and GPP.

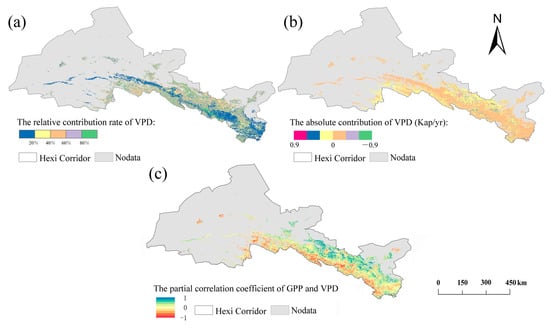

3.2.3. Response of GPP to VPD

From 2003 to 2022, the overall relative contribution rate of VPD to GPP in the Hexi Corridor was approximately 0~80% (Figure 10a), with significant spatial differences in the contribution rate. The relative contribution rate of VPD across the entire corridor forms a spatial pattern of high contribution rates in the northern and southern parts, with a strip of low contribution rates in the middle. In arid areas in the northern part of the corridor (such as the Minqin Desert and Jiuquan), the relative contribution rate of VPD to GPP changes can reach more than 80%. These regions have an extremely dry climate and scarce soil moisture, making vegetation extremely sensitive to changes in VPD. When VPD exceeds the threshold, vegetation will close its stomata to avoid excessive water loss, directly inhibiting vegetation productivity. In the southern part of the oasis in the middle of the corridor and the northern foot of the Qilian Mountains, due to the abundant groundwater resources provided by Qilian Mountain meltwater and irrigation systems [40], vegetation is less affected by VPD, and the relative contribution rate of VPD in this region drops to about 0~40%. In the high-altitude areas of the Qilian Mountains in the southernmost part of the corridor, climate warming in recent years has led to earlier snowmelt, resulting in reduced soil moisture in summer. Increased VPD will exacerbate water stress through evapotranspiration. Moreover, alpine meadows and shrubs are very sensitive to changes in VPD. The uninhabited high-altitude areas lack artificial water supply, and vegetation relies on natural precipitation and snowmelt. When VPD exceeds the threshold, vegetation will experience decreased stomatal conductance due to atmospheric drought. Therefore, the relative contribution rate of VPD in this region rises again to about 50~80%.

Figure 10.

Relative contribution rate of VPD to GPP changes (a), absolute contribution of VPD to GPP changes (b), and partial correlation coefficient between GPP and VPD (c).

From 2003 to 2022, the absolute contribution of VPD to GPP on the inter-annual scale ranged from −0.12 to 0.45 KPa/yr (Figure 10b). Positive contribution areas accounted for most of the area. Due to the alleviated evapotranspiration pressure and improved photosynthetic efficiency, for every 0.1 KPa decrease in VPD, the annual GPP increased by 1.0~1.5 gC/m2. In negative contribution areas, such as the Longshou Mountain region in the northern part of the middle corridor, high-air temperature and low-humidity conditions exacerbated water stress and increased the plants’ transpiration demand, resulting in weakened vegetation photosynthesis. For every 0.1 KPa increase in VPD, the annual GPP decreased by 0.2~0.4 gC/m2.

From 2003 to 2022, the correlation between VPD and GPP showed significant spatial differentiation characteristics (Figure 10c). Areas with significantly positive correlations were concentrated in the plain oases in the central part of the corridor. In this region, the oasis areas have well-developed irrigated agriculture, and artificial water sources have significantly alleviated natural water limitations. For example, under sufficient water conditions for oasis vegetation, an increase in VPD may be accompanied by enhanced photosynthetically active radiation, thereby driving an increase in GPP. Areas with low correlations were distributed in a zonal pattern along the northern foot of the Qilian Mountains in the southern part of the corridor. The altitude in this region gradually increases, indicating that the steep slope topography results in weak soil water-holding capacity. An increase in VPD exacerbates the drying of surface soil, causing water stress. Moreover, low nighttime air temperatures in high-altitude areas may prolong vegetation recovery time, and a sudden rise in daytime VPD leads to the dynamic imbalance of vegetation stomata, inhibiting carbon uptake. Transitional areas lie between the high and low correlation regions, distributed in a zonal pattern in the grassland–desert ecotone at the northern foot of the Qilian Mountains. The partial correlation coefficients ranged from 0.3 to 0.4, reflecting that the relationship between VPD and GPP is subject to the dual regulation of local precipitation and soil moisture.

3.3. The Spatial Change Trend and Future Change Trend of GPP

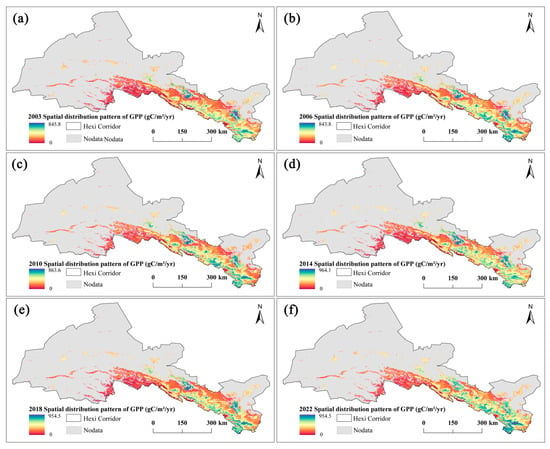

3.3.1. Spatial Distribution Pattern of GPP

This study, based on the GPP of the Hexi Corridor ecosystem from 2003 to 2022, analyzed the temporal and spatial distribution patterns of GPP in 6 different time periods to reveal the spatial distribution characteristics of GPP in the study area (Figure 11a–f). The vegetation GPP in the Hexi Corridor shows significant spatial heterogeneity and a phased growth trend.

Figure 11.

2003-2022 Spatial distribution pattern of GPP (a–f).

Specifically, the distribution and change of vegetation GPP in the Hexi Corridor over the past 20 years have shown significant spatial differentiation. In the plain areas in the middle of the corridor, especially the irrigated agricultural areas near the Qilian Mountains, such as the cultivated areas in Zhangye, Jinchang, and Wuwei, the crop vegetation is lush. Due to the stable supply of snowmelt water, farmlands and oases are distributed in contiguous patches, and the GPP values remain at a high level all year round. Near Wushaoling in the eastern part of the corridor and in the river valleys, the terrain obstruction forms a local humid environment, and the vegetation GPP has always been at a medium level. However, in desert areas and alpine regions with an altitude of more than 3000 m, the vegetation is always sparse. The former is arid and short of water, while the latter is cold with snow. The natural conditions restrict plant growth, resulting in a very low total vegetation GPP.

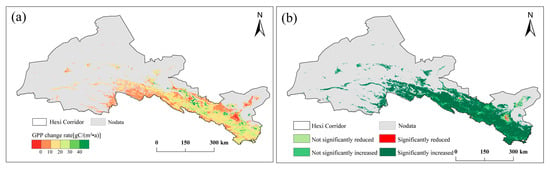

3.3.2. Spatial Change Trend of GPP

From 2003 to 2022, the annual change rate of GPP in the Hexi Corridor ranged from −10 to 50 gC/m2/yr, with significant spatial heterogeneity (Figure 12a). Most areas showed an increasing trend in GPP, among which regions with larger GPP increases were concentrated in the central oasis zones of the corridor, such as the oasis areas in Zhangye and Wuwei. This is highly consistent with irrigated agricultural areas and regions where artificial vegetation restoration projects are implemented, indicating that human activities have a positive driving effect on the improvement of GPP. In contrast, the high-altitude permafrost regions in the southern part of the corridor, restricted by cold climate and sparse vegetation coverage, had limited improvement in vegetation productivity, with the GPP change rate generally lower than 10 gC/m2/yr.

Figure 12.

Average change rate of GPP (a) and MK test (b) in the Hexi Corridor.

The change in GPP in the study area showed a “significantly increased” trend (Figure 12b), especially in the oasis zones in the central part of the corridor. With the rapid expansion of oases in the Hexi Corridor and local water resource allocation in recent years [41], the growth trend of vegetation productivity is highly significant, which also verifies the long-term cumulative effects of ecological projects such as grain for green and water-saving irrigation in recent years. In some desert areas, such as the vicinity of the Minqin Desert in the eastern corridor, GPP shows trends of not significantly decreased and significantly decreased, which reflects the negative feedback effect of drought impacts and regional ecological vulnerability on vegetation productivity. In the desert–oasis ecotone, such as the surrounding areas of Wuwei City, there were scattered pixels with “significantly decreased” in GPP, which may be related to the over-extraction of groundwater or land degradation caused by over-exploitation.

Overall, from 2003 to 2022, the GPP in the Hexi Corridor showed an overall increase, but there was degradation in some local areas. In oasis regions, due to the intensive use of water resources and the continuous implementation of vegetation restoration policies, GPP has increased significantly. In contrast, in desert areas, constrained by climate aridification and ecological vulnerability, GPP has mostly shown a decreased trend. This further verifies, from a spatial scale, the regulatory mechanism of the coupled effects of climate and human activities on the carbon sequestration capacity of vegetation.

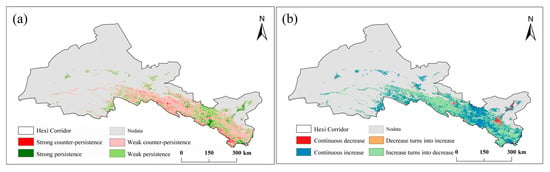

3.3.3. Future Change Trends of GPP

From 2003 to 2022, the future change trend of GPP in the Hexi Corridor showed significant temporal and spatial heterogeneity (Figure 13a). Strong persistence was concentrated in the central oasis irrigation areas of the corridor and the eastern Minqin Desert area, where future trends are consistent with the past. In oasis irrigation areas, due to artificial irrigation or ecological protection projects, GPP will continue to increase. In the Minqin Desert area, due to persistent drought and scarce vegetation, GPP will continue to decrease. Weak persistence areas accounted for most of the area, distributed in the southern high-altitude permafrost regions and near eastern Wushaoling. Their future trends are opposite to the past. For example, GPP around Wushaoling has increased in recent years, but affected by water resource constraints or climate fluctuations, the growth rate may slow down or even turn to decrease in the future.

Figure 13.

Hurst Index (a) and Hurst Classification (b) of GPP in the Hexi Corridor.

Based on the classification results (Figure 13b), the Continuous Increase type is mainly concentrated in the oasis agricultural areas in the middle and lower reaches of the Shule River and Heihe River Basins. The area, with an increasing trend in GPP in this region, will further expand in the future, reflecting that vegetation productivity remains stable under the synergistic effect of management policies such as water-saving irrigation and natural precipitation. The Increase turns into Decrease type accounts for most of the corridor’s area, including regions like the Wushaoling area in the eastern corridor and the Qilian Mountain belt in the middle section of the corridor. Although the historical GPP in this region has improved due to short-term increases in precipitation or ecological restoration projects, it may shift to a declining trend in the future, affected by continuous air temperature rise or falling groundwater levels. Continuously decreasing and scattered in the Shiyang River Basin, the Minqin arid region, and the urban center construction areas of the five cities in the Hexi Corridor, this indicates that the ecosystems in these regions have approached a threshold, making it difficult to reverse the process of carbon impairment. The Decrease turns into Increase type is sparsely distributed around the Persistent Decrease areas, which shows that vegetation in the vicinity of cities has recovered naturally under the policy of returning farmland to forests. However, vigilance is still needed regarding the potential threat of climate warming to the survival of vegetation seedlings.

In the context of GPP changes in the Hexi Corridor, oases continue to increase, but long-term ecological risks arising from the excessive exploitation of water resources must be guarded against. The vegetation productivity in most other regions is fragile, and natural vegetation areas are affected by climate. In the future, most GPP will decrease or continue to decrease, growth is unsustainable, and degradation is hard to reverse. It is recommended to enhance water use efficiency in oases, optimize water allocation, and avoid over-exploitation. For degraded areas, the restoration of key vegetation should be prioritized, and zoned management should be implemented to balance ecological protection and social development, thereby improving overall ecological resilience.

4. Discussion

The study on the spatio-temporal change characteristics of GPP in the Hexi Corridor from 2003 to 2022 revealed significant spatio-temporal heterogeneity in GPP within the region, which is similar to the Amazon rainforest with abundant precipitation [42]. The oasis areas in the Hexi Corridor also maintained a high total GPP throughout the year due to sufficient water supply. The permafrost regions in the southern Hexi Corridor, restricted by high altitude, consistently have low total GPP, which aligns with the pattern observed in the Sierra Nevada of the United States—where GPP decreases with increasing altitude [43]. By comparing the response of GPP to meteorological factors in the Sahara Desert [44], it was found that the vulnerability of vegetation carbon sinks in both regions is constrained by drought stress. Moreover, the contribution rate of precipitation in the desert areas of the western Hexi Corridor is as high as 60% to 80%, resulting in high sensitivity of GPP in this region to climate fluctuations. This characteristic is consistent with the ecological quality pattern of “high in the east and low in the west” analyzed by Yang Liangjie et al. based on the coupling coordination degree model [45], highlighting the core role of water resource management in regional ecological resilience. However, in the same region, different tree species compositions and stand management methods can also have a significant impact on ecosystem carbon fluxes [46]. Moreover, there are differences in GPP among different land cover types. The GPP of evergreen broad-leaved forests is usually higher than that of bare land [47]. In the study of carbon exchange in the Amazon tropical forest, it was found that GPP also has seasonal spatial heterogeneity [48]. It was found through the above research and comparison that the vegetation carbon sink function in the Hexi Corridor is synergistically regulated by natural factors and human intervention.

Based on the spatio-temporal change characteristics of GPP in the Hexi Corridor, it is known that GPP is significantly regulated by climatic factors such as air temperature, precipitation, and VPD under different environments. In the desert areas of the Hexi Corridor, precipitation is significantly positively correlated with GPP, while air temperature is negatively correlated with GPP. However, in the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau region at the same latitude, the contribution of air temperature to GPP is greater than that of precipitation [49]. This is similar to the equally low-air temperature Arctic, but due to the Arctic’s high latitude, the impact of air temperature is greater than that of precipitation [50]. However, in studies on the Amazon tropical forest, it was found that GPP shows strong sensitivity to water shortage [48]. In the oasis areas of the Hexi Corridor, air temperature is positively correlated with changes in GPP. However, compared with the Hexi Corridor, the correlation between air temperature and GPP is weaker in sparsely vegetated areas of Spain [51]. From the perspective of evaporation, arid regions (such as the desert areas of the Hexi Corridor and Central Asia) have high evaporation, and the sensitivity of GPP to VPD is greater than that in humid regions with sufficient soil moisture (such as the eastern coast of the United States and Europe) [52]. When Chen conducted research on the entire Asian region, he concluded that the spatial variation of carbon exchange flux is mainly controlled by climatic factors, and primarily by the annual average air temperature and annual average precipitation [53].

In addition, the regulation of these factors on GPP also exhibits significant spatial threshold effects. The critical effect of VPD reveals the risk of ecological degradation inflection points that the Hexi Corridor may face in the context of climate warming. When VPD exceeds the threshold, high air temperature and aridity exacerbate soil moisture dissipation, leading to a decrease in GPP in desert fringe areas. This phenomenon is similar to that in the semi-arid regions of southeastern Spain [51]. Zheng et al. systematically quantified the threshold effect of soil moisture on GPP through their research on plant water stress in European ecosystems [54]. There is an air temperature threshold for the size of ecosystem carbon sinks, and the air temperature threshold varies for different landscapes. Additionally, the threshold may increase with global warming [55]. Furthermore, the driving effect of precipitation on GPP shows spatial gradient differences: in oasis areas, the irrigation system weakens the response to precipitation, while desert areas are highly dependent on precipitation fluctuations. This result is consistent with that of Wang et al. [34]. This non-linear relationship verifies the “water–air temperature coupling hypothesis”, emphasizing that future climate predictions need to incorporate local water availability to assess regional thermal effects [45].

The stability of the carbon cycle system in the Hexi Corridor depends on the dynamic balance between natural processes and human activities. In oasis areas, water-saving irrigation technologies should be promoted, and the over-exploitation of groundwater should be strictly controlled to balance the water needs of agriculture and ecology. At the edge of deserts, drought-tolerant shrubs and other plants should be planted to build carbon sink barriers, and grazing and harvesting should be prohibited or restricted in the Qilian Mountains to protect forests and grasslands. Meanwhile, it is suggested that the Hexi Corridor region should take ecological security as the foundation, integrate the goal of cultivated land protection, and restrict the disorderly expansion of construction land. While pursuing economic development and food security, it is necessary to give consideration to ecological protection to avoid ecosystem degradation and the decline in the carbon sequestration capacity caused by unreasonable land use.

5. Conclusions

This study took the Hexi Corridor as the research area, with gross primary productivity (GPP) as the main parameter for vegetation carbon sinks, and systematically analyzed the spatio-temporal evolution characteristics and driving mechanisms of GPP from 2003 to 2022. The main conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- GPP in the Hexi Corridor exhibits gradient characteristics of being higher in the east and lower in the west, and higher in the south and lower in the north. The average annual total from 2003 to 2022 increased from 256.3 to 316.3 gC/m2. The growth rate in the growing season (3.38 gC/m2/yr) was significantly higher than that in the non-growing season (0.47 gC/m2/yr), reflecting that climate warming has extended the photosynthetic window. GPP in oasis areas showed continuous and stable growth, while growth in desert areas was slow due to drought constraints. In the future, GPP in high-altitude permafrost regions and desert areas may continue to decline.

- (2)

- The regulation of GPP by air temperature and precipitation showed significant spatial differentiation. In the oasis zones of the corridor, increased air temperature drives carbon sink gain by prolonging the growing season; sufficient artificial irrigation facilities reduce the contribution rate of precipitation to 20% to 30%. The contribution of VPD ranges from 0% to 40%, and a 0.1 KPa decrease in VPD could increase GPP by approximately 1.0 to 1.5 gC/m2. In desert areas, high air temperatures exacerbate water stress, inhibit vegetation activities, and bring the risk of carbon loss. GPP in desert areas is highly sensitive to precipitation and VPD: the contribution rate of precipitation to GPP changes reaches 60% to 80%; the contribution of VPD to GPP changes can exceed 80%, and when VPD > 2.5 KPa, it is prone to triggering water stress, inhibiting carbon absorption capacity.

This study analyzed the driving contributions of three meteorological factors—air temperature, precipitation, and VPD—to changes in GPP. However, there are certain limitations in the accuracy and reliability of the model. For example, the model’s ability to respond to extreme climate events is insufficient, and its dynamic simulation of human activities is not detailed enough. These limitations may lead to certain deviations between the prediction results and the actual situation. Therefore, in future related research, the model algorithm should be further improved to enhance its ability to simulate complex ecosystems. The uncertainty of model simulation also stems from the accuracy and time span of the data. For instance, meteorological data and their time span may restrict the model’s simulation capability. In future studies, efforts should be made to further improve data accuracy and extend the time span, and conduct comprehensive analysis by integrating multi-source data to enhance the accuracy and reliability of the model.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.Y., S.J. and Y.C.; methodology, Q.Y., C.L., Y.L. and W.C.; software, C.L., Y.L. and W.C.; validation, C.L., W.C. and S.J.; formal analysis, Q.Y. and Y.C.; investigation, C.L. and W.C.; resources, C.L., Y.L. and S.J.; data curation, Q.Y. and Y.C.; writing—original draft preparation, S.J., C.L., Y.L. and W.C.; writing—review and editing, Q.Y. and Y.C.; visualization, S.J., W.C. and C.L.; supervision, Q.Y. and Y.C.; project administration, Q.Y.; funding acquisition, Q.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data from this research will be made available upon request to the authors. The data used in this study were obtained from the following platforms: The remote sensing data product MOD17A2H V6.1 dataset released by NASA (https://search.earthdata.nasa.gov (accessed on 15 January 2025)); Loess Science Data Center (http://loess.geodata.cn/ (accessed on 26 December 2024)); and TerraClimate global 0.05° VPD dataset (https://climatedataguide.ucar.edu (accessed on 10 December 2024)).

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to the data support from “The remote sensing data product MOD17A2H V6.1 dataset released by NASA (https://search.earthdata.nasa.gov (accessed on 15 January 2025)); Loess Science Data Center (http://loess.geodata.cn/ (accessed on 26 December 2024)); and TerraClimate global 0.05° VPD dataset (https://climatedataguide.ucar.edu (accessed on 10 December 2024))”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yang, J.; Lu, H.; Ma, Z.; Lu, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhu, J.; Wu, C.; Zhu, H.; Chen, M.; Sun, Y. Predicting CO2 emissions through partitioned land use change simulations considering urban hierarchy. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2024, 17, 2405541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Guo, S.; Yang, C.; Yuan, B.; Li, C.; Pan, X.; Tang, P.; Du, P. Influence of urban functional zone change on land surface temperature using multi-source geospatial data: A case study in Nanjing City, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 115, 105874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lixin, W. Paris Agreement: A roadmap to tackle climate and environment challenges. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2016, 3, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doblas-Reyes, F.J.; Sorensson, A.; Almazroui, M.; Dosio, A.; Gutowski, W.J.; Haarsma, R.; Hamdi, R.; Hewitson, B.; Kwon, W.-T.; Lamptey, B. Linking Global to Regional Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Coops, N.C.; Ferster, C.J.; Waring, R.H.; Nightingale, J. Comparison of three models for predicting gross primary production across and within forested ecoregions in the contiguous United States. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 113, 680–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, S.; Keenan, T.F.; Fisher, J.B.; Baldocchi, D.D.; Desai, A.R.; Richardson, A.D.; Scott, R.L.; Law, B.E.; Litvak, M.E.; Brunsell, N.A.; et al. Warm spring reduced carbon cycle impact of the 2012 US summer drought. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 5880–5885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Zhou, G.; Du, H.; Mao, F.; Xu, L.; Li, X.; Liu, L. Combined MODIS land surface temperature and greenness data for modeling vegetation phenology, physiology, and gross primary production in terrestrial ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 726, 137948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swinbank, W. The measurement of vertical transfer of heat and water vapor by eddies in the lower atmosphere. J. Atmos. Sci. 1951, 8, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otaki, E.; Matsui, T. Infrared device for simultaneous measurement of fluctuation of atmosphere CO2 and water vapor. Bound. -Layer Meteorol. 1982, 24, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brach, E.; Desjardins, R.; St Amour, G. Open path CO2 analyser. J. Phys. E Sci. Instrum. 1981, 14, 1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wofsy, S.; Goulden, M.; Munger, J.; Fan, S.-M.; Bakwin, P.; Daube, B.; Bassow, S.; Bazzaz, F. Net exchange of CO2 in a mid-latitude forest. Science 1993, 260, 1314–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieth, H. Modeling the primary productivity of the world. In Primary Productivity of the Biosphere; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1975; pp. 237–263. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, W.; Cai, W.; Liu, D.; Dong, W. Satellite-based vegetation production models of terrestrial ecosystem: An overview. Adv. Earth Sci. 2014, 29, 541–550, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Chen, J.M.; Gonsamo, A.; Zhou, B.; Cao, F.; Yi, Q. A two-leaf rectangular hyperbolic model for estimating GPP across vegetation types and climate conditions. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2014, 119, 1385–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xu, X.; Dong, Z. A GPP assimilation model for the southeastern Tibetan Plateau based on CO2 eddy covariance flux tower and remote sensing data. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2013, 23, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ficklin, D.L.; Manzoni, S.; Wang, L.; Way, D.; Phillips, R.P.; Novick, K.A. Response of ecosystem intrinsic water use efficiency and gross primary productivity to rising vapor pressure deficit. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 074023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Chang, L.; Feng, D. Remote-sensing estimation of vegetation gross primary productivity and its spatiotemporal changes in Qinghai Province from 2000 to 2019. Acta Prataculturae Sin. 2021, 30, 16–27, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, E.; Zhang, C.; Han, Y. Impact of seasonal global land surface temperature (LST) change on gross primary production (GPP) in the early 21st century. Sustain. Cities 2024, 110, 105572. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Zhao, C.; Guo, Z.; Dai, Q.; Pan, Y.; Zheng, Z. Spatio-temporal variation of gross primary productivity and synergistic mechanism of influencing factors in the eight economic zones, China. China Environ. Sci. 2023, 43, 477–487, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.-H.; Liu, X.-F.; Sun, G.-P.; Liang, J. Response of vegetation productivity to drought in the Qinling-Daba Mountains, China from 2001 to 2020. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2022, 33, 2105–2112, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Dong, W.; Guo, X.; Li, D. The terrestrial growth and its relationship with climate in China based on the MODIS data. Acta Ecol. Since 2007, 27, 5086–5092, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Yan, M.; Li, Z.Y.; Tian, X.; Chen, E.X.; Gu, C. Remote sensing estimation of gross primary productivity and its response to climate change in the upstream of Heihe River Basin. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2016, 40, 1–12, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiao, X.; Guanter, L.; Zhou, S.; Ciais, P.; Joiner, J.; Sitch, S.; Wu, X.; Nabel, J.; Dong, J. Precipitation and carbon-water coupling jointly control the interannual variability of global land gross primary production. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 39748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gui-Rui, Y.; Xian-Jin, Z.; Yu-Ling, F.; Hong-Lin, H.; Qiu-Feng, W.; Xue-Fa, W.; Xuan-Ran, L.; Lei-Ming, Z.; Li, Z.; Wen, S.; et al. Spatial patterns and climate drivers of carbon fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems of China. Glob. Change Biol. 2013, 19, 798–810. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Yao, C.; Niu, Y. Risk and countermeasures of global change in ecologically vulnerable regions of China. J. Desert Res. 2022, 42, 148–158, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Yun, N.; Caixia, C. Analysis of the Relationship Between Plant Growth and Moisture Variation in the Desert Area of Hexi Corridor. J. Landsc. Res. 2018, 10, 122–127. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, F.; Wang, C. Climate characteristics and variation in the Qilian Mountains from 1961 to 2022. Arid Zone Res. 2024, 41, 1627–1638, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, P.; Kong, X.; Luo, H.; Li, B.; Wang, Y. Climate change and its runoff response in the middle section of the Qilian Mountains in the past 60 years. Arid Land Geogr. 2020, 43, 1192–1201, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Sen, P.K. Estimates of the regression coefficient based on Kendall’s tau. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1968, 63, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, M.G. Rank Correlation Methods; Charles Griffin: London, UK, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, H.B. Nonparametric tests against trend. Econom. J. Econom. Soc. 1945, 13, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legates, D.R.; Outcalt, S.I. Detection of climate transitions and discontinuities by Hurst rescaling. Int. J. Clim. 2021, 42, 4753–4772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, H.; Mestre, O.; Venema, V. Fewer jumps, less memory: Homogenized temperature records and long memory. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2008, 113, D19110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Ding, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, Z. 1 km monthly temperature and precipitation dataset for China from 1901 to 2017. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2019, 11, 1931–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, S.; Wang, Q. Estimation for a class of linear regression models. J. Cent. China Norm. Univ. 2021, 55, 351–355, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Christian, K.; Patrick, M.; Erika, H. Four ways to define the growing season. Ecol. Lett. 2023, 26, 1277–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Sun, J.; Cheng, G.; Jiang, H. Effect of altitude and latitude on surface air temperature across the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Mt. Sci. 2011, 8, 808–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Che, T.; Dai, L.; Jiang, Y. Comparative analysis on the spatiotemporal changes of vegetation and drivers in inland river basins of the Hexi Corridor, China. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 8112–8124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Yong, B. Downscaling the GPM-based satellite precipitation retrievals using gradient boosting decision tree approach over Mainland China. J. Hydrol. 2021, 602, 126803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.Z.; Ren, H.; Du, J.; Yang, R.; Yang, Q.; Liu, H. Thoughts and suggestions on oasis ecological construction and agricultural development in Hexi Corridor. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2023, 38, 424–434, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Liu, S.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, B.; Wan, X. Dynamic Changes and Driving Factors of Oasis in Hexi Corridor. J. Desert Res. 2019, 39, 212–219, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Ju, W.; Qiu, B.; Zhang, Z. Tracking the seasonal and inter-annual variations of global gross primary production during last four decades using satellite near-infrared reflectance data. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 755, 142569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goulden, M.L.; Anderson, R.G.; Bales, R.C.; Kelly, A.E.; Meadows, M.; Winston, G.C. Evapotranspiration along an elevation gradient in California’s Sierra Nevada. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences 2012, 117, G03028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Guo, J.; Shen, Y. Spatiotemporal Evolution and Impact Mechanisms of Gross Primary Productivity in Tropics. Forests 2024, 15, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.J.; Yang, H.N.; Yang, Y.C.; Wei, W.; Pan, J.H. Spatial-temporal evolution of ecological environment quality in Hexi Corridor based on Coupled Coordination Model. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2020, 30, 102–112, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Kutsch, W.L.; Liu, C.; Hörmann, G.; Herbst, M. Spatial heterogeneity of ecosystem carbon fluxes in a broadleaved forest in Northern Germany. Glob. Change Biol. 2005, 11, 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Sun, R.; Xiao, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, G.; Cui, T.; Wang, J. Estimation of global vegetation productivity from global land surface satellite data. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Saatchi, S.S.; Yang, Y.; Myneni, R.B.; Frankenberg, C.; Chowdhury, D.; Bi, J. Satellite observation of tropical forest seasonality: Spatial patterns of carbon exchange in Amazonia. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 084005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wu, X.; Ma, D.; Wei, C.; Peng, B.; Du, W. Spatiotemporal variation characteristics and influencing factors analysis of the GPP in the Tibetan Plateau. Remote Sens. Technol. Appl. 2024, 39, 727–740, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Ma, D.; Wu, X.; Yin, G.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Tang, R.; Zeng, Q.; Mu, C. Detection, mapping, and interpretation of the main drivers of the Arctic GPP change from 2001 to 2019. Clim. Dyn. 2024, 62, 723–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatriz, M.; Sergio, S.; Manuel, C.; Javier, G.F.; Amparo, G.M. Exploring Ecosystem Functioning in Spain with Gross and Net Primary Production Time Series. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1310. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.; Hu, Y.; Li, X.; Liao, J.; Fu, R.; Hu, Z.; Yang, Y. Spatial pattern of net primary productivity and asymmetric response of precipitation in global grassland ecosystems. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2024, 33, 1827–1836, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Yu, G.; Ge, J.; Sun, X.; Hirano, T.; Saigusa, N.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J. Temperature and precipitation control of the spatial variation of terrestrial ecosystem carbon exchange in the Asian region. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2013, 182, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Ciais, P.; Makowski, D.; Bastos, A.; Stoy, P.C.; Ibrom, A.; Knohl, A.; Migliavacca, M.; Cuntz, M.; Šigut, L. Uncovering the critical soil moisture thresholds of plant water stress for European ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 2111–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, C.; Wang, G.; Yang, Y.; Wu, H.; Wu, H.; Zhang, H.; Xia, Y. Temperature Thresholds for Carbon Flux Variation and Warming-Induced Changes. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2023, 128, e2023JD039747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).