Abstract

Tourism has emerged as a critical economic pillar for many island communities worldwide, transforming their socio-economic structure and land use strategies. However, intensifying typhoons and other extreme climate events pose escalating risks to these communities, demanding adaptive transformations in disaster knowledge systems and risk management strategies. Local disaster knowledge (LDK), as a place-based knowledge system, plays an essential role in shaping adaptive responses and enhancing resilience within these communities. This study investigates the structure and dynamic adaptation paths of local disaster knowledge amid the shift toward tourism-based communities. Using a qualitative approach, this study conducted an in-depth case study on Shengsi Island, China. The findings reveal that LDK exhibits a three-layered structure: deep-intermediate-surface layers. Beliefs constitute the deep core, while social cohesion, risk knowledge and perception form the middle mediating layer. The surface practical layer encompasses early warning systems, anticipatory measures, structural measures, and livelihood adaptation strategies. The interaction among the three layers constitutes the endogenous dynamics driving knowledge adaptation, while macro-level disaster governance and tourism development act as exogenous drivers. Together, these mechanisms facilitate two adaptive pathways: policy-guided structural transformation and tourism-led practical adaptation. This study advances theoretical understanding of LDK by exploring its dynamics in transforming communities, with a framework that can be extrapolated to other disaster risk contexts. It also provides policy-relevant insights for developing disaster resilience and sustainable land use policies in island communities experiencing tourism transformation.

1. Introduction

Tourism has emerged as an increasingly important livelihood strategy for island communities, transforming their economic structures, cultural practices, ecological security, spatial planning, and land use policies [,,]. Despite positive economic effects, transforming into tourism-dependent communities also presents challenges for island socio-ecological systems, among which coping with climate extremes is most critical. For example, as the most prevalent natural disaster affecting coastal regions, typhoons pose severe and intensifying threats to island communities under accelerating climate change [,]. For tourism-dependent communities, typhoon preparedness extends far beyond traditional concerns of community survival and fishing protection to include tourist safety, facility security, landscape protection, and operational continuity [,,,]. This reveals that traditional fishing-based disaster knowledge, while valuable, proves inadequate for addressing tourism-specific vulnerabilities []. Consequently, developing integrated disaster response systems that bridge traditional disaster wisdom with modern tourism demands has become a pressing challenge for transforming island communities.

The local disaster knowledge (LDK) literature, particularly research on knowledge transformation, provides a critical theoretical lens for understanding this phenomenon. LDK refers to place-based understanding of disaster causes, impacts, and response strategies developed through accumulated disaster experience [,,]. Such knowledge enhances community disaster resilience by reflecting localized human–environment–disaster relationships [,,,]. A key characteristic of LDK is its dynamic adaptability. Experience-based social learning [,,], scientific knowledge [,,] and policy interventions [,,] are vital forces that drive LDK adaptation and transformation. With advances in disaster science and forecasting technology, local and scientific knowledge systems increasingly integrate, revitalizing traditional knowledge frameworks [,].

While existing research has identified these social, technological, and political drivers of LDK transformation, community economic transformation remains a significantly underexamined factor. LDK is inherently tied to local industries and community livelihoods, with different economic foundations generating distinct disaster knowledge systems []. This economic embeddedness manifests clearly across community types: traditional fishing communities develop typhoon knowledge centered on wave assessment, boat protection, and timing decisions for sea ventures []; agricultural communities focus on crop protection, drainage systems, and adaptive strategies for crop selection and planting schedules []; while tourism-dependent communities require specialized understanding of tourism facility protection, tourist behavior management and integrated land use strategies [,]. The pathways through which industry-specific knowledge integrates with existing LDK remain a critical research gap.

Moreover, beyond external factors, the internal structure and endogenous dynamics of local knowledge systems themselves also mediate knowledge transformation. LDK is not a unified whole but comprises varied elements, including beliefs, social cohesion, risk perception, and practical practices []. Existing research typically treats these elements as independent components, with limited attention to their interactions. However, these elements are not merely parallel components but form layered structures with functional interdependencies []. For instance, beliefs guide risk perception and practices, while lived experiences reshape risk perception and beliefs []. How this layered structure and inter-element dynamics shape LDK transformation represents a crucial area for deeper investigation.

This study examines the dynamics of LDK in island communities undergoing tourism transformation. Specifically, the following three key questions are addressed: (1) What is the internal structure of LDK? (2) What adaptive changes occur in LDK during the transformation into tourism-dependent communities? (3) What are the pathways through which these changes occur, and how do external drivers and internal dynamics interact within these pathways?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Local Disaster Knowledge

Local disaster knowledge (LDK) constitutes an essential component of local knowledge. As the place-based understandings on disaster causes, impacts, and response strategies, LDK offers a distinctly cultural perspective on human–environment–climate relationships. It helps communities interpret environmental warnings and develop practical responses based on local cultural understanding [,]. For example, “Smong”, a local Simeulue word for the earthquake/tsunami phenomenon, embodies deep social memory that has guided locals’ disaster understanding and evacuation practices for generations [].

LDK’s embeddedness in local context and culture, combined with its conceptual overlap with indigenous and traditional knowledge, creates definitional ambiguity and inconsistent conceptual frameworks. Developing typologies of LDK is therefore essential for advancing theoretical understanding of this knowledge domain. Scholars have proposed various analytical frameworks to classify LDK from different perspectives. Griffin and Barney examined Indonesian volcanic disaster knowledge and distinguished three knowledge systems: everyday functioning of livelihoods; scientific knowledge and local observation of crater activity; cultural-religious interpretations []. Choudhury proposed a comprehensive framework consisting of four components: (1) local knowledge, (2) local strategies for disaster resilience and social learning, (3) social institutions, and (4) worldviews, beliefs, and values []. Through systematic literature review, Hadlos identified seven categories of disaster-related local knowledge: early warning systems, risk knowledge and perception, anticipatory measures, structural measures, livelihood-based adaptation, social cohesion, and beliefs [].

These typologies provide valuable insights for understanding local disaster knowledge. However, existing classifications predominantly treat different LDK dimensions as independent systems, overlooking their interconnections and interactions. In reality, local knowledge is not merely a combination of separate components but exhibits layered structures []. How communities perceive and understand disasters largely determines what practical measures they adopt in disaster response. For example, religious beliefs influence behavioral responses to disasters through disaster awareness and religious support []. Religious beliefs such as “everything is predetermined by God” can reduce risk perception and self-efficacy, fostering fatalistic tendencies and passive behaviors []. Understanding the layered structure of LDK and the interactions between its layers is essential for advancing LDK research.

2.2. Local Knowledge Transformation and Tourism-Based Adaptation

LDK transformation is a central concern in disaster knowledge research. Research on LDK transformation reveals two primary pathways: community-based learning processes and external knowledge integration. Community-based social learning serves as a crucial locally driven pathway for knowledge transformation [,,]. Communities develop and refine their disaster knowledge through ongoing experimentation and innovation across generations of disaster experience. Social learning, i.e., the informal communications and exchange among community members that transform individual experiences into shared understanding accelerates this process [,,]. Communities continuously adapt their knowledge, weaving new insights and lessons from recent experiences into existing frameworks to address changing social and environmental realities [].

Beyond community-based learning, scientific knowledge and policy interventions also drive knowledge accumulation and transformation []. Advances in disaster science and forecasting have increasingly questioned traditional approaches, raising debates about LDK’s reliability and validity in modern disaster management contexts. Research on scientific knowledge’s impact on LDK reveals contested perspectives. Some studies emphasize the complementary potential of scientific knowledge, demonstrating that integrating scientific and local knowledge systems can effectively enhance community disaster resilience [,]. In contrast, others highlight the power imbalances between scientific and local knowledge, arguing that local knowledge is systematically excluded from formal institutions [,].These scholars contend that formal institutions and scientific approaches marginalize traditional knowledge, cautioning that over-reliance on external expertise undermines local capacity and community resilience [,]. Despite this debate, scientific knowledge undeniably drives LDK transformation, as it dissolves, strengthens, or integrates with existing knowledge systems [,,]. Policy changes represent another significant driver of LDK evolution. Disaster governance reforms and institutional changes at higher-level government necessitate corresponding adjustments in local governance systems, thereby reshaping how communities develop, maintain, and apply their disaster knowledge [,]. Ultimately, the interplay among indigenous social and cultural values, scientific knowledge, and institutional arrangements drives the dynamics of LDK.

Despite the merit of these pathways, they prove inadequate for analyzing LDK dynamics in island communities undergoing tourism-driven transformation. This inadequacy is evident in two critical areas. First, both approaches overlook the internal structure and structural dynamics inherent in LDK during transformation processes. These pathways treat LDK as one unified whole and focus primarily on its relationships with external factors, such as social learning [,,], scientific knowledge [,], policy interventions [], and social capital [,]. However, LDK comprises distinct structural components, namely beliefs, relations, and practices, which interact dynamically during transformation. A comprehensive understanding of LDK transformation therefore requires examining not only external influences but also the internal dynamics among these structural elements.

Second, existing research insufficiently addresses the economic embeddedness of local disaster knowledge. Current studies have primarily examined how ecological, social, technological, and policy changes challenge established LDK systems, but they have largely overlooked how transformations in leading industries and community livelihood also necessitate adaptive changes in LDK. Tourism-dependent communities exemplify this phenomenon, developing distinctive disaster-related local knowledge tailored to their economic priorities. This tourism-oriented LDK encompasses multiple dimensions: communication strategies for helping visitors adjust travel plans and ensure safety before disasters strike [,]; formal networks (such as industry associations) and informal networks among tourism practitioners [,]; post-disaster destination branding and reconstruction efforts [,]; disaster-prevention tourism infrastructure development and land use planning [,]; and other industry-specific disaster response measures. Despite the significance of these economically driven adaptations, current LDK research frameworks have failed to incorporate such considerations.

To deepen the understanding of LDK dynamics under tourism transformation, this study adopts a two-stage approach. First, we develop a conceptual framework for LDK that identifies the elements and internal structure of LDK based on existing literature. Second, we apply this framework to guide empirical investigation in Shengsi Island, China. Through this integrated approach, we examine changes in LDK during tourism transformation and analyze the pathways through which these changes occur.

2.3. Local Disaster Knowledge Structure and Transformation: A Research Framework

Building upon Hadlos et al.’s [] seven-dimensional typologies and incorporating critical reflections on LDK’s layered structure and internal interactions, this study proposes the following research framework (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A conceptual framework for LDK structure and interaction.

Beliefs form the deep core of LDK, encompassing the fundamental truths that community members hold as valid, significantly shaping their disaster risk perceptions and response behaviors []. Religious beliefs, which include faith in supernatural forces, adherence to religious doctrines, and moral values rooted in spiritual traditions, provide transcendent explanatory frameworks for understanding disasters []. Beyond religious frameworks, reason-based meaning making also influences disaster responses through systematic cognitive processes. These include individuals’ views of nature, causal attributions, cognitive appraisals, and sense-making processes related to natural disasters []. Such reasoning manifests in how community members perceive disaster response responsibilities and allocate trust among different actors []. It further reflects their confidence and determination in disaster coping, particularly their belief that proactive measures can effectively reduce disaster risks [].

Risk knowledge and perception, together with social cohesion constitute the intermediate layer of LDK, linking beliefs and practical knowledge. As a critical component of disaster knowledge, risk knowledge and perception encompass communities’ understanding and interpretation of disaster risks, including magnitude, hazard types, exposure, vulnerability, and coping capacity []. Community members assess the likelihood and potential severity of disaster impact based on their familiarity with local conditions and previous hazard experience [,]. Such accurate hazard assessment serves as the foundation of effective disaster preparedness []. Social cohesion represents an intangible asset activated during crises, manifested through collective community efforts where group interests override individual ones, creating solidarity to collectively address and resolve disasters []. This cohesion operates through both formal community organizations and informal social networks [].

Practical disaster knowledge represents the visible surface of LDK, comprising early warning systems, anticipatory measures, structural measures, and livelihood-based adaptation. Early warning systems include alerts, news, and warning signals that inform at-risk populations, enabling risk perception, preparation, and appropriate action; anticipatory measures involve long-term mitigation strategies and short-term preparedness behaviors that decrease disaster risk, for example, disaster-preventive land use strategies, building reinforcement and tree trimming prior to typhoons; structural measures refer to physical constructions or engineering technologies designed to reduce hazard impacts and enhance system resilience; livelihood adaptation measures help communities maintain sustainable livelihoods when facing disaster risks [].

LDK features a three-layer interactive structure: deep-level beliefs; intermediate-level risk cognition and social cohesion; surface-level practical knowledge. Deep-level beliefs provide the foundational values that maintain stability across intermediate and surface layers while being subtly influenced by practical adjustments and cognitive shifts. Intermediate-level risk perception and social cohesion serve mediating functions, establishing cognitive and relational foundations for practical knowledge. Surface-level practical knowledge demonstrates the highest sensitivity to environmental changes and greatest adaptive capacity. This structural design enables LDK to maintain stability while preserving dynamic adaptability.

3. Methodology

3.1. The Case

Shengsi Archipelago, located in Zhejiang Province, China, is a premier island tourism destination in Eastern China, comprising 404 islands of varying sizes with 16 inhabited islands. Fishing was the dominant industry of Shengsi before tourism, along with subsistence agriculture. Tourism in Shengsi started in the 1980s when the area was designated as a National Archipelago Scenic Area in 1988. The tourism industry, characterized by coastal landscapes, marine culture, seafood, and community-based homestays, began attracting growing numbers of tourists. Tourism growth in Shengsi has transformed the local economy, with most residents shifting from fishing to tourism businesses, particularly homestays. The establishment of the first community-based homestay association in 2009 marked the evolution of accommodation sector from scattered fishing-family guesthouses to organized homestay clusters. Today, nearly every village has its own homestay association, playing a central role in supporting local tourism development. Tourism has become the leading industry in Shengsi, complemented by fishing industry.

Among these islands, Sijiao Island and Huaniao Island stand out as leading tourism destinations, attracting the majority of visitors. Sijiao Island, the largest island in the archipelago, hosts the county’s main population, government departments, and principal tourism facilities. Huaniao Island represents a novel development model, functioning as an integrated scenic area that charges mandatory landing fees. The island has attracted substantial tourist flows in recent years through its high-end homestays and artistic experiences, becoming a new landmark of Shengsi tourism.

However, Shengsi faces frequent typhoon disasters, especially during summer and autumn. The storm surges, heavy rainfall, and strong winds associated with typhoons threaten local infrastructure and residents’ lives. As a tourism destination, the island encounters additional challenges including facility damage, transportation disruptions, tourist evacuations, and revenue losses. Confronting these threats, Shengsi has developed comprehensive typhoon response strategies and local knowledge systems that protect both residents and tourists while enabling rapid recovery. This LDK system effectively reduces typhoon impacts and supports sustainable tourism development. Shengsi Island’s resilience to typhoon demonstrates valuable lessons for island communities transitioning to tourism economies.

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

This study employs a qualitative research approach. Data was collected using non-participant observation, semi-structured interviews and secondary source materials. Non-participant observation focused on local architectural structures, engineering facilities, and homestay operations. Semi-structured interviews explored how the community lives with typhoons before and after tourism development. Specifically, the following information was collected: how the locals prepare for, respond to, and recover from typhoons; how the locals think about and talk about typhoons; how the community members are organized around typhoon; how tourism development influenced their cognitive, relational, practical knowledge on typhoons. Secondary data sources were collected, including local chronicles, disaster management plans and policies, spatial planning documents and land use policies, and tourism development plans.

Two communities were selected as main research sites based on three criteria: their status as popular tourism destinations, regular exposure to typhoon impact, and high concentration of small tourism business. The first site, Jihu Village on Sijiao Island, represents Shengsi’s most established tourism community. As the archipelago’s premier tourism destination, it features the most popular beach, the largest homestay cluster, and served as the birthplace of Shengsi’s first homestay association. Due to its high density of tourism facilities and large visitor numbers, Jihu Village faces critical challenges during typhoon events. The second site, Huaniao Island, represents a rapidly developing tourism community that has experienced significant growth in recent years. Its eastern geographical position makes it more vulnerable to direct typhoon strikes with greater intensity. Like Jihu Village, it experiences substantial typhoon impacts due to its concentrated tourism infrastructure and visitors. Both communities are characterized by a predominance of small businesses, which necessitates community-based disaster response strategies that rely heavily on local knowledge and informal cooperation networks.

The first fieldwork was conducted from August 4 to August 16, 2024, in Jihu Village, Sijiao Island. Fifty-six semi-structured interviews were conducted. Purposive sampling was applied to cover the key groups concerned, which include three groups: (1) tourism practitioners, including homestay owners, managers from formal tourism companies, and hotel staff. Most tourism practitioners on this island are also local residents (E1–E23); (2) local residents not engaged in tourism, such as fishermen, doctors, students, and retired elderly (R1–R15); and (3) key informants, comprising government officials, police officers, community leaders, and homestay association representatives (G1–G18). The second fieldwork was conducted from March 7 to March 10, 2025, on Huaniao Island. A total of 10 interviews were conducted here, including 9 tourism practitioners (E24–E32) and 1 non-tourism resident (R16). In total, 66 interviews were conducted, respondent profiles are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The respondent’s profile.

Data were analyzed using thematic analysis [,], incorporating both inductive and deductive strategies [,]. We adopted the six-step thematic analysis framework proposed by Braun and Clarke []. Analysis began with (1) thorough reading and familiarization with the research material to develop a comprehensive understanding of the dataset; (2) inductive generation of initial codes; (3) sorting and analyzing initial codes for patterns and relationships to generate themes. This process is deductively guided by our initial framework for LDK structure and interaction; (4) reviewing and refining themes through comparison with raw data to ensure internal coherence and external distinctiveness; (5) developing final theme definitions and labels; and (6) selecting representative data extracts to illustrate each theme, integrating analysis with research questions to construct a coherent academic narrative. Sample coding table are presented in Appendix A.

4. LDK and Adaptive Changes

With the development of tourism, typhoon-related local disaster knowledge (LDK) has undergone profound transformation across multiple dimensions (as shown in Table 2). In terms of belief systems, this transformation is primarily manifested in functional transformation of traditional religious beliefs and the emergence of modern disaster worldviews. In traditional fishing communities, religious beliefs, particularly those centered on the Sea Dragon King, served as the cornerstone of the community’s typhoon knowledge system. Before setting out to fish, fishermen would worship the Sea Dragon King, seeking bountiful catches and safe passage. As one bar owner explained: “All fishermen believe in the Sea Dragon King. They set off firecrackers before heading out to fish (E1).” As the fishing industry declined and tourism flourished, religious beliefs gradually lost their dominance in the local typhoon knowledge system but transformed to serve more secularized functions, such as worshiping for good fortune in tourism business.

Table 2.

LDK before and after tourism development in Shengsi Island.

The traditional views of nature, value, and responsibility have transformed to form a modern disaster worldview. This belief system integrates traditional nature views with rational cognitive frameworks, emphasizing evidence-based approaches to nature, risk, life, and responsibility. Traditionally, typhoons were regarded as inevitable and uncertain natural phenomena, with losses considered predestined. With tourism development, the view of typhoons as inevitable and uncertain phenomena persists, but their associated risks are now seen as manageable through effective preparedness measures. Local residents exhibit strong confidence in their ability to manage typhoon-related challenges. Moreover, the value system shifted from prioritizing property and livelihood over personal safety to prioritizing safety with rational risk management. And the view of responsibility evolved from individual–community shared responsibility to government-led tripartite collaboration. Individuals assume primary responsibility for protecting their own lives and property; tourism businesses are accountable for guest safety and destination reputation; while government acts as the ultimate guardian of public safety and tourism market stability.

Risk knowledge and perception have also undergone significant transformation, shifting from experience-based fishing risk to integrated tourism-centered risk awareness. During the traditional fishing era, risk perception was closely tied to fishing livelihoods. The risk awareness was grounded in lived experiences of life-threatening typhoon encounters and the genuine hardships of livelihood asset losses. Risk knowledge also developed around the fishing industry. For example, fishermen predicted typhoon trajectories by observing natural phenomena such as wave surges, cloud formation, and atmospheric changes. Following tourism development, concerns about typhoon risk shifted to the tourism sector. Maritime transportation disruptions that strand tourists, along with direct economic losses due to scenic area closures and unoccupied accommodations, now constitute the primary risk concerns. Traditional empirical knowledge remains vital but now works alongside scientific understanding. Local residents combine scientific forecasts with their knowledge of local geographical features and tourism vulnerabilities to assess typhoon risks.

Changes in social cohesion have manifested as a shift from close mutual assistance within traditional close-knit communities to new forms of cooperation involving multiple stakeholders. Before tourism development, social cohesion within the community was deeply rooted in the fishermen’s tightly bonded social networks. Having engaged in fishing activities together over generations, fishermen developed strong interpersonal relationships and maintained regular, direct communication in their daily lives. When facing typhoon threats, neighbors would voluntarily assist each other in relocating fishing boats, securing fishing equipment, and overcoming challenges. After tourism development, the mechanisms and forms of social cohesion have undergone significant changes. The traditional fishermen’s close-knit community has gradually evolved into a broader “homestay community” that encompasses homestay operators and various other stakeholders. While daily communication has decreased compared to the past and the demand for traditional mutual assistance has declined, new collaborative dynamics have emerged. Social organizations such as volunteer groups and homestay associations now take coordination responsibilities in typhoon preparedness and response. Meanwhile, government-community cooperation has been strengthened. Government agencies and local communities now collaborate in responding to typhoon disasters, creating a new framework of social cohesion that engages multiple stakeholders.

Practical knowledge has undergone continuous tourism-based adaptation and multi-sourced integration. Before tourism development, practical knowledge relied primarily on traditional experience across four key areas: early warning systems based on natural phenomenon observation, comprehensive anticipatory measures for community protection, structural defenses including stone construction and coastal barriers, and livelihood adaptation strategies that capitalized on post-typhoon marine productivity improvements (see Table 2 for detailed measures).

After tourism development, practical knowledge has transformed to integrate modern technology with sustainability principles, traditional experience, and tourism-specific knowledge. This transformation covers four key areas: early warning systems combining modern technology with traditional wisdom; anticipatory measures that reduce damage and balance tourism development with ecosystem preservation; upgraded structural defenses using modern materials and construction techniques; and specialized tourism adaptation strategies focused on visitor safety and destination reputation management (see Table 2). Notably, tourism-related impacts have become central concerns, with detailed attention to scenic area operations, transportation disruptions, and accommodation management.

5. Pathway for LDK Adaptation

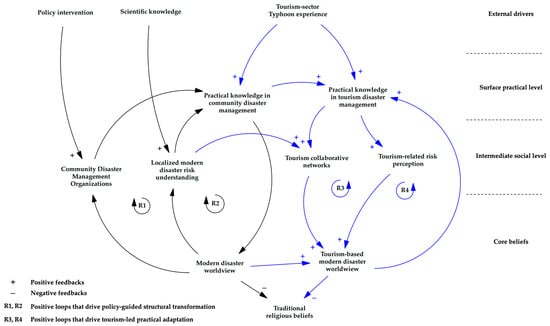

Local knowledge in disaster risk reduction is transformed under the dual influence of policy intervention and tourism development. These external influences activate endogenous dynamics within local knowledge systems to form two adaptive pathways: policy-guided structural transformation and tourism-led practical adaptation. The first pathway is shown in the left part of Figure 2 (in black), it focuses on community disaster management for safety, lifeline supplies, and basic function of the community. The second pathway is shown in the right part of Figure 2 (in blue). It concerns on the tourism disaster management, ensuring tourist safety and industry continuity.

Figure 2.

Causal loop diagram representing the two adaptive pathways for LDK.

5.1. Policy-Guided Structural Transformation

Policy interventions drive LDK transformation. Changes in higher-level disaster management systems and the spread of scientific knowledge directly influence the intermediate level of LDK through grassroots governments, communities, and schools. It is primarily manifested in two aspects.

First, changes in higher-level disaster management systems drive transformations in community disaster management organizations and social-cohesion. China’s disaster management system has undergone multiple improvements since 2000. Two major changes include the emergency management system centered on the “one plan and three systems” established after the 2003 SARS epidemic, and the integrated emergency management system with the establishment of the Ministry of Emergency Management in 2018. These institutional changes cascade through government levels and reach communities through local governments, effectively promoting the standardized development of community disaster management organizations. This includes the formal establishment and stable operation of disaster emergency management teams and volunteer organizations. Notably, community disaster management functions have been integrated into community organizations. Village committees, grid units and homestay associations perform their respective duties during normal times, but when typhoons strike, they quickly combine to form a unified emergency management system.

Second, scientific knowledge has transformed how communities perceive risk. Improved disaster prediction and prevention technologies now reach communities through mobile internet and schools, spreading scientific knowledge about disasters. Notably, communities do not simply adopt this knowledge but blend it with traditional wisdom and local conditions, creating their own risk assessment approaches. For instance, residents combine personal observation with scientific forecasts to evaluate typhoon threats. As one resident explained: “We mostly check our phones now, or the community displays. We get warning several days ahead... But we can also tell from the morning sky. Before a typhoon hits, you’ll see this red glow in the sky. There’s an old saying: ‘Red sky at morning, sailors take warning; red sky at night, sailors delight.’ When we see that red morning sky, we know typhoon’s coming (R16).” Residents also combine their understanding of local social-geographical features with scientific knowledge to identify localized vulnerabilities, such as flood zones, at-risk populations, and affected industries.

Changes in intermediate knowledge system influence the practical surface of LDK. The localized adoption of scientific knowledge altered how communities predict, prepare for, and respond to typhoon disasters. Official warning systems now dominate disaster forecasting because they have proven timelier and more accurate through long-term practice. Residents can receive typhoon updates a week ahead through mobile phones and WeChat groups, tracking storms in real time. But, communities do not simply relay official forecasts. They interpret and share this information in their own way, influenced by local social networks and risk knowledge. For example, locals combine the predicted trajectory, wind direction, and wind speed with local social and geographical features to assess potential risks and take preventive measures accordingly. Moreover, community disaster organizations serve as bridges, connecting scientific forecasting with local communication channels. As one resident explained: “The government sends texts, then village loudspeakers broadcast an alert. After hearing that, we check our phones to see when the typhoon will hit, assess the risk, and decide what we need to do (E1).”

For anticipatory measures, communities blend local experience with scientific knowledge for disaster prevention. Lived experience still plays the leading role in guiding how locals prepare for and mitigate typhoon risk. However, this lived experience is inevitably influenced by scientific knowledge and modern disaster management systems. Scientific knowledge reaches communities through schools and public education. This encourages local residents to reflect on their disaster prevention experience and update their knowledge accordingly. Government and community organizations also provide guidance based on modern disaster prevention criteria, helping residents decide when and how to act. One resident described: “Officers and community leaders check unsafe buildings and give guidance through loudspeakers and text messages... (R15).” The residents are expected to take precautionary measures primarily based on their individual and household experience, supplemented by official risk information, official guidance, and preventative knowledge from schools. Most residents demonstrate the capacity to take proper anticipatory measures.

In terms of structural measures, communities combine traditional knowledge with modern technology to build more resilient infrastructures. Community disaster organizations coordinate this process, supported by the spread of scientific knowledge. Local organizations bring together government technical support, traditional community knowledge, and market resources to improve the resilience of infrastructure. For instance, breakwater heights and building wind resistance are designed using precise meteorological data, so infrastructure keeps its local character while providing modern disaster resilience. A local meteorological bureau staff member explained: “We provide basic weather data, like how many days per year have certain wind speeds. When organizations want buildings designed to withstand Category 17 winds, they specify exact wind pressure requirements for windows. These standards are regulated and account for local typhoon patterns (G5).”

Practical knowledge transformations have changed how local communities perceive typhoons, their value systems, and views of responsibility. Timely and accurate prediction systems, along with effective anticipatory and structural measures, have helped residents understand that typhoons are not mysterious, terrifying forces but predictable natural events whose risks can be understood and managed. As a bar owner explained: “These days, even before a storm becomes a typhoon, the weather station sends us the projected path through our community chat groups. Village staff come around house by house telling us when to close the shop... They even have videos showing us how to stack sandbags properly... Before, we thought typhoons were just God’s punishment. Now we understand that if you pay attention to the warnings and get ready early, you can avoid a lot of damage (E1).” Moreover, long-term prevention practices that prioritize human life over property safety have made “people’s lives first” and “respect and care for life” core community values. A county-level emergency management staff member noted: “there’s a rule ‘even if houses flood, people must stay safe’. No one has been hurt by typhoons in recent years because of this rule (G11).” Meanwhile, people have developed an understanding that individuals and households are primarily responsible for their own safety and property, while the government provides backup support during major disasters. As a respondents explained: “We board up our doors and windows ourselves and stock up on food and water. The government keeps track of tourists who get stuck and helps out if anything goes wrong... There’s insurance if boats get damaged, and the government organizes the rescue teams too (G15).”

5.2. Tourism-Led Practical Adaptation

Typhoon damage to the tourism industry drives LDK adaptation through experiential and reflective processes. Initial changes occur in practical knowledge through “grassroots government-community-tourist” interactions. Regarding early warning systems, tourist safety needs have become a key adaptation driver. Local governments and tourism business owners integrate official warnings with tourist feedback, conducting risk assessments that better reflect local conditions. As a homestay owner explained: “Before a typhoon hits, the association posts weather forecast screenshots in our group chat. We also need to check the situation of our guests. Unlike before when we just went by official notices, now we have to adjust according to what guests actually need (E3).”

In terms of anticipatory measures, government guidance and tourist demand together drive anticipatory measure adjustments, embedding disaster prevention into standard industry practice. Tourism businesses like scenic spots and homestays now integrate disaster prevention into daily operations. A state-owned homestay manager noted: “The Tourism Bureau and association send evacuation notices in advance. We follow procedures: first persuade tourists to leave, then have those who stay sign safety agreements and remind them not to go to the beach... After repeating this process, we now automatically incorporate disaster prevention into operations without supervisor prompting (E20).” Furthermore, tourism development has enhanced recognition of the ecological system’s value both in aesthetic appreciation and typhoon protection. Communities employ strategies such as establishing ecological protection zones, enforcing rigorous coastal land use policies, and implementing coastal habitat restoration initiatives to protect environmental assets creating natural barriers against typhoon hazards. This integrated approach effectively balances tourism economic development, marine and coastal environmental protection, and disaster mitigation.

For structural measures, safety requirements and market demands have worked together to drive tourism facility upgrades. When renovating facilities such as glass walkways in scenic areas and floor-to-ceiling windows in homestays, operators strengthen wind and disaster resistance while maintaining visual appeal, balancing disaster prevention with tourism experience. A manager of a local tourism operator stated: “Our scenic area’s glass starry sky rooms use laminated glass that stays intact even when cracked during typhoons. Tourists can stargaze while the structure resists level 12 winds... Our renovation standard was ‘beautiful and sturdy.’ We can’t just focus on typhoon protection and ruin the scenic experience (E19).”

As for livelihood-based adaptation measures, tourism businesses developed unique business continuity knowledge based on lived experience of dealing with typhoons and interacting with tourists. The key is to take precautionary measures to decrease physical damage and sacrifice economic benefits for tourist safety and satisfaction when necessary. As a homestay owner said: “We persuade tourists to leave before typhoons, even if we lose room fees. If guests stay with nowhere to go, they’ll have bad experiences and leave negative reviews… We need both safety and reputation (E3).” Moreover, tourism business owners developed long-term adaptation strategies based on repeated experience, for example, maintaining long-term reputation and building close relationships with both tourists and the local community.

Adjustments in practical knowledge have transformed how community-level organizations adapt to tourism contexts and how collective risk understanding evolves. This includes incorporating typhoon prevention responsibilities into community tourism organizations such as homestay associations and volunteer groups. During normal periods, these organizations perform their ordinary functions such as promoting industry development. When typhoon strikes, these organizations take on additional responsibilities including tourist communication and safety management, resource integration, and cross-sector coordination. Take the homestay association as an example. When typhoons strike, it coordinates tourist transfers between different homestays, connects businesses with local government, and transfers timely information from local government to homestays. A leader from a homestay association explained: “Before, we just did industry training, but now we regularly work with the government on typhoon evacuations and prevention (G14).”

Meanwhile, traditional kinship networks have expanded into industry collaborative networks. The small-scale mutual assistance that once relied on family and neighborhood connections has evolved into a comprehensive collaborative system. This system now covers scenic spots, homestays, catering businesses, and transportation, achieving a leap from kinship-based mutual aid to industry-wide collaboration. When typhoons strike, industry players can quickly connect to share disaster prevention resources and exchange tourist accommodation information. A representative from the town- level tourism department noted: “The association group includes not only homestay owners but also personnel from public security and market supervision bureaus. During typhoons, if guests at any business need help or encounter problems, we can bring it up in the group and public security will assist. If a restaurant runs out of ingredients, homestays will share their supplies... We used to rely on neighbors for help, but now the entire industry supports each other (G2).”

The intermediate-level knowledge system further influences the community’s deep beliefs. In terms of views on nature, lived experience of dealing with typhoons as tourism operators has made the community realize that livelihood risks from typhoons are not only linked to traditional fishing but also closely tied to the tourism economy. The notion that “tourism is an industry that depends on weather” has gradually become widely accepted. A homestay owner frankly stated: “When a typhoon comes, tourists cannot arrive on the island and all bookings are canceled... Previously, I only knew that fishermen feared typhoons. Now that I run a homestay, I realize tourism is more closely tied to typhoons (E3).”

Regarding value systems, the principle of “safety first” has evolved from general human safety concerns to specifically prioritizing “tourist safety first.” The community places tourist safety at the core of tourism operations. As leader from a homestay association said: “No matter how strong the typhoon is, our priority is to ensure the safety of tourists… Making money is secondary; if tourist safety is compromised, the homestay’s reputation will suffer (G13)”.

In terms of responsibility, the shift from traditional kinship networks to community-led collaborative industry networks has enhanced the sense of “shared responsibility”. Tourism business owners, community organizations, tourism agencies, and local governments share a mutual understanding of their roles during typhoons. Tourism businesses bear primary responsibility for the safety of tourism facilities and tourists, while community tourism organizations offer guidance to these businesses, and local businesses ensure public safety and essential support. A respondent from a tourism business stated, “Scenic spots reinforce their facilities, homestays persuade tourists to evacuate, and the government coordinates additional boat trips and distributes typhoon prevention materials... We businesses fulfill our respective responsibilities while the government acts as the safety net. No party can be absent during a typhoon. This is the principle we’ve established over the years (E19).”

5.3. Mutual Support Between the Two Adaptive Pathways

In Figure 2, the two adaptive pathways differ in their drivers, directions, and main functions. Specifically, the policy-guided structural transformation is driven by higher-level policy interventions, which stimulate the dynamics of “intermediate layer → practical surface → deep belief → intermediate layer,” ultimately achieving adaptive transformation in LDK. This adaptation primarily focuses on the safety of community residents, the stability of essential resource supply, and the well-being of local people. In contrast, tourism-led practical adaptation begins with the shock of typhoons on the tourism industry, which triggers an endogenous dynamic of “practical surface → intermediate layer → deep belief → practical surface” to realize adaptive transformation in LDK. This adaptation mainly centers around the safety of tourists and the sustainability of the tourism economy.

However, the two adaptive pathways are interconnected, primarily because the policy-guided structural transformation provides a foundation for the tourism-led practical adaptation. At the practical knowledge level, advancements in early warning technologies and localized understanding offer references for risk assessment in tourism contexts, while the enhancement of community infrastructure resilience significantly ensures the safety of tourists during typhoons. At the intermediate level, reforms in community organizations directly encourage changes in tourism community organizations, successfully integrating tourism disaster management into local organizations and social structures. Furthermore, the localized dissemination of scientific knowledge aids tourism practitioners in identifying potential threats posed by typhoons to areas such as homestay operations and revenue from scenic spots. At the deep belief level, the community’s belief that “risks are preventable and controllable”, along with the value of “safety first” and the concept of “shared responsibility” have become the core foundation for tourism disaster prevention. This has fostered the establishment of a common understanding regarding tourism disaster management.

6. Conclusions and Discussion

Using Shengsi Island as a case study, this research reveals the dynamics and adaptive pathways of LDK during tourism transformation. The findings show that LDK operates through a three-tier structure: beliefs form the knowledge core, social cohesion and risk perception constitute the intermediate layer, and practical measures (early warning systems, anticipatory actions, structural measures, and livelihood-based adaptation) comprise the surface layer. In the process of transforming from a traditional fishing community to a tourism community, Shengsi updated its LDK system. The key adaptive changes include: (1) the functional transformation of religious beliefs alongside the development of a modern disaster worldview; (2) the shift from kinship-based mutual aid to a collaborative network centered around tourism; (3) the refinement of risk knowledge and perception based on scientific knowledge and tourism risks; and (4) the integration of tourism practices with traditional disaster prevention strategies that transforms long-term ecological mitigation and land use strategies alongside short-term preparedness behaviors.

Interactions across the three tiers create endogenous dynamics for LDK adaptation, while external factors such as policy interventions and accumulated typhoon experiences from tourism industry provide exogenous driving forces. This results in the emergence of two adaptive pathways. The first pathway is policy-guided structural transformation, which occurs when higher-level policy interventions drive social reorganization and knowledge integration. This process renders practices more scientific and then modernizes traditional beliefs. The second pathway is tourism-led practical adaptation, which begins with communities adjusting their typhoon responses to meet industry demands. This strengthens organizational capacity and risk awareness, while gradually updating their belief systems through reflections on experiences.

The endogenous dynamics of these two pathways differ, as the first pathway begins with the intermediate layer while the second pathway starts with the practical layer. This highlights the complexity and vitality of the endogenous dynamics of LDK. At the same time, these two pathways are complementary and equally essential. Together, they create an adaptive LDK system where community disaster prevention knowledge serves as the foundation, while tourism-oriented knowledge drives continuous innovation.

6.1. Theoretical Implication

This study makes several theoretical contributions. First, it proposes a three-tier layered framework for LDK. This framework moves beyond previous research that viewed local knowledge as either holistic cultural concepts or fragmented elements [,]. While Hadlos’s seven categories of disaster-related local knowledge are comprehensive, they fail to capture the interactions between LDK elements and their endogenous dynamics []. Our framework addresses this gap by proposing a layered and interrelated structure for understanding LDK. The Shengsi Island case demonstrates that LDK elements are interconnected and mutually reinforcing, generating endogenous dynamics for adaptation. Rather than responding passively to policy interventions and tourism development, Shengsi Island’s LDK actively self-reorganizes to maintain effectiveness across changing contexts. This layered framework offers clearer insights for understanding knowledge transformation in diverse settings, particularly in disaster risk reduction, climate adaptation, and community resilience research.

Second, this research advances understanding of local knowledge dynamics by identifying two adaptive transformation pathways. While scholars have extensively studied scientific knowledge [], social learning processes [], and social capital influences [] as driving forces for local knowledge evolution, less attention has been paid to how these factors interact with layered elements of LDK. This study addresses this gap by revealing how external influences activate endogenous dynamics within local knowledge systems, providing new theoretical insights into adaptive knowledge transformation.

Importantly, this research identifies how economic transformation shapes local knowledge evolution, moving beyond conventional focus on ecological, technological [,], social [,] and policy influences [,]. The Shengsi Island case reveals that transitioning from fishing to tourism fundamentally altered how knowledge is created and valued. This transformation encompasses shifts in disaster risk perception, community organizational structures, land planning and utilization practices, and ecosystem protection. This shift demonstrates how economic transformation activates internal knowledge adaptation, offering new insights into the dynamic relationship between traditional knowledge and industrial change.

6.2. Practical Implication

These findings offer practical implications for improving disaster resilience and sustainable land use of island tourism communities. First, to improve community disaster resilience, community leaders and local managers should facilitate the integration of local expertise with scientific forecasting systems. For example, our study revealed that experienced fishermen in Shengsi can identify approaching storms by observing wave patterns, cloud formations, and sky color changes. Additionally, the locals can combine official forecasts with local geographical and industrial conditions when assessing disaster risk. This traditional knowledge should be valued and maintained. We recommend establishing a structured knowledge-sharing mechanism where these experienced practitioners train both younger community members and tourism operators through regular workshops organized by the community tourism association. Furthermore, these localized experiences should be systematically documented and integrated into the island’s tourism risk management protocols, enabling tourism business owners to make more informed decisions about operational safety.

Second, to build tourism-specific disaster resilience, communities should develop tourism-focused disaster preparedness measures: (1) Tourist communication: homestay owners serve a critical role in disseminating early warning and risk information to tourists. Destination managers should consider and incorporate homestay owners into risk information platforms. A platform that integrates official channels, social media platforms, and homestay owners can provide accurate and timely information for tourist; (2) Infrastructure upgrades: Enhance vulnerable tourism facilities by reinforcing glass facades in hotels and homestays, and adopt ecosystem-based solutions to decrease disaster risk and improve recreational value; (3) Business continuity planning: Train tourism operators to manage stranded visitors effectively, including emergency accommodation protocols and coordinated resource sharing that maintains service quality during disasters.

Third, sustainable land use strategy is a critical component of LDK. Community leaders and local policymakers should consider local culture, traditional land use wisdom, and local industrial characteristics and community needs when formulating land policies. For example, through coastal protection and beach restoration, communities can protect ecological environments, establish natural disaster barriers, and provide landscape value that benefits tourism development. However, special attention must be paid to coastal building controls to ensure that tourism economic development does not sacrifice ecological resources and buffering capabilities.

6.3. Limitation and Future Studies

This study has limitations. First, the cultural–political context of Shengsi Island, characterized by high levels of trust in government, community, and neighbors, may have facilitated social cohesion’s mediating role. These findings require validation across diverse socio-cultural settings. Second, tourists are critical stakeholders whose risk perceptions, knowledge levels, and responses to local prevention measures require deeper examination. Third, existing LDK may face challenges in climate change scenarios. However, this point was not explored in depth in our study because evidence of climate change impacts has not been widely perceived on Shengsi Island. Future research should pursue three directions. First, conduct comparative studies across tourism communities with different cultural backgrounds and disaster types to identify how context shapes knowledge adaptation patterns. Communities experiencing other types of economic transformation also deserve more research attention. Second, investigate the interaction between tourist knowledge and LDK, specifically how these two knowledge systems co-evolve. Third, explore the role and dynamics of LDK in climate change scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.C. and Q.Z.; methodology, F.C. and Q.Z.; formal analysis, F.C. and Q.Z.; investigation, Q.Z.; resources, F.C.; writing—original draft preparation, F.C. and Q.Z.; writing—review and editing, F.C.; visualization, F.C.; supervision, F.C.; project administration, F.C.; funding acquisition, F.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 42301271; the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, grant number 2242025S30055.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Appendix A. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LDK | Local disaster knowledge |

Appendix A. Samples of Coding Table

Table A1.

Fishing stage.

Table A1.

Fishing stage.

| Text | Codes | Subthemes | Themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sea Dragon King and Mazu belief | Religious Beliefs | Beliefs |

| Buddhism belief | ||

| Inevitable and uncertain natural phenomena | View of Nature | |

| Livelihood and property protection over personal safety | Value system | |

| Individual–community shared responsibility | View of Responsibility | |

| Experiential knowledge | Risk knowledge | Risk knowledge and perception |

| Direct impacts on fishing livelihoods and personal property | Risk perception | |

| Acquaintance-based community networks among fishermen | Social networks | Social cohesion |

| Frequent information sharing | Collective efforts | |

| High demand for typhoon preparedness collaboration | ||

| Traditional prediction techniques | Early warning system | Practical knowledge |

| Traditional dissemination techniques | ||

| Preparedness measures | Anticipatory measures | |

| Ecological mitigation measures | ||

| Stone houses | Structural measures | |

| Breakwaters with earth-rock structures | ||

| Resume fishing immediately after typhoons to capitalize on improved marine conditions | Livelihood Adaptation Measures |

Table A2.

Tourism stage.

Table A2.

Tourism stage.

| Text | Codes | Subthemes | Themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Popularization of Guanyin worship and its functional transformation for tourism | Religious Beliefs | Beliefs |

| Inevitable and uncertain natural phenomena | View of Nature | |

| Controllable risk | ||

| Personal safety prioritization | Value system | |

| Property risk tolerance | ||

| Government-led collaborative responsibility | View of Responsibility | |

| Scientific response | Risk knowledge | Risk knowledge and perception |

| Experience-based knowledge transformation | ||

| Tourism industry losses | Risk perception | |

| Tourism-oriented homestay networks | Social networks | Social cohesion |

| Enhanced government-community collaboration | Collective efforts | |

| Reduced traditional mutual assistance reliance | ||

| Emergence of specialized groups | ||

| Modern meteorological technologies | Early warning system | Practical knowledge |

| Modern communication technologies | ||

| Preparedness measures | Anticipatory measures | |

| Ecological mitigation measures | ||

| Continued use of stone houses | Structural measures | |

| Construction material upgrade | ||

| Business continuity | Livelihood Adaptation Measures | |

| Long-term adaptation |

References

- Fan, H.; Li, L.; Zhang, Z. Temporal and Spatial Differentiation and Formation Mechanisms of Island Settlement Landscapes in Response to Rural Livelihood Transformation: A Case Study of the Southeast Coast of China. Land 2025, 14, 1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikjoo, A.; Seyfi, S.; Saarinen, J. Tourism as a Catalyst for Socio-Political Change. Tour. Geogr. 2025, 27, 333–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristić, V.; Trišić, I.; Štetić, S.; Maksin, M.; Nechita, F.; Candrea, A.N.; Pavlović, M.; Hertanu, A. Institutional, Ecological, Economic, and Socio-Cultural Sustainability—Evidence from Ponjavica Nature Park. Land 2024, 13, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC (Ed.) Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis; Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- WMO. Atlas of Mortality and Economic Losses from Weather, Climate and Water-Related Hazards (1970–2021); WMO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.; Xu, H.; Dai, S.; Rao, Y. The Resilience of Coastal Urban Destinations to Typhoons: Insights from a System–Agent–Institution Framework. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Xu, H. Social Learning for Disaster-Resilient Urban Destinations: Dual-Path Knowledge Co-Production and Bridging Organizations. Tour. Geogr. 2025, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonau, V.; De Coteau, D. Tourism Resilience in the Context of Integrated Destination and Disaster Management (DM2 ). Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 22, 202–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Moyle, B.; Dupré, K.; Lohmann, G.; Desha, C.; MacKenzie, I. Tourism and Natural Disaster Management: A Systematic Narrative Review. Tour. Rev. 2023, 78, 1466–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadlos, A.; Opdyke, A.; Hadigheh, S.A. Where Does Local and Indigenous Knowledge in Disaster Risk Reduction Go from Here? A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 79, 103160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarudin, K.H.; Rashid, M.F.; Omar Chong, N. Local Community Knowledge for Flood Resilience: A Case Study from East Coast Malaysia. Int. J. Built Environ. Sustain. 2022, 9, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyoda, Y.; Tanwattana, P. Extracting Local Disaster Knowledge through Gamification in a Flood Management Model Community in Thailand. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2023, 20, 100294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahavacharin, A.; Likitswat, F.; Irvine, K.N.; Teang, L. Community-Based Resilience Analysis (CoBRA) to Hazard Disruption: Case Study of a Peri-Urban Agricultural Community in Thailand. Land 2024, 13, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, D.; Gorman, J. Acknowledging Landscape Connection: Using Sense of Place and Cultural and Customary Landscape Management to Enhance Landscape Ecological Theoretical Frameworks. Land 2023, 12, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šakić Trogrlić, R.; Duncan, M.; Wright, G.; Van Den Homberg, M.; Adeloye, A.; Mwale, F. Why Does Community-Based Disaster Risk Reduction Fail to Learn from Local Knowledge? Experiences from Malawi. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 83, 103405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, C.E.; Azad, M.A.K.; Choudhury, M.-U.-I. Social Learning, Innovative Adaptation and Community Resilience to Disasters: The Case of Flash Floods in Bangladesh. Disaster Prev. Manag. Int. J. 2022, 31, 601–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Hu, J.; Song, X.; Li, Z.; Yang, K.; Sha, Y. How Does Social Learning Facilitate Urban Disaster Resilience? A Systematic Review. Environ. Hazards 2020, 19, 107–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, G.B.; Redpath, S.M.; Wilson, M.; Wernham, C.; Young, J.C. Integrating Scientific and Local Knowledge to Address Conservation Conflicts: Towards a Practical Framework Based on Lessons Learned from a Scottish Case Study. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 107, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.-S.S.; Chang, K.-M. Metamorphosis from Local Knowledge to Involuted Disaster Knowledge for Disaster Governance in a Landslide-Prone Tribal Community in Taiwan. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 42, 101339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, J.; Kelman, I.; Taranis, L.; Suchet-Pearson, S. Framework for Integrating Indigenous and Scientific Knowledge for Disaster Risk Reduction. Disasters 2010, 34, 214–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adomah Bempah, S.; Olav Øyhus, A. The Role of Social Perception in Disaster Risk Reduction: Beliefs, Perception, and Attitudes Regarding Flood Disasters in Communities along the Volta River, Ghana. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017, 23, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setten, G.; Lein, H. “We Draw on What We Know Anyway”: The Meaning and Role of Local Knowledge in Natural Hazard Management. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2019, 38, 101184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Xu, N.; Fan, C.; Fan, Y.; He, S.; Jiao, L.; Ma, N. The Role of Indigenous Knowledge in Integrating Scientific and Indigenous Knowledge for Community-Based Disaster Risk Reduction: A Case of Haikou Village in Ningxia, China. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2019, 41, 101309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, M.; Ross, H.; Berkes, F. Interactions between Individual, Household, and Fishing Community Resilience in Southeast Brazil. Ecol. Soc. 2019, 24, art2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šūmane, S.; Kunda, I.; Knickel, K.; Strauss, A.; Tisenkopfs, T.; Rios, I.D.I.; Rivera, M.; Chebach, T.; Ashkenazy, A. Local and Farmers’ Knowledge Matters! How Integrating Informal and Formal Knowledge Enhances Sustainable and Resilient Agriculture. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 59, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, S.; Sun, J. Governance of Natural Environment through Local Knowledge in Ethnic Tourism Villages. Tour. Trib. 2021, 36, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Deng, Y.; Qi, W. Two Impact Pathways from Religious Belief to Public Disaster Response: Findings from a Literature Review. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 27, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurnio, H.; Fekete, A.; Naz, F.; Norf, C.; Jüpner, R. Resilience Learning and Indigenous Knowledge of Earthquake Risk in Indonesia. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 62, 102423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhou, W.; Tao, C. The Value of Traditional Ecological Knowledge in Stormwater Management: A Case Study of a Traditional Village. Land 2024, 13, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, S.A.; Paton, D.; Buergelt, P.; Meilianda, E.; Sagala, S. What’s in a Name? “Smong” and the Sustaining of Risk Communication and DRR Behaviours as Evocation Fades. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 44, 101408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, C.; Barney, K. Local Disaster Knowledge: Towards a Plural Understanding of Volcanic Disasters in Central Java’s Highlands, Indonesia. Geogr. J. 2021, 187, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, M.-U.-I.; Haque, C.E.; Nishat, A.; Byrne, S. Social Learning for Building Community Resilience to Cyclones: Role of Indigenous and Local Knowledge, Power, and Institutions in Coastal Bangladesh. Ecol. Soc. 2021, 26, art5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kraker, J. Social Learning for Resilience in Social–Ecological Systems. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 28, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, L.; Holmes, A.; Quinn, N.; Cobbing, P. ‘Learning for Resilience’: Developing Community Capital through Flood Action Groups in Urban Flood Risk Settings with Lower Social Capital. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 27, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperiale, A.J.; Vanclay, F. Conceptualizing Community Resilience and the Social Dimensions of Risk to Overcome Barriers to Disaster Risk Reduction and Sustainable Development. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 891–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, D.P.; Meyer, M.A. Social Capital and Community Resilience. Am. Behav. Sci. 2015, 59, 254–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasanayaka, U.; Matsuda, Y. Role of Social Capital in Local Knowledge Evolution and Transfer in a Network of Rural Communities Coping with Landslide Disasters in Sri Lanka. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 67, 102630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, B.W.; Jiang, Y. A Review of Research on Tourism Risk, Crisis and Disaster Management: Launching the Annals of Tourism Research Curated Collection on Tourism Risk, Crisis and Disaster Management. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 79, 102812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, L.D.Q.; Coles, T.; Ritchie, B.W.; Wang, J. Building Business Resilience to External Shocks: Conceptualising the Role of Social Networks to Small Tourism & Hospitality Businesses. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 48, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.L. Meaning Making in the Context of Disasters. J. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 72, 1234–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callaham, S.; Mah, A.; Markowitz, E. Beliefs That Predict Support for Needs-Based Disaster Aid Distribution. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 114, 104967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, T.N.; Leander-Griffith, M.; Harp, V.; Cioffi, J.P. Influences of Preparedness Knowledge and Beliefs on Household Disaster Preparedness. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2015, 64, 965–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odiase, O.; Wilkinson, S.; Neef, A. Risk of a Disaster: Risk Knowledge, Interpretation and Resilience. Jàmbá J. Disaster Risk Stud. 2020, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D.L.; Nica, A. Iterative Thematic Inquiry: A New Method for Analyzing Qualitative Data. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2020, 19, 1609406920955118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).