Abstract

The paper aims to draft how phenomena such as abandonment, territorial disarticulation, environmental pollution, socioeconomic imbalances, and heritage consideration issues that surround landscapes where industrial activity has ceased are reflected on social media in Spain. The research focuses on the most popular social media platforms in Spain: Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter. A manual sample strategy was conducted to ensure an individualized approach to user-generated content. Sampling was carried out separately for three aspects: (1) keywords at a general level, (2) terms used to define industrial landscapes, and (3) recognition of significant industrial landscapes related to governmental facilities built in the 20th century, wherein we take into account three potential profile types: (i) individuals; (ii) NGOs/associations and/or public administrations; and (iii) academics. The results show that social media platforms are widely used as tools to disseminate information about industrial landscapes, but the contributions of each platform are uneven and incomplete in relation to the reality of post-industrial landscapes. However, it is worth recognizing the added value that their possible interaction brings as a reference for current civic debates. How social media contributes toward mitigating the difficulties of recognition, comprehension, and protection of post-industrial landscapes is emphasized in our conclusions.

1. Introduction

The European Landscape Convention (Florence, Council of Europe, 2000) [1] advanced the idea of “landscape” as “any part of the territory as perceived by the population, whose character is the result of the action and interaction of natural and/or human factors...”, summarizing some earlier statements and assertions contained in previous international UNESCO charters and documents. Ideas such as the need to renew heritage concepts through a cross-cutting approach comprise a symbiotic set of natural and cultural elements (tangible and intangible) in which a social group recognizes its identity and is committed to transmitting it to future generations in an improved and enriched way (Conference of Stockholm, 1998) [2].

The European Landscape Convention emphasizes the management of landscape as a favorable economic resource for communities as well as an element of identity, both in spaces of exceptional beauty or in the most ordinary and degraded ones. Hence, the document opens the way to improving and preserving the landscape from cultural, environmental, ecological, and social perspectives. As such, a debate has emerged around industrial and post-industrial landscapes as a type of cultural landscape subject to heritage protection.

The processes of de-industrialization and the consequent possibility of heritage assessment of landscapes resulting from the obsolescence of industry are current phenomena occurring on a global scale [3]. The renovation of both the industrial structure of Southeast Asia [4,5,6] and decarbonization programs for the electricity industry in Western countries [7,8,9] has impelled actions of integration of post-industrial legacy in cultural, urban, and territorial strategies. Given the growing sensitivity toward post-industrial landscapes, it is worth recognizing the spreading acceptance of “factory esthetics” and the “industrial ruin” by disciplines derived from “industrial archeology” [10,11,12,13]. However, do these actions, aimed at preserving the industrial heritage and landscape, respond to the social demand of recognizing productive landscape as part of the community’s cultural heritage? Is it possible to consider a more comprehensive approach to citizens’ sensitivities beyond the administrative procedures or debates covered in the academic media?

As with most landscapes, the approach to industrial landscapes places us at a complex crossroad due to (1) its subjective nature (emotional, mental, or cultural for each individual or social group, sometimes showing polarities in terms of what an inhabitant/visitor perceives and experiences); (2) its heterogeneous classification (depending on each productive sector, the orographic conditions, the climate–environment context, etc.); and (3) its hybrid tangible–intangible dimension and evolutionary and dynamic nature. In this frame, post-industrial landscapes also include those landscapes that lack monumentality, which cannot be catalogued but are part of economic identity and social networks, despite the difficulties of being recognized and comprehended.

On the other hand, if landscape is a cultural construct based on the perception of individuals and society, the final goal of landscape assessment should be to satisfy the needs and interests of the community. This makes it possible to establish a comparison between the objective and technical visions of a landscape and that based on subjective and identity aspects held by societies, which constitute the builders and managers of landscapes whose essence is always to evolve as dynamic and developing organisms [14]. In this context, it is worth reviewing the discussion of the cultural geographer John Brinckerhoff Jackson in his work A Sense of Place, a Sense of Time [15] regarding the need to learn to read the landscape. JB Jackson identified a dichotomy that is still valid among two perspectives: the esthetic approach based on perceptual–visual aspects to landscape endowed with design and artistic qualities versus the phenomenological approach around the development of places based on the uses and customs of their citizens, appropriate for a more autochthonous reading of the landscape and to the recognition of its historical evolution. David Lowenthal’s lessons [16] also have a place in this issue: encouragement of the participatory and creative attitude of citizens in relation to their landscapes, the importance of landscape management policies from local and social identities based not only on the exploration of its growing economic value but also on the reaffirmation of its affective dimension or the collective memory.

The dichotomy inherent to the landscape, between the livable and the visitable, and the contrast between the social memory and the tourist image of landscapes [12], is linked to the selective and subjective character expressed in the reading of the landscape. This phenomenon is especially evident when it comes to highlighting partial images that exclude other realities contained within the same place, or other readings that should be considered. We enter fully into the definition of the social landscape; the landscape as a social and identity construction, not only for the visitor but, above all, for the inhabitant, who becomes an individual and a collective in the midst of a scenario of interaction and otherness among various collectives. The diversity of parallel and non-exclusive symbolic constructions, as well as the spaces in which the collectivity is self-represented, evolves upon all these bases. The new ways for virtually inhabiting, comprehending, and registering a landscape, thanks to the use of new technologies such as Google Maps, Street View, OpenStreetMap, Flickr, or Mapillary, have transformed the traditional essence of the act of viewing a landscape. Social media information plays an important role as an instrument to activate strategies leading to the assessment, protection, and rehabilitation of post-industrial landscapes.

Regarding these arguments, international reference guidelines on industrial heritage also integrate, in their methodological corpus, the attention to citizen participation and the importance of dissemination, as stated in the Nizhny Tagil Charter on Industrial Heritage (2003), derived from the International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage [17]. Likewise, the Dublin Principles for the conservation of industrial heritage sites, structures, areas, and landscapes (ICOMOS/TICCCIH, 2011) [18] confers substantial value to the tasks of documentation and understanding of attributed values to industrial sites, structures, and landscapes by both specialists and communities. Furthermore, the need to support communication aspects through various channels using new technologies is emphasized.

These premises connect with the concept of “digital cultural participation in heritage”, in which new formulas for citizen involvement toward safeguarding cultural heritage are proposed [19,20,21,22] at the same time that they can be inscribed under article 27 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. In the European framework, the Faro Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society [23] encourages participation in cultural heritage activities and fosters the development of heritage-related technologies and digital content, where industrial landscapes should also be recognized. In the Spanish-speaking context, we can highlight, among others, the results of the debate promoted by the 102nd issue of the PH journal [24] that gathered 30 contributions. The PAYSOC project of the Andalusian Historical Heritage Institute has also explored approaches to recognizing cultural landscapes through virtual ethnography [25].

Social media platforms, as the new transnational scope virtual agoras, play a key role in disseminating information, concerns, and interests in contemporary society, as well as in the construction of collective imaginaries, esthetics, and global narratives. There are several academic studies on the role of social media platforms in the dissemination and conservation of cultural and natural heritage [26,27]. However, there are few that specifically determine their contributions to industrial heritage [28,29,30,31,32]. In this sense, the extent to which user-generated content contributes to the growing recognition of the industrial landscape as a heritage resource, similarly to the identification of its elements and values, does not have a consolidated scientific literature. This article is the first to approach the role of social media in the collective cultural construction of the Spanish industrial landscape.

Taking, as a case study, several examples linked to the industrial landscapes generated by the state policy of Francoism (1939–1975) in the 1950s and 1960s, we analyze (1) the characterization of the industrial landscape based on information disseminated through social media (e.g., institutional, partner, or individual channels) to identify the cultural, esthetic, or identity values attributed by community and (2) critical reactions to their distortion or reuse for exploitative purposes.

Considering the post-industrial landscape as part of the identity of regions and their inhabitants [33] as much as the difficulties for their assessment, protection, and management, we aim to conduct a critical analysis of the role of social media as a tool in the identification, assessment, and protection of obsolete industrial landscapes in Spain. How, when, and where are these obsolete industrial sites considered as landscapes of heritage value? How do social networks portray the challenges surrounding the regions where industrial activity has ceased and where issues of abandonment, ruin, territorial disarticulation, environmental pollution, and socioeconomic problems arise? What role do heritage approaches play on public social media debates around deindustrialization? Based on these premises, this study proposes a critical approach on how user-generated content collected on social media can contribute to the construction and dissemination of information in an active and interactive way. In this context, the prevalence of social (i.e., marginalized landscapes) and academic stereotypes (i.e., sublimated landscapes) based on assessments of visual experience stand out, as opposed to other considerations such as environmental, heritage, or social factors.

The role of social media platforms in the cultural revitalization of industrial landscapes is also explored. Despite adverse circumstances, the cultural, historical, technical, or esthetic values attributed to these regions do not disappear, and these are susceptible to sustaining cultural reactivation initiatives capable of offering economic alternatives to the development of inhabited communities [34].

Through the analysis of the information disseminated through social media as a support for opinions and concerns, we seek to answer the following questions:

- -

- What is meant by industrial post-industrial landscapes with regard to the different agents involved?

- -

- Could social media lead to a proactive role in the re-activation of these landscapes to foster the interaction of all involved agents?

- -

- Can user-generated content contribute to the identification of morphological, esthetic, or sociocommunity parameters that suggest guidelines for articulating processes of obsolete industrial landscapes valorization?

- -

- What presence do memory and historical elements of landscape, both geographical and anthropic, have on social media?

2. Materials and Methods

As is well known, social media refer to any digital tools that allow their users to quickly create and share content. Given that this is the first approach to the role of social media in the recognition of the industrial landscape in Spain, and lacking reference papers, we propose to approach the subject, here, by working on some quantitative and qualitative strategies to lay the basis for subsequent, more detailed studies.

In social media, a wide range of websites and applications are used. In this first approach, we selected three of the most used social media platforms in Spain [35]: Instagram, a photo-sharing app; Facebook, a news, information, and audiovisual content-sharing app; and Twitter, an app for sharing short written messages.

Data collection was carried out from mid-September to the end of December 2022 with the aim of outlining the scope of terms related with the industrial landscape, and the profiles and forums in which these concepts are handled, to identify different content offered by the various social media platforms.

Search engine tools and metric analyses of these platforms were consulted directly for keyword and/or hashtag tracking. We employed a manual study strategy in order to ensure an individualized approach to user-generated content and identifying the type of profile of origin and precise context, because this is the most effective way to determine the level of involvement of different culture services of Spanish Public Administrations, which have recently incorporated social media.

To this end, several keywords were monitored following previous studies by Campillo, Ramos, and Castelló [36] and Mariani, Di Felice, and Mura [37] that focused on audience parameters (followers and publications) and the level of user interaction (“likes” and “shares” on Facebook; and reactions, retweets, and comments on Twitter). Sampling was carried out separately for three aspects: (1) keywords at a general level, (2) terms used to define industrial landscapes, and (3) recognition of significant industrial landscapes. In both sampling and results, we took into account three potential profile types: (1) individuals; (2) groups, that could be NGOs/clubs/associations, and/or public administrations; and (3) academics.

2.1. Sampling 1

The first task involved tracking keywords in Spanish relating to both industrial (industrial) and post-industrial (postindustrial) landscapes (paisajes) and heritage (patrimonio). This preview of the subject explored the presence of landscape and industrial heritage references on social media platforms of individuals, public administrations, and NGOs.

2.2. Sampling 2

A second task involved looking for industrial landscape images uploaded to social networks by the three types of profiles mentioned: personal, NGO/association/club and institutional, and academic.

The images were then analyzed using landscape characterization studies, based on López-Sánchez et al. [38], being applied to the three main categories of parameters (e.g., morphological, esthetic–perceptual, and social) that were further subdivided into associated subparameters to draft 17 attributes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Landscape characterization of sampling #2.

2.3. Sampling 3

In a third step, we developed several case studies. Twelve prominent sites were selected (Table 2), linked to industrialization actions promoted by the Spanish government as part of a program of the National Institute of Industry (INI) created in 1941. These hubs were the object of intense public propaganda campaigns in the mid-20th century and the sites had been the subject of previous studies in terms of historical and heritage aspects [39,40,41,42].

Table 2.

Studies sites of sampling #3.

In addition to the National Institute of Industry’s headquarters in Madrid, 5 of the 500 industrial establishments distributed throughout the Iberian Peninsula were selected. The intention was to offer a varied representation of different industrial sectors, regions, and current status. Their company towns were also selected.

We tracked the ongoing echo, on social media platforms (Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter), of these industrial facilities and their adjoining worker settlements. The goal of this sampling was to approach the recognition of the esthetic landscape values attributed to these spaces and, particularly, to the attention they attracted on Instagram. Through our selection of sites, we also sought to trace relationships that remain between the habitats of 20th-century workers and the original productive facilities.

Given the widespread use of company acronyms for the selected facilities, we chose to track these shortened terms instead of the long official names. Company towns were instead sampled on social networks for their popular names.

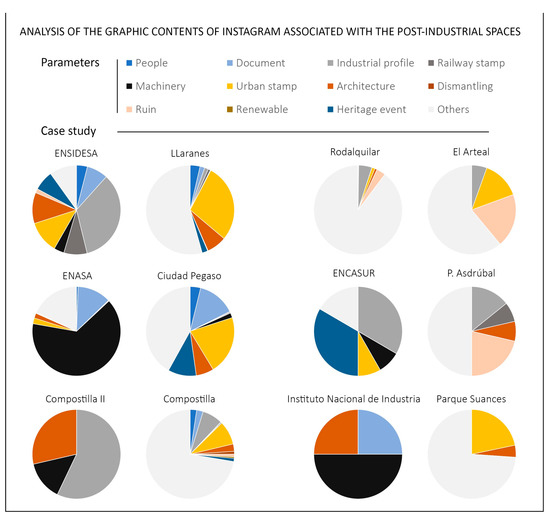

For these industrial hubs, which bring together productive spaces and workers’ habitats, we propose an analysis of the contents with the aim of assessing their degree of recognition. The sampled images are classified according to the following parameters: people, document, industrial profile, railway stamp, machinery and utensils, urban stamp, architecture, dismantling, ruin, renewable, heritage event, or other.

With all the information collected in the three samplings, we conducted a comparative analysis to determine:

- -

- the differences among the three selected profiles;

- -

- what are the most common variables;

- -

- the differences in criteria and content between the different social media platforms.

3. Results

3.1. Sampling #1

Keyword sampling pointed to an uneven diffusion of concepts, as well as the generic use of terms such as “industrial landscape” (paisaje industrial) or “post-industrial landscape” (paisaje postindustrial), and further screening was needed to identify the contents required for our analysis (Table 3). Sampling on the term “heritage” (patrimonio) provided more precise findings. The search was limited by a manual quantitative registration. Ranges, rather than exact figures, are provided in some cases: the lowest value being the one collected by manual registration and the highest value being the one indicated by the platform (usually 1000 in Facebook and 100 in Instagram).

Table 3.

Results of sampling #1 with data relating to tags on the three social media platforms.

More detailed data on the industrial landscape were recorded on the Instagram and Twitter profiles of the public administrations (Table 4). Dissemination was limited to specific sites with figures of cultural protection that are widely recognized; there is surprisingly little mention of hubs registered in the National Plan for Industrial Heritage or the 100 Spanish TICCIH Elements.

Table 4.

Results of sampling #1 for administrative profiles.

Apart from these profiles of cultural services within regional and local administrations, an important number of profiles dedicated to museums and other public entities should be considered. Some examples are La fábrica de la Luz in Ponferrada (Fundación Ciudad de la Energía, @museo_energia), Fundació de la Comunitat Valenciana Patrimoni Industrial i Memòria Obrera de Port de Sagunt (@fcvportdesagunt), and Museu Nacional de la Ciència i la Tècnica de Catalunya (MNACTEC, Generalitat de Catalunya, @MNACTEC).

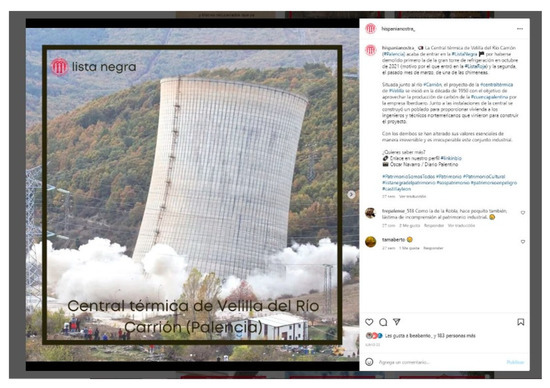

Another important contribution comes from the following associations, with an unequal presence on the various social media platforms: Hispania Nostra (@HispaniaNostra); Asociación Madrid, Ciudadanía y Patrimonio (@madridcyp); Asociación Vasca del Patrimonio Industrial y de la Obra Pública (@AVPIOP); Asociación INCUNA de Patrimonio Industrial (@somos_incuna); etc. Standouts is the specific production dedicated to the enhancement of industrial heritage produced by the project Patrimoniu Industrial de Asturias (@Patrimoniu_Ind) alongside the dissemination work at the citizen level of the architect Diana Sánchez Mustieles PhD (@Patrindustrial). It is also worth highlighting the echo and dissemination of the elements inscribed on the Spanish Architectural Heritage Red List of endangered assets, carried out by Hispania Nostra (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Hispania Nostra’s Instagram post about the demolition of the cooling tower of the Velilla del Río Carrión thermal power plant.

Actions against of the demolition of ENEL-ENDESA’s thermal power plants in Andorra first (February 2021) and Compostilla later (December 2022) generated a significant volume of content related to the defense of distinctive elements of the landscape on individual accounts, NGOs/associations/clubs, or informal civic groups, with a notable echo on Facebook and Twitter. This brought together different profiles across media, public administrations, political parties and civic associations, public representatives, experts, and citizens. Additionally, the active role of Twitter is relevant in the dissemination of news and statements by the agents involved in the process of enlisting the cooling towers and chimneys of Compostilla II based on their landscape value, at the request of citizens’ groups. There is also certain controversy on Twitter around the demolition of the Meirama thermal power plant (Cerceda, Galicia). The support shown by environmental groups such as Greenpeace Spain (@greenpeace_esp) in favor of the demolition had an important echo. Such a position is contrary to complaints from cultural heritage defense groups such as APATRIGAL (@apatrigal). Another example of citizen actions in favor of industrial heritage with an important echo on social media platforms is that of the Plataforma en defensa de la Fábrica de Armas de la Vega (@SalvemosVega). This is an initiative that calls for the modification of the urban integration project of this former weapons factory linked to INI, and the preservation of its values and heritage elements.

In addition to numerous discussion groups that can be found on Facebook, this social media platform has been identified as an important content niche for historical documentation and dissemination of regional community memory. There are numerous groups disseminating historical photographs, documentation, and information about industrial legacy or specific regional areas.

3.2. Sampling #2

Up to 50 tweets that incorporate photographs or videos were selected from conversations about industrial heritage. Table 5 shows some illustrative examples of various recognizable profiles. Each of the selected photographs (and/or comments) was labeled with a maximum of 4 variables among the 17 possible. In general, the esthetic–perceptive and social categories are widely represented; the attributes of collective memory, historicity, and heritage are the most frequent.

Table 5.

Analysis of public publications (tweets) from Twitter.

3.3. Sampling #3

The dissemination of content about hubs linked to INI, and the terms proposed at the beginning of this article as the basis of the case study, shows notable differences according to the type of social media platform (Table 6).

Table 6.

Results of sampling #2.

The National Institute of Industry does not offer too many results and barely has a presence on Instagram. It is only mentioned on Twitter and Facebook as a historical reference, or in conversations with a strong political meaning with hardly any allusions to landscape legacy or graphic references.

In the case of ENDESA (an acronym for the former National Electricity Company, active between 1944 and 1998), a detailed analysis was discarded given the high volume of content still associated with corporate advertising of the ENEL group in which it is integrated. Instead, we chose to explore two iconic production centers: the thermal power stations of Compostilla II (León) and Andorra (Teruel). Compostilla II offers different results depending on the social media platform; a notable echo about its landscape and heritage value is found especially on Twitter as a result of the controversy about its imminent demolition. Similar results were found in the case of Andorra (ENEL-ENDESA), with limited presence on Instagram compared with the broad debate on Facebook and Twitter (Table 7). Abundant content can also be found in inhabited urban hubs, such as the company towns of Compostilla, Llaranes, and Ciudad Pegaso.

Table 7.

Comparison of results between 2 ENEL-ENDESA thermal power plants subject to citizen-driven heritage processes.

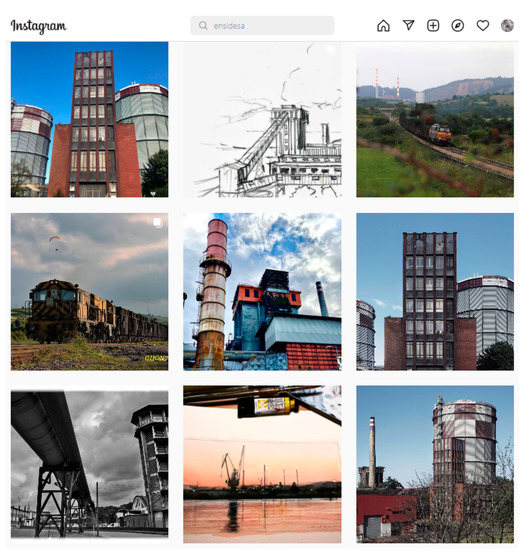

Based on the specific study carried out on Instagram, a reduced presence of industrial production spaces located in rural areas outside tourist circuits is observed (Compostilla; Andorra; ENCASUR; Arteal; etc.). This limited presence contrasts with that of urban production facilities with recognizable urban profiles, such as ENSIDESA (Table 8). Spaces such as the Rodalquilar Mines, inscribed in tourist areas with a consolidated brand image and formal heritage recognition, enjoy notable diffusion. Much of the Instagram content related to the inhabited company towns of Compostilla, Ciudad Pegaso, and Llaranes could be aligned with landscape and heritage sensitivities (Figure 2).

Table 8.

Results of sampling #3, with image numbers for each case study.

Figure 2.

Pie charts relating to public content of the selected case studies found on Instagram.

3.4. Synthesis

The global results show that:

There is participation, via personal profiles, in debates about the loss of heritage and/or its degradation. The following factors tend to dominate: social aspects, dissemination of historical content, and oral memory.

NGOs/associations/clubs and expert profiles contribute to debates and complaints. They also disseminate information campaigns about industrial spaces or elements and examples of conservation and rehabilitation. Social and morphological aspects predominate, with an emphasis on community memory or complaints. Environmental and pollution issues are not usually featured in discussions about industrial heritage conservation; this is not the case for ecologist associations that support decommissioning programs.

Institutional profiles of cultural administration services are scarce and limited to discussing specific events. They are not particularly active in issues related to industrial heritage. Administrations responsible for heritage issues tend to focus on disseminating recurring content on landscapes or assets with a consolidated trajectory. Institutional attention to landscapes and industrial heritage on social media platforms is limited to the activity developed by entities specialized in the field, such as museums or interpretation centers.

4. Discussion

This quantitative study is limited by no-cost search tools: Facebook does not provide total data and Twitter is also limited. In addition, a manual count of the registers is not very operational; without a detailed register, partial data are not very representative. Therefore, manual counting is not a practical solution for obtaining data with these tools. Limitations due to the privacy constraints of numerous publications must be considered, yet the differential value can be discerned in cases such as Instagram. Apart from the difficulties in counting, the diversity of content in some cases does not correspond to the search field. For example, in “ENDESA”, the sample relating to landscape that remains with respect to the rest of the message (corporate advertising, news, reviews, etc.) is negligible.

In sampling #1, the hashtags that received more interest are industrial heritage > industrial landscape > post-industrial heritage > post-industrial landscape. This could be interpreted as a greater acceptance of historical heritage values linked to industrial memory, over the recognition or understanding of the concept of post-industrial landscape.

In terms of content, several profiles could be distinguished whose content was aligned to sensitive approaches and distinctive elements of industrial landscapes. In personal profiles, especially on Twitter, complaints about the degradation and loss of heritage tend to predominate. Instagram mainly showcases esthetic images linked to travel circuits; however, the publications of heritage entities such as the NGO Hispania Nostra are likely to garner some debate. A particular role is played by personal profiles of experts in the given discipline who act on the different platforms as content disseminators and dynamizers of debates and complaints. This is the case for Diana Sánchez Mustieles (@Patrindustrial), J.J. Llera (@EspIndustrial), Diego Arribas (@McMulligan3), and Javier Revilla (@javirevilla), among others. Groups and associations are very active when it comes to disseminating news and informative campaigns about industrial spaces or elements, especially on Facebook and Twitter. Twitter and Facebook are identified as spaces for public debate and dissemination of citizens’ actions that often do not have fixed digital platforms (websites or blogs). This is the case for the actions around the demolition of the cooling towers of the Compostilla and La Robla thermal power plants, when Twitter and Facebook served as a loudspeaker for civic heritage groups. Radio stations, local media, and political parties’ profiles have also acted as disseminators of these types of content. In this sense, social media platforms serve as documentary sources for tracking dynamics, historical evolution, missing/obsolete functions, protection measures, and proposals for the recovery of industrial heritage.

The scarcity of content related to industrial memory in institutional profiles is striking. This phenomenon can be attributed to the lack of specific training of staff, the limited political weight attributed to these spaces, and the limitations of a reduced workforce. The dissemination of content by public administration is limited to very specific properties or landscapes and does not cover all areas subject to cultural protection or equipped with interpretation centers. There is a notable underrepresentation of industrial heritage and landscapes over other types of historical and artistic heritage. A specific study on the presence of content related to industrial heritage on social media profiles of competent administrations is a possible avenue for future analysis.

In sampling #2, the overall morphological, esthetic–perceptual, and social aspects are widely represented compared with the environmental aspect, which is directly mentioned in limited cases. Results show the state of abandonment, ruin, regional disarticulation of the industrial or post-industrial landscapes plus a growing demand for their patrimonialization. References related to environmental issues are limited. However, there are also socioeconomic issues in the background, and these should be analyzed separately. Problems related to the disappearance of heritage legacy of geographically disadvantaged regions could be related to findings presented by Barrio Rodríguez (2022) [43] regarding the digital campaigns of the NGO Hispania Nostra.

In sampling #3, the study cases show mixed results. There is a quite reduced echo of the industrial work attached to the National Institute of Industry as well as an uneven diffusion of the industrial landscape of the different companies. For example, in ENASA, the images of machinery stand out (64%), with the industrial and urban landscape of its factories being limited. ENSIDESA (Figure 3) shows the largest sample and less dispersion in content unrelated to the study; almost half of the analyzed content is related to the industrial profile (45.6%). Rodalquilar, although with a representative number of publications dedicated to the industrial profile or ruin (5%), returns content related to topics unrelated to the study. The situation with company towns is similar, with more than 25% of the analyzed content alluding to topics outside the scope of this study. This question allows us to raise the possibility that these enclaves have transcended their eminently industrial meaning, turning into enclaves or place names capable of alluding to other issues of life. In the case of ENDESA and Compostilla, it is worth mentioning that the “industrial profile” attributed to the industrial town of “Compostilla” and its former thermal power plant offers a greater number of publications than “Compostilla II”, which has a limited echo on Instagram. However, it is possible that the volume of content associated with the landscape significance of Compostilla II increases while the controversy surrounding its demolition continues. Likewise, the inhabited towns of Llaranes and Ciudad Pegaso are the protagonists of an important volume of content attached to the analyzed topics. In the user-generated content studied in these towns are several references to civic actions of patrimonial recognition. On the contrary, the abandoned company towns of Asdrúbal or El Arteal have very limited diffusion in social media, and their presence would be explained by the esthetic component of their ruins.

Figure 3.

Some Instagram photos tagged with the hashtag ENSIDESA.

Social media platforms, in their most basic design, serve to relay the latest news. Undoubtedly, the great novelty of these digital media platforms is their interactivity and the possibility of producing a dialogue between users that can amplify and enrich the news. These platforms effectively constitute new forms, spaces, and times of social interaction as well as new dimensions of culture. Therefore, the information that flows through social media platforms somehow exceeds the mere means of communication, and is part of a new social configuration—a new way of understanding and interpreting culture [44].

Our results indicate that, at a general level, the information collected on social media platforms by individuals, groups, NGOs, and associations is likely to show the pulse of certain sites. The processes of valorization of obsolete industrial landscapes need a multidisciplinary study to which user-generated content contributes by highlighting only some of the characteristics of such landscapes. According to Akehurst (2009) [45], the credibility of user-generated digital content sources are trustworthy. In this sense, we can state that social media platforms respond to a social demand for the recognition of contemporary industry and the productive landscape as a community cultural heritage. However, it is difficult to quantify their scope and level of dissemination. Moreover, based on the social media platforms analyzed in detail (Twitter and Instagram), there is limited space for text and therefore not enough margin for a complete reflection.

As for civic debates on social media platforms, it is worth recognizing their current value in regard to the fact that they are practical cases of application of heritage considerations on elements that have not often been the subject of academic or press attention. In this sense, we could mention the novelty of the terms raised around the process of decarbonization that has opened up new avenues. The obtained results point to a remarkable echo of concrete heritage actions, such as those surrounding the demolition of Compostilla II or Andorra, with a significant influence. More accurate case studies would allow us to deepen this hypothesis. In addition, further studies could be oriented to the geolocation of specific sites or elements, and their echo on social media platforms. It would also be possible to identify recurrent elements over time.

In terms of its reach, Facebook stands out as the most used social media platform, with people interacting and keeping places of historical memory alive. This is in agreement with the general data, where Facebook is the second most visited website in Spain, only after YouTube [46], and the one with the highest number of users [35,47]. Findings of Liang et al. [26] also highlight Facebook being at the top of the rankings (30%), followed by Twitter (19%), and other websites (12%). This shows that platforms that are text-based are the most popular among the global audience. In our results, Twitter stands out as the most used platform to report cases of abandonment, building demolition, etc. Twitter is a platform that allows transmitting and maintaining the interest of an event, as pointed out by the Social Media and Events Report 2011 [48], since most tweets related to an event occur during its celebration (60%); a second peak arises thereafter due to the publication of material that users share, representing 35% [36]. In addition, the use of hashtags and their combination with others already consolidated on this platform allows fostering the dissemination of the event in social media platforms. Campos-Domínguez [49] highlights Twitter’s social role in political communication.

Instagram, on the other hand, produces a call-to-action effect on photos uploaded from certain locations. Recently, researchers have noticed the so-called “Instagram effect”, which implies that a point-of-interest becomes increasingly more popular when highlighted on social media [50], independent of its capacity to absorb visitors. Our results indicate that these are specialized content; industrial and post-industrial landscapes promote considerably less interest than other unrecognized places, in agreement with findings from Falk and Hagsten [32]. In this sense, Instagram can play a prominent role as one of the social media platforms that use visuals to raise awareness of cultural heritage [28].

Last but not least, when analyzing the role of institutions and other administrations, we found that the use of social media platforms to promote heritage is scarce and limited to the dissemination of information, and therefore not for user interaction. Hidalgo Giralt et al. [51] had already pointed out that the quality of information showcased on websites, and the dissemination of digital content in cultural spaces, only reach average values; the type of information they offer is basic, and user interaction is lacking.

5. Conclusions

The role that social media platforms play in Spain in relation to the conservation of industrial heritage and its revaluation has been studied for the first time. The sampling carried out here was small and very fragmented. Given the enormous volume of data from various platforms, we found that manual registration was difficult. Further screening is required due to the fact that the keywords used have meanings that go beyond the field of study. The use of hashtag tracking and metric analysis of social media platforms is required for a more precise quantitative study. The use of systems for automating tracking processes, such as Python scripts, could be considered for further analyses.

The findings of this study show that social media platforms can be used as tools to disseminate information about industrial landscapes. Although they are considered communication tools, their contribution is only partial in relation to the reality of post-industrial landscapes. However, it is worth recognizing the added value that their possibility of interaction brings as a reference for current civic debates. To this extent, concepts that can be incorporated into a theoretical discussion on the future of post-industrial landscapes can be identified in social media debates. In this way, social media could play a proactive role in the cultural reactivation of these landscapes. In addition, specific tracking analyses can be oriented toward ethnographic and documentary tasks that could complement inventory and cataloguing work.

Social media platforms have potential as essential tools for training, awareness of collective memory, and social cohesion around industrial and post-industrial landscapes. At the administrative and institutional level, launching social media platforms to encourage industrial heritage as a touristic resource is vital.

The contents of social media platforms could contribute toward mitigating the difficulties related to the recognition, comprehension, and protection of post-industrial landscapes.

Author Contributions

Á.L.R. elaborated the theoretical framework of the study and the methodological proposal. J.M.-M. carried out the data search, both authors developed the study, and J.M.-M. wrote the final manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is part of the research project “The image of the National Institute of Industry in the territory: Cartography and landscape of industry”, funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities. Ref. PGC2018-095261-B-C22. PI: Ángeles Layuno-Rosas.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This research has been supported by Ana Molina and Adrián Magaz. The guidance of Elena Marcos and Mario Peláez about social media tracking is much appreciated. The information about NGO Hispania Nostril’s social media results provided by Beatriz Barrio is also gratefully acknowledged. The authors would also like to thank social media contributors involved in heritage and industrial landscape.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Council of Europe. European Landscape Convention; Council of Europe: Florence, Italy, 2000, October 20th. Signed by Spain in 2000, Ratified in BOE 31, 2008, February 5th. [BOE-A-2008-1899]. Council of Europe Treaty Series-No. 176. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list?module=treaty-detail&treatynum=176 (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- UNESCO, Stockholm Conference. Intergovernmental Conference on Cultural Policies for Development: Final Report; CLT.98/CONF.210/5; UNESCO: Stockholm, Sweden, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.H.; Zhang, H. Progress and Prospects in Industrial Heritage Reconstruction and Reuse Research during the Past Five Years: Review and Outlook. Land 2022, 11, 2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, H.; Cestaro, G. Hostinng the Olympics through industrial regeneration and reuse: A comparative study of Turin 2006, London 2012 and Beijing 2022. In Stati Generali del Patrimonio Industriale 2022; Currà, E., Docci, M., Mennicchelli, C., Russo, M., Severi, L., Eds.; Marsilio Editori: Venezia, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, M.; Chen, C. Renovation of industrial heritage sites and sustainable urban regeneration in post-industrial Shanghai. J. Urban Aff. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cenci, J.; Becue, V.; Koutra, S.; Liao, C. Stewardship of Industrial Heritage Protection in Typical Western European and Chinese Regions: Values and Dilemmas. Land 2022, 11, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biel Ibáñez, P. Unidad de producción térmica Teruel (Andorra). El final de un modelo energético y el inicio de un proceso de patrimonialización. Rolde Rev. Cult. Aragon. 2020, 172–173, 4–25. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, J. 20th-Century Coal- and Oil-Fired Electric Power Generation. Introductions to Heritage Assets (Historic England Guidance). 2015. Available online: https://historicengland.org.uk/images-books/publications/iha-20thcentury-coal-oil-fired-electric-power-generation/ (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Escudero, D.; de la O Cabrera, M.R. Energía y territorio: Inmersiones en un paisaje dinámico. Ábaco Rev. Cult. Cienc. Soc. 2015, 86, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- AAVV. Industrial Heritage Re-Tooled; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Orange, H. Industrial Archaeology: Its Place Within the Academic Discipline, the Public Realm and the Heritage Industry. Ind. Archaeol. Rev. 2013, 30, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangstad, T.R. Defamiliarization, Conflict and Authenticity: Industrial Heritage and the Problem of Representation; NTNU: Trondheim, Norway, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Strangleman, T. “Smokestack Nostalgia,” “Ruin Porn” or Working-Class Obituary: The Role and Meaning of Deindustrial Representation1. Int. Labor Work. Hist. 2013, 84, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoido Naranjo, F. El paisaje, patrimonio público y recurso para la mejora de la democracia. PH, Boletín Inst. Andaluz Patrim. Histórico 2004, 50, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J. A Sense of Place, a Sense of Time; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lowentahl, D. Living with and looking at landscape. Landsc. Res. 2007, 32, 637–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage (TICCIH). Chart of Nizhny Tagil. In Proceedings of the TICCIH Congress 2003, Moscow, Russia, 17 July 2003.

- ICOMOS—TICCIH. «The Dublin Principles». In Proceedings of the Principles for the Conservation of Industrial Heritage Sites, Structures, Areas and Landscapes, 17th ICOMOS General Assembly, Paris, France, 28 November 2011.

- Arnaboldi, M.; Diaz Lema, M.L. Shaping cultural participation through social media. Financ. Account. Manag. 2022, 38, 299–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihelj, S.; Leguina, A.; Downey, J. Culture is digital: Cultural participation, diversity and the digital divide. New Media Soc. 2019, 21, 1465–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, L.; Stark, J.F.; Cooke, P. Experiencing the Digital World: The Cultural Value of Digital Engagement with Heritage. Herit. Soc. 2016, 9, 76–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretaría del Patrimonio Cultura (Chile). ‘Participación Digital en Patrimonio’; Santiago de Chile: Ministry of Cultures, Arts and Heritage of the Government of Chile, October 2022. Available online: https://www.cultura.gob.cl/publicaciones/participacion-digital-en-patrimonio/ (accessed on 7 December 2022).

- Council of Europe. Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society; Council of Europe: Faro, Portugal, 2005, October 27th. Signed by Spain in 2018, Ratified in BOE 144, 2022, June 17th [BOE-A-2022-10041]; Council of Europe Treaty Series-No. 199. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/1680083746 (accessed on 7 December 2022).

- González Sánchez, C. Comunicación y redes sociales en instituciones culturales. Introducción al debate. Rev. PH 2020, 29, 118–119. [Google Scholar]

- Durán Salado, I.; Fernández Cacho, S. Una aproximación al paisaje cultural mediante etnografía virtual complementa el conocimiento experto de la percepción social. Rev. PH 2020, 99, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Lu, Y.; Martin, J. A Review of the Role of Social Media for the Cultural Heritage Sustainability. Sustainbility 2021, 13, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos, F.; Martin, J.; De Luca, C.; Tondelli, S.; Gómez-García-Bermejo, J.; Casanova, E.Z. Computational methods and rural cultural & natural heritage: A review. J. Cult. Herit. 2021, 49, 250–259. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, M.; Sunarya, Y. The Use of Social Media For Raising Awareness of Cultural Heritage And Promoting Industrial Heritage In Indonesia. In Proceedings of the IICACS: IV International and Interdisciplinary Conference on Arts Creation and Studies, Gdansk, Poland, 17 October 2020; Pascasarjana Institut Seni Indonesia: Surakarta, Indonesia, 2020; Volume 2, pp. 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Stuedahl, D.; Lowe, S. Experimentinng with culture, technology, communication: Scaffolding imagery and engagement with industrial heritage in the city. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference in Culture, Technology, Communication: Celebration, Transformation, New Directions, Oslo, Norway, 18–20 June 2014; pp. 98–115. [Google Scholar]

- Vukmirović, M.; Nikolić, M. Industrial heritage preservation and the urban revitalisation process in Belgrade. J. Urban Aff. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naramski, M.; Herman, K.; Szromek, A.R. The Transformation Process of a Former Industrial Plant into an Industrial Heritage Tourist Site as Open Innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, M.T.; Hagsten, E. Visitor flows to World Heritage Sites in the era of Instagram. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1547–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobrino Simal, J.; Sanz Carlos, M. Carta de Sevilla de Patrimonio Industrial 2018. Los Retos del Siglo XXI; Sevilla: Centro de Estudios Andaluces. 2019. Available online: https://www.centrodeestudiosandaluces.es/publicaciones/carta-de-sevilla-de-patrimonio-industrial-2018-los-retos-del-siglo-xxi (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Loures, L. Post-industrial Landscapes as Renaissance Locus:The Case Study Research Method. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2008, 117, 293–302. [Google Scholar]

- We are Social & Hootsuite, ‘Digital 2020, Report from Spain’. 2020. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-spain (accessed on 7 December 2022).

- Campillo Alhama, C.; Ramos Soler, I.; Castelló Martínez, A. La gestión estratégica de la marca en los eventos empresariales 2.0. Adres. ESIC Int. J. Commun. Res. 2014, 10, 52–73. [Google Scholar]

- Mariani, M.M.; Di Felice, M.; Mura, M. Facebook as a destination marketing tool: Evidence from Italian regional Destination Management Organizations. Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 321–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Sánchez, M.; Tejedor-Cabrera, A.; Linares-Gómez del Pulgar, M. Indicadores de paisaje: Evolución y pautas para su incorporación en la gestión del territorio. Ciudad Territ. Estud. Territ. 2020, 52, 719–738. [Google Scholar]

- Magaz Molina, J.; Layuno Rosas, Á. Colonization and urbanization of the energy´s territory: National Institute of Industry company towns (1941–1975). In Stati Generali del Patrimonio Industriale 2022; Currà, E., Docci, M., Meninchelli, C., Russo, M., Severi, L., Eds.; Marsilio Editori: Venezia, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- García García, R. Energías extinguidas, Centrales térmicas del periodo de la Autarquía. In Proceedings of the III Seminario del Aula de Formación, Gestión e Intervención sobre Patrimonio de la Arquitectura y la Industria, Madrid, School of Architecture of the Polytechnic University of Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 18–19 February 2016; pp. 163–185. Available online: http://gipai.aq.upm.es/index.php/publicaciones/actas-del-iii-seminario-gi_pai-energia/ (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- García García, R.; Layuno Rosas, Á.; Llull Peñalba, J.; García Carbonero, M. El INI activador de la movilidad nacional: Redes de transporte, empresas e instalaciones de la primera épocca del Instituto (1941–1963). In Hacia Una Nueva Época para el Patrimonio Industrial; Álvarez Areces, M.Á., Ed.; INCUNA: Gijón, Spain, 2021; pp. 363–376. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez Menéndez, G. Aportaciones a la Arquitectura del Movimiento Moderno desde el Patrimonio Industrial: La actividad de Cárdenas y Goicoechea en ENSIDESA. Liño 2011, 17. Available online: https://reunido.uniovi.es/index.php/RAHA/article/view/129 (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Barrio Rodríguez, B. El poder de las redes sociales para dar voz al patrimonio en peligro. In Proceedings of the II Simposio de Patrimonio Cultural ICOMOS España, Cartagena, Spain, 17–19 November 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Vizer, E.; Carvalho, H. Las Tecnologías de la Información y la Comunicación como paradigmas de la Economía de la Información. Rev. Soc. 2007, 39, 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Akehurst, G. User generated content: The use of blogs for tourism organisations and tourism consumers. Serv. Bus. 2009, 3, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asociación Para la Investigación de Medios de Comunicación—AIMC, ‘Marco general de los Medios en España’, Madrid. 2021. Available online: https://www.aimc.es/a1mc-c0nt3nt/uploads/2021/02/marco2021.pdf (accessed on 7 December 2022).

- We are Social & Hootsuite, ‘Digital 2022, Global Oveview Review. The Essential Guide to the World’s Connected Behaviours.’. 2022. Available online: https://wearesocial.com/cn/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2022/01/DataReportal-GDR002-20220126-Digital-2022-Global-Overview-Report-Essentials-v02.pdf (accessed on 7 December 2022).

- Von Ferenczy, D.; Spiess, S.; Koch, L. Social Media and Events Report; AMIANDO: Munich, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Domínguez, E. Twitter y la comunicación política. Prof. La Inf. 2017, 26, 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C. How Instagram Is Changing Travel. National Geographic, 26 Januray 2017. Available online: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/how-instagram-is-changing-travel (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Hidalgo Giralt, C.; Palacios García, A.J.; Fernández Chamorro, V. La operatividad turística de los espacios culturales de origen industrial en Madrid. Un análisis de la oferta turística potencial mediante indicadores. Cuad. Tur. 2018, 41, 1989–4635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).